Abstract

This study investigates parents’ perceptions of the impact of cultural diversity on their children and their role in facilitating their children’s navigation through diverse cultural landscapes. A questionnaire, part of the Erasmus+ REACT project (the reciprocal maieutic approach), was distributed among 243 parents of secondary school children in Bulgaria, Italy, Greece, and Spain. It aimed to shed light on the effects of cultural diversity on young individuals and the influence of parents in fostering intercultural competences and critical thinking. The findings reveal a strong positive perception among parents regarding cultural diversity, with a significant majority acknowledging its beneficial impact on their children’s development. Parents identify themselves as crucial educators and role models, emphasizing the importance of open dialogue, positive exemplification, and the teaching of tolerance and respect. Despite recognizing the general adeptness of their children in interacting with cultural diversity, parents perceive challenges, particularly related to differences in beliefs, religions, and social classes. Parents favor experiential and participatory activities over traditional academic methods for fostering intercultural competence, suggesting a shift toward more inclusive educational practices that involve family and community. This study calls for educational initiatives that promote active participation, connection with the community, critical thinking, and empathy toward cultural differences.

1. Introduction

In an increasingly multicultural, globalized, digitalized, and diverse world, education that focuses on developing intercultural competences and critical thinking, promoting tolerance and open-mindedness, and reducing prejudice and stereotypical thinking is more important than ever before.

The aim of this article is to describe and analyze the results of a questionnaire addressed to parents of secondary school children in four European countries regarding their own and their offspring’s attitudes and responses to cultural diversity. The questionnaire represents an initial step in the development of the reciprocal maieutic approach (RMA) through the Erasmus+ REACT project. The aim of the reciprocal maieutic approach pathways enhancing critical thinking project (REACT) was to develop and implement an innovative methodology to promote the acquisition of critical thinking skills with the aim of fostering inclusive education and values such as tolerance and acceptance of diversity as an enriching value. The RMA employs dialogic learning to discuss and discover the processes that give rise to intolerance and to better understand how prejudices and stereotypes are created. The use of the RMA also aims to motivate teachers, students, and parents to learn actively and autonomously following the Montessori motto “teach me how to do it by myself”. The piloting of the REACT project was carried out in four partner countries in the EU (Bulgaria, Italy, Greece, and Spain) and has proved to foster dialogue, reflection, empathy, and critical thinking among students in early secondary schools and vocational training centers.

Parents and schools may often be breeding grounds for stereotypes and prejudices. Some children have their first contact with diversity when they attend school. For this reason, what schools do and promote is key to undermining strong diversity conceptions and approaches that students bring from home. In the early 1980s, Allport and Pettigrew conducted research and showed that what schools and teachers do in their classes can be very effective in breaking down stereotypes, but it should be done in the right way and using certain approaches.

Parental involvement has been a focus of study since the 1960s. At first, it was thought that children’s learning and development was principally the domain of the school and that parental involvement in schools was a school initiative, with parents attending the school either to assist in some activity or to attend sessions designed to help them become ‘better’ parents. Epstein et al. [1] developed a model with what they denominated ‘overlapping spheres of influence’ that considered the community, homelife, and the school all learning spaces that influenced the learning process and provided different types of activities and initiatives that made interaction between parents and school a more symbiotic, proactive process.

The present article first provides context for the questionnaires, with a brief description of the REACT project. It then discusses the development and the relevance of intercultural education and competences, critical thinking, and parental involvement in schools and the learning process, with the aim of providing a comprehensive justification and background to the questionnaire and its results.

2. Theoretical Framework

2.1. The REACT Project

The main goal of the REACT project is to promote inclusion in secondary education settings by employing the reciprocal maieutic approach merged with elements of the Montessori experience. The RMA, developed by Danilo Dolci (1924–1977), an Italian social activist, educator, and philosopher working in Sicily [2], represents a powerful tool in the promotion of active citizenship, critical thinking, and dialogic learning. The RMA is a method of collective exploration that employs individuals’ experiences and intuitions as the starting point for a collective process of the exploration of words and concepts key to inclusive education and the conception of stereotypes. It encourages critical thinking and offers a safe space for participants to confront one another and each other’s ideas, and to search for the real meanings of words and concepts. Ultimately, the RMA reduces intolerance and stereotypical thinking. It can be considered a method that can and should be integrated into the curriculum and be adapted to many different school subjects but should be used in conjunction with other active learning methodologies. The role of the teacher, as in the Montessori Approach, is to prepare the learning space, removing obstacles to learning, and to observe and intervene when necessary, allowing participants to be the protagonists rather than beneficiaries of the learning process.

The RMA is holistic and directly involves students, teachers, and parents and, more indirectly, policy makers, local authorities, and other public entities involved in the field of education. The REACT project consisted of a series of workshops following the RMA, aimed at students aged between 10 and 17 years old. These workshops started from a problem or need identified in the classroom or school, and through this methodology, the students themselves managed to define the problem and provide a solution that emerged from discussion and reflection among them. The initial stages of the project consisted of surveys relating to cultural and other types of diversity completed by students, teachers, and parents with the aim of ascertaining their perceptions and beliefs about how diversity affects daily life both at school and outside in the community. This article describes and analyzes the results of the survey completed by parents.

Research has demonstrated that parents require guidance in their role as educators; however, there is, in general, a lack of opportunities to share their experiences and concerns with other parents and professionals. Parent events organized by schools are often poorly attended as they tend to be school initiatives rather than activities involving joint planning with parents [3]. Parents therefore tend to seek help and advice about their children from their ‘intimate’ networks, family, and friends, rather than from schools. Domina [4] posits that parents are key to whole-school approaches and community schooling, which have been shown to promote social inclusion by influencing students’ attitudes toward other cultural groups. The EU Commission, in a recent study, remarked that nearly all EU countries have implemented national policies and formal guidelines to enable or promote parental participation in school administration [5]. Parental involvement is not only relevant to children’s academic achievements and results but is also linked to their emotional and social development. The REACT project with its RMA approach has and will involve parents in the initial planning phases and in the RMA workshops, making them key actors in the development of critical thinking skills. The competences they develop in the RMA workshops will be key to forging better conflict resolution strategies in the context of family and school. Furthermore, the RMA approach operates on multiple levels within the educational context. Internally, it fosters intuitive thinking among students, encouraging them to explore their own ideas and insights. Simultaneously, teachers play a crucial role in invoking and facilitating discussions centered around the principles of reciprocal maieutic. They guide students through the process, prompting them to articulate their thoughts, engage in critical reflection, and collaboratively construct knowledge.

The results of the survey conducted with parents, which will be discussed in this article, constituted the initial phase of the project, considered preparation and information gathering, during which parents’ perceptions were consulted regarding how they perceived cultural diversity impacting their children. Thus, a part of the RMA workshops was based on the results of this survey.

2.2. Intercultural Education and Intercultural Competences

Intercultural education is also variously known as, or falls into the category of, global education, anti-racist education, inclusive education, and multicultural education. All of them share the objective of integrating people of different ethnic backgrounds into the community and the educational system [6,7]. Even though many authors refer to intercultural education by different names, they are talking about intercultural education. Intercultural education refers to the specific education that aims to include students of different cultural backgrounds in one system. It is a type of education that acknowledges and considers those cultural differences which are manifested in the communication, learning, and teaching processes [8].

It has long been known that integration among culturally diverse students does not occur naturally by simply spending time in the same place together. Allport’s [9] inter-group contact theory states that although contact is needed between people from different cultures and ethnicities for quality interaction to occur and prejudices and stereotypes to be reduced, the interaction should be monitored and ‘controlled’. The monitor, the teacher in a classroom setting, should develop group work with the participants, guide groups, and decide how far the interaction should go [8,10,11]. This guided group work will help students to modify their beliefs and prejudices about each other. ‘Control’ implies, for example, observation of the students and their reactions, noticing when a student feels uncomfortable in a group activity and bringing the class back to a whole-class dynamic. For meaningful, successful interaction of this type to take place, there are four key conditions, according to Nesdale and Todd [12]. Participants should have equal status (all members of the group are considered equal), shared objectives, effective cooperation and teamwork, and finally, support from a more experienced person, the teacher. The role of the teacher or guide is key to eradicating stereotypical thinking and to achieving successful formal learning [13].

