Abstract

Theory can be of immense value in practice and to practitioners, but is sometimes perceived as esoteric and inaccessible, or divorced from “real-world” knowledge and skills needed to enact school leadership. Policy and scholarship also call for the development of school leaders capable of thinking in ways informed by a range of theories that help leaders consider issues from various perspectives. Developing principals capable of leading for the moment and in ways that improve PK–12 systems requires us to communicate about theory in a way that positions it as a window into and lens for practice and to make theory approachable for students. In this paper, drawing on scholarship and on our roles as principal preparation faculty and as former school principals, we outline a framework for thinking about and with theory in principal preparation and for embedding theory in learning in explicit ways. Together, the iterations of theory we discuss scaffold the ability of leaders to use theory to frame critical analyses, problem-solve, broaden awareness of educational and societal issues, and constructively critique K–12 education.

1. Introduction

Theory can be of immense value in leading schools and districts [1,2,3]. Theory enables analyses through a range of established lenses, introduces leaders to possible explanations for observed phenomena, and encourages us to think beyond our own informal theories-in-use (i.e., those assumptions we develop through a lifetime of personal experience). Yet when it comes to preparing principals, theory is sometimes positioned as separate from action (practice) and divorced from the “real world” of education and school leadership.

Rhetoric that casts theory as esoteric and even distracting from the “real” work of the principalship persists [4]. This is despite evidence that faculty “rarely teach only theory” [5] (p. 11) and that helping leaders link theory to practice is beneficial to accurate identification and improvement of educational problems [3,5,6,7].

Such rhetoric also emanates from both sides of the principal preparation equation. For example, we (Jo and Ron recently participated in a professional learning network (PLN) with preparation program faculty across Texas. In one session, a participant lamented that programs “need more practice and less theory!” On the other side of the coin, in a recent interview Jo conducted for a related project, a principal from the Northeast shared the following:

I think that principal preparation programs at colleges and universities need to be a little more practical with their coursework and their instructional practices, because there’s a lot of theory and a lot of reading law and things of that nature, but there isn’t much practical.

If theory is of value to the work of school leaders, it is important to confront how siloed theory has become from practice and to find ways to bridge the gap. Though this tension around the appropriate role of theory in school leadership preparation is not new [8], we see the persistence of the issue as rooted both in rhetoric and in how theory is conceptualized.

Rhetorically, the examples offered by the PLN participant and the school principal/study participant are not novel; they fit well with Nelson’s recounting of a conversation with an administrator who wanted technical assistance but “needed leaders who were grounded in reality” as opposed to theory [4] (p. 58). The rhetoric around theory and practice suggests that we have one group (the inhabitants of the “ivory tower”) that focuses on theory and another (practitioners and principal candidates) that prioritizes practice. One group ponders, and the other acts. One group is disconnected from the day-to-day realities of schools and the intense challenges school leaders face, and the other works “where the rubber meets the road”. One group discounts the lived experiences and practical wisdom of practitioners, and the other undervalues the insights that come with engaging in research across educational contexts. These silos of our own making weaken our ability to demonstrate the utility of theory in practice and to forge a path forward informed by what both groups can contribute.

Conceptually, thinking about theory as divorced from practice or as esoteric thought-work that only has purchase in scholarly literature releases both preparation faculty and aspiring leaders from the task of engaging with theory to better understand and address root contributors (e.g., historical, systemic, organizational) to problems of practice. In effect, an atheoretical approach, where students are tasked with applying rules and routines but not provided tools for thinking about or questioning underlying patterns or rationales, risks reducing leadership preparation to training. Giroux, commenting on the work of Freire, noted the following:

[Freire] denounced and endlessly criticized the conservative view in which teachers were reduced to either the role of a technician or viewed as functionaries engaged in formalistic rituals, while being indifferent to the political and ethical consequences of one’s pedagogical practices and research undertakings. […] Freire insisted that the role of a critical education is not to train students solely for jobs, but also to educate them to question critically the institutions, policies and values that shape their lives, relationships to others, and myriad connections to the larger world.[9] (pp. 9–10)

In a similar vein, we think theory is essential in preparing principals in alignment with this framing of educators as active, public intellectuals with agency. If we want programs to develop principals who are equally capable of implementing, collaborating, disrupting, and innovating in the service of school improvement, we also need to develop principals who can challenge and critique. Thinking with and through a lens of theory helps equip school leaders to lead for improvement across a range of outcomes in productive ways while being thoughtful about what systems and practices they are either upholding or disrupting.

1.1. Purpose and Structure of the Paper

In this paper, we treat theory and practice as complementary and synergistic knowledges that are inextricably linked and which should be treated as coupled if we aim to develop school leaders who “think under the surface” as they work to frame critical analyses, problem-solve, broaden awareness of educational and societal issues, and constructively critique K–12 education. As we explore this notion, we begin by discussing our positionality and approach, then provide an overview of how theory and practice are connected currently in research literature pertinent to principal preparation. We draw on scholarship around theory in education more broadly and on our roles as principal preparation faculty and as former school principals to posit a framework for conceptualizing the role of theory in principal preparation. We conclude by discussing some potential applications for principal preparation programs and faculty.

1.2. Positionality and Approach

Thinking about theory and practice as siloed or in tension is disjoint with how we have experienced the work of preparing principals and, perhaps more critically, the work of leading schools. It is important to clarify our positionalities as we return to these periodically to discuss the intersection of theory and practice in school leadership.

Jo currently works in a tenured position, teaching doctoral and Master’s level students in a program that also offers pathways to principal and superintendent certification. In addition to teaching courses, she has supervised principal practicum students and engaged in program redesign and accreditation efforts. She came to the work of school leadership preparation following over a decade of work as an administrator in Texas public schools, having worked as a high school assistant principal and as a principal in elementary and middle schools. Most recently, she was Interim Director for TCU’s two laboratory schools (Starpoint School and KinderFrogs School) in 2019–2020, which afforded her additional perspective on school leadership during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Ron works as an assistant professor of professional practice, and also teaches doctoral and Master’s-level students in the same programs as Jo. Ron coordinates the principalship and superintendent programs and is the main liaison with partnering school districts. He came to the work in 2022 after a career spanning 36 years teaching and leading in public schools in Oklahoma and Texas. His experiences as a teacher and leader included rural, suburban, and urban settings, all of which he values and draws on as he engages in his current work at the university setting.

Both authors have spent their careers as school leaders and now as preparation faculty in the United States context. In this context, principal/school leader preparation typically occurs in concert with an initial graduate (Master’s) degree or adjacent to such a degree (vis-à-vis an alternative certification program that may or may not be university-based). We happen to work within the context of university-based programming. Our positionalities afford some benefit for speaking to preparation work in the US context but also contribute to potential limitations, given that we draw on our own training, education, and experiences as well as on scholarship. Certainly, faculty and practitioners in other contexts may find their own thinking about theory and about preparing school leaders reflected in this work. At the same time, geographic influences (i.e., professional learning or licensure requirements, work experiences) and policy contexts vary, which may limit the applicability of the ideas we posit. Still, we hope this paper may at least provide fodder for comparative analysis and dialogue across cultural and educational contexts.

