1. Introduction

This study was undertaken as part of an initiative funded by the Coordination for the Improvement of Personnel (CAPES-Brazil), Minas Gerais State Agency for Research and Development—FAPEMIG and National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq), aimed at scrutinizing the strategies deployed by educators and academic institutions to foster digital educational practices. The endeavor was to engage with administrators and educators from primary and secondary schools in Germany to discern the nuances of these efforts in terms of fortifying (or otherwise) digital technology-mediated educational practices.

In this scholarly inquiry, several pertinent questions arise: How do educators navigate educational policies intended to accommodate the burgeoning demands of digitally mediated education? What are educators’ perceptions regarding the creation and assessment of digital resources, and how do they engage their students in this discourse? How do educators perceive their role in leveraging technologies, including disruptive ones like artificial intelligence, within educational contexts? Are discussions around digital technologies and their societal, economic, and cultural implications integrated into the curriculum by educators? Furthermore, how do educators evaluate their technological practices and perceive teacher training policies for technology integration?

It is posited that the post-COVID-19 pandemic milieu has significantly accentuated discussions concerning the adoption of digital technologies within educational paradigms globally [

1,

2,

3,

4]. Nevertheless, it is critical to acknowledge that such deliberations precede the pandemic and have been a part of the educational discourse for decades [

5,

6,

7,

8]. The surge in this debate is attributed to an empirical dynamic where, for the first time, digital technologies have been necessitated to address immediate and medium-term educational requirements on a global scale [

9].

On one front, there has been a solidification of initiatives aimed at augmenting digital technology use in educational settings, primarily through educational policies formulated by governmental entities with minimal educator involvement. This approach potentially heightens the risk of not realizing the anticipated outcomes, as evidenced by recent scholarly contributions [

3,

10,

11].

1.1. Germany’s International Discussions and Analytical Contexts

Understanding the importance of discussions on digital technologies also involves understanding the very importance of school education for modern capitalist society.

The concept of an extended right to education emerged historically with the consolidation of the rule of law, in which the concept of citizenship was constructed, and rights and duties were inscribed in the civil, political, and social spheres [

12]. In a process of social transformation, in which blood ties give way to a process of capitalist construction, education becomes a key element in strengthening nation states.

There are many historical elements that have fueled the need for public education. There has been a strengthening of democracy, a process of technological transformation that requires higher levels of education, pressure from the population for better living conditions, or even a restructuring of economic power relations between the countries [

13,

14,

15].

The development of an economic model in which free competition and free technological development give rise to new needs for knowledge and training must meet the new needs of nation states if they are to maintain their political and economic relevance.

Unlike the past, this is a model that, in the words of [

16], is reconfigured by “creative destruction”, in which continuous innovation destroys old structures, creating new ones in their place, constantly renewing the economy by introducing new products, processes, and markets, even if this means the obsolescence of previous technologies and products.

Digital technologies emerge in this context, perhaps in a more “hyper-destructive” format, in which obsolescence is not only the result of competition but is socially programmed to encourage the continuous search for what is announced as new, even though it is already obsolete.

The school is immersed in this contradiction, as it is called upon to meet contemporary demands, to include digital technologies in its curricular structures, to provide adequate teacher training, and to ensure that students have the best technological experiences [

17].

But at the same time, the school is the place of tradition, maintaining certain structures of knowledge that cannot be deconstructed due to the technological development of the market.

Faced with these dilemmas, the school is under pressure to incorporate every new technological development into its didactic-methodological structures. This movement can be seen in discussions about introducing radio into schools [

18], in broadening the debate about the influence of media such as television and cinema on learning [

19], and in the incorporation of video games into school teaching and learning processes [

20,

21,

22].

In recent decades, the problem has been how to introduce digital technologies into schools in order to improve student performance [

23], promote changes in the way curricula are organized and teaching materials are designed, develop new educational models based on contemporary technologies, or even meet social demands for schools to incorporate technologies that are part of the daily lives of students and teachers [

3].

The distinction made with contemporary digital technologies in this set of pressures on schools to incorporate the latest technology in use also gives rise to adjectives that wrongly characterize education, as if digital meant a structural change in the school system, when in fact, it means teaching something to someone through the mediation of digital technologies [

24]).

The idea that it is the school and its subjects (teachers and students) who must adapt to the technological condition ends up creating the impression that the supposed scientific progress and development is the development of machines and not humans. Humanity develops with the help of new generations of people who are capable of innovating and creating new things. Contrary to the common perception that machines “evolve” by themselves, particularly from the perspective of “new technologies” in a context of capitalist production and consumption, technological development takes place within the culture that human beings create, driven by human labor and social demands [

14]).

As a result, what is commonly referred to as “new technologies” emerge from the possession of the logical and material instruments that are essential for their realization in the current context. From this perspective, it is proposed that contemporary technologies are rooted in the material and techno-scientific evolution of humanity. In addition to the historical foundation, the social demand for innovation and novelties in the productive sector has a significant influence on technological development. Thus, based on Alvaro Vieira Pinto’s [

14] theoretical analysis, it is understood that no technology surpasses the capacities and aspirations of its time, the latter being molded by both the needs and consumption characteristics of the historical society in focus [

25].

There is a great deal of social pressure on schools to meet these contemporary demands, with the proliferation of educational policies that establish guidelines on what, how, and when digital technologies are used in educational systems. However, by disregarding the human factor in the educational equation, there is a risk of creating teaching and learning models that do not meet the needs of human reality—what students and teachers need in their daily educational endeavors.

Even in a context of experimentation and few empirical results demonstrating direct links between technology and educational improvement, as can be seen in analyses of the relationship between PISA scores and the use of digital technologies, social pressure to implement more “technological” curricula has led numerous countries to transform their educational systems to implement technologies, whether as debates integrated into curricula or the creation of specific computer-based content.

In the context of German education, we can see that there is an intense movement on the part of the federal and state governments [

26,

27] to incorporate digital education policies in schools (whether through the purchase of equipment, teacher training, or students). What can be observed from the point of view of time is that more light is being shed on the use of digital technologies, whether through face-to-face education or distance learning [

28,

29,

30].

According to [

31], the German context is still in its infancy when it comes to implementing more “technological” curricula and more universal access to technologies [

32]. Corroborates this situation by indicating that even in times of COVID and school closures, there was resistance to implementing remote (technology-mediated) education in Germany.

