Teachers’ Use of Knowledge in Curriculum Making: Implications for Social Justice

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- What are the implications for social justice of teachers’ use of knowledge when making the curriculum?

- ○

- How does the way that teachers engage with knowledge influence the redistribution of knowledge through the curriculum?

- ○

- Does teachers’ use of knowledge influence the representation and recognition of pupils through the curriculum?

- ○

- In what ways does the knowledge teachers draw on enable equitable participation for pupils?

2. Teachers Knowledge in Curriculum Making

- Knowledge of learners;

- Knowledge of subject matter and curriculum goals;

- Knowledge of teaching [11].

3. Scottish Context

4. Conceptual Framework

5. Methods

5.1. The Study Participants

5.2. Instrumentation

5.3. Data Collection

5.4. Data Analysis

- Knowledge of Pupils

- a.

- Pupils’ interests;

- b.

- Pupils’ learning;

- c.

- Pupils’ progression;

- d.

- Data about pupils.

- Knowledge of Context

- a.

- Pupils (beyond the classroom);

- b.

- Parents and local community;

- c.

- Local area.

- Knowledge of Teaching

- a.

- Pedagogy;

- b.

- Classroom Practice (teachers’ actions in the classroom, including classroom management and assessment).

- Knowledge of Curriculum

- a.

- Curriculum framework;

- b.

- Curriculum areas;

- c.

- Content knowledge.

