Abstract

Cultural diffusion and a paradigm shift from a “skill-based” approach to an “action-oriented” approach in language pedagogy transform the functions of an educator in a foreign language classroom. A language instructor accepts an intermediatory role in learners’ interactions with the environment, using language as a primary mediation tool. Thus, by being involved in varied social contexts and activities, a language educator mediates learning, communication, and sociocultural environments. This study relies on a structural analysis to investigate the mediating role of a language educator. It suggests that pedagogic mediation should be viewed as a specific form of language educators’ activity and described through three dimensions: mediating learning, mediating communication, and mediating sociocultural space. In the teaching and learning context, these dimensions manifest themselves as skills to adapt to the instructional and linguistic complexity of texts, manage interaction, facilitate communication in sensitive situations, etc. Drawing upon a phenomenological research design and qualitative methods, the study develops illustrative descriptors that can be used in a foreign language classroom to assess the patterns of social, instructional, and communicative behavior of educators. The developed descriptors allowed for exploring the self-perceptions of pre-service language teachers towards their abilities for pedagogic mediation in a foreign language classroom. The results of the study identified the learning gaps among novice language teachers that can be further addressed as learning objectives while designing a curriculum for professional training in language education.

1. Introduction

An educator’s competence to effectively communicate a message is essential for productive interaction and learning. This ability of educators ensures the translation of sociocultural values and norms accepted in a specific community, affects the psychological comfort of learners, and predetermines the effectiveness of delivered instruction [1,2]. Being involved in creating psychological, sociocultural, and cognitive comfort, an educator accepts the role of a mediator, guiding and assisting learners in their personal growth. The primary mediation tool used by educators is language. Language as a mediation tool allows educators to facilitate access to knowledge, involve learners in thinking, encourage collaboration, resolve conflicts and educational difficulties, translate sociocultural values and norms, and ensure the acquisition of language and communication patterns in a natural and comfortable setting. At this point, an educator has to possess a set of skills to mediate communication, learning, and social environments. Mediation for learning, communication, and social practices has been researched in linguistic, pedagogic, and social studies; however, these types of mediation have not been considered as the dimensions of “pedagogic mediation”—a category that describes social, communicative, and instructional aspects of an educator’s activity. Meanwhile, according to Stathopoulou, mediation can serve various functions in the classroom setting. For instance, it can have a beneficial effect on strengthening relationships between students and facilitating the learning process; but the research in this area of interest is nearly nonexistent [3]. Thus, this study considers pedagogic mediation as a specific type of professional activity in the realm of foreign language education that enables instructors to act as an intermediary for learning, communication, and social environment using the foreign language as a tool.

The aim of this study is to conceptualize the dimensions of pedagogic mediation and identify their illustrative descriptors from a communicative perspective. This will allow for the design of instructional materials and procedures for professional assessment within language teacher training programs conducted for non-native speakers at universities. There are several research questions:

Q1: What are the dimensions of pedagogic mediation in a foreign language classroom?

Q2: What illustrative descriptors can depict the aspects of pedagogic mediation in a foreign language classroom?

Q3: How well can novice language teachers, who are non-native speakers, mediate for learning, communication, and social environments?

The term and concept of pedagogic mediation have been brought into focus in several studies, but no real definition or description of its practicality has been given so far. In this study, we attempt to fill in this gap by identifying the theoretical underpinnings of its core dimensions and bringing together the key illustrative descriptors that could be employed for the design of courses in instructional communication that meet the objectives of modern curriculum for language educators.

1.1. Interdisciplinary Approach to Mediation

Mediation as a concept is widely used in social studies, namely in sociology, psychology, pedagogy, and linguistics. From a sociopsychological perspective, mediation is a strategy used to resolve conflict in the workplace or private life in a nonjudicial way [4,5]. In this case, mediation is perceived as a process in which a third party (mediator) facilitates communication among disputants, including decision-making, problem-solving, and negotiation, to reach a mutually acceptable agreement. Mediation as a conflict resolution strategy stipulates the accomplishment of specific steps and the creation of specific conditions for parties to resolve a dispute. The mediator’s role is to help the parties better understand each other’s concerns and interests in order to direct them toward a particular settlement. Within an educational context, social mediation refers to the resolution of conflicts in a learning environment and the creation of a “culture of mediation” that ensures social justice, recognition of individual rights, and shared responsibility [6].

In linguistic research, mediation is aligned with the abilities of an individual to interpret and transfer meanings from a source language into a target language [7]. However, in modern research, linguistic mediation has expanded beyond the frame of translation. It refers to managing meanings and communication flow and interpreting cultural cues and peculiarities [8,9]. From this stance, language is considered not just as a system of codes but as a medium of communication that allows for meaning-making and meaning-conveying, cultural interpretation, and social embodiment.

A linguistic mediator is an individual who possesses the ability not only to verbally translate from one language to another but also to facilitate communication between one person or a group of people and provide additional cultural support. Linguistic mediation is gaining attention in societies with a diverse cultural landscape [10]. It occurred in response to the need to integrate newcomers into host cultures [11,12]. As a result, in European and North American countries, linguistic mediators are viewed as specialists who render assistance in communication to people with varied cultural and linguistic backgrounds and needs.

In the field of pedagogy, mediation is grounded on the theories of social constructivism and viewed as a process of facilitating learning and communication in varied educational contexts [13,14]. Social mediation for schools and tertiary institutions represents another strand of research that focuses on conflict resolution and conflict management in homogeneous and multicultural educational contexts, as well as on designing tutoring systems for inclusive environments [11,15].

In the context of foreign language teaching, the concept of mediation is relatively new; however, it is considered the main drive of a paradigm shift in present language pedagogy [16,17]. The introduction of this concept into language education indicates the transition to an “action-oriented” approach in language pedagogy that emphasizes the use of language for communicative and social purposes. Besides that, the introduction of mediation into a language classroom stipulates the design of activities that ensure the integration of two or more of the communication modes (reception, production, and interaction), which in turn provides learners with extensive language practice. The main source of theoretical and practical implications is the Common European Framework of Reference Companion Volume with new descriptors (CEFR-CV), which presents the most recent view on the nature of mediation as a communicative phenomenon in a language classroom [16].

1.2. The Concept of Mediation in Language Pedagogy

According to CEFR-CV, mediation is one of the four modes of communication (reception, production, interaction, and mediation). Mediation occurs when “a learner or user acts as a social agent who creates bridges and helps to construct or convey meaning, sometimes within the same language, sometimes across modalities” [16] (p. 90). It addresses the actions of those individuals who help others fill the communication gap that occurred as a result of language, social, or cultural barriers. The most obvious example of a communication gap is when people experience difficulties in interaction because they do not know each other’s language and require a third language or a translator. This type of mediation is cross-linguistic and is considered a specific form of both daily and professional activity in multicultural contexts. However, communication gaps may also occur as a result of language varieties in the same language (intralinguistic mediation) [18]. Different language dialects, differences in accents, or register variations (formal or informal) can exemplify this type of mediation. Besides that, mediation comes to the forefront when communication gaps are caused by social or cultural differences or communication breakdowns derived from a disagreement [12]. In addition, mediation also occurs between the skills needed for processing the language input and output. For instance, in a lecture, a learner might listen to a professor speak, take notes, and read them later, for instance, out loud [18]. In this situation, the same content is being transferred across four skills, namely, listening, writing, reading, and speaking in case the content of the lecture is orally reproduced later on. Therefore, mediation appears to be a multifaceted communicative phenomenon that requires individuals to have well-developed emotional intelligence, communicative abilities in one or several languages, and metacognitive abilities that allow for planning, monitoring, and managing the communication flow in mediation activities.

The CEFR-CV describes the concept of mediation through mediation activities and mediation strategies. Mediation activities manifest themselves in “mediating text”, “mediating concepts”, and “mediating communication”, and mediation strategies include “strategies to explain a new concept” and “strategies to simplify a text” [16]. The newly introduced descriptor scheme for mediation activities and strategies represents an instructional shift from the traditional set of reception and production skills dominating in teaching foreign languages to developing a unity of four interrelated communicative modes (reception, production, interaction, and mediation) that underlie successful communication in multicultural settings. The focus is placed on its social role, with the language being used to create the space and conditions for learning, collaboration, constructing new meanings, encouraging others, and passing on new information in appropriate forms and in different contexts. These contexts may vary from social, cultural, and linguistic to professional or pedagogic.

1.3. Pedagogic Mediation and Its Dimensions

North and Piccardo-introduce four types of mediation: linguistic mediation, cultural mediation, social mediation, and pedagogic mediation [19].

Linguistic mediation comprises interlinguistic and intralinguistic dimensions. Within an interlinguistic domain, individuals may need to translate and interpret from one language into another, more formally or less formally, or transform one kind of written or oral text into another, considering or varying its genre and stylistic peculiarities. The intralinguistic dimension may manifest itself in the target language or in a source language (including a mother tongue) when an individual needs to summarize the information or adapt the language. Another form of linguistic mediation is the flexible use of different languages, for instance, in multilingual classrooms. This would require learners to explain, summarize, clarify, or expand a text from one language into another, and educators to manage collaborative interaction or narrate a text flexibly in different languages.

A transition from one language to another naturally involves the transition from one culture to another. Therefore, cultural mediation evolves as an ability to consider cultural peculiarities and explicitly employ them in order to adapt the meaning and comfort participants in delicate situations of intercultural communication. Cultural mediation is tightly connected to the notion of cultural awareness, which embraces the knowledge of idiolects, sociolects, and cultural norms [10,20]. It also leads to broadening the scope of cultural mediation in order to consider the social aspects of mediation as a communicative practice.

