1. Introduction

The academic achievement of students is a critical issue in education. This output is influenced by many factors. Several factors have been identified as influencing academic success, including the school, the teacher, the curriculum, the home, and parental sociocultural background [

1]. Family involvement in the educational process and its connection to student achievement in school have become an extensively researched topic at the international level (achievement goal theory) [

2,

3,

4,

5]. Research has highlighted the diversity of factors that influence school performance. It has examined how individual goals, self-evaluation, and behavioral patterns influence levels of student achievement as a function of environmental interactions [

6,

7,

8] and how to increase parenting effectiveness. It also shows the importance of parental support, as children who believe they can perform perform better. This study aims to examine the relationship between parental involvement (PI) and school achievement. International research on the family–school relationship typically describes a positive effect on achievement and peer acceptance factors [

9,

10,

11]. The literature generally finds a causal relationship where parental involvement influences academic performance; however, this effect is not necessarily conclusive, as there are papers that report that parents of higher-achieving children are more involved while others found them to be less involved. In our study, we accept this causal model, albeit with reservations.

In the literature, parental activity is a multifaceted concept (motivation and socialization habits, parenting style, parental responsiveness) and capacity (socio-cultural capital, labor market activity, residential advantage or disadvantage, nationality), as well as educational policy, i.e., development levels (task sharing, volunteering, support, school climate, etc.) [

3,

12,

13]. Over the past twenty years, a consensus has emerged on the positive nature of a strong family–school relationship and school achievement, as confirmed by Wilder’s [

14] meta-synthesis, which compared a total of nine meta-analyses and reported positive effect sizes in all cases, regardless of the conceptualization or measurement used. Additionally, we emphasize the importance of viewing parental involvement through a pluralistic lens to foster school inclusion and equity [

15].

Students from disadvantaged backgrounds may have limited access to educational resources and opportunities. Parental involvement can help level the playing field, and one of the most common forms of such involvement is homework support. There are also growing differences in the composition of the student population in terms of academic performance, and the possibility of compensating for these differences (albeit within certain limits) is in the hands of parents. At the same time, parental support for homework preparation, which is primarily aimed at compensating for this learning disadvantage, also requires the cooperation of teachers [

16]. For understandable reasons, parents may not have the pedagogical and methodological knowledge that teachers have, and there may be significant differences in the cultural background of each family, where collaboration with school teachers is essential for effective home learning [

16,

17]

In Jeynes’ [

18] study, parental involvement (defined as parent–child communication, at-home learning (tutoring), and regular and quality contact with the school) and student academic achievement (defined by variables such as grades, test scores, competitions, awards, behavioral ratings, and teacher characteristics) showed a positive correlation for urban students regardless of gender and nationality [

18]. However, there are components of PI for which there is no clear positive correlation. One example is parental participation in homework. Parents are often involved in their children’s education through involvement in homework [

19], but scientific findings on homework involvement are mixed, and most studies have found a negative relationship with academic achievement. For example, a study based on the data of the Programme for International Student Assessment found that parental involvement at home, specifically for academic purposes, was negatively correlated with student achievement, which is mainly attributed to the fact that parents are helping more when students have difficulties with their studies. Interestingly, when the help that parents give with homework is autonomy-supportive, it has a positive relationship with academic achievement [

20,

21].

Other studies have also raised questions about the overall positive effect of parental involvement, in the case of school success or other fields or, for example, in health behavior [

22,

23]. It is important to note, however, that parental involvement in the home may have different effects on academic performance based on whether the parent acts as a rule-maker or as an active facilitator and supporter of preparation. It is also important to note that different manifestations of parental support for home learning have been observed at different ages, with parents behaving more as supportive, active facilitators in primary education and more as rule makers in secondary education. The differential polar effects of different types of parental involvement in homework can be seen not only by age but also by subject, with a negative effect for mathematics but a positive effect for subjects requiring mother tongue competence [

24]. Based on the findings of Boonk et al. [

25], parental involvement may contribute indirectly to academic achievement through the influence of other proximal student outcomes such as motivation, attitudes, and learning strategies. This aligns with the assumptions of the process model of parental involvement [

26,

27], which looks at learners as the authors of their academic success. According to this model, parental involvement does not directly contribute to students’ academic achievement but affects it by influencing the development of students’ learning attributes (academic self-efficacy, intrinsic motivation to learn, self-regulatory strategies, and social self-efficacy about teachers), which, in turn, are used by learners to support their academic success. A meta-analysis of previous studies has shown a positive effect of parental involvement in homework completion on academic achievement. This positive effect is not only reflected in a higher rate of homework completion, but also in improved academic achievement of primary school children as a result of practice while completing homework [

24,

28,

29].