We can see that other countries are in a similar situation when they detect obstacles to implementing digital technologies in curricular structures [

9]. In general, there are indications that educational policies and teachers understand the importance of schools, including technological knowledge; however, the challenge is to understand the types of pedagogical proposals that can emerge.

Understanding this may not be an easy task, as technological changes come faster than pedagogical discussions seem to be able to adjust to. The debates on artificial intelligence show us this, as they already present new teaching challenges in a context where even the previous challenges have not been adequately debated and implemented.

The pressure on teachers also comes through transnational documents drawn up by organizations such as the European Commission, UNESCO, and the OECD, which set targets, strategies, analyses of computer use, and data on teacher training. There is a complete framework of documentation that directs countries to adopt more digital technologies in education.

These questions demonstrate that understanding the movements that teachers are making to make their practices more digital, in the sense of incorporating more digital technologies as mediators in the teaching and learning process, is not an easy task. This is because most of the documents concern general policies in which teachers do not participate, or at least teachers’ voices are not perceived in the results of the proposals presented.

These proposals, in which teacher participation is restricted, are defined as curricular isolation [

33]. This is a use of digital technologies centered on instruction, the development of content mediated by technologies whose main interaction is between student and material, undoing the processes of interaction, socialization, and curricular reconfiguration that would be typical in a context of physical interactions.

Whether they are legislative, economic, informational, communicational, management, or other instruments, these devices always configure, in addition to their own effects, a certain conception of public action (its meaning, its cognitive and normative framework), and a specific way of materializing and operationalizing government action [

34].

This set of instruments illustrates the complexity of this process, which involves not only curricular changes in basic education but also curricular restructuring in teacher training courses.

Alongside all these demands, it is also necessary to consider the power struggles that involve which curricular components will be prominent in the distribution of the workload of teacher training courses and primary and secondary education curricula [

35]).

The problem does not lie in providing a specific subject to discuss possibilities for introducing ICT into the teaching and learning process. Even if the percentage of subjects in technology and education were higher, what guarantees would there be that their theoretical and empirical assumptions would be the subject of dialogue with the other subjects on a course?

The issue, therefore, does not start from the insertion of specific subjects but from more complex discussions that start from the relationship between old and new technologies and the content needed for teacher training in a society whose students (and teachers) live surrounded by digital media that transform their social, cultural, and economic relations.

Data from the OECD [

36] show that young people with more privileged access to digital technologies have broader experiences of obtaining content or practical information (aimed at solving problems). This same research shows that more advantaged students have greater skills in reading and interpreting digital documents, which favors their positioning in the world in which they live, as well as other inclusive elements in a society whose mediation has been increasingly operated by these technologies.

What we want to problematize is that the TDIC, regardless of how much you know about its algorithmic, programming, hardware, or software aspects, establishes new ways of producing knowledge in different areas. It is important for those who determine educational policies to pay attention to these transformations so that the proposals to think of school as a space to prepare young people for a future active adult life and socio-economic and cultural protagonism are strengthened.

We, therefore, observe a view that directs technologies toward the interior of the school, but on the other hand, an apparent slowness in the appropriation of technological innovations, to the extent that they are infrequent in curricular structures, as we observed earlier.

Eric Hobsbawm calls this movement is called cultural resistance [

37], in which technology is not accepted when it promotes significant changes in our cultural and hierarchical structures. According to the author, technological transformations that represent technical improvements in our actions in the imagination, such as the increased speed of air travel, are better accepted than technologies that reconfigure power relations, such as access to information without the intermediation of teachers.

Therefore, we are living in a period of great challenges, and we need to integrate efforts aimed at understanding the importance of pedagogical work that considers the digital experiences that teachers and students have daily.

1.2. Research Questions

- ▪

Has the intensification of discourse around a more digitally mediated education motivated teachers to change their teaching practices?

- ▪

Are teachers familiar with the educational policies on digital technologies?

- ▪

What kind of dialogue do teachers establish with their students about digital technologies?

- ▪

Can teachers recognize their potential and limits when it comes to incorporating digital technologies into their practice?

2. Materials and Methods

This study was carried out as part of international cooperation between Brazil and Germany and included data collection by a Brazilian researcher. The goal of the ongoing research is to understand teachers’ motivations for appropriating digital technologies in their everyday practices.

To meet the proposed objectives, it became essential to understand teachers’ perceptions of knowledge and practices with digital technologies from the perspective of the European framework’s digital competence benchmarks.

The answers can provide us with clues about greater or lesser mobilizations towards more digital pedagogical practices.

We constructed a large-scale survey to be answered by teachers at different levels of education. Because the researcher was a Brazilian, we examined the best strategies for reaching teachers within the estimated time of the survey.

We chose the three most populous states in Germany (

Table 1): North Rhine-Westphalia (18.1 million), Bayern (13.4 million), and Baden-Württemberg (11.3 million). The population figures were sourced from the demographic portal. The choice was made because of the possibility of obtaining a greater number of schools and teachers surveyed, with a significant representation of the German population.

In view of the objectives, which included the participation of teachers in management and administrative positions, we carried out a complete survey of school administrators’ email addresses. We obtained a total of 5404 email addresses from schools in North Rhine-Westphalia, 1953 from schools in Bayern, and 1765 from schools in Baden-Württemberg.

The higher number of schools obtained in North Rhine-Westphalia was because the database system we obtained was complete and allowed us to save most of the email addresses in spreadsheet format. In the other states, we collected emails by visiting each of the schools’ websites individually and obtaining as many addresses as possible within the time it took to carry out the survey.

The heads of the schools (Schuller/Schullerin) were contacted by email to invite them to take part in the research and to share the invitation with the teachers at the schools under their administration.

The survey was carried out using SoSciSurvey (

https://www.soscisurvey.de/, accessed on 9 July 2024), based on the interpretation that this system would be the best suited to guaranteeing data protection and because it is produced and hosted in Germany, in compliance with the GPDR law.

We developed a pre-test that was sent to 30 people, including researchers and professors, so that we could validate the research instruments. From the answers and indications, we proceed to the final design of the questionnaire.

The participants were invited to take part in the survey. The questionnaire has six pages. The first page introduces the researcher, their institution of origin, the aims of the research, information on data protection, and the consent form. The second page contains the first section of the questionnaire, asking for information on gender, academic background, level of teaching, length of time teaching, age, and subjects taught in schools. Pages 3 to 6 contain 30 questions designed to meet the objectives of the research and related to the European community’s digital competence framework, Digicomp 2.2 [

38], and the specificities of the German education system.

