Didactic Interventions: The Voices of Adult Migrants on Second Language Teaching and Learning in a Rural Area in Chile

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Second Language Acquisition and Migration

2.2. Spanish as a Second Language in Chile

3. Research Methodology

3.1. Method

3.2. Context and Participants

3.3. Data Collection

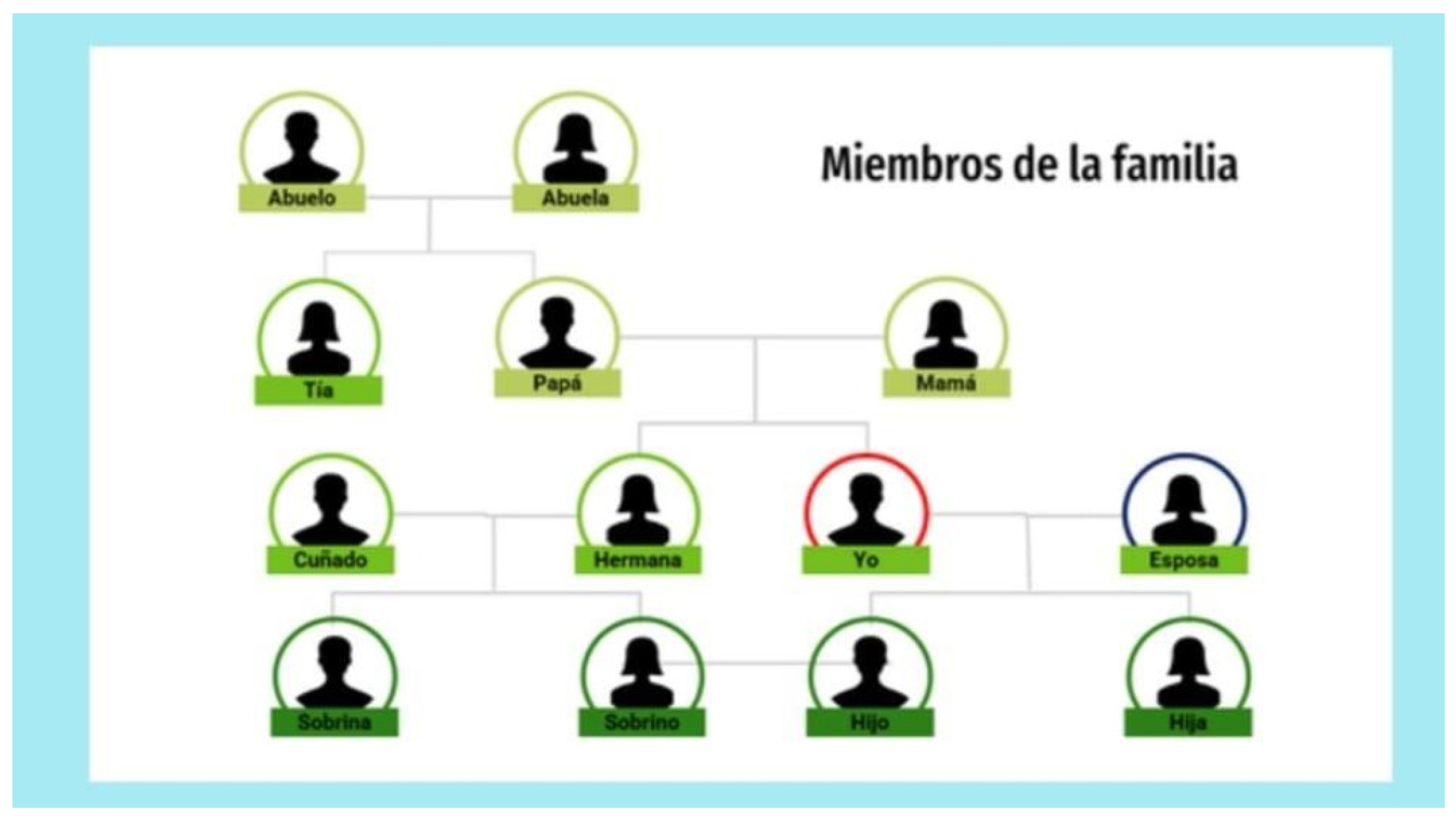

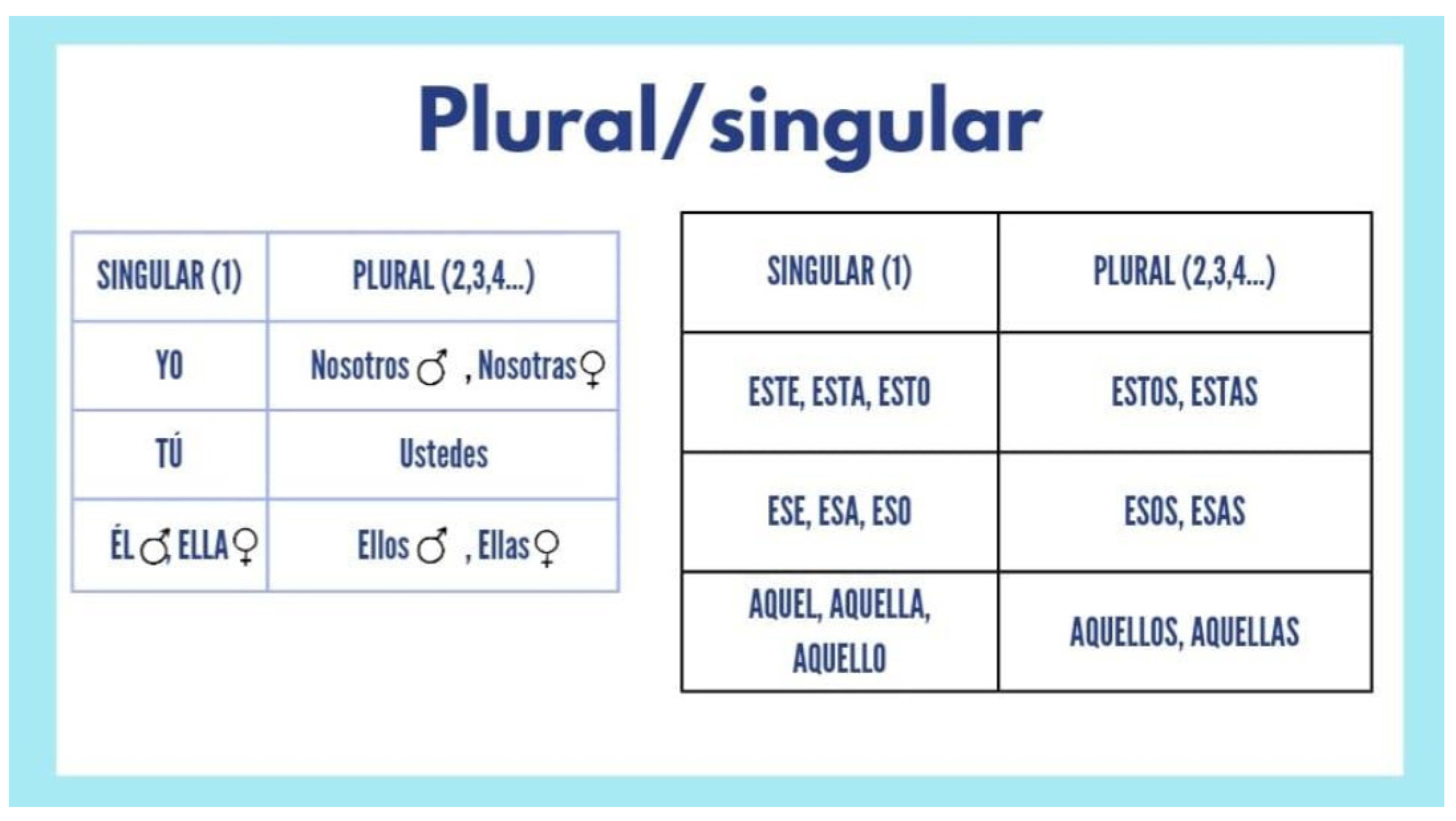

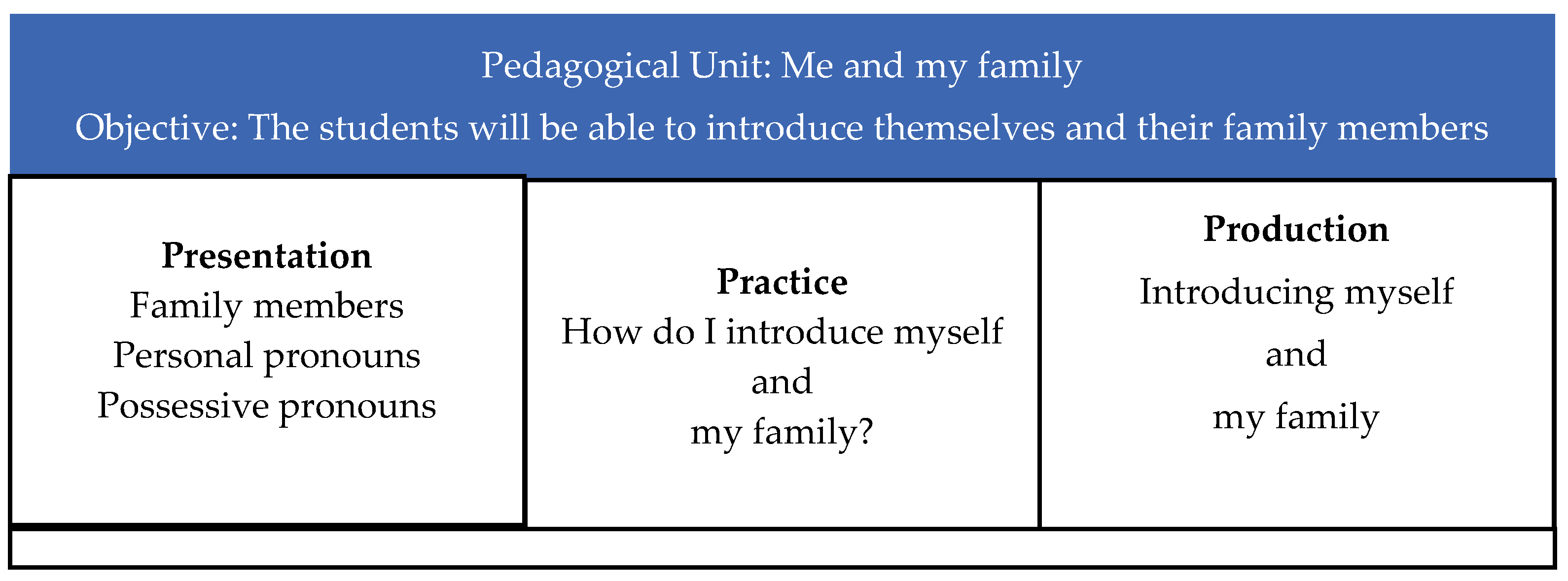

Intervention

- (1)

- Program for Teaching Spanish as a Second Language in a Migratory Context (ESL©M)

- (2)

- Pre-Intervention Phase: Contextual Understanding

- (3)

- Educational Intervention Summary

3.4. Data Analysis

4. Results

4.1. General Overview

4.2. The Perception of SL2 Teaching and Learning

4.2.1. Curricular Development: Teachers

