Abstract

The expansion of English medium instruction (EMI) in higher education has generated significant scholarly interest, resulting in an increasing body of research across different contexts. This bibliometric study examines 1522 publications in the Scopus database to explore the intellectual, conceptual, and social structure of the EMI literature in higher education. Findings revealed substantial growth in publications and citations between 1974 and 2024, showing a notable increase in productivity after 2018. Most cited authors focus on EMI within their affiliated country, but some affiliated with British universities have made global contributions. The field exhibits global coverage, albeit with strong dominance by China, Spain, the UK, Australia, and Hong Kong, as well as limited representation from African nations, barring South Africa. EMI networks are primarily driven by authors’ current and past institutional affiliations as well as geographical proximity, with the UK, Spain, and China emerging as leaders in these networks. The most productive journals focus on multilingualism, bilingualism, language policy, teaching, and learning while also encompassing higher education and multidisciplinary areas. Key topics signal a shift towards translanguaging and classroom interaction. Under-researched areas include (post)colonialism and EMI implementation. These findings provide a comprehensive insight into the evolving landscape of EMI research and potential future directions.

1. Introduction

English medium instruction (EMI) has emerged as a prominent pedagogical approach in higher education in non-English speaking contexts [1,2] since the 1990s [3]. With globalisation and the influence of neoliberal policies, universities worldwide have been increasingly adopting EMI as part of their internationalisation efforts [4]. However, as demonstrated by the extant empirical evidence, motivations for EMI adoption vary and are context-dependent [5]. Governments and higher education institutions anticipate that EMI will help achieve a wide range of goals, such as producing globally competitive graduates, internationalising education, and elevating the status of educational systems within the context of English as a globalising language [4,6,7].

As EMI has evolved into a global phenomenon, its implementation has raised pedagogical, policy-related, and socio-political concerns [3,8]. Bowles and Murphy describe EMI as the “elephant in the internationalisation room” ([9], p. 8), stressing the crucial need for research and policy intervention. They, along with other scholars, argue that the spread of EMI has outpaced research, emphasising the need for more evidence-based studies focused on the teaching and learning processes of EMI [9].

The growing use of EMI in higher education has sparked significant scholarly interest, resulting in an increasing body of research across different contexts [3,8,10,11]. A synthesis of this field is necessary to guide future research, evidence-based practices, and policy decisions. While various methods exist for systematically synthesising research, they all share the core principles of using a clear methodology to ensure transparency, reproducibility, and the ability to update reviews [12]. Systematic and bibliometric reviews share these principles, but they differ in focus and scope. Systematic reviews are best suited for niche areas because of their narrow focus and coverage of often small data sets. On the other hand, bibliometric reviews are better equipped to map extensive bibliometric data. They showcase intellectual structures and emerging trends within research fields using quantitative techniques and specialist software, thus reducing the potential for interpretation biases commonly seen in qualitative systematic reviews [13].

Scholars have attempted to synthesise the EMI field through systematic and critical reviews. However, they focus on specific topics with findings drawn from a limited number of studies. For example, Jablonkai and Hou [14] mapped EMI practices and challenges within Chinese higher education, examining 42 papers. Meanwhile, Dang et al. [15] focused on the professional learning of educators engaged in EMI within higher education across multiple countries, reviewing 115 papers. Pun et al. [16] examined language challenges and coping strategies within EMI science classrooms using 66 articles. Macaro et al.’s [17] geographically comprehensive systematic review covered 83 studies to unveil stakeholders’ concerns about EMI implementation.

While the existing limited review studies provide valuable insights, they often focus on specific aspects of EMI or individual regions, underscoring the necessity to structure the knowledge to navigate the vast multidisciplinary literature, understand its underlying trends, and identify emerging areas of inquiry. Bibliometric reviews, known for their replicable and transparent methods, offer a comprehensive assessment of extensive publication datasets at both macroscopic and microscopic levels, facilitating systematic exploration and analysis of the evolving field [18]. Although Wu and Tsai [19] and Zhu and Wang [20] have attempted to map the field, their bibliometric analyses of slightly over 100 publications in the Web of Science database provide limited insights due to their restricted timeframe, narrow focus, and limited analytical methods. The current study overcomes these limitations by examining the EMI research corpus of 1522 publications to offer a comprehensive perspective regarding the evolution and development of EMI research in higher education. Employing the Scopus database and bibliometric analysis, the paper maps the intellectual, conceptual, and social landscape of EMI research to reveal current trends and anticipate future directions.

The following research questions guided the study:

- What are the major trends in publication output and citation impact in the field of EMI over 50 years? Which authors, organisations, and countries are the most prolific in producing research on EMI?

- What are the influential publications and core journals that lead the development of EMI research?

- What is the intellectual structure of the EMI field in regard to authors?

- What is the social structure of EMI research with respect to authorship, collaboration patterns, and regional contribution?

- What is the conceptual structure of this field concerning keywords and focal topics, and how have the key research topics evolved over time?

Before describing the study methods and findings, we first provide a concise review of EMI literature that forms the foundation of the study inquiry.

2. Literature Review

The implementation of EMI policies in higher education has garnered significant scholarly attention, resulting in a rich body of literature that explores its multifaceted dimensions ranging from the macro-level issues on local linguistic ecology and the overall landscape of higher education to meso-level issues concerning university internationalisation strategies to enhance institutional status and the micro-level impact of EMI on content and language learning outcomes [21]. Thus, the extant research allows discussions of terminological issues, pedagogical implications, institutional challenges, and socio-political impacts of EMI.

2.1. Terminological Issues of EMI

Although EMI has evolved into a global phenomenon, its interpretation remains fluid, illustrating the dynamic nature and adaptability of educational practices [5]. The diverse manifestations of EMI can vary within the same educational institution, country, or region [2,11]. Macaro et al. [17] highlighted variations in EMI terminology, such as immersion or content-based language education in North America and content and language integrated learning (CLIL) or English-taught programmes mainly in Europe. While some scholars equate CLIL and EMI [22], others argue that CLIL is a distinct form of English language teaching rather than EMI [23]. This lack of consensus is evident in the literature, with scholars continuing to debate and define the EMI terminology [1].

