1. Introduction

As economies worldwide transition towards knowledge-based models, higher education institutions face the critical challenge of preparing students for a rapidly evolving job market. This shift demands a diverse graduate skill set, including critical thinking, effective communication, and technological proficiency [

1,

2]. This transition presents unique challenges and opportunities for educational institutions and policymakers in developing countries [

3].

Like many developing nations, Oman is actively working to diversify its economy and build a knowledge-based society. This transition requires a workforce equipped with the skills and competencies necessary to drive innovation and economic growth in an increasingly competitive global market [

4].

With a comprehensive, well-monitored skill development program, higher education institutions in Oman, including SQU, are committed to preparing graduates to lead Oman’s ongoing shift to a knowledge-based, flexible economy. This commitment entails creating a robust ecosystem that provides access to networks, mentors, resources, tools, and career prospects. The ultimate goal is to build human capital capable of developing innovative products and enhancing local and global prosperity through information-based delivery [

5].

For Oman’s economy to flourish and society to advance in the coming years, students must acquire certain skills necessary to meet the demands of a highly competitive, technologically advanced economy. SQU, as the top university in Oman, understands these future needs and is committed to leading the way in realizing this knowledge-driven goal by nurturing the talent of its students. This study aims to comprehensively evaluate students’ readiness for the knowledge-based economy. Our objectives are threefold: firstly, to assess the current skill levels of students in relation to the knowledge-based economy, establishing a baseline understanding; secondly, to identify specific skills that need further development to prepare students for future market demands; and finally, to formulate targeted recommendations and interventions designed to systematically enhance these identified skills, ensuring they align with the requirements of an increasingly dynamic and technology-driven global economy. Through these objectives, we seek to bridge the gap between current educational outcomes and the evolving demands of the knowledge-based marketplace.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Higher Education’s Role in a Knowledge Economy

Over the last several years, there has been a renewed interest in higher education serving a knowledge economy due to an increased focus on innovation and technological change fueled by an ever-growing emphasis on science-based progress [

6]. This literature review focuses on the range and complexity of actions that higher education institutions are undertaking to contribute significantly as drivers for economic development in an era when one can no longer work outside the competitiveness of the global marketplace.

For example, Deiaco et al. [

7] conducted a study on how higher education institutions are part of the nodes that concentrate resources in knowledge production and diffusion. While doing so, they research and develop prototype innovations as innovative impacts and pull from inventions that seem circumscribed by compact technology incubators, but also—through these institutions where things happen that matter—they respond to demand paths of technologies responding to tried-and-true pathways, arguably seeding talking points about how technological diffusion replays and responds reliably.

A recent study by Ullah et al. [

8] on information sources used by early investigators envisioned the effect of higher education institutions on regional and national economic growth. These include human resources development, technical assistance, economic research, and the technology transfer or promotion of innovation. They consist of innovating and creating entrepreneurial, impact-driven, and demand-led technical support economic research technology transfer collaboration (and networking) with industries/stakeholders [

9]. Semi-structured interviews were conducted.

Fortunato et al. [

10] argued that institutions play a critical role in developing innovation and entrepreneurship by creating a favorable environment, providing resources for individuals and families to thrive, and helping them turn their ideas into products. A society’s entrepreneurial ecosystem thus comprises its legal, financial, educational, and cultural institutions.

Furthermore, there is a growing global appreciation of higher education institutions as key players in regional and national economic development. Higher education institutions also provide education, conduct research, nurture entrepreneurship, and contribute to the economic development of regions and countries [

11].

Previous research on the critical role that higher education institutions play in a knowledge economy has highlighted their multiple benefits to economic development and global competitiveness. They have emphasized the crucial role of these institutions in knowledge creation and dissemination. They also serve as a springboard for businesses, assist start-ups on technical issues, and contribute in various ways to regional and national economic development [

12,

13,

14].

Furthermore, the review emphasizes the interdependence of legal, financial, educational, and cultural institutions in forming the entrepreneurial landscape. This interconnection offers a nuanced view of the critical role of higher education institutions. It provides valuable insights for policymakers, educators, and anyone interested in the relationship between education and economic development [

15,

16].

The outcomes of these studies lay the groundwork for future research and policy development in education and economic growth. Higher education institutions have a key role in promoting innovation and economic prosperity [

17]. Policymakers and educators should note these findings as they work to foster economic growth and competitiveness in their regions.

2.2. Skills and Competencies in the Modern Economy

The modern economic landscape emphasizes the relevance of skills and competencies in determining individual and organizational performance. In today’s fast-moving world, technical improvements are accelerating, the employment market is continuously changing, and globalization has driven some skills into high demand while rendering others completely obsolete.

The literature reveals that the global economy and post-industrial society have created new demands on academic services and increasingly require universities to convey competencies and skills that enable people to adjust quickly and directly to new demands instead of providing traditional content-based education. Digital literacy, critical thinking, problem-solving skills, and adaptability now play a prominent role in business success and creating a collaborative workplace environment [

18].

Furthermore, the importance of soft skills alongside technical competencies in the modern economy has been highlighted. Employers increasingly seek individuals with strong communication, teamwork, and leadership abilities. These soft skills complement technical competencies and are essential for driving organizational success and fostering a collaborative work environment [

19].

Moreover, identifying and developing industry-specific skills and competencies have garnered significant attention. Different sectors of the modern economy have distinct requirements, and understanding these specific skill sets is crucial for workforce planning, talent development, and economic growth. For instance, the healthcare industry may highly value empathy and patient communication. At the same time, the technology sector may prioritize coding proficiency and data analysis skills to meet the labor market demands. Universities and educational institutions must align their curricula and training programs with the specific competencies various industries require [

20,

21].