Methodologies such as cooperative learning [14] have all of the ingredients required for successful group work: positive interdependence (all members are equally important to the task to ensure a satisfactory outcome), individual and group accountability (group members must take responsibility for their own actions and learning, as well as the actions and learning of the group), the promotion of interaction, the appropriate use of social skills, and group processing. However, a teaching/learning methodology is not enough. Cultural integration does not happen automatically through contact with multicultural groups, unless the experience is transformed into a learning experience that develops intercultural competence [15,16,17]. Teachers must therefore be trained not only to implement methods such as cooperative learning, but also to understand the processes involved in adaptation to and integration into a different culture, and to transform the learning environment using intercultural interventions if they are to enhance their learners’ intercultural competence [18].

Intercultural education and pedagogy appear to be necessary given the diversity present in Europe and its educational systems [19]. They represent another stage in attempts to address issues surrounding the integration of different ethnic backgrounds in the community and in education. Intercultural education takes a step beyond the assimilationist policies and compensatory mechanisms, popular for so long, wherein newcomers to a culture were expected to adopt the host country’s customs, leaving their own cultures and traditions behind, and behaving as though nothing from the past or from their original culture was valid anymore. Intercultural education and pedagogy were developed over the years in the field of education [6,20]. They are conceived of as education that is rooted in a particular culture but is based on an appreciation for and valuing of its culturally diverse members, their cultures, beliefs, and perspectives. They embrace practices that focus on all members of a particular society and favor a holistic approach to education that includes cognitive, behavioral, and affective factors [7]. They are key to understanding that we are cultural beings and the way we learn is culturally bound.

So, the aim of intercultural education is equality of opportunities for all members of a society. According to Aguado-Odina [6], opportunities refer to being able to choose and to having access to educational, social, and economic resources. For this to occur, racism must be addressed, and intercultural competence must be developed [21].

Several recent European reports conclude that the development of intercultural competences is a key factor in enabling young people to live and work responsibly, sustainably, and harmoniously in our ever-changing, multicultural society. Developing intercultural sensitivity or competence will help in the reduction in stereotypes [22].

Stereotypes may be understood as reductionist rigid mental images or descriptions of a group that can be positive or negative, focused on a group of people who share similar characteristics [23,24].

Paige, Cohen, Kappler, Chi, and Lassegard also defined stereotypes as “the automatic application of information we have about a country or culture group, both positive and negative, to every individual in it” [25] (p. 57). The root of stereotyping is the use of categories for people in groups; its origin comes from relations between groups and its transmission occurs through socialization, such as mass media. Stereotypes are generally negative and inaccurate and constitute a failure to recognize diversity among a group of people.

In short, the main aim of intercultural education is to provide a quality educational system for all participants. Work, involving specific intercultural pedagogy, needs to be carried out to raise awareness of and eliminate stereotypes and prejudices. Cultural differences should be embraced and valued. Schools working with their communities, including parents, represent ideal settings for the development of intercultural competences [26].

2.3. Critical Thinking and Stereotypical Thinking

Stereotypical thinking is often marked by ‘Ambiguity intolerance’ which is often defined as a state characterized by psychological uneasiness or anxiety [27]. Some authors feel that if a situation is seen as threatening rather than interesting or positive in any way, the uneasiness and anxiety that characterize ambiguity intolerance are activated [28]. The same authors relate ambiguity intolerance to a preference for stereotypes [29]. This is also linked to a less developed intercultural competence and the inability to adjust to unknown circumstances, being afraid of leaving your comfort zone. Critical thinking is a rigorous process of conceptualizing, analyzing, synthesizing, and evaluating content and revising where it comes from or who generates it by observing, experiencing, and reflecting [30]. The ‘ambiguity tolerance’ and ‘ambiguity intolerance’ dichotomy is relevant to current thinking on how critical thinking and intercultural competence may affect degrees of tolerance, since both competences need to be learned and practiced, and both require leaving your comfort zone. Both competences belong to System 2 of our brains as Khaneman explains in his book Thinking Fast and Slow [31]. Stereotypes can be seen as cognitive schemas or bits of knowledge that help individuals interpret their world. However, they can also be seen as cognitive limitations, involving a lack of cultural knowledge that can be reduced through conscious motivation and educational interventions. Prejudices are learned ideas that are “formed through direct instruction, modelling, and social influences on learning” [32] (p. 500). Therefore, addressing and dismissing stereotypes requires conscious effort and may involve specific educational processes facilitated by teachers and supported by the broader community of educators, including parents.

The likelihood of students exhibiting racist, prejudiced, ethnocentric, or intolerant behaviors is influenced by cognitive differences, personal experiences, and the [31] student’s zone of proximal development, the distance between the level of problem solving at individual level and the level that can potentially be achieved with the help of a more able adult or peer [33]. This suggests that educational strategies and pedagogical approaches play a crucial role in shaping students’ attitudes toward stereotypes [13]. Actively confronting stereotypes during the educational process can reduce intolerance [34]. By becoming aware of stereotypes and challenging them cognitively, students can develop new perspectives. Critical thinking should be developed as a learned skill that must be practiced and integrated into the curriculum. This process involves engaging students in active learning, applying content, and utilizing various learning methods and assessment strategies. The REACT methodology aims to enhance critical thinking skills through reciprocal maieutic workshops, where dialogue based on participants’ own intuition and experience forms the basis for discovering the deeper meanings of words and concepts that otherwise may be used and understood on a very superficial level. The reciprocal maieutic approach operates both at the school and community level. It focuses on dismissing stereotypes through a cognitive process and involves students, teachers, and parents, presenting an innovative pedagogical strategy.

2.4. Parental Involvement

See Table 1 below. Family and home life have not been the subject of extensive research as contexts in which differences are experienced, even though the importance of family life has long been recognized in the creation and transmission of prejudice and stereotypes, as seen in Allport [9].

Table 1.

Epstein’s framework of six types of involvement for comprehensive programs of partnership and sample practices.

European families today, thanks to de-traditionalization, are not the institutions they were a few decades ago. Roles and relationships are more fluid and negotiable [35]. As a result of globalization and changing legislation, there are increasing numbers of inter-ethnic and inter-racial relationships and marriages, making ethnicity less of an obstacle to love and marriage [36]. A research study carried out by Valentine, Piekut, and Harris [37] found that diversity within a family produces more positive public attitudes toward the specific social group that an individual member of the family is thought to represent. However, these positive attitudes do not go beyond this specific ‘difference’ to other prejudices toward other groups. This lack of generalization again reveals the need for greater efforts at approaching the subject of diversity formally, through interventions promoting critical thinking, that connect the family to the school and the community.

Banks [38] (p. 284) suggests that when parents and teachers think of parent involvement, they think of doing something:

This involves doing something for the school, generally at the school, or having the school teach parents how to become better parents. In today’s ever-changing society, a traditional view of parent involvement inhibits rather than encourages parents and teachers to work together. Traditional ideas about parent involvement have a built-in gender and social-class bias and can be a barrier to many men and low-income parents.

Ideally, the REACT maieutic method involves parents at the same level and in the same way as their children and their children’s teachers, so that they share a similar process of critical thinking and move toward a greater tolerance of ambiguity and differences.

As mentioned above, parents consciously inform and teach children about their attitudes and values [9], but they also unconsciously model these in the ways in which they implement domestic rules, for example [39], or communicate and connect with others in their daily lives. Parents can either expose their children to people like themselves and reinforce and create what Putnam [40] calls bonding capital or enable their children to develop bridging capital by giving them the opportunity to mix with people different from themselves. This of course can work both ways and children can also influence and modify other generations’ attitudes. The tendency is toward bonding capital, which again highlights the need for specific and explicit pedagogies to develop intercultural competences.

Recommendations regarding the role of parents in children’s acquisition of intercultural competences exist at national, European, and international levels, as mentioned above. They call for a more student-centered approach to learning, a greater involvement of families in the process, a greater use of maieutic or dialogic methods, and experiential learning, with the aim of connecting theory to everyday life. Teacher training involving awareness raising and the questioning of teachers’ own prejudices and stereotypes and dealing with controversial issues is also considered key [41]. The OECD has emphasized the need for innovation when it comes to engaging parents, highlighting their significant role in students’ academic success [42]. This involvement is not only related to academic or cognitive achievement, but also to behavioral, emotional, and social skills [43].

In their review of parent involvement, Henderson and Mapp [44] also found evidence that parental involvement is strongly linked not only to academic achievement but also to improvements in areas such as behavior and social skills. Parents should be able to contribute to improvement in school in all of these areas by working in different ways and in different settings. In another review of the literature related to inclusive education, Reyes Parra, Moreno, Ruiz, and Avendaño [45] concluded that insufficient attention has generally been given to processes within the family nucleus that foment inclusiveness, and that although work has been carried out with all of the separate actors in the educational community (policy makers, institutions, teachers, students, parents), there remains work to be done in forming networks between them [46,47].

