1. Introduction

The landscape of higher education has undergone a profound transformation in recent years, largely driven by the rapid integration of Digital Learning technologies. This shift, accelerated by global events such as the COVID-19 pandemic, has presented both unprecedented opportunities and significant challenges for educational institutions worldwide [

1]. The sudden transition to online learning during the pandemic highlighted the critical need for robust Digital Learning strategies and infrastructure in higher education [

2].

Prior to 2020, the integration of Digital Learning within the higher education system in Israel was progressing at a modest pace [

3]. However, the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic markedly accelerated this integration, catalyzing the rapid adoption of digital platforms and methodologies [

1]. This sudden shift mirrored global trends, but was uniquely shaped by Israel’s specific cultural, technological, and educational context.

The rapid shift to Digital Learning during the COVID-19 pandemic has been a global phenomenon, with varying impacts across different educational contexts. Hodges et al. [

4] distinguish between well-planned online learning and emergency remote teaching, highlighting the unique challenges faced during the pandemic. This distinction is crucial for understanding the Israeli context, where the transition was similarly accelerated. Marinoni et al. [

5] emphasize the global disparities in digital infrastructure and readiness for online learning among higher education institutions, a factor that likely influenced the Israeli experience as well.

Ter Beek et al. [

6] underscore the critical need for digital competencies in higher education, emphasizing that continuous professional development is essential for lecturers to effectively integrate technology into their teaching practices. They argue that technological innovations are crucial for preparing students and lecturers for future labor market demands, necessitating a deeper way of learning and the reconsideration of underlying knowledge and beliefs. This perspective highlights the importance of not only implementing Digital Learning tools, but also fostering a comprehensive shift in educational approaches to meet evolving workforce needs. In practice, this shift is exemplified by studies such as that of Rapanta et al. [

7], who examined how university teachers adapted their pedagogy for online learning during the COVID-19 pandemic, highlighting the importance of presence, cognitive engagement, and inclusivity in digital teaching practices.

These adaptations underscore the broader implications of digital transformation in higher education. This emphasis on digital competencies and professional development aligns with recent research on the digital transformation of higher education. Alenezi [

8] highlights that digital transformation in higher education institutions involves changes across multiple areas, including teaching, administration, infrastructure, and organizational culture.

Despite the accelerated adoption, a substantial lacuna persists in comprehending the nuanced experiences of lecturers as they navigate the transition to Digital Learning environments in Israel. This study aims to fill this gap by investigating lecturers’ perceptions of the Digital Learning initiative launched by the Council for Higher Education (CHE) and the Planning and Budgeting Committee (PBC) [

9]. By focusing on a higher education institution in northern Israel, this research provides context-specific insights into the challenges and opportunities presented by Digital Learning. Recent studies, such as those by Means et al. [

10] and Hodges et al. [

4], have shown that the effectiveness of Digital Learning depends heavily on proper design and implementation.

The CHE and the PBC responded to the emergent needs by launching a comprehensive multi-annual program aimed at strategically promoting and developing Digital Learning across higher education institutions. This initiative laid down a robust foundation, encompassing technological, human, and techno-pedagogic infrastructures, as well as systems for ongoing monitoring and data collection, to continually enhance and expand Digital Learning applications at the institutional level.

In 2022, the CHE published a document outlining definitions and classifications for Digital Learning, categorizing it into three forms: face-to-face courses with digital integration, hybrid digital courses, and fully online courses. These forms have been extensively studied in recent years, with researchers exploring their effectiveness, challenges, and impact on higher education globally.

Our study encompassed all three models defined by the CHE, evaluating the impact and effectiveness of Digital Learning across face-to-face courses with digital integration, hybrid digital courses, and fully online courses. This comprehensive approach allowed us to compare and contrast the implementation and outcomes of Digital Learning across these different formats.

For instance, Means et al. [

10] conducted a meta-analysis of online learning studies, finding that blended and online learning can be as effective as traditional face-to-face instruction when designed properly. However, Hodges et al. [

4] argue that emergency remote teaching, as experienced during the COVID-19 pandemic, differs significantly from well-planned online learning. These studies underscore the complexity of implementing Digital Learning strategies and the need for context-specific research.

Employing systematic inquiry methods, researchers have deepened our understanding of Digital Learning implementation. For instance, Zawacki-Richter et al. [

11] conducted a systematic review of artificial intelligence in higher education, highlighting both its potential and the ethical challenges associated with these technologies in teaching and learning.

These findings are further supported by Kaqinari [

12], who emphasizes that effective professional development for lecturers on educational technology use requires long-term, ongoing support that allows time for learning, practice, application, and reflection.

Despite these valuable insights from global research, there remains a significant gap in understanding the specific experiences and perceptions of lecturers in the Israeli higher education context, as they navigate this rapid digital transition. This study addresses this gap by providing a nuanced exploration of lecturers’ experiences with Digital Learning implementation in the specific national and institutional context of Israel. By focusing on a higher education institution in northern Israel, we aim to uncover the unique interplay between technological adaptation, pedagogical innovation, and cultural considerations, in this diverse and technologically advanced society. Our research methodology, detailed in the following section, was designed to capture the complexities of this transition through an in-depth qualitative inquiry.

Recent systematic reviews and meta-analyses have provided further valuable insights into the effectiveness and challenges of Digital Learning in higher education. Bond et al. [

13] conducted a systematic review of 242 studies on student engagement in technology-enhanced learning, finding that while digital tools can increase engagement, their effectiveness depends heavily on how they are implemented. Similarly, Castro and Tumibay [

14] meta-analyzed 50 studies on e-learning in higher education, revealing that e-learning can be as effective as traditional face-to-face instruction when properly designed and executed. However, they also highlighted persistent challenges, such as technological barriers and the need for enhanced digital literacy, among both students and lecturers.

