Online PBPD and Coaching for Teaching SRSD Argumentative Writing in Middle School Classrooms

Abstract

1. Professional Development and Instructional Coaching

2. Practice-Based Professional Development

3. Online PBPD and Instructional Coaching

4. Self-Regulated Strategy Development

5. Purpose and Research Questions

- Does PBPD and ongoing online coaching result in teachers delivering SRSD for argumentative writing with prescribed dosage and high fidelity and quality?

- Does SRSD instruction for argumentative writing from source texts for middle school students with high-incidence disabilities improve students’ writing skills?

- How do middle school students with high-incidence disabilities report their self-efficacy for writing argumentative essays after receiving SRSD instruction?

- Do teachers and students find the SRSD for argumentative writing instruction to have acceptable social validity?

6. Method

6.1. Participants and Setting

6.2. Online PBPD for SRSD

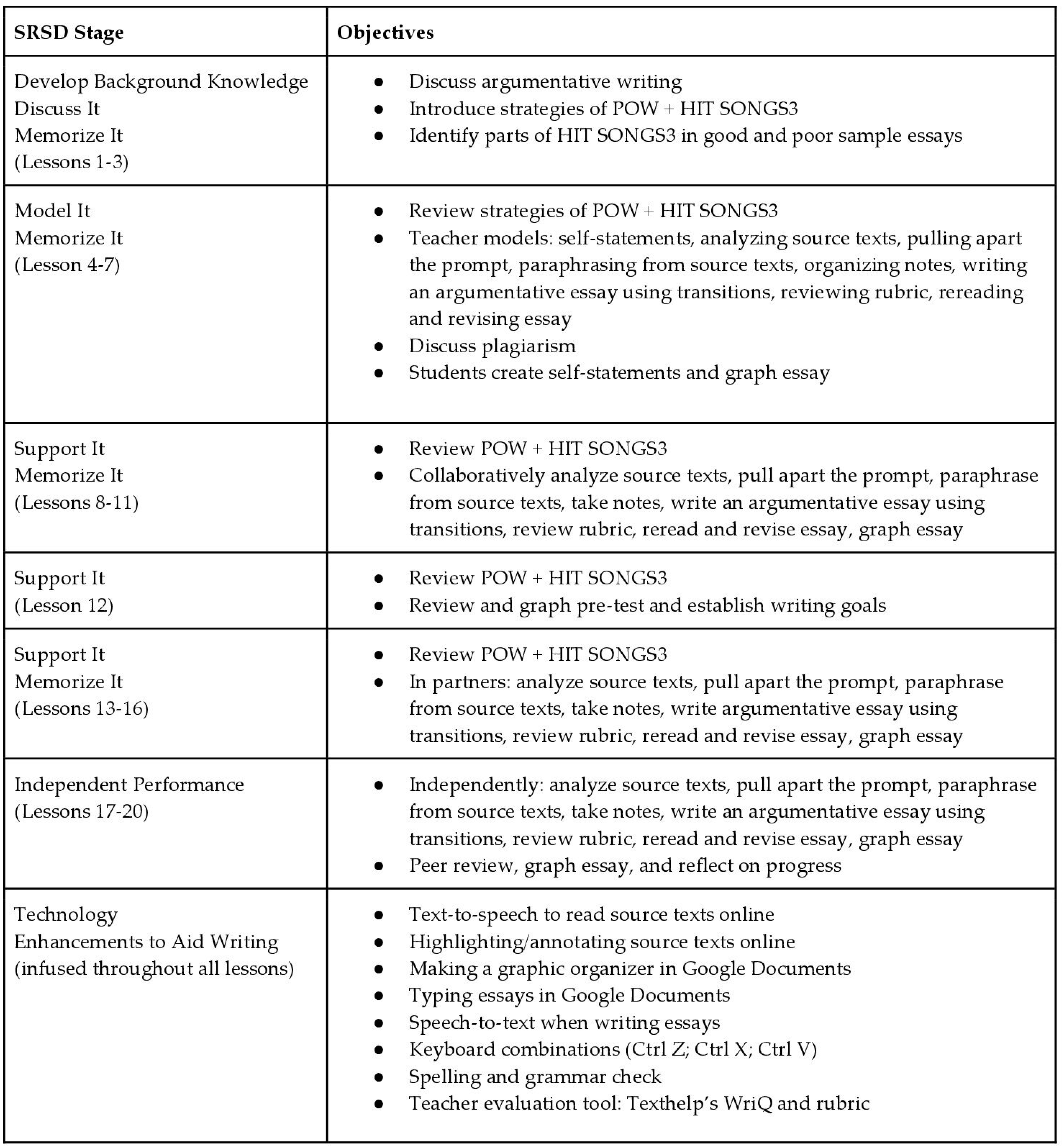

6.3. SRSD Instruction and Coaching

6.4. Teacher Measures

6.4.1. Dosage

6.4.2. Adherence

6.4.3. Quality

6.4.4. Current Writing Practices Survey

6.4.5. Teacher Social Validity Survey

6.5. Student Measures

6.5.1. Argumentative Essay Writing

6.5.2. Self-Efficacy for Writing

6.5.3. Student Social Validity

6.6. Design

7. Results

7.1. Teacher Implementation: Dosage, Fidelity, and Quality

7.2. Teacher Social Validity

7.3. Student Argumentative Essay Writing

7.3.1. Planning

7.3.2. Total Word Count

7.3.3. Quality

7.3.4. Argumentative Elements

7.3.5. Transitions

7.4. Student Self-Efficacy for Writing

7.5. Student Social Validity

8. Discussion

8.1. Teacher Implementation of SRSD Argumentative Writing Instruction

8.2. Enhancing Middle School Students’ Argumentative Writing Performance

8.3. Limitations and Future Research

8.4. Implications for Practice

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ray, A.B.; Graham, S.; Houston, J.D.; Harris, K.R. Teachers use of writing to support students’ learning in middle school: A national survey in the United States. Read. Writ. Interdiscip. J. 2016, 29, 1039–1068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ray, A.B.; Poch, A.L.; Datchuk, S.M. Secondary Educators’ Writing Practices for Students with Disabilities: Examining Distance Learning and In-Person Instruction. J. Spec. Educ. Technol. 2023, 38, 472–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ray, A.B.; Torres, C.; Cao, Y. Improving Informative Writing in Inclusive and Linguistically-Diverse Elementary Classes through Self-Regulated Strategy Development. Exceptionality 2023, 31, 319–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myers, J.; Scales, R.Q.; Grisham, D.L.; Wolsey, T.D.; Dismuke, S.; Smetana, L.; Yoder, K.K.; Ikpeze, C.; Ganske, K.; Martin, S. What About Writing? A National Exploratory Study of Writing Instruction in Teacher Preparation Programs. Lit. Res. Instr. 