1. Introduction

Quality education ensures gender inclusion and equity in participation opportunities and learning for all students, irrespective of their individual characteristics and social background [

1]. This drive to deliver high-quality Physical Education (PE) has been strongly influenced by recommendations from the United Nations 2030 sustainable development goals agenda. Hence, ensuring equity and inclusion are educational concerns explicitly reflected in international PE curricula for elementary and secondary education. Teachers receive guidelines to ‘plan lessons for pupils under equal opportunities’, whereby learners are entitled to ‘fully and effectively participate in all educational settings, demonstrating respect for human and cultural diversity and acting in accordance with human rights principles’, ‘display positive social behaviours, recognising that everyone is equal but unique in his/her own way’ [

2], and learn ‘strategies to interact positively with others’ [

3].

In agreement, in the present study, pursuing equity in PE encompasses the teacher’s commitment to offering tailored pedagogical support to each student, recognising and fostering their unique learning possibilities [

4]. Concurrently, inclusion aims to ensure the full participation of every student in activities pivotal to their holistic development, fostering central involvement and decision-making in personally relevant learning experiences (e.g., deciding what to learn) [

5]. A relevant idea on this matter is that the core mission of academia is to keep pace with societal progress by implementing state-of-the-art and informed teacher education and teaching practices in PE Teacher Education (PETE) and PE [

6]. Therefore, PETE programmes increasingly face the challenge of addressing the following question: how can future teachers (i.e., Pre-Service Teachers; PSTs) be equipped to provide equitable participation and learning opportunities while nurturing students’ pro-social attitudes?

Thus, one of the main aims of this study was to examine the teaching practices of a PST (i.e., the ‘PETE in action’) enrolled in a PETE programme designed deliberately to provide continuous support for PSTs in implementing more inclusive and equitable PE activities. An additional goal was to employ video-based social network analysis to access the evolving patterns of equity and inclusion present in students’ participation across different game-based activities. Insights offered through a mixed-methods approach distinctively integrate crucial process-oriented aspects, allowing us to unveil in greater depth intricate nuances of the practical manifestation (i.e., outcome-oriented) of equity and inclusion. Knowledge about ‘how’ the teacher taught during the teaching-learning process is used to inform the understanding of ‘what’ objective metric manifestations of inclusion and equity emerged during students’ gameplay participation.

How has equity and inclusion been researched and how can social network analysis expand current knowledge?

Although equity and inclusion are complex constructs manifested in the pedagogical and social-interactional dimension of the teaching-learning process (e.g., teachers’ pedagogies and student interactions) [

1], this study of equity and inclusion in student-centred PE has predominantly used qualitative research concerned with teachers’ perspectives of student engagement in game-based activities. For instance, Harvey, Pill [

7] explored teachers’ voices regarding the main successes in students’ learning outcomes related to SCAs, and Baek and Dyson [

8] investigated teachers’ perspectives of student engagement through an equity-based approach for social and emotional learning. In addition, Farias, Hastie and Mesquita [

9] examined students’ progress from peripheral to fuller participation in the teams’ dynamics, decision-making, and gameplay activities. The findings primarily focused on how the social bonding trajectory among students positively influenced their readiness to become active agents and guardians of inclusive social interactions.

Quantitative studies have attempted to capture inclusion and equity in the context of gameplay mainly through assessing the level of student engagement in games. While some quantitative studies have explored individual rates of engagement (the number of game-actions) and on-the-ball participation time, such metrics lack the analytical sensitivity to comprehensively capture equity and inclusion in students’ participation [

10]. For instance, even with active efforts from peers to establish gameplay connections, students might exhibit reduced on-the-ball participation time and gameplay engagement rates, influenced by gameplay dynamics induced by specific game modifications and/or the skill levels of both peers and the opposing team.