In contrast, some studies on the modern economy argue that focusing solely on specific skills and competencies may lead to a lack of emphasis on the importance of a well-rounded education and holistic human development. According to these studies, an excessive focus on technical skills and competencies may overlook crucial qualities such as creativity, ethical judgment, and a sense of social responsibility. These are all essential for addressing complex societal challenges and working towards a more inclusive and fairer economy [

22,

23].

There is an ongoing debate about whether skills and competencies alone can address the imbalances in labor markets. While enhancing someone’s ability to work or find job opportunities is important, it is also important to recognize that skill training programs may need to overcome barriers such as discrimination, inequality, and inactivity. In order to strengthen skills and build a national knowledge-based and innovation-oriented economy, governments must also consider other important factors, such as policies, infrastructure, and market regulations, which significantly impact the success of these economic efforts [

24,

25].

Studies have highlighted higher education’s vital role in the knowledge economy, showcasing its diverse contributions to economic growth, such as knowledge production, support for entrepreneurs, and assistance to local governments. It cultivates knowledgeable individuals, driving development and job creation. While recognizing this multi-faceted role, concerns arise about the need for a deeper analysis, including funding reductions for education, gender discrimination, and minorities’ struggles for equality and social justice related to modern higher education.

2.3. Challenges and Opportunities in Knowledge Economies

Challenges and opportunities in the knowledge economy are often difficult to separate, showing the dynamism of contemporary economic landscapes. Consequently, the knowledge economy issue has clearly produced extensive theoretical and policy-oriented studies because it has enormous transformative effects on economic growth and innovation.

The burst of technological change means that the workforce constantly has to adjust, as David and Ambrogio et al. [

26] pointed out. With this rapid development, many existing skills have become useless, leaving a big gap in the labor force that has to be bridged through ongoing study. As a result, education systems—as Moumni [

27] discusses—must think through their strategies afresh and adopt completely new training methods to provide the essential skills needed for survival in this fast-changing knowledge economy.

As Dagher and Fayad [

28] remind us, effective management and knowledge sharing play a key role in taking on these challenges. Organizations must establish a valuable environment to create conditions for efficiently organizing and spreading knowledge across sectors. However, on the contrary, if knowledge economies’ knowledge and resources are unevenly distributed, as Tumusiime [

29] argues, this will be an obstacle to making growth more equal (inclusive) and reducing socioeconomic disparities.

Moreover, as highlighted by Guo et al. [

30], the complex issue of managing and safeguarding intellectual property rights requires a careful balance between knowledge-sharing, collaboration, and protection. In response to multifaceted challenges like these, as Wingard and LaPointe [

31] emphasized, there is an urgent need for continuing investment in education and lifelong learning to maintain flexibility and the essential skills demanded by the knowledge economy. Thus, a coherent approach to teaching, knowledge management, and protecting intellectual property rights is necessary to meet the demands of a rapidly changing environment within the knowledge economy.

Many studies have highlighted that legacy companies in the knowledge economy have opportunities for learning and innovation [

32,

33,

34]. According to Kofler et al. [

35], three important opportunities stand out: the growth of high-tech industries, the development of highly skilled individuals, and increased labor productivity. This perspective does not view the chain of events as just a series of steps but rather as elements that can drive economic development by interacting with each other. It is important to note that the growth of high-tech industries raises concerns about innovation and competitiveness. However, many people act as if these concerns are not related to the three points mentioned above.

Research by North and Kumta [

36] emphasized the role of ideas and information in shaping industries and markets. Investing in knowledge creation and application can lead to developing valuable products and services. However, for a comprehensive assessment, potential issues such as equal access to knowledge and ethical concerns must be considered in the innovation process. Embracing these opportunities can contribute to personal improvement, higher incomes, and overall economic progress [

37].

Scholars in various fields are concerned with the challenges and opportunities present in these knowledge-based economies. Past research has mainly focused on the knowledge economy, including challenges and opportunities for economic growth and innovation.

A range of study resources offers a more comprehensive understanding of the key elements involved in this field. This research provides exciting viewpoints on challenges like workforce upskilling, new training methods, and differential resource allocations. Another achievement of these earlier works was to consider cyber security and data protection, issues of utmost importance within today’s electronic environment.

2.4. Purpose of the Study

To cope with the pressures of an evolving economy in Oman, Sultan Qaboos University (SQU) saw that it is its responsibility to prepare graduates accordingly. The country has transitioned to a knowledge-based, flexible economic model as formal education becomes increasingly rural–urban-balanced. Students have to be equipped with the skills and competencies to compete in a highly competitive high-tech environment if this system is to flourish. Liming the soil is critical for plant growth just as education is critical for economic development to meet that need and make certain graduates of SQU fit into tomorrow’s marketplace; this study aims to achieve the following goals:

Establish a clear-cut base pattern for current student skills as required by the knowledge-based economy.

Identify student abilities that need to be further developed so that SQU’s future graduates will be ready for tomorrow’s marketplace.

Develop recommendations and interventions to systematically enhance these identified student skills, aligning them with the demands of a dynamic, technology-driven global economy.

These three objectives are designed to prepare Sultan Qaboos University (SQU) graduates to steer Oman’s enterprise into the next stage of a knowledge-based, flexible economy.

2.5. Research Questions

Our study was guided by the following objectives, which we have reframed as questions to provide a clearer framework:

What is the current level of awareness and perception of knowledge economy skills among Sultan Qaboos University students?

Which factors significantly influence the enhancement of students’ knowledge-based economy skills?

How do students perceive the opportunities and challenges associated with the knowledge economy?

What is the relationship between higher education’s role and students’ awareness of knowledge economy skills?

These guiding questions aligned with our exploratory approach and informed our data collection, analysis, and discussion of results. While we did not formulate explicit hypotheses, our analysis was directed by these questions and the themes that emerged from our literature review.