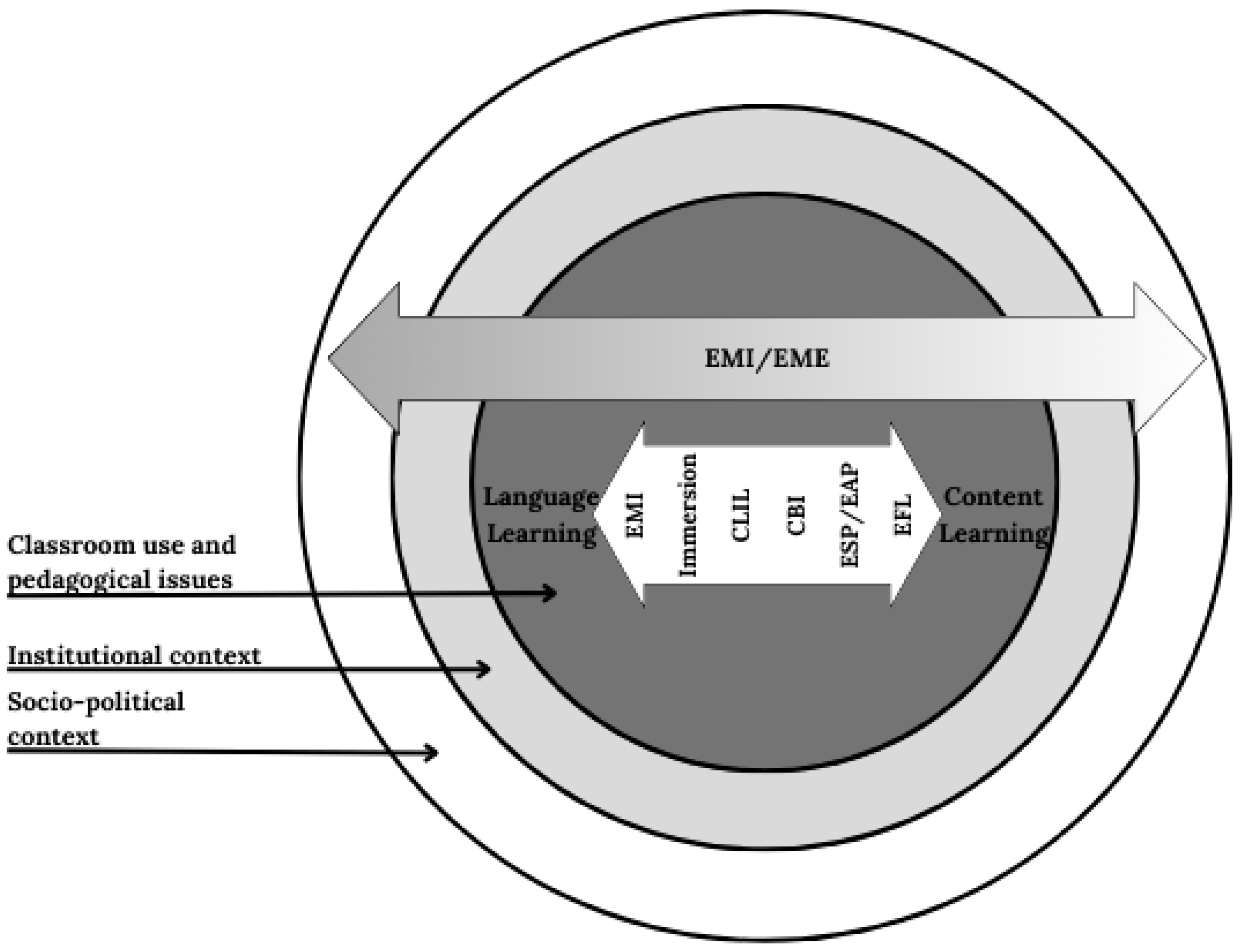

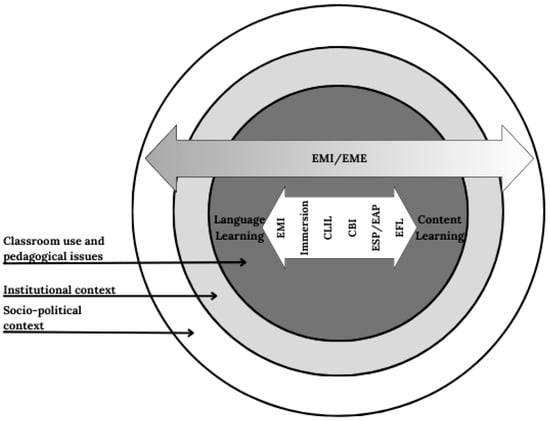

Other scholars suggest conceptualising EMI as the use of English in content learning, shifting the emphasis from language acquisition to content comprehension along a continuum [5,24]. Figure 1 visually represents the terminological perspective adopted in this study. Positioned at the centre are varied terminologies highlighting the diverse ways English is utilised in classrooms. While EMI refers to English usage emphasising content delivery within the classroom, scholars also extend this concept alongside English-medium education (EME) to address the broader institutional and socio-political applications of English in higher education settings. This research aims to delve deeper into EMI literature, moving beyond classroom-specific concerns to explore a wide array of issues. As such, we do not focus on terminologies across the spectrum. Aligning with these distinct interpretations, our study defines EMI as an umbrella term encompassing English use in educational settings, primarily focusing on content delivery, thereby excluding its alternative designations from our search parameters. Furthermore, our investigation also encompasses EME as the issues surrounding EMI transcend the classroom, necessitating a broader examination as detailed in subsequent sections.

Figure 1.

Terminological conceptualisation of EMI. Note. The illustration of the Language Learning Continuum in the centre of the Figure is adapted from Thompson and McKinley ([24], p. 3).

On the left side of the continuum lies EMI, which exclusively focuses on content, followed by immersion, CLIL, content-based instruction (CBI), English for Specific/Academic Purposes (ESP/EAP), and English as a Foreign Language (EFL), where the focus shifts towards language. Thus, Macaro asserts that EMI is the commonly used term in non-English speaking regions, defining it as ‘the use of the English language to teach academic subjects (other than English itself) in countries or jurisdictions in which the majority of the population’s first language is not English’ ([5], p. 10). Alternatively, recognising the multifaceted nature of EMI, Dafouz and Smit introduced the term English-Medium Education (EME) to provide a broader semantic scope without specifying “a particular pedagogical approach or research agenda” ([25], p. 399). The variability in the terminology used for this concept complicates the work of researchers conducting a comprehensive analysis of the field’s literature, as they must navigate not only the diverse applications of the same concept but also the various terms representing similar meanings. However, in line with these differing conceptualisations, our study concentrates on EMI as an instructional approach centred on content, hence excluding its alternative names from the search criteria. We are broadening our focus to EME because the challenges and issues associated with EMI extend beyond the confines of the classroom setting. This broader perspective will be elaborated upon in the upcoming sections.

2.2. Pedagogical Issues of EMI

The impact of EMI on educational stakeholders has drawn extensive attention in the research [22,26]. Scholars highlight that insufficient English proficiency among faculty and students is the most concerning issue among all [27]. EMI teachers’ linguistic challenges can hinder effective content delivery, while students may struggle with comprehending complex academic material in a non-native language [5,21,27,28]. In regions where English proficiency levels are generally low, EMI can pose significant challenges for both students and instructors, potentially leading to lower educational outcomes [29]. To address the challenges experienced within the classroom setting, studies recommend enhancing EMI delivery by providing professional development opportunities for teachers [30,31]. Specifically, McKinley and Rose [32] advocate for targeted language support and professional development programmes for instructors. Most importantly, scholars argue that the training should extend beyond simply improving English language proficiency [33]. Such policy interventions indeed require a context-oriented approach. Dafouz and Smit [25] emphasise the influence of discipline-specific knowledge practices, agent expectations, and individual experiences on effective EMI implementation. Similarly, Kuteeva and Airey [34] argue that the knowledge structure of disciplines should be considered to understand how it impacts educational objectives and practices in EMI.

However, the opportunities for enhancing teacher qualification, as well as pre-service training specifically designed for EMI teachers, are rarely observed in practice [30]. This raises questions on the implementational aspect of language-in-education planning, where such a significant aspect of the policy is ignored. The absence of targeted training for EMI teachers may be rooted in the monolingual ideology that many practitioners share. Numerous studies report that the language aspect in EMI pedagogy is neglected by many practitioners [35,36,37]. For example, often, guided by monolingual ideology, the use of translanguaging is perceived as shame and guilt, whereas it has proven to be a supportive tool in the EMI environment [28,38]. Therefore, teaching in English necessitates the adjustment of teachers’ practices to the specific linguistic environment of EMI classrooms and underscores the importance of considering teacher training programmes [39,40].

Evidently, challenges in implementing EMI extend beyond teachers’ abilities and the classroom setting to encompass policy planning. In this regard, scholars have emphasised the importance of exploring EMI implementation practices and their consequences across educational levels (e.g., [41]).

2.3. The Institutional Context for EMI

While universities’ motivations to expand EMI usage may differ depending on the specific context, a fundamental driver behind this trend is the perceived need for internationalisation, leading universities to join the EMI race [17]. However, scholars have observed that the institutionalisation of EMI policies often encounters significant obstacles. It has been noted that the introduction and implementation of EMI policies have predominantly been top-down, often lacking input from those responsible for their enactment [16,42]. Consequently, this approach may lead to instances of resistance [43], while in some cases, non-compliance with EMI policies has resulted in penalties [4].

In this regard, nearly two decades ago, Coleman called for attention to the implementation problems associated with the “inexorable increase in the use of English” ([44], p. 1). Subsequent research has reinforced the ongoing nature of this issue (e.g., [21,28,45,46,47] and others). For instance, Jiang et al. [21] observed shortcomings in EMI programmes within Chinese tertiary education, noting that these initiatives, intended to bolster internationalisation efforts, remain underdeveloped. Dearden [46] further noted the tendency of universities to adopt EMI without a coherent strategic framework, resulting in inconsistent application and varying degrees of success. To address these gaps, Dearden [46] stressed the importance of institutions establishing comprehensive frameworks encompassing language support systems, faculty training programmes and continuous monitoring mechanisms for effective policy implementation.

Additionally, Dafouz and Smit [25] introduced the ROAD-MAPPING framework, an acronym representing essential dimensions for successful EMI integration: Roles of English, Academic Disciplines, (language) Management, Agents, Practices, and Processes, and Internationalisation and Glocalisation. This comprehensive model offers guidance to institutions in aligning their EMI strategies with their particular educational environments. Notably, case studies elucidate the regional nuances in EMI implementation, emphasising the need for contextualisation. For example, Hu and Lei’s [48] examination of EMI in Chinese universities underscores the government’s pivotal role in promoting EMI as part of the internationalisation agenda, necessitating tailored approaches that account for each institution’s linguistic and cultural specificities. In Europe, research by Airey [35] focuses on EMI in Swedish universities, emphasising the importance of disciplinary literacy and the integration of language and content learning. Airey’s findings suggest that effective EMI implementation requires collaboration between language and content specialists to develop pedagogical strategies that address both linguistic and disciplinary demands. In this regard, Bolton et al. caution against “quasi-context-free” ([49], p. 7) approaches to EMI that attempt to create universally applicable models, arguing that such approaches limit the scope of research. They promote a World Englishes perspective on EMI, which highlights the importance of local context in determining the dynamics of EMI implementation across different regions. This approach advocates for a shift from narrowly focused educational frameworks to a broader view that thoroughly incorporates context and interpretation.

2.4. Socio-Political Context of EMI

Since policy decisions regarding the medium of instruction can result in both intended and unintended consequences [50], researchers have extensively examined the driving forces behind EMI adoption in higher education. These studies place EMI strategies in the wider contexts of neoliberalism and transnational higher education [4,41]. This contrasts with the integration of EMI in school education, which historically stemmed from colonial imperatives aiming to train a select cadre of elite administrators to oversee colonised territories [51], notably observed in regions such as Sub-Saharan Africa [52,53,54], South-East Asia [5], and South Asia [55]. Conversely, the adoption of EMI policies in higher education has been primarily driven by the forces of globalisation.

The implementation of EMI in higher education often aligns with national agendas seeking to globalise education and bolster international competitiveness [1,48]. Motivated by pragmatic considerations, stakeholders generally exhibit positive attitudes towards EMI [41], although apprehensions persist regarding language barriers [17]. Furthermore, growing concerns have surfaced regarding the potential erosion of national identities and languages, heightening worries about linguistic imperialism led by English through EMI practices [56]. The diffusion of English via EMI under neoliberal policies has sparked unease over the escalating dominance of English at the expense of local languages, cultures, and traditional knowledge, potentially undermining national identities [8]. This tension is evident in many countries where policymakers grapple with striking a balance between reaping the benefits of English proficiency and safeguarding local languages and cultural heritage [57,58].