In this context, nuanced insights into equity and inclusion necessitate an approach that considers the broader social dynamics during game-based activities to be able to respond to long-standing queries such as ‘Do students interact equitably with all their peers?’ and ‘Are both genders equitably valued during gameplay?’ [

11,

12]. Social network analysis (SNA) emerges as a powerful tool to unravel the intricate social architecture embedded in game-based activities [

13]. By employing SNA, one can represent students’ gameplay networks, transforming them into graphs featuring nodes (representing students) and edges (representing interactions). Through this method, detailed metrics can be computed, offering insights into equity and inclusion within students’ gameplay participation profiles, for instance, discerning whether the connections established between students reflect inclusive interactions across sexes [

14].

Only one study on PE has harnessed SNA techniques, albeit beyond the realm of game-based activity participation, as peer interactions were gathered through questionnaires rather than gameplay data (e.g., ‘state two favourite teammates’) [

15]. By scrutinizing the intricate social networks within game-based activities, this study also aims to unveil the presence of equity and inclusion in students’ gameplay participation. In the context of SNA applied to game-based activities, there are three specially designed metrics that provide objective insights into the presence of equitable and inclusive participation: the clustering coefficient, density, and degree prestige (see Methods) [

13].

A conceptual and empirical rationale for researching equity and inclusion in PETE.

The rationale of this study is grounded on several conceptual and evidence-based premises. Firstly, we argue that social development, as evidenced by student social skills improvements (e.g., empathic communication, cooperative problem-solving, and providing support to less proficient peers), is vital for creating equitable and inclusive learning environments. As social development progresses, students actively embody the promotion of equity and inclusion within their PE learning environments [

16].

Secondly, promoting inclusive and equitable learning contexts heavily relies on the nature of teachers’ pedagogical intervention, which may occur through more explicit or implicit means. Explicit means involve deliberate intervention in content development and task structure. Teachers design and adapt tasks, setting challenging, self-referenced learning goals to meet diverse student needs and ensure individual success [

17]. Explicit means also include inclusion and equity debates as subject matter integrated into the lesson pacing and the active mediation of power relations and social interactions within learning teams (e.g., modelling inclusive and socially responsible peer-teaching dynamics). Implicit means generate learning contexts where constructions of success are broadened, students feel secure about their ‘Self’, the unique combination of skills, interests, and movement-related experiences of each student is valued, and inclusion and equity in participation opportunities are self-determined by students. For example, students take self-regulated action to ensure equitable participation among all teammates during gameplay activities [

16].

Thirdly, student-centred approaches (SCAs), as represented by model-based PE like Sport Education [

18], cooperative learning [

19], or game-based approaches, have the potential to ‘provide meaningful, purposeful, and authentic learning experiences presented and practised by students’ [

20]. The implementation of SCAs in PE aims to a set of foundational student-centred pedagogies that include the active engagement of students in teaching and learning and working in small groups with experiences in games and authentic, challenging, and appropriately modified tasks and with social responsibility by students. These student-centred pedagogies inherently integrate organisational and functional structures particularly prone to equity and inclusion development, such as game-based tasks, persistent team affiliation, collaborative learning and problem-solving, student-led activities, healthy sports culture and competition activities, and role-playing and peer-tutoring activities [

16].

Importantly, an eclectic approach to learning outcomes is implicit in student-centred pedagogies, encompassing physical-motor, cognitive, social, and affective domains. Such a holistic approach expands the range of educational targets made available to teachers. This is what endows it with a student-centric attribute. Simply put, creating equitable contexts becomes more accessible because the broader array of available learning targets (not restricted to physical-motor outcomes) also facilitates setting personalised learning goals and demands according to students’ unique personal interests, strengths, attributes, and learning potential [

1].

Research on students’ participation in student-centred-based PE lessons explicitly concerned about equity and inclusion tends to show positive effects on their feelings of inclusion, belonging, and sense of competence and confidence [

21]. Students feel they participate in equitable learning contexts sustained by an augmented sense of social care, empathy, and responsibility, with empathetic social interactions that express diversity acceptance in the gameplay participation patterns [

22]. Here, students who typically lead the flow of the game (e.g., higher-skilled boys) provide a self-determined contribution to the inclusive gameplay participation of their less-engaged peers [

23].

