Technology-Mediated Hindustani Dhrupad Music Education: An Ethnographic Contribution to the 4E Cognition Perspective

Abstract

1. Introduction

- The assessment of mainstream videoconferencing platforms in adequately meeting the demands of oral music instruction, as in Dhrupad;

- The exploration of the viability in effectively capturing, conveying, and transmitting salient movement information through these platforms;

- The understanding of the potential impact of the observed embodiment shifts on the transmission of oral music traditions and the risks of overlooking elements of the music style’s heritage over time;

- The consideration of novel kinds of technologies and alternative methods for conveying embodied information that need to be developed to better support the educational needs of oral and underrepresented music traditions that do not rely on written scores.

2. Background

2.1. Traditional Pedagogy of Hindustani Dhrupad Music

2.2. Observed Shift in Dhrupad Music Pedagogy

2.3. The 4E Cognition Framework in Music Pedagogy

3. Materials and Methods

4. Interview Analysis—Results

Marianne Svašek: ‘I had a very deep connection as if we were sitting in one room’. (interview, online, 15 September 2023)

Celinn Wadier: ‘If I had discovered Dhrupad online, maybe I wouldn’t have continued’. (interview, online, 15 September 2023)

‘One of my students said, “I want to see you online because I missed something”. So, I started to think, “OK, what do you miss? What do you want from me more than material music and the whole vibe”? See, the interesting thing is you can have a very deep connection with the person, as if you are together, it is very much possible. If you’re both very concentrated, you just have the communication. […] So, it is a human thing in between two people. Not the matter, not the teaching, not the subject, not the material’. (Marianne Svašek, interview, Rotterdam, the Netherlands, 27 September 2010)

‘It depends actually on the person, on the student, but it’s not so precise and easy online. […] I can learn! You can appreciate the music without the movements, when you listen to a recording for instance. [But] if you want to sing, then it’s good to see what’s going on. You need to look and to be in the presence of the person to learn!’ (Celinn Wadier, interview, online, 15 September 2023)

4.1. Embodied Aspect

4.1.1. Challenges in Physical Engagement as a Rich Sensorial Experience

‘I didn’t like it [online class] for the first maybe two or three months. It was very disembodied, the whole experience’. (Gauri Raje, interview, online, 18 September 2023)

‘You see, [in-person] you have a picture much more precise of what’s going on. So, I can see also what’s going on with the jaw etc. […] If I learn with Marianne [Svašek], or if I learn with ustad (guru, here referring to Zia Fariduddin Dagar), we were having this whole picture of the energy and gesture with the voice and the ragas. […] You have the voice, you have the sound, you have the vibration. And you know, also for the breathing. This is something that I also need to share. Well, it’s much better in person, because the sound, you hear much better’. (Celinn Wadier, interview, online, 15 September 2023)

‘I think the visual engagement is slightly different for me when a person is live in front of me. [In-person] I don’t need to look at the person in order to sense them. When I’m working with Pelva live, I’m in her house and learning from her, I’m not always looking at her. Because a lot of the times when I sing, my eyes are closed or they’re looking elsewhere, they’re not looking at Pelva. But when I’m online, that element for me is lost. I can’t hear a person breathe. If they shift their bum slightly, I can’t feel it. So, that source material is lost. And then visual has to become much stronger for me’. (Gauri Raje, interview, online, 18 September 2023)

‘You cannot see how he’s sitting and so on. So, it’s way more difficult to keep the whole picture. You have to really focus on different things at different times. And then the other thing is I cannot watch from different angles, […] I just see the front side’. (Markus Schmidt, interview, online, 11 May 2023)

‘Then my body posture, I found out that it was not good for Dhrupad. I didn’t sit straight. That caused the voice projection that resulted. Madam corrected me when I was in the workshop. But in online, she couldn’t notice that, I feel’. (Aarya Patwardhan, interview, online, 16 September 2023)

4.1.2. Challenges in the Embodied Conception of Personal Space

‘Well, it’s much better in person! Also about the gesture: It’s not only the arms who are moving, it’s also the heaps. […] If I teach online, sometimes they can see how my hand moves, but then they don’t see me dοing anymore… [she lowers the camera to the abdomen]. There is something happening also with the heaps and how you are carrying yourself. So, it is more difficult to see how the student is carrying himself or herself online, because you don’t have this full picture’. (Celinn Wadier, interview, online, 15 September 2023)

‘The voice projection and all, and the frequency is understood much better in person, I feel. Actually, I experienced this this year. In online, when madam teaches me, I’m singing what I feel right. But when I went to the workshop, I found out that I didn’t have that voice throat; madam says that you have to build your core, so that your voice projection is much better. So, actually, I was singing all right, but then the projection that is needed for that particular music form, is not right. That’s what I found out. In-person class is important, because I didn’t know that in the online classes. I found out when I went to the workshop. That doesn’t happen in online classes. (Aarya Patwardhan, interview, online, 16 September 2023)

4.2. Enacted Aspect

4.2.1. Challenges in Goal-Directed Manual Interactions

‘They [students] take much less of that [gestures in online classes]. Much less! Because I’ve seen there are some students who after, say, a year of online come and meet me in person and then they realize “Oh, wow, it’s like this, you know?”. And then they start doing this and that [she gestures in the air] and they are like “this has changed so much for me. I didn’t know this for a long time”. […] I don’t think so [that this gets across through the video]’. (Pelva Naik, interview, Cardedeu, Spain, 9 April 2023)