3. Methodology

This study employed a quantitative research approach to assess and analyze students’ skills and perceptions related to the knowledge-based economy. Data were collected through a questionnaire distributed to students of Sultan Qaboos University (SQU). Sultan Qaboos University consists of 9 colleges, which include 52 academic programs with 16,263 students registered in all programs. We retrieved 282 valid responses from the students affiliated with Sultan Qaboos University. The survey covered various aspects, including demographic information, the awareness of knowledge-based economy skills, the perceptions of higher education’s role, and the impact of technology on education and employment. Most items in the questionnaire utilized a 5-point Likert scale, coded from 1 (Strongly Disagree) to 5 (Strongly Agree).

The survey received a 66.04 percent response rate (282 responses), with participants coming from various institutions at SQU. Most responses (54.4 percent) were from the College of Arts and Social Sciences. The sample included students of all ages and academic levels, including undergraduate and postgraduate, to ensure a varied representation of the university community.

Data were analyzed in two stages: a statistical analysis and inferential predictive analysis. Descriptive statistics were used in the statistical analysis to understand the sample’s structure and characteristics better. Demographic data were examined and presented using percentages and visual representations like pie charts and graphs. Cronbach’s alpha test was used to assess the reliability and internal consistency of the questionnaire’s scales.

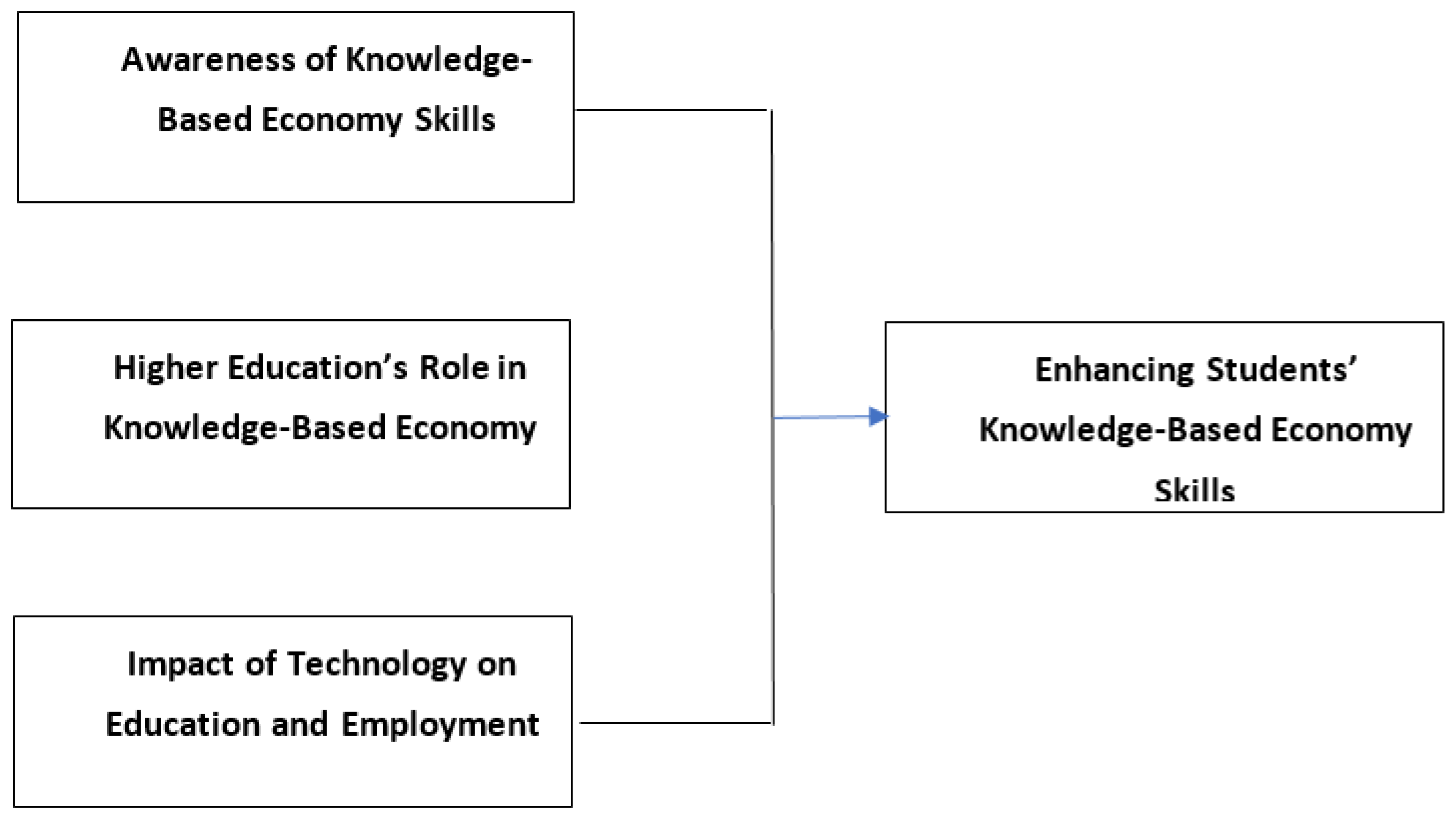

The inferential and predictive analysis included creating a model to investigate the relationships between variables. The independent variables included awareness of the knowledge-based economy (AWS), higher education’s involvement in the knowledge-based economy (HER), and the impact of technology on education and employment (ITEE). The dependent variable was improving the pupils’ knowledge-based economy skills (ESKBE). A correlation analysis was used to investigate the associations between variables, and a regression analysis was used to determine the predictive capacity of independent variables on the dependent variable.

The questionnaire was divided into sections that addressed various variables.

Section 2 focused on improving students’ knowledge-based economy abilities (ESKBE).

Section 3 addressed awareness of the knowledge-based economy (AWS) in questions 9–20 and higher education’s involvement in the knowledge-based economy (HER) in questions 21–29.

Section 5 (questions 30–36) examined the impact of technology on education and employment (ITEE).