This is especially crucial, as gender significantly impacts participation rates and engagement in PE activities. Research indicates that boys tend to participate more actively in PE classes compared to girls. For example, Fairclough and Stratton [

24] found that boys were generally more physically active during PE lessons than girls. This disparity is influenced by societal expectations and cultural norms that portray certain sports and physical activities as more appropriate for boys, leading to higher confidence and greater encouragement from peers and teachers for boys to engage in these activities [

25]. Consequently, girls may feel less confident and less encouraged to participate fully, resulting in lower participation rates and reduced engagement in PE settings [

26].

Gender-specific challenges and barriers further exacerbate the inequities in PE participation. Girls often face issues such as a lack of representation in sports traditionally dominated by boys, limited access to resources, and insufficient encouragement from teachers and peers [

27]. These challenges can lead to feelings of exclusion and lower self-esteem among female students. Additionally, the role of gender in shaping peer interactions and social dynamics within PE classes is critical. Boys and girls often form separate social groups, with boys typically dominating competitive and physically demanding activities, while girls might be relegated to less central roles [

26]. This segregation reinforces gender stereotypes and perpetuates unequal power dynamics. Previous studies, such as those by Smith and St Pierre [

28], have highlighted significant gender differences in prestige and influence among peers in PE settings, with boys generally enjoying higher levels of prestige and influence. This dynamic further marginalises girls, limiting their opportunities for meaningful participation and leadership within PE classes.

Fourthly, however, some research also shows that equity and inclusion do not ‘automatically’ emerge from applying student-centred pedagogies in PE lessons [

29]. This aspiration may be hindered by various socio-cultural and contextual factors and even by the very nature of the teaching applied. Namely, (i) dominant students and teachers may perpetuate deep-rooted masculine hegemony or biased, stereotypical, and discriminatory gender perspectives in PE classes (‘girls can’t play sports as well as boys’), (ii) dominant students (typically boys or higher-skilled students) may take over gameplay opportunities, pushing girls and their less proficient peers to more peripheral or segregated gameplay participation [

1], (iii) teachers may apply one-size-fits-all, strongly normative, and comparative-involvement teacher-centred teaching approaches (e.g., girls feel that they have to perform accordingly to the standards set in reference to boy’s performance), and (iv) teachers may put a misplaced emphasis on competition based on biased and negative attributes of the performance sports culture, or (v) teachers may show a lack of ability to design game-based, developmentally appropriate learning tasks.

In short, it is not uncommon that teachers struggle to apply student-centred, equity- and inclusion-oriented PE activities because they are faced with considerable teaching demands when they try to do so [

29]. Teachers need to master diverse knowledge domains (content and pedagogical knowledge) and apply multiple teaching strategies (from more direct and guided instruction to more discovery-based teaching) [

30]. Teachers must also use differentiated instruction, optimise collaborative interactions and goal-setting within teams, apply the appropriate mediation and transfer of decision-making power to the teams, and design appropriate and modified game-based activities [

31]. Therefore, we argue that teachers must proactively enact the educational potential embedded in student-centred pedagogies by deliberately planning and teaching an ‘augmented pedagogical approach’ to equity and inclusion development.

Thus, fifthly, in this study, we embraced the implementation of the evidence-based four-level pedagogical scaffolding framework (see Methods and

Supplementary S3) designed by Farias and Mesquita [

16] for the deliberate teaching of equity and inclusion in PE. Additionally, the aforementioned ‘problematic’ point leads us to advocate for the urgent need to focus pedagogical interventions and research on PETE, specifically when PSTs are placed in schools to teach PE. Indeed, PSTs tend to feel they may not receive proper support from their PETE programmes when they attempt to implement SCAs in schools [

32]. Further, equity- and inclusion-oriented PETE interventions are very scarce [

4] and require careful consideration. PSTs not only need to learn about basic instructional skills but also need to be familiar with student-centred curricula and be able to apply democratic teaching strategies (comprising positive social interactions and developmentally appropriate learning activities).

