1. Introduction

Autobiographical narratives are personal and reflective accounts that teachers write about their professional, personal, and pedagogical experiences. They can cover a range of topics, from significant professional moments to reflections on teaching practices, classroom challenges, successes, frustrations, and changes over time [

1].

The shared experiences, lessons learned, and perspectives on teaching described in narratives often explore the emotions, values, beliefs, and influences that have shaped a teacher’s approach to teaching and training. Such narratives not only help teachers to reflect on their practice and learn from their own experiences [

2] but can also be a valuable source of learning for other educators, students, researchers, and policy makers [

1].

In a study, Rego [

3], referring to teachers’ autobiographical narratives, states that this act of remembering is an attempt to stop time or to capture a portrait of something lived, while at the same time trying to preserve the mosaic of fragmented emotions and events that appear juxtaposed or faded in the house of the present. This is one of the most valuable premises of autobiographical narrative for teachers themselves, and its formative role for those who write is also recognised and emphasised by other researchers in the field [

4].

As for the readers, Rego [

3] points out that through such narratives, it is also possible to distinguish new perspectives, important parts of the human condition that relate to the inside and the outside, the universal and the local, the general and the specific, the visible and the invisible. This possibility of interpreting the meanings that the narrators attach to their own experiences can help to inspire and motivate readers as well as provide useful insights for dealing with similar situations, allowing them to be permanently and constantly redefined [

5].

More recent publications also highlight autobiographical narratives as relevant sources of knowledge for the critical development of teachers [

6]. According to these authors, reflecting on writers’ past and present experiences can lead to improved teaching practice by identifying successful approaches, acquired pedagogical skills, and more effective strategies for teaching in particular contexts.

Knowing that autobiographical narratives can provide a unique and detailed insight into the realities and complexities of the teaching profession and contribute to a deeper understanding of educational work, their study should be encouraged and stimulated so that the knowledge they contain can be socialised and applied.

In view of the above, the present work proposed to analyse the autobiographical narratives of experienced teachers—with 10 or more years in the career—who were well-evaluated by their students and immediate supervisors. The content analysis of the material aimed to identify (1) the main themes addressed in each narrative and whether there was a relationship between the themes addressed by each teacher, (2) the sentiments expressed in the autobiographies, (3) potential challenges faced by the teachers, and (4) teaching and/or assessment methods considered effective by the teachers and their basis in the literature, i.e., whether or not the use of these educational practices has been scientifically proven to be effective.

The effort invested in the study is justified considering that its results can contribute to the field of teacher training by addressing transferable strategies, challenges, and suggestions that support the daily practice of experienced teachers, as well as possible ways to improve professional performance.

2. Materials and Methods

Characterisation of the research

This is an applied research project with a mixed approach [

7]. In terms of objectives, it is descriptive–exploratory research, as it aims to describe and explore aspects present in the narratives of teachers experienced in different contexts; in terms of procedures, it is bibliographical research [

8].

Selection of teachers

To be included in the list of authors, teachers had to meet the following criteria: (1) be experienced teachers, i.e., have at least ten years of teaching experience; (2) be highly rated by their immediate supervisor; and (3) be highly rated by students in the most recent proposed evaluations at their institution.

The proposed criteria were based on the literature. With regard to experience, research shows that time in the teaching profession is positively associated with better student achievement and higher school attendance and that more experienced teachers bring benefits to colleagues, students, and the institution [

9,

10].

However, it is well-known that experience does not always make a good teacher [

11]. In this context, one metric for evaluating teaching practice that has been considered in the literature and is commonly used in educational institutions is the student evaluation of the teacher. Students speak confidently about their experience of a course, including factors that clearly impact teaching effectiveness, such as the audibility of information, readability of notes, application of interdisciplinarity, contextualisation, and availability of the lecturer to help [

12]. These authors have reservations about using student assessment to define a good teacher. This is because not all students have the maturity to evaluate certain pedagogical and formative attitudes, especially when these go against their wishes and preferences [

13]. Moreover, there is subjectivity in the process, as the concept of a “good teacher” varies from student to student [

14]. Therefore, in addition to student evaluation, an evaluation by immediate supervisors has been included to provide a more accurate measure of teachers’ work [

15]. By analysing the opinions of students and managers simultaneously, these authors argue that a broader view of the professional is obtained, that behaviours such as proactivity, willingness to work in a team, and good interpersonal relationships with colleagues are better valued, and that not relying on a single source of data for teacher evaluation reduces subjectivity.

Combining the indicators described above, five teachers were selected, two women and three men, all affiliated to educational centres in the Valencian Community (Spain). In order to differentiate them, the teachers were defined according to their educational level, i.e., whether they taught in early childhood education (ECE), primary education (PE), secondary education (SE), baccalaureate education (BE), or higher education (HE).

Structure of the autobiographical accounts

The autobiographical narratives were divided into two blocks. In the first block, the teachers were asked to write a letter as if the addressees were themselves at the beginning of their career. The letter had to be an honest and clear disclosure of their main experiences, decisions, challenges, and formative professional orientation.

The second block was entitled “What I have learned: successful experiences and mistakes I have made”. In this section, the teacher was invited to share, in 25,000–30,000 characters, pedagogical practices that have worked, those that have not, and any failures or mistakes they had made during their career, along with suggestions for improvement.

Content analysis

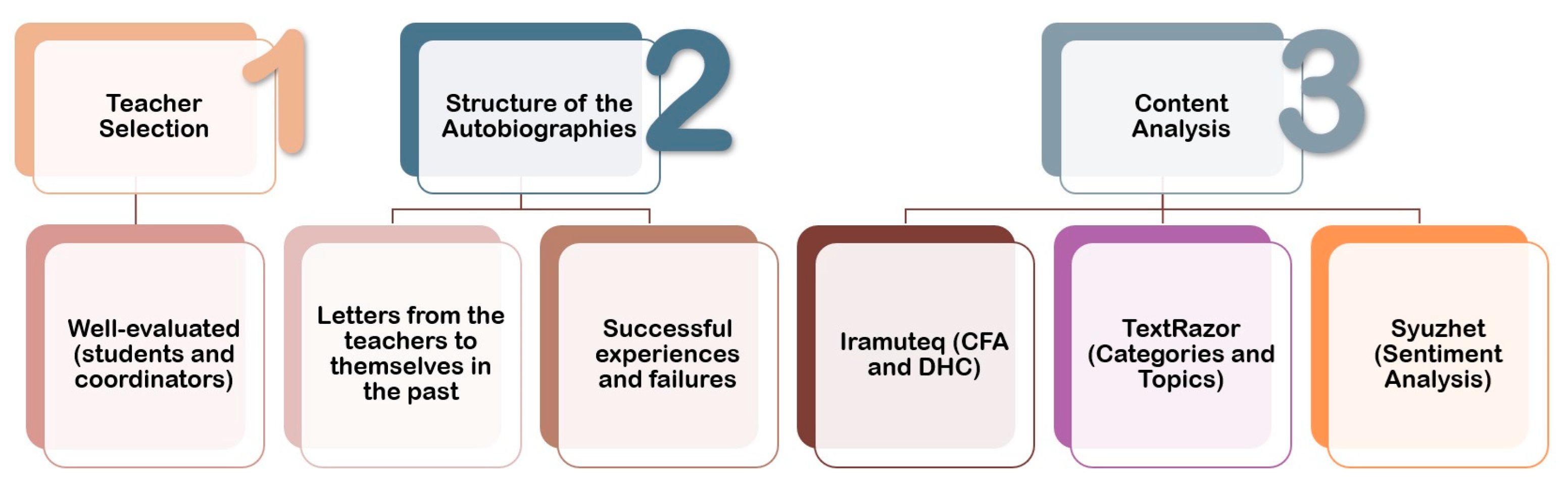

A flow chart summarising all the steps of the methodology is provided in

Figure 1.

