Association of High Levels of Bullying and Cyberbullying with Test Anxiety in Boys and Girls Aged 10 to 16 Years

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design and Participants

2.2. Measures

2.3. Procedure

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

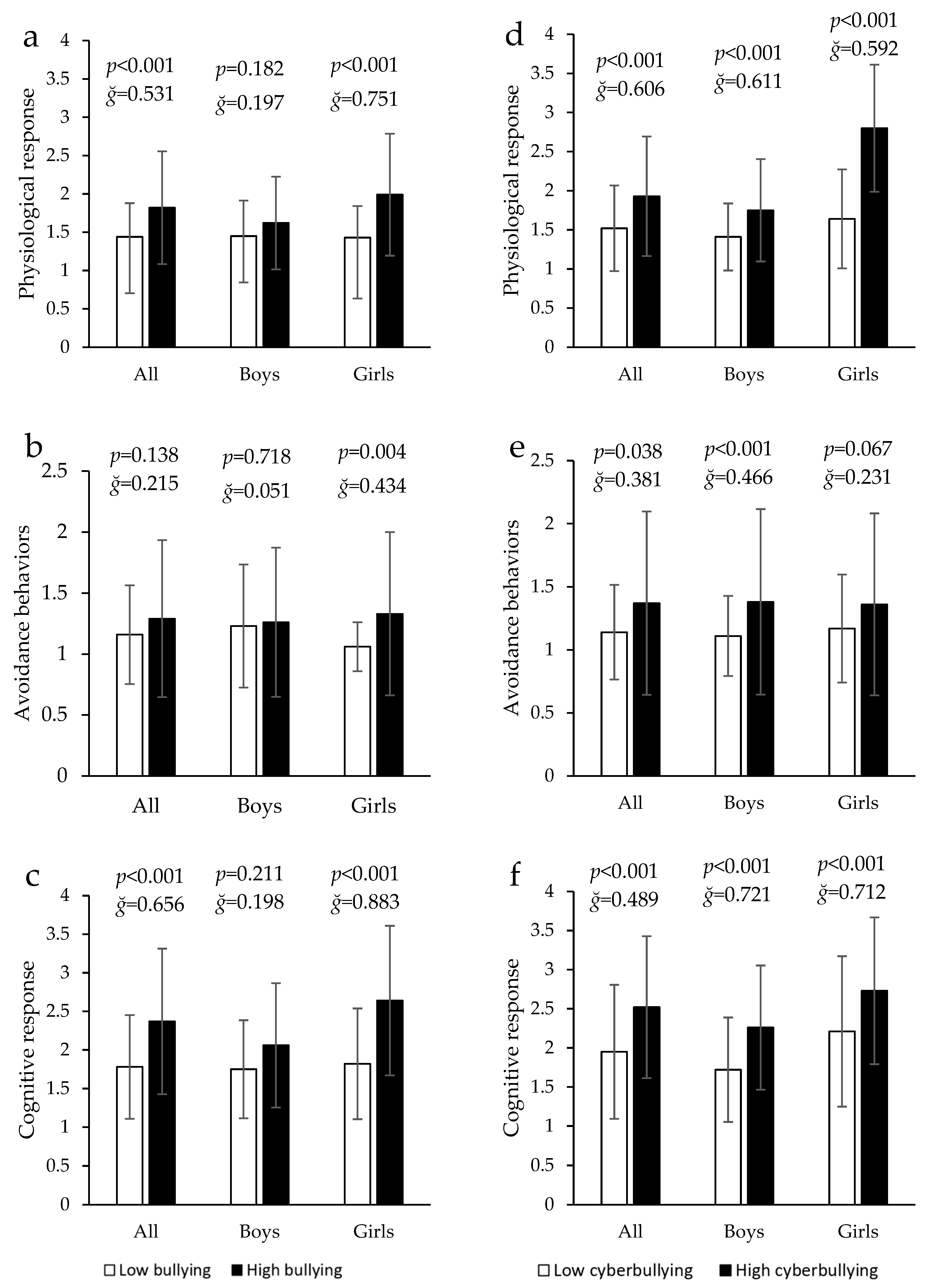

3.1. Analysis of Covariance of Bullying and Cyberbullying Victimization with Respect to Test Anxiety (Physiological Response, Avoidance Behaviors, and Cognitive Response)