Social mediation complies with the idea of assisting individuals in communication breakdowns that occur as a result of linguistic, cultural, and social misunderstandings [21]. It refers to managing situations of tension and assimilating newcomers to the cultural and linguistic contexts.

According to North and Piccardo, pedagogic mediation derives from the assumption that “successful teaching is a form of mediation” [19] (p. 11). Educators try to mediate knowledge and learners’ experiences, as well as establish relationships and rapport, organize work, and resolve conflicts. Therefore, North and Piccardo-suggest differentiating between (1) “cognitive mediation: scaffolded” aimed at “facilitating access to knowledge and encouraging other people to develop their thinking”; (2) “cognitive mediation: collaborative” that stipulates “collaboratively co-constructing meaning as a member of a group in a school, seminar, or workshop setting”; and (3) “relational mediation” that ensures “creating the conditions for the above by creating, organizing, and controlling space for creativity” [19] (p. 11). The CEFR includes descriptive scales related to mediating concepts and mediating communication, emphasizing that “mediating concepts” is “a fundamental aspect of parenting, mentoring, teaching, and training, but also of collaborative learning and work”; “mediating communication” skills “are relevant to diplomacy, negotiation, pedagogy, and dispute resolution” [16] (p. 91). In other words, this document introduces the social context, namely pedagogical, where mediation comes first as a communicative practice; however, it does not describe specific teacher-centered activities, strategies, or skills that are commonly employed by educators. In addition, the suggested terms for “cognitive” and “relational” mediation do not fully explicate the difference between mediation activities for learning and communication, nor do they help to identify varied educational contexts in which language educators get involved as social agents. Therefore, we suggest distinguishing between “mediating learning”, “mediating communication”, and “mediating sociocultural space”.

Mediating learning. From a pedagogical perspective, mediation is viewed as a process that promotes learning as a result of the learner’s interactions with the environment [22,23]. This understanding primarily derives from Vigotsky’s and Feuerstein’s theories that consider mediation an intermediatory process that enhances learners’ cognitive development [22,23,24,25,26,27]. Vygotsky suggested that our contact with the world is mediated by signs or psychological tools, meaning that higher mental functions and processes had to be grounded in the notion of mediation [22,27]. Cognitive development always comes from the outer (social) world towards the internal (mental) world, where the relationship between the mind and environment is not immediate but mediated. From a psycholinguistic perspective, the cognitive development of an individual is mediated by language usage (and speech as a cognitive function), which, in turn, results in the emergence of a thought taking the form of a speech utterance. Mediation suggests the extensive use of language. Regarding the educational context, Bruner, as cited by Presseisen et al., stated that “it is not the language per se that makes the difference; rather, it seems to be the use of language as an instrument of thinking that matters” [25] (p. 5). In other words, language use and human interaction in an educational context might be viewed as mediation that encourages the development of cognitive processes and enables the appropriation of cultural and social norms.

The concept of mediation enables us to bridge the gap between the individual and the social dimensions and to consider individual cognitive processes as completely embedded in (and determined and structured by) a social activity. In an educational context, mediation takes place through people (mediators–instructors), specially designed symbolic tools, or learning activities, which, according to Vygotsky, should be designed in the “zone of proximal development” (ZPD) to allow for learners’ mediated discovery [22,24,27]. Considering the ambiguity of forms and functions of mediation, it might be reasonable to differentiate between the mediation activities, its modes, and tools for educational contexts:

Mediation modes: human interaction; technology-assisted interaction; visual communication (use of symbolic, metaphoric, or iconic signs that are culturally and contextually specific with the aim of facilitating and enhancing the learning process);

Mediation tools: objects of nature or environment and cultural-symbolic systems that support the mediation process (e.g., instructional materials, language, and technologies);

Mediation activity: an instance of the mediation process that explicates the social, cognitive, and communication functions of mediation (monitoring, explaining, facilitating, collaborating, interpreting, etc.).

The theory of mediated learning experience (MLE) developed by Feuerstein places human interaction (mediator) between a learner and the environment at the forefront, considering it the basis of children’s cognitive development [23,28]. It is assumed that an individual’s learning potential can be improved by mediation despite any cognitive or social challenges that occurred in response to insufficient social exposure (deprivation of indirect learning experiences) [25]. Mediation allows learners to build and modify their capacities through structured learning. As a result, they acquire new skills, behavior patterns, awareness, and a set of strategies that can then potentially be generalized to new experiences and stimuli.

Mediating learning stipulates the facilitation of knowledge and skill acquisition and involves specific manipulations with objects or language. From an instructional perspective, this could refer to adapting the complexity of designed materials, grading the language, or designing a system of specific symbols or codes.

Mediating communication. The ability of educators to ensure effective interaction in a classroom is explored within the field of instructional communication [29,30]. As a theoretical field, it describes the principles, rules, and maxims of effective communication within an educational context. Instructional communication is embedded in communication theories related to oratory and discourse (communication education) that focus on (1) oral communication skills—instructional strategies that communication instructors use to facilitate the acquisition of communicative competence by learners; (2) communication skills and competencies that are employed by all educators in the educational process; and (3) communication development—the optimal developmental sequence by which learners acquire communicative competence. The fundamentals of instructional communication are fueled by theories describing communication as a sociocultural and semiotic activity, which allows for a systemic discourse analysis of communicative behavior and speech patterns. These theoretical underpinnings underlie research frameworks aimed at analyzing instructional communication from discursive and rhetorical perspectives.

Within the frame of rhetorical analysis, the vast majority of studies focus on the specific communication strategies and techniques that underlie the teacher’s “clarity, immediacy, credibility” framework in traditional and digital educational environments [31]. The teacher’s clarity is four-dimensional, embracing the clarity of the organization of instructional material, the clarity of explanation, the clarity of guided practice, the clarity of learners’ assessment, and language clarity; the latter constitutes a specific topic of discussion in language pedagogy. The teacher’s (instructor’s) immediacy is approached as verbal and nonverbal behaviors that lessen the real or perceived physical and psychological distance between educators and learners (smiling, nodding, making eye contact, etc.). The teacher’s credibility refers to learners’ beliefs and assumptions about the professionalism of their educator; the teacher has to be believable, convincing, and capable of persuading learners that they can achieve the desired results. Although this approach is employed to design training materials for public presentations for teachers, “rhetoric for educators” is still not a common place in a teacher-training curriculum.

From the perspective of discourse analysis, instructional communication is researched to identify specific discursive patterns employed by educators that bring learners to the desired outcomes [32,33,34]. It is based on the assumption that a thoughtful and structured “teacher–student talk” can enrich the classroom space, making it more dynamic and engaging. The theoretical and practical analysis of instructional communication is set around the concept of “interaction”, which is considered a reciprocal and meaningful process of information exchange for knowledge co-construction. Within this framework, it is possible to identify specific elicitation and scaffolding techniques, models of dialogic communication, questioning, error correction, feedback, and repair strategies that contribute to learners’ progression.

Mediating communication refers to the strategies and techniques used by educators to present a cognitive stimulus (conceptual talk), facilitate or monitor classroom discussions, and establish rapport and credibility.

Mediating sociocultural space. According to Dendrinos, mediation is a form of social practice, “purposeful social practice, aiming at the interpretation of (social) meanings which are then to be communicated/relayed to others when they do not understand a text or a speaker fully or partially” [35] (p. 12). From this standpoint, mediation is considered a communicative tool that helps individuals interpret communicative purposes and convey social meanings. The inability to understand the text often leads to communication breakdowns that have to be handled by people or mediators in the most appropriate manner. Thus, a mediator in communication performs several roles that are socially, culturally, and contextually bound. Dendrinos states that a mediator could be considered: (1) “a social actor who monitors the process of interaction and acts when some type of intervention is required in order to help the communicative process and sometimes to influence the outcome”; (2) “a facilitator in social events during which two or more parties interacting are experiencing a communication breakdown or when there is a communication gap between them”; and (3) “a meaning negotiator operating as a meaning-making agent, especially when s/he intervenes in situations that require reconciliation, settlement, or compromise of meanings” [35] (p. 11). In this regard, social mediation would require an educator to facilitate a conflictual situation and work collaboratively towards the settlement of a disagreement.

In teaching practice, educators encounter situations in which they have to act not only as conflict mediators but also as culture mediators and mediators for technology-enhanced environments [36]. Cultural mediation in the foreign language classroom refers to building learners’ cultural awareness and fostering learners’ intercultural competence, especially while teaching multicultural classes [10]. The digitalization of language education has resulted in an extensive use of technologies in a foreign language classroom [37]. According to the theory of technology-mediated learning, digital technologies can perform an intermediary role (mediation) for participants striving to achieve desired results. In technology-mediated learning, the role of an educator is to help optimize learning experiences and outcomes through a thoughtful, purposeful, and structured use of learning technologies in a digital environment.