The content analysis was conducted using a qualitative research approach with an interpretive and non-experimental design [

16] and sought to understand reality from the narratives, visions, and meanings given by the participants. The development of this research approach combines narrative research and the use of software as a data collection method for subsequent discourse analysis, category structuring, and interpretation.

Thus, the pre-analysis of the material was characterised by the reading and construction of a textual corpus in a format suitable for insertion into the software to be used in the following stages [

17]. In the second stage, we explored and systematised the results by inserting the corpus into the software Iramuteq, version 0.7 alpha 2, and the application programming interface TextRazor, version 3.6.0. The Iramuteq software [

18] was used to carry out basic lexicographic analyses and two multivariate analyses: a Top-Down Hierarchical Classification (CHD) and a Correspondence Factor Analysis (CFA). The use of narratives in educational research demands a lot from the researcher. In this sense, Iramuteq can be a robust help to analyse these data [

19,

20].

In order to correlate the data and create more accurate thematic categories, we also used the TextRazor interface, a commercial tool that scored best in terms of accuracy in textual analysis compared to other similar resources [

21]. This application uses a set of machine learning algorithms and, through statistical topic classification, extracts what it calls “entities”, the main topics present in the text [

22].

For this paper, TextRazor was used to obtain two types of data: (1) general categories and (2) more specific topics. Topics refer to specific themes and relevant keywords extracted from the text. Categories are broader labels that classify the content of the text into broad areas. The relevance of both (categories and topics) to the processed document is measured by a score ranging from 0 to 1, with 1 representing the highest relevance. Knowing that general themes such as “education”, “knowledge”, “science”, and “technology” may appear frequently, the software developers’ guidelines recommend manually checking the results by categories and themes to establish a cut-off point to avoid false positives or ignoring irrelevant terms. This process was carried out in the selection of the final categories in the last stage of the content analysis (inference and interpretation) and a cut-off point of 0.33 was established.

After obtaining the results of the analyses using the two software programmes described above, the data were interpreted, and the results were written up.

Sentiment analysis in R language using the Syuzhet Package

Finally, a sentiment analysis of the texts was also used to identify positive or negative connotations and the main emotions in the stories. The approach used was the one proposed by [

23], which has more support in the literature and postulates eight basic human emotions: joy, anticipation, surprise, confidence, sadness, anger, fear, and disgust. The Syuzhet Package [

24] was used to identify the emotions shown.

The same author specifies that the Syuzhet Package is an R software tool, version 4.1.3, that uses algorithms to identify and quantify the emotions and sentiment patterns present in the analysed text. In the programme, the words are stored in a vector that is subjected to a sentiment analysis according to the chosen dictionary, in our case, that of the National Research Council of Canada (NRC—Spanish language), which determines in binary form whether they refer to positive or negative feelings, or whether they present a characteristic of another, more subtle emotion, among the eight mentioned above. After this categorisation of each word, it is possible to identify, through a bar chart, the level of each emotion in the whole data set.

As for the Syuzhet plots, they have a scale of positive, negative, or neutral emotions. These graphs have a central line representing emotions closer to neutrality so that positive scores represent emotions above it and indicate positive feelings, and values below it are negative emotions represented by negative scores.

There are three other lines in the graph. The first is called “Loess Smooth”, which in the context of sentiment analysis represents a smoothed trend line to visualise the overall trajectory of text sentiment over time. It can help to reveal patterns and trends in sentiment by reducing the impact of short-term fluctuations in the text. The second line, called the “Rolling Mean”, is a statistical technique used to analyse time series data and represents the average sentiment score over a specific period of time. This helps to identify trends in sentiment and reveals more specific changes in each of the ups and downs of the line.

The last line, called DCT, will receive the most attention in our analysis. The acronym stands for “Discrete Cosine Transform”, a mathematical technique commonly used in signal processing and data compression. In the context of the Syuzhet Package, DCT refers to a transformation applied to extract and highlight patterns that may not be readily apparent in the raw data, helping to identify recurring changes in sentiment.