The implementation of EMI can also exacerbate socio-economic disparities within a country [8] since EMI has been associated with elite education [29]. Dearden [46] highlights that access to quality EMI programmes is often limited to students from affluent backgrounds who can afford the associated costs, such as private tutoring and study materials. This can create an inequitable educational environment where students from lower socio-economic backgrounds are disadvantaged.

Overall, the literature on EMI underscores the complexity and multifaceted nature of this educational approach. Scholars (e.g., [11,49]) agree on the need for comprehensive, context-sensitive strategies that address the linguistic, pedagogical, institutional, and socio-cultural dimensions of EMI. By adopting holistic frameworks and promoting collaborative efforts among stakeholders, institutions can navigate the challenges of EMI implementation and harness its potential benefits for students and faculty alike.

3. Materials and Methods

The study employed a bibliometric approach to map the research literature on EMI using metadata extracted from Scopus. This database was selected for its broad interdisciplinary coverage [59] and to ensure the comprehensiveness of the dataset, as our preliminary search across Web of Science and Scopus databases indicated that Scopus contains approximately 1000 more publications.

3.1. Search Strategy and Dataset

The dataset for bibliometric analysis was retrieved in the first week of July 2024. Since the use of the concept is inconsistent, various combinations and synonyms of the primary keyword “English medium of instruction” were tested to optimise the retrieval of a greater number of relevant sources. Similarly, to further limit the dataset to the higher education field, respective keywords were selected for the search. The search was performed in an advanced query mode encompassing the title, keywords, and abstract fields without any inclusion or exclusion criteria. Consequently, the search string on the “Topic” field, utilising the Boolean operator “OR”, was as follows:

“English as (—/a/the) medium of instruction” OR “English medium (—/of) instruction” OR “English as (—/a/the) language of instruction” OR “English language of instruction” OR “English medium teaching” OR “English taught program*” OR “English medium education” AND “universit*” OR “higher education” OR “graduate*” OR “college*” OR “tertiary education” OR “lecturer*” OR “professor*” OR “undergraduate*”

The initial search returned 1638 publications. Subsequently, we refined the results to encompass only peer-reviewed journal articles, books, and book chapters. We excluded review papers to prevent potential distortion in bibliometric analysis due to their high citation rates, as well as proceeding papers to avoid duplication with subsequently published works that might still be under development [18]. No restrictions were imposed regarding the time period or language to ensure all relevant scientific production in this study area was covered.

Following the search strategy steps, we exported 1522 publications from Scopus in .csv format (Table 1). For every document retrieved, we extracted detailed metadata such as the paper’s title, publication year, journal, citation count, authors’ names, affiliations and countries, authors’ keywords, funding sources, and cited references.

Table 1.

The data corpus.

3.2. Data Analysis

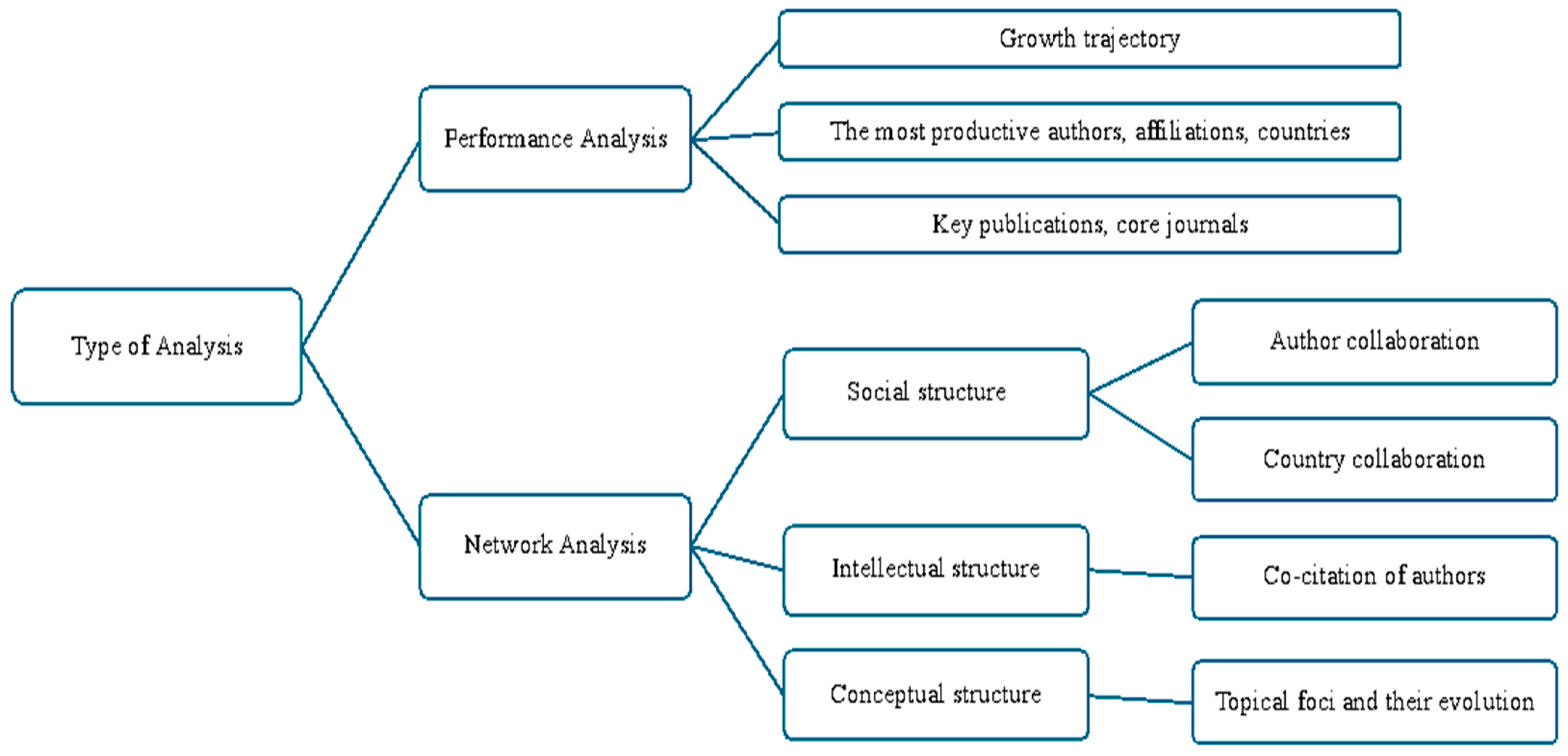

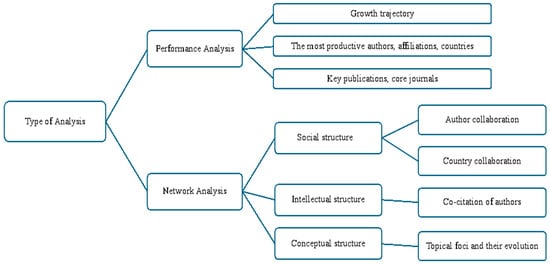

The bibliometric analysis utilised performance and network analyses to offer a comprehensive overview of the field [18]. Figure 2 presents the analytical framework employed, aligning with the research questions posed in Section 1. Performance and citation analyses tracked the field’s growth trajectory, highlighting science evolution and key publications, core journals, and influential countries, organisations, and authors.

Figure 2.

The analytical framework.

The network analysis explored the social, intellectual, and conceptual structures within the field, utilising VOSViewer (Version 1.6.19) to generate and visualise bibliometric maps to study the international publication landscape [60]. VOSViewer was chosen for its functionality and usefulness in developing and visualising networks and relationships [60].

Within the social analysis, we explored the collaboration network between authors and countries to understand the main research collaboration in this field, their respective research directions, and the interconnectedness between different authors and countries. The co-citation analysis of authors was conducted to examine the intellectual structure of the EMI field, followed by a co-occurrence analysis of all keywords to visualise a topical focus map and understand thematic evolution within the field. This approach enabled us to identify the evolution of topics and dominant themes from historical and contemporary perspectives, enabling us to forecast future research trends.