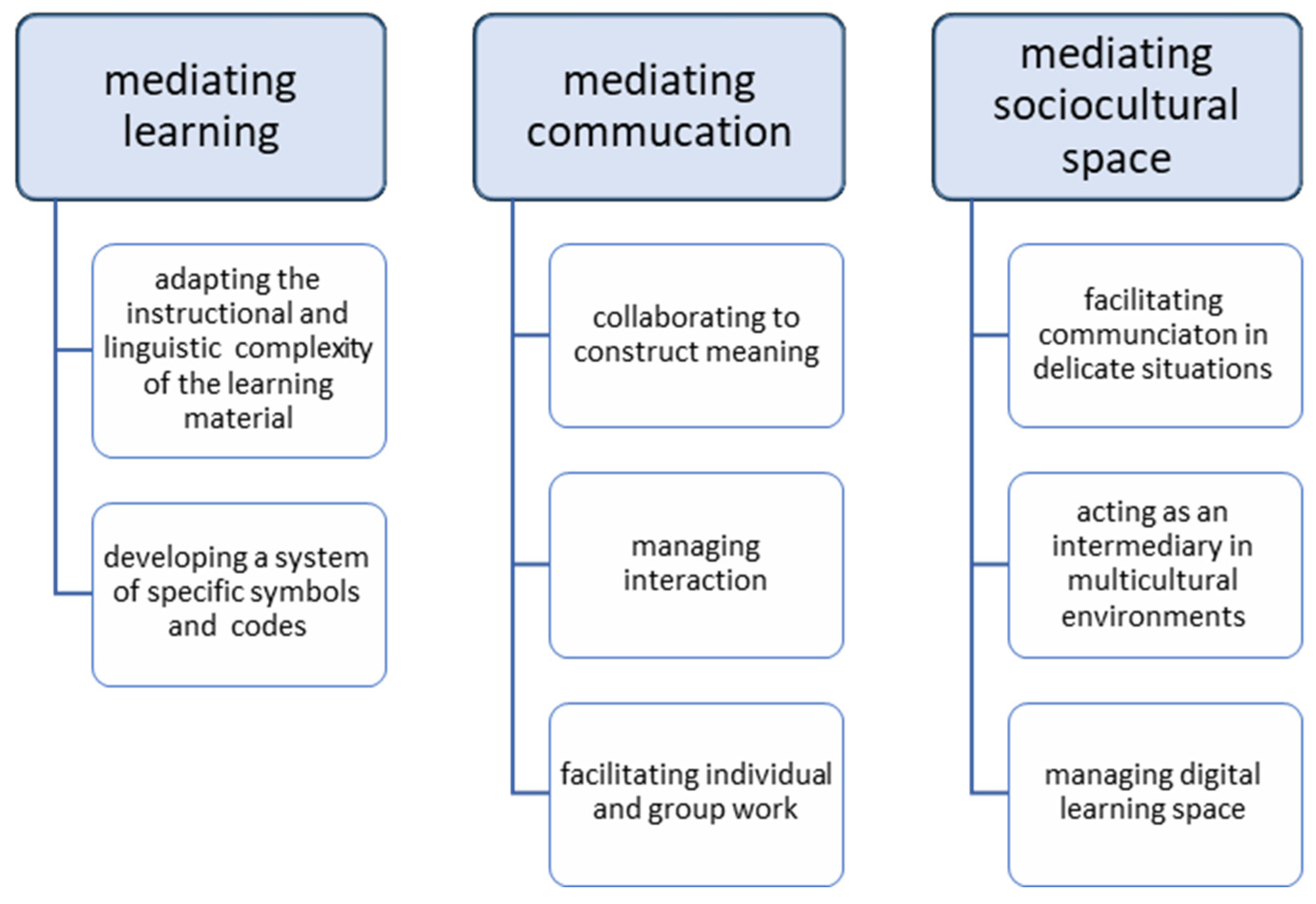

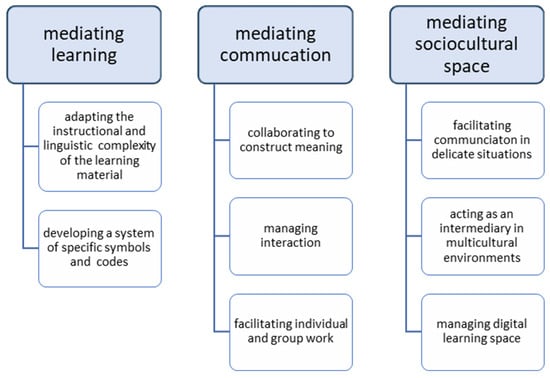

Figure 1 presents an overview of pedagogic mediation that embraces such dimensions as “mediating learning”, “mediating communication”, and “mediating sociocultural space” and related mediation activities.

Figure 1.

The dimensions of pedagogic mediation.

The theoretical construct of pedagogic mediation needs validation in terms of its practicality and applicability to the design of professional training programs for language educators. It is our belief that pedagogic mediation should be integrated into the modern curriculum for language teacher education, as this concept bridges the gap between the instructional and interactional competencies of a language teacher, constituting the core of their professional activity.

2. Materials and Methods

The study draws upon a phenomenological research design, which is qualitative in nature, and seeks to investigate experiences and assumptions from the perspective of the participants. This research design helps to look into the “lived experiences” of the individuals and aims to examine the reasons and outcomes of demonstrated behavior from their perspective [38]. This study considers pedagogic mediation as a communicative phenomenon that requires description and explanation within its context of occurrence. This qualitative approach seeks to uncover the instances of instructional and communicative behavior that together represent “pedagogic mediation in practice” and identify, based on the self-perceptions of novice teachers, how well they can mediate for learning, communication, and social environments.

To develop the proper description of pedagogic mediation and identify the ways its dimensions are perceived by novice teachers, the study included several stages: (1) gathering theoretical perspectives about the phenomenon under study and developing a draft of its illustrative descriptors (intuitive stage); (2) studying the phenomenon within its context of occurrence and verifying its dimensions (qualitative stage); (3) identifying the self-perceptions (self-assessments) of participants (master students) about the phenomenon under study. At these stages, the study employs such methods as a focus group, non-participatory observation, and survey (self-assessment) for data collection, analysis, and interpretation.

A focus group as a method of research aims at collecting qualitative data and getting more in-depth information on specific phenomena under consideration. It involves the preparation of a focus group guide that contains a series of questions to be discussed during the meetings. The method of non-participant observation enables researchers to gather the data by observing participants in natural environments without directly interacting with them. The survey was conducted among 1-year masters’ students in the form of a self-assessment to gather self-perceptions of masters’ students regarding their abilities to mediate for learning, communication, and social environments.

The research is justified by the need for systematic curriculum updating within a university context in order to meet the current objectives of professional language teacher training and is informed by national educational standards and several official reports issued by the European Council [19,39].

2.1. Context

The development of goals and objectives for curriculum draws on national educational standards, the specifics of an educational program, and the individual needs of learners. Based on the prior practical experience of training in-service language teachers (master’s students) and observations of their professional behavior during the internship, it became evident that the majority of novice language teachers experienced difficulties in explaining concepts, managing learners’ interactions, giving instructions, and resolving conflicting situations that occurred in a classroom. These skills were thought to relate to pedagogic mediation, and therefore, it was hypothesized that they should be included as learning objectives in the existing curriculum. However, in order to incorporate pedagogic mediation skills as learning objectives, it was necessary to develop a sound descriptive scale that could be further used for the design of instructional materials and assessment procedures for learning. Therefore, to validate the hypothesis, it became necessary: (1) to develop illustrative descriptors for pedagogic mediation and (2) to use these illustrative descriptors to identify the learning gaps among novice language teachers (masters’ students) based on their self-evaluation.