In addition, parental involvement in homework preparation helps children to do their homework in a better mood and with a more positive attitude [

30,

31] and improves communication between parent and child [

27].

Other factors that call into question the generalizability of the impact of parental involvement are those connected to the socio-economic characteristics of the family. According to research results, the relationship between the forms of involvement (such as parent–child conversations or participation in school events) and academic achievement varies across racial/ethnic groups [

25]. Children’s academic performance and the level and form of the parents’ involvement also vary by the family’s socioeconomic status [

32] and some research suggests that children of low socioeconomic status may benefit more from their parents’ involvement than those coming from families with higher social status [

33]. Additionally, variations in the type and intensity of involvement—such as involvement in homework, school events, or communication with teachers—can produce differing impacts on academic performance. As a result of the moderating analysis, school involvement appeared to be particularly beneficial for more disadvantaged young people (i.e., those from low-educated families with lower prior attainment levels). The parental academic socialization of more advantaged young people was more conducive to their academic success (i.e., those from high-educated families with a high level of prior attainment) with no positive impact from parental involvement [

34].

A critical question in the context of performance and PI is how to measure learning outcomes. In his meta-analysis, Jeynes found that the effect of PI was weakest when it was measured by standardized tests [

35]. It is difficult to show a correlation, for example, for PISA tests, or the correlation is negative for PISA [

36]. This is a relevant result for our study because we will also use standardized tests as outcome indicators. But there are also differences by subject. There is a positive correlation between learning assistance in oral homework and achievement but a negative correlation for mathematics [

24].

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Participants

Our research analyzed data from Grade 6 and Grade 10 students participating in the 2019 Hungarian National Assessment of Basic Competencies (NABC). We analyzed the impact of parental involvement on children’s mathematics and reading achievement by the type of involvement and family background. Our secondary analysis of the NABC database was therefore conducted at the student level and did not analyze the effects at the institutional level. In addition to standard mathematics and reading scores, we used the student’s standard family background index score for the analysis, taking into account the educational attainment of parents, the number of books at home, the number of books the student owns, and the availability of a computer in the home environment.

The sample of the NABC is a population sample, so we had the data of all students attending school from the selected grades in Hungary in 2019 available for analysis. Our research analyzed data from 99,615 Grade 6 and 83,751 Grade 10 students. For descriptive statistics of the variables used in the analysis, see

Table 1 and

Table 2.

3.2. Instruments

Parental involvement was measured in the NABC by the frequency of a family member helping the student with learning and doing their homework, discussing what happened at school, and the frequency of the parent(s) attending parent–teacher conferences. Help with learning and homework and discussing what happened at school were measured on a four-point Likert scale, where the ratings had the following meaning: 1—never or almost never, 2—once or twice a month, 3—once or twice a week, 4—everyday or almost every day. In the case of the frequency of attending parent–teacher conferences, the following Likert scale was used: 1—my parent(s) almost never attended, 2—my parent(s) attended a few times, 3—my parents attended most of the conferences, 4—my parents attended all conferences. The scoring system for ability points is similar to the PISA assessment. Students take standardized tests in reading and mathematics. These tests measure not only knowledge but also students’ ability to apply their knowledge to real-world problems. The ability model is used to measure the knowledge of students in psychometrics [

31]. The mean of the scores is 1500 with a standard deviation of 200. Based on their scores, students were grouped into three levels. There are three categories of performance: below average, average, and above average.

The SES index is a one-dimensional summation of factors outside a particular school that affect student achievement (similar to the PISA ESCS index). The mean of the index is 0 with a standard deviation of 1. It is calculated based on parents’ highest educational level and home possessions.

In the case of PI, we did not use a composite indicator but instead separately examined the two types of parental involvement: school-based PI (attending parent–teacher conferences) and home-based PI (homework aid as academic home-based PI, conversations about school as non-academic home-based PI). The questionnaire was filled out by the students and represents their views on their parents’ involvement.

