Writing Strategies for Elementary Multilingual Writers: A Systematic Review

Abstract

1. Challenges Faced by Multilingual Learners and Teachers in Writing

2. The Importance of Writing Skills

3. Theoretical Framework

4. The Current Study

Research Question 1: what research has been completed since the inception of the Common Core State Standards [1] about multilingual learners and genre-based writing?

Research Question 2: within this research, what strategies and insights have been identified that can help elementary educators support multilingual students with their development of compositional writing skills?

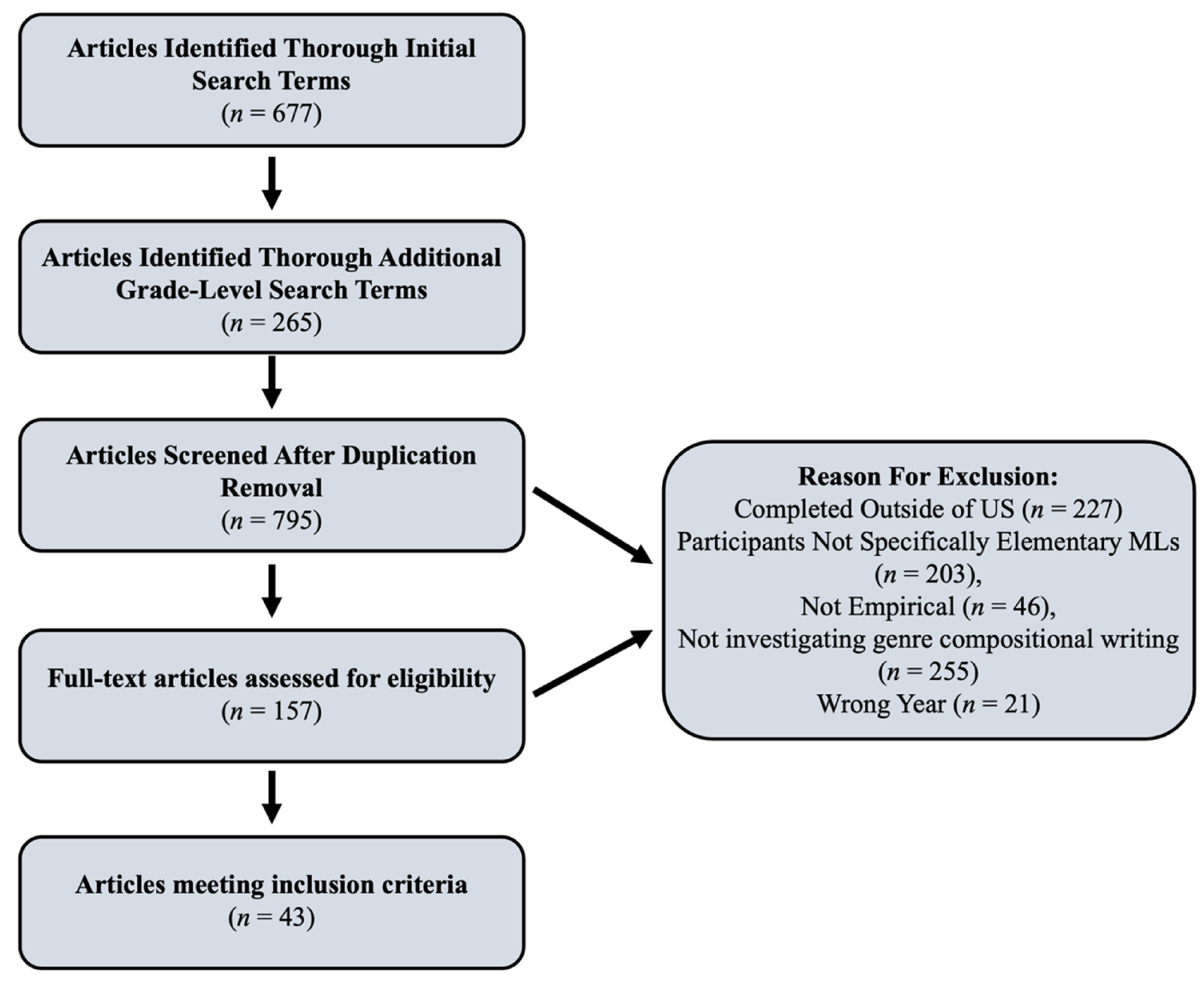

5. Methodological Approach

- be peer-reviewed with original findings and written in English;

