Abstract

Doctoral education has been shaped by a continuous interaction between the research community and representatives of the governmental authorities. In Sweden, doctorates were organised into structured educational programmes in 1969. In this study, the development of doctoral education in Medical Radiation Physics at Lund University, Sweden, was analysed over approximately 50 years, in terms of quantitative parameters related to throughput rate and scientific production making up the doctoral theses. Theses from two time periods (1970 to 1999 versus 2001 to 2023) were compared in terms of the total number of full papers (either accepted or in manuscript form), number of accepted full papers and number of accepted full papers as first author. For all three categories of included papers, median values were not significantly different between the two time periods while the variances were significantly smaller for the period 2001 to 2023 (level of significance 0.05). The time between admission and thesis defence decreased with time, according to linear correlation analysis, while the number of supervisors increased. Doctoral theses showed a significantly more uniform composition after a major political reform in 1998. Hence, doctoral education can be described as becoming more efficient and predictable. It is suggested that the primary causes include the introduction of individual study plans and secured personal financial support. The increased efficiency can also be problematised regarding, for example, insufficient independence and limited freedom of research.

1. Introduction

The doctoral education and the requirements for the doctoral degree or doctorate have, in many countries, been shaped by a continuous interaction between the research community and representatives of the governmental authorities [1]. This process has, obviously, differed significantly among countries, but it is not uncommon that, historically, the research doctorate was primarily granted in recognition of reaching a certain level of scientific achievements. Such a doctorate was typically awarded within the academic community, in the form of an academic rank or appointment (or ‘worthiness’) rather than as the endpoint of a structured educational programme with a set curriculum. It was also common that the scientific undertaking required for such a doctorate was quite ambitious and extensive, and the time needed to complete the work and finish the doctoral thesis was often more than a decade; according to a Swedish government official report, published in 1966, the median time, after the basic degree, for a completed doctorate in Sweden was 10 years [2]. Today, in some countries, this type of extensive academic achievement would be referred to as a higher doctorate.

During the 20th century, particularly after World War II, many countries experienced rapid technological and social development, accompanied by substantially increased needs for, and interest in, education among a large part of the general public. One important aspect was to ensure more efficient use of the so-called ‘reserve of talent’ within the population, by facilitating access to higher education [3]. Appropriate design and adequate dimensioning of higher education became important political issues [3], where the perpetuation of university traditions had to be weighed against adaptations to societal changes and the needs of the labour market. Hence, doctoral education was forced to find a balance between traditional free research and the restrictions and conformity enforced by state legislation. Such diverse, and sometimes contradicting, interests are still a reality for the stakeholders of doctoral education. Furthermore, as will be further discussed below, doctoral education is not only at the point of intersection between academia, state legislation and market forces [4,5], but it is also subject to tensions, within a given university subject area, between research and education [6].

In Sweden, the requirements for a doctoral degree were organised into structured educational programmes, corresponding to four years of full-time studies, in 1969. In the following decades, doctoral education has been subject to two major reforms, the first one in 1998 and the second one in 2007 [7]. The 1998 reform was arguably the most radical of the two, imposing stricter requirements for secured financing of the doctoral student, introducing educational objectives and emphasising a formalised detailed individual syllabus or individual study plan (ISP). The ISP is to be followed up regularly and, if necessary, altered by the higher education institute, after consultation with the doctoral student and the supervisors. The 2007 reform on higher education and qualifications was common to all levels of higher education and related, to a considerable extent, to the implementation of the European so-called Bologna Process, following the Bologna Declaration on higher education [8]. At that time, more detailed degree outcomes and learning objectives, divided into the three categories ‘knowledge and understanding’, ‘competence and skills’ and ‘judgement and approach’, were formulated for all types of degrees in the Swedish system of qualifications, including doctoral education. The term ’third-cycle education’ was introduced to describe studies at the doctoral research education level, i.e., an educational programme to be entered after studies at the advanced (second cycle) or master’s level. Obviously, further changes in state legislation and in the Higher Education Ordinance (HEO) have occurred during the period of interest to this work, and some of these are mentioned in the discussion.

There are a number of valid reasons for implementing national educational reforms [9], including, for example, adaptation to long-term societal changes, adjustment of the educational output to better match the requirements of the labour market, improvement of the private economy and social security of the students, as well as global standardisation or harmonisation of the educational system with other countries (in Sweden’s case, primarily the European Union). Finally, and above all, it is reasonable to demand that one important goal of educational reform would be to improve and assure the quality of the education in question. However, the most relevant outcomes of educational reforms in general are typically difficult to evaluate in a systematic evidence-based manner, and it is fair to conclude that such undertakings, albeit important and commendable, constitute a difficult and complex task [10].