These findings are further supported by Kaqinari [

12], who emphasizes that effective professional development for lecturers on educational technology use requires long-term, ongoing support that allows time for learning, practice, application, and reflection. Additionally, Alenezi [

1] highlights that digital transformation in higher education institutions involves changes across multiple areas, including teaching, administration, infrastructure, and organizational culture.

A recent comprehensive review by Halabieh et al. [

15] identified four key failings in higher education: quality, relevance, access, and cost. They found that higher education institutions are struggling to prepare students for success in an increasingly complex, competitive, and digital world. Their study provides a valuable framework for understanding the challenges faced by higher education institutions globally and aligns with many of the issues we explore in the Israeli context.

Fernández-Raga et al. [

2] add to this understanding by highlighting that implementing educational technology innovations is a complex process that requires changes across multiple dimensions, including lecturers’ values, motivations, and practices. These recent studies underscore the complexity of implementing Digital Learning strategies and the need for context-specific research, which our study aims to provide in the Israeli higher education landscape.

This study represents the first systematic inquiry into the effects of the CHE’s Digital Learning program from the perspective of lecturers. By focusing on lecturers’ perspectives, it provides unique insights into the practical challenges and opportunities associated with implementing Digital Learning, which is essential for developing effective policies and support systems in higher education institutions. It investigates the extent to which this program has fostered Digital Learning and explores the myriad challenges, barriers, and opportunities introduced by digital technologies to teaching, learning, and evaluation processes.

The objective of this research is to scrutinize the opportunities generated by the Digital Learning program and identify the principal challenges and barriers faced by lecturers as they integrate these tools into their educational practices. The findings aim to illuminate the complex dynamics involved in the implementation of the Digital Learning program, offering insights into how digital education can be effectively embedded within the pedagogical framework of higher education institutions. By examining these dynamics in the Israeli context, this study contributes to the global discourse on Digital Learning in higher education, offering insights that may be applicable to other rapidly digitalizing educational systems worldwide.

This paper is structured as follows: First, we provide a comprehensive literature review, including an exploration of the TPACK framework and a SWOT analysis of Digital Learning. We then detail our qualitative methodology, followed by a presentation of our results, organized into educational, personal, cultural and social, and institutional domains. The discussion section contextualizes our findings within the broader literature and explores the implications. We conclude with a summary of the key findings, recommendations, and suggestions for future research.

This aligns with the work of Castro Benavides et al. [

14], who emphasize the need for a systematic approach to digital transformation in higher education institutions. While existing research has extensively examined Digital Learning implementation in various contexts, there remains a significant gap in understanding the specific challenges and opportunities within the Israeli higher education system. This study addresses this gap by providing an in-depth exploration of lecturers’ experiences with Digital Learning in a culturally diverse, technologically advanced setting. By focusing on the unique interplay between technological adaptation and cultural considerations in Israeli higher education, our research offers novel insights that extend beyond the current understanding of Digital Learning implementation in higher education.

Given the unique cultural and educational context in Israel, and the rapid digital transformation catalyzed by the COVID-19 pandemic, this study aims to address the following research questions:

How do lecturers in Israeli higher education perceive and experience the implementation of Digital Learning initiatives?

What are the unique challenges and opportunities presented by Digital Learning in the Israeli cultural and educational context?

How do lecturers adapt their teaching practices to integrate Digital Learning tools effectively?

To address these research questions, we employed a qualitative phenomenological approach, conducting in-depth interviews with lecturers at a higher education institution in northern Israel. Our analysis focused on uncovering the lived experience of educators as they navigated the transition to Digital Learning, with particular attention paid to the unique cultural and institutional factors shaping this process in the Israeli context.

By addressing these questions, this research contributes to the broader understanding of Digital Learning implementation in diverse cultural settings and provides insights that may be applicable to other rapidly digitalizing educational systems worldwide. The remainder of this paper is structured as follows: First, we provide a comprehensive literature review, including an exploration of the TPACK framework and a SWOT analysis of Digital Learning. We then detail our qualitative methodology, followed by a presentation of our results organized into educational, personal, cultural and social, and institutional domains. The discussion section contextualizes our findings within the broader literature and explores the implications. We conclude with a summary of the key findings, recommendations, and suggestions for future research.

1.1. The TPACK Framework

The Technological Pedagogical Content Knowledge (TPACK) framework, introduced by Huang et al. [

16], provides a comprehensive model for understanding the complexities teachers face when integrating technology into their pedagogical practice. This framework emphasizes the convergence of three primary forms of knowledge: content knowledge (CK), pedagogical knowledge (PK), and technological knowledge (TK). Huang et al. [

16] posited that effective educational planning requires an intricate balance of these knowledge domains to enhance the efficacy of technology-integrated teaching.

Despite the theoretical promise of the TPACK framework in harmonizing these knowledge areas, research indicates persistent inefficiencies in the practical use of online platforms [

2,

17]. These studies suggest that while the framework offers a robust strategy for incorporating digital tools into teaching, the actual application often falls short of its potential, primarily due to the underutilization and superficial integration of these technologies. For instance, Martin et al. [

18] argued that the key to optimizing technology use in education lies in the meticulous planning of instructional activities, which includes a clear articulation of the learning objectives, detailed descriptions of the learning resources, and explicit expectations for student engagement and outcomes. Furthermore, the presence and active engagement of the teacher as a ‘learning manager’ are crucial in navigating the Digital Learning environment effectively.

This segment of the literature underscores a significant gap between the ideal integration envisioned by the TPACK framework and the real-world application in educational settings, highlighting the need for enhanced strategies that better align technological tools with pedagogical goals and content delivery.

1.2. SWOT Analysis for Evaluating Digital Learning

In his detailed SWOT analysis, Dhawan [

19] explored the multifaceted nature of Digital Learning, leveraging diverse sources such as journals, reports, and digital content to identify its strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats. This rigorous analysis revealed that Digital Learning provides substantial flexibility in terms of timing, which accommodates individual learners’ schedules and enhances accessibility [

20]. Furthermore, it promotes the structuring of knowledge through advanced pedagogical techniques and the innovative use of digital tools, which fosters essential social and collaborative skills among learners [

16,

21].