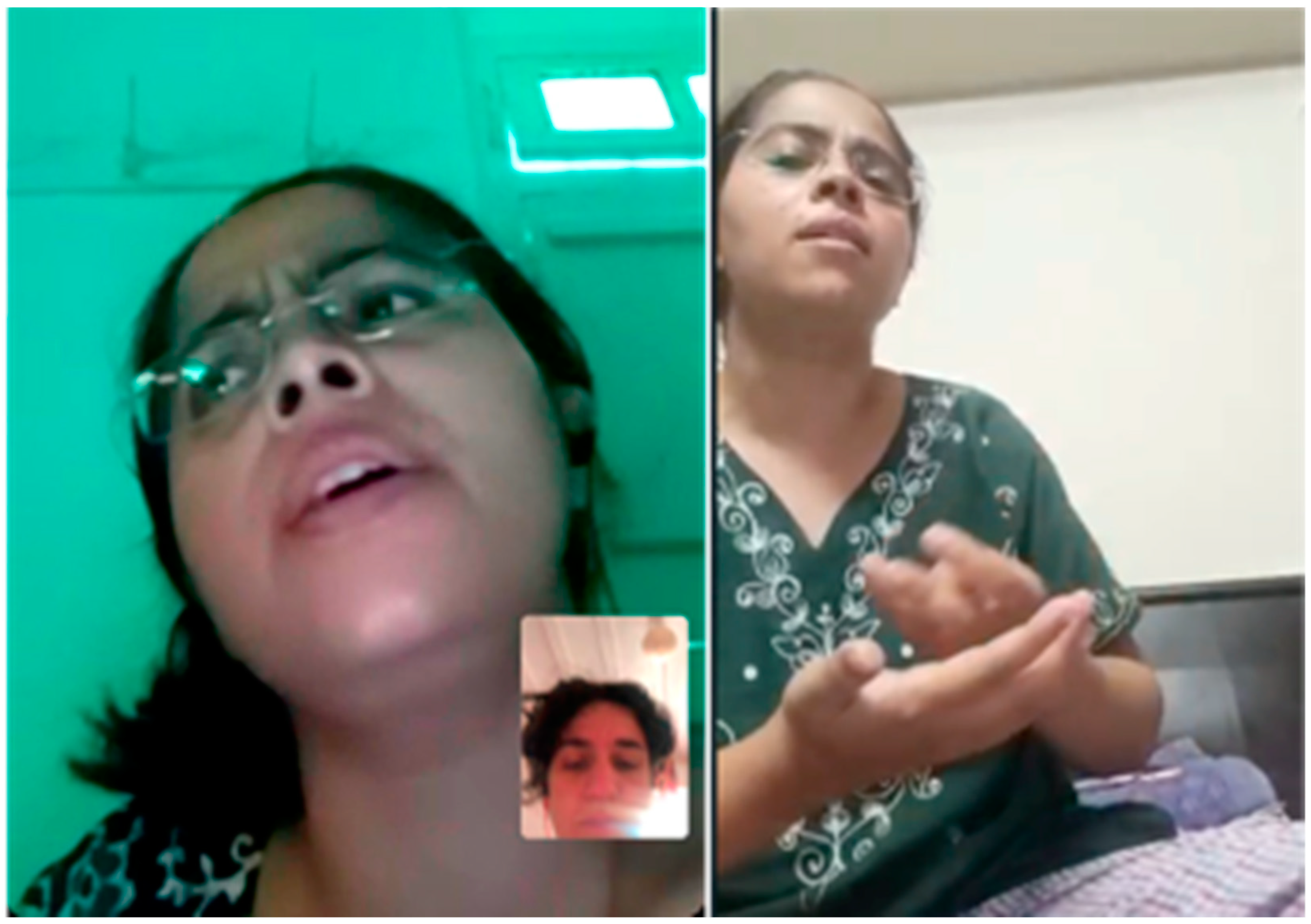

‘We do classes with just WhatsApp video calls. So, most of the times I just see her face. So, in this sense, the online classes are really limited with that. I mean, I cannot see this whole thing, which, when I was singing with Pelva in this class [in-person] it was really amazing. And the other thing, […] the two first years I was studying Dhrupad, I was watching a lot of videos of Uday Bhawalkar, for example, of the Dagar brothers as well. And it was very important to me to grasp…, it was one thing that I was really paying attention; what is the movement! Sometimes they are very subtle, they are just little movements. I have realized that, for example, [by] seeing Pelvis singing in concert or the meeting or the thing that you did with her and not the way that she was explaining things, I understood a lot of things there. Because I saw the rest of it’. (Isadora Reig, interview, online, 7 May 2023)

‘[In the traditional in-person setting] we were like kind of imitating or interacting and that was a way of learning also. This is very, very important and that’s for sure: online is not that easy to do. You have to guess!’ (Celinn Wadier, interview, online, 15 September 2023)

4.2.2. Indirect Inference of Missing Multimodal Information

‘The other thing is that this part [shows shoulders and head], this much can be really expressive as well. So, there are times where you’re trying to hit something, but you’re actually going back. And you know there’s that tension that is then conveyed. So, that I’m not just picking up on that, but I’m also picking up on how Pelva’s neck is moving, how her shoulders are moving. Is it going forward, is it going back? So, I’m getting the sense of how her abdominal moves, for instance, from that’. (Gauri Raje, interview, online, 18 September 2023)

‘I have learned to see a lot in the face about the singing. […] I have become used to see a lot in the face, different notes’. (Isadora Reig, interview, online, 7 May 2023)

‘Seeing Pelva singing in concert or the workshop I understood a lot of things, because I saw the rest of it. [In the online], I can see her face singing, so I can see somehow the movement reflected in the body, but very limited. But when I can see Pelva singing or in one-to-one class, it’s like, “oh, wow, this whole thing, this other whole thing”’. (ibid.)

4.2.3. Sense of Presence and Connection

‘It is not just about the sound. That’s something I’ve learned. So, it’s also the “presence”. So, the video helps only to make you feel that “ok, that person is present”. Both ways. So, it’s like a make-belief. You feel that the presence is there, but it’s not the same as being in person. So, that’s very distant’. (Pelva Naik, interview, Cardedeu, Spain, 9 April 2023)

‘I feel that when we have the classes in person, we understand more. The teacher also finds it easy to explain that particular topic and even the student understands much better than the online classes. […] We get connected to the teacher when she is sitting just right in front of us. That connect between us, between me and madam makes me understand that particular concept much better’. (Aarya Patwardhan, interview, online, 16 September 2023)

‘With the WhatsApp call I don’t see the hands, I don’t see the body. I don’t see nothing. Just the face. But somehow the face is close. You are close. So, it was important’. (Isadora Reig, interview, online, 7 May 2023)

‘Watching a lot of recordings, a lot of concerts [of Dhrupad singer Uday Bhawalkar], has been really important for me, because I have been totally able to watch the movement, to study it and the note and the ragas and to get immersed. But with online classes no! It was more important to have this closeness. But the moment that I was seeing Meghana in these workshops, it was really making a difference. Like, “oh no, I need to be more close to it”’. (ibid.)

