Implementation of Innovations in Skill Ecosystems: Promoting and Inhibiting Factors in the Indian Context

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Context: Skill Development in India

Description of Research Object: Advancement of Skill Development in Indian Districts

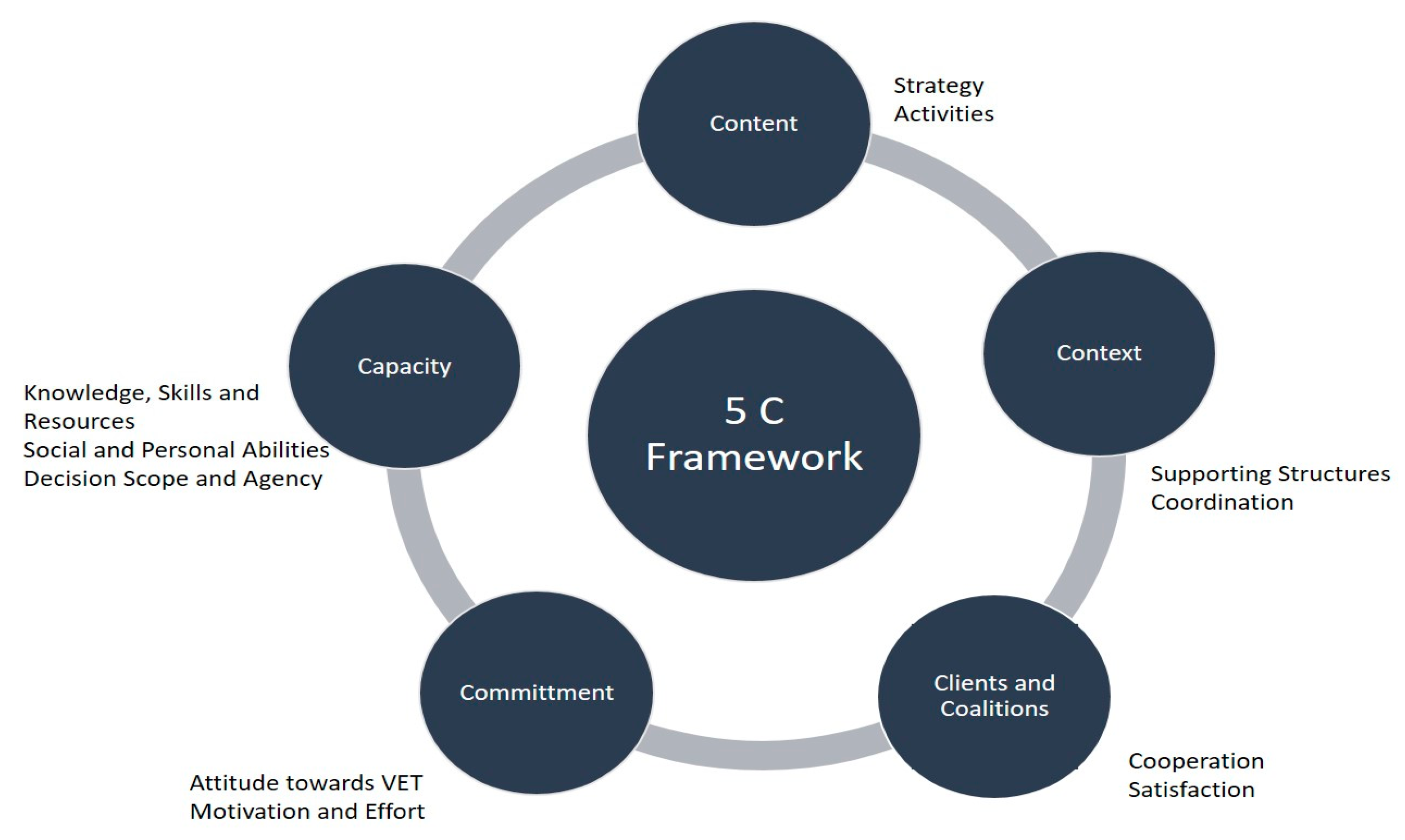

3. Theoretical Approaches to Implementation

5C Model—Factors That May Impact Implementation

4. Methodology

5. Results

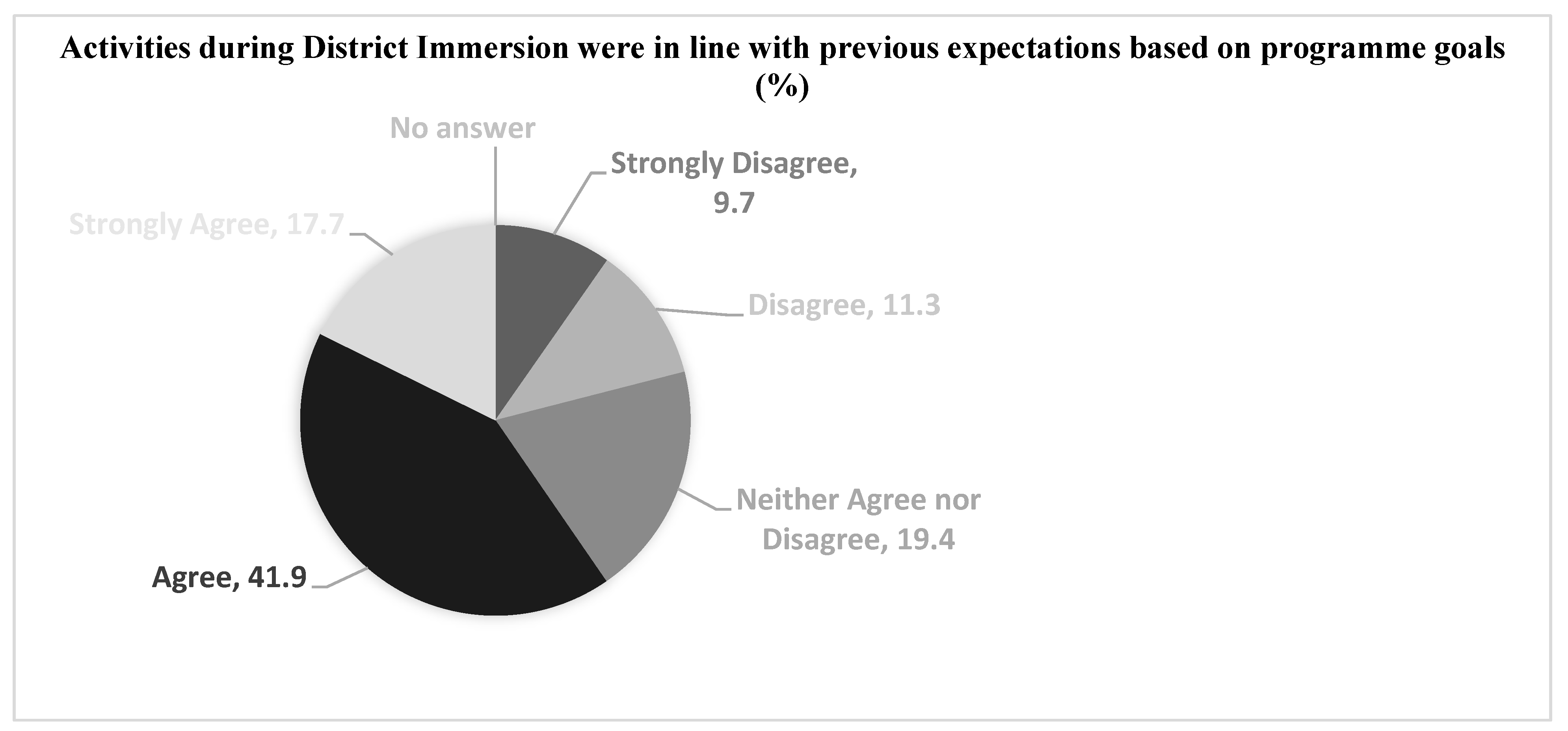

