Abstract

Massive Open Online Courses (MOOCs) provide borderless opportunities to engage with content and ideas, with prospective participants from around the globe being able to easily register. The course featured in this study focused on the social and emotional well-being of adolescents, selected because of a recognized need for professional learning related to this topic. It was purposely designed for delivery as a MOOC and was designed as a 6h program around four topics to be completed over two weeks in asynchronous mode. It was delivered seven times from 2019 to 2023, with 32,969 individuals enrolled across these deliveries. The effectiveness of engaging in the course for professional learning purposes is of particular interest to this study. To that end, a convergent mixed methods study was conducted. First, quantitative and qualitative survey data collected at various course stages were examined to reveal the demographic characteristics of participants and their experiences in the course using data from surveys and comments about their experiences. The findings revealed, among other factors, that 65% were female, with just under half (47%) aged 45 years or less, nearly half (44%) held a bachelor’s degree as their highest level of qualification, and 48% were employed within the teaching and education sector. The most active learners were from Europe (48%) and Asia (27%), with active learners from a total of 178 countries. The course has a high course retention index, with 51% of learners completing 51% of the course and 8383 learners completing 90% or more of the course. The qualitative findings reveal the strongly positive experiences reported by the active participants. Secondly, we examined the effectiveness of the MOOC for participants’ professional learning needs by assessing the course using a framework with ten domains related to its core design features, modified for use by the course designers as a self-reflective tool. We found that the domains that scored the lowest were collaboration, interactivity, and, to a lesser extent, pedagogy. The study’s limitations include the incomplete data provided as part of the MOOC protocols, and the use of a self-reflection tool, which may inadvertently incorporate bias. This study points to these gaps in the data, including the need to access longitudinal data that go beyond a focus on the design of courses to extend to the impact and outcomes of the experience.

1. Introduction

Increasingly, well-being is a focus for those who have a vested interest in the positive outcomes of young adolescents in schools, organisations, and other contexts [1]. Although the term well-being is defined differently across disciplines (e.g., medicine, psychology, sociology, philosophy, etc.), the World Health Organization [WHO] recently added the term ’well-being‘ to its glossary of terms, defining it as, ‘a positive state experienced by individuals and societies. Similar to health, it is a resource for daily life and is determined by social, economic, and environmental conditions’ [2] (p. 10). The definition is elaborated with the following explanation:

Well-being encompasses quality of life, as well as the ability of people and societies to contribute to the world in accordance with a sense of meaning and purpose. Focusing on well-being supports tracking the equitable distribution of resources, overall thriving, and sustainability. A society’s well-being can be observed by the extent to which they are resilient, build capacity for action, and are prepared to transcend challenges [2] (p. 10).

According to the WHO’s definition of well-being, an individual’s ability to adjust to and thrive in their environment is crucial for their overall well-being. Furthermore, empirical evidence has consistently demonstrated a direct correlation between a person’s capacity to handle life’s challenges and their level of social and emotional skills [3]. Developing effective social and emotional skills is essential not only for individuals but also for communities and societies at large [3].

Social and emotional issues have been recognised as being central to many of the problematic behaviours of young adolescents, which concern schools, communities, and families [4]. Often, a young person’s lack of social and emotional skills can adversely affect their social or learning environment and diminish their own hopes and future opportunities [5]. Recognised as teachable competencies, strong social and emotional skills (SESs) enable individuals to manage stress, regulate behaviours and emotions, build confidence and a sense of efficacy, and develop and sustain relationships based on mutual respect and trust [6]. Therefore, a strong foundation of social and emotional skills is essential for personal well-being.

Over the past 30 years, our understanding of the complexity, risks, and opportunities that occur during adolescence has grown significantly [7]. Consequently, there is a growing emphasis on the need for those who interact with adolescents to understand their distinctive developmental traits as well as the opportunities this window of development affords. Recent neuroscience research has highlighted the increased plasticity of the brain during this period, presenting a crucial second window for young people to develop and enhance their social and emotional skills [8,9]. However, worryingly, there is also a new generation of young adolescents who are experiencing both a generational shift and health consequences driven by technology [10,11]. Constant technology use is shown to have a notable impact on the developing brain, leading to different emotional responses, altered brain functions, and less developed social and emotional skills compared to previous generations [10,12,13]. For many professionals working with this age group, these changes present relational and instructional challenges they may not feel fully equipped to handle.

Research has consistently shown the benefits of positive relationships with young adolescents, including an improved sense of well-being, improved academic outcomes, and a greater sense of belonging [14,15,16]. However, to build and capitalise on such relationships, it is critical for adults who work with these young people to understand the context in which they are working and acknowledge that all young adolescents experience unique social and emotional struggles [4]. Yet, for many who work closely with young adolescents, access to quality professional learning is a significant barrier [17]. Developing quality professional learning for adults also requires careful consideration, built upon practices suitable for adult learners. This paper reports on a professional learning program that aimed to overcome the barriers highlighted above.

Accessible, Quality Professional Learning for Adults

Effective professional learning for adults is of great importance, especially given the resourcing implications such as time, cost, and equitable access, along with the expectation that enhanced effectiveness and outcomes are linked to effective professional learning [18]. Adult learning theories, including Knowles’ [19] highly regarded and well-established notion of andragogy, characterise adult learners as self-directed and internally motivated, bringing experience to the learning process and thriving in collaborative and applied approaches, exhibiting goal orientation. Andragogy is distinct from pedagogy, which has children as learners as the focus. Similarly, Kolb’s Experiential Learning Theory (1984) [20] points to the importance of recognising adults’ experiences as foundations for learning, with cycles built upon experience, reflection, and active experimentation enhancing adult learning. These, and more recent adult learning theories, highlight the importance of considering the motivation, experience, and purpose of adult learning, as well as the importance of self-directed learning opportunities and experience-based approaches.

In addition to andragogy as a consideration for accessible, quality professional learning for adults, historical research also informs the core design features of effective professional learning (see, for example, Desimone, 2023 [21]), which focuses on a description of the processes involved in professional learning alongside the participants’ feelings about the activity. However, this does not go far enough to link the professional learning with outcomes and impact, which usually requires a focus on changes in the participants’ self-efficacy. Establishing this link is not always practical, and hence the default evaluation tends to focus on the features of the professional learning itself that are most likely to lead to changes in behaviour.

Main and Pendergast (2020) [22] conducted a systematic quantitative literature review to examine the approaches, methods, and technology used, along with the main research findings, of professional learning for teachers in the middle years for the period 2000–2018. Middle years teachers work directly with adolescent learners, and hence are connected to this study through the content of the MOOC. The review revealed that just 33% of the studies included considerations of measures of impact, calling out for the importance of including measurable factors that can be considered when designing professional learning. This points to the gap in the literature that this study set out to address, that is, the effectiveness of MOOCs as a form of professional learning. This is increasingly important given the rapid shift in technology available for the delivery of professional learning.

With the rise in digital technology and its ability to transcend time and space, online professional development has grown in popularity. One such form of online professional development is Massive Open Online Courses (MOOCs). MOOCs emerged out of the open educational resources movement [23]. Since the first MOOC offering in 2008, they have transformed the landscape of education by offering free or low-cost access to courses from many of the most respected higher education institutions across the globe. MOOCs have continued to grow in popularity with a significant surge since the COVID-19 pandemic. The participation rates in MOOCs increased during the COVID-19 pandemic period when access to professional learning through other means was more restricted, bringing many learners to the free, online courses. An analysis by Shah (2020) reports that one-third of learners who have registered for a MOOC at any time did so in 2020, following a relatively stagnant growth in the preceding years. According to the data available at the time, 950 universities globally participated in the delivery of more than 16,000 MOOCs to more than 180 million participants around the world in 2020. Education and training-related topics represent almost eight percent of course types [24].

MOOCS have several advantages over more traditional forms of professional development and learning. Being fully online, MOOCs remove the restrictions of time and space; they are also efficient to produce and deliver and are generally short, stand-alone courses. As stand-alone courses, they rely on the community of learners enrolled in a particular MOOC to engage with each other and exchange ideas. MOOCs are also not limited by scale in that thousands of learners can be enrolled and learning in a MOOC at the same time [25].

With an almost 20-year history of delivering MOOCs, evaluating their effectiveness has become a key focus for researchers and for those who design and deliver them. In 2015, Gamage et al. [26] noted that ’MOOCs are dominating the eLearning field…and yet not all meet the goals of the user‘ (p. 1). In a review of the literature around MOOC quality, Gamage et al. developed a framework to analyse the effectiveness of MOOCs from the learners’ perspective. The result was a ten-dimensional framework with 41 items. The ten key dimensions are as follows: (i) technology, (ii) pedagogy, (iii) motivation, (iv) usability, (v) content/material, (vi) learner support, (vii) assessment, (viii) future direction, (ix) collaboration, and (x) interactivity. Each item is rated on a Likert Scale from 5 = strongly agree to 1 = strongly disagree. As the designers and facilitators, the aim of this study was to consider how effective a purpose-built MOOC could be to meet the professional learning needs of its participants, thereby addressing the established gap in the literature. To achieve this, the study had the following research questions:

- What is the nature of the participants and their level of engagement in the MOOC?

