Abstract

Previous studies have explored the factors influencing entrepreneurial intentions (EIs), primarily focusing on personality traits and various psychological aspects. This study, however, investigates external factors, such as entrepreneurship education programs (EEPs), cognitive motivational factors associated with the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB), and the impact of business incubation centers (BICs), as moderators of EIs. The research involved 458 respondents from diverse higher education institutions in Asia. Our findings indicate that EEPs and BICs at universities positively and significantly affect students’ EIs. Additionally, the cognitive factors linked to TPB demonstrate a positive and significant direct effect on EIs while also acting as mediators between EEPs and EIs. These findings underscore the importance of adopting a multilevel perspective in designing and implementing EEPs and BICs to better comprehend the determinants of EIs. Our study provides valuable insights for university administrators, policymakers, and entrepreneurship instructors in developing countries to improve the university entrepreneurial ecosystem by creating cohesive programs and supportive institutions. Moreover, the results can serve as encouragement for individuals embarking on an entrepreneurial journey.

1. Introduction

Empirical research has described the roles of entrepreneurial activities at the national level and in the development of societies [1]. Specifically, entrepreneurship has the potential to boost employment opportunities and modernize markets, thereby improving economic efficiency [2,3,4,5]. These studies have shown that education can cultivate entrepreneurial behavior, which is essential for shaping individuals’ attitudes, intentions, and competencies [2,3]. They have significantly motivated the implementation of entrepreneurship education programs (EEPs) in academic institutions worldwide, while the funding for these programs continues to grow [6]. Entrepreneurship education (EE) cultivates the development of a mindset focused on entrepreneurship [6] and encourages the start of new ventures, which can lead to the economic progress of a country [7].

The impact of entrepreneurial behavior is not simple because many contextual factors play a role in shaping it. Higher education institutions (HEIs) have recognized how effective business incubation centers (BICs) can be in promoting entrepreneurial spirit [8,9]. These centers create conducive environments for the expansion and early-stage progression of businesses [10]. Moreover, BICs provide students with specific training and information, supporting and guiding them through the entrepreneurial process. By fostering entrepreneurial endeavors, these incubators have the potential to contribute significantly to economic development [11].

Classroom lectures at academic institutions are insufficient for achieving technological commercialization [12] and practical entrepreneurship [12,13,14]. Instead, these institutions require the establishment of strong connections among business, technology, science, and other relevant societal stakeholders [15]. BICs are helpful for young entrepreneurs in initiating their path toward business ventures [11]. Moreover, BICs have the potential to influence the mindset and emotions of students, thereby enhancing their entrepreneurial intentions (EIs) [16]. In addition to providing EEPs, BICs foster an entrepreneurial culture within a country [17,18] by promoting the necessary elements [11] toward engagement with entrepreneurial actions [11,16].

The current study aims to provide an overview of entrepreneurship education programs and entrepreneurial intentions in a developing country like Pakistan. According to United Nations estimates, Pakistan’s population had already surpassed 240 million and was expected to rise further to 245 million by July 2024 [19]. Interestingly, two-thirds of this population consists of young people under 24 years old. The country has approximately 250 public and private colleges, with the majority offering graduate and undergraduate business programs [20].

In Pakistan, the unemployment rate has been at around 8% during 2024 [21]. However, the Pakistan Economic Survey 2023–2024 [22] reveals that youth aged 15–24 face an even higher unemployment rate of 11.1%. This situation is particularly concerning given that a significant portion of the country’s unemployment is concentrated among the educated youth. Paradoxically, the open unemployment rate tends to be higher among the highly educated labor force [22], highlighting a critical gap between education and employability. This underscores the importance of fostering entrepreneurial intentions and providing effective entrepreneurship education to address the employment challenges faced by young and educated populations in developing economies such as Pakistan.

Therefore, this research aims to analyze student entrepreneurial intentions through entrepreneurship education program. Drawing on the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB), we test a conceptual framework that examines the moderating role of BICs and the mediating effects of cognitive elements linked to TPB—such as psychological motivational factors associated with intentions and behavior. These elements include attitudes toward entrepreneurship, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control, all of which shape EIs. These findings offer insights for HEI administrators and entrepreneurial ecosystem strategists in developing countries, providing a basis for policies and initiatives that encourage business ventures.

This paper is organized as follows: First, we develop the hypotheses based on existing research. Then, we outline the data and methodology used in the study. Next, we present the main findings. Following this, we discuss these findings in the context of existing research, providing theoretical and empirical insights. Finally, we conclude and acknowledge the limitations of the study.

2. Literature Review and Hypotheses Development

Our research is based on the TPB, which is an extension of the theory of reasoned action [23] and aims to explain the motivational factors linked to certain behaviors [24]. This theoretical framework posits that intentions are shaped by three conceptually independent cognitive motivational factors related to an individual’s perception of the behavior, including their attitude toward the behavior (i.e., the degree to which the behavior is evaluated favorably or unfavorably), subjective norms (i.e., the perceived social pressures to perform or not perform the behavior), and perceived behavioral control (i.e., the perceived ease or difficulty of performing the behavior) [23]. The theory suggests that higher levels of these cognitive motivational factors are associated with a greater likelihood of performing a behavior [24].

The TPB has been widely applied within the social and behavioral sciences [23] to explore individuals’ intentional behaviors [25], and it has been a core theoretical framework within the entrepreneurship field for understanding entrepreneurial intentions [26,27,28], the impact of gender on entrepreneurial intentions, [29], the entrepreneurial decision to transfer a business unit [30], and predicting nascent entrepreneurship [31]. Utilizing these principles, our study examines the impact of BICs on both EEPs and EIs. We concentrate our analysis on EIs as the core construct, given their ability to accurately predict planned behaviors and their utility in forecasting whether an individual will become an entrepreneur [27]. To this end, we aim to assess the accuracy and reliability of the TPB in the context of HEIs within the Asian region. The following subsections describe the relationships among our core constructs.

2.1. EEPs and EIs

The primary goal of an EEP is to foster the participant’s inclination toward pursuing entrepreneurship as a vocation [12,13,14]. The importance of EEPs has been widely acknowledged due their global usage in recent decades [28,32]. EEPs play a pivotal role in fostering entrepreneurship by facilitating the establishment of new businesses [2,3]. They can induce substantial transformations in cultures, attitudes, and support networks over prolonged durations [33,34]. They also encompass educational courses, programs, and strategies designed to enhance students’ attributes [35], attitudes, and business acumen while aligning with program objectives [35]. Given that the entrepreneurial journey is a long-term process, continuous entrepreneurial learning is essential for overcoming potential obstacles [36,37,38].

