Abstract

Background/Objectives: Since the importance of robust theory-driven research is emphasized in medical education and little data are available on the intentions of medical and healthcare students regarding interprofessional collaboration, this study aimed to analyze the behavioral intentions of Polish medical and healthcare students to undertake interprofessional collaboration in their future work. This study follows the assumptions of the theory of planned behavior, including analysis of the students’ attitudes, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control in this regard. Methods: Data were collected from March to July 2023 on the population of students at Poznan University of Medical Sciences (Poland) using a questionnaire developed using dedicated manuals on the theory. Results: The students demonstrated generally positive behavioral intentions and attitudes, with a mean total attitude score of 103.13 ± 33.31 in a possible range of −231 to 231. Their sense of social pressure to engage in interprofessional collaboration was weak to moderate positive, as indicated by their total subjective norm score equal on average to 57.01 ± 42.98 in a possible range of −189 to 189, or mixed when evaluated directly. Furthermore, even though they presented a neutral or moderately positive direct assessment of their perceived behavioral control, its indirect measure was weak to moderately negative, with a mean total perceived behavioral control of −80.78 ± 59.21 in a possible range of −231 to 231. Conclusions: The findings suggest that students’ perceptions of mixed social pressure and the presence of barriers or obstacles to collaboration may negatively impact their perceived ease and willingness to collaborate, even despite their initially positive attitudes towards it.

1. Introduction

In contrast to the monodisciplinary model of providing care to patients, deemed less safe and cost-efficient, contemporary healthcare requires the cooperation of different healthcare professionals to provide care to patients, especially those with complex conditions and several comorbidities [1,2]. According to the World Health Organization, an interprofessional collaborative practice describes a situation in which “health workers from different professional backgrounds work together with patients, families, careers and communities to deliver the highest quality of care” [3]. It has been shown to improve access to healthcare, the population’s health status, and patient outcomes, satisfaction, safety, and quality of received care [1,4,5,6,7,8]. Reorganization of the treatment method and focusing on interprofessional collaboration also results in improved quality of life, greater patient involvement in control of the disease, improved adherence, or even decreased dosage of drugs [9,10]. For example, the involvement of members of other healthcare professions in the care of diabetic patients brings improved therapeutic effects such as decreases in glucose and glycated hemoglobin levels [10]. Also, the involvement of nurses, who participate in patient health education and provide lifestyle advice, may contribute to a noticeable reduction in patients’ blood pressure levels [11], while including a physiotherapist and a nurse in caring for patients with headaches was shown to reduce the frequency of their occurrence [12]. It has even been observed that the termination of physician–pharmacist collaboration in the care of patients with hypertension can lead to deterioration of the previously obtained results [13]. Moreover, as other studies suggest, interprofessional collaboration can also positively influence healthcare providers by increasing their satisfaction with work and the healthcare system by improving patients’ access to care, enhancing the use of financial or human resources, and reducing costs associated with medical errors [5,14]. This should lead to the promotion and implementation of strategies to increase the presence of interprofessional collaboration in healthcare among students and medical staff members [15].

Meanwhile, as previous research suggests, there may be a number of barriers or obstacles to successful and efficient collaboration between healthcare team members, like differing levels of attitudes, willingness, and engagement toward establishing collaboration, hierarchical dependencies, professional territoriality, and culture within a given profession, as well as low awareness and knowledge of mutual roles and competencies or possibilities of collaboration, an insufficient amount of time resulting from work overload, the existence of organizational factors or physical barriers between professions, or a lack of legal regulations or remuneration for undertaking interprofessional collaboration, to name a few examples [6,15,16,17,18,19,20]. Therefore, there is a need for research on the intentions of healthcare professionals and students regarding interprofessional collaboration, as even though they may recognize its benefits and view it positively, other factors may negatively influence their intentions, including the above-listed barriers or negative social pressure. This seems consistent with the theory of planned behavior (TPB) proposed by Ajzen [21], which stipulates that individuals’ intentions to perform a given behavior are determined by their attitudes, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control. In brief, attitudes constitute individuals’ appraisals of the favorability of a behavior as well as its outcomes, subjective norms, the assessment of the personally perceived social expectations or pressure toward the behavior, and the motivation to comply with them. Finally, the perceived behavioral control involves the beliefs regarding having control over the behavior and confidence in undertaking it. The value of this theory in examining behavioral intentions in healthcare settings has already been demonstrated in the meta-analysis conducted by Armitage and Conner [22], and our previous research experiences also support its use in the subject of interprofessional collaboration among healthcare professionals and students.

Since little data have been available so far on the intentions of healthcare students regarding interprofessional collaboration, and given the importance of theory-driven research in medical education [23], the decision was made in previous stages of this research project to utilize the theory of planned behavior in a series of qualitative elicitation studies conducted to uncover the salient behavioral, normative, and control beliefs of Polish healthcare students about undertaking interprofessional collaboration and to use them to create a survey tool in order to broaden the research perspective and quantitatively examine this phenomenon on a larger, representative population of Polish healthcare students in order to diagnose the current situation, identify factors that positively and negatively influence students’ intentions, and propose necessary remediation solutions. Consequently, the aim of this study was to analyze the behavioral intentions of Polish healthcare students toward undertaking interprofessional collaboration in their future work using the theoretical framework provided by the theory of planned behavior, including their attitudes, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control, as well as the factors influencing them.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Questionnaire Development

The questionnaire used in this study was constructed following the guidelines for constructing a theory of planned behavior questionnaire developed by its author [24] and the guidelines dedicated to constructing a theory-based research tool in a systematic and replicable manner [25]. The process of item development was additionally supported by the results of a previously conducted qualitative elicitation process aimed at discovering the salient behavioral, normative, and control beliefs about the behavior in the examined population. During the questionnaire development process, attempts were made not to make it too long, as this could discourage potential future participants. On the other hand, it was also important to ensure that the items covered relevant concepts identified in the course of the above-mentioned elicitation process. As a result, an initial draft of the questionnaire was created consisting of questions on the basic demographic data of the participants, as well as 79 items on a 7-point Likert scale. A psychologist and Polish philologist was subsequently consulted to ensure its integrity and compatibility with TPB as well as the correctness of the language used. After that, the draft of the questionnaire was pretested to a sample of ten students representing different faculties and study years to ensure its understandability. Their comments led to either rewording or removing of some of the initial items, bringing the final number of items in the questionnaire to 75. The items of the questionnaire are presented in the tables throughout the Results section.

