Instrument to Evaluate Intercultural Competence in Pedagogy Students

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Instrument

2.3. Procedure

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Instrument

3.2. Content Validation

3.3. Results of the Instrument Applied

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Deardorff, D. Handbook for the Development of Intercultural Competencies; Storytelling Circles; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Bennett, M.J. Towards Ethnorelativism: A Developmentalist Model of Intercultural Sensitivity In Education for the Intercultural Experience, 2nd ed.; Paige, R.M., Ed.; Intercultural Press: Yarmouth, ME, USA, 1993; pp. 21–71. [Google Scholar]

- Gudykunst, W.B. Towards a Theory of Effective Interpersonal Intergroup Communication: An Anxiety/Uncertainty Management (AUM) Perspective. In Intercultural Communicative Competence; Wiseman, R.L., Koester, J., Eds.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1993; pp. 33–71. [Google Scholar]

- Byram, M. Teaching and Assessment of Intercultural Communicative Competence; Multilingual Matters Ltda: London, UK, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Deardorff, D. The identification and assessment of intercultural competence as a result of the internationalization of students in institutions of higher education in the United States. J. Int. Educ. Stud. 2006, 10, 241–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cervantes Institute. European Reference Framework for Language Learning, Teaching and Assessment; Cervantes Institute: Madrid, Spain, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. UNESCO Guidelines on Intercultural Education; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Walsh, C. Critical Interculturality and (de)Coloniality; Editorial Abya Yala: Quito, Ecuador, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Mardones, T. Intercultural education in the Chilean national curriculum. J. Educ. Intersect. 2017, 7, 69–84. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Social Development and Family. National Socioeconomic Characterization Survey (CASEN); Ministry of Social Development and Family: Santiago, Chile, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Poblete, R. Working with diversity from the curriculum in schools with the presence of migrant children: A case study in schools in Santiago de Chile. Educ. Profiles. 2018, 40, 51–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanhueza, S.; Cardona, M.C. Evaluation of intercultural sensitivity in primary school students enrolled in culturally diverse classrooms. J. Educ. Res. 2009, 27, 247–262. [Google Scholar]

- Mena, E.M.; Díez, J.P. Didactics for Multilingualism in Teacher Education: An Empirical Study from the Practicum. Open Classr. 2015, 43, 94–101. [Google Scholar]

- Campos-Bustos, J. Haitian Students in Chile: Approaches to the Processes of Linguistic Integration in the Classroom. J. Educ. 2019, 43, 433–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vine, A.; Ferreira, A. Improvement of communicative competence in Spanish as a foreign language through video communication. J. Theor. Appl. Linguist. 2012, 50, 139–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Usallán, L. Cultural Pluralism and the Political Management of Immigration in Chile: Absence of a Model? Polis 2015, 14, 277–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vila, E.; Cortés, P.; Martín, V. Teacher training and the importance of intercultural and emotional competencies from an ethical perspective. Modulema 2017, 1, 5–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibáñez, N.; Figueroa, A.M.; Rodríguez, M.S.; Aros, A. Interculturality in Teacher Training: A Contribution from the Voices of People of Indigenous Peoples. Pedagog. Stud. 2018, 44, 225–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fong, C.S.; De Witt, D. Development of intercultural communicative competence: Formative assessment tools for Mandarin as a foreign language. Malays. J. Learn. Instr. 2019, 16, 97–123. [Google Scholar]

- Bernal, A. Authentic materials and tasks as mediators to develop the intercultural competence of EFL students. HOW J. 2020, 27, 29–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espinoza, E.; Herrera, L.A.; Castellano, J.M. The Intercultural Dimension in Teacher Training in Ecuador. Psychol. Soc. Educ. 2019, 11, 341–354. [Google Scholar]

- Tosuncuoglu, I. Awareness of the intercultural communicative competence of Turkish students and instructors at university level. Int. J. High. Educ. 2019, 8, 44–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nur Gedik, B.; Perihan, S. Intercultural Language Teaching and Learning: Teachers’ Perspectives and Practices. Particip. Educ. Res. 2022, 9, 268–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeynep, Y.; Kemal Sinan, Ö. Developing Critical Intercultural Competence in Second Language Teacher Education. J. Educ. Teach. 2021, 8, 1022–1037. [Google Scholar]