Although this paper is conceptual in nature, we wanted to take a structured approach to thinking about the role of theory in principal preparation. Therefore, we drew on concepts aligned with dialogic inquiry practices [9] and collaborated to create a set of questions to stimulate reflection on theory and practice and on principal preparation (see Appendix A). We anticipated that as we exchanged ideas and experiences related to theory, the process of dialogue would give rise to a “reciprocal development of understanding” [10] (p. 84). After articulating the questions, we divided them so that we would respond to three to four questions at a time. We created a Google Doc so that we could both respond in a manner that captured our thinking in a way that afforded efficiency and transparency. We responded to questions using different colored fonts, which allowed us to view overlap and differences in responses during our conversations. Though not planned, we often responded to or built off of each other’s responses within the document so that a record of the emerging dialogue was captured in real time. For each cycle of dialogue, we responded to questions individually over a period of one to two weeks and met every two to three weeks over a period of three months to discuss responses. When we began our process of analysis and writing, we were able to revisit the document and draw on initial responses, responses-to-responses, and notes captured during our live dialogues as we constructed our understanding of the iterations and selected excerpts. Our ideas about the shape and scope of theory in leadership preparation and about potential next steps for preparation programs were informed by these conversations, and we punctuate our description of the framework with excerpts from this process.

2. The Theory–Practice Landscape and Principal Preparation

Beyond broad calls for principal preparation programs to integrate theory and practice [5,6,11], actual descriptions of how that happens are scarce. Coursework in preparation programs typically involves some study of leadership theories (e.g., transformational and transactional leadership, servant leadership) that help students gain awareness of themselves as leaders and how they approach leadership [6,12]. Yet standards documents [13] and scholarship focused on principal job functions and related knowledge/skills [14,15] focus more on the discrete knowledge and skills needed to lead schools (e.g., vision, setting and supporting instructional expectations, maintaining a positive campus climate, engaging community). Recent work from the Learning Policy Institute and The Wallace Foundation does call for an embedded approach characterized by “active, student-centered instruction […] that integrates theory and practice into key leadership functions” [3] (p. 2).

Scholarship is more plentiful in cases highlighting the value of particular theories in preparation programming. For example, Woulfin reasons that as “principals operate at the nexus between policy and practice”, having knowledge about organizational theory, sensemaking theory, and framing theory would be helpful, as these “provide lenses relevant to school leaders because they focus on learning, communication, and change” [2] (pp. 166–167). This work also suggests that facility with policy theory would be useful, as school leaders often are tasked with implementing (or negotiating, or authoring) policy. Some research has identified the salience of theories related to emotion work to school leaders [16,17]. Crawford wrote about the utility of helping educational leaders understand and navigate emotional labor as part of the job, acknowledging:

The high accountability framework within which school leadership is situated means that there very few ‘safe’ emotional spaces for leaders. […] developing leaders’ conceptual knowledge of emotional labour through discussion of both the conceptual and the practical side could enhance their own leadership practice and also act as a warning in terms of their own management of emotion.[17] (p. 212)

Several scholars have noted the importance of facility with social justice theories as critical to the work of school leaders [3,18,19,20]. DeMatthews articulated how theories related to instructional/curriculum leadership can support principals’ enactment of those job duties [19].

Finally, recent research focuses on the theory–practice “gap” specifically. Roegman and Woulfin point out that what observers may consider a “gap” in the theory–practice relationship actually may be situations where school leaders are making pragmatic decisions [1]. They write, “At times, current and aspiring leaders may unintentionally couple or decouple theory from practice, while in other instances environments in which they work create opportunities for theory and practice to be more directly engaged” [1] (p. 12). In other words, context may influence or even determine how school leaders call upon or connect to theory in decision-making. Key to this work is the following assertion:

… leadership preparation programs need to ensure that their students understand their institutional contexts and the types of theories and actions that are likely to garner opposition […] At the same time, leadership preparation faculty and candidates must maintain a deep understanding of theories of educational leadership so that they do not automatically fall back on lay theories that are based on their own personal experiences in schools.[1] (p. 13)

A “gap” may not represent the absence of theory, but a communication choice that foregrounds the language of practice/action and backgrounds the language of the theory that underpins a decision. However, if students lack awareness or understanding of theory, they will not be equipped to make such a choice; while in some cases leaders may be operating in politically savvy (and theoretically informed) ways, in other instances they may be acting in congruence with a theory–practice gap.

Scholarship suggests that theory-to-practice connections in school leader preparation are desirable but often stops short of highlighting pragmatic ways for introducing theory or for talking with principal candidates about the salience of theory to practice. In what follows, we draw on our experiences, reflections, and dialogues to suggest a framework for talking about theory in practice with aspiring and developing leaders in ways that are accessible and pragmatic and that honor the experiences and knowledge these practitioners bring to the table. As we describe the framework and its component iterations, we highlight related excerpts from our reflections and conversations. We also illustrate how a problem of practice may be addressed through each iteration.

3. A Framework for Scaffolding Criticality: Iterations of Theory in Principal Preparation

To help aspiring principals leverage theory, it is important to determine what is meant by “theory” and to explore how various definitions of “theory” might attach to the work school leadership. Many definitions of theory have been offered by experts in various disciplines. For example, one definition is offered by Shapira:

A theory signifies the highest level of inquiry in science. It is a formulation of the relationships among the core elements of a system of variables that ideally is arrived at after overcoming multiple hurdles and several stages of refinement and empirical testing. […] A theory is commonly defined as an analytic structure or system that attempts to explain a particular set of empirical phenomena.[21] (p. 1312)

Though this way of thinking about “theory” is appropriate in the context of the natural sciences, it is not likely how many principal candidates might conceptualize theory; in fact, we think it likely that conversations with practitioners would more frequently reflect Nealon and Giroux’s characterization:

Theory has a bad name: “Look out, here come the airy, hard-to-understand abstractions, with no concrete examples to back them up or illustrate them”. In its very definition, theory seems neatly divorced from commonsense practice, and that’s what makes it so frustrating to study: Theory seems separated from what people do.[22] (p. 3)

Additionally, a definition like Shapira’s, rooted in fields where experimentation and replicability are the “coin of the realm”, may prove intimidating. It is also not a way of thinking about theory that is as readily applicable for the social sciences or in the principalship, where problems of practice are influenced by the complex social nature of schooling. We think it important to acknowledge definitions like Shapira’s, as this may be how aspiring leaders were first introduced to the term “theory”, perhaps as part of their primary, secondary, or undergraduate schooling in the natural sciences, but we also think it important to expand their thinking around the term.

Other definitions of “theory” are more encompassing of complex social systems and amenable to an interpretivist or constructivist approach. Bothamley, drawing on the Shorter Oxford English Dictionary, defines theory as follows:

A scheme or system of ideas or statements held as an explanation or account of a group of facts or phenomena; a hypothesis that has been confirmed or established by observation or experiment and is propounded or accepted as accounting for the known facts; a statement of what are held to be the general laws, principles or causes of something known or observed.[23] (“Introduction”, n.p.)

This definition is more broadly applicable to the use of theory as a tool for framing or explaining observations. Moving more explicitly into the social science realm, Greenfield and Ribbins center people as active agents in constructing the realities of their organizations and assert that within this frame, theory is best understood as “sets of meanings which people use to make sense of their world and action within it” [8] (p. 7). Together, these move us ever closer to a way of talking about theory such that it is accessible and useful for school leaders and as a tool that can help them examine their (educational and societal) worlds and their own (leadership) actions within those worlds.