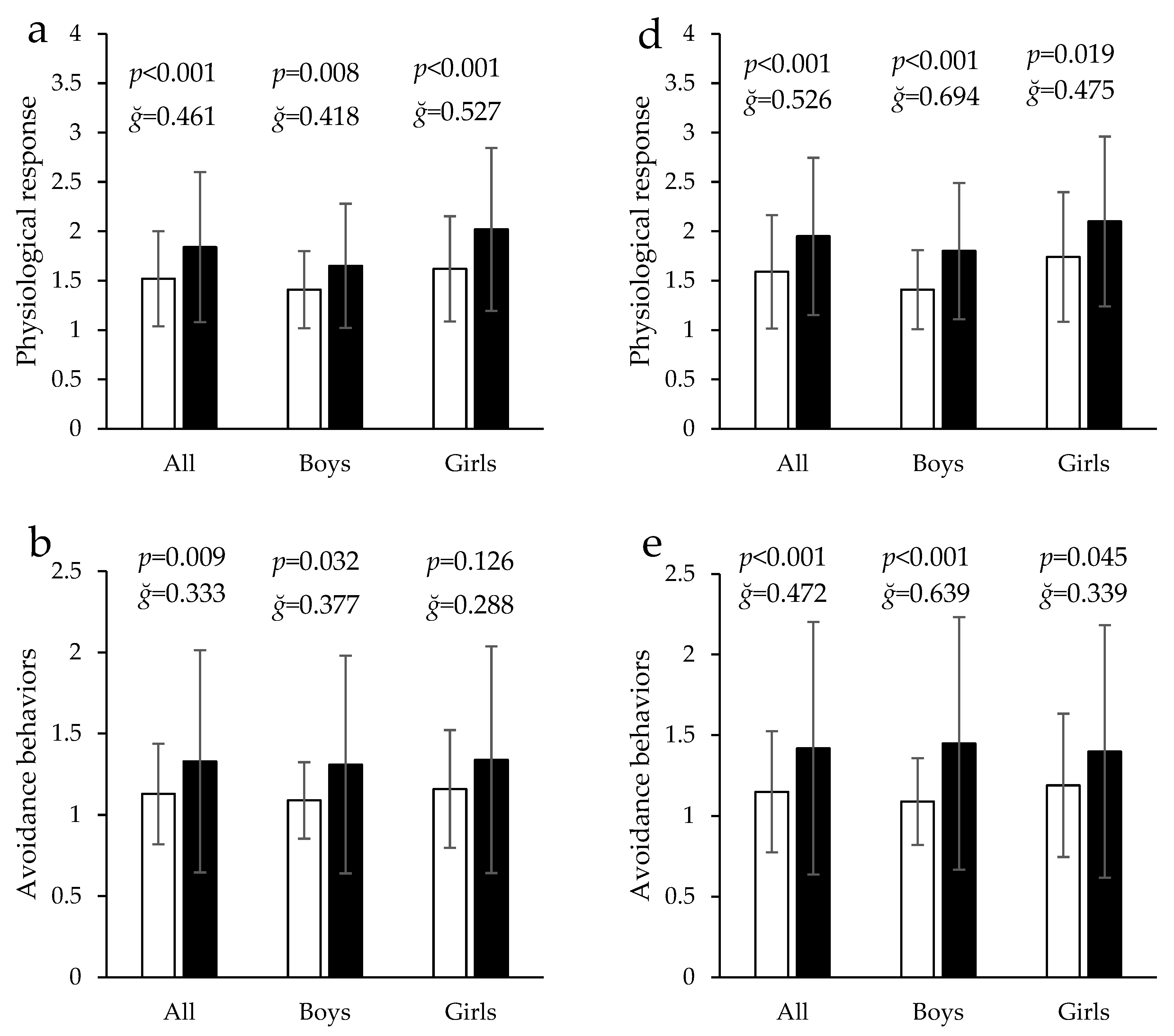

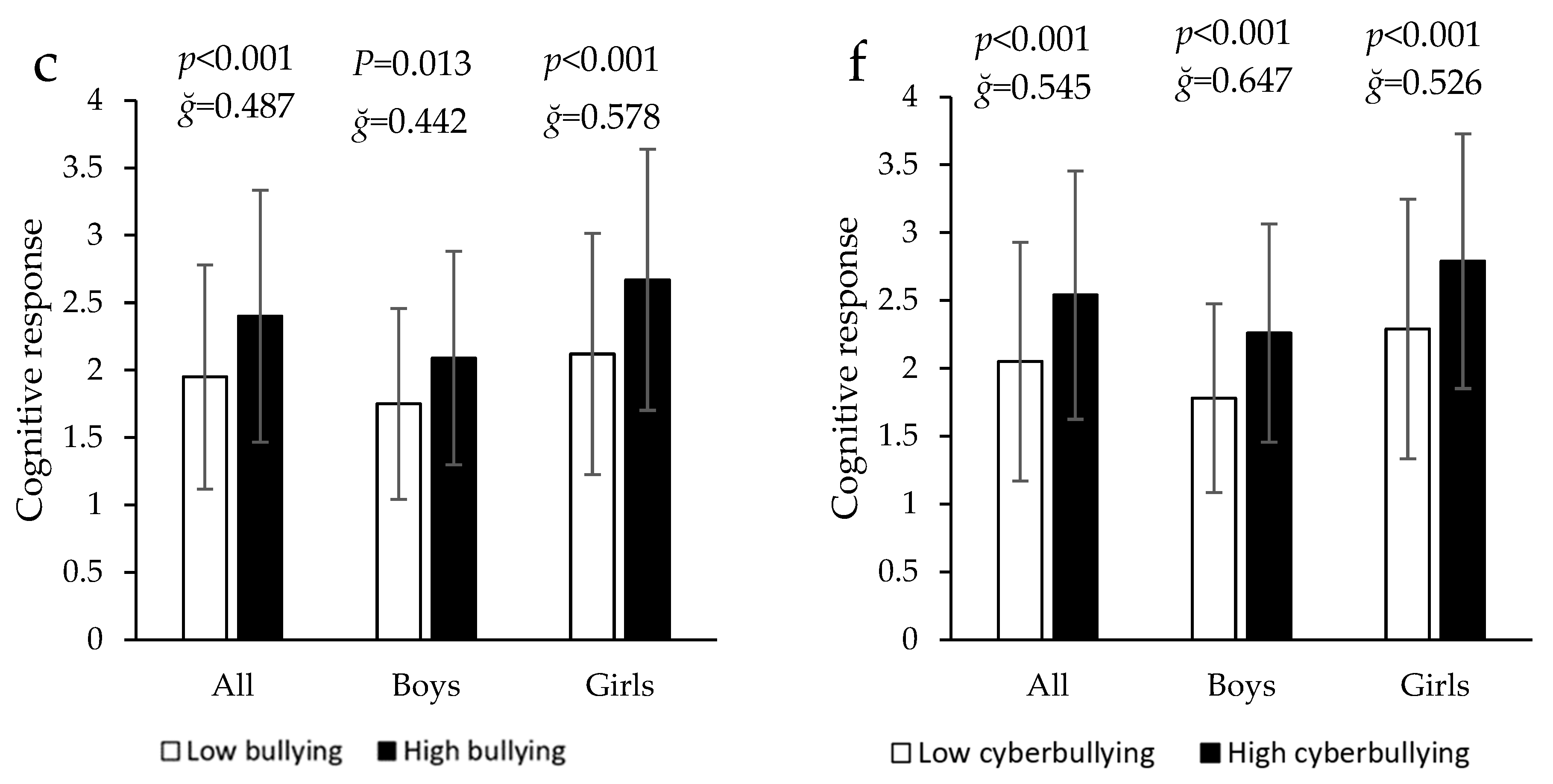

3.2. Analysis of Covariance of Aggression in Bullying and Cyberbullying with Respect to Test Anxiety (Physiological Response, Avoidance Behaviors and Cognitive Response)

3.3. Binary Logistic Regression

4. Discussion

4.1. Bullying and Cyberbullying Victimization and Test Anxiety

4.2. Bullying and Cyberbullying Perpetration and Test Anxiety

4.3. Limitations and Strengths

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Armitaje, R. Bullying in children: Impact on child health. BMJ Paediatr. Open 2021, 5, e000939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO). New Data Reveal That One Out of Three Teens Is Bullied Worldwide; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2019; Available online: https://www.unesco.org/en/articles/new-data-reveal-one-out-three-teens-bullied-worldwide (accessed on 25 April 2024).