Of course, parents also require training in their educational role. However, according to Allport [9], there may be a lack of channels that enable parents to share their concerns and questions with professionals and other parents. Proposals for training like this may be met with a low response rate if they are organized with no active parent involvement. This situation may cause parents to seek out members of their ‘intimate’ network, rather than professionals, when attempting to resolve conflicts with their children, mostly in early adolescence [46].

Parental involvement in education is hard to define as it includes so many different settings, behaviors, as well as different spheres, and much current research is based on Epstein’s model of parental involvement which considers these multiple settings. A small section of the framework is seen in Table 1.

Epstein et al. [1] identified six ways in which parents could be involved in their child’s education: (1) parenting, (2) communicating, (3) volunteering, (4) learning at home, (5) decision making, and (6) collaborating with the community. All of these different types of involvement allow parents to influence their child’s time at school positively. Ongoing research on parental involvement has often been drawn from this model by Epstein that describes the teacher–parent relationship as based on communication and cooperation and parental involvement as malleable depending on the practices of teachers, administrators, other parents, and students. The model covered what Epstein called ‘overlapping spheres of influence’, groups that influence student learning. At first, these were school and families, and later, the spheres were extended to include community. Research on family involvement started in the 1980s and challenged established theories of social organization which affirmed that “organizations were most effective when they operated independently and separately” [48] (p. 633). However, further and intensive work from Epstein in the field of sociology and psychology and research on school and parental involvement and their effects concludes that the more interaction that exists between parents, educators, and community and the more they exchange information and help each other, the better they can help students to succeed in their schooling [48]. The effect of parental involvement has been the focus of studies for some time, particularly in terms of how providing support and a nurturing home learning environment influences the achievement and cognitive development of children, youth, and even young adults [49]. There is also research to suggest that to improve parent involvement and multicultural education in schools, a strong school leadership is needed [48].

Parental involvement has many forms. It can, of course, be directed to improving cognitive gains when implementing school-like activities at home, fostering the continuity of classroom learning in the form of monitoring homework. However, parents also directly, or indirectly, shape their children’s value system, as well as their orientation to their learning [20]. Implementing parental involvement practices designed to improve the social/emotional/reasoning skills of children implies that parents go a step further and purposely lay a foundation of skills, values, and attitudes to foster those social/emotional/critical competencies that children need to succeed. This may include fostering empathy and self-perception, with parents interacting with children in a multi-level environment. This is exactly what the REACT project aims to do with the development of reciprocal maieutic laboratories. Moreover, a review of the literature suggests that social/emotional and critical skills are highly related to the development of prosocial behaviors and a reduction in antisocial behavior in elementary and middle school pupils [50]. Thus, an important set of activities to foster these skills—such as relationship building, working cooperatively, and impulse control—should be integrated into the parent–child–teacher relationship. The REACT project aims to update the traditional idea of parent involvement in school life, overcoming the ineffective concept of unidirectional school planning and the passive participation of parents in initiatives that are not developed using a proactive methodology. The reciprocal maieutic approach (RMA) will make parents part of the change, putting them at the core of activities from the beginning: starting with the pre-test of the biographic questionnaire, piloting workshops, and the post-evaluation of the activities. Parents will have the chance to discover who their children are outside the home and inside the classroom while they debate, negotiate meaning, and explore their own ideas. Parents will put themselves in their children’s shoes and be able to know how they feel when called on to unveil their inner needs, their ambitions, their fears, and their perceptions. This process represents the first level of cognitive empathy, understanding others and their daily circumstances (the classroom, the learning environment, the teachers, their mates, and peers). In parallel, parents will be called upon to do the same, dismantling the daily role of adults in a hierarchical educative relation with their children and acting as their children’s peers. In addition, the RMA will change the way parents perceive their educational role thanks to their participation in activities that will help them to share their inner needs relating to their educational role. But not only that, this long-term pathway will also build in parents a sense of self-confidence and trust in school staff and educative staff, thus contributing to breaking the circle of ‘intimate’ networking activation when a difficulty or need arises within the family environment. It is expected that the relationship among students, teachers, and parents will be sensitively modified, enriched, and reinforced thanks to participation in reciprocal maieutic laboratories in a structured and long-term program.

3. Materials and Methods

The main objective of this study was to explore how cultural diversity affects young people at school and in daily life and how parents influence them when educating their children about it. A quantitative methodology was used to collect data. The tools used were online surveys. The results of the group studied, in this case parents, can be generalized, and situations about this population can be affirmed, as the data, in line with Creswell [51], are analyzed using numbers and statistics.

3.1. Tool

An online survey was used for this study. There were 21 questions: the first 8 questions were about demographic data; then, 15 questions used a Likert scale, with 5 dimensions from strongly disagree to totally agree. The last question was open-ended.