‘In order to get the whole body, she [Naik, her teacher] would have to move away from the camera, and that gives it a kind of distance. I think what I appreciate is the kind of sense of closeness that I get, and with that, I’m picking up from this bit. I don’t know if I would get anything more by seeing the whole body’. (Gauri Raje, interview, online, 18 September 2023)

‘Yes, maybe. Knowing that I have to make sure that I can hear them good. And then I would be a bit far, sort of. Because we are already separated like this on the screen. So, the energy is really difficult to feel. But I have to see the student also, that’s the thing. If I’m going to sit far away, I don’t see the student very well’. (Celinn Wadier, interview, online, 15 September 2023)

4.2.4. Visual Dominance, Fatigue and Stress

‘I think online over time I’ve learned to very quickly pick up clues visually, so that now it’s almost second nature. But […] I can’t be online more than two hours, I just zone out. That’s not to say if I’m in meetings in-person, I don’t zone out. But part of my body is still working, and I will still recall things later on. It is more exhausting. Definitely’. (Gauri Raje, interview, online, 18 September 2023)

‘And at the same time it’s a thing... For example, first two years I was really struggling with it. She was looking me sometimes, because I was out of tune or I was trying, but I was really nervous. And it was difficult to have the face here [so close] because it was very clear. […] Just the few moments that we needed to change to just audio call, I completely relaxed. It’s like, OK, I don’t have the face here [close to mine], like “what are you doing?” But this was at the beginning’. (Isadora Reig, interview, online, 7 May 2023)

4.2.5. Compensation through Increased Use of Verbal Communication and Visual Aids

‘In my own classes what I’ve started observing with myself is that I am double-explaining the visuals; much more than when I am in normal classes. Because there I feel that that will help. I really go into the whole metaphors, visuals and all that. I end up talking, explaining so much more. When you are in person, you don’t really have to explain too much in words. You can exchange it with energy in space and just by singing’. (Pelva Naik, interview, Cardedeu, Spain, 9 April 2023)

‘I have a tendency to explain more online. I can also give explanations in the in-presence. But sometimes I have to put into words more online, because you need to. Though in-presence sometimes you don’t need to, you can show more’. (Celinn Wadier, interview, online, 15 September 2023)

4.2.6. Challenges in the Enacted Conception of the Peri-Personal Space

‘But online, usually it’s this [she shows just the head], so you don’t see the whole body. So, you don’t know just how much of the bhav (Expression in Hindustani music) there should be, or just how much of the delicacy or just how quickly she is lifting something or how sharply she’s going somewhere, that I think it’s the gestures that kind of confirm things for me’. (Gauri Raje, interview, online, 18 September 2023)

‘Yes, it [paying attention at the gestures] plays a role, but with the online classes, WhatsApp video calls, most of the times I just see her face. So, in this sense, the online classes are really limited with that [gestures]. I mean, I cannot see this whole thing, which, when I was singing in this class with Pelva [Naik], it was really amazing’. (Isadora Reig, interview, online, 7 May 2023)

4.3. Extended Aspect

4.3.1. Challenges in Manual Interactions with Imagined Objects (MIIOs)

‘I try to transmit it as much as I can online, and it’s for the comfort of the person. So, I speak about it and I try to show it a bit like… I use images, like “you imagine you have an elastic or you imagine you have some warm sun here or a cat purring like this and you just put your hands like this”. I also tell it when I am in presence, but they can see also. They can see it better, and they can also see the way I move’. (Celinn Wadier, interview, online, 15 September 2023)

‘And I think online makes a big difference. Because when I’m live with Pelva, I can feel the heaviness or the gravity. In-person, even if Pelva didn’t make the gestures, there would be a certain way in which the breath moves in her body, that if I’m in her presence, I sense it and I can see where she’s going. You know, there’s something about that body sensory communication, which sometimes gets filtered out online. I think online the gestures have really helped to communicate the sensory element. So, Pelva’s gestures help me understand—say—the weight, the bhav that she gives somewhere or the kind of meend (Pitch glide/glissando) that she is trying to communicate, the delicacy of the meend sometimes, that with the gestures, becomes more present for me. […] I can catch that a little bit more’. (Gauri Raje, interview, online, 18 September 2023)

4.3.2. Challenges in the Extended Conception of Peri-Personal Space

‘Even though Pelva would be making gestures, I just wouldn’t have a sense of things around her’. (Gauri Raje, interview, online, 18 September 2023)

‘My way of teaching has changed a lot, because that [video] frame is there. I am looking at myself in the frame and so I use it as a board, so I am… [singing notes] ‘Sa–Re–Ga’ (1st–2nd–3rd degree of the scale in Hindustani music), so I am not doing this [MIIOs] any more when I am doing alap (improvisation) or when I am explaining, because I am looking at the person, but I am showing it, as if I am making a painting’. (Pelva Naik, interview, Cardedeu, Spain, 9 April 2023)

4.4. Embedded Aspect

4.4.1. Conceptual Adaptation

‘Getting together with somebody in person is a very complicated system of all kinds of information and just a very little part of it gets through to your conscious mind. The other is absorbed unconsciously. And there are many things that you will miss when you just have a Skype conversation’. (Markus Schmidt, interview, online, 11 May 2023)

‘In the beginning, when I started learning with her, I didn’t have a sense of how she was, or who she was. I didn’t know her at all. And then, now, over time, I have a better sense. Also, because I’ve been to her place now. It helped. Because I know this place she is in, from where she is, kind of. I think over time, there were times where we just talked in sessions we didn’t sing, or sometimes we joked around, or we laughed. And that gave her body more of a materiality. I just get a sense of her body more and more. So, then it’s not as strange anymore. So over time, even though I had not been with her in person, I had a sense of her as a person. I kind of have a memory of the weight, when she sits her whole body, what’s the weight like. Or when she shifts a little bit. What is that shifting energetically? I just have a sense of it a little more now. Now, I’m used to Pelva, because I’ve worked with her for so long. So, I think I’ve arrived at a place where I’m comfortable with online’. (Gauri Raje, interview, online, 18 September 2023)

4.4.2. Challenges in the Embedded Conception of Extra-Personal Space

‘You know, emotions you can transfer through sound only. It’s possible to do it even without visuals, […] a Whatsapp audio call. But these other things work with space. And these other things don’t happen [in online classes]. […] There is a lack of the energy. So, there is a lot of effort, so it can be tiring, but the visuals help. […] And you can’t just go on teaching alap for 50 min or 1 h of class. But you can do that when you are in person somehow. Because there’s this availability. It’s vaster somehow. […] It’s like you are on a bigger vehicle, you know. And you can have that space. So, it feels more spacious working on alap and a raga in person than when you have one hour of [online]. So, that one hour is too much effort than two hours of just sitting and working on that rag in person’. (Pelva Naik, interview, Cardedeu, Spain, 9 April 2023)

‘What I would like to minus is the frame! It’s like you are looking through prison window. So, maybe if I had a space where I can’t see the frame? Just larger space! Where there is no […] frame between the two people. Or at least there is an illusion that there is no frame. I mean my eyes are not disturbed by looking at the limited space between me and my student. […] What I lack is the horizon! […] It’s not a problem, but you make believe a lot. You start imagining a lot. So, what you’re doing is you are trying to go as close as possible to the in-person. […] Doesn’t matter if the sound is not as good also. […] That was secondary. First, is this nearness. And it has to match the sound. So, if the sound is near, I want you near. Otherwise, my brain is starting “Is that really you? Or it’s something else?” [improvement requests] Βetter sound that matches that ambience, definitely; that space! That larger space. And no frame!’ (ibid.)

