1. Introduction

Student dropout has been a matter of concern for educational policymakers and politicians since the establishment of formal education. Studies have succeeded in determining correlations between dropout and students’ and institutions’ background characteristics, while pedagogical factors have been less researched. Therefore, we know significantly more about the impact of “given”, “endogenous”, or simply “prior” conditions or factors such as student demographics, individual student characteristics (previous educational results, admission criteria, housing situation, etc.), and teacher experience than about the impact of factors related to educational intervention programs, policies, and practices [

1]. A recent review of research on dropouts [

2] concludes that the literature on dropouts “focuses on retention and well-being based on individual conditions, rather than institutional structures and potential teaching strategies” (p. 25, our translation). Also, Tinto [

3,

4], in his latest publications, concludes that institutional factors are both theoretically and empirically under-researched. The shortage of research on pedagogical factors is remarkable, considering that Tinto’s institutional departure model was introduced in 1975. This model introduces a correlation between dropouts and students’ institutional integration within social and academic systems, and the 1997 edition places classroom activities (classroom, labs, studios) as straddling both the social system and the academic system, suggesting that they overlap the two systems, key to improving student integration in or identification with their institution. Given its focus on institutional conditions and activities, the model was conceptualized as a counter-response to dropout models focusing solely on students’ psychological factors and individual characteristics [

5,

6], and it was suggested to indicate a change in paradigm in the field of dropout research [

7]. Today, it is still one of the most used and cited models in the field of higher education student dropout [

8]. The shortage of research on pedagogical factors is unfortunate, as the strongest basis for understanding and strengthening the quality of teaching is established when changeable factors, on which one can actually intervene [

9], are given particular awareness [

10,

11]. The reason for the shortage of research on the correlation between dropout and pedagogical factors is most likely manifold, but we consider two reasons to be dominant. Firstly, to avoid recall bias rooted in participants’ lack of ability to recall their experiences of the social environment over long periods of time [

12], it is necessary to collect data on students’ experiences of the study environment longitudinally and wait until a sufficient number of students have dropped out to have enough data to carry out solid analyses of the correlation between pedagogical factors and actual dropout. This is a demanding and time-consuming research strategy, and, therefore, considerations regarding or intentions to drop out are often used as an early alert proxy for dropout [

13,

14], without us knowing if it is actually a good proxy. Secondly, it is suggested that pedagogical factors are often theoretically well-described but not clearly identifiable empirically [

15], and it has been difficult to reliably identify specific factors with a reasonable effect size [

10,

16,

17]. Due to the cruciality of these factors in the opportunity to strengthen the quality of teaching, a number of studies have sought to understand the reason why it is difficult to determine changeable factors [

15]. Scheerens [

11] and Muijs and Brookman [

18] point to the lack of instruments as a weakness. Based on a review of 645 studies, Cheung and Slavin conclude that “researcher-made tests are associated with much higher effect sizes than are standardized tests” (p.286, [

19], page 286). Scheerens suggests that this may be caused by the fact that changeable factors vary among educational institutions, study programs, subjects, and educational levels or different terms, as they are malleable with reference to context and time [

11]. Due to the malleability of these factors, Scheerens further suggests that “research-made instruments ‘are’ more tailored for the treated group” (p.253, [

11], page 523). This is substantiated in other reviews and studies that find considerable differences in the effect sizes when using nonstandard as opposed to standardized tests [

20,

21,

22,

23]. In a previous study, we found that empirically identifiable study environment factors differ widely across Nordic countries [

24] and we also find that they differ across two faculties—humanities and natural sciences—at the same university, but no studies to date have examined the malleability of study environments’ factors over time, within a faculty.

In this article, we present a research instrument and a research methodology developed to determine study environment factors (changeable factors) in higher education with regards to their malleability. Furthermore, we investigate the malleability of study environment factors over time in humanities study programs and whether study environment factors explain tertiary humanities students’ dropout better than their known background parameters and dropout considerations. Our research questions are the following:

To what extent are humanistic higher education study environment factors malleable across different terms?

Can study environment factors, students’ background parameters, or their dropout considerations best explain dropout from tertiary humanities education across different terms?

Based on our previous studies referenced above, it is our hypothesis that the study environment factors are malleable across different terms. Furthermore, based on the studies referenced above, it is our hypothesis that study environment factors, students’ background parameters, and their dropout considerations all explain dropout. As we have a particular interest in factors which we can intervene on, we will focus on which study environment factors explain persistence at different times during the course of study and on opportunities to support students’ persistence. Thus, we can add the following two research questions to the ones above:

Which study environment factors explain students’ dropout across different terms?

With a focus on the study environment, how is it possible to support student persistence?

The article is based on data from the project “Data-driven Quality Development and Dropout Minimization”. In this project, longitudinal survey and register data from all students of humanities at the University of Southern Denmark, matriculating in 2017–2019, were collected half-yearly until they were no longer enrolled (i.e., until 2020–2022, when the students had either graduated or dropped out).

