Abstract

In the last decade data-based decision making has been promoted to stimulate school improvement and student learning. However, many teachers struggle with one or more elements of data-based decision making, as they are often not data literate. In this exploratory study, professional learning networks are presented as a way to provide access to data literacy that is not available in schools. Through interviews with scientific experts (n = 14), professional learning networks are shown to contribute to data-based decision making in four ways: (1) by regulating motivation and emotions throughout the process, (2) by encouraging cooperation by sharing different perspectives and experiences, (3) increasing collaboration to solve complex educational problems, and (4) encouraging both inward and outward brokering of knowledge. The experts interviewed have varying experiences on whether professional learning networks should have a homogenous and heterogenous composition, the degree of involvement of the school leaders, and which competencies a facilitator needs to facilitate the process of data-based decision making in a professional learning network.

1. Introduction

Over the years, much data have become available for school teams. However, the fact that these data are available does not automatically lead to improved educational practices. There is growing evidence that when data are systematically collected, analyzed, and added to the decision-making process to inform actions (cf. data-based decision making), they serve as a counterbalance to the potential biases stemming from intuitive decisions [1]. Moreover, they enhance the reliability and validity of the decisions made. This way, data-based decision making (DBDM) can lead to school improvement and the enhancement of student learning [2].

Teachers’ capacity to engage in DBDM includes a wide set of necessary knowledge, attitudes, and skills, often referred to as “data literacy”. Data literacy is defined by Mandinach and Gummer [3] as “the ability to transform information into actionable instructional knowledge and practices by collecting, analyzing, and interpreting all types of data to help determine instructional steps. It combines an understanding of data with standards, disciplinary knowledge and practices, curricular knowledge, pedagogical content knowledge, and an understanding of how children learn” (p. 367). Almost all teachers encounter difficulties dealing with one or more elements of data literacy. Examples include difficulties with analyzing data using tools like Excel’s formula function [4] and interpreting data due to the complexities of visual, verbal, and mathematical elements [5]. Some teachers skip crucial steps in the inquiry process, such as implementing solutions before verifying the assumed problems through data analysis [4]. Additionally, they may have a generally negative attitude towards data use or lack confidence in their own abilities to effectively use data [6].

As data literacy is often not fully developed in schools, using in-school collaboration as a way to bridge gaps in teachers’ knowledge and skills becomes challenging. School-external collaboration provides a solution, as it can provide access to expertise that is present outside of the school [7]. Professional learning networks (PLNs) provide a way for teachers to connect with others from outside their daily practice. PLNs are defined as “any group who engages in collaborative learning with others outside of their everyday community of practice to improve teaching and learning in their school(s) and/or the school system more widely” [8] (p. 2). In this paper, “others outside of their everyday community of practice” is further specified to include one or more school-external members with whom teachers work together structurally.

Researchers and policymakers are aware of the added value of PLNs, as data literacy professionalization interventions often include a PLN structure (see, for example, [9]). Despite the great potential of PLNs and their implementation in practice in terms of how they influence data literacy and in turn DBDM, this tends not to be a focus of research. Expert interviews are a way to have access to this under-researched topic and obtain information derived from DBDM interventions.

To address this gap, this exploratory study interviewed scientific experts who have knowledge and experience in implementing and researching DBDM interventions that include a PLN component. This allows us to bring to the surface knowledge that is implicitly present in DBDM interventions but has not yet been reported in the literature.

The research questions are as follows:

- According to the experts, what are the important design principles to allow a PLN to support data literacy and DBDM?

- According to the experts, what are unique ways PLNs contribute to data literacy and DBDM?

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. Data-Based Decision Making and Data Literacy

Data in education is defined by Lai and Schildkamp [10] as “information that is collected and organized to represent some aspect of schools” (p. 10). This includes, for example, assessment data, learning analytics, and observations. To turn these data into meaningful decisions, it is necessary to follow a DBDM cycle. The general theory of action underlying DBDM is that by using and/or collecting relevant data to investigate how a predefined goal can be achieved, a more accurate analysis of the situation can be made, leading to more profound decisions for action, which in turn leads to improved student learning. Although DBDM interventions opt for different models of the DBDM cycle, the core stays the same: all models use an adaptation of the scientific inquiry circle [11,12]. In this paper, when we refer to the DBDM cycle, we refer to five core steps, namely, goal setting, data collection, data analysis and interpretation, improvement actions, and evaluation. Consequently, data literacy includes the knowledge and skills to (1) collect, read, understand, and evaluate quantitative and qualitative data and results of basic quantitative and qualitative analysis and (2) use this information to support DBDM [3,12].

Research on the effects of DBDM has long been inconclusive, but the most recent evidence shows small and mostly positive effects. A review study by Marsh [7] on data use interventions shows that there are mixed effects of DBDM on data users, organization, and students, with half of the studies reporting positive effects and the other half reporting mixed or negative effects. However, more recent reviews are positive about the impact of DBDM interventions on student outcomes [2,13]. The meta-analysis of Ansyari et al. [2] summarizes evidence from 27 articles on the effect of data use interventions on student outcomes and reports an overall small positive effect size of 0.17. The effect of interventions is not direct but is rather mediated by teachers’ increased knowledge and skills, as well as improved instructional practices [2].

Research on DBDM interventions acknowledges that DBDM is a complex process that is influenced by an interplay of context, data, and individuals (for example, [7,14,15]). Data literacy as an individual characteristic is mentioned as an important enabler. However, research in recent years suggests that almost all teachers struggle with data literacy [4,16]. This raises the question of whether it is realistic to expect every teacher to be data literate. Instead of categorizing data literacy as an individual characteristic, it could be approached as a team characteristic where different types of expertise on the part of team members complement each other [17]. This way, the lack of individual data literacy can be overcome by colleagues interacting with one another, making DBDM a collective endeavor [18].

The notion of DBDM as a collective endeavor is not new, as it has often been a key ingredient in DBDM interventions [2,7]. These interventions often employ the term “collaboration” as a broad concept, including various types of interaction. However, it tends to lack specificity regarding the nature of collaboration and the level of interdependency involved in these interactions [18]. These researchers call for a distinction between individual, cooperative, and collaborative DBDM, depending on the degree of interdependence that is inherent in the DBDM cycle. Individual DBDM is initiated and undertaken solely by individuals, without any form of interaction taking place. Cooperative DBDM has an interactive component, where individuals interact with each other to achieve their own specific DBDM goal. In collaborative DBDM, a group of individuals have a common goal achieved by engaging in the DBDM cycle together [18].

In short, the lack of individual data literacy can be remedied by the knowledge and expertise of other teachers through cooperation or collaboration. However, sometimes the needed data literacy falls beyond the capacity of the school team. Rincon-Gallardo and Fullan [19] call for “outward brokering” as an opportunity to bring together expertise that is not present in the school: “When the problem of practice at hand requires expertise that falls beyond the capacity of the group (…) activating these outside connections can offer access to required expertise and new ideas” (p. 16). In this explorative paper, PLNs are put forward as a promising strategy to connect teachers with others from outside their daily practice in order to bridge the data literacy gap.

