Abstract

Based on social interdependence and social constructivism theories, the authors of this study examined the effects of a cooperative learning (CL) pedagogical model on the engagement and outcomes of undergraduate students in an Ethiopian university’s classrooms. We did this by using a quasi-experimental post-test control group design. The study participants included undergraduate students enrolled in the courses “Risk Management and Insurance” (n = 99) and “Foundation Engineering I” (n = 94). The control groups received regular lecture-based teaching, while the experimental group received CL instruction over two weeks in six to eight sessions. The results from the Management sample, which demonstrated that the CL intervention group reported significantly higher learning outcomes and more engagement than the control groups, are sufficient evidence for the study to validate the hypothesis. The effect sizes were moderate and ranged from 0.52 to 0.78 Cohen’s d. In the Engineering course, the results demonstrate the smallest difference between the mean scores reported by the CL group and those of the regular lecture group, with the CL group showing slightly higher student engagement and outcomes across the three categories assessed. The Engineering sample’s results, however, did not show any significant differences between the CL and control groups. This study provides evidence that course reform utilizing a CL pedagogical design could improve student engagement and learning outcomes as compared to the regular lecture-based method. By incorporating CL pedagogies, higher educators and institutions can create more engaging and effective learning environments for students.

1. Introduction

1.1. Background

In the context of higher education (HE), learning outcomes, usually referred to as “educational outcomes”, relate to the knowledge, skills, and capacities that a student demonstrates after successfully completing a learning experience or series of learning activities [1]. Thus, learning outcomes are typically defined in terms of the expected student performances and acquired competencies. The discussion on the quality of undergraduate student learning and development has recently centered on learning outcomes in the global HE community [2].

Student engagement has been used to describe a variety of student actions and attitudes that are considered essential for a high-quality undergraduate learning experience [3]. It is regarded as a general indicator of high-quality teaching and learning, as shown by “how involved or interested students appear to be in their learning and how connected they are to their classes, their institutions, and each other [4] (p. 38). According to research, the concept of engagement is presumably adaptive, perceptive of context, and accepting of environmental changes [5]. The level of student participation in educational activities has increased throughout time [6], almost to the point where it now practically encompasses crucial elements of effective teaching and learning [7].

Students’ engagement in instructional activities is one of the most crucial factors in their success in HE institutions [8]. Student engagement is central for their performance as well as their social and cognitive development [9]. The elements that affect students’ engagement, however, are still largely unexplored [10]. The lack of engagement has largely been attributed to issues in students’ individual characteristics and to aspects of their institutions, such as fragmented curricula, poor instruction, and low expectations for student learning [11,12]. Also, increasing student engagement is still a challenge for HE teachers [13].

The arrangement of the learning environment in the classroom was found to be highly related to student engagement and learning outcomes [14]. Undergraduate students gain more knowledge when they focus on and make an effort toward a variety of educationally beneficial activities [15,16]. One interactive pedagogy that can assist university instructors in improving the quality and interest of their classes is cooperative learning (CL) [17,18]. To facilitate these changes, it provides teachers with a number of tools and techniques [19,20]. Numerous studies support the use of CL pedagogies to improve the intellectual, emotional, and social development of HE students [21,22,23]. We anticipated that a CL approach to instruction would provide better outcomes and more student engagement than a lecture-based method, which is in line with the social interdependence theory and empirical findings of earlier studies [23,24,25].

Regular lectures typically involve a teacher-centered approach where the teacher imparts knowledge to the students through lectures, readings, and demonstrations. The focus is often on the transmission of information from the teacher to the students, with little interaction among the students themselves [26]. On the other hand, CL instruction emphasizes active participation, cooperation, and interaction among students [26,27]. In CL, students work together in small groups to achieve common learning goals. This approach encourages peer support, discussion, and problem solving, facilitating deeper understanding and engagement with the material learned [28]. The key distinction lies in the level of student involvement and interaction. While a regular lecture relies heavily on the teacher as the primary source of knowledge and authority, CL instruction empowers students to take an active role in their own learning process and learn from one another through cooperation and teamwork [25].

Despite its importance, not all university teachers give quality teaching the attention it deserves, are aware of what it entails, have the capacity to ensure it occurs in their lectures, or are even willing to do so. Thus, opportunities for professional development (PD) for university teachers are highly necessary. According to a study, university teachers teaching conceptions shifted from being more teacher centered to being more student centered as a result of their participation in PD programs [29]. The self-efficacy, self-concept, and subjective knowledge of teachers about teaching and learning were also significantly changed by a PD project at a German university [30]. Any PD initiatives in universities should therefore place a high premium on methods to reduce these obstacles and thereby enhance the caliber of teaching behaviors and actions.

The majority of HE classes in sub-Saharan Africa consist mostly of lectures, which are of poor quality [31,32]. In response to this, over the past 20 years or more, there has been an increase in interest in pedagogical reform in the region [33,34,35]. However, a significant issue has come to light as a result of numerous intervention studies and attempts, namely the inadequate management capacities for the proposed intervention [36,37,38,39]. Furthermore, less is known about the pedagogical practices and initiatives that affect undergraduate students’ engagement and learning outcomes [40], particularly in Ethiopian HE as well as in other sub-Saharan African nations [41,42]. The authors developed and implemented a CL pedagogical model to address these challenges and enhance the skills of HE instructors and the quality of instruction given to undergraduate students at a university in Ethiopia. The purpose of this study is to find out whether students who finish courses employing CL pedagogies show better levels of engagement than their control counterparts, as well as whether the same students also display higher levels of learning and development outcomes. More specifically, this study answers the following research questions:

1.2. Research Questions

- Does student participation in CL classrooms lead to greater engagement in active and cooperative learning for undergraduate Management and Engineering students?

- Does student participation in CL classrooms lead to higher degrees of engagement in student–teacher relationships for undergraduate Management and Engineering students?

- Does student participation in CL classrooms lead to higher outcomes in personal and social development for undergraduate Management and Engineering students?

This study focuses on student engagement and learning outcomes as the centerpiece of the CL pedagogical intervention, primarily because of several gaps in undergraduate education, specifically in the developing country context. For example, passive learning is most frequently apparent through regular lecture-based teaching [43], in which students merely receive information rather than actively participate in the learning process [44]. Also, in large lecture courses, students may have limited opportunities for social interaction with peers, leading to feelings of isolation and disengagement [45]. Additionally, many undergraduate students struggle to see the relevance of course material to real-world contexts [46,47]. By addressing these gaps through the incorporation of CL pedagogies, educators can create more engaging, inclusive, and effective learning environments that support the diverse needs and learning outcomes of their students [48,49]. In this study, we chose CL pedagogies to encourage active engagement and promote interaction and support among students [50]. We anticipated that CL pedagogies allow for scaffolding, enabling students to learn from each other and receive peer support tailored to their individual needs, apply theoretical concepts to practical situations, and enhance their understanding and interest in courses [19,51].

