Multi-Level Leadership Development Using Co-Constructed Spaces with Schools: A Ten-Year Journey

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Leadership: Individualized, Multi-Level, and Collective

1.2. Leadership as Process and Practice

2. Emergent Design and Methods

- Season one: Collaborative practices and inquiry (ELN, 2015–19);

- Season two: Adaptation and wayfinding (ELN, 2020–22; NLN, 2021, 22);

- Season three: Shifting patterns of practice (ELN, 2023, 24; NLN, 2023, 24).

The Sources

3. Findings: Three Seasons over Ten Years

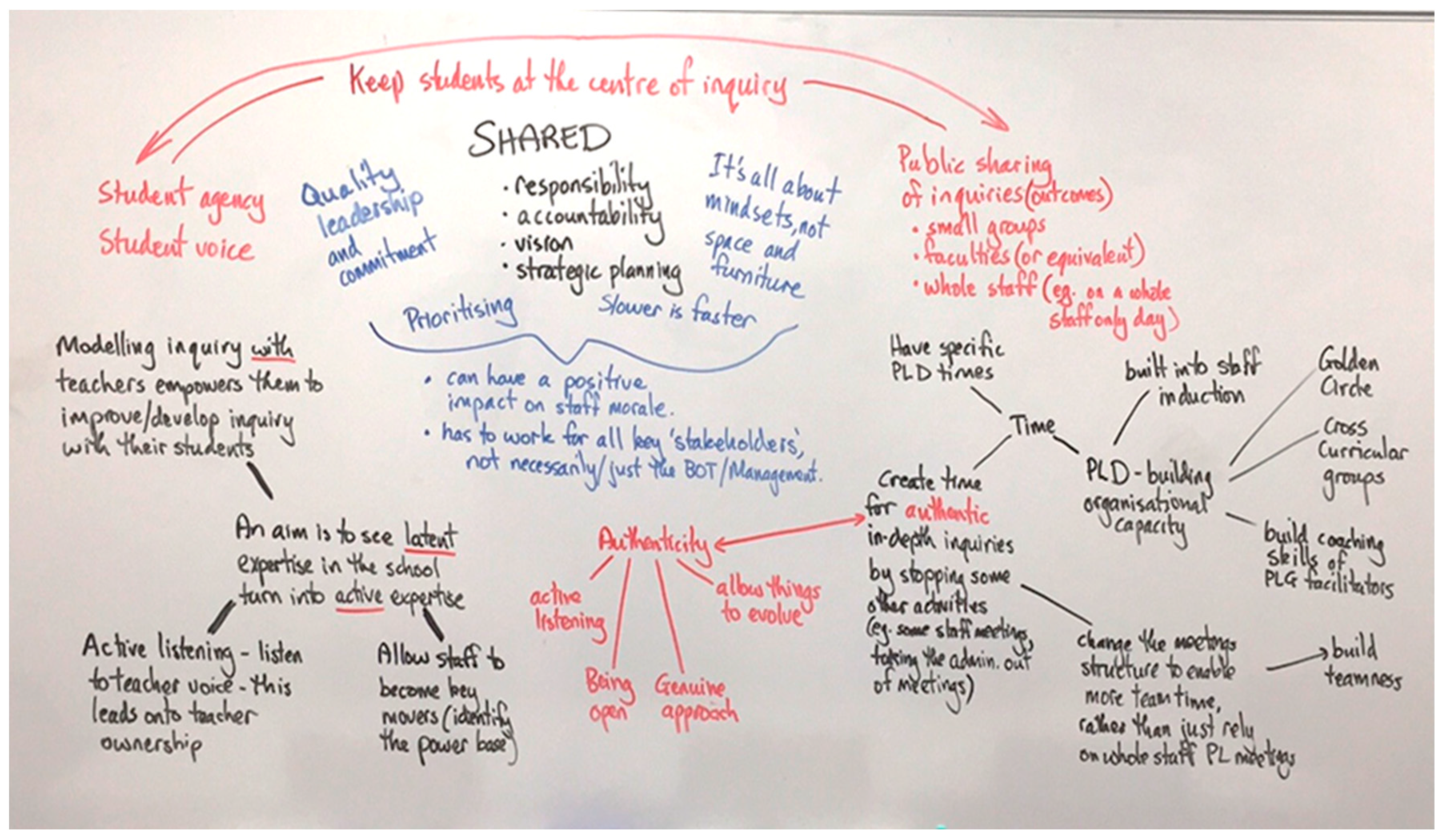

3.1. Season One: Collaborative Practices and Inquiry

3.1.1. A “Line in the Sand”

3.1.2. The Emergence of Leadership Inquiry and Workload Challenges

- Lack of time, workload, exhaustion;

- Assumptions, blinkered mindset;

- Fear of failure, fear of being aware, not ready for learning, self-doubt;

- Pride, arrogance, entitlement, stubbornness.

3.1.3. Supporting the Middle Space and Well-Being

- Term one—foci and planning established;

- Term two—sustaining and adapting;

- Term three—evidence and data;

- Term four—evaluation and reflection.

- “ELN has helped us with the idea that we could have our own model of inquiry” (School E, FG, 2019);

- “when you first started going to the ELN and having PD, it was originally first just sort of leadership team [sic], but then we brought in our middle leaders too and because they’re in the classroom and they can see the practice, then they will spread that to their teachers too” (School F, FG, 2019);

- “I think that the breakfast ELN meetings have provided us with time and discussion stimulus to have different kind of conversations than we would have in our normal meetings” (School F, FG, 2019);

- “And then ELN, it’s been really good for us to come back and discuss aspects from it that have made us think differently about what our teachers bring to our school and what they bring to groups” (School G, FG, 2019).

3.2. Season Two: Adaptation and Wayfinding

3.2.1. Adapting in Disruption

3.2.2. The Emergence of Wayfinding Leadership and Capacity Decrease