This framework sets out five competencies needed by European citizens, which can be summarised as follows, as set out in the official document [

38]:

Information and data literacy: To articulate information needs, to locate and retrieve digital data, information, and content. To judge the relevance of the source and its content. To store, manage, and organize digital data, information, and content.

Communication and collaboration: To interact, communicate, and collaborate through digital technologies while being aware of cultural and generational diversity. To participate in society through public and private digital services and participatory citizenship. To manage one’s digital presence, identity and reputation.

Digital content creation: To create and edit digital content. To improve and integrate information and content into an existing body of knowledge while understanding how copyright and licenses are to be applied. To know how to give understandable instructions for a computer system.

Safety: To protect devices, content, personal data, and privacy in digital environments. To protect physical and psychological health and to be aware of digital technologies for social well-being and social inclusion. To be aware of the environmental impact of digital technologies and their use.

Problem solving: To identify needs and problems and to resolve conceptual problems and problem situations in digital environments. To use digital tools to innovate processes and products. To keep up-to-date with the digital evolution.

The choice to use this framework was made since it is now the public policy for the development of digital skills in school systems that have been debated and adopted by the countries of the European community. There are different levels of adoption of this framework among countries, but it is observed that Germany has made it a reference in the conduct of policies and investments in the school system, both regarding the purchase of equipment and in the training of teachers and students. Data from the German government show investments of around 5 billion euros across the country.

We designed authoritative questions based on the framework to address the following items: information and data literacy, communication and collaboration, digital content creation, safety, and problem solving.

The questions were drawn up considering the teachers’ possible day-to-day experiences with digital technologies in teaching and learning processes and educational policies on the subject.

The framework was chosen because it is currently the political mechanism that has been debated not only in the European context but also in the international literature [

10,

39,

40,

41].

Teachers, as historical subjects, mobilize based on what they consider to be most pertinent to their practice and their professional and life references, but they are also bound by the bureaucratic demands presented to them in everyday school life.

Still, from this perspective, the questions were elaborated in order to understand this human relationship built by teachers with technologies [

36,

42], which are based on movements of construction and deconstruction of oneself and equipment to be re-signified in the school environment. The questionnaire, therefore, sought to understand the relationships that teachers establish with public policies designed by the framework related to the European Community and the daily issues experienced by teachers.

Interpreting these mobilizations allows us to analyze the extent to which teachers move closer to or further away from institutional digital technology policies (drawn up by educational systems, for example).

3. Results

3.1. Analyzing and Describing the Profiles of the Participants

A total of 9122 emails were sent out. A total of 275 people started filling out the questionnaire, of which 166 answered all the questions (60% valid responses). The others only viewed the questionnaire or answered the first part.

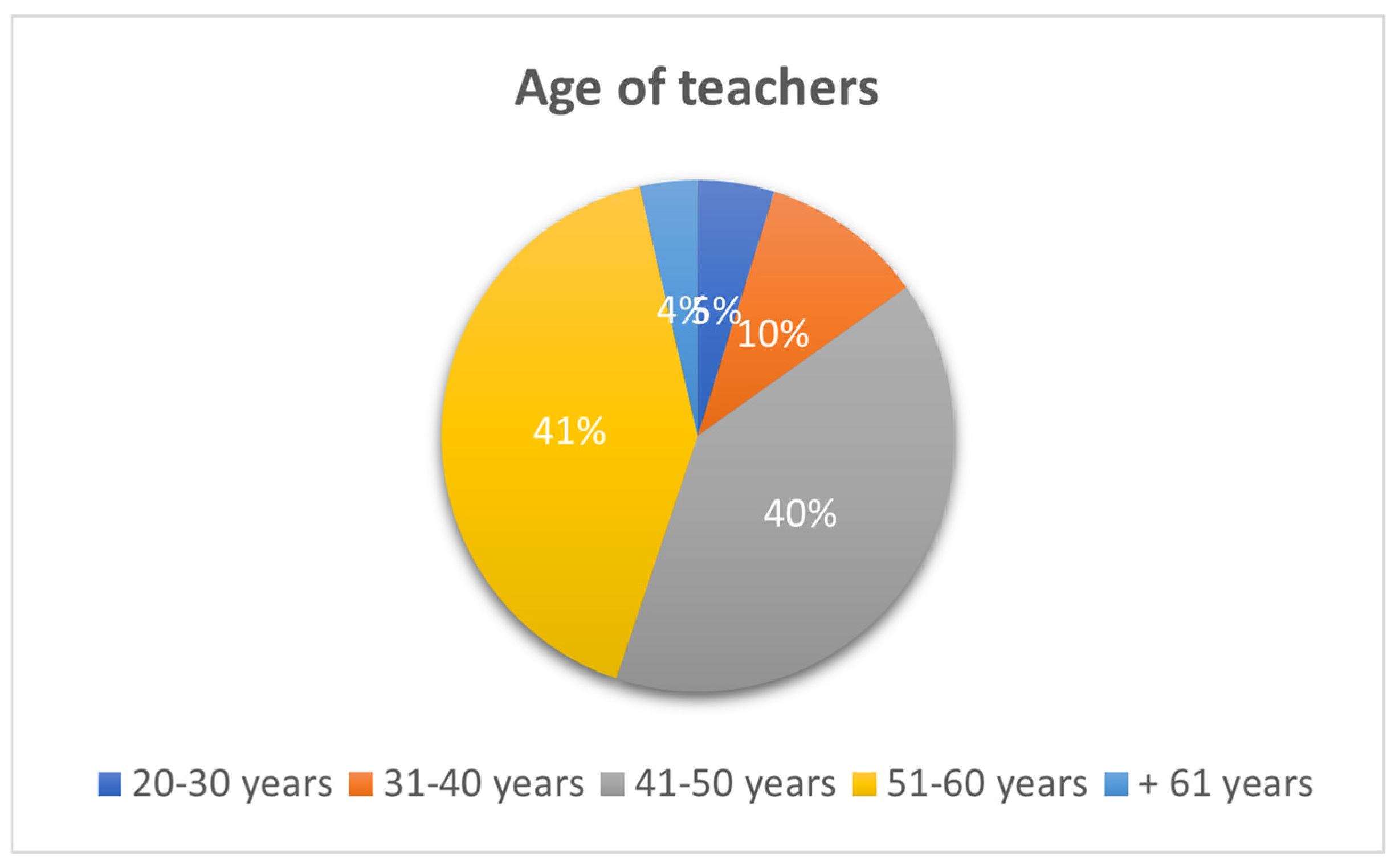

As far as age is concerned, most of the participants are aged between 41 and 50 (40 percent) and 51 and 60 (41 percent). Those over 61 account for 4 percent. In total, 85% of respondents are over 40, 10% are over 30, and 5% are between 21 and 30, as can be seen in

Figure 1.