2. Literature Review

2.1. Theoretical Foundations and Empirical Evidence of CLs

In the CL context, small groups of students actively work together to achieve a common goal, significantly maximizing their own and each other’s learning [52,53]. This small-group learning contrasts with regular competitive or individualistic learning environments [54]. Empirical evidence strongly supports CL methods as effective pedagogies for engaging students in undergraduate education [23]. These methods greatly increase academic performance and promote deeper understanding [55], as well as assist students in developing their capacity for critical thinking and interpersonal interaction [56], making them valuable tools in the modern educational landscape [28]. Social interdependence and social constructivist theories serve as the theoretical foundations for CL, supporting the social and interactive components of learning.

Kurt Lewin primarily developed the social interdependence theory [57], and later, Morton Deutsch and David Johnson expanded and refined it [24,58,59]. This theory posits that how interdependence is structured affects how people interact, which, in turn, affects the outcomes [24]. Positive interdependence in CL, where students perceive that they can succeed only if their group members also succeed, promotes cooperation, support, and mutual benefit, leading to higher engagement and better learning outcomes.

In HE, social interdependence theory can effectively guide the application of CL strategies, where students engage in complex problem solving and critical thinking [53,60]. For instance, instructors can create group exercises or assignments that require students to work together in specific roles. This design ensures that each member contributes to the group’s success, promoting positive interdependence.

Social constructivism, another theory rooted in the ideas of Vygotsky and Piaget, provides a robust foundation for CL in HE [61,62]. The theory posits that knowledge is constructed through social interactions and collaboration rather than being passively received. Piaget emphasizes active learning and the importance of students who construct their understanding through experience and reflection [63]. CL facilitates this by encouraging students to discuss, argue, and test their ideas with peers. Additionally, Vygotsky highlights the significance of social interaction and the Zone of Proximal Development (ZPD). CL leverages this by combining students of varying abilities, allowing more capable peers to help others progress beyond what they could achieve alone.

Gokhale [61] conducted a study in which undergraduate students were assigned to either CL groups or individual learning settings to solve complex problems. The results revealed that students in cooperative groups outperformed those in individual settings on problem-solving tasks, supporting Vygotsky’s ZPD concept [61]. The study suggested that more knowledgeable peers in the groups provided scaffolding, enabling their less knowledgeable peers to achieve a deeper level of understanding.

2.2. Conceptualizing and Measuring Student Engagement and Outcomes

Student engagement is a multidimensional concept that encompasses students’ involvement in their learning, their connections to their classes, institutions, and each other [4] (p. 38). Psychologist Csikszentmihalyi [64] developed the concept of flow, describing a state of optimal experience where individuals are fully immersed and focused on an activity, feeling energized, motivated, and deeply involved. The student, the teacher, and the content are the primary elements of the classroom environment that interact to affect engagement [45]. Implementing student-centered pedagogies such as CL usually increases engagement [21].

Measuring student engagement in a university classroom context involves assessing the level of involvement, interaction, and interest that students demonstrate during their learning experiences [23,64]. There are a few common methods and strategies for measuring student engagement; some are quantitative [65,66], while others are qualitative [67]. A full discussion of the different strategies for measuring student engagement is beyond the scope of this study. However, we emphasized the use of questionnaires. Questionnaires are one of the common methods for gathering feedback from students about their perceptions of engagement. A questionnaire includes asking questions about their level of interest in the course material, the effectiveness of the teaching methods, and their overall satisfaction with the learning experience.

Fredricks and colleagues [66,68,69,70], along with George Kuh [71,72], have greatly increased our understanding of student engagement by defining and measuring it using a self-reported questionnaire, and researchers frequently cite their work in the international literature. Fredricks et al. emphasize three dimensions of student engagement: cognitive, emotional, and behavioral [66]. In contrast, Kuh’s approach includes five or more dimensions [73], including institutional practices and environmental factors, that support student engagement [5]. He emphasizes the importance of collaborative learning, student-faculty interaction, and a supportive campus environment. These two approaches greatly provide valuable insights into student engagement, but researchers must choose based on research questions and practical needs. In this study, the authors chose Kuh’s conceptualization and instrument because it aligns better with our research, which emphasizes high-impact activities and learning outcomes.

Measuring undergraduate student outcomes involves utilizing direct measures such as standardized tests, capstone projects, portfolios, course-embedded assessments, and performance assessments [74]. Indirect measures, on the other hand, include conducting surveys, focus groups, interviews, and alumni surveys; analyzing retention and graduation rates, institutional data, and learning analytics; and examining post-graduation outcomes [75,76]. These measures assist in comprehending students’ perceptions of their learning experiences, satisfaction levels, and perceived achievements, as well as evaluating their satisfaction with their education [77]. Using all these outcome measures in a single study is practically impossible due to logistical and other technical challenges.

Self-reported survey questionnaires are relevant tools for measuring the impact of CL in HE classrooms. They allow researchers to directly access student perceptions and experiences, enabling a more refined analysis of the effects of educational interventions. Additionally, these questionnaires can measure various outcomes of CL, including personal gains, social development, and emotional responses, offering a comprehensive understanding of the learning process. Gonyea and Miller [78] conducted a study exploring the validity of self-reported data in HE studies. They support the idea that well-constructed self-reported surveys can serve as reliable measures of students’ perceived learning and affective outcomes.

Self-reported survey questionnaires are useful instruments for gauging the effect of CL in HE classes. By giving researchers direct access to student perspectives and experiences, they make it possible to conduct a deeper analysis of the results of educational interventions [79]. These surveys can also assess a range of CL outcomes, including social development, emotional reactions, and personal gains, providing a comprehensive grasp of the learning process.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Study Design

In this study, the authors used a quasi-experimental post-test control group design [79], collecting post-test data from the participating undergraduate students who took similar courses regarding their perceptions about their engagement and the personal and social learning outcomes achieved. This design is a type of experimental research design used to evaluate the effect of an intervention (CL pedagogical methods) by comparing the outcomes of two groups: one that receives the intervention (experimental group) and one that does not (control group). This design is an established approach to evaluate the effectiveness of educational interventions in the HE setting [80,81], suggesting that this kind of design can yield valid and reliable outcomes.

This study is a continuation of a previous effort made in the College of Natural Sciences and College of Social Sciences and Humanities of the same University. While the original project was mixed-methods research, comprising a phenomenological case study to measure implementation and a quantitative post-test control group design to measure effectiveness. These two components were separated during the preparation of manuscripts for publications. The phenomenological case study piece was published in the Journal of Education Sciences [82].

3.2. Study Participants’ Sampling Procedure

1. The study participants included 99 undergraduate students enrolled in the course “Risk Management and Insurance” and 94 students enrolled in the course “Foundation Engineering I” at Jimma University during the study period.

2. The groups were determined as follows:

- Intervention group: students who experienced CL in their course;

- Control group: students who attended regular lecture-based instruction.

3. The student participants in each course were divided into intervention and control groups.

In the “Risk Management and Insurance” course:

- The intervention group consisted of students who experienced CL.