2.2. Participants

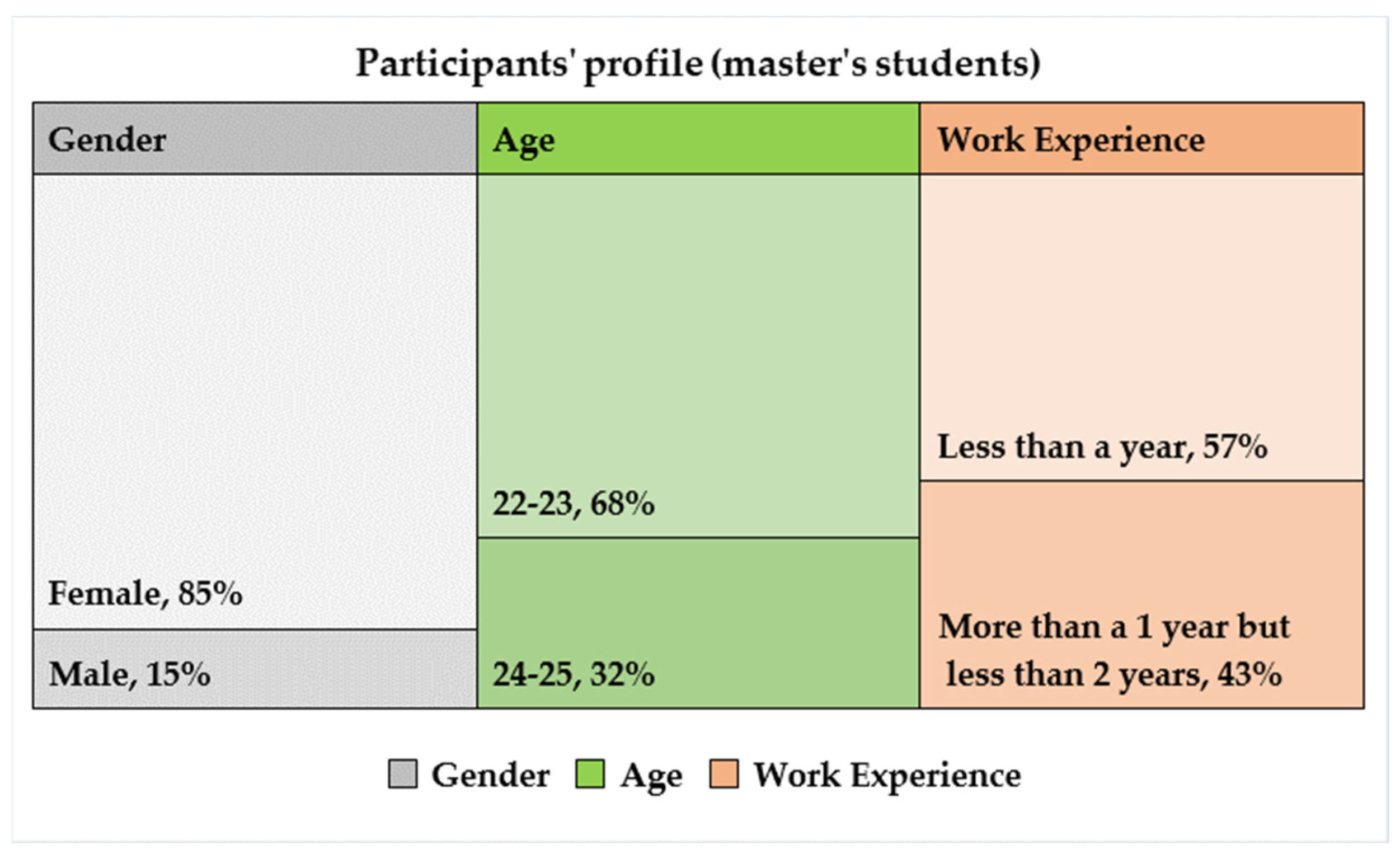

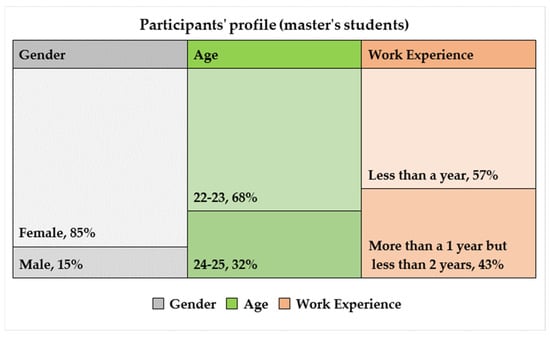

The survey aimed at identifying how well novice language teachers, who are non-native speakers, can mediate for learning, communication, and social environments based on their self-perceptions was conducted among 1-year master’s students pursuing a degree in teaching foreign languages (N = 47). The respondents’ profile is presented below (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Respondents’ profile.

To select the study participants (master’s students), a purposive sampling technique was used. This technique stipulates the selection of individuals or groups of individuals who have specific knowledge or are experienced with a phenomenon of interest. The choice of respondents was affected by several assumptions: (1) all respondents were supposed to have some prior experience in teaching foreign languages (from 6 months to ~1.5 years); (2) the participants were supposed to hold a bachelor’s degree in teaching methodology, as these respondents usually complete several pedagogic internships during the studies and possess sufficient theoretical background in foreign language teaching methodology; and (3) the sampling was supposed to exclude foreign students as some cultural and language issues could have arisen that were beyond the scope of this study. The major factors affecting the choice of sampling were the availability of respondents, their willingness, and consent to participate in the research.

2.3. Experimental Work

To develop illustrative descriptors of pedagogic mediation in a foreign language classroom, the study employed the research strategy presented in North B. and Piccardo E., “Developing illustrative descriptors of aspects of mediation for the CEFR” [19]. It comprised several stages:

Intuitive stage. The aim of this stage was to review relevant source material (CEFR-CV): select relevant descriptors from CEFR-CV, draft, edit, and discuss new illustrative descriptors for pedagogic mediation within a focus group [16,39]. This discussion was held within a focus group. The focus group consisted of six faculty members from the Graduate School of Linguistics and Pedagogy at Peter the Great St. Petersburg Polytechnic University. One member of the focus group acted as an observer and facilitator, taking notes and coordinating the discussion. The focus group guide included questions related to the formulation of illustrative descriptors of pedagogic mediation (What are the dimensions of pedagogic mediation? What is mediating learning? What is mediating communication? Do you agree that the domain “mediating communication” should include mediation activities like facilitating individual and group work? etc.). The data were collected and transcribed for further analysis and interpretation. At this stage, a draft of illustrative descriptors for pedagogic mediation in a foreign language classroom was developed.

Qualitative stage. This stage stipulated the summarizing of the descriptors. To finalize the draft of descriptors and relate them to a real teaching context, the method of non-participant observation was used. We observed 15 sessions, namely lectures and tutorials conducted in English by the faculty. The aim of the observation was to identify and recognize the developed descriptors in a practical context. This helped us edit the set of descriptors and match them to the university context.

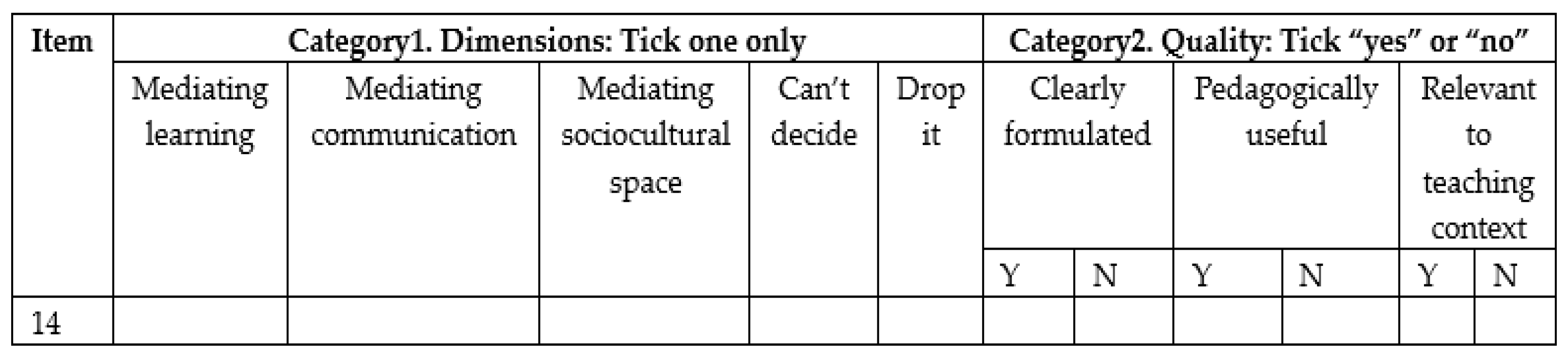

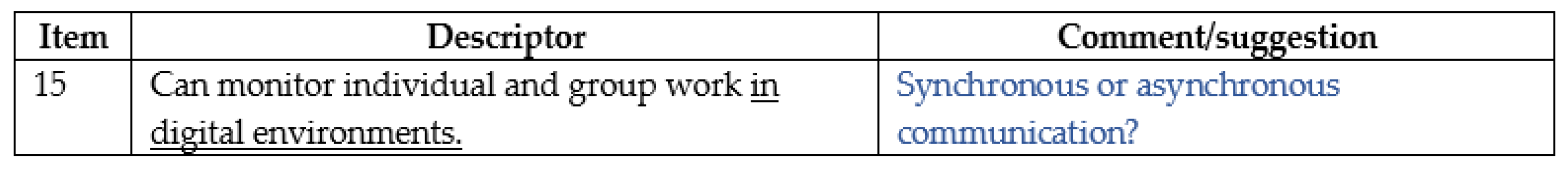

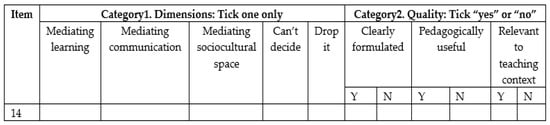

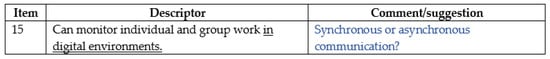

After that, the final draft of descriptors was verified by questioning 40 members of the faculty at the Institute of Humanities, SPBSTU. The main goal was to assess the descriptors in terms of phrasing and their correlation to the assigned domains (mediating learning, mediating communication, and mediating sociocultural space). For that, we developed the question list and prepared a list of descriptors, which were together distributed online among the faculty (Figure 3 and Figure 4). This allowed us to prepare the report, which contained information about the relevance and clarity of the developed descriptors.

Figure 3.

Question list.

Figure 4.

Descriptor list.

Quantitative stage. At this stage, we edited and identified the descriptors that should be included in the final list (Figure 3). For that, we calculated the percentage for each item (descriptor) in both categories (Category 1. Dimensions; Category 2. Quality) and nominated coefficients (for relevant descriptors—OKCoeff, for irrelevant—IRCoeff, and ClarCoeff, UseCoeff, RealCoeff for the items from category 2). We also adopted a subjective criterion for each coefficient, namely OKCoeff = 60%; IRCoeff = 25%; ClarCoeff, UseCoeff; RealCoeff = 75%. This allowed us to finally select the most relevant descriptors and correct or adjust their phrasing (Figure 4).

At this stage, we also developed a self-assessment form that included these descriptors as “can-do statements”. It was distributed among students taking their 1-year master’s program for teaching foreign languages (N = 47) in order to gather the data on students’ self-perceptions of their mediation skills. This self-assessment form was based on the 3-point Likert scale “agree”, “disagree”, and “not sure” and contained descriptors for each dimension of pedagogic mediation.

The results of the survey were anonymized regarding any personal information or other references that could have identified an individual. These findings could be further used to formulate the course objectives, taking into account learners’ needs and self-perceptions.

3. Results

Q2: What illustrative descriptors can depict the aspects of pedagogic mediation in a foreign language classroom?

Table 1 presents a set of descriptors developed in accordance with the research framework presented above.

Table 1.

Pedagogic mediation illustrative descriptors.

Q3: How well can novice language teachers, who are non-native speakers, mediate for learning, communication, and social environments?