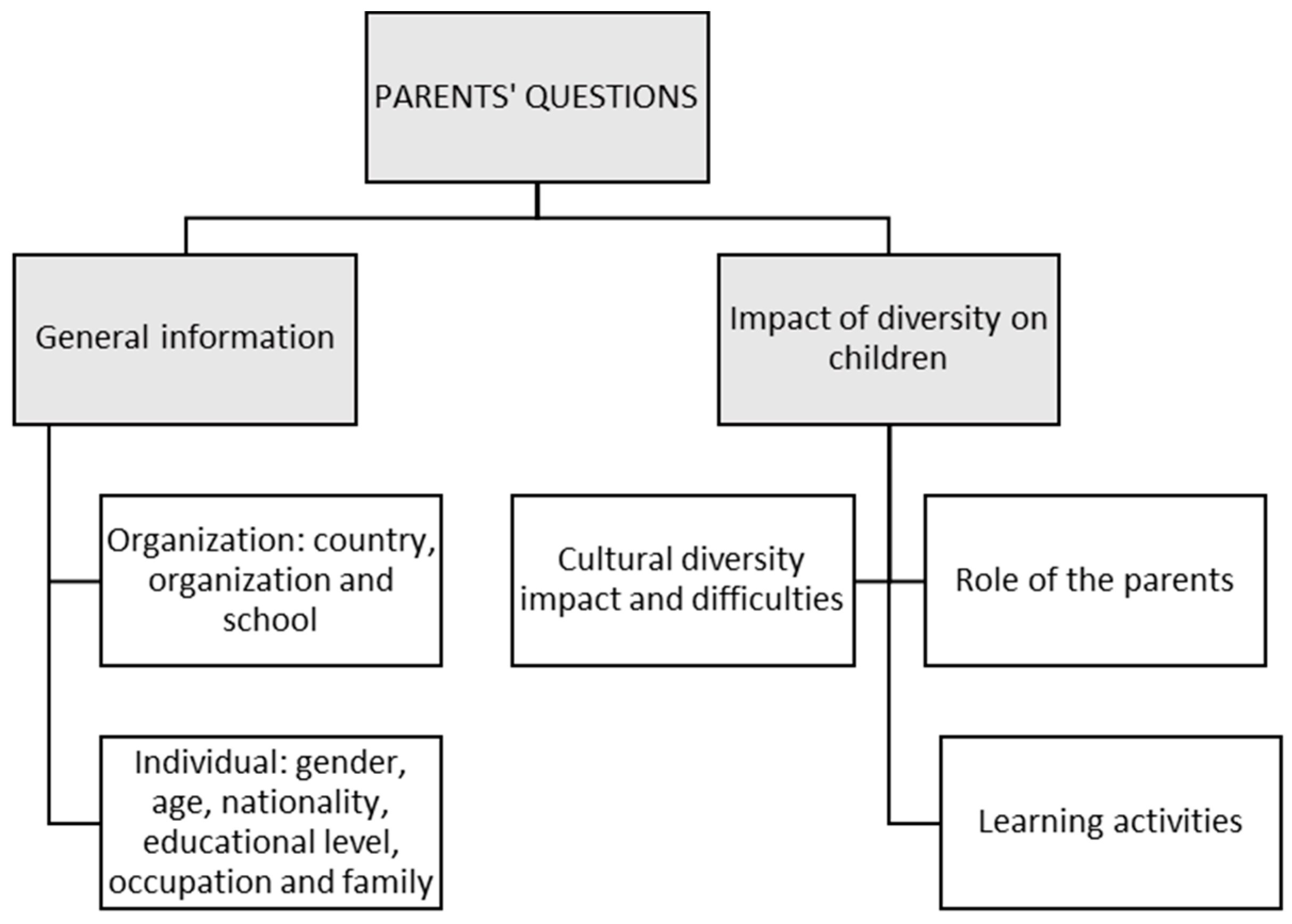

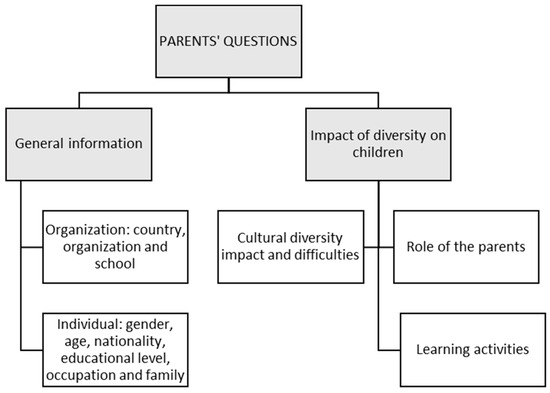

Figure 1 represents the structure of the questionnaire given to parents. The survey was validated in each country. Before the final distribution, 10 parents from each country completed the survey, and their feedback on the complexity of the questions, language adaptation, or other detected difficulties was collected. Based on these results, the questionnaire was refined, resulting in the final version that was administered for this study.

Figure 1.

Parents’ survey concept map. Source: own elaboration.

3.2. Participants

Two hundred and forty-three participants answered the survey. Roughly two-thirds of those surveyed were women (one hundred and fifty-six participants). The average age was approximately 47.4 years, with a standard deviation of 6.042, indicating notable diversity within the sample. In total, parents from 46 different schools participated in this study.

The nationality distribution of the parents primarily centers around the countries represented by the project partners, with twice as many Italians accounted for due to the presence of two participating institutions originating there, as shown in Table 2 and Table 3.

Table 2.

Participants by country.

Table 3.

Distribution by nationality.

The sample used and the diversity within the parent population are significant for this study. Quantitative methodology was considered the best methodology to analyze parent involvement and its influence in educating their children about cultural diversity.

4. Results

4.1. How Do Parents Perceive the Impact of Cultural Diversity on Their Children?

As shown in Table 4 below, assessment of the perceived influence of cultural diversity on the children of the parents in the sample involved analyzing responses to two primary inquiries. Initially, parents were prompted to express their level of agreement with three statements regarding the anticipated effects of cultural diversity on their children. Participants utilized a five-point Likert scale, ranging from “Strongly Disagree” to “Strongly Agree”, to assess their agreement with each statement.

Table 4.

Perceived impact of cultural diversity on parents’ children.

The results indicate a strong consensus among parents regarding the positive influence of cultural diversity on the development of their children, as illustrated in Table 4. Specifically, parents believe that their children are adept at navigating cultural diversity, with 77.0% indicating agreement. Additionally, the majority (82.3%) asserts that cultural diversity has not exacerbated conflict or violent attitudes in their children.

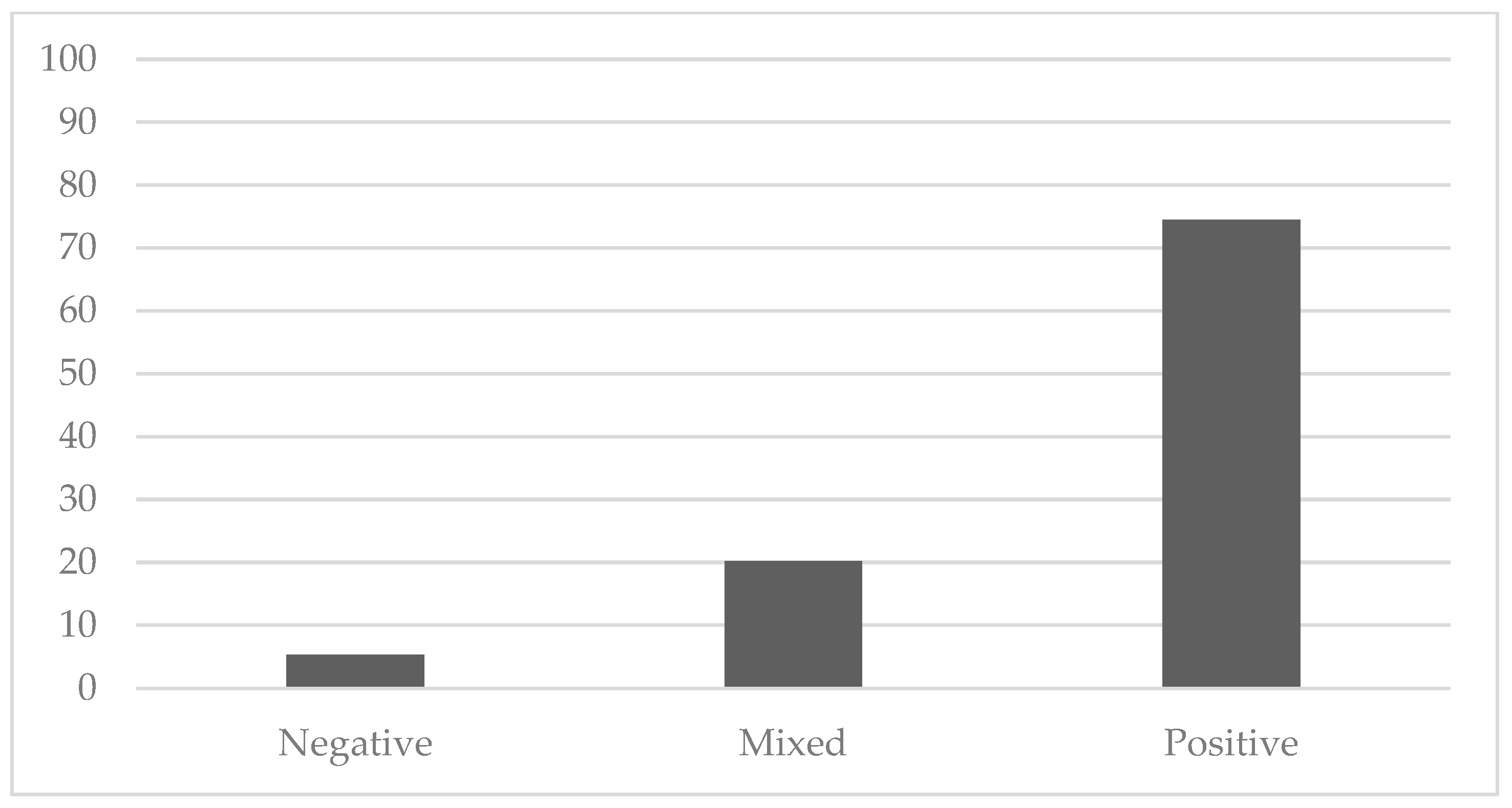

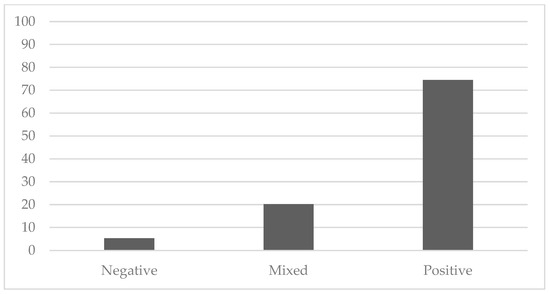

Furthermore, Figure 2, below highlights that a significant majority of respondents (74.5%) perceive cultural diversity as having a positive impact on their children.

Figure 2.

The impact of cultural diversity. Source: own elaboration.