4. Findings

4.1. The Growth Trajectory of the EMI Research Corpus

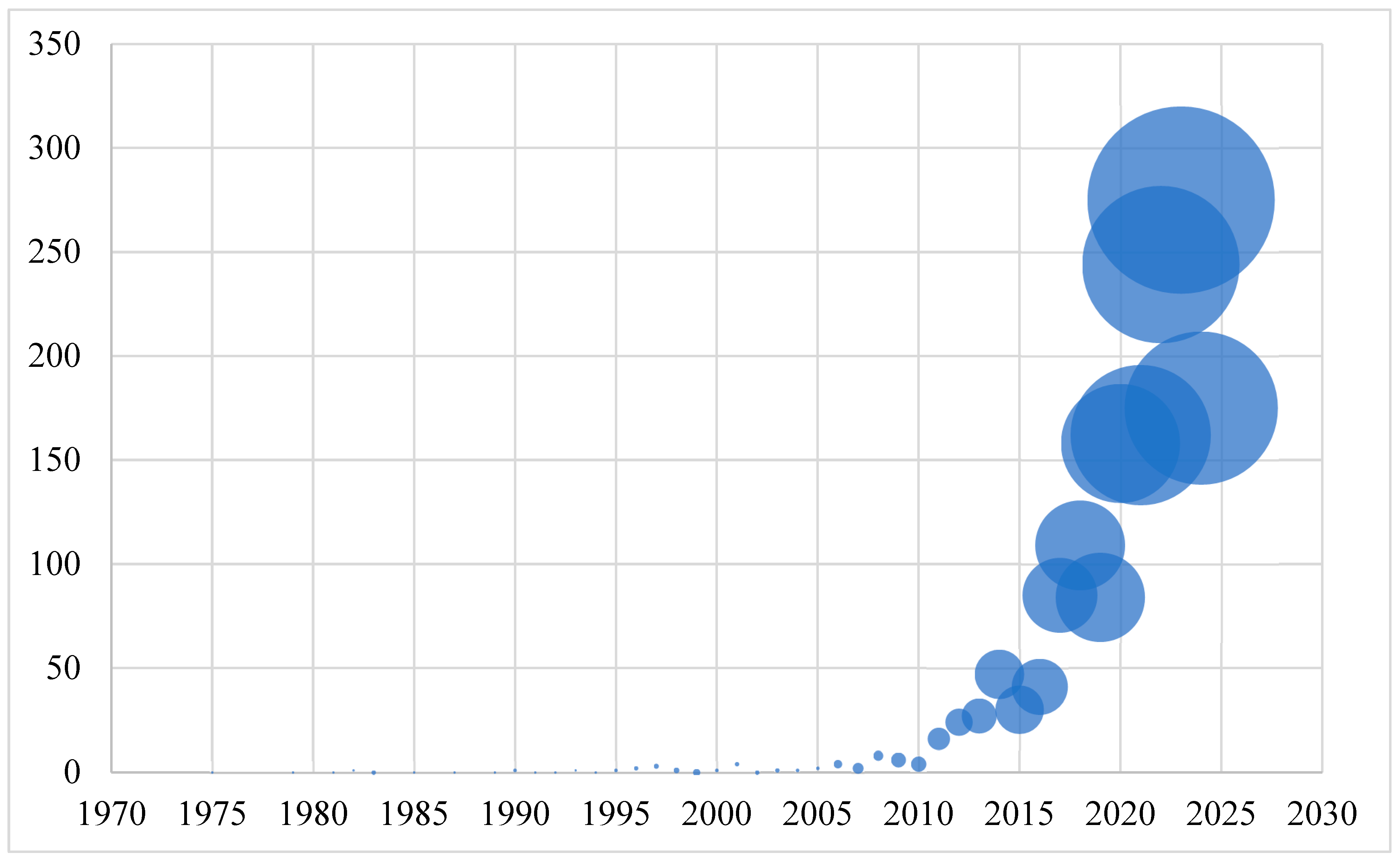

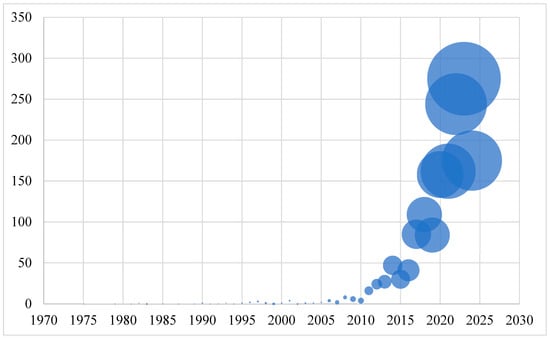

The fluctuations in publications and citations annually are critical indicators of scholarly communication, illustrating the evolution of research trends and the impact of academic work within a specific field. The dataset encompassed 1522 publications, comprising 1100 articles, 372 book chapters, and 50 books, spanning from 1974 to mid-2024 (Table 1). Altogether, this body of work has collectively garnered 22,052 citations. Figure 3 depicts the dynamic growth of publications and citations over the specified time frame. The circle’s size indicates the citation growth, while its position along the Y-axis corresponds to the growth of publications.

Figure 3.

Publication and citation growth of research.

Overall, the analysis indicates that there has been a significant increase in both the production and impact of research publications in recent years, particularly from 2018 onwards. The year 2023 has been the most productive and impactful, with 275 articles published, accumulating a total of 5155 citations. The exponential growth in publications and citations indicates that the rising prevalence of EMI in higher education aligns with a growing acknowledgement of the significance of research in this field within the academic community.

4.2. The Most Productive Authors, Affiliations and Countries

To explore the highly productive authors, affiliations and countries in the field of EMI, we analysed the list of authors, universities, and regions with the highest number of publications. Overall, there are 1322 authors contributing to 1522 publications in the corpus. Table 2 displays twenty scholars with the highest number of publications in the EMI field. As evident from Table 2, the field of EMI in higher education has been significantly shaped by the contributions of a group of top productive scholars such as D. Lasagabaster, H. Rose, S. Curle, K. Bolton, and W. Botha, among others. The leading authors represent diverse geographical backgrounds and affiliations. The University of the Basque and the University of Oxford have multiple authors among the top contributors, underscoring the prominence of EMI research within these institutions.

Table 2.

Leading authors ranked by the number of publications.

Table 3 showcases the twenty most productive affiliations, representing institutions from 13 countries and reflecting a worldwide interest and engagement in EMI research. Predominantly, institutions from Hong Kong and the UK dominate the list, with additional strong showings from European (Denmark, Sweden, and Spain) and Asian (Kazakhstan, China, Japan, Singapore, Taiwan, and Malaysia) universities, as well as contributions from Australia and Colombia. The University of Oxford leads with 45 publications, followed by Nazarbayev University from Kazakhstan with 36 publications. The University of Macau, based in China, secures the third spot with 31 publications. Notably, a diverse representation of institutions from Europe, Asia, and other regions further enriches the list of leading affiliations, emphasising the global nature of this research endeavour. Nazarbayev University stands as a significant representative of the post-Soviet region.

Table 3.

Leading affiliations by the number of publications.

Table 4 outlines the 20 most productive countries out of 88 nations contributing to EMI research, showcasing the global distribution of research output in this field. China leads with 162 articles, representing 10.62% of the total, and has a noteworthy influence with 1412 citations. Spain ranks second with 110 articles, indicating a high level of research activity relative to its academic community size and demonstrating significant research impact with 2014 citations. The UK follows in third place with 101 articles and the highest citation count of 2457. Despite being known for its dominance in many research fields [61], the USA ranks only tenth in research productivity with 31 publications, though its research tends to be highly influential with 639 citations.

Table 4.

The leading countries in the number of publications.

Asia, excluding China, contributes significantly to EMI research, accounting for approximately 16.4% of total publications. While Asian nations together account for approximately 27.1% of EMI output, Western countries such as the UK, USA, Spain, Australia, and Canada collectively contributed 25.4% of the publications. The surge in publication output from Asian countries may signal a focus on knowledge-based economies or government initiatives supporting EMI development. The presence of English-speaking nations in research output underscores their commitment to academic excellence and collaborative research, especially with countries prioritising EMI initiatives. Interestingly, among 26 sub-Saharan African countries that have adopted English as an official language [62], only South Africa appeared in the list of countries leading in EMI research with 13 publications and 138 citations.

4.3. Key Publications and Core Journals

The foundational publications on EMI are presented in Table 5. These top 20 highly cited publications collectively account for approximately 11.5% of all citations in the field. As evident from the titles, the highly cited publications cover a wide range of aspects of EMI, encompassing policy debates, pedagogical practices, linguistic diversity, and broader socio-cultural implications across various global contexts. The geographical coverage of these publications spans Europe, East Asia (Hong Kong, China), the Netherlands, and Sweden, suggesting the widespread interest and impact of EMI across different regions and educational systems.

Table 5.

List of highly cited publications.

The top highly cited publications provide foundational insights applicable to a broad scope within the EMI field. Systematic reviews and conceptual frameworks, such as Macaro et al.’s [17] systematic reviews of EMI in higher education and Dafouz and Smit’s [25] dynamic conceptual frameworks for EMI in multilingual settings, provide comprehensive overviews of the field and extend the conceptual understanding on the subject. Specifically, Macaro et al.’s [17] comprehensive systematic review of EMI may serve as a key reference for researchers exploring EMI’s scholarly landscape. Regional and country-specific studies highlight the local implementations and challenges in Europe (e.g., Sweden, the Netherlands, Italy, and Austria) [22,34,63,64], East Asia (e.g., Korea, China, and Japan) [7,29,48] and the Gulf region [65]. In particular, these studies reveal the nuanced policy debates, practical realities, and varying degrees of success in these contexts. The broader implications of EMI within neoliberal policies are critically examined in Piller and Cho’s [4] study, emphasising how economic and political agendas influence language policies. Lei and Hu [66] argue that the medium of instruction does not have a statistically significant impact on English proficiency or the emotional aspects of learning and using English.

Additionally, highly cited studies have explored the perceptions, attitudes, and practices of teachers and students, highlighting the practical challenges and motivations involved. Factors influencing student success, including language proficiency, academic skills, and motivation, are analysed by Jiang et al. [21] and Rose et al. [67]. Disciplinary differences in the use of EMI in higher education are considered by Bolton and Kuteeva [68] and Kuteeva and Airey [34], reflecting on recent language policy developments. Collectively, these works contribute to a nuanced understanding of the opportunities and challenges associated with EMI in higher education, offering insights into policy analysis, practical implementation, and the experiences of key stakeholders. Finally, although not solely focusing on EMI, Mattoo et al. [69] discuss the labour market outcomes for educated immigrants in the US, providing a broader context for understanding the implications of English language proficiency.