- What is the reported experience of the participants?

- How effective was the MOOC as a professional learning tool?

2. Background

2.1. The MOOC: Supporting Adolescent Learners—Social and Emotional Well-Being

FutureLearn is one of the many MOOC providers, with 15 million learners and 1158 courses in 2020 [27]. Generally, FutureLearn classes can be completed for free; however, for Certificates and credits, some payment is required. Griffith University is a FutureLearn partner, and together they have offered the course—Supporting Adolescent Learners: Social and Emotional Well-being [28]—over several years and several iterations. The course is aimed at anyone in a role that supports young adolescents (parents, teachers, youth leaders, guidance officers, and counsellors). The MOOC was designed for delivery over two weeks (one module per week), with a weekly study expectation of three hours (six hours total). The course is free to join, and participants have four weeks to complete the modules, which include videos, readings, quizzes, and activities that are all aimed at building their understanding of the topics covered. The MOOC is facilitated by the course developers during the first two weeks of the course offering. The course description can be viewed in Figure 1a. The topics covered in the MOOC include the following:

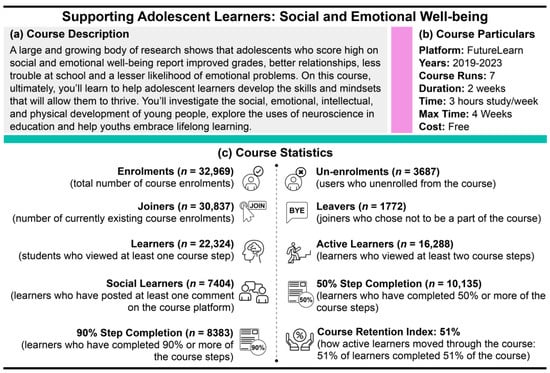

Figure 1.

Course description, particulars, and statistics. (a) The ‘Supporting Adolescent Learners: Social and Emotional Well–being’ course description presented on the course landing page (see [26]); (b) the course particulars indicating course timing, runs, and cost; (c) course statistical data including a description of the FutureLearn language (see [29]).

- Lifelong learning as the context for understanding young adolescents with an imperative for developing a new learning mindset for 21st century learners;

- Developing an understanding of young adolescent learners through the domains of social, emotional, intellectual, and physical development;

- A focus on the second sensitive period of brain development and the impact of neuroscience on learning, with a particular focus on social and emotional implications and cognitive engagement;

- Developing capabilities to enhance social and emotional well-being, highlighting elements such as empathy, resilience, and self-regulation [26] (para.4) (see Figure 1a,b).

The data provided by FutureLearn regarding course enrolments, unenrolment, and student course progress for all seven courses run between 2019 and 2023 (see Figure 1b) indicated that 32,969 individuals enrolled in the course, with 22,324 moving forward to view at least one step of the program. The course was completed by 8383 learners, with 51% of the 22,324 learners completing at least 51% of the course. Figure 1c details the course statistics and defines the specific language FutureLearn uses to describe its students, which will be reflected in this article.

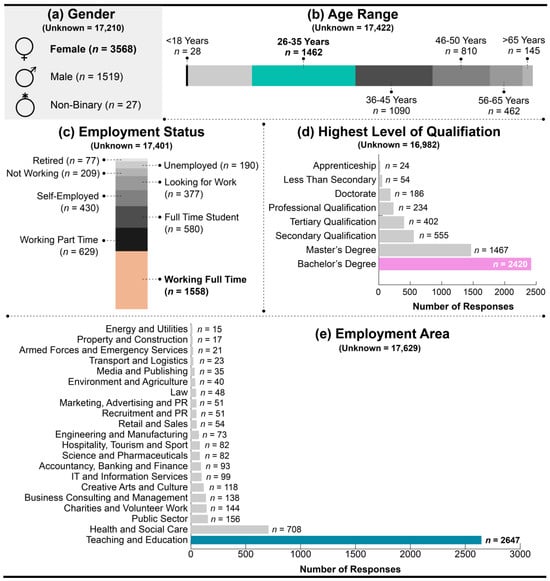

FutureLearn collects student demographic data via a survey upon registration with the platform [30,31]. As the survey is optional, limited information was collected, as only 25% (n = 5513) of learners voluntarily responded to the demographic questionnaire. Of the respondents, 65% were female, 47% were aged 45 years or less, and 28% were employed full-time (see Figure 2a–c). Nearly half (44%) held a bachelor’s degree as their highest level of qualification, and 48% were employed within the teaching and education sector (see Figure 2d,e).

Figure 2.

Student demographics. (a) The proportion of learner genders; (b) the age range of learners in the course; (c) the employment status of learners; (d) the highest level of qualification of learners; (e) the range of learner employment areas.

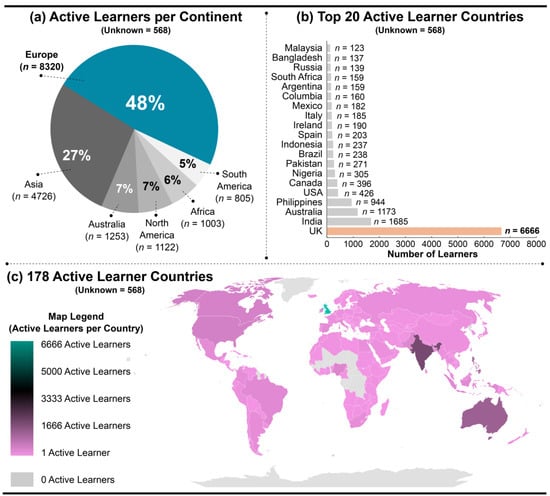

The MOOC had an extensive international geolocational reach. FutureLearn detected the 16,288 active learners’ (see Figure 1c) country of origin through the IP address of their computers when they enrolled in the course, with n = 568 remaining unknown. The majority of active learners were from Europe (n = 8320, 48%) and Asia (n = 4726, 27%) (see Figure 3a), and the top three countries included the United Kingdom (n = 6666), India (n = 1685), and Australia (n = 1173) (see Figure 2b). Active learners were identified to originate from 178 countries overall, with Figure 3c highlighting the extensive geolocational reach of the MOOC.

Figure 3.

Course geolocational reach. (a) The proportion of active learners per continent; (b) the top 20 active learner countries; (c) active learner country spread.

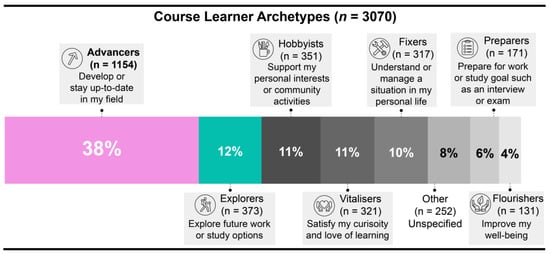

When learners enrol in a course, they are sent an optional multiple-choice survey to determine their ‘archetype’ [30]. A learner’s archetype reflects their motivation to undertake the course that they have enrolled in [29]. Career-based archetypes encompassed 50% of the learners in this course, with advancers (38%), who enrol for professional development, being the most common. The proportion of each archetype alongside the multiple-choice options provided within the optional survey is presented in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Learner archetypes.

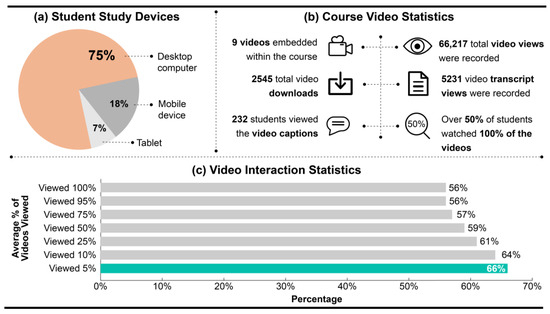

FutureLearn also collects data regarding the use of technology by the learners. The majority of learners interacted with the MOOC from a desktop computer (75%), with 18% using a mobile device (see Figure 5a). The learners also engaged heavily with the nine embedded videos, which were viewed 66,217 times, indicating that learners were inclined to view each more than once. Many learners accessed the video transcripts (n = 5231), and n = 232 students used the video captions (See Figure 5b). All nine videos were 100% viewed by 56% of learners (see Figure 5c). These data highlight the importance of the optimisation of courses for desktop computers and mobile devices, while also embedding multimedia to engage students.

Figure 5.