‘There is the space involved, there is the acoustic also. When I speak with you now, my breathing is not that clear also. And the silence in between the phrases, which we can call space as well, it’s also a part of the music, that is teached. […] It’s like I’m full ears online. And it’s flat! It’s very tiny. […] Many times, actually, movements, they are quite subtle, and it’s not that easy to see it, if you’re not there actually directly. […] So that was always much better [in-person]. […] If she [her teacher, Marianne Svašek] is in front of me [in-person], it’s three-dimensional. It’s going many places and I can feel her movement, I can feel the emotion, I can feel some energy, and this [sense of space] I get. This I don’t get on online, I don’t get same, I mean. […] And there [in-person] we share… It’s not that obvious: We don’t touch it, we don’t touch each other, let’s say, but even if it is from here (she points at her ear), this is obvious that there is a big difference. If I do this (she touches the screen), onto the screen, you don’t feel anything. And this is also different in in-presence and in online. But this I can really feel more as a student. […] I also wonder how you feel the presence of the person…’. (Celinn Wadier, interview, online, 15 September 2023)

‘If technically it’s perfect, like you have a big screen and they see you entirely and you see the person and you hear it good, for sure it’s better. But the simplicity of the in-presence and the space between… the space between the people also, to me it’s also part of the transmission. In this music’. (ibid.)

‘I could say I need maybe to see more space. But for example, Meghana, she uses to do three or four times a workshop with more students. And in this case she uses a big screen and you can see the whole body and you can see the movement. But because she needs to be with more distance from the camera, at the same time it’s not that close as when I sing face-to-face, which is really… You can see the entire body, her sitting or playing the tempura maybe, you can see the movement. At the beginning I thought, “Oh, wow, that’s cool, because I can see the movement”. But then it was like, “Oh, no. But it is distant as well”. So, this scene when face-to-face, I cannot see the movement, but there is something that is close’. (Isadora Reig, interview, online, 7 May 2023)

4.5. Future Technology Interventions

‘[I would need] something to be able to see the movements. But not seeing the face, not seeing in the camera... Something more like VR reality, for example. Something you can see the movements and you can see the thing, but you don’t see it in one big screen. I think I will need additional space, to give more deep experience of it’. (Isadora Reig, interview, online, 7 May 2023)

5. Discussion

- Discussed under the embodied principle:

- -

- Reports from participants have highlighted a deficiency of multisensory information exchange in screen-based interactions compared to in-person contexts, where various senses beyond just auditory, including sight (also peripheral vision), touch, and even smell, contribute to a more profound, embodied understanding of the musical material. As a result, these digital environments restrict the transfer of covert embodied aspects. For instance, limited visual transparency and acoustic clarity hinder the identification of subtle details in the recommended postures and covert aspects of embodiment that enable effective sound production. Beyond communication asynchrony and differences in eye contact and directional gaze, crucial in social interaction [83], the limited visibility of the entire body during virtual interactions is known to impede quick and accurate emotion perception due to the absence of rich body language cues (ibid.).

- Discussed under the enacted principle:

- -

- Similarly, there is limited capacity to transmit even the overt embodied and enacted aspects of singing gestures in the online setting. Even when they remain observable, their clarity is diminished compared to in-person interactions due to the constrained transmission of multimodal information through the screen during videoconferencing teaching sessions. Sometimes, this information needs to be guessed.

- -

- Certain information can be indirectly inferred from other (bodily) cues. However, this process provides only a restricted perspective of the entire gestural engagement.

- -

- There is a wide consensus among participants that online teaching sessions lack crucial elements of human social interaction, with recurring topics centered around the ideas of a limited sense of ‘presence’ and ‘connection.’ Online presence plays a key role for both educators and students in creating a supportive environment for the effective transmission of knowledge [84]. The disruption of social presence in video-mediated communication has been previously attributed to the absence of tactile feedback and the limited transmission of non-verbal cues, such as subtle nuances of facial expression and body language [85,86]. Every participant concurred that visual cues play a significant role in this aspect, albeit only providing a superficial sense of connection.

- -

- The interview material indicates a heightened reliance on visual cues during online teaching sessions, thought to be associated with increased fatigue levels. Biological anthropologists confirm that face-to-face interaction, prevailing for over 99% of human history [87], indicates an innate preference that is known as the media naturalness proposition in digital media [88]. It explains challenges, increased cognitive effort, and resulting fatigue in teleconferencing, negatively affecting collaboration satisfaction and effectiveness. Reports also corroborate the notion that stress is linked to an intense feeling of close scrutiny by the teacher, stemming from an intense gaze concentrated on the face alone due to the limited visibility of the body during videoconferencing.

- -

- To counterbalance the deficiency of multi-sensory gestural teacher–student interaction in the online context, teachers appear to rely more heavily on verbal communication (such as linguistic metaphors) and visual aids (verbal descriptors of musical imagery).

- Discussed under the extended principle:

- -

- The limited visibility of each other’s body (camera mainly focusing on the face) and the restricted capacity of videoconferencing platforms in effectively transmitting multimodal information appear to impact the transmission of MIIOs and the sensation of forces as well, i.e., the extended aspects of gestural transmission.

- Discussed under the embedded principle:

- -

- Several reports by participants suggest that one’s understanding relies on a complicated system of (multi-modal) information that—contrary to the in-person—does not become fully transmitted online. However, various interviews indicated that online participants’ interactions and engagement improved gradually as they developed a deeper understanding of the other person and his/her contingent presence within the surrounding environment, even if through the virtual context. These reports suggest a contextual adaptation to technology mediation that helps alleviate the initial apprehension of participants regarding the use of online means for music education.

- -

- Reports suggest that one’s understanding relies on a complicated system of extra-musical information about the social and environmental context. However, they also affirm a contextual adaptation to technology mediation, based on a deeper understanding of each other’s personality and their contingent presence within the surrounding environment, gradually leading to an improvement in teacher–student engagement.