3.3. Working Procedures and Data Analysis

Our working procedure had three main steps: Since our research was a secondary analysis of the NABC database, the first step was data preparation, during which we removed duplicates and outliers and chose the target variables. As a second step, to test your hypotheses, we conducted multiple linear regression analysis. Firstly, we used the three forms of parental involvement available in the database (helping with homework, discussing what happened at school, and attending parent–teacher conferences) as independent variables, while the dependent variable in one model was the student’s mathematics score and the student’s reading score in the other model. To see if there was any difference in the effect of involvement on students’ reading and mathematics achievement by student grade, we conducted the analysis separately in the case of 6th- and 10th-grade students.

After this, we once again conducted multiple linear regression analysis to see if the effect of parental involvement differed by student SES. In this case, the three forms of parental involvement were used as independent variables, while the dependent variable in one model was the student’s mathematics score and the student’s reading score in the other model. To be able to address differences by student SES, we created two subsamples based on students’ standard family background index score: Those whose score was lower than average were put into the low SES group, while those with a higher-than-average score were put into the high SES group. The multiple linear regression analysis was conducted separately in the two groups.

4. Results

To test our first hypothesis, we conducted multiple linear regression analysis to examine the explanatory power of the different forms of parental involvement on student standard math and reading scores. Parental involvement in student learning was measured along three variables, namely the frequency of attendance at parent–teacher conferences, the frequency of family discussion of what happened at school, and the frequency of homework preparation and study assistance from parents, grandparents, and older siblings, as reported by the student. To test our hypothesis, data from sixth and tenth-grade students were analyzed separately, and multiple linear regression analysis was used to test the relationship of each form of involvement with reading and mathematics achievement.

According to our results, the multiple linear regression model explained 7.6% of the variation in Grade 6 students’ mathematics scores (F(3) = 2066.74,

p < 0.001, R

2 = 0.076), while for the reading comprehension score, the explanatory power of parental involvement was slightly higher in Grade 6 (F(3) = 2212.18,

p < 0.001, R

2 = 0.081). The multiple linear regression model explained 7.6% of the variance in Grade 10 students’ mathematics scores (F(3) = 1697.76,

p < 0.001, R

2 = 0.076), and the predictive power of parental involvement on reading scores was lower in Grade 10 compared to Grade 6 (F(3) = 1656.64,

p < 0.001, R

2 = 0.074). Beta values for the models are presented in

Table 3 and

Table 4. As seen in

Table 3 and

Table 4, the negative effect of family members helping the student with homework and studying on student mathematics scores is significantly stronger in Grade 6 than in Grade 10. This effect is less strong on reading scores and is similar in the two grades.

To test our second hypothesis, we created two groups based on the student’s family background index. Students with a standardized variable value of family background index less than 0 (below average) were placed in the lower-status group and those with a positive value (above average) were placed in the higher-status group. The data for the family background index were available for a total of 136,743 Grade 6 and Grade 10 students, of whom 47.1% (64,390) were in the lower-status group and 52.9% (72,353) were in the higher-status group. Our results showed that the variance explained by the model for reading was slightly greater in the higher-status group, at 8% (F(3) = 1955.9,

p < 0.001, R

2 = 0.08), while for the lower-status group 7.3% of variance was explained (F(3) = 1577.4,

p < 0.001, R

2 = 0.073). However, this relationship does not hold for all forms of involvement. The Beta values suggest that in the higher-status group, the recounting of school events does not have significant predictive power on the student’s standard reading score, and the frequency of attending parent–teacher meetings has a significantly smaller effect compared to the lower-status group. For the Beta values see

Table 5 and

Table 6.

For the standard mathematics scores, the model with the three variables measuring involvement explains 7.4% of the variance among lower-status respondents (F(3) = 1594.94,

p < 0.001, R

2 = 0.074), while the explained variance among higher-status respondents is slightly higher at 9.2% (F(3) = 2281.48,

p < 0.001, R

2 = 0.092). Furthermore, the coefficient values show that although the effect of all three forms of involvement was significant for both high- and low-status groups, the effect of each form of involvement differed between the two groups. While receiving help with studying and homework was found to have a negative effect in both groups, the association between discussing what happened in school and the student’s standard mathematics score was also negative for the higher-status groups. The frequency of attending parent–teacher meetings had a significantly weaker effect on mathematics achievement than that observed for the lower-status groups. For Beta values see

Table 5.