- The control group consisted of students who experienced regular lecture-based instruction.

In the “Foundation Engineering I” course:

- The intervention group consisted of students who experienced CL.

- The control group consisted of students who experienced regular lecture-based instruction.

4. Sampling procedure: random group assignment within each course:

Because random assignments were not feasible, the authors assigned student groups instead of individual students. This was carried out using intact groups (such as the two groups labeled as Group 1 and Group 2) as the intervention and control groups. Therefore, one section of the “Risk Management and Insurance” course served as the intervention group, while another section functioned as the control group. Similarly, one section of the “Foundation Engineering I” course was assigned as the intervention group, with another section as the control group. However, we used a form of the quasi-randomization technique, like matching, in our randomization process. This ensured that participants in the CL intervention group were comparable to participants in the control group based on relevant characteristics (such as age and gender) to maintain group similarity.

3.3. Study Contexts

This study employed criterion-based sampling to select course teachers for two groups of undergraduate students, focusing on Civil Engineering and Management courses. The courses included (1) Civil Engineering: “Foundation Engineering I” (Course Code: CENG 3131) and (2) Management: “Risk Management and Insurance” (Course Code: Mgmt 3193). The study randomly selected teachers from colleges, including both male and female instructors, using a criterion-based sampling method based on their interests and identical courses offered to two undergraduate groups. The authors included students from each department, including one in Civil Engineering and one in Management, and carefully selected male and female teachers.

3.4. A Summary of the Five Variants of CL Intervention and Their Respective Goals

The study involved two training workshops, classroom intervention, and collaborative planning. The CL pedagogies comprise five variants, including think–pair–share, think–share–pair–create, paired heads together, pyramiding, and group investigation, to engage students and enhance understanding.

Think–pair–share starts with individuals thinking about a prompt or question on their own (think), then discussing their ideas with a partner (pair), and lastly sharing them with the entire group (share). This type of CL encourages active participation and allows students to consolidate their understanding through discussion.

Think–share–pair–create includes a creative component, much like think–pair–share. After considering an idea or issue for a while, the students discuss it with a partner before working together to produce a project, presentation, or practical result. It stimulates creativity and fosters a better understanding.

Paired heads together requires students to work in pairs to solve problems or complete tasks. Each pair consists of a “leader” and a “listener”. The leader articulates his/her thinking process aloud, while the listener provides feedback and helps clarify ideas. This facilitates peer teaching and active engagement.

Pyramiding involves structuring group discussions in a hierarchical manner. Students start by discussing ideas in pairs or small groups and then join larger groups to share and refine their ideas further. Finally, the entire class comes together for a comprehensive discussion or presentation. This type of CL allows for the gradual development of ideas and encourages participation at different levels.

Group investigation involves assigning small groups of students to explore a chosen topic in depth. Each group investigates a specific aspect of the topic and then shares its findings with the class. Group investigation promotes collaboration, critical thinking, and research skills while allowing students to take ownership of their learning.

The CL pedagogical intervention lasted two weeks, with 3–4 lessons per week. Students’ GPAs and genders were considered for small-group participation. Individual writing and thinking exercises were added to CL activities to promote self-directed learning, stimulating interest and facilitating pair discussions.

At the start of implementing the intervention, the authors provided the teacher participants with books and articles on CL, which helped them manage their classrooms better and provide clear ideas for successful application. Teachers used CL pedagogies in the experimental groups and a regular lecture in the comparison groups, covering the same material and distributing instruction time equally between the two groups.

3.5. Description and Operationalization of Variables

The first outcome of interest is the students’ engagement, which was measured u their post-test scores. The second outcome included student learning outcomes, as measured by the students’ perceived personal and social development outcomes. The independent variable in the analysis included the pedagogical approach used in classroom instruction, either regular, lecture-based instruction or CL pedagogical instruction (coded as a binary variable).

3.6. Tools for Data Collection

To collect data from students, the authors used a self-administered questionnaire. Using a customized instrument in an Ethiopian HE setting [83], the study measured improvements in students’ learning in social and personal development, active and cooperative learning, and student–teacher relationships. Social constructivism and engagement theories explain the importance of these metrics in determining the effectiveness of CL pedagogies.

Scholars advocating for social constructivism, such as Piaget [63] and Vygotsky [84], along with the engagement theorists Kearsley and Shneiderman [85], contend that learning is an active and constructive process in which students build new knowledge upon pre-existing knowledge. In a CL environment, students engage with peers to co-construct knowledge. Moreover, Vygotsky emphasizes the role of social interaction in learning, specifically through the concept of the Zone of Proximal Development (ZPD), which suggests that learners achieve higher levels of understanding through cooperative activities [86]. This underscores the idea that “psychological development and instruction are socially embedded” [87] (p. 349). In tandem, these foundational theories support the idea that measuring student engagement and learning outcomes is essential in CL intervention studies. Engagement is a critical indicator of how actively students participate in and contribute to cooperative activities, while outcomes reveal the effectiveness of these activities in achieving learning and development. Together, these measures provide a comprehensive picture of the impact of CL interventions on student participation and development.

The student engagement and outcome items included in this study underwent rigorous validation processes in a previous study using CFA and structural equation modeling analysis [88,89,90], ensuring they accurately captured the intended constructs. The participants of this study were asked to consider their experiences in the classes, their sense of satisfaction while reading statements, and rate how true each statement was for them using various items. A scale from 1 (never) to 4 (very often) was used for the student engagement questions. One of the student engagement questions asked, “Based on your experience in this course during the last two weeks, how frequently have you discussed ideas about the subject with the other students?” A scale from 1 (very little) to 4 (very much) was used for the student outcome questions. One of the outcome questions asked, “To what extent has your learning experience in this course during the last two weeks contributed to working effectively with others?”.

3.7. Study Procedures

In this study, the control group received regular lecture-based instruction, while the intervention group received CL instruction. A post-intervention questionnaire was completed by the students both in the intervention and control groups. Following authorization to enter the study location and after receiving informed consent from each participant, the authors gathered the required data. We had a 100% response rate to the questionnaire survey both for the intervention groups and control groups.

3.8. Data Analysis and Presentations

The collected quantitative data were analyzed using the software Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS), version 26. Independent sample t-tests were used to compare the means of the intervention and control groups, with confidence intervals for statistical significance. The effect size was used to measure changes in the mean values. We chose these tests because the intervention and control groups being compared are naturally distinct and not related in any way, and the two groups involved the random assignment of participants. In sum, independent group tests were chosen, as we wanted to compare the means of the CL intervention and control groups. The variables were validated using confirmatory factor analysis before the main analyses.

4. Results

4.1. Preliminary Analysis Results and Descriptive Profiles

The observations in this investigation were independent due to lack of correlation between the groups or participants. A sufficient sample size was obtained by including all students in two courses.

