Abstract

The school-to-work alternance responds to the critical issues linked to the mismatch between school learning and labour market needs, aiming to enhance adolescents’ employability. However, recent studies have shown that in Italy, school-to-work transition pathways are diversified at the territorial level, reflecting regional disparities in opportunities that risk increasing inequalities. In this regard, this paper presents the main evidence emerging from an analysis on multilevel governance of the Pathways for Transversal Skills and Orientation (PCTOs), which are mandatory for Italian students in their last three years of upper secondary schooling. This focus is part of the national research project “Evaluating the School-Work Alternance: a longitudinal study in Italian upper secondary schools”, that aims to evaluate this policy. This part of the study, conducted through semi-structured qualitative interviews at the national, regional, and local level with stakeholders of public institutions, has examined PCTO implementation strategies, pointing out the transition mechanisms between the school and labour market, as well as roles, activities, and way of coordination between public and private sectors. The different perspectives that emerged underline the complexity of establishing networks that relate central and local governance in education systems. The results of the analysis provide a dynamic portrait of the PCTO in Italy, identifying relevant aspects that could enhance future planning or implementation of this policy.

1. Introduction

School-to-work alternance is considered a useful pedagogical approach to promote the development of transversal and technical–professional skills, to improve a proper matching between the scholastic curriculum and labour market demands, and to favour students’ career orientation and employability []. However, recent studies have highlighted that these pathways risk reproducing social inequalities [], also due to the mismatch between the planning of didactic strategies and the skills required by the labour market [,,]; the reproduction of stereotypes derived from social origins as well as by career guidance counsellors []; and, lastly, regional disparities in opportunities [].

Specifically, comparative research has shown that contextual factors within EU regions may influence territorial configurations of school-to-work transitions, potentially exacerbating the challenges faced by low-skilled young people in disadvantaged contexts [], highlighting significant regional inequality across European countries []. Indeed, in certain countries, young people completing their education face difficulties in overcoming barriers to entering the labour market, primarily stemming from their need to acquire the skills and additional competencies demanded by the labour market, often without adequate support []. In this regard, in comparison to other European countries, the Italian school-to-work transition process is notably slow and protracted, due to several factors, including the rigidity and sequential nature of its education system, labour market reforms that have increasingly emphasized flexibility, as well as the social buffering effect provided by the family of origin [].

According to the latest ‘Education at a glance’ report [], Italy is among the five countries where more than one in five VET graduates is NEET. In particular, the report points out that the rate of NEETs aged 15–34 with a technical–professional diploma is 28.1%, significantly higher than the 12% for their peers graduated from a lyceum and well above the OECD average of 15.2%. Similarly, the employment rates of VET graduates one or two years after obtaining their diploma are the lowest in the entire OECD, standing at 55%. These figures indicate that VET pathways in Italy face significant challenges in facilitating the transition of students into the labour market. Thus, several reforms have been developed in recent years to tackle this issue.

In Italy, school-to-work alternance (SWA) pathways, already regulated by Legislative Decree 77/2005, were first reformed by Law 107/2015, the so-called ‘Buona Scuola’, which made them compulsory for students in the last three years of upper secondary schooling, and, subsequently, by Law 145/2018, which, in Article 1, paragraphs 784–787, redefined them as Pathways for Transversal Skills and Orientation (PCTOs). Moreover, the latter law reshaped both their overall minimum duration and the resources allocated to each school, through the publication of specific Guidelines with Decree No. 774/2019 by the Ministry of Education, University, and Research. In particular, the Guidelines have assigned priority to the acquisition of transversal skills, emphasizing the orientation value of the pathways [].

SWA’s introduction in Italy should also be considered in the broader perspective of the validation of non-formal and informal learning to formal education, as outlined by Article 4 of Law 92/2012 and Legislative Decree 13/2013, which align with corresponding European directives [,]. These regulations were supposed to assign the same value to learning acquired through diverse contexts and modalities, enabling schools (in the case of SWA) to recognize non-formal and informal learning within their formal pathways, while allowing the labour market to test the practical applicability of acquired knowledge (e.g., integrating transversal skills with disciplinary ones). However, in this context, it should be considered that the different actors involved in SWA implementation seem to have partially different objectives, or they seem to interpret the orientation objective of the tool in different ways. In fact, on the one hand, schools often perceive it as a means of bringing students to the labour market by potentially creating employment opportunities (in technical and professional schools) or as a form of orientation for selecting university programs (in lyceums). On the other hand, hosting organizations are not always motivated by an orientation and transversal skill acquisition objective, but rather by visibility goals as potential employers or tertiary education providers for students.

Hence, achieving the objectives of PCTOs proves to be challenging due to the plurality of stakeholders involved in their design and implementation, both within schools and hosting organizations. This challenge is further compounded by the varying perspectives held by actors within these structures regarding the pathways, as well as the diverse coordination modalities that occur in different local contexts. What, then, are the primary governance challenges influencing the effectiveness of PCTOs in facilitating the school-to-work transition in Italy, and how do these challenges differ across regions, stakeholders, and institutional perspectives?

Therefore, the national research project ‘Evaluating the School-Work Alternance: a longitudinal study in Italian upper secondary schools’, coordinated by INVALSI in collaboration with University of Genoa, Sapienza-University of Rome, and University of Milan Bicocca, was funded by MUR (The Ministry of University and Research). In this regard, this contribution aims to present the main evidence that emerged from qualitative research that has analysed the governance mechanisms of the PCTOs, investigating their functioning in terms of process and outcomes, while delineating critical elements and strengths. Additionally, it explores how the various actors involved in the system interact with each other, negotiating choices on the design and implementation of the pathways. Specifically, Section 2 discusses the multilevel governance of education systems, to identify the models underlying the research; Section 3 outlines the methodological strategy adopted in the empirical analysis; Section 4 presents the main findings of this study; Section 5 discusses the results of the analysis in relation to the theoretical framework outlined; Section 6 provides concluding remarks, exploring potential policy developments and further recommendations.