- Challenges in the spatial perception of Dhrupad singing education:

- -

- Personal space, represented by the embodied aspect of the 4E framework: There is an even greater intricacy in conveying covert aspects of embodied engagement that are associated with the mechanics of vocal production, such as the deliberate and active control of the abdominal muscles, through the online medium than traditional in-person instruction. This intricacy is attributed to the limited exchange of multimodal information of screen-based interactions through sound, vision (peripheral too), touch, and even smell.

- -

- Peri-personal space, classified under the extended and enacted aspects of the 4E framework: Its perception becomes challenging in online settings due to the fact that cameras most often capture only the face, resulting in the limited visibility of each other’s gestures, including the utilization of MIIOs. Additionally, the mirroring of one’s gestures on the screen appears to confine the potential for gestural interaction with melodic content mainly to two-dimensional geometric (melographic) representations. This is in contrast to the three-dimensional experience of haptic-related forces and the required effort exerted, commonly encountered during in-person teaching sessions and performances. This constraint is associated with the limited (two-dimensional) visual affordances of common video platforms and has the potential to lead to a shift in gestural instructions and engagement as well as the perception of peri-personal space, as audio-visual sensory deprivation is also known to degrade visuo-tactile peri-personal space [89]. It also aligns with findings from neuroscience about the effects of the brain’s plasticity, whereby the neural representation of the peri-personal space (PPS) is expanded during real-world tool use but not when using tools in virtual environments [90].

- -

- Extra-personal space, organized under the embedded aspect of the 4E framework: A number of participants have reported that their primary concerns about screen-mediated online teaching interaction are space-related and rely on our complex somatosensory system. They revolve around the disruption of the shared ‘we-space’ in which real interpersonal interactions take place, the constrained frame of the video window, the absence of three-dimensional peripheral vision, spatialized audio, and space-related senses, such as touch and smell, the diminished visual clarity regardless of zoom level that affects the awareness of each other’s gaze, and finally, the audio-visual mismatch which currently renders the perception of space dubious. Interestingly, these reports surpassed commonly discussed technical issues, such as sound quality, internet disconnections, lag, etc.

6. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Name | Type of Interview | Date |

|---|---|---|

| Pelva Naik | In-person; Labyrinth Catalunya, Cardedeu, Spain | 9 April 2023 |

| Isadora Reig | Online | 7 May 2023 |

| Meghana Sardar | Online | 9 May 2023 |

| Markus Schmidt | Online | 11 May 2023 |

| Cellin Wadier | Online | 15 September 2023 |

| Marianne Svašek | Online | 15 September 2023 |

| Aarya Patwardhan | Online | 16 September 2023 |

| Gauri Raje | Online | 18 September 2023 |

References

- Small, C. Musicking: The Meanings of Performing and Listening; Music/Culture; University Press of New England: Hanover, NH, USA, 1998; ISBN 978-0-8195-2256-6. [Google Scholar]

- Leman, M. Embodied Music Cognition and Mediation Technology; The MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2007; ISBN 978-0-262-25655-1. [Google Scholar]

- Smirnov, A.; Price, M. Sound in Z: Experiments in Sound and Electronic Music in Early 20th Century Russia; Koenig Books: London, UK, 2013; ISBN 978-3-86560-706-5. [Google Scholar]

- Bremmer, M.; Nijs, L. The Role of the Body in Instrumental and Vocal Music Pedagogy: A Dynamical Systems Theory Perspective on the Music Teacher’s Bodily Engagement in Teaching and Learning. Front. Educ. 2020, 5, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simones, L.L. A Framework for Studying Teachers’ Hand Gestures in Instrumental and Vocal Music Contexts. Music. Sci. 2019, 23, 231–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nafisi, J. Gesture and Body-Movement as Teaching and Learning Tools in the Classical Voice Lesson: A Survey into Current Practice. Br. J. Music Educ. 2013, 30, 347–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Paparo, S.A. Embodying Singing in the Choral Classroom: A Somatic Approach to Teaching and Learning. Int. J. Music Educ. 2016, 34, 488–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohut, D.L. Musical Performance: Learning Theory and Pedagogy; Stipes Pub. Co.: Champaign, IL, USA, 1992; ISBN 978-0-87563-415-9. [Google Scholar]

- Rahaim, M. Musicking Bodies: Gesture and Voice in Hindustani Music; Music/Culture; Wesleyan University Press: Middletown, CT, USA, 2012; ISBN 978-0-8195-7325-4. [Google Scholar]

- Jain, V. India Together: Changing Notes of Music Education—22 April 2005. Available online: https://indiatogether.org/music-society (accessed on 14 December 2023).

- Farrell, G. Indian Music and the West: Gerry Farrell; Clarendon Press: Oxford, UK; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK; New York, NY, USA, 1997; ISBN 978-0-19-816391-6. [Google Scholar]

- Camlin, D.A.; Lisboa, T. The Digital ‘Turn’ in Music Education (Editorial). Music Educ. Res. 2021, 23, 129–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newen, A.; De Bruin, L.; Gallagher, S. The Oxford Handbook of 4E Cognition, 1st ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2018; ISBN 978-0-19-873541-0. [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro, L.A. (Ed.) The Routledge Handbook of Embodied Cognition; Routledge Handbooks in Philosophy; First Issued in Paperback; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2017; ISBN 978-1-138-57397-0. [Google Scholar]

- Roy, J. The Internet Guru: Online Pedagogy in Indian Classical Music Traditions. Asian Music 2016, 47, 103–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nettl, B. The Study of Ethnomusicology: Thirty-One Issues and Concepts, Third edition.; University of Illinois Press: Urbana, IL, USA, 2005; ISBN 978-0-252-03033-8. [Google Scholar]

- Schippers, H. The Guru Recontextualized? Perspectives on Learning North Indian Classical Music in Shifting Environments for Professional Training. Asian Music 2007, 38, 123–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paschalidou, S. Effort Inference and Prediction by Acoustic and Movement Descriptors in Interactions with Imaginary Objects during Dhrupad Vocal Improvisation. Wearable Technol. 2022, 3, e14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, K. The Memory of the Flesh: The Family Body in Somatic Psychology. Body Soc. 2002, 8, 25–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robert Caro Ustad Zia Fariduddin DAGAR/The Dhrupad Legend. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FcGz-8ZxMrU (accessed on 14 December 2023).