2.2. Professional Learning Networks

There is a strong tradition of research with regard to teacher collaboration, such as a consideration of professional learning communities (PLC) [20]. In their fundamental review of PLCs, Stoll and colleagues [21] concluded that if schools aim to make their PLCs stronger and more sustainable, they need external support from networks and other forms of partnerships. However, up until now, research into PLCs has focused on collaboration within schools. Brown and Poortman [8] therefore suggest the concept of PLNs, that focuses explicitly on collaborative learning with others outside of their everyday community of practice (p. 2). It is important to note that the broad term “outside their everyday community practice” could, in some interpretations, include members of the same school or organization with whom there had been no prior collaboration [22]. Therefore, in this paper, we adopted the distinction suggested by Lai and McNaughton [22], which differentiates between collaboration with members of the same school (PLC) and cross-school collaboration (PLN). PLNs are considered a more complex form of PLC, as they encompass any collaboration that extends beyond the immediate school context. This can involve a PLC that includes external members, such as academic experts or policy stakeholders, or it may connect multiple teachers and stakeholders across different schools. To avoid confusion, in this paper, we use the term “PLN” to refer to PLCs that include one or more school-external structural members or collaborations that span across school boundaries.

The unique contribution of PLNs lies in the access to external resources, expertise, and knowledge that would otherwise remain untapped. If such access is achieved, good ideas generated by individuals can be tested and further developed, and they can flourish into innovations and solutions to complex problems; otherwise, they would remain in isolated classrooms or schools [19]. In addition, Lai and McNaughton [22] stress that PLNs meet the demands of an increasingly complex and fast-changing educational context that can only be met by involving partners outside of school in the broader community such as social workers, policymakers, and other specialists.

The conceptual framework developed by Poortman and colleagues [23] outlines five critical enactment processes that are believed to influence professional learning network (PLN) outcomes: collaboration; reflective inquiry; a shared focus on student learning; leadership; and boundary crossing, which involves sharing knowledge developed within the PLN with others outside of it. Additionally, the framework considers the impact of individual, school, and policy context factors on these processes.

Collaboration within the network requires participants to engage in joint work, where they are willing to examine and challenge their beliefs and practices [24]. This process relies heavily on building strong, trusting relationships, as trust is essential for fostering cognitive conflict that can lead to changes in opinions, ideas, and behaviors. Even when group members hold differing views, working and reflecting together can build trust and strengthen these relationships [25].

Reflective professional inquiry involves teachers discussing and evaluating their teaching practices with the aim of continuous improvement. This process includes activities like teacher learning, reflective dialogue, and deprivatization of practice, where ideas from conversations, data, and literature are applied to improve teaching [23].

A shared sense of purpose, specifically focused on student learning, is crucial for the effectiveness of a PLN. The individual goals of members must align with the collective goal of the PLN. Katz and Earl [24] emphasize that the network’s focus should encompass learning at all levels: teachers, students, and the collective as a whole.

Leadership plays a vital role at various levels within the network, including both informal and formal leadership roles, as well as leadership at the PLN and school levels. The primary focus of leadership within a PLN is to monitor and facilitate learning, ensuring that the network’s activities remain aligned with its goals.

Boundary crossing involves disseminating and further developing knowledge generated within the PLN to colleagues in participating schools and other external institutions. Rincon-Gallardo and Fullan [19] further highlight the importance of forming new partnerships with students, teachers, families, and communities to extend the reach and impact of the PLN’s work.

Finally, Poortman and colleagues [23] identify several factors that influence these enactment processes at the individual, school, and policy levels. At the individual level, the knowledge, skills, and attitudes of participants are critical. At the school level, factors such as the size and composition of the PLN, network leadership, and the extent to which the school provides time and resources for network participation are influential. At the policy level, elements such as work pressure, staff turnover, and the degree of support and accountability can either encourage or hinder teacher participation in the PLN.

Although PLNs have great theoretical potential, and the implementation of PLNs is highly prevalent, currently the empirical evidence with regard to the effects of PLNs is still scarce [23,24,26,27]. Current research shows moderately positive and positive effects on teachers’ perceptions of acquired knowledge and skills, attitudes, and the application of knowledge and skills for practice [28]. However, limited research has been performed that causally connects PLN activities with improved student learning [19,29]. A significant effect on student achievement was found by Lai and colleagues [30], while Chapman and Muijs [31] found that schools that established a collaborative partnership in federations performed significantly better than non-federated schools. Still, how exactly PLNs have an impact on teacher, student, and school outcomes remains a black box, and further research is needed.

3. Method

3.1. Expert Interviews

Expert interviews provide fast access to unknown research fields and are a quick way to obtain information. The terms “experts” and “expert knowledge” are often contested, as their definition is debatable [32]. Nonetheless, expert interviews are described as a valuable and legitimate research method to uncover insider process knowledge on complex problems [32]. How “expert” is defined can vary from people holding knowledge of practice to people in possession of scientific knowledge. In this study, we focus on a selection of experts who are directly involved with research on interventions with both a DBDM and a PLN component.

We identified experts based on a literature review of DBDM interventions in Web of Science. Variations on DBDM were also included, such as data-informed decision making or evidence-based decision making. We then selected interventions that focused on stimulating teachers’ DBDM and integrated PLNs as part of the intervention. In total, 24 international researchers who were directly involved in such interventions and publications were invited for an interview. Out of these, 12 researchers accepted the interview invitation; 6 did not respond; and 4 declined, citing either a lack of involvement in the specific intervention or insufficient knowledge of the topic. However, those who declined referred us to 4 other experts. Among these referrals, 3 had already been contacted by us, and 1 new researcher was contacted and agreed to participate, bringing the total number of interviewed researchers to 13. Additionally, we asked all 13 interviewed researchers for further expert recommendations, resulting in one more project being suggested. The researcher associated with this project was contacted and subsequently interviewed. In total, 14 experts were interviewed, affiliated with institutions in the following countries: Belgium, Canada, New Zealand, Switzerland, the Netherlands, the United Kingdom, and the United States of America. The experts played varying roles in the interventions, including conceptualizing the interventions, facilitating them, researching their outcomes, or a combination of these roles. Table 1 provides an overview of the profile of the experts, illustrating their experience in the field.

Table 1.

Overview and profile of experts.

3.2. Interview Protocol

Following the recommendations of Van Audenhove and Donders [33], the expert interview was an open semi-structured interview using an interview protocol containing questions on the general outline of the intervention, what the rationale was behind implementing PLNs, who was involved, and the design decisions. Participants reflected both on their intervention(s) and their general experiences with DBDM and PLNs. The experts all signed an informed consent form and agreed for the interview to be recorded. The duration of the interviews was between 30 and 60 min.

3.3. Analysis

The interviews were transcribed verbatim from the recordings. Because this study was exploratory in character, a thematic analysis was conducted [34]. Thematic analysis uses both inductive and deductive coding techniques [35]. First, we created a codebook based on the theoretical framework, combining influential factors related to DBDM (e.g., training and support, individual knowledge, and skills) and PLNs (e.g., knowledge brokerage, reflective inquiry). We familiarized ourselves with the data by reading the transcriptions several times, and a first round of coding was undertaken by the first author using NVIVO. Each segment was given a code following the codebook. Based on the first coding, we developed themes by looking at clusters of codes relating to the topic (e.g., leadership). Through semantic and latent analysis, we examined concepts and theoretical perspectives used implicitly and explicitly by participants. These inductive codes were added to the codebook (e.g., intentional disruption, transformational leadership) (see Appendix A). Afterward, we compared the experts’ insights, allowing us to see if the experts’ opinions in the field aligned or differed.