2. Governance of Education Systems: Hierarchy, Market, and Network Models

The term governance is used in many social science disciplines as an interdisciplinary “bridging concept” [] (p. 373), thus linking the various academic discussions on forms of collective decision making and implementation in Political, Legal, and Administrative Sciences, in Sociology, and in Educational Sciences. Usually, the term governance refers to cases in which a decision-making and implementation field is managed by several actors, not bound by a hierarchical constraint, or belonging to a single structure, who nevertheless have to or want to cooperate in order to achieve common objectives. It was used extensively in the field of welfare when, towards the end of the 1970s, the illusion that the public sector could directly provide answers to citizens’ needs disappeared and the awareness emerged that public, private, and third-sector organizations’ efforts needed to converge in order to provide such answers []. As Jessop [] observes, governance can be characterized as a response to the failure of state and market forms of welfare planning; particularly, in the educational field, we can consider governance “as a specific form of coordination of social actions characterized by institutionalized, binding regulations and enduring patterns of interaction” [] (p. 2). In the case of PCTOs, as will be discussed, the degree of institutionalization of the links between the various actors, the norms that regulate their actions, and the durability of reciprocal interactions turn out to be essential for good governance, as they produce mutual trust between the various actors, an essential prerequisite for the effectiveness of their actions.

There is not a consensual definition of the term governance. It is not a theory in the narrow sense of the term, rather an analytic perspective leading to shift the approach in the political field from an actor-centred point of view to an institution-centred one [], focusing on the analysis of the interplay among the various stakeholders, sectors, and levels involved in non-hierarchical and network-like structures []. The term ‘governance’ is used in the description of new forms of steering/regulation, addressing ‘government’, ‘management’, ‘coordination’, ‘regulation’, etc., among different agents within the state, the market, the economy, and civil society []. According to Marsh [] (p. 43), it “is a process by which the state shapes both the particular form that hierarchy, networks or markets, as modes of governance, take on within a policy area/political process, and the way in which each form articulates with other forms of governance”.

Governance Studies have elaborated several analytical categories that are very useful in understanding contemporary patterns of coordination of action [], as well as in the educational domain [,,]. Among the central categories, the following four may be distinguished:

- Actors and actor constellations, distinguishing between individual (e.g., teachers, students, parents, policymakers) and organized (collective and corporative) actors. The unit of analysis is the actor constellation: i.e., the interaction of actors. It is also important to recognize that specific actor constellations influence the expectations and options for the action of single actors.

- Interdependence of actors, i.e., their mutual dependencies that, in modern societies, are embedded in legal, organizational, and cultural conditions. The specific forms that interdependence of actors assumes depend—in addition to the normative regulations—on the resources available to each actor, partly defining its opportunities for action.

- Multilevel systems, pointing out that education governance has to be considered as a complex social system, and as such as a multilevel phenomenon. It is certain that not all actors interact with all other actors in the same way, but there are typical constellations of actors, typical ‘levels’ with particular modes of action, which may be very different from the logic of action of another level. We may discern formal levels—at the macro, meso, and micro level—as the starting point of the analysis [,].

- Basic mechanisms and modes of governance differ according to the levels of analysis taken into consideration. At the micro level, there are constellations of observation, influence, negotiation. In constellations of observation, the coordination of social action is achieved by unilateral or mutual adaptation based on the observation of the others’ action. In constellations of influence, coordination is achieved by targeted use of means of potential influence, such as power, money, knowledge, emotions, moral authority, etc., in order to induce the coordination of social action. In constellations of negotiation, social coordination is based on the elaboration of bilateral arrangements, which can display their binding effects even without exercising power, whereas ‘observation’ and ‘influence’ are the preconditions for ‘negotiation’ []. At the macro level, the different basic mechanisms or models of governance as constellations of action coordination are hierarchy, markets, networks [].

In this paper, the focus will be on hierarchy, markets, and network educational system governance models [,]. Hierarchy refers to the formal authority exercised by the State, including through statutory policies and guidance; national, regional, and local bureaucracies; and the direct performance management of services and interventions. Markets are based on incentives and (de)regulation, aimed at encouraging choice, competition, accountability, and commercialization. Networks refer to the (re)creation of interdependencies that support and/or coerce inter-organizational collaboration, partnerships, and participation. Each of these coordinating mechanisms is seen as having both strengths and limitations [,]. Hierarchy enables control by using formal authority as a means of coordination but can weaken collaboration and lateral innovation. Markets rely on monetary incentives to co-ordinate supply and demand and promote flexibility but can put at risk trust and undermine relations that support knowledge sharing and equity. They also suffer from information asymmetries that characterize the relationships between the different actors and the different starting positions. Networks co-ordinate on the basis of trust and promote shared knowledge generation but can become dysfunctional when allowing complacency or exclusivity on the basis of familiarity.

Analysing the ways in which hierarchy, markets, and networks intersect to influence decisions and behaviours across different local contexts is thus challenging and depends on a complex array of factors. Among others identified in the literature, the following are worth mentioning []: the history of local relationships between schools and local authorities, as well as the alliances, consensus, and conflicts that have shaped local schooling; the context of individual schools and where and how they are situated socially, economically, and geographically; and the agency of local actors, including their capacity to act and be informed, and how the latter are influenced by personal and professional values.