2.2. Study Settings, Procedure, and Data Analysis

Before starting this study, the research project and a copy of the questionnaire were presented to the Bioethical Committee of the Poznan University of Medical Sciences, which concluded that the study did not require its approval in the Polish legal system (Decision No. KB-177/23). Still, the authors took measures to conduct it according to the highest educational research standards [26]. Participation in this study was anonymous and completely voluntary for the students, which was emphasized in the survey description. It also informed potential participants about the aims and course of this study, including a statement of what was meant by the term ‘interprofessional collaboration’ to ensure its understanding among the respondents. Before starting the survey, the participants were also asked to consent to participate.

This study was conducted on students at Poznan University of Medical Sciences (PUMS), a public medical university in Poznan (a city in Western Poland). With the intent to obtain a thorough and comprehensive overview of the situation, students from all study years and faculties were invited to participate in this study. The data were collected between March and July 2023. The link with the survey was sent electronically to the potential participants via various channels, including e-mails, posts on social media, and the courtesy of the Dean’s Office. The required sample size necessary to consider it as representative of the population of students at PUMS (approximately 7000 students) estimated according to the formula of Krejcie and Morgan was 364 [27]. The data collection process ended after confirming that the required threshold was reached and when no new responses were received within four weeks.

The collected quantitative data were then analyzed, calculated, and scored according to the instructions provided in the above-mentioned manual [25] with regard to respective TPB constructs to determine students’ attitudes, subjective norms, perceived behavioral control, and behavioral intentions regarding interprofessional collaboration. The data analysis process also involved verifying statistical differences in the students’ responses using the chi-square test of independence, Fisher’s exact test, Spearman’s correlation coefficient, the Mann–Whitney U test, the Friedman test, and the Kruskal–Wallis test with the Conover–Iman post hoc test, as applicable. The data were analyzed using, among others, the Statistica (version 13.3) and PQStat Software (version 1.8.4) packages. All tests were considered statistically significant at p < 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Study Group

The link with the survey was started by 806 potential participants. In response to the consent to participate question, 801 agreed to participate and fill in further questions, while five disagreed. Of the 801 students who agreed to participate, 226 either did not provide any answers or answered only the demographic questions, while 575 students gave answers to the questions in the main part of the questionnaire. They represented different study years and degree courses offered at PUMS, as detailed in Table 1. As can also be observed in Table 1, most of the respondents were women, students in lower years of study, and those studying medicine or nursing. Most of the respondents had no previous experience with interprofessional education (IPE) initiatives. Whether students had IPE experiences was not significantly associated with their gender, but the students in higher years significantly more often reported previous participation in IPE initiatives than younger students (p < 0.001). As the participation in the survey was voluntary, some students did not answer all the questions, so for the readers’ convenience and ease of interpretation, all of the displayed results are supplemented with the indication of responses received for each question.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of the study group (n = 575).

3.2. Attitudes

The students’ levels of agreement with statements directly evaluating their attitudes toward interprofessional collaboration (IPC) are presented in Table 2. Following the above-mentioned manual, two of them had negatively worded endpoints on the right, so they were recoded before starting the analysis. As can be observed in Table 2, their attitudes were positive, with the majority of the respondents strongly believing that undertaking interprofessional collaboration in their future professional work would be beneficial, good practice, and the right thing to do. They also mostly agreed that it would be pleasant. Further analysis revealed that the respondents significantly less strongly believed that undertaking interprofessional collaboration would be pleasant than that it would be beneficial (p < 0.001), good practice (p < 0.001), and the right thing to do (p < 0.001). No significant differences in terms of their gender, year of study, or previous participation in interprofessional education initiatives were found in the students’ responses.

Table 2.

Students’ responses to statements directly evaluating their attitudes toward IPC.

Indirect measures also showed the respondents’ positive attitudes toward IPC. Among the behavioral beliefs regarding interprofessional collaboration, the participants most strongly agreed with the statements that undertaking interprofessional collaboration in their future work would allow them to exchange experiences with representatives of other medical professions and gain new knowledge, skills, or competencies; positively influence the treatment process and improve the quality of healthcare; give them additional opportunities for further development; improve the comfort of their work; and contribute to a better atmosphere in the workplace. On the other hand, they most strongly disagreed with statements that it would reduce their authority and dilute competencies, contribute to more frequent conflicts and misunderstandings in the team, and lead to situations where other team members would take advantage of them. A detailed overview of the respondents’ levels of agreement with statements on their behavioral beliefs toward interprofessional collaboration is presented in Table 3. In terms of the respondents’ gender, the female students agreed significantly more than the male students that undertaking interprofessional collaboration would improve the comfort of their future work (p = 0.001), while the male students more strongly agreed that it will contribute to reducing their authority and diluting their competencies (p = 0.009). The students’ year of study positively correlated with the strength of their belief that undertaking interprofessional collaboration would improve the comfort of their future work (r = 0.09, p = 0.029), contribute to a better atmosphere in the workplace (r = 0.09, p = 0.043), and increase the prestige and appreciation of their profession (r = 0.11, p = 0.009).

Table 3.

Students’ levels of agreement with statements on behavioral beliefs regarding IPC.

The students’ assessments of the outcome evaluations of their behavioral beliefs are presented in Table 4. As shown, improving the quality of healthcare, the comfort of work, the atmosphere in the workplace, and the occurrence of additional opportunities for further development, exchanging experience with representatives of other medical professions, and gaining new knowledge, skills, or competencies were viewed by the students as most desirable, while the occurrence of situations where other team members would take advantage of them, the more frequent occurrence of conflicts and misunderstandings in the team, and reducing their authority and diluting their competences were viewed as the most undesirable. In terms of gender, the female students more positively assessed the exchanging of experience with representatives of other medical professions and gaining new knowledge, skills, or competencies (p = 0.002) and the occurrence of additional opportunities for further development (p = 0.003) compared to the male students. The year of study of the respondents positively correlated with their outcome evaluations of reducing their workload (r = 0.12, p = 0.013) and increasing the prestige and appreciation of their profession (r = 0.18, p < 0.001).

Table 4.

Students’ assessments regarding outcome evaluations of behavioral beliefs.

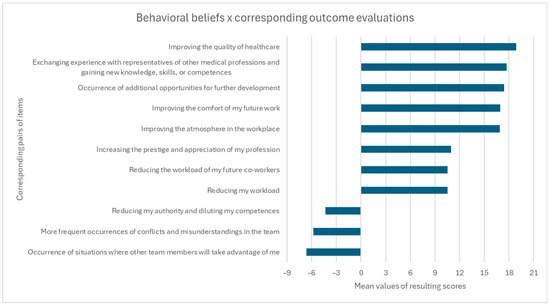

The complete answers of the students who responded to all the questions dedicated to indirect measures of attitudes, both behavioral beliefs and outcome evaluation items (n = 442), were then used to calculate the total attitude score. This process followed the procedure described in detail in the above-mentioned manual. The scores for the behavioral beliefs were multiplied by their corresponding outcome evaluation scores and summed to produce their total attitude scores, equal on average to 103.13 ± 33.31 in a possible range of −231 to 231, indicating their moderately positive attitudes. The mean scores for corresponding pairs of items of behavioral beliefs and outcome evaluations, as well as the total attitude score, are presented in Table 5, and for better presentation, they are also presented in Figure 1. The students’ total attitude scores did not differ in terms of their gender or previous participation in IPE initiatives. However, they were positively correlated with their year of study (r = 0.11, p = 0.016).