When we began our journey of thinking about the role of theory in principal preparation, we asked ourselves to answer the question, “How do you define ‘theory’?” Our responses reflected this range of definitions and descriptions—from Shapira’s (coupled to the natural sciences) through the Greenfield and Ribbins description and into Nealon and Giroux’s. From Jo’s reflections:

I define “little ‘t’ theory” as those everyday explanations almost everyone has for how or why something happens as it does, or how we think something will unfold—almost akin to an educated guess. I would define “Big ‘T’ theory” as accepted, tested explanations of the world and how/why things happen as they do. To me, the difference in those—and I think they are both useful at times—is that the “Big ‘T’ theories” have to have been around long enough to be tested or used as a lens in empirical study.

Ron offered the following:

When I think of theory, I visualize a framework that holds all the elements of a way of thinking, seeing and believing about things. I think of a window. That window allows a view that shapes my thinking and provides a backdrop for decisions that come forth. In some ways, a theory is like an operating system. Within that operating system are the functions that allow the actions to move. I know, that’s two different ways of thinking about it but I would say that the theories provide the ‘hunches’ about the actions and steps that are taken when viewing a perspective or acting upon decision points.

What we arrived at in our dialogues was not a singular definition of “theory”, but at various ways of talking about theory in the context of school leadership. Broadly speaking, when we work with students at more advanced stages of their leadership coursework, we talk more frequently about theory as established lenses that help school leaders frame inquiry—inquiry into their own beliefs and actions, and inquiry into the problems of practice they face in their work. At the same time, we think that we can—and should—talk about theory with aspiring leaders and those at earlier stages of graduate work in ways that meet leaders where they are and help them scaffold understand about where and how theory is at work in their practice. The goal is to grow knowledge and develop proficiency with theory as a tool/support both for looking inward (understanding the self) and for acting outward (enacting school leadership).

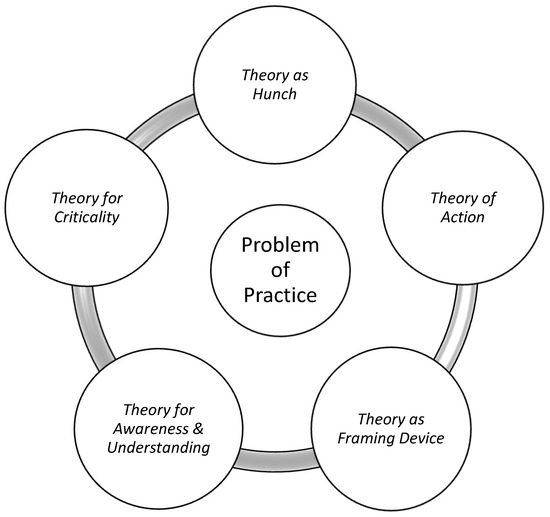

Figure 1 illustrates the framework we posit for talking about theory with aspiring school leaders in the context of principal preparation programs. We view these iterations neither as a taxonomy nor as mutually exclusive spaces, but as nuanced ways of thinking and communicating about the relationship of theory and practice (and the role of theory in practice). The framework also highlights our perspective that we all—practitioners and scholars, novice and experienced—move in and out of spaces where we think about, talk about, and use the terminology of “theory” in different ways. What is key is knowing which space we are inhabiting, having sufficient awareness to enable movement across spaces where needed, and being able to elevate thinking with theory as the moment requires.

Figure 1.

Iterations of theory in practice for principal preparation.

3.1. Theory-as-Hunch

Theory-as-hunch is the most informal iteration of theory. Though hunches are decidedly not theory, as described by scholars [8,21,22,23], everyday vernacular often wields the term “theory” as a way of opinion-proffering. We think of theory-as-hunch along the lines of an “educated guess”, though not as fully formed as a “working theory” or a “theory-in-use”. Nealon and Giroux begin their text on theory with lyrics for “Why Theory”, a song by punk band Gang of Four on their 1981 album Solid Gold:

We’ve all got opinions.

Where do they come from?

Each day seems like a natural fact,

And what we think changes how we act.[22] (p. 2)

If actions are influenced by opinions [22], it follows that school leaders may be tempted to act based on their hunches about how they think education unfolds, how learning happens, how students and employees are motivated or respond to supervision, how families can or should be involved in schools, and so forth. The problem is not in starting the thinking process from the place of hunch but of stopping there. Nealon and Giroux extend thinking on the through line that needs to follow opinion-proffering: “Oddly, it seems that for opinions to be at all productive, we are obliged to ask the question ‘Where do they come from?’” [22] (p. 3).

Aspects of this iteration of theory were reflected in our dialogues. Ron journaled about this as having leaders examine their own “theory building”, writing:

I think a theory provides the backdrop when investigating certain aspects to life. If we don’t ask educational leaders to examine other theories and then begin to explore their own theory building, we don’t provide ways in which educational leaders can become critical thinkers. They may find that their “working theory” may align with previous work and then it will motivate them to look further…

From Jo’s responses:

I think, like all leaders, I had educated guesses about how/why things happened. I didn’t always have the words for them, but I could and did draw on my own experience and on my learning (from others, from books). As I progressed in formal education, I was able to put some names to those hunches—and to use theory to think through my educated guesses better.

Through our dialogues, we agreed on the importance of acknowledging this iteration of theory-as-hunch as a starting place for working with principal candidates. Rather than dismissing this use of “theory” terminology as pedestrian or uninformed, we think it is important to acknowledge the initial ideas principals bring from the classroom and their lives to leadership work and to help them embrace hunches as initial steps toward deeper engagement with scholarship and understanding of self. We have found that inviting students to share their “educated guesses” around problems of practice and pointing out how these provide springboards to more formal theory can be an access point for linking theory and practice.

3.2. Theory of Action

School leaders are routinely called on to implement policies, programs, and practices, and doing so requires knowledge and skill for guiding practical change. Another common iteration of theory in practice is the articulation of theories of action (ToA) [3,24]. Developing a clear ToA—or a “theory of change”—is an essential skill in the planning process, as it “describes how an organization intends to work to create the outcomes it wants” [25] (p. 43). Articulating ToAs can also bring into relief disconnections between leaders’ espoused theories and theories-in-use [26].

Developing a ToA pushes leaders to surface assumptions about the origin, nature, and evolution of problems of practice. Though a ToA may be informed by implicit or explicit theories (e.g., organizational learning theory, social learning theory), key ingredients in a ToA include the following:

- Clear problem identification.

- Establishment of outcomes/goals.

- Surfacing of explicit and implicit assumptions about the problem (e.g., what contributed to it, what could alleviate it).

- Identification of action steps.

- Articulation of the “causal pathway”—describing why an action or set of actions is expected to result in a particular outcome.

- Establishment of assessment metrics to assess progress and, if needed, make adjustments at threshold intervals [27].

Working with aspiring leaders to craft a ToA can help principal candidates think about problems of practice while also surfacing deeper assumptions about why they believe certain actions will lead to particular outcomes. Such work can help leaders explore how the theories to which they ascribe (be they personal hunches, working theories, or formal theories) inform problem identification, analysis, and resolution.