The second coder was introduced to the codebook, where the first coder explained each code and provided detailed definitions and examples. The second author coded approximately 10% of the transcripts (n = 3) independently. Intercoder reliability was then measured to guarantee validity and consistency. The intercoder reliability agreement was measured in NVIVO through Cohen’s Kappa coefficient. This resulted in a Cohen’s Kappa of 0.85, which was above the acceptable level of reliability Cohen’s Kappa coefficient (κ) of 0.70. In order to further improve the quality of the coding, the codes with the lowest Cohen’s Kappa coefficient were then discussed to clear all ambiguities. This step resulted in codes being modified, removed, or merged. The final Cohen’s Kappa was 0.91.

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. How Professional Learning Networks Are Designed to Support Data Literacy and Data-Based Decision Making

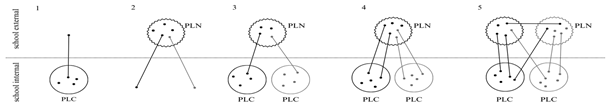

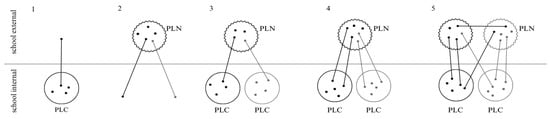

Five distinct designs for integrating PLNs within a DBDM intervention are illustrated in Figure 1. The depicted designs are an abstraction of reality. Depending on the context, combinations of the designs occurred. The first design involves teachers utilizing data within a PLC with the inclusion of an external member such as a coach, specialist, or invited expert. The second design pertains to a PLN where individual teachers participate in a between-school PLN, without a collaborative DBDM structure in their own schools. The third type encompasses teachers who are part of a DBDM PLC in their own school and also participate individually in a PLN. The fourth type is similar to type 3 but involves multiple teachers from the same PLC participating in a PLN. Lastly, the fifth type includes multiple teachers who engage in multiple PLNs with overlapping membership, creating a complex web of collaboration.

Figure 1.

Overview of designs of professional learning networks in data-based decision-making interventions.

To support data literacy, experts identified enabling conditions for PLN designs that align with established research on key influencing factors, such as time allocation and teacher attitudes toward PLNs. Such enablers have been discussed extensively in previous research, so they will not be detailed further here (see for example [23]). Experts also highlighted three important design decisions to be made where no consensus has been established, namely, (1) a homogeneous versus heterogeneous grouping of PLN members, (2) the degree and type of involvement of the school leader in the PLN, and (3) the role of the PLN facilitator.

4.1.1. Homogeneous vs. Heterogeneous Composition

Experts described a variety of characteristics that are used to group teachers when it comes to forming PLNs with a focus on DBDM: (1) the subject area teachers were teaching (same subject area or different subject area), (2) the level of data literacy, (3) the level of teaching experience, (4) school performance (high performing–low performing), (5) the student population (e.g., at-risk students), (6) the topic the PLCs are working on, (7) the geographical location of schools or teachers’ questions, and (8) needs around the DBDM cycle. Homogeneous PLNs are preferred when there is a need to enhance and share specialized knowledge and strategies within specific subject areas or related to mutual topics and challenges. By bringing together individuals with similar backgrounds and expertise, these PLNs facilitate focused discussions and the exchange of in-depth insights and ideas. Heterogeneity is favored as it brings together individuals with diverse perspectives and experiences, which enables out-of-the-box brainstorming and provides access to a broader range of ideas and approaches. This type of network is particularly valuable when addressing complex problems that benefit from collaboration with stakeholders from different backgrounds and expertise.

Three experts (1, 5, 13) reported their preference for grouping teachers with the same subject area together, as teachers tend to be more motivated when the content is easily transferable to the classroom. When it comes to the level of data literacy, similar arguments are used. On the other hand, a discrepancy in terms of levels of data literacy can be demotivating and slow the process down:

So you have people who are very good with data and people who know nothing at all about data, that doesn’t work. Because the people who are very good, they think it’s way too slow. The people who don’t know about anything yet, they think it’s going fast.(Expert 1)

The strategy of pairing up high and low performing schools was also explored. One expert noted that when highly and poorly performing schools work together, it becomes “a serving relationship” instead of an equal exchange. Expert 10 made the important addition of the need to avoid grouping schools together that were in competition with each other, as they could be reluctant to share information.

Other experts cluster teachers based on their subject or the topic they want to learn. If the subjects or topics are too far apart, PLN members are not likely to see the added value of working together. However, expert 14 noted that even if the topics were not aligned, the PLN had added value. The members might not expand their knowledge with regard to their topic, but they did in terms of going through the DBDM cycle:

[the topic] could be feedback, it could be meta-cognition (…) they kind of copy the process but on a different topic. In both cases, it seems to work actually.(Expert 14)

The tension between homogeneous and heterogeneous group composition is well-documented. The literature surrounding both teacher collaboration in general and collaborative DBDM has reported on this [20,36]. Teachers often prefer homogeneity because they tend to be more motivated when discussions are closely related to their classroom practice. This leads to interactions predominantly with colleagues who share similar ideas or opinions [37]. Teachers therefore possibly encounter confirmation of their own ideas instead of being exposed to contrasting ideas. Based on the experiences reported by the experts, we suggest a combination of both approaches in a PLN because both types of grouping may be beneficial, where, by mixing existing and newly invited members in the PLN, there are opportunities for both homogeneous and heterogeneous interactions. Such a complex PLN can be seen in Design 5, Figure 1, and this type of flexible grouping can provide a balance between shared experiences and diverse perspectives, which leads to richer interactions for the teachers involved.

4.1.2. The Role of School Leadership

All fourteen experts spoke of the importance of the role of school leaders in DBDM, as well as in PLNs. These comments are in line with previous research suggesting the need for actions linked to transformational leadership, such as creating a shared language around data, scheduling in such a way that teachers are free to attend data meetings, or integrating actions into school policy [23,24]. However, there tends to be a discrepancy between experts’ opinions on whether or not school leaders should be directly involved in PLNs.

Four experts (1, 2, 10, 12) explicitly argued for school leaders to participate as members of the PLN. The main reason concerns the sustainable implementation of the actions created through the process of DBDM. If the school leader participates in the DBDM process, there is a greater chance that knowledge and actions will be integrated into school policy:

The moment the school leader joins the team, that gives some status right away because it shows it’s important. As a school leader, you are also kind of a role model to use data. It also helps reassure the members that if they come up with the actions, that they are going to be implemented.(Expert 1)

Another argument made by two experts with regard to the direct involvement of school leaders is that it is part of the school leader’s job to be concerned with student data and related instructional decisions. Expert 10 refers to the concept of instructional leadership, which focuses on influencing the learning of students through the behavior and learning of teachers [38]. Participating in the PLN is a way for the instructional leader to participate in the pedagogical and didactic decision making of a teacher in their classroom. Expert 6, on the other hand, commented on the conflicting dual role of school leaders if they participate, because “the issue with the principal is that because they do teacher evaluation, teachers often feel more ill-at-ease [to collaborate around DBDM] as they might if it were a colleague or a peer”.