Finally, team sports games serve as significant arenas for observing equity and inclusion within PE. These games often mirror societal dynamics, acting as ‘microcosms’ where individuals from diverse backgrounds converge to interact and collaborate [

33]. Consequently, they offer insights into patterns of student involvement and the quality of their interactions during gameplay activities [

34]. The interactive and systemic nature of these games leads to the formation of complex social networks among participants, where their engagement is influenced by the actions of their teammates [

13]. For instance, the inclusivity of a less proficient female student’s participation can vary based on her peers’ willingness to engage with every teammate, regardless of sex or skill level. Thus, valuable insights into the equity, fairness, and inclusivity of students’ participation can be uncovered through game observation [

35].

4. Discussion

This investigation delved into the teaching practices of a PST enrolled in a student-centred PETE programme, designed to support more inclusive and equitable PE (i.e., the ‘PETE in action’), and captured the evolving patterns of equity and inclusion present in students’ participation across two game-based units using SNA techniques.

The SNA allowed us to go beyond the individual gameplay rates of involvement (e.g., the ‘game performance assessment instrument’) [

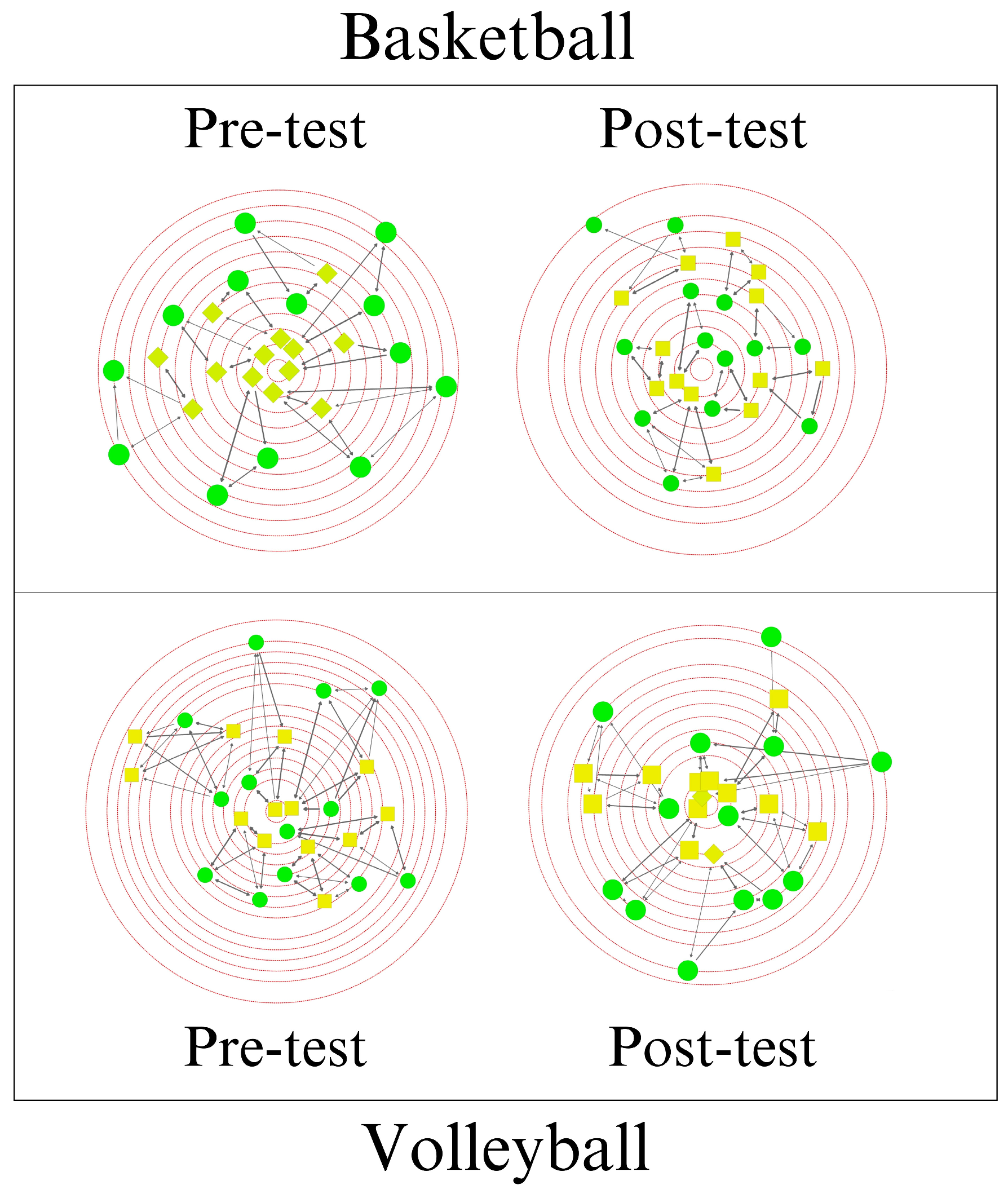

41], expanding our knowledge and answering questions left by previous research. As it is, students interacted equitably with each other during gameplay events (consistently low clustering coefficient values across both units), evidencing inclusive gameplay participation profiles without marked evidence of segregation (both units’ density levels proximity to 1). There was also equity in the value (centrality and prominence) attributed to each sex in the networks of peer interactions (the absence of significant differences between boys’ and girls’ prestige levels).

Two pivotal facets of the PST’s practice emerged, each contributing distinct trends in students’ participation. The initial facet emanated from the PST’s emphasis on equitable content delivery in Basketball. Here, manipulations in learning activities and scaffolding of inclusive team membership fostered an incremental shift towards equitable and inclusive participation. Strategic game-based task adjustments, notably eliminating interception rules, emerged as impactful strategies promoting inclusion for girls and lower-skilled students. This transformation was reflected in both student accounts and more equitable degree prestige levels, signifying the increased influence of girls in their teams.