Digital Learning also augments the adaptation of teaching methodologies, encouraging active participation and self-reliance among students [

17,

22]. The platforms extend educational opportunities globally, making higher education accessible to a broader audience, regardless of geographical constraints [

20,

23]. The environments supported by Digital Learning tools such as multimedia items, forums, and videoconferencing, cater to various learning styles, thereby enhancing the educational experience and outcomes [

23].

However, the weaknesses associated with Digital Learning include recurring technical issues that disrupt the educational flow and a lack of personal interaction, which often leads to lower emotional and social engagement between instructors and students [

19]. These challenges are compounded by the potential for increased anxiety, frustration, and confusion among learners, further exacerbated by disparities in access to the necessary technological infrastructure [

20].

The opportunities presented by Digital Learning are vast, including the potential for innovation in educational practices and the development of flexible, customizable learning plans. These platforms also enable the professional growth of educators, equipping them with the skills necessary to navigate and optimize the use of emerging technologies in their teaching [

19].

Conversely, the threats include the risk of overdependence on technology, which can lead to significant disruptions, and the ongoing challenge of unequal access to digital resources, which can exacerbate educational inequities. Additionally, implementing Digital Learning encounters several barriers, such as the complexities of managing online interactions and the need for extensive adjustments in pedagogical strategies to effectively integrate techno-pedagogic tools [

24,

25].

Further complicating this landscape are the first-order barriers related to external factors, such as time constraints and a lack of technological proficiency, alongside second-order barriers stemming from restrictive attitudes towards the use of technology in education [

17,

26,

27,

28,

29].

The dual nature of Digital Learning, as revealed through this extensive literature review, highlights its transformative potential, alongside significant challenges that must be navigated. These insights into the strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats of Digital Learning inform the subsequent research questions in this study, which seek to delve deeper into the specific experiences of lecturers in terms of Digital Learning implementation. By critically examining these aspects, the study aims to contribute nuanced understanding to the ongoing discourse on Digital Learning within higher educational contexts.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

This investigation employed a qualitative research design, specifically implementing a phenomenological approach, as delineated by Creswell [

30] and Moustakas [

31]. This methodology was chosen for its emphasis on describing the lived experience of individuals, in this case, lecturers’ experiences with Digital Learning integration. We chose the phenomenological approach over other qualitative methods because it allows for a deep exploration of the subjective experiences and perceptions of lecturers, capturing the essence of their transition to Digital Learning. This approach is particularly suited to understanding the complex interplay between individual experiences, the cultural context, and institutional factors, in the adoption of new educational technologies.

The phenomenological approach allowed us to capture the essence of these experiences, focusing on perceptions, challenges, and adaptations. Data collection involved semi-structured, in-depth interviews with 15 lecturers, each lasting approximately 60 min. Interviews were audio recorded, transcribed verbatim, and analyzed using thematic content analysis techniques outlined by [

32].

In this study, the phenomenological approach allowed us to focus on the ‘lived experiences’ of lecturers as they engaged with Digital Learning tools and environments. We sought to understand not just what happened, but how the participants experienced and made sense of these changes to their teaching practices. This approach was particularly suited to our research questions, as it allowed us to capture the nuanced, subjective experiences of educators navigating the complex landscape of Digital Learning implementation.

We utilized purposive sampling to select fifteen lecturers from a higher education institution in northern Israel, chosen for their extensive experience with digital teaching methods and diverse academic backgrounds. This purposive sampling approach is supported by research on qualitative methodologies in educational contexts [

33], which emphasizes the importance of selecting information-rich cases for in-depth study. In the context of Digital Learning research, this method allows for the exploration of diverse experiences and perspectives among lecturers who have directly engaged with digital teaching methods [

30].

These participants, ranging in age from 36 to 74 and holding positions from senior lecturer to associate professor, provided a comprehensive view of the integration of digital pedagogy across various disciplines. Each had previously implemented at least one digitally integrated course, ensuring a depth of practical insights into the challenges and dynamics of Digital Learning. This approach is supported by the work of Ter Beek et al. [

6], who highlight the importance of continuous professional development for lecturers to effectively integrate technology into their teaching practices.

Recruitment was based on convenience sampling, targeting accessible lecturers who met the following criteria: (1) currently teaching at the institution, (2) having implemented at least one digitally integrated course, and (3) a willingness to participate in an in-depth interview about their experiences with Digital Learning. This approach facilitated a representative cross-section of the lecturers’ experiences with digital education. This sampling approach yielded a diverse group of participants, whose characteristics are detailed below.

Participants included lecturers serving as digital pedagogy trustees and others actively involved in delivering digitally enhanced courses. This mix enriched the study with varied perspectives on both the strategic implementation and day-to-day application of Digital Learning tools. Recruitment was based on convenience, targeting accessible lecturers who met the study’s criteria, which facilitated a representative cross-section of the lecturers’ experiences with digital education.

Ethical standards were rigorously maintained by assigning pseudonyms to all participants to ensure confidentiality and foster open communication. The study included 15 lecturers, comprising 3 males and 12 females. While this gender distribution does not represent a perfect balance, it reflects the current composition of the lecturers at the institution. This gender imbalance was considered during data analysis to ensure that perspectives from both genders were adequately represented in the findings.

In terms of academic rank, the participants included 9 senior lecturers, 3 associate professors, and 3 lecturers. This distribution highlights a significant presence of senior lecturers, who made up 60% of the participants, while associate professors and lecturers each represented 20%.

The participants taught in various academic programs, including communication, multidisciplinary social sciences, health systems administration, education, psychology, nursing, human services, organizational development, counseling, public administration, and policy. This diversity in teaching fields adds a broad perspective to the study.