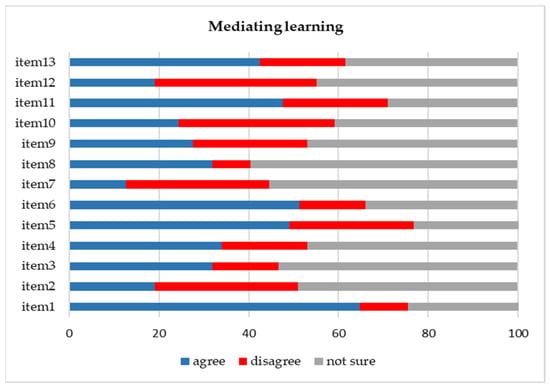

These descriptors were used to develop a self-assessment form that was distributed among 1-year master’s students taking a degree in foreign language teaching. The students were supposed to assess whether they could demonstrate the skills presented in the self-assessment as “can-do statements”. The figures below show the results of the assessment presented as percentages for each item of pedagogic mediation dimensions.

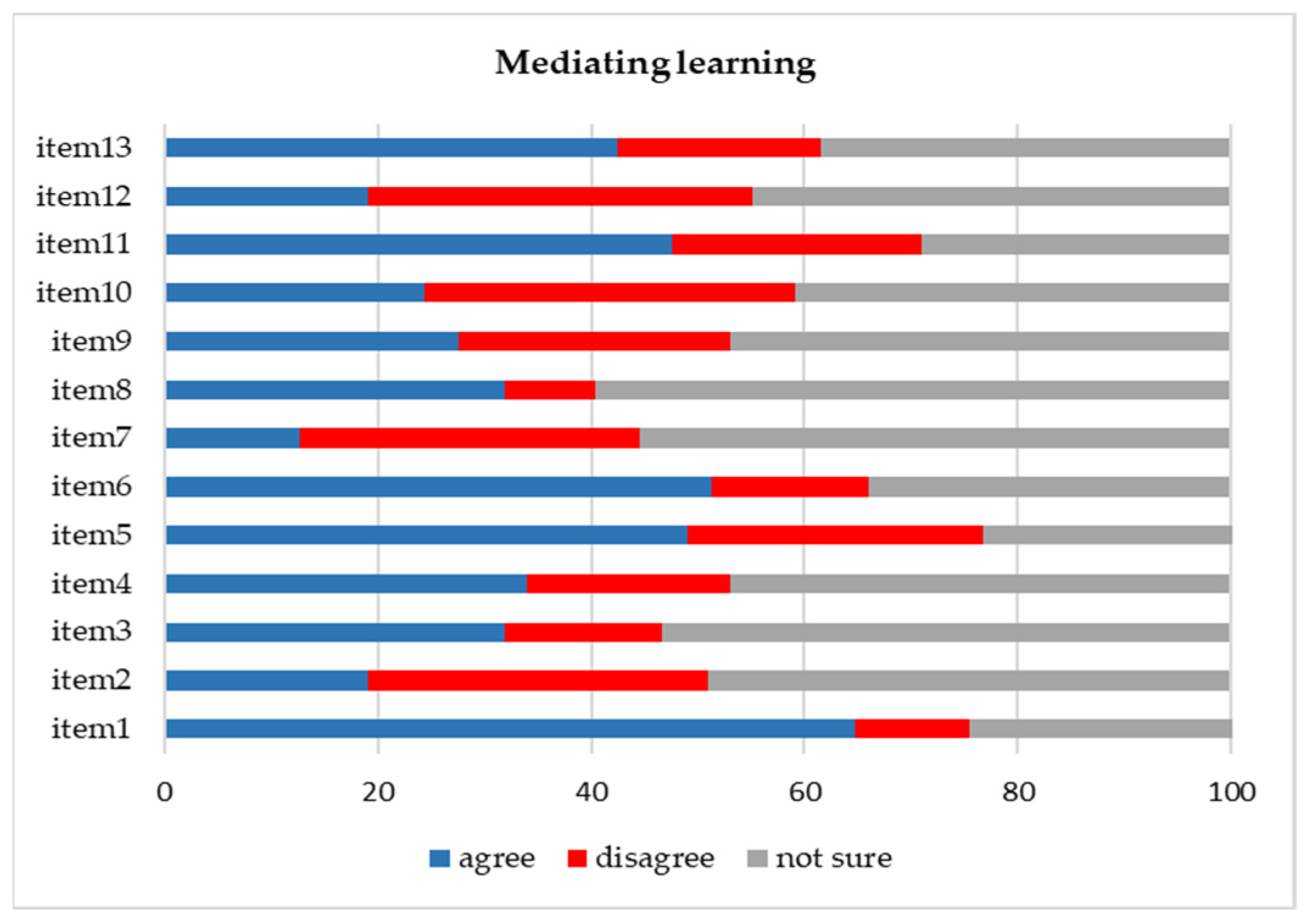

Figure 5 demonstrates the results obtained after the self-assessment of mediating learning skills among students. The majority of students agreed that they could paraphrase the language of a source text in order to facilitate comprehension (item 1, ~68% of students) and select specific visuals to support the concepts under discussion (infographics, memes, cultural images, visual metaphors, etc.) (item 13, ~42% of students). However, students reported experiencing difficulties breaking down complex information to adjust to the complexity of the material (item 2, ~31%) and using visual information as a source of cognitive stimulus (item 12, ~36%). Besides that, ~59% of students were unsure about their abilities to interpret and present the data from graphs, charts, and diagrams in a comprehensible and cohesive manner (item 8); ~55% of respondents hesitated on their ability to provide clear and precise instructions (item 7); and ~40% of students reported being unconfident in their skills of exploiting arguments from varied resources to evaluate comments or judgments (item 10).

Figure 5.

Results of students’ self-assessment in mediating for learning.

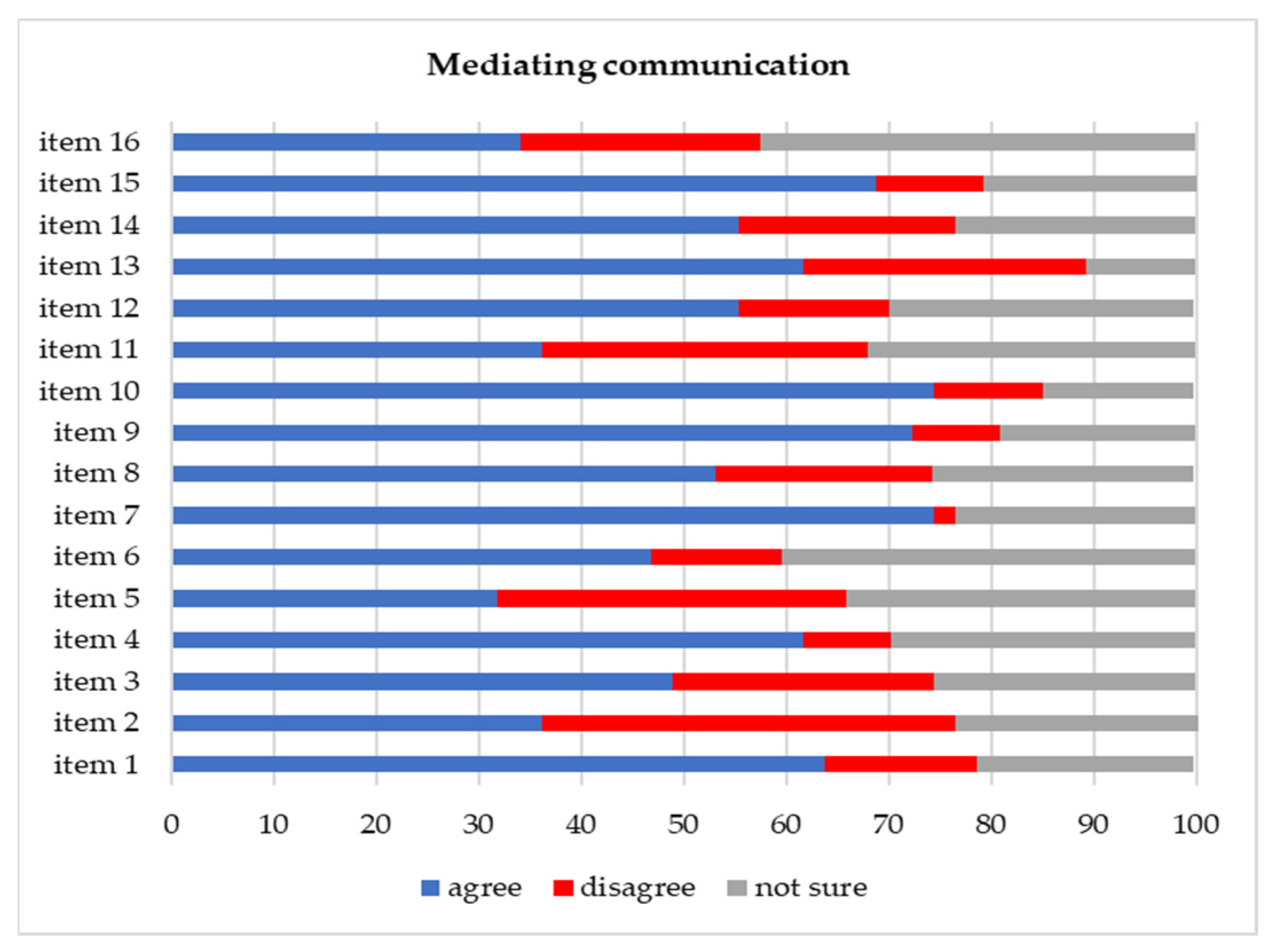

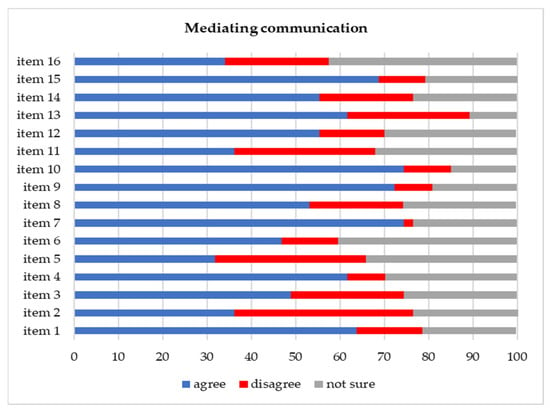

Figure 6 demonstrates the results obtained after the self-assessment of mediating communication skills among students. Interestingly, ~63% of students reported that they could vary different types of questions (closed questions, factual questions, why-questions, referential questions, etc.) (item 1); 61% of respondents stated that they were able to initiate a discussion (conceptual talk) (item 4); ~74% of students claimed that they could summarize the discussion to highlight the key points (item 7); ~72% of learners were sure that they could arrange turn-taking to move forward the learners’ discussion (item 9); and ~74% of students mentioned that they had the necessary skills to tactfully help learners finalize the discussion (item 10). Besides that, ~68% of respondents were sure about their abilities to explain the different roles of participants in the collaborative process, giving clear instructions for group work (item 15). This appeared to contradict what had been claimed by students before regarding item 7 in the mediation learning dimension. According to the obtained data, the most difficult task for students was setting an individual task for the participants who refused to work in a group (item 16, ~42% of students expressed doubts). In addition, ~40% of respondents disagreed that they were able to provide actionable feedback to learners (item 2).