- be participants that were multilingual elementary-aged children (K-5);

- be completed in a United States context;

- include data collected between the years 2010 and 2023;

- have multilingual genre-based writing (e.g., opinion/persuasive, informational/expository, or narrative) development as the focus of the study.

Data Extraction and Analysis

6. Findings

6.1. Overview of the Articles

6.2. Role of the Teacher

6.3. Writing Mentor Texts

6.4. Creation of Multimodal Texts

6.5. Writing Scaffolds

6.5.1. Oral Language as a Scaffold

6.5.2. Technology Scaffolds

6.5.3. Targeted Scaffolds

6.6. Authenticity

6.6.1. Authentic Writing Purposes

6.6.2. Outside Worlds: Communities, Families, and Authentic Audiences

6.7. Specific Teacher Instruction

6.8. Multilingual Language Approaches

7. Discussion

8. Future Research

9. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Council of Chief State School Officers (CCSSO); National Governors Association (NGA). Common Core State Standards for English Language Arts & Literacy in History/Social Studies, Science, and Technical Subjects. 2010. Available online: https://learning.ccsso.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/ADA-Compliant-ELA-Standards.pdf (accessed on 25 June 2023).

- Hussar, B.; Zhang, J.; Hein, S.; Wang, K.; Roberts, A.; Cui, J.; Smith, M.; Bullock Mann, F.; Barmer, A.; Dilig, R. The Condition of Education 2020. Available online: https://nces.ed.gov/pubsearch/pubsinfo.asp?pubid=2020144 (accessed on 25 June 2023).

- US Census Bureau. 2020 Census Demographic and Housing Characteristics File (DHC). Available online: https://www.census.gov/library/visualizations/2021/geo/demographicmapviewer.html (accessed on 25 June 2023).

- National Center for Education Statistics. NAEP Writing—2017 Writing Technical Summary. Available online: https://nces.ed.gov/nationsreportcard/writing/2017writing.aspx (accessed on 25 June 2023).

- Cardenas-Hagan, E. Literacy Foundations for English Learners: A Comprehensive Guide to Evidence-Based Instruction; Paul H Brookes Publishing: Brownsville, TX, USA, 2020; ISBN 9781598579659. [Google Scholar]

- Coady, M.; Harper, C.; de Jong, E. From preservice to practice: Mainstream elementary teacher beliefs of preparation and efficacy with English Language Learners in the state of Florida. Biling. Res. J. 2011, 34, 223–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, S.; Sandmel, K. The process writing approach: A meta-analysis. J. Educ. Res. 2011, 104, 396–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salmerón, C. Elementary translanguaging writing pedagogy: A literature review. J. Lit. Res. 2022, 54, 222–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freedman, S.W.; Hull, G.A.; Higgs, J.M.; Booten, K.P. Teaching writing in a digital and global age: Toward access, learning, and development for all. In Handbook of Research on Teaching, 5th ed.; Gitomer, D.H., Bell, C.A., Eds.; American Educational Research Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2016; pp. 1389–1450. ISBN 9780935302486. [Google Scholar]

- Graham, S.; Harris, K.R.; Chambers, A.B. Evidence-based practice in writing education: A review of reviews. In Handbook of Writing Research, 2nd ed.; MacArthur, C.A., Graham, S., Fitzgerald, J., Eds.; Guilford Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2016; ISBN 9781462529315. [Google Scholar]

