Abstract

This paper investigates how popular music lyrics over the past century have described the nature and dynamics of Anglo-American student experience in formal schooling contexts. Using data from a cross-section of music streaming service databases, we identified 131 popular songs whose lyrics specifically discuss dimensions of formal school experience, especially from a student perspective. After three rounds of inductive thematic textual analysis, 7 major themes with 28 associated sub-themes emerged. These themes include school environment, situated feelings about school, negative results of school, school and society, conformity, negative view of teachers and the sexualization of teachers. Based on the assumption that a song owes at least some of its popularity to the appeal and relatability of its lyrical content to its audience, we hope that an in-depth, thematic analysis of such lyrics will give educationalists new insight into Anglo-American school experience through the salient societal medium of popular music. We further hope that these lyrical themes will shed new light on the lived experiences of school-age students and thereby deepen educationalists’ understanding of student experiences, perceptions and dispositions toward school more generally.

1. Introduction

Sociologists, psychologists and even pediatricians have explored the dynamics of the relationship between popular music and adolescent, Anglo-American school experience, detailing its effects on schoolwork, behavior and psychological development [1]. One educationalist even described the relationship between school and popular music as “discursive”, highlighting the reciprocal dynamic between school experiences and popular music lyrics [2]. Further research in sociology has focused on how such lyrics characterize adolescent educational experiences within the context of early-20th-century American songs [3,4]. Sharing Ko’s position, we see music lyrics as a unique expression of societal perceptions of school experience [5]. Rather than approach an understanding of lived school experience from the perspective of controlled, experimental research, we assert that a rigorous, qualitative analysis of broadly shared cultural artifacts like popular song lyrics taps into the emic perspective of Anglo-American school-aged youth in a unique and valuable way. Building upon this foundational idea, the purpose of this study is to explore the relationship between Anglo-American popular music lyrics specifically about school and the dynamics of the educational contexts and experiences these lyrics describe. We do so by systematically collecting 131 popular songs that specifically focus on school experiences, submitting their lyrics to rigorous textual analysis. We finally present the resulting themes in the context of various bodies of scholarly research with which they come in contact, including psychology, school policy, sociology and education law. In short, this study asks the question, “What do the lyrics of Anglo-American popular music suggest about the nature and dynamics of school experience?” We recognize that this music draws audiences from a vast variety of social, cultural, linguistic and economic backgrounds. However, we justify drawing links between these song lyrics and socio-cultural traditions of Anglo-American school experience because their lyricists repeatedly state in interviews that they draw upon their own school experiences to write these lyrics in the first place. The bodies of literature that contribute to our discussion of themes from these song lyrics describe the context of schooling with which each of these songwriters has direct, lived experience. Butchart and Cooper similarly emphasize this point, arguing that “unlike the minstrels of old, modern rock musicians, although no longer students when they write or perform their music, have been in the classroom. Their medieval counterparts had never been aristocrats” [4] (p. 272). Musicians have been generally lauded for the connection of their music to the perceptions and experiences of their audience. The link between popular musicians’ song lyrics about school and the school experiences that at least in part inspired them is particularly powerful because of the direct experience these artists have with the very schools encountered by their listeners. Seen in this light, we assert that a thorough examination of popular song lyrics will provide powerful and perhaps even unique insights into lived student schooling experiences. We further contend that situating these fresh perspectives against the backdrop of relevant bodies of literature will in turn provide further unique insight into the lived student school experience that such literature in isolation may not elucidate with the same richness and depth.

It is important to note here, however, that the complexity and multiplicity of meaning in such a rich context as song lyrics cannot be understated. “Lyrics”, wrote Pettijon and Sacco, “are an important form of communication, serving a variety of purposes as documented in the psychology of language literature” [6] (p. 298). This is particularly true in the case of popular music lyrics, which Booth called “text-intensive” [7] (p. 188). According to Frith, “three things are heard at once when listening to the lyrics of pop songs: words (as a ‘source of semantic meaning’), rhetoric (‘words being used in a special, musical way’), and voices (‘human tones’ as ‘signs of persons and personality’)” [8] (p. 39) (see also [9] (p. 159)). Not only are popular music texts fraught with multitudes of meaning in the nuances of their performance, but the act of listening itself adds further layers of complexity, as well. Speaking specifically to this complexity in the context of the meaning of popular song lyrics, Fornäs wrote the following:

“Listening practices are not simple reproduction of encoded meanings, but a highly productive form of consumption, producing impressions, emotions, social relations, and meaning. As the most distinctive way to use cultural phenomena or consume cultural commodities, interpretation is an active creation of meaning, resulting from the contextualized encounter between human subjects and texts”.[8] (p. 40)

Seen in this light, the performance and interpretation of popular song lyrics involve not only an encounter between human participants and texts, but an additional encounter between performers and audiences mediated by the text itself. To this is added (in this context) the unique reciprocality of the performers’ and audience’s collective school experiences upon which both draw to bring meaning to these lyrics and which, in turn, inform future school experiences, as well. Amidst this complexity, however, the analyses that follow adopt Pettijon and Sacco’s assertion concerning the role and function of popular song lyrics. “Lyrics”, they wrote rather succinctly, simply “tell stories and communicate with audiences in a manner similar to how people have conversations with each other” [6]. It is the humanness of this conversationality that forms the foundation upon which we build the analyses that follow.

2. Literature

In the section that follows, we outline literature that contributes to an understanding of the relationship between popular music lyrics and school experience in Anglo-American contexts. We begin by highlighting research regarding the capacity of music to reflect societal perspectives and then detail the role that popular music has played within this frame. We continue in noting research about music lyrics’ influence on listeners more broadly conceived. We then focus more closely on music’s role in defining perceptions of education, detailing research on lyrics about the school experience. We conclude this review of literature by clarifying our approach in the present study as situated within the contexts of the research threads theretofore outlined.

Anthropological and psychological research has suggested that the music of a society can provide significant insights regarding that society’s opinions and perspectives [10,11,12]. For the purpose of this study, we have chosen to highlight the lyrical content of music that is considered prevalent in society—in other words, “popular” or “pop music”, terms which we will use interchangeably hereafter. Importantly, while our analysis is primarily textual, we do not claim that song lyrics can or should be analyzed independently of the musical contexts in which they are presented. Therefore, we include relevant details about the genre and musical presentation of lyrics in our analysis.

The history and conception of popular music is a topic hotly debated among researchers in fields from economics to sociology. Sociologists point to technological and economic advances of the fifties and sixties as a turning point in the proliferation and consumption of smaller samples of songs on an increasingly larger scale [11,13]. As of 2023, the Global Web Index of online music streaming statistics found that North Americans listen to an average of 75 min of music a day [14]. The advent of smartphones and streaming technology has further facilitated the capacity of new music to reach broader audiences more quickly [15]. In light of these data, the relationship between popular music and those who form its audience is a strong one. We submit that a concomitantly strong relationship exists between popular music lyrics and those who form their audience, as well.

With regard to the creation and popularized consumption of pop music, Dolfsma explained that individuals utilize this medium in an effort to show “who they are and who they want to be” [11] (p. 1020). Furthermore, Butchart and Cooper point to the connection between popular music and adolescence: “Popular music, a principal artifact of youth culture, gives voice to a broad range of concerns, values, and priorities of young people” [4] (p. 271). Dennis argued in favor of popular rap music specifically, saying, “listening to and creating rap music can be a healthy aspect of adolescence and young adulthood… [as it] can facilitate identity development, support emotional intelligence and provide a safe space for experimentation” [16] (p. 511). No matter the genre, it seems, popular music can be an important entryway to understanding the genre, it seems, popular music can be an important entryway to understanding the perspectives held by members of society, especially adolescents.

This relationship between music and society may also be considered reciprocal in that each influences the other. In other words, while societal perceptions are reflected in the music that society creates, on the other hand, music has the capacity to influence or determine those very perceptions, as well [17]. Researchers in medicine and social psychology have studied the power of popular music’s ability to influence various groups of individuals. For example, contemporary research in the field of social psychology has proposed a link between the type of music being played during shopping experiences and the buying habits of customers. Zander explained that “music has the ability to modify the impression that listeners of a radio commercial have of the product and endorser” [18] (p. 3). His study illustrated that music has the ability to convey information and sentiments to the consumer; spoken words unaccompanied by music, on the other hand, may lack this power [18]. Toldos et al. even discovered a specific correspondence between the language of a store’s background music and the purchasing tendencies of its customers [19]. This emphasizes the noteworthy influence of music lyrics on those who form their audience.