2016, 55, 309–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKeown, D.; Wijekumar, K.; Owens, J.; Harris, K.; Graham, S.; Lei, P.; FitzPatrick, E. Professional development for evidence-based SRSD writing instruction: Elevating fourth grade outcomes. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 2023, 73, 102152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, J.M.; Kovacs, P.E. The impact of standards-based reform on teachers: The case of ‘No Child Left Behind’. Teach. Teach. Theory Pract. 2011, 17, 201–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, D.N. “I’m not a good writer”: Supporting teachers’ writing identities in a university course. In Writer Identity and the Teaching and Learning of Writing; Routledge: London, UK, 2016; pp. 71–84. [Google Scholar]

- Nauman, A.D.; Stirling, T.; Borthwick, A. What Makes Writing Good? An Essential Question for Teachers. Read. Teach. 2011, 64, 318–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, S.; Capizzi, A.; Harris, K.R.; Hebert, M.; Morphy, P. Teaching writing to middle school students: A national survey. Read. Writ. 2014, 27, 1015–1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirsch, S.E.; Randall, K.N.; Common, E.A.; Lane, K.L. Results of Practice-Based Professional Development for Supporting Special Educators in Learning How to Design Functional Assessment-Based Interventions. Teach. Educ. Spec. Educ. 2020, 43, 281–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desimone, L.M. Improving Impact Studies of Teachers’ Professional Development: Toward Better Conceptualizations and Measures. Educ. Res. 2009, 38, 181–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ray, A.B.; FitzPatrick, E. Instructional Coaches in Elementary Settings: Writing the Wave to Success with Self-Regulated Strategy Development for the Informational Genre. Learn. Disabil. Res. Pract. 2024, 39, 37–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, A.A.; Ciullo, S.; Graham, S.; Sigafoos, L.L.; Guerra, S.; David, M.; Judd, L. Writing expository essays from social studies texts: A self-regulated strategy development study. Read. Writ. 2021, 34, 1623–1651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh, N.R.; Ginger, K.; Akhavan, N. Benefits of instructional coaching for teacher efficacy: A mixed methods study with PreK-6 teachers in California. Issues Educ. Res. 2020, 30, 1143–1161. Available online: https://www.iier.org.au/iier30/walsh.pdf (accessed on 22 May 2024).