The multidimensionality of the transformation in doctoral education has been explored in a recent review [11]. Cardoso et al. identify, among several other things, duration, outputs and structuring as relevant examples of manifestations of doctoral education transformation, and this supports the objectives of the present study. They also point out that most of the analysed reports were based on qualitative research and methodology [11], implying that complementary quantitative data are indeed warranted. In terms of thesis content, the practice of publishing results in smaller, peer-reviewed elements, rather than in the form of books/monographs has become increasingly common over time [12,13]. The scope of a number of Swedish compilation theses, issued in 2001, has been reviewed by the Swedish Research Council, but the development over time was not addressed [14].

It can, in general terms, be hypothesised that national educational reforms have resulted in changes in both the implementation and the output of doctoral education at the individual level. More specifically, it is hypothesised that the scientific components of doctoral theses, in terms of the number of papers, authorship or publication status, have been affected, as well as the actual duration of the education for the individual and the role of the supervisors. In this report, the development of doctoral education in the subject area of Medical Radiation Physics at Lund University, Sweden, is analysed over a time span of approximately 50 years, in terms of quantitative parameters related to the number of supervisors, the throughput rate of doctoral students and the scientific production making up the doctoral theses in this subject area.

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Participants and Data Set

The analysis included all individual doctoral educations completed between 1970 and 2023, leading to the degree of doctor of philosophy (PhD) in the subject area of Medical Radiation Physics, carried out, in full, at the Department of Medical Radiation Physics in Lund, Sweden, and organised within the Faculty of Science at Lund University (n = 96). For a subset of the dataset (corresponding to theses that were defended between 1990 and 2023), the date of admission to doctoral studies was available (n = 72). The age of the doctoral students being part of this analysis, at the time of the thesis defence, was 35 ± 5.5 years (mean ± standard deviation (SD), n = 96), ranging between 28 and 57 years and showing a mode of 34 years.

The requirements for doctoral studies include the completion of a scientific thesis, either a monograph or a compilation thesis. In the subject area of Medical Radiation Physics, the doctoral thesis has, with few exceptions, the format of a compilation thesis, i.e., a collection of scientific papers combined with a comprehensive summary or framework, in which the doctoral student’s work is put into a broader context and discussed in relation to other relevant work in the field. The intention is that the included papers must be publishable, but they can, in practice, be in various stages of the publication process at the time of printing of the thesis (i.e., unsubmitted manuscript, submitted manuscript, manuscript accepted for publication, or published article). Furthermore, the included papers normally show shared authorship, with the doctoral student appearing in various positions in the author list. In the subject area of Medical Radiation Physics, the first author is, under normal circumstances, assumed to have executed the majority of the work throughout the research process and to have written the first draft of the manuscript. The comprehensive summary is always expected to be the doctoral student’s independent achievement. At the Department of Medical Radiation Physics in Lund, only five doctoral theses during the period 1970–2023 have been monographs, all in the narrow time interval from 1973 to 1977.

2.2. Procedures

The date of admission (if available) and the date of thesis defence were recorded for each doctoral student included in the study.

The different components constituting the collection of scientific papers in a compilation thesis were categorised as either (i) original published or accepted article with the doctoral student as the first author (implying full peer review), (ii) original published or accepted article with the doctoral student as co-author (implying full peer review), (iii) publication in conference supplement/proceedings (potentially implying limited scope and/or limited peer review) or unpublished report (not intended for publication in a scientific journal with peer review) and (iv) submitted or unsubmitted manuscript intended for publication as original work in a scientific journal. For each individual thesis, the collection of papers was scrutinised, and the number of papers in each of the above categories was recorded.

In order to provide some coarse measure of the evolution of the student versus supervisor relationship, the number of supervisors was also recorded, based only on the person or people explicitly referred to as supervisors by the doctoral student in the acknowledgements section of the thesis.

2.3. Data Analysis

The analysis comprised the following components, related to scientific production, throughput rate and the number of supervisors:

- The mean value of the total number of papers (sum of categories (i), (ii), (iii) and (iv)) was calculated to allow for a general comparison with previous results reported by the Swedish Research Council [14].

- In the analyses of the total number of full papers (sum of categories (i), (ii) and (iv)), number of accepted papers (sum of categories (i) and (ii)) and number of accepted papers with the doctoral student as first author (category (i)), the theses were divided into two groups, one including theses completed until 1999 (representing the period before the 1998 reform) and one including theses completed between 2001 and 2023 (representing the period after the 1998 reform, i.e., with formalised ISPs and improved doctoral student financing conditions).

- The age at the time of the thesis defence was plotted as a function of the date of defence, and this relationship was investigated by linear correlation analysis. This analysis included monographs.

- For the data subset in which the date of admission to doctoral studies was available (corresponding to theses that were defended between 1990 and 2023), the following analyses were made:

- ○

- Under the assumption that the date of admission was relevant to the outcome, the age at the time of the thesis defence was plotted as a function of the date of admission. The resulting relationship was investigated using linear correlation analysis.

- ○

- The time between admission and thesis defence was calculated and plotted against the date of admission. Part-time studies or periods of leave of absence were not taken into consideration. The resulting relationship was investigated using linear correlation analysis.