Three experts (4, 6, 13) argued against the constant presence of a school leader in the PLC and PLN. First, they mention that if school leaders give teachers autonomy and stimulate them to take on the role of leaders to make change happen, the school leader does not have to be present to ensure that the actions and knowledge generated will be implemented at the school level. Experts 13 and 14 support this view, referring to the concept of distributed leadership. Distributed leadership “encompasses leadership exercised by multiple leaders who work collaboratively across organizational levels and boundaries” [39]. So, by stimulating teachers in PLNs to take on the role of teacher leaders at their schools, a school leader’s presence in the PLN becomes unnecessary. Furthermore, two experts (4, 13) contend that while the DBDM process between teachers and school leaders is alike, their goals differ. While teachers concentrate on actions at the classroom level, school leaders prioritize actions at the school level and consider how the various actions contribute to the big picture:

You got to have the principal at the table, working out how this is going to happen. But you don’t want the principal sitting in meetings and meetings that are just discussing content area stuff. That is not their role, it’s a waste of time if they attend those kinds of data meetings, so yes you attend some, but they need to attend meetings which focus on in-depth data about what is going on with the resources (…) the principal needs the big picture. So, lumping everybody in one PLN will make it very difficult to achieve all the intended purposes.(Expert 4)

To maintain school leader involvement without their direct participation in the PLN, interventions could create a separate PLN specifically for school leaders, as shown in Design 5, Figure 1. Through regular joined sessions, the school leader stays on top of the teachers’ progress, while also focusing on making school-level decisions based on data.

Both points of view highlight the importance of school leaders having a comprehensive understanding of both the progress made in the PLC and PLN in order to effectively integrate them into school policies. This can be accomplished in two ways: either by actively involving the school leader as a member of the existing PLC and PLN, or by establishing a separate PLN specifically for school leaders that concentrates on aligning the diverse actions at the classroom and school levels. The choice depends on how leadership is shaped at the school level. If there is a culture of distributed leadership, with teachers who are used to taking on responsibility for school-wide challenges, it is not essential for the school leader to participate. If the role of teachers is focused on classroom practices, the instructional leader can model data use in the PLN, have an influence on the instructional actions in the classroom, and integrate them into school policy.

The literature further supports this approach. Robinson and colleagues [40] demonstrate that instructional leadership—especially when school leaders promote and participate in teacher learning and development—has the most substantial impact on student outcomes, with an effect size of 0.84. This is more significant than transformational leadership activities like setting goals (effect size 0.35) or providing resources (effect size 0.34). Therefore, transformational leadership activities should be closely aligned with instructional improvements to maximize their impact [41]. Additionally, the success of distributed leadership hinges on the support provided to PLN participants, enabling them to engage in networked activities and lead change within their schools [39]. Balancing this dual focus—on direct instructional leadership and supporting distributed leadership within PLNs—creates an environment to achieve the PLNs’ intended purposes.

4.1.3. The Role of the Facilitator

When discussing how to ensure the success of the PLN process, all experts emphasized the need for a facilitator. However, there is no single individual who is considered the ideal facilitator, as long as the selection is intentionally made based on the needed competencies. The most frequently mentioned knowledge and skills needed for the facilitator include data literacy and a solid understanding of the DBDM process, as well as effective coaching skills. Another mentioned responsibility of the facilitator is guiding the team to challenge persistent mindsets and biases. Conflict often arises when the data does not align with the teachers’ perspectives:

people have ideas that they are really convinced about, and then the data suddenly says something else. And then, starting the conversation about that, what do you think and what does the data say, and figuring that out, that’s very important. And a good coach really knows how to discuss that cognitive conflict within the team and they end up working through that.(Expert 1)

Experts highlight the crucial role of cognitive conflict and intentional interruption in PLNs. The importance of intentional interruption lies in the fact that humans have a natural bias to preserve their current ways of thinking [42]. To make changes in practice, these biases need to be confronted. Data can stimulate such a confrontation. However, it can also be manipulated to confirm and reinforce ideas. To ensure that members of the PLN do not attempt to use the data to affirm and confirm what they already know, the facilitator needs to spread awareness about these potential biases and create an atmosphere of trust, where members trust each other when it comes to challenging one another’s biases.

Previous research also highlights the critical role of facilitators or coaches in DBDM [7,43]. A recent systematic review shines a light on the role of facilitators in DBDM, often referred to as data coaches. Four categories of key competencies are identified: job-specific competencies, interpersonal competencies, content knowledge, and coaching competencies. The job-specific competencies focus mainly on supporting and guiding school teams through the process of DBDM. Interpersonal competencies include, for example, adult learning and fostering collaboration. The data coach should also have the necessary data literacy and knowledge to allow them to use data to adjust school and classroom practices. Lastly, a data coach should have coaching competencies [44]. Many of the tasks, skills, and competencies needed to facilitate the DBDM process in a PLC are transferable to facilitating the process in PLN. PLN facilitators distinguish themselves from PLC facilitators through an extra focus on the galvanization of trust and the formation of a community, as PLN members are often not acquainted. It is important that the PLN facilitator focuses on the kind of trust that means that teachers have confidence that, by disrupting each other’s status quo, they will improve each other’s practice.

4.2. How Learning Networks Contribute to Data Literacy and Data-Based Decision Making in a Unique Way

From the expert interviews, we identified four unique ways in which PLNs contribute to DBDM: (1) by regulating motivation and ventilating emotions, (2) by stimulating cooperation between schools, (3) by creating a space to collaborate with different stakeholders in order to tackle complex problems, and (4) by offering an opportunity for the inward and outward brokering of knowledge.

4.2.1. Emotion and Motivation Regulation

The experts highlight that DBDM is a long and complex process during which teachers can feel despondent and unmotivated. Five experts (1, 2, 3, 12, 13) explicitly stress that PLNs serve to attend to the emotional component of data use, because “sometimes people feel really demoralized by looking at their data and they say: I worked so hard. It’s all that emotional element of data use, it’s important but we don’t pay that much attention to it” (Expert 12). Installing a PLN creates the opportunity to meet other teachers and teams who experience similar emotions and run into the same challenges during the DBDM process. This connection, the community feeling of “being in this together” acts as an emotional regulator and motivates teachers, especially when they experience setbacks. They are reassured when they hear colleagues from other schools commenting on similar struggles and problems. This suggests that the PLN can act as a jumpstart to reignite the DBDM cycle when teams are demotivated:

by coming to the learning network, you are again stimulated to push through. Because you notice that others are also busy with data collection, encounter the same issues, working on the same theme. And that really does stimulate them to continue the cycle.(Expert 1)

As we know from the research on the influencing factors of DBDM [15], an individual’s disposition to use data forms an important enabler or barrier. The above-mentioned examples show that it is important to be attentive to the emotions and motivations at the teacher level, as well as at the team level. Adding a PLN structure to collaborative DBDM forms a way to attend to these emotions and the possible lack of motivation. It offers an emotional safe space to express one’s emotions and frustrations, and at the same time obtain support and inspiration to push through the setbacks.

4.2.2. Cooperation

In interventions where there is a PLC structure at school with a predefined goal for DBDM (as shown in Designs 3, 4, and 5 in Figure 1), a PLN is often added as a meeting space to encourage exchange between different teams. When looking at the DBDM cycle and the associated data literacy skills, eight experts mentioned the added value of a PLN, especially when data need to be analyzed and interpreted, when improvement actions need to be formulated, and afterward when the DBDM cycle is finished to share their process and experiences.

During data analysis and interpretation, expert 12 recalled that “teachers got together to look at data. It’s probably going to be a bit more general kinds of data, not so much data like ‘my student has this issue’. More patterns, like general ideas”. Another expert added that when it comes to national test results, it can be fruitful to compare the results side-by-side, providing support in the interpretation of the data, and providing a fresh perspective for its interpretation.

