School Leaders’ Well-Being during Times of Crisis: Insights from a Quantitative Study in Kazakhstan

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review: School Leaders’ Well-Being during COVID-19 School Closures

2.1. Impact on School Leaders’ Well-Being

2.2. Stressors Faced by School Leaders

2.2.1. High Workload

2.2.2. Policy Communication and Consultations

2.2.3. Job Clarity

2.2.4. Care Work

2.2.5. Ensuring Equity

2.2.6. Parental Support and Tensions

2.2.7. Lack of Targeted Support

2.3. Socio-Demographics Associated with School Leaders’ Well-Being

2.3.1. Gender & Motherhood

2.3.2. Age and Experience

2.4. Work-Related Factors Supporting School Leaders’ Well-Being

2.4.1. Supportive Work Environment

2.4.2. Professional Development

2.4.3. Distributed and Collaborative School Leadership

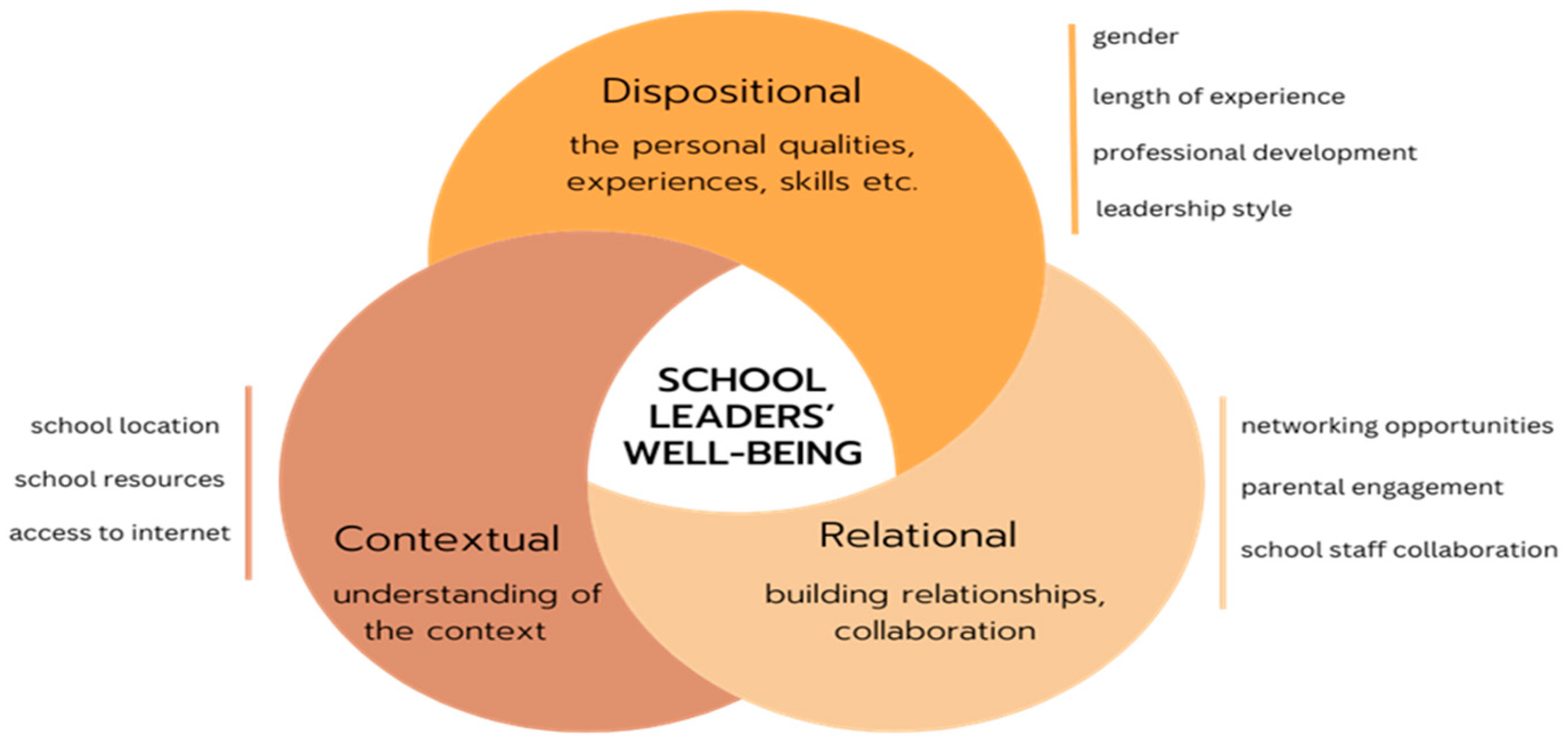

3. Conceptual Framework

4. Study Context

4.1. School System

4.2. School Leaders and Leadership

5. Methodology

5.1. Study Aim and Research Questions

- How are the dispositional, relational, and contextual factors derived from the conceptual framework distributed among the participating school leaders?

- What do the well-being scores of school leaders reveal about the effects of distance schooling on their overall well-being?

- Which dispositional, relational, and contextual factors are significant predictors of school leaders’ well-being scores?

5.2. Research Design

5.3. Research Instrument

5.4. Data Collection

5.5. Sample

5.6. Data Analysis

5.7. Research Ethics

6. Results

6.1. Dispositional Factors

- Gender: Most school leaders completing the survey were women (78%), considerably higher than the OECD (2019) data (53%). Only 22% of respondents were men.

- School leadership experience: On average, respondents had about 6 years of school leadership experience (M = 6.2).