3. Results

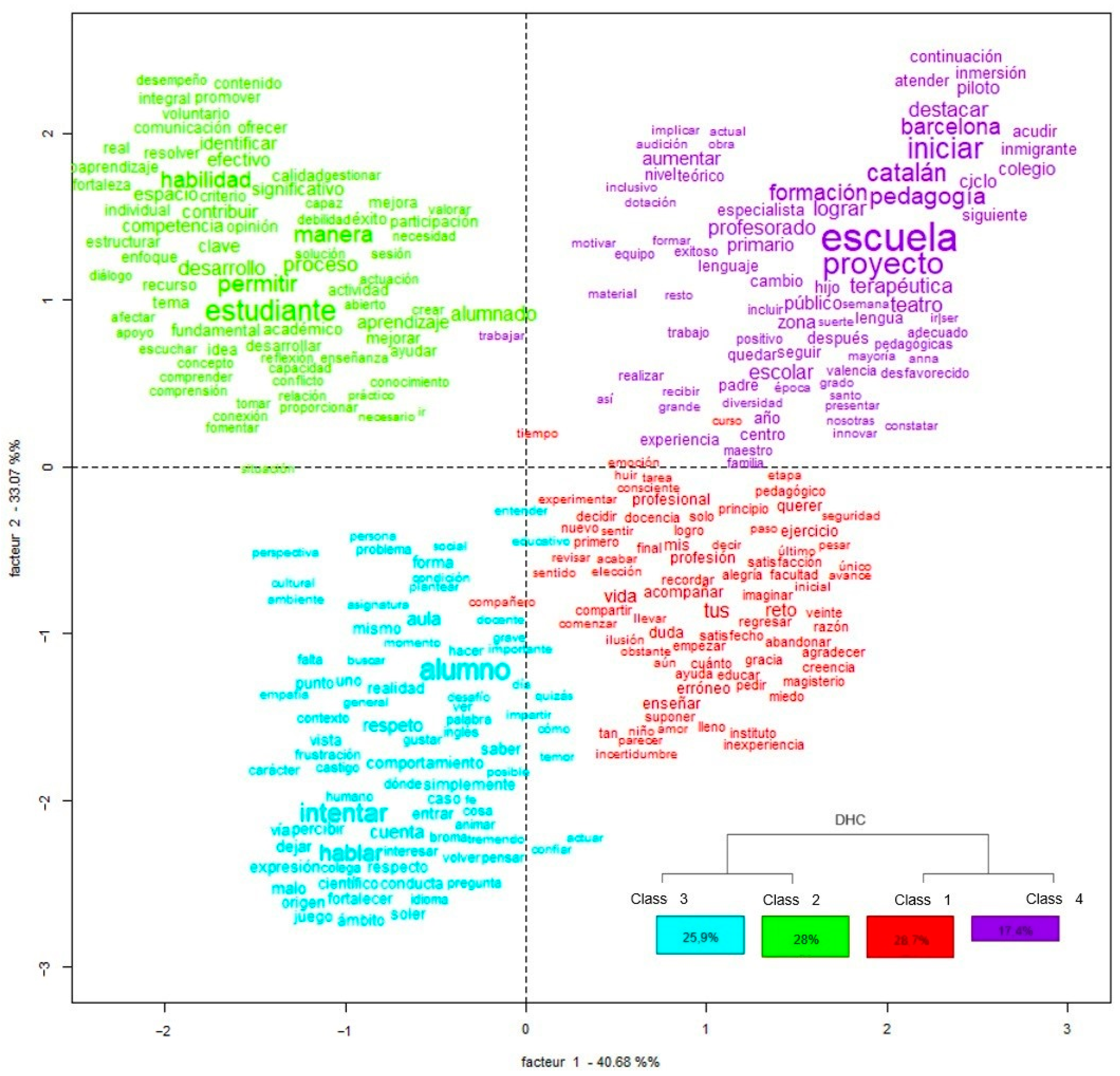

Iramuteq’s CHD analysis, obtained using the Chi-square test (

p < 0.01), allowed us to group statistically significant words in each of the autobiographies (

Figure 2). The processing of the corpus took 14 s and 541 text segments were classified, 414 of which were used; i.e., about 77% of the total corpus. It is worth noting that 75% or more is already considered a good usage [

19].

After processing and clustering, the class dendrogram was obtained (

Figure 2), which shows not only the word classes but also the relationship between them. In addition to the dendrogram, the figure also shows the CFA obtained by crossing the text segments of each class, which generates a graphical representation in a Cartesian plane. In the figure, the most frequent word classes are shown in the upper quadrants, and the least frequent in the lower quadrants. For words, the further they are from the centre and from other word classes, the greater the specificity; the closer they are to the centre of the graph, the greater the neutrality of the term in relation to other classes.

Analysing each class in the graph (

Figure 2 dendrogram, lower right quadrant), two subcorpora stand out as having more segments with correlated words: Class 1 with 28.7% of the segments and Class 2 with 28% of the segments.

Class 1 has more segments because it deals with aspects related to challenges, starting a teaching career, inexperience, and cherished illusions, as well as other emotions related to the beginning of teachers’ professional lives, and because all the narratives begin with a letter in which they describe aspects of their personal lives that led to their professional choices—these data are reflected in the graph by the words “challenge”, “doubt”, “inexperience”, “life”, “new”, “faith”, and “fear”, which are some of the terms that characterise this group.

Class 2, on the other hand, focuses more on the learner and on the discussion of teaching and learning processes. “Development”, “learning”, “skill”, “competence”, “meaningful”, “success”, “understanding”, and “content” are common terms that characterise this word group.

Class 3 (25.9%) is close to Class 1 but focuses on student behaviour. Terms such as “conduct”, “respect”, “social problem”, and “frustration” are common in this class.

Class 4 (17.4%) also shows some proximity to Class 1, as it deals with more teacher-related narratives, but its terms are more focused on the training of specialist teachers and the implementation of inclusive projects designed for students with disabilities, immigrant students, or students who are disadvantaged in some way. The terms “project”, “training”, “teacher”, “specialist”, “inclusive”, “therapeutic”, and “immigrant” are common in this class.

While such analyses allow us to have a general and relational view of the manuscripts, TextRazor makes it possible to have a more specific analysis of each autobiography.

Table 1 shows the most common categories found in each autobiography. Categories such as “Education”, “Teachers/Teachers”, “Students”, and “Science and Technology” were eliminated as they were the most common across the manuscripts, in order to highlight more specific categories.

The table shows general themes that are present in all the narratives, taking into account the structure of the autobiography—indicated at the top. The themes that characterise them more specifically can be seen at the bottom of the table.

In ECH, aspects related to language, psychology, values and ethics, and scientific research are addressed. The implementation of the Therapeutic Theatre Project, with the presence of a hearing and speech specialist, is an important part of the narrative, which is reflected in the terms found. Expanding their pedagogical knowledge to better serve their audiences is another of the elements identified in the scientific research category.

In PE, the teacher highlights the categories of values and ethics, curriculum, mental health, and stress. In the report, they state that teachers should be extremely responsible and respectful and take a very critical view of teaching practice, choosing carefully and discreetly what they use in the classroom. The teacher describes that this was the case. In addition, they also relate difficult situations they have faced during their career, which is why the categories of mental health and stress are also present in the report.

In the SE teacher’s narrative, the categories of language, psychology, politics, and mental health come to the fore. In addition to being an English teacher, the notion of language permeates their own actions as a teacher—in their account, they state that they tried to learn some words in the languages of the families of migrant pupils and reveals that such behaviour broke down barriers and brought the teacher and students closer.

The category “politics” arises in the context of the teacher’s work in the United States, where his students were almost all immigrants and had no knowledge, for example, of the history of racial tension or racism in the country. Moreover, the teacher states that it was common in the institution to apply a very American formula, according to which the world revolved around one’s own culture. As for the categories of psychology and mental health, because they teach in a pedagogical hospital unit, the text contains more extracts related to these aspects.

The most specific categories for the BE teacher are literature, language, philosophy, psychology, and linguistics. Literature, language, and linguistics are related to their areas of training and activity. This teacher states that they have grown and developed by studying and deepening their knowledge of the birth and evolution of the Spanish language, as well as its diversity. They state that the experience has sharpened them, giving them a deep respect for the instrument of communication that unites them as a linguistic entity. In addition, the teacher speaks of various emotions, such as fear, anxiety about the future, important decisions that had to be taken, and philosophical reflections with important questions such as the following: are you teaching, educating, or sharing knowledge? What is the true essence of teaching? Is teaching a vocation or just a job? These are aspects that justify the other categories.

A category that also appears in their text is “conflict, war, and peace”. This teacher recounts an encounter with a student from Ukraine who was forced to leave her life because of the war. In describing the situation of a student torn from her roots, from her daily life, dealing with the uncertainty of not knowing whether she will return to her homeland, where she was an exemplary student, the teacher notes that all this makes them think that their role goes beyond teaching accentuation rules or discussing a literary text. They conclude that they try to make this cruel reality more bearable by helping their pupils to break through the barrier of linguistic isolation, making their psychological well-being the real priority.