Previous empirical and literature reviews within the entrepreneurship pedagogy have discussed how entrepreneurship education affects EIs [25,28,39,40,41]. While these studies have highlighted contrasting empirical results between EEPs and EIs [28,40], they generally suggest that EEPs can enhance students’ predispositions toward viewing entrepreneurship as a viable career choice, thereby increasing their perceived control over engaging in such behavior [41,42]. Specifically, as EEPs are designed to improve students’ understanding and knowledge of the complex steps involved in business ventures [43], students may develop a more positive disposition toward engaging in entrepreneurial activities [44]. In this context, prior empirical research suggests a strong and direct link between individuals who undergo comprehensive EEPs and their future goals of becoming entrepreneurs. Therefore, we hypothesized the following:

Hypothesis 1 (H1).

EEPs are linearly and positively associated with EIs.

2.2. EEPs as Antecedents of TPB

Previous research has explored how EEPs are related to elements of the TPB and their subsequent effects on EIs [12,33]. Initially, the main goal of an EEP is to help students develop the skills and abilities needed to pursue entrepreneurial activities [12,45] and to foster a positive attitude toward seizing business opportunities [46]. Empirical studies have shown that EEPs improve students’ knowledge, boosts their self-confidence, and broadens their perspectives on entrepreneurship [16,47].

EEPs play a critical role in molding the aspirations and mindsets of students [45]. Research indicates that EEPs in science and engineering fields can influence students’ subjective norms (SNs) but not their perceived behavioral control (PBC), significantly enhancing their EIs and perceptions of the feasibility of engaging in entrepreneurial activities [48]. Additionally, EEPs seem beneficial for students in business, science, and technology majors, although they may negatively impact SNs [45]. Furthermore, individual cognitive factors, such as locus of control and risk profile, indirectly affect students’ attitudes toward entrepreneurship (ATEs) [36]. Therefore, we formulated the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 2 (H2).

EEPs are linearly and positively associated with (H2a) SNs, (H2b) PBCs, (H2c), and ATEs.

2.3. Cognitive Factors of a TPB as an Antecedent of EIs

Empirical evidence suggests a direct correlation between TPB and EIs [36]. Particularly, we aimed to test the moderating effects of TPB’s cognitive factors (i.e., SNs, PBC, and ATE). According to this theoretical framework, individuals form their intentions based on their attitudes toward an action, their social circle, and perceived behavioral control [27,49]. These factors—ATE, SNs, and PBC—play significant roles in shaping EIs [44,50,51].

Firstly, individual valuation of a behavior is linked to their prospective actions. For instance, Ref. [45] describes a direct correlation between the inclination to be an entrepreneur and a commitment to business venturing. Secondly, how an individual perceives social norms in their environment—including the beliefs, behaviors, and aspirations of their peers—can significantly influence and potentially constrain their pursuit of particular goals [24]. Specifically, individuals who perceive support from their family and social circles [45] are more likely to exhibit entrepreneurial aspirations [45,52]. Lastly, PBC involves assessing an individual’s perceived skills and capabilities in executing a particular activity [24]. PBC plays a dual role: it influences the formation of intentions and, subsequently, affects the actual behavior. Participation in various events, networking through entrepreneurship clubs and groups, and attending academic workshops and conferences can be advantageous for developing business ideas [53,54]. Based on this rationale, we hypothesized the following:

Hypothesis 3 (H3).

(H3a) ATEs, (H3b) SNs, and (H3c) PBCs are linearly and positively associated with EIs.

2.4. Cognitive Factors of TPB as Mediators

Previous research has explored the indirect effect of EEPs on EIs [41,55,56,57] and the mediating roles of the cognitive elements linked to TPB. For instance, Ajike et al. [55] found a significant difference in EIs between students who received an entrepreneurship education and those who did not, with participants showing a higher likelihood of aspiring to start their own businesses. Aliedan et al. [56] explored the role of university education support and found that entrepreneurship programs positively influence EIs indirectly. Similarly, Asghar et al. [57] conducted interviews and found that EEPs enhanced students’ EIs by boosting self-confidence, generating a positive perception of entrepreneurial activities, and creating a supportive normative environment for entrepreneurship. Lastly, Rauch and Hulsink [41] confirmed through a quasi-experimental approach that EEPs positively impact EIs through cognitive motivational factors linked to the TPB.

We posit that the mechanism behind this relationship is rooted in the nature of EEPs. Specifically, these programs are designed to cultivate an entrepreneurial mindset by enhancing self-confidence, boosting risk tolerance, and improving students’ perceptions of entrepreneurship as a viable career path [58]. Consequently, EEPs indirectly influence EIs through these cognitive elements [41]. This reasoning aligns with Ajzen’s theory [24], which suggests that human behavior is characterized by rationality, planning, and conscious regulation. According to this theory, individuals evaluate the expected outcomes of a behavior before forming an intention [23]. Thus, in the context of EEPs, students are likely to perceive greater benefits from engaging in entrepreneurship, such as increased monetary gains or societal status. Based on this rationale, we hypothesized the following:

Hypothesis 4 (H4).

EEPs exert positive effects on EIs through the following cognitive motivational factors of planned behavior: (H4a) ATEs, (H4b) SNs, and (H4c) PBCs.

2.5. BICs as Moderators

Universities worldwide are grappling with several societal challenges, such as high unemployment rates among graduates, reduced public funding, and declining demand for higher education [59]. These external pressures are reshaping their organizational missions. In response, universities have evolved their core activities—teaching, research, and knowledge transfer/commercialization—to develop entrepreneurial ecosystems that enhance their societal impact. BICs have emerged as a critical component of these entrepreneurial ecosystems. By forging strong connections with industry, technological partners, and other stakeholders, BICs help universities better understand the business environment and increase the likelihood of successful ventures [60]. BICs offer a concrete platform for students and scholars to begin their entrepreneurial journeys and contribute to sustaining and expanding the ventures they support [9]. They provide entrepreneurship education [16] and play a significant role in fostering regional and national entrepreneurship [11,16]. BICs create a supportive and secure environment by ensuring that startup companies have access to essential resources and support [61,62].

While previous research suggests that university-provided BIC services can impact students’ EIs [63], the effectiveness of these programs in enhancing institutions’ capacities to promote EIs among graduates remains uncertain [8,63,64]. Few studies have explored the influence of BICs and EEPs on graduates’ career choices to become entrepreneurs [65,66,67]. The detailed impact of incubators and entrepreneurship education on graduates’ occupational decisions has yet to be thoroughly investigated [12,59,68,69,70]. However, aligning with previous empirical findings [64], we posit that students engaged in entrepreneurial endeavors within HEIs may perceive a higher likelihood of developing EIs. Specifically, students involved in assistance, concept creation, and company development guidance may experience increases in their internal locus of control, motivation, and self-confidence [71]. Additionally, BICs act as intermediaries, providing essential resources such as infrastructure, financial support, and networking opportunities [72]. Thus, BICs are likely to stimulate strong interest among recent graduates in business venturing. Based on this reasoning, we formulate the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 5 (H5).

BICs positively moderate the relationship between EEPs and EIs.