- Professional development: Most school leaders (78%) had received online specialised training for managing schools during the online/blended education setup.

- School leadership style: School leaders were surveyed on the autonomy of teachers in selecting online platforms and modifying the curriculum for distance learning. A majority (71.4%) indicated that their teachers could select preferred online tools freely. Additionally, most school leaders (75.9%) affirmed they had the flexibility to modify the curriculum. These findings suggest a school leadership style favouring teacher autonomy, aligning with a distributed school leadership framework.

6.2. Relational Factors

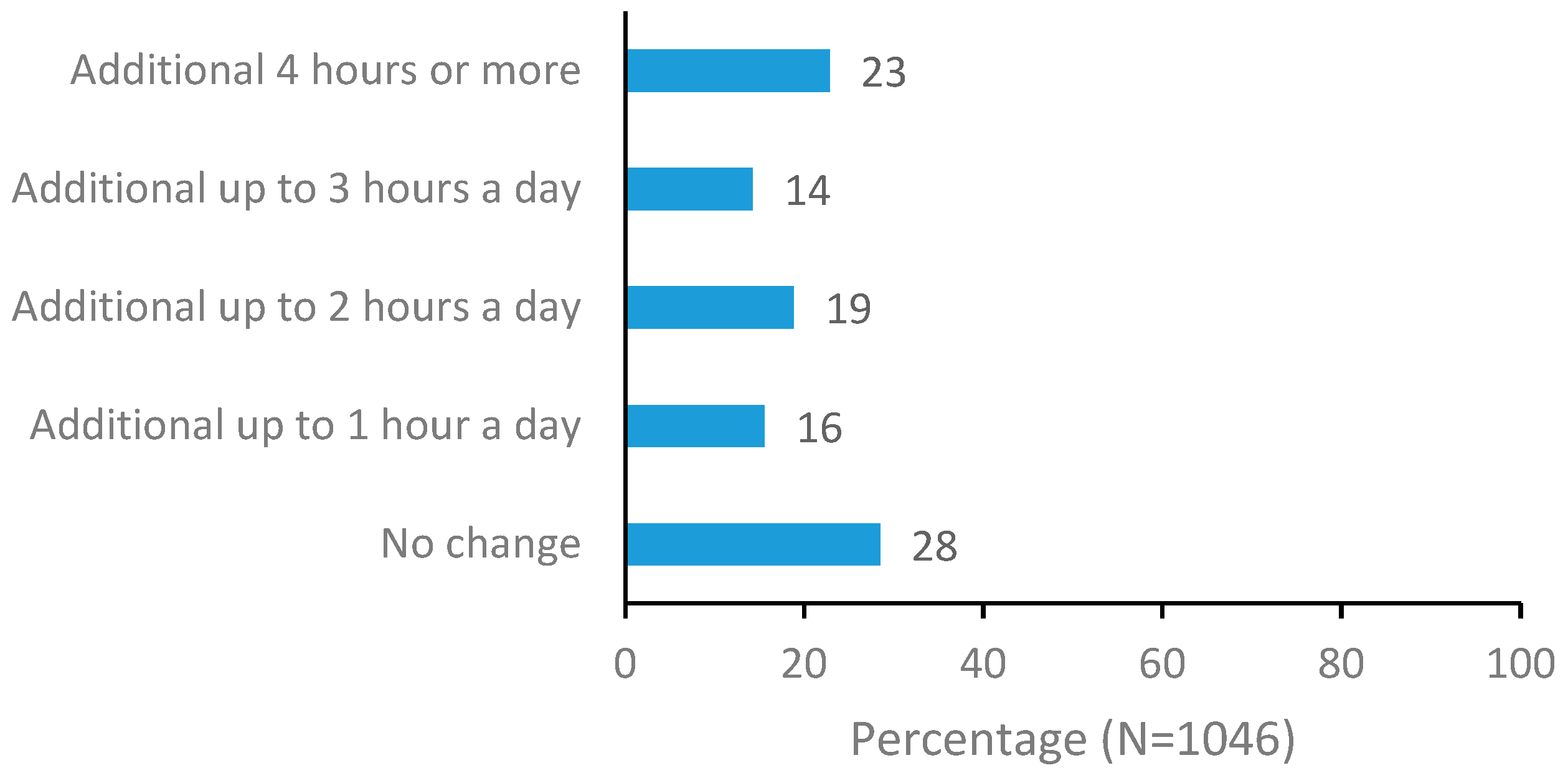

- Workload intensity: School leaders displayed parental care through regular communication, yet this heightened their workload significantly. A majority of school leaders (82%) reported an increased workload due to parental involvement compared to pre-pandemic levels, with some dedicating an extra four hours daily (23%) (Figure 2). Gender disparities were noted in the time allocated to parental engagement, with female school leaders dedicating more time than their male counterparts (Mann-Whitney U = 98,984.5, p < 0.001, z = −4.048).

- Parental complaints: Since emerging literature indicated that Kazakhstani parents expressed strong dissatisfaction with distance schooling [17,66], the surveyed school leaders were asked about parental complaints and managing challenging interactions with parents. Findings showed that 44.8% of school leaders agreed on a notable rise in parental complaints during remote schooling. Additionally, 39% of the 1020 school leaders agreed they had to handle angry parents too frequently.

- Networking with other school leaders: In the centralised Kazakhstani school sector, school leaders were queried about how restricted networking opportunities affected them. Results revealed that while 46% of the responding school leaders did not face significant networking obstacles, a notable 44% encountered minor limitations, with a minority (10%) experiencing major constraints. These challenges may have affected their capacity to engage and learn from their peers in crisis school leadership.

