Beyond the Language: Arabic Language Textbooks in Arab–Palestinian Society as Tools for Developing Social–Emotional Skills

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Social–Emotional Learning

- Self-management: the ability to manage one’s emotions, thoughts, and behaviors effectively in different situations and to achieve goals and aspirations.

- Responsible decision-making: the ability to make caring and constructive choices about personal behavior and social interactions across diverse situations.

- Relationship skills: the ability to establish and maintain healthy and supportive relationships and to effectively navigate settings with diverse individuals and groups.

- Social awareness: the ability to understand the perspectives of and empathize with others, including those from diverse backgrounds, cultures, and contexts (see Appendix A for details of the categories and related sub-skills).

2.2. Social–Emotional Learning in the Context of Arab Society in Israel

2.3. Principles for Absorbing and Cultivating Optimal SEL

- SAFE: a concept relating to four different components for SEL success. Sequenced—learning is based on a gradual “step by step” process;

- Active—learning includes active and practical practice of the skills learned; Focus—learning dedicates specific time to develop specific social–emotional skills;

2.4. Adaptation to the Developmental Stage

2.5. Integration of SEL in Arabic Textbooks

3. This Study and Research Questions

- Are SEL skills reflected in Arabic language education textbooks used in Arab elementary schools in Israel? And what are the dominant skills, according to the five categories of the CASEL model [1], in these textbooks?

- How are the skill categories in the CASEL model [1] reflected in the division into the different age groups?

- To what extent do these textbooks adhere to the principles that support the optimal integration and absorption of SEL concepts?

4. Methodology

4.1. Study Range

4.2. The Research Sample

4.3. The Research Process

4.4. Validation and Reliability

5. Findings

5.1. Social–Emotional Skills in the Textbooks (Grades 1–6)

Perception of Social–Emotional Skills in Textual Content

5.2. Examples of Social–Emotional Skills from the Sample Books

- Interpersonal relationship skills: “I visited my cousin in the hospital and gave her a bunch of flowers” [42] (p. 68); “Ahmed says, I hope to invite my dear friend Fadi, as I will never forget his surprise when he invited me to spend the night of ‘Jesus’ birthday’ with him and his family. During the party, we decorated the Christmas tree” (Grade 2, p. 66); “Sameer and Hossam, my friends, visited my house bearing gifts. I greeted them and expressed my gratitude. Afterwards, we began playing in my room” (Grade 2, p. 30).

- Responsible decision-making: “His father decided to take him and his sister Mariana on a trip. This decision had profound effects on his son’s psychological and musical development” [44] (p. 21); “He decided to leave his job and travel round the country to tell people about his courage and strength” [45] (p. 197).

- Self-awareness: “All of this motivates me to write in all honesty because I want to be better, and because I want you to always be the best in my eyes, as you are today” [42] (p. 153). (“My friends and I eagerly await our weekly computer class, and I have become skilled and proficient in using the Paint program on the computer” (Grade 2, p. 94); “However, people quickly recognized the mistake in their beliefs when they discovered its nutritional value” [41] (p. 12).

- Self-management: “My father asked me: what is the purpose of the school? There are a lot of teachers and lawyers. I told him I want to be a journalist” [46] (p. 142).; “I will draw your picture and hang it above the sink so that I can remember your words and so that all members of my family can see them, so that they do not waste water” [47] (p. 102).; “Since his childhood in Al-Ri, he had a deep affection for science and scientists, which led him to study mathematics, astronomy, chemistry, logic, and literature. However, these disciplines did not quench his thirst for knowledge, as earth sciences were not available in Al-Ri at that time. Consequently, Razi moved to Baghdad, which he regarded as the world’s capital of science during that era” [41] (p. 47).

- Social awareness: “The genie was very happy and thanked Ala’ Aladdin for his generous behavior” [43] (p. 188); “I would gladly give half my life to anyone who can bring a smile to a crying baby’s face” [41] (p. 65); “Among the people, my deepest affection is for the workers; the blacksmith, the tailor, the carpenter—I love them all” [42] (pp. 32,33).

- ‘Nikolai loved his friends and trusted them, and he had no doubt that they had done their utmost to help him answer his questions, yet their answers did not convince him. Suddenly, an idea struck him, and he muttered to himself, “I know what I should do! I will go to wise old Leo, for his long life has given him knowledge and experience that enable him to answer complex questions”’ [41] (p. 149).