According to the different levels of governance involved in the coordination of activities, the main critical issue remains to identify the extent to which the decentralization process—increasingly widespread in the educational sector [,], in which individual schools have considerable autonomy, although not always fully utilized—represents an opportunity []. In particular, it is questioned whether it is a chance for collaborative and democratic policy and decision making at the local and regional level or, alternatively, whether it implies reduced state intervention that leaves further room for privatization, market efficiency, deregulation, and exclusion, with the risk of increasing social inequalities with regard to accessing education [,]. This paper focuses on the relationship between hosting organizations (public, private, and third-sector organizations) and the education and training system, in order to investigate the governance of PCTOs by examining the ways in which the different actors of the two systems interact and how they coordinate.

3. Materials and Methods

The aim of the contribution is therefore to describe and understand the governance of PCTOs, identifying national, regional, and local actors involved. In order to delineate the governance systems of the pathways, the analysis will focus primarily on the following aspects and research questions:

- (1)

- Identifying the main actors and institutions involved in the governance and the activities in which they are involved. Which are these actors and institutions at national, regional, and local levels? Which are their roles?

- (2)

- Identifying and understanding the levels and mechanisms of coordination among these actors in pursuit of their activities. Which are the relationships between the local, regional, and national authorities concerning the governance of PCTOs? How do actors and institutions coordinate their activities? Which mechanisms do they use?

- (3)

- Exploring the PCTOs’ objectives. How do different stakeholders evaluate and perceive the objectives set for the pathways? To what extent are these objectives interpreted similarly or complementarily by different actors, thus influencing their actions and relationships?

The in-depth examination of the PCTO governance mechanisms was carried out by conducting 54 interviews. In detail, the following actors were interviewed: School Principals (7); school referent teachers for PCTOs (7); classroom referent teachers for PCTOs (8); a referent from the regional administration; 15 PCTO referents from Regional Scholastic Offices (USR) and Territorial Ambit Offices (UAT) from 9 regions (Campania, Emilia-Romagna, Liguria, Lombardy, Piedmont, Sardinia, Sicily, Tuscany, and Veneto); 14 referents from Chambers of Commerce (CCIAAs) and employers’ associations from 13 regions (Abruzzo, Calabria, Campania, Emilia-Romagna, Lazio, Liguria, Lombardy, Piedmont, Apulia, Sardinia, Sicily, Tuscany, and Veneto); a national head of employers’ associations; and an expert from the academic field. Each interviewee was provided with an Information form and asked to sign a consent form, ensuring anonymity, confidentiality, and data protection. This aimed to grasp how actors within the system coordinate across various levels to make decisions regarding the planning, design, implementation, and evaluation of these pathways. Specifically, at the micro level, an exploratory study was conducted in the metropolitan areas of Genoa and Milan [], involving education system actors, considering the different types of schools (technical, professional, and lyceum). Meanwhile, at the meso and macro levels, the analysis was extended to decision makers and experts at the regional and national levels. The selection of interviewees and the definition of the interview schedule were extensively discussed both within the research team, which has long been engaged in studies on the topic, and with stakeholders in the field at the local level. Furthermore, valuable insights were obtained from other research units participating in the project, which investigated different aspects of PCTOs by involving actors such as schools’ and hosting organizations’ tutors, students, etc.

The interviews were carried out b”twee’ February 2020 and March 2023. The time gap between the first and last interviews is due to the COVID-19 pandemic emergency, which created specific challenges for the education system and particularly for the implementation of PCTOs. Indeed, moving to remote learning during the pandemic, interviewing key informants on the topic of school-to-work alternance would have exposed them to bias. Due to these external factors, we therefore postponed the interviews until the resumption of PCTO activities. They were conducted online with the participants’ consent. Each interview was recorded, and the complete text was transcribed afterward. The interview transcripts were evaluated using a qualitative content analysis approach []. This involved coding and identifying the categories and themes that emerged from the interviews. Subsequently, the coding framework was thoroughly reviewed to analyse and interpret the findings. Finally, the results were returned within an interpretive and analytical framework [], as presented below.

4. Results

4.1. Exploring Multilevel Governance of PCTOs: Mapping Actors and Roles

The governance of PCTOs involves the intervention, at different levels, of multiple actors representing the various organizations and institutions involved in their design, management, and implementation.

In this regard, the analysis initially focused on mapping the actors within the system, with the aim of delineating their roles and any shortcomings identified by the interviewees, specifically focusing on the functions and activities attributed to the various actors involved in the governance of PCTOs (Table 1).

Table 1.

Role of relevant actors in PCTOs.

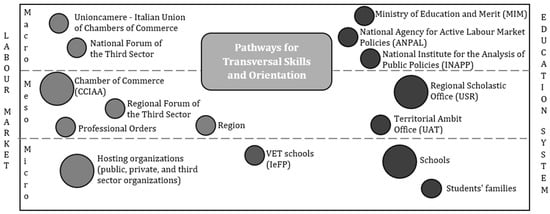

The analysis of the main actors involved in the governance of PCTOs revealed significant differences, in particular, highlighting a school–labour-market polarization (Figure 1) between the perspectives of the Regional Scholastic Offices’ representatives and those of Chambers of Commerce and employers’ associations. Moreover, variations were observed among key informants within the same category but situated in different territorial contexts.

Figure 1.

Actors and institutions involved in PCTO design, management, and implementation. Source: Authors’ own elaboration.

Firstly, focusing on the Regional Scholastic Offices, a tendentially ‘school-centric’ perspective emerges, which assigns more centrality in governance to the role of the MIM, USR, UAT, schools, School Principals, disciplinary departments, class councils, teachers, school tutors, students, and families than that assigned to Chambers of Commerce, Trade Union Organizations, firms, and tutors of hosting organizations.

Within this macro-trend, notable disparities emerge across regional contexts regarding the primary level of governance. In fact, some of the interviewees assign a leading role to the macro decision-making level, hence to the Ministry of Education and Merit, which, through its Guidelines, establishes the framework for PCTO initiatives. However, it should be emphasized that in some cases, this assertion seems to be almost a ‘ritual’, driven by adherence to norms, only to be contradicted by subsequent reflections of interviewees. On the one hand, they recognize that de facto governance occurs at the meso or even micro level, while on the other hand, they highlight significant oversights at the macro level, perceived as a thinly veiled lack of interest in coordinating PCTO governance effectively.