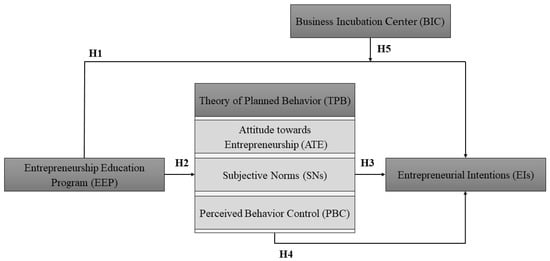

Figure 1 illustrates the conceptual framework, including the direct effects of EEPs (H1) and TPB (H3) on EIs. In addition, it also presents the role of EEPs in shaping TPB (H2). Moreover, it illustrates the mediating role of TPB between EEPs and EIs (H4). Finally, it shows the moderating role of BICs on EIs (H5).

Figure 1.

Conceptual model.

3. Data and Methods

3.1. Data

Our research focuses on HEIs in the Asian region, specifically in Pakistan. We employed a convenient, non-probabilistic sampling technique for data collection to test our conceptual model. This approach was chosen because of its advantages, including affordability, ease of data collection, and the ready availability of respondents [73]. Initially, we conducted a pilot survey with 28 undergraduate students to test and refine our research instrument. Following this, we carried out a larger cross-sectional survey involving 458 undergraduate and postgraduate students majoring in management sciences (i.e., business studies) from ten public and private HEIs in Pakistan. Students were approached through various methods, including social media platforms within institutional groups and electronic questionnaire distribution.

The final sample consisted of ten HEIs which represented conventional universities offering various graduate and undergraduate degree programs in the fields of Business and Management. Those HEIs implemented EEPs in their programs, as well as BICs. Located in Pakistan’s three main cities—Karachi, Lahore, and Islamabad—these universities were chosen for their diverse representation. The diversity of the universities included in the final sample indicates that self-selection bias was not a significant issue, while also suggesting a homogeneous group for testing the model. To obtain the data, the research adhered to international ethical guidelines for human research and received approval from an ethical committee.

3.2. Variables

This study utilized a self-designed, closed-ended questionnaire to assess each latent variable. Each item in the latent variables were rated on a seven-point Likert scale that takes values from one (Strongly Disagree) to seven (Strongly Agree). The Supplementary Material presents a copy of the instrument.

EIs were assessed using a six-item Likert scale, including items such as EI1 (“I am ready to do anything to be an entrepreneur”), EI2 (“My professional goal is to become an entrepreneur”), EI3 (“I will make every effort to start and run my firm”), EI4 (“I am determined to create a firm in the future”), EI5(“I have very seriously thought of starting a firm”), and EI6 (“I have the firm intention to start a firm someday”) [74].

EEPs were assessed using a six-item Likert scale, including items such as EEP1 (“Enhance your practical management skills to start a business”), EEP2 (“Enhance your ability to develop networks”), EEP3 (“Enhance your ability to identify an opportunity”), EEP4 (“Increase your understanding and attitudes toward entrepreneurship”), EEP5 (“Increase your attitudes and values to become an entrepreneur”), and EEP6 (“Increase your actions to take to start a business”) [75].

Moreover, each cognitive factor of TPB, including SNs, ATEs, and PBC, were assessed using scales (Anjum et al., 2022) previously employed in empirical examinations [76,77]. Specifically, SNs comprised the following three items: SN1 (“My parents are supportive of my future career as an entrepreneur”), SN2 (“My university actively encourages students to pursue their own business ideas”), and SN3 (“I believe that important people in my life think I should pursue a career as an entrepreneur”).

Moreover, ATEs comprised the following six items: ATE1 (“Being an entrepreneur would bring me great satisfaction”), ATE2 (“I believe I would be successful if I started my own business”), ATE3 (“I find a career as an entrepreneur attractive”), ATE4 (“I prefer being my own boss over having a secure job”), ATE5 (“I have seriously considered starting my own business”), and ATE6 (“I find a career as an entrepreneur appealing”).

Lastly, PBC comprised the following five items: PBC1 (“Starting a business would be manageable for me”), PBC2 (“I feel capable of running a business effectively”), PBC3 (“I know how to develop an entrepreneurial project”), PBC4 (“If I attempted to start a business, I believe I would have a high chance of success”), and PBC5 (“Starting my own business would likely be the best way for me to utilize my education”).

Finally, the perceived effectiveness of BICs was assessed using a five-item Likert scale. The items included the following: BIC1 (“Business incubators nurture the entrepreneurial skills and capabilities of young entrepreneurs”), BIC2 (“Working in a shared space with similar professionals helps us solve common problems and share networks and resources”), BIC3 (“Business incubators provide a supportive professional environment that enhances the motivation and productivity of young entrepreneurs”), BIC4 (“Mentoring and coaching sessions assist incubatees in quickly getting on the right track to start a new business”), and BIC5 (“Networking services offer opportunities for young entrepreneurs to connect with various stakeholders involved in the entrepreneurship ecosystem”) [78].

3.3. Method

We adopted a deductive approach to test our hypotheses. Specifically, we applied partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) estimation (Farrukh, Lee, Sajid, et al., 2019). This model is a useful method to account simultaneously for the measurement model (inner model) as well as the structural model (outer model) [79]. The analysis was conducted using SmartPLS 4.0 software, consistent with established methodologies in prior entrepreneurship research [36,77,80].

4. Results

4.1. Sample Characteristics

Table 1 presents the sample description considering a set of demographic characteristics. The sample comprised 67.47 percent male respondents and 32.53 percent female respondents. Additionally, 93.23 percent of respondents were under 25 years old. A significant majority of individuals within the selected demographic, specifically 89.30 percent, hold a bachelor’s degree, while a smaller proportion, accounting for 10.70 percent, were enrolled in graduate programs (i.e., master’s degree). Furthermore, an overwhelming majority of students, 89.96 percent, did not have previous experience working in a professional setting. Finally, approximately 54.80 percent of the sample came from families in which at least one member was self-employed.

Table 1.

Sample description.

4.2. Evaluation of the Measurement Model (Inner Model)

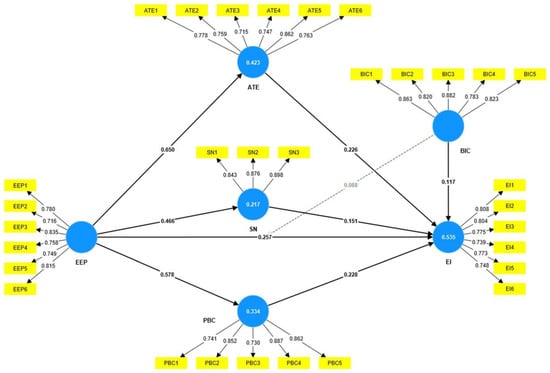

Initially, we scrutinized how the model influences the interpretation of data and the identification of relationships among variables. Figure 2 illustrates the cross-loading of each item and presents the preliminary relationships among constructs. The cross-loadings surpassed conventional thresholds, suggesting an efficient measurement model.