2. Tinto’s Institutional Departure Model and Study Environment Factors

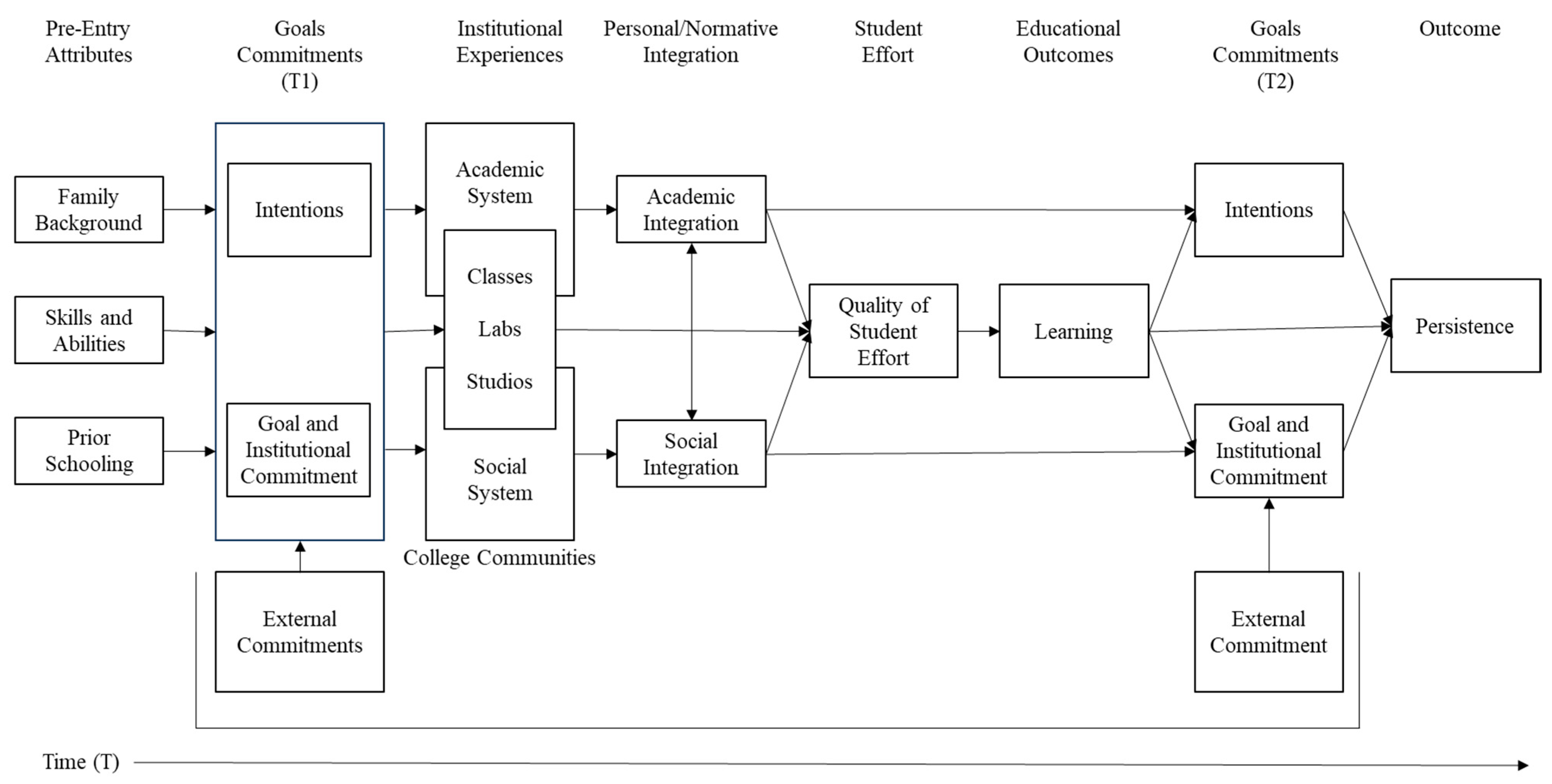

Tinto’s institutional departure model describes dropout as a longitudinal process of interactions between the individual (including background variables such as skills and abilities, family background, and prior schooling), an academic system with subcategories such as interactions with personnel and academic achievements, and a social system with subcategories such as extracurricular activities and interactions with fellow students of the institution. The systems continually modify the student’s academic and social integration, leading either to persistence (the choice to continue studying) or departure (the choice to drop out). This focus and the variables intentions and goal commitment, which, in the model, are proposed to mediate between the institutional meeting and persistence/departure, leave space for individuality and for dropout to be understood as the student’s active decision, being procedurally influenced by their attitude towards persistence and dropout (often operationalized as dropout considerations) [

25]. This focus on attitudes and decisions is different from other often-referenced dropout theories such as, for instance, Astin’s Student Involvement Theory, where student persistence is described as also involving actions: “the quantity and quality of the physical and psychological energy that students invest in the college experience” ([

26] p. 307).

The 1997 model places classroom activities (classroom, labs, studios) as straddling both the social system and the academic system, suggesting that they overlap the two systems and are key to improving student integration or identification (see

Figure 1). This article focuses on humanities study programs that do not involve activities in labs nor, for many, in studios. In order to have a term which could still signal our wish to direct our attention towards a wide range of activities (not only traditional classes), we chose the term “Teaching” as a category that included both classes and other activities such as reading groups, lectures, exercises, etc.

The project’s operationalization of the social system, the academic system, and teaching builds on a literature review of international articles on institutional factors and dropout in higher education based on a phenomenological review approach intending to identify all possible study environment factors that could have an impact on higher education dropout [

8]. The literature review identified sixty-five studies, which, together, made it possible to specify twenty-nine study environment factors associated with dropout. These factors were categorized according to whether they belonged to the academic system, the social system, or teaching. This categorization led to a specification of the academic system into eight categories, a specification of the social system into another eight categories, and a specification of teaching into thirteen categories, as shown in

Table 1.

5. Results

With respect to the research questions presented in the Introduction, we will first present the results of the exploratory factor analysis, which was used to investigate the malleability across terms and, thus, answer research question one, after which we will present the results of the binary logistic regression analysis, which we used to model the relationship between dropout and background parameters and the factors identified in the factor analysis, thus answering research questions two and three. We will address research question four in the Discussion.