Student devices and multimedia interaction. (a) The devices students used to study the course; (b) course video statistics; (c) the video interaction statistics.

Research about one of the deliveries of the MOOC during the COVID-19 pandemic has been published elsewhere (see [32]). This study examined data from more than 16,000 participants engaged in a single delivery of the MOOC at the peak of the pandemic. The study found that, ‘[O]verwhelmingly those who participated in the MOOC appreciated the opportunity to learn and found the content relevant and useful. Importantly, MOOCs can provide a socially just approach to offering PD without the constraints of time and space or socio-economic boundaries‘ (p. 300).

2.2. The Study

Within the context of personal and professional learning, this research aimed to examine insights from the delivery and potential impact of a Massive Online Open Course (MOOC) on the topic Supporting Adolescent Learners: Social and Emotional Well-being. The study includes all participants engaged in the seven course iterations with 32,969 total enrolments and 22,324 actual participants, providing a rich data set for the study. The research questions guiding the investigation were as follows:

- What is the nature of the participants and their level of engagement in the MOOC?

- What is the reported experience of the participants?

- How effective was the MOOC as a professional learning tool?

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Methodology

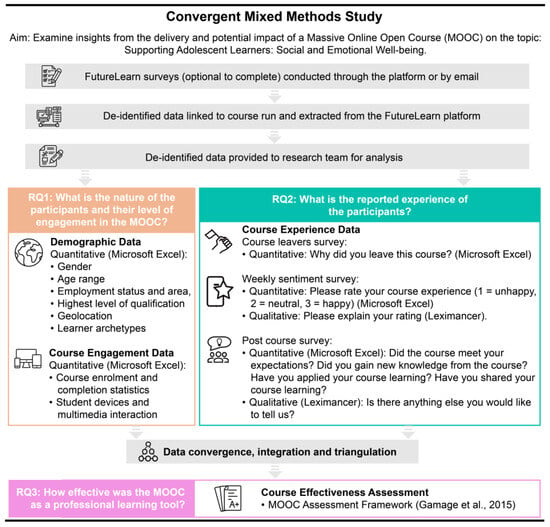

A convergent mixed methods study was conducted by analysing quantitative and qualitative survey data collected at various course stages, followed by triangulation [33] to provide evidence for assessing the MOOC’s eLearning effectiveness (see Figure 6).

Figure 6.

The convergent mixed methods study design.

3.2. Participants

The data used for this study were based on all students who enrolled in the Supporting Adolescent Learners—Social and Emotional Well-being MOOC (for demographic details, see Figure 1, Figure 2 and Figure 3). FutureLearn manages student enrolments, payments, and data collection, hence, the data extracted from its platform are non-identifiable to the course administrators and researchers conducting this study; hence, ethics approval was not required.

3.3. Data Collection

The survey was developed and administered by FutureLearn as part of the usual course delivery protocols. The researchers did not have access to the survey. FutureLearn determined the survey questions, which collected quantitative demographic data, yes/no/not sure questions and categorised responses, and qualitative free-text responses. FutureLearn delivered the survey questions at various course stages through the MOOC platform and by email. They were optional for learners to complete, and all responses were anonymous. The nature of the instruments used to collect data is presented in Figure 6, along with the alignment of the data generated with the research questions guiding this study. The course administrators extracted the survey data from the FutureLearn platform. The data for each survey question was supplied independently of demographic or identifying details and was only linked to the run that it applied to (see Figure 6).

3.4. Data Analysis

Once extracted from the FutureLearn platform, the data were checked for completeness, looking for empty lines, responses written in English, and actual responses recorded, not just dots or ‘NA’. Empty lines and non-useful responses were removed, and non-English responses were translated into English. The data were coded with the run number, appearing as ‘Rx’ in the study results, and an identification number for each response for each survey question. Microsoft Excel (v.16.89.1) was used to analyse the quantitative survey data, including demographics, student interaction statistics, and course leavers and post-course surveys (see Figure 6). As most of these data were used to respond to research question 1—What is the nature of the participants and their level of engagement in the MOOC?—data were analysed using descriptive statistical methods.

The qualitative data generated from the free-test response weekly sentiment and post-course surveys were inductively analysed [34] using Leximancer and Microsoft Excel software. The cleaned and coded data were organised into .csv files according to each research question and uploaded to Leximancer v4.51.07. Leximancer applies content and relational analysis strategies by quantifying frequently occurring terms and how they co-occur. The outcomes are displayed within a concept map arranged to highlight the dominant themes and concepts identified within the analysed text while illustrating how they intersect.

Leximancer identifies concepts based on the most frequently occurring words within the analysed text. Concepts appear within the concept map next to grey circles, with larger circles indicating a high frequency of appearance. Interconnecting grey lines link frequently co-occurring concepts, highlighting their intersecting relationships. The themes, which are represented in the results in italicised text, group the most frequently co-occurring concepts within coloured circles to highlight their frequent connections within the analysed text. Although concepts are linked to the themes they most frequently appear with, they can also link to other concepts and themes, which can be traced through the interconnecting line network [35].

The theme circles are heat mapped according to their dominance within the analysed text (most dominant—red, pink, orange, yellow, green, teal, blue, purple—least dominant). The theme name is presented in capitalised black text within the concept map and is accompanied by descriptive frequency and percentage statistics. The concepts are written in lowercase black text [35].

Following the Leximancer analysis of the free text responses to identify the overarching themes and concepts, Microsoft Excel was used to transform the data from qualitative to quantitative [33]. The free-text responses and their coding were inserted into Microsoft Excel alongside the identified themes to (a) determine frequencies, (b) extract quotes to contextualise the quantitative results, and (c) inductively interpret the identified themes to report the results (see Figure 6).

3.5. Data Convergence, Integration, and Reporting

The quantitative and qualitative survey results were converged, integrated, and triangulated [33,34] to report on the results and assess the MOOC eLearning effectiveness. The MOOC assessment framework developed by Gamage et al. (2015) [26] was adapted to act as a self-reflective analytical tool to undertake this analysis. This tool, and the self-reflection process, will be discussed further in the results.

4. Results

To address the research questions and assess the effectiveness of the MOOC as a professional learning tool, multiple forms of FutureLearn data were extracted from the system and analysed. This section will present these analyses, including the course leavers survey, weekly sentiment survey, and post-course quantitative and qualitative surveys, which will inform the MOOC eLearning effectiveness assessment guided by the framework by Gamage et al. (2015) [26].

4.1. Course Leavers Survey

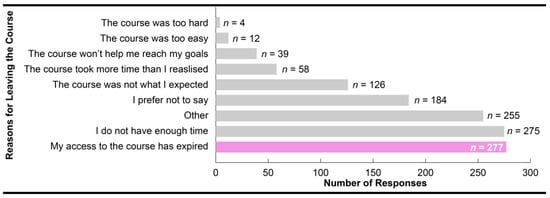

As reported, there were n = 1772 leavers, and 69% (n = 1230) responded to a multiple-choice question indicating their reason for doing so. Most students left the course due to their course access expiring (23%), not having enough time (22%), or other reasons unspecified (21%). Less than 1% left because the course was too hard or too easy, and 3% indicated that it would not help them achieve their goals (see Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Student reasons for leaving the course.

4.2. Weekly Sentiment Survey

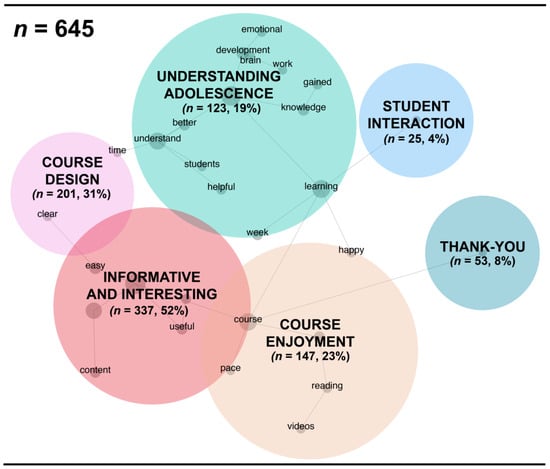

Learners could opt to respond to an optional weekly sentiment survey at the end of week one of the course to rate their course experience (1 = unhappy, 2 = neutral, 3 = happy) and explain their rating through a free-text response [30] (FutureLearn, 2022). Of the n = 1788 responses, 93% (n = 1667) were rated as happy, 6% (n = 102) were neutral, and 1% (n = 19) were unhappy. The mean rating was 2.9 (SD = 0.3, Mode = 3). The free-text responses (n = 645) explaining these ratings were analysed using Leximancer to identify the dominant themes within the responses (see Figure 8). The dominant themes included informative and interesting, course design, course enjoyment, understanding adolescence, thank-you, and student interaction. Each of these themes will now be contextualised in turn.

Figure 8.

Leximancer weekly sentiment free-text analysis.