6.3. Contextual Factors

- School type: Public schools made up 98% of the participating schools, while selective and private schools each comprised only 1%. Due to the unequal distribution of school types, the school type variable was not used in inferential analyses.

- School location: Approximately half of the school leaders were in charge of rural schools, 41% oversaw urban schools, and the remaining 9% led semi-urban institutions, classified as locations within an hour’s drive from the city.

- Medium of instruction: Approximately 53.4% of the responding school leaders led schools using Kazakh MoI, followed by mixed MoI (26.8%) and Russian MoI (18.2%).

- School autonomy: The majority (60.2%) of school leaders indicated that their school’s autonomy or their ability to make educational decisions during the pandemic was either a minor limitation (47.8%) or a major constraint (12.4%) in effectively leading schools (Table 4).

- Digital infrastructure: The schools’ digital environment was measured by asking school leaders to indicate the extent to which different factors such as internet connectivity and access to digital devices were a school leadership challenge with three response categories: not a limitation, minor limitation and major limitation (Table 4).

- Students’ Internet connectivity: Out of 975 responding school leaders, approximately 75.7% reported that the lack of Internet access for students presented either a minor limitation (46.4%) or a major limitation (29.3%). Similarly, around 82.0% noted that students’ poor internet connectivity resulted in either a minor limitation (50.5%) or a major limitation (31.5%).

- Students’ access to digital devices: Approximately 71.0% of school leaders noted that a shortage of digital devices for students resulted in either a minor limitation (46.5%) or a major limitation (24.5%).

- Teachers’ Internet connectivity: Approximately 67.61.3% of school leaders reported that the lack of Internet access for teachers presented either a minor limitation (37.4%) or a major limitation (23.9%). Similarly, around 67.7% of school leaders noted that teachers’ poor internet connectivity resulted in either a minor limitation (42.8%) or a major limitation (24.9%).

- Teachers’ access to digital devices: Approximately 57.0% of school leaders noted that a shortage of digital devices for teachers resulted in either a minor limitation (36.3%) or a major limitation (20.7%).

- Access to digital platforms: Approximately 62.1% of school leaders stated that the absence of access to licensed e-platforms like Zoom posed either a minor limitation (44.4%) or a major limitation (17.7%).

- Widening inequality: Considering international [16] and national [17] concerns regarding the digital divide during distance schooling, school leaders were questioned about whether remote schooling had exacerbated educational inequality among schools. Nearly half (51.4%) of the surveyed school leaders affirmed that distance schooling had widened educational disparities in their schools.

6.4. School Leaders’ Well-Being Measurement

6.5. Predictors’ of School Leaders’ Well-Being

7. Discussion

7.1. Implications

7.2. Strengths and Limitations

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. School Leader Survey

- i.

- Female

- ii.

- Male

- iii.

- Other

- i.

- Mainstream school

- ii.

- Selective school (NIS, Bilim—Innovation School etc.)

- iii.

- Private school

- iv.

- Other

- i.

- Akmola Oblast

- ii.

- Aktobe Oblast

- iii.

- Almaty City

- iv.

- Almaty Oblast

- v.

- Atyrau Oblast

- vi.

- East Kazakhstan Oblast

- vii.

- Karaganda Oblast

- viii.

- Kostanay Oblast

- ix.

- Kyzylorda Oblast

- x.

- Mangystau Oblast

- xi.

- North Kazakhstan Oblast

- xii.

- Nur-Sultan City

- xiii.

- Pavlodar Oblast

- xiv.

- Shymkent City

- xv.

- South Kazakhstan Oblast

- xvi.

- West Kazakhstan Oblast

- xvii.

- Zhambyl Oblast

- i.

- Urban = In a city

- ii.

- Semi-urban = Outside a city but less than an hour by car (close to a city but not in it)

- iii.

- Rural = In a village more than an hour’s drive by car (far from a city)

- i.

- Kazakh medium

- ii.

- Russian medium

- iii.

- Mixed/both Kazakh & Russian

- iv.

- Other

- i.

- As needed

- ii.

- Once or twice a term

- iii.

- Once a month

- iv.

- Twice a month

- v.

- Weekly

- vi.

- More than once a week

- vii.

- Daily

- i.

- No change

- ii.

- Additional up to 1 h a day

- iii.

- Additional up to 2 h a day

- iv.

- Additional up to 3 h a day

- v.

- Additional 4 h or more.

| 1. Strongly disagree | 2. Disagree | 3. Agree | 4. Strongly agree | |

| ||||

| ||||

| ||||

| ||||

| ||||

|

| Not a limitation | Minor limitation | Major limitation | |

| |||

| |||

| |||

| |||

| |||

| |||

| |||

| |||

|

| 1. Strongly disagree | 2. Disagree | 3. Agree | 4. Strongly agree | |

| ||||

| ||||

| ||||

|

Appendix B

| Conceptual Framework Factors | Variable | Type of Variable | Test | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dispositional | Gender | Binary | Mann-Whitney U | p = 0.0.049 |

| School leadership experience | Continuous | Spearman Rho | p = 0.619 | |

| School leadership style 1 Autonomy in selecting plat-forms | Binary | Mann-Whitney U | p = 0.204 | |

| School leadership style 2 Freedom to modify curriculum | Binary | Mann-Whitney U | p = 0.280 | |