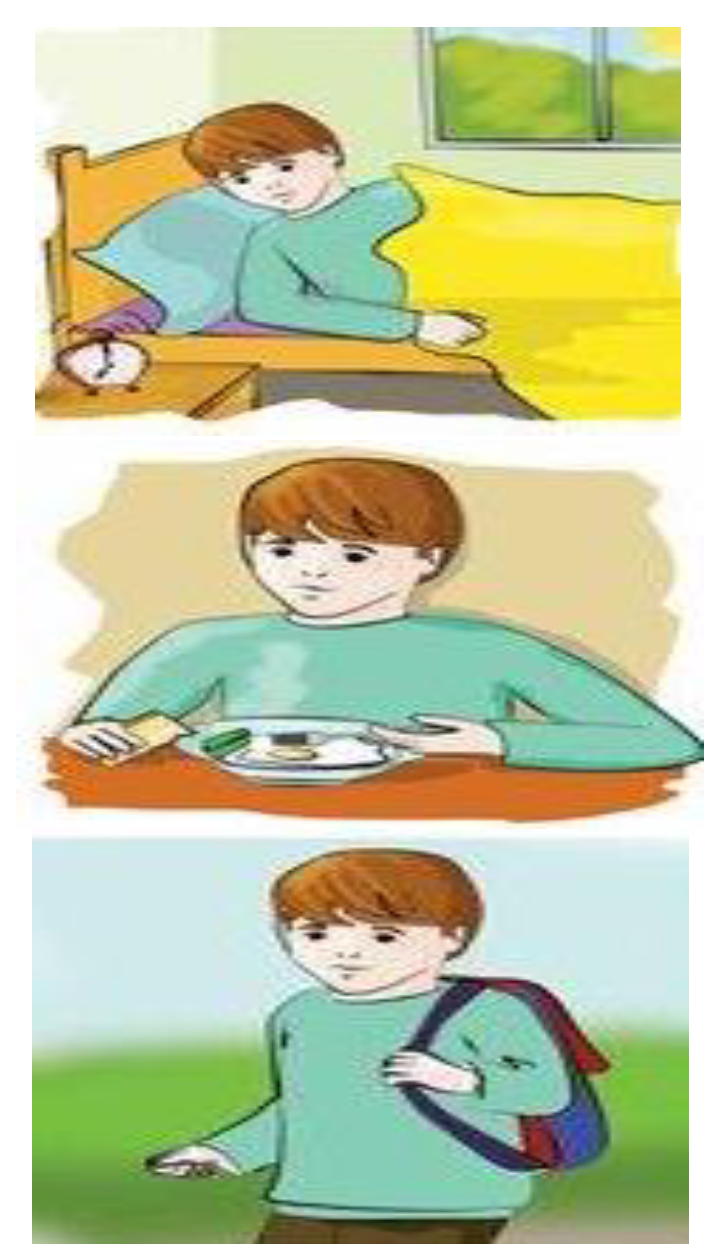

Perception of Social–Emotional Skills in Visual Content—Drawings and Pictures

5.3. Examples of Pictures from the Sample Books of this Study and Their Classification into Categories (Figure 1, Figure 2, Figure 3, Figure 4 and Figure 5)

5.4. Social–Emotional Skills in the Textbooks According to the Different Age Levels

5.5. Principles of Absorbing and Fostering Optimal Social–Emotional Learning

- What do these pictures have in common?

- We are in a school or a certain place that does not provide opportunities for those with special needs, what should we do?

5.6. Examples of Exercises Promoting the Principle of Activeness in Social–Emotional Learning

- Social–emotional activity in the classroom: “Your friend wants to play the piano, but he worries about disturbing people at home. Send him some advice that will help him solve the problem” [45] (p. 107). The exercise promotes the skill of identifying solutions to personal and social problems that belong to the responsible decision-making category; “The social welfare department in your town held a celebration to support people with special needs and integrate them into the community. Write the speech you will deliver during the celebration on behalf of the families of people with special needs” [42] (p. 103). This exercise encourages the development of empathy and community engagement by advocating for a marginalized group.

- Social–emotional activity outside the classroom: “Conduct an interview with one of the grandfathers about his childhood life” (Grade 4, p. 183). The exercise promotes the skill of taking the perspectives of others, which belongs to the social awareness skills; “We ask our mother/grandmother/aunt to teach us how to prepare ‘Eid cookies’ or ‘Manakish’ in the kitchen” [42] (p. 31). This exercise fosters intergenerational bonding and cultural transmission, and enhances the skill of practicing teamwork, which belongs to the relationship skill category.