The teachers are excellent; when they teach us, we understand because they are so effective. Having three teachers in the room is really beneficial because if I have a question about what one teacher is explaining, I can easily call another teacher and seek clarification. This way, I do not have to wait because sometimes everyone has questions at the same time.(FG1–I1)

The teachers are genuinely concerned about our progress, and they put in a lot of effort to help us communicate effectively in Spanish.(FG1–I3)

4.2.2. Curricular Development: Learning Strategies

I prefer to work individually because that allows me to think. I construct sentences on my own, without anyone telling me how to do it or offering assistance. I find that I can think more effectively on my own rather than in a group, and my teacher can provide feedback on whether it’s correct or needs improvement.(FG2–I3)

Not all my classmates have the same pace, and not everyone comprehends what the teachers are teaching quickly. So, I learn better when I work on my own.(FG1–I4)

We need more practice in communication and pronunciation. Haitian Creole is quite different in terms of communication and pronunciation; it has different sounds.(FG2–I5)

4.2.3. Curricular Development: Linguistic Mediators

Having a fellow countryman/-woman in the room [Haitian LM] is very beneficial for us. Sometimes, despite the teachers’ best efforts to make us understand everything, there are moments when we still struggle to comprehend. In those situations, she explains things to us in Haitian Creole, which helps us grasp the concepts without slowing down our learning. It enables us to progress more rapidly.(FG2–I4)