3.3. Season Three: Shifting Patterns of Practice

3.3.1. Refining the Focus: A Shift for the Facilitators

3.3.2. Going Deeper: A Shift for the Schools

- Trying to maintain too many change initiatives;

- Siloes;

- Problem framing;

- Hesitation related to engaging in challenging to have conversations;

- Staff capacity for engagement;

- Staff well-being;

- Relying on untested assumptions;

- Insufficient data and/or analysis such as student voice and student achievement data.

4. Discussion: Our Learnings over Ten Years

4.1. Connecting Workshop Practices with School-Site Practices

4.2. Embracing Leadership from Multiple Positions

4.3. Leadership Inquiry and Ongoing Knowledge Co-Construction

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Eacott, S. Beyond Leadership: A Relational Approach to Organizational Theory in Education; Springer: Singapore, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Meindl, J.R.; Ehrlich, S.B.; Dukerich, J.M. The romance of leadership. Adm. Sci. Q. 1985, 30, 78–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Reilly, D.; Reed, M. ‘Leaderism’: An evolution of managerialism in UK public service reform. Public Adm. 2010, 88, 960–978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Youngs, H. Variegated perspectives within distributed leadership: A mix(up) of ontologies and positions in construct development. In The Palgrave Handbook of Educational Leadership and Management Discourse; English, F.W., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, M.; Dibben, M. Leadership as relational process. Process Stud. 2015, 44, 24–47. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/44798050 (accessed on 13 September 2019).

- Wilkinson, J. Educational leadership as practice. In Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Education; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvesson, M.; Spicer, A. Critical perspectives on leadership. In The Oxford Handbook of Leadership and Organizations; Day, D.V., Ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2014; pp. 40–56. [Google Scholar]