These figures coincide with data from the Statistisches Bundesamt Deutschland of 2022, which show that around 50 percent of Germany’s teaching staff are aged 50 or over.

Regarding the sex and gender of the teachers, the data show that 60% of the respondents are female, 39% are male, and 1% are declared other. This figure is also compatible with the Statistisches Bundesamt Deutschland of 2022.

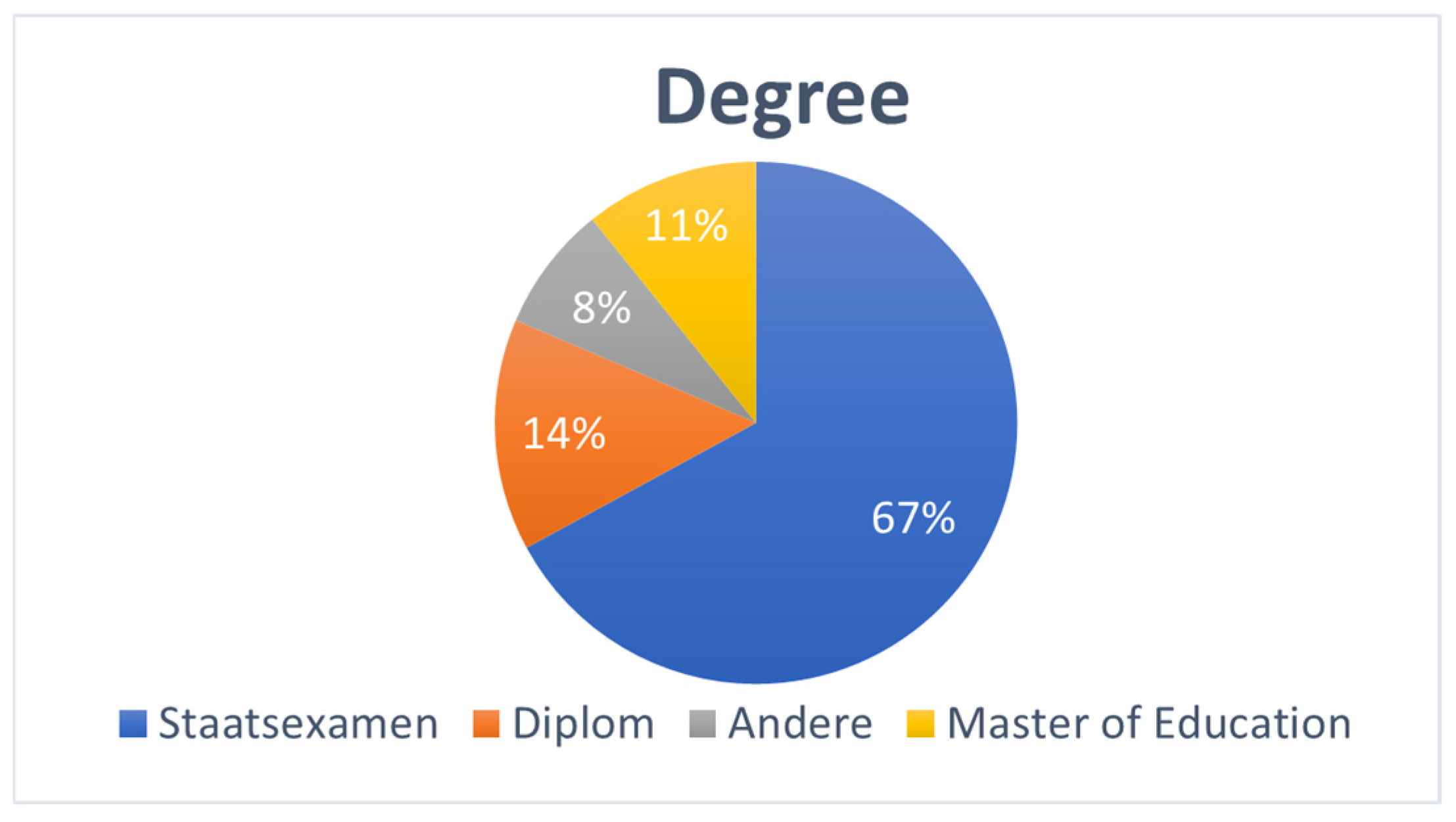

Regarding teacher education, the data (

Figure 2) show that around two-thirds have a Staatsexamen, 14 percent have a diploma, 11 percent have a master’s in education, and 8 percent have other training. This significant percentage of teachers with a Staatsexamen may be related to the average age of teachers since data from the Statistisches Bundesamt Deutschland of 2023 show that the number of teachers with this level of qualification was the majority until 2015, falling significantly in the following years. Currently, new teachers should preferably have a master’s degree in education.

Regarding the length of time they have been teaching (

Figure 3), 49% of the respondents say they have been teaching between 21 and 30 years, and 32% between 11 and 20 years. It was also noted that 7% have been teaching for more than 31 years, making 56% of the total number of respondents who have been teaching for more than 21 years. Eleven percent said they had 10 years or less of teaching experience.

Concerning the levels at which teachers teach (

Figure 4), it was observed that 47 percent work in secondary education, 28 percent in fifth to ninth grade, and 25 percent in first to fourth grade.

Here was more than one answer to this question, with the majority of teachers working simultaneously in fifth to ninth grade and secondary education (25% of the total).

As stated above, our choice of the European Community’s digital competence framework is not based on an analysis of the competencies themselves. We do not want to understand whether teachers are trying to develop these digital competencies because, as [

3] states, this is a complex and difficult analysis.

The framework serves as a reference for achieving our goal, which is to understand whether teachers mobilize toward digital practices. By developing questions related to the framework, we seek to present reflections that give us clues as to the extent to which teachers engage with technological knowledge in their pedagogical practices.