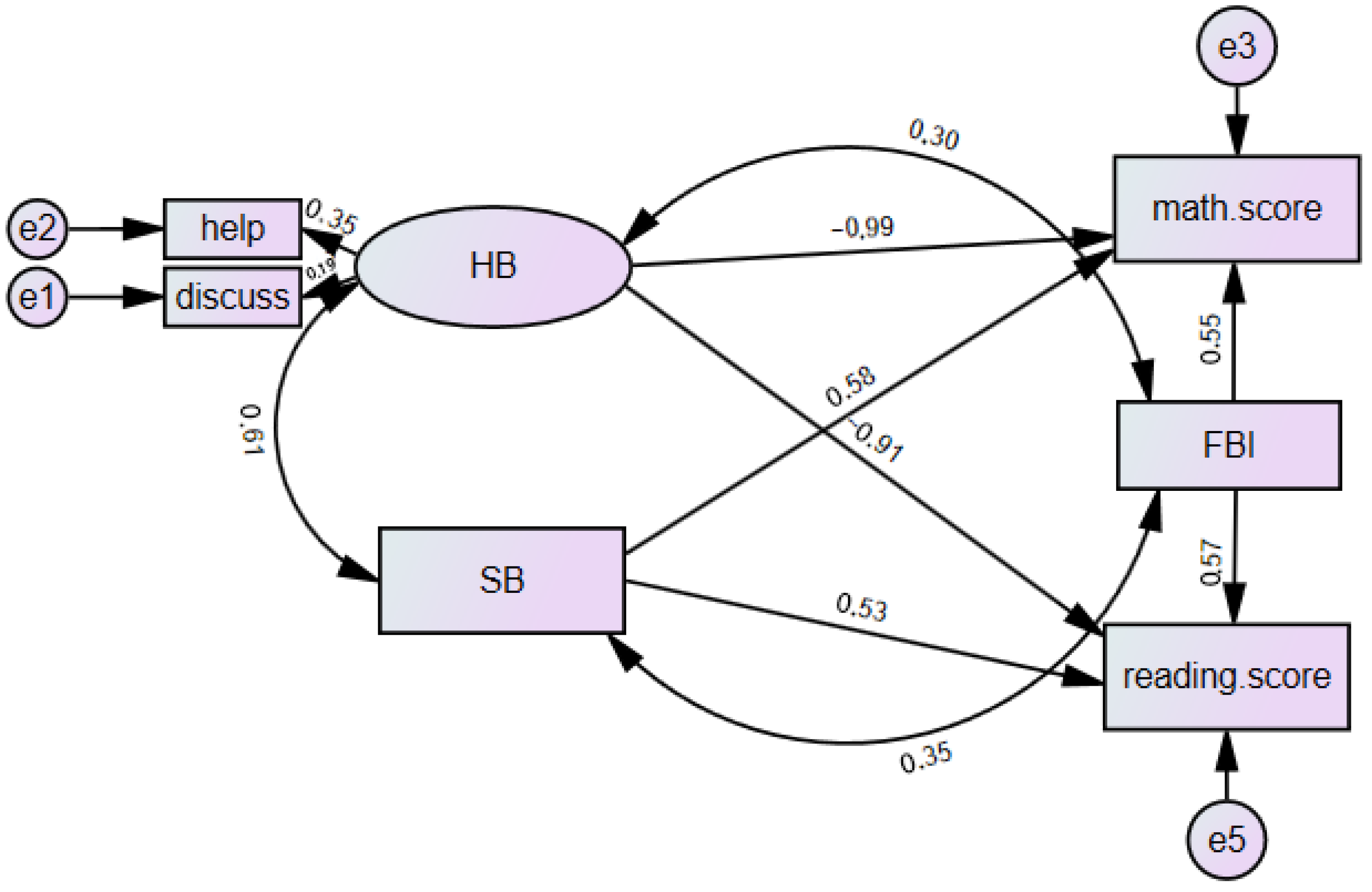

Structural Model Assessment

Using SPSS Amos, a structural equation model was generated to test for relationships between the variables, and all correlations were significant at the level

p < 0.001. A good fitting model is accepted if the value of the CMIN (χ

2), the [

32] index (TLI), and the Confirmatory fit index (CFI) is >0.9 [

35]. In addition, an adequate fitting model was accepted if the Amos computed value of the root mean square error approximation (RMSEA) is between 0.05 and 0.08 [

35] Despite the fit not being ideal, the parameters of interest (the hypothesized relationships) were statistically significant, supporting our research question. For the model, see

Figure 1.