Table 5.

Resulting scores for corresponding pairs of items and the total attitude score.

Figure 1.

Visual presentation of resulting scores for corresponding pairs of items in terms of attitudes.

3.3. Subjective Norms

Table 6 presents the respondents’ levels of agreement with statements directly evaluating their subjective norms toward interprofessional collaboration, which were developed based on the TPB manual. They show a mixed sense of subjective norms expressed by the students, which is emphasized by differences in the results depending on the wording of the items. While most of the students strongly disagreed that people who are important to them think that they should not undertake interprofessional collaboration, they only moderately felt that undertaking it in their future work was expected of them, and the majority of them did not report a sense of social pressure toward doing it. There were no differences in the students’ responses depending on demographic factors.

Table 6.

Students’ responses to statements directly evaluating their subjective norms.

A moderately positive sense of subjective norms can be seen in the students’ assessments of normative beliefs toward interprofessional collaboration (Table 7). The strongest sense that they should undertake interprofessional collaboration in their future work was indicated by the participants to come from their friends and acquaintances, representatives of their future profession, their family, other students of their degree course, and patients, while the weakest sense was attributed to government authorities and politicians. Analysis of gender differences in the students’ responses showed that the assessment was significantly higher among the female students than the male students with regard to normative beliefs coming from other students of their degree course (p = 0.045), representatives of their future profession (p = 0.001), patients (p = 0.008), persons managing medical entities (p = 0.016), their family (p = 0.004), their friends and acquaintances (p = 0.002), and government authorities and politicians (p = 0.037). It was also higher among the female students than those who, in their responses, selected other gender identities with regard to other students of their degree course (p = 0.036) and government authorities and politicians (p = 0.033) as well as among the female students than those who did not want to disclose their gender for government authorities and politicians (p = 0.033). The study year positively correlated with the students’ assessment of normative beliefs coming from other students of their degree course (r = 0.10, p = 0.040), while it negatively correlated with that coming from their families (r= −0.13, p = 0.011). Also, the students with previous experiences with IPE initiatives assessed the normative beliefs coming from other students of their degree course as significantly higher (p = 0.005).

Table 7.

Students’ assessment of normative beliefs toward IPC.

Statistically significant differences were also identified between the students’ sense that they should undertake interprofessional collaboration in their future work coming from different groups (p < 0.001). A detailed analysis of these differences between relevant groups of people is presented in Table 8.

Table 8.

Differences between groups in students’ assessment of normative beliefs toward IPC.

With regard to their motivation to comply with the identified normative beliefs toward IPC, the students placed the greatest importance on the opinions of the representatives of their future profession, patients, persons managing medical entities, representatives of other medical professions, and members of their family, and they placed the least importance to what governmental authorities, politicians, and the society think (Table 9). Gender differences in their responses in this regard were also identified regarding the importance they placed on what other students of their degree course and governmental authorities and politicians think they should do, with female students placing greater importance than male students to their opinions in both instances (p = 0.031 and p = 0.007, respectively). Study year was positively correlated with the importance placed on the opinions of society (r = 0.11, p = 0.038).

Table 9.

Students’ levels of agreement with statements evaluating their motivation to comply.

Significant differences were also identified between the students’ motivation to comply with normative beliefs coming from different groups (p < 0.001), which are demonstrated in Table 10.

Table 10.

Differences in students’ motivation to comply with normative beliefs between groups.

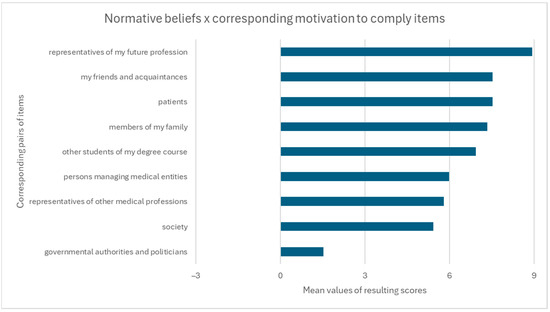

The complete answers of the students who responded to all the questions dedicated to indirect measures of subjective norms, both items on normative beliefs and motivation to comply with them (n = 386), were then used to calculate the total subjective norm score. This process was also performed following the procedure described in detail in the manual—the scores for normative beliefs were multiplied by corresponding scores covering their motivation to comply with them and summed to produce the total subjective norm scores, which on average were equal to 57.01 ± 42.98 in a possible range of −189 to 189, indicating a weak to moderate positive sense of subjective norms (social pressure). The mean scores for corresponding pairs of normative beliefs and motivation to comply items, as well as the total subjective norm score, are presented in Table 11, and for better presentation, they are also given in Figure 2. Statistically significant differences were observed in the students’ total subjective norm score in terms of their gender, with the female students presenting significantly higher scores than the male students (p = 0.001). No differences were found regarding the students’ study year or previous participation in IPE initiatives and their total subjective norm score.

Table 11.

Resulting scores for corresponding pairs of items and the total subjective norm score.

Figure 2.

Visual presentation of resulting scores for corresponding pairs of items in terms of subjective norms.

3.4. Perceived Behavioral Control

The students’ levels of agreement with statements directly evaluating their perceived behavioral control regarding interprofessional collaboration, which were also developed based on the TPB manual, are shown in Table 12. As can be observed, they were balanced between neutral and moderately positive ratings. While there were no significant differences in the participants’ responses depending on their gender and study year, the students who had previous experiences with IPE initiatives reported significantly stronger ease of undertaking interprofessional collaboration in their future work (p = 0.007).

Table 12.

Students’ responses to statements directly evaluating their perceived behavioral control.