5.1. Content of Policy

5.2. Context

5.3. Commitment

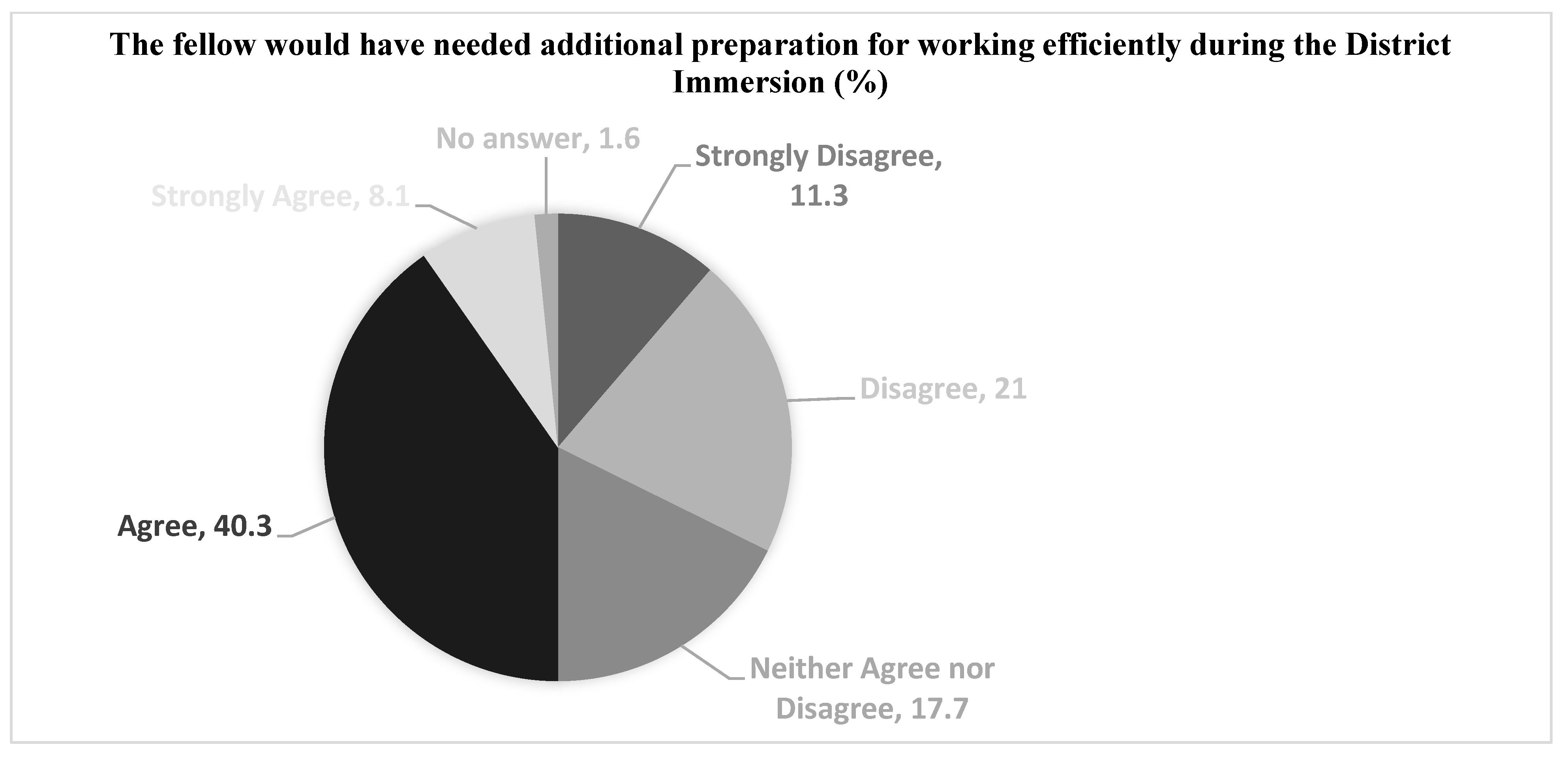

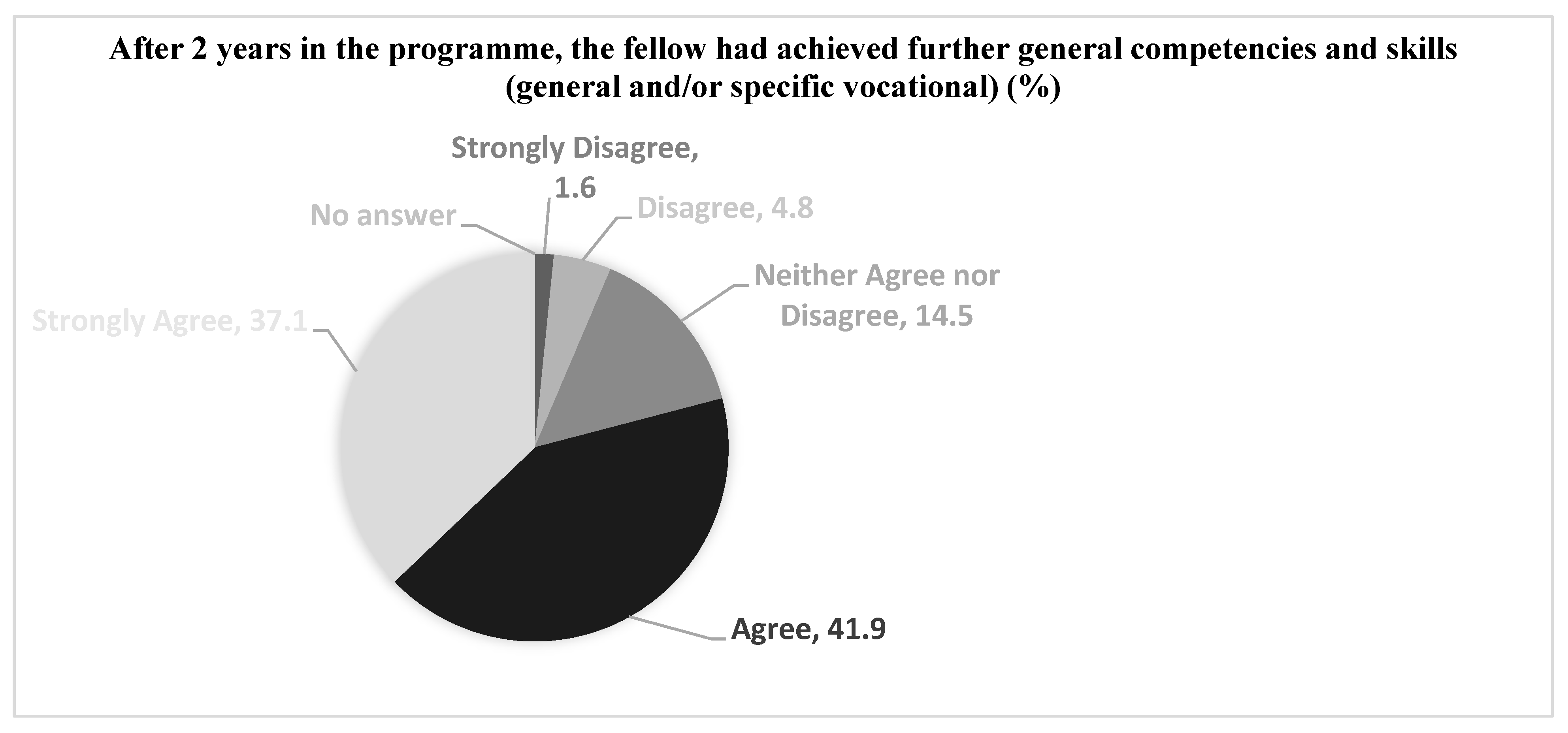

5.4. Capacity

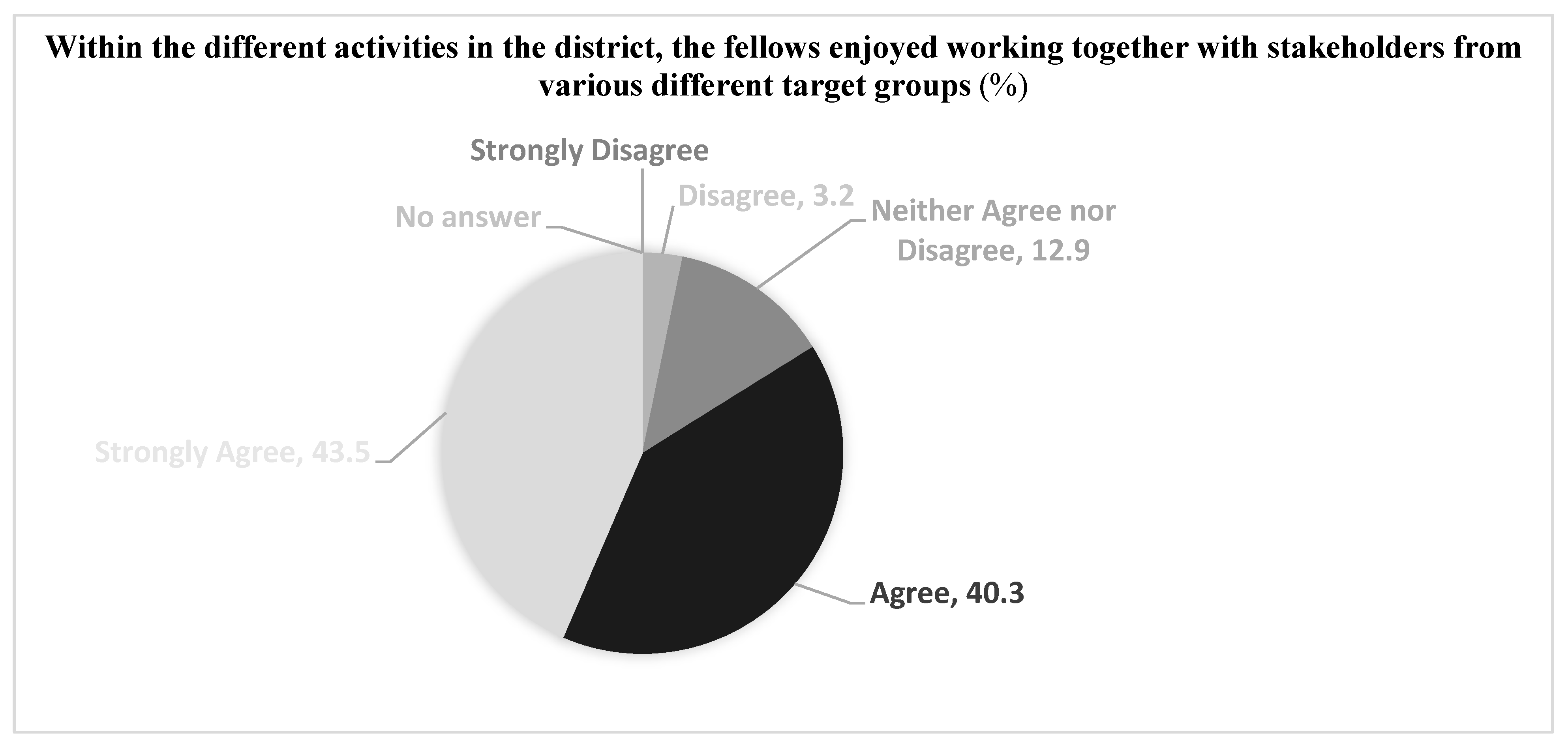

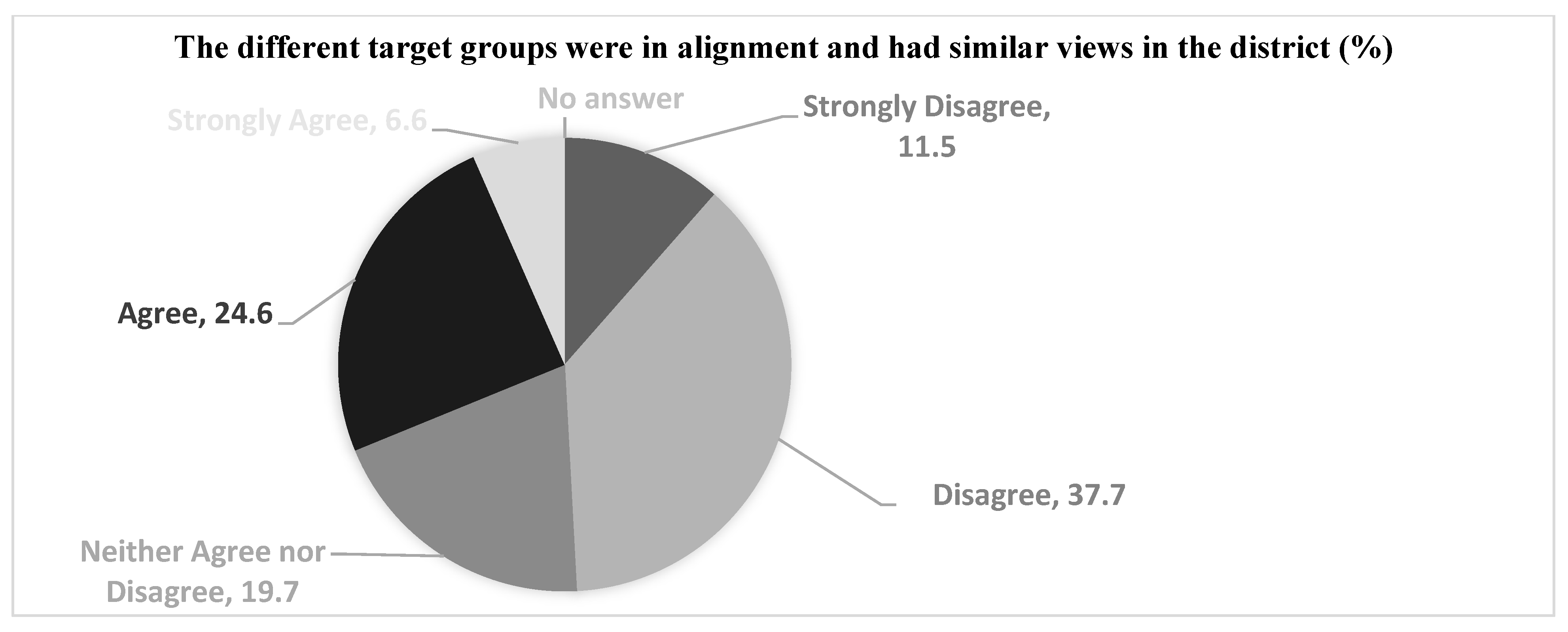

5.5. Clients and Coalitions

6. Discussion

“The concept of decentralisation was a supporting factor for my activities”

“There is a huge disconnect between the existing trades and the aspirations of youth/ aspirants. Decentralisation could resolve it”.

“The district administration were not clear of the policy and were unclear about our roles. We worked across departments and not just skilling”.

“My mentor in the district changed thrice. The second one was very helpful while others were not very supportive”.

“Support differed from mentor to mentor (they frequently get transferred)”.

“The district administration was not very welcoming due to their hectic work schedules”.

“No support. I was in the district as an “Alien”

“Level of support was lukewarm at best. They did not stop me from pitching initiatives but also did not actively provide help/ support”.

“There was no interest in taking up additional initiatives apart from regular work”.

“District skill development officer not very interested”.

“Support from government staff was not enough initially but later on we managed”.

“Skill development is not priority to district administration”

“There was a step-motherly treatment of skill development”.