Initial inquiries about the significance of technology in the school context and pedagogical practices (

Figure 5). Despite being a more generic term, the first question links the relationship between digital and the educational context. The mean of 4.19, with a standard deviation of 0.85, suggests agreement with the statement, although we observed a moderate variability of opinions.

The second question, “You believe that digital education is important for the education of students and teachers”, has the highest level of agreement, with strong support from the respondents and an SD of 0.71. The third question, “You are familiar with the Media Competence Framework”, despite being more specific, also reflected a high level of agreement from respondents, with a value of 4.12, although its standard deviation was one of the highest (1.19), indicating divergent opinions.

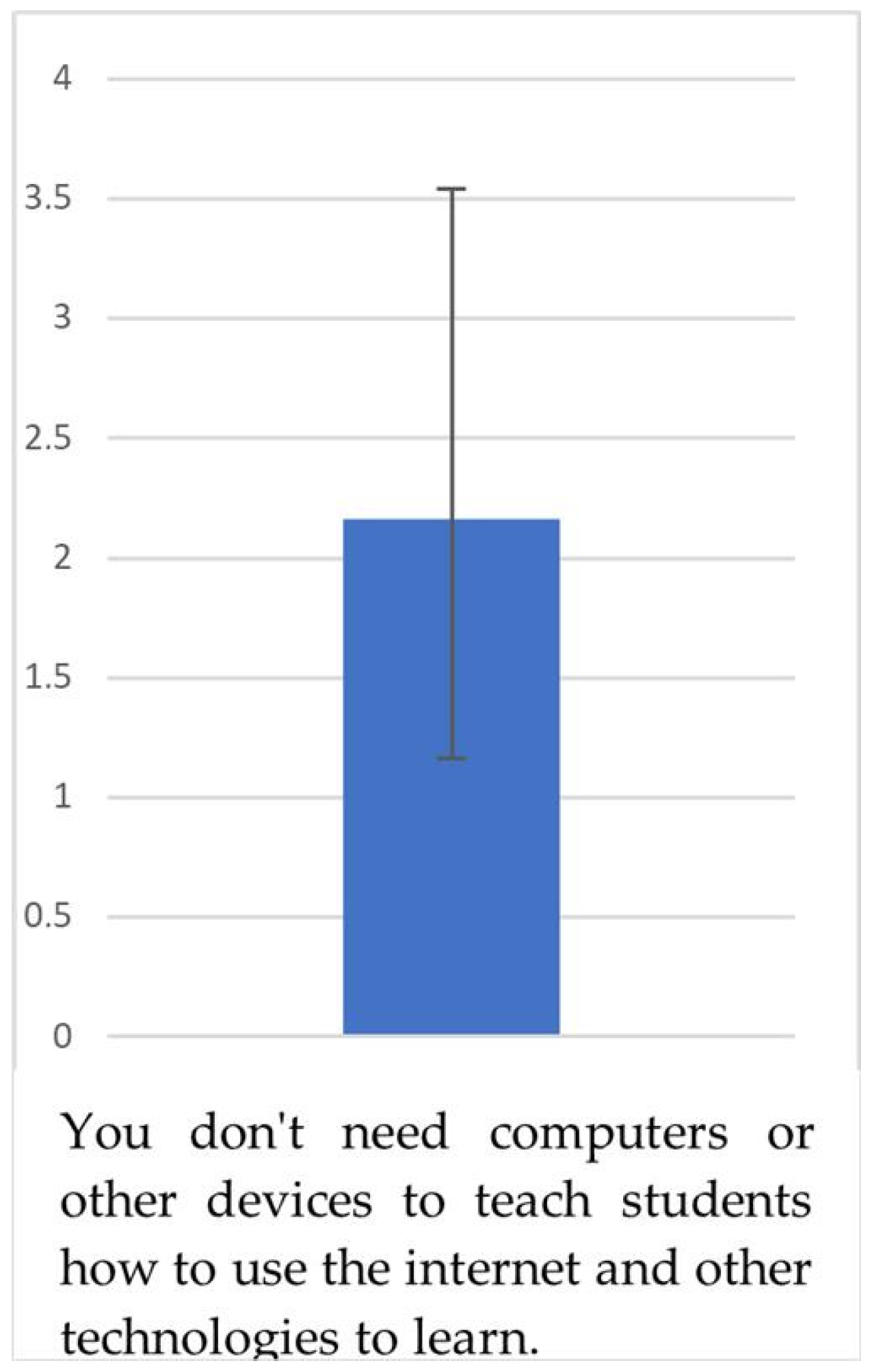

3.2. Equipment and Technology-Mediated Learning

The question that received the lowest average was designed to understand what relationships teachers build about the need or not to use digital equipment in the teaching and learning process to teach about technologies (

Figure 6).

This question received an average of 2.1, with a strong tendency to disagree, and a standard deviation of 1.38, also showing great disagreement between the answers.

Digital technologies, as human and historical artifacts, are not compulsory elements for forming subjects who are able to position themselves in a society that has a certain centrality in digital technologies [

43]. There is also a view that the place that digital technologies occupy in young people’s education does not depend on the existence of an expensive and up-to-date technological structure.

It is, therefore, a question of a dynamic in which the curricular components are dialogued in the context of the transformation of society itself and its technologies, with digital knowledge forming part of the curricular framework.

This question gives us clues that the feeling about the need to have digital technologies in schools to teach about them has considerable strength. Such sentiments corroborate historical documents that reinforce this direct relationship between equipment and teaching about technology [

36,

42].

3.3. Information and Data Literacy

Within the framework of information and data literacy (

Figure 7), the questions asked aimed to collect perceptions of the strategies that teachers have (or have not) put forward regarding discussions on this subject in the classroom. The following statements are presented: You integrate digital in theory and practice into the classroom, with an average of 4.02 and a standard deviation of 0.84; you discuss with pupils the possibilities of searching, comparing, and evaluating information and content on the Internet.

This question received responses with an average of 3.9, also demonstrating that there is agreement on the need for and importance of teaching students how to navigate in a connected world, select themselves, and position themselves in relation to the content they encounter.

Finally, we present a question on artificial intelligence, the subject of which is relatively new but has been the subject of intensive educational debate [

44]. The question is as follows: You discuss with students the impact of artificial intelligence technologies on their learning and content production. Our intention with this question was to try to understand how close teachers are to current discussions that have a direct impact on their practices and the ways in which students learn.

