The Training of Flamenco Dance Teachers of the Escuela Sevillana (Sevillian School): From Practical Experience to the Practice of Teaching

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Concepts and Literature Review

2.1. Construction of Pedagogical Content Knowledge (PCK): Theory and Developments

- -

- General pedagogical knowledge, or general didactic knowledge: the pedagogical competencies that professionals must have in order to teach. These include the ability to plan a learning programme, to structure the teaching/learning methodology, to use didactic techniques and the ability to handle cultural influences that intervene in teaching;

- -

- Content knowledge: the body of knowledge associated with the subject that teachers must understand in order to be effective. Content knowledge has a direct bearing on the execution of curriculum potential [11] There is a close relationship between content knowledge and PCK;

- -

- Contextual knowledge: This includes everything that forms the context of teaching, from the classroom, the curriculum and also the student, as the recipient of the content of teaching.

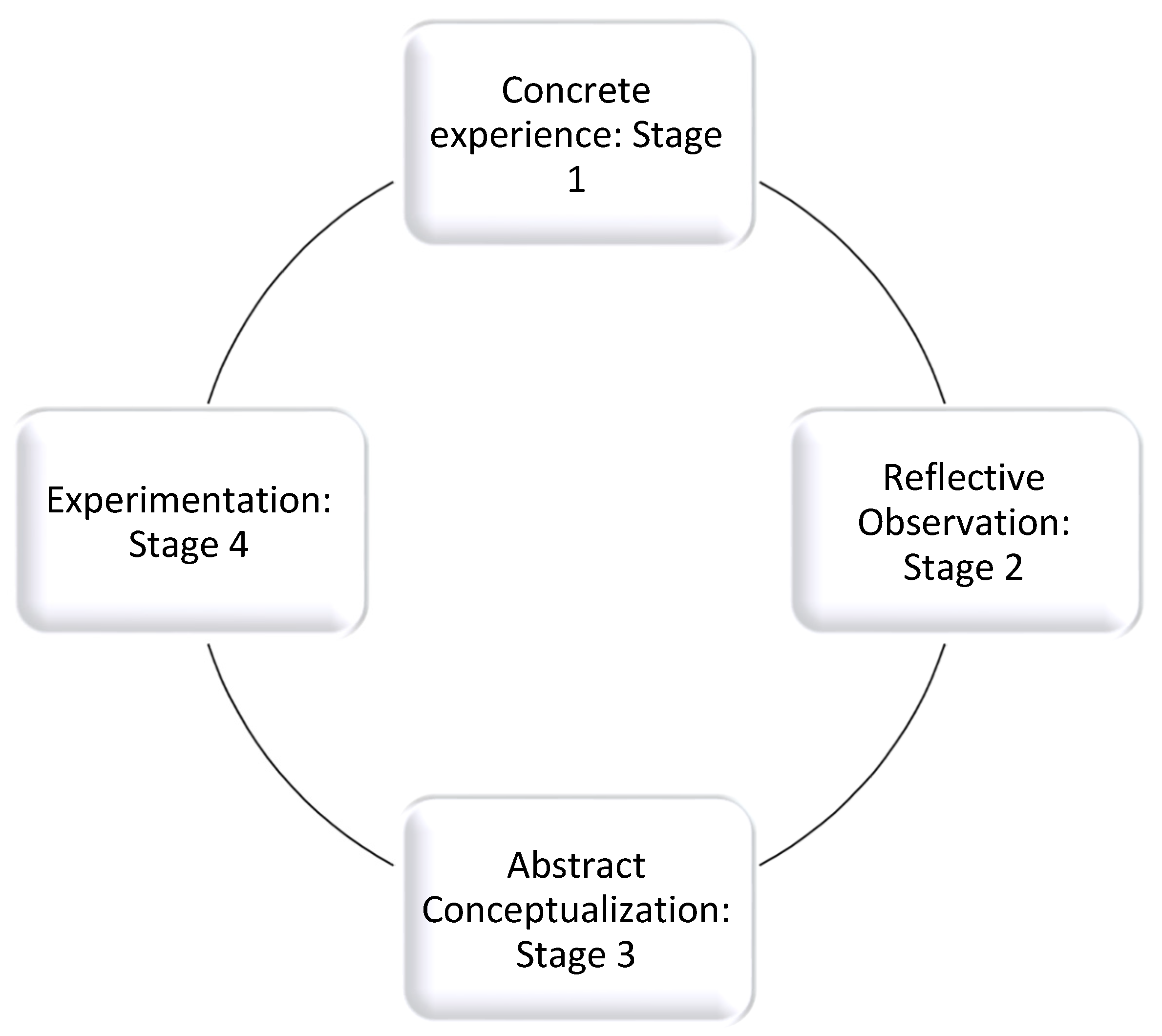

2.2. The Experiential Learning Cycle

2.3. The Construction of PCK in Flamenco Dance Teachers

To make practice the core of the curriculum of teacher education requires a shift from a focus on what teachers know and believe to a greater focus on what teachers do. This does not mean that knowledge and beliefs do not matter but, rather, that the knowledge that counts for practice is that entailed by the work[34] (p. 503).

Reflective practice is hard to teach in isolation, as it has to happen in the context of an event. We have to reflect about something. Reflective practice is often conflated with reflexivity, which can be thought of as the next step on from reflection, as it implies a change in practice as a result of reflecting[26] (p. 20).

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Research Objectives

- -

- General objective:

- -

- Specific objectives:

3.2. Research Design and Procedure

3.3. Selection of Subjects

3.4. Data Collection Instruments

3.5. Techniques and Data Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Career Path/Training of the Interviewees

I.B.: “…es que yo todavía no había terminado mi carrera, era alumna y docente a la vez”. (I hadn’t even finished studying, I was a student and a teacher at the same time).

4.2. Initiation into Teaching

A.M.: “…imagínate que yo tenía 12 años y allí había alumnas, eh, muchísimo mayores que yo, claro. Entonces, claro, es una niña, está allí dando sus prácticas de clase. Pues claro, era como de risa, la verdad”. (Imagine it, I was twelve years old and there were students there, well, a lot older than I was, obviously. So, of course it’s, ‘she’s [just] a girl, there she is giving practical classes’. Of course, it was a bit of a joke really).