In our dialogues, we talked about working with principal candidates around theories of action as a way to push back on the bias to action that sometimes comes with pressure to lead change quickly. We discussed how important it is for school leaders to practice “connecting the dots” among assumptions, evidence, and choices of action steps. We also talked about how important it is to center ToA work around problems of practice as experienced by aspiring leaders. Jo reflected:

When I think of a “theory-practice imbalance” what comes to mind is […] situations where people are “turning the crank”, whether it’s supervision processes, or using discipline matrices, but they don’t understand WHY they are doing it that way, or why what they’re doing is expected to result in a certain outcome. So, for example, they might apply a discipline matrix for a dress code violation, but not see through to racist or gendered roots of parts of the dress code…

Ron added [in connection to situations of theory–practice imbalance]:

I think of task-oriented actions that are a result of immediacy. A lack of time, knowledge, capacity, or support may lead to a practice because a situation needs to be resolved within a short amount of time.

In our discussions, what emerged was the idea that even beyond campus planning, we can help students think through—and articulate—theories of action around everyday practical concepts like supervision cycles, discipline policies, and scheduling practices. Situating theory of action development within authentic leadership tasks highlights an iteration of theory that is useful for principal candidates and which could inform more nuanced responses to challenges in the school setting; such a focus could also push back on rhetoric that reifies the separation of theory from practice. Beyond the use of theories of action for formal planning processes, developing a habit of connecting the dots—from decision to outcome through awareness of implicit or explicit theoretical assumptions—is one that will serve leaders well [25,27].

3.3. Theory as Framing Device

A third iteration of theory is theory as framing device. In early dialogues, both of us identified critical thinking and problem framing as essential skills and dispositions we thought candidates needed to possess to be the “ideal entry-level administrative candidate”. Our inclusion of these among key skills aligns with the evidence around principal preparation: knowledge and skills related to systems thinking; problem identification, framing, and analysis; and change leadership are all commonly noted components of effective school leadership [2,3,7,13,14,28]. This iteration of theory-as-frame for problem analysis was also common in research related to school leader preparation, perhaps because scholars find it a comfortable fit with how they use theory in research.

Scholarship focused on school leader preparation often suggests value in introducing particular formal theories with clear practical applications at the campus or district level. For example, DeMatthews asserted that weaving instructional leadership, distributed leadership, and social justice leadership theories into curriculum leadership would enhance principals’ skills and efficacy for leading learning [19]. Woulfin assessed instructional activities used in principal preparation work and concluded that explicitly introducing and integrating organizational theory (inclusive of sensemaking and framing theory) helped aspiring leaders better understand policy leadership and “factors enabling (or constraining) implementation” [2] (p. 172). Acton highlighted the utility of change theories to school leaders [29]. Several scholars have underscored the importance of introducing aspiring leaders to theories related to social justice work, cultural competence, and identity development [20,30,31]. Beyond this exists a wealth of scholarship that speaks to how principal programs themselves use theory to guide program work and instruction in line with social justice theories, critical theories, adult learning theories, and others [7,31,32].

Unsurprisingly, given our positions as preparation faculty, our dialogues highlighted thinking on the utility of helping students use theories to frame problems of practice. Ron journaled:

… a theory helps an educational leader to view a situation in a critical way, helps them to examine all perspectives when acts happen.

Jo reflected:

… if we help [principal candidates] see problems in different ways, and to analyze them through various (established) lenses, and to reflect on their own practice in ways that help them “see beneath” the problems and issues, I think they’ll be better positioned to tackle problems that aren’t even on our radar yet.

As we discussed this iteration of theory in practice, we explored practical and nonthreatening approaches that could be used with principal candidates to introduce them to formal theories and to help them use these to frame problem identification and analysis. Ron brought up the importance of incorporating more content that can provide students with “a better understanding of adult learning theory and how it relates to working with adults”, given how often principals are expected to coach, guide professional learning for individuals and groups, and generally facilitate cooperative groups of adults, like Professional Learning Communities. Jo talked about “pulling back the curtain on how different theories enable framing” and described using, in an introduction to educational research course, a reading from David Tyack that demonstrates how the use of different theories or lenses foregrounds some concepts and inevitably backgrounds others [33]. Students then apply their understanding to deep dives into problems of practice and engage in analysis of the issue from two different theoretical frames to illustrate how framing choices can inform decision-making.

More recently, Jo has experimented with ChatGPT as a “thinking partner”, guiding students through using prompts as a point of access to various theories. For example, the starter prompt, “What theories might help me consider why kids aren’t engaged at school?” produced a list of nine theories (certainly not comprehensive, but a good start for a practitioner beginning down the road of theory). A follow-up prompt used two of the nine suggestions and read, “How would my inquiry into this problem look different if I used motivational systems theory as opposed to culturally relevant pedagogy?” ChatGPT then produced a deeper explanation of concepts core to the inquiry. With the caveat—always shared with students—that a next step requires consulting the actual research (and scholars) in a field to verify information produced by AI, we acknowledge that technology provides opportunities that enable practitioners to engage with theory as a framing tool with fewer time and resource barriers than in the past.

3.4. Theory for Awareness and Understanding

Though crafting a theory of action and choosing/using a theory for framing can certainly support the development of awareness and understanding about the self, the world around us, and our role in that world, those iterations do not by necessity require the kind of engagement with theory we imply here. When we make this iteration of theory explicit to principal candidates, we do so in an effort to provide them access to new ways of thinking and of rethinking who they are, how they came to be as people and as leaders, and how the systems around them tend to unfold. For us, this iteration of theory is associated with praxis, as it leverages theory to help leaders reflect on not only what they are doing (action) but how and why they are acting as they are.

Almost 30 years ago, Black and Murtadha wrote about the search for a signature pedagogy in educational leadership—a task undertaken in the context of a debate as to whether “educational leadership programs—from principal certification to doctoral preparation—sufficiently connected the university course of study with day-to-day-work in schools” [18] (p. 1). Their words ring as current today as when they were written. We wonder if this iteration of theory might play a bigger role in such a “signature pedagogy” as preparation faculty use it to help principal candidates think under the surface and beyond the moment. Principal preparation programs have been “redesigning” for decades. Is this because the big problems of education are shifting? Yes, often! Is it also because we keep reorienting to problems as they become highly visible, while problems under the surface—problems fed by deeper tensions such as what is taught to whom, when, how, and why; the purpose of school and the school’s connection to community; the roles and responsibilities of adults in supporting youth development; and on and on—go unattended or are dealt with only in passing?

Theory provides a window into these deeper tensions, into other ways of considering problems and root contributors, and into the self. It serves as an access point for thinking about persistent problems in education in granular as well as expansive ways. Exploring theory is therefore valuable for school leaders who want to think broadly and deeply about their decisions and how those decisions intersect with the systems around them as they work to make schooling better for the students and adults in their contexts. One example of the use of theory in supporting the development of awareness and understanding is captured by Gooden and O’Doherty, who recounted a learning task in a principal preparation program that required students to compose racial autobiographies [20]. Through engagement with culturally responsive school leadership, students explored racial identity development, which the authors noted is “a necessary first step toward building an awareness of race, privilege, and institutional and societal systems of racism and other forms of oppression” [20] (p. 250).