The language and lyrical content of popular music have been purported to influence not only buying habits, but lifestyle habits, as well. A 2009 medical study noted an “association between exposure to lyrics describing degrading sex in popular music and early sexual experience among adolescents” [20]. They furthered this claim by proposing evidence of a relationship between the level of an adolescent’s sexual activity and the severity of the sexual lyrical content being consumed [20]. Additionally, teens have been cited as ranking media second to sex education as a common source of information about sex [21]. However, when interviewed about the perceived effects of music, teens have also been quoted as expressing disbelief regarding the potential influence lyrical content can have over their lives [22,23]. While literature previously cited would seem to contradict the teens’ stance on the influence of music, author Leanord Meyer of “Emotion and Meaning in Music” stated the following:

Although the volume and intercultural character of this evidence compels us to believe that an emotional response to music does take place, it tells us almost nothing about the nature of the response or about the causal connection between the musical stimulus and the effective response it evokes in listeners.[24] (p. 6)

His argument here provides a significant backdrop to our discussion of the relationship between popular music lyrics and adolescent school experience. While we make no claim to any causal connection between the two, we together with Au acknowledge the reciprocal, even discursive relationship between them [2]. It is upon this assumption of the rich interconnectedness of music lyrics about school with the school contexts they describe that this article’s textual analysis rests.

The previously cited literature establishes the idea that pop music may both reflect and influence the perspectives of its listeners and thereby society as a whole. Several related bodies of social research rest their arguments on similar principles. Their work focuses on the “influencing” dimension of music, highlighting artists and their lyrics as sources of negativity with the power to adversely affect the listener [21,22,25,26]. Importantly, this inquiry engages with the idea that pop music both reflects and shapes societal perceptions of the thematic phenomena that their lyrics touch upon. In collecting these songs about school, we aim to elucidate and detail the rich contexts in which these lyrics were written and are encountered. Furthermore, we explore the relationship between the themes they portray and the nature of the school experience as described in relevant scholarly literature. Again, in none of these explorations do we intend to establish a causal link between these lyrics and the school experiences they describe. Furthermore, we acknowledge the complexity and nuance of the concept of meaning as it relates to song lyrics both performed and perceived. We will situate our positionality in relation to this complexity hereafter. We hope that our work may lead to further research regarding the “influencing” power of music about school.

More closely related to our research question, Butchart and Cooper analyzed 200 hit songs from 1900 to 1980. Their thematic analysis was limited to “(1) images of teachers, (2) images of the formal content and processes of schooling, and (3) images of the school as a community and the center of youth activity” [4] (p. 273). Their analysis led them to conclude the following: “popular song lyrics reveal that formal learning is consistently depicted as de-humanizing, irrelevant, alienating, laughable, isolating, and totally unworthy of any link with the Socratic tradition” [4] (p. 271). On the heels of Butchart and Cooper, Brehony published a similar paper with the intent to examine the dimensions of popular music as a reflection of the schooling experience. Though more philosophical in his pursuit, Brehony might agree with his predecessor’s conclusion: “In rock and pop”, he wrote, “as in popular culture, in general [school] tends to be represented negatively or its negative aspects are emphasised… such texts construct positions for their subjects which are antithetical to the regime of schooling” [3] (p. 132). Both Butchart and Cooper and Brehony have laid an important framework for collecting and analyzing pop songs that reference school experiences. We aim to build upon their work with (1) an increased sampling of songs from eras both past and present; (2) a detailed thematic analysis of all collected lyrical content; and (3) a connection between apparent themes and contemporary research in various areas of scholarship, including child development, psychology and education.

3. Method

The methodology for research in this area can vary greatly depending on the year in which the work was published and the era of music analyzed. Butchart and Cooper, for instance, investigated lyrics from popular songs about education from 1900 to 1980 by collecting 200 hit songs from over this time period that discussed school in various capacities [4]. Brehony narrowed his sampling down to songs that entered the British Hit Singles chart from 1952 to 1992. Among other methods, he conducted a keyword search on the internet and in record store catalogs using terms such as “school, teacher, and education” [3] (p. 114).

The definition of “popular music” has evolved greatly since the publication of these articles. In the past, a “hit” song might have received this label due to the amount of plays on the radio or vinyl and CD sales. The contemporary music landscape has since expanded to include online streams and views of music videos in the definition of a so-called “chart-topper”. In fact, the reigning name in music charts, the Billboard Top 100, has included views on platforms like Youtube and streams from sites such as Spotify in their counts since 2012 [27]. This digital music technology allows listeners to access millions of songs in one central location by paying for a subscription or listening with ads [15]. Consequently, it has transformed modern definitions of popular music to include songs that may be constantly played on demand, yet never physically acquired or requested.

In order to define and narrow the scope of our song selection, we first created specific parameters under which we might categorize songs as “popular”. Songs and artists that fall under this category either hold a numerated position on a chart of popular songs or can be linked to music video views or song streams with numbers above 1,000,000. We created our specifications with the purpose of utilizing popular music with lyrics referencing school from the beginnings of these metrics to the time of this paper’s writing. Within these parameters, our search spanned a period from 1947 to 2019. In regard to the lyrical content, we determined songs to be “about school” if they met one of three criteria. The song must make multiple references either to school as a learning institution, a teacher and their role in the classroom, or learning or receiving an education. Additionally, all songs considered for our sample must have discernible lyrics.

To select these songs, we conducted a keyword search over a cross-section of several musical databases. These databases included Apple Music, Spotify and Google Music, which have the capacity to search 100 million, 100 million and 40 million songs, respectively. Each of these streaming services contains a search engine that has the ability to populate song titles and song lyrics containing the searched term(s). We chose to search terms such as “school(s)”, “education”, “teacher(s)”, “class”, “graduation”, “learning”, “student(s)”, “pupil(s)” and “teach”. These musical streaming services provided us with not only modern song results, but songs made digital from past musical eras. We further searched by consulting similar research articles and song compilations previously made on the topic of education and popular music [3,4]. Importantly, we do not claim that the songs outlined in this paper represent an exhaustive sampling of popular music about the school experience. However, it is our purpose here to provide a representative sampling of such lyrics to add to existing literature on this subject from a perspective more thoroughly informed by contemporary music samples.

Furthermore, previous studies that have engaged in this kind of exploration of popular song lyrics have done so within a particular genre in isolation, for example, rap music [2]. One of the contributions of this paper is its investigation of popular music lyrics across eleven genres. Others have limited their analyses to single song releases from a unique geographic area outside the United Sates [3]. Furthermore, while salient studies of popular music lyrics about school have historically identified songs regardless of their popularity, the present study uses the additional, aforementioned criteria for popularity as a means of selecting song lyrics more likely to be representative of broadly shared, popular feelings about school.

Following established norms in the literature investigating popular song lyrics to do with schooling, our sampling method can best be described as both theoretical and based on purposive criteria. Due both to the limited reach of many pre-digital music albums as well as the proliferation of digital media today, “any sample” one scholar of popular music lyric analysis wrote, “must inevitably confront the issue of its lack of statistical representativeness [3] (p. 114). In light of this challenge to statistical representation and generalizability, we present the 131 songs we identified across three digital databases as a theoretical sample intended, again, not as exhaustive, but as representative of thematically significant trends in popular music across eleven genres. Importantly, while previous studies analyzing popular music lyrics to do with school have drawn from a substantial sampling of songs, the criteria whereby songs were selected have often gone largely unexplained [3,4]. One researcher explains that he relied upon his “own extensive memories of pop songs” as a primary criterion for his sampling and admitted that he excluded entire genres “including rap and hip-hop” simply because he thought them ill suited to his purposes [3]. Furthermore, such studies have not presented systematic textual analyses accompanied by relevant literature linking qualitative themes with contemporary issues in schooling like that which is presented in the discussion that follows.

Following an initial search for songs that met the aforementioned criteria for popularity and relevance to the subject of Anglo-American school experience, we engaged in established methods of inductive textual analysis [28,29]. Rather than finding an a priori theoretical framework to approach text, we operated organically and allowed the lyrical content to determine the overarching themes as was appropriate [30]. The primary analysis involved investigating each song’s lyrics and genre and the context of its release time and date.

These are not the only pieces of context in which a song’s lyrics derive meaning, however. Popular music sociologist and critic Simon Frith argues that it is not a lyric’s semantic qualities that establish the intention of a song. He believes, instead, that analyzing the vocal performance of a song and its rhetoric paints a more accurate picture of the nature of the song, the artists and their purposes [9]. Important as this dimension is, the “poetry and praxis” of the songwriting process may prove equally as valuable, as Astor and Negus assert in their response to Frith’s argument: “When taking these purposive creative processes into account, the lyrical content becomes an important part of the process of how songs are understood, evaluated and debated”. [31] (p. 2). When evaluating lyrical content versus musical performance, we concluded that the role of the songwriter took precedence for our particular purpose as we were attempting to search for thematic trends within their lyrical poetry, not the final musical product. This is not to diminish or disregard the multifaceted dimensions of musical rhetoric that enrich more holistic analyses of any song. Rather, we situate our contribution to this literature as a thematic analysis focused primarily, though not exclusively, on song lyrics within the broader context of the multifaced rhetorical dimensions that inform their meaning.