A PLN provides an opportunity for sharing ideas and strategies for improvement actions. PLN members can talk about curriculum standards and assessment and discuss what pedagogical strategies are working with the different populations of students. According to the experts, school teams have the tendency to have certain (incorrect) assumptions based on their experiences and habits of mind. PLN members can offer a fresh perspective on the situation because they stand further away from the others’ class and school context:

I have seen situations where they get locked into something and think some students can never achieve. (…) you need an external person who says “hey, think about it in a different way”. (…) They don’t have the assumptions of the schools of the students. They ask naïve questions that are actually very probing and get people to reflect, and that’s the role of externals.(Expert 12)

At the end of the DBDM cycle, a PLN can also be implemented to function as a conference involving invited guests, where the different teams walk each other through their cycle and show the actions and progress they have made.

For such an exchange between members to take place, the experts highlight the importance of both a willingness to share and the establishment of a safe context, where the shared information remains within the PLN: “Data has to stay indoors or not be shared further. You do have to make that explicit at the start, that people stick to that agreement” (Expert 10). A pitfall in sharing ideas in the PLN is that wrong information can seep into different schools: “We realized in the networks that people were just spreading around all the same things and the only thing worse than a bad idea is a bad idea in a lot of places” (Expert 7). Here lies an important responsibility for the facilitator, in line with Section 4.1.3. On the one hand, they stimulate members to offer a fresh perspective and share knowledge, but on the other hand, they critically challenge each other and to not copy/paste each other’s data interpretations and improvement actions.

As teams have their own goals at the school level and there is little interdependence between the PLN members, this falls under cooperative DBDM [17]. It can be hypothesized that when there is a PLC in place, a PLN acts as an opportunity for cooperation rather than collaboration. At first glance, this seems in conflict with the definition of a PLN provided by Brown and Poortman [8], where collaborative learning is described as a defining component. However, collaboration in terms of interventions is often used as an umbrella term incorporating various forms of interaction, without specifically defining the activities and degree of interdependence between members [20]. Poortman et al. [23] add that having ill-defined concepts of collaboration impedes making a clear connection between collaboration and outcomes on students, teachers, and at the school level. This paper attempts to unravel the concept of collaboration by making a distinction between cooperation and collaboration in the PLN.

4.2.3. Collaboration with Different Stakeholders

All experts agree that collaboration, where members have a common goal and tackle the DBDM cycle together, is important. However, most of the experts implemented this kind of collaboration within individual schools, rather than across schools. Five of the experts (2, 4, 7, 13, 14) designed collaboration on a PLN level, two of which included a PLC at the school level (see Design 5, Figure 1) and three without complementary PLCs (see Design 2, Figure 1). In short, alongside or in place of school-level PLCs, PLNs can provide another layer of collaboration to the DBDM process. This way, a PLN becomes a space where different stakeholders come together in equal partnership, and where ideas and actions generated by teachers and/or school teams can be tested and further developed in multiple settings. Expert 4 provided the example of how the PLN hosted multiple stakeholders including “school leaders, policy people, researchers, and other guest members” to address complex issues such as educational excellence and equity, which are too challenging to tackle within a PLC alone.

In addition to addressing complex challenges with various stakeholders, collaboration at the PLN level also fosters the joint development and refinement of ideas. Members collaboratively experiment with new concepts across different classrooms. This collaborative approach allows members to “develop a new idea and together try it out, providing feedback to each other” (Expert 14).

According to the experts, specific conditions must be established within the PLN to foster collaboration. Again, as mentioned in Section 4.1.3 and Section 4.2.2, it is important that teachers in the PLN critically challenge each other and push each other’s mindset. Expert 7 highlighted the necessity of protocols and structured guidelines to ensure constructive conflict: “So, you need structures in place that force the critical challenge through the use of things (…), that will actually force me to disagree with you”.

Next to this, “there has to be trust, there has to be a willingness to expose one’s weaknesses, there has to be a willingness to accept and take on board new ideas, it’s a very deep form of collaboration” expert 14 added. However, expert 7 warned that not all trust is beneficial; ideal trust should encourage candid feedback and personal growth, not just unconditional support. Lastly, the PLN needs to be considered as a place for equal partnership where all participants, regardless of their background, are equally valued and contribute to shared goals. Expert 13 describes this collaborative environment as a “third space” or hybrid learning environment, where diverse expertise comes together to improve their practice:

What is also important is that equal partnership, and we often talk about a third space that we want to create or the hybrid learning environment, because we are convinced that by bringing together different stakeholders, you actually bring in different areas of expertise. Expertise, but in an equal way (…). But everyone who sits at the table there actually has the goal of improving that practice.(Expert 13)

The literature on third space theorizes benefits similar to the arguments used in this section. However, continual re-mediation is needed, as members in third spaces have different backgrounds and are continuously sculpting intersubjectivity and a shared vision [45].

In a review conducted by Marsh [7], it was found that collaboration at different levels is essential for successful DBDM. Cross-school collaboration was identified as a key ingredient in this process. However, the nature of collaboration in interventions is often ill-defined, making it unclear which types of collaboration lead to successful DBDM. The interviews conducted reveal that PLNs are frequently utilized to stimulate cooperation between teachers, rather than collaboration. This raises the question of whether PLNs need to foster collaboration if collaboration already occurs within PLCs at the school level. If not, PLNs could act as a substitute. Nonetheless, two experts, as illustrated in Design 5 (Figure 1), emphasize the power created when different collaborative structures with different focuses are implemented to achieve a common goal.

4.2.4. Inward and Outward Brokering of Knowledge

As DBDM is a complex process, teachers and school teams need to be data literate and possess a range of skills, such as content knowledge, knowledge of the school vision, and knowledge of the curriculum. Eight experts (2, 3, 4, 6, 7, 8, 13, 14) reported on implementing PLN as a way for teachers to improve their data literacy (outward brokering) and in turn implement the newly acquired knowledge back into the PLC in their school (inward brokering). Outward brokering of knowledge involves the process of teachers accessing external knowledge and expertise on data literacy in the PLN in order to allow them to successfully complete the DBDM cycle:

That is providing support for the questions that teachers run into going through a DBDM cycle. Yes, really, sometimes very practical questions, research skills that they don’t have, when they don’t know how to deal with data analysis for example, all those elements, so the practical learning questions that they have.(Expert 13)

Expert 7 adds that the PLN in itself is just a processing form. The content is derived from the members, who bring in scientific articles or invite experts to host workshops. The facilitator plays an important role in the outward brokering process, because “if at that moment there is no input and they [the teachers in the PLN] can’t help each other and they just rely on their own gut feeling, then of course you are no longer working in a data-informed way. And it’s important that you have a facilitator who can respond to the questions that come up and who can refer to evidence or other good practices” (Expert 13).