5.1. Empirical Factors’ Malleability across Terms

The factors identified for each term based on the exploratory factor analyses are presented in

Table 3,

Table 4 and

Table 5 and compared with the dimensions identified from the literature review (

Table 1). As illustrated in the tables, there are noticeable differences between the theoretical categories and the empirically identified factors, while the empirical factors are relatively stable over time.

Table 3.

Theoretical categories (rows) together with the empirical factors (columns) for the social system domain during terms 1–4. Loadings above 0.3 are marked with blue. Factors with poor reliability (Cronbach’s alpha < 0.6) are marked in gray and will not be included in a further analysis.

Table 3.

Theoretical categories (rows) together with the empirical factors (columns) for the social system domain during terms 1–4. Loadings above 0.3 are marked with blue. Factors with poor reliability (Cronbach’s alpha < 0.6) are marked in gray and will not be included in a further analysis.

| Social system |

|---|

| Initial factor | Item | Empirical factors (1st term) | Empirical factors (2nd term) | Empirical factors (3rd term) | Empirical factors (4th term) |

| Experienced social relations with fellow students | Expected social relations with fellow students | Social relations with teachers | Extracurricular activities (communities) | Extracurricular activities (internship and study-relevant job) | Institutional integrity | Experienced participation in activities | Experienced social relations with fellow students | Expected social relations with fellow students | Social relations with teachers | Extracurricular activities (communities) | Extracurricular activities (internship and study-relevant job) | Institutional integrity | Experienced level of social activity | Experienced participation in activities | Experienced social relations with fellow students | Expected social relations with fellow students | Extracurricular activities (communities) | Extracurricular activities (internship and study-relevant job) | Institutional integrity | Experienced level of social activity | Experienced participation in activities | Experienced social relations with fellow students | Expected social relations with fellow students | Extracurricular activities (communities) | Extracurricular activities (internship and study-relevant job) | Institutional integrity | Experienced level of social activity | Experienced participation in activities |

| Social integration | 1 | I feel lonely in my study program | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| 2 | I have a good relationship with my fellow students | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| 3 | I feel like part of a community in my study program | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| 4 | I continue to study in this study program because we have a good sense of community in my class | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| 5 | The level of social activity is high | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| 6 | My relationship with my fellow students is close | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| 7 | I participate in academic activities | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| 8 | I participate in social activities orgnaized by either the university or my class | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| 9 | I expected the level of social activity to be high | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| 10 | I expected the relationship with my fellow students to be close | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| 11 | I expected the relationship with my lecturers to be close | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| 12 | My relationship with my lecturers is close | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| Extracurricular activities | 13 | Participation in social study organizations | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| 14 | Participation in academic communities | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| 15 | Do academic work (paid or unpaid) as a mentor/study advisor, teaching assistant or student employee | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| 16 | Go on exchange as a part of study program | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| 17 | Do an internship as a part of study program | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| 18 | Have a student job within a field where gradueates with the same education often find employment | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| Institutional integrity | 19 | The university lives up to my expectations | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| 20 | My study program lives up to my expectations | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| 21 | The classes lives up to my perception of the values of the university | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| 22 | The classes lives up to my perception of the values of my study program | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| 23 | My personal values are well alligned with my perception of the values of the university | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| 24 | My personal values are well alligned with my perception of the values of my study program | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| Social infrastructure | 25 | The other students participate in academic activities | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| 26 | The other students participate in social activities organized by either the university of my class | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| 27 | There is a satisfactory selection of social activities at the university | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| 28 | It has been easy to interact with people from different academic years | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| Cronbach’s alpha | 0.884 | 0.753 | 0.422 | 0.753 | 0.601 | 0.915 | 0.641 | 0.898 | 0.741 | - | 0.771 | 0.531 | 0.906 | 0.659 | 0.713 | 0.876 | 0.723 | 0.752 | 0.491 | 0.915 | 0.748 | - | 0.803 | 0.619 | 0.764 | 0.547 | 0.904 | 0.709 | 0.182 |

As illustrated in

Table 3, we identified seven empirical factors in the social system. The social integration category was quite stable across terms; however, it split into the following parts: experienced integration and relations with fellow students; expected social relations with fellow students; and, finally (although not reliable), relations with teachers. As such, we named the factor to capture these characteristics. The theoretical category extracurricular activities split into two factors across all terms: extracurricular activities related to study environment communities and internship and study-relevant jobs. In terms two and four, the last factor included an item on traveling abroad. The factor on internship and study-relevant jobs was, however, only reliable during the first term. The institutional integrity factor was stable and aligned with the theoretical category across all terms. Finally, the social infrastructure category split into two empirical factors: fellow students’ participation in activities and the range of activities that are offered, i.e., an institutional perspective.

Table 4.

Theoretical categories together (rows) with the empirical factors (columns) for the academic system domain during terms 1–4. Loadings above 0.3 are marked in blue. Factors with poor reliability (Cronbach’s alpha < 0.6) are marked in gray and will not be included in a further analysis.

Table 4.