I.B.: “Empecé a dar clases sin plantearme muy bien cuál era mi metodología en absoluto. Claro, simplemente, pues imagino que empezaba. Empezaría imitando un poco lo que yo he recibido”. (I started to give classes without really thinking about my methodology at all. Obviously, simply, well, I imagine I just started. I would have started by imitating a bit of what I had been taught).

C.A.: “Me ponía en el lugar del alumno, yo como alumna, yo como a mí, cómo me gustaría que me explicase, yo cómo entendería eso? Siempre me he puesto en el lugar del alumno, siempre era muy jovencita y todavía era alumna, ya que creo que eso también es importante”. (I put myself in the pupil’s place, with me as the pupil, and me as me; how would I like it to be explained to me, how would I understand that? I have always put myself in the pupil’s place, I was always very young and still a pupil, because I think that that too is important).

R.C.: “Yo me valgo de mi conocimiento natural. Sabe de lo que se ha hecho siempre en casa. Verdad que yo no he seguido nunca un método. Ha sido todo visual y lo que he ido poniendo en orden conmigo. Yo sí que es verdad que yo siempre que me enfrento a una clase me pongo en el plano del alumno antes que todo ¿Qué me gustaría qué necesitaría para que me entienda?” (I make use of my native knowledge. You know about what has always been done at home. I have never really followed a method. It’s all been visual and what I’ve been putting together myself. Certainly, whenever I am in front of a class, I always put myself on the student’s level before anything else. What would I like, what would it take to understand me?)

C.A.: “Pues yo me he hecho profesora sin darme cuenta. A mí nadie, a mí nadie ha entrado conmigo y me ha dicho Tienes que aplicar esto, tú tienes que hacer esto, tiene que. A mí nadie me enseñaba eso. Yo solita. Poco a poco, viendo”. (Well, I became a teacher without realizing it. Nobody, nobody has ever come up to me and told me ‘You have to apply this, you have to do that, you have to …’ Nobody taught me that. It was just me on my own. Little by little, by looking).

4.3. Role as Teacher

A.M.: “te tienes que adaptar como te adaptas en la vida a cualquier situación, porque te tienes que adaptar, pero realmente es muy difícil. Es muy difícil eh!” (You have to adapt the way you have to adapt to any situation in life, because you have to adapt, but it is really very difficult. It’s very difficult, you know!).

M.M.: “el conocimiento que tenga el alumno lo tiene que aparcar. Fíjate que todo lo contrario de lo que la gente cree que mira tiene que aparcar todos sus conocimientos y ahora yo le voy a enseñar otra técnica más. Entonces, para que amplíe su conocimiento”. (Any knowledge the pupil has, they’ve got to put to one side. You see, it’s like the very opposite of what people think they have to look at, they have to put everything they know to one side, and now I’m going to show them another technique. So, they can broaden their knowledge).