Figure 2.

Structural model (algorithmic analysis).Solid line implies direct effect; while dotted line implies moderation effect.

Next, we assessed the reliability, convergent validity, and discriminant validity of the latent variables. Table 2 displays the cross-loading of each item, along with the Cronbach’s alpha (CRA), composite reliability (CMR), and average variance explained (AVE). Each criterion was evaluated based on conventional thresholds [81]. Specifically, we observed that each latent variable surpassed the CR threshold (0.7) and exceeded the AVE threshold (0.5), signaling reliability, convergent validity, and discriminant validity.

Table 2.

Cross-loadings, reliability, convergent validity, and discriminant validity.

4.3. Discriminant Validity

To validate our findings, we computed the cross-loadings (Column 3 in Table 2) and applied the Fornell and Larcker [82] criterion (FLC). Table 3 illustrates the FLC relationships between latent constructs and the square root of the AVE. Specifically, we observed that the square root of the AVE exceeded the correlation values of the latent constructs [83]. This indicates that the square root surpassed the correlation values of the components, thus confirming the validity of the model [84].

Table 3.

FLC criterion.

Next, we conducted an additional assessment using the Heterotrait–Monotrait (HTMT) ratio (Henseler et al. (2015)). Table 4 presents the HTMT values obtained for each pairwise latent variable. We observed that none of the HTMT values exceeded the conventional threshold of 0.85 [82], thereby confirming the validity of the model.

Table 4.

Heterotrait–Monotrait ratio (HTMT).

4.4. Evaluation of the Structural Model (Outer Model)

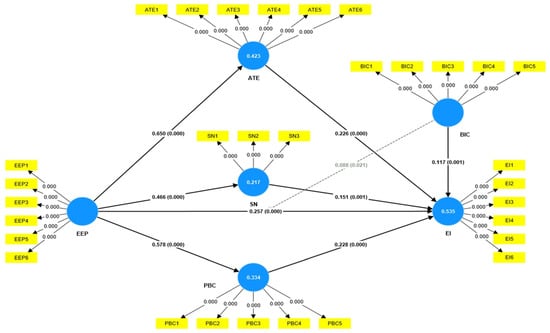

Figure 3 illustrates the path coefficients and their statistical significance (i.e., p-values). Visually, Figure 3 suggests a good fit of the structural model given the statistical significance of the relationships. Table 5 outlines the coefficients obtained using an algorithm that employed bootstrap resampling with 5000 resamples [85]. Initially, we found support for H1 as EEPs exhibit a positive and direct effect on EIs (coefficient = 0.26, p = 0.00). Subsequently, we found support for H2a, as EEPs exhibit a positive effect on ATEs (coefficient = 0.65, p = 0.00). Moreover, we found support for H2b, as SNs exhibit a positive effect on ATEs (coefficient = 0.47, p = 0.00). Additionally, we found support for H2c, as PBC exhibits a positive effect on ATEs (coefficient = 0.58, p = 0.00). Finally, we found support for H3a, as ATEs have a positive and direct effect on EIs (coefficient = 0.23, p = 0.00). We also found support for H3b, as SNs have a positive and direct effect on EIs (coefficient = 0.15, p = 0.00). Lastly, we found support for H3c, as PBC has a positive and direct effect on EIs (coefficient = 0.23, p = 0.00).

Figure 3.

Structural model (outer model).

Table 5.

Hypothesis testing.

4.5. Mediating Effects

Subsequently, we evaluated the mediating effects of ATEs, SNs, and PBC on the relationship between EEPs and EIs. The mediating effects are presented in Table 6. Specifically, we found support for H4a, as ATEs exert positive mediating effects on the relationship between EEPs and EIs (coefficient = 0.15, p = 0.00). Moreover, we found support for H4b, as SNs exert positive mediating effects on the relationship between EEPs and EIs (coefficient = 0.07, p = 0.00). Finally, we found support for H4c, as PBC exerts a positive mediating effect on the relationship between EEPs and EIs (coefficient = 0.13, p = 0.00).

Table 6.

Mediating effect testing.

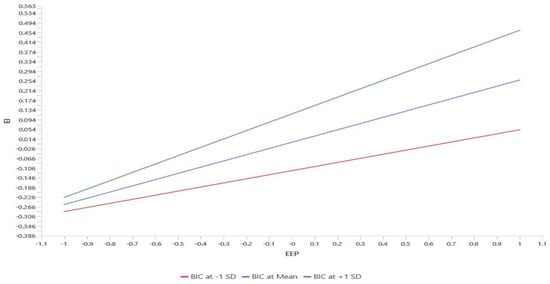

4.6. Moderation Effect

Finally, we assessed the moderating role of BICs on the linear relationship between EEPs and EIs. Table 7 and Figure 4 present the results of the moderation analysis. We found support for H5, as BICs exert a positive and statistically significant moderating effect (coefficient = 0.09, p-value = 0.02). This suggests that, regardless of their demographic characteristics, HEIs students are more likely to engage in EIs when BICs are available as supportive institutions.

Table 7.

Moderation effect testing.

Figure 4.

Moderating effect.

4.7. Coefficients of Determination (R Square)

Table 8 displays the R square (R2) values for each dependent variable. The R square was calculated to evaluate the predictive ability of the external latent variables on the dependent latent variables [85]. We observed that the variances in the dependent latent variables, including EIs (R2 = 0.54), ATEs (R2 = 0.42), PBC (R2 = 0.33), and SNs (R2 = 0.22), were satisfactory. This indicates that the variances in EIs, ATEs, PBC, and SNs are explained by the core independent variable (i.e., EEPs).

Table 8.

Coefficients of determination.

5. Discussion

5.1. Key Findings

We investigated the effect of EEPs on EIs. To do so, we tested a conceptual model examining the moderating role of BICs and the mediating effects of cognitive elements of planned behavior that shape EIs (see Figure 1). The findings support all five hypotheses, including the mediation and moderating effects, highlighting the importance of business education, especially focusing on entrepreneurship-related programs, in fostering intentions for business venturing. These results are in line with previous research that has found a positive effect, such as in Refs. [55,56,57]. Based on our findings, the proposed conceptual framework could be used for further empirical studies to address the contradictory results observed in the entrepreneurship education literature, in line with previous calls for research [28].

Furthermore, our results indicate that students participating in EEPs develop an enhanced entrepreneurial mindset and engage more with the entrepreneurial ecosystem established by their university. This engagement fosters positive attitudes toward entrepreneurship, which can influence their intention levels and potentially their future behavior. This aligns with earlier research in this field [41].