In summary, the influential publications in EMI research encompass various topics, consistently highlighting the significance of comprehending the pedagogical and sociopolitical dimensions of EMI, along with its effects on students, teachers, and institutions globally.

Table 6 showcases the top productive journals on EMI out of 489 sources. We selected 23 journals for a detailed analysis to capture clusters with similar publication numbers, offering a comprehensive view of the dataset. Approximately 30.6% of relevant papers are published in these selected journals. Journals such as the Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development, System, the International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, Multilingual Education, and the Journal of English for Academic Purposes are the top five leading journals in terms of the number of EMI research publications. They have significantly higher numbers of articles compared to other journals on the list. These journals demonstrate interconnectedness and overlap, suggesting that researchers and practitioners in the field often draw from diverse areas of expertise and contribute to multiple journals within the EMI domain.

Table 6.

List of the most relevant journals.

Most of the journals in Table 6 belong to applied linguistics, with further representation from higher education-specific journals like Higher Education and Teaching in Higher Education, other education-focused publications such as International and Development Education and Education in the Asia-Pacific Region, and interdisciplinary journals like Frontiers in Psychology, demonstrating EMI’s connections with sociology, education, and psychology.

Overall, several highly cited publications come from journals that are also highly influential in terms of the number of documents published and citations as demonstrated by h-index data (e.g., Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development, Higher Education, and International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism). However, a few articles leading the list of highly cited publications (Table 5) are published in journals that are not included among the most productive journals, for example, Language Teaching and Language in Society (Table 6).

4.4. Social Structure of EMI in Higher Education

Analysing the collaborative network within a subject is vital for comprehending its social structure, as it helps identify networks of influential authors and countries. Such analysis also assists in finding authors who share common research interests and are connected through collaborative networks. Therefore, a series of co-authorship analyses by authors and countries was conducted to examine the collaborations between authors and countries within the dataset.

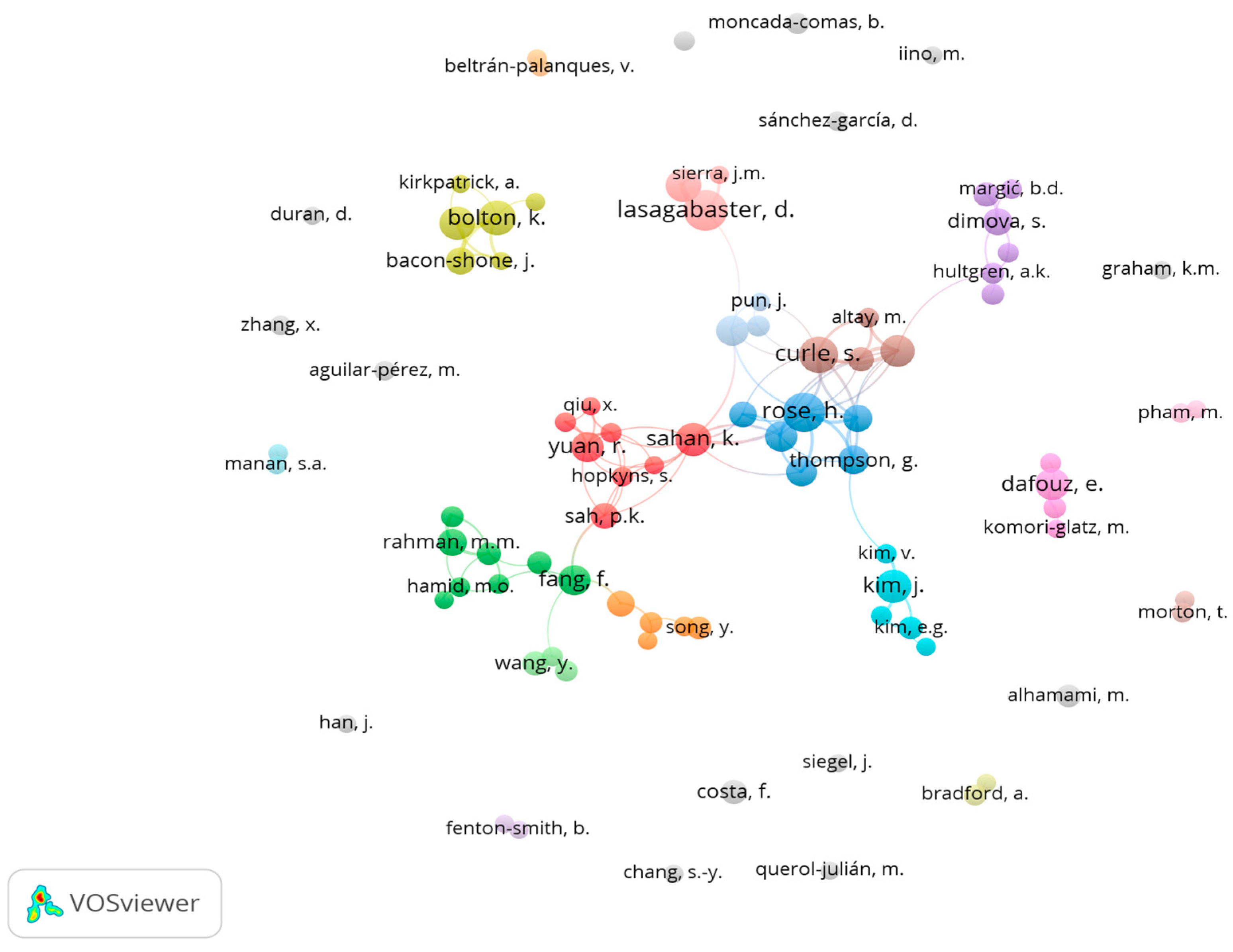

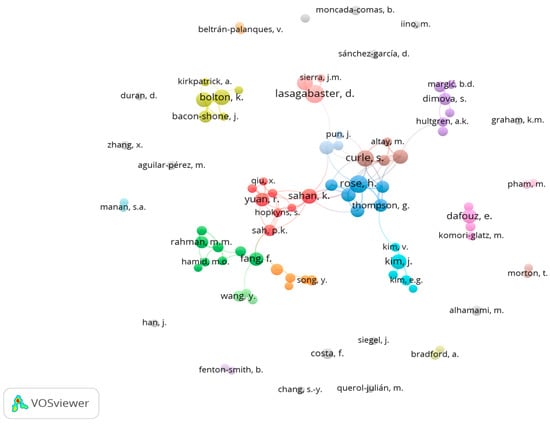

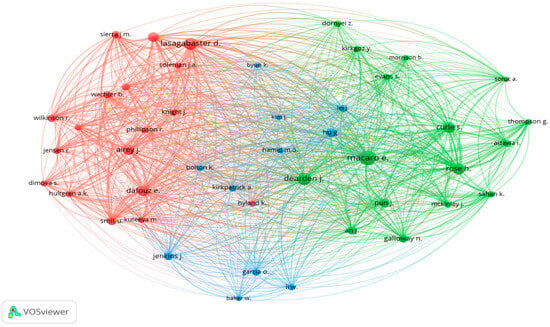

Figure 4 illustrates collaborative networks among authors who have published a minimum of five articles in the Scopus database. Eighty-seven authors met this threshold, with the two largest clusters comprising eight authors. Examination of these clusters reveals that organisational and regional proximity plays a significant role in collaboration.

Figure 4.

Collaborative research networks between authors.

Authors affiliated with or previously associated with the same institution tend to form networks. For instance, the collaborative network between Lasagabaster D. and Doiz A. represents the University of the Basque Country. Similarly, Hultgren A.K. and Dimova S. were once affiliated with the University of Copenhagen. This observation suggests that author networks are predominantly established within a specific country or affiliation.

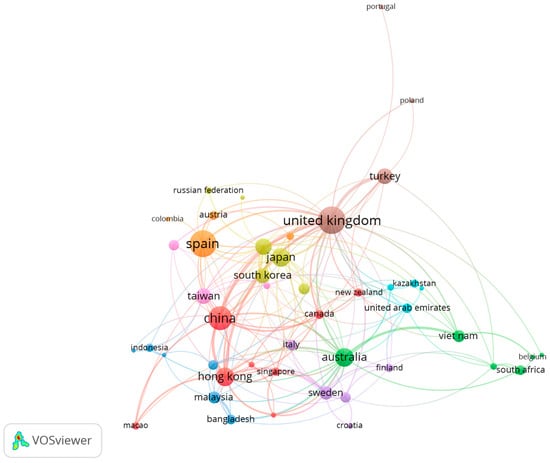

To explore the collaboration between territories (Figure 5), we selected countries with at least five publications. The analysis establishes that around 48 countries have been engaged in international collaborative research on EMI. Geographical proximity plays a key role in fostering close collaborations among countries within each network. For example, China shows strong connections with Macao, Hong Kong, and Singapore. European countries, such as Sweden, Finland, Croatia, and Italy, form another network. Conversely, there exist cross-country collaborations that transcend regional proximity. The UK, Turkey, Poland, and Portugal have engaged in joint research efforts on EMI.