- Pagés, J.; Vega, J.C.; Camacho, Y. Conceptual framework for developing intercultural competence in the teaching-learning process of English. Varona. Sci.-Methodol. J. 2019, 68, 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Veliz, L.; Bianchetti, A.F.; Silva, M. Intercultural Competencies in Primary Health Care: A Challenge for Higher Education in Contexts of Cultural Diversity. Cad. Saúde Pública 2019, 35, e00120818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marek, E.; Nemeth, T. Intercultural competences in healthcare. Orv. Hetil. 2020, 161, 1322–1330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- González, H.; Álvarez-Castillo, J.; Fernández-Caminero, G. Development and validation of a scale to measure intercultural empathy. Relief 2015, 21, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro, A. The Assessment of Cultural Competencies: Validation of the ICC Inventory. Interdisciplinary 2012, 29, 109–132. [Google Scholar]

- Sanhueza, S.; Patrick, P.; Hsu, C.; Dominguez, J.; Friz, M.; Quintriqueo, S. Intercultural Communicative Competencies in Initial Teacher Training: The Case of Three Regional Universities in Chile. Pedagog. Stud. 2016, 42, 183–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Garrote, M.; Fernández, M. Intercultural competence in teaching: Defining the intercultural profile of student teachers. Bellaterra J. Lang. Lit. Teach. Learn. 2016, 9, 41–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buendía, L.; Colás, P.; Hernández-Pina, P. Research Methods in Educational Psychology; McGraw-Hill: Madrid, Spain, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Matas, A. Design of the Likert scale format: A state of the art. Electron. J. Educ. Res. 2018, 20, 38–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asún, R.; Zúñiga, C. Advantages of Polytomic Models of Item Response Theory in the Measurement of Social Attitudes: The Analysis of a Case. Psykhe 2008, 17, 103–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez, C.; Pozo, T.; Gutiérrez, J. Analytical triangulation as a resource for the validation of recurrent survey studies and replication research in Higher Education. RELIEF. Electron. J. Educ. Res. Eval. 2006, 12, 289–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Díaz, E.; Fernández-Cano, A.; Faouzi, T.; Henríquez, C. Validation of the underlying construct in a scale to evaluate the impact of educational research on teaching practice by means of confirmatory factor analysis. J. Educ. Res. 2015, 33, 47–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baghestani, A.R.; Ahmadi, F.; Tanha, A.; Meshkat, M. Bayesian Critical Values for Lawshe’s Content Validity Relation. Meas. Eval. Couns. Dev. 2019, 52, 69–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero Jeldres, M.; Díaz Costa, E.; Faouzi Nadim, T. A Review of Lawshe’s Method for Calculating Content Validity in the Social Sciences. Front. Educ. 2023, 8, 1271335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrión, C.; Soler, M.; Aymerich, M. Analysis of the Content Validity of a Problem-Based Learning Assessment Questionnaire: A Qualitative Approach. Univ. Educ. 2015, 8, 13–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roussel, P.; Durrieu, F.; Campoy, E. Structural Equation Methods: Research and Applications in Management; Economica: Paris, France, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Urbano, A.; Iglesias, M.T.; Martínez, R. Design and validation of the Timeshare Scale in the Couple (TCP). Psychol. Soc. Educ. 2019, 11, 165–175. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez-Gómez, J.A.; Bolívar-Suárez, Y.; Yanez-Peñuñuri, L.Y.; Gaviria-Gómez, A.M. Validation of the Dating Violence Questionnaire (DVQ-R) for victims in Colombian and Mexican young adults. RELIEVE 2021, 27, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonald, R.P.; Ho, M.-H.R. Principles and Practice in Structural Equation Analysis Reporting. Psychol. Methods 2002, 7, 64–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moral, J. Confirmatory factor analysis In Estadística con SPSS y Método de la Investigación; Landero, R., González, M.T., Eds.; Trails: María Anaya, Mexico, 2006; pp. 445–528. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluation of structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tilden, V.; Nelson, C.; May, B. Use of qualitative methods to improve the validity of content. Nurs. Res. 1990, 39, 172–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klein, J.; Wikan, G. Teacher education and international practice programmes: Reflections on transformative learning and global citizenship. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2019, 79, 93–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamora-de-Ortiz, M.; Serrano, F.; Martínez, M. Content validity of the P-VIRC didactic model (ask-see, interpret, walk, tell) through expert judgment. Univ. Educ. 2020, 13, 43–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazán, A.; Barrera, D.; Vega, N. Validation of constructs of reading skills and text production at the beginning of the generalization of the Reform in Mexican primary school. REICE Ibero-Am. J. Qual. Eff. Chang. Educ. 2013, 11, 61–76. [Google Scholar]