“My most unsuccessful activity was working on strengthening the District Skill Committee. Unless there is … a line department for skills, DSC will not achieve convergence. All members have their own roles and responsibilities, they receive mandates from individual directorates. So DSC doesn’t have decision making or financial authorities”

“Delays in government paperwork were problematic”.

“There was lack of support from administration for fear of owning a project and related fine”.

“Employers think skill development activities undertaken by the government are of poor quality, irrelevant to the market trends, incompetent etc. They think candidates often need to be re-trained by the employers”.

“Indifferent due to lack of constitutional power on our part”.

“A challenge was conflict resolution between different actors”.

“There were financial constraints to kick start new initiatives”.

“DSC meetings. Departments were refusing to meet due to lack of availability of funds”

“Lack of financial funds and human resources in district”.

“Engaging and dealing with power dynamics in the government”.

“Cultural hindrances constituted hurdles”.

“Cultural conditions were challenging”.

“Very poor system and considered much below the standards of traditional education systems”.

“People trained in vocational streams are often somewhat illiterate. Vocational education is an after-thought and most vocationally trained people barely get by”.

7. Conclusions and Outlook

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Clayton, B.; Harris, R. New Strategies for Strengthening VET: Challenges and Opportunities. Int. J. Train. Res. 2019, 17, 199–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paterson, A. Perspectives on programmes, projects and policies in TVET colleges. In Change Management in TVET Colleges: Lessons Learnt from the Field of Practice; Kraak, A., Paterson, A., Boka, K., Eds.; African Minds, JET Education Service: Johannesburg, South Africa, 2016; pp. 7–23. Available online: https://www.africanminds.co.za/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/JET-TVET-text-and-cover-web-final-1.pdf (accessed on 15 September 2024).

- Vogelsang, B.; Röhrer, N.; Pilz, M.; Fuchs, M. Actors and Factors in the International Transfer of Dual Training Approaches: The Coordination of Vocational Education and Training in Mexico from a German Perspective. Int. J. Train. Dev. 2022, 26, 646–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atchoarena, D.; Grootings, P. Overview: Changing National VET Systems through 6. Reforms. In International Handbook of Education for the Changing World of Work; Maclean, R., Wilson, D., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2009; pp. 365–378. [Google Scholar]

- Caves, K.M.; Baumann, S. Getting There from Here: A Literature Review of VET Reform Implementation; KOF Working Papers 441; ETH Zurich: Zurich, Switzerland, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonoli, L.; Gonon, P. Challenges, Future and Policy Orientations: The 1960s−1970s as Decisive Years for Swiss Vocational Education and Training. Int. J. Res. Voc. Ed. Train-(IJRVET) 2023, 10, 340–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGrath, S.; Lugg, R. Knowing and Doing Vocational Education and Training Reform: Evidence, Learning and the Policy Process. Int. J. Ed. Dev. 2012, 32, 696–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arribas, M.G.; Papadakis, N. Governance Arrangements in Vocational Education and Training in ETF Partner Countries: Analytical Overview 2012–2017; ETF: Turin, Italy, 2019; Available online: https://www.etf.europa.eu/sites/default/files/2019-02/VET%20governance%20in%20ETF%20partner%20countries%202012-17.pdf (accessed on 1 December 2024).

- Regel, J.; Ramasamy, M.; Pilz, M. Ownership in International Vocational Education and Training Transfer: The Example of Quality Development in India. Int. J. Train. Dev. 2022, 26, 664–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biemans, H.; Nieuwenhuis, L.; Poell, R.; Mulder, M.; Wesselink, R. Competence-based VET in the Netherlands: Background and Pitfalls. J. Vocat. Educ. Train. 2004, 56, 523–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cedefop, Overview of National Qualifications Framework Developments in Europe 2020; Publications Office: Luxembourg, 2021; Available online: http://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2801/31688 (accessed on 1 December 2024).

- Mehrotra, S. The National Skills Qualification Framework in India: The Promise and the Reality; Working Paper, No. 389; Indian Council for Research on International Economic Relations (ICRIER): Delhi, India, 2020; Available online: https://www.econstor.eu/bitstream/10419/242868/1/Working-Paper-389.pdf (accessed on 1 December 2024).

- Caves, K.M.; Oswald-Egg, M.E. Storming and Forming: A Case Study of Education Policy Implementation; KOF Working Papers 477; ETH Zurich: Zurich, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Althaus, C.; Ball, S.; Bridgman, P.; Davis, G.; Threlfall, D. The Australian Policy Handbook: A Practical Guide to the Policymaking Process, 7th ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Pilz, M. International Transfer of Vocational Education and Training: A Literature Review. J. Vocat. Educ. Train. 2023, 75, 185–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pilz, M. Typologies as a Tool to Assess Reforms in Vocational Education and Training Systems. In Governance Revisited: Challenges and Opportunities for Vocational Education and Training; Bürgi, R., Gonon, P., Eds.; Peter Lang AG, Internationaler Verlag der Wissenschaften: Bern, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 331–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stockmann, R. The Transfer of Dual Vocational Training: Experiences from German Development Cooperation. In The Challenges of Policy Transfer in Vocational Skills Development; Maurer, M., Gonon, P., Eds.; Peter Lang: Bern, Switzerland, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmes, K. The Reform and Governance of Public TVET Institutions: Comparative Experiences. In International Handbook of Education for the Changing World of Work; Maclean, R., Wilson, D., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2009; pp. 905–919. [Google Scholar]

- Viennet, R.; Pont, B. Education Policy Implementation: A Literature Review and Proposed Framework; OECD Education Working Papers, No. 162; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pilz, M.; Regel, J. Vocational Education and Training in India: Prospects and Challenges from an Outside Perspective. Margin J. Appl. Econ. Res. 2021, 15, 101–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, S.; Pilz, M. India’s Labour Market Challenges: Employability of Young Workforce from the Perspective of Supply and Demand. Prospects 2024, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyer, C. Decentralisation to Improve Teacher Quality? District Institutes of Education and Training in India. Compare 2005, 35, 139–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. Vocational Education First. State of the Education Report for India 2020; Technical and Vocational Education and Training (TVET); UNESCO: New Delhi, India, 2020; Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000374969.locale=en (accessed on 16 September 2024).