This comprehensive methodology thoroughly examined students’ perceptions, skills, and the factors influencing their preparedness for a knowledge-based economy, providing valuable insights for addressing the study’s objectives.

4. Data Analysis

We aggregated questionnaire data into three independent variables and one dependent variable to analyze relationships between the key constructs. The awareness of the knowledge-based economy (AWS) was created by averaging responses to questions 9–20 in

Section 3. Higher education’s role (HER) was formed from questions 21–29 in

Section 3. The impact of technology on education and employment (ITEE) was derived from questions 30–36 in

Section 5. Our dependent variable, enhancing students’ knowledge-based economy skills (ESKBE), was constructed from

Section 2 responses. We calculated the mean score of relevant items for each variable, ensuring a consistent coding direction. We then conducted reliability analyses using Cronbach’s alpha to ensure internal consistency between these aggregated variables.

4.1. Demographic Information Descriptive Analysis

The data analysis in the current study was performed in two steps (statistical and inferential predictive analysis), starting with descriptive statistics, which were computed to understand the structure and description of the sample. The distribution of the acquired answers was dominated by male students, with 57.1%%, compared to the proportion of female students, who formed 42.9% of the overall targeted participants, as shown in

Table 1.

With a 66.04% response rate, the layout of the targeted sample was covered by different age groups, which was topped by participants who were (21–25)-year-old students in the university with 86.2%, followed by those who were below 20 years old with 10.3%, where the minimum percentages recorded for those students who were above 40 and were in higher education studies had a proportion of 0.4% as displayed in

Table 1.

Among these students, most were from the College of Arts and Social Science in the university, which had 54.4% of the overall students, as appears in

Table 1 above. The College of Science followed this with 12.4% and the College of Education with 11%. The Colleges of Law and Engineering participated minimally, with 2.5% and 2.1%, respectively.

With regard to the participants’ university levels, 44.33% of the students were from fifth and higher levels in the university, whereas 8.16% were participants who were in higher studies (master’s and PhD), as supported by

Table 1.

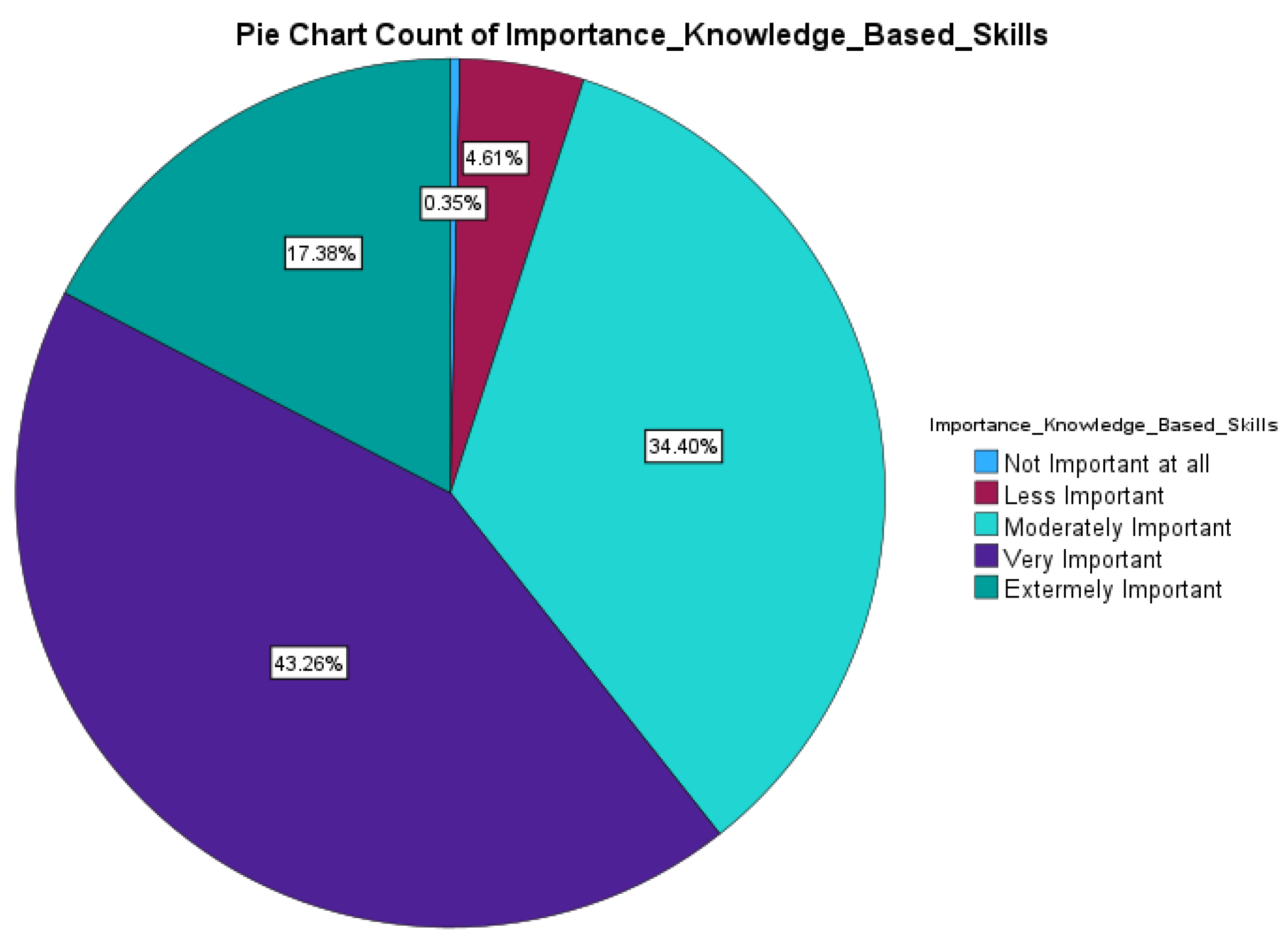

As for awareness about knowledge-based skills, more than half of the targeted sample were neutral about these skills, where those who had a background and those who did not know approximately shares the same proportions of 24.5% and 21.3%, correspondingly, where 43.3% of the participants believed that these knowledge-based skills are very important and 17% think they are essential. The distribution of the rest of the students’ opinions can be found in

Figure 1.