- Graham, S.; Hebert, M. Writing to read: A meta-analysis of the impact of writing and writing instruction on reading. Harv. Educ. Rev. 2011, 81, 710–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, S.; Kiuhara, S.A.; MacKay, M. The effects of writing on learning in science, social studies, and mathematics: A meta-analysis. Rev. Educ. Res. 2020, 90, 179–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, S. Changing how writing is taught. Rev. Res. Educ. 2019, 43, 277–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grosjean, F. Neurolinguists, beware! The bilingual is not two monolinguals in one person. Brain Lang. 1989, 36, 3–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cummins, J. Linguistic interdependence and the educational development of bilingual children. Rev. Educ. Res. 1979, 49, 222–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- August, D.; Shanahan, T. Developing Literacy in Second-Language Learners: Report of the National Literacy Panel on Language-Minority Children and Youth; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 2006; ISBN 9781315094922. [Google Scholar]

- Genesee, F. Educating English Language Learners: A Synthesis of Research Evidence; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soltero-González, L.; Escamilla, K.; Hopewell, S.W. Changing teachers’ perceptions about the writing abilities of emerging bilingual students: Towards a holistic bilingual perspective on writing assessment. Int. J. Biling. Educ. Biling. 2011, 15, 71–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otheguy, R.; García, O.; Reid, W. Clarifying translanguaging and deconstructing named languages: A perspective from linguistics. Appl. Linguist. Rev. 2015, 6, 281–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, L.; García, O. Not a first language but one repertoire: Translanguaging as a decolonizing project. RELC J. 2022, 53, 313–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nieto, S.; Bode, P. Affirming Diversity: The Sociopolitical Context of Multicultural Education; Pearson: New York, NY, USA, 2017; ISBN 9780134047232. [Google Scholar]

- Padilla, A.M.; Lindholm, K.J.; Chen, A.C.N.; Durán, R.P.; Hakuta, K.; Lambert, W.E.; Tucker, G.R. The English-only movement: Myths, reality, and implications for psychology. Am. Psychol. 1991, 46, 120–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Int. J. Surg. 2021, 88, 105906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cooper, H. Research Synthesis and Meta-Analysis: A Step-by-Step Approach, 5th ed.; SAGE Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2017; ISBN 9781483331157. [Google Scholar]

- Camping, A.; Graham, S.; Ng, C.; Aitken, A.; Wilson, J.M.; Wdowin, J. Writing motivational incentives of middle school emergent bilingual students. Read. Writ. 2020, 33, 2361–2390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adoniou, M. Drawing to support writing development in English Language Learners. Lang. Educ. 2012, 27, 261–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saldaña, J. The Coding Manual for Qualitative Researchers; SAGE Publications Ltd.: London, UK, 2021; ISBN 9781529731743. [Google Scholar]

- Bauer, E.B.; Presiado, V.; Colomer, S. Writing through partnership: Fostering translanguaging in children who are emergent bilinguals. J. Lit. Res. 2016, 49, 10–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durán, L. Audience and young bilingual writers: Building on strengths. J. Lit. Res. 2016, 49, 92–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durán, L. Understanding young children’s everyday biliteracy: “Spontaneous” and “scientific” influences on learning. J. Early Child. Lit. 2017, 18, 71–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durán, L. “Todas las poems que están creative”: Language ideologies, writing and bilingual children. J. Lang. Identity Educ. 2020, 19, 412–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher-Ari, T.R.; Flint, A.S. Writer’s workshop: A (re)constructive pedagogy for English learners and their teachers. Pedagog. Intern. J. 2018, 13, 353–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gebhard, M.; Chen, I.; Britton, L. “Miss, nominalization is a nominalization:” English Language Learners’ use of SFL metalanguage and their literacy practices. Linguist. Educ. 2014, 26, 106–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, H. Exploring the role of intertextuality in promoting young ELL children’s poetry writing and learning: A discourse analytic approach. Classr. Discourse 2017, 9, 166–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machado, E.; Hartman, P. “It took us a long time to go here”: Creating space for young children’s transnationalism in an early writers’ workshop. Read. Res. Q. 2019, 56, 693–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malova, I.; Avalos, M.A.; Gort, M. Teachers’ perceptions of integrated reading-writing instruction for emergent bilinguals. Read. Writ. Q. 2022, 38, 564–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Hallaron, C.L. Supporting fifth-grade ELLs’ argumentative writing development. Writ. Commun. 2014, 31, 304–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Squire, A.; Clark, S.K. Exploring how fourth-grade emerging bilinguals learn to write opinion essays. Lit. Res. Instr. 2019, 59, 53–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sunseri, A.B.; Sunseri, M.A. The write aid for ELLs: The strategies bilingual student teachers use to help their ELL students write effectively. CATESOL J. 2019, 31, 117–131. [Google Scholar]