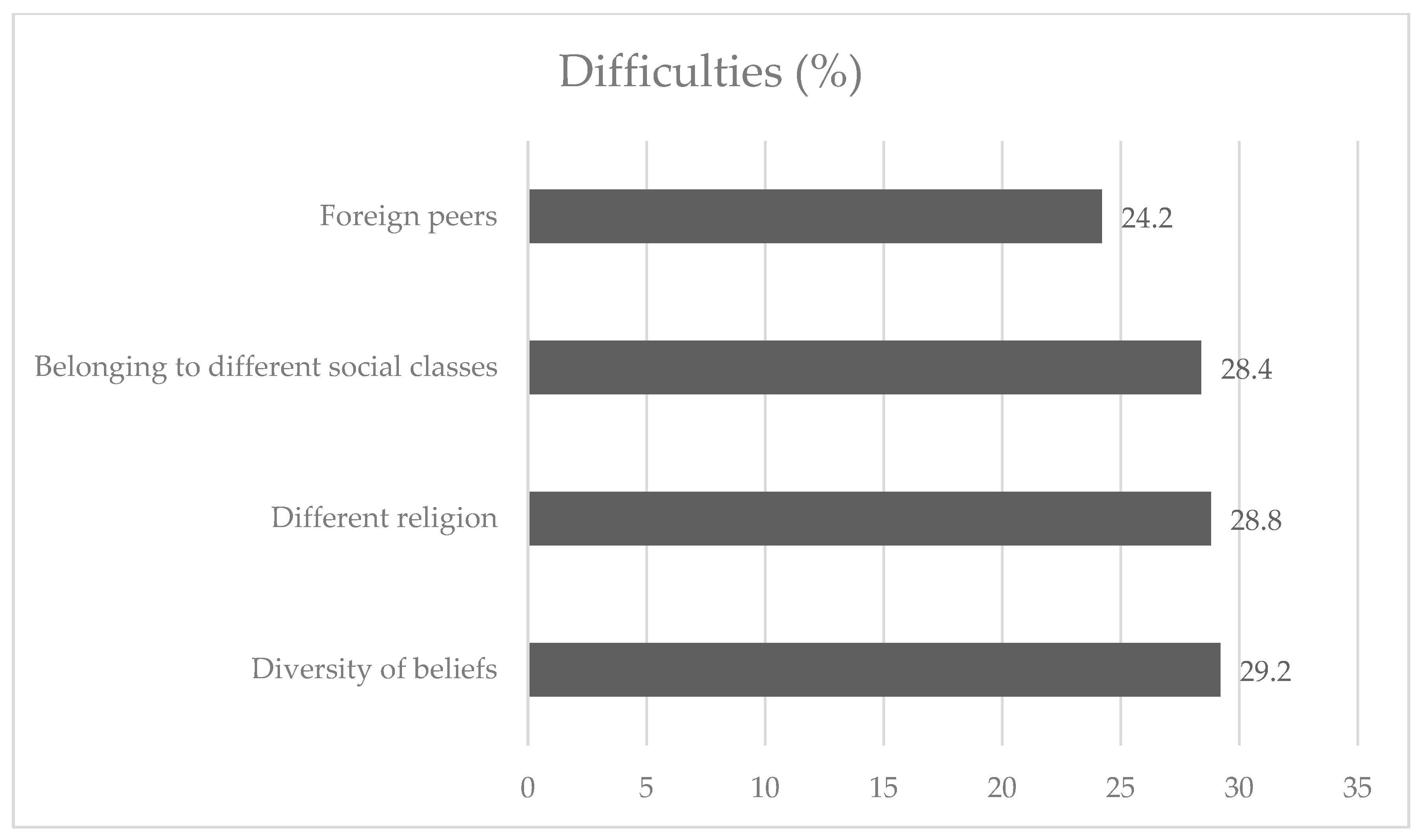

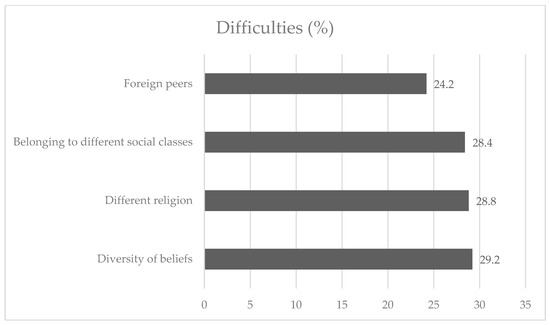

The subsequent question in this section of the questionnaire aimed to gather parents’ perspectives on the challenges their children might encounter when interacting with individuals from diverse cultures, beliefs, and backgrounds. Respondents were tasked with assessing, on a scale ranging from “Not at all” to “Very much”, the extent to which they believed their children could encounter difficulties related to cultural and social diversity when engaging with foreign peers, individuals with different sexual orientations, a variety of beliefs, membership of different social classes, and adherence to different religions.

Table 5 shows that parents generally perceive that their children face minimal difficulty in engaging with various cultures, beliefs, religions, and sexual orientations, as evidenced by the combined percentages of “Not at all” and “Little” exceeding 70% across all analyzed items. However, for a deeper exploration of potential challenges in this regard, the following graph presents a ranking of items based on the summation of responses from “Some extent” to “Very much”.

Table 5.

Difficulties regarding cultural diversity related to various factors.

As can be inferred from Figure 3, the results indicate that diversity of beliefs (29.2%), different religions (28.8%), and belonging to different social classes (28.4%) are the primary differences that could potentially pose challenges for the children of the respondents.

Figure 3.

Difficulties regarding cultural and social diversity. Source: own elaboration.

4.2. How Do Parents Perceive Their Role in Their Children’s Perception of Cultural Diversity?

The content analysis examined the following open-ended question: “Based on your experience, what role do parents play in aiding their children to navigate cultural diversity?”.

As Table 6 shows, parents provided insightful, diverse, and well-articulated responses. Upon conducting the content analysis, recurrent themes emerged from their feedback, with representative answers from parents included for each category. According to the findings, parents perceive their main role as follows:

Table 6.

Content analysis of open-ended questions.

- Guiding their children’s understanding of cultural diversity by serving as role models and imparting values and attitudes that highlight the positivity and enrichment associated with it (16.8%): “Parents, we are role models. We need to teach and transmit to our sons and daughters’ values, attitudes…we need to show them that cultural diversity is very positive and enriching”.

- Engaging in open and prejudice-free conversations with their children (14.7%): “Talk with them openly and freely, without prejudices”.

- Setting a positive example for their children and fostering a constructive attitude toward cultural diversity (14.4%): “We as parents should be the first positive example for our children and positively relate to cultural diversities”.

- Educating their children about tolerance and respect, emphasizing the importance of appreciating individual uniqueness and promoting mutual respect (12.0%): “Parents can help their children acquire values such as acceptance and tolerance by understanding that each of us is unique and should respect one another”.

4.3. What Activities Do Parents Believe Have the Greatest Impact on Developing Strong Intercultural Competence?

The final question prompted participants to rate, using a five-point Likert scale ranging from “Totally disagree” to “Absolutely agree”, the extent to which they believed a series of activities could aid in their children’s learning and enhancement of skills to engage with, accept, and respect cultural diversity.