Theoretical categories together (rows) with the empirical factors (columns) for the academic system domain during terms 1–4. Loadings above 0.3 are marked in blue. Factors with poor reliability (Cronbach’s alpha < 0.6) are marked in gray and will not be included in a further analysis.

| Initial factor | Item | Empirical factors (1st term) | Empirical factors (2nd term) | Empirical factors (3rd term) | Empirical factors (4th term) |

| Academic integration and identification | Perception of learning community | Support from faculty | Lecturer availability | Workload | Prior exam results, experiences and dissapointments | Academic integration and identification | Perception of learning community | Support from faculty | Lecturer availability | Workload | Prior exam results, experiences and dissapointments | Academic integration and identification | Perception of learning community | Support from faculty | Lecturer availability | Workload | Prior exam results, experiences and dissapointments | Academic integration and identification | Perception of learning community | Support from faculty | Lecturer availability | Workload | Prior exam results, experiences and dissapointments |

| Academic integration and identification | 29 | I like being a student | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| 30 | My study is an essential part of my life | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| 31 | My study is a significant part of who I am | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| 32 | It is important to me to learn as much as possible in my courses | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| 33 | Experiences of interesting academic content of study program | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| Perception of learning community | 34 | I seek help from my fellow students if I experience challenges in my studies | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| 35 | I share notes/literature/ideas for assignments with my fellow students | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| 36 | My fellow studetns share notes/literature/ideas for assignments with me | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| 37 | Our lecturers have introduced us to ways to work well in a group, e.g., how you allign your expectations, handle potential conflict, etc. | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| Relation to and interaction with and support from faculty | 38 | I have worked with a lecturer or another employee at the university for example on an article, as a student assistant, on a board etc. | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| 39 | I have discussed study relate topics, ideas or academic terms with a lecturer or another employee at the university outside of class | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| 40 | I have discussed my academic abilities with a lecturer or another employee at the university outside of class | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| 41 | At my campus you often see the lecturers outside of the classroom (for instance in hallways and common areas) | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| 42 | Most lecturers are easy to get in contact with | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| 43 | The lecturers that I have had contact with generally seem interested in the students | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| 44 | I have reached out to a study counsellor, or study secretary, a mentor, the leagal department or another employee at the university to discuss something concerning my studies | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| Workload | 45 | Experiences of work load of study program | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| 46 | How many hours a week do you spend doing exercises that the lecturer has asked you to solve before class? (e.g., work-questions for texts, small problems, bloags, wikis, etc.) | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| 47 | How many hours a week do you spend preparing for class and/or post-processing lectures? (alone or in groups) | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| Prior exam results, experiences and dissapointments | 48 | If I experience disappointment in exams I am good at shaking it off | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| 49 | My exams have gone as I expected | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| 50 | I have felt disappointment or a sense of failure in exams | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| Cronbach’s alpha | 0.784 | 0.849 | 0.772 | 0.733 | 0.466 | 0.515 | 0.764 | 0.855 | 0.725 | 0.757 | 0.498 | 0.562 | 0.766 | 0.851 | 0.707 | 0.717 | 0.515 | 0.546 | 0.761 | 0.860 | 0.695 | 0.756 | 0.397 | 0.527 |

As shown in

Table 4, we identifyed six empirical factors referring to Tinto’s academic system domain. These factors were very close to the theoretically assumed factors; however, one theoretical factor—relation to, interaction with, and support from faculty—split into two factors. Thus, we obtained a factor regarding students’ feeling of identification with being a student and wanting to learn the academic content (academic integration and identification), a factor for their perception of the learning community, and two factors for collaboration with and support from faculty and lecturer availability. Finally, we obtained a factor each for the workload and prior results and experiences of and disappointment in exams; these factors were, however, not reliable.

Table 5.

Theoretical categories together with the empirical factors for the teaching domain during terms 1–4. Loadings above 0.3 are marked with blue. Factors with poor reliability (Cronbach’s alpha < 0.6) are marked with gray text and will not be included in a further analysis.

Table 5.

Theoretical categories together with the empirical factors for the teaching domain during terms 1–4. Loadings above 0.3 are marked with blue. Factors with poor reliability (Cronbach’s alpha < 0.6) are marked with gray text and will not be included in a further analysis.

| Initial factor | Item | Empirical factors (1st term) | Empirical factors (2nd term) | Empirical factors (3rd term) | Empirical factors (4th term) |

| Experienced teaching quality | Study groups | Alignment | Exam clearity | Support between classes | Instructional clarity | Feedback (quantitative) | Feedback (qualitative) | Active learning | Higher order thinking | Cooperative learning | Introductory courses (reading) | Percieved lack of study skill knowledge | Student research programs | Participation | Percieved teacher differences | Experienced teaching quality | Study groups | Alignment | Recommended reading materials | Support between classes | Instructional clarity | Feedback (quantitative) | Feedback (qualitative) | Feedback (satisfaction) | Active learning | Higher order thinking | Cooperative learning | Introductory courses (reading) | Percieved lack of study skill knowledge | Participation | Percieved teacher differences | Alignment | Study groups | Recommended reading materials | Support between classes | Instructional clarity | Feedback (quantitative) | Feedback (qualitative) | Feedback (satisfaction) | Active learning | Higher order thinking | Cooperative learning | Introductory courses (reading) | Percieved lack of study skill knowledge | Student researcher program | Perception of difficulties | Participation | Percieved teacher differences | Study groups | Alignment | Recommended reading materials | Support between classes | Instructional clarity | Feedback (quantitative) | Feedback (qualitative) | Feedback (satisfaction) | Active learning | Higher order thinking | Cooperative learning | Introductory courses (reading) | Percieved lack of study skill knowledge | Student researcher program | Perception of difficulties | Debates | Participation | Percieved teacher differences |