- UNESCO. Strategy for Technical and Vocational Education and Training (TVET), (2016–2021); UNESCO: Paris, France, 2016; Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000245239 (accessed on 15 September 2024).

- NSDC (National Skill Development Cooperation). An Overview of Technical Vocational Education and Training Ecosystem in India. NSDC. 2020. Available online: https://skillsip.nsdcindia.org/sites/default/files/kps-document/TVET%20Landscape%20and%20Stakeholders_February2020_0.pdf (accessed on 15 September 2024).

- Ministry of Skill Development and Entrepreneurship (MSDE). Annual Report 2022–2023. 2023. Available online: https://www.msde.gov.in/sites/default/files/2023-09/Final%20Skill%20AR%20Eng.pdf. (accessed on 16 May 2024).

- Wessels, A.; Pilz, M. International Handbook of Vocational Education and Training; Federal Institute for Vocational Education and Training: Bonn, Germany, 2018; Available online: https://www.bibb.de/dienst/publikationen/en/9574 (accessed on 16 September 2024).

- Ajithkumar, U.; Pilz, M. Attractiveness of Industrial Training Institutes (ITI) in India: A Study on ITI Students and Their Parents. Educ. Train. 2019, 61, 153–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jambo, S.; Pilz, M. Perceptions of Teachers in Industrial Training Institutes: An Exploratory Study of the Attractiveness of Vocational Education in India. Int. J. Train. Res. 2018, 16, 4–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pilz, M.; Ramasamy, M. Attractiveness of Vocational Education and Training in India: Perspectives of Different Actors with a Special Focus on Employers. In The Standing of Vocational Education and the Occupations It Serves. Professional and Practice-based Learning; Billett, S., Stalder, B.E., Aarkrog, V., Choy, S., Hodge, S., Le, A.H., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 177–199. [Google Scholar]

- Mehrotra, S.; Mehrotra, V.S. Challenges beyond schooling: Innovative models for youth skills development in India. In Transitions to Post-School Life: Responsiveness to Individual, Social and Economic Needs; Pavlova, M., Lee, J.K., Maclean, R., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2018; pp. 13–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neroorkar, S.; Gopinath, P. An Employability Framework for Vocational Education and Training Graduates in India: Insights from government VET institutes in Mumbai. TVET@Asia 2020. Available online: https://tvet-online.asia/15/an-employability-framework-for-vocational-education-and-training-graduates-in-india-insights-from-government-vet-institutes-in-mumbai/ (accessed on 15 September 2024).

- Mehrotra, S. From 5 Million to 20 Million a Year: The Challenge of Scale, Quality and Relevance in India’s TVET. Prospects 2014, 44, 267–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehrotra, S. Technical and Vocational Education and Training in India: Lacking vision, strategy and coherence. In The Routledge Handbook of Education in India; Mehrtra, S., Ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2021; pp. 203–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, M. India’s national skills development policy and implications for TVET and lifelong learning. In The Future of Vocational Education and Training in a Changing World; Pilz, M., Ed.; Springer VS: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2012; pp. 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Skill Development and Entrepreneurship (MSDE). District Skill Committees (DSCs) to Work Closely with the Center to Drive Demand-Driven Skill Development Initiatives. 2018. Available online: https://msde.gov.in/sites/default/files/2020-03/Press%20Release%20_Feb%2018.pdf (accessed on 16 May 2024).

- Mukherji, A.; Kamath, R.; Basu, S.; Das, T. Mahatma Gandhi National Fellowship Programme of Ministry and Skill Development and Entrepreneurship in Collaboration with Indian Institutes of Management; IIM Bangalore: Bangalore, India, 2023; Available online: https://www.iimb.ac.in/sites/default/files/inline-files/02-Nov-MGNF-Book-2023.pdf (accessed on 15 September 2024).

- Young, T.; Lewis, W.D. Educational Policy Implementation Revisited. Educ. Policy 2015, 29, 3–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fixsen, D.; Naoom, S.; Blase, K.; Friedman, R.; Wallace, F. Implementation Research: A Synthesis of the Literature; Louis de la Parte Florida Mental Health Institute: Tampa, FL, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Najam, A. Learning from the Literature on Policy Implementation: A Synthesis Perspective; IIASA Working Papers, WP-95-061; International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis: Luxemburg, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.; Pilz, M. Modularisation in the German VET System: A Study of Policy Implementation. J. Educ. Work 2017, 30, 471–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moir, T. Why Is Implementation Science Important for Intervention Design and Evaluation within Educational Settings? Front. Educ. 2018, 3, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nilsen, P.; Ståhl, C.; Roback, K.; Cairney, P. Never the Twain Shall Meet?—A Comparison of Implementation Science and Policy Implementation Research. Implement. Sci. 2013, 8, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sabatier, P. From Policy Implementation to Policy Change: A Personal Odyssey. In Reform and Change in Higher Education; Gornitzka, Å., Kogan, M., Amaral, A., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2005; pp. 17–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fullan, M. The New Meaning of Educational Change, 4th ed.; Teachers’ College Press: New York, NY, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Bolli, T.; Caves, K.M.; Renold, U.; Buergi, J. Beyond Employer Engagement: Measuring Education-Employment Linkage in Vocational Education and Training Programmes. J. Vocat. Educ. Train. 2018, 70, 524–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J.W.; Creswell, J.D. Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches, 5th ed.; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Deci, E.; Ryan, R.M. Intrinsic Motivation Inventory. 2003. Available online: http://www.psych.rochester.edu/SDT/measures/intrins.html (accessed on 15 September 2024).