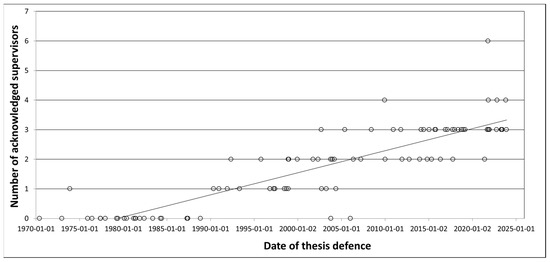

- The number of supervisors was plotted as a function of the time of the thesis defence. This analysis included monographs.

2.4. Statistics

For compilation thesis contents, the cut-off date determining the two groups was 2000-01-01 (yyyy-mm-dd). The homogeneity of variance between the two groups (1970–1999 versus 2001–2023) was tested using Levene’s test, while group median values were compared using the two-tailed Mann–Whitney U test. For age and time to thesis defence, trends over time were assessed using linear correlation analysis, as outlined above. Pearson correlation coefficients r are provided together with p-values giving the probability that one would have found the current result if the correlation coefficient were in fact zero. For all statistical analyses, the level of significance was α = 0.05.

The issue of family-wise error rates for multiple hypothesis tests was addressed using the Holm-Bonferroni method. In this study, the number of tests of a given type was 3, i.e., obtained p-values were ranked and the lowest p-value was compared with α/3 = 0.017, the second lowest p-value was compared with α/2 = 0.025, while the highest of the three p-values was compared with α/1 = 0.05.

3. Results

Recorded and extracted numerical data related to doctoral students, study duration, doctoral thesis papers and supervisors are provided as Supplementary Material in Table S1. The total number of included papers in all theses of compilation type was 5.2 ± 1.1 (mean ± SD, n = 91).

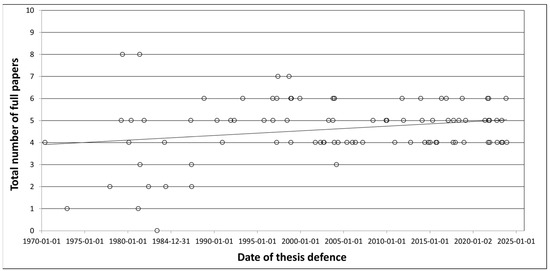

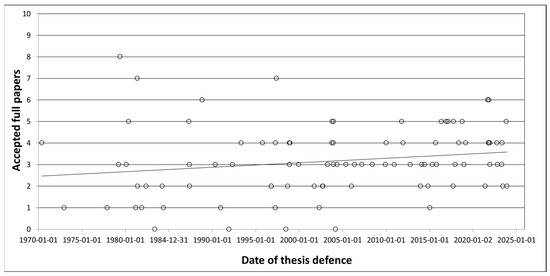

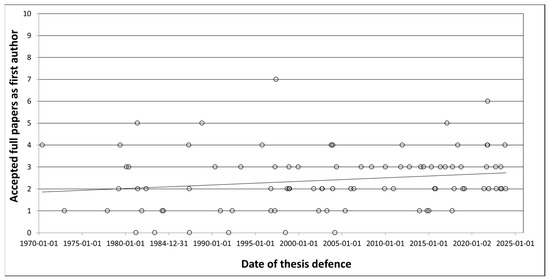

The total number of included full papers (either accepted or in manuscript) in the thesis as a function of the date of the thesis defence is plotted in Figure 1. Similar plots of the number of published/accepted papers (with the doctoral student being either first author or co-author) versus date of defence and the number of published/accepted papers with the doctoral student as a first author versus date of defence are shown in Figure 2 and Figure 3, respectively.

Figure 1.

The total number of full papers (either accepted or in manuscript) included in the thesis as a function of the date of the thesis defence. A linear regression trendline is added to visualise the slight increase.

Figure 2.

The total number of accepted full papers in the thesis as a function of the date of the thesis defence. A linear regression trendline is added to visualise the slight increase.

Figure 3.

The number of accepted full papers as the first author in the thesis as a function of the date of the thesis defence. A linear regression trendline is added to visualise the slight increase.

The average total number of full papers (either accepted or in manuscript form) in a thesis was 4.50 ± 1.91 (mean ± SD, n = 36) during the period 1970 to 1999 and 4.69 ± 0.81 (n = 55) during the period 2001–2023. The median values were not significantly different (p = 0.89), while the variances were significantly different (p = 0.0000054). The average number of accepted full papers was 2.89 ± 1.98 during the period 1970 to 1999 and 3.35 ± 1.25 during the period 2001–2023. The median values were not significantly different (p = 0.073) while the variances were significantly different (p = 0.010). The average number of accepted full papers as first author was 2.19 ± 1.61 during the period 1970 to 1999 and 2.55 ± 1.11 during the period 2001–2023. The median values were not significantly different (p = 0.13) while the variances were significantly different (p = 0.024). In the tests for homogeneity of variance, the null hypotheses were rejected while controlling the family-wise error rate at level α = 0.05.