The model indicates that help with homework is the most important factor in the home involvement cluster. There is less emphasis placed on discussing school activities. The effect of home involvement on achievement appears to be negative, whereas attendance at parent–teacher meetings appears to be positive for both achievement variables. Based on the model, the sociocultural background of the family is positively related to both PI variables but has a stronger effect on school involvement.

5. Discussion

Our analysis sought to answer two questions. Firstly, we investigated how different forms of parental involvement explain the performance of 6th and 10th graders in mathematics and reading comprehension, and secondly, we examined how this effect differs by socioeconomic status groups. According to our results, assistance in studying and homework is negatively related to student performance. At the same time, the frequency of attending parent–teacher conferences and discussing what happened at school are positive predictors of performance. School involvement has a much stronger effect on students at lower achievement levels when we examine the results by student achievement level in the 6th grade, but in 10th grade, the effect is just among the better performers.

Since the link between homework assistance and student achievement was negative, we can conclude that the ‘more involvement is better’ approach does not apply to this form of involvement. On the one hand, this result can be explained by the fact that more extensive parental involvement is in most cases only necessary for students who are lower achievers [

36,

37,

38]; on the other hand, children might perceive the intervention as unfavorable when receiving parental help with homework and studying [

33,

34]. This counterintuitive finding suggests that when parents are heavily involved in their children’s homework or academic tasks at home, it may signal either a lack of student autonomy or difficulties in understanding the material, which could lead to lower academic performance. Additionally, excessive involvement might also increase pressure on students, negatively affecting their motivation and self-esteem. According to the literature, the effect of parental support with at-home studying is positive if the parent supports autonomy, promotes a sense of competence, and is emotionally responsive to the child’s needs. Conversely, if parental homework assistance is controlling, intrusive, or interfering, is associated with negative parental emotions, and results in taking control of the child’s tasks, it hurts learning outcomes [

34,

36,

37,

39,

40,

41]. The study found a significant negative impact of parental assistance with homework on students’ standard scores in both mathematics and reading. This was consistent across both 6th and 10th grades. The regression analysis showed that helping with homework was associated with a decrease in performance, with the standardized coefficients indicating a robust negative relationship. In contrast, frequent attendance at parent–teacher conferences had a significant positive effect on both math and reading scores. This form of involvement was more effective in improving student outcomes compared to other forms of engagement. The frequency of discussing what happened at school also positively influenced academic achievement, though this effect varied depending on the SES of the students.

The regression model explained a moderate percentage of the variance in both math and reading scores. The effect of helping with homework was still negative, but the significance of discussing school activities diminished, particularly in reading scores. Additionally, the positive effect of attending parent–teacher conferences was less pronounced compared to lower-status students. If we include achievement groups in the analysis, we can confirm the same pattern for reading literacy and mathematics.

A structural equation model (SEM) was used to further assess the relationships between variables. Although the model did not achieve an ideal fit, key parameters indicated significant relationships that supported the study’s hypotheses. The model’s fit indices (CMIN, TLI, CFI, and RMSEA) suggested that while the model was adequate, there was room for improvement in explaining the variability in student achievement.