- Kirkpatrick, L.; Searle, M.; Smyth, R.E.; Specht, J. A coaching partnership: Resource teachers and classroom teachers teaching collaboratively in regular classrooms. Br. J. Spec. Educ. 2020, 47, 24–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Billingsley, B.; Bettini, E. Special Education Teacher Attrition and Retention: A Review of the Literature. Rev. Educ. Res. 2019, 89, 697–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powell, C.G.; Bodur, Y. Teachers’ perceptions of an online professional development experience: Implications for a design and implementation framework. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2019, 77, 19–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Linden, S.; van der Meij, J.; McKenney, S. Teacher video coaching, from design features to student impacts: A systematic literature review. Rev. Educ. Res. 2022, 92, 114–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, K.R.; Camping, A.; McKeown, D. Practice-based professional development for scaling up writing interventions: Lessons learned and challenges remaining. In Conceptualizing, Designing, Implementing, and Evaluating Writing Interventions; DeSmedt, F., Bouwer, R., Limpo, T., Graham, S., Eds.; Brill: Leiden, Germany, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- McKeown, D.; Brindle, M.; Harris, K.R.; Sandmel, K.; Steinbrecher, T.D.; Graham, S.; Lane, K.L.; Oakes, W.P. Teachers’ Voices: Perceptions of Effective Professional Development and Classwide Implementation of Self-Regulated Strategy Development in Writing. Am. Educ. Res. J. 2019, 56, 753–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ball, D.; Cohen, D. Developing practice, developing practitioners: Toward a practice-based theory of professional education. In Teaching as the Learning Profession; Darling-Hammond, L., Sykes, G., Eds.; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1999; pp. 3–32. [Google Scholar]

- Knowles, M.S. The Modern Practice of Adult Education: From Pedagogy to Andragogy; ERIC: Cambridge, UK, 1980.

- Livingston, M.; Cummings-Clay, D. Advancing adult learning using andragogic instructional practices. Int. J. Multidiscip. Perspect. High. Educ. 2023, 8, 29–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shidler, L. The Impact of Time Spent Coaching for Teacher Efficacy on Student Achievement. Early Child. Educ. J. 2009, 36, 453–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darling-Hammond, L.; Hyler, M.E.; Gardner, M. Effective Teacher Professional Development; Learning Policy Institute: Palo Alto, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- McKeown, D.; Brindle, M.; Harris, K.R.; Graham, S.; Collins, A.A.; Brown, M. Illuminating growth and struggles using mixed methods: Practice-based professional development and coaching for differentiating SRSD instruction in writing. Read. Writ. Interdiscip. J. 2016, 29, 1105–1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suppo, J.L.; Mayton, M.R. Expanding Training Opportunities for Parents of Children with Autism. Rural. Spec. Educ. Q. 2014, 33, 19–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darling-Hammond, L.; Richardson, N. Research review/teacher learning: What matters. Educ. Leadersh. 2009, 66, 46–53. [Google Scholar]

- CAST. Universal Design for Learning Guidelines Version 2.2 [Graphic Organizer]; CAST: Wakefield, MA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Kara, M.; Erdogdu, F.; Kokoc, M.; Cagiltay, K. Challenges Faced by Adult Learners in Online Distance Education: A Literature Review. Open Prax. 2019, 11, 5–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ray, A.B.; Graham, S.; Liu, X. Effects of college entrance essay exam instruction for high school students with disabilities or at-risk for writing difficulties. Read. Writ. Interdiscip. J. 2019, 32, 1507–1529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ray, A.B.; Graham, S. A college entrance essay exam intervention for students with high-incidence disabilities and struggling writers. Learn. Disabil. Q. 2021, 44, 275–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ray, A.B.; Mason, T.E. Teaching middle school students with learning disabilities argumentative writing using SRSD with technology supports. J. Res. Spec. Educ. Needs, 2024; advance online publication. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, K.R.; Graham, S. Self-regulated strategy development: Theoretical bases, critical instructional elements, and future research. In Studies in Writing Series: Vol. 34. Design Principles for Teaching Effective Writing; Fidalgo, R., Harris, K.R., Braaksma, M., Eds.; Brill: Leinden, Germany, 2018; pp. 119–151. [Google Scholar]