Directly following this analysis, we returned to the lyrics and selected the portions of prose that exhibited salient messages about school, education, students or teachers. During our secondary analysis of the selected prose, we began to group lyrics with similar themes and ideas about the schooling experience. As we moved to consolidate our created themes during our tertiary analysis, we decided to categorize them under 7 major themes with 28 specific sub-themes in total. Finally, we searched relevant literature to situate each theme within the context of pertinent thinking related to the dimensions and dynamics of the school experiences such lyrics touch upon. Due to the purpose of criterion sampling of these contextual samples, it is not within the scope of this study to conduct broad-level quantitative analyses linking particular themes to specific variables within the population. That being said, we do include with each theme an outline of certain composer characteristics as they relate to the theme. We recognize that the relationship between lyricist gender, sexuality, geographic place of origin and particular themes would add to this literature. While we provide thorough detail about these demographics, we do so to provide context to the themes presented. Future research in this area would benefit the literature but is beyond the scope of the present paper. Our thematic exposition remains within the bounds of the qualitative research structure in which it is presented. However, we recognize the value such quantitative data would provide to the literature and invite further research in this area in the future.

4. Results

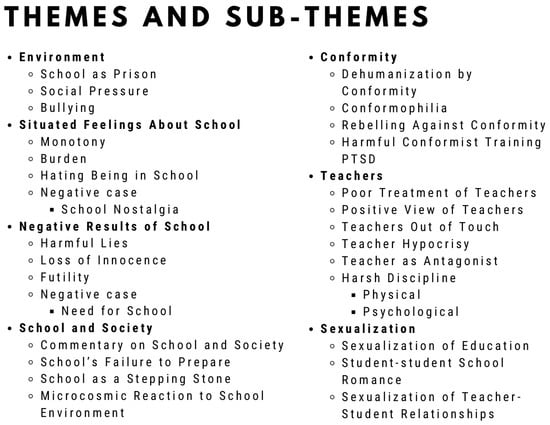

In this section, we outline the results of our textual analysis of popular song lyrics about school experiences as detailed previously. We begin with a general overview of the songs themselves by presenting data including their place of origin, the decades in which they were written, and the musical genres and subgenres that they represent. After this initial overview, we proceed to the main portion of our findings which examines each theme that resulted from our textual analysis. This section comprises seven general themes: school environment, situated feelings about school, negative results of school, school and society, conformity, negative view of teachers and the sexualization of teachers. These major themes are further broken down into a total of 28 sub-themes, the organization and distribution of which are outlined in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

An outline of the 7 major themes and 28 sub-themes as organized and discussed throughout this section.

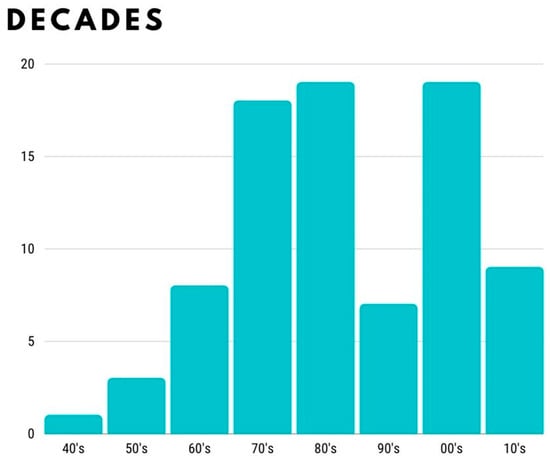

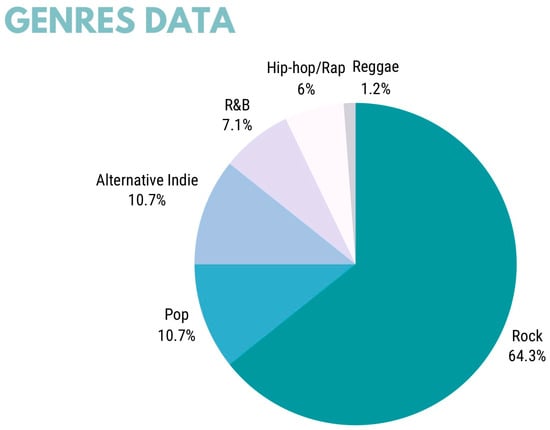

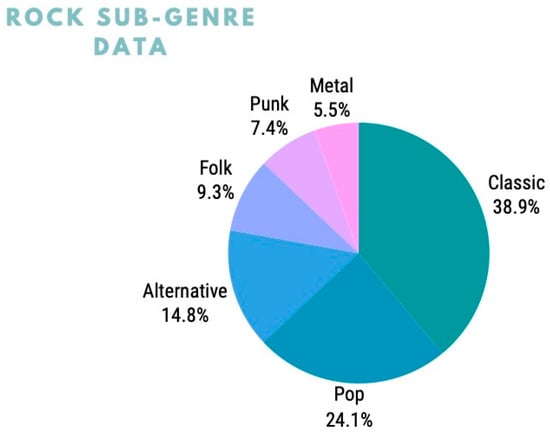

Our primary purpose in collecting these song lyrics was to subject them to various levels of thematic analysis. As an additional layer of analysis, we created multiple graphs to demonstrate the various decades and genres represented by our sampling. Figure 2 tracks the various decades from which our songs originate. With 84 songs in total, the seventies, eighties and two-thousands comprised the greatest number of songs with references to schooling. A significant drop occurred between the eighties and the nineties with 19 collected songs released from ’81 to 89 while only seven collected songs originated from ’90 to 99. While a deeper analysis of the trends represented in this graph is beyond the scope of this paper, we included these data in order to provide the reader with further background information about our sampling of songs, specifically the eras in which they were released. Additionally, we charted the various genres represented in our sample, as shown in Figure 3. The genre of each song was collected during the initial stage of research as listed on the streaming platform from which they were collected. More than half of the collected songs can be categorized as “Rock”. The next most common genres are “Pop” and “Alternative Indie”. Due to the overrepresentation of “Rock” in our genre data, we further contextualized this data point by graphing the subgenres of “Rock”, as shown in Figure 4. “Rock” or “Rock n’ Roll” is a multifaceted genre with roots in Jazz, Gospel and Blues music and more recent instantiations of “Metal Rock” or “Punk Rock” [32]. Therefore, we deemed it appropriate to include a breakdown of the data within the genre. A detailed analysis regarding the role of “Rock” music that makes reference to schooling is outlined in future sections, specifically “Rebellion Against Conformity”. It is important to note that the abundant use of the rock genre as a medium through which these lyrics are expressed has a significant impact on the nature of the themes they portray. At the beginning of each of the seven themes that follow, we also include three charts that describe the numerical spread of songs within each sub-theme according to genre, geographic location of origin and songwriter gender (see Figure 5, Figure 6, Figure 7, Figure 8, Figure 9, Figure 10 and Figure 11). These graphs provide essential context regarding the time periods and various genres of the collected songs outlined in this paper.

Figure 2.

The distribution of music analyzed in this study across decades from 1940 to 2019 according to date of publication.

Figure 3.

The distribution of music analyzed in this study across various genres.

Figure 4.

The distribution of music analyzed in this study within the Rock genre across its various subgenres.

4.1. Environment

The theme of school environment refers to the physical and social characteristics of the school environment itself. The first sub-theme is entitled “School as Prison”. Songs under this category make reference to the various similarities between schools and prisons both real and imagined. The following sub-theme is called “Social Pressure”. As the group schooling experience is social in nature, there are a variety of norms, cultures and consequences that students experience throughout their schooling journey. Songs with themes of “Social Pressure” discuss cliques, social hierarchies and related topics. The next sub-theme, “Bullying”, depicts physical, verbal and social bullying experienced by artists during their schooling.

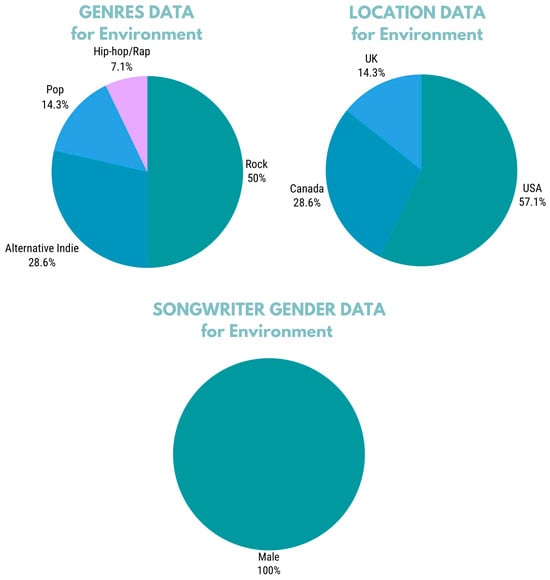

Figure 5.

Data outlining the distribution of songs specific to the theme “Environment” across various genres of music, geographic locations of origin and songwriter gender.