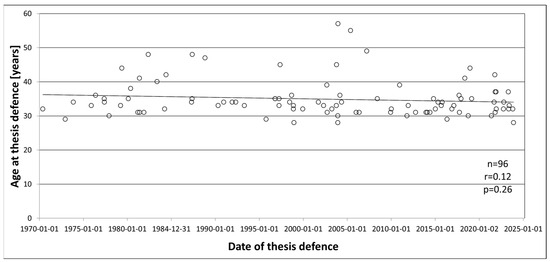

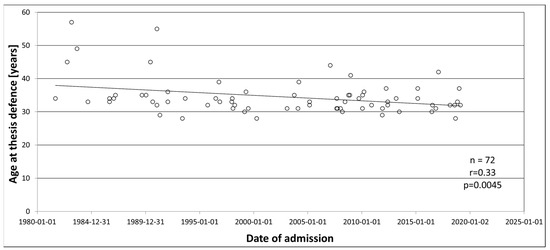

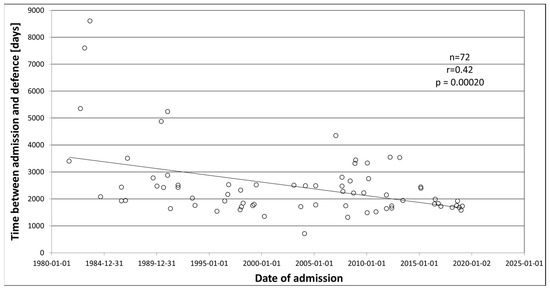

The doctoral student’s age at the time of the thesis defence decreased slightly with the date of defence, and the parameters showed a very weak and non-significant negative correlation (n = 96, r = 0.12, p = 0.26) (Figure 4). The age at the time of the thesis defence decreased more clearly when plotted as a function of the date of admission, and the parameters showed a weak but significant negative correlation (n = 72, r = 0.33, p = 0.0045) (Figure 5). The time between admission and thesis defence tended to decrease rather clearly when plotted as a function of the date of admission, and the parameters showed a moderate and significant correlation (n = 72, r = 0.42, p = 0.00020) (Figure 6).

Figure 4.

The age of the doctoral student at the thesis defence as a function of the date of the thesis defence.

Figure 5.

The age of the doctoral student at the thesis defence as a function of the date of admission.

Figure 6.

The time between the date of admission and the date of thesis defence (in days) as a function of the date of admission.

Finally, Figure 7 indicates a clear increase in the number of individuals explicitly referred to as supervisors in the acknowledgements section of the doctoral thesis. Note that before a certain point in time, i.e., before approximately 1990, leadership figures, such as the Head of Department and/or one or two senior collaborators or mentors, were often acknowledged and mentioned by name but not referred to as supervisors.

Figure 7.

Number of explicitly mentioned supervisors in the acknowledgments section of the doctoral thesis as a function of the date of the thesis defence. A linear regression trendline is added to visualise the increase.

4. Discussion

Political reforms, other implementations of new legislation, reorganisations or major bureaucratic changes in an organisation, brought about by a higher level in a hierarchical structure, must be assumed to have been introduced with a purpose, most likely accompanied by the intentions of improving some aspect of either a specific operation, for example, education, or the society or societal management in broader terms. At the same time, the end product or outcome is not always systematically or objectively evaluated, and the degree of perceived improvement among those who are most closely involved in the actual execution of the daily tasks, required to reach the goal, is typically varying. Anecdotally, statements like ’it was better in the old days’, ’quality and standards have deteriorated’, ’all these regulations and all the bureaucracy don’t make any difference’ and ’we did all right before, without all these rules’ are not at all uncommon.

It has been claimed that doctoral education is still struggling with its identity as an education [15,16], for example, with regard to the traditional role of forming future university scholars with research as their paid labour versus the task of providing generic and transferable skills needed to act as an independent researcher or product developer in the broader context of a knowledge-based society. Particularly in science, engineering and medicine, completion of a doctoral education programme has often mistakenly been viewed upon as the process of completing a suitable number of scientific papers, while working in a research environment, and then compiling them into a thesis. Historically, as pointed out in the introduction, such a perspective was common, or even the norm, before the doctoral thesis became part of a formalised education, leading to the doctoral degree, in 1969, but there is reason to believe that this mentality has lingered for a number of years after this reform, and remnants can still be perceived in some research environments.