“If you ask me if there is a management in charge, it doesn’t appear to me that there is one”(USR Piedmont)

As previously mentioned, some USRs identify the focus of governance at the meso level, assigning themselves a central role in “the possibility of creating a constellation of networks” (USR Liguria). On the one hand, this entails facilitating connection and coordination between the macro and micro levels on the educational side, thus as a trait d’union between the Ministry and schools, explicating in some cases the role of the Territorial Ambit Offices. On the other hand, regarding the mediation between schools and hosting organizations, it explicates in many cases the role as interlocutor of the Chambers of Commerce and other employers’ associations in the different economic sectors, both in the stipulation of protocols of understanding and in the design and experimentation of innovative paths.

Finally, other USRs shift the focus of governance to the micro level, attributing a leading role, in some cases, to institutions and School Principals, when with the concept of governance they refer primarily to the establishment and maintenance of relationships with local stakeholders and, in other cases, to disciplinary departments, class councils, teachers, and school and hosting organization tutors, and when with the concept of governance they associate mainly the design, implementation, and evaluation of PCTOs. Only in a single case is the concept of multilevel governance explicitly mentioned, although the set of responses then seems to focus primarily on the micro level.

As for the Chambers of Commerce and Trade Unions interviewed, a generally more ‘balanced’ perspective on the governance of PCTOs emerges. These actors perceive—at the micro level—schools and firms as equally key players within the pathways. While at the meso level, they equate the roles played by the Chambers of Commerce and USRs to mediators of relations with the labour market and school representatives and actors with functions of coordination at the territorial level, facilitating the match between ‘demand and supply of PCTO’; of signing protocols of understanding; of proposing pathways including experimental ones; of supporting their design, implementation, and evaluation; and of disseminating best practices through IT platforms. Thus, once again, the “lack of a unitary strategy” (Avellino Chamber of Commerce) in pathways emerges on the macro (ministerial) level.

4.2. The Coordination Arrangements between Schools, Hosting Organizations, and Local Authorities: Challenges and Perspectives

The analysis of the interviews reveals the importance of formalized coordination among the various actors engaged in the governance of PCTOs and how all stakeholders recognize its importance in shaping coherent pathways aligned with ministerial directives. However, coordination arrangements currently exhibit notable heterogeneity across different territories, with variations even within the same region being evident.

“There are roundtables where certain issues are discussed. However, due to the singularity of each territory, they should be considered separately, within their respective contexts”(USR Sicily)

In cases where the design and management of PCTOs are established as the result of shared strategies among various local actors, positive effects emerge: “With the region and various institutions, there are scientific technical committees managing the design, monitoring, and evaluation of the pathways. (…) I believe it’s crucial that every school PCTO referent has the opportunity to communicate with a regional referent” (USR Veneto). However, respondents often express that they do not recognize a formalized coordination structure in their territory regarding PCTO governance:

“Right now, I have the impression that there is no coordination in our territory”(Assolombarda Milan)

“Coordination is a term we’re unfamiliar with. There is no coordination. It simply doesn’t exist”(USR Sardinia)

In this scenario of “total spontaneity” (Genoa Chamber of Commerce) in which “everyone organizes as best they can” (Avellino Chamber of Commerce), it appears to be challenging to identify an authority capable of coordinating the actions implemented by individual actors. Each organization, based on its own resources and requirements, appears to independently activate useful actions to respond to the need of managing PCTOs in a shared form. This suggests that an individual initiative constitutes a discriminating factor in ensuring a truly effective design and monitoring of the pathways.

“It would require at least provincial coordination among all the provincial institutes, also to exchange experiences and design common strategies”(Avellino Chamber of Commerce)

In this context, some USR representatives share successful strategies that they have autonomously activated, which have facilitated the connection between schools and hosting organizations and monitoring the outcomes of the initiatives promoted. For instance, certain USRs have signed specific protocols with local institutions, such as the Chamber of Commerce and Unione Industriali (Employers’ Association), aimed at promoting additional agreements between various schools and firms.

In some territories, the connection between educational institutions and host structures facilitated by USR is not particularly critical and assumes the form of support provided to individual schools as specific needs arise:

“Now that a mechanism has been established […], the coordination is really a support […] because I have a relationship with individual tutors and maybe one school needs one thing more than another. […] We have become part of a family system”(UAT Ferrara)

In these cases, individual schools often rely on long-standing privileged relationships with firms and employers located in the territory, for selecting hosting organizations and developing training opportunities accordingly. Typically, schools gradually build networks with locally available company supply chains, which evolve based on the training needs identified by participating students in PCTOs. In such cases, the intermediary role in the networking process between schools and firms, carried out, for example, by Chambers of Commerce or USRs, is not considered essential since the collaboration among the various actors is already well established. Examples of coordination roundtables for pathways organized by individual schools can be observed in this context, starting with the agreements signed with different institutions.

“These are individual relationships that the school has with certain entities, established over a long period […]. Generally, we provide information regarding local institutions, but by now, schools are already aware of this!”(UAT Ferrara)

Similarly, Chambers of Commerce describe virtuous actions independently promoted to bridge the gap resulting from the lack of specific coordination on PCTOs, carried out by a formalized group at the local level to facilitate connections between schools and firms. These actions take various forms over time: from co-designing courses for pathways offered to school and hosting organizations’ tutors, to offering vouchers to firms to encourage them to host students, to the promotion of territorial roundtables that serve as connectors for the different initiatives activated in the same area.