The length of academic teaching experience among participants ranged from 6 to 30 years, with an average experience of approximately 16.6 years. Specifically, 18.75% of the participants had less than 10 years of teaching experience, 31.25% had between 10 and 15 years, and 50% had more than 15 years of experience. This range of teaching experience allowed us to explore how educators at different career stages engaged with digital pedagogy. We found that years of general teaching experience did not necessarily correlate with digital pedagogy proficiency, which we discuss further in the results section.

Regarding their experience with Digital Learning prior to COVID-19, 56.25% of the participants had already integrated Digital Learning into their curricula, while 43.75% had not. This variation in prior experience with Digital Learning underscores the diverse readiness and adaptability of lecturers to incorporate digital tools into their teaching.

Table 1 shows this detailed characterization of the participants, including their gender, academic rank, teaching programs, length of teaching experience, and prior experience with Digital Learning, provides essential context to their perspectives and contributions to this study.

2.2. Data Collection and Data Analysis

Employing a qualitative research design, this study explored the nuanced ethical considerations and lecturers’ interpretations of Digital Learning through thematic analysis.

This study employed a qualitative research design, specifically utilizing a phenomenological approach, as outlined by [

30,

31]. This methodology was chosen for its emphasis on describing the lived experience of individuals, in this case, lecturers’ experiences of Digital Learning integration. The phenomenological approach allowed us to capture the essence of these experiences, focusing on perceptions, challenges, and adaptations.

Participants were recruited through purposive sampling, targeting lecturers with experience in Digital Learning implementation. We continued recruiting and interviewing until data saturation was reached, which occurred after 15 interviews, when no new themes or insights emerged. To ensure the trustworthiness of our findings, we employed member checking, where participants were invited to review and confirm the accuracy of their interview transcripts and our initial interpretations. Additionally, we engaged in peer debriefing sessions with colleagues not involved in the study to challenge our assumptions and interpretations of the data.

Data collection involved semi-structured, in-depth interviews, each lasting approximately 60 min. These interviews were designed to elicit detailed insights into lecturers’ attitudes and perceptions toward Digital Learning programs. All interviews were audio recorded and transcribed verbatim to ensure accurate representation of participants’ views.

The transcriptions were analyzed using thematic content analysis techniques outlined by [

32]. This method involves a six-phase process: familiarization with the data, the generation of initial codes, searching for themes, reviewing themes, defining and naming themes, and producing the report.

Our thematic content analysis involved a detailed, iterative approach to data analysis. In the familiarization phase, we immersed ourselves in the data through repeated reading of interview transcripts, noting initial ideas. During the coding phase, we systematically identified and labeled relevant features of the data. The theme development phase involved collating codes into potential themes, which were then reviewed and refined. We defined and named themes to capture the essence of each, and finally selected compelling extract examples to illustrate our findings. This rigorous process ensured a comprehensive and nuanced understanding of the data, grounded in the participants’ own words and experiences.

To ensure the reliability of our findings, two researchers independently coded the data and then compared their analyses. Any discrepancies were discussed and resolved through consensus. This process of investigator triangulation enhanced the credibility and dependability of our results.

Ethical considerations were paramount throughout the study. All participants provided informed consent and their identities were protected through the use of pseudonyms. The data were stored securely and accessed only by the research team. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at the research team’s institution.

This rigorous approach ensured a comprehensive and nuanced understanding of the data.

This study was conducted in accordance with the ethical guidelines for research involving human subjects. Prior to data collection, the research protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board at the authors’ institution. All participants were provided with detailed information about the study’s purpose, procedures, and potential risks and benefits. Written informed consent was obtained from each participant before the interview took place. To ensure anonymity, all identifying information was removed from the transcripts and pseudonyms were used in reporting the findings. The data were stored securely on password-protected devices, accessible only to the research team. Participants were informed of their right to withdraw from the study at any time without consequence.