- Wang, X.; Shi, L.; Ding, Y.; Liu, B.; Chen, H.; Zhou, W.; Yu, R.; Zhang, P.; Huang, X.; Yang, Y.; et al. School bullying, bystander behavior, and mental health among adolescents: The mediating roles of self-efficacy and coping styles. Healthcare 2024, 12, 1738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cretu, D.M.; Morandau, F. Bullying and cyberbullying: A bibliometric analysis of three decades of research in education. Educ. Rev. 2022, 1, 371–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marín Suelves, D.; Rodríguez Guimeráns, A.; Romero Rodrigo, M.M.; López Gómez, S. Cyberbullying: Education Research. Educ. Sci. 2023, 13, 763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Huang, S.; Lam, L.; Evans, R.; Zhu, C. Cyberbullying definitions and measurements in children and adolescents: Summarizing 20 years of global efforts. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 1000504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Domínguez, J.P.; Raymundo, L.M.; Terrero, J.Y.T. Características de ciberbullying en adolescentes escolarizados. Dilemas Contemp. Educ. Política Valores. 2022, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lareki, A.; Altuna, J.; Martínez-de-Morentin, J.I. Fake digital identity and cyberbullying. Media Cult. Soc. 2023, 45, 338–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maftei, A.; Holman, A.C.; Merlici, I.A. Using fake news as means of cyber-bullying: The link with compulsive internet use and online moral disengagement. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2022, 127, 107032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-González, E.N.; Peña-Ramos, M.O.; Vera-Noriega, J.Á. Validación de una escala de roles de víctimas y agresores asociados al acoso escolar. Electron. J. Res. Educ. Psychol. 2017, 15, 224–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Gómez-Nashiki, A. Cyberbullying. argumentos, acciones y decisiones de acosadores y víctimas en escuelas secundarias y preparatorias de Colima, México. Rev. Colomb. De Educ. 2021, 1, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, J.R.; Mayes, T.L.; Fuller, A.; Hughes, J.L.; Minhajuddin, A.; Trivedi, M.H. Experiencing bullying’s impact on adolescent depression and anxiety: Mediating role of adolescent resilience. J. Affect. Disord. 2022, 310, 477–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arslan, G.; Allen, K.A. School victimization, school belongingness, psychological well-being, and emotional problems in adolescents. Child Indic. Res. 2021, 14, 1501–1517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irwin, A.; Li, J.; Craig, W.; Hollenstein, T. The role of shame in the relation between peer victimization and mental health outcomes. J. Interpers. Violence 2016, 34, 156–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machimbarrena, J.M.; Álvarez-Bardón, A.; León-Mejía, A.; Gutiérrez-Ortega, M.; Casadiego-Cabrales, A.; González-Cabrera, J. Loneliness and personality profiles involved in bullying victimization and aggresive behavior. Sch. Ment. Health 2019, 11, 807–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geoffroy, M.C.; Boivin, M.; Arseneault, L.; Turecki, G.; Vitaro, F.; Brendgen, M.; Côté, S.M. Associations between peer victimization and suicidal ideation and suicide attempt during adolescence: Results from a prospective population-based birth cohort. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2016, 55, 99–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, M.; Huang, X.; Huebner, E.S.; Tian, L. Assocaition between bullying victimization and depressive symptoms in children: The mediating role of self-esteem. J. Affect. Disord. 2021, 294, 322–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kowalski, R.M.; Giumetti, G.W.; Schroeder, A.N.; Lattanner, M.R. Bullying in the digital age: A critical review and meta-analysis of cyberbullying research among youth. Psychol. Bull. 2014, 140, 1073–1137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cosma, A.; Bjereld, Y.; Elgar, F.J.; Clive-Richardson, D.P.; Bilz, L.; Craig, W.; Augustine, L.; Molcho, M.; Malinowska-Cieslik, M.; Walsh, S.D. Gender differences in bullying reflect societal gender inequality: A multilevel study with adolescents in 46 countries. J. Adolesc. Health 2022, 71, 601–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlesier, J.; Vierbuchen, M.C.; Matzner, M. Bullied, anxious and skipping school? The interplay of school bullying, school anxiety and school absenteeism considering gender and grade level. Front. Educ. 2023, 8, 951216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Gao, Y.; Chen, B. Gender differences in cyberbullying tolerance, traditional bullying victimization and their associations with cyberbullying perpetration among Beijing adolescents. Child Fam. Soc. Work 2023, 1, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slonje, R.; Smith, P.K. Cyberbullying: Another main type of bullying? Scand. J. Psychol. 2008, 49, 147–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Markkanen, I.; Välimaa, R.; Kannas, L. Forms of bullying and associations between school perceptions and being bullied among Finnish secondary school students aged 13 and 15. Int. J. Bullying Prev. 2021, 3, 24–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart-Tufescu, A.; Salmon, S.; Taillieu, T.; Fortier, J.; Afifi, T.O. Victimization experiences and mental health outcomes among grades 7 to 12 students in Manitoba Canada. Int. J. Bullying Prev. 2021, 3, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wieczerkowski, W.; Nickel, H.; Janowski, A.; Fittkau, B.; Rauer, W.; Petermann, F. Angstfragebogen für Schüler (AFS), 7th ed.; Hogrefe: Göttingen, Germany, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Aydin, U. Test anxiety: Do gender and school-level matter? Eur. J. Educ. Res. 2017, 6, 187–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzone, L.; Ducci, F.; Scoto, M.C.; Passaniti, E.; D’Arrigo, V.G.; Vitiello, B. he role of anxiety symptoms in school performance in a community sample of children and adolescents. BMC Public Health 2007, 7, 347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liebert, R.M.; Morris, L.W. Cognitive and emotional components of test anxiety: A distinction and some initial data. Psychol. Rep. 1967, 20, 975–978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bian, W.; Zhang, X.; Dong, Y. Autonomic nervous system response patterns of test-anxious individuals to evaluative stress. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 824406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pittig, A.; Boschet, J.M.; Glück, V.M.; Schneider, K. Elevated costly avoidance in anxiety disorders: Patients show little downregulation of acquired avoidance in face of competing rewards for approach. Depress. Anxiety 2021, 38, 361–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castañeda, A.E.; Tuulio-Henriksson, A.; Marttunen, M.; Suvisaari, J.; Lönnqvist, J. A review on cognitive impairments in depressive and anxiety disorders with a focus on young adults. J. Affect. Disord. 2008, 106, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tobias, M.R.; Ito, T.A. Anxiety increases sensitivity to errors and negative feedback over time. Biol. Psychol. 2021, 162, 108092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putwain, D.W.; Von der Embse, N.P. Cognitive–behavioral intervention for test anxiety in adolescent students: Do benefits extend to school-related wellbeing and clinical anxiety. Anxiety Stress Coping 2021, 34, 22–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gustavson, D.E.; du Pont, A.; Whisman, M.A.; Miyake, A. Evidence for transdiagnostic repetitive negative thinking and its association with rumination, worry, and depression and anxiety symptoms: A commonality analysis. Collabra Psychol. 2018, 4, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owens, M.; Stevenson, J.; Hadwin, J.A.; Norgate, R. When does anxiety help or hinder cognitive test performance? The role of working memory capacity. Br. J. Psychol. 2014, 105, 92–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon, D.; Heimberg, R.G.; Tellez, M.; Ismail, A.I. A critical review of approaches to the treatment of dental anxiety in adults. J. Anxiety Disord. 2013, 27, 365–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudaz, M.; Ledermann, T.; Margraf, J.; Becker, E.S.; Craske, M.G. The moderating role of avoidance behavior on anxiety over time: Is there a difference between social anxiety disorder and specific phobia? PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0180298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torrano, R.; Ortigosa, J.M.; Riquelme, A.; Méndez, F.J.; López-Pina, J.A. Test anxiety in adolescent students: Different responses according to the components of anxiety as a function of sociodemographic and academic variables. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 612270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cunha, M.; Paiva, M.J. Text anxiety in adolescents: The role of self-criticism and acceptance and mindfulness skills. Span. J. Psychol. 2012, 15, 533–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schodt, K.B.; Quiroz, S.I.; Wheeler, B.; Hall, D.L.; Silva, Y.N. Cyberbullying and mental health in adults: The moderating role of social media use and gender. Front. Psychiatry 2021, 12, 674298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyroos, M.; Korhonen, J.; Peng, A.; Linnanmäki, K.; Svens-Liavag, C.; Bagger, A.; Sjöberg, G. Cultural and gender differences in experiences and expression of test anxiety among Chinese, Finnish, and Swedish grade 3 pupils. Int. J. Sch. Educ. Psychol. 2015, 3, 37–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Zaatari, W.; Maalouf, I. How the Bronfenbrenner bio-ecological system theory explains the development of students’ sense of belonging to school? SAGE Open 2022, 12, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evensen, M. Adolescent mental health problems, behaviour penalties, and distributional variation in educational achievement. Eur. Sociol. Rev. 2019, 35, 474–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camacho-Morles, J.; Slemp, G.R.; Pekrun, R.; Loderer, K.; Hou, H.; Oades, L.G. Activity achievement emotions and academic performance: A meta-analysis. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 2021, 33, 1051–1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, G.; Zheng, J.; Ratner, K.; Li, Q.; Estevez, M.; Burrow, A.L. How trait and state positive emotions, negative emotions, and self-regulation relate to adolescents’ perceived daily learning progress. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 2024, 77, 102275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raknes, S.; Pallesen, S.; Himle, J.A.; Bjaastad, J.F.; Wergeland, G.J.; Hoffart, A.; Dyregnov, K.; Haland, A.T.; Mowatt-Hagland, B.S. Quality of live in anxious adolescents. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry Ment. Health 2017, 11, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boulton, M.J.; Macaulay, P.J. Does authentic self-esteem buffer the negative effects of bullying victimization on social anxiety and classroom concentration? Evidence from a short-term longitudinal study with early adolescents. Br. J. Educ. Psychol. 2023, 93, 500–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cañas, E.; Estévez, E.; Martínez-Monteagudo, M.C.; Delgado, B. Emotional adjustment in victims and perpetrators of cyberbullying and traditional bullying. Soc. Psychol. Educ. 2020, 23, 917–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Hermoso, A.; Hormazábal-Aguayo, I.; Oriol-Granado, X.; Fernández-Vergara, O.; del Pozo Cruz, B. Bullying victimization, physical inactivity and sedentary behavior among children and adolescents: A meta-analysis. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2020, 17, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, B.; Jeong, S.; Roh, M. Association between body mass index and health outcomes among adolescents: The mediating role of traditional and cyber bullying victimization. BMC Public Health 2018, 18, 674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weis, M.; Trommsdorff, G.; Muñoz, L.; González, R. Maternal education and children’s school achievement: The roles of values, parenting, and behavior regulation. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2023, 32, 691–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, S. The influence of mothers’ educational level on children’s comprehensive quality. J. Educ. Humanit. Soc. Sci. 2023, 8, 1264–1272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortega-Ruiz, R.; Del Rey, R.; Casas, J.A. Evaluar el bullying y el cyberbullying validación española del EBIP-Q y del ECIP-Q. Psicol. Educ. 2016, 22, 71–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Rey, R.; Casas, J.A.; Ortega-Ruiz, R.; Schultze-Krumbholz, A.; Scheithauer, H.; Smith, P.; Thompson, F.; Barkoukis, V.; Tsorbatzoudis, H.; Brighi, A.; et al. Structural validation and cross-cultural robustness of the European Cyberbullying Intervention Project Questionnaire. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2015, 50, 141–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torrano-Martínez, R.; Ortigosa-Quiles, J.M.; Riquelme-Marín, A.; López-Pina, A.J. Propiedades psicométricas de un cuestionario para la evaluación de la ansiedad ante los exámenes en adolescentes. Behav. Psychol. 2020, 28, 245–263. [Google Scholar]