- Martín-Pastor, E.; Sánchez-Barbero, B.; Corrochano, D.; Gómez-Gonçalves, A. What competencies and skills identify a good teacher? Design of an instrument to measure the perceptions of preservice teachers. Educ. Sci. 2023, 13, 789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granero Gallegos, A.; Baena-Extremera, A.; Escaravajal, J.C.; Baños, R. Validation of the Academic Self-Concept Scale in the Spanish University Context. Educ. Sci. 2021, 11, 653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez Fuentes, S.; Jiménez Hernández, D.; Sancho Requena, P.; Moreno-Medina, I. Validation of an Instrument to Measure Teachers’ Perceptions of Universal Design for Learning. Lat. Am. J. Incl. Educ. 2019, 13, 89–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mardones, T. Intercultural Education: Constructions of National Identity and Otherness Present in the Discourse of Chile’s Official Curriculum. Braz. J. Dev. 2020, 6, 61270–61277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazykhankyzy, L.; Alagö, N. To develop and validate a scale to measure the intercultural communicative competence of Turkish and Kazakh ELT trainee teachers. Int. J. Instr. 2019, 12, 931–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Unit of Analysis | Theoretical Dimensions | Theoretical Concepts Item Producers | Article |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intercultural Competence (IC) | Attitude | Respect | 1-19-37-2-20-38 |

| Curiosity | 3-21-39-4-22-40 | ||

| Aperture | 5-23-41 | ||

| Knowledge and Understanding | Cultural Self-Awareness | 6-24-42 | |

| Deep Cultural Knowledge | 7-25-43-8-26-44 | ||

| Sociolinguistic awareness | 9-27-45-10-28-46 | ||

| Skills | Knowledge Processing | 47-29-11-12-48-30-13-31-49 | |

| Desired Internal Outcomes | Adaptability | 14-32-50 | |

| Ethnorelative perspective | 15-33-51 | ||

| Empathy | 16-34-52 | ||

| Flexibility | 17-35-53-18-54-36 |

| P 01: I show an interest in other cultures. |

| Q 19: I listen carefully to people with a different culture than I do. |

| P 37: I value a different culture than the one I own. |

| Q 20: I value people of different cultures, races, and nationalities than my own. |

| P 21: I react acceptably to communicative situations with people from other cultures. |

| P 39: I like to participate in different communicative situations with people from other cultures. |

| Q 04: I seek out information when I get to know a new culture. |

| Q 22: I always want to know about cultures other than my own. |

| P 06: I know my religious, values, and linguistic beliefs when I communicate with people from other cultures. |

| P 42: I value the religious, evaluative and linguistic beliefs that appear during communication. |

| Q 25: I take into account the cultural norms of my recipient when communicating. |

| P 43: All communication has cultural norms. |

| Q 44: I can interpret my recipient’s intent according to their culture. |

| Q 45: I can always understand the dialect of my receiver. |

| Q 10: I always adapt to the linguistic norm of my language. |

| Q 28: I know the linguistic rules of my language. |

| Q 46: I like to respect the linguistic rules of my language. |

| Q 47: I like to maintain eye contact with my listener. |

| Q 11: When I communicate, I make eye contact with my listener. |

| Q 12: I pay attention when people from other cultures talk to me. |

| P 30: I value listening carefully to the receiver in the communicative process. |

| Q 14: I adapt to the cultural aspects of my recipient. |

| P 32: I always have to adapt to the target audience from another culture. |

| Q 50: Adapting to a receiver from another culture is suitable for effective communication. |

| P 33: I think the existence of different cultures enriches people’s worldviews. |

| Q 51: I believe that the cultural expressions of different cultures are not limited to a single territory. |

| Q 16: I’m attentive to responding to the needs of others in conversation. |

| Q 34: I understand the cultural needs of others in the conversation. |

| P 52: In a conversation, it is necessary to understand and respond to the needs of the recipient. |

| Q 53: I always try to be effective when conversing with someone from another culture. |

| P 54: I always manage to adapt to communicative contexts that are foreign to my culture. |