4.1.1. School as Prison

Comparing schools to prisons is a common theme found in the lyrics of many popular rock songs [33] (p. 229). Indie rock band Mother Mother describes the return to school as a return to a place of confinement: “Back in school, back in place/Back in school, back in chains/Back in school, back in my cage”. In an interview, Ryan Guldemond, founding member of Mother Mother, said, “Music… is something that I always want to feel like I’m further my education of, but I probably would rather not do that through school. School is a bunch of bullshit [34]”. In this case, associating “school” with other symbols of prison and even slavery suggests that their perception of the school experience is one of pain and restriction. The Dead Kennedys’ song “Life Sentence” draws this parallel as well, with its repetitive chorus, “It’s your life sentence/Life sentence/Life sentence/Life sentence”. They take the prison–school comparison one step further by saying that the years we spend inside the school are equivalent to a sentence of life in prison. Jello Biafra, Dead Kennedys’ lead singer and songwriter, builds on this comparison in interviews with Punk Cyborg and Punk News, referring to “long haired outlaws” as the “freaks of the school” in his own experience [35]. He further claims that “Part of the reason the schools are so crappy is because people are too greedy to pay the taxes necessary to maintain them properly and then they’re the first to… moan when their kids turn out so stupid and violent” [36]. These comparisons draw attention to the traumatic school environments students can experience. Negative attitudes about school can also invade other aspects of student life. According to an international study published in the Journal of Adolescence, students with this negative perception of school may be twice as likely to be involved in instances of bullying, a problem that compounds the already negative attitudes towards school these students may harbor [37] (p. 641).

4.1.2. Social Pressure

Another element of school environment is the creation and maintenance of social strata [38] (p. 217). Selective groups and cliques in school can be “socially counterproductive because they create hierarchies that alienate some students” [38] (p. 216). These feelings of alienation and peer pressure are expressed repeatedly in the lyrics for this theme. Describing their experience as musicians and students concurrently, a founding member of The Academy Is, Mike Carden, informed Alternative Press, “At the time, a lot of our friends weren’t taking these big chances. They were going to school and doing their normal thing, and everyone was frowning [at] us, going, ‘What are you doing?’” [39] This statement provides context for the lyrics of their song, “Paper Chase”, which paints a picture of the life of students excluded from the rest with their lyrics “We’re the cast outs with messed up friends who never did fit in/Don’t know where it ends”. Here we understand that, in their experience, once one is designated as an outcast, the label becomes permanent. To them, there is no upward mobility or hope for a change in the school environment, as their place in the school society, and perhaps in society thereafter, has been decided.

The band Bowling for Soup expands on this idea in their song “High School Never Ends” with the line “And the only thing that matters/Is climbing up that social ladder”. These lyrics suggest that the existence of a social hierarchy in school can become an all-consuming matter to students in school and beyond. Those on the top may become highly focused on maintaining their popularity, while those on the bottom can become obsessed with doing anything they can to rise in the ranks. Educational psychology supports this idea with research about adolescent peer groups in the school environment. In the book “Being Adolescent”, researchers found that “By high school, adolescents spend twice as much time with their peers as with their parents or other adults”. This makes their investment in friends and specific friend groups a priority in their lives [40]. Schools and classrooms are “inherently social places”, and the making of friends is expected to occur [41] (p. 101). However, contemporary research taken together with these lyrics indicates that when peer groups become toxic, students’ motivation and engagement in school decrease [41] (p. 106).

4.1.3. Bullying

Contemporary education research identifies three types of bullying: physical, verbal and social [42] (p. 368). It is noteworthy that this theme’s lyrics identify and specifically mention these three categories. In the song, “Playground”, XTC describes an instance of physical bullying in terms of students experiencing student-inflicted physical violence at school. They sing, “Marked by the masters and bruised by the bullies in the/Playground (it’s a playground)”. In “Grade 9”, the Barenaked Ladies identify name-calling as another specific manifestation of bullying that corresponds with the verbal category mentioned above: “They called me chicken legs, they called me four-eyes/They called me fatso, they called me buckwheat”. That the authors of these lyrics remembered these cruel, body-specific nicknames well after their time in school hints at the long-lasting, detrimental effect of verbal bullying on students. My Chemical Romance’s angsty punk-pop hit, “Teenagers”, emphasizes that bullying often comes from those at the top of fluid adolescent social hierarchies. They sing, “Maybe they’ll leave you alone, but not me/The boys and girls in the clique/The awful names that they stick”. In this case, those with social status seem able to, by virtue of that status, label others as inferior so effectively as to convince them of the truthfulness of that label for years to come. Giving further context to these lyrics, when interviewed by New Musical Express about his high school experience, My Chemical Romance lead vocalist and songwriter Gerard Way shared, “The only thing I learnt in high school is that people are very violent and territorial” [43]. As an instantiation of just such violence and territoriality described by Way, bullying in its many forms can have a devastating negative impact on those who are targeted. It can create school avoidance and fear of school in students, which can lead to stunted social, emotional and academic development [44] (p. 371).

4.2. Situated Feelings about School

Songs in this category communicate artists’ sentiments about the reality of being a student situated in a schooling environment. The first sub-theme, “Monotony”, outlines feelings of boredom or tedious situations in which artists found themselves during their time in school. The next sub-theme, Burden, refers to the various ways in which the lyrics describe school as an unwanted responsibility that impedes true learning or the authentic living of their lives. The following sub-theme, “Hating Being in School”, includes feelings of resentment and hatred when artists describe their school experiences. The final sub-theme, “Nostalgia”, is a positive–negative case in which artists express feelings of nostalgia regarding their time in school.

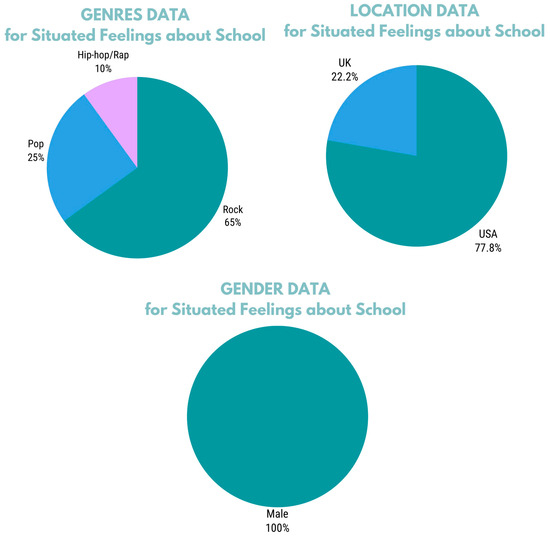

Figure 6.

Data outlining the distribution of songs specific to the theme “Situated Feelings About School” across various genres of music, geographic locations of origin and songwriter gender.

4.2.1. Monotony

Boredom in the classroom affects a student’s achievement, motivation and personal well-being at school [45] (p. 22). Importantly, the lyrics collected for this theme argue that school, as an institution, is plagued by such monotony. The band Nirvana, poster-child of rebellious teen anthems, uses repetition as a device to impress upon the listener the tedious nature of school. In their aptly named song, “School”, they sing “No recess/No recess/No recess/You’re in high school again/You’re in high school again/You’re in high school again/You’re in high school again/You’re in high school again/You’re in high school again/You’re in high school again”. Perhaps in part because of his perception of school as monotonous, Kurt Cobain shared in a 1993 interview that in high school he “…felt so different and so crazy that people just left me alone… [he] always felt that they would vote [him] ‘Most Likely to Kill Everyone at a High School Dance.’” [46]. Nirvana often expressed feelings of rejection and frustration at school with songs like “School”, and even the iconic “Smells Like Teen Spirit”. Listeners and fans seemed to share these sentiments as their national sales reached over 30 million at their peak [47].

Apathy in the face of school boredom is echoed in many British rock songs, as well. “Baggy Trousers” by Madness states, “But at the time it seemed so bad/Trying different ways/To make a difference to the days”. English icon Elton John’s “Teacher I Need You” adds to the discourse with his lyrics “So I’m sitting in the classroom/I’m looking like a zombie/I’m waiting for the bell to ring”. These one-time students turned musicians, it seems, use music as an outlet to vent about the lack of engagement they felt in the midst of classroom tedium. Key studies in educational psychology have attempted to address the problem of boredom by pinpointing what increases engagement in the classroom [48,49,50]. Few, however, explicitly mention that students continue to experience feelings of boredom and apathy at school despite interventions to address the issue [51]. It is important to note that in the aforementioned studies, “engagement” is offered as the solution to boredom. Inciting classroom engagement places the onus of excitement for school and participation on the students and teachers, rather than questioning the schooling system as a whole as many of these lyrics do.