- Prochaska, J.J.; Sallis, J.F.; Long, B. A physical activity screening measure for use with adolescents in primary care. Arch. Pediatr. Adolesc. Med. 2001, 155, 554–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-López, E.J.; De La Torre-Cruz, M.J.; Suarez-Manzano, S.; Ruiz-Ariza, A. Analysis of the effect size of overweight in muscular strength tests among adolescents. Reference values according to sex, age and BMI. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2017, 32, 1404–1414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobel, S.; Wartha, O.; Amberger, J.; Dreyhaupt, J.; Feather, K.E.; Steinacker, J.M. Is adherence to physical activity and screen media guidelines associated with a reduced risk of sick days among primary school children? J. Pediatr. Perinatol. Child Health 2022, 6, 401–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eyuboglu, M.; Duman, S.; Özgür, H. Bullying involvement, anxiety, and depression in adolescence: A cross-sectional study. J. Adolesc. Health 2021, 69, 100–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Monteagudo, M.C.; Delgado, B.; Díaz-Herrero, Á.; García-Fernández, J.M. Cyberbullying, depressive symptoms, and academic performance in secondary education students: A longitudinal study. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2020, 111, 106402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jerrim, J. Test anxiety: Is it associated with performance in high-stakes examinations? Oxf. Rev. Educ. 2023, 49, 321–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roick, J.; Ringeisen, T. Self-efficacy, test anxiety, and academic success: A longitudinal validation. Int. J. Educ. Res. 2017, 83, 84–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Monteagudo, M.C.; Delgado, B.; García-Fernández, J.M.; Ruíz-Esteban, C. Cyberbullying in the university setting. Relationship with emotional problems and adaptation to the university. Front. Psychol. 2020, 10, 510698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martínez-Monteagudo, M.C.; Delgado, B.; Inglés, C.J.; Escortell, R. Cyberbullying and social anxiety: A latent class analysis among Spanish adolescents. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khong, J.Z.; Tan, Y.R.; Elliott, J.M.; Fung, D.S.S.; Sourander, A.; Ong, S.H. Traditional victims and cybervictims: Prevalence, overlap, and association with mental health among adolescents in Singapore. Sch. Ment. Health 2020, 12, 145–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, M.; Branquinho, C.; de Matos, M.G. Cyberbullying and bullying: Impact on psychological symptoms and well-being. Child Indic. Res. 2021, 14, 435–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedditzi, M.L.; Fadda, R.; Striano Skoler, T.; Lucarelli, L. Mentalizing emotions and social cognition in bullies and victims. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 2410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santoyo, D.; Frías, S. Acoso escolar en México: Actores involucrados y sus características. Rev. Latinoam. 2014, 44, 3–41. [Google Scholar]