Sonesson et al. [6] (pp. 177–178) give an associated or related description, implying a kind of mutual independence between the doctoral student and the supervisor, in the sense that, before 1988, there were no restrictions on the number of admissions to doctoral studies, but the department had, on the other hand, very few obligations towards the admitted doctoral students in terms of supplying resources or financial support. Furthermore, the supervisor had a very high degree of secured state funding and was thus less dependent on the scientific production of doctoral students, and the doctoral student, very often, worked more or less independently without high expectations of regular supervision. This mentality of ‘mutual independence’ might be part of the explanation for why, in the doctoral theses of the 1970s and 1980s, there was only one single case in which a supervisor was explicitly acknowledged (in spite of the fact that at least one was always formally appointed). A few leadership figures, such as the Head of Department and/or one or two senior collaborators or mentors, were almost always acknowledged, but not as a supervisor, but rather as a person who introduced the doctoral student to the subject area or to the scientific issue, or a person who took an interest in the doctoral student’s work. Obviously, this is not, in any way, meant to imply that supervision did not exist before 1990, but the dominating wording must still, to some extent, reflect the mindset of the doctoral education environment. Hence, something must have brought about a change in wording that explicitly acknowledged the role of the supervisor, around 1990, and, in light of the hypothesis of this study, it is interesting to reflect briefly on plausible connections with completed political reforms. As mentioned above, in 1988, a statutory requirement was introduced that limited the admission of doctoral students to those who could be offered acceptable terms. Hence, when the number of admitted doctoral students was reduced, the identity of the supervisor role may have become clearer, and the supervisor versus doctoral student relationship is likely to have become stronger and more visible, perhaps contributing to the changed wording in acknowledgements from 1990 and onwards.

The ’mutual independence’, discussed in the previous paragraph, brings us to a major change that has occurred in the academic research environment during the last five decades, particularly in science, engineering and medicine, namely the increased dependence on short-term (typically 3–5 years) external funding, only to be granted after a time-consuming application procedure and in competition with other researchers, typically on a national or even multinational level. In grant applications and in the conditions of approved financing, research is described in terms of pre-defined projects that fit the profile of the funding body, and this sets boundaries for the choice of research direction and might limit the principle of free research. In a worst-case scenario, this development may create a mindset in which research publications are viewed upon as a commodity that the principal investigator (PI) gets paid for by degree of impact or even by mere quantity. Although it is important to emphasise that doctoral education is not equivalent to or interchangeable with research as a skilled profession, it is still a fact that doctoral education includes a substantial component of research activities and, to a large extent, takes place in a research environment, often referred to as a research group or a laboratory. It is probably more common than not that a doctoral supervisor is also a PI (i.e., typically a research group leader or head of a research laboratory) within the university department in question. Hence, in light of the developments described above, one sometimes talks about the ’projectification’ of science [16,17], and the tensions that can occur in doctoral education due to the dual roles of a person who is acting, simultaneously, both as a supervisor and a PI can very well be of relevance to the findings of this study. In a study by Soneson et al., activity analysis was elegantly used to deconstruct such a doctoral education environment into competing activity systems, thereby exposing underlying power structures and sources of conflict within the environment [6].

In many ways, this increased dependence on external funding has changed the supervisor versus doctoral student relationship into a complex interdependence. The supervisor is dependent on the scientific production rate of the doctoral students in order to attract funding, while the doctoral students, in turn, need to balance their need for (and right to) a doctoral education of high quality against their vulnerable position of dependence in relation to the supervisor and their sense of loyalty to the research group, and an accompanying willingness to contribute to the financial survival of the supervisor’s research group (perhaps with a future academic career in mind). Interestingly, this brings us back to the issue of the number of explicitly mentioned supervisors, discussed above. If we assume that the increased dependence on external funding has influenced the supervisor versus doctoral student relationship, it is very interesting to note that the most rapid increase in the degree of external funding of research in Sweden occurred, roughly, during the period from 1982 to 1989, from slightly above 30% to between 45% and 50% in 1989 [18] (Figure 1, p. 3), and from 1990 the word supervisor has been almost consistently used in the acknowledgements of the thesis. After 1990, the degree of external funding of research has generally continued to increase but at a considerably slower rate.

The brief summary above illustrates that there are both historical and contemporary reasons why third-cycle education faces problems in adapting to the structure of a formal education with a set curriculum and strict time frames. Under such circumstances, it was reasonable to investigate the hypothesis of reform-induced changes by elucidating what actually, as a matter of fact, has happened over time in terms of measurable output parameters. Using a relatively small subject area at a single university department as an example, or case, is a limitation of the study, but it facilitates a closer examination of the scientific contents of individual theses, in contrast to employing national statistics that would normally treat all theses as equivalent pieces of outcome. The review of 452 compilation theses issued in Sweden in 2001 (i.e., soon after the cut-off date of the period of investigation in this study), conducted by the Swedish Research Council, reported an average of 5.1 papers per thesis [14] (Table 2, p. 9), which is very close to the corresponding value of 5.2 observed in the present material. This indicates that the subject area investigated here should be reasonably representative of the national situation. However, a comparative study, including data from other subject areas and/or other countries, would be a relevant topic to address in future studies.