“The Chamber of Commerce has endeavoured to facilitate knowledge exchange between schools and firms and the implementation of pathways by bringing together teachers and hosting organization tutors at the same table to guide them in designing a PCTO and understand their respective positions”(Cagliari Chamber of Commerce)

In some instances, the Chambers of Commerce have implemented specific online tools to facilitate connections among the various actors involved in the governance of PCTOs. Such is the case of “online meetings that allow stakeholders to exchange and dialogue through web platforms” (Cagliari Chamber of Commerce) or that of digital platforms “where different actors in the territory can subscribe and subsequently share content” (Venice and Rovigo Chambers of Commerce) for the purpose of sharing the projects carried out.

The absence of a formalized coordinating group capable of supervising and promoting PCTOs’ governance according to well-defined strategies in different territories is attributed by some interviewees to the lack of a national-level system direction. Such a direction could support organizations in promoting opportunities for comparison and discussion at the local level.

“It is evident that at the local level, there is a need to strengthen central direction, opportunities for coordination, reciprocity of functions, and exchange between firms and schools. However, on the other hand, support from the Ministry is fundamental”(USR Liguria)

Some interviewees express the desire for the national system management to allocate specific roles and functions related to PCTOs to the various actors involved. They assume that at the territorial level, Chambers of Commerce and Regional Scholastic Offices lack sufficient authority and autonomy to raise awareness of the importance and function of PCTOs among educational and host institutions.

Further critical issues, regarding the possibility of establishing a more formalized coordination structure in certain territories, appear to be related to the limited time and human resources available and the difficulty of enabling the committees established to be truly operational and effective in addressing the difficulties that gradually arise in the design and management of PCTOs.

“The pathways […] would at least require adequate resources to implement them practically”(Venice and Rovigo Chambers of Commerce)

Some interviewees highlight the challenge of actively involving schools and firms without offering them a tangible return (e.g., an economic contribution for hosting organizations). However, stakeholders demonstrate awareness and understanding of the many difficulties faced by local firms and express willingness and readiness to provide them with support.

4.3. Aims and Objectives of PCTOs

The coordination modalities among governance actors and the networks developed at the territorial level, as well as in relation to the socioeconomic context, affect the achievement of pathway objectives.

Three main objectives attributed to PCTOs emerge from the interviews: to enhance students’ career orientation skills; to acquire/develop students’ transversal skills; and to foster a stronger connection between the school system and the labour market. These three objectives, which basically reflect the ‘official’ and explicit goals of the policy that introduced PCTOs in all upper secondary school pathways, emerge transversally from the interviews conducted, both with respect to the territorial dimension, the type of stakeholders, and the different types of schools involved (lyceum, technical, and professional).

Regarding the first objective, the analysis reveals an initial difference across various education and training pathways: in lyceums, PCTOs primarily serve an orientation function aimed at fostering “a more informed ability to make choices for the students’ educational pathway, for post-graduate choices” (teacher responsible for PCTO—Lyceum Genoa), while in technical and professional schools, a specifically professionalizing function prevails, in order to promote a “possible future career pathway” (teacher responsible for PCTO—Lyceum Genoa).

Across different types of institutes, the potential of PCTO experiences in facilitating what is defined as a ‘re-orientation’ of students emerges as a common characteristic: “direct experience exposes them to a potential career orientation. It has often occurred that some students have returned from the experience and said: ‘I now realize that I don’t want to pursue that career’” (teacher responsible of PCTO—Technical Institute Milan).

This involves the ‘abandonment’ of training and/or vocational projects that experience ‘in the field’ has revealed to be unsuitable with regard to students’ capabilities/attitudes or disconnected from an idealized ‘professional imaginary’. It also includes the possibility of discovering new paths that had not been previously considered, and which may instead align with students’ interests and expectations.

“Students have their choice validated or are productively reorientated […]; these pathways have a very strong orientation value whether they confirm or not the student’s choice. This value arises not only because he or she has read it in a book, but more importantly because the student has experienced it directly”(USR Liguria)

A second objective of the PCTOs involves the acquisition and development of transversal skills, which are differentially designated by the interviewees in the terms of “self-awareness, understanding their attitudes and orienting themselves in the world” (USR Lombardy), developing “autonomy in time management, respecting rules different from those established at home or at school, collaborating in a group, and being part of a team” (School Principal, Technical Institute—Genoa), “adapting potential for a new context, developing resilience” (School Principal, Lyceum—Milan). Interviewees’ narratives refer to the potential validation of transversal skills already ‘tested’ in schools, the acquisition of transversal skills never or poorly applied in the educational setting, or the acquisition of awareness regarding one’s own transversal skill deficit.

The third objective of PCTOs is to facilitate the school-to-work transition by bridging the gap between these two systems and the match/mismatch between the skills acquired by students in school and the needs required by tertiary education and the labour market. Two main issues emerged in this regard. The first relates to how PCTOs allow students to be more motivated in their studies: “when students return from their experience in the firms, they recognized and validated what the teacher had previously taught them previously in school because they find some correspondence with the reality they experienced” (USR Lombardy). The second concerns the connection between the school and the economic system, particularly evident in interviews with representatives of the Regional Scholastic Offices, and pertains to the role of PCTOs in fostering the establishment and/or development of a “bridging” system by providing “opportunities for the school and entrepreneurial sectors to interact” (USR Liguria). This aspect is perceived positively by both schools and the labour market; PCTOs facilitate “establishing relationships […], re-evaluating and re-qualifying the role of the school” (USR Liguria) in the community, while also enabling firms/institutions to gain a better understanding of the social context, including needs and “other realities existing in the same territory” (USR Lombardy).