Finally, in the text of the university professor, we find the categories music, psychology, sociology, and philosophy. Their first course was at the Faculty of Psychology, and in their report, they also mention literature related to sociology and philosophy. With regard to music, the professor mentions an optional course offered to all university students on the sociology of music and its bidirectional relationship with society. The basic tool used in all of this professor’s lessons was the musical audition, from which the content of the subject on the development and study of musical subcultures, often conceived through social groups, was developed.

With regard to the themes, i.e., the specific and particular aspects most frequently addressed by each author, the five most frequent themes in each narrative were selected, eliminating common items such as “education”, “science”, “teaching”, “research”, “knowledge”, and “information”, as well as the names of the levels and subjects they mentioned. After selection, the themes are presented in

Table 2, together with some text segments reflecting each of the related themes.

In addition to the themes highlighted above, we also looked for references to pedagogical practices or evidence-based approaches to teaching when examining the texts. The main methods used by teachers in the reports are listed and referenced in

Table 3. It is worth noting that these methods had positive outcomes for students in terms of motivation and achievement, as reported by the teachers.

Evidence-based educational practices (EBEPs) in the literature and highlighted by teachers in their autobiographies are presented in

Table 3.

Sentiment Analysis

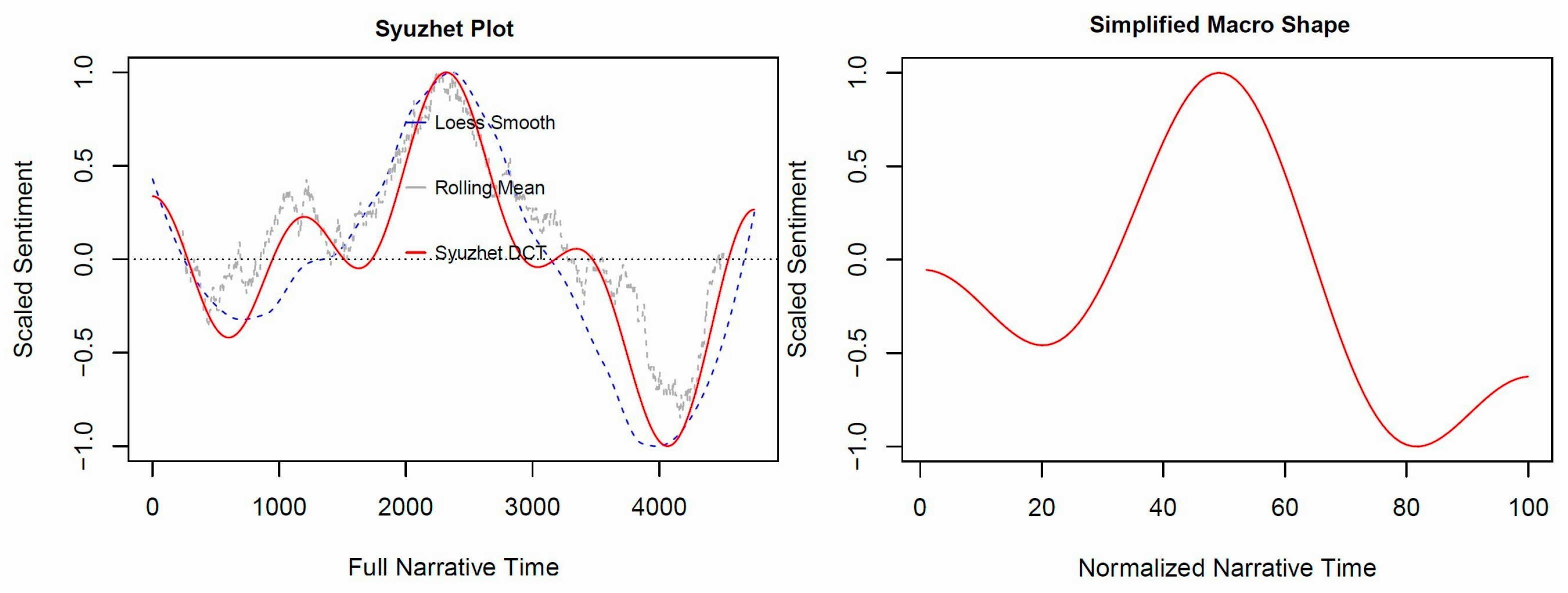

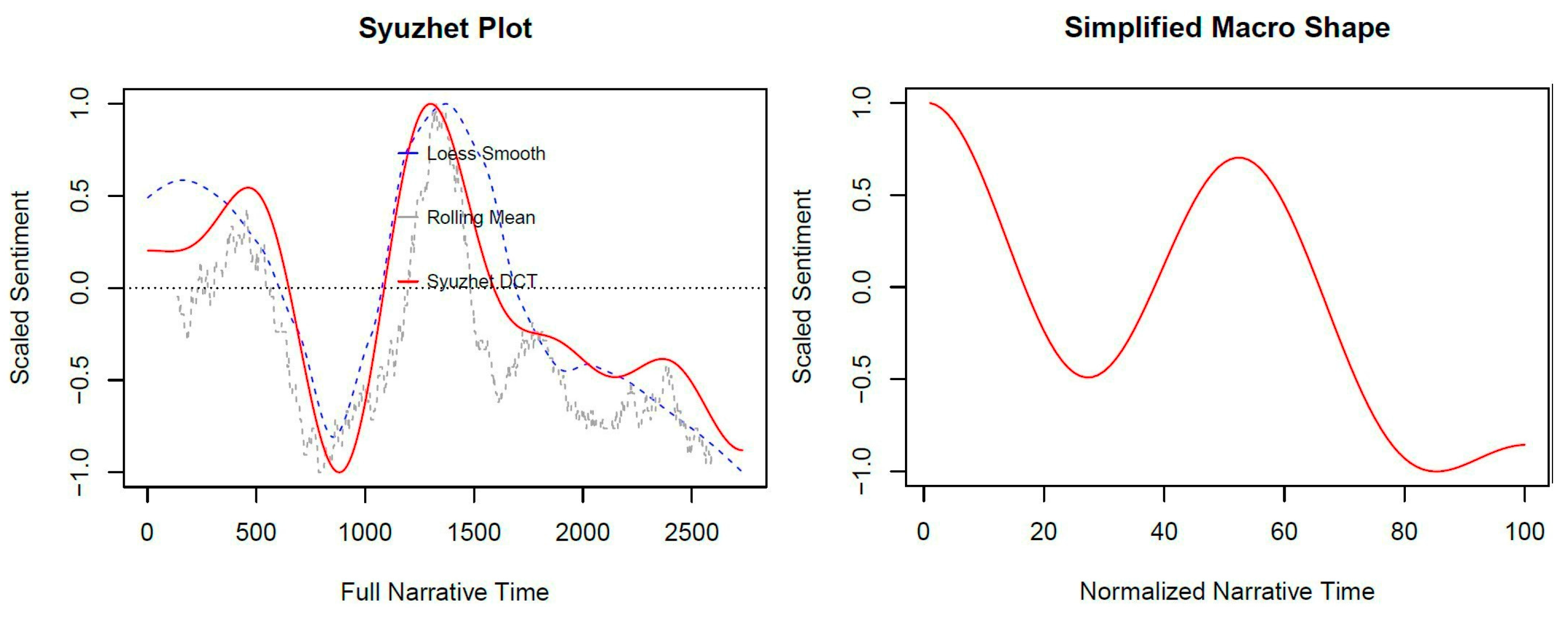

In the case of the ECE teacher’s autobiography (

Figure 3), we can see that the narrative contains almost equal amounts of negative and positive elements. The beginning of the narrative is characterised by negative feelings. Using the DCT curve (solid line in the graph on the left), we can see that while the central part of the narrative, described in the letter, has more positive aspects, the beginning and the sections near the end of the autobiography are marked by probably sadder or more nostalgic feelings, although the end itself shows a sudden increase, indicating that it ends on a positive note.

At the end of the text, the teacher actually presents hope and gratitude for the journey and the achievements. The normalised image in

Figure 3 (right) also allows us to see that the beginning and end of the narrative contain more elements of negativity, but the end is more negative than the beginning.

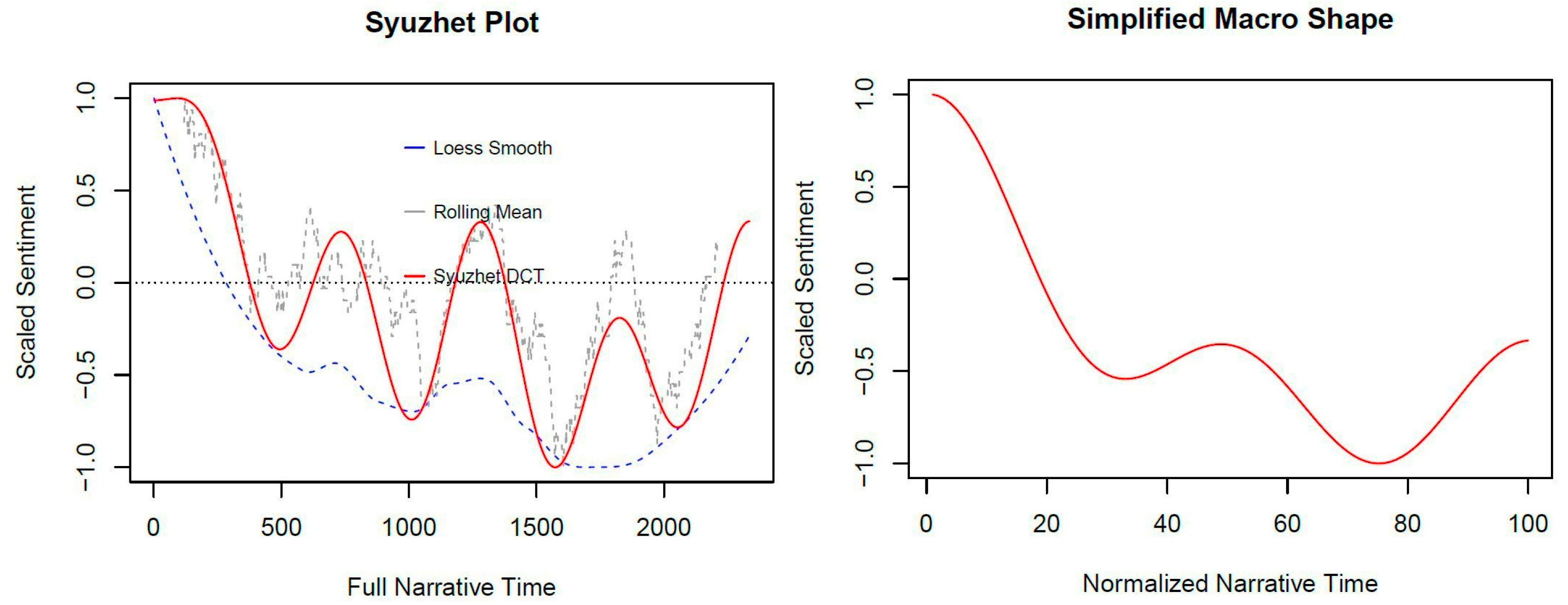

In the case of the PE teacher’s autobiography (

Figure 4), we can observe that, despite the greater presence of oscillations, the beginning of the narrative is characterised by negative feelings, which improve and remain positive until they become negative again towards the end. Despite this, the narrative is more positive than the previous one, as can be seen from the moving average, represented by the lighter grey line in the graph, which remains over the line virtually throughout the narrative.