R.C: “yo lo único que cambio es cuando me cambia la gente que tengo detrás, según el nivel y según. Lo que pasa es que eso de los niveles es relativo” (Me, the only thing I change is when the people behind me change, depending on their level and so on. The thing about levels is that they are relative).

C.A.: “yo siempre intentaba organizarlo como yo, como yo lo hacía en mis clases personales. Pero sí es verdad que bueno, que siempre el alumno, el alumno, el que te va marcando un poquito la pauta, el nivel, el nivel que tenga esa clase en ese momento, después, individualmente, cada alumno, claro, el alumno, el que te va marcando un poquito la pauta”. (I always used to try and organise it the way, the way I used to do it in my private classes. But it’s also true that, well, it’s always the student, the student, who sets your standard to some extent, the level, the level of that class at that time, and after that, each individual student, obviously, the student is the one who continues to set your standard).

A.M.: “porque yo la verdad que gracias a lo a la experiencia, no, a lo que tú vas viviendo como la parte docente, si vas aprendiendo con los años, o sea, no tiene nada que ver. Cuando yo empecé a dar clases a como actualmente he. Tú en parte. No, no tiene absolutamente nada que ver” (…) “tú eso lo tienes intrínseco, porque como tú, como tu educación no, la persona que tiene una educación ahora cambia de a otra y y se tiene que adaptar. Entonces yo creo que es un poco eso”. (Because, honestly, it is thanks to experience, to what I have been going through as a teacher, learning over the years. In other words, what I can say is that the teacher I was when I started out has nothing to do with who I am now. No, it has absolutely nothing to do with it” (…) “You’ve got it inside you, like your education, right. So, I think it’s a bit like you are unconsciously copying what you have learnt and that’s what you do when you are a teacher).

A.G.: “Y también hay una etapa de estancamiento. También hay un momento en el que necesitas, que es verdad, que estás avanzando, pero tú ves que necesitas más. Yo creo que todas hemos pasado por eso y ese es el momento en el que tú vuelves a tomar clase o formarte. De algún modo te reciclas”. (And there’s also a period of stagnation. There is also a time when what you need, it’s true, you are making progress, but you can see that you need more. I think we’ve all been through that, and that’s the time when you go back to take a class or get some training. Somehow you update yourself).

C.A.: “tengo que decir que cuando hice lo del módulo del superior, sí, sí es verdad que había algunas cosas que me ayudaron mucho bien, me ayudaron mucho, por ejemplo, lo de lo de realizar una unidad didáctica. Eso sí es verdad que yo inconscientemente ya no tengo la necesidad de escribirla y del objetivo y del contenido no tengo necesidad. Pero sí es verdad que eso me ayuda a, por ejemplo, a dirigir, como tener un guion”. (I must say that when I did the higher education module, yes, yes, there were some things that helped me a lot, they helped me a lot, for example, the thing about creating a didactic unit. It’s true that I don’t consciously need to write it down anymore, and the objective and the content, I don’t need that. But yes, it does help me to, for example, direct the class, like having a script).

5. Discussion and Conclusions

“La experiencia práctica es una de las fuentes más importantes en el aprendizaje docente; a medida que el docente conoce nuevos casos y situaciones va profundizando y cualificando su saber práctico. Cuando el docente adquiere el hábito de reflexionar su práctica logra que ésta se convierta en fuente y origen de conocimiento”.

Practical experience is one of the most important sources of teacher learning; as teachers encounter new cases and situations, they deepen and refine their practical knowledge. When teachers acquire the habit of reflecting on their practice, it becomes a source and origin of knowledge[45] (p. 10).

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Resolución de 9 de Noviembre de 2011, de la Dirección General de Bienes Culturales, por la que se Incoa el Procedimiento para la Inscripción en el Catálogo General del Patrimonio Histórico Andaluz, como Bien de Interés Cultural, la Actividad de Interés Etnológico, la Escuela Sevillana de Baile, en Sevilla, (Boletin Oficial de la Junta de Andalucía, BOJA no. 241). 12 December 2011. Available online: https://www.juntadeandalucia.es/boja/2011/241/28 (accessed on 1 June 2023).