4.2.1. Theme 1: Informative and Interesting

The interesting and informative theme indicated that 52% (n = 337) of learners found the course to be ‘…very interesting…’ (7, R1) and ‘…informative…’ (26, R2). Multiple learners reported that the ‘…information is very interesting…’ (12, R1) and ‘…useful…’ (10, R1) which helped learners to ‘…obtain new knowledge that will make us grow as people and even more as human beings’ (44, R2). The ‘…informative…’ (48, R2) course content was also described as ‘…very insightful…’ (68, R3), ‘impactful’ (83, R4), ‘…educative’ (282, R2), ‘…very specific’ (412, R4), ‘…detailed.’ (510, R4), ‘…engaging…’ (152, R4), ‘…in depth…’ (166, R4), ‘…thoughtful…’ (135, R4), and ‘…accurate and useful…’ (139, R4).

Respondents also indicated that the course content provided a ‘..good theoretical background and practical insights…’ (49, R2) through the ‘…scientific knowledge…’ (70, R3) presented. Respondents also reported they obtained ‘…new information…’ (94, R4), which left some learners feeling ‘…FULLY INFORMED AND ENLIGHTENED!’ (196, R4). Some respondents attributed this to the presented content being ‘…interesting and engaging’ (204, R4) alongside the content being explained through ‘Wonderful explanations, detail and variety of theories and opinions…’ (586, R5), which ‘…greatly expanded…’ (254, R4) learner knowledge.

Although the responses within this theme were predominantly positive, n = 4 responses were neutral to negative in sentiment. One respondent stated that they did not experience ‘…a lot of learning’ (56, R3), and another found the content to be ‘Quite basic, beginner knowledge. Not a very practical course so far’ (59, R3). It was reported by another respondent that they ‘…did find it hard going perhaps I was trying to analyse everything too much.’ (224, R4), while another stated that they ‘…may have been expecting a ‘wow’ moment of discovery… there is just confirmation of what I already know…’ (362, R4).

4.2.2. Theme 2: Course Design

The course design theme was reported on by 31% (n = 201) of respondents. Learners found the course to be ‘…well presented…’ (4, R1) and very ‘…clear and well-paced. Nice and explicit’ (5, R1). Respondents liked that the course was ‘…accessible…’ (123, R4) and they could access it ‘…in my own time…’ (9, R1), making it ‘…easy to pick up and put down whenever you are ready to participate’ (424, R4). They also reported that it was ‘…easy to navigate…’ (17, R1), ‘…read…’ (14, R1), and ‘…understand’ (80, R4) while containing ‘relevant and latest research’ (6, R1).

Respondents also liked that ‘…some difficult, esoteric concepts were reframed in layman’s terms’ (23, R2), which made the course ‘…informative without over-loading…’ (159, R4). Complementing this were reports of the course being ‘…presented in thinkable portions’ (28, R2) and ‘… well-paced…’ (236, R4) which enabled learners to ‘…work at your own pace’ (157, R4). Other perspectives included that the course was ‘…nicely structured’ (82, R4), well ‘…organised, straightforward…’ (113, R4), and ‘…concise and to the point…’ (597, R6). As ‘…distance is not a problem for people to study today…’ (358, R4), the online platform was seen as beneficial.

In particular, respondents gave positive feedback on the ‘…variety of learning tools included…’ (4, R1) and ‘…multi-sensory learning…’ (202, R4) through ‘…the cycle of articles, videos and discussion questions’ (603, R6) which made the course enjoyable. In particular, the use of videos was discussed by n = 19 respondents as being beneficial for learning and that it was ‘really useful being able to watch the video presentations at my own pace, pausing, rewinding etc…’ (502, R4). The learners also enjoyed ‘…the succinct lessons… and how often we were encouraged to reflect on this week’s course topics’ (20, R2).

Many respondents referred to ‘…the links…’ (62, R3) embedded in the course, which provided ‘…good signposting to further resources’ (88, R4). This left many respondents ‘…really impressed with the way in which the course is structured…’ (187, R4). The course workload was reported to consist of ‘…manageable chunks of work…’ (202, R4), with learners enjoying the opportunity to ‘…share thoughts with fellow learners’ (203, R4) through discussion forums.

The neutral to negative responses (n = 6) expressed that a very small proportion of learners expected the course to be ‘more practical…’ (1, R1) and that there was ‘…a little too much reading…’ (589, R5). One respondent reported that they were ‘…rushing as access runs out…’ (43, R2), and another found the course to be ‘…a bit more basic than I was hoping for it to be, and it assumes a lower level of knowledge surrounding adolescent development than I think most teachers would already have…’ (117, R4). One respondent who disclosed they live with ADHD reported they ‘…found it difficult to focus on reading the articles and long-winded passages. Simplifying the language would be helpful’ (116, R4).

4.2.3. Theme 3: Course Enjoyment

The course enjoyment theme was discussed by 23% (n = 147) of respondents from a primarily positive perspective. This theme encompassed a multitude of responses indicating that learners experienced course enjoyment, for example, the ‘…course is absolutely fascinating’ (325, R4), ‘…amazing…’ (285, R4), ‘Awesome!’ (595, R4), ‘…enjoyable!’ (583, R5), ‘Excellent’ (351, R4), ‘…wonderful and enlightening…’ (134, R4), ‘…excited…’ (585, R5), ‘Amazing learning experience’ (93, R4), ‘Great experience’ (615, R6), the ‘…learning is fun’ (494, R4), ‘…enriching…’ (483, R4), and ‘…valuable and worthwhile’ (21, R2). Although the majority of responses within this theme were positive in sentiment, only two comments diverged, which were, ‘Not bad…’ (300, R4) and ‘it is quite boring’ (527, R4).

4.2.4. Theme 4: Understanding Adolescence

When discussing the understanding adolescents theme, respondents (n = 123, 19%) indicated that due to an increased understanding of the developmental science of adolescence and the associated behaviours linked to this life phase, they were able to interact with adolescents more effectively. This was attributed to ‘…gaining more insight about adolescence different from my personal perspective’ (169, R4), which changed the way respondents viewed their ‘…adolescent students’ (180, R4) and ‘…how I should react to teenagers in the future’ (193, R4).

Understanding adolescent development was explicitly discussed by 11% (n = 70) of respondents. These respondents expressed that learning about ‘…each part of the brain and how it functions… has given me a better understanding why adolescents do what they do’ (281, R4). Specific course content was also discussed positively including, ‘…growth mindset and lifelong learning and how they relate to neurological processes and other aspects of adolescent development’ (433, R4), ‘…physical, emotional, social and cognitive development…’ (124, R4), ‘…emotional and well-being of adolescents…’ (600, R6), ‘…changes in the adolescent brain are and how this can affect their responses’ (334, R4), and the ‘…neuroscience…’ (505, R4).

It was indicated by n = 24 respondents that this enhanced understanding of adolescent development helped them to ‘…understand adolescents’ emotional responses/behaviour…’ (416, R4) which ‘…explains much conflicting behaviour I’ve seen in my students and which I have often and sadly misinterpreted’ (364, R4). It was also understood that ‘…adolescents and adults do not think alike…’ (607, R6) which was appreciated as the reason why ‘…teenagers react differently to others as compared to young children and adults’ (606, R4).

Respondents (n = 42) also indicated that through the combined understanding of adolescent development and its associated behaviours they were able to improve their interactions with adolescents at home and at work. This combined knowledge was reported to help the learners ‘…support them during this period…’ (438, P4) as the course ‘…equips you to be a better educator, parent etc. by providing factual information…’ (307, R4). It was also reported that the course helped learners to ‘…revaluate how I interact with adolescence and how I could improve upon this interaction…’ (127, R4) and ‘…think about strategies and skills to treat adolescent students well and help them to grow’ (57, R3). It was recognised that if adults did not ‘…stigmatize…’ (480, R4) adolescents, they could work towards ‘…improving outcomes with adolescents’ (159, R4) which could be achieved as learners now understood adolescents’ ‘…fears, struggles and wishes more’ (550, R4).

Despite most of the responses to this theme being positive, one provided a negative review. This respondent felt that to ‘…constant insist to focus on neurological factors only talks about a reductionist-positivist approach towards understanding what is adolescence..’, which was ‘…boring…’ (443, R4).

4.2.5. Theme 5: Thank-You

The thank-you theme (n = 53, 8%) embedded responses dedicated solely to thanking the course team for developing and delivering the course. Responses such as ‘Thank you so much!’ (114, R4), ‘Thank you, the course is being wonderful and enlightening’ (134, R4), and ‘…thank you for sharing knowledge to everyone!’ (308, R4) exemplify the positive sentiment of this theme.