4.2.2. Burden

According to an international survey recently conducted by the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), 66% of students feel stressed about receiving poor grades, with 55% of these students feeling anxious about academic endeavors, even if they are well prepared [52] (p. 104). The academic stress felt by many students can turn school into a burden, as suggested in the lyrics collected for this theme. “Go Forth and Die” by heavy-metal band Deathklok is a particularly acrimonious song that illuminates the burden that school was for them. They sing, “Now you’re sad and frightened/Want to go and hide/Maybe get your masters/Eight more years inside/Dream of your own murder/Strangled by the IVY/Drown in student loans”. In this frame, school as an institution seems almost meant to overwhelm and ensnare. They view their education not solely as a source of fear and sadness, but inherently designed to trap students into a seemingly infinite loop of stressful studies, in this case, the pursuit of higher education.

The eighties rock band Twisted Sister has a similar song titled “Be Chrool to Your Scuel”, parodying the Beach Boys’ more sincere single, “Be True to Your School”. The lyrics read, “Well, I don’t think I’ll make it through another day, it’s eight o’clock and all ain’t well/My brain hurts so much it’s startin’ to decay and I’m livin’ in my private hell”. The Twisted Sisters take a well-known song about the love of school and use it to highlight the stress it caused. In their case, a place that should have encouraged growth and discovery became a “private hell”. Twisted Sister’s Dee Snider illustrated some elements of his private hell in a 2023 interview with 94.5 KATS-FM. “I was just one of the… outcasts”, he said. “Weird big dude that was just trying not to get my ass kicked in school” [53]. We see the idea of school as a burden expressed in even the earliest rock-and-roll songs. Father of rock-and-roll Chuck Berry sings in his song “School Days”, “Soon as three o’clock rolls around/You finally lay your burden down/Close up your books, get out of your seat”. Though not riddled with the same bitterness as the previous two songs, we still see that, for Berry, a release from school signifies a release from affliction. When students feel burdened by school, their educational experience may become tainted by stress. Such students can not only face setbacks in their academic achievements but struggle with their mental and physical health, as well [54] (p. 5).

4.2.3. Hating Being in School

Another theme prevalent among the songs collected is students wanting to avoid school entirely. The lyrics for this theme speak to frustrated students whose yearning for a release from school can often turn into resentment directed towards the institution as a whole. Alice Cooper’s “School’s Out” dominated the airwaves in 1972, spending thirteen weeks on the charts [55]. First-time listeners might dismiss the song as a simple tribute to summer break. However, upon further review, the lyrics speak to a deep-seated resentment towards school. The chorus reads, “School’s out for summer/School’s out forever/School’s been blown to pieces”. Not only are they rejoicing in the start of a vacation from school, but they suggest that the institution be completely destroyed. Rapper Kanye West shares this animosity towards school on his debut studio album, The College Dropout, the first of his four education-themed albums. In the song “School Spirit” he raps, “Back to school and I hate it there, I hate it there/Everything I want I gotta wait a year, I wait a year”. West seems to express his frustration here that, for him, school is a place of misery and little gratification. He clarifies one reason for this in a 2005 interview with Fiona Apple. “With school, I just didn’t really want to be there” he explains. “I was like, ‘How do these credits apply to what I want to do in my life?” [56]. Many students feel similarly to Cooper and West. As a result, the start of the school year can be seen as something to dread. In some US states, school truancy can reach as high as 20% according to the National Center for School Engagement [57] (p. 50). While truancy can be the consequence of a variety of other factors in a student’s life [58], these lyrics suggest that there may be a significant number of students who simply detest the school experience and do not attend for that reason.

4.2.4. Positive–Negative Case, Nostalgia

As a negative case, some lyrics collected for this theme speak of nostalgic feelings for school, a slight contrast to the bitterness expressed in previous lyrics. Alt-rock band The White Stripes sings in their song, “We’re Going to Be Friends”, “Tonight I’ll dream while I’m in bed/When silly thoughts go through my head/About the bugs and alphabet/And when I wake tomorrow I’ll bet/That you and I will walk together again/I can tell that we are gonna be friends”. The song recounts the excitement of making childhood friends in school. The band The Kinks share their nostalgic sentiments towards school in the song “The Last Assembly” where they sing, “As I walked to the last assembly, /There were tears in the back of my eyes, /And I saw all my friends all around me, /They were there to wish me goodbye”.

It is noteworthy that the positivity expressed in both of these songs primarily concerns the friends made during school, rather than the things they learned or school as an institution. Indeed, The White Stripes’ composer, Jack White, expressed to Publishers Weekly his initial concern that “people might not understand the song for what it was supposed to be. The world I worked in at the time was very cynical so I thought they would take it as ironic”. He further emphasized that it is “the fantasy of friendship” in the song which he hopes will connect with listeners [59]. Lyrics inspired by a passion for learning and education are simply not mentioned in the collected songs. This seems a glaring absence in subject matter for songs referring to school. Certainly, the function of pop music as a mode of intense emotional communication that is predicted to resonate with listeners plays a role in this phenomenon. Nonetheless, the previously mentioned artists having negative experiences in school and then predicting that their listeners would be able to relate speaks to the public’s view of education as well as the educational system itself. In summary, the lyrics collected for this overarching theme suggest that the prevailing sentiments regarding the school experience are those of boredom and misery; while some songs express an appreciation for the relationships made with peers, this appreciation is not extended to the school experience itself.

4.3. Negative Results of School

The songs in this category contain negative consequences or circumstances that lyricists attribute to school experiences. The first sub-theme, “Harmful Lies”, refers to the artists’ position that they were promised a positive, supportive education and instead left school with the opposite. Some feel unprepared for life in the “real world”, while others feel that the content of their education was false or misleading. The following sub-theme, “Loss of Innocence”, details the harsh realities artists felt burdened with, rather than protected from, during their time in school. Using at times plain and frank language, they fault the adults and officials of their schools with this premature maturation. Subsequently, within the sub-theme, “Futility”, artists express their frustration that though they may have expended effort during their learning, they have no positive results to show; ergo, schooling as a whole seemed futile in their view. Like the previous major theme, this section includes a positive–negative case: “Need for School”. Artists in this section urge their listeners to make education a priority due to the “important” effects it has had in their lives, but do so by casting school in a dire and begrudgingly necessary light as opposed to highlighting any uplifting dimensions of receiving an education. Without it, they write, death and misery might have been their only options.

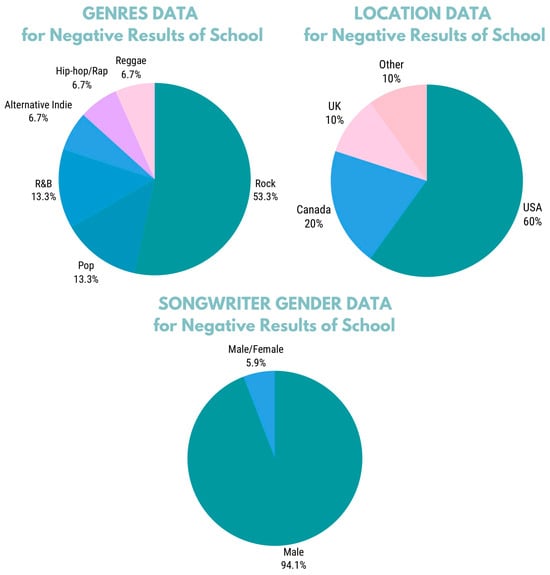

Figure 7.

Data outlining the distribution of songs specific to the theme “Negative Results of School” across various genres of music, geographic locations of origin and songwriter gender.

4.3.1. Harmful Lies

The benefits and advantages of “getting an education” have been consistently impressed upon contemporary Western societies [60]. In spite of widely supported public campaigns for education, lyrics for this theme suggest that students can leave school feeling dissatisfied and lied to. For singer-songwriter John Mayer, the lie told to him was that there is a “real world” beyond that of school. In his song “No Such Thing”, he sings, “I want to run through the halls of my high school/I want to scream at the/Top of my lungs/I just found out there’s no such thing as the real world/Just a lie you’ve got to rise above”. Punk-rock band My Chemical Romance adds to the discussion by alleging that school not only taught them lies but used these lies against the students as a tool of oppression. Their song, “Teenagers”, makes this point with the lines “They’re gonna clean up your looks/With all the lies in the books”. From an entirely disparate genre, reggae singer Peter Tosh wrote his song “You Can’t Blame the Youths” about the deception he felt in school, as well. Here, Tosh asserts that such “lies” extended beyond life and career advice into the very content taught in classrooms. He sings, “You teach the youth about Christopher Columbus/And you said he was a very great man/You teach the youth about Marco Polo/And you said he was a very great man… All these great men were doin’/Robbin’, rapin’, kidnappin’ and killin’”. Whether referring to the way history is taught or the way the world works, across time and genres, these musicians have turned to music to express their frustration with the falsehoods and half-truths they felt were taught to them in school.