Other theories can also help students reflect on their identity, their leadership orientation, their assumptions about learning, motivation, efficacy, student behavior, and a range of education-relevant concepts. Theory does not have to be esoteric and separate but can be the stimulus for what Nelson termed “sustained, disciplined thought” [4] (p. 59). Guided by various theories, this sustained, disciplined thought also becomes focused and intentional. When students engage with theory and use it as a lens to examine themselves, their world, and their actions, they in effect dialogue with theory. Freire noted that within dialogue, “we find two dimensions, reflection and action, in such radical interaction that if one is sacrificed—even in part—the other immediately suffers” [34] (p. 87). To enable thoughtful practice and decision-making, we want students to be in ongoing dialogue with theory—to be able to notice theory in their practice and in the systems around them, and to enact practice informed by selected theories.

Our conversation around this iteration of theory was underpinned by an appreciation of theory as a catalyst for expanded thinking. Jo reflected:

I think for me the ideal for [using theory in praxis] is characterized by the professional who builds in time for professional learning and reflection. Perhaps they’re continuing in their own education, so there is built-in space for holding up problems of practice to a lens of theory in graduate work. Or they are leveraging a PLN—using that PLN space to reflect on problems of practice in ways informed by theories with other leaders. Theory and practice truly stay in conversation with each other and practice becomes iterative in a way that is cognizant of theory. I think of leaders who are reflective and whose learning creates/holds space to ask “Why is this happening here, now, and in the way it’s happening? What do I see in this problem, why do I see it that way, and how might others see/think about this?”

In his journaling, Ron made connections between his current approach as leadership preparation faculty and his own experiences as a learner and leader:

I think students need to be exposed to a range of theories so that they are informed of previous work and could possibly connect to a way of thinking that aligns with their perception. I wonder if the topic of theory building should be incorporated into a leadership class as an introduction to theory? During the leadership class, we spent a lot of time delving into the “why you believe what you believe”. I don’t want to list specific “theories” as ones that everyone should learn. However, might a task be created that causes them to [connect] with a particular theorist? I still remember a literacy class that I had at Baylor, which was one of my first courses in the curriculum and instruction program. The teacher asked us all to think of one or two individuals that appear to match your belief systems. For me, it was Bruner and Piaget. By digging deeper into their work, I became familiar with how I believe learning occurs.

For both of us in our practitioner lives, theory functioned as a gateway to insights about how aspects of education tend to unfold. Theory also provided us with the opportunity to engage in reflection to better understand ourselves and our roles in the world. As faculty, we hope to provide principal candidates with similar opportunities.

3.5. Theory for Criticality

Though our framework for conceptualizing iterations of theory in principal preparation is not a taxonomy, talking about theory as it relates to criticality—for the development of critical consciousness—is obviously more complex than talking to principal candidates about theory-as-hunch or even about articulating theories of action. Whereas other iterations offer the opportunity to examine the self, to frame a problem, or to expand understanding of patterns in education and society, we see theory for criticality as prompting critique and action.

Freire wrote that “human activity consists of action and reflection: It is praxis; it is transformation of the world. And as praxis, it requires theory to illuminate it. Human activity is theory and practice; it is reflection and action” [32] (p. 125). The concept of theory in praxis also shows up in a prior iteration (theory for awareness and understanding), though there it could be benign—leaders could engage in cycles of work and reflection on work and still remain bound to replicating accepted patterns of work and voice within their respective institutions. This iteration of theory puts feet to ideas in ways that require challenging the status quo when necessary.

Leveraging theory for criticality requires three elements: noticing, implicating, and acting. First, theory can put ideas, concepts, and patterns on leaders’ radars so that they notice problems that have previously been fuzzy or even invisible. The concept of “inattentional blindness” suggests that when a leader is operating at a fast pace, pulled at by myriad distractors, the leader may quite literally not see or notice things that would, in other contexts, be obvious [35]. “High attentional load” reduces noticing [35]. It is not hard to imagine that school principals often operate in contexts that demand “high attentional load”. If they lack tools that prompt noticing—recognizing issues that contribute to inequity, marginalization, decreased sense of belonging, increased requirement of social or cultural capital to navigate schooling practices, or decreased odds of social, emotional, or cognitive development—important tasks of leadership may go unnoticed and unaddressed. Putting pertinent theories on principals’ radars may help them be more attuned to these patterns that ultimately affect a range of student and campus outcomes.

Once principals notice problems, the next element is “implication”. den Heyer, commenting on the work of Segall and Gaudelli [36], explained:

…most students come to their courses habituated as consumers of theory and practice rather than as generators of such. […] Segall and Gaudelli interpret that most of their students prefer to engage theory, readings, and their own learning—that is curriculum—in a “readerly” rather than “writerly” manner. In a “readerly” approach to text, meaning is assumed to reside in the text itself. Readers require practice and skill refinement to extract that meaning. In contrast, in a “writerly” approach to text readers are called upon to make meanings through the context of their own lives.[37] (p. 27)

To learn in whatever manner we instruct aspiring principals—readings of text, simulations, fieldwork, and reflections on fieldwork—a “readerly” approach allows the students to keep the learning at arm’s length. The lessons, work tasks, and theories describe other people, other people’s children, and, in general, situations that only affect others. In a “writerly” approach, the students themselves become implicated—engaged productively in the work as they see themselves as part of the milieu, including seeing themselves as part of the problem or solution.

Active engagement is the final requirement for using theory for criticality. Feldman and Orlikowski describe three approaches to engaging in the study of practice: the empirical, the theoretical, and the philosophical. The empirical approach to studying practice “answers the ‘what’” and is “a focus on the everyday activity of organizing in both its routine and improvised forms” [38] (p. 1230). As principal preparation faculty, we help students explore the evidence base for everything from assessment practice to social emotional learning to instructional supervision and coaching. In this way, we help them map out the “what” of their work.

The theoretical approach to studying practice focuses on everyday activity while being “critically concerned with a specific explanation for that activity. This approach answers the ‘how’ of a practice lens—the articulation of particular theoretical relationships that explain the dynamics of everyday activity, how these are generated, and how they operate within different contexts over time” [38] (p. 1241). As preparation faculty, we introduce theories (to explore hunches, to plan, to frame, to develop awareness and grow understanding), to help students surface their assumptions around problems of practice, and to adequately explain those problems in context.

Finally, the philosophical approach, “rather than seeing the social world as external to human agents or as socially constructed by them, […] sees the social world as brought into being through everyday activity” [38] (p. 1241). As preparation faculty, we help students understand they do not simply work in systems, but the cumulative acts of the persons in those systems aggregate to shape and reshape systems [8]. As work around social justice and anti-racist leadership highlights, the journey from noticing to implication to action is critical: neutrality upholds the status quo, so without action, the mere study of injustice or inequity does not move systems forward in ways that serve all students well [39,40].

The role of theory in prompting critique and action, even in the face of institutional or societal pressures, was reflected in our journaling and discussions. Ron wrote about how his constructivist approach pushes his thinking:

For me, constructivist theories honor the social agency of individuals. It is important, to me, that people who are involved in work must experience meaning from their work. [..] When the topic relates to equity issues, and believing that a constructivist framework will create an enduring understanding, as a campus leader, I need to consider the various dispositions that stakeholders have. Have they engaged in [equity] work before? Might there be past experiences that have caused them to develop definitions around equity? As a leader, I begin with a theoretical framework as to how learning occurs. Yet, I also need to reflect upon my theoretical framework. Perhaps the decisions that I make are not attributed to a constructivist mindset. I believe we all have a foundation theoretical framework. It is either examined or unexamined.