4.2.6. Theme 6: Student Interaction

The student interaction theme (n = 26, 4%) stood alone from all other themes and centred around the value of online interaction with other learners. Respondents expressed that they enjoyed ‘…reading other opinions and ideas’ (11, R1) and that they had great ‘…conversations with like-minded people all eager to learn’ (55, R3). The online forum was described as a ‘…community…’ (119, R4) embedding ‘…interesting comments from people around the world dealing with the same issues and questions’ (140, R4) from people who are ‘…knowledgeable and culturally broad…’ (245, R4). The online interaction was reported to be ‘…encouraging…’ (332, R4), ‘…helpful…’ (605, R6), and a stimulus for ‘…reflection…’ (255, R4).

4.3. Post-Course Survey: Quantitative Data

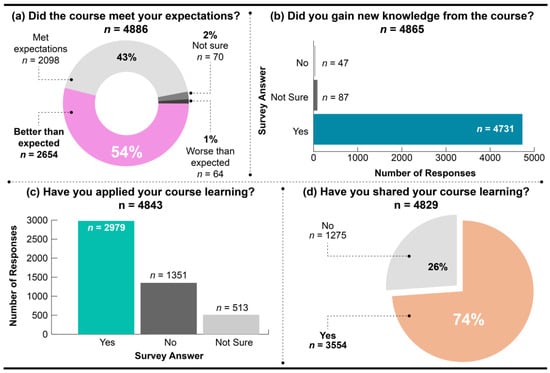

Following the completion of a FutureLearn course, learners are sent an optional post-course survey consisting of multiple-choice (quantitative feedback) and a free-text response (qualitative feedback) questions [29]. To address the quantitative responses, the multiple-choice questions indicated that most (97%) respondents found the course to be better than expected or that it met their expectations (see Figure 9a). The majority (97%) also reported that they gained new knowledge from the course (see Figure 9b), 62% had already applied knowledge from their course at the time of the survey (see Figure 9c), and 74% had shared learning from their course with others (see Figure 9d). The qualitative feedback will now be discussed.

Figure 9.

Post-course survey question responses. (a) Results from the survey question ‘Did the course meet your expectations?’; (b) results from the survey question ‘Did you gain new knowledge from the course?’; (c) results from the survey question ‘Have you applied your course learning?’; (d) results from the survey question ‘Have you shared your course learning?’.

4.4. Post-Course Survey: Student Feedback

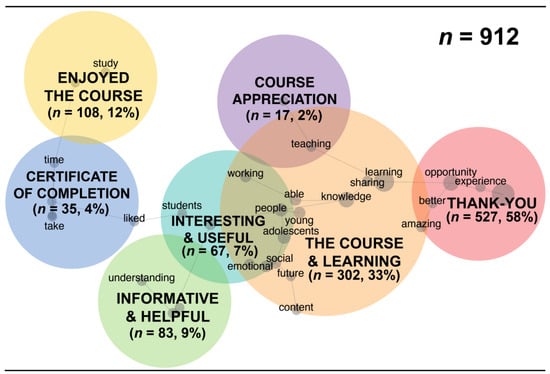

The second optional free-text response question asked in the post-course survey was, ‘Is there anything else you would like to tell us?’ [30]. This question collected n = 912 responses over the seven course runs, which were analysed using Leximancer (see Figure 10).

Figure 10.

Leximancer analysis of participants’ free-text responses to ‘Is there anything else you would like to tell us?’.

4.4.1. Theme 1: Thank-You

The dominant response provided by respondents was to thank the course administrators for running the course (n = 527, 58%) and sharing their ‘… information and knowledge’ (360, R4) while ‘…providing the opportunity to learn about adolescence’ (454, R4) and the ‘…chance to grow’ (747, R4). Responses such as ‘[T]HANKYOU! It was a treat to have this opportunity’ (6, R1) were prevalent, and respondents were also thankful for the ‘…wonderful opportunity to learn about adolescents’ (271, R4), ‘…knowledge you imparted to us’ (113, R4), the ‘…opportunity to learn’ (44, R2), for being able to clarify things that ‘…I am not sure of’ (45, R2), and for it being an ‘…amazing experience’ (103, R4).

Other respondents reported their thanks as the course was useful for them as a ‘… parent and for my work’ (150 R4), ‘… coach’ (343, R4), ‘…Cover Supervisor’ (420, R4), ‘…guidance counselor’ (612, R4), and a ‘…teacher in the Senior High School’ (433, R4). Multiple thank-you messages were recorded from teachers who thanked the course for ‘… making us better teachers’ (23, R1) as it was good for ‘…teacher development and not expensive’ (155, R4). The course administrators were also thanked for ‘…allowing me to really consider my teaching methods and classroom strategies going forward’ (251, R4) as the course ‘…has had a positive impact on the way I approach my teaching’ (279, R4).

The COVID-19 phase recorded some unique perspectives on the thank-you theme, as many were thankful to be studying ‘…especially in this time of “Covid19”’ (407, R4) as the course ‘…really helped me during the covid 19 lockdown’ (501, R4). Some responses indicated that the course ‘…helped me cope with my anxiety during this quarantine! I got to… understand well why I feel this way so suddenly. This course has been a remedy…’ (295, R4), and others reported that ‘…this course it has been a great distraction from the reality of the outside world and has given me good skills to take back to the workplace when it gets back to some form of normal’ (332, R4). Some respondents mentioned that when out of ‘…lock down… I am looking forward to trying to create a PYD framework for my classroom when I go back to work’ (400, R4).

The course administrators were also thanked for a ‘…well compiled…’ (617, R4) and ‘well-curated course’ (735, R4) embedding ‘…great course material’ (542, R4), ‘…academic resources and references’ (674, R4), and ‘…extra materials’ (51, R2). Another was thankful for the course being ‘…short and without empty information; right to the point’ (546, R4). Many were thankful for making ‘…these courses available online’ (587, R4) and that it was a ‘…free course’ (612, R4).

4.4.2. Theme 2: The Course and Learning

Over one-third of respondents (n = 302, 33%) gave feedback on the course and learning, forming a rich source of information for course assessment. Overall, the most common sentiment expressed was positive, evident through respondent comments including, the ‘…course content was very good…’ (73, R3), the course was ‘…fascinating…’ (826, R6), ‘…brilliant…’ (699, R4), ‘…fantastic…’ (379, R4), ‘…insightful and engaging…’ (5, R1), ‘‘…exceeded my expectations…’ (493, R4), and ‘…i had a great time learning…’ (559, R4).

The course content was also positively described as being ‘…easy to understand…’ (559, R4), full of ‘…knowledge and expertise…’ (64, R2), ‘…well-explained’ (557, R4), ‘…clear’ (640, R4), and ‘…diverse…’(493, R4), which allowed an ‘…in-depth understanding of the subject (871, R7). The lessons were commonly described as ‘…comprehensive…’ (559, R4) embedding ‘…quality…’ (224, R4), ‘…relevant, up to date and well summarised information’ (699, R4) in a logical ‘…sequence…’ (901, 7), which ‘…fostered easy understanding’ (906, R7). Respondents particularly commented on the quality course content regarding ‘…the adolescent stage and how important it is to help them develop not only academically, but also socially and emotionally’ (644, R4), ‘…the explanation of the brain development during Adolescence and the PYD frameworks’ (825, R6), ‘…scientific insights for advocating the different needs of youths in order to facilitate their overall better learning engagement, well-being, and a brighter future for them…’ (871, R7), and ‘…neuroscience’ (752, R4).

The course content was described to be an ‘…excellent starting point…’ (224, R4) to stimulate further exploration of the topic as there was ‘…lots of information to go away with and digest’ (379, R4); however, a minority of respondents were ‘…expecting a more in-depth course…’ (96, R3) as ‘…those that have worked in the field… would benefit from greater depth’ (16, R1) as ‘… most teachers are aware of most of these developmental processes’ (239, R4) and therefore, this course ‘…is mainly for beginners…’ (302, R4). Some conflicting reports were also observed. Some of the participants found the terminology ‘…academic…’(244, R4), ‘…too science-heavy…’ (564, R4), and ‘…too complex…’ (261, R4).

Other reports indicated that the content did not consider ‘…that adolescents… develop differently according to the childhood they’ve had’ (4, R1), ‘…the socio-cultural impact that is involved in adolescent development…’ (33, R2) ‘…challenging/disengaged students’ (785, R5), nor ‘…any genders beyond male and female in the course, no mention of trans, non-binary and gender-fluid who are people who exist too…’ (34, R2). There were also challenges to the course title, indicating that it was not representative of the course goal of supporting adolescents; rather, it ‘…almost entirely focuses on the biological changes during adolescence…’ (564, R4).