4.3.2. Loss of Innocence

Another negative outcome of school, as indicated by the lyrics of this theme, is a loss of innocence on the part of students. My Chemical Romance’s “Teenagers” comments on the subject with the lines “They’re gonna give you a smirk/’Cause they got methods of keeping you clean/They’re gonna rip up your heads/Your aspirations to shreds”. The methods of discipline used by their school not only enforced conformity, but broke the students down to the point where they did not want to pursue their dreams anymore, thereby losing their innocence. “The Logical Song” by Supertramp specifically highlights the juxtaposition of the band’s initial optimistic disposition towards their future as students and their eventual shift to hopelessness and cynicism by the end of their schooling. They sing, “When I was young, it seemed that life was so wonderful/A miracle, oh it was beautiful, magical…/But then they send me away to teach me how to be sensible/Logical, oh responsible, practical/And they showed me a world where I could be so dependable/Oh clinical, oh intellectual, cynical”. Discussing this song with Classic Rock Magazine in 2016, songwriter Roger Hodgson explained, “We go from the innocence and wonder of childhood to the confusion of adolescence, and that often ends up in disillusionment in adulthood. And many of us spend our lives trying to get back to that innocence” [61].

A feeling of clinical cynicism is mirrored in Andrew Bird’s “The Measuring Cups”. He takes this sentiment a step further by adding that school not only took his innocence, but attempted to compartmentalize his issues by labeling him as troubled. He writes, “Come to the front of the class and we’ll measure your brain/We’ll give you a complex and we’ll give it a name”. These songs touch upon the conflict felt by students when they were told obedience and conformity were of higher value than individual expression and the pursuit of dreams, leaving them feeling jaded and labeled as difficult. This labeling of students often causes more harm than good. Contemporary research argues that labeling students is a “Band-Aid” solution to the issues students actually face and that the “replacement [of labels] does not reflect any substantive change in thinking and behavior” [62] (p. 239). Instead of being offered substantive assistance and support in their aspirations, these lyrics tell of students who feel betrayed by an institution whose intended purpose is to nurture, rather than torture, as these lyrics have suggested.

4.3.3. Futility

In a survey of eighty high-school dropouts, many spoke about a sense of futility when reflecting on their school experience [63]. According to the study, these students “talked about not seeing the value of school, not being able to equate efforts with accomplishments… They were unable to link their educational journeys with their futures” [63] (p. 33). The disconnect between student effort and subsequent accomplishments in school is also a theme of multiple songs collected for this section. Hall and Oates sing about this inequality in their song “Adult Education”: “Memories that you won’t remember/So you got a little education (huh, huh)/And a lot of dedication”. Seventies southern-rock band 38 Special also shares their frustrating school experience in the song “Teacher, Teacher”. They sing, “So the years go on and on, but nothing’s lost or won/And what you learned is soon forgotten/They take the best years of your life, /Try to tell you wrong from right, /But you walk away with nothing”.

The band Barenaked Ladies takes the concept of the futility of school further with the lyric “First day of school and I’m already failing” from their song Grade 9. Here, they not only claim that their academic efforts are useless, but they imply that this feeling is intrinsic to (and perhaps even an inescapable part of) school experience. Their suggested remedy is to not try at school in the first place as no amount or type of effort could meet the unrealistic standards set by school officials. In the face of this apparent unfairness, these songs advise students to disengage from school. Recent research in educational psychology suggests that this kind of low-quality school engagement can lead to low participation, poor attendance and, as mentioned by the students in the aforementioned survey, even a student’s decision to drop out of school altogether [63,64].

4.3.4. Positive–Negative Case, Need for School

As a negative case, a few lyrics for this theme refer to school as essential to one’s future success, rather than manipulative and useless as the other songs might suggest. James Brown’s “Don’t Be a Dropout” argues that school is necessary not only for economic progress, but for life itself. The song details the life of a former high school drop-out and the consequences he faced by virtue of his decision to leave school. The chorus repeats the moral of the song, “Without an education/You might as well be dead… What do you say?/Without an education/You might as well be dead”. Released 10 years prior to “Don’t Be a Dropout”, Chuck Berry’s “School Days’’ also references a similar feeling of desperation to obtain an education. He sings, “The teacher is teachin’ the Golden Rule/American history and practical math/You studyin’ hard and hopin’ to pass”. It is important to note, however, that Berry does refer to school as a “burden” later in this same song. Indeed, both he and Brown highlight this pressure that they felt, as African American men in the 1950s and 1960s, to pass their classes and obtain an education. Their lyrics conveyed a belief that finishing school was essential to progressing in life.

Brown further declared to Dimitri Ehrlich of Interview Magazine in 1990, “Education is a must. I want a mandatory law that each young kid must have a high school education” [65]. A report entitled “Changes in the Labor Market for Black Americans”, from 1973, affirms this opinion. During this ten-year span between the release of the two songs, there was a ten percent increase in both the years spent in school and employment rate of Black men [66]. We see Brown and Berry’s attitudes towards school, as expressed in classic rock and soul songs, become less popular over time, especially after the advent of rap music. Among the many motives that led African American men to rap music was to express a lack of faith in the educational system as music styles and attitudes changed. In the following theme, School and Society, prolific African American rap artists like Kanye West and Lauryn Hill articulate a more jaded and nuanced message about school, in stark contrast to the endorsement of school given by some of their artistic predecessors.

4.4. School and Society

The fourth major theme we discovered involved the artists’ tendency to comment on the role of education in culture. Our first sub-theme, “Commentary on School and Society”, describes how certain school-age issues they thought would be unlearned or resolved during their journey in education have only followed and plagued them, and society at large, into adulthood. The next sub-theme, “School’s Failure to Prepare”, points to a shared sentiment among various artists that upon leaving school and entering adulthood and the workforce, these individuals found themselves overwhelmed and underprepared. Many share jaded references to unmet expectations and useless knowledge supplied by their schooling. The lyrics in the following sub-theme, “School as a Stepping Stone”, describe education as merely an end to other means, instead of a formative experience of youth. Artists of these songs seem eager to move past the experience of school as fast as possible and on to, in their eyes, more consequential endeavors. The final sub-theme, “Microcosmic Reaction to School Environment”, describes various mental issues and illnesses that they attribute to their time in school.

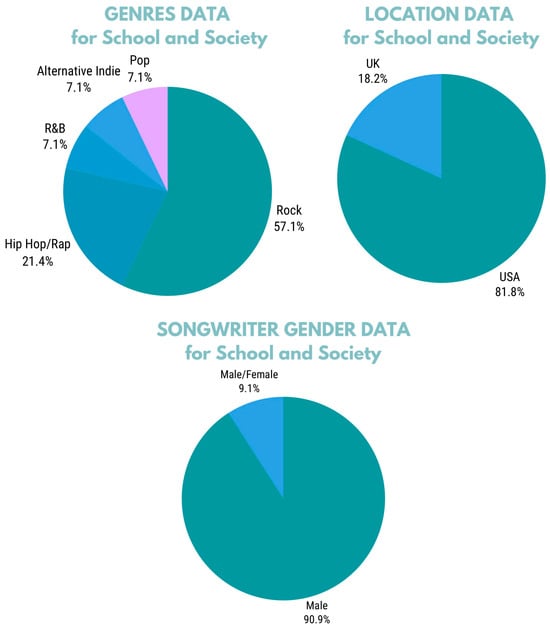

Figure 8.

Data outlining the distribution of songs specific to the theme “School and Society” across various genres of music, geographic locations of origin and songwriter gender.

4.4.1. Commentary on School and Society

The songs collected for this theme discuss how various elements of school experience seem to permeate society at large. Van Halen’s “Fools” points out that societal expectations for educated adults include the ability to handle life with a sense of maturity, a quality that their school-aged counterparts supposedly lack. Instead, the band has exited school and discovered that the social dynamics in play during their time there have endured well into adulthood. They sing, “Why behave in public/If you’re living on a playground?/It makes me blue/Fools, I live with fools”. Band member Alex Van Halen expanded this perspective in 1980 during an interview with Marc Allan, highlighting the similarity in immaturity and violence at sporting events regardless of participant age. “You ever seen a European football game?” he asks. “The fans in there, they’re fanatical, even if their, if their team loses they get pissed and they beat up on the other side. You know, look at the high school games, look at the violence that goes on there? And that’s when they’re still stone-cold sober” [67].

Pink Floyd likewise suggests that elements of school permeate greater societal norms. In their song “One of the Few”, they allege that the educational system functions properly for only a select group of people. When these select few decide what to do with their lives, they end up working for the very system that elevated them in the first place. The lyrics read, “When you’re one of the few,/To land on your feet./What do you do to make ends meet?/Teach”. These lyrics suggest that issues inherent to the schooling system do not simply bleed into society beyond the walls of the schoolhouse, but become a self-perpetuating cycle of dysfunction.