- Fatone, G.A.; Clayton, M.; Leante, L. Imagery, Melody and Gesture in Cross-Cultural Perspective. In New Perspectives on Music and Gesture; Gritten, A., King, E., Eds.; Ashgate Publishing: Farnham, UK, 2011; pp. 203–220. [Google Scholar]

- Van der Meer, W.; Rao, S. What You Hear Isn’t What You See: The Representation and Cognition of Fast Movements in Hindustani Music. In Proceedings of the International Symposium Frontiers of Research on Speech and Music, Baripada, India, 30 July 2006; pp. 12–20. [Google Scholar]

- Martin, C. Time, Gesture and Attention in a Khyāl Performance. Asian Music 2007, 38, 71–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leante, L. The Lotus and the King: Imagery, Gesture and Meaning in a Hindustani Rāg. Ethnomusicol. Forum 2009, 18, 185–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratcliffe, M. Perception, Exploration, and the Primacy of Touch. In The Oxford Handbook of 4E Cognition; Newen, A., De Bruin, L., Gallagher, S., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2018; pp. 280–300. ISBN 978-0-19-873541-0. [Google Scholar]

- Pallasmaa, J. An Architecture of the Seven Senses. In Questions of Perception: Phenomenology of Architecture; Holl, S., Pallasmaa, J., Perez-Gomez, A., Eds.; William Stout Publishers: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1994; pp. 27–37. [Google Scholar]

- Serino, A.; Haggard, P. Touch and the Body. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2010, 34, 224–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warren, A.; Welton, M. On Touch. Perform. Res. 2022, 27, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garner, J. Kinesthetic Spectatorship in the Theatre: Phenomenology, Cognition, Movement, 1st ed.; Cognitive Studies in Literature and Performance; Springer International Publishing: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany; Palgrave Macmillan: Cham, Switezerland, 2018; ISBN 978-3-319-91794-8. [Google Scholar]

- Zahavi, D. Self and Other: Exploring Subjectivity, Empathy, and Shame, 1st ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2014; ISBN 978-0-19-959068-1. [Google Scholar]

- Huang-Kokina, A. Touching through Music, Touching through Words: The Performance and Performativity of Pianistic Touch in Musical and Literary Settings. Perform. Res. 2022, 27, 48–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haynes, A.; Lawry, J.; Kent, C.; Rossiter, J. FeelMusic: Enriching Our Emotive Experience of Music through Audio-Tactile Mappings. Multimodal Technol. Interact. 2021, 5, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cléry, J.; Guipponi, O.; Wardak, C.; Ben Hamed, S. Neuronal Bases of Peripersonal and Extrapersonal Spaces, Their Plasticity and Their Dynamics: Knowns and Unknowns. Neuropsychologia 2015, 70, 313–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizzolatti, G.; Luppino, G.; Matelli, M. The Organization of the Cortical Motor System: New Concepts. Electroencephalogr. Clin. Neurophysiol. 1998, 106, 283–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berthoz, A. Reference Frames for the Perception and Control of Movement. In Brain and Space; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1991; pp. 81–111. ISBN 978-0-19-854284-1. [Google Scholar]

- Millar, S. Space and Sense; Psychology Press: London, UK, 2008; ISBN 978-1-135-42226-4. [Google Scholar]

- Làdavas, E.; Farnè, A. Neuropsychological Evidence of Integrated Multisensory Representation of Space in Humans. In The Handbook of Multisensory Processes; Calvert, G.A., Spence, C., Stein, B.E., Eds.; The MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2004; pp. 799–818. ISBN 978-0-262-26970-4. [Google Scholar]

- Howard, I.P.; Templeton, W.B. Human Spatial Orientation; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1966; ISBN 978-0-608-11450-7. [Google Scholar]

- Paschalidou, P.-S. Effort in Gestural Interactions with Imaginary Objects in Hindustani Dhrupad Vocal Music. Ph.D. Thesis, Durham University, Durham, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Krueger, J. Affordances and the Musically Extended Mind. Front. Psychol. 2014, 4, 1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lloyd, D.M. The Space between Us: A Neurophilosophical Framework for the Investigation of Human Interpersonal Space. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2009, 33, 297–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cassio, F. Il Nāda Yoga, La Scienza Del Suono Nella Tradizione Musicale Indiana. In Conscientia Musica. Contrappunti per Rossana Dalmonte e Mario Baroni; Addessi, A., Macchiarella, I., Privitera, M., Russo, M., Eds.; LIM: Lucca, Italy, 2010; pp. 265–278. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, T.D. Global Pop; Routledge: London, UK, 2014; ISBN 978-1-135-25408-7. [Google Scholar]

- Neuman, D. The Life of Music in North India: The Organization of an Artistic Tradition; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1990; ISBN 978-0-226-57516-2. [Google Scholar]

- Baralou, E.; Tsoukas, H. How Is New Organizational Knowledge Created in a Virtual Context? An Ethnographic Study. Organ. Stud. 2015, 36, 593–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doumanis, I.; Economou, D.; Sim, G.R.; Porter, S. The Impact of Multimodal Collaborative Virtual Environments on Learning: A Gamified Online Debate. Comput. Educ. 2019, 130, 121–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lombard, M.; Ditton, T. At the Heart of It All: The Concept of Presence. J. Comput.-Mediat. Commun. 2006, 3, JCMC321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cesari, V.; Galgani, B.; Gemignani, A.; Menicucci, D. Enhancing Qualities of Consciousness during Online Learning via Multisensory Interactions. Behav. Sci. 2021, 11, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fauville, G.; Luo, M.; Queiroz, A.C.M.; Lee, A.; Bailenson, J.N.; Hancock, J. Video-Conferencing Usage Dynamics and Nonverbal Mechanisms Exacerbate Zoom Fatigue, Particularly for Women. Comput. Hum. Behav. Rep. 2023, 10, 100271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serino, A. Peripersonal Space (PPS) as a Multisensory Interface between the Individual and the Environment, Defining the Space of the Self. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2019, 99, 138–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rottondi, C.; Chafe, C.; Allocchio, C.; Sarti, A. An Overview on Networked Music Performance Technologies. IEEE Access 2016, 4, 8823–8843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, R. Aesthetic and Technical Strategies for Networked Music Performance. AI Soc. 2023, 38, 1871–1884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alexandraki, C. Experimental Investigations and Future Possibilities in Network-Mediated Folk Music Performance. In Computational Phonogram Archiving; Bader, R., Ed.; Current Research in Systematic Musicology; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; Volume 5, pp. 207–228. ISBN 978-3-030-02694-3. [Google Scholar]