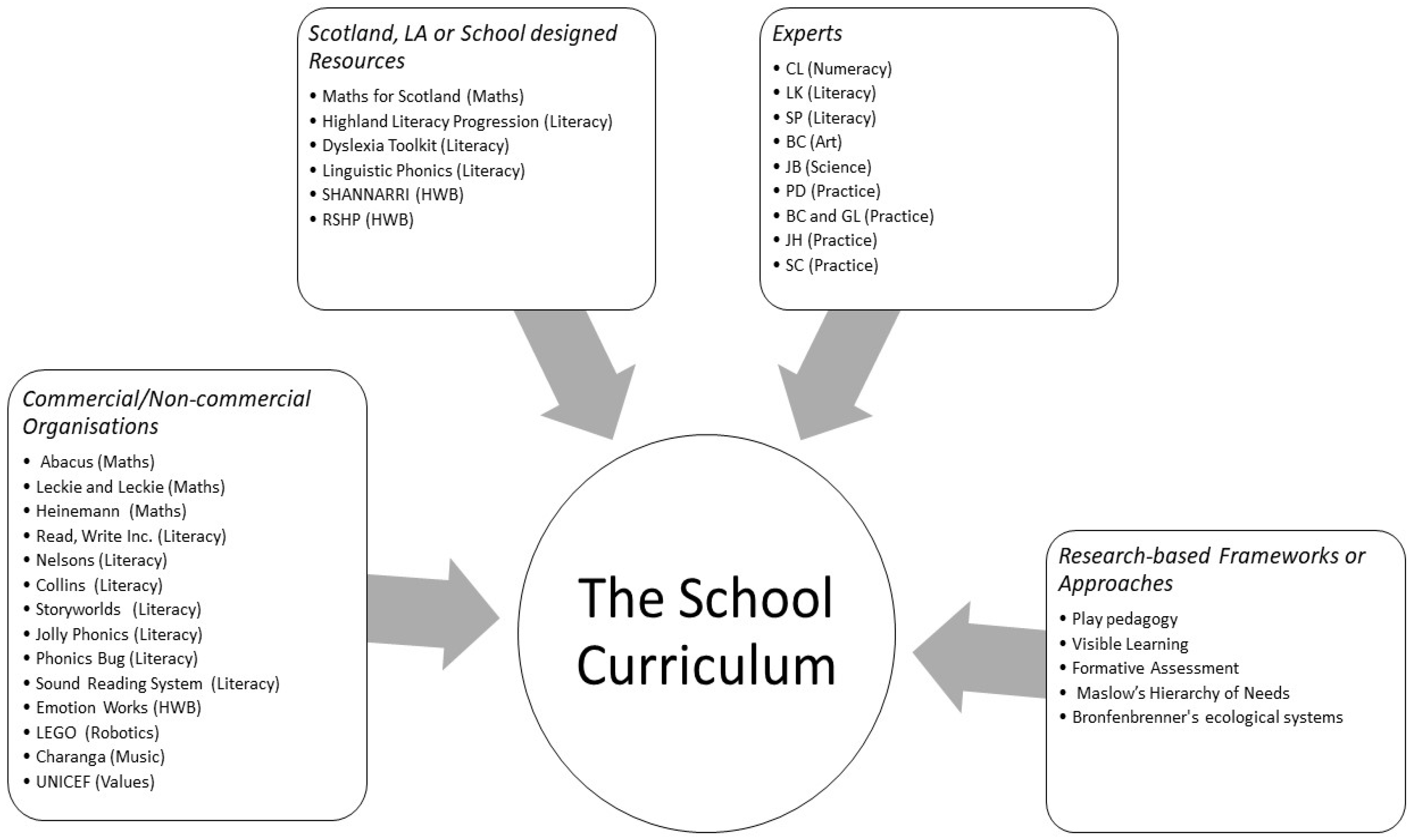

- External Knowledge

- a.

- Resources (teaching schemes, etc.);

- b.

- Experts.

5.5. Limitations

6. Analysis and Discussion

6.1. What Knowledge?

‘not just a, a child that has to go through the same learning experience as the next child but very much tailoring it to the, the interests, needs of that child at, who’s part of that particular class.’(Headteacher D)

‘Linking into the child and their world and that’s, that’s where we come. So curriculum then needs to be about the children in that setting and those, those priorities because that’s really different across [the LA]. We’ve got a wide range of different, different priorities in different towns, different challenges.’(Teacher C)

‘We’re in, you know, a beautiful bit of the country, we have a beach nine miles away, we’re six miles away from the glens, we have forests on our doorsteps, we’ve got castles…’(Promoted Post D)

‘So can we access the, the beach cause we’re right on a, we’re a coastal school. So we, can we go down and access the beach…’(Headteacher D)

‘The other problem with the Abacas is that they don’t exactly marry up with the Scottish curriculum, so there’s parts of our curriculum that aren’t maybe covered.’(Teacher F)

‘We’ve been creative with how we’ve used the resources that we have.’(Promoted Post D)

‘In terms of the actual scheme, there’s a lot, a lot in it. Again, I just, I have to cherry pick a little bit because there’s just too much in a lesson and sometimes it’s a bit dry, you know, the ideas they’ve got, and you think, oh gosh, so often I might take the learning and, you know, the workbook pages that they’re suggesting and things, but I’ll put my own spin on it, and I tend to find that that’s, that is better.’(Teacher F)

‘We’re looking at linguistic phonics as a replacement to Jolly Phonics and a viable option to things like Read Write inc, which are very expensive for schools to buy and require a lot of upkeep, and there are pedagogical differences between sort of traditional phonics, of which I would include Jolly Phonics, Read Write inc, Phonics Bug, and all the rest of these, and linguistic phonics.’(Promoted Post F)

‘And in the past we’ve tried tae pick up things because we felt that well it’s coming at us like, you know, Government things. You know, like, you know, there, you know, it’s coming at us so we have to do it. Whereas now we’re much more choosy about well what, what are, what are, what does our school need, what dae our learners need? And we come from that point a’ view rather than what is getting thrown at us and what dae we need tae look at.’(Headteacher C)

‘You know, the new, the latest writing guidance or the latest writing programme’ll come out from one of these big, big publication companies and you see those schools being sucked into it. ‘Oh yeah we need the latest thing, we need the, the best thing.’(Teacher C)

6.2. How Were Decisions Made?

‘It has to be based on relationships. You have to get to know the children.’(Promoted Post B)