Though Van Halen and Pink Floyd are criticizing disparate aspects of school, they present important lines of thought to consider when evaluating the current educational system. From this perspective, school may not be instilling the passion for learning and cooperation in students that it intends. Instead, it allows ignorance and immaturity to fester and operates only for those who know how to work the system. The band Bowling for Soup perhaps encapsulates this issue most succinctly in their song “High School Never Ends”. Throughout the song they sing of petty worries that plagued their high school society that in turn follow them almost unbidden into adulthood. They sing, “And then when you graduate/You take a look around and you say, “Hey, wait!”/This is the same as where I just came from/I thought it was over, oh, that’s just great/The whole damned world is just as obsessed/With who’s the best-dressed and who’s having sex”. These bands have found that instead of leaving school with an enduring appreciation for learning and a sense of comradery with their peers, the same issues they thought simply inherent to the school system permeate society at large, leaving them embittered and resentful of their educational experience.

4.4.2. School’s Failure to Prepare

After the number of employed and graduated Black Americans boomed in the 1950s–1960s, the following thirty years marked a sharp decline in both of these rates. The employment rate of Black men fell from 73.2% in 1960 to 64.3% by 2000, while their incarceration rate rose by 1.3% [66]. The employment boom of the fifties and sixties may have contributed to Black musicians encouraging youth to stay in school. In a similar vein, it is possible that the decline in employment rates that followed motivated prominent Black musicians in later years to express their frustration with the educational system and encourage students to find success elsewhere. Kanye West, a college dropout himself, centered his first three studio albums on education. These albums were all a success in their own right, each going 4x platinum according to the RIAA [47].

His third album, “Graduation”, peaked at number one on the US Billboard music chart, spending 185 weeks on the charts. The school-related content in his early songs is telling of West’s attitude towards education. In the song “School Spirit” from the album “The College Dropout”, he sings, “Told ’em I finished school, and I started my own business/They say, ‘Oh you graduated?’/No, I decided I was finished…/This n-a graduated at the top of my class./I went to Cheesecake, he was a m-g waiter there”. He expands on this idea of the fruitlessness of school in his song “Good Morning” from the album “Graduation”. He sings, “Scared-to-face-the-world complacent career student/Some people graduate, but we still stupid/…/Okay, look up now, they done stole your streetness/After all of that, you receive this”. Not only does West deride the school system itself, but he expresses a certain disdain for those who become caught up in the system, whether or not of their own volition. West values fearlessness and success, both of which he says he did not find in school. This quality of “streetness”, he claims, is something he found elsewhere.

The notion that the most useful learning happens outside the classroom, on the streets specifically, is also referenced in rapper Freddie Gibbs’ song “Education”. He sings, “Get free and stay sick/And that’s it/An education”. Gibbs was interviewed by Jesse Thorn in his podcast Bullseye in 2019. During this interview, Gibbs shares the naivety he carried out of high school as a result of not being prepared for life after secondary school. “I was ready for the world. You know? Make money and just start having things. I thought that, you know, once you become an adult you just start automatically having things, but that’s not [laughs]—that’s not the case!” [68]. Pop icon Beyoncé Knowles-Carter also sings about this concept in her song “Schoolin’ Life”: “Who needs a degree when you’re schoolin’ life?” The prevailing sentiment among these prominent twenty-first-century Black artists is that school, as an institution, fails to provide learning that is either relevant or helpful to them in life outside the classroom. For them, the learning that occurs in school is not only shallow and hollow, but robs them of unique qualities that they feel are necessary to thrive financially and creatively in their lives beyond school. Whether this attitude stems from negative experiences in their own schooling or role models who seemed to have succeeded without school, advice coming down the pipeline of pop music is that the educational system does not work for everyone.

4.4.3. School as a Stepping Stone

Over the past forty years of global education trends, a holistic approach to teaching has gained prominence for many classrooms across the world [69]. According to the International Handbook of Holistic Education, this teaching style centers on the “education of the whole child—mind, body, and spirit” [69] (p. 82). These lofty principles stand in stark contrast to the sour sentiments expressed towards school in the songs collected for this theme. In the song “Life Sentence” by the Dead Kennedys, the band sings, “It’s your senior year/All you care about is your career/It’s your life sentence”. Instead of leaving school feeling fulfilled and enriched, they have come to the end of their high school experience feeling only coerced into becoming a cog in the workforce. The song “Paper Chase” by The Academy Is paints the school experience as merely a diploma chase. They sing, “Graduate, paper chase/We’ll get out of this place”. They understand the socio-cultural implications of having a high school diploma. As the most commonly held credential in the United States, the high school diploma has become a signal of productivity to employers and college admission boards alike, hence the pressure to “chase paper” in school [70]. These bands’ educational experiences do not reflect a commitment to nurturing their “mind, body, and spirit” as per contemporary education’s focus on holistic learning. Instead, these lyrics seem to focus on the social pressure of a system they describe as hollow virtue-signaling that sadly represents all that became of their schooling legacy.

4.4.4. Microcosmic Reaction to School Environment

Songs for this theme address students’ emotional and behavioral issues that they believe are consequences of their school environment. In the band Hefner’s song, “The Day That Thatcher Dies”, they sing of a schoolyard bully: “And the playground taught her how to be cruel,/I talked politics and she called me a fool”. Bullying is an all-too-common occurrence in schools [71], but what Hefner proposes here is that cruelty is an inherent lesson that is learned at school. The band Screeching Weasel makes a similar assertion in their song, “I Was a High School Psychopath”. A psychopath is someone who “is an asocial, aggressive, highly impulsive person who feels little or no guilt and is unable to form lasting bonds of affection with other human beings” [72]. The lyrics here imply that school was what caused him to develop this deviant behavior. They sing, “I needed therapy/I was a high school psychopath/with an overload of energy/there was a teenage wasteland in my brain/from staying after school”. The various stages of adolescent development are hallmarked with emotional instability, largely a consequence of the physiological changes occurring during this time [73]. Instead of this musician receiving care and support for his emotional issues, he was forced to stay after school, a consequence that he felt compounded his self-diagnosed psychopathy. Screeching Weasel and Hefner both attribute their cruel habits and lack of emotion to their experiences in school, a far cry from the positive, constructive outcomes proposed by contemporary education policy.

4.5. Conformity

The sub-themes in this section highlight lyrics that describe multiple dimensions of Western education’s tendency to revere uniformity above all else. In the first sub-theme, “Dehumanization by Conformity”, artists invoke images of machines, factories and numbers to demonstrate how, in their view, the Anglo-American school systems have commoditized studentship. They feel that the students in these systems are not treated as intricate individuals, but instead regarded as simply statistics. The following sub-theme, “Conformaphilia”, describes the artists’ perception of teacher and administrator fixation on conformity. These lyrics contain the artist’s perception of the point of view held by administrators and officials who enforce conformity. Our third sub-theme, “Rebellion Against Conformity”, highlights the conformist aspects of school and details attempts, both small and great, to revolt against such perceived tyranny. “Harmful Conformist Training PTSD”, this section’s final sub-theme, makes specific references to harm and illness brought on by the enforced conformity these artists felt subjected to during their school experience.

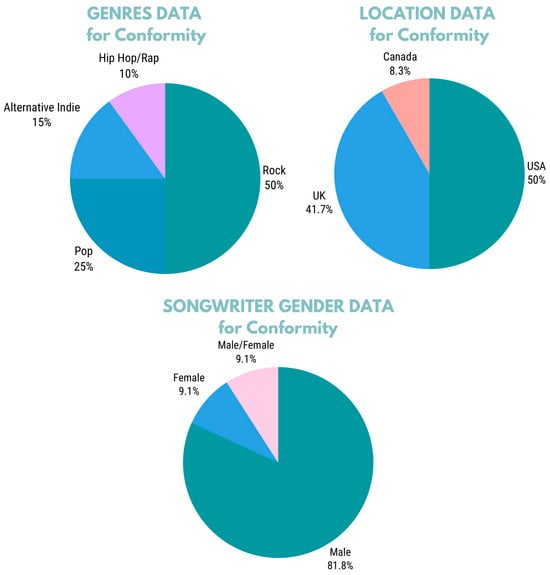

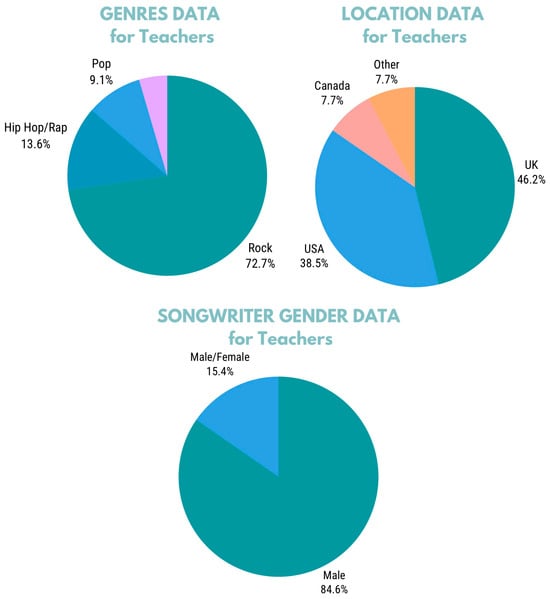

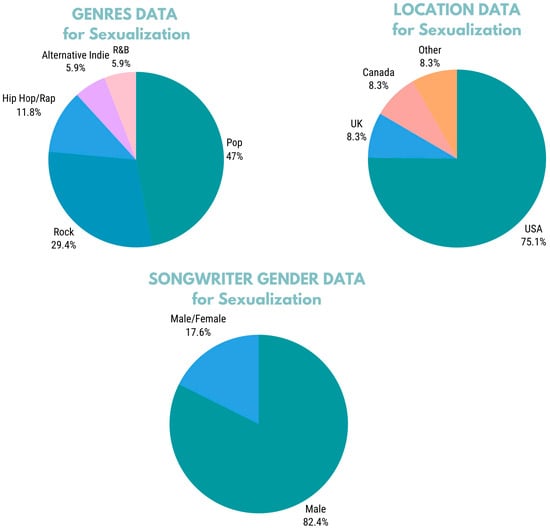

Figure 9.