Before the main study, two education evaluation experts reviewed the questionnaire items to check their validity, and the researchers took correction measures as recommended. We carried out reliability tests to determine the survey questionnaire’s dependability. Cronbach’s alpha was assessed after the post-test. The Cronbach’s coefficient for each measure is sufficiently high, attesting to the value of each item in each measure, with an alpha (α) range of 0.76 to 0.93 for the total items for each measure [91].

The post-intervention questionnaire included 193 participants, with 5 omitted due to data omission, resulting in 188 participants in the final sample. Table 1 presents the descriptive profiles of the students’ demographics.

Table 1.

Descriptive profiles of the student demographics.

Table 1 shows comparably equal numbers of participants across the intervention and control groups, with equal proportions across department and gender. Residential status distributions were predominantly on campus (87%). The study found a consistent pattern in the age and CGPA scores across the intervention and control groups, indicating that the sample and measures used appear proportional.

4.2. Results of t-Tests across the Intervention and Control Groups

Three independent sample t-tests were conducted for the sample (n = 99) enrolled in the course “Risk Management and Insurance” and the sample (n = 94) enrolled in the course “Foundation Engineering I” as a preliminary analysis. Table 2 presents the summary results of the t-tests for the sample enrolled in the course “Risk Management and Insurance”.

Table 2.

The t-test results of the dependent measures between the CL groups and customary lecture groups enrolled for the course “Risk Management and Insurance”.

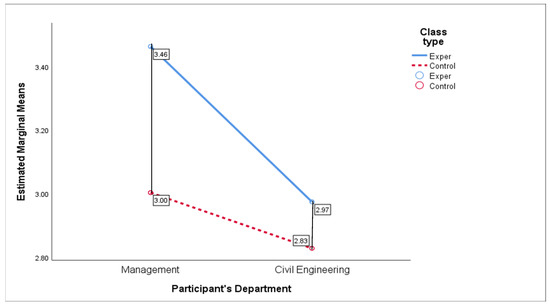

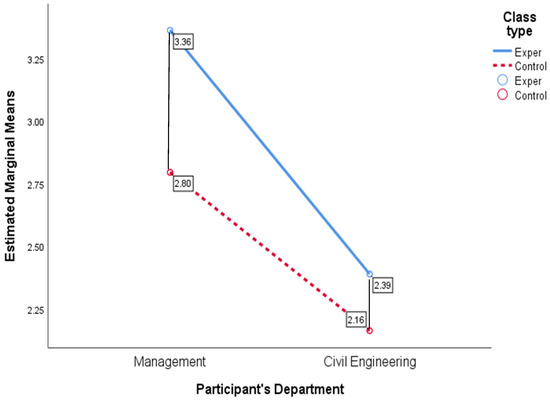

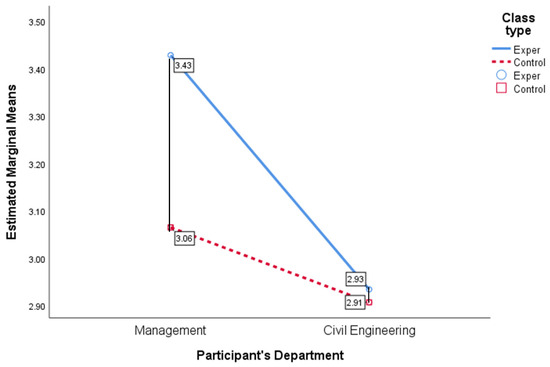

As shown in Table 2, an independent sample t-test showed that students in the CL intervention group (M = 3.46; SD = 0.56) reported greater levels of active and cooperative learning (t = −3.42, p < 0.001, and d = 0.70) than those in the control group (M = 3.02; SD = 0.70). Similarly, students in the CL intervention group (M = 3.36; SD = 0.70) reported higher levels of student–teacher relationships (t = −3.83, p < 0.001, and d = 0.78) than the control group (M = 2.78; SD = 0.80). Again, students in the CL intervention group (M = 3.43; SD = 0.60) reported higher levels of personal and social development outcomes (t = −2.41, p = 0.018, and d = 0.52) than the control group (M = 3.06; SD = 0.84). If we look at the mean scores for the three variables, we can see that the students in the CL group reported higher levels of active and cooperative learning, student–teacher relationships, and personal and social development (3.36 ≤ mean ≥ 3.46) than the students in the control group (2.78 ≤ mean ≥ 3.06). For the Management sample, the results of this study indicate a statistically significant difference between the mean values of the CL intervention and the regular, lecture-based control groups. Specifically, the intervention group had a higher level of active and cooperative learning, student–teacher relationships, and personal and social development outcomes. The effect sizes were medium, with Cohen’s d values of 0.52, 0.70, and 0.78. Similar independent sample t-tests were conducted for the student sample enrolled in the “Foundation Engineering I” course (n = 93). Table 3 presents the summary results of the t-tests for the Engineering sample.

Table 3.

The t-test results of the dependent measures between the CL groups and customary lecture groups enrolled for the course “Foundation Engineering I”.

As shown in Table 3, an independent sample t-test showed that the CL intervention group (M = 2.97; SD = 0.63) reported slightly higher levels of active and cooperative learning (t = −1.09; p = 0.279) than the control group (M = 2.83; SD = 0.60). Similarly, students in the CL intervention group (M = 2.45; SD = 0.88) reported slightly higher levels of student–teacher relationships (t = −1.61, p = 0.111, and d = 0.78) than the control group (M = 2.16; SD = 0.81). Again, students in the CL intervention group (M = 2.93; SD = 0.62) reported slightly higher levels of personal and social development outcomes (t = −0.17; p = 0.870) than those in the control group (M = 2.91; SD = 0.56). It is clear from Table 3 that the results show the slightest difference in the average scores between the CL group and the regular lecture control group across the three domains measured. However, the results indicated no significant difference between the CL and control groups in the three outcomes measured.

We used boxplots to visualize the mean differences between the CL intervention and control groups and provide more information about the mean difference of the variables measured. The boxplots enable us to visualize the magnitude of mean differences by looking at the slope of the line. Figure 1, Figure 2 and Figure 3 are visual representations of the mean group differences in students’ active and cooperative learning, student–teacher interactions, and personal and social development outcomes for both the Management and Engineering samples.

Figure 1.

A visual representation of the mean differences in students’ active and cooperative learning scores between the CL groups and the regular lecture groups across the two major fields.

Figure 2.

A visual representation of the mean differences in student–teacher relationship scores between the CL groups and the regular lecture groups across the two major fields.

Figure 3.

A visual representation of the mean differences in personal and social development outcome scores between the CL groups and the regular lecture groups across the two major fields.

5. Discussion

Based on social interdependence and social constructivism theories, this study examined how a CL pedagogical method impacts the engagement and outcomes of undergraduate students taking Management and Engineering courses at an Ethiopian university. This was conducted through a quasi-experimental post-test control group design by comparing the CL pedagogical conditions with regular lecture-based instruction and a self-reported questionnaire to measure the students’ engagement and learning outcomes.