| Relational | School autonomy limitation | Categorical, with 3 categories | One way ANOVA | p < 0.001 |

| Workload intensity | Re-coded, bi-nary | Mann-Whitney U | p < 0.001 | |

| Parental complaints | Re-coded, bi-nary | Mann-Whitney U | p < 0.001 | |

| Working with angry parents | Re-coded, binary | Mann-Whitney U | p < 0.001 | |

| Contextual | School location | Categorical, with 3 categories | Kruskal Wallis | p = 0.235 |

| Medium of instruction | Categorical, with 3 categories | Kruskal Wallis | p = 0.057 | |

| Professional development | Re-coded, binary | Mann-Whitney U | p = 0.474 | |

| Digital infrastructure 4 teachers’ access to the internet | Categorical, with 3 categories | Kruskal Wallis | p < 0.001 | |

| Digital infrastructure 5 Teachers’ internet connectivity | Categorical, with 3 categories | Kruskal Wallis | p < 0.001 | |

| Digital infrastructure 6 Teachers’ access to digital de-vices | Categorical, with 3 categories | Kruskal Wallis | p < 0.001 | |

| Digital infrastructure 7 School access to digital platforms | Categorical, with 3 categories | Kruskal Wallis | p < 0.001 | |

| Widening inequality | Re-coded, binary | Mann-Whitney U | p < 0.001 |

References

- Gurr, D. A Think-Piece on Leadership and Education. In Paper Commissioned for the 2024/5 Global Education Monitoring Report, Leadership and Education; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2023; Available online: https://www.unesco.org/gem-report/en/leadership (accessed on 1 June 2024).

- Wang, F. Principals’ well-being: Understanding its multidimensional nature. Sch. Leadersh. Manag. 2024, 24, 442–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beauchamp, G.; Hulme, M.; Clarke, L.; Hamilton, L.; Harvey, J.A. ‘People miss people’: A study of school leadership and management in the four nations of the United Kingdom in the early stage of the COVID-19 pandemic. Educ. Manag. Adm. Leadersh. 2021, 49, 375–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schechter, C.; Da’as, R.; Qadach, M. Crisis leadership: Leading schools in a global pandemic. Manag. Educ, 2022; advance online publication. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teran, K. Crisis leadership: Experiences of K-12 Principals in South Texas School Districts during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Ph.D. Thesis, Texas A&M University Corpus Christi, Corpus Christi, TX, USA, 2013. Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/1969.6/94033 (accessed on 5 May 2024).

- Kagawa, F. Emergency education: A critical review of the field. Comp. Educ. 2005, 41, 487–503. [Google Scholar]

- Sinclair, M. Planning Education in and after Emergencies. UNESCO, International Institute for Educational Planning. Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000129356 (accessed on 1 June 2023).

- UNESCO. Evidence on the Gendered Impacts of Extended School Closures. A Systematic Review; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2022; Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000380935 (accessed on 5 June 2023).

- Durrani, N.; Makhmetova, Z.; Kadyr, Y.; Karimova, N. Leading Schools during a global crisis: Kazakhstani school leaders’ perspectives and practices. Sage Open 2024, 14, 21582440241251606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Voto, C.; Superfine, B.M. The crisis you can’t plan for: K-12 leader responses and organisational preparedness during COVID-19. Sch. Leadersh. Manag. 2023, 43, 369–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lozano-Díaz, A.; Fernández-Prados, J.S.; González-Martín, B. From crisis leadership to digital and inclusive leadership in the aftermath of the pandemic. Sch. Leadersh. Manag. 2024, 44, 373–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moulin, L.; Soncin, M. Digital instructional leadership and teaching practices in an emergency context: Evidence from Italy. Educ. Manag. Adm. Leadersh. 2024; online first. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lau, S.S.S.; Shum, E.N.Y.; Man, J.O.T.; Cheung, E.T.H.; Amoah, P.A.; Leung, A.Y.M.; Okan, O.; Dadaczynski, K. A cross-sectional study of the perceived stress, well-being and their relations with work-related behaviours among Hong Kong school leaders during the COVID-19 pandemic. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 15777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bradbury, A.; Braun, A.; Duncan, S.; Harmey, S.; Levy, R.; Moss, G. Crisis policy enactment: Primary school leaders’ responses to the Covid-19 pandemic in England. J. Educ. Policy 2023, 38, 761–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mutch, C. Leadership in times of crisis: Dispositional, relational and contextual factors influencing school principals’ actions. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2015, 14, 186–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durrani, N.; Ozawa, V. Education in emergencies: Mapping the global education research landscape in the context of the COVID-19 crisis. Sage Open 2024, 14, 21582440241233402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durrani, N.; Qanay, Q.; Mir, G.; Helmer, J.; Polat, F.; Karimova, N.; Temirbekova, A. Achieving SDG 4, equitable quality education after COVID-19: Global evidence and a case study of Kazakhstan. Sustainability 2023, 15, 14725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durrani, N.; CohenMiller, A.; Kataeva, Z.; Bekzhanova, Z.; Seitkhadyrova, A.; Badanova, A. ‘The fearful khan and the delightful beauties’: The construction of gender in secondary school textbooks in Kazakhstan. Int. J. Educ. Dev. 2022, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozawa, V.; Durrani, N.; Thibault, H. The political economy of education in Central Asia: Exploring the fault lines of social cohesion. Glob. Soc. Educ. 2024, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLaughlin, C.; Winter, L.; Yakavets, N. (Eds.) Select bibliography: School-level educational reforms in Kazakhstan, 2011–2022. In Mapping Educational Change in Kazakhstan; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2023; pp. 313–324. [Google Scholar]