‘Well for me it’s always building relationships wi’ the kids and making them be the best they can be.’(Teacher D)

- as relationships allow teachers and pupils to shape the curriculum together: ‘I think that’s what Curriculum for Excellence has allowed us to do, you know, we’ve got the outcomes there, but really take it where the children want to go and facilitate that for them.’ (Rural Teacher D). This involved dialogue with the pupils:

‘The other part is very much about involving the children in that two, two way feedback and actually speaking with them and asking them about success criteria and learning intentions and making sure that it’s not a guessing game.’(Headteacher D)

‘We have a big focus at [School name] on pupils taking ownership now of their learning, being assessment capable learners, so being able to, you know, assess their own work, assess their peers’ work, speak just, you know, be very motivated to want to learn more, or want to get better at something without the teacher having to tell them all the time.’(Promoted Post C)

‘The curriculum is there, but it’s for us as professionals in order to be able to build, if you like, the capacity, in order to be able to manage it.’(Promoted Post A)

‘The curriculum’s there for you and that’s basically your framework and that guides you through what you’ve actually got to teach. With experiences and outcomes certainly with your social studies and things like that we do have some freedom as to how you teach it in the context.’(Teacher D)

‘We’ve been given Curriculum for Excellence, we’re given, you know, the outline of our experiences, and, that these children should be having and what that should look like in terms of outcome, so we are given that, so our job therefore is to ensure that they have those experiences in the best way possible, so thinking about the how, how things are delivered, as opposed to the what is delivered.’(Rural Headteacher A)

‘The curriculum supports the pedagogy and the pedagogy supports the curriculum, that there needs to be, you know, there needs to be both, you can’t speak about one without the other almost.’(Teacher A)

‘I think there’s much more emphasis on teaching children about healthy eating, about healthy relationships with social media, the effects on mental health of different, you know, all these things are becoming more part of what we need to make sure that children get, that maybe before weren’t as much of a priority.’(Rural Headteacher A)

‘Having colleagues be thinking more broadly around subject areas, curricular areas, links, so we’ve kind of looked at the UN for guidance, you know, in terms of so where, where are the main, or what are the main challenges to the world is basically how we go, to humanity.’(Promoted Post A)

6.3. Whose Knowledge?

‘It’s very much seeing where their needs are and that’s, that’s the difference and being reflective and being responsive towards what they need.’(Promoted Post B)

‘We start with the child and we consider their world’(Teacher C)

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Overview of the Themes Generated from the Interviews

| Themes | Headteachers | Promoted Posts | Teachers | |

| Knowledge of Pupils | Pupils’ interests | A, B, C, D Ar, Br | A, B, C, D, E, F | A, B, C, D, E, F, G, Ar, Br, Cr, Dr |

| Pupils’ learning | C, D, Br | A, C, E | G, Ar, Br, Dr | |

| Pupils’ progression | C, D, Ar, Br | A, B, C, D | G, Ar, Dr | |

| Data about pupils | A, B, C, Ar | C, D | D | |

| Knowledge of Context | Pupils (beyond the classroom) | A, D, Ar, Br | A, D | C, E |

| Parents and local community | A, C, D, Ar, Br | A, B, C, D, E, F | B, C, E, G Ar, Br, Dr | |

| Local area | C, D, Ar, Br | B, C, D, E | C, E | |

| Knowledge of Teaching | Pedagogy | A, B, C, D Ar, Br | A, B, C, D, E, F | A, B, C, D, E, F, G, Ar, Br |

| Practice | A, C, D, Br | B, C, E | E, F, Cr | |

| Knowledge of Curriculum | Curriculum framework | A, Ar, Br | A, B, C, D, E, F | A, B, C, D, E, F, G, Cr, Dr |

| Curriculum areas | A, B, D, Ar, Br | A, B, C, D, F | A, F, Br | |

| Content knowledge | D | F | Ar | |

| External Knowledge | Resources (teaching schemes, etc.) | A, B, C, Br | D, E, F | A, C, E, F, G, Ar, Cr |

| Experts | A, B, D Ar, Br | A, B, C, D, E, F | A, B, C, D, E, F, G, Ar, Br, Dr | |