Among the different control beliefs, the students most strongly agreed with the statements saying that the number of medical personnel is insufficient in relation to needs, there are mutual stereotypes and prejudices present between different medical professions, and the existing atmosphere and relationships in the team at the workplace influence the possibility of establishing interprofessional collaboration, while they least strongly agreed that members of other healthcare professions may not want to work with them in the future, they have insufficient knowledge about the tasks and competences of members of other medical professions, and there is (will be) a lack of time for interprofessional collaboration in everyday work (Table 13). With regard to differences in the students’ responses depending on their demographic factors, their level of agreement with the statement that the existing atmosphere and relationships in the team at the workplace influence the possibility of establishing interprofessional collaboration differed in terms of gender. Female students agreed with it significantly more strongly than male students (p = 0.044). Also, students who did not want to disclose their gender agreed with this statement less strongly than female students (p = 0.002), male students (p = 0.009), and those who selected other gender identities (p = 0.012). The year of study positively correlated with the statements saying that mutual stereotypes and prejudices are present between different medical professions (r = 0.12, p = 0.006), respondents had limited opportunities for contacts with students of other degree courses and joint (interprofessional) classes during the studies (r = 0.20, p < 0.001), members of different healthcare professions work in separation from each other (r = 0.27, p < 0.001), the number of medical personnel is insufficient in relation to the needs (r = 0.10, p = 0.023), there is a lack of legal regulations and systemic solutions regarding interprofessional collaboration (r = 0.15, p = 0.001), there is a lack of incentives (gratifications) or factors motivating students to undertake interprofessional collaboration (r = 0.11, p = 0.019), and the existing atmosphere and relationships in the team at the workplace influence the possibility of establishing interprofessional collaboration (r = 0.12, p = 0.011). The year of study negatively correlated with the students’ agreement with statements saying that they had insufficient knowledge about the tasks and competences of members of other medical professions (r = −0.20, p < 0.001) and about the possibilities of collaboration and the functioning of interprofessional teams (r = −0.16, p < 0.001). Additionally, the students who had no prior experiences with IPE initiatives more strongly agreed that they had insufficient knowledge about the tasks and competencies of members of other medical professions (p = 0.009) and about the possibilities of collaboration and the functioning of interprofessional teams (p = 0.010) and that they had limited opportunities for contacts with students of other degree courses and joint (interprofessional) classes during their studies, while the students who had previous IPE experiences agreed more strongly that there was a lack of legal regulations and systemic solutions regarding interprofessional collaboration (p = 0.042).

Table 13.

Students’ levels of agreement with statements evaluating their control beliefs.

The students’ assessment of the powers of the abovementioned control beliefs is demonstrated in Table 14. Most of them believed that a good atmosphere and relationships in the team at the workplace would make undertaking interprofessional collaboration much easier. Meanwhile, the most commonly indicated instances that would make it more difficult included the feeling that members of other healthcare professions may not want to work together with them, the feeling of a lack of time in everyday work, and the feeling that mutual stereotypes and prejudices are present between different medical professions. Gender differences in the students’ responses showed that it would be significantly more difficult for female students than male students regarding a feeling of insufficient knowledge about the tasks and competencies of other medical professions (p = 0.026) and the possibilities of collaboration and the functioning of interprofessional teams (p = 0.015), an insufficient number of medical personnel (p = 0.010), a feeling of a lack of time in everyday work (p = 0.026), and a feeling of a lack of legal regulations and systemic solutions regarding interprofessional collaboration (p = 0.008). It would also be more difficult for female students than those who did not wish to disclose their gender when members of different healthcare professions would work in separation from each other (p = 0.033) and if they felt a lack of time in everyday work (p = 0.034). The respondents’ year of study positively correlated with their assessment of the ease of undertaking interprofessional collaboration in a situation in which members of different healthcare professions work in separation from each other (r = 0.10, p = 0.048) and negatively with the potential influence of the feeling of a lack of time in everyday future work (r= −0.14, p = 0.007).

Table 14.

Students’ assessment of control belief powers.

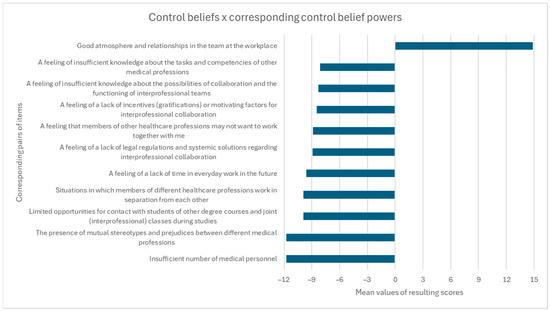

The complete answers of the students who responded to all the questions dedicated to indirect measures of perceived behavioral control, both items on control beliefs and control belief powers (n = 379), were then used to calculate the total perceived behavioral control score following the procedure described in detail in the above-mentioned manual. The scores for the control beliefs of the students were multiplied by the corresponding control belief power scores and summed to produce their total perceived behavioral control scores, equal on average to −80.78 ± 59.21 in a possible range of −231 to 231, indicating their weak to moderate negative perceived behavioral control. The mean scores for corresponding pairs of items of control beliefs and control belief powers, as well as the total perceived behavioral control score, are presented in Table 15, and for better presentation, they are also presented in Figure 3. With regard to the influence of demographic factors on the total perceived behavioral control score, statistically significant differences were observed only for the students’ gender, with the male students having a significantly higher (less negative) total perceived behavioral control score than the female students (p = 0.012) and students with other gender identities (p = 0.038).

Table 15.

Resulting scores for corresponding pairs of items and the total perceived behavioral control score.

Figure 3.

Visual presentation of resulting scores for corresponding pairs of items in terms of perceived behavioral control.

3.5. Generalized Behavioral Intention

The students’ levels of agreement with statements evaluating their generalized behavioral intention regarding interprofessional collaboration are presented in Table 16. It can be observed that they generally indicated positive behavioral intentions. No significant differences were found in the students’ responses in terms of their gender, study year, or previous participation in IPE initiatives.

Table 16.

Students’ responses to statements evaluating their generalized behavioral intentions.

4. Discussion

This study aimed to analyze the behavioral intentions of Polish healthcare students regarding undertaking interprofessional collaboration in their future work using the theoretical framework provided by the theory of planned behavior, including their attitudes, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control, as well as the factors influencing them.