- Yakavets, N. Societal culture and the changing role of school principals in the post-Soviet era: The case of Kazakhstan. Educ. Manag. Adm. Leadersh. 2016, 54, 683–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tajik, M.A.; Yesselbayev, R. Educational leadership in post-Soviet Kazakhstan: Historical evolution and reconceptualization of leadership. In Redefining Educational Leadership in Central Asia: Selected Cases from Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan, 1st ed.; Tajik, M.A., Makoelle, T.M., Eds.; Emerald Publishing Limited: Leeds, UK, 2024; Volume 1, pp. 19–35. [Google Scholar]

- Yakavets, N. Negotiating the principles and practice of school leadership: The Kazakhstan experience. Educ. Manag. Adm. Leadersh. 2017, 45, 445–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnold, B.; Rahimi, M.; Riley, P. Working through the first year of the pandemic: A snapshot of Australian school leaders’ work roles and responsibilities and health and wellbeing during COVID-19. J. Educ. Adm. Hist 2021, 53, 301–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellemans, L.; Devos, G.; Tuytens, M.; Vekeman, E. The role of self-efficacy on feelings of burnout among Flemish school principals during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Educ. Admin. 2023, 61, 567–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, E.; Hayes, S.; Carpenter, B. Principal as Caregiver of All: Responding to Needs of Others and Self. CPRE Policy Briefs. November 2020. Available online: https://repository.upenn.edu/cpre_policybriefs/92 (accessed on 4 May 2021).

- Crosslin, L.; Bailey, L.E. Mother school leaders negotiate ‘blurred lines’ between work and home during COVID-19. Plan. Chang. 2021, 50, 165–289. [Google Scholar]

- Doyle Fosco, S.L.; Brown, M.A.; Schussler, D.L. Factors affecting educational leader wellbeing: Sources of stress and self-care. Educ. Manag. Adm. Leadersh. 2023, 17411432231184601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reid, D.B. Suppressing and sharing: How school principals manage stress and anxiety during COVID-19. Sch. Leadersh. Manag. 2022, 42, 62–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, S.D.; Anderson, E.; Carpenter, B.W. Responsibility, stress and the well-being of school principals: How principals engaged in self-care during the COVID-19 Crisis. J. Educ. Adm. 2022, 60, 403–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leksy, K.; Wójciak, M.; Gawron, G.; Muster, R.; Dadaczynski, K.; and Okan, O. Work-related stress of Polish school principals during the COVID-19 pandemic as a risk factor for burnout. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchant, E.; Dowd, J.; Bray, L.; Rowlands, G.; Miles, N.; Crick, T.; James, M.; Dadaczynski, K.; Okan, O. The well-being and work-related stress of senior school leaders in Wales and Northern Ireland during COVID-19. ‘Educational leadership crisis’: A cross-sectional descriptive study. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0291278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schultz, J.J. The State of School Principals: A Quantitative Study on Principal Burnout during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Ph.D. Thesis, Cardinal Stritch University, Fox Point, WI, USA, 2023. Available online: https://www.proquest.com/dissertations-theses/state-school-principals-quantitative-study-on/docview/2819968037/se-2?accountid=134066 (accessed on 3 March 2024).

- Alexander, D.L.A. Put on Your Own Oxygen Mask First: Exploring School Principals’ Stress and Workplace Well-Being. Ph.D. Thesis, Seattle Pacific University, Seattle, WA, USA, 2023. Available online: https://digitalcommons.spu.edu/soe_etd/79/ (accessed on 3 March 2024).

- Swapp, D.H.; Osmond-Johnson, P. Approaching burnout: The work and wellbeing of Saskatchewan school administrators during COVID-19. Leadersh. Policy Sch. 2023, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fotheringham, P.; Harriott, T.; Healy, G.; Arenge, G.; Wilson, E. Pressures and influences on school leaders navigating policy development during the COVID-19 pandemic. Br. Educ. Res. J. 2022, 48, 201–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lien, C.M.; Khan, S.; Eid, J. School principals’ experiences and learning from the COVID-19 pandemic in Norway. Scand. J. Educ. Res. 2023, 67, 775–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sum, N. School leaders’ perceptions of their roles during the pandemic: An Australian Case Study Exploring Volatility, Uncertainty, Complexity and Ambiguity (VUCA leadership). Sch. Leadersh. Manag. 2022, 42, 188–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, E.; Weiner, J. Managing up, down, and outwards: Principals as boundary spanners during the COVID-19 crisis. Sch. Leadersh. Manag. 2023, 434, 411–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, A.; Jones, M. COVID-19—School leadership in disruptive times. Sch. Leadersh. Manag. 2020, 40, 243–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLeod, S.; Dulsky, D. Resilience, reorientation, and reinvention: School leadership during the early months of the COVID-19 pandemic. Front. Educ. 2021, 6, 637075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wharton-Beck, A.; Chou, C.C.; Gilbert, C.; Johnson, B.; Beck, M.A. K-12 school leadership perspectives from the COVID-19 pandemic. Policy Futures Educ. 2024, 22, 21–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heffernan, A.; Mills, M. Love, care, and solidarity: Understanding the emotional and affective labour of school leadership. Camb. J. Educ. 2023, 53, 311–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arastaman, G.; Çetinkaya, A. Stressors faced by principals: Ways of coping with stress and leadership experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic. Int. J. Educ. Manag. 2022, 367, 1271–1283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J. Conceptualising principal resilience: Development and validation of the principal resilience inventory. Educ. Manag. Adm. Leadersh. 2023, 17411432231186294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diotaiuti, P.; Mancone, S.; Bellizzi, F.; Valente, G. The principal at risk: Stress and organizing mindfulness in the school context. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 6318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Pollock, K.; Hauseman, C. Time demands and emotionally draining situations amid work intensification of school principals. Educ. Adm. Q. 2023, 59, 112–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, R.; Singh, U.G. Support mechanisms utilised by educational leaders during COVID-19: Experiences from the western Australian public education school sector. Sch. Leadersh. Manag. 2022, 42, 457–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neelakantan, M.; Kumar, A.; Alex, S.M.; Sadana, A. Steering through the pandemic: Narrative analysis of school leader experiences in India. Int. J. Leadersh. Educ 2022, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, B.; Wang, T.; Lee, M.; Childs, A. Surviving, navigating and innovating through a pandemic: A review of research on school leadership during COVID-19, 2020–2021. Inter. J. Educ. Dev. 2023, 100, 102804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longmuir, F. Leading in Lockdown: Community, communication and compassion in response to the COVID-19 crisis. Educ. Manag. Adm. Leadersh. 2023, 51, 1014–1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwatubana, S.; Molaodi, V. Leadership styles that would enable school leaders to support the wellbeing of teachers during COVID-19. Bulg. Comp. Educ. Soc. 2021, 19, 106–112. [Google Scholar]