Although there is no strict definition of what characterises a formal education, leading to a degree [19], it seems reasonable to require structure, equivalence and predictability in the process during which knowledge, skills, competencies and appropriate judgement are acquired. Compared with an autodidactic process, a formal education should be more efficient (and in many cases also more effective). Particularly after the implementation of the Bologna agreement, formal educations are, in addition, very often characterised by specified learning outcomes [20]. Predictability, equivalence and intended learning outcomes are, obviously, related to precision and accuracy in various indicators of outcome, in the sense that all students who complete a certain education are expected to show skills that are basically comparable, which is of relevance to, for example, prospective employers. Interestingly, the main finding of this study is a significantly reduced variability in the scope (in terms of the total number of papers, accepted papers and accepted papers as first author) in doctoral theses published after the 1998 reform, compared with the earlier period. This observation is clearly an indication of an increased degree of equivalence of education among different doctoral students. At the same time, the mean values of the number of papers in each category increased slightly, but no significant changes were observed. This would imply that the quality, in terms of scope and rate of publication, has not deteriorated. Although a compilation thesis has been the dominating mode of publication in Medical Radiation Physics in Sweden during the whole period of investigation, it can also be noted that the observed complete lack of monographs after 1977 is in agreement with previously observed trends that monographs, to a large extent, are being replaced by faster publication of smaller pieces of results in peer-reviewed journals [12,13].

Regarding predictability, in the broad sense of understanding what must be done to achieve the learning objectives and thereby being able to finish the education within the planned time, the results seem to indicate that there has been an improvement also in this respect. The time needed to complete the education showed a tendency to have decreased over time, i.e., the time between admission and thesis defence showed a moderate and significant negative correlation with the date of admission (r = 0.42, p = 0.0002). Similarly, the age at the thesis defence showed a weak but significant negative correlation with the date of admission (r = 0.33, p = 0.0045).

It is also relevant to briefly reflect upon the development after the Bologna Process-related reform of higher education in 2007. In reports from 2012 and 2011 [20,21,22], it was concluded that, according to a survey answered by supervisors, obvious challenges existed, at that time, related to both the assessment and the actual achievement of some of the new degree outcomes, particularly if they could not primarily be assessed by the doctoral thesis. In the present study, it should be noted that doctoral students admitted after approximately 2015 appeared to show a particularly coherent pattern of time between admission and thesis defence. (Note: One person, admitted in 2017, has not yet completed the doctoral education due to parental leave.) Notably, in 2015, the Faculty of Science introduced a function for independently monitoring the progress of the education for each individual doctoral student. A so-called ‘departmental representative’ is appointed, primarily to take responsibility for an annual follow-up of the ISP, including consultation with the doctoral student and the supervisors, and to ensure that both parties, i.e., the doctoral student and the educational provider, fulfil their respective commitments within the education, as outlined in the ISP. This enhanced monitoring of progress was accompanied by the requirement that, in the ISP, all planned learning activities are to be explicitly connected with one or more of the degree outcomes stated in the HEO.

It is, for a number of reasons, not entirely straightforward to compare the contents of doctoral theses over more than five decades. Research topics have changed, equipment and tools have developed, including a dramatic increase in computer-aided tasks, and the landscape of scientific publishing is undergoing a significant transformation [23], including many new journals, open-access options, digital internet-based distribution and alternative peer-review approaches [24,25]. One might argue that publication is easier today, but, on the other hand, the competition is becoming much stronger as several populous countries have entered the scientific arena and become more and more influential within the increasingly globalised research community. With that said, it should be remembered that the traditional process of authoring manuscripts and submitting them for a single-blind or double-blind peer review has remained common and reasonably unchanged over time [26,27], which is of relevance when, as in the present study, one attempts to compare results of completed educational elements over time. Comparing the quality of research among different theses is always a precarious task, whether it is to be done over time or between research groups, but the main concern in this report is not primarily the quality of research, but rather the quality of the education.

Another important concern is whether the observed trend of a more homogeneous output is indeed an altogether positive development. For formal education, there are, as pointed out above, very strong reasons to advocate clarity in expectations, predictability in demands and in time required for completion, as well as equivalence in outcome (assumed to be ensured by predetermined learning outcomes), both for the sake of the doctoral student and for the potential receivers (e.g., employers). Nevertheless, it should be emphasised that structure, predictability and strict time frames are not always the most favourable ingredients in an environment of free, creative and innovative research, and efficiency can also be an enforced consequence of the demands for a high production rate of publications, mentioned above, and meeting such demands would tend to favour various forms of risk minimisation in the doctoral education [28]. The improved efficiency, implied by the findings of the current study, is to a considerable degree associated with increased governance (by, for example, internal regulatory documents and state legislation), and the associated standardisation of doctoral programmes has been identified as one important tendency in European doctoral education [29]. This development may, undoubtedly, be at the cost of a reduction in academic freedom and in acquired scientific maturation and independence. Furthermore, one should remember that the governing structures themselves have changed significantly in character during the observed period, not least as a consequence of the financial challenges of the welfare state that became quite noticeable in the 1970s and 1980s [30]. Hartley discussed the effects of these changed societal and economic conditions on higher education in 1995 [31], and it is interesting to note that this date coincides, approximately, with the Swedish 1998 reform of doctoral education that constitutes the main splitting point of the current investigation. Hartley points out four so-called dimensions of the, at that time, ongoing rationalisation of society, i.e., efficiency, quantification/calculability, predictability and control [31]. Without going into detail, the economic necessity under such circumstances is to do more with less, and the prioritisation of expenditure must be made by the government. Hartley refers to a hybrid system in which the specification of the product is made by the central government, whilst the control of the process is apparently owned by the professionals [32]. In order to manage the inherent tensions of such a system, Hartley predicts the need for a complex guidance and assessment system, with guidance for students and assessment of the academics within the higher education institutes. Governmental systems of assessment and audit have certainly become a reality [33], and it is more than likely that the dimensions discussed by Hartley have, indeed, had an influence on the findings reported in this study.