References

- Darling-Hammond, L. Constructing 21st-century teacher education. J. Teach. Educ. 2006, 57, 300–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priestley, M.; Alvunger, D.; Philippou, S.; Soini, T. Curriculum Making in Europe: Policy and Practice within and across Diverse Contexts; Emerald Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Bruner, J. The culture of education. In The Culture of Education; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Wenger, E. Communities of Practice: Learning, Meaning, and Identity; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Zipin, L.; Brennan, M. Ethical vexations that haunt ‘knowledge questions’ for curriculum. In Curriculum Challenges and Opportunities in a Changing World: Transnational Perspectives in Curriculum Inquiry; Palgrave Macmillan: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 173–193. [Google Scholar]

- Riddle, S.; Mills, M.; McGregor, G. Curricular justice and contemporary schooling: Towards a rich, common curriculum for all students. Curric. Perspect. 2023, 43, 137–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraser, N. Scales of Justice: Reimagining Political Space in a Globalizing World; Columbia University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Young, M. Powerful knowledge: An analytically useful concept or just a ‘sexy sounding term’? A response to John Beck’s ‘Powerful knowledge, esoteric knowledge, curriculum knowledge’. Camb. J. Educ. 2013, 43, 195–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giroux, H. Pedagogy and the Politics of Hope: Theory, Culture, and Schooling: A Critical Reader; Routledge: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Shulman, L.S. Those who understand: Knowledge growth in teaching. Educ. Res. 1986, 15, 4–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darling-Hammond, L.; Hyler, M.E.; Gardner, M. Effective Teacher Professional Development; Learning Policy Institute: Palo Alto, CA, USA, 2017; Available online: https://learningpolicyinstitute.org/sites/default/files/product-files/Effective_Teacher_Professional_Development_REPORT.pdf (accessed on 20 May 2023).

- Philpott, C. Socioculturally situated narratives as co-authors of student teachers’ learning from experience. Teach. Educ. 2014, 25, 391–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verloop, N.; Van Driel, J.; Meijer, P. Teacher knowledge and the knowledge base of teaching. Int. J. Educ. Res. 2001, 35, 441–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben-Peretz, M. Teacher knowledge: What is it? How do we uncover it? What are its implications for schooling? Teach. Teach. Educ. 2011, 27, 3–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kereluik, K.; Mishra, P.; Fahnoe, C.; Terry, L. What knowledge is of most worth: Teacher knowledge for 21st century learning. J. Digit. Learn. Teach. Educ. 2013, 29, 127–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koehler, M.J.; Mishra, P.; Cain, W. What is technological pedagogical content knowledge (TPACK)? J. Educ. 2013, 193, 13–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodwin, A.L.; Darity, K. Social justice teacher educators: What kind of knowing is needed? J. Educ. Teach. 2019, 45, 63–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill-Jackson, V.; Craig, C.J. (Re) Constructing Teacher Knowledge: Old Quests for New Reform. J. Teach. Educ. 2023, 74, 5–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Z. Knowledge, Content, Curriculum and Didaktik: Beyond Social Realism; Routledge: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Wrigley, T. ‘Knowledge’, curriculum and social justice. Curric. J. 2018, 29, 4–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Virmani, R.; Williamson, P. Lessons for teacher educators about learning to teach with technology. In Building Bridges: Rethinking Literacy Teacher Education in a Digital Era; SensePublishers: Rotterdam, The Netherlands, 2016; pp. 77–90. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts, P. Knowledge beyond the Metropole: Curriculum, rurality and the global south. In Curriculum Challenges and Opportunities in a Changing World: Transnational Perspectives in Curriculum Inquiry; Green, B., Roberts, P., Brennan, M., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 123–139. [Google Scholar]