| Teaching quality | 51 | Experiences of good teaching methods of study program | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| 52 | All in all I’m satisfied with the quality of teaching in my study program | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| 53 | There is a big difference in the quality of teaching I recieve | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| Study groups | 54 | I am a part of a study group or have a study buddy that I meet up with regularly throughout the semester | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| 55 | I am a part of a study group or have a study buddy that I meet up with in the exam periods | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| Alignment in the teaching | 56 | I am aware of what I am supposed to learn in the different courses | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| 57 | I see the connection between the things we do in class and what I am supposed to learn | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| 58 | I see the connection between the things we’re are asked to do outside of class and what I’m supposed to learn | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| 59 | My lecturers are clear in their explanation of what is expected in exams | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | 0.764 | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| 60 | The continuity in my study program as a whole is clear to me | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| 61 | The academic progression in my study program as a whole is clear to me | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| 62 | I see the connection between the teaching methods and activities in my studies, and what we’re being assessed on in the exams | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| 63 | My lecturers support my work between classes by assigning reading materials | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| 64 | My lecturers support my work between classes by recomending further reading materials | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| 65 | My lecturers support my work between classes by providing questions for reading materials | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| 66 | My lecturers support my work between classes by giving obligatory assignments (online, individual or for study groups) | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| 67 | My lecturers do not ask us to do work between classes | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| 68 | There is a big difference between my lecturers regarding how they support my work between classes | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| Instructional clarity | 69 | My lectures are good at explaining the material so that I understand it | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| 70 | The lectures’ instructions for group work and homework assignments are clear | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| 71 | My lectures ofthen use examples to explain the material | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| 72 | When the lecturers go through new material in class they often connect it to materials we have learned in other courses | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| 73 | There is a big difference between my lecturers in regard to how clear they are, and how often they use examples and/or connect new material to things we’ve learned in other courses | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| Feedback | 74 | How often do you written reviece feedback from your lecturer (for instance on assignments)? | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| 75 | How often do you recieve oral feedback in class (from both lectureres and fellow students)? | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| 76 | How often do you recieve oral feedback in the form of an individual conversation with a lecturer? | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| 77 | How often do you engage in group conversations where you get feedback from your lecturer | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| 78 | How often do you engage in group conversations where you get feedback from your fellow students (peer feedback)? | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| 79 | The feedback I receive on my assignmetns makes it clear what I haven’t quite understood | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| 80 | The feedback I receive on my academic work during the semester improves the way in which I learn and work | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| 81 | I receive sufficient feedback on my academic work during the semester | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| 82 | There are good opportunities to receive feedback on my performance in exams | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| 83 | There is a big difference between my lecturers in regard to how much feedcback I receive in ther courses | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| Active learning | 84 | I have thought about questions I would like answered when I arrive to class | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| 85 | I always come to class prepared | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| 86 | I try to academically defend my thoughts and ideas either in class, with my study group or with otherstudents/friends/family | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| 87 | I participate actively in class | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| 88 | After class I reflect on the content we have worked with | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| 89 | After a class i revisit the revisit the readings or my notes on them | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| Higher order thinking | 90 | My current study program has provided me with abilities to write academically, clearly and precisely | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| 91 | My current study program has provided me with abilities to converse academically, clearly and precisesly | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| 92 | My current study program has provided me with abilities to being able to think critically | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| 93 | My current study program has provided me with abilities to being able to think analytically | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| 94 | My current study program has provided me with abilities to being able to analyze numeric and statistical information | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| 95 | My current study program has provided me with abilities to being able to collaborate | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| Cooperative learning | 96 | My lecturers often use quizzex, clickers, etc. in class | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| 97 | My lecturers often use mind maps, brainstorms, etc. in class | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| 98 | We regularly work on developing our knowledge and ideas through wikis, discussion boards, etc. | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| Courses on study technique and introductory courses | 99 | I have been taught how to point out the main arguments of a text | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| 100 | I have been how to deduce the implicit assumptions in the texts I read | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| 101 | I have been taught how to critically evaluate the arguments and conclusions of a text | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| 102 | I lack knowledge about text reading | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| 103 | I have been taught study techniques/study planning as a part of my study | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| 104 | I have sougth out courses on study techniques/study planning myself | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| 105 | I lack knowledge about study techniques/study planning | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| Student research programms | 106 | We/I have done research-like activities as a part of our/my class work | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| 107 | We/I have done research together with a reseacher at the university | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| Percep-tion of diffi-culty | 108 | Experiences of academic level of study program | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| 109 | It is my experience that I meet the academic expectations in my study | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| Coherence | 110 | I find it easy to connect what I’m learning to what I already know | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| Participation in class | 111 | My lecturers facilitate discussions/debates either with the entire class or in smaller groups | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| 112 | My lecturers involve the students in the teaching through student presentations | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| 113 | My lectruers make us work with the academic content thgrouhg cas- and problem-based teaching | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| 114 | There is a big difference between my lecturers in regard to how active a role they give the students in class | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| Cronbach’s alpha | 0.610 | 0.851 | 0.885 | - | 0.524 | 0.797 | 0.742 | 0.766 | 0.791 | 0.828 | 0.754 | 0.881 | 0.448 | 0.638 | 0.663 | 0.694 | 0.652 | 0.857 | 0.879 | 0.537 | 0.575 | 0.769 | 0.756 | 0.833 | 0.686 | 0.686 | 0.826 | 0.758 | 0.863 | 0.540 | 0.682 | 0.709 | 0.895 | 0.883 | 0.535 | 0.609 | 0.780 | 0.768 | 0.835 | 0.671 | 0.785 | 0.840 | 0.754 | 0.868 | 0.599 | 0.583 | - | 0.645 | 0.693 | 0.861 | 0.883 | 0.522 | 0.665 | 0.804 | 0.734 | 0.887 | 0.662 | 0.781 | 0.834 | 0.705 | 0.881 | 0.459 | 0.490 | - | - | 0.724 | 0.686 |