It was not the main aim of this study to establish the causal relationships behind the observed results but rather to investigate the hypotheses of reform-induced change. The underlying mechanisms are complex and interrelated, but the current findings suggest, for example, that the individual study plan, introduced in 1998, has served multiple purposes in providing structure, clarifying expectations at an early stage and setting a realistic timetable. The personal financial security of the student, ensured by the admission being conditional on a doctoral studentship, should not be underestimated. A few doctoral students in this study, all admitted in the 1980s, had a very long time between admission and thesis defence, and the absence of realistic educational planning as well as lack of full-time provision for studies may have been contributing factors. Other aspects, such as the mandatory arrangement of training in research supervision for supervisors (from 2001) and the requirement of appointing more than one supervisor, of which, one is the main supervisor (from 2007), may also have been of relevance. Importantly, although bureaucracy and legislation have been a reality, it should be emphasised that control has, to a large extent, been applied in order to strengthen the doctoral student’s position and to support the doctoral student in the learning process.

5. Conclusions

Doctoral theses in Medical Radiation Physics at Lund University have, on average, maintained their scope in quantitative terms over more than five decades, but the scope of the doctoral theses has, during this period, become significantly more uniform after the major political reform in 1998. The time between admission and thesis defence is decreasing. Supervisors have received more explicit recognition over time and have increased markedly in number. It is concluded that doctoral education has become more efficient and predictable, and it is suggested that improvements are a result of the introduction of structured individual study plans, in which all planned learning activities are explicitly connected with one or more of the degree outcomes, as well as by secured personal financial support. Increased efficiency can also be problematised, for example, with regard to risk minimisation and to the degree of acquired independence and freedom in the choice of research questions.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study in accordance with the Swedish Ethical Review Act. No sensitive personal data, or data relating to criminal offences, were processed in this study. No information was obtained directly from an individual, but only from freely available published material and public records. Collected personal data were processed in anonymized form for research purposes, as data of public interest, in accordance with the European Union General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR). The project was registered in Lund University's personal data database ‘Personal Data Lund University (PULU)’.

Informed Consent Statement

Consent was waived due to the retrospective nature of the study and the use of public records data. Persons whose data were processed were informed through a public announcement, including statements clarifying the possibility to opt out of participation or to receive additional information.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the author upon reasonable request. These data were derived from resources available in the public domain.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

References

- Ruano-Borbalan, J.-C. Doctoral education from its medieval foundations to today's globalisation and standardisation. Eur. J. Educ. 2022, 57, 367–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindbeck, A.A. Forskarutbildning och Forskarkarriär; Swedish Government Official Reports: SOU 1966:67; Ministry of Education Stockholm: Stockholm, Sweden, 1966. [Google Scholar]

- Premfors, R. Governmental commissions in Sweden. Am. Behav. Sci. 1983, 26, 623–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elmgren, M.; Forsberg, E.; Lindberg-Sand, Å.; Sonesson, A. The Formation of Doctoral Education; Joint Faculties of Humanities and Theology, Lund University: Lund, Sweden, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Elzinga, A. Triangeldramat bakom forskningspolitiken. In Makten Över Forskningspolitiken: Särintressen, Nationell Styrning och Internationalisering; Agrell, W., Ed.; Lund University Press: Lund, Sweden, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Sonesson, A.; Stenson, L.; Edgren, G. Research and education form competing activity systems in externally funded doctoral education. Nord. J. Stud. Educ. Policy 2023, 9, 173–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gribbe, J. Förändring och Kontinuitet: Reformer Inom Högre Utbildning och Forskning 1940–2020; Universitetskanslersämbetets Publikationer: Stockholm, Sweden, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Scott, P. Going beyond Bologna: Issues and themes. In European Higher Education at the Crossroads; Curaj, A., Scott, P., Vlasceanu, L., Wilson, L., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2012; pp. 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Vasquez-Martinez, C.-R.; Giron, G.; De-La-Luz-Arellano, I.; Ayon-Bañuelos, A. The effects of educational reform. In Education in One World: Perspectives from Different Nations. BCES Conference Books; Popov, N., Wolhuter, C., Almeida, P., Hilton, G., Ogunleye, J., Chigisheva, O., Eds.; Bulgarian Comparative Education Society: Sofia, Bulgaria, 2013; Volume 11. [Google Scholar]