Suggestions were made to make the course content ‘…more realistic…’ (659, R4) regarding ‘…how to help and support adolescents…’ (429, R4) through ‘…practical advice’ (99, R3). Suggestions to achieve this included discussing a ‘…case study…’ (118, R4), course content ‘…practical application…’ (800, R5) through ‘… activities and techniques…’ (82, R3), and the ‘…Do s and Don’ts while putting the PYD framework to use…’ (602, R4), which applies the course learning. Although suggestions were made for course content updates, most students were content with the course structure.

Some students reported feeling grateful for the ‘…online study’ (184, R4) being ‘…very accessible…’ (95, R3) and ‘…free’ (277, R4), while enabling them to be ‘flexible…’ (237, R4) and to ‘…learn in a focused way without pressure or distractions and at a doable pace’ (536, R4). It was often reported that the ‘…course was very well presented and prompted a lot of thought and discussion…’ (760, R5), ‘…clear and easy to follow…’ (877, R7), ‘…well planned and spaced out’ (624, R4), ‘…well-organized…’ (831, R6), and ‘…well-structured and informative…’ (304, R4). It was also reported that the ‘…pace is good and the content relevant…’ (842, R6) alongside having a great ‘…format…’ (326, R4) and ‘…layout…’ (338, R4) embedding ‘…videos, bullet point information, graphics… and quizzes’ (908, R7), with many liking the ‘…mix of materials and activities…’ (831, R6), which kept the course ‘…interesting and ensured I had the knowledge I needed before moving on’ (338, R4).

The course was described as being ‘…resourceful, have been using all the resources/downloads found them very useful!’ (64, R2), with some students liking ‘…all the external links’ (95, R3), ‘…academic resources and references.’ (674, R4), and ‘…extra materials…’ (51, R2). Conversely, some students reported that they would have liked ‘…more reading material to explore aspects further’ (375, R4), ‘…further pointers to articles I could download, and more resources offered…’ (57, R2), or ‘…some downloadable resources to keep and refer back to from such an information rich course’ (410, R4).

Although some respondents reported that they enjoyed the course pace, two respondents found the course was more time-consuming than expected. One stated that it took ‘…more than 6 h of study. Approx. in between 8 and 10 h of study…’ to complete, as they ‘wanted to do a good job in the comments…’ (750, R4). Another stated that their extended time requirement was needed as they ‘…needed more time allowed to do all the activities’ (396, R4) with another stating that the ‘…tasks were too big and would likely eliminate many people…’ (29, R2). Conversely, others would have liked to spend more time on the course as they thought it would be ‘…great if there is an assignment for students to do’ (520, R4).

Multiple respondents reported that ‘…the audiovisual content’ (629, R4) supported their learning as the ‘…videos…were very informative’ (768, R5) and ‘… assisted in the training of the course’ (263, R4) to help students ‘…grasp thoroughly the ideas they are imparting to you’ (603, R4). Some respondents commented that they would prefer ‘… more videos and less articles’ (77, R3), and others would have liked to view more videos regarding ‘…the PYD frameworks’ (902, R7). Comments were made that some of the videos took ‘…a while to get to the point and may be a little repetitive’ (40, R2), and suggested it would have been good to ‘…to hear from a wider sample of students on the same questions, to compare responses within gender, as well as between gender, and also to hear from different teachers to compare teaching methods’ (488, R4).

It was noted that from a layout perspective, the ‘…page often starts with a video and only having watched it have I scrolled down to read “before watching the video…”…’ (579, R4); therefore, it was recommended that the videos be placed ‘… below what they want us to do, because at the moment we tend to watch the videos first then we discover what we have to do’ (333, R4). Provision of the video ‘…transcripts…’ (457, R4) ‘…helped a lot’ (325, R4) to support students ‘…understand what was being said’ (653, R4). A suggestion was made to include an ‘…Audio version…’ (325, R4) of the video transcripts to enhance vision-impaired student inclusivity. The provision of written transcripts was also viewed as inclusive, as one respondent commented that they are ‘…hard of hearing and the transcripts are my preferred way to access the information’ (886, R7).

Respondents also provided feedback on the tasks they were asked to complete throughout the course. The tasks were often reported as ‘…relevant and useful’ (9, R1) with a ‘…great balance of academic learning and opportunity to reflect on practice’ (52, R2) encouraged by ‘…TO DO tasks to support the learning’ (658, R4). However, one respondent reported that they ‘…suggest not doing tasks at every step, as it becomes very tedious to go one by one. I would prefer the tasks to be longer but only 1 or 2 times per topic’ (745, R4). Another suggestion was, ‘…match up or fill in the blanks activities would have been better than sharing answers or opinions in the comments sections’ (232, R4).

In contrast, many respondents reported ‘…enjoying…’ (569, R4) the interactive nature of the commenting tasks as they ‘…loved the interesting facts and interacting from people around the world’ (619, R4), finding them ‘…insightful as to how different cultures and education systems work’ (488, R4). One respondent suggested that ‘…greater engagement of educators with students in the comments section would make the course even better’ with another suggesting that a ‘…live interaction session would help for some q and a’ (698, R4). The quizzes also received positive feedback, as students felt they made them ‘…think and reflect on learning’ (661, R4) to support content ‘…consolidation…’ (667, R4).

4.4.3. Theme 3: Enjoyed the Course

Multiple reports of respondents enjoying the course (n = 108, 12%) were recorded through comments such as ‘…I have thoroughly enjoyed this course…’ (400, R4). The reasons reported for enjoying the course included that it gave ‘…a lot of insight into a field that I am very interested in…’ (422, R4), and that it was ‘…a fantastic course…’ (311, R4), ‘…impressive…’ (143, R4), ‘…enlightening…’ (90, R3), an ‘…eye opener…’ (263, R4), ‘…inspirational…’ (286, R4), and ‘…thought-provoking…’ (258, R4). It was also noted that enjoyment was enhanced by the ‘…efforts…’ (136, R4) applied by course administrators to make the course ‘…well structured… The way it is presented is very stimulating and understandable…’ (51, R2).

Respondents also reported enjoying ‘…the neuroscience side…’ (241, R4) of the course, that the course tested their ‘…understanding through a quiz, either throughout or at the end’ (608, R4), and ‘… every activity…’, as each left ‘…an impact on me as a teacher in the Senior High School…’ (433, R4). Others enjoyed that they could apply the course ‘…at work…’ (413, R4) as they feel that ‘…it has benefitted…’ (536, R4) them professionally. Due to this, one respondent stated that they ‘wish it is made an obligatory course for the high school teachers. It would be a win win situation!’ (545, R4).

4.4.4. Theme 4: Informative and Helpful

The course was reported to be ‘…very informative…’ (234, R4) and ‘…really helpful…’ (103, R4) by many respondents (n = 83, 9%). These respondents noted that the course was ‘…challenging…’ (1, R1) and embedded ‘…a huge amount of information…’ (66, R2) that was ‘…well organized… which has really helped with the understanding of how the social and well being of an adolescent varies from male to female’ (217, R4). In addition, it was explained that the course increased the participants’ ‘…understanding about the Adolescent period and ways to deal with it more effectively…’ (662, R4), which was ‘…helpful for the teenagers’ (191, R4) and ‘…teachers’ (101, R4).

The course was also commended, as it ‘…refreshed my knowledge and skills but really enhanced them…’ (760, R5), and it was ‘…information rich…’ (410, R4) and ‘…very enlightening’ (187, R4) with ‘…valuable…’ (83, R3) and ‘…informative discussions…’ (683, R4). The course information provided ‘…numerous possibilities in terms of teaching and situation handling’ (431, R4), and ‘…it covered some difficult areas in an easy to understand format’ (322, R4). This enabled participants to gain ‘…many insights’ (777, R5) into ‘…understanding and helping young people better’ (163, R4). One respondent expressed that ‘I feel as if a curtain has been opened in front of my eyes. I actually think I can begin to help my children…’ (229, R4), with another agreeing stating that this informative and helpful course gave them ‘…more confidence in what I do…’ (581, R4).

4.4.5. Theme 5: Interesting and Useful

Many respondents (n = 67, 7%) reported that they found the course to be ‘…very interesting…’ (1, R1) and ‘…useful…’ (10, R1). From the interest viewpoint, the specific aspects mentioned included ‘…timely content…’ (394, R4), the included ‘…studies and research…’ (282, R4), the presentation of the course ‘…in a variety of ways…’ (279, R4), and the focus on ‘…adolescents…’ (583, R4). One respondent reported that they were ‘…amazed how much information I have retained but I think that’s a reflection on how interesting I found the subject…’ (490, R4), and another found it interesting to hear about the course administrators’ ‘…experiences applied to young people…’ (60, R2).

Respondents also reported the course to be useful to ‘…further support the young people I work with…’ (73, R3) and ‘…when we come back to school…’ (678, R4) after COVID-19 lockdowns. It was also reported to be useful for every ‘…parent…’ (150, R4), ‘…mother…’ (543, R4), and ‘…teachers, to contribute to a better society…’ (48, R2). Some respondents also mentioned the provided ‘…resources…’ (404, R4) to be useful, including the ‘…insight from both the course lecturers and students…’ (490, R4), and the embedded ‘…tasks…’ (9, R1), ‘…information…’ (3, R1), and ‘…all the resources/downloads…’ (64, R2).