Figure 6.

Results of students’ self-assessment in mediating for communication.

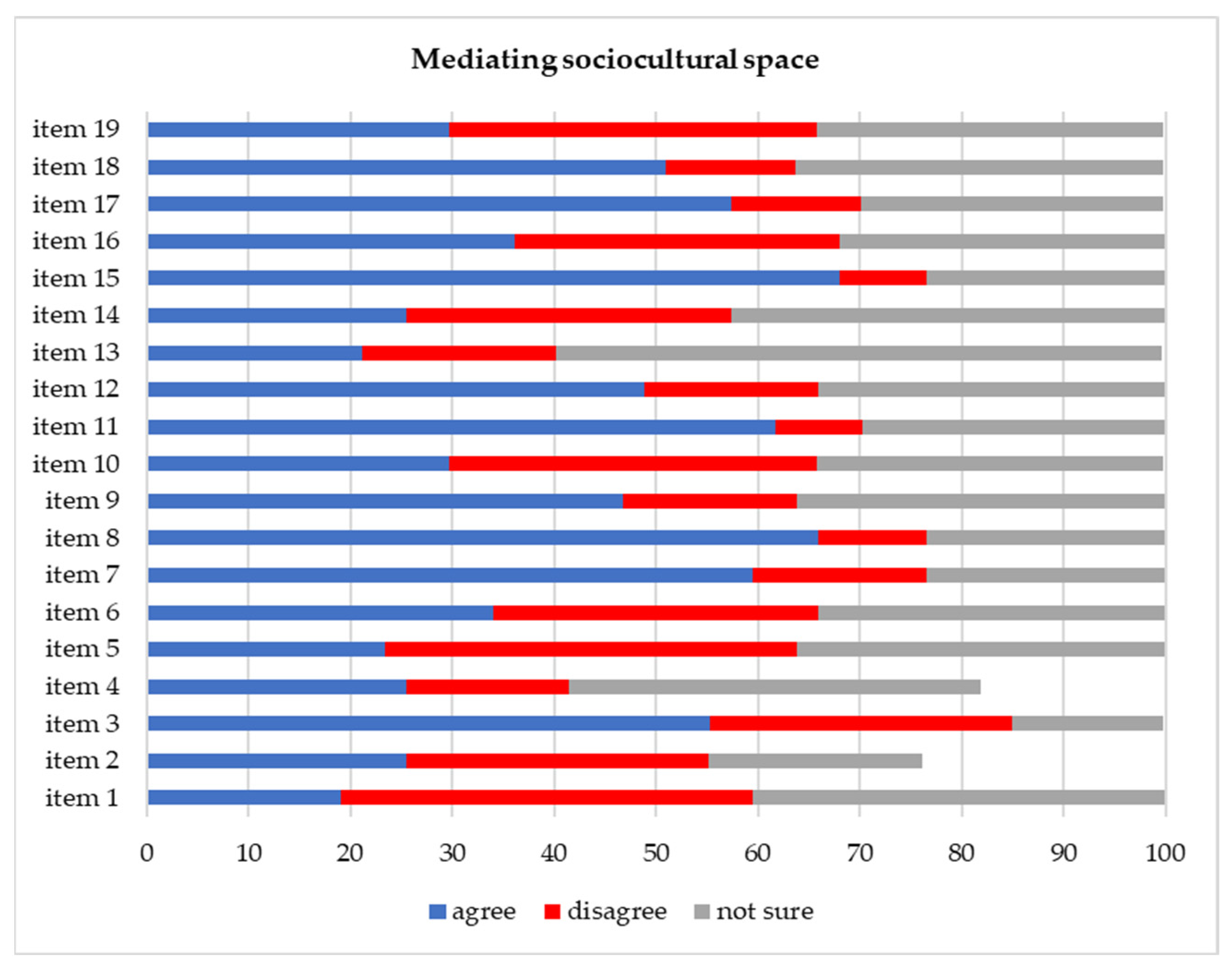

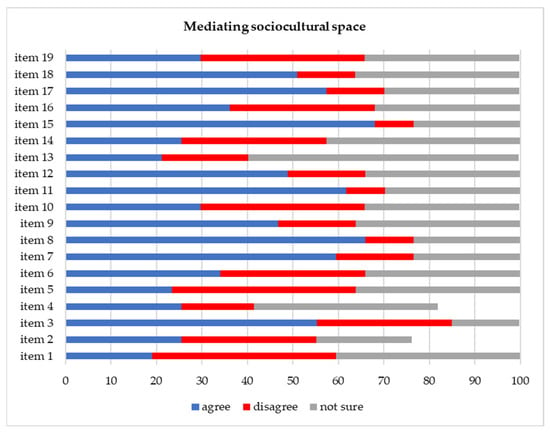

Figure 7 demonstrates the results obtained after the self-assessment of mediating sociocultural skills among students. According to the data, respondents disagreed (~40%) or were unsure (~41%) of their abilities to summarize, evaluate, and link the various contributions in order to facilitate agreement on a solution or a way forward (item 1). Besides that, students expressed concerns related to their skills of using persuasive language to suggest that parties in disagreement shift towards a new position (item 5; ~40% of respondents disagreed and ~36% were unsure). In addition, ~ 36% of students disagreed that they could guide a sensitive discussion effectively (item 10), and ~36% of respondents were unsure that they could, in intercultural encounters, demonstrate an appreciation of perspectives different from their own views (item 9). In addition, ~ 59% of students were not sure that they could establish effective communication practices in a digital environment to ensure learners’ contribution to the asynchronous discussion (item 13), and ~31% of respondents disagreed that they were able to structure the learning materials and adjust them to fit in a digital learning environment (item 14).

Figure 7.

Results of students’ self-assessment in mediating for sociocultural space.

4. Discussion

The aim of this study was to conceptualize the dimensions of pedagogic mediation in the context of foreign language teaching and learning as a theoretical and practical construct. Being integrated in varied social and professional settings, mediation can be approached within an educational context [40,41,42,43,44]. In this study, pedagogic mediation is considered a specific form of language educators’ communicative activity that embraces their instructional and interactional competencies for delivering effective instructions in varied social, cultural, and educational contexts. It was hypothesized that its performance requires the skills for facilitating learning, managing classroom interaction, and leveraging conflicting situations that might occur in an educational context. To validate this hypothesis, the study focused on the theoretical analysis of pedagogic mediation, its dimensions and descriptors within a foreign language teaching context, and the self-assessment of novice language teachers, who are non-native speakers, in order to identify the learning gaps. The concept of pedagogic mediation is relatively new in the field of language pedagogy, and its theoretical background and practical implications need further conceptualization [3,19]. This study advocates the need to accumulate different theoretical perspectives to develop a firm theoretical framework that could embrace the linguistic, cultural, social, and instructional aspects of this phenomenon.

4.1. Mediation in Foreign Language Education

Mediation in language education is gaining attention due to the overall shift in a teaching paradigm, in which a learner acts as a social agent who creates bridges and helps to construct or convey meaning in varied social and cultural settings [17,35]. It has been recognized that in modern globalized societies, language users tend to encounter situations in which they have to relay, transmit, or interpret information to those who have limited access to it, understanding and conveying the sociolinguistic and pragmatic peculiarities of language usage and contexts. In the studies on mediation for foreign language classrooms, the researchers focus on intralingual mediation, interlingual and cross-language mediation, sociocultural aspects of mediation in educational settings, and mediation activities for language learning assessment [3,18,45,46]. For instance, the research conducted within a “Mediation in teaching, learning and assessment” (METLA) project supports educators in designing and developing mediation activities and learning materials for their effective use in a multicultural educational environment [18]. Within this strand of research, the studies also emphasize the need to develop the plurilingual and pluricultural competencies of learners enabling them to act as cultural mediators in modern societies [2,47,48]. Besides that, when investigating the concept of mediation for professional language training, researchers raise questions about the necessity of designing and incorporating multilingual practices into translating and interpreting training programs, as well as into language training for specific purposes (law students) [49,50].

With the introduction of this concept into foreign language education, the role of an educator is transforming. A language educator has to possess the skills to identify instances of cross-language, intralingual, and cultural mediation in order to facilitate the learning process and classroom interaction within pluricultural and plurilingual educational contexts. This paradigm shift brings the concept of pedagogic mediation to light and encourages its investigation in a tight relation to culture, language, and learning. In this study, pedagogic mediation is thought to embrace three dimensions that depict the core educators’ activities in a foreign language classroom (Figure 1).