It is really beneficial to have them in our class because there are words that we do not understand, and she [the Haitian LM] knows more. She tells us what these words mean in Haitian Creole, which makes it much clearer for us. We don’t waste time trying to figure things out, she does her job really well. She is a great help.(FG1–I3)

4.2.4. Social Context: Literacy

I want to learn the Spanish of the Chileans, but the formal one—the one the teacher speaks—because I can learn the other type of Spanish on the street, without studying.(FG2–I1)

If a person did not go to school, or attended very little, it is more challenging to learn anything.(FG1–I4)

4.2.5. Social Context: Quality of Life

I think, Jacques, you must learn Spanish well to communicate with people. It is also crucial for my job; I could risk losing my job if my boss gives me an instruction and I do not understand it.(FG1–I3)

4.2.6. Social Context: Learning Environment Factors

My compatriots in Chile who live only with Haitians, speak only Haitian Creole, it is more difficult for them, even though they have arrived many years ago, but I work with Chileans, so I talk with them.(FG2–I1)

5. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Appendix B

References

- Ferguson-Patrick, K.E.S. Cooperative Learning in Swedish Classrooms: Engagement and Relationships as a Focus for Culturally Diverse Students. Educ. Sci. 2020, 10, 312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Organization for Migration. Migration Governance Indicators Profile 2021. Republic of Chile. 2021. Available online: https://publications.iom.int/books/migration-governance-indicators-profile-2021-republic-chile (accessed on 13 July 2023).

- International Organization for Migration. World Migration Report 2022. Switzerland. 2022. Available online: https://publications.iom.int/books/world-migration-report-2022 (accessed on 20 July 2023).

- Instituto Nacional de Estadísticas; Departamento de Extranjería y Migración. Informe de Resultados de la Estimación de Personas Extranjeras Residentes en Chile al 31 de Diciembre de 2021. Desegregación Nacional, Regional y Principales Comunas; Instituto Nacional de Estadísticas: Santiago, Chile, 2022.

- Santibáñez Gaete, G.P.; Maza Espinoza, C.M. Ser Niño Haitiano (que no Habla Español) en una Escuela Chilena. Tesis para Optar al Grado de Licenciatura en Teatro y Licenciatura en Educación; Universidad Academia de Humanismo Cristiano Santiago: Santiago, Chile, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Sumonte Rojas, V.; Sanhueza Henriquez, S.; Urrutia, A.; Hernández del Campo, M. Caracterización de la población migrante adulta no hispanoparlante en Chile como base para una propuesta de planificación de una segunda lengua. RLA Rev. Lingüística Teórica Apl. 2022, 60, 153–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isphording, I. What drives the language proficiency of immigrants? IZA World of Labor. 2015, 177, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toledo, G. Propuesta didáctica para la enseñanza de español como segunda lengua a inmigrantes haitianos en Chile. Leng. Migr. 2016, 8, 81–103. [Google Scholar]

- Condelli, L.; Wrigley, H.; Yoon, K.; Kronen, S.; Seburn, M. What Works for Adult ESL Literacy Students; American Institutes for Research and Aguirre International: Washington, DC, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Sosinski, M.R.; Young-Scholten, M.; Naeb, R. Notas sobre la enseñanza de alfabetización a inmigrantes adultos. Foro Profesores E/LE 2020, 16, 353–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ávila, A. La integración sociocultural de los grupos vulnerables de migrantes desde el aula de lenguas. Propuesta de actuación desde la dialectología social en la ciudad de Málaga. Leng. Migr. 2019, 11, 73–97. [Google Scholar]

- Mouti, A.; Maligkoudi, C.; Gogonas, N. Language needs analysis of adult refugees and migrants through the CoE—LIAM toolkit: The context of language use in tailor-made L2 thematic units design. In Proceedings of the 24th International Symposium on Theoretical and Applied Linguistics, Thessaloniki, Greece, 2–4 October 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Níkleva, D.; Contreras-Izquierdo, N. La formación de estudiantes universitarios para enseñar el español como segunda lengua a alumnos inmigrantes en España. Rev. Signos 2020, 53, 496–519. [Google Scholar]