- Biasutti, M.; Antonini Philippe, R.; Schiavio, A. Assessing Teachers’ Perspectives on Giving Music Lessons Remotely during the COVID-19 Lockdown Period. Music Sci. 2022, 26, 585–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodrich, A. Online Peer Mentoring and Remote Learning. Music Educ. Res. 2021, 23, 256–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koutsoupidou, T. Online Distance Learning and Music Training: Benefits, Drawbacks and Challenges. Open Learn. J. Open Distance E-Learn. 2014, 29, 243–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duffy, S.; Healey, P. A New Medium for Remote Music Tuition. J. Music Technol. Educ. 2017, 10, 5–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiavio, A.; Nijs, L. Implementation of a Remote Instrumental Music Course Focused on Creativity, Interaction, and Bodily Movement. Preliminary Insights and Thematic Analysis. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 899381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ward, F. Technology and the Transmission of Tradition: An Exploration of the Virtual Pedagogies in the Online Academy of Irish Music. J. Music Technol. Educ. 2019, 12, 5–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pudaruth, S.K. Online Teaching and Learning of Hindustani Classical Vocal Music: Resistance, Challenges, and Opportunities. In Academic Voices; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2022; pp. 147–159. ISBN 978-0-323-91185-6. [Google Scholar]

- Pearson, L. Gesture in Karnatak Music: Pedagogy and Musical Structure in South India. Ph.D. Thesis, Durham University, Durham, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Van der Schyff, D.; Schiavio, A.; Walton, A.; Velardo, V.; Chemero, A. Musical Creativity and the Embodied Mind: Exploring the Possibilities of 4E Cognition and Dynamical Systems Theory. Music Sci. 2018, 1, 205920431879231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallagher, S. Embodied and Enactive Approaches to Cognition; Cambridge Elements Elements in Philosophy of Mind; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2023; ISBN 978-1-00-920980-9. [Google Scholar]

- Gibson, J.J. The Ecological Approach to Visual Perception; Erlbaum: Hillsdale, NJ, USA, 1986; ISBN 978-0-89859-958-9. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, M.L. The Body in the Mind: The Bodily Basis of Meaning, Imagination, and Reason; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1992; ISBN 978-0-226-40318-2. [Google Scholar]

- Cox, A. Music and Embodied Cognition: Listening, Moving, Feeling, and Thinking; Indiana University Press: Bloomington, IN, USA, 2016; ISBN 978-0-253-02167-0. [Google Scholar]

- Reybrouck, M. Musical Sense-Making: Enactment, Experience and Computation, 1st ed.; Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group: London, UK, 2021; ISBN 978-0-429-27401-5. [Google Scholar]

- Menary, R. Introduction to the Special Issue on 4E Cognition. Phenomenol. Cogn. Sci. 2010, 9, 459–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chemero, A. Radical Embodied Cognitive Science, First MIT Press Paperback ed.; A Bradford Book; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA; London, UK, 2011; ISBN 978-0-262-51647-1. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan, K.; Schiavio, A. Extended Musicking, Extended Mind, Extended Agency. Notes on the Third Wave. New Ideas Psychol. 2019, 55, 8–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiavio, A.; van der Schyff, D. 4E Music Pedagogy and the Principles of Self-Organization. Behav. Sci. 2018, 8, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ryan, K.J.; Gallagher, S. Between Ecological Psychology and Enactivism: Is There Resonance? Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 1147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Casas-Mas, A.; Pozo, J.I.; Montero, I. Oral Tradition as Context for Learning Music From 4E Cognition Compared with Literacy Cultures. Case Studies of Flamenco Guitar Apprenticeship. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 733615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hood, M. The Ethnomusicologist, New ed.; Kent State University Press: Kent, OH, USA, 1982; ISBN 978-0-87338-280-9. [Google Scholar]

- Seaman, C.B. Qualitative Methods. In Guide to Advanced Empirical Software Engineering; Shull, F., Singer, J., Sjøberg, D.I.K., Eds.; Springer: London, UK, 2008; pp. 35–62. ISBN 978-1-84800-043-8. [Google Scholar]

- Boyatzis, R.E. Transforming Qualitative Information: Thematic Analysis and Code Development; Nachdr.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2010; ISBN 978-0-7619-0961-3. [Google Scholar]

- Clayton, M.; Dueck, B.; Leante, L. (Eds.) Experience and Meaning in Music Performance; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2014; ISBN 978-0-19-936953-9. [Google Scholar]

- Dejean, C.; Guichon, N.; Nicolaev, V. Compétences interactionnelles des tuteurs dans des échanges vidéographiques synchrones. Distances Savoirs 2010, 8, 377–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Noë, A. Action in Perception, 1st MIT Press paperback ed.; Representation and Mind; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2006; ISBN 978-0-262-64063-3. [Google Scholar]

- Varela, F.J.; Thompson, E.; Rosch, E. The Embodied Mind: Cognitive Science and Human Experience; 14. Print; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1993; ISBN 978-0-262-72021-2. [Google Scholar]

- Menin, D.; Schiavio, A. Rethinking Musical Affordances. Avant 2012, 3, 201–215. [Google Scholar]

- Okray, Z.; Jacob, P.F.; Stern, C.; Desmond, K.; Otto, N.; Talbot, C.B.; Vargas-Gutierrez, P.; Waddell, S. Multisensory Learning Binds Neurons into a Cross-Modal Memory Engram. Nature 2023, 617, 777–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kendon, A. Some Functions of Gaze-Direction in Social Interaction. Acta Psychol. 1967, 26, 22–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Themeli, C. Tele-Proximity: The Experienced Educator Perspective on Human to Human Connection in Distance Education. Ph.D. Thesis, Lancaster University, Lancaster, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Huisman, G. A Touch of Affect: Mediated Social Touch and Affect. In Proceedings of the 14th ACM International Conference on Multimodal Interaction, Santa Monica, CA, USA, 22–26 October 2012; pp. 317–320. [Google Scholar]

- Nowak, K.L.; Biocca, F. The Effect of the Agency and Anthropomorphism on Users’ Sense of Telepresence, Copresence, and Social Presence in Virtual Environments. Presence Teleoperators Virtual Environ. 2003, 12, 481–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boaz, N.T.; Almquist, A.J. Biological Anthropology: A Synthetic Approach to Human Evolution; Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 1997; ISBN 978-0-13-369208-2. [Google Scholar]