- Decreto 518/2012, por el que se Inscribe en el Catálogo General del Patrimonio Histórico Andaluz, como Bien de Interés Cultural, la Actividad de Interés Etnológico Denominada Escuela Sevillana de Baile Flamenco, (Boletin Oficial de la Junta de Andalucía, BOJA, no. 220). 9 November 2012, p. 29. Available online: https://www.juntadeandalucia.es/boja/2012/220/BOJA12-220-00004-18273-01_00016485.pdf (accessed on 23 February 2023).

- Ley 4/2023, de 18 de Abril, Andaluza de Flamenco. Boletin Oficial de la Junta de Andalucía, BOJA número 75. 21 April 2023. Available online: https://www.juntadeandalucia.es/boja/2023/75/1 (accessed on 25 May 2023).

- Longley, A.; Kensington-Miller, B. Visibilising the Invisible: Three Narrative Accounts Evoking Unassessed Graduate Attributes in Dance Education. Res. Danc. Educ. 2020, 21, 18–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derin, A.; Ozlem, K.; Gokce, K. The Pedagogical Content Knowledge Development of Prospective Teachers through an Experiential Task. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2010, 2, 421–1425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, H.T.M.; Yang, H. Learning to Become a Teacher in Australia: A Study of Pre-service Teachers’ Identity Development. Aust. Educ. Res. 2018, 45, 625–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de las Heras, B. Transformación del paradigma educativo del baile flamenco. Espacios 2018, 39, 1–3. [Google Scholar]

- Shulman, L.S. Those Who Understand: Knowledge Growth in Teaching. Educ. Res. 1986, 15, 4–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azam, S. Distinguishing Topic-specific Professional Knowledge From Topic-Specific PCK: A Conceptual Framework. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Educ. 2019, 14, 281–296. [Google Scholar]

- Garcia, C.M. Cómo conocen los profesores la materia que enseñan. Algunas contribuciones de la investigación sobre conocimiento didáctico del contenido. In Proceedings of the Las Didácticas Específicas en la Formación del Profesorado, Santiago, Chile, 6–10 July 1993; pp. 151–186. [Google Scholar]

- Demuth Mercado, P.B. La Construccion del Conocimiento Didactico en Profesores Universitarios. Ph.D. Thesis, Universidad de Sevilla, Sevilla, Spain, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Da-Silva, C.; Mellado, V.; Ruiz, C.; Ariza, R. Evolution of the conceptions of a secondary education biology teacher: Longitudinal analysis using cognitive maps. Sci. Educ. 2007, 91, 461–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nilsson, P. Teaching for Understanding: The complex nature of pedagogical content knowledge in pre-service education. Int. J. Sci. Educ. 2008, 30, 1281–1299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yiğit, A. An investigation of elementary teachers’ pedagogical content knowledge for socioscientific argumentation: The effect of a learning and teaching experience. Sci. Educ. 2021, 105, 743–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norville, K.; Park, S. The Impact of the Cooperating Teacher on Master of Arts in Teaching Preservice Science Teachers’ Pedagogical Content Knowledge. J. Sci. Teach. Educ. 2021, 32, 444–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hume, A.; Cooper, R.; Borowski, A. Repositioning Pedagogical Content Knowledge in Teachers’ Knowledge for Teaching Science; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Carlson, J.; Daehler, K.R.; Alonzo, A.C.; Barendsen, E.; Berry, A.; Borowski, A.; Carpendale, J.; Kam Ho Chan, K.; Cooper, R.; Friedrichsen, P.; et al. The Refined Consensus Model of Pedagogical Content Knowledge in Science Education. In Repositioning Pedagogical Content Knowledge in Teachers’ Knowledge for Teaching Science; Hume, A., Cooper, R., Borowski, A., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2019; pp. 77–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keller, M.M.; Neumann, K.; Fischer, H.E. The impact of physics teachers’ pedagogical content knowledge and motivation on students’ achievement and interest. J. Res. Sci. Teach. 2017, 54, 586–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolb, D.A. Experiential Learning; Prentice Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Samper, A.; Ramírez, A. Diseño de una Propuesta Pedagógica de Educación para la Seguridad Vial Estructurada Bajo el Modelo de Aprendizaje Experiencial; Corporación Universitaria Minuto de Dios: Bogota, Colombia, 2014; Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/10656/2918 (accessed on 4 October 2023).

- Valdés, L.; Luna, S. Cómo Aprendemos de los Referentes Visuales en el Diseño? Aproximación Desde la Teoría del Aprendizaje Experiencial de Kolb, México. 2017. Available online: https://www.academia.edu/download/57768144/Como_aprendemos_de_los_Referentes.pdf (accessed on 16 December 2022).