- Menken, M.S.; Isaiah, A.; Liang, H.; Rivera, P.R.; Cloak, C.C.; Reeves, G.; Lever, N.A.; Chang, L. Peer victimization (bullying) on mental health, behavioral problems, cognition, and academic performance in preadolescent children in the ABCD Study. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 925727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palamarchuk, I.S.; Vaillancourt, T. Integrative brain dynamics in childhood bullying victimization: Cognitive and emotional convergence associated with stress psychopathology. Front. Integr. Neurosci. 2022, 16, 782154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klug, K.; Tolgou, T.; Schilbach, M.; Rohrmann, S. Intrusions in test anxiety. Curr. Psychol. 2021, 40, 2290–2300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kollárik, M.; Heinzel, C.V.; Miché, M.; Lieb, R.; Wahl, K. Exam-related unwanted intrusive thoughts and related neutralizing behaviors: Analogues to obsessions and compulsions. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0270692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilag, O.K.; Diano Jr, F.; Bravante, D.; Blanco, G.M.; Abendan, C.F.; Gepitulan, P.M. Understanding the perception of bullying: A study of high school students’ discourse on peer aggression. Excell. Int. Multi-Discip. J. Educ. 2023, 1, 106–117. [Google Scholar]

- Álvarez-Hernández, J.; Aguilar-Parra, J.M.; Fernández-Campoy, J.M.; Salguero-García, D.; Pérez-Gallardo, E.R. El estrés ante los exámenes en los estudiantes universitarios. Propuesta de intervención. Int. J. Dev. Educ. Psychol. 2013, 2, 179–187. [Google Scholar]

- Esquivel, F.A.; López, I.L.D.L.G.; Benavides, A.D. Emotional impact of bullying and cyber bullying: Perceptions and effects on students. Rev. Caribeña Cienc. Soc. 2023, 12, 367–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eyuboglu, M.; Eyuboglu, D.; Pala, S.C.; Oktar, D.; Demirtas, Z.; Arslantas, D.; Unsal, A. Traditional school bullying and cyberbullying: Prevalence, the effect on mental health problems and self-harm behavior. Psychiatry Res. 2021, 297, 113730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cembreros-Castaño, D.; Moraleda-Ruano, Á.; Nieto-Márquez, N.L. Parental perceived usefulness on a school-integrated app to prevent bullying and eating disorders. Educ. Sci. 2024, 14, 230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foody, M.; Samara, M. Considering mindfulness techniques in school-based anti-bullying programmes. J. New Approaches Educ. Res. 2018, 7, 3–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coelho, V.A.; Marchante, M.; Romao, A.M. Adolescents’ trajectories of social anxiety and social withdrawal: Are they influenced by traditional bullying and cyberbullying roles? Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 2022, 69, 102053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gohal, G.; Alqassim, A.; Eltyeb, E.; Rayyani, A.; Hakami, B.; Al Faqih, A.; Hakami, A.; Qadri, A.; Mahfouz, M. Prevalence and related risks of cyberbullying and its effects on adolescent. BMC Psychiatry 2023, 23, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paulmony, R.; Vasanthakumari, S.; Singh, B.; Almashaqbeh, H.A.; Kumar, T.; Ramesh, P. The impact of bullying on academic performance of students in the case of parent communication. Int. J. Early Child. Spec. Educ. 2022, 14, 2325–2334. [Google Scholar]