It has an average of 3.07, with a margin for neutrality among the respondents. But, it has an SD of 1.29, indicating that there is a wide range of opinions and a lack of clear consensus. It is interesting to observe this movement of responses, especially in a context in which artificial intelligence is emerging as the most disruptive technology in the contemporary educational environment.

3.4. Identity, Netiquette, and Citizen Participation

In the context of education, citizenship education has been a recurring theme in the international literature for decades [

45]. Revisiting the classic Marschal [

12], which establishes citizenship as a set of multiple domains in the field of civil, political, and social rights, we devised the following question: You talk to students about the possibilities of digital technologies for more citizen participation. The goal here was to detect perceptions of digital education’s potential based on broad themes that are part of the school’s scope.

The literature shows us that digital citizenship has become an element of great importance in the contemporary educational context [

45] and is a fundamental element in combating disinformation, racism, and forms of prejudice [

46]. Understanding the importance of this issue in the context of digital technologies also gives us clues as to the relationship that teachers establish between digital technologies and their role in shaping subjects who take a civic stance in society.

The result (

Figure 8) was interesting in that it showed an average of 2.56, slightly below neutrality, moving towards a tendency to disagree. The SD of 1.31 also shows significant dispersion in responses, suggesting divided opinions. It is a question that provides us with good clues for future research on the subject.

In the other question, we asked the respondents, “Do you talk about topics such as cyberbullying, netiquette, and digital violence in schools?” This question also sought to observe how teachers deal with issues that are part of students’ daily lives because of the increasingly intense use of screens [

47].

The result shows an average of 3.43, very close to neutrality. At the same time, this is the question with an SD of 1.46, the highest of all the questions, which indicates a wide variation in responses and, consequently, a divergence of opinions.

It is a question that, indicatively, shows us signs of teacher mobilization around the problems that become part of students’ lives. In this case, regardless of whether digital technologies are included in the curriculum, the presence of young people on screens allows them to navigate between presences and virtualities that are simultaneous with school times.

Finally, we asked the following: Students can distinguish their identity in the virtual world from the physical world. This question sought to detect teacher mobilization around their monitoring of the multiple identities that young people can create in virtual environments and their relationship with the face-to-face environment.

The results show an average of 3.06, which puts the question in neutral territory. The SD is 0.97, with a moderate variety of answers.

These responses indicate that there are many important discussions in the school environment that allow teachers to observe and recognize the movements of navigation and self-construction. This is a theoretical field that has not yet been explored but which we consider pertinent for future research from the perspective of relating school knowledge to students’ navigational experiences.

3.5. Digital Content Creation

Teacher mobilization for pedagogical practices with digital technologies can involve the production of digital content. To try to obtain data on these mobilizations, we asked the following five questions (

Figure 9):

You discuss with students their concerns about copyright, remixing, and appropriation of content available on the Internet. Once again, we came across a set of divergent answers, with a mean of 3.4 and an SD of 1.2. There is a dispersion in the answers, showing a tendency towards neutrality but with a balance between the answers. We consider the results of this question to be important, as they are not only related to digital technologies but also to more general questions about the authorial production of content, which is independent of the medium chosen. The results indicate that this is an issue that has not been fully resolved in the school environment and that requires further analysis and understanding.

Do you believe that teachers should teach their students to produce digital content more critically? The results showed that there is a strong perception among teachers that they need to act in the classroom to teach their students to produce digital content more critically. The average reached 4.5, with an SD of 0.85, and more than 60 percent of respondents reported that they totally agreed with the question.

From the teacher’s point of view, even though they show limits in terms of the use of technology, at the same time, they realize that this is an activity for which they are responsible.

Students produce different types of digital content (e.g., TikTok videos, blog posts, and emails). In this question, we sought to determine whether teachers perceive variety in the types of content and technological services used by students. The average was 3.07, with a moderate SD of 1.1. The percentage of teachers who disagreed in part or totally reached 38 percent of all respondents, which shows a strong impression that students do not produce a variety of productions mediated by technology. The questions relating to student productions show that teachers are critical of what their students produce.

Students will be able to plan, design, and produce digital media for different situations. In this question, we sought to analyze teachers’ perceptions of what students have produced in terms of digital content. This is a broad question that could detect school productions or productions for other purposes. Our aim was to analyze perceptions.

The average obtained on this question was 3.1, very close to neutrality, with a reasonable SD of 1.2. Approximately 33 percent of teachers indicated that they totally or partially disagreed with the statement, which opens up other possibilities for research into what teachers might consider to be the ability to design and produce digital content.

You plan, design, and produce media content for the appropriate audience. This question received an average of 3.4, above a neutrality index, but with a high SD (1.25), which shows great divergence in the teachers’ responses, demonstrating that this is not yet a well-resolved issue in the context of teaching work and practices.

Even in the post-COVID-19 pandemic context, with greater public investment in Germany in teacher training and the purchase of equipment, it appears that this is not a topic that has yet to be more widely adopted.

4. Research Limitations

To comply with the spam policies of the email servers, we sent messages at certain time intervals. This allowed us to observe how the answers were presented by the participants and to make some considerations.

We have a hypothesis that most respondents are school managers. This is because we noticed that after the invitation was sent out, the responses were provided very close to the time the message was received.

Obtaining teachers’ personal emails is an extremely difficult task, as they are not available on school websites or other official spaces. In this way, we are dependent on forwarding the message sent to the school. We do not know for sure if these messages were forwarded to teachers.

The number of responses, therefore, cannot be related only to the number of messages sent to the school boards because the manager is not necessarily a target person unless they are a teacher.

The approach through digital means, such as sending emails, may also have determined the number of responses because, in a current context in which people receive numerous emails on a daily basis, it is to be expected that they do not respond to everyone.

Thus, one of the research limitations may be the stronger presence of this teacher profile. However, we believe that these data help us to better understand the positions of teachers who, possibly, move better between teaching practices and the legal and institutional understandings of the government’s digital technology policies.

However, the data can be considered valid and generalizable since the responding teachers are consistent with the characteristics of the teaching staff of German schools available in the official databases.

The time it took to carry out the research was another factor that led to it being presented in terms of exploratory research. We believe that future research could delve deeper into the issues to broaden our understanding of how teachers mobilize their knowledge for digital contexts in schools.