- Connell, R. Using southern theory: Decolonizing social thought in theory, research and application. Plan. Theory 2014, 13, 210–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priestley, M.; Priestley, M.R.; Biesta, G.; Robinson, S. Teacher Agency: An Ecological Approach; Bloomsbury Publishing: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Adams, P. Scottish education: Between the UK and the Nordic. Nord. Stud. Educ. 2023, 43, 43–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bristow, T. Post African futures: Positioning the globalized digital within contemporary African cultural and decolonizing practices. Crit. Afr. Stud. 2017, 9, 281–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zipin, L.; Fataar, A.; Brennan, M. Can social realism do social justice? Debating the warrants for curriculum knowledge selection. Educ. Chang. 2015, 19, 9–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- General Teaching Council for Scotland. The Standard for Full Registration Mandatory Requirements for Registration with the General Teaching Council for Scotland Formal Enactment 2 August 2021. 2021. Available online: https://www.gtcs.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/standard-for-full-registration.pdf (accessed on 30 May 2023).

- Mishra, P. Considering Contextual Knowledge: The TPACK Diagram Gets an Upgrade. J. Digit. Learn. Teach. Educ. 2019, 35, 76–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scottish Government. Curriculum for Excellence; Scottish Government: Edinburgh, UK, 2009.

- Priestley, M.; Minty, S. Curriculum for Excellence: ‘A brilliant idea, but…’. Scott. Educ. Rev. 2013, 45, 39–52. [Google Scholar]

- Baumfield, V.; Hulme, M.; Livingston, K.; Menter, I. Consultation and engagement? The reshaping of teacher professionalism through curriculum reform in 21st Century Scotland. Scott. Educ. Rev. 2010, 42, 57–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shapira, M.; Priestley, M. Narrowing the curriculum? Contemporary trends in provision and attainment in the Scottish curriculum. Scott. Educ. Rev. 2018, 50, 75–107. [Google Scholar]

- Biesta, G. Putting the World in the Centre: A Different Future for Scotland’s Education. Scott. Educ. Rev. 2023, 1, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowden, K.; Hall, S.; Bravo, A.; Orr, C.; Chapman, C. Knowledge Utilisation Mapping Study: Scottish Education System; Scottish Government: Edinburgh, UK, 2019.

- Torrance, D.; Forde, C. Redefining what it means to be a teacher through professional standards: Implications for continuing teacher education. Eur. J. Teach. Educ. 2017, 40, 110–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biesta, G.; Priestley, M.; Robinson, S. Talking about education: Exploring the significance of teachers’ talk for teacher agency. In Teachers Matter—But How? Routledge: London, UK, 2019; pp. 38–54. [Google Scholar]

- Young, M. Bringing Knowledge Back in: From Social Constructivism to Social Realism in the Sociology of Education; Routledge: London, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Fraser, N. Reframing justice in a globalizing world. New Left Rev. 2005, 36, 69. [Google Scholar]

- Le Goff, A. From a Theory of Justice to a Critique of Capitalism: How Nancy Fraser Revitalizes Social Theory. In Thinking with Women Philosophers: Critical Essays in Practical Contemporary Philosophy; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 75–103. [Google Scholar]

- Keddie, A. Schooling and social justice through the lenses of Nancy Fraser. Nancy Fraser Soc. Justice Educ. 2020, 53, 40–56. [Google Scholar]

- Fraser, N. Reframing justice in a globalising world. In Adding Insult to Injury: Nancy Fraser Debates Her Critics; Olson, K., Ed.; Verso: London, UK, 2008; pp. 273–294. [Google Scholar]

- Fraser, N. Rethinking recognition. New Left Rev. 2000, 3, 107. [Google Scholar]

- Fraser, N. Feminist politics in the age of recognition: A two-dimensional approach to gender justice. Stud. Soc. Justice 2007, 1, 23–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraser, N. From Redistribution to Recognition? Dilemmas of Justice in a ‘Post-Socialist’ Age. New Left Rev. 1995, 212, 68–93. [Google Scholar]