4.4.6. Theme 6: Certificate of Completion

The requirement of course participants to pay for a certificate of completion was a point of contention for 4% of respondents (n = 35). Within these responses, the general consensus was that it was a ‘…shame you do the whole course then are told to pay £42 if you want a certificate…’ (12, R1), leaving some respondents ‘…disappointed’ (776, R5) and ‘…annoyed…’ (836, R6). Respondents noted that they were not aware of these fees ‘…before the course’ (841, R6), leading them to question what the point of completing the course is if ‘…you are not giving any credibility for our achievement, learning efforts and time?’ (114, R4).

It was also reported that ‘…it is a pity money can interfere…’ (4, 276) in study, as ‘…£42 is too high a price to pay for a certificate’ (69, R2) as it is not ‘…value for money…’ (36, R2), and that not everyone ‘…is in a position to…’ pay to get a certificate (39, R2). Another stated that they ‘…would be happy to pay for the CPD if the prices were lower…’ (281, R4). The arguments for receiving a certificate included how people like a ‘…certificate to prove what I have studied…’ (68, R2) as it would provide the confidence ‘…to prove the knowledge I have on youth’ (349, R4) and ‘…be a positive note adding to my list of improving all the time within my work…’ (38, R2). Others stated that certification ‘… increases motivation…’ (548, R4), as due to the COVID-19 ‘…lockdown not many people got income now and future’ (299, R4).

4.4.7. Theme 7: Course Appreciation

A small number of respondents reported their appreciation for the course (n = 17, 2%) due to the administrators’ ‘…efforts…’ (136, R4) in making‘…teaching free’ (334, R4) when it would have ‘…taken time to put this resource together’ (912, R7). Others were grateful for ‘…this opportunity to learn’ (737, R4) and ‘…the information learned in this course’ (745, R4), alongside the opportunity ‘…to study with the Australian University, it was a privilege and really will be credit’ (266, R4).

4.5. MOOC eLearning Effectiveness

To assess the effectiveness of the MOOC as a professional learning tool, the MOOC assessment framework developed by Gamage et al. (2015) [26] was adapted to act as a self-reflective analytical tool by the researchers and course designers. The ten-dimensional framework embeds 41 items which were rated on a five-point Likert scale (5—strongly agree, 4—agree, 3—neutral, 2—disagree, 1—strongly disagree) to determine the overall MOOC rating. These elements were identified as core design features for effective professional learning, based on previous research in the field. The qualitative and quantitative data from the course leavers, weekly sentiment, and post-course surveys (previously presented) were used to inform the rankings selected in this analysis. Table 1 details the self-reflective analysis to determine the course ratings for each of the 41 items within the ten dimensions.

Table 1.

Self-reflective analysis of the MOOC based on Gamage et al. (2015) [26].

5. Discussion

This research set out to examine insights from the delivery and potential impact of a Massive Online Open Course (MOOC) on the topic, Supporting Adolescent Learners: Social and Emotional Well-being. Insights from the seven course iterations with 32,969 total enrolments and 22,324 actual participants provided a rich data set for the study. Data were sourced from what was readily available and a self-reflection tool was applied (see Figure 6). The following research questions guided the investigation:

- What is the nature of the participants and their level of engagement in the MOOC?

- What is the reported experience of the participants?

- How effective was the MOOC as a professional learning tool?

5.1. RQ1 the Nature of Participants and Their Level of Engagement

The data informing this question were derived from the analysis of the demographic data and the course engagement data. Findings are limited to the quarter of participants who voluntarily responded to the demographic questionnaire; hence, this provided a smaller-than-hoped-for snapshot of the nature of the participants engaged in the MOOC.

The greatest proportion of the survey respondents were female (65%), with just under half (47%) aged 45 years or less, and 28% were employed full-time. Nearly half (44%) held a bachelor’s degree as their highest level of qualification, and 48% were employed within the teaching and education sector. The MOOC had an extensive international geolocational reach. Through their IP addresses, it was determined that the majority of active learners were from Europe (48%) and Asia (27%), with the top three countries being the United Kingdom (n = 6666), India (n = 1685), and Australia (n = 1173). Active learners were identified to originate from 178 countries.

In terms of their level of engagement, FutureLearn provides comprehensive details on the level of engagement with the course. This course has what is regarded to be a high course retention index, with 51% of learners completing 51% of the course and 8383 completing 90% or more of the course.

This information reveals a global interest in better understanding the social and emotional well-being of young adolescents. It also points to the need for professional learning that meets the needs of a range of users, but is interestingly dominated by teachers and educators, who might be regarded as already holding expertise on this topic. This finding is not surprising, as access to high-quality, accessible professional learning in this space continues to be in short supply [22].

5.2. RQ2 the Reported Experience of the Participants

The data informing this question were derived from the course leavers survey, the weekly sentiment survey, and the post-course survey. The course leavers survey focused entirely on those participants who left the course without completing it. Most students left the course due to their course access expiring (23%), not having enough time (22%), or other reasons unspecified (21%). Less than 1% left because the course was too hard or too easy, and 3% indicated that it would not help them achieve their goals. The course lasted 6 h in total, delivered over two weeks, with the course remaining open and accessible for six weeks. Almost half of the leavers did so because they ran out of time. The motivation to complete the course in the time provided may have been negatively impacted by the nature of the course being free to participants.

The weekly sentiment survey asked participants to rate their course experience twice across the MOOC course, with 93% indicating they were happy, 6% neutral and just 1% unhappy. The comments that accompanied the ratings were analysed with the themes emerging as follows: informative and interesting, course design, course enjoyment, understanding adolescence, thank-you, and student interaction. The comments were dominated by positive feedback about the content and personal learning that participants were experiencing. This feedback aligns with the principles of andragogy, which point to the importance of relevance and experience [19] as key elements of effective learning design for adults.

The post-course evaluation was an optional survey, with more than 900 participants providing comments. The qualitative thematic analysis of these data revealed seven themes, all but one strongly positive, these being the following: thank-you, the course and learning, enjoyment, informative and helpful, interesting and useful, course appreciation. Again, these themes align with the principles of andragogy as an effective learning design for adults, noting the course and learning activities, relevance and active engagement through fun, and meeting the needs of these adult learners. The negative comments were aligned to the theme, certificate of completion, which revealed that some participants were disappointed that they had to pay a fixed (small) amount in order to receive a certificate of completion from FutureLearn. Comments across the remaining themes highlighted the relevance and usefulness of the learning, pointing to the effectiveness of the MOOC.

5.3. RQ3 Effectiveness as a Professional Learning Tool

To assess the effectiveness of the MOOC as a professional learning tool according to core features in the design, the MOOC assessment framework developed by Gamage et al. (2015) [26] was adapted to act as a self-reflective analytical tool and assessed by the researchers and course designers. The 41 items were rated on a five-point Likert scale (5—strongly agree, 4—agree, 3—neutral, 2—disagree, 1—strongly disagree) to determine the overall MOOC rating. The detailed analysis is presented in Table 1 and the dimensions and rating allocated are presented here in Table 2.

Table 2.

Total score of the MOOC.

This scoring results in 178 points out of a possible 205 for the 41 items across the 10 categories. The dimensions where the scoring was lowest were collaboration, interactivity and, to a lesser extent, pedagogy. This is interesting in relation to adult learning, where collaboration and the ability to interact and be active learners feature as effective elements of andragogy [19]. Also noteworthy is the assumption in Gamage et al.’s model that pedagogy is a MOOC dimension, which positions the tool as having school-aged learners as the target audience rather than adult learners. Nevertheless, the framework developed by Gamage et al. (2015) [26] has been a useful tool to reflect on the MOOC for the core features likely to lead to effective professional learning. The areas of lowest performance can be explained by the design of the course itself, which was intended to be self-paced and without synchronous interaction with the facilitators, hence reflecting intentional decisions in this regard. This design aligns with the principles of andragogy, where self-direction and motivation are key features of adult learners. Because the scoring on this scale is high, the extrapolation is that the MOOC is likely to provide effective professional learning for participants [26].

5.4. Limitations

An important limitation of this study is the low response rates for the demographic, weekly sentiment, and post-course surveys. Just 25% of course learners responded to the demographic questions, and 4% of active learners responded to the weekly sentiment survey. Regarding the post-course survey, 58% of learners with 90% step completion completed the quantitative component and 11% the qualitative component. With this variable and a low response rate overall, the results are prone to non-response bias when applied to the entire student cohort. Therefore, the results shared in this paper are not a representative sample of the cohort who engaged in the course. Nevertheless, these insights provide a lens into the characteristics of the participants, their levels of engagement, and commentary about their engagement in the course.