These participants ranked the skills and competencies that they believed are essential in a knowledge-based economy in the following order: creativity and innovation competency and critical thinking and problem-solving skills were ranked at rates of 85.82% and 85.11%, respectively, followed by information literacy at 73.76%. The ratios of communication and collaboration, technology literacy and adaptability, and flexibility are revealed in

Table 2.

4.2. Scale of Enhancing Students’ Knowledge-Based Economy Skills

Based on

Figure 2, the overall levels of enhancing students’ knowledge-based economy skills (ESKBE) were leveraged by the level of awareness of the knowledge-based economy (AWS), the impact of higher education’s role on a knowledge-based economy (HER), and the level of technology impact on education and employment (ITEE).

4.3. Cronbach’s Alpha

The influencing level of was tested by using a 5-point Likert scale as listed in the questionnaire, where they were coded with 1 = Strongly Disagree, 2 = Disagree, 3 = Neutral, 4 = Agree, and 5 = Strongly Agree. The awareness of the knowledge-based economy (AWS) was considered an independent variable covered by

Section 3’s questions, specifically questions 9 to 20. Higher education’s role in the knowledge-based economy (HER) was the second independent variable covered by

Section 3 from questions 21 to 29. The technology impact on education and employment (ITEE) was also an independent variable covered in

Section 5 from questions 30 to 36. Enhancing students’ knowledge-based economy skills (ESKBE) was considered a dependent variable of the aforementioned variables that are covered in

Section 2. The items listed in the pre-mentioned scale belonging to each variable scale were checked in terms of their reliability and internal consistency using Cronbach’s alpha test, which was measured using SPSS v.29, and the results are found in

Table 3. The selected items are closely related as a group for all the listed variables as shown in

Table 3 following what is statistically known; if the reliability coefficient is equal to 0.70 or higher, it is considered “acceptable” in most social science research.

4.4. Descriptive Analysis

From descriptive results as presented in

Table 4, all the items related to above model indicated suitability in terms of the agreement of the participants regarding the importance of the AWS, HER, and ITEE on ESKBE with averages located between 3.7 and 4.2 where there is influencing power from independent variables toward the dependent ones. Similarly, most of the items related to these variables’ std. deviation and variance had a normal range of the distribution and closeness to the average, ranging between a variance of (0.6–0.8) and a std. deviation of (0.5 to 0.8), which are close and in a normal distribution.

- a.

Inferential and predictive Analysis

Referring to

Table 5 and

Table 6, focusing on improving students’ awareness about the needed skills in a knowledge-based economy will enhance students’ knowledge-based economy future skills with a

p-value of <0.001 and a t-value of 4.201. Furthermore, investing more in technology’s impact and influence, specifically in education and employment, will enhance students’ skills in a knowledge-based economy with a

p-value of 0.030 and a t-value of 2.179. Although the higher education role shows little influence on students’ knowledge-based economy skills, it had a good correlation with students’ awareness about essential skills in a knowledge-based economy with an influencing power of 41.4%.

4.5. Opportunities in Knowledge Economies

Based on students’ opinions, most of the items were considered opportunities for the knowledge-based economy. A total of 55% believe it will have a positive impact on society, with an average of 4.1312, which is close to total agreement (Agree and Strongly Agree). Continuing to update skills and knowledge was considered a very important opportunity for the success of knowledge economies, as demonstrated in

Table 7.

4.6. Challenges in Knowledge Economies

Based on students’ opinions in

Table 8, most of the items were considered as challenges for the knowledge-based economy with 54.3% and an average of 4.1028 that if the governments and policymakers do not play a significant role in addressing the challenges of knowledge economies, it will have a negative impact in enhancing students’ knowledge-based economy skills. Following this, 53.5% of the students, with an average of 3.8511, pointed out that resistance to change is considered one of the most important challenges for individuals looking to participate in a knowledge-based economy. The rest of the challenges are highlighted in

Table 8 above.

5. Discussion

This study aimed to assess Sultan Qaboos University (SQU) students’ skills related to the knowledge-based economy, identify areas for improvement, and develop recommendations for enhancing these skills. The findings revealed several important insights that align with and extend existing literature on higher education’s role in preparing students for the knowledge economy.

5.1. Awareness and Perception of Knowledge Economy Skills

According to the study, a sizable proportion of students (54.2 percent) need clarification about their knowledge-based economy skills, with only 24.5 percent indicating a background in them. This finding is consistent with the research that emphasizes the need for higher education institutions to take a more active role in building students’ understanding and competencies for the knowledge economy [

2,

38,

39]. The fact that 60.3% of students believe these talents are very important implies that they are valued, even if they need clarification on their competencies.

Students identified creativity and invention (85.82%) and critical thinking and problem solving (85.11%) as the most important skills for a knowledge-based economy. This is consistent with the focus placed on these skills in the literature [

18,

19]. The lower rating of adaptation and flexibility (56.74 percent) is alarming, considering the continually changing nature of the information economy [

40].

5.2. Factors Influencing Knowledge Economy Skills

The study’s model revealed that awareness of the knowledge-based economy (AWS) and the impact of technology on education and employment (ITEE) significantly influenced the enhancement of students’ knowledge-based economy skills (ESKBE). This finding supports the argument that education systems need to adapt to cultivate skills essential for navigating the dynamic knowledge economy [

31].