- Fritz, W.; Möllenberg, A.; Chen, G. Measuring intercultural sensitivity in different cultural contexts. Intercult. Commun. Stud. 2002, 11, 165–176. Available online: https://digitalcommons.uri.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1019&context=com_facpubs (accessed on 15 September 2024).

- Kanning, U.P.; Böttcher, W.; Herrmann, C. Measuring Social Competencies in the Teaching Profession—Development of a Self-Assessment Procedure. J. Educ. Res. Online 2012, 4, 140–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKenney, S.; Reeves, T.C. Conducting Educational Design Research, 2nd ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Rathidevi, D.; Sudhkaran, M.V. Attitudes of Students towards Vocational Education with Reference to Chennai City. Int. J. Indian Psychol. 2019, 7, 84–93. Available online: https://ijip.in/articles/attitudes-of-students-towards-vocational-education-with-reference-to-chennai-city/ (accessed on 1 December 2024).

- Russo, G.; Serafini, M.; Ranieri, A. Attractiveness Is in the Eye of the Beholder. Empir. Res. Vocat. Educ. Train. 2019, 11, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuckartz, U. Qualitative Text Analysis: A Guide to Methods, Practice and Using Software; SAGE Publications: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Nastasi, B.K.; Hitchcock, J.H. Mixed Methods Research & Culture-Specific Interventions. Program Design and Evaluation; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Billett, S.; Seddon, T. Building Community through Social Partnerships around Vocational Education and Training. J. Vocat. Educ. Train. 2004, 56, 51–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Billett, S.; Ovens, C.; Clemans, A.; Seddon, T. Collaborative Working and Contested Practices: Forming, Developing and Sustaining Social Partnerships in Education. J. Educ. Pol. 2007, 22, 637–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emmenegger, P.; Graf, L.; Trampusch, C. The Governance of Decentralised Cooperation in Collective Training Systems: A Review and Conceptualisation. J. Vocat. Educ. Train. 2019, 71, 21–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falk, I. Leadership in Vocational Education and Training: Developing Social Capital through Partnerships. In Future Research, Research Futures: Proceedings of the Third National Conference of the Australian Vocational Education and Training Research Association (AVETRA), Canberra, Australia, 23–24 March 2000; The Australian Vocational Education and Training Research Association: Alexandria, Australia, 2000; pp. 98–108. [Google Scholar]

- Stockmann, R.; Silvestrini, S. Summary of the Synthesis and Meta-Evaluation Report Technical and Vocational Training; Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit: Bad Honnef, Germany, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Elliot, A.; Fryer, J. The Goal Construct in Psychology. In Handbook of Motivation Science; Shah, J., Gardner, W., Eds.; Guilford Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2018; pp. 365–378. [Google Scholar]

- Pilz, M.; Wiemann, K. Does Dual Training Make the World Go Round? Training Models in German Companies in China, India and Mexico. Vocat. Learn. 2021, 14, 95–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gessler, M. Educational Transfer as Transformation: A Case Study about the Emergence and Implementation of Dual Apprenticeship Structures in a German Automotive Transplant in the United States. Vocat. Learn. 2017, 10, 71–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pierre, J.; Peters, B.G. Governing Complex Societies: Trajectories and Scenarios, 1st ed.; Palgrave Macmillan: Basingstoke, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, P.A.; Soskice, D. An Introduction to Varieties of Capitalism. In Varieties of Capitalism. The Institutional Foundations of Comparative Advantage; Hall, P.A., Soskice, D., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2001; pp. 1–68. [Google Scholar]

- Culpepper, P.D. Creating Cooperation: How States Develop Human Capital in Europe; Cornell University Press: Ithaca, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Regel, I.J.; Pilz, M. Informal Learning and Skill Formation within the Indian Informal Tailoring Sector. Int. J. Train. Res. 2019, 17, 140–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cross, W.; West, J.C. Examining implementer fidelity: Conceptualising and measuring adherence and competence. J. Child. Serv. 2011, 6, 18–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matveev, A. Intercultural Competence in Multicultural Teams. In Intercultural Competence in Organizations: A Guide for Leaders, Educators and Team Players; Matveev, A., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Germany, 2017; pp. 77–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armbruster, L. Cooperation Across Cultures: An Analysis of Intercultural Competence in Development Organizations; IEEE Working Paper 205; University of Bochum: Bochum, Germany, 2014; Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/10419/183559 (accessed on 15 September 2024).

- Keijzer, N.; Klingebiel, S.; Örnemark, C.; Scholtes, F. Seeking Balanced Ownership in Changing Development Cooperation Relationships. Expert Group for Aid Studies (EBA). 2018. Available online: https://eba.se/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/ownership.pdf (accessed on 15 September 2024).

- Bergen, N.; Labonté, R. Everything Is Perfect, and We Have No Problems: Detecting and Limiting Social Desirability Bias in Qualitative Research. Qual. Health Res. 2020, 30, 783–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Govinda, R. Role of Headteachers in School Management in India. Case Studies from Six States; NUEPA: Delhi, India, 2002. [Google Scholar]

| S. No. | Concrete Activities in District Immersion | Responses in Yes (%) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | To engage with and establish networks to different actors (e.g., education and training institutions, employer (representatives), community committees (e.g., CBOs), govt. authorities, etc.) | 82.3% |

| 2 | Understanding aspirations of young people in the district | 77.4% |

| 3 | To bring together actors (e.g., employers, educational institutions, etc.) in the skill development landscape | 80.6% |

| 4 | To develop new programmes | 56.5% |

| 5 | To revise existing measures | 41.9% |

| 6 | To initiate programmes/inventions | 71% |

| 7 | Administrative work in the agency that the fellow was placed in (processing, controlling, etc.) | 41.9% |

| 8 | Organisational activities (planning and realization of meetings, coordination of stakeholders, etc.) | 62.9% |