4. Discussion

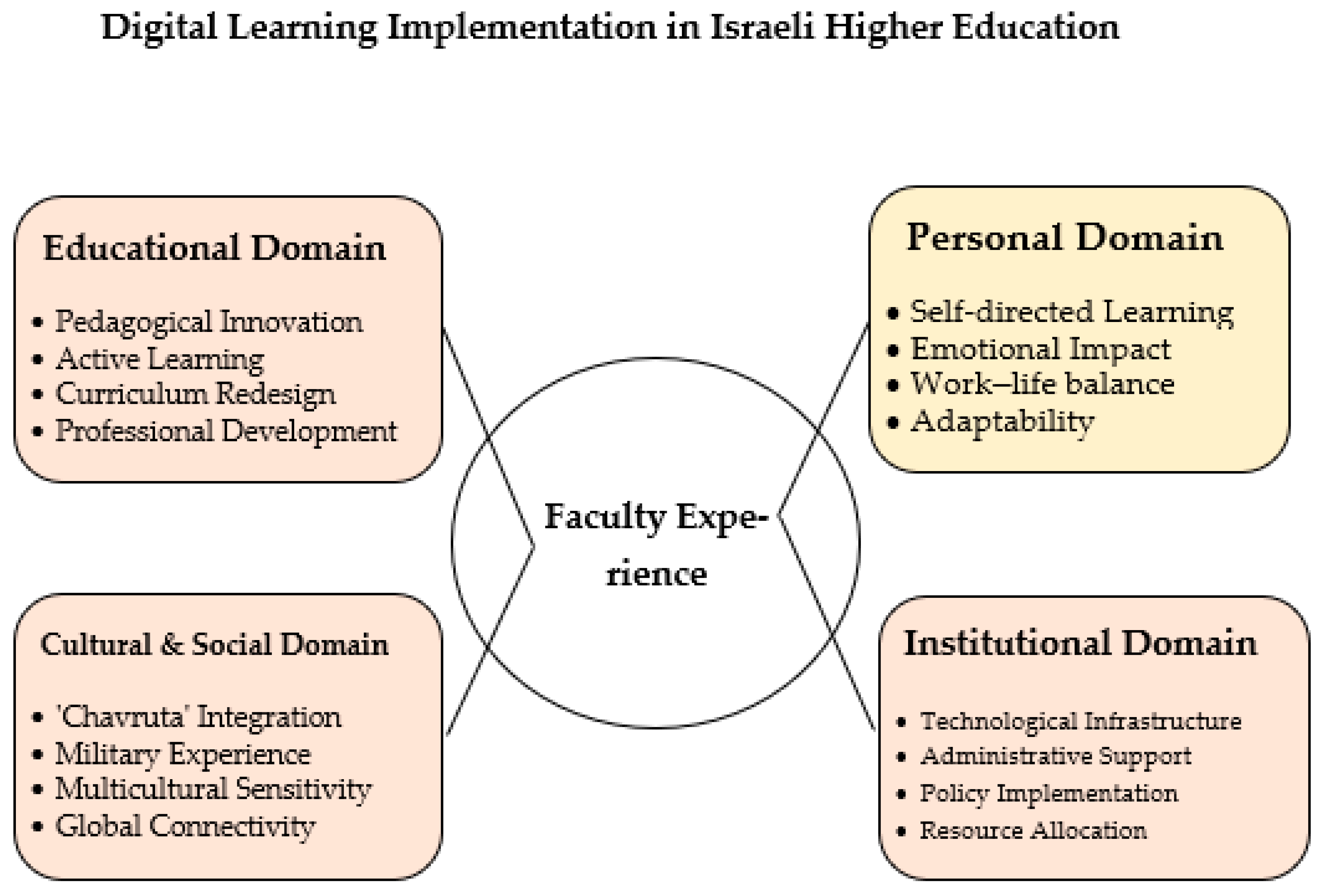

This study provides a nuanced exploration of lecturers’ experiences in terms of the Digital Learning initiative implemented by the CHE and the PBC in Israel. By examining the perspectives of educators at a higher education institution in northern Israel, our findings offer unique insights into the complexities of integrating Digital Learning in a specific national and institutional context. Our results not only support and extend the existing literature on Digital Learning implementation in higher education, but also challenge some prevailing assumptions in the field. We identified four key domains that shape lecturers’ experiences with Digital Learning: educational, personal, cultural and social, and institutional (see

Figure 1). These domains interact in complex ways, influencing the adoption and effectiveness of Digital Learning strategies. Our analysis demonstrates that successful Digital Learning implementation requires not only the integration of technological, pedagogical, and content knowledge domains, as suggested by the TPACK framework [

34], but also a nuanced understanding of the cultural and institutional landscape.

This study’s distinctive contribution resides in its nuanced exploration of the intricate interplay between technological adaptation and cultural considerations within the context of Israeli higher education. Unlike many global studies on Digital Learning, our research highlights how specific cultural elements, such as the tradition of ‘chavruta’ and the integration of military service experiences, shape the implementation of and reception to Digital Learning strategies.

Our analysis reveals that the implementation of Digital Learning in Israeli higher education is a nuanced process influenced by these interconnected domains. As illustrated in

Figure 1, the educational domain highlights the need for pedagogical innovation and curriculum redesign. Simultaneously, the cultural and social domain underscores unique aspects of the Israeli context, such as the integration of ‘chavruta’ learning traditions and the influence of military service experiences. The personal domain captures the impact on lecturers’ work–life balance and emotional well-being, while the institutional domain emphasizes the critical role of organizational support and infrastructure. These findings collectively underscore the need for a culturally responsive approach to Digital Learning implementation, one that acknowledges and leverages the unique characteristics of the Israeli educational landscape.

In line with previous research by Bond et al. [

13] and Castro and Tumibay [

14], we found that digital tools can significantly enhance student engagement and active learning, when implemented effectively. However, our study goes further by illuminating the specific strategies educators employ to achieve this engagement in diverse disciplines, from nursing simulations to the use of collaborative online whiteboards in psychology courses.

As illustrated in the educational domain of our model (

Figure 1), the implementation of Digital Learning necessitates significant changes to teaching methodologies and course design. Our findings highlight how lecturers, like participants S1 and A1, had to fundamentally rethink their approaches to both content delivery and assessment.

Our findings align with Bond et al.’s [

13] systematic review, which emphasized the importance of how digital tools are implemented. However, our study extends this understanding by highlighting the unique cultural considerations in the Israeli context, such as the integration of ‘chavruta’ learning traditions into digital platforms. This cultural adaptation of Digital Learning strategies offers a new perspective on enhancing student engagement in diverse educational settings.

Ter Beek et al. [

6] emphasize the need for continuous professional development to ensure that lecturers can effectively integrate these technologies into their teaching practices. They argue that technological innovations are essential for preparing students and lecturers for future labor market demands. This underscores the importance of providing ongoing training and support to lecturers as they navigate the complexities of Digital Learning environments.

Moreover, our research challenges the notion that technological barriers are the primary obstacle to effective Digital Learning implementation. While these barriers do exist, our findings suggest that cultural and pedagogical factors play an equally, if not more, significant role. The need to adapt teaching methods to diverse cultural backgrounds and integrate unique experiences, such as military service, into the Digital Learning environment emerged as critical considerations not widely discussed in previous literature.

The personal domain in our model (

Figure 1) captures the profound effects of Digital Learning on lecturers’ work–life balance and emotional well-being. The transition to digital teaching often blurred the line between the lecturer’s professional and personal life, requiring new strategies for time management and self-care.