Figure 5.

Collaborative research networks between countries.

Notably, a few countries predominantly lead the networks in EMI publications, including the UK, China, Spain, Australia, Japan, and Hong Kong. The UK leads with international collaborations spanning 32 countries and a total link strength of 126, followed by China and the US, each with 21 and 20 links and total link strengths of 80 and 41, respectively. Australia and Hong Kong follow closely with 17 collaborations and total link strengths of 63 and 78, respectively. While countries like Hong Kong, Spain, and China engage in substantial collaborative research, their connections are fewer, and they are mainly with key networking countries such as the US, UK, and China.

4.5. The Intellectual Structure of EMI Research in Higher Education

We conducted a co-citation analysis of authors to understand the intellectual structure within the field concerning authors [60]. More specifically, co-citation means that when another author cites two authors together, the strength of their co-citation increases with the number of authors citing them together. Authors with greater total link strengths are seen as more influential or central to the field compared to those with lesser link strengths [70]. In our study, this approach is employed to identify key contributors who have significantly influenced the scholarly domain and share similar research interests (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Co-citation analysis of authors (network visualisation). Minimum number of citations: 200.

According to the co-citation network, Ernesto Macaro leads the list of highly cited authors with 1360 citations and a total link strength of 30,519. Macaro is renowned for his extensive work in the field of applied linguistics, with a specific focus on second language learning and EMI. One of the prominent works produced by Macaro is a book on English Medium Instruction (not indexed in the Scopus database), in which he attempted to theorise and conceptualise knowledge on EMI. While reviewing research on both secondary and higher education in his book, Macaro raised critical questions on various aspects of EMI, such as implementation, cost-benefit, and future impact.

Other leading authors with the highest number of citations and greater total link strengths of their co-citations, such as Julie Dearden (964, 14,222), Samantha Curle (829, 14,819), and Heath Rose (813, 14,555), also represent UK universities and have explored EMI policies and practices globally, highlighting the challenges and implications for stakeholders. Also, David Lasagabaster (974, 15,934), Emma Dafouz (762, 12,904), and Aintzane Doiz (610, 10,496), representing Spanish universities, focus on bilingualism and multilingual education, providing valuable insights into the effectiveness of CLIL. Collectively, these scholars and others in the networks (Figure 6) highlight key trends in EMI research, including a focus on language policy, multilingual education, internationalisation of higher education, and the perspectives of students and teachers. Their work underscores the complexities and multifaceted nature of implementing EMI and CLIL, offering a comprehensive understanding that informs both policy and practice.

Co-citation analysis also revealed networks among scholars sharing research interests, leading to the identification of three key clusters. Notably, the green cluster, represented by E. Macaro, J. Dearden, H. Rose, S. Curle, and others, showcases common research foci among authors. Another cluster highlights co-citation patterns of scholars like D. Lasagabaster, E. Dafouz, and J. Airey, indicating shared research themes. Interestingly, the co-citation map illustrates how authors’ backgrounds align with their research interests, with the green cluster often linked to UK universities and the red cluster representing European affiliations.

A separate group, including A. Kirkpatrick, O. Garcia, J. Jenkins, M.O. Hamid, and others, forms the blue cluster, exploring topics beyond EMI and delving into the theoretical foundations of bilingual education. These authors bring expertise in language policy, sociolinguistics, and critical discourse analysis, enriching the realm of applied linguistics.

4.6. Conceptual Structure: Major Research Topics

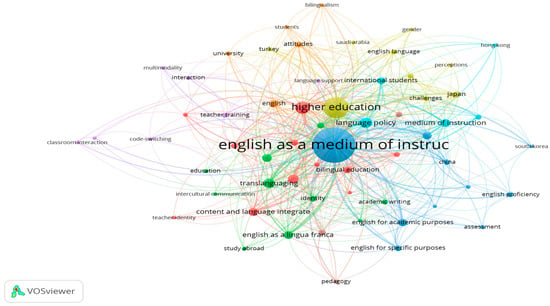

A co-occurrence analysis was performed for keywords appearing at least eight times in the dataset (n = 60) to identify the topical areas in the domain. The initial analysis retrieved a map with multiple variations in using EMI concepts, including abbreviations (e.g., EMI, EME, or CLIL) and differing use of terms (e.g., English as a medium of instruction, English medium instruction). Therefore, to keep the terminology consistent in the network map, we created a thesaurus file that consolidated abbreviations or varying usage of identical concepts for analysis. Figure 7 depicts the topical landscape of EMI research in higher education between 1974 and 2024. The analysis revealed eight clusters of interconnected keywords, with the node sizes reflecting the frequency of occurrence [71].

Figure 7.

Topical foci of EMI research in higher education. Co-occurrence analysis of keywords occurring eight or more times (n = 60).

The first cluster identified in the keyword co-occurrence map (Figure 7) delineates a significant research area (red cluster) encompassing the following keywords: academic achievement, bilingual education, classroom discourse, content and language integrated learning, English as a foreign language, English medium education, internationalisation, teacher education, teacher identity. This focus area indicates scholarly attention towards diverse forms of EMI within multilingual and multicultural contexts.

The second cluster delves into cross-cultural interactions and global knowledge exchange (green cluster). This section integrates essential terms like English as a lingua franca, intercultural communication, transnational higher education, study abroad, globalisation, and associated subjects.

The third cluster, denoted by the blue colour, focuses on research areas related to assessment, learning strategies, English for academic purposes, English for specific purposes, self-efficacy, and motivation. This cluster underscores scholarly endeavours to enhance students’ knowledge acquisition and application skills, especially in academic and specialised settings.

The fourth cluster in yellow colour is represented by keywords such as challenges, perceptions, English language proficiency, higher education, Japan, Saudi Arabia, and Turkey. These research areas, which are dedicated to exploring attitudes and challenges, are significant in enhancing students’ learning and enriching their educational experiences, particularly in Japan, Saudi Arabia, and Turkey.

The purple cluster, representing the fifth colour on the map, features keywords like classroom interaction, code-switching, conversation analysis, interaction, language support, multimodality, and teacher training. This cluster delves into classroom-specific issues, focusing on pedagogical practices and translanguaging.

The turquoise-coloured sixth cluster includes keywords like international students, language ideology, language policy, medium of instruction, and Hong Kong. This cluster revolves around research areas related to policy issues.

The orange-coloured seventh cluster grouped keywords such as attitudes, bilingualism, English, students, and university under one cluster. This area of research might examine the issues of bilingualism among key university stakeholders.

Last but not least, the brown cluster with three keywords—pedagogy, professional development, and Vietnam—demonstrates the interconnectedness of issues on EMI pedagogy with the research on professional development. The occurrence of Vietnam in this cluster can be attributed to the close link between pedagogical issues and professional development within EMI research in the country.

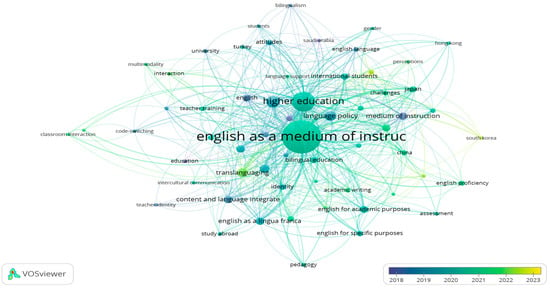

To identify the latest topical foci and researchers’ interests in HE, we retrieved a map of EMI research foci evolution (Figure 8). The time frame considered for analysis is 2018–2023. The dark green nodes represent the earlier foci, while light yellow nodes show more recent keywords. While most of the keywords in the map appear as dark green and green, demonstrating the continuing research interest of researchers, the areas such as academic achievement, translanguaging, self-efficacy, classroom interaction, multimodality, and South Korea are the most recent foci of scholarly audience in the field of EMI (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

Overlay visualisation of the evolution of EMI Research in higher education with keywords occurring eight or more times (n = 60).

5. Discussion and Conclusions

This study conducted a comprehensive bibliometric analysis of the EMI research using the Scopus database, examining 1522 publications to uncover global trends, growth trajectories, thematic and regional concentrations, and scholarly connections.

The analysis of the growth trajectory demonstrates an increasing trend in research production, particularly since 2018. The top five most productive, highly cited authors with prominent publications in the field include Lasagabaster D., Rose H., Curle S., Bolton K., and Botha W., while the leading countries for EMI research are China, Spain, the UK, Australia, and Hong Kong. Spain and Sweden stand out for their high productivity in EMI research among non-Anglophone European nations. Spain’s commitment to EMI investment contrasts with Sweden’s growth driven by institutional internationalisation [34]. In Asian countries like China [26], South Korea [29], Taiwan [72], and Japan [6], EMI research growth aligns with active governmental policies supporting EMI [7], though it is worth noting that socio-linguistic realities of these Asian countries, as well as others, vary significantly affecting the EMI dynamics in each context in its own way [11]. Interestingly, with the exception of Kazakhstan, post-Soviet countries did not feature prominently in the analysis of author performance, their affiliations, or national contributions to EMI research. Although Kazakhstan did not rank among the top countries in EMI research, Nazarbayev University emerged as the second most prevalent affiliation for publications in this field. The scholars’ interest in EMI may be attributed to the fact that Kazakhstan is the first in the post-Soviet context to encourage EMI via its national language policy [42].