- Graham, S.; Kim, Y.-S.; Cao, Y.; Lee, J.W.; Tate, T.; Collins, P.; Cho, M.; Moon, Y.; Chung, H.Q.; Olson, C.B. A meta-analysis of writing treatments for students in grades 6–12. J. Educ. Psychol. 2023, 115, 1004–1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Festas, I.; Oliveira, A.L.; Rebelo, J.A.; Damião, M.H.; Harris, K.; Graham, S. Professional development in Self-Regulated Strategy Development: Effects on the writing performance of eighth grade Portuguese students. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 2015, 40, 17–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geres-Smith, R.; Mercer, S.H.; Archambault, C.; Bartfai, J.M. A Preliminary Component Analysis of Self-Regulated Strategy Development for Persuasive Writing in Grades 5 to 7 in British Columbia. Can. J. Sch. Psychol. 2019, 34, 38–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mason, L.H.; Kubina, R.M.; Kostewicz, D.E.; Cramer, A.M.; Datchuk, S. Improving quick writing performance of middle-school struggling learners. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 2013, 38, 236–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palermo, C.; Thomson, M.M. Teacher implementation of Self-Regulated Strategy Development with an automated writing evaluation system: Effects on the argumentative writing performance of middle school students. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 2018, 54, 255–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroesch, A.M.; Peeples, K.N.; Pleasant, C.L.; Cuenca-Carlino, Y. Let’s Argue: Developing Argumentative Writing Skills for Students with Learning Disabilities. Read. Writ. Q. 2022, 38, 399–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NCS Pearson. Wechsler Individual Achievement Test, 4th ed.; Pearson: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Durlak, J.A.; DuPre, E.P. Implementation Matters: A Review of Research on the Influence of Implementation on Program Outcomes and the Factors Affecting Implementation. Am. J. Community Psychol. 2008, 41, 327–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Teacher | State | Grade Taught | Ethnicity | Gender | Education | Years Teaching | Teaching Role | Quality of Preparation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Teacher 1 | Kentucky | 6 | Caucasian | Female | Master’s Degree | 8 | General Education ELA | Very Good |

| Teacher 2 | Kentucky | 7 | Caucasian | Female | Master’s Degree | 13 | General Education ELA | Very Good |

| Teacher 3 | Washington | 7 | Caucasian | Female | Bachelor’s Degree | 14 | Special Education | Poor |

| Teacher 4 | Washington | 7 | Caucasian | Female | Master’s Degree | 30 | Special Education | Inadequate |

| Teacher 5 | New York | 8 | Caucasian | Female | Doctorate Degree | 23 | Special Education | Very Good |

| Measure | Pre-Test | Post-Test | g Post |

|---|---|---|---|

| Planning | 1.04 (1.72) | 3.33 (2.10) | 0.96 * |

| TWW | 185.20 (123.59) | 247.10 (156.20) | 0.32 * |

| Quality | 2.50 (1.53) | 2.98 (1.92) | 0.25 * |

| Elements | 7.60 (5.03) | 9.94 (6.80) | 0.31 * |

| Transitions | 2.00 (2.40) | 2.33 (2.50) | 0.11 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ray, A.B.; Mason, T.E.; Connor, K.E.; Williams, C.S. Online PBPD and Coaching for Teaching SRSD Argumentative Writing in Middle School Classrooms. Educ. Sci. 2024, 14, 603. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14060603

Ray AB, Mason TE, Connor KE, Williams CS. Online PBPD and Coaching for Teaching SRSD Argumentative Writing in Middle School Classrooms. Education Sciences. 2024; 14(6):603. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14060603

Chicago/Turabian StyleRay, Amber B., Tara E. Mason, Kate E. Connor, and Crystal S. Williams. 2024. "Online PBPD and Coaching for Teaching SRSD Argumentative Writing in Middle School Classrooms" Education Sciences 14, no. 6: 603. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14060603

APA StyleRay, A. B., Mason, T. E., Connor, K. E., & Williams, C. S. (2024). Online PBPD and Coaching for Teaching SRSD Argumentative Writing in Middle School Classrooms. Education Sciences, 14(6), 603. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14060603