Six experts (2, 4, 6, 7, 8, 13) expressed the aim for PLNs to go beyond the professionalization of the PLN members and stimulate inward brokering. In this case, members are trained to be “knowledge brokers”, in that they share the newly acquired data literacy in their own PLC. When the collaboration is located at the PLN level with no PLC at the school level (see Design 2, Figure 1), it should be an explicit strategy from the beginning to support teachers to become change agents and model the collaborative DBDM process from the PLN back at their school. When this is done successfully, they have the power to build large-scale capacity for data use:

Teachers come from different schools and they work together. (…) And we kind of found, if they set up a PLC within their schools, that seems to be very effective because they kind of like copying the processes they went through in the network back in their school.(Expert 14)

To successfully secure inward brokering, knowledge sharing needs to be a strategy from the beginning. The school leader plays an important role in facilitating this process and embedding the knowledge, actions, and DBDM at the school level. Expert 4 mentioned regular meetings between the school leader and the PLN members as a strategy: “the principals or the content area leaders, the teacher leaders, they come together, and they put all the information together: ‘how are we going to do that in our school’? So that’s where the joining of the dots and the coherence comes in”. Furthermore, it is important to decide which knowledge should be shared, at which level of detail, and through which activity.

Both inward and outward brokering of knowledge are important for fostering the advancement of data literacy in school teams. These processes facilitate the flow of information, ideas, and resources, ultimately contributing to large-scale DBDM. Previous research on knowledge brokering in PLCs also notes the importance of paying explicit attention to knowledge brokering as a strategy from the beginning [46,47]. Strategies are, for example, including an experienced staff member in the PLC, brainstorming with teachers outside the PLC, and sharing knowledge in the staff room, … [47]. Similar strategies can be used to support PLN members in terms of how they can implement their PLN knowledge back in the school. Another strategy to foster knowledge brokering is by participating in the PLN in conjunction with one or more school-based colleagues [48]. This leads to an increase in social and human capital. This way, the learning is sustained across spaces, allowing for shared learning in both the PLN and the school [48]. Hubers and Poortman [49] add that before knowledge can be shared back in the individual school, PLN members must collaboratively create a vision about what knowledge should be shared in their school.

5. Conclusions and Implications for Practice

In DBDM interventions, PLNs are often prevalent but tend not to be the research focus [9]. Knowledge with regard to the added value of PLNs for DBDM therefore remains implicit. This article draws on expert interviews (n = 14) to investigate key design principles for PLNs and their unique contributions to DBDM and data literacy. As presented in Table 2, our findings show that structuring PLNs effectively requires careful consideration of group composition, the involvement level of school leaders, and the roles of facilitators. In response to the question about unique contributions, experts noted that PLNs facilitate DBDM by regulating motivation, facilitating emotional expression, encouraging cooperation across institutions, enabling problem solving with diverse stakeholders, and promoting the sharing of knowledge both within and outside the network.

Table 2.

Summary of the main results.

Based on the results and connected literature, we formulated seven practical implications:

First, consider PLN goals when making design decisions. When designing a PLN to support DBDM, it is essential to clearly define the goals that the PLN intends to pursue. Additionally, the structure of the PLN should consider the existing data culture in the school and how it interacts with other collaboration structures, such as PLCs, that may already engage in data-driven practices. Choices in design may include selecting the same or different subject area teachers, data literacy levels, teaching experience, student population, performance results, or the specific topic PLCs are focusing on. Homogeneous groups might focus on refining specific data use practices. For example, math teachers in a homogeneous PLN group might focus on refining their methods for analyzing student error patterns in problem solving to better tailor their instructional strategies. Heterogeneous groups could address broader, more complex challenges that require diverse perspectives and data sources, such as equity issues. A heterogeneous PLN group could tackle these by analyzing and addressing disparities in student achievement across different demographic groups, using a combination of academic performance data, attendance records, and socioeconomic information.

Secondly, decide on the degree and type of involvement of the school leader. Next to tasks of transformational leadership, such as creating a data culture and freeing up time and space for teachers to engage with both data and the PLN, the type of involvement should be carefully considered. To effectively implement the knowledge and actions derived from the DBDM cycle at the school level, it is crucial the school leader is involved in the process. This can be achieved through two approaches, depending on the leadership style. If the school has a culture of instructional leadership where the role of teachers primarily revolves around classroom practices and there is limited engagement in school-wide decision making, the school leader’s active participation in the PLC and PLN becomes crucial. Instructional leaders, by actively participating in PLNs, use their deep dive into classroom data to align teaching strategies with school-wide educational goals. For instance, if data show that a particular grade level is struggling with math, the school leader could help develop strategies within the PLN to address these issues and ensure that these are integrated into the school’s broader math curriculum and professional development plans. In addition, it enhances the prestige of both the PLN and the DBDM process. If there is a culture of distributed leadership with teachers being accustomed to taking on responsibility for school-wide challenges, it may not be necessary for the school leader to participate directly in the PLN. In a distributed leadership model, school leaders oversee the strategic integration of PLN outcomes into school policies rather than engaging in day-to-day data analysis. Regular meetings to update the school leader are essential in guaranteeing the successful implementation of knowledge and proposed actions. This approach allows the school leader to focus on making decisions based on school-level data and decisions, such as aggregated scores from standardized assessments, rather than being directly involved in the classroom-level process.

Thirdly, as a facilitator, focus on developing skills in community building and intentional interruption, where deliberate challenges to existing perspectives enhance collaborative learning within a PLN. The facilitator should have similar competencies as a data coach, namely, job-specific competencies (e.g., guiding PLN members through the DBDM cycle), interpersonal competencies (e.g., working with adults and having experience of adult learning), content knowledge (e.g., data literacy and pedagogical content knowledge), and coaching competencies (e.g., confronting cognitive biases). PLN facilitators distinguish themselves from data coaches through the additional focus on the galvanization of trust and the formation of a community, as PLN members are often not initially acquainted. Essential to this role, the facilitator must cultivate a form of trust that encourages teachers to openly challenge each other’s biases, a process that significantly contributes to refining and improving each other’s practice.

Fourth, recognize the importance of emotions. Emotions play a significant role in how educators engage with data. Data often act as a mirror, reflecting educators’ own practices and highlighting areas for potential improvement. This process of being confronted with one’s own performance and the subsequent need for change can be emotionally charged. Additionally, the process itself can be lengthy and demotivating, especially when it involves testing various hypotheses and adjusting strategies based on trial and error. It is essential to create a safe space within the PLN where members can openly discuss their feelings about data use. This emotional awareness can help the PLN address potential resistance to DBDM and foster a more supportive environment where members are encouraged to engage with data critically and constructively. The vulnerability involved in sharing and discussing these emotions can also reinforce relationship building between participants. This can be achieved by explicitly asking about their feelings, or by encouraging informal conversations by offering appropriate hospitality.

Fifth, use a structured sharing protocol to facilitate the exchange of data-related knowledge, strategies, and inspirational practices within PLNs. This protocol should encourage members to openly discuss their data practices, describing the processes they followed, the decisions they made, and both the successes and challenges they encountered. It must also include clear guidelines to keep discussions about student data private, ensuring trust and appropriate handling of sensitive information between schools. Additionally, the protocol should provide practical ways for members to extend the reach of data-driven practices beyond the PLN, helping to spread these insights and enhance their impact.

Sixth, determine whether cooperation or collaboration is more suitable within the PLN. If collaborative work takes place within the school, a PLN can assume the responsibility of addressing emotional aspects, facilitating inward and outward brokering, as well as stimulating cooperation during the inquiry circle. This might involve activities such as verifying the accuracy of interpretations of student performance data or brainstorming and providing feedback on various hypotheses and actions. In situations where collaboration is not feasible within the school, such as may be the case in small schools, a PLN can focus on establishing a common goal, such as using assessment data to develop targeted interventions for struggling students. Regardless of the starting point, DBDM benefits immensely from both cooperative and collaborative efforts across multiple levels—the classroom, departmentally, and school-wide. Such an approach ensures that data-driven practices are being refined and broadly implemented.