The conducted analysis showed rather positive intentions of Polish healthcare students in response to statements directly evaluating their generalized behavioral intention toward establishing interprofessional collaboration in their future work and their moderately positive attitudes toward it, with the average total attitude score equal to 103.13 ± 33.31 in a possible range of −231 to 231, supporting the results of previous studies on healthcare students’ attitudes toward collaborative behaviors [15,28,29]. The responses provided by the students in our study to items assessing their behavioral beliefs also seem to reflect their positive views on the topic, and the strongest levels of agreement were observed for statements presenting interprofessional collaboration as allowing for the possibility of exchanging experiences with representatives of other medical professions and gaining new knowledge, skills, or competences; positively influencing the treatment process and improving the quality of healthcare; providing additional opportunities for further development; and improving the comfort of work and atmosphere in the workplace. Interestingly, the same aspects were also selected by the students as the most desirable outcome evaluations of their behavioral beliefs. These findings seem consistent with the students’ opinions on interprofessional collaboration experiences as opportunities for mutual learning, exchange of opinions and knowledge, and noticing their weak points [16,30,31], as well as reports on the positive effects of interprofessional collaboration between healthcare professionals on patient outcomes, including safety and quality of care, recovery time, and patient satisfaction [4,5,6,7,32,33], or healthcare personnel’s work satisfaction [34]. At the same time, the statements that students most strongly disagreed with also corresponded with outcome evaluations considered as most undesirable by them, including the beliefs that undertaking interprofessional collaboration could lead to reducing their authority and diluting competencies, more frequent conflicts and misunderstandings in the team, and situations where other team members would take advantage of them, which can also reflect their rather positive views on interprofessional collaboration. However, it is important to realize that even though most of the students in our study tended to disagree with them, such beliefs still existed among some students. In fact, some healthcare professionals and students, especially those with strong single-profession identities, may regard the idea of interprofessional collaboration efforts as threatening their professional identity and boundaries [35]. For example, medical students in a study by Friman et al. [15] wished for each profession to have and adhere to clearly defined roles and responsibilities and warned against risks associated with blurring professional boundaries.

The sense of subjective norms (social pressure) regarding interprofessional collaboration of the students in this study was mixed in direct measures and weak to moderately positive, as indicated by the average total subjective norm score of 57.01 ± 42.98 in a possible range of −189 to 189. It was also interesting to observe significant differences in the students’ normative beliefs and motivation to comply with them depending on the groups they were coming from. In the case of normative beliefs, the students reported the most positive pressure and the strongest sense of expectations regarding interprofessional collaboration to come from their friends and acquaintances, representatives of their future profession, their family, other students of their degree course, and patients, and they had the strongest motivation to comply with those from the representatives of their future profession, patients, persons managing medical entities, representatives of other medical professions, and members of their family. On the other hand, they reported government authorities and politicians as the source of the least sensed expectations toward interprofessional collaboration and reported the least motivation to comply with their opinions. The sense of positive pressure from the above-mentioned groups seems coherent with students’ behavioral beliefs regarding the positive outcomes of undertaking interprofessional collaboration for both patients and healthcare team members described in the previous paragraph.

Studies have also shown positive feedback from patients. For example, as the study by Straub and Bode [36] shows, patients on a pediatric interprofessional training ward and their parents highly rated the overall care and interprofessional collaboration. The differences between the intensity of these normative beliefs could also at least partially be attributed to potentially varying awareness of these groups about the benefits of interprofessional collaboration and work conditions in healthcare. However, the fact that the students reported the lowest pressure to undertake interprofessional collaboration from government authorities and politicians and even tended to disagree with the importance of acting according to their opinions should provoke reflection and call for actions to, on the one hand, increase the involvement of government institutions in promoting and enforcing interprofessional collaboration and, on the other hand, determine the causes of students’ beliefs and regain their trust as future healthcare professionals. Meanwhile, Polish healthcare professionals also report low involvement, interest, and social pressure from decision and policymakers toward interprofessional collaboration, including professional organizations and the national insurer [17].

Although the students demonstrated either neutral or moderately positive levels of agreement with statements directly evaluating their perceived behavioral control of undertaking interprofessional collaboration, their perceived behavioral control measured indirectly was weak to moderately negative, with the total perceived behavioral control score equal on average to −80.78 ± 59.21 in a possible range of −231 to 231. Their most commonly held control beliefs included the insufficient number of medical personnel in relation to the needs, the existence of mutual stereotypes and prejudices between different medical professions, and the role of existing atmosphere and relationships in the team on the possibility of establishing collaboration. These findings seem consistent with the recently published State of Health in the EU report, showing the lowest number of practicing physicians and nurses in the EU in Poland [37]. Also, the hierarchical structure and organization of healthcare still present in Poland might contribute to the formation and persistence of stereotypes about other professions, starting already at the stage of studies [15,38,39,40]. For instance, Salberg et al. [41] recently reported the presence of such hierarchy in power division and stereotypes among students, with physicians making decisions and nurses being cast in the role of assistants. Additionally, authoritarian hierarchies, structures, or old patterns of care culture were also viewed as controlling factors and obstacles with regard to collaboration by students in previous research [15]. Meanwhile, least commonly held but still agreed or rather agreed upon by most of the respondents were beliefs involved the notion that members of other healthcare professions may not want to work with them in the future, their sense of insufficient knowledge about the tasks and competencies of other medical professions, and that there was or would be a lack of time for interprofessional collaboration in everyday work. Among the control beliefs, only a good atmosphere and relationships in the team were regarded as facilitators of undertaking interprofessional collaboration. The remaining items were, in turn, seen as barriers or impeding factors, with the sense of reluctance of other healthcare professions to collaborate with them, a lack of time, and the presence of mutual stereotypes and prejudices between different medical professions reported as the most commonly reported instances that would make collaboration more difficult. Similar barriers and obstacles to interprofessional collaboration identified in the course of this study were also described in previous research, including, among others, work overload; insufficient amount of time; different engagement levels; professional territoriality; hierarchical structure of healthcare; low knowledge, trust, and awareness of mutual roles and competencies; few possibilities for collaboration; organizational factors; lack of legal regulations or policies; systemic solutions and remuneration for undertaking interprofessional collaboration; and lack or insufficient levels of interprofessional education [6,15,16,17,18,19,20,42]. In the example of the collaboration between physicians and pharmacists provided by Katoue et al. [20], the five most common perceived barriers, according to medical students, included pharmacists’ physical separation from areas of patient care, their lack of access to patient’s medical data, the existing professional culture, insufficient levels of education in the area of interprofessional collaboration, and physicians’ lack of trust in the clinical competencies of pharmacists, while according to pharmacy students, the five most common perceived barriers were pharmacists’ lack of access to patient’s medical data, organizational obstacles, their physical separation from areas of patient care, insufficient levels of education in the area of interprofessional collaboration, and the existing professional culture of physicians. While much of the previous research has examined and described different potential barriers to interprofessional collaboration, it is worth noting this may be the first paper that puts them in relation and evaluates both students’ sense of the prevalence of potential barriers and the degree to which they would impede interprofessional collaboration.