Jo’s thoughts turned to her concern that in the absence of facility with theory, principals may be inadequately prepared to question systems:

The principalship is too complex for leadership programs to be mere training. How could we have anticipated “training” for COVID-19? For leading through the current AI explosion? We cannot be reactive in leadership prep, because we don’t always know what is coming down the road. We only do right by our students if we equip them with the ability to think critically and to see patterns that we know, from empirical study, tend to repeat. To me, theory helps leaders “think under the surface”. In preparing leaders, I worry that if they aren’t at least conversant with several pertinent theories–leadership, sociological, economic, cognitive and pedagogical, and even political theories–that they will not be ready to question, to innovate, to plan strategically. I worry that leadership prep that ignores theory is little more than training to implement the plans and policies handed down by others (for better or worse).

It is somewhat ironic that theory gets painted as ponderous thought and practice as action. As our reflective comments and the literature around praxis and criticality evidence, theory can also compel and propel to action.

3.6. A Practical Illustration: A Problem of Practice Through the Various Iterations

As noted, we think that the iterations represent different ways of conceptualizing theory, but we do not see them as mutually exclusive. To illustrate how one might approach a problem of practice in each of the iterations, we offer here an illustration of a leadership student and aspiring campus leader (Thomas) working to understand and address a problem of practice. We also note that it is entirely possible that a student might move through the iterations in sequence, jump from one to the other, or remain stuck/rooted in one iteration (a circumstance in which we would, as preparation faculty, intervene in order to help expand the student’s facility with leveraging theory/ies).

Thomas, an aspiring leader in a principal preparation program and a current middle school mathematics teacher, wants to focus an analysis on a problem of practice in his middle school. He peruses data and notices a spike in disciplinary referrals in the past year for all grades, and that what seems like a large number are for classroom outbursts and “disrespect”. He settles on “improving classroom behaviors and reducing referrals that result in exclusionary practices” as his problem or practice. His initial “hunch” is that during COVID, many students were learning through technology and from home, so they lacked routines and are still having trouble adjusting to campus expectations. He thinks that explicitly teaching expectations and routines—and being consistent with consequences—can move the campus toward better behavioral outcomes.

Working with a campus-based team, he works to articulate a theory of action for improving the problem, and through this process, he realizes his assumptions are rooted in his own experiences as an adolescent as well as in broader assumptions about what teachers across the campus are or are not already doing. Classroom visits and a teacher questionnaire both suggest teachers are being consistent in assigning consequences and in referring to classroom and school rules. Working to hone the theory of action, he collaborates with the campus team and also works through the ChatGPT exercise to help explore how other theories may be used to further think about the problem. He notices that he is primarily applying a behaviorist framing, but realizes that other theories (e.g., Bronfenbrenner’s Ecological Systems Theory, trauma-informed education, Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs) may also be helpful in framing his inquiry and may better capture elements of the problem he believes are important, such as sense of belonging and how students perceive their school and classroom context as safe or threatening.

As he takes time to explore various theories, he develops further awareness and understanding that suggests that the adults on campus also have fears, frustrations, and suffering that they are bringing to the campus and that unrecognized needs of students and staff are colliding at times; he also reflects on the dearth of counseling and other mental health and wraparound services for students, their families, and staff. Thomas begins to dive deeper into data, trying to explore root causes. He experiences frustration when he realizes that referrals denoting “disrespect” provide little to no information on specific behaviors that triggered the referrals and are disproportionately issued to students of color. He wonders if there are systemic or other biases contributing to this pattern but cannot be sure due to the lack of information included on the referrals. Through this process, he enters into a space of critique of policies and processes and begins to consider ways he can advocate for change. He thinks a good next step may be to advocate for greater specificity in documentation of behaviors on referrals and to engage with teacher and student groups to better understand their perspectives and to co-create further recommendations.

Though this hypothetical admittedly flattens much of the complexity of Thomas’ work around a problem of practice for the sake of space, it is one illustration of how Thomas might engage with “theory” in practical ways through each of the iterations. It is also only one of myriad potential pathways. In reality, the investigation may have led to a focus on organizational structures, adult learning structures and practices, and the need to engage with culturally responsive practices. What we hope to show is that by enabling school leaders to engage with theory in a range of ways, we can provide windows into existing practices and shine light on potential paths forward.

4. Applications for Preparation Programs and Faculty

So what are we to do with these iterations of theory in principal preparation? Can these approaches to talking about the value of theory in practice be of use to preparation programs engaged in program planning as faculty seek to create the kinds of learning experiences that “ensure that educational leaders are ready to meet effectively the challenges and opportunities of the job today and in the future as education, schools and society continue to transform” [13] (p. 1)? We see four potential applications for preparation faculty: (1) leverage the framework to refine how we talk about theory in practice with candidates and preparation partners; (2) make thinking with theory more accessible for principal candidates and practitioners; (3) apply or adapt our reflection–dialogue process to arrive at common understandings around the relationship of theory and practice; and (4) crosswalk program priorities to identify a “starter slate” of theories for inclusion or emphasis in program coursework and experiences.

4.1. Leverage the Framework to Connect Theory and Practice

The iterations of theory described in the framework could be used as a layered approach for introducing theory to principal candidates and for walking them through how each iteration can help connect theory to practice in valuable ways. Similar to the example offered in Section 3.6, one approach could be to choose a single theory and demonstrate how it might be used by practitioners across iterations. For example, program faculty might help a student connect an initial hunch about student behaviors with social learning theory (SLT). SLT might then be used to inform a project in which students craft a theory of action in conjunction with a campus needs assessment and improvement plan. SLT might help students frame an analysis of behavioral observations collected during campus learning walks to better understand factors that contribute to student behaviors. Diving into literature around SLT may help candidates deepen awareness about how behaviors are learned and replicated. And, as they gain depth of knowledge around SLT, they can discuss how their own behaviors or decision-making increase or decrease odds of student behavioral success. This process could be used to explore a number of educational theories. Though principal candidates surely grow in their knowledge of a range of theories over time, this framework can be used as a nuanced way of communicating how theories inform or otherwise add value to the everyday work of school leadership.

4.2. Make Theory Accessible to Practitioners

One issue that emerged as we reflected on our experiences as campus principals and on our work with principal candidates was that while we often talk about “theory-to-practice” connections, we do not always acknowledge that theory can be intimidating or inaccessible to aspiring leaders, particularly at first. The language of practice is accessible and familiar; the language of theory may be decidedly less so. Giroux commented on Freire’s complaints about how academics contribute to this problem: “Freire rejected reified notions of theory that traded in jargon and created linguistic firewalls that made it difficult to understand the issues they were addressing. He also criticized academics who removed themselves and their work from the social problems and human suffering that existed outside of the walls of the academy” [9] (p. 9).

Helping principal candidates surface theory in practice and articulate the value of theory in decision-making can be accomplished through the creation of theories of action, analyses of problems of practice, action research/inquiry projects, simulations, and uses of teaching cases. Another strategy is to explore the use of AI to guide students to engage in divergent and convergent exploration around theories. For example, Jo has explored this approach by having students freewrite about a problem of practice and what they think contributes to or could ameliorate the problem. Students then load their reflections into ChatGPT with the prompt, “What theories are reflected in how I talk about this problem, and what theories might I want to consider in further thinking about this issue?” Results provide a springboard for further discussion; also, students build awareness around particular theories and gain some awareness of implicit or favored and alternative lenses for examining practice. Use of AI tools requires guidance but could provide accessible onramps to explorations of theory that have sometimes proven elusive, given time constraints, and what may seem like myriad relevant theories.