Finally, as illustrated in

Table 5, we identified 18 factors within Tinto’s system of teaching. Similarly to the academic systems, the empirically identified factors were very similar to the initial theoretical categories; however, three categories (alignment in the teaching, feedback, and courses on study technique and introductory courses) split into two or more factors. Overall, there was one factor regarding the students’ experience of the teaching quality and the academic level of their education and one on their participation in study groups. Furthermore, there was one factor on alignment (whether the study program was clear and whether the students were aware of what they were supposed to learn and see a connection between the things they were asked to carry out and needed to learn or not), one on exam clarity (if what was expected in exams was clear), one on support for the work they have to complete between classes, and one on instructional clarity, that is, whether the lecturers explained the material and group work well. There were three factors on feedback: one on the frequency of feedback, one on the perceived quality of feedback, and one on students’ satisfaction with the feedback offered. Looking at the activities during the students’ study program that helped develop their knowledge, we identified five empirical factors. There was one factor on active learning, covering how the students prepared for their classes (for instance, whether they had thought about questions that they wanted to have answered), how they participated, and how they post-processed the teaching content after the lectures, one on higher-order thinking (if the study program had provided the students with the ability to write and converse academically, think analytically and critically, and collaborate), one on cooperative learning, that is, whether the students worked on developing their knowledge and ideas using quizzes, clickers, mind maps, brainstorming, wikis, and discussion boards in class, and on the lecturers’ facilitation of discussions/debates, presentations, and case- and problem-based teaching. Finally, there was one on study technique courses on how to read texts. Related to these, we identified a self-evaluating factor concerning the perceived level of expertise regarding study skills. Finally, we referenced Tinto’s teaching system to identify one empirical factor on student research programs, concerning whether the students had participated in research activities or research-like activities as part of their class work. Last, but not least, we identified a factor that was not part of the theoretical categories: perceived teacher differences. This factor emerged from items spread out through the survey, addressing quite different topics (teaching quality, support of work between classes, clarity, feedback, and how active a role students play during class), all of them having perceived teacher differences in common. These items (53, 68, 73, 83, and 114) where the ones added as part of the qualitative pilot study, where students expressed a need to indicate that their teachers and their teaching methods were quite different. As described in the Introduction, in previous publications, we found that empirically identifiable study environment factors differed widely across Nordic countries and Danish university faculties. With regard to temporal variation—i.e., whether the factors vary within a faculty across different terms—as we examine in this article, the picture is different. Altogether

Table 3,

Table 4 and

Table 5 make it clear that the study environment factors are quite stable across terms. Thus, while the previous analyses focused on different country and faculty contexts confirmed the suggestion by Scheerens that pedagogical factors are malleable and vary across contexts [

11], interestingly, we cannot, on basis of the analyses in this article, confirm that this is also the case across time.

5.2. Factors Determining Dropout

Table 6 illustrates the binary logistic regression models between drop out and dropout considerations, background parameters, and the study environment factors identified in the factor analysis.

Table 6.

Binary regression models for each term, model fit data, and odds ratios for individual predictors of dropout (p < 0.05) with a 95% confidence interval.

Table 6.

Binary regression models for each term, model fit data, and odds ratios for individual predictors of dropout (p < 0.05) with a 95% confidence interval.

| Model Inputs | Model Fit Data | Independent Variables |

|---|

| Omnibus Tests (<0.05) | Hosmer and Lemeshow Test (>0.05) | Nagelkerke R2 | Significant Factors | Odds Ratio (CI: 95%) | Sig. (<0.05) |

|---|

| 1st term | Dropout considerations | <0.001 | 0.713 | 9.1% | Dropout considerations | 0.523 | <0.001 |

| Background parameters | 0.834 | 0.970 | 13.1% | Campus is in the same municipality as respondents’ hometown (1st term) | 0.372 | 0.004 |

| Study environment factors | 0.003 | 0.441 | 15.8% | Academic integration and identification (A) | 0.407 | 0.002 |

| Introductory courses (reading) (T) | 1.913 | 0.007 |

| 2nd term | Dropout considerations | <0.001 | 0.800 | 8.8% | Campus is in the same municipality as respondents’ hometown (1st term) | 0.583 | <0.001 |

| Background parameters | 0.328 | 0.214 | 8.2% | |

| Study environment factors | 0.005 | 0.491 | 15.8% | Experienced social relations with fellow students (S) | 0.406 | 0.000 |

| Expected social relations with fellow students (S) | 1.892 | 0.016 |

| Experienced participation in activities (S) | 1.564 | 0.048 |

| Participation (T) | 0.629 | 0.046 |

| 3rd term | Dropout considerations | 0.462 | 0.567 | 0.9% | |

| Background parameters | <0.001 | 0.588 | 21.4% | Identified gender = Male | 0.488 | 0.008 |

| Number of gap years | 0.785 | 0.017 |

| Study environment factors | 0.084 | 0.226 | 54.2% | Participation (T) | 0.022 | 0.030 |

| 4th term | Dropout considerations | 0.762 | 0.442 | 0.0% | |

| Background parameters | 0.987 | 0.596 | 7.9% | Upper secondary program = The Higher General Examination Program (stx) | 2.672 | 0.027 |

| Study environment factors | <0.001 | 0.633 | 36.9% | Support from faculty (A) | 1.744 | 0.015 |

| Feedback (satisfaction) (T) | 0.371 | 0.001 |

| Active learning (T) | 1.888 | 0.005 |

Students’ dropout considerations were significant (Omnibus tests sig. < 0.05) in the first and second terms and explained 9.1% and 8.1% of dropouts, respectively. Dropout considerations are, thus, not a particularly good indicator for actual dropout.