The study explored how these relationships varied between students from different socio-economic backgrounds. Students were categorized into higher-status and lower-status groups based on their family background index. The negative impact of helping with homework was significant, and the positive effects of attending parent–teacher conferences and discussing school activities were also evident. When examining the differences between lower and higher socioeconomic status groups, we found that discussing what happened at school had no significant effect on reading comprehension performance among the higher-status group, and that the frequency of attending parent–teacher conferences had significantly weaker explanatory power compared to the lower-status group. For mathematics achievement, discussing what happened at school had a positive effect in the lower-status group and a negative effect in the higher-status group, and the frequency of attending parent–teacher conferences had a significantly weaker explanatory power in the higher-status group compared to the lower-status group. This result highlights that parental involvement is more significant for lower-status individuals, confirming the findings of Dearing et al. [

30]. The study shows that parental involvement, particularly in school activities, has greater benefits for low-income families. School-based involvement provides crucial support for many families that may not be available otherwise, bridging the gap between the home and school environments for students from underprivileged backgrounds. High-status families may not see the same academic benefits from school-based involvement due to their existing access to resources like private tutoring, educational materials, and a conducive home environment for learning. Consequently, increased school activity participation may not significantly impact their children’s academic performance. The study underscores the complexities of the link between parental participation and student achievement, emphasizing the importance of the type and context of involvement. While school-based participation usually improves academic performance, home-based involvement can have the opposite effect, especially if it restricts adolescents’ autonomy or indicates academic difficulties. Socioeconomic status further complicates this relationship, with school-based involvement benefiting adolescents from lower socioeconomic backgrounds the most.

When interpreting our results, we must consider that the population under study is typically in primary education in grade 6 and secondary education in grade 10. In the latter case, students have already reached beyond the decision to continue their education leading to the choice of a secondary school, in which parental involvement is also significant [

42]. Thus, the frequency and forms of parental involvement may be related to the specificities of the different types of institutions. To be most effective, parental involvement should be specifically tailored to the needs and circumstances of both children and families. Schools should adopt an individualized approach to engaging parents, considering the socioeconomic factors that influence the effectiveness of participation. This will enable them to better support all students in achieving their academic objectives.

6. Limitations and Conclusions

In this study, we attempt to identify the generally influential forms of parental involvement and those which have differential impact. Revealing the differential effect is important for implementing future educational interventions in several student groups. The current study utilizes data solely from Hungary, which restricts the generalizability of the findings. Parental involvement practices and their effectiveness might differ across cultures and educational systems. Further research employing data from diverse populations is needed to determine the generalizability of the observed relationships.

Both parental involvement at home and at school is a very complex concept, all dimensions and indicators of which are almost impossible to identify and measure, but there are some indicators that are representative of the meaning of the concept and its manifestation in practice. The current study relies on quantitative measures of parental involvement, which might not capture the nuances of specific parental behaviors. We did not have data on whether or not parental support for home learning promotes autonomy, fosters a sense of competence, and is emotionally responsive to the child’s needs. The self-reported nature of parental involvement is a limitation of our study and qualitative research methods, such as focus groups or in-depth interviews, could provide richer details about the types of parental involvement that are most beneficial for student learning. As we are working with cross-sectional data, we are unable to determine whether parental involvement in the home, particularly helping with homework, is a cause or consequence, in other words, whether parents or relatives assist students who have deteriorated academically.

Our results suggest that not all forms of parental involvement have a clear positive impact on student academic achievement. Our research and analysis of a population sample suggest that it is essential to consider how parental support for at-home learning can be delivered in a manner that does not compromise student autonomy, as it is strongly negatively correlated with students’ reading and mathematics performance. At the same time, the positive correlation of discussing what happened at school with the child is evident, as well as the most widespread form of in-school parental involvement, attendance at teacher–parent conferences. Schools and policymakers should strongly emphasize appropriate ways to support the involvement of parents with a below-average SES, because, in this social group, the impact of parental support for learning and school-based involvement is more significant. Schools should guide how parents can support their children at home without exerting undue pressure. This might involve educating parents on fostering independent study habits rather than directly intervening in academic tasks, which can sometimes have adverse effects. In Hungary, schools often encourage parental involvement through various programs and activities. However, the extent and effectiveness of this involvement can vary significantly based on socio-economic factors. For instance, higher SES families are generally more involved in school-based activities, similar to the trends observed in other European countries. This involvement includes attending parent–teacher meetings, participating in school events, and being part of parent organizations.

Conversely, parents from lower SES backgrounds in Hungary may not be as involved due to various barriers, including work commitments, lack of time, and sometimes a perception that they cannot contribute effectively due to their educational background. This aligns with the study’s findings that for these families, increasing school-based involvement can be crucial for enhancing student achievement.