Simultaneously, the recalibration of rules and scoring systems, particularly valorising lower-skilled students’ interventions, spurred a broader landscape of equitable gameplay interactions. This intentional recognition, exemplified by shots awarded with two points, empowered students to actively foster inclusion, subsequently elevating equity in gameplay networks of peer interaction (e.g., density). Noteworthy is the unique departure from conventional SNA findings [

15], as this study revealed optimal and increasing density levels. The extended time frame of this study (18 weeks) may explain the results. Students’ networks of peer interactions are complex and dynamic systems that require time to shift, urging the employment of longitudinal designs for future research.

In alignment with prior research affirming the positive impact of prolonged team affiliation on social awareness [

22], this study added that the encouragement of persistent team engagement and modelling of inclusive attitudes significantly contributed to students’ positive team membership and group identity, encapsulated in the concept of ‘team spirit’. This was manifested in observable positive cooperation and inclusion in gameplay profiles, evidenced by reduced segregation (lower clustering coefficient).

The second facet of the PST’s practices, witnessed in the Volleyball unit, marked incremental efforts to foster an equitable and inclusive learning context. Peer-teaching, complementary roles, and the celebration of equity and inclusion outcomes elevated students’ autonomy and ownership of the learning experience, establishing a framework for positive peer interactions. However, the evolution of gameplay profiles revealed fewer positive contours throughout the unit, characterised by an increased clustering coefficient. Factors such as diminished task manipulation, the inadequate mediation of role performance, and the limited promotion of novel peer-teaching interactions during designated moments possibly contributed to the development of less equitable and inclusive gameplay profiles. This shift is notably mirrored in an amplified gender gap in prestige levels and decreased density. Another possible explanation may be the less frequent student intervention during gameplay in this unit; for instance, Volleyball’s technical complexity often led to the ball going out of play more frequently, resulting in fewer passes/connections compared to Basketball within the same duration of gameplay. This would directly impact every SNA metric irrespective of the ongoing strategies to include every student in the gameplay.