The analysis of the field’s social structure revealed that author networks are primarily country-specific, with notable collaborative ties involving the UK, USA, Hong Kong, Spain, and China. This geographical emphasis in research partnerships corresponds to conclusions drawn from bibliometric research across various topics [73,74]. These established collaborations with specific countries lead to differences in terminologies and research focuses. Therefore, there is a need for increased collaborative research among nations to ensure consistent terminology usage while investigating variations in EMI contexts and focal points.

The analysis of the most productive journals showcased Language Teaching and Higher Education as hosting the highest number of highly cited publications. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development, System, and the International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism are among the most productive journals. While most productive journals predominantly belong to the field of applied linguistics, some also cover higher education and multidisciplinary perspectives.

The analysis of the conceptual structure of EMI in higher education reveals a complex and multifaceted landscape. The presence of diverse terminologies in the conceptual structure map and influential publications underscores the terminological inconsistency that poses challenges for scholars [5]. In brief, the highly cited publications in EMI research cover a wide range of topics, highlighting the complex interplay between pedagogical practices, policy analysis, and the sociopolitical context of EMI. These works collectively contribute to a nuanced understanding of EMI, emphasising the importance of contextual, regional, and stakeholder perspectives in shaping effective EMI policies and practices. The studies encompass terminological fluidity, pedagogical implications, institutional challenges, and socio-political impacts. Therefore, future research should continue exploring the nuanced dynamics of EMI to clarify terminologies, refine pedagogical methods, and establish robust institutional structures and socio-culturally sensitive policies.

The topic maps indicate a research emphasis in EMI settings on student support, translanguaging practices, and internationalisation, encompassing various concepts under the EMI umbrella. A noticeable shift towards multilingualism and translanguaging suggests a move away from English-only policies towards embracing EMI in multilingual environments, fostering inclusivity through translanguaging [20]. These areas are anticipated to gain more attention as scholars delve deeper into the nuances of translanguaging in EMI contexts. The topical foci map illustrates ongoing research in EMI covering topics like ELF, EAP, ESP, CLIL, and others, indicating a breadth of terminologies beyond the search string criteria. This terminological diversity may be attributed to geographical preferences [5], such as South Korea’s focus on ESP and EAP, while research in China predominantly centres on EMI.

The topic maps also identified gaps in research. First, while (post)colonialism features prominently in discussions of EMI in school contexts [5,52,55], the analysis of topical foci reveals its limited presence in EMI studies within higher education. Instead, the map indicates a substantial research interest revolving around internationalisation and globalisation, exploring various interconnected issues. Second, despite influential studies highlighting concerns about EMI implementation [7,17], these concerns are not prevalent in the topical map. Existing studies on EMI primarily concentrate on countries like Japan [7,33] and China [21,26,48], highlighting the urgent need for enhanced scholarly focus on EMI implementation across diverse contexts. Given the context-dependent nature of EMI implementation leading to diverse practices [2], tailored, context-specific approaches are essential to address educational challenges experienced on the ground [49,50]. Third, collaborative research involving diverse perspectives, especially from regions less dominant in EMI research, is crucial for a comprehensive understanding of global EMI practices and challenges. These collaborations aid in enhancing research capacity in regions where EMI practice and research are still in the early stages, offering unique local insights with broader implications and fostering global knowledge exchange. Moreover, fostering inclusive collaboration with local scholars from developmental contexts is crucial for enhancing the relevance and impact of research findings. This collaboration ensures that the research is effectively tailored to and informed by the specific needs and conditions of various regions. [49].

This study aimed to provide insights for educators, policymakers, and researchers on the current state and future directions of EMI research, fostering discussions on effective EMI implementation in multilingual settings. However, its scope was limited by utilising data solely from journal articles, books, and book chapters. Future research could expand by including data from theses, dissertations, and reports, which are not indexed in Scopus. While bibliometric analysis is valuable, it may not capture the contextual intricacies shaping research trends in the EMI field. Socio-political, economic, and cultural influences on research priorities and collaborations may not be fully captured through quantitative analyses. Moreover, network analyses (e.g., co-citation analysis) concentrate on highly cited or top producers, leaving recent publications and authors out of network clusters. Our study underscores the importance of delving deeper into the data beyond mere numbers.

Author Contributions

A.K. and N.D. jointly conceptualised and designed the study. A.K. carried out the analysis, and N.D. secured funding. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Nazarbayev University via Grant no. 021220CRP1122 awarded to Naureen Durrani and the Global Challenges Research Fund (GCRF) via the Arts and Humanities Research Council (grant number AH/T008075/1).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data linked to the research is presented within the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Walkinshaw, I.; Fenton-Smith, B.; Humphreys, P. EMI issues and challenges in Asia-Pacific higher education: An introduction. In English Medium Instruction in Higher Education in Asia-Pacific: From Policy to Pedagogy; Fenton-Smith, B., Humphreys, P., Walkinshaw, I., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, J.C.; Pun, J. A typology of English-medium instruction. RELC J. 2023, 54, 216–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shepard, C.; Rose, H. EMI pedagogical challenges in a changing Hong Kong higher education context. In English-Medium Instruction Pedagogies in Multilingual Universities in Asia; Fang, F., Sah, P.K., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2023; pp. 123–137. [Google Scholar]

- Piller, I.; Cho, J. Neoliberalism as language policy. Lang. Soc. 2013, 42, 23–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macaro, E. English Medium Instruction; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Bradford, A. Toward a typology of implementation challenges facing English-medium instruction in higher education: Evidence from Japan. J. Stud. Int. Educ. 2016, 20, 339–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, H.; McKinley, J. Japan’s English-medium instruction initiatives and the globalisation of higher education. High. Educ. 2018, 75, 111–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sah, P.K. English medium instruction in South Asia’s multilingual schools: Unpacking the dynamics of ideological orientations, policy/practices, and democratic questions. Int. J. Biling. Educ. Biling. 2022, 25, 742–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowles, H.; Murphy, A.C. EMI and the internationalization of universities: An overview. In English-Medium Instruction and the Internationalization of Universities; Bowles, H., Murphy, A.C., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 1–26. [Google Scholar]

- Manan, S.A.; Hajar, A. Understanding English medium instruction (EMI) policy from the perspectives of STEM content teachers in Kazakhstan. TESOL J. 2024, e847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolton, K.; Bacon-Shone, J.; Botha, W. EMI (English-medium instruction) across the Asian region. World Engl. 2023, 42, 392–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gough, D.; Elbourne, D. Systematic research synthesis to inform policy, practice and democratic debate. Soc. Policy Soc. 2002, 1, 225–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donthu, N.; Kumar, S.; Mukherjee, D.; Pandey, N.; Lim, W.M. How to conduct a bibliometric analysis: An overview and guidelines. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 133, 285–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jablonkai, R.R.; Hou, J. English medium of instruction in Chinese higher education: A systematic mapping review of empirical research. Appl. Linguist. Rev. 2023, 14, 1483–1512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang, T.K.A.; Bonar, G.; Yao, J. Professional learning for educators teaching in English-medium-instruction in higher education: A systematic review. Teach. High. Educ. 2023, 28, 840–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pun, J.K.; Fu, X.; Cheung, K.K.C. Language challenges and coping strategies in English Medium Instruction (EMI) science classrooms: A critical review of literature. Stud. Sci. Educ. 2024, 60, 121–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macaro, E.; Curle, S.; Pun, J.; An, J.; Dearden, J. A systematic review of English medium instruction in higher education. Lang. Teach. 2018, 51, 36–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Öztürk, O.; Kocaman, R.; Kanbach, D.K. How to design bibliometric research: An overview and a framework proposal. Rev. Manag. Sci. 2024, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.F.; Tsai, H.L. Research trends in English as a medium of instruction: A bibliometric analysis. J. Multiling. Multicult. Dev. 2024, 45, 1792–1811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, D.; Wang, P. A bibliometric analysis of research trends in multilingualism in English medium instruction: Towards translanguaging turn. Int. J. Multiling. 2024, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, L.; Zhang, L.J.; May, S. Implementing English-medium instruction (EMI) in China: Teachers’ practices and perceptions, and students’ learning motivation and needs. Int. J. Biling. Educ. Biling. 2016, 22, 107–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, F.; Coleman, J.A. A survey of English-medium instruction in Italian higher education. Int. J. Biling. Educ. Biling. 2013, 16, 3–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taguchi, N. English-medium education in the global society: Introduction to the special issue. Int. Rev. Appl. Linguist. Lang. Teach. 2014, 52, 89–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, G.; McKinley, J. Integration of content and language learning. In The TESOL Encyclopedia of English Language Teaching; Liontas, J.I., DelliCarpini, T.M., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2018; pp. 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dafouz, E.; Smit, U. Towards a dynamic conceptual framework for English-medium education in multilingual university settings. Appl. Linguist. 2016, 37, 397–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, G.; Li, L.; Lei, J. English-medium instruction at a Chinese University: Rhetoric and reality. Lang. Policy 2014, 13, 21–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimauchi, S. English-medium instruction in the internationalisation of higher education in Japan: Rationales and issues. Educ. Stud. Jpn. 2018, 12, 77–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manan, S.A.; Channa, L.A.; Haidar, S. Celebratory or guilty multilingualism? English medium instruction challenges, pedagogical choices, and teacher agency in Pakistan. Teach. High. Educ. 2022, 27, 530–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byun, K.; Chu, H.; Kim, M.; Park, I.; Kim, S.; Jung, J. English-medium teaching in Korean higher education: Policy debates and reality. High. Educ. 2011, 62, 431–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahan, K.; Rose, H.; Macaro, E. Models of EMI pedagogies: At the interface of language use and interaction. System 2021, 101, 102616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macaro, E.; Akincioglu, M.; Han, S. English medium instruction in higher education: Teacher perspectives on professional development and certification. Int. J. Appl. Linguist. 2020, 30, 144–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKinley, J.; Rose, H. English language teaching and English-medium instruction: Putting research into practice. J. EMI 2022, 1, 85–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradford, A. It’s not all about English! The problem of language foregrounding in English-medium programmes in Japan. J. Multiling. Multicult. Dev. 2019, 40, 707–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuteeva, M.; Airey, J. Disciplinary differences in the use of English in higher education: Reflections on recent language policy developments. High. Educ. 2014, 67, 533–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Airey, J. I don’t teach language: The linguistic attitudes of physics lecturers in Sweden. AILA Rev. 2012, 25, 64–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dearden, J.; Macaro, E. Higher education teachers’ attitudes towards English medium instruction: A three-country comparison. Stud. Second Lang. Learn. Teach. 2016, 6, 455–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toh, G. English for content instruction in a Japanese higher education setting: Examining challenges, contradictions and anomalies. Lang. Educ. 2014, 28, 299–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hillman, S. Navigating identity and belonging as international branch campus students: The role of linguistic shame. In Linguistic Identities in the Arab States of the Gulf: Waves of Change; Hopkyns, S., Zoghbor, W., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2022; pp. 215–230. [Google Scholar]