5.7. Social–Emotional Interaction and Involvement

5.8. Examples of Exercises Promoting Interaction and Social–Emotional Involvement

- Interaction in the class/school: “We will divide up into groups and work on turning the story into a theatrical work that we will present to the students of the school” [48] (p. 238).

- Interaction outside the classroom: “Ask grandfather/grandmother/father/mother/or an elderly relative to tell us about what they did on holidays when they were young” [44] (p. 92).

6. Discussion and Conclusions

6.1. Limitations and Future Research Directions

- Examining the integration of social–emotional learning in language teaching books, Hebrew and English, in both education systems, Arab and Hebrew.

- Examining the integration of social–emotional learning in Arab language teaching books for Arab schools in both middle and high schools.

- Examining the perception of language teachers towards the role of Arabic language teaching books in the context of imparting social–emotional skills alongside linguistic skills.

6.2. Practical Recommendations

- The books will combine diverse social–emotional skills at the textual and visual level.

- The books will be based on an ongoing, conscious, and intentional program that combines the acquisition of these skills alongside linguistic skills, suitable for different ages and balancing the personal and interpersonal domains.

- Adapting the social–emotional skills in the textbooks to the socio-cultural context, with an emphasis on social awareness as a way to improve relations between different groups.

- The books will meet the principles of the optimal assimilation of social–emotional learning, including the focus of the chapters on one specific category or skill, which serves as the thread connecting all the textual and visual elements of the chapter, while demonstrating the skill, and discussing it in a focused and direct manner.

- The books will combine practical and experiential activities that contribute to the development of social–emotional and linguistic skills, while adapting the types of activities to the different age groups.

- The books will include activities that encourage collaboration and social interaction between the students within the classroom, and also with adults outside of it, such as in school, the family, and the community, whilst maintaining a balance between the classroom and extracurricular activities and encouraging broad cooperation between the school and the family.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. List of SEL Categories and Sub-Skills [1]

| Self-Awareness | Self-Management | Responsible Decision-Making | Relationship Skills | Social Awareness |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Understanding one’s own emotions, thoughts, and values and how they influence behavior across contexts | Managing one’s emotions, thoughts, and behaviors effectively in different situations | Making caring and constructive choices about personal behavior and social interactions across diverse situations by considering ethical standards and safety concerns | Developing positive relationships | Understanding the perspectives of and empathize with others, including those from diverse backgrounds, cultures, and contexts |

| Recognizing one’s strengths and limitations | Delay gratification | To evaluate benefits and consequences of various actions for personal, social, and collective well-being | To effectively navigate settings with diverse individuals and groups | Demonstrating empathy and compassion |

| Experiencing self-efficacy | Managing stress | Demonstrating curiosity and open-mindedness | Communicating effectively and listening actively | Identifying diverse social norms, including unjust ones |

| Integrating personal and social identities | Exhibiting self-discipline and self-motivation | Learning how to make a reasoned judgment after analyzing information, data, and facts | Practicing teamwork and collaborative problem-solving | Recognizing family, school, and community resources and supports |

| Identifying personal, cultural, and linguistic assets | Setting individual and collective goals and acting to achieve them | Identifying solutions for personal and social problems | Resolving conflicts constructively | Recognizing strengths in others |

| Demonstrating honesty and integrity | Using planning and organizational skills | Recognizing how critical thinking skills are useful both inside and outside of school | Showing leadership in groups | Understanding and expressing gratitude |

| Examining prejudices and biases | Showing the courage to take initiative | Seeking or offering support and help when needed | Recognizing situational demands and opportunities | |

| Having a growth mindset | Demonstrating personal and collective agency | Resisting negative social pressure | ||

| Developing interests and a sense of purpose | Standing up for the rights of others |

Appendix B. Researched Textbooks

References

- CASEL. CASEL’S SEL FRAMEWORK: What Are the Core Competence Areas and Where Are They Promoted? In 2020. Available online: https://www.akleg.gov/basis/get_documents.asp?session=32&docid=13249 (accessed on 1 March 2023).