- Shrestha, U.; Williams, T.P.; Samarrai, S.; Geldermalsen, A.; Zaidi, A. What is the relationship between politics, education reforms, and learning? Evidence from a new database and nine case studies. In Background Paper for World Development Report 2018: Learning to Realize Education’s Promise; World Bank Publications: Washington, DC, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Cardoso, S.; Santos, S.; Diogo, S.; Soares, D.; Carvalho, T. The transformation of doctoral education: A systematic literature review. High. Educ. 2022, 84, 885–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niedomysl, T.; Prowse, M.; Lund Hansen, A. Doctoral dissertations in human geography from Swedish universities 1884–2015: Demographics, formats and productivity. J. Geogr. High. Educ. 2018, 42, 337–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kehm, B.M. From government to governance: New mechanisms of steering higher education. High. Educ. Forum 2010, 7, 21–34. [Google Scholar]

- Karlsson, S. Svenska Avhandlingars Kvalité och Struktur. Har den Ökade Volymen på Forskarutbildningen Påverkat Kvalitén på Svensk Forskning? En Bibliometrisk Analys; Vetenskapsrådet: Stockholm, Sweden, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Shin, J.C.; Postiglione, G.A.; Ho, K.C. Challenges for doctoral education in East Asia: A global and comparative perspective. Asia Pac. Educ. Rev. 2018, 19, 141–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanivna, M.V. Professionalization and projectification of the doctoral education in the world. Sci. Vector Balk. 2019, 3, 53–54. [Google Scholar]

- Ylijoki, O.-H. Projectification and conflicting temporalities in academic knowledge production. Theory Sci. 2016, 38, 7–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heyman, U. Är Externfinansieringsgraden för Stor? The Association of Swedish Higher Education Institutions; SUHF Report; SUHF: Stockholm, Sweden, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- La Belle, T.J. Formal, nonformal and informal education: A holistic perspective on lifelong learning. Int. Rev. Educ. 1982, 28, 159–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindberg-Sand, Å. The embedding of the European higher education curricular reform at the institutional level: Development of outcome-based and flexible curricula? In European Higher Education at the Crossroads; Curaj, A., Scott, P., Vlasceanu, L., Wilson, L., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2012; pp. 191–207. [Google Scholar]

- Lindberg-Sand, Å.; Sonesson, A. Learning outcomes in doctoral education—Achieved and assessed? In Proceedings of the European Conference on Educational Research (ECER), Berlin, Germany, 12–16 September 2011.

- Lindberg-Sand, Å.; Sonesson, A. How the Learning Outcomes of the Doctoral Degree Are Conceived of and Assessed in Some Research Disciplines at Lund University: A Report to the EQ11; Lund University: Lund, Sweden, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Chiriboga, L. The changing landscape of scientific publishing. J. Histotechnol. 2019, 42, 95–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Björk, B.-C.; Hedlund, T. Emerging new methods of peer review in scholarly journals. Learn. Publ. 2015, 28, 85–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horbach, S.P.J.M.; Halffman, W. The changing forms and expectations of peer review. Res. Integr. Peer Rev. 2018, 3, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jana, S. A history and development of peer-review process. Ann. Libr. Inf. Stud. 2019, 66, 152–162. [Google Scholar]

- Rampelotto, P.H. A Critical assessment of the peer review process in Life: From Submission to Final Decision. Life 2023, 13, 1603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neumann, R. Policy driving change in doctoral education: An Australian case study. In Changing Practices of Doctoral Education; Boud, D., Lee, A., Eds.; Routledge: Oxon, UK, 2009; pp. 211–224. [Google Scholar]

- Baschung, L. Identifying, characterising and assessing new practices in doctoral education. Eur. J. Educ. 2016, 51, 522–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deeming, C.; Johnston, R. Coming together in a rightward direction: Post-1980s changing attitudes to the British welfare state. Qual. Quant. 2018, 52, 395–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hartley, D. The ‘McDonaldization’ of higher education: Food for thought? Oxf. Rev. Educ. 1995, 21, 409–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neave, G.; van Vught, F.A. (Eds.) Prometheus Bound: The Changing Relationship Between Government and Higher Education in Western Europe; Pergamon Press: Oxford, UK, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Ers, A.; Tegler Jerselius, K. Peer review in public administration: The case of the Swedish higher education authority. In Peer Review in an Era of Evaluation; Forsberg, E., Geschwind, L., Levander, S., Wermke, W., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: Cham, Switzerland, 2022. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).