- Fernandes, V.; Wong, W.; Noonan, M. Developing Adaptability and Agility in Leadership amidst the COVID-19 crisis: Experiences of early-career school principals. Int. J. Educ. Manag. 2023, 37, 483–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mutch, C. Crisis leadership: Evaluating our leadership approaches in the time of COVID-19. Eval. Matt.—He Take Tō Te Aromatawai, 2020; 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- General Education Schools by Ownership. Agency for Strategic Planning and Reforms of the Republic of Kazakhstan, Bureau of National Statistics. 2022. Available online: https://bala.stat.gov.kz/en/obscheobrazovatelnye-shkoly-po-tipu-mestnosti/ (accessed on 13 December 2022).

- The Number of Specialized Schools in Kazakhstan has Reached 134, Enrolling 72 Thousand Children [Qazaqstanda Mamandandirilgan Mektepterdin Sani 134-ke Jetti, Olarda 72 min Bala Oqidy]. Ministry of Education of the Republic of Kazakhstan. Available online: https://www.gov.kz/memleket/entities/edu/press/news/details/449970?lang=kk (accessed on 13 December 2022).

- General Education Schools by Area. Agency for Strategic Planning and Reforms of the Republic of Kazakhstan, Bureau of National Statistics. Available online: https://bala.stat.gov.kz/en/obscheobrazovatelnye-shkoly-po-tipu-mestnosti/ (accessed on 22 December 2022).

- Aydapkelov, N.S. Education in the Republic of Kazakhstan 2016–2020: Statistical Data; Bureau of National Statistics Agency for Strategic Planning and Reforms of the Republic of Kazakhstan: Astana, Kazakhstan, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. TALIS 2018 Results Volume I: Teachers and School Leaders as Lifelong Learners. OECD. 2019. Available online: https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/content/publication/1d0bc92a-en (accessed on 17 April 2024).

- Kasa, R.; Mhamed, A.A.S. Controlled autonomy: Experiences of principals under two school funding regimes in Kazakhstan. Int. J. Educ. Dev. 2023, 103, 102875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winter, L.; Kasa, R. Financial Autonomy of Schools in Kazakhstan: International Comparison and a National Perspective. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Education 2021 Official Conference Proceedings, London, UK, 15–18 July 2021; pp. 325–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tajik, M.A.; Shamatov, D.; Fillipova, L. Stakeholders’ perceptions of the quality of education in rural schools in Kazakhstan. Improv. Sch. 2022, 252, 187–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Number of Teachers of Secondary Schools. Agency for Strategic Planning and Reforms of the Republic of Kazakhstan, Bureau of National Statistics. Available online: https://old.stat.gov.kz/official/industry/62/statistic/8 (accessed on 30 December 2022).

- Kuzhabekova, A.; Almukhambetova, A. Female academic leadership in the post-Soviet context. Eur. Educ. Res. J. 2017, 16, 183–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bokayev, B.; Torebekova, Z.; Abdykalikova, M.; Davletbayeva, Z. Exposing policy gaps: The experience of Kazakhstan in Implementing distance learning during the COVID-19 pandemic. Transform. Gov. People Process Policy 2021, 152, 275–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bokayev, B.; Torebekova, Z.; Davletbayeva, Z.; Zhakypova, F. Distance learning in Kazakhstan: Estimating parents’ satisfaction of educational quality during the Coronavirus. Technol. Pedagog. Educ. 2021, 301, 27–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durrani, N.; Helmer, J.; Polat, F.; Qanay, G. Education, Gender and Family Relationships in the Time of COVID-19: Kazakhstani Teachers’, Parents’ and Students’ Perspectives, 2021. Partnerships for Equity and Inclusion PEI Pilot Project Report. Graduate School of Education, Nazarbayev University. Available online: https://research.nu.edu.kz/en/publications/education-gender-and-family-relationships-in-the-time-of-covid-19 (accessed on 17 April 2024).