This study makes several unique contributions to the field of Digital Learning in higher education. Firstly, it provides insights into the specific challenges and opportunities of implementing Digital Learning in the Israeli higher education context, a perspective that has been underrepresented in the literature. For instance, our findings on the integration of ‘chavruta’ learning traditions into digital platforms offer a novel approach to maintaining cultural educational practices in a digital environment. Secondly, our study reveals how the diverse student population in Israel, including Arab Israeli and ultra-Orthodox students, necessitates careful consideration of cultural sensitivities in terms of the digital content and communication methods used. This highlights the importance of culturally responsive Digital Learning strategies in diverse societies. Lastly, our findings on the integration of military service experiences into educational approaches provide a unique perspective on leveraging students’ prior experiences in Digital Learning environments, an aspect not widely discussed in previous literature.

These insights have several practical implications for higher education institutions and policymakers, as follows:

Professional development: There is a clear need for ongoing, discipline-specific professional development that goes beyond basic technological skills to address pedagogical strategies for digital engagement;

Cultural sensitivity: Institutions should develop guidelines for creating culturally responsive Digital Learning environments, particularly in diverse societies like Israel;

Flexible implementation: Given the varied experiences and challenges reported by lecturers, a one-size-fits-all approach to Digital Learning is unlikely to succeed. Institutions should provide flexibility for educators to adapt digital tools to their specific disciplinary and pedagogical needs;

Infrastructure investment: While not the only barrier, technological infrastructure remains crucial. Institutions and policymakers should prioritize equitable access to reliable internet and appropriate devices for all students and lecturers.

Our analysis highlights several key themes that contribute new understanding to the field of Digital Learning in higher education, as follows:

Context-specific challenges: Unlike broader studies on Digital Learning, our research illuminates the particular challenges faced by Israeli educators in adapting to new digital pedagogies. For instance, the rapid transition to Digital Learning during the COVID-19 pandemic exposed infrastructural disparities among different regions and socioeconomic groups in Israel. Our model’s cultural and social domain (

Figure 1) emphasizes the distinctive features of Digital Learning implementation in the Israeli higher education context. The integration of ‘chavruta’ learning traditions into digital platforms and the leveraging of students’ military experiences in online collaborative projects demonstrate how cultural practices can be preserved and enhanced through technology.

However, this domain also highlighted significant socioeconomic challenges. Participant D1, noted: “We found that students from peripheral areas and lower socioeconomic backgrounds often struggled with reliable internet access and appropriate devices, which affected their ability to participate fully in online learning”. This observation underscores how Digital Learning can potentially exacerbate existing social inequalities, a critical consideration in a diverse society like Israel.

Moreover, the multicultural nature of Israeli society presented unique challenges. Participant Z1 observed: “We had to be particularly sensitive to the diverse cultural backgrounds of our students, especially when designing group activities or selecting case studies. What works for one cultural group might not be as effective for another”.

The integration of military service experiences into educational approaches also emerged as a distinctive factor. Participant E1, explained: “Many of our students come with military leadership experience. We had to find ways to leverage this in our Digital Learning environment, which led to some innovative peer-mentoring initiatives”. Participant A3, elaborated on how she incorporated the concept of ‘chavruta’ (traditional Israeli paired learning) into her online courses: “I created virtual ‘chavruta rooms’ where pairs of students could engage in deep, collaborative learning sessions. This not only preserved a valued cultural practice but also enhanced peer-to-peer learning in the digital space”. Additionally, participant Z1, shared: “We developed a series of digital case studies that reflected the diverse backgrounds of our students—Arab, Jewish, Druze, and others. This approach helped students relate the course material to their own cultural contexts, even in a virtual setting”;

Innovative adaptations: The lecturers in our study demonstrated unique approaches to overcoming barriers, such as creating virtual ‘lab kits’ for at-home experiments, developing AI-powered chatbots for counseling practice, and establishing international virtual collaborations for simulating real-world scenarios. These creative solutions not only addressed immediate challenges, but also often enhanced the learning experience beyond traditional classroom limitations;

Cultural considerations: Our findings reveal how cultural factors specific to the Israeli higher education system influence the adoption of Digital Learning, including the emphasis on collaborative learning in Israeli educational traditions, the integration of military service experiences into educational approaches, and the multicultural nature of Israeli society. For example, several participants noted how the tradition of ‘chavruta’ (partnered learning) in Israeli education influenced their approach to designing online collaborative activities. Additionally, the diverse student population, including Arab Israeli and ultra-Orthodox students, necessitated careful consideration of cultural sensitivities in terms of the digital content and communication methods used.

4.1. Contextualizing Digital Learning within Global Trends

Digital Learning is not unique to Israel but is part of a global shift towards integrating technology into education. This trend has been accelerated by technological advancements and a growing recognition of the need for educational systems to meet the demands of the 21st century workforce. By situating the CHE and PBC’s initiative within this broader context, it is evident that while the motivations are aligned with global educational trends, the specific challenges faced by Israeli institutions also mirror those encountered internationally. This global perspective is crucial for understanding the potential and limitations of Digital Learning reforms.

4.2. Challenges to Digital Learning

The study identified significant pedagogical and perceptual challenges.

4.2.1. Pedagogical Challenges

Lecturers are required to undertake substantial redesigns of their courses to accommodate Digital Learning. This involves not only technological integration, but also pedagogical adjustments to ensure that digital tools are effectively enhancing learning outcomes. Such challenges are consistent with the findings from international studies [

24,

35], which highlight the global nature of these pedagogical adjustments in digital education.

Our findings align with and extend the work of Koehler and Mishra [

34] on the Technological Pedagogical Content Knowledge (TPACK) framework, demonstrating how educators in the Israeli context navigate the complex intersection of content, pedagogy, and technology.

Building on this foundation, our study extends existing theoretical frameworks in significant ways. Our findings both support and extend the existing models of Digital Learning implementation. While our results align with the TPACK framework in emphasizing the interaction between technological, pedagogical, and content knowledge, they also highlight the critical role of cultural and institutional factors in shaping this interaction. This extends the TPACK model by situating it within a broader sociocultural context.