Furthermore, since all of the hypotheses in the study are supported, we can infer that students have a higher likelihood of successfully starting new businesses in such contexts, and it can be asserted that entrepreneurial intentions are influenced by the following three distinct motivational sources: contextual drivers (e.g., the presence of business incubators), cognitive drivers (e.g., factors related to planned behavior), and internal drivers (e.g., those perceived by the individual through education). Our findings are consistent with previous empirical studies that have examined these factors individually [75,86,87,88]. Consequently, our research calls for further studies involving multilevel analyses to explore this phenomenon in greater depth.

Furthermore, our findings highlight the influence of ATEs, PBC, and SNs on EIs. Consistent with existing empirical research, this study provides additional evidence of the positive correlations between ATEs, SNs, PBC, and EIs. Therefore, it can be inferred that the cognitive motivational factors of Planned Behavior Theory are significant antecedents for understanding how EIs are shaped across different contexts, including developing economies like Pakistan. Hence, our research suggests adopting a more contextual approach to theory testing, which may clarify the empirical divergences observed in this field.

Another key finding is the positive moderating effect of BICs on the relationship between EEPs and EIs. Students exposed to an academic-driven entrepreneurial ecosystem supported by BICs may exhibit a higher propensity for entrepreneurship. This suggests that individuals who receive strong university support and encouragement from family, as well as who engage in internship opportunities, workshops, or programs provided by BICs, are more likely to view entrepreneurship positively as a career path. As discussed in Section 2 on theory development, this highlights the importance of cognitive elements in shaping EIs. Future research could further explore these findings to investigate the psychological microfoundations of EIs.

5.2. Theoretical and Practical Implications

Our conceptual model (Figure 1) offers several theoretical implications. Firstly, we tested a model that clarifies the direct impact of EEPs on EIs, the moderating role of BICs in this relationship, and the direct and moderating effects of the cognitive motivational factors of planned behavior on individual intentions. Our empirical research provides further support for the ideas posited by Ajzen [23], particularly regarding the elements related to behavioral intentions. While our findings reinforce this theoretical framework, by elucidating the contextual elements that engage in this relationship, we call for further investigation into additional antecedents, moderators, and mediators that influence EIs.

Additionally, our research underscores the role of EEPs in HEIs as crucial antecedents of EIs. However, given that entrepreneurship education remains a nascent concept in universities worldwide, many institutions are still in the process of developing effective programs aimed at fostering an entrepreneurial mindset. While our study highlights the importance of advancing EEPs, future research could explore the didactic elements and educational methodologies most strongly associated with higher EIs. By delving further into these elements, HEI administrators and program managers can integrate the necessary pedagogical components into curricula to better nurture entrepreneurial ecosystems.

Furthermore, university lecturers often prioritize teaching conventional entrepreneurship theories and generic methods over inspiring students to explore their environment, identify unmet needs or social problems, and generate innovative business concepts to address them. Our empirical results suggest that immersing students in an entrepreneurial environment fosters EIs. Channeling potential entrepreneurial activities toward social goals could lead to positive societal outcomes. To cultivate a more entrepreneurial mindset, instructors should emphasize experiential learning and project-driven methodologies, moving beyond conventional pedagogical practices. Given the inherent uncertainty of entrepreneurship as a risky economic activity, exposing students to realistic entrepreneurial experiences may reduce the likelihood of failure in future ventures. Therefore, investigating experiential didactic techniques linked to higher entrepreneurial success (i.e., improved entrepreneurial survival rates) could provide valuable insights into creating effective entrepreneurial environments.

Moreover, we observed that within our sample, students specializing in business studies were more likely to start their own businesses than those in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) fields. The business students, who engage in a broader range of management and economics courses and seminars, may be more inclined toward entrepreneurship because of a higher PBC and stronger SNs associated with business venturing. In contrast, STEM students, with their focus on technical topics, may lack prior knowledge of the business world, potentially hindering their entrepreneurial intentions. Further research could investigate how STEM programs can better cultivate entrepreneurial skills in their students. Understanding the strengths and weaknesses of these programs in fostering specific types of entrepreneurial behaviors could inform the development of targeted workshops or seminars designed to enhance EIs among STEM students. Additionally, creating activities that facilitate collaboration between business and STEM students could encourage the formation of technology-driven or innovation-focused ventures, bridging the gap between technical expertise and entrepreneurial acumen.

Lastly, our research underscores the pivotal role of BICs as significant moderators in shaping EIs. Universities should prioritize establishing these platforms, equipped with the necessary resources, to cultivate a vibrant entrepreneurial ecosystem on campus. For BICs to be truly effective, it is essential that their staff possess the necessary expertise to mentor students, helping them develop the critical skills required for success as entrepreneurs after graduation. This involves organizing regular workshops and training sessions that cover various aspects of entrepreneurship, thereby enhancing students’ skill sets. These skills will offer essential guidance and support as students embark on their entrepreneurial journeys, increasing their chances of success.

While our findings indicate that the mere existence of such centers can drive EIs, it is essential to explore in greater detail which specific programs, activities, and resources are most critical for subsequent business venturing. Further research should focus on identifying and elucidating the key components of these platforms and their impact on enhancing the effectiveness of EEPs. This deeper understanding will help institutions design more targeted and impactful initiatives to foster entrepreneurship among students.

6. Conclusions

Entrepreneurial education has significantly expanded in recent decades, marked by the integration of entrepreneurship curricula into university programs, schools, and vocational training centers. This growth can be attributed to the recognition of the vital role that graduates with entrepreneurial skills play in stimulating economic growth and advancing their countries’ development. While prior empirical research has shown that entrepreneurship-related skills and attitudes can be cultivated through business education, these studies have primarily focused on more developed nations. Our findings indicate that incorporating entrepreneurship education leads to a significant increase in students’ entrepreneurial intentions. Additionally, our research highlights the critical role of BICs in supporting aspiring entrepreneurs.

Limitations and Further Research

The main limitations of this study are described as follows. Firstly, the study considers a cross-sectional approach, exploring the intentions and behaviors of individuals at a specific moment in time. Therefore, employing a longitudinal approach would be useful to quantify the enduring significance of motivational elements such as entrepreneurial learning programs and contextual institutions like BICs in fostering various entrepreneurial endeavors over time. Further research employing multiple measures and tracking the development of intentions could offer a more comprehensive understanding of how various motivational factors influence entrepreneurial intentions.

Moreover, the study focused on students enrolled in higher education programs, which raises the question of whether their intentions will actually lead to actions given their evolving career aspirations. An interesting avenue for further research would be to investigate whether individuals with strong entrepreneurial intentions pursue different types of entrepreneurial ventures, such as hybrid entrepreneurship. Additionally, the sample used in the study was skewed in terms of gender and age. Future studies should strive for a more balanced representation of genders and include participants from various age groups. Exploring how internal and contextual factors impact subgroups within these demographics could provide valuable insights to propose targeted public policies. Furthermore, the research was conducted solely in three major urban centers of Pakistan. Extending the research framework to countries with diverse institutional environments could help illuminate how macro-level factors influence EIs.