| 9 | To support in improving the quality of skill training | 59.7% |

| 10 | To improve the outreach of programmes in the district | 59.7% |

| 11 | To mobilize trainees for the training programme | 51.6% |

| 12 | To promote skill development/ upskilling | 75.8% |

| Coordination Amongst Contextual Support Structures | Strongly Disagree | Disagree | Neither Agree nor Disagree | Agree | Strongly Agree | No Answer | No. of Responses |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coordination of institutions and actors—The relevant actors in the district were coordinated with regard to planned skill development activities | 19.7% | 32.8% | 11.8% | 32.8% | 3.3% | 0% | 61 |

| Opposing intentions/ opinions of actors- Fellow experienced situations where they witnessed situations where fellows witnessed opposing opinions of different actors involved in the VET ecosystem, with the possibility of creating situations of implementation bottlenecks | 0% | 1.6% | 8.1% | 58.1% | 29% | 3.2% | 62 |

| Programme characteristics conflict with factors (e.g., hierarchical structures, lack of resources, administrative hurdles) in the existing system. | 0% | 4.8% | 6.5% | 40.3% | 48.4% | 0% | 62 |

| Commitment- Interest, Enjoyment, Effort | Strongly Disagree | Disagree | Neither Agree nor Disagree | Agree | Strongly Agree | No Answer | No. of Responses |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Positive Questions | |||||||

| Interest—I know that I had a sufficient interest in vocational education and training to meet the demands of my work during district immersion | 1.6% | 9.7% | 9.7% | 40.3% | 38.7% | 0% | 62 |

| Enjoyment—I enjoyed working in the districts with the administration very much | 1.6% | 9.7% | 25.8% | 25.8% | 37.1% | 0% | 62 |

| Enjoyment—After 2 years of the MGNF program, I would like to continue working in the skill development/vocational education & training landscape | 0% | 14.5% | 27.4% | 29% | 27.4% | 1.6% | 62 |

| Effort—It was important for me to perform well in the district activities | 0% | 1.6% | 3.2% | 27.4% | 67.7% | 0% | 62 |

| Negative Questions | |||||||

| Enjoyment—I will work further in the area of skill development, because there is no alternative for me available. | 34.4% | 36.1% | 16.4% | 3.3% | 3.3% | 6.6% | 61 |

| Decision-Scope and Agency | Strongly Disagree | Disagree | Neither Agree nor Disagree | Agree | Strongly Agree | No Answer | No. of Responses |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Positive Questions | |||||||

| The fellow had some choice/freedom about the different activities they did in the district | 1.6% | 4.8% | 12.9% | 43.5% | 37.1% | 0% | 62 |

| The programme fostered commitment and ownership, because the fellow had sufficient decision scope in their activities | 6.6% | 27.9% | 23% | 27.9% | 14.8% | 0% | 61 |

| Negative Questions | |||||||

| For some activities in the district immersion, the fellow felt like they had to do them | 0% | 0% | 12.9% | 53.2% | 29% | 4.8% | 62 |

| S. No. | During the Fellows’ Work in the District, They Engaged with | Never | Rarely | Sometimes | Often | On Weekly Basis | Number of Responses |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Educational/ Training Department (local level) | 1.6% | 1.6% | 25.8% | 46.8% | 24.2% | 62 |

| 2 | Educational/ Training Department (Federal government level, if present) | 5% | 16.7% | 30% | 28.3% | 20% | 60 |

| 3 | Community Committee (e.g., CBOs) | 8.1% | 16.1% | 40.3% | 21% | 14.5% | 62 |

| 4 | Employer Representative Committees | 9.7% | 24.2% | 35.5% | 25.8% | 4.8% | 62 |

| 5 | Industrial Training Institutes | 3.2% | 14.5% | 21% | 27.4% | 33.9% | 62 |

| 6 | Polytechnic Colleges | 12.9% | 24.2% | 37.1% | 16.1% | 9.7% | 62 |

| 7 | Arts and Science Colleges | 22.6% | 37.1% | 27.4% | 11.3% | 1.6% | 62 |

| 8 | Engineering Colleges | 32.3% | 35.5% | 25.8% | 3.2% | 3.2% | 62 |

| 9 | Employers/ Companies | 8.2% | 8.2% | 41% | 32.8% | 9.8% | 61 |

| 10 | National Skill Development Corporation | 24.2% | 30.6% | 33.9% | 6.5% | 4.8% | 62 |

| 11 | Sector Skill Councils | 14.5% | 25.8% | 43.5% | 12.9% | 3.2% | 62 |

| 12 | Federation of Indian Chambers of Commerce & Industry(FICCI) | 67.2% | 16.4% | 11.5% | 1.6% | 3.3% | 61 |

| 13 | Community-based Organizations/ NGOs | 0% | 16.1% | 32.3% | 33.9% | 17.7% | 62 |

| 14 | Confederation of Indian Industry (CII) | 46.8% | 24.2% | 16.1% | 6.5% | 6.5% | 62 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Regel, J.; Rajagopalan, A.; Mukherji, A.; Basu, S.; Pilz, M. Implementation of Innovations in Skill Ecosystems: Promoting and Inhibiting Factors in the Indian Context. Educ. Sci. 2024, 14, 1404. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14121404

Regel J, Rajagopalan A, Mukherji A, Basu S, Pilz M. Implementation of Innovations in Skill Ecosystems: Promoting and Inhibiting Factors in the Indian Context. Education Sciences. 2024; 14(12):1404. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14121404

Chicago/Turabian StyleRegel, Julia, Anjana Rajagopalan, Arnab Mukherji, Sankarshan Basu, and Matthias Pilz. 2024. "Implementation of Innovations in Skill Ecosystems: Promoting and Inhibiting Factors in the Indian Context" Education Sciences 14, no. 12: 1404. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14121404

APA StyleRegel, J., Rajagopalan, A., Mukherji, A., Basu, S., & Pilz, M. (2024). Implementation of Innovations in Skill Ecosystems: Promoting and Inhibiting Factors in the Indian Context. Education Sciences, 14(12), 1404. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14121404