Furthermore, our findings challenge the technology acceptance model (TAM) by demonstrating that factors beyond perceived usefulness and ease of use, such as cultural traditions and institutional support, play crucial roles in the adoption of Digital Learning technologies.

4.2.2. Perceptual Challenges

The role of the educator is undergoing a transformation, as evidenced by our findings. While some lecturers, like participant Z1, noted that “

Digital Learning allows much more active participation by students,

others expressed concerns about the shift from synchronous to asynchronous teaching”. This aligns with Dhawan’s [

19] observation that Digital Learning can lead to lower emotional and social engagement between instructors and students. The transition raises fundamental questions about the nature of teaching and the role of direct instruction in student learning, echoing the challenges identified by [

17] regarding teachers’ pedagogical beliefs and technology use. König et al. [

36] further highlight that this transformation requires educators to rapidly adapt their competencies, particularly in the areas of digital instruction and student support in online environments.

4.3. Barriers to Implementing Digital Learning

The barriers identified are multidimensional.

4.3.1. Pedagogic Barriers

Echoing the findings in the literature on educational technology integration [

26,

27,

28], lecturers face substantial burdens in redesigning courses for digital platforms, often leading to burnout. These challenges are exacerbated by institutional pressures and the rapid pace of technological change.

4.3.2. Barriers to Interpersonal Relations

Dhawan [

19] notes that Digital Learning can reduce the richness of interactions that characterize the traditional classroom setting. The lack of face-to-face communication can detract from the relational dynamics essential for effective teaching and learning.

4.3.3. Technological Barriers

The dependence on stable and continuous technological support is a significant concern, as any malfunction can disrupt the educational process. This dependency highlights the need for robust IT infrastructure that is not only responsive but also preemptive in regard to addressing potential issues.

4.3.4. Emotional Barriers

The shift to digital teaching has significant emotional implications for lecturers, including leading to feelings of isolation and frustration due to reduced student interaction and increased administrative tasks.

4.4. Opportunities Created by Digital Learning

Despite these challenges, Digital Learning offers substantial opportunities.

4.4.1. Enhancing Educational Practices

The ability of digital tools to facilitate personalized learning paths and flexible access to educational resources is a significant advantage, enabling a more learner-centered approach [

21,

37].

4.4.2. Innovating Teaching Methods

The integration of multimedia and interactive resources can make learning more engaging and responsive to diverse learning styles.

4.4.3. Developing 21st Century Skills

Digital Learning environments are ideal for fostering essential skills, such as critical thinking, collaboration, and digital literacy, preparing students for success in a highly interconnected and technologically advanced global economy [

16].

The findings from this research highlight that while Digital Learning presents numerous opportunities for advancing education, it also poses significant challenges that require careful consideration and strategic action. As the CHE and PBC continue to advance Digital Learning initiatives, it is imperative that these efforts are supported by robust research, thoughtful policymaking, and a commitment to addressing the multifaceted needs of both educators and learners.

This study contributes significant new knowledge to the field of Digital Learning in higher education, particularly in the Israeli context, while also offering insights applicable to broader global contexts. Our findings extend existing theoretical frameworks and challenge prevailing assumptions in several key ways, as follows:

Extending the TPACK framework: While our results align with the Technological Pedagogical Content Knowledge (TPACK) framework [

34] in emphasizing the interaction between technological, pedagogical, and content knowledge, they also highlight the critical role of cultural and institutional factors in shaping this interaction. This extends the TPACK model by situating it within a broader sociocultural context;

Challenging the technology acceptance model (TAM): Our findings suggest that factors beyond perceived usefulness and ease of use, such as cultural traditions and institutional support, play crucial roles in the adoption of Digital Learning technologies. This challenges the simplicity of traditional technology acceptance models and calls for more nuanced, context-specific approaches;

Cultural adaptation of Digital Learning: The innovative approaches developed by lecturers in response to challenges such as infrastructural disparities, multicultural student bodies, and the integration of military experiences into education, demonstrate how Digital Learning can be adapted to specific cultural contexts. This contributes to the growing body of literature on culturally responsive digital pedagogy;

Institutional role in digital transformation: Our study underscores the critical role of institutional support and infrastructure in successful Digital Learning implementation, extending beyond mere technology provision to include pedagogical support and policy alignment.

These theoretical contributions have significant practical implications for higher education institutions globally, particularly those in diverse cultural contexts or undergoing rapid digital transformation.

The unique contributions of this study to the broader field of Digital Learning in higher education are multifaceted. Firstly, by examining the implementation of Digital Learning in the culturally diverse context of Israeli higher education, our research provides valuable insights into how cultural factors shape the adoption and effectiveness of educational technologies. The adaptation of traditional practices like ‘chavruta’ (paired learning) to digital platforms demonstrates how cultural heritage can be preserved and even enhanced through the thoughtful integration of technology. This finding has implications for other multicultural educational settings, suggesting that successful Digital Learning strategies should be culturally responsive and adaptive.

Secondly, our study highlights the importance of considering the unique experiences and backgrounds of students in Digital Learning environments. The integration of military service experiences into educational approaches, for instance, offers a novel perspective on leveraging diverse life experiences in digital pedagogy. This insight could be particularly relevant for countries with compulsory military service or those with a significant veteran student population.

Lastly, our research underscores the critical role of institutional support and policy alignment in successful Digital Learning implementation. The challenges faced by Israeli institutions in balancing technological innovation with cultural preservation and addressing socioeconomic disparities in terms of access to digital resources are likely to resonate with higher education systems worldwide. Our findings suggest that a holistic approach, considering technological, pedagogical, cultural, and institutional factors, is crucial for effective Digital Learning implementation in diverse educational contexts.