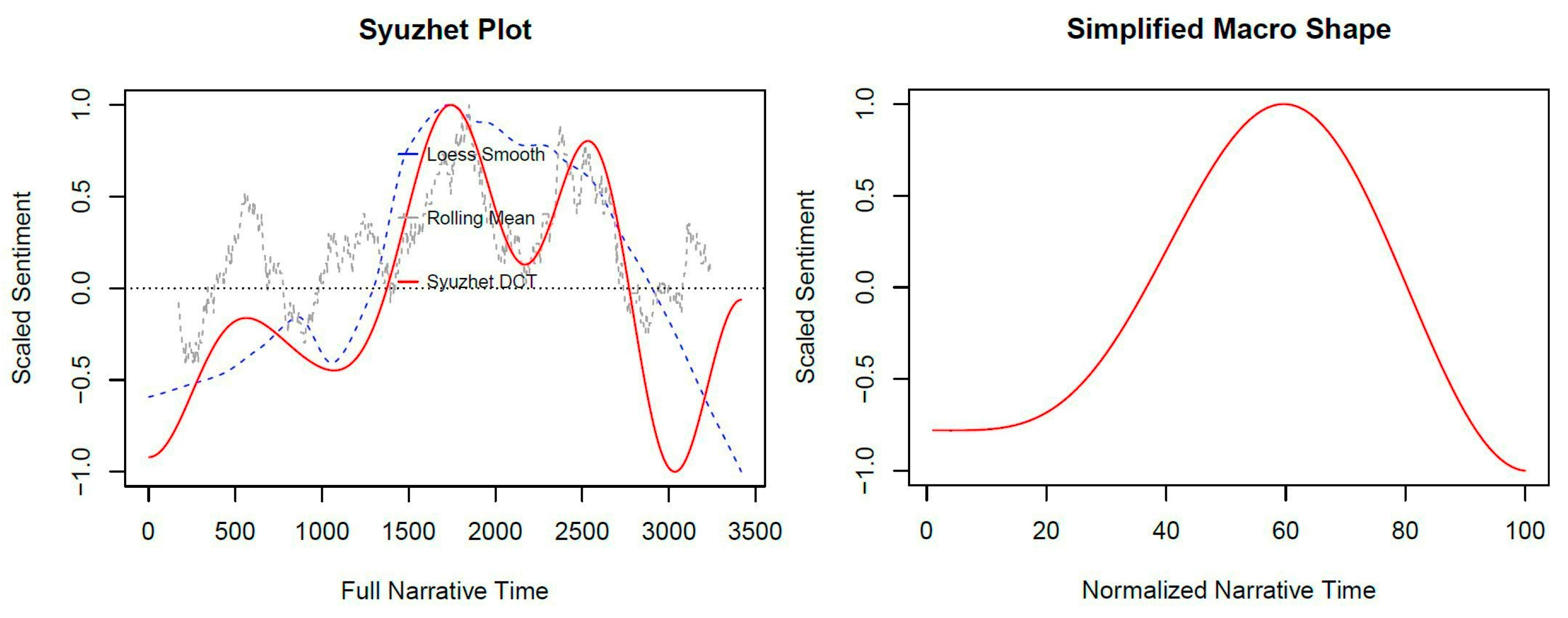

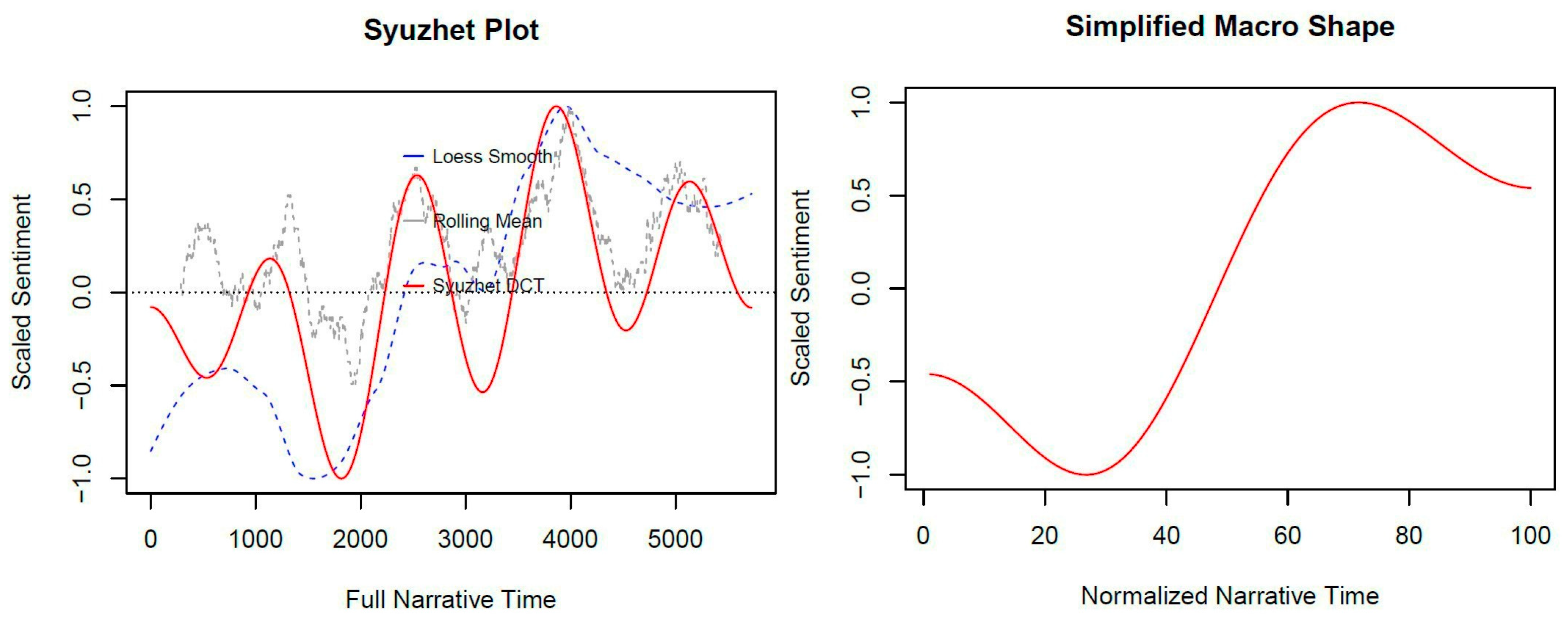

The SE teacher’s autobiographical narrative (

Figure 5) shows marked fluctuations, as can be seen in the standard narrative graph. The author starts with positive feelings and then moves to negative feelings and back to positive feelings. However, from the middle of the text to the end, the teacher presents a greater number of negative feelings.

The scale of feelings expressed by the BE teacher (

Figure 6) shows a beginning marked by clearly positive feelings. However, despite having the most positive beginning of all the narratives, the teacher has the highest load of negative feelings of all the autobiographies. Looking at the dotted line (loess smooth) as well as the normalised narrative graph, we can see that even with the relatively positive peaks in the central part of the narrative, much of the text remains with markedly negative feelings. Thus, the teaching career seems to have been marked by a beginning with very high points, followed by equally intense low points.

Finally, the analysis of feelings in the HE teacher’s autobiography shows a greater predominance of positive feelings (

Figure 7). Only at the beginning is there a negative valley, but throughout the narrative, neutral and positive feelings are more present than in any of the other narratives, as confirmed also in the simplified analysis of the standardised narrative.