- Níkleva, D.; García-Viñolo, M. La formación del profesorado de español para inmigrantes en todos los contextos educativos. Onomázein 2023, 60, 167–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bley-Vroman, R.W. What Is the Logical Problem of Foreign Lnguage Learning? Cambridge Uiversity Press: London, UK, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Caldwell-Harris, C.L.; MacWhinney, B. Age effects in second language acquisition: Expanding the emergentist account. Brain Lang. 2023, 241, 105269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortega, L. Understanding Second Language Acquisition; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Kyrligkitsi, A.; Mouti, A. A Multi-Method Profiling of Adult Refugees and Migrants in an L2 Non-Formal Educational Setting: Language Needs Analysis, Linguistic Portraits, and Identity Texts. Societies 2023, 13, 186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, A. Conceptualising the potential role of L1 in CLIL. Lang. Cult. Curric. 2015, 28, 74–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, L.P. Examining the functions of L1 use through teacher and student interactions in an adult migrant English classroom. Int. J. Biling. Educ. Biling. 2019, 22, 386–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Littlewood, W.; Baohua, Y. First language and target language in the foreign language classroom. Lang. Teach. 2011, 44, 64–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, D.; Wigglesworth, G. First Language Support in Adult ESL in Australia; National Centre for English Language Teaching and Resaerch: Sydney, Australia, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Galindo Merino, M.M. El eterno dilema: La lengua materna en la clase de español. Mosaico Rev. Promoción Apoyo Ensñanza Español 2013, 31, 19–25. [Google Scholar]

- Espinosa, M.J.; Figueroa, J.; Ávila, N. Escribir en L2 en la escuela chilena: Una caracterización de la escritura en español de estudiantes de origen haitiano en 5° básico. Rev. Signos 2022, 55, 37–60. [Google Scholar]

- Lenneberg, E.H. Biological Foundations of Language; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Siahaan, F. The Critical Theory Period Hypothesis of SLA Eric Lenneberg’s. J. Appl. Linguist. 2022, 2, 40–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarro, J.L.; Huguet, Á.; Sansó, C. Procesos de interdependencia entre lenguas. El caso del alumnado inmigrante en Cataluña. Rev. Psicodidáctica 2016, 21, 227–243. [Google Scholar]

- Saville-Troike, M.; Barto, K. Introducing Second Language Acquisition; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Field, J.; Ryan, J. The influence of prior schooling on second language learning: A longitudinal study with former refugees. N. Z. Stud. Appl. Linguist. 2022, 28, 52–68. [Google Scholar]

- Nikolov, M.; Djigunović, J.M. Recent research on age, second language acquisition, and early foreign language learning. Annu. Rev. Appl. Linguist. 2006, 26, 234–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schepens, J.; Van Hout, R.; Van der Slik, F. Linguistic dissimilarity increases age-related decline in adult language learning. Stud. Second. Lang. Acquis. 2023, 45, 167–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrice, L.; Tip, L.K.; Collyer, M.; Brown, R. ‘You can’t have a good integration when you don’t have a good communication’: English-language learning among resettled refugees in England. J. Refug. Stud. 2021, 34, 681–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fritzler, M. Migrant language and identity in the Spanish-speaking community in Israel. J. World Lang. 2023, 9, 68–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministerio de Educación de Chile. Establece Ley General de Educación. N° 20370. 2009. Available online: https://www.bcn.cl/leychile/navegar?idNorma=1006043&idParte=8780678 (accessed on 20 June 2023).