As our model (

Figure 1) illustrates, these four domains, educational, personal, cultural and social, and institutional, are deeply interconnected. For instance, the pedagogical innovations in the educational domain often require institutional support (institutional domain) and are shaped by cultural practices (cultural and social domain), while also impacting lecturers’ personal experiences (personal domain).

Ter Beek et al. [

6] suggest that continuous professional development is essential for lecturers to effectively integrate technology into their teaching practices and that this should be a focus of future initiatives. Additionally, future research should explore the long-term impacts of sustained Digital Learning integration on student outcomes, lecturers’ job satisfaction, and institutional effectiveness. Comparative studies across different national contexts could further illuminate the role of cultural and societal factors in shaping Digital Learning experiences.

Furthermore, our research underscores the importance of considering local and cultural factors when implementing Digital Learning initiatives. The adaptation of traditional learning methods like ‘chavruta’ to digital platforms demonstrates how cultural practices can be preserved and enhanced through technology. These insights can inform policymakers and educational leaders in designing more culturally responsive and effective Digital Learning strategies.

By examining the specific experiences of Israeli educators, this study also sheds light on the broader implications of rapid digital transformation in higher education. It emphasizes the need for flexible, context-specific approaches to Digital Learning that can accommodate diverse student populations needs, and cultures, while leveraging the unique strengths of local educational traditions

This study emphasizes the critical need for strategic planning and robust support at both institutional and national levels to effectively address the barriers to Digital Learning.

5. Conclusions

This research offers substantive contributions to the discourse on Digital Learning in higher education, with particular emphasis on the Israeli context. Our findings not only illuminate the unique challenges and opportunities within the Israeli higher education system, but also provide valuable insights for the global educational community grappling with the complexities of digital transformation in diverse cultural settings.

The key findings are as follows:

Context-specific implementation: This study reveals the nuanced interplay between technological, pedagogical, and cultural factors in Israeli higher education;

Innovative engagement strategies: Educators developed creative approaches to enhance student engagement across various disciplines in digital environments;

Cultural integration: The successful adaptation of traditional practices like ‘chavruta’ into digital platforms demonstrates how cultural heritage can enhance educational technology adoption;

Transition challenges: This study identifies specific obstacles faced by educators, including the need for new pedagogical approaches and skills.

While focused on Israel, this research offers valuable insights for global higher education institutions facing digital transformation challenges in diverse societal contexts. The strategies developed by Israeli educators for addressing cultural, technological, and pedagogical challenges can serve as a model for other countries navigating similar transitions.

Based on these findings, we propose the following recommendations for higher education institutions and policymakers:

Develop comprehensive, ongoing professional development programs that address not only technological skills, but also pedagogical strategies for effective digital teaching. These programs should be discipline specific and culturally sensitive;

Create guidelines for culturally responsive Digital Learning environments. This includes adapting traditional educational practices (like ‘chavruta’ in the Israeli context) to digital platforms and considering diverse student backgrounds in regard to content creation and delivery;

Invest in flexible technological infrastructure that can support a variety of Digital Learning approaches. This should include provisions for students from diverse socioeconomic backgrounds to ensure equitable access;

Foster communities of practice among educators to share experiences, strategies, and innovations in digital teaching. This could include cross-institutional and international collaborations;

Regularly assess and adapt Digital Learning initiatives based on feedback from all stakeholders, including students, lecturers, and administrative staff;

Develop policies that recognize and reward lecturers’ efforts in digital innovation and pedagogy, integrating these into promotion and tenure considerations;

Collaborate with industry partners to ensure that Digital Learning strategies align with evolving workforce needs, particularly in rapidly changing fields.

The implementation of these recommendations should be tailored to the specific context of each institution, considering its unique cultural, social, and institutional characteristics.

This study underscores the critical importance of considering local cultural contexts in the implementation of Digital Learning strategies. By adapting educational technologies to align with cultural traditions and societal needs, institutions can create more effective and inclusive Digital Learning environments. Our findings highlight that successful Digital Learning integration goes beyond mere technological adoption; it requires a nuanced understanding of the interplay between educational practices, personal experiences, cultural norms, and institutional structures. As higher education continues to evolve in the digital age, such culturally responsive and holistic approaches will be crucial in preparing students for the complex challenges of the 21st century workforce. Furthermore, our research suggests that the lessons learned from the Israeli context, particularly in balancing technological innovation with cultural preservation, may offer valuable insights for other diverse educational systems globally.

Beyond the Israeli context, this study has broader implications for the field of higher education globally. It underscores the importance of considering local cultural and institutional factors in the implementation of Digital Learning initiatives. As higher education institutions worldwide grapple with the challenges and opportunities of digital transformation, our findings suggest that a one-size-fits-all approach is unlikely to succeed. Instead, institutions should strive to develop flexible, culturally responsive strategies that can be adapted to diverse educational contexts.

The long-term impacts of this Digital Learning transition in higher education are likely to be profound and far reaching. As institutions adapt to these new modes of teaching and learning, we may see a fundamental shift in the nature of higher education itself. This could lead to more flexible, personalized learning experiences, increased global collaboration in education, and a redefinition of the role of educators. However, it will be crucial to continually assess and address issues of equity, accessibility, and the quality of education in this evolving landscape.

While our study focused on the Israeli context, many of our findings may be transferable to other settings, particularly in countries with diverse populations and rapidly advancing technological infrastructure. However, we acknowledge that the specific cultural and institutional factors in Israel may limit the direct applicability of some findings to other contexts. Future research in diverse settings will be crucial to building a comprehensive global understanding of Digital Learning implementation in higher education.

The long-term implications of our findings for higher education policy in Israel and beyond are significant. As institutions continue to integrate Digital Learning, policymakers will need to consider how to balance technological innovation with cultural preservation, ensure equitable access to digital resources, and support lecturers’ ongoing development in terms of digital pedagogy. Future research should explore how these insights can be applied to diverse educational contexts globally, particularly in multicultural societies facing rapid technological change.