This study shows that students who participated in CL intervention groups demonstrated higher engagement due to their active and cooperative environment and attained better personal and social development outcomes compared to those in regular lecture-based settings. Previous research also suggests that CL promotes active engagement [92,93], a deeper understanding and retention of learned material [60,94], higher student levels of self-directed learning [95], and better positive relationships and psychological health [24]. While students in lecture-based settings may have shown moderate gains, they may have lacked the increased engagement and personal and social development observed in CL groups.

Looking at the t-values for each variable measured in Table 2, the Management student group in the CL condition had significantly higher scores compared to the regular lecture-based instruction group. The effect sizes are medium effects with intermediate magnitudes [96]. Given that the intervention was used for the first time, it was encouraging, as the results can be projected for the entire semester course. According to the t-values for each variable examined in Table 3, the Engineering student group in the CL condition had slightly higher scores compared to the regular lecture-based teaching group, but the mean differences were not statistically significant.

Similar to the results found in the studies from this field, group difference analyses showed that students who took part in CL lessons significantly outperformed the regular lecture group on measures of engagement [21,40] and the attainment of learning outcomes [93,94,95]. This discovery supports the social interdependence theory and supports the findings of other investigations [21,97].

The success came about by adhering to the core principles of the CL pedagogical paradigm. The intervention teachers specifically realized that they did five things jointly, including maintaining a focus, developing relationships with the researcher and students, consistent implementation guided by a lesson plan, capacity building via a more informal platform, and negotiating how to proceed with the researcher and students.

In practice, this entails reframing the way courses are provided in a unique approach from the status quo model [98]. These instructors, like many other HE educators, had too many “top” priorities, but they showed dedication to the execution of CL teachings. The instructors made it their top priority (non-negotiable) responsibility to apply to the CL lessons.

The quality of university instruction, particularly through the use of CL pedagogies, significantly impacts undergraduate students’ active engagement in learning and promotes the growth of interpersonal skills [99]. However, universities face pressure to maintain high-quality instruction. The results of this study and other studies demonstrate that incorporating CL pedagogies can help to resolve these issues [100].

At the individual level, promoting effective teaching in HE involves helping teachers fulfill their responsibilities [83], adopting a learner-centered perspective [26], inspiring innovation [101], and facilitating improvements in student learning [18]. As the findings of this study and others suggest, despite limited resources and intense competition, universities can improve their teaching quality by implementing CL instruction, [102,103], as well as improve student engagement [42,97] and learning outcomes [104].

The quantitative and qualitative components complement each other by offering both quantitative data on the outcomes of CL and qualitative insights into the experiences and perspectives of the teachers (educators) implementing the CL interventions. The qualitative findings can help contextualize the quantitative results, offering explanations for why certain outcomes occurred and shedding light on the practical considerations and challenges involved in implementing CL pedagogies. Together, they provide a more comprehensive understanding of the effects of CL on undergraduate students’ engagement and learning outcomes from both student and teacher perspectives.

The findings of the current study provide empirical support for the idea that switching from traditional lecture-based education to more student-centered teaching strategies, such as CL, serves several purposes that improve student engagement and personal and social development outcomes. Thus, to improve academic results as well as engagement in learning and the development of essential soft skills, universities in Ethiopia and others with similar settings need to consider including CL in their curricula.

Limitations

This study has limitations. First, rather than students, the authors assigned groups to the pedagogical conditions, as they did in many previous quasi-experimental designs. As a result, it was impossible to determine if the two groups would have been comparable if it were not for the instructional approach. Additionally, non-equivalent control group designs may result in non-equivalence due to factors such as selection bias, where participants are randomly assigned to groups, favoring certain characteristics over others, potentially influencing the outcome. To enhance this shortfall in future studies, researchers can use strategies like stratification and randomization to reduce differences between groups. Longitudinal designs, which measure changes over time, can also be considered to control for individual differences. These strategies can enhance the validity and reliability of non-equivalent control group designs.

6. Conclusions

According to the study’s findings, the study hypothesis is valid for the “Risk Management and Insurance” course, and there are sufficient data in this study to support the hypothesis. According to the findings in the Management sample, the CL intervention pedagogical model significantly, and with moderate impact sizes, enhanced student outcomes and engagement. Although the study premise might be accurate in the “Foundation Engineering I” course, there were not enough data in this study to back it up. Promoting effective teaching in HE involves helping teachers fulfill their responsibilities, adopting a learner-centered perspective, inspiring innovation, and facilitating student engagement and learning outcomes. This study suggests that both CL and regular lecture-based instructions have their merits. However, CL’s benefits for enhancing student engagement and personal and social development outcomes make it a valuable method for teaching and learning in HE. The study contributes to the growing body of evidence supporting active learning strategies and provides insights for higher educators looking to improve their teaching effectiveness.

6.1. Theoretical Implications

By examining the effects of CL on student engagement and learning outcomes in undergraduate Management and Engineering courses, this study makes a distinctive contribution to the literature on social interdependence theory and CL. The CL pedagogical model and its analysis offer a persuasive educational justification for bringing the research findings on undergraduate education from two lines of research—student engagement and learning outcomes—into one cohesive whole.

6.2. Practical Implications

This study’s findings offer empirical evidence that CL activities—rather than regular lecture-based instruction—should be the recommended teaching method in HE classrooms. CL could be used as a pedagogy by colleges of business, economics, and technology as well as other disciplines to assist undergraduate students in simultaneously increasing their engagement and outcomes. The study’s conclusions support the suggestion that HE institutions should emphasize the use of CL pedagogies. It also recommends providing ongoing PD opportunities for higher educators, embedding CL activities into the course design, and setting clear learning objectives.

This study uses a CL model to structure group activities and evaluate their effectiveness. It emphasizes five fundamental elements: positive interdependence, face-to-face interaction, individual accountability, interpersonal skills, and group processing. By incorporating these principles, university teachers can create interactive learning environments, promote cooperation, and develop mutual support among undergraduate students. The model and principles can be used for teaching, learning, and assessment practices. These simple yet effective CL pedagogies, such as think–pair–share, pyramiding, and others, encourage active participation and peer interaction. By incorporating this CL model and its principles into their teaching practice, university educators can create engaging, interactive learning environments that facilitate the development of cooperation and mutual support among undergraduate students.

6.3. Implications for Institutional Policy

The body of knowledge about teaching and learning in HE in Ethiopia is relatively new, and it is primarily focused on personal choice rather than what is recognized to be efficient. If the institutions wish to have more than the most recent fads driving Ethiopia’s HE system, they must rely on the evidence presented in this paper. According to the study’s findings, it is only via close collaboration between researchers and teachers that new opportunities for improving teaching practices, student learning, and developmental outcomes may be created.

Policymakers frequently place more emphasis on improving student achievement than on the educational processes and social components of university learning, which may have a substantial impact on students’ achievements. The level of student participation, in the meantime, used to be a neglected aspect of the policy debate surrounding the standard of undergraduate education. To improve student engagement and outcomes, it is essential to understand how to apply the CL pedagogical paradigm. The goal of effective teaching strategies in universities is to enhance student learning experiences and, subsequently, learning outcomes. To improve the quality of teaching and learning in undergraduate courses, policies should include CL instruction.