Some differences in the students’ responses were also identified in terms of their demographic factors. Contrary to previous reports showing a tendency for higher attitudes and readiness for interprofessional behaviors among female students [29,43,44,45], in our study, the generalized behavioral intention of the students and their total attitude score did not differ significantly with regard to gender. However, it should be mentioned that non-significantly higher values of the total attitude score among female students were noticed. They also presented more positive behavioral beliefs for some statements (as they significantly more strongly agreed that undertaking interprofessional collaboration would improve the comfort of their future work and less strongly that it would contribute to reducing their authority and diluting their competencies) and placed significantly higher value on some of the outcome evaluations. The female students also had a significantly higher total subjective norm score than the male students. Their assessments of normative beliefs were also significantly higher in several instances than their male colleagues, students with other gender identities, and those who did not want to disclose their gender, indicating that they may generally perceive stronger social pressure to establish interprofessional collaboration in the future. They were also found to place significantly more importance than their male colleagues on what other students of their degree course and governmental authorities and politicians thought they should do. On the other hand, male students were found to present significantly higher (less negative) total perceived behavioral control scores than female students and students with other gender identities, which means that they felt more in control and regarded undertaking interprofessional collaboration as easier. On a similar note, several control beliefs were also identified in which the female students reported that it would be significantly more difficult for them to undertake interprofessional collaboration compared to the male students and those who did not wish to disclose their gender.

With regard to the respondents’ year of study, it was weakly correlated with their total attitude score. Similar positive correlations were also observed for several of their behavioral beliefs like that undertaking interprofessional collaboration would improve the comfort of their future work, contribute to a better atmosphere in the workplace, and increase the prestige and appreciation of their profession, as well as their outcome evaluations of reducing their workload and increasing the prestige and appreciation of their profession. This seems consistent with the results of a previous study on Polish medical and pharmacy students showing their highest readiness for interprofessional learning in their final years of study [29]. On the other hand, the total subjective norm score did not correlate significantly with the students’ years of study. However, weak significant correlations were found with regard to some of their normative beliefs. Interestingly, it positively correlated with those coming from other students of their degree course and negatively with those from their families, suggesting that students of higher years perceive stronger social pressure toward interprofessional collaboration from other students and weaker social pressure from their families in comparison with younger students. A weakly significant correlation was also found between the study year and the importance the students placed on the opinions of society. The respondents’ year of the study did not have a significant influence on their total perceived behavioral control score, but it weakly positively correlated with several of their control beliefs, which may indicate that along the course of their studies, students become more aware or pay more attention to aspects like the presence of mutual stereotypes and prejudices between different medical professions, the separation between members of different healthcare professions at work, the insufficient numbers of medical personnel in relation to needs, or a lack of legal regulations, systemic solutions, or incentives for interprofessional collaboration, among others. The year of study also negatively correlated with some other control beliefs, including the students’ sense of insufficient knowledge about the tasks and competencies of members of other medical professions, the possibilities of collaboration, and the functioning of interprofessional teams, which can serve as a sign that they were able to fill some of these gaps in the course of their education.

Previous participation in IPE initiatives did not have a significant effect on the generalized behavioral intentions of the students and their total attitude score in this study. This was surprising, given the literature data showing its impact on students’ attitudes, self-efficacy, readiness, and willingness for collaborative behaviors, as well as their knowledge and awareness of competencies and roles of other healthcare team members [3,46,47,48,49]. In our study, this may be the result of relatively positive values of indicators of generalized behavioral intentions and attitudes among the participants. Similarly, it did not influence the participants’ total subjective norm and perceived behavioral control scores. However, several significant associations were found with regard to individual items. For example, the students who reported having IPE experiences assessed the normative beliefs coming from other students of their degree course as significantly higher, they felt that it would be significantly easier for them to establish interprofessional collaboration in their future work, and they more commonly recognized that there is a lack of legal regulations and systemic solutions regarding interprofessional collaboration. On the other hand, students who had no such prior experiences more strongly agreed that their knowledge about the tasks and competencies of members of other medical professions, the possibilities of collaboration, and the functioning of interprofessional teams was insufficient, and their opportunities for contact with students of other degree courses and interprofessional classes during their studies were limited. Meanwhile, what is consistent with these results is that interprofessional education and experiences seem to positively affect the ease of interaction, trust, attitudes, respect, and understanding of the roles and contributions of other healthcare team members, and they prevent the formation of mutual stereotypes or prejudices [30,50,51,52].

We recognize that this study may have some limitations. Most of all, it was a single-center study conducted on students of one medical university in Poland. Therefore, its results should not be regarded as characteristic of all Polish healthcare students, as the responses of students from other universities could differ. Further multicenter studies are warranted to assess students’ behavioral intentions in a broader population, including a detailed analysis of differences in students’ attitudes and intentions depending on their program of study and (due to the unique challenges of Polish healthcare) also multinational studies in different countries. Next, despite our best efforts, and although we reached the required sample size determined as described in earlier parts of this paper, there is still a risk that the sample may not reflect the true structure of the student population at our University. Although the invitations to participate in this study were directed to all students, there is a risk that students with stronger opinions on the topic (either positive or negative) could have been more inclined to fill in the survey, which might have skewed the results or the demographic characteristic of the sample. Some other limitations regarding the characteristics of the sample should also be mentioned. As can be observed in Table 1, the number of respondents differed depending on their year of study, for example. To some extent, this can be attributed to the fact that the overall number of students tends to decline with the year of study for various reasons (e.g., students dropping out, failing to pass classes, or resigning from getting a master’s degree after their bachelor studies). Nevertheless, this may also be a symptom of fatigue among students in higher years with responding to different surveys during their studies. On the other hand, younger students had fewer such opportunities so far, which may have increased their willingness to participate in this study. Moreover, a predominance of medical students was visible among the respondents. However, it was similar to the proportion of medical students in the sample of all students, since medicine is the largest degree course at our University. Also, an imbalance was visible between the numbers of female and male participants in this study, but it should be noted that this reflects the general predominance of female students in healthcare faculties in Poland. Finally, although the items in the survey were constructed following the dedicated manuals and guidelines, a risk of response bias among the participants should also be acknowledged and considered when interpreting the results, including phrasing of the questions that might have led the respondents to particular answers or the participants’ willingness to provide answers that they felt were expected. In order to help reduce this risk, the respondents were asked to complete the questionnaire in accordance with their views and opinions. The survey was also pretested before its administration to ensure its understandability, and its items were also reviewed by a psychologist and Polish philologist (as disclosed in more detail above). On the other hand, the strengths of this study should also be noticed, including the use of a strong theoretical framework provided by the theory of planned behavior, the use of a research tool developed following dedicated theory-based manuals, and conducting this research on the important but insufficiently explored topic of healthcare students’ intentions towards interprofessional collaboration.