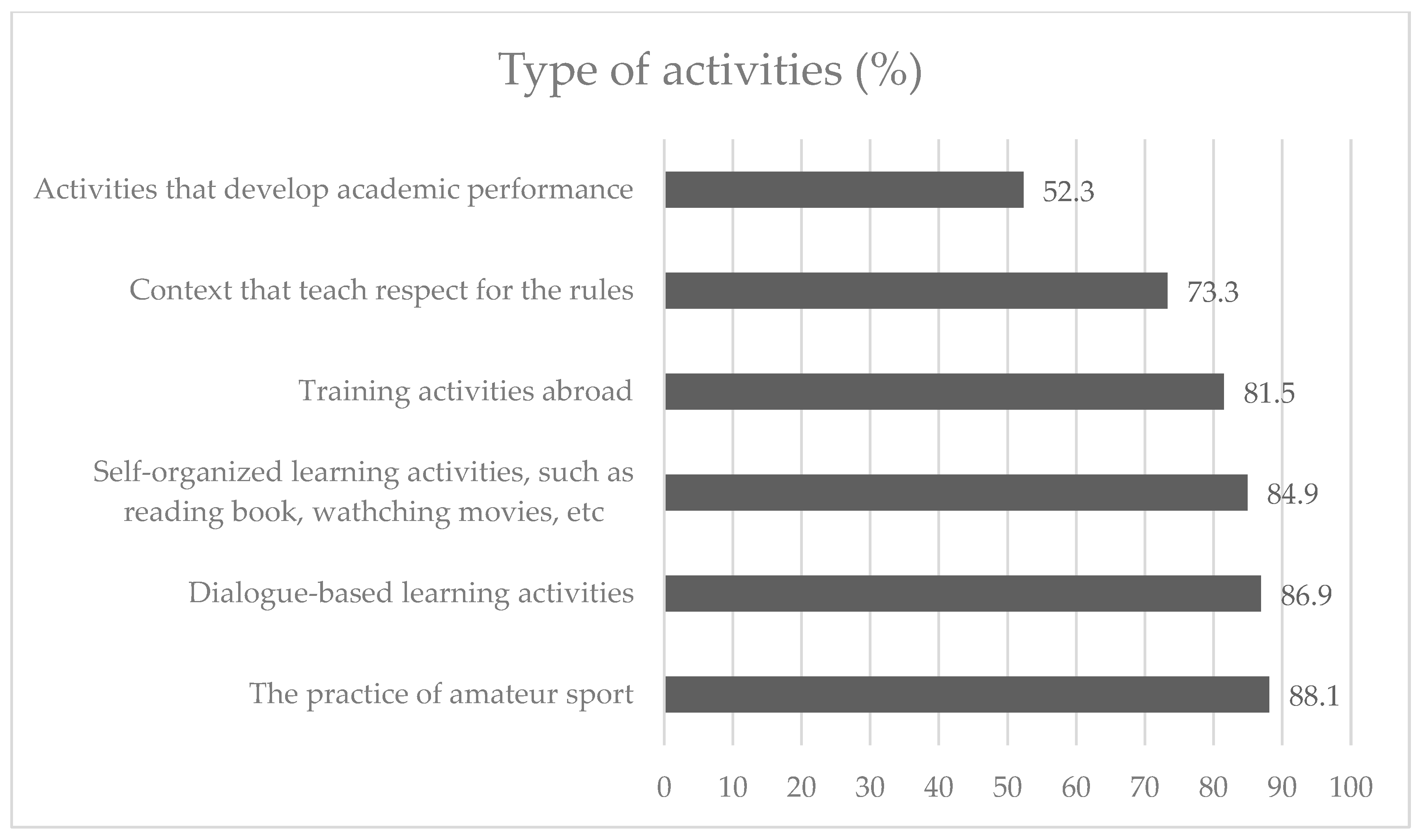

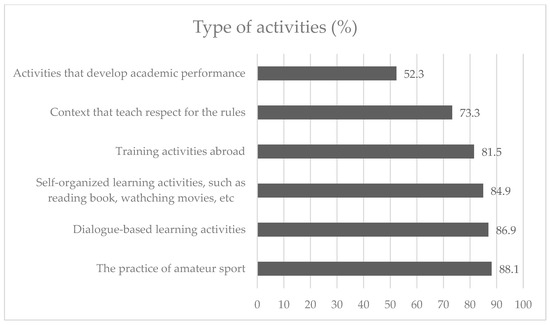

According to the data presented in Table 7, and below in Figure 4, parents believe that the most effective method for enhancing cultural diversity skills is engaging in amateur sports, with a combined percentage of 88.1% indicating “Absolutely agree” or “Agree enough”.

Table 7.

Best learning activities to improve ability to relate to cultural diversity.

Figure 4.

Best learning activities to improve ability to relate to cultural diversity. Source: own elaboration.

Additionally, other learning activities that garnered high-approval ratings include dialogue-based learning activities (84.4%), self-organized learning activities (84.9%), training activities abroad (81.5%), and environments that emphasize respect for rules (73.3%).

Conversely, activities related to improving academic performance are perceived as the weakest in enhancing the ability to relate to cultural diversity, with only 52.3% of respondents expressing approval. Notably, this item also received the highest percentage of “I do not know” responses, at 27.6%.

To sum up, the findings from this study underscore the generally positive perception among parents regarding the impact of cultural diversity on their children, highlighting an appreciation for the enriching experience it provides. Parents acknowledge their pivotal role in guiding their children through the complexities of cultural diversity, emphasizing the importance of teaching, discussing, and exemplifying values of tolerance and respect. The present study also reveals a consensus on the effectiveness of experiential and participatory activities, such as amateur sports and dialogue-based learning, in fostering intercultural competencies, as opposed to traditional academic approaches.

5. Discussion

While parents generally hold positive views on the influence of cultural diversity on their children and perceive minimal difficulty in engagement with it, they also recognize specific areas where challenges may be more prevalent. These insights can inform efforts to support children in navigating cultural diversity effectively while addressing potential areas of concern. The unanimous perception among parents regarding the beneficial impact of cultural diversity on children’s development reflects the core principles of Allport’s [9] theory of intergroup contact. Allport posited that properly structured and controlled contact between culturally diverse groups could mitigate prejudice. This premise is supported by this study’s findings, underscoring the necessity for educational practices that not only encourage diverse interactions but also frame these interactions within contexts that fulfil Allport’s criteria for positive outcomes—equal status, common goals, cooperation, and support from authority figures, principles that echo the controlled interactions suggested by Nesdale and Todd [12].

Parents recognize the variety of important roles that they play in supporting their children to navigate cultural diversity. These roles include educating children about cultural diversity, engaging in open dialogue, setting positive examples, and promoting tolerance and respect. There is an emphasis on educating children about cultural diversity and engaging in open conversations. Parents understand the significance of providing their children with knowledge and understanding of cultural differences, and fostering an environment where open dialogue can take place. The findings emphasize the critical role that parents play in shaping their children’s perceptions of cultural diversity, echoing Epstein’s [1] overlapping spheres of influence model. This model suggests that the most effective learning environments are those that extend beyond the classroom to involve families and the wider educational community, fostering a holistic educational approach. Parents’ involvement, as highlighted in this study, spans from serving as role models to actively engaging in dialogue about cultural diversity, reinforcing the Montessori principle of learning through doing and experiencing, which is central to the reciprocal maieutic approach (RMA), a sentiment echoed by Banks and Banks [20] in their holistic approach to multicultural education and the ways to embrace and accept diversity.

Parents acknowledge the importance of leading by example. They recognize that their own attitudes and behaviors toward cultural diversity significantly influence their children’s perceptions and attitudes. Therefore, they emphasize the need to be positive role models and demonstrate acceptance and respect for diversity. Teaching children tolerance and respect toward others is seen as crucial. Parents understand the importance of instilling values that promote the acceptance of individual uniqueness and mutual respect among their children.

In terms of collaboration with the social environment, while the focus is primarily on parental roles, some respondents also mention the significance of the social environment in supporting children to navigate cultural diversity. This suggests an awareness of the broader influences that contribute to children’s understanding and acceptance of diversity. Wood and Beck [39] further elaborate on this concept by discussing how parents can either expose their children to homogeneity, reinforcing what Putnam [40] describes as “bonding capital”, or how they can facilitate their children’s development of “bridging capital” by giving them opportunities to engage with people different from themselves. Although some parents recognize the importance of cooperating with the school, this area was not perceived by most parents as an essential part of their role in educating their children about tolerance and respect for the ‘other’ [46]. This would seem to support previously mentioned ideas that parents continue to perceive their role and the school’s role as separate, disregarding Epstein’s theory of ‘overlapping spheres’. It appears clear that work is necessary to bring the school and family together in more effective and proactive ways. The REACT approach is again a useful tool, providing school/parent interaction and communication on equal terms.

Critical thinking was mentioned by a relatively small number of parents, perhaps because they associate it more with academic aspects of learning than with the development of intercultural competence, tolerance, or inclusiveness. The connection of critical thinking to soft skills perhaps needs to be made more explicit to parents. Again, the React approach provides an effective means of achieving this.

In short, responses seem to indicate that parents continue to view their role as, in many ways, separate from the school and community [46]. Work must be done to foster a greater, more productive connection between parents and the school.

In terms of the activities with the greatest impact on developing strong intercultural competence, parents expressed a preference for active and experiential learning approaches, such as engaging in amateur sports, dialogue-based learning, and self-organized activities, as effective methods for enhancing their children’s cultural diversity skills. This suggests a belief that hands-on experiences and interactive learning environments are more conducive to developing these skills than passive instructional methods. The preference for experiential learning activities over traditional academic approaches to develop intercultural competence reflects a broader educational shift. This shift is toward methodologies that prioritize active, participatory learning experiences, such as those advocated by Banks and Banks [20], Deardorff [7], and Sierra-Huedoand Nevado Llopis [18]. These activities, including amateur sports and dialogue-based learning, not only facilitate intercultural understanding but also embody the pedagogical principles necessary for effective intercultural education [17]. They allow students to engage directly with diversity, challenging their preconceptions and fostering empathy, a critical component of intercultural competence [16]. Such an approach resonates with the educational strategies espoused by Johnson and Johnson [14] in their cooperative learning model, which underlines the importance of interaction and collaboration among students from diverse backgrounds to enhance significant learning.

Parents’ perceptions and preferences in general indicate a move away from traditional teacher-centered learning toward more student-centered, experiential, active learning as an effective means to acquire the competences necessary to succeed in an increasingly intercultural world, which is directly linked to acquiring soft competences such as intercultural competence and critical thinking [17].