- Schneider, J.; King, R. The effects of mindfulness-based interventions on students’ mindfulness, anxiety, and stress according to a range of self-report scales. Mindfulness 2018, 9, 466–478. [Google Scholar]

- Marshall, S.L.; Parker, P.D.; Ciarrochi, J.; Sahdra, B.; Jackson, C.J.; Heaven, P.C.L. Self-compassion protects against the negative effects of low self-esteem: A longitudinal study in a large adolescent sample. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2019, 143, 36–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, T.; Liao, J.; Deng, Y.; Li, L. Cyberbullying victimization and social anxiety: Mediating effects with moderation. Sustainability 2023, 15, 9978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Zhao, H.; Zou, Y. Cyberbullying and traditional bullying victimization, depressive symptoms, and suicidal ideation among Chinese early adolescents: Cognitive reappraisal and emotion invalidation as moderators. Soc. Sci. Comput. Rev. 2023, 1, 512–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| All (n = 912) | Boys (n = 431) | Girls (n = 481) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | p |

| Age (years) | 13.43 | 1.73 | 13.43 | 1.75 | 13.43 | 1.71 | 0.964 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 20.72 | 4.15 | 21.03 | 3.99 | 20.45 | 4.28 | 0.034 |

| Mother’s school level (%) | 0.030 | ||||||

| No studies | 5.4% | 5.2% | 5.6% | ||||

| Primary studies (EGB) | 13.5% | 13.9% | 13.2% | ||||

| Secondary studies (BUP) | 14.4% | 11.6% | 16.8% | ||||

| Professional training | 13.2% | 12.1% | 14.1% | ||||

| University studies | 32.5% | 30.7% | 34.1% | ||||

| N/C | 21% | 26.5% | 16.2% | ||||

| Mean MVPA | 3.97 | 1.76 | 4.35 | 1.75 | 3.64 | 1.70 | <0.001 |

| Academic performance | 6.86 | 1.61 | 6.76 | 1.59 | 6.94 | 1.52 | 0.123 |

| Bullying victimization | 1.80 | 0.78 | 1.77 | 0.78 | 1.83 | 0.79 | 0.211 |

| Bullying aggression | 1.52 | 0.64 | 1.55 | 0.65 | 1.49 | 0.63 | 0.148 |

| Cyberbullying victimization | 1.26 | 0.47 | 1.26 | 0.47 | 1.27 | 0.48 | 0.628 |

| Cyberbullying aggression | 1.21 | 0.47 | 1.22 | 0.46 | 1.21 | 0.47 | 0.672 |

| Physiological response to anxiety | 1.71 | 0.69 | 1.57 | 0.56 | 1.86 | 0.76 | <0.001 |

| Avoidance behaviors | 1.24 | 0.57 | 1.23 | 0.57 | 1.25 | 0.58 | 0.688 |

| Cognitive response to anxiety | 2.24 | 0.92 | 1.96 | 0.77 | 2.48 | 0.97 | <0.001 |

| All (912) | Boys (431) | Girls (481) | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | p | OR | 95%CI | N | p | OR | 95%CI | N | p | OR | 95%CI | ||

| Bullying victimization | |||||||||||||

| Physiological response | Low | 438 | 1 | Referent | 244 | 1 | Referent | 194 | 1 | Referent | |||

| High | 452 | <0.001 | 2.058 | 1.636–2.588 | 174 | 0.013 | 2.055 | 1.485–2.844 | 278 | <0.001 | 2.225 | 1.579–0.133 | |

| Avoidance behaviors | Low | 696 | 1 | Referent | 333 | 1 | Referent | 363 | Referent | ||||

| High | 216 | 0.063 | 1.131 | 0.866–1.543 | 98 | 0.331 | 1.134 | 0.822–1.633 | 118 | 0.023 | 1.683 | 0.217–2.326 | |

| Cognitive response | Low | 450 | 1 | Referent | 269 | 1 | Referent | 181 | Referent | ||||

| High | 447 | <0.001 | 2.884 | 2.234–3.724 | 155 | 0.039 | 1.522 | 1.165–1.968 | 292 | <0.001 | 4.039 | 2.633–0.197 | |

| Bullying aggression | |||||||||||||

| Physiological response | Low | 438 | 1 | Referent | 244 | 1 | Referent | 194 | Referent | ||||

| High | 452 | <0.001 | 1.724 | 1.325–2.243 | 174 | <0.001 | 2.133 | 1.452–3.133 | 278 | 0.023 | 1.892 | 1.241–0.883 | |

| Avoidance behaviors | Low | 696 | 1 | Referent | 333 | 1 | Referent | 363 | Referent | ||||

| High | 216 | <0.001 | 2.341 | 1.780–3.079 | 98 | <0.001 | 2.148 | 1.471–3.136 | 118 | <0.001 | 2.733 | 1.791–4.169 | |

| Cognitive response | Low | 450 | 1 | Referent | 269 | 1 | Referent | 181 | Referent | ||||