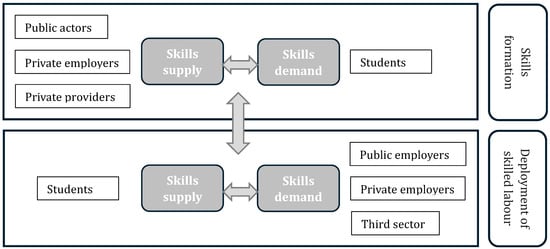

In the context of PCTOs, the skill system (Figure 2), articulated between skill formation and the deployment of skilled labour, is based on the interaction between the demand and supply of skills [,]. This interaction plays a key role in determining the success of pathways, with a specific focus on the differentiation between high schools and technical–professional schools, while examining regional disparities and different governance frameworks.

Figure 2.

Skill system—skill formation and deployment of skilled labour. Source: Authors’ own elaboration based on Green (2013) [] and Capsada-Munsech and Valiente (2021) [].

In terms of skill formation, both public actors (such as public educational institutions) and private providers (such as private training entities) have significant influence within PCTOs. They are responsible for designing curricula, integrating practical experiences, and providing skills in line with labour market needs. Meanwhile, students serve as key drivers of skill demand, actively seeking pathways that align with their career aspirations and the requirements of the labour market. Their individual preferences, interests, and future ambitions shape the types of skills they aim to acquire through PCTOs.

On the other hand, the deployment of skilled labour involves students transitioning into potential contributors to the labour market. Their level of qualification and acquisition of specific skills determines their employability. Concurrently, employers, whether public or private, alongside third-sector organizations, are responsible for driving the demand for skilled labour. They actively seek individuals with the skills needed to fulfil organizational objectives and contribute effectively to the workforce.

Within this model, effective governance structures are indispensable for managing the (mis)match between skill supply and demand. Regional disparities in skill supply and demand therefore necessitate tailored approaches to governance that can address variations in policy networks and institutional orientations as well as differing objectives between technical–professional schools and lyceums, which further impact the effectiveness of skill development interventions.

5. Discussion

The analysis of the interviews revealed the heterogeneous nature of the governance of PCTOs, particularly concerning the roles played by different actors involved. It also highlighted the existence of varied realities at the territorial level, with disparities in the productive system and in the relationships between different institutions and stakeholders (excellent with some, and unsatisfactory with others).

Considering the different governance models of the educational systems outlined in the theoretical framework [,], it can be argued that the ‘hierarchical component’ appears to be weak for the various actors interviewed. This weakness implies that the MIM and business representative organizations at the national level have limited capacity to provide directions and models at the meso and micro levels, especially concerning the public sector component. The mapping of the different actors revealed a lack of system direction and structured Guidelines at the macro level, effectively relegating the reins of governance to the meso and micro levels. The absence of a unified strategy for coordinating among stakeholders is also highlighted as a major challenge in the governance system of PCTOs. This poses a risk of reducing pathways to mere bureaucratic fulfilment rather than effectively matching demand and supply, particularly in terms of skill formation [], delegating, without local support networks, to the spontaneity of single schools the success of the PCTOs. Furthermore, regarding the hierarchical dimension, the heterogeneous capacity to integrate transversal skills into traditional teaching activities indicates the limitations of the central level (from the USR to School Principals) to innovate didactic methodologies through PCTOs, which are very often experienced as separate episodes from classroom activities.

In the most favourable contexts, in response to the latency of system direction at the macro level and the mismatch in school-to-work transition [], a ‘network model’ of governance intervenes, activated at the local level by leveraging previously established territorial networks between educational institutions and hosting organizations. Explaining the strengths of the PCTO governance system, the interviewees strongly highlighted those contexts in which there are motivated schools in the territory that believe in PCTOs, that have had previous experiences of school-to-work transition [,], and that are able to ‘dialogue’ with firms, with positive impacts on both the school and economic systems []. The ‘network component’ always appears to be decisive, particularly in cases where there are no favourable conditions for offering ‘positions’ in which to implement PCTOs, because in these cases, the ability of networks of schools or individual institutes to promote local networks of actors appears to be crucial.

In an overall analysis of the factors that most affect critical issues and strengths, the majority of respondents emphasized the importance of the socioeconomic context, which plays a key role in providing or precluding opportunities for pathway implementation. Disparities in territorial networks and socioeconomic contexts also influence the achievement of the objectives that PCTOs pursue. The analysis of the interviews revealed that the purposes of the pathways are significantly oriented towards career orientation and the acquisition of transversal skills for lyceums, while they focus on the acquisition of occupational skills for technical–professional institutes. In this regard, at the meso and micro level, we can refer to a ‘market component’ of governance, which responds to skill demand–supply structures [,] and influences the very structuring of the pathways. This governance model is predominantly observed in technical and professional schools operating in socioeconomically dynamic contexts, since the incentive to design training pathways and anticipate occupational outcomes operates both at the level of the institute and, presumably, at the level of the students and families.

Despite the research’s limitations, stemming from its reliance on a qualitative study with limited generalizability, this article provides a valuable understanding of PCTO governance in Italy. This comprehension will integrate the outcomes of forthcoming quantitative analyses conducted by other research units as part of the nationwide project, providing varied perspectives to grasp the complexity of PCTOs.

6. Conclusions

The research project of which this study is a part has as its main objective the evaluation of PCTOs as a didactic methodology for the professional training and career orientation of students in their development, taking into account the point of view of the involved actors and stakeholders.

Considering the limited number of studies conducted on the effects of school-to-work alternance in Italy, this article aims at contributing to the debate on the topic by outlining the governance systems of PCTOs and how they function in terms of processes and outcomes.