Interestingly, while the higher education role (HER) had little direct influence on ESKBE, it strongly correlated (41.4%) with students’ awareness of essential skills. This suggests that higher education institutions play a crucial role in raising awareness about knowledge economy skills, even if their direct impact on skill development needs to be clarified. This finding adds nuance to the discussions by Marozau et al. [

41] and Godemann et al. [

42] about the multifaceted contributions of higher education institutions to economic development.

The complex relationship between higher education’s role (HER) and students’ knowledge economy skills deserves careful consideration. While HER showed a weaker direct impact on skill enhancement (ESKBE), its strong correlation with awareness (AWS) suggests an indirect influence. This finding aligns with Deiaco et al. [

7], who argue that higher education’s primary contribution to knowledge economy readiness may raise awareness and create a conducive environment for skill development rather than directly imparting these skills. However, it also raises questions about the effectiveness of current curricula and teaching methods in directly fostering knowledge economy skills. Future research could explore how specific aspects of higher education, such as internship programs, industry collaborations, or particular teaching approaches, might more directly influence skill development

5.3. Opportunities and Challenges

Students generally view the knowledge economy positively, with 55% agreeing that it will positively impact society. The strong agreement (52.5%) that the continuous updating of skills and knowledge is important for success aligns with previous literature that emphasised on lifelong learning.

While students comprehend major hurdles, opportunities also exist. To adequately address challenges like socially integrating education, knowledge management, and policy approaches, governments and policymakers require a unifying vision integrating diverse perspectives on technology’s role. As Kim and Park elucidated, concerns regarding job losses and wealth variances reflect probing examinations into how progression might disconnect specific industries from opportunities.

Resistance to fluctuation and constrained access to training perplex many. As affirmed over a decade past, continuously adapting skills and mindsets to technological waves remains vital [

43,

44]. This highlights how embracing diversity and reinventing what we teach can broaden participation. Overall, strategically steering technological courses while safeguarding societal fabric demands acknowledging students’ worries and building a shared future leveraging technology for all.

5.4. Implications and Recommendations

The study’s findings significantly affect how Sultan Qaboos University prepares its students for success in today’s society. Because student awareness levels were neutral, SQU must prioritize the implementation of comprehensive education campaigns emphasizing the importance of essential skills. Curriculums must also be thoroughly reviewed in order to clearly develop key skills such as creativity, innovation, critical thinking, and problem solving. Such changes coincide with the shift from traditional learning to competency development, as defined by Helmold and Helmold [

18]. Furthermore, technology’s considerable impact on education and careers influences student knowledge economy abilities, meaning that SQU should incorporate more technology into teaching. According to Martzoukou [

45], online possibilities should be boosted, and digital literacy training should be provided.

Even though technology is emphasized as a tool that can enhance learning outcomes when integrated into education, it is wise to consider the disadvantages, too. Excessive dependence on such tools may lead to the deterioration of important mental skills like problem solving and creative thinking [

46]. Seeking a more critical viewpoint in terms of how much technology should be incorporated or resisted within the teaching process may make it possible to achieve better educational outcomes.

Last but not least and with a particular emphasis on Sultan Qaboos University, the approaches and moderation strategies adopted in this study should be positioned in a global context. Understanding the position of SQU alongside such practitioners would help identify some of the attractive features and pitfalls in the teaching strategies for a knowledge-based economy.

To close the perceived gap between higher education and acquiring skills, SQU should expand industry linkages and provide practical, hands-on experiences. This is consistent with Fortunato and Alter’s [

32] emphasis on cultivating settings that encourage entrepreneurship and innovation. With a strong commitment to constantly upgrading skills, SQU must create and promote lifelong learning initiatives for alumni and the wider community, such as short courses, workshops, and online modules. Finally, the significant sentiment for government involvement suggests that SQU should actively engage policymakers in addressing knowledge economy concerns through partnerships, research collaborations, and policy proposals. By implementing these proposals, SQU can significantly improve student preparation for knowledge economy demands, thereby contributing to Oman’s economic growth and worldwide competitiveness.

6. Conclusions

This study provides valuable insights into the readiness of Sultan Qaboos University (SQU) students for the knowledge-based economy, highlighting both areas of progress and those requiring further attention. By examining students’ awareness, perceptions, and skills related to the knowledge economy, as well as the factors influencing skill development, this research contributes to the broader understanding of higher education’s role in preparing graduates for an evolving economic landscape.

The findings reveal a mixed picture of student preparedness. While there is a general recognition of the importance of knowledge economy skills, with a majority of students rating them as very or extremely important, there needs to be more confidence in their competencies. This gap between perceived importance and self-assessed ability underscores the need for more targeted educational interventions. The high ranking of creativity, innovation, and critical thinking skills aligns with global trends in the knowledge economy. Still, the lower emphasis on adaptability and flexibility suggests an area for improvement in curriculum design.

A key contribution of this study is identifying factors influencing enhancing students’ knowledge-based economy skills. The significant impact of awareness and technology integration on skill development provides a clear direction for educational policy and practice. While the direct influence of higher education on skill development was less pronounced, its strong correlation with skill awareness highlights universities’ complex and multifaceted role in the knowledge economy.

Our finding of a weaker direct impact of higher education on knowledge economy skill development, coupled with its strong influence on awareness, highlights the complex role of universities in preparing students for the knowledge economy. This suggests a need for higher education institutions to re-evaluate their approaches to skill development and consider how they can more effectively translate increased awareness into tangible skill enhancement.

The study also illuminates students’ perceptions of opportunities and challenges in the knowledge economy. Overall optimism about the knowledge economy’s positive impact is encouraging, as is the recognition of the need for continuous learning. However, concerns about job displacement, income inequality, and resistance to change reflect the complex realities of economic transformation and underscore the need for comprehensive strategies to address these challenges.