- Goodman, B.; Kambatyrova, A.; Aitzhanova, K.; Kerimkulova, S.; Chsherbakov, A. Institutional supports for language development through English-medium instruction: A factor analysis. TESOL Q. 2022, 56, 713–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopkyns, S.; Hillman, S. Translanguaging in GCC English-Medium Higher Education: A Scoping Review. In Multilingual and Translingual Practices in English-Medium Instruction: Perspectives from Global Higher Education Contexts; Yuksel, D., Altay, M., Curle, S., Eds.; Bloomsbury Publishing: London, UK, 2024; pp. 11–31. [Google Scholar]

- De Costa, P.I.; Green-Eneix, C.; Li, W. Problematising language policy and practice in EMI and transnational higher education: Challenges and possibilities. Aust. Rev. Appl. Linguist. 2021, 44, 115–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tajik, M.A.; Abdul Manan, S.; Arvatu, A.C.; Shegebayev, M. Growing pains: Graduate students grappling with English medium instruction in Kazakhstan. Asian Eng. 2022, 26, 249–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hultgren, A.K.; Jensen, C.; Dimova, S. English-medium instruction in European higher education: From the north to the south. In English-Medium Instruction in European Higher Education; Dimova, S., Hultgren, A.K., Jensen, C., Eds.; De Gruyter Mouton: Boston, MA, USA, 2015; Volume 3, pp. 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coleman, J.A. English-medium teaching in European higher education. Lang. Teach. 2006, 39, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aizawa, I.; Rose, H. An analysis of Japan’s English as medium of instruction initiatives within higher education: The gap between meso-level policy and micro-level practice. High. Educ. 2019, 77, 1125–1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dearden, J. English as a Medium of Instruction—A Growing Global Phenomenon [Online] British Council. 2014. Available online: https://www.britishcouncil.org.br/sites/default/files/emi_a_growing_global_phenomenon.pdf (accessed on 20 June 2024).

- Karabassova, L. Understanding education reform in Kazakhstan: Why is it stalled? In Education in Central Asia: A Kaleidoscope of Challenges and Opportunities; Egea, D., Ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020; pp. 37–51. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, G.; Lei, J. English-medium instruction in Chinese higher education: A case study. High. Educ. 2014, 67, 551–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolton, K.; Botha, W.; Lin, B. English-medium instruction in higher education worldwide. In The Routledge Handbook of English-Medium Instruction in Higher Education; Bolton, K., Botha, W., Lin, B., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2024; pp. 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Hamid, M.O.; Nguyen, H.T.M.; Baldauf, R.B. Medium of instruction in Asia: Context, processes and outcomes. In Language Planning for Medium of Instruction in Asia; Hamid, M.O., Nguyen, H.T.M., Baldauf, R.B., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2015; pp. 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Durrani, N.; Nawani, D. Knowledge and curriculum landscapes in South Asia. In Handbook of Education Systems in South Asia. Global Education Systems; Sarangapani, P.M., Pappu, R., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2021; pp. 1589–1619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milligan, L.O.; Tikly, L. English as a medium of instruction in postcolonial contexts: Moving the debate forward. Comp. Educ. 2016, 52, 277–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tikly, L.P. Language-in-education policy in low-income, postcolonial contexts: Towards a social justice approach. Comp. Educ. 2016, 52, 408–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishioka, S.; Durrani, N. Language and cultural reproduction in Malawi: Unpacking the relationship between linguistic capital and learning outcomes. Int. J. Educ. Res. 2019, 93, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manan, S.A.; Tajik, M.A.; Hajar, A.; Amin, M. From colonial celebration to postcolonial performativity:‘guilty multilingualism’ and ‘performative agency’ in the English Medium Instruction (EMI) context. Crit. Inq. Lang. Stud. 2023, 21, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabriëls, R.; Wilkinson, R. Introduction: The tension between monolingualism and multilingualism. In Englishization of Higher Education in Europe; Wilkinson, R., Gabriëls, R., Eds.; Amsterdam University Press: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2021; pp. 11–36. [Google Scholar]

- Kirkpatrick, A. English as an Asian lingua franca and the multilingual model of ELT. Lang. Teach. 2011, 44, 212–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujita-Round, S.; Maher, J.C. Language policy and education in Japan. In Language Policy and Political Issues in Education; McCarty, T.L., May, S., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2017; pp. 491–505. [Google Scholar]

- AlRyalat, S.A.S.; Malkawi, L.W.; Momani, S.M. Comparing bibliometric analysis using PubMed, Scopus, and Web of Science databases. J. Vis. Exp. 2019, 152, e58494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cobo, M.J.; López-Herrera, A.G.; Herrera-Viedma, E.; Herrera, F. Science mapping software tools: Review, analysis, and cooperative study among tools. J. Am. Soc. Inf. Sci. Technol. 2011, 62, 1382–1402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez, F.; Baker, D.P. Science production in the United States: An unexpected synergy between mass higher education and the super research university. In The Century of Science: The Global Triumph of the Research University; Powell, J.J.W., Baker, D.P., Fernandez, F., Eds.; Emerald Publishing Limited: Leeds, UK, 2017; pp. 85–111. [Google Scholar]

- Nel, C.; Ssentanda, M.E. EMI in Sub-Saharan Africa. In The Practice of English as a Medium of Instruction (EMI) around the World; Griffiths, C., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 13–31. [Google Scholar]

- Tatzl, D. English-medium masters’ programmes at an Austrian university of applied sciences: Attitudes, experiences and challenges. J. Eng. Acad. Purp. 2011, 10, 252–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkinson, R. English-medium instruction at a Dutch university: Challenges and pitfalls. In English-Medium Instruction at Universities: Global Challenges; Doiz, A., Lasagabaster, D., Sierra, J.M., Eds.; Multilingual Matter: Bristol, UK, 2013; pp. 3–24. ISBN 9781847698162-005. [Google Scholar]

- Belhiah, H.; Elhami, M. English as a medium of instruction in the Gulf: When students and teachers speak. Lang. Policy 2015, 14, 3–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, J.; Hu, G. Is English-medium instruction effective in improving Chinese undergraduate students’ English competence? Int. Rev. Appl. Linguist. Lang. Teach. 2014, 52, 99–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, H.; Curle, S.; Aizawa, I.; Thompson, G. What drives success in English medium taught courses? The interplay between language proficiency, academic skills, and motivation. Stud. High. Educ. 2020, 45, 2149–2161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolton, K.; Kuteeva, M. English as an academic language at a Swedish university: Parallel language use and the ‘threat’ of English. J. Multiling. Multicult. Dev. 2012, 33, 429–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattoo, A.; Neagu, I.C.; Özden, Ç. Brain waste? Educated immigrants in the US labor market. J. Dev. Econ. 2008, 87, 255–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajar, A.; Karakus, M. A bibliometric analysis of shadow education in Asia: Private supplementary tutoring and its implications. Int. J. Educ. Dev. 2024, 108, 103075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bukar, U.A.; Sayeed, M.S.; Razak, S.F.A.; Yogarayan, S.; Amodu, O.A.; Mahmood, R.A.R. A method for analysing text using VOSviewer. MethodsX 2023, 11, 102339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeh, C.C. Instructors’ perspectives on English-medium instruction in Taiwanese universities. Curric. Instr. Q. 2012, 16, 209–232. [Google Scholar]

- Durrani, N.; Ozawa, V. Education in Emergencies: Mapping the Global Education Research Landscape in the Context of the COVID-19 Crisis. SAGE Open 2024, 14, 21582440241233402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kataeva, Z.; Durrani, N.; Izekenova, Z.; Rakhimzhanova, A. Evolution of gender research in the social sciences in post-Soviet countries: A bibliometric analysis. Scientometrics 2023, 128, 1639–1666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).