- Gunter, H. An Intellectual History of School Leadership Practice and Research; Bloomsbury: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Gumus, S.; Bellibas, M.S.; Esen, M.; Gumus, E. A systematic review of studies on leadership models in educational research from 1980 to 2014. Educ. Manag. Adm. Leadersh. 2018, 46, 25–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Nobile, J.; Lipscombe, K.; Tindall-Ford, S.; Grice, C. Investigating the roles of middle leaders in New South Wales public schools: Factor analyses of the Middle Leadership Roles Questionnaire. Educ. Manag. Adm. Leadersh. 2024, 0, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipscombe, K.; Tindall-Ford, S.; Lamanna, J. School middle leadership: A systematic review. Educ. Manag. Adm. Leadersh. 2023, 51, 270–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Nobile, J. Neither senior, nor middle, but leading just the same: The case for first level leadership. Lead. Manag. 2023, 29, 9–20. [Google Scholar]

- Ospina, S.M.; Foldy, E.G.; Fairhurst, G.T.; Jackson, B. Collective dimensions of leadership: Connecting theory and method. Hum. Relat. 2020, 73, 441–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, M.; Huber, S.G. Mapping the international knowledge base of educational leadership, administration and management: A topographical perspective. Comp. A J. Comp. Int. Educ. 2019, 51, 4–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y. The panorama of the last decade’s theoretical groundings of Educational Leadership research: A concept co-occurrence network analysis. Educ. Adm. Q. 2018, 54, 327–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedrich, T.L.; Griffith, J.A.; Mumford, M.D. Collective leadership behaviors: Evaluating the leader, team network, and problem situation characteristics that influence their use. Leadersh. Q. 2016, 27, 312–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gronn, P. Hybrid configurations of leadership. In The Sage Handbook of Leadership; Bryman, A., Collinson, D., Grint, K., Jackson, B., Uhl-Bien, M., Eds.; Sage Publications: London, UK, 2011; pp. 437–454. [Google Scholar]

- Youngs, H. Distributed leadership. In Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Education; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Youngs, H.; Evans, L. Distributed leadership. In Understanding Educational Leadership: Critical Perspectives and Approaches; Courtney, S.J., Gunter, H.M., Niesche, R., Trujillo, T., Eds.; Bloomsbury: London, UK, 2021; pp. 203–219. [Google Scholar]

- Youngs, H. Moving beyond distributed leadership to distributed forms: A contextual and socio-cultural analysis of two New Zealand secondary schools. Lead. Manag. 2014, 20, 88–103. [Google Scholar]

- Crevani, L. Is there leadership in a fluid world? Exploring the ongoing production of direction in organizing. Leadership 2018, 14, 83–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langley, A.; Tsoukas, H. Introducing “Perspectives on Process Organization Studies”. In Process, Sensemaking, & Organizing; Hernes, T., Maitlis, S., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2010; pp. 1–26. [Google Scholar]

- Rescher, N. Process Metaphysics: An Introduction to Process Philosophy; State University of New York Press: New York, NY, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Tsoukas, H.; Chia, R. On organizational becoming: Rethinking organizational change. Organ. Sci. 2002, 13, 567–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLaren, T.A.S.; van der Hoorn, B.; Fein, E.C. Why Vilifying the Status Quo Can Derail a Change Effort: Kotter’s Contradiction, and Theory Adaptation. J. Change Manag. 2023, 23, 93–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, M. Leading changes: Why transformation explanations fail. Leadership 2016, 12, 449–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feldman, M.S.; Orlikowski, W.J. Theorizing practice and practicing theory. Organ. Sci. 2011, 22, 1240–1253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simpson, B. Where’s the agency in leadership-as-practice. In Leadership-as-Practice: Theory and Application; Raelin, J., Ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2016; pp. 159–177. [Google Scholar]

- Grace, M. Origins of leadership: The etymology of leadership. In Proceedings of the International Leadership Association Conference, Guadalajara, Mexico, 6–8 November 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Spiller, C.; Barclay-Kerr, H.; Panoho, J. Wayfinding Leadership: Ground-Breaking Wisdom for Developing Leaders; Huia: Wellington, New Zealand, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Sveiby, K.-E. Collective leadership with power symmetry: Lessons from Aboriginal prehistory. Leadership 2011, 7, 385–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kemmis, S.; Wilkinson, J.; Edwards-Groves, C.; Hardy, I.; Grootenboer, P.; Bristol, L. Changing Practices, Changing Education; Springer: Singapore, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Sergi, V. Who’s leading the way? Investigating the contributions of materiality to leadership-as-practice. In Leadership-as-Practice: Theory and Application; Raelin, J., Ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2016; pp. 110–131. [Google Scholar]