Additionally, our study used a convenience sample for data collection, which limits the scope of the socioeconomic factors analyzed. Future research should consider a more comprehensive research instrument that includes a broader range of socioeconomic information, allowing for a deeper analysis of the differences among various subgroups (e.g., gender, age, work experience, and family background). Furthermore, our study focused solely on students in HEIs in entrepreneurial programs and did not include a comparison group, such as unemployment or different forms of employment. Future research could address this gap by comparing the entrepreneurial intentions of HEI students with those from various other groups to assess how the factors we studied influence entrepreneurial intentions across different contexts.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/educsci14090983/s1, Questionnaire.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.A. and M.A.Z.; Data curation, T.A.; Formal analysis, T.A., J.A.D.T. and M.A.Z.; Funding acquisition, T.A., J.A.D.T. and P.H.; Investigation, T.A., J.A.D.T. and M.A.Z.; Methodology, T.A. and M.A.Z.; Project administration, T.A., J.A.D.T. and P.H.; Resources, T.A.; Software, T.A. and M.A.Z.; Supervision, T.A., J.A.D.T. and P.H.; Validation, T.A. and M.A.Z.; Visualization, T.A., J.A.D.T. and P.H.; Writing—original draft, T.A. and M.A.Z.; Writing—review and editing, J.A.D.T. and P.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The APC was funded by Universidad Católica de Temuco.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and obtained ethical approval from Arid Agriculture University Rawalpindi Faculty of Social Sciences (protocol code PMAS-AAUR/D.FOSS/1229 and date of approval 10 October 2023).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study directly from the survey form.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets presented in this article are not directly available because of ethical compliance. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Diaz Tautiva, J.A.; Salvaj, E.; Vásquez-Lavín, F.; Ponce Oliva, R.D. Understanding the Role of Institutions and Economic Context on Entrepreneurial Value Creation Choice. Oeconomia Copernicana 2023, 14, 405–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anjum, T.; Heidler, P.; Amoozegar, A.; Anees, R.T. The Impact of Entrepreneurial Passion on the Entrepreneurial Intention; Moderating Impact of Perception of University Support. Adm. Sci. 2021, 11, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fayolle, A.; Gailly, B. From Craft to Science: Teaching Models and Learning Processes in Entrepreneurship Education. J. Eur. Ind. Train. 2008, 32, 569–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Celume, S.A.B.; Rivera, F.I.R.; Diaz Tautiva, J.A.; Rivera, S.A.R.; Lecuna, A. Doing Well by Doing Good: Identity Conflict in an Indigenous Entrepreneur. In Contemporary Entrepreneurship: Global Perspectives and Cases; Hammoda, B., Durst, S., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2024; pp. 83–91. [Google Scholar]

- Diaz Tautiva, J.A.; Rivera, S.A.R.; Celume, S.A.B.; Rivera, F.I.R.; Lecuna, A. A Born-Global Entrepreneur in the PayTech Industry: Finding Opportunities and Capturing Value in International Markets. In Contemporary Entrepreneurship; Hammoda, B., Durst, S., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2024; pp. 28–37. [Google Scholar]

- Nabi, G.; Liñán, F. Graduate Entrepreneurship in the Developing World: Intentions, Education and Development. Educ.+Train. 2011, 53, 325–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Jorge-Moreno, J. Influencia Del Emprendimiento Sobre El Crecimiento Económico y La Eficiencia: Importancia de La Calidad Institucional y La Innovación Social Desde Una Perspectiva Internacional. Rev. Econ. Mund. 2017, 2017, 137–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hui-Chen, C.; Kuen-Hung, T.; Chen-Yi, P. The Entrepreneurial Process: An Integrated Model. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2014, 10, 727–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leiva, J.C.; Mora-esquivel, R.; Krauss-delorme, C.; Bonomo-odizzio, A.; Solıs-Salazar, M. Entrepreneurial Intention among Latin American University Students. Acad. Rev. Latinoam. Adm. 2020, 34, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giordano Martínez, K.R.; Fernández-Laviada, A.; Herrero Crespo, Á. Influence of Business Incubators Performance on Entrepreneurial Intentions and Its Antecedents during the Pre-Incubation Stage. Entrep. Res. J. 2018, 8, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zreen, A.; Farrukh, M.; Nazar, N.; Khalid, R. The Role of Internship and Business Incubation Programs in Forming Entrepreneurial Intentions: An Empirical Analysis from Pakistan. Cent. Eur. Manag. J. 2019, 27, 97–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nabi, G.; LiñáN, F.; Fayolle, A.; Krueger, N.; Walmsley, A. The Impact of Entrepreneurship Education in Higher Education: A Systematic Review and Research Agenda. Acad. Manag. Learn. Educ. 2017, 16, 277–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liñán, F. Intention-Based Models of Entrepreneurship Education. Piccolla Impresa/Small Bus. 2004, 3, 11–35. [Google Scholar]

- Liñán, F.; Fayolle, A. A Systematic Literature Review on Entrepreneurial Intentions: Citation, Thematic Analyses, and Research Agenda. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2015, 11, 907–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amorim Neto, R.d.C.; Rodrigues, V.P.; Stewart, D.; Xiao, A.; Snyder, J. The Influence of Self-Efficacy on Entrepreneurial Behavior among K-12 Teachers. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2018, 72, 44–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-González, J.A.; Kobylinska, U.; García-Rodríguez, F.J.; Nazarko, L. Antecedents of Entrepreneurial Intention among Young People: Model and Regional Evidence. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spillecke, S.B.; Brettel, M. The Impact of Sales Management Controls on the Entrepreneurial Orientation of the Sales Department. Eur. Manag. J. 2013, 31, 410–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anjum, T.; Ramzani, S.R.; Nazar, N. Antecedents of Entrepreneurial Intentions: A Study of Business Students from Universities of Pakistan. Int. J. Bus. Psychol. 2019, 1, 72–88. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Population Fund World Population Dashboard Pakistan. Available online: https://www.unfpa.org/data/world-population/PK (accessed on 31 May 2024).

- U.S. Department Of Commerce Pakistan—Country Commercial Guide. Available online: https://www.trade.gov/country-commercial-guides/pakistan-education (accessed on 31 May 2024).

- International Monetary Fund. Global Unemployment Rate 2024. Available online: https://www.imf.org/external/datamapper/LUR@WEO/PAK (accessed on 31 May 2024).

- Finance Division, Government of Pakistan. Pakistan Economic Survey 2023–24. Available online: https://finance.gov.pk/survey_2024.html (accessed on 31 May 2024).