The objectives envisaged by the PCTOs are complex to achieve due to the plurality of stakeholders involved in their design and implementation, both internal and external to the schools, and due to the lack of a well-structured governance model at the macro level, which ends up delegating to the meso and micro level, where effective networks can be developed at the territorial level, alongside the achievement of the goals set within the pathways. It should be further emphasized that the aims of orientation and the development of transversal skills do only strongly differentiate between lyceums and technical and professional institutes but are also considered relatively autonomous with regard to teaching activities, as if they could be acquired ‘separately’ from schools, whose didactic model would therefore not be modified except marginally by these pathways. This is a crucial aspect, also considering the increased emphasis on the didactic dimension that occurred with the transition from SWA to PCTO, which will be analysed in detail by shedding light on the results of the school surveys conducted by other research units.

The lack of strong centralized governance is reflected in the different coordination models implemented at regional and local levels. In fact, the analysis showed how, at the local level, the central role of schools and their inclusion in networks, both of schools and of local actors, prevails over the dynamism of the context. Meaning that, even in relatively weak socioeconomic contexts, schools can ‘make a difference’, while contexts with a dynamic economic structure can favour the PCTOs in technical and professional institutes through networks already established before their introduction but cannot ‘push’ schools to practice them effectively. Moreover, the key role in the governance of the PCTOs seems to remain within the school system (Ministry/USR/schools) that supports the networks or, in the absence of networks, plays a proactive role by trying to foster, at the micro level, the participation of actors such as students’ parents or individual firms. The encouraging role of the Chambers of Commerce or Trade Unions, in specific cases, does not appear to be negligible and seems able to counteract a certain inertia of the educational system.

The analysis thus revealed how the connections between the micro, meso, and macro level, within the governance of PCTOs, are not systematized but are implemented differently according to both the resources available within the networks and the relationships established at the territorial level. This underscores both challenges and opportunities for enhancing the effectiveness of these programs. Considering potential policy developments and further recommendations is essential to improve PCTOs and ensure they fulfil their objectives of preparing students for the transition to the labour market. In conclusion, effective governance of skill supply and demand within PCTOs requires a profound understanding of regional contexts, policy orientations, and stakeholder dynamics. Addressing regional disparities, fostering collaboration among stakeholders, and prioritizing coherence in policy frameworks are essential steps to equip young people with the skills needed to thrive in the ever-evolving labour market.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: M.P. and V.P. (paragraphs 1 and 2); Materials and Methods: P.G. and C.T. (paragraph 3); Results: C.T. (paragraph 4.1), P.G. (paragraph 4.2) and V.P. (paragraph 4.3); Discussion: M.P. and C.T. (paragraph 5); Conclusions: M.P. and C.T. (paragraph 6). Investigation, P.G., V.P. and C.T.; Data Curation, P.G. and V.P.; Writing—Original Draft Preparation, P.G. and V.P.; Writing—Review and Editing, M.P. and C.T.; Supervision, M.P. and C.T.; Project Administration, C.T.; Funding Acquisition, M.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Ministry of University Education and Research, grant number 20173SNL9B.

Institutional Review Board Statement

IRB approval is not required because the surveys planned by the Genoa research unit were deemed not to necessitate specific approvals by the University’s Ethics Committee.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Costa, V. Circolo ermeneutico, ibridazione scuola-lavoro e lifelong learning. Un approccio fenomenologico. Form. Pers. Soc. 2016, 6, 16–25. [Google Scholar]

- Pinna, G.; Pitzalis, M. Tra scuola e lavoro. L’implementazione dell’Alternanza Scuola Lavoro tra diseguaglianze scolastiche e sociali. Sc. Democr. 2020, 11, 17–35. [Google Scholar]

- Valiente, O.; Capsada-Munsech, Q. Regional governance of skill supply and demand: Implications for youth transitions. In Governance Revisited: Challenges and Opportunities for Vocational Education and Training; Bürgi, R., Gonon, P., Eds.; Series: Studies in Vocational and Continuing Education 20; Peter Lang: Bern, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 303–330. [Google Scholar]

- Scandurra, R.; Calero, J. How adult skills are configured? Int. J. Educ. Res. 2020, 99, 101441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, F. Skills and Skilled Work. An Economic and Social Analysis; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Romito, M. Una Scuola di Classe. Orientamento e Disuguaglianza Nelle Transizioni Scolastiche; Guerini: Milano, Italy, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Scandurra, R.; Cefalo, R.; Kazepov, Y. School to work outcomes during the Great Recession, is the regional scale relevant for young people’s life chances? J. Youth Stud. 2021, 24, 441–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cefalo, R.; Scandurra, R.; Kazepov, Y. Territorial Configurations of School-To-Work Outcomes in Europe. Politics Gov. 2024, 12, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iammarino, S.; Rodriguez-Pose, A.; Storper, M. Regional inequality in Europe: Evidence, theory and policy implications. J. Econ. Geogr. 2019, 19, 273–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caroleo, F.E.; Rocca, A.; Neagu, G.; Keranova, D. NEETs and the Process of Transition from School to the Labor Market: A Comparative Analysis of Italy, Romania, and Bulgaria. Youth Soc. 2022, 54 (Suppl. 2), 109S–129S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pastore, F.; Quintano, C.; Rocca, A. The duration of the school-to-work transition in Italy and in other European countries: A flexible baseline hazard interpretation. Int. J. Manpow. 2022, 43, 1579–1600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. Education at a Glance; OECD: Paris, France, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- MIUR (Ministero dell’Istruzione, dell’Università e della Ricerca). Percorsi per Le Competenze Trasversali e per L’Orientamento. Linee Guida; Ministero dell’Istruzione, dell’Università e della Ricerca Dipartimento per il Sistema Educativo di Istruzione e Formazione Direzione Generale per gli Ordinamenti Scolastici e la Valutazione del Sistema Nazionale di Istruzione. 2019. Available online: https://www.miur.gov.it/documents/20182/1306025/Linee+guida+PCTO+con+allegati.pdf/ (accessed on 20 November 2023).