6.4. Recommendations for Future Research

This study focuses on the CL pedagogical approach as the cross-cutting element. However, its effectiveness may depend on various factors such as socio-economic background, cultural context, and geographic location. Future research should include a broad range of variables while investigating the effectiveness of pedagogical approaches. For example, researchers can explore the strength or quality of the pedagogical approach when aligned with specific curricula or educational standards and examine the quality of teacher–student relationships and peer interactions. The study also suggests exploring teacher training and PD in CL approaches to enhance their effectiveness. Additionally, future studies in the entire field of management and technology should incorporate more disciplines and metrics for assessing individual and institutional characteristics. To fully grasp the relative effectiveness of the CL pedagogies in future studies and analyze the mediating and/or moderating effects of these elements, it may be necessary to collect data on wider demographic indicators and curriculum concerns.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.A. and T.T.; methodology, A.A., H.W. and T.T.; validation, A.A. and T.T.; formal analysis, T.T., H.W. and R.M.G.; investigation, A.A. and H.W.; resources, T.T.; data curation, H.W. and R.M.G.; writing—original draft preparation, A.A., H.W. and T.T.; writing—review and editing, R.M.G.; visualization, T.T., H.W. and R.M.G.; supervision, R.M.G.; project administration, A.A. and H.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the College of Education and Behavioral Sciences, grant number CEBS/RP-209/2009.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical approval was provided by the Research Review Committee of the College of Education and Behavioral Sciences, Jimma University (Ref. No: RPS 653/18 and date of approval 9 February 2018).

Informed Consent Statement

Teacher participants and every student who took part in the study provided written informed consent before participating in the research.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Förtsch, C.; Sommerhoff, D.; Fischer, F.; Fischer, M.; Girwidz, R.; Obersteiner, A.; Reiss, K.; Stürmer, K.; Siebeck, M.; Schmidmaier, R.; et al. Systematizing Professional Knowledge of Medical Doctors and Teachers: Development of an Interdisciplinary Framework in the Context of Diagnostic Competences. Educ. Sci. 2018, 8, 207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coates, H. Assessing student learning outcomes internationally: Insights and frontiers. Assess. Eval. High. Educ. 2016, 41, 662–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krause, K.-L. Understanding and promoting student engagement in university learning communities. In Proceedings of the Sharing Scholarship in Learning and Teaching: Engaging Students, Townsville/Cairns, QLD, Australia, 21–22 September 2005; James Cook University: Townsville, QLD, Australia, 2005; pp. 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Axelson, R.D.; Flick, A. Defining Student Engagement. Chang. Mag. High. Learn. 2010, 43, 38–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuh, G.D.; Kinzie, J.; Schuh, J.H.; Whitt, E.J. Student Success in College: Creating Conditions That Matter; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Groccia, J.E. What Is Student Engagement? New Dir. Teach. Learn. 2018, 2018, 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yonezawa, S.; Jones, M.; Joselowsky, F. Youth engagement in high schools: Developing a multidimensional, critical approach to improving engagement for all students. J. Educ. Chang. 2009, 10, 191–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahu, E.R.; Nelson, K. Student engagement in the educational interface: Understanding the mechanisms of student success. High. Educ. Res. Dev. 2018, 37, 58–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J. Building bridges to student learning: Perceptions of the learning environment, engagement, and learning outcomes among Chinese undergraduates. Stud. Educ. Eval. 2018, 59, 195–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xerri, M.J.; Radford, K.; Shacklock, K. Student engagement in academic activities: A social support perspective. High. Educ. 2018, 75, 589–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Hu, W.; McNamara, O. Undergraduate student engagement at a Chinese university: A case study. Educ. Assess. Eval. Account. 2015, 27, 105–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Xue, E. Dynamic Interaction between Student Learning Behaviour and Learning Environment: Meta-Analysis of Student Engagement and Its Influencing Factors. Behav. Sci. 2023, 13, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almarghani, E.M.; Mijatovic, I. Factors affecting student engagement in HEIs-it is all about good teaching. Teach. High. Educ. 2017, 22, 940–956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakkenes, I.; Vermunt, J.D.; Wubbels, T. Teacher learning in the context of educational innovation: Learning activities and learning outcomes of experienced teachers. Learn. Instr. 2010, 20, 533–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chow, J.; Tse, A.; Armatas, C. Assessing the university student perceived learning gains in generic skills. J. Appl. Res. High. Educ. 2020, 12, 993–1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilgo, C.A.; Sheets, J.K.E.; Pascarella, E.T. The link between high-impact practices and student learning: Some longitudinal evidence. High. Educ. 2015, 69, 509–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudhumbu, N. Antecedents and consequences of effective implementation of cooperative learning in universities in Zimbabwe. J. Res. Innov. Teach. Learn. 2024, 17, 4–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, Z.; LuXi, Z. Implementing a cooperative learning model in universities. Educ. Stud. 2012, 38, 165–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamarik, S. Does cooperative learning improve student learning outcomes? J. Econ. Educ. 2007, 38, 259–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, K. Engaging Students through Active and Cooperative Learning; University of Wisconsin—Platteville: Platteville, WI, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, K.; Sheppard, S.; Johnson, D.; Johnson, R. Pedagogies of engagement: Classroom-based practices. J. Eng. Educ. 2005, 94, 87–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Springer, L.; Stanne, M.E.; Donovan, S.S. Effects of Small-Group Learning on Undergraduates in Science, Mathematics, Engineering, and Technology: A Meta-Analysis. Rev. Educ. Res. 1999, 69, 21–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, D.W.; Johnson, R.T. Social interdependence theory and university instruction: Theory into practice. Swiss J. Psychol. Schweiz. Z. Psychol. Rev. Suisse Psychol. 2002, 61, 119–129. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, D.W.; Johnson, R.T. An Educational Psychology Success Story: Social Interdependence Theory and Cooperative Learning. Educ. Res. 2009, 38, 365–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillies, R. Cooperative learning: Review of research and practice. Aust. J. Teach. Educ. (Online) 2016, 41, 39–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dole, S.; Bloom, L.; Kowalske, K. Transforming Pedagogy: Changing Perspectives from Teacher-Centered to Learner-Centered. Interdiscip. J. Probl.-Based Learn. 2015, 10, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillies, R. Cooperative Learning: Integrating Theory and Practice; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Tadesse, T. Cooperative Learning for Academic, Personal, and Social Development in Higher Education in Africa. In Contemporary Global Perspectives on Cooperative Learning: Applications Across Educational Contexts; Gillies, R., Mills, B., Davidson, N., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2023; pp. 232–251. [Google Scholar]