Based on our comprehensive analysis of students’ readiness for the knowledge-based economy, we propose evidence-based interventions to address the identified gaps and challenges: (a) Enhance curricula to develop key skills more explicitly. Our findings show that while students recognize the importance of skills like creativity and critical thinking, there is a gap in their perceived competence. This aligns with research by Ji [

47] and Abelha et al. [

48], who emphasized the need for intentional skill development in higher education curricula. (b) Improve awareness of knowledge economy demands. Our study revealed a significant relationship between awareness and skill enhancement. This supports Rodríguez and Lieber’s [

49] argument that an increased understanding of economic trends positively impacts student preparedness. Further integrating technology into educational practices, strengthening industry partnerships, promoting lifelong learning, and engaging with policymakers are all crucial steps. By implementing these recommendations, SQU can better equip its students with the skills and mindset needed to thrive in the knowledge economy.

This research also contributes to the broader academic discourse on higher education’s role in economic development. It provides empirical evidence supporting the need for universities to adapt their approaches in response to the knowledge economy’s changing demands while highlighting the complexities and challenges involved in this transformation.

Looking ahead, future research could explore the long-term outcomes of knowledge economy skill development initiatives, examine the effectiveness of different pedagogical approaches in fostering these skills, and investigate the interplay between higher education institutions, industry, and governments in creating a thriving knowledge economy ecosystem.

In conclusion, although the students of Sultan Qaboos University understand the significance of knowledge-based economy skills, there is still much work to be done in regard to developing educational approaches that will properly equip such students to face the challenges of the future. In other words, although there is a well-known knowledge economy framework that gives room for doing business/dynamic interactions, in order to overcome the present barriers, the education system needs to be altered, and skill development needs to be at the center with the needs of the economy in mind.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, N.E.E. and A.S.; methodology, A.S.; software, N.A.H.; validation, N.E.E.; formal analysis, N.A.H.; investigation, A.S.; resources, N.A.H.; data curation, N.A.H.; writing—original draft preparation, N.E.E.; writing—review and editing, A.S.; visualization, N.E.E.; supervision, N.E.E.; project administration, A.S.; funding acquisition, N.E.E. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Omani Ministry of Higher education grant number [BFP/RGP/EHR/22/041] and [RC/RG-ART/INFO/22/01].

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Sultan Qaboos University (RC/RG-ART/INFO/22/01) on January 2022.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data available upon request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Ahmad, T. Scenario based approach to re-imagining future of higher education which prepares students for the future of work. High. Educ. Ski. Work. Learn. 2020, 10, 217–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goulart, V.G.; Liboni, L.B.; Cezarino, L.O. Balancing skills in the digital transformation era: The future of jobs and the role of higher education. Ind. High. Educ. 2022, 36, 118–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phale, K.; Li, F.; Mensah, I.A.; Omari-Sasu, A.Y.; Musah, M. Knowledge-Based Economy Capacity Building for Developing Countries: A Panel Analysis in Southern African Development Community. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muzam, J. The Challenges of Modern Economy on the Competencies of Knowledge Workers. J. Knowl. Econ. 2023, 14, 1635–1671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roopchund, R. Understanding the contribution of human capital for the competitiveness of Mauritius. Int. J. Compet. 2017, 1, 119–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jami, Y.; Gökdeniz, I. The Role of Universities in the Development of Entrepreneurship. Przedsiębiorczość-Edukacja 2020, 16, 85–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deiaco, E.; Hughes, A.; McKelvey, M. Universities as strategic actors in the knowledge economy. Camb. J. Econ. 2012, 36, 525–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, R.; Aftab, R.; Siyal, S.; Zaheer, K. Entrepreneurial Higher Education Education, Knowledge and Wealth Creation. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2308.08808 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Arbo, P.; Benneworth, P. Understanding the Regional Contribution of Higher Education Institutions: A Literature Review; OECD: Paris, France, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Fortunato, M.W.; Alter, T.R.; Clevenger, M.R.; MacGregor, C.J. Higher educational engagement in economic development in collaboration with corporate powerhouses. In Business and Corporation Engagement with Higher Education; Emerald Publishing Limited: Leeds, UK, 2019; pp. 151–177. [Google Scholar]

- Giesenbauer, B.; Müller-Christ, G. University 4.0: Promoting the Transformation of Higher Education Institutions toward Sustainable Development. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abad-Segura, E.; González-Zamar, M.-D. Sustainable economic development in higher education institutions: A global analysis within the SDGs framework. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 294, 126133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kholiavko, N.; Popelo, O.; Melnychenko, A.; Derhaliuk, M.; Grynevych, L. The Role of Higher Education in the Digital Economy Development. Rev. Andal. Med. Deport. 2022, 15, e16773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chankseliani, M.; Qoraboyev, I.; Gimranova, D. Higher education contributing to local, national, and global development: New empirical and conceptual insights. High. Educ. 2021, 81, 109–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicholls-Nixon, C.L.; Valliere, D.; Gedeon, S.A.; Wise, S. Entrepreneurial ecosystems and the lifecycle of university business incubators: An integrative case study. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2021, 17, 809–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wasim, J.; Youssef, M.H.; Christodoulou, I.; Reinhardt, R. The Path to Entrepreneurship: The Role of Social Networks in Driving Entrepreneurial Learning and Education. J. Manag. Educ. 2024, 48, 459–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chankseliani, M.; McCowan, T. Higher education and the Sustainable Development Goals. High. Educ. 2021, 81, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helmold, M.; Helmold, M. New work as an opportunity for performance excellence. In New Work, Transformational and Virtual Leadership: Lessons from COVID-19 and Other Crises; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2021; pp. 19–30. [Google Scholar]