- Frye, E.; Boss, L.; Anthony, H.; Xing, W. Content analysis of the CASEL framework using K–12 state SEL standards. Sch. Psychol. Rev. 2022, 53, 208–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melani, B.; Roberts, S.; Taylor, J. Social emotional learning practices in learning English as a second language. J. Engl. Learn. Educ. 2020, 10, 3. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, D.; Oberle, E.; Durlak, A.; Weissberg, P. Promoting positive youth development through school-based social and emotional learning interventions: A meta-analysis of follow-up effects. Child Dev. 2017, 88, 1156–1171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, S.; Kahan, J. The Evidence Base for How We Learn: Supporting Students’ Social, Emotional, and Academic Development. Consensus Statements of Evidence from the Council of Distinguished Scientists; Aspen Institute: Washington, DC, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Benbenishty, R.; Friedman, T. (Eds.) Social and Emotional Skills Cultivation in the Education System: A Summary of the Proceedings of the Expert Committee, Status Report and Recommendations; Yozma: Hebrew, Israel, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Byram, M.; Gribkova, B.; Starkey, H. Developing the Intercultural Dimension in Language Teaching: A Practical Introduction for Teachers; Council of Europe: Strasbourg, France, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Efron, K. Representations of Multiculturalism in Japanese Elementary EFL Textbooks: A Critical Analysis. Intercult. Commun. Educ. 2020, 3, 22–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, M.; Barnes, P.; Bailey, R.; Doolittle, J. Promoting social and emotional competencies in elementary school. Future Child. 2017, 27, 49–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahan, Y. Theories of Social Justice; Ministry of Defense: Hebrew, Israel, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Smooha, S. Israeli society: Like other societies or an exceptional case? Isr. Sociol. 2010, 11, 297–302. [Google Scholar]

- Berkowitz, R.; Astor, R.; Pineda, D.; DePedro, K.; Weiss, E.; Benbenishty, R. Parental involvement and perceptions of school climate in California. Urban Educ. 2021, 56, 393–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Simmons Zuilkowski, S. “I can teach what’s in the book”: Understanding the why and how behind teachers’ implementation of a social-emotional learning (SEL) focused curriculum in rural Malawi. Br. J. Educ. Psychol. 2022, 92, 974–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amara, M. Arabic in Israel: Language, Identity and Conflict; Routledge: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Arar, K.; Ibrahim, F. Education for national identity: Arab schools principals and teachers’ dilemmas and coping strategies. J. Educ. Policy 2016, 31, 681–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cipriano, C.; Strambler, M.J.; Naples, L.H.; Ha, C.; Kirk, M.; Wood, M.; Durlak, J. The state of evidence for social and emotional learning: A contemporary meta-analysis of universal school-based SEL interventions. Child Dev. 2023, 94, 1181–1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durlak, J. Programme implementation in social and emotional learning: Basic issues and research findings. Camb. J. Educ. 2016, 46, 333–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrington, C.; Roderick, M.; Allensworth, E.; Nagaoka, J.; Keyes, T.; Johnson, D.; Beechum, N. Teaching Adolescents to Become Learners: The Role of Noncognitive Factors in Shaping School Performance—A Critical Literature Review; Consortium on Chicago School Research: Chicago, IL, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Friedman, T.; Weisberg-Gold, H. Personalized Social-Emotional Learning; SEL Challenge: Pullman, WA, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Heckman, J.; Stixrud, J.; Urzua, S. The effects of cognitive and noncognitive abilities on labor market outcomes and social behavior. J. Labor Econ. 2006, 24, 411–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garbacz, S.A.; Herman, K.C.; Thompson, A.M.; Reinke, W.M. Family engagement in education and intervention: Implementation and evaluation to maximize family, school, and student outcomes. Journal of school psychology. 2017, 62, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weissberg, R.; Durlak, J.; Domitrovich, C.; Gullotta, T. (Eds.) Social and emotional learning: Past, present, and future. In Handbook of Social and Emotional Learning: Research and Practice; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2015; pp. 3–19. [Google Scholar]

- Kopelman-Robin, K. Developmental aspects in social-emotional learning. In Cultivating Social-Emotional Learning in the Education System; Benbenishty, R., Friedman, T., Eds.; Initiative—Center for Knowledge and Research in Education, Israel National Academy of Sciences: Jerusalem, Israel, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Cefai, C.; Bartolo, A.; Cavioni, V.; Downes, P. Strengthening Social and Emotional Education as a core curricular area across the EU. In A Review of the International Evidence, NESET II Report; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Fisher, D.; Frey, N. The links between social and emotional learning and literacy. J. Adolesc. Adult Lit. 2019, 63, 115–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dresser, R. Integrate social-emotional learning into oral reading practices for best results. Educ. Dig. 2013, 79, 61–66. [Google Scholar]