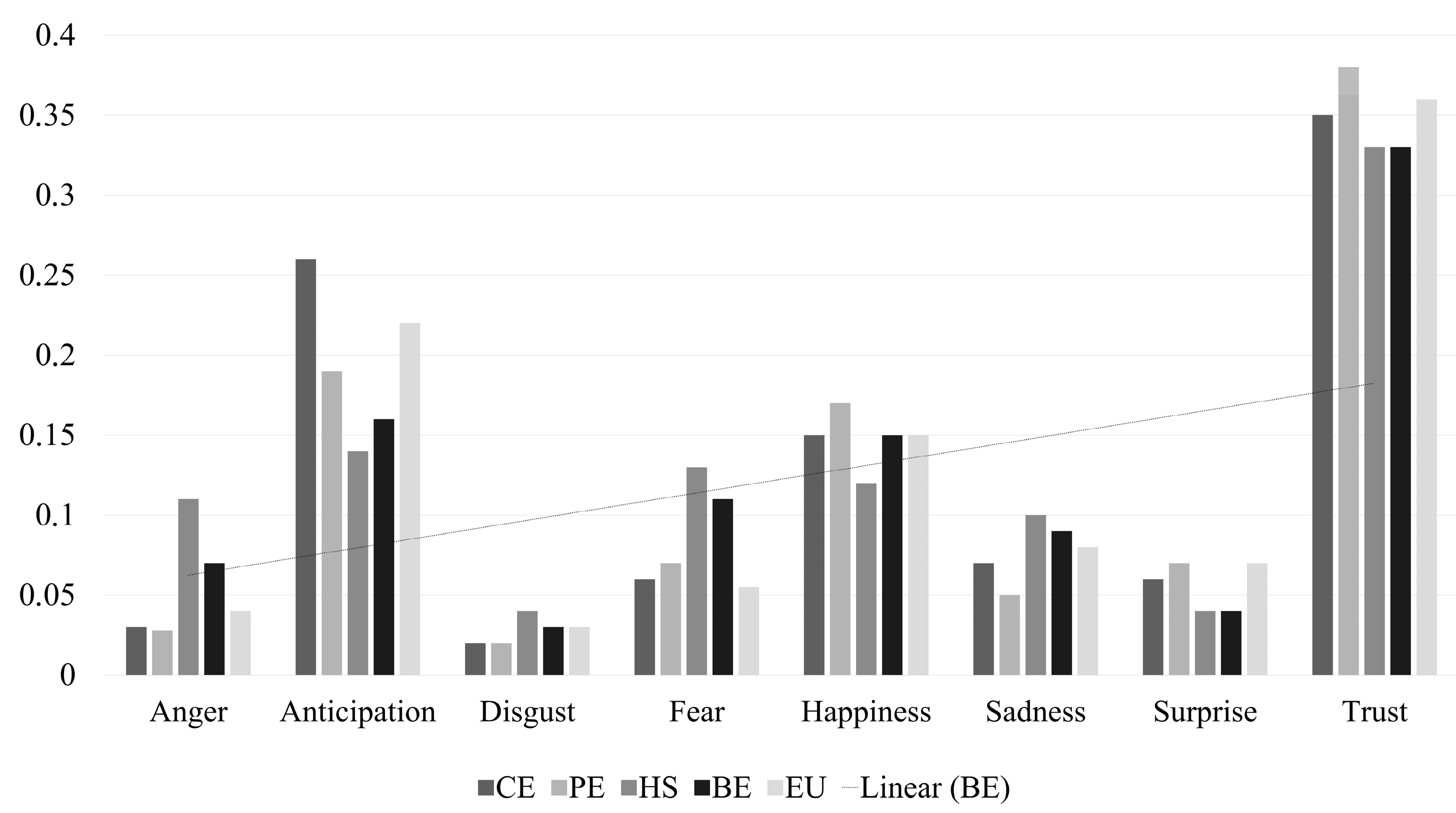

In terms of the types of emotions found in the narratives,

Figure 8 shows each of the eight emotions identified by the package [

23,

24]. The feelings of confidence (average = 0.35), expectation or anticipation (average = 0.19), and joy (average = 0.15) are the most present in all texts. The most uncommon feelings in all of them were disgust (average = 0.03), anger (average = 0.06), and surprise (average = 0.06).

In the HE teacher’s narrative, there was more anger, fear, and sadness and less joy than in the other teachers’ narratives. The autobiography with the lowest proportion of negative feelings (anger, disgust, and sadness) was that of the PE teacher. This is also the story with the highest percentage of the most positive emotions (joy, surprise, and confidence).

4. Discussion

The dendrogram and the factorial representation of the classes obtained by the Iramuteq software (

Figure 2) showed that the class of words most frequently found in the text segments was related to emotional aspects, challenges, doubts, fears, and beliefs, as is common in reports of this type [

1,

33]. The second class of most frequent terms highlights the teachers’ concern to fulfil their role with quality and effectiveness, so teaching and learning processes and terms related to success and the understanding of content are also very frequent. Recent research has indicated a relationship between these classes, showing that negative emotions and job stress have a significant correlation with poor teacher performance [

34], while there is a positive and significant relationship between teacher satisfaction and better performance [

35]. Therefore, in addition to considering teaching strategies, it is important to pay attention to teachers’ emotions, as these can directly affect their performance in the classroom. When exploring the categories and themes present in each text (

Table 1 and

Table 2), topical and relevant themes were identified. In particular, the ECE teacher referred to the implementation of the Therapeutic Theatre Project as an inclusion proposal applied in their educational institution. The terms “inclusion”, “courage”, and “behaviour modification” were common and show a strong connection with the inclusive approach applied by the teacher. They report on the challenges and benefits in terms of developing the skills and abilities of students with special educational needs and show sensitivity and a refined sense of professional ethics, particularly in helping disadvantaged students. This is the only chapter where inclusive education is one of the main themes, and it is extremely important that teachers demonstrate an active stance in this regard [

36].

After all, teachers are key elements in building inclusive schools [

37], which in turn are the most effective means of reducing prejudice, challenging discriminatory attitudes, and ultimately creating a more responsive society [

38]. More than adapted methods and resources, learners with disabilities need a team that is trained and willing to support them [

39,

40].

The most prominent categories in the PE narrative are values and ethics, mental health and stress, and motivation and self-learning. His ethical behaviour and care in choosing pedagogical practices are recurrent in the narrative description. The author even encourages teachers to be researchers too, to develop and conduct their own studies based on evidence.

These aspects have been highlighted in research over the last few decades, which has shown that teacher–researchers can help to increase student achievement in their own classrooms and document effective interventions [

41] and that they should be invited to engage in research, because this can develop their teaching technique and invigorate their work [

42]. However, it is important not to romanticise or generalise self-learning skills, nor to ignore the fact that many teachers value research but need more time and professional development opportunities to engage productively in research and influence classroom practice [

43].

They also talk about the difficult situations they have had to face in the course of their career with a great emotional burden, which, at times, has affected their motivation, energy, and even their health—this is why the categories of mental health and stress are also present in the report. As mentioned above, these feelings need to be taken into account, and more attention needs to be paid to teachers’ well-being, as their satisfaction directly affects their performance in the classroom [

35].

In the HE teacher’s narrative, the categories of language, psychology, politics, and mental health are prominent, as are the themes of empathy, motivation and curiosity. Welcoming migrant students and critical language teaching characterise this teacher’s narrative. By suggesting a proposal for welcoming migrant adolescents, the teacher also reveals their concern to promote a truly inclusive education. As [

36] (p. 318) points out, “inclusive education necessarily implies pedagogical actions aimed at reflecting on the need for an education that transcends geographical, social and linguistic boundaries”.

Furthermore, in describing his work with immigrant students in the United States, they agree with current pedagogical references [

44,

45,

46] in recognising the relationship between decolonisation and critical thinking in the construction of a new culture, aiming to build knowledge that values students’ knowledge without perpetuating the superficiality that may be characteristic of their lack of experience or maturity. By strengthening the interpretation and critique of adverse circumstances in their contexts, teachers can generate reflections in students that allow them to develop new attitudes, greater maturity in political choices and perhaps possible solutions to, for example, local problems affecting their community.

Another point worth noting in their report is the fact that they work in an educational unit within a hospital; this aspect brings into focus categories and issues related to health, psychology, empathy, and the motivation of the students, who are going through situations that deplete their physical and mental energy. The teacher’s careful attention to motivating these students permeates the narrative.

Paying attention to others and seeing the target of one’s work as an object of zeal, care, and even affection are practices that have been scientifically linked to human well-being, the effects of which are not moderated by gender, age, or other characteristics [

47,

48]. In addition, the exercise of empathy, social connection, a sense of purpose and meaning, and a sense of contributing to the education of others also increase teachers’ self-esteem and self-worth, aspects that can contribute to a sense of professional fulfilment and satisfaction [

48].