- Zisselsberger, M. Toward a humanizing pedagogy: Leveling the cultural and linguistic capital in a fifth-grade writing classroom. Biling. Res. J. 2016, 39, 121–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeNicolo, C.P.; González, M.; Morales, S.; Romaní, L. Teaching through testimonio: Accessing community cultural wealth in school. J. Lat. Educ. 2015, 14, 228–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machado, E.; Hartman, P. Translingual writing in a linguistically diverse primary classroom. J. Lit. Res. 2019, 51, 480–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavlak, C.M. “It is hard fun”: Scaffolded biography writing with English learners. Read. Teach. 2013, 66, 405–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarez, A. Drawn and written funds of knowledge: A window into emerging bilingual children’s experiences and social interpretations through their written narratives and drawings. J. Early Child. Lit. 2017, 18, 97–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarez, A.; Butvilofsky, S.A. The biliterate writing development of bilingual first graders. Biling. Res. J. 2021, 44, 189–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Axelrod, Y.; Cole, M.W. ‘The pumpkins are coming…vienen las calabazas…that sounds funny’: Translanguaging practices of young emergent bilinguals. J. Early Child. Lit. 2018, 18, 129–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haines, S.J. Picturing words: Using photographs and fiction to enliven writing for ELL students. Sch. Stud. Educ. 2015, 12, 9–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moses, L. A formative study: Inquiry and informational text with fifth-grade bilinguals. Read. Horiz. 2014, 53, 21–42. [Google Scholar]

- Ramos, L.B.; Musanti, S.I. “I don’t like English because it is jard.” Exploring multimodal writing and translanguaging practices for biliteracy in a dual language classroom. NABE J. Res. Pract. 2021, 11, 32–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowe, L.W. Emergent bilingual students’ translation practices during eBook composing. Biling. Res. J. 2019, 42, 324–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velasco, P.; García, O. Translanguaging and the writing of bilingual learners. Biling. Res. J. 2014, 37, 6–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gort, M. Code-switching patterns in the writing-related talk of young emergent bilinguals. J. Lit. Res. 2012, 44, 45–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, A.; Orosco, M.J.; Wang, H.; Swanson, H.L.; Reed, D.K. Cognition and writing development in early adolescent English learners. J. Educ. Psych. 2022, 114, 1136–1155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arcon, N.; Klein, P.D.; Dombroski, J.D. Effects of dictation, speech to text, and handwriting on the written composition of elementary school English language learners. Read. Writ. Q. 2017, 33, 533–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, A.A.; Lee, S.; Chapman, M.; Wilmes, C. The effects of administration and response modes on grade 1–2 students’ writing performance. TESOL Q. 2019, 53, 482–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowe, L.W. Google Translate and biliterate composing: Second-graders’ use of digital translation tools to support bilingual writing. TESOL Q. 2022, 56, 883–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, D.-S. Web 2.0 tools and academic literacy development in a US urban school: A case study of a second-grade English Language Learner. Lang. Educ. 2013, 28, 68–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooks, J.; Sunseri, A. Leveling the playing field: The efficacy of thinking maps on English Language Learner students’ writing. CATESOL J. 2014, 25, 24–40. [Google Scholar]