5. Discussion

Recognizing the historical nature of digital technologies seeks to place them in a different place from the simple technical insertion of objects or services in the school environment, as presented in this paper. Technologies, as a historical process, are part of the daily lives of teachers and students in different environments, whether in schools or not [

10].

In this sense, we cannot think of maintaining a teaching practice that manifests itself from an analog perspective, not least because this perspective can no longer be understood in isolation since society is intensively mediated by digital technologies that reconfigure people’s lives at all ages [

24,

36].

Furthermore, the economic perspective of the consumption of digital equipment and services cannot be overlooked, given that the so-called big tech companies, such as Apple, Microsoft, Alphabet, and Meta, are today the most valuable companies in the world.

What we were able to detect was not a movement around analog but perhaps a teaching movement directed towards aspects of resistance, in the sense that teachers can see the importance of discussing digital technologies in the school environment [

41].

The data are solid, showing that teachers recognize technology-mediated education for students as extremely important for their education in general. However, at the same time, teachers tend to have some difficulties incorporating aspects of digital education into their daily practices [

3,

11,

43].

When we looked at the institutional documentation, we noticed that the three states analyzed have extensive documentation indicating policies for training teachers and students to develop technology-mediated activities. At the same time, it is important to note that public policies have what we consider to be inscribed in the legal system, which may have been produced with or without social participation. There is also what is considered external to this system, which represents the interpretations made by the subjects who are the targets of the policies [

15].

The results of the study demonstrate a significant recognition of the importance of digital technologies in education by teachers in Germany. Most respondents expressed a positive view of the potential of digital technologies to enrich the educational process and better prepare students for the challenges of the future. This finding is in line with the policy guidelines established by the German government and underlines a mobilization around the integration of digital technologies into pedagogical practices [

27].

Teachers and educational institutions demonstrate that they recognize the fundamental relevance of digital technologies in the education of students, aligning with the guidelines and public policies established by governance bodies. This awareness reflects not only the acceptance of technologies as pedagogical tools but also the understanding of their role in preparing students for an increasingly digitized world.

However, despite this mobilization, the study also revealed some hesitations and challenges in the effective implementation of these technologies in the educational environment.

So, even though we can see a solid movement around different institutional actions, such as teacher training, equipment purchases, distribution to school students, etc., we need to understand how teachers see themselves as targets of these policies.

In this sense, it is important to note that the demands for more training in technological terms indicated in the survey results show that teachers are still far removed from the knowledge they consider necessary to perform adequately in the classroom. We think it would be appropriate to look more closely at teacher training to understand whether these training demands are observed in initial training or in teachers’ ongoing in-service training [

31,

40].

We observed that there is a strong feeling about the importance of teachers working with digital technologies in their pedagogical practices, but at the same time, they demonstrate fewer actions of this kind in the classroom.

These distances can be explained by gaps in teacher training, but they can also be understood through other argumentative perspectives, such as teacher resistance to technology and the difficulties of this inclusion in the current conventional school model with determined times and spaces.

We note that there is a need for more in-depth approaches and theoretical discussions that go beyond the apparent answers that we have had for decades in the field of educational research. Teacher training and the use of technologies, infrastructure, and educational policies that are sensitive to the needs of teachers and students are reasonably developed in the field of educational research.

Starting from the historical perspective of technology, the approach may need to be reconfigured in terms of thinking about elements that have not yet been considered in educational research. The dimension of school time is one of the issues that deserves attention. The heterogeneity of information genres in different media (audio, video, software, games, digital social networks, etc.) imposes other educational times that include not only the preparation of materials but also the interaction times between students and teachers in the school environment.

This involves including in-school timetables, for example, technology activation times (switching on, off, etc.), the specificities of each medium and their configurations for lesson times, and the speed at which digital objects incorporated into the classroom are updated or changed.

The school, as the social organizer of the new generations, is living with technological transformations that affect teachers and students and, at the same time, operates under a model that still maintains a traditional structure of quantitative and temporal distribution of curricular content.

Teachers find themselves in the apparent contradiction of being frequent users of technologies that address this issue in their subjects to a lesser degree than they would like.

Another aspect that draws attention concerns how teachers see the phenomenon of artificial intelligence and the prospects for authorial production mediated by technologies.

The results show a certain difficulty in articulating these elements, even though, in analog terms, the topic presupposes the elaboration of content by a third party (machine or human). In other words, it is a discussion whose presence is long-standing in schools, with the potential to accelerate the outsourcing of authorial production using technologies such as generative AI. Although AI is a novel element, the object that generates its discussion is old [

29,

44].

A look at the official documentation of the states of North Rhine-Westphalia, Bavaria, and Bayern shows us that the subject of digital technologies relates to the use of equipment such as computers, tablets, software, and digital services. This understanding can also be seen in UNESCO, the OECD, etc. Therefore, there is a reading that education in digital contexts necessarily entails the use of equipment and services with these characteristics [

9,

36,

42]

According to these documents, the attribution of a digital practice would involve the use of technological equipment and instruments, leaving the conceptual, social, and cultural dimensions of digital technologies in the background.

We realize that teachers tend to respond in this direction when they indicate the need to use digital equipment in the context of digital education.

But, at the same time, the results show that teachers understand the most complex aspects of technologies, such as student positioning, and perceive the importance of continuously dialoguing technologies as elements of social construction that need to be debated in the school environment.

This situation can be perceived above all in the results related to the dimensions of violence, security, and autonomous production of students mediated by digital technologies.

Teachers also perceive the need for better teacher training policies to feel more confident in practical use, in addition to perceiving numerous gaps among students in the way they appropriate technologies. These results demonstrate the need for the school to integrate itself in an increasingly institutional and human way, connecting the school community to the problems generated by social-technological development.

We believe that digital education, in the current school model, can be implemented without the presence of physical and logical equipment. It is a question of redesigning the curriculum to remove the technical element from the training axis, redirecting the conceptual and social aspects of technology to the school environment.

As we have discussed, the school, as a locus for citizenship training, is independent of the use and appropriation of digital technologies in its spaces. There are various academic discussions today that consider the risks of digital technology consumption and the possible weakening of national states’ democratic structures. There is also the risk of the emergence of transnational technology service companies, whose power extends beyond those established by countries around the world [

11,

19].