4.2. Mediating Learning

In current research, the concept of mediation has been conceptualized as an instructional framework that helps learners acquire the necessary skills and knowledge. It is considered a teaching strategy that is used by educators to enhance the cognitive development of learners. Mediation for learning appears as educational interventions through specially designed symbolic tools, people, or learning activities. The basic theoretical assumption regarding mediated learning experiences (MLEs) is that an individual’s level of cognitive functioning is directly linked to the quantity and quality of mediated learning experiences (MLEs) they receive [23]. For this, a mediator intentionally filters and focuses the stimuli, ordering and organizing them, and regulating their intensity, frequency, and sequence. Being embedded in a constructivist paradigm, mediation strategy can take varied forms in a classroom, for instance, scaffolding or peer-assisted mediation [51,52]. To implement this strategy, an educator may use varied tools such as textbooks, visual aids, or technology to design and enact instruction [53]. It has been recognized that mediation can take an instructional form through scaffolding, modeling, activating, and building on previous knowledge and skills [28]. One of the most powerful tools of mediation for learning is language [22]. Language as a specific tool for mediation encourages meaningful interaction between a teacher, learners, and the environment. It is of particular importance in language classrooms as it becomes the main source of meanings and linguistic, cultural, and interactional patterns. Through modeling and scaffolding, language teachers support learners in their acquisition of linguistic, communicative, and social behavior patterns. To this end, language teachers should have varied skills such as explaining concepts, giving clear instructions, grading the language to adapt the text, and using visuals to stimulate learners’ communicative and cognitive activity (Table 1). The results of the students’ self-assessment showed that students experienced difficulties in breaking down complex information to adjust to the complexity of the material (item 2, ~31%, Figure 5), using visual information as a source of cognitive stimulus (item 12, ~36%, Figure 5) or providing clear and precise instructions (item 7, ~55%, Figure 5). These results advocate the necessity of designing training materials for language teachers that could allow pre-service language teachers to advance their mediation skills for learning.

4.3. Mediating Communication

Instructional communication and classroom discourse constitute a specific strand of research in communication studies. The researchers focus on linguistic and interactional patterns that are common for communication within an educational context. However, little attention has been given to the design of training programs and materials for pre-service language teachers in order to enhance their abilities for effective classroom interaction. Meanwhile, the study conducted within this research showed the most difficult task for students related to their abilities to manage interaction and negotiation, namely, 42% of respondents stated that they doubted their skills to negotiate with learners who refused to work in a group (item 16), and ~40% of respondents disagreed that they were able to provide actionable feedback to learners (item 2, Figure 6). Some of the challenges that novice language teachers face were discussed in the studies. For instance, it was reported that novice language teachers experienced difficulties in managing class time, meeting learners’ needs and interests, teaching speaking skills, managing students with mixed abilities, and adapting to the work environment [54,55]. The studies mostly focus on challenges and difficulties that novice teachers experience in relation to classroom management, and fewer studies identify the pitfalls in communication among non-native language teachers. The ability to mediate communication is essential for language teachers; therefore, they should be specifically addressed within a curriculum that aims at training non-native speakers.

4.4. Mediating Sociocultural Space

Language educators as mediators should demonstrate the skills of social mediation in varied educational settings, namely, in intercultural encounters, conflicting situations, and digital environments. The results of the self-assessment showed that ~ 36% doubted they could guide a sensitive discussion effectively (item 10, Figure 7), and the same percentage of respondents were unsure they could use persuasive language to help the parties in disagreement shift to another position (item 5, Figure 7). These results identify a need for fostering social competence among pre-service language teachers. This question has been partly addressed in studies that focus on the social–emotional competence of novice teachers during pre-service preparation [56,57]. These studies highlight the correlation between the social competencies of novice teachers with their abilities to manage a classroom and develop professionally in their careers. Another issue that needs to be addressed is the ability of students to adapt to digital learning environments. The results showed that students experienced difficulties in structuring and designing materials for digital learning as well as in managing the online interaction of learners (Figure 7). Although these skills of educators are widely discussed in the literature, there appears to be a demand for consistent and targeted training aimed at fostering learners’ abilities to effectively mediate in a digital environment.

4.5. Summary

The experimental work conducted in this research was focused on the self-assessment of pedagogic mediation skills by novice language teachers, who are non-native speakers. It was performed to understand the learners’ need for acquiring pedagogic mediation skills as well as to check the applicability of the designed theoretical construct. The results of the self-assessment showed that pre-service teachers expressed concerns about their abilities to give actionable feedback, arrange instructional material for a digital environment, give instructions, communicate in situations of disagreement, and manage situations of intercultural encounters. These issues have been highlighted in the studies related to the research on instructional communication, classroom discourse, and mediation as a social and cultural practice [15,33,34,41,58].

However, attempts to present pedagogic mediation as a concept bringing these strands of research together are scarce. Meanwhile, pedagogic mediation as a theoretical and practical concept may transform the existing practices of designing teacher-training programs. It might allow for the development of a curriculum that helps learners develop a holistic approach to their professional activities.

4.6. Limitations, Theoretical and Practical Implications, and Further Research

This study might be appealing to those who are interested in rethinking the role of a language educator. The results of the study reveal several theoretical and practical implications: (1) The theoretical perspective presented in this study might lay the theoretical foundation for further research in pedagogic mediation for foreign language classrooms; (2) the theoretical and practical results of the study might become a useful source of knowledge and information applicable for the development of learning materials and assessment procedures to meet the objectives of pre-service training programs in language education; and (3) the theoretical and practical ideas presented in the study might be used to design an instructional framework aimed at fostering the skills of novice language educators, who are non-native speakers.

However, the study contains some limitations. These limitations are related to the respondents’ profile and the research design. The sampling pool included students in their first year pursuing a master’s degree, but it did not include post-graduate students or international students. Besides that, the primary goal of the study was to identify the illustrative descriptors for pedagogic mediation and verify them towards the learners’ self-perceptions; therefore, it might be reasonable to advance this research with the study on teacher–trainers’ perceptions.

Future studies in this area may focus on (1) advancing the theoretical framework of pedagogic mediation; (2) identifying methods and strategies for teaching mediation skills within pre-service training programs in language education; (3) designing relevant instructional materials; and (4) validating developed illustrative descriptors in varied cultural settings.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, N.K., A.R. and D.B.; methodology, N.K., A.R. and D.B.; validation, N.K., A.R. and D.B.; formal analysis, N.K. and A.R.; investigation, N.K., A.R. and D.B.; data curation, N.K., A.R. and D.B.; writing—original draft preparation, N.K.; writing—review and editing, N.K., A.R. and D.B.; visualization, N.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The study was supported by the Ministry of Science and Higher Education of the Russian Federation. The strategic academic leadership program “Priority 2030” (Agreement 075-15-2021-1333 dated 30 September 2021).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical approval was received from the Ethics Commission (#3 dated 26 February 2021) founded by the Institute of Humanities, Peter the Great St. Petersburg Polytechnic University, which is ruled by the code of ethics of the Russian Society of Sociologists.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data of this article emerges from the larger scale ongoing project conducted by the authors and are protected by the ethical protocols issued by the Institutes.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Kramsch, C. Language and Culture. AILA Rev. 2014, 27, 30–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L. Culture Teaching in Foreign Language Teaching. Theory Pract. Lang. Stud. 2013, 3, 371–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stathopoulou, M. Cross-Language Mediation in Foreign Language Teaching and Testing; Multilingual Matters: Bristol, UK; Buffalo, NY, USA; Toronto, ON, Canada, 2015; ISBN 978-1-78309-411-0. [Google Scholar]

- Munduate, L.; Medina, F.J.; Euwema, M.C. Mediation: Understanding a Constructive Conflict Management Tool in the Workplace. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 2022, 38, 165–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibarrola-García, S.; Iriarte, C. Socio-Emotional Empowering through Mediation to Resolve Conflicts in a Civic Way. Lond. Rev. Educ. 2014, 12, 261–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coste, D.; Cavalli, M. Education, Mobility, Otherness. The Mediation Functions of Schools; Education Department, Council of Europe: Strasbourg, France, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Koskinen, K.; Kinnunen, T. Mediation in FL Learning: From Translation to Translatoriality. Stridon. J. Stud. Transl. Interpret. 2022, 2, 5–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín, M.C.; Phelan, M. Interpreters and Cultural Mediators—Different but Complementary Roles. Translocat. Migr. Soc. Chang. 2010, 6. [Google Scholar]

- Carter, A.; Watts, S. The Role of Language Interpretation in Providing a Quality Mediation Process. Contemp. Asia Arbitr. J. 2016, 9, 301–316. [Google Scholar]

- Piccardo, E. Mediation and the Plurilingual/Pluricultural Dimension in Langauge Education. ILD 2023, 14, 24–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erdilmen, M. Frameworks and Good Practices of Intercultural Mediation for Migrant Integration in Europe. Available online: https://eea.iom.int/resources/frameworks-and-good-practices-intercultural-mediation (accessed on 8 April 2024).

- Zarate, G.; Europarat; Council of Europe Publishing (Eds.) Cultural Meditation in Language Learning and Teaching: Research Project; Ed. du Conseil de l’Europe: Strasbourg, France, 2004; ISBN 978-92-871-5259-6. [Google Scholar]

- Flavian, H. Mediation and Thinking Development in Schools: Theories and Practices for Education; Emerald Publishing Ltd.: Bingley, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, X.; Cheng, H. Review of Mediation from the Social Constructivist Perspective and Its Implications for Secondary School EFL Classrooms in China. Theory Pract. Lang. Stud. 2012, 2, 808–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busch, D. Cross-Cultural Disputes and Mediator Strategies. In The Routledge Handbook of Intercultural Mediation; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2022; pp. 30–42. ISBN 978-1-00-322744-1. [Google Scholar]

- Europarat (Ed.) Common European Framework of Reference for Languages: Learning, Teaching, Assessment; Companion Volume; Council of Europe Publishing: Strasbourg, France, 2020; ISBN 978-92-871-8621-8. [Google Scholar]

- Mediation: What It Is, How to Teach It and How to Assess It; Part of the Cambridge Papers in ELT and Education Series; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2022.