| P 36: It is important to adapt to the linguistic norms of other cultures. |

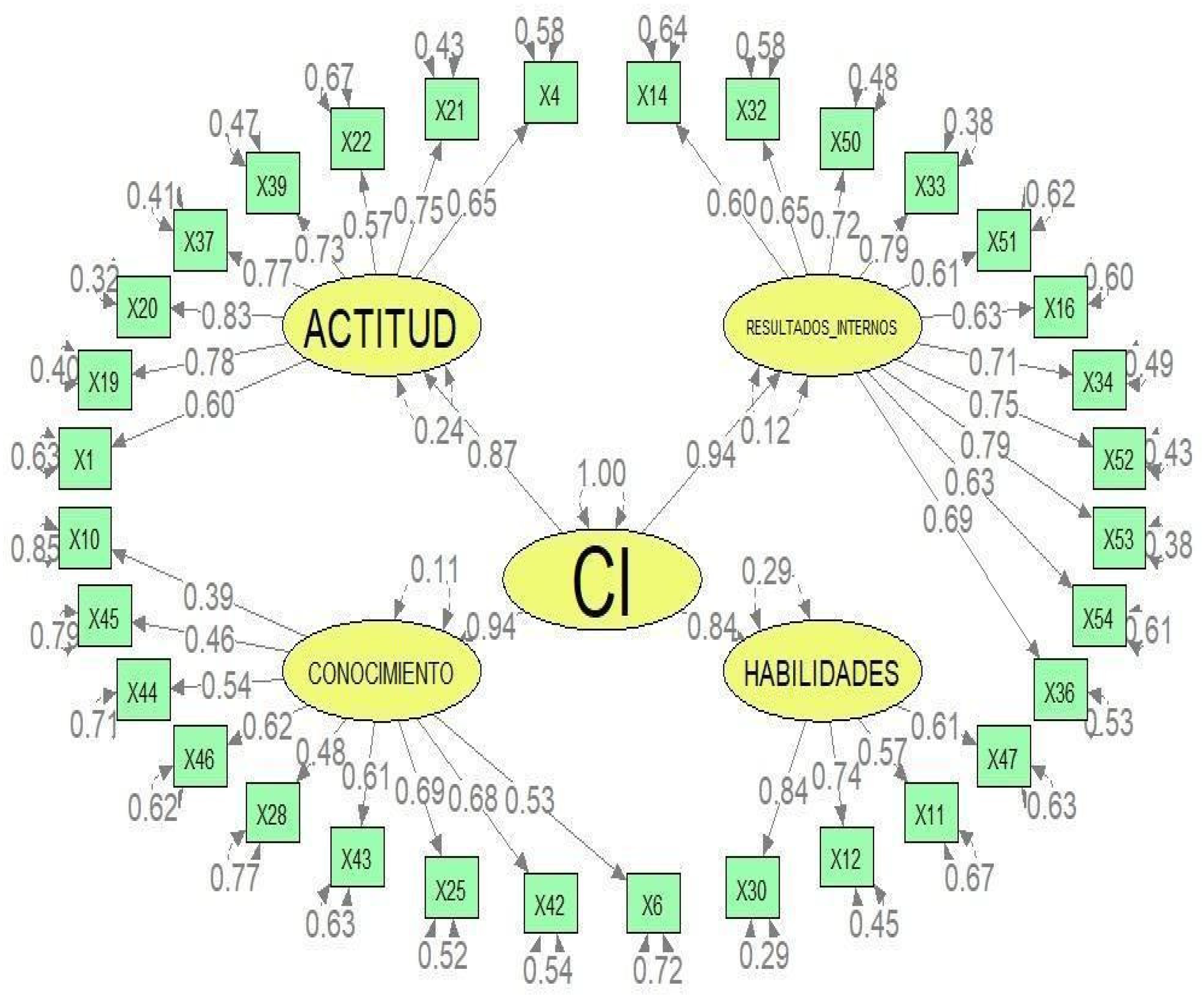

| Dimension | χ2/d.f. | TLI | CFI | RMSEA | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Attitude | 2.9 | 0.99 | 0.98 | 0.029 | 0.51 | 0.89 |

| Knowledge and Understanding | 1.08 | 0.99 | 0.99 | 0.012 | 0.32 | 0.80 |

| Skills | 1.29 | 0.99 | 0.99 | 0.023 | 0.49 | 0.79 |

| Desired Internal Outcomes | 20.13 | 0.93 | 0.94 | 0.050 | 0.47 | 0.91 |

| Instrument IC | 2.34 | 0.98 | 0.98 | 0.051 | 0.81 | 0.94 |

| Proposed model | χ2/d.f. | RMSEA | CFI | TLI | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2.34 | 0.051 | 0.98 | 0.98 | 0.81 | 0.94 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mardones, T.D.C.; Paulet, M.F.; Ortiz, J.E.; Díaz, E.; Romero, M. Instrument to Evaluate Intercultural Competence in Pedagogy Students. Educ. Sci. 2024, 14, 381. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14040381

Mardones TDC, Paulet MF, Ortiz JE, Díaz E, Romero M. Instrument to Evaluate Intercultural Competence in Pedagogy Students. Education Sciences. 2024; 14(4):381. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14040381

Chicago/Turabian StyleMardones, Tricia Del Carmen, Michelle Francois Paulet, Juan Eduardo Ortiz, Elisabet Díaz, and Marcela Romero. 2024. "Instrument to Evaluate Intercultural Competence in Pedagogy Students" Education Sciences 14, no. 4: 381. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14040381

APA StyleMardones, T. D. C., Paulet, M. F., Ortiz, J. E., Díaz, E., & Romero, M. (2024). Instrument to Evaluate Intercultural Competence in Pedagogy Students. Education Sciences, 14(4), 381. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14040381