As far as the BE teacher is concerned, the categories and themes are mainly related to Spanish language and psychology. However, one category that also appears in the text is related to “conflict, war, and peace”. The teacher talks about a student from Ukraine who had to leave her life because of the war. The teacher’s stance in this case is in line with the empathic, critical, and inclusive stance identified in the literature and used by the HE teacher [

36,

44,

47,

48].

Music and teamwork deserve attention in the HE teachers’ categories and themes. The use of music in sociology teaching can facilitate the identification of concepts in the field and stimulate student interest by providing relevant examples. Media products can also enhance sociological understanding [

49].

In terms of functional and evidence-based teaching practices (

Table 3), in addition to the music used by the HE teacher, drama, contextualisation, and critical pedagogy feature prominently in the narratives. These methods have an extensive and established literature foundation, with applications for audiences of different ages, and show positive results in student performance and motivation [

26,

28,

50]. Only one of the proposals mentioned has a greater local specificity (it mentions a programme implemented in Spain); however, in its description, we can also identify aspects related to critical pedagogy, active methodologies, autonomous learning, and contextualised teaching [

27].

By identifying such pedagogical methods and their use in different contexts, it is possible to disseminate the practice so that other teachers become aware of it and recognise its applicability and use it in their contexts [

51].

Cordingley [

52] stresses that trying new teaching strategies based on evidence from other teachers or settings will always run the risk of not working in that particular context. However, seeking out and analysing different methods and resources used by other teachers has the potential to support teaching precisely because it invites teachers to become learners again [

51]. The literature also suggests that the gap between research and practice in education is due to the fact that many relevant approaches are not shared and made available to educators in an easily accessible way [

53]. Therefore, the presentation of functional practices, used in different contexts and coming from teachers with long experience and good evaluations, can contribute to this.

Finally, regarding the sentiment analysis, associated with the factorial representation of the classes carried out using Iramuteq, we can identify an intense emotional involvement of the teachers in their reports (class 1) as well as a greater presence of positive emotions (

Figure 8). These aspects are supported by the literature on the evaluation of experienced teachers. As pointed out by [

54], despite the often-intense work routine, these teachers generally report a sense of fulfilment in their profession and look for ways to overcome the adversities of teaching.

In analysing the emotional dimension of teaching [

55], they also emphasise that the emotional nature of teaching is quite evident. These mentions are characterised by different types and levels of positive and negative emotions. By highlighting positive emotions, the authors reinforce feelings of enthusiasm and satisfaction, which seem to be mainly linked to the micro-contexts of the classroom and show that teachers continue to place their students at the centre of their concern and care.

It is worth noting that there were also manifestations of negative feelings in the autobiographies, as can be seen in some of the examples in

Table 2. This aspect is also supported by the literature, which indicates that over-regulation, lack of recognition and infrastructure, or unsatisfactory remuneration lead to feelings of discouragement and frustration among teachers [

55].

Still, in relation to negative feelings, when analysing

Figure 3,

Figure 4,

Figure 5,

Figure 6 and

Figure 7, we can observe that the BE teacher’s narrative is the only one with an inverted normal curve, i.e., it has more negative and neutral representations than positive ones. In addition to the usual insecurities and inexperience at the beginning of the teaching journey, the narrative also describes situations related to the war in Ukraine, as mentioned above, which naturally led to reflections charged with more negative feelings [

56].

The HE teacher follows a similar pattern. Although in the overall analysis of the narrative, they had a less negative result than the BE teacher, there was still a greater than average manifestation of negative feelings (

Figure 8). This result is attributed to their work in the hospital unit, as well as their contact with migrant and discriminated students, thus reinforcing findings in the literature that it is not the direct relationship between teacher and student that is primarily responsible for feelings of dissatisfaction in the profession [

55,

56].

The narrative with the least negative feelings and the most positive feelings was that of the PE teacher, as can be seen in both

Figure 4 and

Figure 8. Their autobiography is full of optimism and hope and provides important lessons at the end: (1) conflict is inherent in relationships between people, learn to see it as an opportunity for growth; (2) examine your own beliefs and values, as those that limit you will hinder your relationships with others and especially with your students; (3) learn to distinguish what is yours from what is not; (4) put your heart and head into everything you do and review your principles whenever you see your goals wavering; and finally, (5) never forget that true teachers are those who never cease to be students.

5. Conclusions

The mixed methodology approach allowed us to tackle a complex and multifaceted phenomenon based on the study of autobiographical narratives. The analysis focused both on the categories and central themes of the five teachers’ discourses and on the feelings that emerged from their words as they recounted life experiences, challenges, and how they coped with them.

In relation to the achievement of the proposed objectives, we have described the main themes addressed in each narrative and the relationship between the themes addressed by each teacher and analysed the emotions expressed in the autobiographies. The results show that positive emotions are more present than negative emotions throughout the teachers’ journey and that positive emotions are particularly associated with direct and relational involvement with students, while negative emotions are more closely associated with external conflicts, structural issues, and difficulties when proposing implementation within the institution’s team. This information is important for policy makers and for the development of care and attention measures to improve quality of life in the teaching profession.

With regard to the third objective—identifying potential challenges for teachers—the themes and categories associated with immigration, war, politics, and inclusion show that social issues have a direct impact on the work of teachers. We cannot ignore aspects such as the location of the educational centre and the impact it can have on the community (and vice versa). These aspects should inspire and guide policy design that considers the context of students and their families but is not limited to it.

The final aim was to identify the evidence-based teaching practices mentioned by teachers. Among the practices mentioned, drama, contextualisation, and music are already well-known and widely used methodological approaches. Apart from them, critical pedagogy and the personal and social responsibility programme caught our attention. In fact, students learning should not be limited to historical and scientific content. They should also learn how to relate to their peers in a holistic way, how to become more autonomous, how to improve their cooperative and leadership skills, and how to develop a sense of social responsibility.

Finally, the analysis of the autobiographies allows us to conclude that the formation of a critical, thinking, reflective citizen, capable of respectful dialogue on scientific, contemporary, and social issues, is the kind of holistic vision that we need to take into account when thinking about curriculum and teaching practices. Such information, as revealed in the results, may be relevant in choosing strategies or designing future interventions, both for practising teachers and for future education professionals.

As for the limitations of this study, we highlight the limited number of participating teachers. However, we consider the participants to be representative of the profession, given that they have extensive experience, are well regarded both by management and by their students, and represent different educational stages and contexts.

As far as future research is concerned, it would be interesting not only to overcome the above-mentioned limitation by compiling a greater number of narratives, but also to carry out comparative analyses involving other countries or regions. It would be useful to identify peculiarities, points of convergence, and alternatives and to link the results obtained with specific policies or programmes, educational levels or, in the case of international comparisons, the particularities of each country’s reality.