- Haynes, N.; Ben-avie, M.; Ensign, J. (Eds.) How Social and Emotional Development Add up: Getting Results in Math and Science Education; Teachers College Press: New York, NY, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Gorniak, N. Understanding the Relationship between Adverse Childhood Experiences, Social-Emotional Learning Skills, and Behavioral Difficulties of Youth. Doctoral dissertation, University of Houston-Clear Lake, Houston, TX, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Chapelle, C. Teaching Culture in Introductory Foreign Language Textbooks; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Gottfried, S.; Kyle, W. Textbook use and the biology education desired state. J. Res. Sci. Teach. 1992, 29, 35–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, R.; Tlili, A.; Zhang, X.; Sun, T.; Wang, J.; Sharma, R.C.; Affouneh, S.; Salha, S.; Altinay, F.; Altinay, Z. A Comprehensive Framework for Comparing Textbooks: Insights from the Literature and Experts. Sustainability 2022, 14, 6940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linder, R. Enhancing social awareness development through multicultural literature. Middle Sch. J. 2021, 52, 35–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandell, M. Teaching Social Emotional Skills through Literacy. Master’s Thesis, Hamline University, Saint Paul, MN, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenblatt, M. Literature as Exploration; The Modern Language Association of America: New York, NY, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Boyles, N. Learning character from characters: Linking literacy and social-emotional learning in the elementary grades is easier than you think. Emot. Leadersh. 2018, 7, 70–74. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, A. An Ugly Face in the Mirror—National Stereotypes in Hebrew Children’s Literature; Reshafim: Hebrew, Israel, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Cappiello, M.; Dawes, E. Teaching with Text Sets; Shell Educational Publishing: Huntington Beach, CA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Gonin, R. Between lines and shapes: Components for identifying value messages in the illustration design and text of illustrated books for children. Olam Katan 2000, 1, 41–70. [Google Scholar]

- Bauer, M.; Gaskell, G. Qualitative Researching with Text, Image and Sound: A Practical Handbook; Sage: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Holsti, O.R. Content Analysis for the Social Sciences and Humanities; Addison-Wesley: Reading, MA, USA, 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Center for Educational Technology. ‘Al-Arabiyyah Lu’tuna’ (Arabic Our Language). Grade 5, 2. 2013.

- Center for Educational Technology. ‘Al-Arabiyyahh Lu’tuna’ (Arabic Our Language). Grade 6, 2, 2014.

- Center for Educational Technology. ‘Al-Arabiyyah Lu’tuna’ (Arabic Our Language). Grade 2, 2010.

- Center for Educational Technology. ‘Al-Arabiyyah Lu’tuna’ (Arabic Our Language). Grade 5, 1, 2013.

- Center for Educational Technology. ‘Al-Arabiyyah Lu’tuna’ (Arabic Our Language). Grade 4, 2012.

- Center for Educational Technology. ‘Al-Arabiyyah Lu’tuna’ (Arabic Our Language). Grade 6, 1, 2014.

- Center for Educational Technology. ‘Al-Arabiyyah Lu’tuna’ (Arabic Our Language). Grade 1, 2, 2011.

- Center for Educational Technology. ‘Al-Arabiyyah Lu’tuna’ (Arabic Our Language). Grade 3, 2011.

- Ministry of Education. Learning program: Arabic linguistic education: Language, literature, and culture for elementary school (Grades 1-6), Arabic, Jerusalem: Ministry of Education. 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Adams, R.; Richie, C. Social emotional learning and English language learners: A review of the literature. Intesol J. 2017, 14, 77-93–93. [Google Scholar]

- Kress, F.; Norris, A.; Schoenholz, A.; Elias, J.; Siegle, P. Bringing Together Educational Standards and Social and Emotional Learning: Making the Case for Educators. Am. J. Educ. 2004, 111, 68–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shikhmanter, R. New approaches to children’s literature; The Open University of Israel: Ra’anana, Israel, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Nasser, H. A Letter to Teachers and Parents: Dealing with Violence among Children and Teenagers in Arab Society; Pardes Publishing House: Haifa, Israel, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Hofstede, G.; McCrae, R. Personality and Culture Revisited: Link in Traits and Dimensions of Culture. Cross-Cult. Res. 2004, 38, 52–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haj Yahya, A. Inclusion, Equality and Educational Justice: Enhancing Social-Emotional Learning through Children’s Literature in a Diverse and Segregated Society. Diversity, & Inclusion. 2024, 8, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jomaa, H.; Duquette, C.; Whitley, J. Elementary Teachers’ Perceptions and Experiences Regarding Social-Emotional Learning in Ontario. Brock Educ. J. 2023, 32, 9–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doyle, B.; Bramwell, W. Promoting emergent literacy and social-emotional learning through dialogic reading. Read. Teach. 2006, 59, 554–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCormick, M.P.; Cappella, E.; O’Connor, E.; Hill, J.L.; McClowry, S. Do effects of social-emotional learning programs vary by level of parent participation? Evidence from the randomized trial of INSIGHTS. J. Res. Educ. Eff. 2016, 9, 364–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| No. | Categories of Social–Emotional Skills | Incidence | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Interpersonal relationship skills | 449 | 29.25 |