5. Conclusions

Polish healthcare students present predominantly positive behavioral intentions toward undertaking interprofessional collaboration in their future work. Their attitudes toward it were also positive, including their behavioral beliefs and outcome evaluations. They also demonstrated a weak to moderate positive sense of social pressure expressed by their total subjective norm score and its mixed sense when evaluated directly, which suggests a need for action in this area. The identified sources of more positive social pressure and students’ motivation to comply with them should be reinforced. Additionally, Polish students’ sense of the lowest pressure toward interprofessional collaboration and their tendency to rather disagree with the importance of acting according to the opinions of government authorities and politicians indicate the need for more significant involvement of these groups in promoting and enforcing interprofessional collaboration as well as gaining the trust of future healthcare professionals. Moreover, despite their neutral or moderately positive direct assessment of their perceived behavioral control, its negative indirect measures suggest the existence of several barriers or obstacles to collaboration that should be eliminated, as they may impede the process and negatively impact students’ perceived ease and willingness for collaboration.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.P. and M.C.-K.; methodology, P.P.; software, P.P.; validation, P.P.; formal analysis, P.P.; investigation, P.P., A.C., Ł.Z.-T., M.P. and P.C.; resources, P.P.; data curation, P.P.; writing—original draft preparation, P.P.; writing—review and editing, A.C., Ł.Z.-T., M.P., P.C., M.C.-K. and R.M.; visualization, P.P.; supervision, P.P. and R.M.; project administration, P.P.; funding acquisition, P.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding. The APC was funded by Poznan University of Medical Sciences.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Ethical review and approval were waived for this study by the Bioethics Committee of Poznan University of Medical Sciences due to the fact that it was not a medical experiment and did not involve patients, and as such, approval was not necessary according to Polish law (Decision No. KB-177/23 of 10 February 2023).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data used to support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all the students who participated in the pretesting of the questionnaire and those who agreed to participate in this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Perron, D.; Parent, K.; Gaboury, I.; Bergeron, D.A. Characteristics, barriers and facilitators of initiatives to develop interprofessional collaboration in rural and remote primary healthcare facilities: A scoping review. Rural Remote Health 2022, 22, 7566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spaulding, E.M.; Marvel, F.A.; Jacob, E.; Rahman, A.; Hansen, B.R.; Hanyok, L.A.; Martin, S.S.; Han, H.-R. Interprofessional education and collaboration among healthcare students and professionals: A systematic review and call for action. J. Interprof. Care 2021, 35, 612–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization Framework for Action on Interprofessional Education & Collaborative Practice. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/framework-for-action-on-interprofessional-education-collaborative-practice (accessed on 18 August 2024).

- Lee, W.; Kim, M.; Kang, Y.; Lee, Y.-J.; Kim, S.M.; Lee, J.; Hyun, S.-J.; Yu, J.; Park, Y.-S. Nursing and medical students’ perceptions of an interprofessional simulation-based education: A qualitative descriptive study. Korean J. Med. Educ. 2020, 32, 317–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, H.-Y.; Nam, K.A. The Need for and Perceptions of Interprofessional Education and Collaboration Among Undergraduate Students in Nursing and Medicine in South Korea. J. Multidiscip. Healthc. 2022, 15, 847–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lestari, E.; Stalmeijer, R.E.; Widyandana, D.; Scherpbier, A. Does PBL deliver constructive collaboration for students in interprofessional tutorial groups? BMC Med. Educ. 2019, 19, 360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szafran, J.C.H.; Thompson, K.; Pincavage, A.T.; Saathoff, M.; Kostas, T. Interprofessional Education Without Limits: A Video-Based Workshop. MedEdPORTAL 2021, 17, 11125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piquette, D.; Reeves, S.; Leblanc, V.R. Interprofessional intensive care unit team interactions and medical crises: A qualitative study. J. Interprof. Care 2009, 23, 273–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mangione-Smith, R.; Schonlau, M.; Chan, K.S.; Keesey, J.; Rosen, M.; Louis, T.A.; Keeler, E. Measuring the effectiveness of a collaborative for quality improvement in pediatric asthma care: Does implementing the chronic care model improve processes and outcomes of care? Ambul. Pediatr. 2005, 5, 75–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rawlinson, C.; Carron, T.; Cohidon, C.; Arditi, C.; Hong, Q.N.; Pluye, P.; Peytremann-Bridevaux, I.; Gilles, I. An Overview of Reviews on Interprofessional Collaboration in Primary Care: Effectiveness. Int. J. Integr. Care 2021, 21, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, C.E.; Smith, L.F.P.; Taylor, R.S.; Campbell, J.L. Nurse led interventions to improve control of blood pressure in people with hypertension: Systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ 2010, 341, 491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaul, C.; Visscher, C.M.; Bhola, R.; Sorbi, M.J.; Galli, F.; Rasmussen, A.V.; Jensen, R. Team players against headache: Multidisciplinary treatment of primary headaches and medication overuse headache. J. Headache Pain 2011, 12, 511–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carter, B.L.; Doucette, W.R.; Franciscus, C.L.; Ardery, G.; Kluesner, K.M.; Chrischilles, E.A. Deterioration of blood pressure control after discontinuation of a physician-pharmacist collaborative intervention. Pharmacotherapy 2010, 30, 228–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prentice, D.; Engel, J.; Taplay, K.; Stobbe, K. Interprofessional Collaboration: The Experience of Nursing and Medical Students’ Interprofessional Education. Glob. Qual. Nurs. Res. 2015, 2, 233339361456056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Friman, A.; Wiegleb Edström, D.; Edelbring, S. Attitudes and perceptions from nursing and medical students towards the other profession in relation to wound care. J. Interprof. Care 2017, 31, 620–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kangas, S.; Jaatinen, P.; Metso, S.; Paavilainen, E.; Rintala, T.-M. Students’ perceptions of interprofessional collaboration on the care of diabetes: A qualitative study. Nurse Educ. Pract. 2021, 53, 103023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zielińska-Tomczak, Ł.; Cerbin-Koczorowska, M.; Przymuszała, P.; Marciniak, R. How to effectively promote interprofessional collaboration?—A qualitative study on physicians’ and pharmacists’ perspectives driven by the theory of planned behavior. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2021, 21, 903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, C.; Zimmermann, L.; Körner, M. Förderfaktoren und Barrieren interprofessioneller Kooperation in Rehabilitationskliniken—Eine Befragung von Führungskräften. Rehabilitation 2014, 53, 390–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de la Peña, I.; Koch, J. Teaching Intellectual Humility Is Essential in Preparing Collaborative Future Pharmacists. Am. J. Pharm. Educ. 2021, 85, 8444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katoue, M.G.; Awad, A.I.; Al-Jarallah, A.; Al-Ozairi, E.; Schwinghammer, T.L. Medical and pharmacy students’ attitudes towards physician-pharmacist collaboration in Kuwait. Pharm. Pract. 2017, 15, 1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armitage, C.J.; Conner, M. Efficacy of the Theory of Planned Behaviour: A meta-analytic review. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 2001, 40, 471–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cleland, J.; Durning, S.J. Education and service: How theories can help in understanding tensions. Med. Educ. 2019, 53, 42–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ajzen, I. Constructing a Theory of Planned Behavior Questionnaire. Available online: https://people.umass.edu/aizen/pdf/tpb.measurement.pdf (accessed on 18 August 2024).