- Ajzen, I. The Theory of Planned Behavior: Frequently Asked Questions. Hum. Behav. Emerg. Technol. 2020, 2, 314–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The Theory of Planned Behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dao, T.K.; Bui, A.T.; Doan, T.T.T.; Dao, N.T.; Le, H.H.; Le, T.T.H. Impact of Academic Majors on Entrepreneurial Intentions of Vietnamese Students: An Extension of the Theory of Planned Behavior. Heliyon 2021, 7, e06381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lortie, J.; Castogiovanni, G. The Theory of Planned Behavior in Entrepreneurship Research: What We Know and Future Directions. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2015, 11, 935–957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kautonen, T.; van Gelderen, M.; Fink, M. Robustness of the Theory of Planned Behavior in Predicting Entrepreneurial Intentions and Actions. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2015, 39, 655–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rideout, E.C.; Gray, D.O. Does Entrepreneurship Education Really Work? A Review and Methodological Critique of the Empirical Literature on the Effects of University-based Entrepreneurship Education. J. small Bus. Manag. 2013, 51, 329–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sels, H.L.M.; Debrulle, J.; Meuleman, M. Gender Effects on Entrepreneurial Intentions: A TPB Multi-Group Analysis at Factor and Indicator Level. In Proceedings of the Paper Presented at the Academy of Management Annual Meeting, Chicago, IL, USA, 7–11 August 2009; Volume 7, p. 11. [Google Scholar]

- Leroy, H.; Manigart, S.; Meuleman, M.; Collewaert, V. Understanding the Continuation of Firm Activities When Entrepreneurs Exit Their Firms: Using Theory of Planned Behavior. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2015, 53, 400–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishimura, J.S.; Tristan, O.M. Using The Theory Of Planned Behavior To Predict Nascent Entrepreneurship. Acad. Latinoam. Adm. 2011, 46, 55–71. [Google Scholar]

- Nabi, G.; Walmsley, A.; Liñán, F.; Akhtar, I.; Neame, C. Does Entrepreneurship Education in the First Year of Higher Education Develop Entrepreneurial Intentions? The Role of Learning and Inspiration. Stud. High. Educ. 2018, 43, 452–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fayolle, A.; Liñán, F. The Future of Research on Entrepreneurial Intentions. J. Bus. Res. 2014, 67, 663–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anjum, T.; Ramzani, S.R.; Farrukh, M.; Raju, V.; Nazar, N.; Shahzad, I.A. Entrepreneurial Intentions of Pakistani Students: The Role of Entrepreneurial Education, Creativity Disposition, Invention Passion & Passion for Founding. J. Manag. Res. 2018, 10, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bae, T.J.; Qian, S.; Miao, C.; Fiet, J.O. The Relationship Between Entrepreneurship Education and Entrepreneurial Intentions: A Meta-Analytic Review. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2014, 38, 217–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrukh, M.; Lee, J.W.C.; Sajid, M.; Waheed, A. Entrepreneurial Intentions The Role of Individualism and Collectivism in Perspective of Theory of Planned Behaviour. Educ.+Train. 2019, 67, 984–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, L.; Wong, P.; Ho, Y. Entrepreneurship Propensities: The Influence of Self-Efficacy, Opportunity Perception, and Social Networks. In Proceedings of the First Research GEM Conference, Berlin, Germany, 1–3 April 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Henley, A. Does Religion Influence Entrepreneurial Behaviour? Int. Small Bus. J. 2016, 35, 597–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Y.-Y.; Wannamakok, W.; Kao, C.-P. Entrepreneurship Education, Academic Major, and University Students’ Social Entrepreneurial Intention: The Perspective of Planned Behavior Theory. Stud. High. Educ. 2022, 47, 2204–2223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carpenter, A.; Wilson, R. A Systematic Review Looking at the Effect of Entrepreneurship Education on Higher Education Student. Int. J. Manag. Educ. 2022, 20, 100541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rauch, A.; Hulsink, W. Putting Entrepreneurship Education Where the Intention to Act Lies: An Investigation into the Impact of Entrepreneurship Education on Entrepreneurial Behavior. Acad. Manag. Learn. Educ. 2015, 14, 187–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez, J.P.; Martins, I.; Mahauad, M.D.; Sarango-Lalangui, P.O. A Bridge between Entrepreneurship Education, Program Inspiration, and Entrepreneurial Intention: The Role of Individual Entrepreneurial Orientation. Evidence from Latin American Emerging Economies. J. Entrep. Emerg. Econ. 2024, 16, 288–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsheke, O.; Dhurup, M. Entrepreneurial-Related Programmes and Students’ Intentions to Venture into New Business Creation: Finding Synergy of Constructs in a University of Technology. Sci. Technol. Soc. 2017, 22, 259–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heuer, A.; Kolvereid, L. Education in Entrepreneurship and the Theory of Planned Behaviour. Eur. J. Train. Dev. 2014, 38, 506–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maresch, D.; Harms, R.; Kailer, N.; Wimmer-Wurm, B. The Impact of Entrepreneurship Education on the Entrepreneurial Intention of Students in Science and Engineering versus Business Studies University Programs. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2016, 104, 172–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paray, Z.A.; Kumar, S. Does Entrepreneurship Education Influence Entrepreneurial Intention among Students in HEI’s?: The Role of Age, Gender and Degree Background. J. Int. Educ. Bus. 2020, 13, 55–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krueger, N.F.; Carsrud, A.L. Entrepreneurial Intentions: Applying the Theory of Planned Behaviour. Entrep. Reg. Dev. 1993, 5, 315–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterman, N.E.; Kennedy, J. Enterprise Education: Influencing Students’ Perceptions of Entrepreneurship. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2003, 28, 129–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimi, S.; Biemans, H.J.A.; Lans, T.; Chizari, M.; Mulder, M. The Impact of Entrepreneurship Education: A Study of Iranian Students’ Entrepreneurial Intentions and Opportunity Identification. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2016, 54, 187–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ljunggren, E.; Kolvereid, L. New Business Formation: Does Gender Make a Difference? Women Manag. Rev. 1996, 11, 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iakovleva, T.; Kolvereid, L.; Stephan, U. Entrepreneurial Intentions in Developing and Developed Countries. Educ. Train. 2011, 53, 353–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, R.; Liu, Z.; Zhao, G.; Huang, Z.; Yu, Q. The Impact of Institutional Management on Teacher Entrepreneurship Competency: The Mediating Role of Entrepreneurial Behaviour. Int. J. Manag. Educ. 2023, 21, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehman, W.; Yosra, A.; Khattak, M.S.; Fatima, G. Antecedents and Boundary Conditions of Entrepreneurial Intentions: Perspective of Theory of Planned Behaviour. Asia Pacific J. Innov. Entrep. 2023, 17, 46–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olugbola, S.A. Exploring Entrepreneurial Readiness of Youth and Startup Success Components: Entrepreneurship Training as a Moderator. J. Innov. Knowl. 2017, 2, 155–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajike, E.O.; Goodluck, N.K.; Hamed, A.B.; Onyia, V.A.; Kwarbai, J.D. Entrepreneurship Education and Entrepreneurial Intentions the Role of Theory of Planned Behavior. Int. J. Adv. Res. Soc. Eng. Dev. Strateg. 2015, 3, 118–135. [Google Scholar]