Despite the less favourable SNA results, the pedagogical strategies in place (e.g., equity supervisor) expanded and diversified students’ participation opportunities (equity), fostering more central participation (inclusion), while also emphasizing the importance of values such as fair play and maintaining positive interactions. Contrary to what some literature suggests, e.g., [

7], these strategies may not necessarily translate into students’ gameplay participation dynamics. The nature of the game itself may play a significant role in determining the participation opportunities afforded to each student and should be accounted for pedagogically (i.e., game-specific strategies). Therefore, future research should not focus exclusively on gameplay indicators, as they may neglect important aspects of equity and inclusion research. Integrating process-oriented analysis with gameplay metrics allowed us to pinpoint the intricate nature of practical representations of equity and inclusion in PE, reinforcing the value of mixed-method approaches.

This study also challenges the mainstream literature notion that PSTs often avoid delegating decision-making to students [

29]. Instead, it highlights a potential oversight wherein, despite decision-making responsibility being transferred, PSTs might lack the necessary skills to actively mediate peer interactions. Pedagogical structures, such as the ‘ethical supervisor’ and ‘peer-tutor’, were in place, but the mediation of inclusive dynamics lagged. For instance, persistent peer-teaching interactions may have unintentionally cemented a preference for working with specific peers, contributing to an increased clustering coefficient (less equitable interactions).

Both facets of the PST intervention especially align with the first and third levels of the student-centred programme’s four-level scaffolding structure (activity- and social-based scaffolding). However, the PST’s practices, although suggesting PETE’s positive impact in his ability and predisposition to deliver more equitable and inclusive PE, also suggest that it may be ambitious to expect PSTs to skilfully support equitable and inclusive learning environments through scaffolding processes, as they might still lack the pedagogical skills to do so, evident in the challenges faced by the PST (e.g., mediating social interactions).

Research suggests that educators’ gender can influence teaching styles and student perceptions, potentially affecting classroom dynamics and learning outcomes [

28]. In considering the potential impact of the PST’s gender and sports activity background on our study, it is hypothesised that these factors may have influenced pedagogical approaches and student outcomes. While the PST’s gender was anonymised to maintain confidentiality and focus on educational practices rather than personal attributes, his experience in the fitness area, characterised by a prescriptive and performance-focused approach, may have shaped his instructional strategies within the PE setting.

Furthermore, the PST’s background in team sports, particularly football, may have played a significant role in shaping the diverse engagement strategies implemented across different teaching units. Each sport presented unique demands and dynamics that necessitated tailored instructional approaches to optimise student participation and learning. For instance, strategies such as modifying game rules or team formations in basketball could have been influenced by the PST’s experience with the dynamics of teamwork and strategic thinking in football. Conversely, in volleyball, where technical complexities may influence student interactions differently, adaptations may have focused on facilitating cooperative learning and mitigating potential barriers to engagement. This rationale underscores the idea that the PST’s previous experiences may have been a lever that contributed to cultivating inclusive learning environments throughout both units. These considerations highlight the nuanced interplay between the PST’s gender, sports background, instructional decisions, and potential student outcomes within the PE context.

Nonetheless, this study empirically adds warnings to the existing literature, emphasizing that the PST’s intentions to foster positive collaboration through student-centred pedagogical structures do not automatically translate into increased equity and inclusiveness in students’ gameplay profiles. Hence, a reflection is prompted on the multifaceted nature of promoting inclusive learning environments. Successful strategies, as observed in Basketball, emphasise the importance and feasibility of intentional game-based adjustments and rule modifications to influence equity and inclusion. On the other hand, the challenges encountered in Volleyball underscore both the complexity and need for more effective mediation of peer interactions and comprehensive assessments of complementary roles to ensure their impact on inclusive participation.