While the present study paints a broadly positive picture, it does not shy away from acknowledging the challenges inherent in navigating cultural diversity, especially around beliefs, religions, and social classes. Addressing these challenges necessitates a nuanced understanding of cultural dynamics, as highlighted by Galanti [24] and Bennett [23], who discuss the complexity of stereotypes and the importance of developing sophisticated cultural navigational skills. Future educational initiatives should, therefore, prioritize the development of curricula and pedagogies that are responsive to the complexities of cultural diversity, guided by the insights of Aguado-Odina [6], Budginaitė-Mačkinė et al. [26], and Sierra-Huedo et al. [16], who advocate an education system that is inclusive, empathetic, and capable of transforming diversity into a pedagogical asset.

Many studies conducted in this area highlight that to obtain real involvement of parents in an intercultural education program in a school, strong school leadership is needed. According to Banks and Banks [20] it is key for a better future of schooling to learn how to transform diversity into a pedagogical asset; it is crucial to equip schools with effective teaching methods to address diversity. This means not rejecting diversity, treating it in isolation, or merely tolerating it. However, it also does not entail viewing diversity as a necessary burden or celebrating it without purpose. Instead, the greater challenge for the future lies in transforming recognized diversity into a pedagogical advantage.

6. Conclusions

In addressing the role of parents in cultural diversity education, this study highlights the critical position that parents hold in guiding their children through the myriad of aspects of cultural diversity. Parents identify themselves as key players in this educational journey, emphasizing the importance of being positive role models, engaging in open dialogue, setting exemplary behaviors, and imparting values of tolerance and respect. These findings reflect a broad acknowledgment among parents of their integral role in shaping their children’s attitudes and competencies regarding cultural diversity, pointing to the family as a crucial site for the cultivation of intercultural understanding.

Regarding the activities deemed most effective for developing intercultural competence, parents express a preference for active and experiential learning approaches. Activities such as amateur sports, dialogue-based learning, self-organized learning, training abroad, and those that emphasize respect for rules are highlighted as particularly beneficial in enhancing children’s skills in cultural diversity. This preference indicates a shift toward learning experiences that are interactive and participatory, as opposed to traditional academic methods which are seen as less effective in fostering an authentic connection to cultural diversity. These insights suggest that hands-on experiences and environments that encourage active participation and respect for diversity are key to developing the soft skills necessary for navigating an increasingly multicultural world.

In conclusion, this study sheds light on the positive perceptions of cultural diversity among parents and the pivotal roles they play in their children’s cultural education. It also highlights the effectiveness of experiential learning activities in developing intercultural competence. As we move forward, fostering an environment that embraces cultural diversity, supported by parental involvement and active learning experiences, is essential in preparing children to thrive in a diverse global community. The challenges identified also signal the need for continued dialogue and collaboration between families, educators, and communities to develop inclusive, empathetic, and adaptable approaches to cultural diversity education.

Adopting a multifaceted approach to enriching educational curricula with the inclusion of the reciprocal maieutic approach (RMA) underscores the strategic integration of methods aimed at fostering intercultural competences among students. This aligns with the present study’s findings, where parents recognized the importance of experiential learning activities in developing their children’s intercultural competences. The development of a specialized teaching program that includes the RMA is critical, facilitating the adaptation of teaching materials to suit varied educational environments and making the RMA a staple in teacher training programs. This resonates with the present study’s conclusion that emphasizes the crucial role of parental involvement and open dialogue in educating children about cultural diversity. Moreover, the establishment of conducive learning environments facilitated by the RMA, alongside the designation of dedicated RMA educators within schools, reflects the essential need for educational frameworks that not only encourage family and community involvement but also celebrate participatory learning over conventional teaching methods.

These strategic policy recommendations, combined with the current study’s findings, mark a collective move toward more inclusive, empathetic, and adaptable educational initiatives that prioritize active participation, critical thinking, and the rich tapestry of cultural diversity.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.L.S.-H. and A.C.R.; methodology, M.L.S.-H.; formal analysis, A.C.R. and L.A.B.; investigation, M.L.S.-H., A.C.R. and L.A.B.; writing—original draft preparation, M.L.S.-H. and L.A.B.; writing—review and editing, L.A.B.; supervision, A.C.R.; project administration, M.L.S.-H.; funding acquisition, M.L.S.-H. and A.C.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research formed part of the European project “Reciprocal maieutic Approach pathways enhancing Critical Thinking (REACT)”, Erasmus+ K3 EACEA/38/2019, number 621522-EPP-1-2020-1-IT-EPPKA3-IPI-SOC-IN, funded by the European Union.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration and complying with Regulation (EU) 2016/679 of the European Parliament and of the Council, dated 27 April 2016, for the protection of individuals with regard to the processing of personal data. All legal representatives of the participating educational centers signed the “Memorandum of Understanding”, which established the collaboration framework for this project. This protocol is included in the EU approval of the project, as well as the ethics considerations.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in this study.

Data Availability Statement

The data will be available upon request.

Acknowledgments

We would like to give special thanks to our Research Group “Migraciones, Interculturalidad y Desarrollo Humano” (Universidad San Jorge), as well our partners colleges in the project consortium.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of the data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Epstein, J.L.; Sanders, M.G.; Sheldon, S.B.; Simon, B.S.; Salinas, K.C.; Jansorn, N.R.; Van Voorhis, F.L.; Martin, C.S.; Thomas, B.G.; Greenfeld, M.D.; et al. School, Family, and Community Partnerships: Your Handbook for Action, 3rd ed.; Corwin, a SAGE Publications Company: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2008; ISBN 978-1-5063-9134-2. [Google Scholar]

- Benelli, C.; Schachter, C. Paulo Freire e Danilo Dolci: Connessioni Metodologiche. Sapere Pedagog. Prat. Educ. 2017, 2017, 193–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paseka, A.; Byrne, D. (Eds.) Parental Involvement across European Education Systems: Critical Perspectives; Routledge research in international and comparative education; First issued in paperback; Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2021; ISBN 978-1-03-208949-2. [Google Scholar]

- Domina, T. Leveling the Home Advantage: Assessing the Effectiveness of Parental Involvement in Elementary School. Sociol. Educ. 2005, 78, 233–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eurydice (European Education and Culture Executive Agency). Developing Key Competences at School in Europe—Challenges and Opportunities for Policy; Publications Office: Brussels, Belgium, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Aguado-Odina, T. Investigación En Educación Intercultural. ESXXI 2004, 22, 39–57. [Google Scholar]

- Deardorff, D.K. The SAGE Handbook of Intercultural Competence; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Aguado, M.T.; Sleeter, C. Educación Intercultural En La Práctica Escolar. Cómo Hacerla Posible. Profr. Rev. Curríc. Form. Profr. 2021, 25, 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Allport, G.W. The Nature of Prejudice; Addison-Wesley Publishing Company, Inc.: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1954. [Google Scholar]

- Cernadas Ríos, F.X.; Lorenzo Moledo, M.D.M.; Santos Rego, M.Á. La Educación Intercultural En España (2010–2019). Una Revisión de La Investigación En Revistas Científicas. Med. Segur. Trab. 2021, 51, 329–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garreta-Bochaca, J.; Macia-Bordalba, M.; Llevot-Calvet, N. Educación Intercultural En Cataluña (España): Evolución de Los Discursos y de Las Prácticas (2000–2016). Estud. Sobre Educ. 2020, 38, 191–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nesdale, D.; Todd, P. Effect of Contact on Intercultural Acceptance: A Field Study. Int. J. Intercult. Relat. 2000, 24, 341–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torrelles Montanuy, À.; Cerviño Abeledo, I.; Lasheras Lalana, P. Educación Intercultural En España: Enfoques de Los Discursos y Prácticas En Educación Primaria. Profesorado 2022, 26, 367–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, D.W.; Johnson, R.T. Learning Together and Alone. Cooperative, Competitive, and Individualistic Learning, 4th ed.; Allyn and Bacon: Needham Heights, MA, USA, 1994; ISBN 978-0-205-15575-0. [Google Scholar]

- Nussbaum, M.C. Crear Capacidades: Propuesta Para El Desarrollo Humano; Ediciones Paidós: Barcelona, Spain, 2012; ISBN 978-84-493-0988-5. [Google Scholar]