4.3. Adapt the Reflection–Dialogue Process

Another use of the framework resides more in its creation than its articulation. Through the reflective prompts and our follow-up conversations, we were able to surface our own assumptions about the value of theory to practice, how we experienced theory in our own leadership journeys, and even what we meant when we said “theory”. We make our starter protocol available in Appendix A, and faculty in preparation programs might find this a useful experience. Adjusting the protocol as desired, structuring conversations, and determining an approach for capturing data and surfacing thinking about theory would be one way of building a shared language for connecting theory and practice. Moreover, including adjunct faculty and liaisons from school district partners could further the work. (We did not broaden this process to include more program faculty or district partners, and this is a limitation that we hope to rectify in future program work.

4.4. Identify a “Starter Slate of Theories”

For this application, we build on Roegman and Woulfin’s work on reframing the “theory–practice gap” in K–12 educational leadership, in which they provided an overview of several “theories embedded in the coursework of a sample principal preparation program” [1] (p. 10). The authors highlighted nine theories and posited practice-based applications. We do note that of those listed, we would classify some (e.g., data-based decision-making and culturally relevant pedagogy) not as theories in and of themselves but as established approaches that stem from and draw on other theories. For example, data-based decision-making research leans into a range of theories, depending on study focus and practical application, including adult learning theory [41], sensemaking and attribution theories [42], achievement goal theory [43], social learning and situated learning theories [44], and organizational learning [45], among others. Culturally responsive pedagogy draws on a range of work, including critical theory, sense of belonging, and cognitive theory [46,47].

This blending of “approach-rooted-in-theory” with “theory” is indicative of how educational leadership faculty and scholars sometimes muddy the waters linguistically. In the service of educating aspiring leaders about the iterations of theory, we do assert that preparation faculty ought to be clear as to when they are leveraging an established theory and when they are speaking or writing about a set of practices or frameworks that draw on theory or theories. With this caveat and recognizing the substantial value of the theories, frameworks, and approaches identified by Roegman and Woulfin for enacting leadership in schools, we augment this list to posit a “starter slate of theories” ripe for integration into coursework. Table 1 notes theories and frameworks identified in Roegman and Woulfin’s piece (column 1) alongside additional theories and structured approaches we have found useful in our experiences as preparation faculty and school principals and which we think worth considering in preparation coursework (column 2).

Table 1.

Theories in practice: potential theories for inclusion/emphasis in preparation programs.

Of course, it is critical that programs engage in self-study and dialogue to crosswalk desired programmatic outcomes and learning tasks with theories applicable to program priorities. For instance, a perusal of syllabi evidence that our own programs include emphases on organizational learning and change, data-informed decision-making, culturally responsive teaching and leadership, transformational leadership, critical theory, and adult learning theory, amongst others. However, the dialogues that gave rise to this paper are currently informing our next round of syllabus review as well as calibration of readings, theory emphasis, and learning tasks to ensure that we are intentional in aligning theory work with desired program outcomes. Though we have not arrived, we now have another tool to guide our program improvement journey.

5. Conclusions

Nealon and Giroux frame theory “as approach, as a wider toolbox for intervening in contemporary cultures. […] You need theory precisely because it does some work for you (and, with any luck at all, it does some work on you); it offers angles of intervention that you wouldn’t otherwise have” [22] (p. 7). Their words remind us of the value of theory, not just for doing our work well but for being thoughtful about how we engage as human beings. Practitioners value having various angles of intervention from which they can address the multiple complex problems they face day in and day out. Scholars value theory as a lens through which to approach and communicate about inquiry and as an avenue for foregrounding some aspects of a problem and backgrounding others. As both scholars and practitioners can benefit from theory, we think the time is right to stop undervaluing theory, branding it as esoteric, or acting as if it is the exclusive purview of academia. We think the time is right to acknowledge varied ways of thinking and talking about “theory” so that we can all, from our scholar, teacher, and practitioner positions, be thoughtful about problems that impact education and support continuous improvement along a range of outcomes. It is time to embrace theory as an essential component of wise leadership practice.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.B.J. and R.D.M.; approach, J.B.J. and R.D.M.; writing—original draft preparation, J.B.J.; writing—review and editing, J.B.J. & R.D.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge Cathryn van Kessel, for suggesting readings related to theory external to the field of educational leadership that informed thinking around the issues presented in this paper.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A. Question Prompts for Biweekly Dialogues

- What do you see as essential skills and dispositions that candidates need to have well in hand to be prepared for entry-level administrative (i.e., AP) work in your district? In other words, what characterizes the “ideal entry level admin candidate” in your district?

- What do you see as some of the most common gaps in the preparation to practice trajectory? Where do you see early career administrators stumbling when you would expect otherwise?

- If you were designing a principal preparation program, what concepts/experiences would you absolutely include? What do you consider essential to have in a prep program to increase the likelihood of leaders completing that program and walking into admin spots in your district “day one ready”?

- How do you define “theory”?

- How do you describe or think about the role or value of theory in preparing educational leaders?

- How do you see theory playing a role in your leadership (if it does)? If you do not really see it playing a role in your leadership, why do you think it does not play a (larger) role?

- Might the decisions/products/outcomes that principals make demonstrate a theory (explicitly or implicitly)? If so, is it important that campus administrators reflect upon their decisions to better understand the theory behind their behaviors/actions/outcomes? How might a metacognitive practice help a campus administrator to examine his or her theory, and is this practice necessary?

- How does your own leadership journey/experience (and education) influence what you think leadership prep needs to be/do and how we should approach theory/practice.

- When you think of a “theory–practice imbalance”, what do you see happening to create that imbalance? What happens as a result of that kind of imbalance?

- What do you think is an appropriate theory–practice balance? When you think of leaders you know in your district who you think balance these well, what is it those persons are doing or saying that suggests they have a good TP?

- When you think of a leader you have known who has a theory–practice imbalance (either way—maybe too theory-heavy or too theory-light), what is characterizing that person’s leadership?

- When campus leaders problem-solve, are there times when the campus leader has identified his/her action to his/her theory? If so, what circumstances caused the leader to connect theory with practice?

- In your experience, how often have you met a campus leader who changed schools because there was a conflict between theory and practice within the current setting? In what ways, if any, did the campus leader verbalize the reason?

References

- Roegman, R.; Woulfin, S. Got theory? Reconceptualizing the nature of the theory-practice gap in K-12 educational leadership. J. Educ. Adm. 2019, 57, 2–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woulfin, S.L. Fusing organizational theory, policy, and leadership: A depiction of policy learning activities in a principal preparation program. J. Res. Leadersh. Educ. 2017, 12, 166–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darling-Hammond, L.; Wechsler, M.E.; Levin, S.; Leung-Gagné, M.; Tozer, S. Developing Effective Principals: What Kind of Learning Matters? Learning Policy Institute: Palo Alto, CA, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, S.W. Experience matters in principal preparation. J. Leadersh. Stud. 2009, 3, 58–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitgang, L. The Making of the Principal: Five Lessons in Leadership Training; The Wallace Foundation: New York, NY, USA, 2012; Available online: https://wallacefoundation.org/sites/default/files/2023-09/The-Making-of-the-Principal-Five-Lessons-in-Leadership-Training.pdf (accessed on 18 September 2024).