| High | 447 | <0.001 | 2.580 | 1.908–3.489 | 155 | <0.001 | 2.865 | 1.885–4.354 | 292 | <0.001 | 4.776 | 2.644–8.624 | |

| Cyberbullying victimization | |||||||||||||

| Physiological response | Low | 438 | 1 | Referent | 244 | 1 | Referent | 194 | Referent | ||||

| High | 452 | <0.001 | 8.311 | 4.610–14.983 | 174 | <0.001 | 15.429 | 6.111–38.957 | 278 | <0.001 | 5.724 | 2.585–12.673 | |

| Avoidance behaviors | Low | 696 | 1 | Referent | 333 | 1 | Referent | 363 | Referent | ||||

| High | 216 | <0.001 | 5.106 | 3.358–7.766 | 98 | <0.001 | 5.341 | 2.829–10.084 | 118 | <0.001 | 4.022 | 3.815–7.959 | |

| Cognitive response | Low | 450 | 1 | Referent | 269 | 1 | Referent | 181 | Referent | ||||

| High | 447 | <0.001 | 21.545 | 9.842–47.164 | 155 | <0.001 | 20.030 | 7.154–56.080 | 292 | <0.001 | 41.452 | 9.628–78.463 | |

| Cyberbullying aggression | |||||||||||||

| Physiological response | Low | 438 | 1 | Referent | 244 | 1 | Referent | 194 | Referent | ||||

| High | 452 | <0.001 | 6.560 | 3.617–11.899 | 174 | <0.001 | 14.296 | 5.757–35.684 | 278 | <0.001 | 5.043 | 2.115–12.026 | |

| Avoidance behaviors | Low | 696 | 1 | Referent | 333 | 1 | Referent | 363 | Referent | ||||

| High | 216 | <0.001 | 6.479 | 3.922–10.702 | 98 | <0.001 | 8.285 | 3.854–17.808 | 118 | <0.001 | 3.707 | 1.380–9.309 | |

| Cognitive response | Low | 450 | 1 | Referent | 269 | 1 | Referent | 181 | Referent | ||||

| High | 447 | <0.001 | 14.431 | 6.455–32.263 | 155 | <0.001 | 26.912 | 8.504–85.162 | 292 | <0.001 | 18.034 | 4.567–71.212 | |

| Number | Action or Treatment Focused on Test Anxiety | Scientific Citation |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Implement school programs that integrate the teaching of relaxation and mindfulness techniques before exams for students affected by bullying and cyberbullying | Foody and Samara [78] |

| 2 | Develop digital education programs for parents and students that include strategies for managing anxiety related to cyberbullying | Coelho, Marchante, and Romao [79] |

| 3 | Offer workshops on stress management and self-help techniques to improve test stress resilience in affected students | Eyuboglu et al. [77] |

| 4 | Create school activities that promote resilience and help students develop coping skills in the face of stressful testing situations | Gohal et al. [80] |

| 5 | Establish reporting and support systems that allow students to communicate their concerns about bullying anonymously and receive counseling to manage anxiety before exams | Martínez-Monteagudo et al. [60] |

| 6 | Launch awareness campaigns that educate students about the effects of bullying and cyberbullying on test anxiety and how to address it | Paulmony et al. [81] |

| 7 | Provide workshops for families on how to support students in managing test anxiety, especially in the context of bullying | Schneider and King [82] |

| 8 | Encourage the use of emotion journals for students to document their experiences and emotions related to exams, allowing for better follow-up and support | Marshall et al. [83] |

| 9 | Implement rapid action protocols in schools to address bullying incidents and reduce victims’ immediate anxiety before exams | Xia et al. [84] |

| 10 | Offer psychological recovery programs that include cognitive behavioral therapy to address both bullying and test anxiety in victims and perpetrators | Zhou et al. [85] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rusillo-Magdaleno, A.; De la Torre-Cruz, M.J.; Ruiz-Ariza, A.; Suárez-Manzano, S. Association of High Levels of Bullying and Cyberbullying with Test Anxiety in Boys and Girls Aged 10 to 16 Years. Educ. Sci. 2024, 14, 999. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14090999

Rusillo-Magdaleno A, De la Torre-Cruz MJ, Ruiz-Ariza A, Suárez-Manzano S. Association of High Levels of Bullying and Cyberbullying with Test Anxiety in Boys and Girls Aged 10 to 16 Years. Education Sciences. 2024; 14(9):999. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14090999

Chicago/Turabian StyleRusillo-Magdaleno, Alba, Manuel J. De la Torre-Cruz, Alberto Ruiz-Ariza, and Sara Suárez-Manzano. 2024. "Association of High Levels of Bullying and Cyberbullying with Test Anxiety in Boys and Girls Aged 10 to 16 Years" Education Sciences 14, no. 9: 999. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14090999

APA StyleRusillo-Magdaleno, A., De la Torre-Cruz, M. J., Ruiz-Ariza, A., & Suárez-Manzano, S. (2024). Association of High Levels of Bullying and Cyberbullying with Test Anxiety in Boys and Girls Aged 10 to 16 Years. Education Sciences, 14(9), 999. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14090999