- Cuenca-Carlino, Y.; Gozur, M.; Jozwik, S.; Krissinger, E. The impact of Self-Regulated Strategy Development on the writing performance of English learners. Read. Writ. Q. 2017, 34, 248–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silverman, R.D.; Proctor, C.P.; Harring, J.R.; Taylor, K.S.; Johnson, E.; Jones, R.L.; Lee, Y. The effect of a language and literacy intervention on upper elementary bilingual students’ argument writing. Elem. Sch. J. 2021, 122, 208–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiley, A.; McKernan, J. Examining the impact of explicit language instruction in writers workshop on ELL student writing. New Educ. 2016, 13, 160–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Midgette, E.; Philippakos, Z.A. Biliteracy, spelling, and writing: A case study. Lang. Lit. Spect. 2016, 26, 13–30. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Y.-S.G.; Wolters, A.; Mercado, J.; Quinn, J. Crosslinguistic transfer of higher order cognitive skills and their roles in writing for English-Spanish dual language learners. J. Educ. Psych. 2022, 114, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silverman, R.D.; Coker, D.; Proctor, C.P.; Harring, J.; Piantedosi, K.W.; Hartranft, A.M. The relationship between language skills and writing outcomes for linguistically diverse students in upper elementary school. Elem. Sch. J. 2015, 116, 103–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, C.L. Connective use in academic writing by students with language learning disabilities from diverse linguistic backgrounds. Commun. Disord. Q. 2020, 43, 51–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, C.; Schatschneider, C. Examining writing measures and achievement for students of varied language abilities and linguistic backgrounds using structural equation modeling. Read. Writ. Q. 2020, 37, 65–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woolpert, D. Doing more with less: The impact of lexicon on dual-language learners’ writing. Read. Writ. 2016, 29, 1865–1887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escamilla, K.; Butvilofsky, S.; Hopewell, S. What gets lost when English-only writing assessment is used to assess writing proficiency in Spanish-English emerging bilingual learners? Int. Multiling. Res. J. 2017, 12, 221–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopewell, S.; Butvilofsky, S. Privileging bilingualism: Using biliterate writing outcomes to understand emerging bilingual learners’ literacy achievement. Biling. Res. J. 2016, 39, 324–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montanari, S.; Simón-Cereijido, G.; Hartel, A. The development of writing skills in an Italian-English two-way immersion program: Evidence from first through fifth grade. Int. Multiling. Res. J. 2016, 10, 44–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunes, M.J. The five-paragraph essay: Its evolution and roots in theme-writing. Rhetor. Rev. 2013, 32, 295–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraft, M.A.; Blazar, D.; Hogan, D. The effect of teacher coaching on instruction and achievement: A meta-analysis of the causal evidence. Rev. Res. Educ. 2018, 88, 547–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, K.R.; Santangelo, T.; Graham, S. Self-Regulated Strategy Development in writing: Going beyond NLEs to a more balanced approach. Instr. Sci. 2008, 36, 395–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, E.S.; Hancock, C.; Carter, D.R.; Pool, J.L. Self-Regulated Strategy Development as a Tier 2 writing intervention. Interv. Sch. Clin. 2012, 48, 218–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asaro-Saddler, K. Writing instruction and self-regulation for students with autism spectrum disorders. Top Lang. Disord. 2016, 36, 266–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Themes | Description | Example Subcodes | Relevant Studies |

|---|---|---|---|

| Role of the Teacher | Instances within the studies where the teacher played an impactful role in the multilingual learners’ writing development. | teacher’s understanding, responsive to students, facilitate student learning, asset-based perspective, co-construct curriculum with children, encourage bilingual practice, repositioning language beyond English, praise, teacher transformation, resistant, bilingual educator, shared values, modified curriculum | [28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40] |

| Writing Mentor Texts | Instances within the studies where mentor texts were used to impact the multilingual learners’ writing development. | songs, example texts, family poems, bilingual books, children’s literature, previous students’ writing, mentor texts, picture books, “author studies,” explore genre | [28,33,34,35,36,37,40,41,42,43] |