- Sierra-Huedo, M.L.; Bruton, L.; Fernández, C. Becoming Global at Home: An Analysis of Existing Cases and A Proposal for the Future of Internationalization at Home. J. Educ. 2024, 204, 241–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vande-Berg, M.; Paige, R.M.; Lou, K.H. Student Learning Abroad: What Our Students Are Learning, What They’re Not, and What We Can Do About It; Routledge: Sterling, VA, USA, 2012; ISBN 978-1-57922-714-2. [Google Scholar]

- Sierra-Huedo, M.L.; Nevado-Llopis, A. How Could We Prepare Our Students to Become Interculturally Competent? In Rethinking Intercultural Competence: Theoretical Challenges and Practical Issues; Witte, A., Harden, T., Eds.; Intercultural studies and foreign language learning; Peter Lang: Oxford, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2021; pp. 241–249. ISBN 978-1-80079-171-8. [Google Scholar]

- Besalú-Costa, X. Claves para interculturalizar los centros educativos. In Políticas Públicas Frente a la Exclusión Educativa: Educación, Inclusión y Territorio; García, D., Gimeno, C., Dieste, B., Blasco, A.C., Eds.; Prensas de la Universidad de Zaragoza: Zaragoza, Spain, 2020; pp. 64–70. ISBN 978-84-13-40138-6. [Google Scholar]

- Banks, J.A.; Banks, C.A.M. (Eds.) Handbook of Research on Multicultural Education, 2nd ed.; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2004; ISBN 978-0-7879-5915-9. [Google Scholar]

- Branch, A. Ethnic Identity Discourse in Intercultural Education. Profesorado 2021, 25, 69–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunow, B.; Newman, B. A Developmental Model of Intercultural Competence: Scaffolding the Shift from Culture-Specific to Culture-General. In Diversity and Decolonization in German Studies; Criser, R., Malakaj, E., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 139–156. ISBN 978-3-030-34341-5. [Google Scholar]

- Bennett, M.J. Basic Concepts of Intercultural Communication: Paradigms, Principles, and Practices, 2nd ed.; Nicholas Brealey: Boston, MA, USA, 2013; ISBN 978-0-9839558-4-9. [Google Scholar]

- Galanti, G.-A. An Introduction to Cultural Differences. West. J. Med. 2000, 172, 335–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paige, R.M.; Cohen, A.D.; Kappler, B.; Chi, J.C.; Lassegard, J.P. Maximizing Study Abroad: A Students’ Guide to Strategies for Language and Culture Learning and Use; Center for Advanced Research on Language Acquisition, University of Minnesota: Minneapolis, MN, USA, 2002; ISBN 978-0-9722545-5-7. [Google Scholar]

- Budginaitė-Mačkinė, I.; Siarova, H.; Sternadel, D.; Mackonytė, G.; Algirdas Spurga, S. Policies and Practices for Equality and Inclusion in and through Education; NESET II Analytical Report; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Stoycheva, K. Intolerance, Uncertainty, and Individual Behaviour in Ambiguous Situations. In A Place, a Time and an Opportunity for Growth. Bulgarian Scholars at NIAS; Stoycheva, K., Kostov, A., Eds.; Faber: Veliko Tarnovo, Bulgaria, 2011; pp. 63–73. ISBN 978-954-400-563-4. [Google Scholar]

- Stanley Budner, N.Y. Intolerance of Ambiguity as a Personality Variable. J. Personal. 1962, 30, 29–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geller, G.; Tambor, E.S.; Chase, G.A.; Holtzman, N.A. Measuring Physicians’ Tolerance for Ambiguity and Its Relationship to Their Reported Practices Regarding Genetic Testing. Med. Care 1993, 31, 989–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aguareles, M.; Nevado Llopis, A. Liderazgo y Negociación Entre Culturas y El Papel de La Competencia Intercultural: Resultados Preliminares de Un Estudio Centrado En El Sector de La Educación Internacional En España. Entreculturas 2024, 14, 39–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahneman, D. Thinking, Fast and Slow; Farrar, Straus and Giroux: New York, NY, USA, 2011; p. 499. ISBN 978-0-374-27563-1. [Google Scholar]

- Ciccarelli, S.K.; Meyer, G.E. Psychology; Pearson Education: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2006; p. 597. ISBN 0-13-183959-4. [Google Scholar]

- Vygotsky, L.S. Mind in Society: Development of Higher Psychological Processes; Cole, M., Jolm-Steiner, V., Scribner, S., Souberman, E., Eds.; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1980; ISBN 978-0-674-07668-6. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura, A. Self-Efficacy: The Exercise of Control; W H Freeman/Times Books/Henry Holt & Co: New York, NY, USA, 1997; p. 9. ISBN 978-0-7167-2626-5. [Google Scholar]

- Beck, U.; Beck-Gernsheim, E. Individualization: Institutionalized Individualism and Its Social and Political Consequences; SAGE Publications Ltd.: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2002; ISBN 978-0-7619-6111-6. [Google Scholar]

- Waters, M. Immigration, Intermarriage, and the Challenges of Measuring Racial/Ethnic Identities. Am. J. Public Health 2000, 90, 1735–1737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valentine, G.; Piekut, A.; Harris, C. Intimate Encounters: The Negotiation of Difference within the Family and Its Implications for Social Relations in Public Space. Geogr. J. 2015, 181, 280–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banks, C.A.M. Communities, Families, and Educators Working Together for School Improvement. In Multicultural Education: Issues and Perspectives; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2015; pp. 275–292. ISBN 978-1-119-35526-7. [Google Scholar]

- Wood, P.D.; Beck, P.R.J. Home Rules; The Johns Hopkins University Press: Baltimore, MD, USA, 1994; ISBN 978-0-8018-4618-2. [Google Scholar]

- Putnam, R.D. Bowling Alone: America’s Declining Social Capital. JOD 1995, 6, 65–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alessi, A.; Biondo, A.; Kaplani, M.E.D.; Agaidyan, O.; Xala, X.; Duzgun, O.; Schultz, H.; Feldman, M.; Ferogh, L.; Schwäbe, S.; et al. Radicalisation Prevention Programme|Practice. Available online: https://practice-school.eu/oer-radicalisation-prevention-programme/ (accessed on 9 April 2024).

- OECD Review Education Policies—Education GPS—OECD: Parental Involvement. Available online: https://gpseducation.oecd.org/revieweducationpolicies/#!node=41727&filter=all (accessed on 11 April 2024).

- El Nokali, N.E.; Bachman, H.J.; Votruba-Drzal, E. Parent Involvement and Children’s Academic and Social Development in Elementary School. Child. Dev. 2010, 81, 988–1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henderson, A.T.; Mapp, K.L. A New Wave of Evidence: The Impact of School, Family, and Community Connections on Student Achievement. Annual Synthesis, 2002; National Center for Family & Community Connections with Schools, Southwest Educational Development Laboratory: Austin, TX, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Reyes-Parra, P.A.; Moreno Castiblanco, A.N.; Amaya Ruiz, A.; Avendaño Angarita, M.Y. Educación Inclusiva: Una Revisión Sistemática de Investigaciones En Estudiantes, Docentes, Familias e Instituciones, y Sus Implicaciones Para La Orientación Educativa. REOP 2020, 31, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dotterer, A.M. Diversity and Complexity in the Theoretical and Empirical Study of Parental Involvement during Adolescence and Emerging Adulthood. Educ. Psychol. 2022, 57, 295–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, N.E. Parental Involvement in Education: Toward a More Inclusive Understanding of Parents’ Role Construction. Educ. Psychol. 2022, 57, 309–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hidalgo, N.M.; Siu, S.; Epstein, J.L. Research on Families, Schools, and Communities. In Handbook of Research on Multicultural Education; Banks, J.A., Banks, C.A.M., Eds.; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2004; pp. 631–655. ISBN 978-0-7879-5915-9. [Google Scholar]

- Melhuish, E.C.; Phan, M.B.; Sylva, K.; Sammons, P.; Siraj-Blatchford, I.; Taggart, B. Effects of the Home Learning Environment and Preschool Center Experience upon Literacy and Numeracy Development in Early Primary School. J. Soc. Issues 2008, 64, 95–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mavroveli, S.; Sánchez-Ruiz, M.J. Trait Emotional Intelligence Influences on Academic Achievement and School Behaviour: Trait Emotional Intelligence. Br. J. Educ. Psychol. 2011, 81, 112–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Creswell, J.W. Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches, 3rd ed.; Sage Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2009; p. 29. ISBN 978-1-4129-6557-6. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).