Data outlining the distribution of songs specific to the theme “Conformity” across various genres of music, geographic locations of origin and songwriter gender.

4.5.1. Dehumanization by Conformity

According to songs collected for this theme, students can be seen as simply bricks, numbers or cogs—dehumanized in the name of systematizing education. One of the most popular anti-school songs to be released is Pink Floyd’s 1979 hit “Another Brick in the Wall Pt. 2”. The song sold over 4 million copies worldwide, was nominated for a Grammy Award and remained on Billboard music charts for 25 weeks. In an attempt to further “stick it to the man”, they used a local school choir to add their voices to the song’s “memorable hook” [3] (p. 124). The students and band sing, “Hey! Teachers! Leave them kids alone/All in all you’re just another brick in the wall/All in all you’re just another brick in the wall”.

This song’s popularity has garnered significant attention and even detailed scrutiny by listeners and critics alike as they attempt to analyze the meaning behind the language used by Pink Floyd. Brehony uses this lens of schooling to dissect the song. He writes, “The brick metaphor can be read as a reference to a bureaucratically organised schooling that produces uniform citizens to take their allotted place in the labour market and the existing system of social relations” [3] (p. 115). Instead of attending to the education of the whole child, students, according to Pink Floyd, experience schooling that values conformity over individuality. This concept was emphasized by Roger Waters, co-founder and songwriter of Pink Floyd, in his 1979 interview with Tommy Vance, during which he presents a vivid description of teachers in his own memory: “Just trying to keep [students] quiet and still, and crush them into the right shape, so that they would go to university and ‘do well’” [74]. With this perspective, students are compelled to sacrifice their humanity in order to fit the mold that the system has made for them. The music video for the song makes this point as school children are depicted in shapeless masks marching along to the beat only to be eventually processed into ground meat.

Eighties pop duo Hall & Oates use their song “Adult Education” to make a similar comment about certain school systems’ dehumanizing view of students. They sing, “You’re waiting for a separation/You’re nothing but another odd number”. My Chemical Romance adds to this discourse in their punk anthem “Teenagers” where they argue that the educational system regards students as “Another cog in the murder machine”. Both American and British school systems are painted here as machines that cripple the individuality of students and neglect them for the sake of conformity.

4.5.2. Conformaphilia

Songs in this theme not only accuse schools of stealing a student’s individuality, but of reveling in this thievery. “The Logical Song” by Supertramp writes from the perspective of administrators and teachers, “Won’t you sign up your name, we’d like to feel you’re acceptable/Respectable, oh presentable, a vegetable”. These educators, as depicted by Supertramp, seem not to be working to cultivate respect and acceptance for diversity among students. Rather, they appear to have a goal of smoothing over these differences in order to make them appear “respectable” and “acceptable”. Supertramp songwriter Roger Hodgson commented on this piece to Classic Rock Magazine, “The song was very autobiographical. I knew how to be sensible, logical and cynical but I didn’t have a clue who I was. To me, that is the life journey we are on; to find out who we are and what life is. They don’t teach you that in school” [61] Hodgson’s annotations to this song contextualize the point of view explored by Supertramp that educators are concerned neither with individuality nor diversity, but rather with instilling sense, logic and, consequently, cynicism.

Pink Floyd also accuses teachers of this “conform-aphilia” in their song “One of the Few”. Again writing from a teacher’s perspective, the band sings, “Make ’em mad/Make ’em sad/Make ’em add two and two/…/Make ’em do what you want them to/Make ’em laugh/Make ’em cry/Make ’em lay down and die”. According to Pink Floyd, a teacher’s purpose here is not to collaborate with or accommodate students, but to force them to behave and perform—a practice the band finds equivalent to a student laying down and dying. Pink Floyd finds this desire to enforce behavior is integral to the role of a teacher.

Singer-songwriter John Mayer shares his restrictive school experience in his song “No Such Thing”. He sings, “They love to tell you/Stay inside the lines/But something’s better/On the other side”. Here Mayer is not simply complaining about the confining school atmosphere, but accusing teachers of enjoying their power to enforce conformity. Certainly, teachers need a degree of power to facilitate learning [60]; however, these lyrics describe power-hungry teachers who bury student individuality in the name of molding palatable members of society.

There are many teaching styles to choose from when considering how to run a classroom, each of which affords teachers varying degrees of control. A high-control style of teaching describes the approach as authoritarian, yet fair, with an emphasis on provoking certain behaviors in students [75]. However, “authoritarian” would be too tame a word to describe the management styles of the teachers depicted in these songs, whose behavior borders on the tyrannical. In the eyes of these artists, teachers revel in their power to enforce conformity. Such totalitarian teachers can create classrooms where “children suffer significant trauma, often with attendant learning and psychiatric problems” [76] (p. 196). This victimization of young students by adults charged with their care and protection can be detrimental not only to their learning but to their mental health, as well.

4.5.3. Rebellion against Conformity

Since its inception, Rock and Roll as a genre has been home to artists and songs that criticize and protest the status quo. Author Charles Brown described the emergence of Rock and Roll in the fifties as, “the sounds of rebellion to an American art form” [77]. It comes as no surprise, then, that in the face of pressures to conform at school, artists turn to Rock and Roll style music to discuss school, often using their lyrics as an outlet for their rebellious feelings. The Downtown Fiction writes about school and their urges to rebel in their song “Where Dreams Go to Die”. They sing, “But bring us up to follow rules/And throw us all in cubic rooms/But we’re not gonna sit by idle./We’re getting out, we’re gonna find our way”. By invoking images of “cubic rooms” and idleness, The Downtown Fiction portrays school as an environment devoid of individuality and freedom. It is only by “getting out” that the band feels as though they can be free to truly express themselves. Their devotion to expression and refusal to “sit by idle” can be interpreted as a form of rebellion against a system perceived as designed to snuff out identity.

Indie band Let’s Eat Grandma expresses a similar sentiment in their song, “Deep Six Textbook”. The lyrics read, “We live our lives in the textbook, letter by letter/I feel like standing on the desk, and screaming ‘I don’t care’”. The lyrics here are fairly straightforward in their depiction of rebellion against conformity; however, the title adds an even deeper layer to the song. The verbal phrase “deep six” stems from slang used in the Navy to refer to the depth at which undesired objects must be discarded [78]. Like the other artists in this theme, the writers of these lyrics feel that school stifles their individuality (treating students, as Skye Sweetnam’s “Billy S”. states, like “clones”) and that textbooks, symbols of conformity, should be not only done away with but destroyed. It is significant that both of these bands have female lyricists. Indeed, female composers contributed more to the category of fighting against conformity than almost any other theme discussed here.

4.5.4. Harmful Conformist Training PTSD

Thus far, the lyrics for this theme have presented artists who felt their personalities were suppressed by school and whose teachers found joy in this suppression. The artists of the following songs experienced similar suppression. However, they express in their songs a sense of traumatization from school that remains with them far past graduation day. Phish’s “Chalkdust Torture” recounts their school experience as one of torture. They sing, “But who can unlearn all the facts that I’ve learned/As I sat in their chairs and my synapses burned/And the torture of chalk dust collects on my tongue”. Metal band Deathklok incites violent imagery in the lyrics of their song “Go Forth and Die”: “Now you’ve graduated/Mind is mutilated/Thrust into the world/Feeling segregated”. This feeling of unpreparedness is echoed in the work of prolific rock star John Lennon in his song “Working Class Hero”: “When they’ve tortured and scared you for 20 odd years/Then they expect you to pick a career/When you can’t really function, you’re so full of fear”. Here the artists do not simply feel inadequate for life after school—they feel that school itself has weakened their ability to properly function in society. They associate their educative experiences with torture and mutilation, rather than uplifting academic preparation, as many schools claim as their goal for students.

4.6. Teachers