| Creation of Multimodal Texts | Instances within the studies where students used diverse semiotic modes to create texts. | multi-media presentation, pictures, drawings, PowerPoint, photography, color choice, visual composing, design, research posters, text features, advertisements, eBooks, audio recordings | [29,31,33,34,35,40,42,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51] |

| Writing Scaffolds | |||

| Oral Language as a Scaffold | Instances within the studies where oral language skills were used or encouraged to support the multilingual learners’ writing development. | collaboration, oral language skills, “buddy pairs,” talk, requesting help from peer, relying on others, translingual talk, partner talk, oral code switching, discuss vocabulary, brainstorming, sharing of work, feedback discussion | [28,30,32,34,37,38,39,40,46,48,52,53] |

| Technology Scaffolds | Instances within the studies where technology was used to support the multilingual learners’ writing development. | dictation, Google Translate, speech to text, typing, digital writing assessment, blogging, imperfect technology | [38,49,50,54,55,56,57] |

| Targeted Scaffolds | Instances within the studies where a specific scaffold was used to support the multilingual learners’ writing development. | graphic organizer, “Thinking Maps,” writing outline, idea collection, five-part essay structure, sentence frames, writing posters, joint text construction, goal setting | [28,30,33,37,38,39,43,48,50,58,59,60,61] |

| Authenticity | |||

| Authentic Writing Purposes | Instances within the studies where students wrote for authentic and real-world purposes to support their writing development. | pen-pals, letters, topic choice, showcase personal experience, explore emotion, communication, exploration of self, narratives of disruption, address issues, authentic argument | [32,35,37,40,46,47,48,57] |

| Outside Worlds: Communities, Families, and Authentic Audiences | Instances within the studies where students were encouraged to build upon their experiences outside of school settings to support their writing development. | funds of knowledge, older siblings, family literacy contributions, outside writing context, authentic audiences, “real readers,” audience awareness, community cultural wealth, responsiveness, parents, write to family, pets | [29,30,39,41,44,46,56,62] |

| Specific Teacher Instruction | Instances within the studies where specific instruction on a topic or strategy was taught to support the multilinguals’ writing development. | self-regulated strategy development, Integrated Reading and Writing Instruction (IRWI), vocabulary, lexical diversity, writing productivity, small group instruction, phonological awareness | [36,53,59,60,63,64,65,66,67] |

| Multilingual Language Approaches | Instances within the studies where students deployed their full linguistic repertoire to support their writing development. | translanguaging, reluctancy beyond English, deliberate language choice, negotiation of language, bilingual text, translation, need for formal second language instruction, inventive second language spelling, dual language programs, biliteracy assessment | [28,29,30,31,39,40,41,42,44,45,46,49,50,51,53,62,63,68,69,70] |

| Frequency (n) | Percentage (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Methodology | ||

| Quantitative | 11 | 25.58 |

| Qualitative | 28 | 65.11 |

| Mixed | 4 | 9.30 |

| Grade Level | ||

| Kindergarten | 3 | 6.98 |

| First | 6 | 13.95 |

| Second | 6 | 13.95 |

| Third | 5 | 11.63 |

| Fourth | 2 | 4.65 |

| Fifth | 6 | 13.95 |

| Mixed | 15 | 34.88 |

| Genre | ||

| Narrative | 14 | 32.56 |

| Opinion/Persuasion | 9 | 20.93 |

| Informational | 8 | 18.60 |

| Poetry | 3 | 6.98 |

| Multiple | 9 | 20.93 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lewis, B.P. Writing Strategies for Elementary Multilingual Writers: A Systematic Review. Educ. Sci. 2024, 14, 759. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14070759

Lewis BP. Writing Strategies for Elementary Multilingual Writers: A Systematic Review. Education Sciences. 2024; 14(7):759. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14070759

Chicago/Turabian StyleLewis, Bethany P. 2024. "Writing Strategies for Elementary Multilingual Writers: A Systematic Review" Education Sciences 14, no. 7: 759. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14070759

APA StyleLewis, B. P. (2024). Writing Strategies for Elementary Multilingual Writers: A Systematic Review. Education Sciences, 14(7), 759. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14070759