Lastly, empower PLN members as knowledge brokers. PLN members should be encouraged and supported in becoming knowledge brokers who actively bring in and construct knowledge, and afterwards disseminate the knowledge generated within the PLN back to their respective schools. Based on the needs of the members, knowledge can be brought in through the facilitator by accessing scientific literature, listening to an invited speaker, or accessing expertise that is present within the PLN. Inward brokering should be strategically planned from the start. This process includes the introduction of new tools and strategies, like integrating learning analytics dashboards or implementing curriculum improvements into school practices. Strategies include involving multiple staff members from a school in the PLN; making arrangements to engage the school leader in the process; talking to colleagues in the staff room about the goals and processes of the PLN; and providing updates on the work of the PLN at set times with the school team, e.g., at a staff meeting.

6. Limitations and Suggestions for Further Research

While this study provides valuable insights, it is not without its limitations. One limitation is the reliance on academic experts as the primary source of information. It is important to recognize that expert knowledge is not neutral, as it is influenced by power relations and tends to perpetuate existing knowledge rather than promote innovation [33]. Moreover, expert interviews lack inter-subjective repeatability [33]. In addition, academic researchers typically focus on studying PLNs supporting DBDM rather than leading and organizing them, resulting in different perspectives and expertise compared to practitioners. In this article, the voices of practitioners and their practical expertise were not included. Future research should be conducted to explore the perceived benefits of PLNs in supporting DBDM in order to identify their preferred composition.

For confirmability of the results, we relied on transcription and triangulation with existing literature, although incorporating additional forms of data, such as interviews with practitioners, might have offered further insights and strengthened the study’s validation process. Interviewees reviewed transcriptions, but an additional verification method could have enriched the analysis.

To address these limitations and better understand the extent to which the findings are agreed upon across the field, future research could explore the level of consensus among experts regarding the outcomes of the study through a survey. This approach would provide a quantitative measure of agreement and potentially validate the generalizability of the findings. Given the exploratory nature of this study involving 14 experts, the findings cannot be generalized. However, they do offer insights into the potential added value of PLNs in supporting DBDM and into possible compositions. Further research is necessary to deepen our understanding of the most effective composition for achieving different outcomes within specific contexts.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.W. and E.C.; methodology, A.W. and I.D.; formal analysis, A.W. and I.D.; writing—original draft preparation, A.W.; writing—review and editing, A.W., I.D., R.V.G., K.S. and E.C.; visualization, A.W.; supervision, E.C.; project administration, R.V.G.; funding acquisition, E.C., R.V.G. and K.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study is part of a research project on the use of feedback from standardized tests within the Steunpunt Centrale Toetsen in Onderwijs, funded by the Flemish Ministry of Education and Training (Flanders, Belgium).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by approved by the Human Sciences Ethics Committee of the Vrije Universiteit Brussel (Approval Code: ECHW_402.02) on the 2 February 2023.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author due to privacy.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A. Overview of the Codebook

| Codes | Description | Examples |

| General | ||

| Intervention information | General details about the intervention, including who is involved, timing, location, objectives, … | To ensure anonymity, no example of an intervention is provided. |

| Inquiry cycle and intended goal | The followed method and/or steps to use data and evidence to inform their decisions (such as instructional decisions, school policy strategies, …). | “So because we follow the data cycle, there’s a rough agenda that covers each meeting, but we don’t say do X at this point, but we know the rough agenda follows the cycle: beginning of the year is starting with last year data, middle of the year monitoring and evaluating as we go, and that’s how it keeps ticking”. (Expert 4) |

| Used data | The data and/or evidence used (e.g., standardized test results, observations, …) and data characteristics, such as quality. | “And the data is slightly different too. The more we go down to the teacher level, the more disaggregated it becomes. So when we go to the ultimate teacher level, we look at the class of individual assessments and everything else, alongside the other big picture data, but the focus is more on this aggregated level of groupings within their classroom. What we need for up the school, the data is more schoolwide so they’re slightly different, slightly different displays of data. It’s more than different questions, it’s how the data are displayed and discussed. It’s relevant to the roles and the kind of decision they need to make”. (Expert 4) |

| Added value of PLN | The rationale and benefits of integrating a PLN component into the intervention, highlighting its added value. | “One of the best things came up early. When they realized they needed a data privacy policy, because there has never been a privacy policy because there has never been data, everybody realized, there’s no reason to believe that privacy guidelines would be different from one school district to the next. Why wouldn’t you just get together and come up with one? You don’t do this 19 different times or in our case 72 different times so things like that you know… efficiency”. (Expert 7) |

| Design decisions of PLN | ||

| Composition | ||

| Homogenous * | The PLN is composed of individuals with similar characteristics. | “One of the things we still find difficult is the degree of homogeneity or heterogeneity in a team (…) when it comes to data literacy and people are too diverse, so you have people who are very good with data and people who don’t know anything at all about data, that doesn’t work. Because the people who are very good, they think it’s way too slow. The people who don’t know about anything yet, they think it’s going fast. So we are still trying to find the right balance”. (Expert 1) |

| Heterogeneous * | The PLN is composed of individuals with different characteristics. | “When you got highly performing and poorly performing often it become a serve our relationship or a kind of you got to tell us how to do things, where if you got schools who are the same, their like okay we need to get to work on this together” (Expert 14) |

| Roles | ||

| Facilitator | Individuals who play an important role in organizing and/or guiding DBDM processes and activities within PLNs. | “They all have a leader, every PLN has a leader, and that leader has typically been someone from the schools, not externals, well in some places they have an external person, but predominantly those are led by one person in the schools who has both the organization and management and leadership skills and the content area skills available to lead that group. Whether you have an internal or external it depends on who has the right knowledge to support the inquiry process”. (Expert 4) |

| Knowledge and skills | The needed competencies to support and facilitate both the process of DBDM and the activities in the PLN. | “You can’t just leave this to anyone; it has to be people who either systematically master their way of working or can truly develop their skills in that area. They need to be able to use both data and literature, but also understand how adults learn and can coach that process”. (Expert 2) |

| School leader | Highlights the role and type of leadership in activities influencing DBDM both within the school and in the PLN. | |

| Instructional * | Leadership activities that primarily focus on curriculum, teaching quality, and student learning within the DBDM process. | “If you are a school leader, you are also concerned with didactics. If you’re an individual teacher, you’re just concerned with what’s going on in your classroom. A principal makes different decisions after the fact, but meanwhile, there’s a lot in common (…) if it’s about concepts or interpretations of grades, this is common if you start creating networks”. |

| Distributed or shared * | Instances where leadership responsibilities are shared among different members of the PLN, creating ownership, rather than centralized in a single leader. | “I think having some kind of champions around the teacher’s staff, but it’s got to be some teacher leaders, can you form a network of teacher leaders across, you could get whole teams together across schools and say who’s the leader here and they can share their best practices”. (Expert 12) |

| Transformational * | Leadership activities that encourage, inspire, and motivate the use of data and participation in PLN activities. | “And you gotta have a culture of innovation and that kind of gets from the leader who has two ways of dealing with that: he can be a transformational leader and he can be like a kind of instructional leader. And the transformational leader is, you know, the one who said this is gonna be done round here. The instructional leader models those processes, so this is gonna be done around here, and let me show you how to do it. And they kind of model what needs to be done, so the leader themself has to place a kind of culture in which it’s okay to fail to take risks, as long as we learn from this”. (Expert 14) |