- Council of the European Union. Council recommendation of 20 December 2012 on the validation of non-formal and informal learning. Off. J. Eur. Union 2012, 398, 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- European Parliament. Recommendation of the European Parliament and of the Council of 23 April 2008 on the establishment of the European Qualifications Framework for lifelong learning. Off. J. Eur. Union 2008, 111/1, 6.5, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Schuppert, G.F. Governance im Spiegel der Wissenschaftsdisziplinen. In Governance-Forschung. Vergewisserung über Stand und Entwicklungslinien, 2nd ed.; Schuppert, G.F., Ed.; Nomos: Baden Baden, Germany, 2006; pp. 371–469. [Google Scholar]

- Burns, T.; Köster, F. (Eds.) Governing Education in a Complex World; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Jessop, B. The Dynamics of Partnership and Governance Failure. In The New Politics of British Local Governance; Stoker, G., Ed.; Macmillan: Basingstoke, UK, 2000; pp. 11–32. [Google Scholar]

- Windzio, M.; Sackmann, R.; Martens, K. Types of Governance in Education: A Quantitative Analysis (No. 25); TranState Working Papers 25; University of Bremen, Collaborative Research Center 597: Bremen, Germany, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Bevir, M. (Ed.) The Sage Handbook of Governance; Sage: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Ball, S.; Junemann, C. Networks, New Governance and Education; The Policy Press: Bristol, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Benz, A.; Lütz, S.; Schimank, U.; Simonis, G. (Eds.) Handbuch Governance. Theoretische Grundlagen und Empirische Anwendungsfelder; VS Verlag: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Marsh, D. The New Orthodoxy: The Differentiated Polity Model. Public Adm. 2011, 89, 32–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parreira do Amaral, M.; Dale, R.; Loncle, P. (Eds.) Shaping the Futures of Young Europeans: Education Governance in Eight European Countries; Symposium Books: Oxford, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. Strategic Education Governance. Project Plan and Organizational Framework; OECD: Paris, France, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Solesin, L. The Global Governance of Education 2030: Challenges in a Changing Landscape; Education Research and Foresight Working Paper 26; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2020; pp. 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Pang, N.S.K.; Chan, P.W.K. (Eds.) School Governance in Global Contexts. Trends, Challenges and Practices; Routledge: London, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Allain-Dupré, D. The multi-level governance imperative. Br. J. Politics Int. Relat. 2020, 22, 800–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burns, T.; Köster, F.; Fuster, M. Education Governance in Action: Lessons from Case Studies; Educational Research and Innovation; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Altrichter, H. Theory and Evidence on Governance: Conceptual and empirical strategies of research on governance in education. Eur. Educ. Res. J. 2010, 9, 147–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greany, T.; Higham, R. Hierarchy, Markets and Networks. Analysing of ‘Self-Improving School-Led System’ in England and Implications for Schools; Institute of Education Press: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Ehren, M.C.M.; Baxter, J. Governance of Education Systems: Trust, accountability and capacity in hierarchies, markets and networks. In Trust, Accountability and Capacity in Education System Reform; Global Perspectives in Comparative, Education; Ehren, M.C.M., Baxter, J., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA; Abingdon, VA, USA, 2021; pp. 30–54. [Google Scholar]

- Adler, P. Market, hierarchy and trust: The knowledge economy and the future of capitalism. Organ. Sci. 2001, 12, 215–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jessop, B. Metagovernance. In The Sage Handbook of Governance; Bevir, M., Ed.; Sage: London, UK, 2011; pp. 23–106. [Google Scholar]

- Grimaldi, E.; Landri, P.; Serpieri, R. NPM and the Reculturing of the Italian Education System. The making of new fields of visibility. In New Public Management and the Reform of Education. European Lessons for Policy and Practice; Gunter, H.M., Grimaldi, E., Hall, D., Serpieri, R., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2016; pp. 96–110. [Google Scholar]

- Benadusi, L.; Giancola, O.; Viteritti, A. L’autonomia dopo l’Autonomia nella scuola. Premesse, esiti e prospettive di una policy intermittente. Auton. Locali Serv. Soc. 2020, 43, 325–341. [Google Scholar]

- Frankowski, A.; van der Steen, M.; Bressers, D.; Schulz, M. Dilemmas of Central Governance and Distributed Autonomy in Education; OECD Education Working Papers; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2018; p. 189. [Google Scholar]

- Ballarino, G.; Checchi, D. (Eds.) Sistema Scolastico e Disuguaglianza Sociale; Il Mulino: Bologna, Italy, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Benadusi, L.; Giancola, O. Equità e Merito Nella Scuola. Teorie, Indagini Empiriche, Politiche; Franco Angeli: Milano, Italy, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Torrigiani, C.; Pandolfini, V.; Giannoni, P.; Benasso, S. I Percorsi per le competenze trasversali e per l’orientamento: Quali dimensioni valutative? Uno studio esplorativo. RIV Rass. Ital. Valutazione 2020, 77, 115–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schreier, M. Qualitative Content Analysis in Practice; Sage: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Croucher, S.M.; Cronn-Mills, D. Content Analysis. In Understanding Communication Research Methods. A Theoretical and Practical Approach; Croucher, S.M., Cronn-Mills, D., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2021; pp. 147–161. [Google Scholar]

- Palumbo, M.; Pandolfini, V. Lifelong learning policies and young adults: Considerations from two Italian case studies. Int. J. Lifelong Educ. 2019, 39, 75–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walther, A. Support across life course regimes. A comparative model of social work as construction of social problems, needs, and rights. J. Soc. Work 2017, 17, 277–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walther, A.; Parreira do Amaral, M.; Cuconato, M.; Dale, R. (Eds.) Governance of Educational Trajectories in Europe: Pathways, Policy and Practice; Bloomsbury: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).