Students’ background parameters explained between 7.9 and 21.4% of dropouts; however, this was only significant (Omnibus tests sig. < 0.05) in the third term (explaining 21.4%). Here, the significant background factors (Odds ratio, sig. < 0.05) preventing dropout were the following: (1) being a male and (2) having several gap years before entering tertiary education.

Looking at the study environment factors, the regression models were significant (Omnibus tests, sig. < 0.05) in three out of four terms and included variables from all three systems: the academic system (A), the social system (S), and teaching (T). In the first term, study environment factors explained 15.8% of dropouts and were, thus, better predictors than dropout considerations and background parameters. We found, in the first term, the factor “academic integration and identification” from the academic system and the factor “introductory courses (reading)” from the teaching system. In the second term, factors from the social system dominated the model. We had three factors from this system—"social relations with teachers”, “experienced participation in activities”, and “experienced level of social activity”—and one factor (“participation”) from the teaching system explaining 15.8% of dropouts. In the third term, when the background parameters explained 21.4% of dropouts, the study environment was not a significant predictor of dropouts (Omnibus test, sig. > 0.05). The share of dropouts explained by the study environment factors increased significantly in the fourth term, where one factor from the academic system “support from faculty” and two factors from the teaching system (“feedback (satisfaction)” and “active learning”) explained 36.9% of dropouts.

6. Discussion

In this article, we first set out to investigate to what extent study environment factors were malleable across different terms. In our investigation, we considered four factor structures, identified in the exploratory factor analyses. We found that only few of the empirical structures resulted in the structure anticipated by the theoretical categories, but that the empirically identified factors were relatively stable across terms. In the Introduction, we formulated the hypothesis that the study environment factors would be malleable across different terms. Our analyses confirm that the study environment factors were malleable, but not across terms. Thus, this hypothesis was not confirmed. Although the idea of pedagogical factors’ malleability is well-described in epistemological theories on education and teaching [

15], the empirical contributions on this topic are very scarce. In these epistemological theories, it is suggested that the malleability is due to a variety of empirical conditions, including both traditions and understandings of schooling sedimented in different school systems [

30] and students’ conceptions or beliefs [

31]. We could not conclude anything about the exact origin of the malleability of the study environment factors in our study. We had only one country and one faculty represented in this study, but, based on our previous studies on malleability across Nordic countries and university faculties (cf. Introduction), there is reason to assume that it would look different in other contexts. Meanwhile, students have been predicted to play an important role in the formation of study environment factors [

32,

33,

34,

35]. We examined the same students over time, despite large variations in the response rates, and the stability in the empirically identified factors across the terms could indicate that what were recognized as study environment factors remained fairly stable within the same group of students (here, Danish humanities students).

In addition to investigating the malleability of the study environment factors, the article set out to investigate whether study environment factors, students’ background parameters, or their dropout considerations best explain dropout from tertiary humanities education during different terms and which study environment factors explained students’ dropout over different terms. Our study confirmed our hypothesis that study environment factors, students’ background parameters, and dropout considerations all explain dropout. It is, however, interesting that the study environment factors were the best explanations for dropout in the first term, second term, and fourth term. Thus, across the terms, the environment factors were the best predictors of dropout. However, it is interesting that the factors that explained dropout varied significantly over time. In the first term, “academic integration and identification” and “introductory courses (reading)” explained dropout, while, in the second term, these were “social relations with teachers”, “experienced participation in activities”, “experienced level of social activity”, and “participation”. In the fourth term, the factors were “support from faculty”, “feedback (satisfaction)”, and “active learning”. This indicated a maturation as the students progressed through their studies: e.g., looking at significant study environment factors, there was a revolution from study skills to participation in classes and active learning. This maturation in educational contexts is essential as a criterion for talking about what educational quality is. It has been previously discussed whether students’ perceptions of educational quality might be biased [

36], but, based on an empirical review, Follman [

37] concluded that students’ perceptions of the study environment are valid indicators of quality. Thus, it seems reasonable to think of the total number of factors as a framework for study environment quality and take their variations over time into account when working on strengthening the quality of the study environment.

The discussion on the study environment’s quality leads us to the article’s fourth and final research question: namely, how can student persistence be supported. As described in the Introduction, the lack of opportunity to take malleability into account in effect studies is described as a major reason for the lack of progression in studies of teaching quality, and this article’s focus on the study environment is justified by a desire to focus on the so-called “changeable” [

9] factors such as intervention programs, policies, and practices hypothesized (or believed) to enhance educational performance [

11], which can be intervened on and are, therefore, the strongest basis for strengthening the quality of education [

10] and, thus, hopefully retaining students in humanities programs. When it comes to the question of what can, therefore, be implemented to strengthen the quality of the study environment at different times during the students’ educational trajectory, it is interesting that the regression models include variables from all three systems—the academic system, the social system, and teaching—changing so that the academic and teaching factors dominate the first-term model, the social factors dominate the second-term model, and the teaching factors dominate the fourth-term factor. In the first semester, it is crucial that the students feel academically integrated and able to identify with the academic characteristics of their education, while, in the second semester, social aspects are important. Perhaps, it could be the case that the students first must find out whether they have chosen the right education context academically and only then they have capacity to focus and reflect on social relations and activities. In the third term, background parameters (gap years before entering tertiary education and being male) were the only factors identified that explained dropout. Perhaps, this might be because the third semester is a difficult semester, due to the first phase, when everything is new and exciting, being over and this third one being, instead, a transition phase before the end phase, during which students are close to finishing their journey. Such a transition phase requires persistence and resilience, and it is crucially important for students to believe in themselves when dealing with this phase. It is also well documented that male students have higher degrees of academic self-efficacy than female students [