- Kock, N. The Psychobiological Model: Towards a New Theory of Computer-Mediated Communication Based on Darwinian Evolution. Organ. Sci. 2004, 15, 327–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noel, J.-P.; Samad, M.; Doxon, A.; Clark, J.; Keller, S.; Di Luca, M. Peri-Personal Space as a Prior in Coupling Visual and Proprioceptive Signals. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 15819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferroni, F.; Gallese, V.; Soccini, A.M.; Langiulli, N.; Rastelli, F.; Ferri, D.; Bianchi, F.; Ardizzi, M. The Remapping of Peripersonal Space in a Real but Not in a Virtual Environment. Brain Sci. 2022, 12, 1125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hauber, J.; Regenbrecht, H.; Billinghurst, M.; Cockburn, A. Spatiality in Videoconferencing: Trade-Offs between Efficiency and Social Presence. In Proceedings of the 2006 20th Anniversary Conference on Computer Supported Cooperative Work, Banff, AL, Canada, 4–8 November 2006; pp. 413–422. [Google Scholar]

- Von Laban, R.; Lawrence, F.C.; Lawrence, F.C. Effort: Economy of Human Movement, 2nd ed.; Reprinted; Macdonald and Evans: Plymouth, UK, 1979; ISBN 978-0-7121-0534-7. [Google Scholar]

- Tellier, M.; Stam, G. Stratégies Verbales et Gestuelles Dans l’explication Lexicale d’un Verbe d’action. In Spécificités et Diversité des Interactions Didactiques; Rivière, V., Ed.; Actes Académiques; Riveneuve éditions: Paris, France, 2012; pp. 357–374. [Google Scholar]

- Bohannon, L.S.; Herbert, A.M.; Pelz, J.B.; Rantanen, E.M. Eye Contact and Video-Mediated Communication: A Review. Displays 2013, 34, 177–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dreyfus, H.L. On the Internet, 2nd ed.; Thinking in Action; Routledge: Abingdon, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2009; ISBN 978-0-415-77516-8. [Google Scholar]

- Guichon, N.; Cohen, C. The Impact of the Webcam on an Online L2 Interaction. Can. Mod. Lang. Rev. 2014, 70, 331–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, D. What’s Lacking in Online Learning? Dreyfus, Merleau-Ponty and Bodily Affective Understanding: What’s Lacking in Online Learning? J. Philos. Educ. 2018, 52, 428–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hills, P.D.; Clavin, M.V.Q.; Tufft, M.R.A.; Gobel, M.S.; Richardson, D.C. Video Meeting Signals: Experimental Evidence for a Technique to Improve the Experience of Video Conferencing. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0270399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nijs, L.; Coussement, P.; Moens, B.; Amelinck, D.; Lesaffre, M.; Leman, M. Interacting with the Music Paint Machine: Relating the Constructs of Flow Experience and Presence. Interact. Comput. 2012, 24, 237–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Raheb, K.; Soulis, A.; Nastos, D.; Lougiakis, C.; Roussou, M.; Christopoulos, D.; Sofianopoulos, G.; Papagiannis, S.; Rüggeberg, J.; Katsikaris, L.; et al. Eliciting Requirements for a Multisensory eXtended Reality Platform for Training and Informal Learning. In Proceedings of the CHI Greece 2021: 1st International Conference of the ACM Greek SIGCHI Chapter, Athens, Greece, 25–27 November 2021; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Van Kerrebroeck, B.; Caruso, G.; Maes, P.-J. A Methodological Framework for Assessing Social Presence in Music Interactions in Virtual Reality. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 663725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Jiang, J.; Chen, Y.; Liu, R.; Yang, Y.; Xue, X.; Chen, S. Metaverse: Perspectives from Graphics, Interactions and Visualization. Vis. Inform. 2022, 6, 56–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biocca, F.; Harms, C.; Gregg, J. The Networked Minds Measure of Social Presence: Pilot Test of the Factor Structure and Concurrent Validity. In Proceedings of the 4th Annual International Workshop on Presence, Philadelphia, PA, USA, 21–23 May 2001; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Dall’Alba, G.; Barnacle, R. Embodied Knowing in Online Environments. Educ. Philos. Theory 2005, 37, 719–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, N.; Lefevre, D. Holographic Teaching Presence: Participant Experiences of Interactive Synchronous Seminars Delivered via Holographic Videoconferencing. Res. Learn. Technol. 2020, 28, 2265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reardon, G.; Dandu, B.; Shao, Y.; Visell, Y. Shear Shock Waves Mediate Haptic Holography via Focused Ultrasound. Sci. Adv. 2023, 9, eadf2037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smart, J.; Cascio, J.; Paffendorf, J. A Metaverse Roadmap: Pathways to the 3D Web. 2007. Available online: https://www.w3.org/2008/WebVideo/Annotations/wiki/images/1/19/MetaverseRoadmapOverview.pdf (accessed on 14 December 2023).

- Zhang, X.; Chen, Y.; Hu, L.; Wang, Y. The Metaverse in Education: Definition, Framework, Features, Potential Applications, Challenges, and Future Research Topics. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 1016300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kye, B.; Han, N.; Kim, E.; Park, Y.; Jo, S. Educational Applications of Metaverse: Possibilities and Limitations. J. Educ. Eval. Health Prof. 2021, 18, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Themelis, C.; Sime, J.-A. From Video-Conferencing to Holoportation and Haptics: How Emerging Technologies Can Enhance Presence in Online Education. In Emerging Technologies and Pedagogies in the Curriculum; Yu, S., Ally, M., Tsinakos, A., Eds.; Bridging Human and Machine: Future Education with Intelligence; Springer: Singapore, 2020; pp. 261–276. ISBN 9789811506178. [Google Scholar]

- Turchet, L. Musical Metaverse: Vision, Opportunities, and Challenges. Pers Ubiquit Comput 2023, 27, 1811–1827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Paschalidou, S. Technology-Mediated Hindustani Dhrupad Music Education: An Ethnographic Contribution to the 4E Cognition Perspective. Educ. Sci. 2024, 14, 203. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14020203

Paschalidou S. Technology-Mediated Hindustani Dhrupad Music Education: An Ethnographic Contribution to the 4E Cognition Perspective. Education Sciences. 2024; 14(2):203. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14020203

Chicago/Turabian StylePaschalidou, Stella. 2024. "Technology-Mediated Hindustani Dhrupad Music Education: An Ethnographic Contribution to the 4E Cognition Perspective" Education Sciences 14, no. 2: 203. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14020203

APA StylePaschalidou, S. (2024). Technology-Mediated Hindustani Dhrupad Music Education: An Ethnographic Contribution to the 4E Cognition Perspective. Education Sciences, 14(2), 203. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14020203