- Cobo, C. Mechanisms to identify and study the demand for innovation skills in world-renowned organizations. On the Horizon 2013, 21, 96–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilozubenko, V.; Yatchuk, O.; Wolanin, E.; Serediuk, T.; Korneyev, M. Comparison of the digital economy development parameters in the EU countries in the context of bridging the digital divide. Probl. Perspect. Manag. 2020, 18, 206–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alainati, S. The Role of Educational Systems in Developing the Twenty-First Century Skills: Perspectives and Initiatives of Gulf Cooperation Council Countries. IOSR J. Bus. Manag. (IOSR-JBM) 2024, 26, 44–57. [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong, T. The Best Schools: How Human Development Research Should Inform Educational Practice; ASCD: Alexandria, VA, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Lamb, S.; Maire, Q.; Doecke, E. Key Skills for the 21st Century: An Evidence-Based Review; NSW Department of Education: Surry Hills, NSW, Australia, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Nawaz, W.; Koç, M. Industry, University and Government Partnerships for the Sustainable Development of Knowledge-Based Society; Springer Nature: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2020; ISBN 9783030132286. [Google Scholar]

- Mazzarella, A. Human Capital, Research and Development and Structural Transformation: The Case of Portugal’s Failed Transition to a Knowledge-Based Economy (2000–2019); University Institute of Lisbon: Lisbon, Portugal, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Ambrogio, G.; Filice, L.; Longo, F.; Padovano, A. Workforce and supply chain disruption as a digital and technological innovation opportunity for resilient manufacturing systems in the COVID-19 pandemic. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2022, 169, 108158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewin, C.; McNicol, S. Supporting the development of 21st century skills through ICT. In KEYCIT 2014—Key Competencies in Informatics and ICT; University of Potsdam: Potsdam, Germany, 2015; pp. 181–198. [Google Scholar]

- Dagher, J.; Fayad, L. Business Process Reengineering: A Crucial approach for enhanced organizational sustainability. In Navigating the Intersection of Business, Sustainability and Technology; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2024; pp. 25–59. [Google Scholar]

- Tumusiime, E.I. Resource mobilisation and allocation priorities on knowledge production in universities in Uganda: An empirical study. Kabale Univ. Interdiscip. Res. J. 2022, 1, 31–47. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, W.; Yang, J.; Li, D.; Lyu, C. Knowledge sharing and knowledge protection in strategic alliances: The effects of trust and formal contracts. Technol. Anal. Strat. Manag. 2020, 32, 1366–1378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wingard, J.; LaPointe, M. Learning for Life: How Continuous Education Will Keep Us Competitive in the Global Knowledge Economy; Amacom: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Fortunato, M.W.; Alter, T.R. Embracing uncertainty and antifragility in rural innovation and entrepreneurship. In Building Rural Community Resilience Through Innovation and Entrepreneurship; Routledge: London, UK, 2022; pp. 91–116. [Google Scholar]

- Sum, N.-L.; Jessop, B. Competitiveness, the Knowledge-Based Economy and Higher Education. J. Knowl. Econ. 2013, 4, 24–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suciu, M.-C.; Drăgulănescu, I.-V.; Ghiţiu-Brătescu, A.; Picioruş, L.; Imbrişcă, C. Universities’ Role in Knowledge-Based Economy and Society. Implications for Romanian Economics Higher Education. Amfiteatru Econ. J. 2011, 13, 420–436. [Google Scholar]

- Kofler, I.; Innerhofer, E.; Marcher, A.; Gruber, M.; Pechlaner, H. The Future of High-Skilled Workers: Regional Problems and Global Challenges; Springer Nature: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- North, K.; Kumta, G. Knowledge Management: Value Creation Through Organizational Learning; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- De Silva, M.; Howells, J.; Meyer, M. Innovation intermediaries and collaboration: Knowledge–based practices and internal value creation. Res. Policy 2018, 47, 70–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halberstadt, J.; Timm, J.-M.; Kraus, S.; Gundolf, K. Skills and knowledge management in higher education: How service learning can contribute to social entrepreneurial competence development. J. Knowl. Manag. 2019, 23, 1925–1948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leal Filho, W.; Vargas, V.R.; Salvia, A.L.; Brandli, L.L.; Pallant, E.; Klavins, M.; Ray, S.; Moggi, S.; Maruna, M.; Conticelli, E.; et al. The role of higher education institutions in sustainability initiatives at the local level. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 233, 1004–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, L.N. The Impacts of the Black Swan COVID-19 in the Perspectives of Higher Education: Survey Research and Applicable Leadership Strategies for the Private Education Ecosystem. Master’s Thesis, IUBH International University of Applied Sciences, Berlin, Germany, 30 September 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Marozau, R.; Guerrero, M.; Urbano, D. Impacts of Universities in Different Stages of Economic Development. J. Knowl. Econ. 2021, 12, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godemann, J.; Bebbington, J.; Herzig, C.; Moon, J. Higher education and sustainable development: Exploring possibilities for organisational change. Account. Audit. Account. J. 2014, 27, 218–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cowan, R.; David, P.; Foray, D. The explicit economics of knowledge codification and tacitness. Ind. Corp. Chang. 2000, 9, 211–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winch, C. Education and the Knowledge Economy: A Response to David & Foray. Policy Futur. Educ. 2003, 1, 50–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martzoukou, K. Academic libraries in COVID-19: A renewed mission for digital literacy. Libr. Manag. 2021, 42, 266–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, C.; Wibowo, S.; Li, L.D. The effects of over-reliance on AI dialogue systems on students’ cognitive abilities: A systematic review. Smart Learn. Environ. 2024, 11, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, Y. Embedding and Facilitating Intercultural Competence Development in Internationalization of the Curriculum of Higher Education. J. Curric. Teach. 2020, 9, 13–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abelha, M.; Fernandes, S.; Mesquita, D.; Seabra, F.; Ferreira-Oliveira, A.T. Graduate Employability and Competence Development in Higher Education—A Systematic Literature Review Using PRISMA. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, S.; Lieber, H. Relationship Between Entrepreneurship Education, Entrepreneurial Mindset, and Career Readiness in Secondary Students. J. Exp. Educ. 2020, 43, 277–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).