- Aliedan, M.M.; Elshaer, I.A.; Alyahya, M.A.; Sobaih, A.E.E. Influences of University Education Support on Entrepreneurship Orientation and Entrepreneurship Intention: Application of Theory of Planned Behavior. Sustainability 2022, 14, 13097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asghar, M.Z.; Hakkarainen, P.S.; Nada, N. An Analysis of the Relationship between the Components of Entrepreneurship Education and the Antecedents of Theory of Planned Behavior. Pakistan J. Commer. Soc. Sci. 2016, 10, 45–68. [Google Scholar]

- Franco, M.; Haase, H.; Lautenschläger, A. Students’ Entrepreneurial Intentions: An Inter-Regional Comparison. Educ.+Train. 2010, 52, 260–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerrero, M.; Urbano, D.; Gajon, E. Entrepreneurial University Ecosystems and Graduates’ Career Patterns: Do Entrepreneurship Education Programmes and University Business Incubators Matter? J. Manag. Dev. 2020, 39, 753–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, A.J.; Monsen, E. Teaching Technology Commercialization: Introduction to the Special Section. J. Technol. Transf. 2014, 39, 774–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanderstraeten, J.; Matthyssens, P. Service-Based Differentiation Strategies for Business Incubators: Exploring External and Internal Alignment. Technovation 2012, 32, 656–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boukamcha, F. Impact of Training on Entrepreneurial Intention: An Interactive Cognitive Perspective. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2015, 27, 593–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutagalung, B.; Dalimunthe, D.M.J.; Pambudi, R.; Hutagalung, A.Q.; Muda, I. The Effect of Enterpreneurship Education and Family Environment towards Students’ Entrepreneurial Motivation. Int. J. Econ. Res. 2017, 14, 331–348. [Google Scholar]

- Qureshi, S.; Mian, S. Transfer of Entrepreneurship Education Best Practices from Business Schools to Engineering and Technology Institutions: Evidence from Pakistan. J. Technol. Transf. 2021, 46, 366–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Dajani, H.; Carter, S.; Shaw, E.; Marlow, S. Entrepreneurship among the Displaced and Dispossessed: Exploring the Limits of Emancipatory Entrepreneuring. Br. J. Manag. 2015, 26, 713–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerrero, M.; Urbano, D.; Gajon, E. Higher Education Entrepreneurial Ecosystems: Exploring the Role of Business Incubators in an Emerging Economy. Int. Rev. Entrep. 2017, 15, 175–202. [Google Scholar]

- Skute, I. Opening the Black Box of Academic Entrepreneurship: A Bibliometric Analysis. Scientometrics 2019, 120, 237–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nabi, G.; Holden, R.; Walmsley, A. Entrepreneurial Intentions among Students: Towards a Re-Focused Research Agenda. J. Small Bus. Enterp. Dev. 2010, 17, 537–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roncancio-Marin, J.J.; Dentchev, N.A.; Guerrero, M.; Diaz-Gonzalez, A.A. Shaping the Social Orientation of Academic Entrepreneurship: An Exploratory Study. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2022, 28, 1679–1701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerrero, M.; Urbano, D.; Fayolle, A. Entrepreneurial Activity and Regional Competitiveness: Evidence from European Entrepreneurial Universities. J. Technol. Transf. 2016, 41, 105–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeed, S.; Yousafzai, S.Y.; Yani-De-Soriano, M.; Muffatto, M. The Role of Perceived University Support in the Formation of Students’ Entrepreneurial Intention. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2015, 53, 1127–1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mungila Hillemane, B.S.; Satyanarayana, K.; Chandrashekar, D. Technology Business Incubation for Start-up Generation: A Literature Review toward a Conceptual Framework. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2019, 25, 1471–1493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etikan, I.; Musa, S.A.; Alkassim, R.S. Comparison of Convenience Sampling and Purposive Sampling. Am. J. Theor. Appl. Stat. 2016, 5, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liñán, F.; Chen, Y.-W. Development and Cross-Cultural Application of a Specific Instrument to Measure Entrepreneurial Intentions. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2009, 33, 593–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, T.; Chandran, V.G.R.; Klobas, J.E.; Liñán, F.; Kokkalis, P. Entrepreneurship Education Programmes: How Learning, Inspiration and Resources Affect Intentions for New Venture Creation in a Developing Economy. Int. J. Manag. Educ. 2020, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrukh, M.; Alzubi, Y.; Shahzad, I.A.; Waheed, A.; Kanwal, N. Entrepreneurial Intentions: The Role of Personality Traits in Perspective of Theory of Planned Behaviour. Asia Pacific J. Innov. Entrep. 2018, 12, 399–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anjum, T.; Amoozegar, A.; Farrukh, M.; Heidler, P. Entrepreneurial Intentions among Business Students: The Mediating Role of Attitude and the Moderating Role of University Support. Educ. Train. 2023, 65, 587–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meru, A.K.; Struwig, M. An Evaluation of the Entrepreneurs’ Perception of Business-Incubation Services in Kenya. Int. J. Bus. Adm. 2011, 2, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manley, S.C.; Hair, J.F.; Williams, R.I.; McDowell, W.C. Essential New PLS-SEM Analysis Methods for Your Entrepreneurship Analytical Toolbox. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2020, 17, 1805–1825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anjum, T.; Sharifi, S.; Nazar, N.; Farrukh, M. Determinants of Entrepreneurial Intention in Perspective of Theory of Planned Behaviour. Manag. Theory Stud. Rural Bus. Infrastruct. Dev. 2018, 40, 429–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair Jr, J.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.; Gudergan, S. Advanced Issues in Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2017; ISBN 1483377385. [Google Scholar]

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A New Criterion for Assessing Discriminant Validity in Variance-Based Structural Equation Modeling. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2015, 43, 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, W.W. Modern Methods for Business Research. Mod. Methods Bus. Res. 1998.

- Hair, J., Jr.; Hult, G.; Ringle, C.; Sarstedt, M. A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM); Sage publications: New York, NY, USA, 2021; ISBN 1544396333. [Google Scholar]

- Farrukh, M.; Khan, A.A.; Shahid Khan, M.; Ravan Ramzani, S.; Soladoye, B.S.A. Entrepreneurial Intentions: The Role of Family Factors, Personality Traits and Self-Efficacy. World J. Entrep. Manag. Sustain. Dev. 2017, 13, 303–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimi, S. The Role of Entrepreneurial Passion in the Formation of Students’ Entrepreneurial Intentions. Appl. Econ. 2020, 52, 331–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimi, S.; Biekmans, J.H.; Mahdei, K.N.; Lans, T.; Mohammed, C.; Mulder, M. Testing the Relationship between Personality Characteristics, Contextual Factors and Entrepreneurial Intentions in a Developing Country. Int. J. Psychol. 2017, 52, 227–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).