- Dibben, M.; Youngs, H. New Zealand cases of collaboration within and between schools: The coexistence of cohesion and regulation. In School-to-School Collaboration: Learning across International Contexts; Armstrong, P.W., Brown, C., Eds.; Emerald Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2022; pp. 11–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Education. The New Zealand Curriculum; Learning Media Ltd.: Wellington, New Zealand, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Youngs, H.; Stringer, P.; Ogram, M. The (re)emergence of collaboration: School leadership and collaborative inquiry in practice In Proceedings of the New Zealand Association for Research in Education Annual Conference: The Politics of Learning/Nōku Anō te Takapau Wharanui, Victoria University of Wellington. 2016. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/379447018_The_reemergence_of_collaboration_School_leadership_and_collaborative_inquiry_in_practice#fullTextFileContent (accessed on 1 April 2024).

- Senge, P.M. The Fifth Discipline: The Art and Practice of the Learning Organization (Revised and Updated); Random House: London, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Cardno, C. Managing Effective Relationships in Education; Sage Publications: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Wenger, E. Communities of Practice: Learning, Meaning, and Identity; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Timperley, H.; Kaser, L.; Halbert, J. A Framework for Transforming Learning in Schools: Innovation and the Spiral of Inquiry; Seminar Series 234; Centre for Strategic Education: Melbourne, Australia, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Kaser, L.; Halbert, J. Creating and sustaining inquiry spaces for teacher learning and system transformation. Eur. J. Educ. 2014, 49, 206–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hargreaves, A. Teacher collaboration: 30 years of research on its nature, forms, limitations and effects. Teach. Teach. 2019, 25, 603–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wylie, C.; McDowall, S.; Ferral, H.; Felgate, R.; Visser, H. Teaching Practices, School Practices, and Principal Leadership: The First National Picture 2017; NZCER: Wellington, New Zealand, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Coghlan, D.; Brannick, T. Doing Action Research in Your Own Organisation, 4th ed.; Sage: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Moore, R. Was Keeping Schools Closed for So Long in the Covid Pandemic the Right Call? Stuff 25 February 2024. Available online: https://www.stuff.co.nz/nz-news/350185471/was-keeping-schools-closed-so-long-covid-pandemic-right-call (accessed on 1 April 2024).

- Wardman, J.K. Recalibrating pandemic risk leadership: Thirteen crisis ready strategies for COVID-19. J. Risk Res. 2020, 23, 1092–1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giustiniano, L.; Cunha, M.P.e.; Simpson, A.V.; Rego, A.; Clegg, S. Resilient leadership as paradox work: Notes from COVID-19. Manag. Organ. Rev. 2020, 16, 971–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vercio, C.; Loo, L.K.; Green, M.; Kim, D.I.; Beck Dallaghan, G.L. Shifting focus from burnout and wellness toward individual and organizational resilience. Teach. Learn. Med. 2021, 33, 568–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Netolicky, D.M. School leadership during a pandemic: Navigating tensions. J. Prof. Cap. Community 2020, 5, 391–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Te Ihuwaka: Education Evaluation Centre. Learning in a COVID-19 World: The Impact of COVID-19 on Schools; Education Review Office: Wellington, New Zealand, 2021. Available online: https://ero.govt.nz/our-research/learning-in-a-covid-19-world-the-impact-of-covid-19-on-schools (accessed on 5 May 2021).

- Flack, C.B.; Walker, L.; Bickerstaff, A.; Earle, H.; Margetts, C. Educator Perspectives on the Impact of COVID-19 on Teaching and Learning in Australia and New Zealand; Pivot Professional Learning: Melbourne, Australia, 2020; Available online: https://inventorium.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/Pivot-Professional-Learning_State-of-Education-Whitepaper_April2020.pdf (accessed on 5 February 2021).