6. Conclusions

The phenomenon of MOOCs is likely to continue to grow given the global ease of access without special hardware or software, especially when courses are offered free to participants. Hence, the effectiveness of participating in the courses is an important consideration to optimise engagement and value. The MOOC under examination here, Supporting Adolescent Learners—Social and Emotional Well-being, was designed as a free, self-paced, asynchronous experience and was a popular course, especially for teachers and educators. This study included all participants engaged in seven course iterations with 32,969 total enrolments and 22,324 actual participants. The MOOC had clear objectives with four topics addressing aspects of adolescent development and social and emotional well-being. Course participation data are thorough, including details of completion rates covering all aspects of the course, enabling a deep understanding of the participants’ engagement. However, information about course participants, such as demographic information, reveals gaps, as this is an optional aspect for completion by participants. The use of the tool, in this case Gamage et al.’s (2015) [26] reflective tool, has added an important dimension to understanding the effectiveness of the MOOC as it enables the consideration of the core design features that researchers have established as important for the effective delivery of MOOCS. However, as noted at the outset of this paper, the tool relies on these core design features as a proxy for determining the effectiveness of the MOOC in leading to outcomes and sustained impact. Nevertheless, we recommend the further development and validation of this instrument as it is specifically contextualised for MOOCs. Ultimately, incorporating measures of self-efficacy at the outset and matching these to measures upon the completion and post-completion of the MOOC has the potential to determine the long-term effectiveness of the MOOC. Currently, these data are not available.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, D.P. and K.M.; methodology, D.P., K.M. and S.M.; validation, D.P., K.M. and S.M.; formal analysis, D.P. and S.M.; investigation, D.P., K.M. and S.M.; resources, D.P. and K.M.; data curation, D.P. and S.M.; writing—original draft preparation, D.P., K.M. and S.M.; writing—review and editing, D.P., K.M. and S.M.; visualisation, S.M.; project administration, D.P., K.M. and S.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

According to the National Statement on Ethical Conduct in Human Research (2023), research may be ethics exempt if it involves the use of existing collections of data or records that contain only non-identifiable information and if their research has negligible risk, as is the case in this study (See Section 5.1.17). FutureLearn administer a standard pre-course and a post-course survey for each course run on the platform. Course information was provided via the FutureLearn platform. The data utilized in this study is provided by FutureLearn and is anonymised before being released to partner institutions.

Informed Consent Statement

Demographic data is collected via an optional survey at the time of registration and consent is obtained through voluntary participation.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Powell, R.B.; Stern, M.J.; Frensley, B.T.; Moore, D. Identifying and developing crosscutting environmental education outcomes for adolescents in the twenty-first century (EE21). Environ. Educ. Res. 2019, 25, 1281–1299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization: Promoting Well-Being. Available online: https://www.who.int/activities/promoting-well-being (accessed on 11 June 2024).

- Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development. Social and Emotional Skills: Well-Being, Connectedness and Success; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Yeager, D.S. Social and emotional learning programs for adolescents. Future Child. 2017, 27, 73–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steponavičius, M.; Gress-Wright, C.; Linzarini, A. Social and emotional skills: Latest evidence on teachability and impact on life outcomes. OECD Educ. Work. Pap. 2023, 304, 1–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durlak, J.A.; Mahoney, J.L.; Boyle, A.E. What we know, and what we need to find out about universal, school-based social and emotional learning programs for children and adolescents: A review of meta-analyses and directions for future research. Psychol. Bull. 2022, 148, 765–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinberg, L. Adolescence, 13th ed.; McGraw Hill: New York, NY, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Blakemore, S.J.; Mills, K.L. Is adolescence a sensitive period for sociocultural processing? Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2014, 65, 187–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choudhury, S.; Piera Pi-Sunyer, B.; Blakemore, S.-J. A neuroecosocial perspective on adolescent development. Annu. Rev. Dev. Psychol. 2023, 5, 285–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dienlin, T.; Johannes, N. The impact of digital technology use on adolescent well-being. Dialogues Clin. Neurosci. 2020, 22, 135–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Small, G.W.; Lee, J.; Kaufman, A.; Jalil, J.; Siddarth, P.; Gaddipati, H.; Moody, T.D.; Bookheimer, S.Y. Brain health consequences of digital technology use. Dialogues Clin. Neurosci. 2020, 22, 179–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greenfield, P.M. Social change, cultural evolution, and human development. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2016, 8, 84–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Korte, M. The impact of the digital revolution on human brain and behavior: Where do we stand? Dialogues Clin. Neurosci. 2020, 22, 101–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ibrahim, A.; El Zaatari, W. The teacher–student relationship and adolescents’ sense of school belonging. Int. J. Adolesc. Youth 2020, 25, 382–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, H.; Chang, Y. Relational support from teachers and peers matters: Links with different profiles of relational support and academic engagement. J. Sch. Psychol. 2022, 92, 209–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wentzel, K.R. Teacher-student relationships and adolescent competence at school. In Interpersonal Relationships in Education; Wubbles, T., den Brok, P., van Tartwijk, J., Levy, J., Eds.; Sense Publishers: Rotterdam, The Netherlands, 2012; pp. 19–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedder, D.; Opfer, V.D. School orientation to teacher learning and the cultivation of ecologies for innovation: A national study of teachers in England. In Innovations in Educational Change: Cultivating Ecologies for Schools; Education Innovation Series; Springer: Singapore, 2019; pp. 147–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asterhan, C.S.C.; Lefstein, A. The search for evidence-based features of effective teacher professional development: A critical analysis of the literature. Prof. Dev. Educ. 2023, 50, 11–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knowles, M.S. The Adult Learner: A Neglected Species; Gulf Publishing Company: Houston, TX, USA, 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Kolb, D.A. Experiential Learning: Experience as the Source of Learning and Development; Prentice Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Desimone, L. Rethinking Teacher PD: A Focus on How to Improve Student Learning. Prof. Dev. Educ. 2023, 49, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Main, K.; Pendergast, D. Continuing professional development and middle years teachers: What the literature tells us. In International Handbook of Middle Level Education Theory, Research, and Policy; Virtue, D., Ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 220–236. [Google Scholar]

- Spector, J.M. Instructional design methods and practice: Issues involving ICT in a global context. In ICT in Education in Global Context: Comparative Reports of Innovations in K-12 Education; Lecture Notes in Educational Technology; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2016; pp. 59–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Report: By the Numbers: MOOCs in 2020. Available online: https://www.classcentral.com/report/mooc-stats-2020/ (accessed on 11 June 2024).

- Kennedy, E.; Laurillard, D. The potential of MOOCs for large-scale teacher professional development in contexts of mass displacement. Lond. Rev. Educ. 2019, 17, 141–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamage, D.; Fernando, S.; Perera, I. Factors leading to an effective MOOC from participants perspective. In Proceedings of the 2015 8th International Conference on Ubi-Media Computing (UMEDIA), Colombo, Sri Lanka, 24–26 August 2015; pp. 230–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FutureLearn’s 2020: Year in Review. Available online: https://www.classcentral.com/report/futurelearn-2020-year-review/ (accessed on 11 June 2024).

- Supporting Adolescent Learners: Social and Emotional Well-Being. Available online: https://www.futurelearn.com/courses/supporting-adolescent-learners (accessed on 11 June 2024).

- FutureLearn: What Is the Stats Dashboard and What Data Does It Collect? Available online: https://partners.futurelearn.com/hc/en-us/articles/7855378633106-What-is-the-Stats-dashboard-and-what-data-does-it-collect- (accessed on 11 June 2024).

- FutureLearn: Ratings, Reviews and Learner Surveys. Available online: https://partners.futurelearn.com/hc/en-us/articles/7855433272978-Ratings-reviews-and-learner-surveys (accessed on 11 June 2024).

- FutureLearn: Know Your Learners. Available online: https://partners.futurelearn.com/hc/en-us/articles/7855452729618-Know-your-learners (accessed on 11 June 2024).

- Pendergast, D.; Main, K. Ready to learn: Supporting and promoting the social and emotional well-being of adolescent learners through a free online learning platform. In Health and Well-Being in the Middle Grades: Research for Effective Middle-Level Education; Main, K., Whatman, S., Eds.; IAP: Charlotte, NC, USA, 2023; pp. 283–302. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, J.W.; Plano-Clark, V.L. Designing and Conducting Mixed Methods Research, 3rd ed.; Sage: Newcastle upon Tyne, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leximancer User Guide Release 4.5. Available online: https://static1.squarespace.com/static/5e26633cfcf7d67bbd350a7f/t/60682893c386f915f4b05e43/1617438916753/Leximancer+User+Guide+4.5.pdf (accessed on 11 June 2024).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).