- Olson, J.A.L. Arts Education in a Teacher Education Curriculum: A Model Based on Comparative Analysis of Arts Education Theories. Ph.D. Thesis, University of North Dakota, Grand Forks, ND, USA, 1982. Available online: https://www.proquest.com/dissertations-theses/arts-education-teacher-curriculum-model-based-on/docview/303230043/se-2 (accessed on 16 December 2022).

- Esola, L. The effects of Experiential Learning Processes in Art on Creative Thinking among Preservice Education Majors: A Systematic Literature Review. Ph.D. Thesis, The Pennsylvania State University, State College, PA, USA, 2022. Available online: https://www.proquest.com/dissertations-theses/effects-experiential-learning-processes-art-on/docview/2812053706/se-2 (accessed on 3 November 2023).

- Fuentes Olavarría, D. Aportes del aprendizaje experiencial a la formación de estudiantes de enfermería en psiquiatría: Estudio cualitativo. Rev. Mex. Investig. Educ. 2019, 24, 833–851. Available online: http://www.scielo.org.mx/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1405-66662019000300833&lng=es&tlng=es (accessed on 17 January 2023).

- Espinar Álava, E.M.; Vigueras Moreno, J.A. El aprendizaje experiencial y su impacto en la educación actual. Rev. Cuba. Educ. Super. 2020, 39, e12. Available online: http://scielo.sld.cu/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0257-43142020000300012&lng=es&tlng=es (accessed on 27 May 2023).

- Petsilas, P.; Leigh, J.; Brown, N.; Blackburn, C. Creative and Embodied Methods to Teach Reflections and Support Students’ Learning. Res. Danc. Educ. 2019, 20, 19–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chua, S.L.; Welch, G.F. A lifelong perspective for growing music teacher identity. Res. Stud. Music Educ. 2020, 43, 329–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agathangelou, S.A.; Charalambous, C.Y. Is Content Knowledge Pre-requisite of Pedagogical Content Knowledge? An Empirical Investigation. J. Math. Teach. Educ. 2021, 24, 431–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, C. The Role of Subject Knowledge in Primary Prospective Teachers’ Approaches to Teaching the Topic of Area. J. Math. Teach. Educ. 2012, 15, 187–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruces, C. Una Primera Aproximación a las Metodologías de Estudio del Flamenco. Perspectivas, Necesidades y Líneas de Trabajo. In Historia del Flamenco; Ediciones Tartessos: Sevilla, Spain, 2002; pp. 63–107. ISBN 84-7663-073-5. [Google Scholar]

- Navarro, J.L.; Pablo, E. El Baile Flamenco: Una Aproximación Histórica; ALMUZARA: Leon, Spain, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- de las Heras, B. La enseñanza del baile flamenco en las academias de Sevilla: El legado de tres generaciones de maestras y maestros. (1940–2010). Ph.D. Thesis, Universidad de Sevilla, Sevilla, Spain, 2018. Available online: https://idus.us.es/handle/11441/81507#.YenXVAR5Yk4.mendeley (accessed on 28 September 2023).

- Abdelmaji, N.; Jomaa, H.; Majdoub, S.; Abdelmajid, N.; Kpazaï, G. Sports Expertise as a Predisposing Factor to Decisional Process Among Physical Education Teachers: A Case Study. Eur. J. Educ. Sci. 2020, 7, 1857–6036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loewenberg, D.; Forzani, F.M. The Work of Teaching and the Challenge for Teacher Education. J. Teach. Educ. 2009, 60, 497–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omingo, M. Lecturers Learning to Teach: The Role of Agency. Int. J. Acad. Dev. 2019, 24, 122–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calderhead, J. Reflective Teaching and Teacher Education. Teach. Teach. Educ. 1989, 5, 43–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewey, J. How We Think: A Restatement of the Relation of Reflective Thinking to the Education Process; Pollard, A., Ed.; D.C. Heath & Co Publishers: Boston, MA, USA, 1933. [Google Scholar]