- Francis, J.; Eccles, M.P.; Johnston, M.; Walker, A.E.; Grimshaw, J.M.; Foy, R.; Kaner, E.F.S.; Smith, L.; Bonetti, D. Constructing Questionnaires Based on the Theory of Planned Behaviour: A Manual for Health Services Researchers; Centre for Health Services Research, University of Newcastle upon Tyne.: Newcastle upon Tyne, UK, 2004; Volume 37, ISBN 0954016157. [Google Scholar]

- British Educational Research Association (BERA) Ethical Guidelines for Educational Research, Fourth Edition. 2018. Available online: https://www.bera.ac.uk/researchers-resources/publications/ethical-guidelines-for-educational-research-2018 (accessed on 18 August 2024).

- Krejcie, R.V.; Morgan, D.W. Determining sample size for research activities. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 1970, 30, 607–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avrech Bar, M.; Katz Leurer, M.; Warshawski, S.; Itzhaki, M. The role of personal resilience and personality traits of healthcare students on their attitudes towards interprofessional collaboration. Nurse Educ. Today 2018, 61, 36–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cerbin-Koczorowska, M.; Przymuszała, P.; Michalak, M.; Piotrowska-Brudnicka, S.E.; Kant, P.; Skowron, A. Comparison of medical and pharmacy students’ readiness for interprofessional learning—A cross-sectional study. Farmacia 2020, 68, 1166–1172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Awaisi, A.; Saffouh El Hajj, M.; Joseph, S.; Diack, L. Perspectives of pharmacy students in Qatar toward interprofessional education and collaborative practice: A mixed methods study. J. Interprof. Care 2018, 32, 674–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kara, A.; DeMeester, D.; Lazo, L.; Cook, E.; Hendricks, S. An interprofessional patient assessment involving medical and nursing students: A qualitative study. J. Interprof. Care 2018, 32, 513–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seaman, K.; Saunders, R.; Dugmore, H.; Tobin, C.; Singer, R.; Lake, F. Shifts in nursing and medical students’ attitudes, beliefs and behaviours about interprofessional work: An interprofessional placement in ambulatory care. J. Clin. Nurs. 2018, 27, 3123–3130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaifi, A.; Tahir, M.A.; Ibad, A.; Shahid, J.; Anwar, M. Attitudes of nurses and physicians toward nurse–physician interprofessional collaboration in different hospitals of Islamabad–Rawalpindi Region of Pakistan. J. Interprof. Care 2021, 35, 863–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vestergaard, E.; Nørgaard, B. Interprofessional collaboration: An exploration of possible prerequisites for successful implementation. J. Interprof. Care 2018, 32, 185–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalili, H.; Orchard, C.; Laschinger, H.K.S.; Farah, R. An interprofessional socialization framework for developing an interprofessional identity among health professions students. J. Interprof. Care 2013, 27, 448–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Straub, C.; Bode, S.F.N. Patients’ and parents’ perception of care on a paediatric interprofessional training ward. BMC Med. Educ. 2019, 19, 374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- State of Health in the EU. Poland. Country Health Profile 2017. Available online: https://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0006/355992/Health-Profile-Poland-Eng.pdf (accessed on 18 August 2024).

- Mandy, A.; Milton, C.; Mandy, P. Professional stereotyping and interprofessional education. Learn. Health Soc. Care 2004, 3, 154–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewitt, M.S.; Ehrenborg, E.; Scheja, M.; Brauner, A. Stereotyping at the undergraduate level revealed during interprofessional learning between future doctors and biomedical scientists. J. Interprof. Care 2010, 24, 53–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reeves, S.; Tassone, M.; Parker, K.; Wagner, S.J.; Simmons, B. Interprofessional education: An overview of key developments in the past three decades. Work 2012, 41, 233–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salberg, J.; Ramklint, M.; Öster, C. Nursing and medical students’ experiences of interprofessional education during clinical training in psychiatry. J. Interprof. Care 2022, 36, 582–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zielińska-Tomczak, Ł.; Cerbin-Koczorowska, M.; Przymuszała, P.; Gałązka, N.; Marciniak, R. Pharmacists’ Perspectives on Interprofessional Collaboration with Physicians in Poland: A Quantitative Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 9686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Axelsson, M.; Jakobsson, J.; Carlson, E. Which nursing students are more ready for interprofessional learning? A cross-sectional study. Nurse Educ. Today 2019, 79, 117–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilhelmsson, M.; Ponzer, S.; Dahlgren, L.-O.; Timpka, T.; Faresjö, T. Are female students in general and nursing students more ready for teamwork and interprofessional collaboration in healthcare? BMC Med. Educ. 2011, 11, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seselja-Perisin, A.; Mestrovic, A.; Klinar, I.; Modun, D. Health care professionals’ and students’ attitude toward collaboration between pharmacists and physicians in Croatia. Int. J. Clin. Pharm. 2016, 38, 16–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thistlethwaite, J.; Moran, M. Learning outcomes for interprofessional education (IPE): Literature review and synthesis. J. Interprof. Care 2010, 24, 503–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kent, F.; Keating, J.L. Interprofessional education in primary health care for entry level students—A systematic literature review. Nurse Educ. Today 2015, 35, 1221–1231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacLeod, C.E.; Brady, D.R.; Maynard, S.P. Measuring the effect of simulation experience on perceived self-efficacy for interprofessional collaboration among undergraduate nursing and social work students. J. Interprof. Care 2022, 36, 102–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cerbin-Koczorowska, M.; Przymuszała, P.; Michalak, M.; Skowron, A. Effective interprofessional training can be implemented without high financial expenses—A prepost study supported with cost analysis. Farmacia 2022, 70, 976–984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cropp, C.; Beall, J.; Buckner, E.; Wallis, F.; Barron, A. Interprofessional Pharmacokinetics Simulation: Pharmacy and Nursing Students’ Perceptions. Pharmacy 2018, 6, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rotz, M.E.; Dueñas, G.G.; Zanoni, A.; Grover, A.B. Designing and Evaluating an Interprofessional Experiential Course Series Involving Medical and Pharmacy Students. Am. J. Pharm. Educ. 2016, 80, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferri, P.; Rovesti, S.; Magnani, D.; Barbieri, A.; Bargellini, A.; Mongelli, F.; Bonetti, L.; Vestri, A.; Alunni Fegatelli, D.; Di Lorenzo, R. The efficacy of interprofessional simulation in improving collaborative attitude between nursing students and residents in medicine. A study protocol for a randomised controlled trial. Acta Biomed. 2018, 89, 32–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).