- Noben, I.; Deinum, J.F.; Douwes-van Ark, I.M.E.; Hofman, W.H.A. How is a professional development programme related to the development of university teachers’ self-efficacy beliefs and teaching conceptions? Stud. Educ. Eval. 2021, 68, 100966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabriz, S.; Hansen, M.; Heckmann, C.; Mordel, J.; Mendzheritskaya, J.; Stehle, S.; Schulze-Vorberg, L.; Ulrich, I.; Horz, H. How a professional development programme for university teachers impacts their teaching-related self-efficacy, self-concept, and subjective knowledge. High. Educ. Res. Dev. 2021, 40, 738–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dejene, W. The practice of modularized curriculum in higher education institution: Active learning and continuous assessment in focus. Cogent Educ. 2019, 6, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biku, T.; Demas, T.; Woldehawariat, N.; Getahun, M.; Mekonnen, A. The effect of teaching without pedagogical training in St. Paul’s Hospital Millennium Medical College, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Adv. Med. Educ. Pract. 2018, 9, 893–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piper, B. Student-Centered Pedagogy’s Causal Mechanisms: An Explanatory Mixed Methods Analysis of the Impact of In-Service Teacher Professional Development in Ethiopia; Harvard University: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Altinyelken, H.K. Pedagogical renewal in sub-Saharan Africa: The case of Uganda. Comp. Educ. 2010, 46, 151–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luneta, K. Designing continuous professional development programmes for teachers: A literature review. Afr. Educ. Rev. 2012, 9, 360–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schweisfurth, M. Learner-centred education in developing country contexts: From solution to problem? Int. J. Educ. Dev. 2011, 31, 425–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Negassa, T.; Engdasew, Z. The Impacts and Challenges of Pedagogical Skills Improvement Program at Adama Science and Technology University. Int. J. Instr. 2017, 10, 19–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabulawa, R. Teaching and Learning in Context: Why Pedagogical Reforms Fail in Sub-Saharan Africa; CODESRIA: Dakar, Senegal, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Bananuka, T.H. The Pursuit of Critical-Emancipatory Pedagogy in Higher Education. In Higher Education in Sub-Saharan Africa in the 21st Century: Pedagogy, Research and Community-Engagement; Daniel, B.K., Bisaso, R., Eds.; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2023; pp. 69–86. [Google Scholar]

- Herrmann, K.J. The impact of cooperative learning on student engagement: Results from an intervention. Act. Learn. High. Educ. 2013, 14, 175–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azila-Gbettor, E.M.; Abiemo, M.K. Moderating effect of perceived lecturer support on academic self-efficacy and study engagement: Evidence from a Ghanaian university. J. Appl. Res. High. Educ. 2021, 13, 991–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Admasu, M.A. The Impact of Cooperative Learning on Students’ Paragraph Writing Skills: The Case of Third Year Health Informatics Students at University of Gondar. Ethiop. Renaiss. J. Soc. Sci. Humanit. 2020, 7, 70–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tadesse, T.; Manathunga, C.; Gillies, R. The Hidden Lacunae in the Ethiopian Higher Education Quality Imperatives: Stakeholders’ Views and Commentaries. Ethiop. J. Educ. Sci. 2018, 14, 75–94. [Google Scholar]

- Smart, K.L.; Witt, C.; Scott, J.P. Toward Learner-Centered Teaching:An Inductive Approach. Bus. Commun. Q. 2012, 75, 392–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bundick, M.J.; Quaglia, R.J.; Corso, M.J.; Haywood, D.E. Promoting Student Engagement in the Classroom. Teach. Coll. Rec. 2014, 116, 1–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, G.P.; Jones, S.; Bean, J.C. Teaching Real-World Applications of Business Statistics Using Communication to Scaffold Learning. Bus. Prof. Commun. Q. 2015, 78, 314–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowparvar, M.A.; Ashour, O.; Ozden, S.G.; Knight, D.; Delgoshaei, P.; Negahban, A. An Assessment of Simulation-Based Learning Modules in an Undergraduate Engineering Economy Course. In Proceedings of the 2022 ASEE Annual Conference & Exposition, Minneapolis, MN, USA, 26–29 June 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Cavanagh, M. Students’ experiences of active engagement through cooperative learning activities in lectures. Act. Learn. High. Educ. 2011, 12, 23–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warfa, A.R.M. Using Cooperative Learning To Teach Chemistry: A Meta-analytic Review. J. Chem. Educ. 2016, 93, 248–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumgardner, C. Cooperative Learning as a Supplement to the Economics Lecture. Int. Adv. Econ. Res. 2015, 21, 391–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coetzee, A.; Imenda, S.N. Effects of outcomes-based education and traditional lecture approaches in overcoming alternative conceptions in physics. Afr. J. Res. Math. Sci. Technol. Educ. 2012, 16, 145–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slavin, R.E. Instruction based on cooperative learning. In Handbook of Research on Learning and Instruction; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2011; pp. 358–374. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, D.W.; Johnson, R.T.; Smith, K.A. Cooperative Learning: Improving University Instruction by Basing Practice on Validated Theory. J. Excell. Coll. Teach. 2014, 25, 85–118. [Google Scholar]

- Kyndt, E.; Raes, E.; Lismont, B.; Timmers, F.; Cascallar, E.; Dochy, F. A meta-analysis of the effects of face-to-face cooperative learning. Do recent studies falsify or verify earlier findings? Educ. Res. Rev. 2013, 10, 133–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aliyu, J.; Osman, S.; Kumar, J.A.; Talib, C.A.; Jambari, H. Students’ Engagement through Technology and Cooperative Learning: A Systematic Literature Review. Int. J. Learn. Dev. 2022, 12, 23–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdulwahhab, M.L.; Hashim, B.H. The effect of cooperative learning strategy on the engagement in architectural education. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2020, 881, 012004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewin, K. A Dynamic Theory of Personality-Selected Papers; Read Books Ltd.: Redditch, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Deutsch, M. A theory of cooperation and competition. Hum. Relat. 1949, 2, 129–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, D.W.; Johnson, R.T. New Developments in Social Interdependence Theory. Genet. Soc. Gen. Psychol. Monogr. 2005, 131, 285–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ali Sulaiman, M.A.; Singh Thakur, V. Effects of Cooperative Learning on Cognitive Engagement and task achievement: A study of Omani Bachelor of Education program EFL students. Arab World Engl. J. (AWEJ) 2022, 13, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gokhale, A.A. Collaborative Learning Enhances Critical Thinking. Ournal. J. Educ. 1995, 7, 22–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeVries, R. Piaget’s child: Not a lonely scientist but a cooperator. In Proceedings of the Invited Address to Constructivist Research and Practice Special Interest Group of the American Educational Research Association, San Francisco, CA, USA, 18–22 April 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Piaget, J. To Understand Is to Invent: The Future of Education; Penguin Books: London, UK, 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Csikszentmihalyi, M. Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience, 1st ed.; Harper & Row: New York, NY, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Fuller, M.B.; Wilson, M.A.; Tobin, R.M. The national survey of student engagement as a predictor of undergraduate GPA: A cross-sectional and longitudinal examination. Assess. Eval. High. Educ. 2011, 36, 735–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fredricks, J.A.; McColskey, W. The Measurement of Student Engagement: A Comparative Analysis of Various Methods and Student Self-Report Instruments; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 2012; pp. 763–782. [Google Scholar]