38] and that academic self-efficacy varies with age [

39]. In our sample, we recorded 28,7% of respondents identifying as male students and 71.4% as female students (see

Appendix E). This is interesting because Ryder et al. note that, when girls belong to the minority gender, they often try to fit in and “be like the guys” in male-dominated tertiary study programs, whereas, when boys are the minority gender in a female-dominated program, they will seek to stand out from the girls [

40], which might explain why the boys in our study were more cushioned against dropping out. In the fourth term, students are expected to have integrated into their study programs by having assimilated and adapted to their new environment [

41]. They focus on completing and succeeding in their education, which might be why teaching aspects such as support from faculty and feedback are the focus. We suggest that students who seek a lot of support from faculty might not be as integrated as students who do not seek this kind of support, or, at least, students who receive support from faculty during the fourth term are particularly likely to quit their program.

The results presented above cannot necessarily be transferred to other contexts. In Denmark, about 25% of each youth cohort attends university. Programs are tax-financed and free of charge, with students receiving financial support from the government. Despite these benefits, 19% of university students (with large program variations) drop out within their first year. Students must, in no more than three attempts, pass specific exams explicitly selected for their programs before the end of the first year. We hypothesize that these financial and regulatory factors might have influenced the importance of certain study environment factors over others in our particular context. Despite the shortcomings of our findings in terms of transferability, it is an important point across contexts that what constitutes relevant quality assurance initiatives varies over time. In order to launch targeted quality assurance initiatives, we encourage colleagues to replicate our study across different faculties and universities. The time dependency of retention initiatives can theoretically be reflected using Tinto’s work, who, in 2016, described his understanding of dropout as ”a journey that occurs over time in which students are becoming capable and educated upon graduation. As such we need to be sensitive to the impact of time on the way we address the issue of student retention” [

42]. A straightforward explanation of the time dependence might be that the objectives and assignments in the final phase of a study (clearly exemplified by internships and theses, among others) require more academic skills and executive functions. This explains many of our findings on support and the differences between male and female students. Less straightforward explanations can perhaps be found in van Gennep’s theory on transition rituals in tribal societies [

41], in which Tinto found a reference for the procedural understanding of dropouts. van Gennep’s theory proposes that transitions take place through three phases—separation, transition, and incorporation [

43]. Tinto, therefore, describes the relation between the procedural understanding of dropout and an institution in the following way: ”Decisions to withdraw are more a function of what occurs after entry than what precedes it” [

43]. He, thus, suggests that “The problem of becoming a new member of a community that concerned Van Gennep is conceptually similar to that of becoming a student in a college. It follows that we may also conceive of the process of institutional persistence as conceived of tree major stages or passages—separation, transition, and incorporation—through which students typically must pass in order to complete their degree programs” [

43]. As students proceed through their course of study, we can see how the parameters associated with retention change. During the first term, when students enter the liminal phase, academic integration and identification play a protective role. In the second term, social aspects are more crucial for students’ persistency. Turner (1969) describes how students in the liminal phase might experience a sense of disorientation, uncertainty, and/or anticipation and excitement and how they tend to bond socially through these feelings and their liminal experience [

43]. He describes this societal mode in the liminal phase as unstructured and relatively undifferentiated (unlike non-liminal societies’ structural, hierarchical modes), which makes it easy for one to bond with co-liminal individuals. We note that students who experienced social relationships with fellow students were more likely to persist, whereas students who expected social relationships with fellow students were more likely to drop out in the second term.

This article’s contributions can be summarized under different categories. First, this article contributes a number of empirical findings regarding different study environment factors and their malleability, the extent to which study environment factors explain dropout, and the possibility of strengthening study quality in order to support students’ persistence. These findings contribute knowledge that can support early-alert interventions. The data have shown that identifying at-risk students early on in their courses and intervening accordingly makes a positive impact on student success [

44,

45], but studies have also shown that addressing students who are at risk can be counterproductive and, therefore, ethically indefensible. The approach suggested in this paper allows us to shift the focus from students at risk to the study environment and link early-alert interventions to the overall study environment’s quality development.

In addition to the empirical findings, this article provides a number of theoretical contributions. The differentiation between Tinto’s three systems—the academic system, the social system, and teaching—and, thus, the revision of his model are significant contributions to future studies in contexts other than the one examined in this article. Similarly, the framework for educational quality in which the results can be summarized is another significant contribution.

Finally—and, probably, most importantly—this article makes very significant methodological contributions through the development of an approach and the validation of an instrument to investigate study environment factors. What distinguishes our approach from previous attempts is that we, inspired by the works of Cheung and Slavin and Scheerens [

11,

19], took the malleability of the study environment factors into account. Thus, there is reason to assume that this is the decisive reason for our study’s success and investigate this assumption in later works. Regarding the context of this article, we will continue to work on strengthening the categories that we did not succeed in surveying, and we hereby invite colleagues in the field to accomplish the same in different contexts.

This article’s contributions are relevant in and applicable to educational and research contexts as well as political contexts, where they can be used as a basis for guidelines related to educational quality in higher education. It is, however, important to take into account the limitations of this study due to its limited context and not yet fully developed instrument. More studies in other contexts are needed to strengthen the method and instrument presented in this paper, and we hereby invite colleagues to collaborate on this.