The critical education of students in the context of citizenship and digital technology is still observed with reservations from the perspective of the respondents. There are still unclear discussions about the role of teachers in this education in the context of digital technologies and the school. Once again, we are faced with knowledge and practices that are not related to technological training but to broad teacher training that enables them to discuss these issues and relate them to the reality of their students. Since this reality is permeated by digital technologies, it is expected that this will be part of school debates [

45].

The results are still broad in this aspect since it is possible to observe a preponderance of school technological training in a more scholastic sense, in which everyday and broader issues are still debated in an incipient way. This debate involves inscribing the school not only as a locus of the relationship between technology and the curricular component but as a space in which the different problems socially produced by technologies need to be incorporated into school debates.

Once again, we see aspects of contradiction since both students and teachers are immersed in a society with digital prominence. Therefore, it is unlikely that these characteristics are not part of the dynamics of each subject in its formative and life context.

The data presented, therefore, show that teachers have a solid view that understanding digital technologies and carrying out their practices with digital technologies allows them to offer a more qualified education to students.

6. Conclusions

This exploratory research in focus reveals a complex and multifaceted overview of the integration of digital technologies in education, particularly in the post-pandemic context, comparing perspectives and mobilizations of teachers and educational institutions in Germany. The results show a growing awareness of the importance of digital technologies in education, a mobilization around the adoption of digital pedagogical practices, and a still cautious positioning in relation to emerging technologies, such as artificial intelligence.

The report addresses Germany’s education policies in the context of the integration of digital technologies into compulsory education, highlighting the central role of the federal government and the states in promoting digitalization in schools. Initiatives such as “Escola DigitalPakt”, with funding of EUR 5 billion, aiming to expand digital education infrastructure, including high-speed internet connections, digital devices for teachers and students, and digital learning platforms. This research points to a significant awareness and mobilization among teachers around the importance of digital technologies in education, evidencing an alignment with established policy guidelines.

In order to answer the first research question, “Has the intensification of discourse around a more digitally mediated education motivated teachers to change their teaching practices?”, we realized that there is a clear mobilization of teachers around digital pedagogical practices, indicating an effort to integrate digital technologies effectively and reflectively into their educational practices. This suggests a transformation of teaching methodologies, where digital technologies are seen as allies in the learning process, promoting a more interactive, accessible, and personalized education.

We also observed some hesitation in relation to the adoption of contemporary technologies, such as artificial intelligence, signaling a gap in the continuous training of teachers and in the adequacy of the technological infrastructure of schools.

This hesitation can also be interpreted as a caution in adopting new technologies without a clear understanding of their pedagogical and ethical impacts. The need for continuing education that enables teachers to explore the potential of these emerging technologies critically and constructively in education is highlighted.

These are critical challenges that need to be addressed if the integration of digital technologies in education is to be effective. Teacher training emerges as a crucial element, necessitating educational policies focused not only on access to technology but also on continuous professional development that enables educators to use these tools in pedagogically meaningful ways.

In addition to technological integration, the study highlights the importance of critical reflection on the use of digital technologies and their relationship with digital citizenship. Promoting ethical behavior online, raising awareness about internet safety, and combating disinformation are key aspects of digital literacy that should be incorporated into pedagogical practices. This approach not only prepares students to navigate the digital world safely and responsibly but also fosters a deeper understanding of the social, cultural, and political implications of digital technologies. This leads us to realize that the question “Can teachers recognise their potential and limits when it comes to incorporating digital technologies into their practice?”, was answered to the extent that the results demonstrate that teachers reflect on their practices and understand their limits, as well as relate these limits to their individual and collective (political) aspects.

The post-pandemic scenario has brought both challenges and opportunities for digital education. On the one hand, the need to quickly adapt to remote learning has exposed gaps and inequalities in access to and use of digital resources. On the other hand, it has provoked an accelerated reflection on the pedagogical possibilities of digital technologies, driving an educational transformation that could have lasting effects.

The data collected and analyzed suggest various directions for future educational investigations and practices. First, there is a clear need for research that explores effective pedagogical strategies for the implementation of emerging digital technologies in education. In addition, research on teachers’ in-service training in digital skills is vital to overcome the identified barriers. In addition, it is critical to develop holistic educational policies that promote not only technological integration but also critical reflection and digital citizenship education as core components of education.

Continuous teacher training emerges as a key pillar to ensure that educators are not only familiar with digital tools but also empowered to integrate them pedagogically and effectively into their practices.

This implies a more strategic and systematic approach to teacher professional development, where learning about digital technologies is continuous and aligned with rapid changes in the field of technology.

The research also demonstrates that teachers seek to dialogue with students to understand their perceptions about digital technologies, demonstrating that the research question, “What kind of dialogue do teachers establish with their students about digital technologies?”, is perceived and responded to by the teachers when they talk about the types of communications established with the students about their previous and accumulated knowledge.

The survey collected perceptions from teachers at different levels of education about the implementation of these educational policies, revealing a positive perception of the importance of digital technologies in education. This allows us to positively answer the second research question: Are teachers familiar with the educational policies on digital technologies?

Teachers expressed an awareness of public policies and demonstrated that they were engaged in digital pedagogical practices. However, there was also a neutrality towards the adoption of more contemporary technologies, such as artificial intelligence, suggesting a field for professional development and future research.

The data obtained from the interviewees suggest a correspondence between policy initiatives and educational practice. Regarding the practical implications of the results obtained, it is assessed that teachers recognize the relevance of digital technologies for student education and are mobilized around digital pedagogical practices, aligning themselves with the policies established by the state. This alignment indicates that policies for the digitalization of education capture some of the needs presented by teachers.

However, the results also show that teachers’ perception is that there are absences or gaps in their training and the need for public policy makers to develop more actions and initiatives that focus on integrating digital technologies into the school environment.

Based on these results, it is possible to conclude that Germany’s educational policies regarding digitalization in education align with teachers’ perceptions and practices, evidencing remarkable progress in the adoption of digital technologies in schools. However, the research identifies areas for continued development, particularly in preparing teachers and students for emerging technologies, which can further enrich the German educational landscape and offer future directions for education policy.

The way forward requires continued collaboration between educators, policymakers, and academic communities to fully exploit the potential of digital technologies in promoting equitable, inclusive, and transformative education. It is hoped that this research can offer significant contributions to Germany’s education policies about digitalization in education. It is essential to align these policies with teachers’ perceptions and practices, especially in the face of rapid growth in this field. It is believed that empirical studies play a crucial role in the planning and implementation of educational actions related to the field of technologies and teacher training.