- Edwards, R.; Nicoll, K. Expertise, Competence and Reflection in the Rhetoric of Professional Development. Br. Educ. Res. J. 2006, 32, 115–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeyda, L. Arrojados en la acción. Aprender a enseñar en la experiencia de práctica profesional. Estud. Pedagógicos 2018, 42, 11–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grossman, P.; Compton, C.; Igra, D.; Ronfeldt, M.; Shahan, E.; Williamson, P.W. Teaching Practice: A Cross-Professional Perspective. Teach. Coll. Rec. 2009, 111, 2055–2100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loureiro, S.R.C. Ensinar a Aprender, Aprender a Ensinar. Ph.D. Thesis, Polytechnic Institute of Porto, Porto, Portugal, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Coral, M.; Álvarez, A.; Valdés, J. Tratado de la Bata de Cola; Alianza Editorial: Madrid, Spain, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- García, P. Andaluzas de Hoy: Mujeres que Abren Caminos en el Arte y la Cultura; Araceli, E., Ángeles Sallé, M., Eds.; Diputación de Córdoba: Cordoba, Spain, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Vaillant, D.; Marcelo, C. Formación Inicial del Profesorado: Modelo Actual y Llaves para el Cambio. REICE Rev. Iberoam. Sobre Calid. Efic. Cambio Educ. 2021, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arias, L. La Construcción del Conocimiento Didáctico del Contenido (CDC) en la Práctica de un Docente de Morfofisiología en un Programa de Enfermería. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Antioch, Culver City, CA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Schubert, V.M.; Medina, J.L.; Lenise do Prado, M. The Construction Process of Pedagogical Knowledge Among Nursing Professors. Rev. Lat.-Am. Enferm. 2011, 19, 421–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baneviciutė, B. Dance Teacher Education: Programme Analysis and Students’ Perceptions. Discourse Commun. Sustain. Educ. 2013, 1, 64–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerrero Bejarano, M.A. La investigación cualitativa. INNOVA Res. J. 2016, 1, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández Sampieri, R.; Fernández Collado, C.; Baptista Lucio, M.d.P. Metodología de la Investigación, 5th ed.; Mares Chacón, J., Ed.; Mc 99 Graw Hill: New York, NY, USA, 2010; Available online: http://www.casadellibro.com/libro-metodologia-de-la-investigacion-5-ed-incluye-cdrom/9786071502919/1960006 (accessed on 16 December 2022).

- Colás, P.; Rebollo, M.A. Evaluación de Programas: Una Guía Práctica, 2nd ed.; Kronos: Sevilla, Spain, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez, C.M. A Method for Experiential Learning and Significant Learning in Architectural Education via Live Projects. Arts Humanit. High. Educ. 2018, 17, 279–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gleason Rodríguez, M.A.; Rubio, J.E. Implementación del aprendizaje experiencial en la universidad, sus beneficios en el alumnado y el rol docente. Rev. Educ. 2020, 44, 264–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ausubel, D. Educational Psychology: A Cognitive View; Rinehart & Winston: New York, NY, USA, 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez, R. Los modelos de aprendizaje de Kolb, Honey y Mumford: Implicaciones para la educación en ciencias. Sophia 2018, 14, 51–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padalkar, S.; Ramchand, M.; Rafikh, S.; Vijaysimha, I. Science Education: Developing Pedagogical Content Knowledge; Routledge: London, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar]

| Phase 1 | Transcription | Conversion of approximately 12 h of recorded interviews into text. |

| Phase 2 | Categorisation | Conceptual classification of a series of concepts associated with the dimensions studied. |

| Phase 3 | Codification | Assignment of different codes to the categories determined previously to facilitate the extraction of results and allow them to be combined in a simpler and more organised way for the subsequent interpretation of the data. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cortés-Vázquez, M.; Llorent-Bedmar, V. The Training of Flamenco Dance Teachers of the Escuela Sevillana (Sevillian School): From Practical Experience to the Practice of Teaching. Educ. Sci. 2024, 14, 188. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14020188

Cortés-Vázquez M, Llorent-Bedmar V. The Training of Flamenco Dance Teachers of the Escuela Sevillana (Sevillian School): From Practical Experience to the Practice of Teaching. Education Sciences. 2024; 14(2):188. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14020188

Chicago/Turabian StyleCortés-Vázquez, Macarena, and Vicente Llorent-Bedmar. 2024. "The Training of Flamenco Dance Teachers of the Escuela Sevillana (Sevillian School): From Practical Experience to the Practice of Teaching" Education Sciences 14, no. 2: 188. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14020188

APA StyleCortés-Vázquez, M., & Llorent-Bedmar, V. (2024). The Training of Flamenco Dance Teachers of the Escuela Sevillana (Sevillian School): From Practical Experience to the Practice of Teaching. Education Sciences, 14(2), 188. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14020188