| Participant | ||

| Dispositions | Examines individual attitudes and motivations toward DBDM and engagement in the PLN. | “It’s always shocking when people say, for example, ‘I don’t have time for the PLC and the network, I don’t want to participate’, and then I somewhat provocatively respond, ‘So you don’t want to improve your students’ learning’? They start with whether they have time or not, rather than starting with, ‘I’m facing this issue with the students’. It’s super important to change that mindset, and from there, we can work together. The collaboration doesn’t have to be identical at the network and PLC levels, but they do need to align”. (Expert 2) |

| Emotions * | Emotions impacting participants’ DBDM and involvement in the PLN. | “Sometimes people feel really demoralized by looking at their data and they say, “I worked so hard”, so make sure to really attend to those teachers’ emotions. It’s all that emotional element of data use, it’s important but you don’t pay that much attention to it”. (Expert 12) |

| Knowledge and skills | Data literacy competencies and broader skills (knowing how to collaborate, being critical, reflective mindset) impacting participants’ DBDM and involvement in the PLN. | “So thinking about using data beyond technical skills and beyond numerical data, like the descriptive data pictures, words and images. Think more about: ‘How sure am I? How systematic, how representative, how fit for purpose, is this a reasonable way to use it’? A reasonable way to use it, what I would almost call the mindset of data literacy, to demystify it and make it less scary because initially it’s literally just going to be all they’re going to see is their preconceptions, that it’s technical work”. (Expert 7) |

| Interpersonal skills and dispositions | Characteristics influencing the interactions between participants in the PLN, such as trust and willingness to share. | “I think in a learning network you have to build up trust, galvanize trust and you have a facilitator having access to processes to help people get to know each other quite quickly”. (Expert 14) |

| Activities | ||

| Collaboration | Discusses collaborative practices among participants, both within their daily practice (PLC, data team, …) and beyond in the PLN. Includes the type of collaboration and collaboration activities, where individuals share a common goal and achieve it by engaging collectively in the DBDM cycle. | “It needs to be deep, so it needs to be more like a kind of superficial sharing of ideas (…) you develop a new idea or a new program and you are together trying it out, seeing if it works, giving feedback, the next person trying it out, giving feedback. So, it’s a truly collaborative system of engagement, co-construction and there has to be trust, there has to be a willingness to expose one’s weaknesses, there has to be a willingness to accept and take on board new ideas, it’s a very deep form of collaboration” (Expert 14) |

| Co-operation | Discusses collaborative practices among participants, both within their daily practice (PLC, data team, …) and beyond in the PLN. Includes activities where individuals engage interactively with others to achieve their own specific DBDM goals. | “In the present mode, we always have peer counseling between the teachers: how to solve the problem, what are the best interventions, how can we find the adaptable data collection tools, …” (Expert 11) |

| Reflective inquiry | Activities stimulating to critically reflect on participant’s practice, such as learning conversations, reflective dialogue, deprivatization of practice, … | “a teacher’s willingness to move their egos aside and have open discussion around the data, plus, and this is one of my big issues. To think broadly of what data is, that data is not just test results, that you opened your statement with about assessments, and the creation of an assessment, to think much more broadly about what data can help a teacher think about what, how a student is”. (Expert 6) |

| Cognitive conflict * | Activities within the PLN that involve challenging existing beliefs or assumptions based on new data insights. | “People have ideas that they are really convinced of and then the data suddenly say something else. And then, starting the conversation about that, what do you think and what do the data say, that’s very important. In the literature, this is called cognitive conflict. And our coaches who really know how to discuss that cognitive conflict in the team and eventually work through it (…) so those are some coaching skills that are important”. (Expert 1) |

| Intentional interruption * | The deliberate efforts within the PLN to disrupt routine thinking or standard operational procedures with the aim of fostering innovation and improvement in DBDM practices. | “you have to realize that the most value you can get from being with other people is the extent to which they will stress test your ideas. In other words, push you past where you can’t get on our own. We as humans have all of these cognitive biases that are designed to preserve and conserve what we already believe and know and do (…) it’s all about how you interrupt these mental shortcuts that are designed to keep practice and thinking in the same place. One of the best ways is for other people to help you do that. Most of us aren’t good at challenging ourselves, we need other people to challenge us”. (Expert 7) |

| Knowledge brokering | Addresses the inward such as knowledge traveling from within the PLN to people who are not involved (e.g., school team, district) and knowledge and expertise brought into the PLN. | “teachers coming from different schools and they work together and that process is facilitated by you know me or someone else. And then they got to be back into their schools and that’s where it gets tricky. And so, we hadn’t actually said at this point to teachers what they need to do when they go back, we kind of told them what seems to work and what doesn’t seem to work. And it was only later on, we began to study what happens when they go back to school and which approaches are more effective than others. And we kind of found, as you say, if they set up a PLC within their schools, that seems to be a lot effective because they kind of like copying the processes they went through in the network back in their school” (Expert 14) |

| Outward brokering, namely, training and capacity building. Involving activities stimulating training and professionalization in DBDM. | “So what we did initially in that training process, is we used a lot of social apprenticing. We explained it ‘This is what this graph means’ and then we worked through the big picture stuff and the individual school stuff, and then we also worked with the school to help them understand their data”. (Expert 4) | |

| Influencing factors | ||

| Tools | Tools that bring structure to the process of DBDM and PLN activities, such as role positions, worksheets, and reflective questions. | “We have a manual with the different steps and worksheets, but I must say, one school closely follows the manual and fills out all the worksheets, while another school does not. That’s really up to the school itself, these are all tools that you can use based on your needs” (Expert 1) |

| Vision and goals | The shared goal or focus of both the individual participants and the PLN (such as student learning, change in dropout rates, …). | “It’s very important to set goals, so you need to formulate a very concrete and measurable goal, which they find quite challenging. Yes, because then the question is, what is our goal? What is achievable given our population? What number do you put on it? And that leads to discussions that people find very interesting in hindsight because we also often hear them say, ‘Yes, we actually talk too little about the goals we aim for with our education’. So, that’s actually a nice additional benefit”. (Expert 1) |

| Autonomy | The balance between participants’ own goals and activities and those of the PLN. | “you have to be kind of very clear on how you set it up and you want to have teachers have some latitude in making decisions. What is our goal that we can set for the year, I would start it more organically, you’re a team, what are you working on, so you can kind of give them some latitude”. (Expert 12) |

| Context | ||

| Policy | The influence of governmental or institutional policies (e.g., school districts), both on DBDM and PLNs. | “There wasn’t any centralized support for capacity building. There was a lot of stuff available but I would say it varied in implementation and uptake. The ministry did create professional network centers. We’re organized in school division school boards mostly. They’re regional and so they cluster them together in a network and say: ‘Okay, you 6 boards you’re a professional network center’. They give us a structure and we had to figure out what the function was going to be in that structure”. (Expert 7) |

| School | ||

| Time and resources | The resources for DBDM and participating in a PLN (e.g., designated time, meeting spaces, technological resources). | “The better teams had a nice space for the team to work in, they had coffee ready, good facilities that showed them ‘we take this seriously, you are valued’. They also scheduled the entire year’s meetings in advance. If you say the team has to meet in the evening and then there’s no coffee left, it won’t work”. (Expert 2) |

| * Codes added during analysis. | ||

References