- Darling-Hammond, L.; LaPointe, M.; Meyerson, D.; Orr, M.T.; Cohen, C. Preparing School Leaders for a Changing World: Lessons from Exemplary Leadership Development Programs; Stanford Educational Leadership Institute: Stanford, CA, USA, 2007; Available online: http://srnleads.org (accessed on 28 August 2024).

- Cunningham, K.M.W.; VanGronigen, B.A.; Tucker, P.D.; Young, M.D. Using powerful learning experiences to prepare school leaders. J. Res. Leadersh. Educ. 2019, 14, 74–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenfield, T.; Ribbins, P. (Eds.) Greenfield on Educational Administration: Towards a Humane Science; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Giroux, H. Paulo Freire’s Pedagogy of Hope in dark times [Introduction]. In Pedagogy of Hope: Reliving Pedagogy of the Oppressed; Freire, P., Ed.; Bloomsbury Academic: New York, NY, USA, 2021; pp. 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Wells, G. Dialogic learning: Talking our way into understanding. In Education as Social Construction: Contributions to Theory, Research and Practice; Dragonas, T., Gergen, K.J., McNamee, S., Tseliou, E., Eds.; Taos Institute Publications: Chagrin Falls, OH, USA, 2015; pp. 62–89. [Google Scholar]

- Hess, F.M.; Kelly, A.P. Learning to lead: What gets taught in principal-preparation programs. Teach. Coll. Rec. 2007, 109, 244–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hewitt, K.K.; Davis, A.W.; Lashley, C. Transformational and transformative leadership in a research-informed leadership preparation program. J. Res. Leadersh. Educ. 2014, 9, 225–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Policy Board for Educational Administration (NPBEA). Professional Standards for Educational Leaders; NPBEA: Reston, VA, USA, 2015; Available online: https://www.npbea.org/psel/ (accessed on 13 February 2022).

- Hitt, D.H.; Tucker, P.D. Systematic review of key leader practices found to influence student achievement: A unified framework. Rev. Res. Educ. 2016, 86, 531–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grissom, J.A.; Egalite, A.J.; Lindsay, C.A. How Principals Affect Students and Schools; The Wallace Foundation: New York, NY, USA, 2021; Available online: https://wallacefoundation.org/report/how-principals-affect-students-and-schools-systematic-synthesis-two-decades-research (accessed on 18 September 2024).

- James, C.; Crawford, M.; Oplatka, I. An affective paradigm for educational leadership theory and practice: Connecting affect, actions, power and influence. Int. J. Leadersh. Educ. 2019, 22, 617–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crawford, M. Rationality and emotion in education leadership—Enhancing our understanding. In New Understandings of Teachers’ Work: Emotions and Educational Change; Day, C., Lee, J.C.-K., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2011; pp. 205–215. [Google Scholar]

- Black, W.R.; Murtadha, K. Toward a signature pedagogy in educational leadership preparation and program assessment. J. Res. Leadersh. Educ. 2007, 2, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeMatthews, D.E. How to improve curriculum leadership: Integrating leadership theory and management strategies. Clear. House 2014, 87, 192–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gooden, M.A.; O’Doherty, A. Do you see what I see? Fostering aspiring leaders’ racial awareness. Urban Educ. 2015, 50, 225–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shapira, Z. ‘I’ve got a theory paper—Do you?’: Conceptual, empirical, and theoretical contributions to knowledge in the organizational sciences. Organ. Sci. 2011, 22, 1312–1321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nealon, J.; Giroux, S.S. The Theory Toolbox: Critical Concepts for the Humanities, Arts, and Social Sciences, 2nd ed.; Rowman & Littlefield: Lanham, MD, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Bothamley, J. Dictionary of Theories; Barnes and Noble Press: New York, NY, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Oliver, J.; Gordon, S.P.; Oliver, M.L. Examining the value aspiring principals place on various instructional strategies in principal preparation. Int. J. Educ. Policy Leadersh. 2018, 13, n3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andres, A.J.; Nordengren, C. Theory of action: The care and feeding of your mission. Kappan 2022, 104, 42–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulkley, K.E.; McCotter, S.S. Learning to lead with data: From espoused theory to theory in use. Leadersh. Policy Sch. 2018, 17, 591–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Argyris, C.; Schön, D.A. Theory in Practice: Increasing Professional Effectiveness; Jossey-Bass: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson, J.; Kemmis, S. Practice theory: Viewing leadership as leading. Educ. Philos. Theory 2015, 47, 342–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acton, K.S. School leaders as change agents: Do principals have the tools they need? Manag. Educ. 2021, 35, 43–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theoharis, G.; Brooks, J. (Eds.) What Every Principal Needs to Know to Create Equitable and Excellent Schools; Teachers College Press: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Leggett, S.R.; Desander, M.K.; Stewart, T.A. Lessons learned from designing a principal preparation program: Equity, coherence, and collaboration. J. Res. Leadersh. Educ. 2023, 18, 404–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertrand, M.; Rodela, K.C. A framework for rethinking educational leadership in the margins: Implications for social justice leadership preparation. J. Res. Leadersh. Educ. 2018, 13, 10–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyack, D.B. Ways of seeing. Harv. Educ. Rev. 1976, 46, 355–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freire, P. Pedagogy of the Oppressed, 30th Anniversary ed.; Continuum: New York, NY, USA, 1970/2007. [Google Scholar]

- Chabris, C.F.; Weinberger, A.; Fontaine, M.; Simons, D.J. You do not talk about Fight Club if you do not notice Fight Club: Inattentional blindness for a simulated real-world assault. i-Perception 2011, 2, 150–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Segall, A.; Gaudelli, W. Reflecting socially on social issues in a social studies methods course. Teach. Educ. 2007, 18, 77–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- den Heyer, K. Implicated and called upon: Challenging an educated position of self, others, knowledge and knowing as things to acquire. Crit. Lit. Theor. Pract. 2009, 3, 26–35. [Google Scholar]

- Feldman, M.S.; Orlikowski, W.J. Theorizing practice and practicing theory. Organ. Sci. 2011, 22, 1240–1253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furman, G. Social justice leadership as praxis: Developing capacities through preparation programs. Educ. Adm. Q. 2012, 48, 191–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diem, S.; Welton, A.J. Anti-Racist Educational Leadership and Policy; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Jimerson, J.B.; Garry, V.; Poortman, C.; Schildkamp, K. Implementation of a collaborative data use model in a United States context. Stud. Educ. Eval. 2021, 69, 100866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertrand, M.; Marsh, J.A. Teachers’ sensemaking of data and implications for equity. Am. Educ. Res. J. 2015, 52, 861–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jimerson, J.B.; Reames, E. Student-involved data use: Establishing the evidence base. J. Educ. Chang. 2015, 16, 281–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jimerson, J.B.; Cho, V.; Wayman, J.C. Student-involved data use: Teacher practices and considerations for professional learning. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2016, 60, 413–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gummer, E. Complexity and then some: Theories of action and theories of learning in data-informed decision making. Stud. Educ. Eval. 2021, 69, 100960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gay, G. Culturally Responsive Teaching: Theory, Research, and Practice; Teachers College Press: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Hammond, Z.L. Culturally Responsive Teaching and the Brain: Promoting Authentic Engagement and Rigor Among Culturally and Linguistically Diverse Students; Corwin: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).