- Olson, K. Adding Insult to Injury: Nancy Fraser Debates Her Critics; Olson, K., Ed.; Verso Books: London, UK, 2008; pp. 246–272. [Google Scholar]

- Sen, A. Informational bases of alternative welfare approaches: Aggregation and income distribution. J. Public Econ. 1974, 3, 387–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen, A. Equality of what? In The McMurrin S Tanner Tanner Lectures on Human Values; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1980; Volume 22, pp. 197–220. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, E.S. What is the Point of Equality? Ethics 1999, 109, 287–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drydyk, J. A capability approach to justice as a virtue. Ethical Theory Moral Pract. 2012, 15, 23–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen, A. What Do We Want from a Theory of Justice? J. Phil. 2006, 103, 215–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nussbaum, M.C. Human functioning and social justice: In defense of Aristotelian essentialism. Polit. Theory 1992, 20, 202–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nussbaum, M.C. Frontiers of justice: Disability, nationality, species membership. In He Tanner Lectures on Human Values; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Scottish Government. Local Government: Constitution and Democracy. Edinburgh, UK, n.d. Available online: https://www.gov.scot/policies/local-government/ (accessed on 20 May 2023).

- Scottish Government. Scottish Government Urban Rural Classification 2020; Scottish Government: Edinburgh, UK, n.d. Available online: https://www.gov.scot/publications/scottish-government-urban-rural-classification-2020/pages/2/ (accessed on 20 October 2023).

- Saldaña, J. The Coding Manual for Qualitative Researchers; Sage: London, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Scottish Government. Health and Wellbeing in Schools. n.d. Available online: https://www.gov.scot/policies/schools/wellbeing-in-schools/ (accessed on 22 October 2023).

- Scottish Government. Getting It Right for Every Child (GIRFEC). Edinburgh, UK, n.d. Available online: https://www.gov.scot/policies/girfec/ (accessed on 22 October 2023).

- Cuban, L.; Jandrić, P. The dubious promise of educational technologies: Historical Patterns and future challenges. E-Learn. Digit. Media 2015, 12, 425–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hattie, J.; Yates, G.C. Visible Learning and the Science of How We Learn; Routledge: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Biesta, G. The school is not a learning environment: How language matters for the practical study of educational practices. Stud. Contin. Educ. 2022, 44, 336–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simmie, G.M. The Neo-liberal Turn in Understanding Teachers’ and School Leaders’ Work Practices in Curriculum Innovation and Change: A critical discourse analysis of a newly proposed reform policy in lower secondary education in the Republic of Ireland. Citizsh. Soc. Econ. Educ. 2014, 13, 185–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, M.A. An Educational Theory of Innovation: What Constitutes the Educational Good? Educ. Philos. Theory 2020, 52, 1016–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Z. Powerful knowledge, educational potential and knowledge-rich curriculum: Pushing the boundaries. J. Curric. Stud. 2022, 54, 599–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Coker, H.; Kalsoom, Q.; Mercieca, D. Teachers’ Use of Knowledge in Curriculum Making: Implications for Social Justice. Educ. Sci. 2024, 14, 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14010003

Coker H, Kalsoom Q, Mercieca D. Teachers’ Use of Knowledge in Curriculum Making: Implications for Social Justice. Education Sciences. 2024; 14(1):3. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14010003

Chicago/Turabian StyleCoker, Helen, Qudsia Kalsoom, and Duncan Mercieca. 2024. "Teachers’ Use of Knowledge in Curriculum Making: Implications for Social Justice" Education Sciences 14, no. 1: 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14010003

APA StyleCoker, H., Kalsoom, Q., & Mercieca, D. (2024). Teachers’ Use of Knowledge in Curriculum Making: Implications for Social Justice. Education Sciences, 14(1), 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14010003