- Stathopoulou, M.; Gauci, P.; Liontou, M.; Melo-Pfeifer, S. Mediation in Teaching, Learning & Assessment (METLA). A Teaching Guide for Language Educators; Council of Europe Publishing: Strasbourg, France, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- North, B.; Piccardo, E. Developing Illustrative Descriptors of Aspects of Mediation for the CEFR; Education Policy Division, Council of Europe: Strasbourg, France, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Cavalli, M.; Coste, D.; Egli Cuenat, M.; Goullier, F.; Panthier, J. Guide for the Development and Implementation of Curricula for Plurilingual and Intercultural Education; Beacco, J.-C., Byram, M., Eds.; Council of Europe Publishing: Strasbourg, France, 2016; ISBN 978-92-871-8234-0. [Google Scholar]

- Bagshaw, D. Mediation in the World Today: Opportunities and Challenges. J. Mediat. Appl. Confl. Anal. 2015, 2, 187–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vygotsky, L. Mind and Society: The Development of Higher Psychological Processes; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Feuerstein, R.; Hoffman, M.B.; Rand, Y.; Jensen, M.R.; Tzuriel, D.; Hoffmann, D.B. Learning to Learn: Mediated Learning Experiences and Instrumental Enrichment. Spec. Serv. Sch. 1985, 3, 49–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Troitsky, Y.L.; Maksimova, N.V.; Albul, L.G.L.S. Vygotsky’s Idea of Mediation: Semiotic and Educational Projections. Cult.-Hist. Psychol. 2023, 19, 18–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Presseisen, B.Z.; Kozulin, A. Mediated Learning: The Contributions of Vygotsky and Feuerstein in Theory and Practice. In Proceedings of the Mediated Learning: The Contributions of Vygotsky and Feuerstein in Theory and Practice; Research for Better Schools, Inc.: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Daniels, H. Mediation: An Expansion of the Socio-Cultural Gaze. Hist. Hum. Sci. 2015, 28, 34–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniels, H.; Cole, M.; Wertsch, J.V. (Eds.) The Cambridge Companion to Vygotsky; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2007; ISBN 978-0-521-83104-8. [Google Scholar]

- Taber, K.S. Mediated Learning Leading Development—The Social Development Theory of Lev Vygotsky. In Science Education in Theory and Practice; Akpan, B., Kennedy, T.J., Eds.; Springer Texts in Education; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 277–291. ISBN 978-3-030-43619-3. [Google Scholar]

- Katt, J.A.; McCroskey, J.C.; Sivo, S.A.; Richmond, V.P.; Valencic, K.M. A Structural Equation Modeling Evaluation of the General Model of Instructional Communication. Commun. Q. 2009, 57, 239–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCroskey, J.C.; Valencic, K.M.; Richmond, V.P. Toward a General Model of Instructional Communication. Commun. Q. 2004, 52, 197–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, J. A Functional Review of Research on Clarity, Immediacy, and Credibility of Teachers and Their Impacts on Motivation and Engagement of Students. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 712419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardman, J. Opening-up Classroom Discourse to Promote and Enhance Active, Collaborative and Cognitively-Engaging Student Learning Experiences. In Innovative Language Teaching and Learning at University: Enhancing Participation and Collaboration; Goria, C., Speicher, O., Stollhans, S., Eds.; Research-Publishing.net: Dublin, Ireland; Voillans, France, 2016; pp. 5–16. ISBN 978-1-908416-32-2. [Google Scholar]

- Lefstein, A.; Snell, J. Classroom Discourse: The Promise and Complexity of Dialogic Practice. In Applied Linguistics and Primary School Teaching; Ellis, S., McCartney, E., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2011; pp. 165–185. ISBN 978-0-511-92160-5. [Google Scholar]

- Walsh, S. Investigating Classroom Discourse; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2006; ISBN 978-1-134-21900-1. [Google Scholar]

- Dendrinos, B. Mediation in Communication, Language Teaching and Testing. J. Appl. Linguist. 2006, 22, 9–35. [Google Scholar]

- Nieto, S. Becoming Sociocultural Mediators. Issues Teach. Educ. 2017, 26, 129–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altınay-Gazi, Z.; Altınay-Aksal, F. Technology as Mediation Tool for Improving Teaching Profession in Higher Education Practices. EURASIA J. Math. Sci. Technol. Educ. 2017, 13, 803–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busetto, L.; Wick, W.; Gumbinger, C. How to Use and Assess Qualitative Research Methods. Neurol. Res. Pract. 2020, 2, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- North, B.; Piccardo, E.; Goodier, T.; Fasoglio, D.; Margonis-Pasinetti, R.; Rüschoff, B. Enriching 21st Century Language Education. The CEFR Companion Volume in Practice; Council of Europe Publishing: Strasbourg, France, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Henning, E. Teaching as Dialogic Mediation: A Learning Centred View of Higher Education. S. Afr. J. High. Educ. 1998, 12, 60–68. [Google Scholar]

- Bracco, F.; Gattiglia, N.; Greggio, G.; Morelli, M. Learning-by-Mediating. Reflexive Mediation in Action. Techno Rev. Int. Technol. Sci. Soc. Rev./Rev. Int. De Tecnol. Cienc. Y Soc. 2022, 11, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahveci, M. Pedagogical Mediation: Media as Communication Concept. Univ. Misao—Časopis Za Nauk. Kult. I Umjet. 2018, 17, 125–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyndon, H.; Bertram, T.; Brown, Z.; Pascal, C. Pedagogically Mediated Listening Practices; the Development of Pedagogy through the Development of Trust. Eur. Early Child. Educ. Res. J. 2019, 27, 360–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, C.; Jenkins, J. Mediating Communication—ELF and Flexible Multilingualism Perspectives on the Common European Framework of Reference for Languages. Aust. J. Appl. Linguist. 2020, 3, 26–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zvereva, E.; Chilingaryan, K. Interlingual Mediation in Foreign Language Teaching. In Proceedings of the ADVED 2019—5th International Conference on Advances in Education and Social Sciences, Istanbul, Turkey, 21 October 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Poehner, M.E.; Inbar-Lourie, O. (Eds.) Toward a Reconceptualization of Second Language Classroom Assessment: Praxis and Researcher-Teacher Partnership; Educational Linguistics; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; Volume 41, ISBN 978-3-030-35080-2. [Google Scholar]

- Ara, R.; Zarin, I. Mediating Cross-Cultural Barriers in English as a Foreign Language Classroom: A Pilot Study on Teachers. Br. J. Educ. 2018, 6, 46–57. [Google Scholar]

- Stathopoulou, M. From “Languaging” to “Translanguaging”: Reconsidering Foreign Language Teaching and Testing through a Multilingual Lens. In Proceedings of the Selected Papers of the 21st International Symposium on Theoretical and Applied Linguistics (ISTAL 21), Thessaloniki, Greece, 5–7 April 2013; pp. 759–774. [Google Scholar]

- Chovancová, B. Practicing the Skill of Mediation in English for Legal Purposes. Stud. Log. Gramm. Rhetor. 2018, 53, 49–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidhofer, A.; Herrero, E.C.; Koletnik, M. Integrating Mediation and Translanguaging into TI-Oriented Language Learning and Teaching (TILLT). Lub. Stud. Mod. Lang. Lit. 2022, 46, 99–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taber, K.S. Scaffolding Learning: Principles for Effective Teaching and the Design of Classroom Resources. In Effective Teaching and Learning: Perspectives, Strategies and Implementation; Nova Science Publishers: New York, NY, USA, 2018; pp. 1–43. [Google Scholar]

- Fathi, S.; Shabani, E.A. The Effect of Teacher- and Peer-Assisted Evaluative Mediation on EFL Learners’ Metacognitive Awareness Development. Englisia J. Lang. Educ. Humanit. 2020, 8, 58–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LaScotte, D.K.; Mathieu, C.S.; David, S.S. (Eds.) New Perspectives on Material Mediation in Language Learner Pedagogy; Educational Linguistics; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; Volume 56, ISBN 978-3-030-98115-0. [Google Scholar]

- Chandran, V.N.; Albakri, I.S.M.A.; Shukor, S.S.; Ismail, N.; Tahir, M.H.M.; Mokhtar, M.M.; Zulkepli, N. Malaysian English Language Novice Teachers’ Challenges and Support During Initial Years of Teaching. Stud. Engl. Lang. Educ. 2022, 9, 443–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Öztürk, M.; Yildirim, A. Adaptation Challenges of Novice Teachers. Hacet. Üniversitesi Eğitim Fakültesi Derg. [H. U. J. Educ.] 2013, 28, 294–307. [Google Scholar]

- Dung, D.T.; Zsolnai, A. Teachers’ Social and Emotional Competence: A New Approach of Teacher Education in Vietnam. Hung. Educ. Res. J. 2021, 12, 131–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Zhu, X.; Tian, G.; Kang, X. Exploring the Relationships between Pre-Service Preparation and Student Teachers’ Social-Emotional Competence in Teacher Education: Evidence from China. Sustainability 2023, 15, 2172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamamorad, A.M. Teacher as Mediator in the EFL Classroom: A Role to Promote Studnets’ Level of Interaction, Activeness, and Learning. Int. J. Engl. Lang. Teach. 2016, 4, 64–70. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).