| 2. | Responsible decision-making | 323 | 21.04 |

| 3. | Self-awareness | 302 | 19.67 |

| 4. | Self-management | 258 | 16.80 |

| 5. | Social awareness | 203 | 13.32 |

| Total | 1535 | 100 |

| No. | Categories of Social–Emotional Skills | Incidence | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Interpersonal relationship skills | 121 | 65.05 |

| 2. | Self-management | 19 | 10.21 |

| 3. | Self-awareness | 17 | 9.13 |

| 4. | Social awareness | 15 | 8.06 |

| 5. | Responsible decision-making | 14 | 7.52 |

| Total | 186 | 100 |

| Grades | Self-Awareness | Self-Management | Responsible Decision-Making | Interpersonal Skills | Social Awareness | Total Skills | % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1–2 | 22 | 13 | 36 | 65 | 13 | 149 | 9.70 |

| 2 | 46 | 21 | 52 | 94 | 23 | 236 | 15.37 |

| 3 | 57 | 40 | 55 | 74 | 19 | 245 | 15.96 |

| 4 | 44 | 39 | 31 | 91 | 25 | 230 | 14.98 |

| 5 (1 + 2) | 64 | 73 | 81 | 68 | 57 | 343 | 22.34 |

| 6 (1 + 2) | 63 | 72 | 74 | 57 | 66 | 332 | 21.62 |

| Total | 296 | 258 | 329 | 449 | 203 | 1535 | 100% |

| Book for Grade | Chapter Heading | Skill Category | Explicit | Focus |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | My family and me | Interpersonal skills | * | * |

| My friends and me | Interpersonal skills | * | * | |

| Holiday of holidays | Interpersonal skills | * | ||

| I’m calling | Interpersonal skills | * | * | |

| 3 | We chat with the family | Interpersonal skills | * | * |

| We cooperate with each other | Interpersonal skills | * | * | |

| 4 | Friends | Interpersonal skills | * | * |

| 6 | A thousand-mile journey | Relationships and self-management | * | |

| Me and everyone else | Social awareness | * | * |

| Class Book | No. of Exercises in Book | Activity in the Classroom | Activity Outside the Classroom | Exercises Promoting the Principle of Activity | % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 (1 + 2) | 589 | 7 | 1 | 8 | 3.13 |

| 2 | 389 | 28 | 1 | 29 | 11.37 |

| 3 | 501 | 17 | 2 | 19 | 7.45 |

| 4 | 406 | 54 | 5 | 59 | 23.13 |

| 5 (1 + 2) | 804 | 65 | 10 | 65 | 25.49 |

| 6 (1 + 2) | 651 | 72 | 3 | 75 | 29.41 |

| Total | 3340 | 233 | 22 | 255 | 7.63 |

| Total Exercises in the Books | Interaction in the Classroom | Interaction Outside the Classroom | Total Exercises Promoting Interaction |

|---|---|---|---|

| 3340 | 32 (74.41%) | 11 (25.58%) | 43 (1.28%) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Majadly, H.; Haj Yahya, A. Beyond the Language: Arabic Language Textbooks in Arab–Palestinian Society as Tools for Developing Social–Emotional Skills. Educ. Sci. 2024, 14, 1088. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14101088

Majadly H, Haj Yahya A. Beyond the Language: Arabic Language Textbooks in Arab–Palestinian Society as Tools for Developing Social–Emotional Skills. Education Sciences. 2024; 14(10):1088. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14101088

Chicago/Turabian StyleMajadly, Haifaa, and Athar Haj Yahya. 2024. "Beyond the Language: Arabic Language Textbooks in Arab–Palestinian Society as Tools for Developing Social–Emotional Skills" Education Sciences 14, no. 10: 1088. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14101088

APA StyleMajadly, H., & Haj Yahya, A. (2024). Beyond the Language: Arabic Language Textbooks in Arab–Palestinian Society as Tools for Developing Social–Emotional Skills. Education Sciences, 14(10), 1088. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14101088