- Cohen, L.; Manion, L.; Morrison, K. Research Methods in Education, 6th ed.; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Sue, V.M.; Ritter, L.A. Conducting Online Surveys, 1st ed.; SAGE Publications: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, J.W.; Plano Clark, V.L. Designing and Conducting Mixed Methods Research, 3rd ed.; SAGE Publications: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Behr, D.; Shishido, K. The Translation of Measurement Instruments for Cross-Cultural Surveys. In The SAGE Handbook of Survey Methodology; Wolf, C., Joye, D., Smith, T., Fu, Y., Eds.; SAGE Publications Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2016; pp. 269–287. [Google Scholar]

- Gehlbach, H.; Brinkworth, M.E. Measure Twice, Cut down Error: A Process for Enhancing the Validity of Survey Scales. Rev. Gen. Psychol. 2011, 15, 380–387. [Google Scholar]

- Pallant, J. SPSS Survival Manual: A Step by Step Guide to Data Analysis Using SPSS, 4th ed.; Allen & Unwin: Crows Nest, Australia, 2010; p. 97. [Google Scholar]

- Nurumov, K.; Hernández-Torrano, D.; Ait Si Mhamed, A.; Ospanova, U. Measuring social desirability in collectivist countries: A psychometric study in a representative sample from Kazakhstan. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 822931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Torrano, D.; Ali, S.; Chan, C.-K. First Year Medical Students’ Learning style preferences and their correlation with performance in different subjects within the medical course. BMC Med. Educ. 2017, 17, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polat, F.; Karakuş, M.; Helmer, J.; Malone, K.; Gallagher, P.; Mussabalinova, A.; Zontayeva, Z.; Mnazhatdinova, A. Factors affecting multi-stakeholders perspectives towards inclusive early childhood education (IECE) in Kazakhstan. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2023, 155, 107224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabachnick, B.G.; Fidell, L.S. Using Multivariate Statistics, 5th ed.; Allyn & Bacon/Pearson Education: Boston, MA, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Holmes Finch, W. Exploratory Factor Analysis; Quantitative Applications in the Social Sciences; SAGE Publications: Washington, DC, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Brevik, L.M. Research ethics: An investigation into why school leaders agree or refuse to participate in educational research. Probl. Educ. 21st Century 2013, 52, 7–20. Available online: https://www.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/research-ethics-investigation-into-why-school/docview/2343802710/se-2 (accessed on 20 June 2024).

- Jonbekova, D. Educational research in Central Asia: Methodological and ethical dilemmas in Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan. Compare 2020, 50, 352–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tremmel, M.; Wahl, I. Gender stereotypes in leadership: Analyzing the content and evaluation of stereotypes about typical, male, and female leaders. Front. Psychol. 2023, 14, 1034258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urick, A.; Carpenter, B.W.; Eckert, J. Confronting COVID: Crisis leadership, turbulence, and self-care. Front. Educ. 2021, 6, 642861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.J. Navigation to well-being and work-life balance for school principals: Mindfulness-based approaches. Health Behav. Policy Rev. 2022, 92, 776–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L. Examining the usefulness of mindfulness practices in managing school leader stress during COVID-19 pandemic. J. Sch. Adm. Res. Dev. 2020, 5 (Suppl. S1), 15–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Number | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Female | 1013 | 78.0 |

| Male | 286 | 22.0 |

| Leadership experience—Year of experience—M = 6.2 | ||

| Professional development | ||

| Yes | 824 | 78.0 |

| No | 233 | 22.0 |

| School leaders’ perceptions of teacher autonomy: freedom to use online tools, platform | ||

| Yes | 796 | 71.4 |

| No | 319 | 28.6 |

| School leaders’ perceptions of teacher autonomy: freedom to modify curriculum | ||

| Yes | 789 | 75.9 |

| No | 251 | 24.1 |

| Variable | Number | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Workload intensity | ||

| Yes | 828 | 70.4 |

| No | 348 | 29.6 |

| Increase in parental complaints | ||

| Yes | 469 | 44.8 |

| No | 565 | 55.2 |

| Dealing too often with angry parents | ||

| Yes | 398 | 39.0 |

| No | 622 | 61.0 |

| Networking with other schools | ||

| Not a limitation | 426 | 46.0 |

| Minor limitation | 407 | 44.0 |

| Major limitation | 93 | 10.0 |

| Variable | Number | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| School type | ||

| Public schools | 1240 | 98.0 |

| Selective schools | 15 | 1.0 |

| Private schools | 11 | 1.0 |

| School location | ||

| Urban | 521 | 41.5 |

| Semi-urban | 110 | 8.8 |

| Rural | 624 | 49.7 |

| Medium of instruction | ||

| Kazakh | 686 | 53.4 |

| Russian | 234 | 18.2 |

| Mixed/both Kazakh & Russian | 344 | 26.8 |

| Other | 21 | 1.6 |

| Variable | Number | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Lack of school autonomy | ||