- Youngs, H.; Roberts, A.; Tian, M.; Woods, P.A. Disrupted leadership in education. In Handbook on Leadership in Education; Woods, P.A., Roberts, A., Tian, M., Youngs, H., Eds.; Edward Elgar: Cheltenham, UK, 2023; pp. 517–535. [Google Scholar]

- Heifetz, R.A.; Grashow, A.; Linsky, M. The Practice of Adaptive Leadership: Tools and Tactics for Changing Your Organization and the World; Harvard Business Press: Boston, MA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Le Fevre, D.; Timperley, H.; Twyford, K.; Ell, F. Leading Powerful Professional Learning: Responding to Complexity with Adaptive Expertise; Corwin: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds, M. Reflective practice: Origins and interpretations. Action Learn. Res. Pract. 2011, 8, 5–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Youngs, H. Global leadership and management in higher education: Innovations and best practices (Keynote). In Proceedings of the International SEAMEO-Retrac Conference: Global Leadership and Management in Higher Education: Innovations and Best Practices, Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam, 28–29 October 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Gear, R.C.; Sood, K. School middle leaders and change management: Do they need to be more on the “balcony” than the dance floor? Educ. Sci. 2021, 11, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katz, S.; Dack, L.A. Towards a culture of inquiry for data use in schools: Breaking down professional learning barriers through intentional interruption. Stud. Educ. Eval. 2014, 42, 35–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skerritt, C.; McNamara, G.; Quinn, I.; O’Hara, J.; Brown, M. Middle leaders as policy translators: Prime actors in the enactment of policy. J. Educ. Policy 2021, 38, 567–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woods, P.A.; Roberts, A. Collaborative School Leadership: A Critical Guide; Sage Publications: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Sims, S.; Fletcher-Wood, H. Identifying the characteristics of effective teacher professional development: A critical review. Sch. Eff. Sch. Improv. 2021, 32, 47–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilden, S.; Tikkamäki, K. Reflective practice as a fuel for organizational learning. Adm. Sci. 2013, 3, 76–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Argyris, C.; Schön, D.A. Theory in Practice: Increasing Professional Effectiveness; Jossey Bass Publishers: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Wiese, C.W.; Burke, C.S. Understanding team learning dynamics over time. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 1417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robinson, V. Reduce Change to Increase Improvement; Corwin Press: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

| Source | Season One | Season Two | Season Three |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-prepared workshop material | Workshop outlines Workshop slides | Workshop outlines Workshop slides | Workshop outlines Workshop slides |

| Emergent material generated by participants | Materials and syntheses | Materials and syntheses | Materials and syntheses |

| Advisory Panel notes | Meeting notes with school leaders | Meeting notes with school leaders | Meeting notes with school leaders |

| Research project—part one (2015, 2016) | Focus groups and survey to staff from participating schools | - | - |

| Research project—part two (2018, 2019) | Focus groups and survey to staff from participating schools | - | - |

| School Term | Term Strand (See Figure 1) | Action Research Component [44] |

|---|---|---|

| One | Foci and planning established by schools | Constructing and planning action |

| Two | Sustaining and adapting | Taking action |

| Three | Evidence and data | Taking action |

| Four | Evaluation and reflection | Evaluating action and constructing |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Youngs, H.; Ogram, M. Multi-Level Leadership Development Using Co-Constructed Spaces with Schools: A Ten-Year Journey. Educ. Sci. 2024, 14, 599. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14060599

Youngs H, Ogram M. Multi-Level Leadership Development Using Co-Constructed Spaces with Schools: A Ten-Year Journey. Education Sciences. 2024; 14(6):599. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14060599

Chicago/Turabian StyleYoungs, Howard, and Maggie Ogram. 2024. "Multi-Level Leadership Development Using Co-Constructed Spaces with Schools: A Ten-Year Journey" Education Sciences 14, no. 6: 599. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14060599

APA StyleYoungs, H., & Ogram, M. (2024). Multi-Level Leadership Development Using Co-Constructed Spaces with Schools: A Ten-Year Journey. Education Sciences, 14(6), 599. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14060599