- Fang, J.; Vong, J.; Fang, J. Exploring student engagement in fully flipped classroom pedagogy: Case of an Australian business undergraduate degree. J. Educ. Bus. 2022, 97, 76–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maroco, J.; Maroco, A.L.; Campos, J.; Fredricks, J.A. University student’s engagement: Development of the University Student Engagement Inventory (USEI). Psicol.-Reflex. E Crit. 2016, 29, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fredricks, J.A.; Filsecker, M.; Lawson, M.A. Student engagement, context, and adjustment: Addressing definitional, measurement, and methodological issues. Learn. Instr. 2016, 43, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fredricks, J.A.; Blumenfeld, P.C.; Paris, A.H. School Engagement: Potential of the Concept, State of the Evidence. Rev. Educ. Res. 2004, 74, 59–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuh, G. Why Integration and Engagement are Essential to Effective Educational Practice in the Twenty-first Century. Peer Rev. 2008, 10, 27–28. [Google Scholar]

- Kuh, G. The National Survey of Student Engagement: Conceptual and Empirical Foundations. New Dir. Institutional Res. 2009, 2009, 5–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carini, R.M.; Kuh, G.D.; Klein, S.P. Student Engagement and Student Learning: Testing the Linkages. Res. High. Educ. 2006, 47, 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keeling, R.; Hersh, R. We’re Losing Our Minds: Rethinking American Higher Education; Palgrave Macmillan US: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Banta, T.W.; Palomba, C.A.; Kinzie, J. Assessment Essentials: Planning, Implementing, and Improving Assessment in Higher Education; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- AAstin, A. What Matters in College?: Four Critical Years Revisited; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, M.D.; Linn, R.L.; Gronlund, N.E. Measurement and Assessment in Teaching, 10th ed.; Merrill: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Gonyea, R.; Miller, A. Clearing the AIR about the use of self-reported gains in institutional research. New Dir. Institutional Res. 2011, 2011, 99–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J.; Creswell, J.D. Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches, 5th ed.; SAGE Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Strayhorn, T.L. Analyzing the Short-Term Impact of a Brief Web-Based Intervention on First-Year Students’ Sense of Belonging at an HBCU: A Quasi-Experimental Study. Innov. High. Educ. 2023, 48, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Clasing-Manquian, P. Quasi-Experimental Methods: Principles and Application in Higher Education Research. In Theory and Method in Higher Education Research, Huisman, J., Tight, M., Eds.; Theory and Method in Higher Education Research; Emerald Publishing Limited: Leeds, UK, 2023; Volume 9, pp. 43–62. [Google Scholar]

- Tadesse, T.; Asmare, A.; Ware, H. Exploring Teachers’ Lived Experiences of Cooperative Learning in Ethiopian Higher Education Classrooms: A Phenomenological-Case Study. Educ. Sci. 2021, 11, 332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tadesse, T.; Gillies, R. Nurturing Cooperative Learning Pedagogies in Higher Education Classrooms: Evidence of Instructional Reform and Potential Challenges. Curr. Issues Educ. 2015, 18, 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Vygotsky, L.S. Mind in Society: The Development of Higher Psychological Processes; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Kearsley, G.; Shneiderman, B. Engagement Theory: A Framework for Technology-Based Teaching and Learning. Educ. Technol. 1998, 38, 20–23. [Google Scholar]

- Doolittle, P.E. Understanding Cooperative Learning through Vygotsky’s Zone of Proximal Development. In Proceedings of the Lilly National Conference on Excellence in College Teaching, Columbia, SC, USA, 2–4 June 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Hedegaard, M. The zone of proximal development as basis for instruction. In Vygotsky and Education: Instructional Implications and Applications of Sociohistorical Psychology; Moll, L.C., Ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1990; pp. 349–371. [Google Scholar]

- Tadesse, T.; Gillies, R.; Campbell, C. Testing Models and Measurement Invariance of the Learning Gains Scale. Educ. Sci. 2018, 8, 192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tadesse, T.; Manathunga, C.; Gillies, R. The development and validation of the student engagement scale in an Ethiopian university context. High. Educ. Res. Dev. 2018, 37, 188–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tadesse, T.; Gillies, R. Testing robustness, model fit, and measurement invariance of the Student Engagement Scale in an African university context. Aust. J. Career Dev. 2017, 26, 92–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunnally, J.C. Psychometric Theory; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Bizimana, E.; Mutangana, D.; Mwesigye, A. Students’ Perceptions of the Classroom Learning Environment and Engagement in Cooperative Mastery Learning-Based Biology Classroom Instruction. Educ. Res. Int. 2022, 2022, 5793394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhabeedi, E. Increasing Students’ Participation by Using Cooperative Learning in Library and Research Course. Master’s Thesis, Department of Curriculum and Instruction, State University of New York at Fredonia, Fredonia, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Tran, V.D. The effects of cooperative learning on the academic achievement and knowledge retention. Int. J. High. Educ. 2014, 3, 131–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breed, B. Exploring a co-operative learning approach to improve self-directed learning in higher education. J. New Gener. Sci. 2016, 14, 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Lenhard, W.; Lenhard, A. Calculation of Effect Sizes; Psychometrica: Dettelbach, Germany, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agonafir, A.M. Using cooperative learning strategy to increase undergraduate students’ engagement and performance. Educ. Action Res. 2023, 31, 981–997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roseth, C.J.; Lee, Y.K.; Saltarelli, W.A. Reconsidering Jigsaw Social Psychology: Longitudinal Effects on Social Interdependence, Sociocognitive Conflict Regulation, Motivation, and Achievement. J. Educ. Psychol. 2019, 111, 149–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, S.-I.; Son, H. Effects of Cooperative Learning on the Improvement of Interpersonal Competence among Students in Classroom Environments. Int. Online J. Educ. Teach. 2020, 7, 17–28. [Google Scholar]

- Ballantine, J.; McCourt Larres, P. Cooperative learning: A pedagogy to improve students’ generic skills? Educ. Train. 2007, 49, 126–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, J.; Figueiredo, A.S.; Vieira, M. Innovative pedagogical practices in higher education: An integrative literature review. Nurse Educ. Today 2019, 72, 12–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tran, V.D. Does Cooperative Learning Increase Students’ Motivation in Learning? Int. J. High. Educ. 2019, 8, 12–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wyk, M.M.v. The Effects of the STAD-Cooperative Learning Method on Student Achievement, Attitude and Motivation in Economics Education. J. Soc. Sci. 2012, 33, 261–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slavin, R.E. Cooperative Learning and Academic Achievement: Why Does Groupwork Work?. [Aprendizaje cooperativo y rendimiento académico:¿ por qué funciona el trabajo en grupo?]. An. Psicol. Ann. Psychol. 2014, 30, 785–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).