| Not a limitation | 356 | 39.8 |

| Minor limitation | 427 | 47.8 |

| Major limitation | 111 | 12.4 |

| Digital infrastructure | ||

| Students’ lack of internet connectivity | ||

| Not a limitation | 237 | 24.3 |

| Minor limitation | 452 | 46.4 |

| Major limitation | 286 | 29.3 |

| Students’ poor internet connectivity | ||

| Not a limitation | 174 | 18.0 |

| Minor limitation | 488 | 50.5 |

| Major limitation | 305 | 31.5 |

| Students’ access to digital devices | ||

| Not a limitation | 277 | 29.0 |

| Minor limitation | 445 | 46.5 |

| Major limitation | 234 | 24.5 |

| Teachers’ internet connectivity | ||

| Not a limitation | 369 | 38.7 |

| Minor limitation | 356 | 37.4 |

| Major limitation | 228 | 23.9 |

| Teachers’ poor internet connectivity | ||

| Not a limitation | 308 | 32.3 |

| Minor limitation | 408 | 42.8 |

| Major limitation | 237 | 24.9 |

| Teachers’ access to digital devices | ||

| Not a limitation | 410 | 43.0 |

| Minor limitation | 346 | 36.3 |

| Major limitation | 197 | 20.7 |

| School’s access to digital platforms | ||

| Not a limitation | 351 | 37.9 |

| Minor limitation | 412 | 44.4 |

| Major limitation | 164 | 17.7 |

| Widening inequality | ||

| Yes | 522 | 51.4 |

| No | 493 | 48.6 |

| Well-Being Statements | Descriptive Statistics | h2 | Factor Score | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | |||

| 1. School closures have increased my workload. | 2.48 | 0.883 | 0.210 | 0.184 |

| 2. Ensuring my school complies with government regulations related to COVID-19 has been very stressful. | 2.50 | 0.766 | 0.293 | 0.277 |

| 3. Preparing teaching timetables simultaneously for online and offline lessons is challenging | 2.27 | 0.760 | 0.354 | 0.420 |

| 4. I get frequent headaches. | 2.53 | 0.748 | 0.273 | 0.257 |

| Total number | 672 | |||

| Total mean score | 2.44 | |||

| Eigenvalue | 2.219 | |||

| % Variance | 55.465 | |||

| KMO | 0.754 | |||

| Bartlett’s test | <0.001 | |||

| Cronbach’s Alpha | 0.726 | |||

| Conceptual Framework Factors | Predictors | Measurement Level | Coding |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dispositional | Gender | Binary category | 0 if male 1 if female |

| Relational | Increase in workload due to parental engagement | Recorded, binary | 0 if male 1 if female |

| Increase in parental complaints | |||

| Working with angry parents too often | |||

| Contextual | School autonomy limitation | Nominal with 3 categories: not a limitation minor limitation a major limitation | Not a limitation—reference |

| No internet access for teachers | |||

| Poor internet connection for teachers | |||

| Shortage of digital devices for teachers | |||

| Access to digital platforms | |||

| Widening educational inequality during remote schooling | Binary category | 0 if no 1 if yes |

| Predictors | R2 | β |

|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | 0.141 *** | |

| Gender Male (0) vs. Female (1) | −0.151 *** | |

| School autonomy Not a limitation (0) vs. Minor limitation (1) | −0.112 | |

| School autonomy Not a limitation (0) vs. Major limitation (1) | −0.186 ** | |

| Increase in parental engagement No (0) vs. Yes (1) | −0.026 | |

| Increase in parental complaints No (0) vs. Yes (1) | −0.093 | |

| Working with angry parents No (0) vs. Yes (1) | −0.141 ** | |

| Widening inequality, No (0) vs. Yes (1) | −0.068 | |

| No internet access for teachers: Not a limitation (0) vs. Minor limitation (1) | −0.071 | |

| No internet access for teachers: Not a limitation (0) vs. Major limitation (1) | −0.177 | |

| Poor internet access for teachers Not a limitation (0) vs. Minor limitation (1) | −0.016 | |

| Poor internet access for teachers Not a limitation (0) vs. Major limitation (1) | −0.118 | |

| Shortage of digital devices for teachers: Not a limitation (0) vs. Minor limitation (1) | −0.068 | |

| Shortage of digital devices for teachers: Not a limitation (0) vs. Major limitation (1) | −0.060 | |

| Access to digital platforms: Not a limitation (0) vs. Minor limitation (1) | −0.004 | |

| Access to platforms: Not a limitation (0) vs. Major limitation (1) | 0.008 | |

| Model 2 | 0.150 *** | |

| Gender Male (0) vs. Female (1) | −0.139 ** | |

| School autonomy: Not a limitation (0) vs. Minor limitation (1) | −0.125 * | |

| School autonomy: Not a limitation (0) vs. Major limitation (1) | −0.193 *** | |

| Increase in parental complaints No (0) vs. Yes (1) | −0.088 | |

| Working with angry parents No (0) vs. Yes (1) | −0.155 ** | |

| Widening inequality, No (0) vs. Yes (1) | −0.070 | |

| No internet access for teachers Not a limitation (0) vs. Major limitation (1) | −0.113 * | |

| Shortage of digital devices for teachers: Not a limitation (0) vs. Minor limitation (1) | −0.119 * |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Durrani, N.; Makhmetova, Z. School Leaders’ Well-Being during Times of Crisis: Insights from a Quantitative Study in Kazakhstan. Educ. Sci. 2024, 14, 942. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14090942

Durrani N, Makhmetova Z. School Leaders’ Well-Being during Times of Crisis: Insights from a Quantitative Study in Kazakhstan. Education Sciences. 2024; 14(9):942. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14090942

Chicago/Turabian StyleDurrani, Naureen, and Zhadyra Makhmetova. 2024. "School Leaders’ Well-Being during Times of Crisis: Insights from a Quantitative Study in Kazakhstan" Education Sciences 14, no. 9: 942. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14090942

APA StyleDurrani, N., & Makhmetova, Z. (2024). School Leaders’ Well-Being during Times of Crisis: Insights from a Quantitative Study in Kazakhstan. Education Sciences, 14(9), 942. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14090942