- Jiménez-Vargas, F.; Valdés, R.; Hernández-Yáñez, M.-T.; Fardella, C. Dispositivos lingüísticos de acogida, aprendizaje expansivo e interculturalidad: Contribuciones para la inclusión educativa de estudiantes extranjeros. Educ. Pesqui. São Paulo 2020, 46, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castillo, D.; Santa-Cruz, E.; Vega, A. Estudiantes migrantes en escuelas públicas chilenas. Calid. Educ. 2018, 49, 18–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castillo, D.; Gajardo, C. Inclusión y procesos de escolarización en menores migrantes que asisten a establecimientos de educación básica. In Proceedings of the IX Congreso Internacional—XV Congreso Nacional de Investigadores en Educación, INVEDUC, Osorno, Chile, 14–15 January 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Gómez Chaparro, S.; Sepúlveda, R. Inclusión de estudiantes migrantes en una escuela chilena: Desafíos para las prácticas del liderazgo escolar. Psicoperspectivas 2022, 21, 53–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stefoni, C.; Corvalán, J. Estado del arte sobre inserción de niños y niñas migrantes en el sistema escolar chileno. Estud. Pedagógicos 2019, 45, 201–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sumonte Rojas, V.; Friz, M.; Sanhueza, S.; Morales Mendoza, K. Programa de integración lingüística y cultural: Migración no hispanoparlante. Alpha 2019, 48, 179–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sumonte Rojas, V.; Sanhueza-Henríquez, S.; Friz-Carillo, M.; Morales-Mendoza, K. Migración no hispanoparlante en Chile: Tendiendo puentes lingüísticos e interculturales. Diálogo Andin. 2018, 57, 61–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toledo, G.; Cerda-Oñate, K.; Lizasoain, A. Formación inicial docente, currículum y sistema escolar: ¿cuál es el lugar de los niños y adolescentes inmigrantes no hispanohablantes en el sistema educativo chileno. Boletín Folología 2022, 57, 449–473. [Google Scholar]

- Chua, C.; Baldauf, R. Micro Language Planning 1. In Handbook of Research in Second Language Teaching and Learning; Hinkel, E., Ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2011; Volume 2, pp. 936–951. [Google Scholar]

- Universidad de Chile. Español para Extranjeros. 2023. Available online: https://uchile.cl/presentacion/relaciones-internacionales/programa-de-movilidad-estudiantil---pme/alumnos-libres-internacionales/espanol-para-extranjeros (accessed on 21 September 2023).

- Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile. Aprende Español en la UC. 2023. Available online: https://internacionalizacion.uc.cl/quiero-ir-a-la-uc/viajar-a-la-uc/aprende-espanol-en-uc-chile/ (accessed on 21 September 2023).

- Valdés, R.; Jiménez, F.; Hernández, M.-T.; Fardella, C. Dispositivos de acogida para estudiantes extranjeros como plataformas de intervención formativa. Estud. Pedagógicos 2019, 45, 261–278. [Google Scholar]

- Poblete, R.; Galaz, C. Aperturas y cierres para la inclusión educativa de niños/as migrantes en Chile. Estud. Pedagógicos 2017, 43, 239–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministerio de Educación. Política Nacional de Estudiantes Extranjeros 2018–2022; Ministerio de Educación: Santiago, Chile, 2018.

- Bailey, C.R.; Bailey, C.A. A Guide to Qualitative Field Research; Sage Publications Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Flick, U. An Introduction to Qualitative Research; Sage Publication Limited: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Alase, A. The interpretative phenomenological analysis (IPA): A guide to a good qualitative research approach. Int. J. Educ. Lit. Stud. 2017, 5, 9–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proudfoot, D.E.; Kebritchi, M. Scenario-based elearning and stem education: A qualitative study exploring the perspectives of educators. Int. J. Cogn. Res. Sci. Eng. Educ. 2017, 5, 7–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Lichtman, M. Qualitative Research for the Social Sciences; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Bisquerra, R.; Dorio, I.; Gómez, J.; Latorre, A.; Martínez, F.; Massot, I.; Mateo, J.; Sabariego, M.; Sans, T.; Torrado, M.; et al. Metodología de la Investigación Educativa, 6th ed.; La Muralla S. A.: Madrid, Spain, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- McMillan, J.; Schumacher, S. Investigación Educativa, 5th ed.; Pearson Education S. A.: Madrid, Spain, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez, G.; Gil, J.; García, E. Metodología de la Investigación Cualitativa, 2nd ed.; Ediciones Aljibe: Málaga, Spain, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, L.; Manion, L.; Morrison, K. Research Methods in Education, 8th ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Sumonte Rojas, V. Desarrollo de la competencia comunicativa intercultural en un programa de adquisición de la lengua criollo haitiana en Chile. Íkala Rev. Leng. Cult. 2020, 25, 155–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sumonte Rojas, V.; Fuentealba, A. Dimensión cultural en la adquisición de segundas lenguas en contexto migratorio. Estudios Pedagógicos. 2019, 45, 369–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toledo, G.; Quilodrán, F. Análisis de necesidades de aprendientes haitianos: Diseño, validación y aplicación del instrumento. Leng. Migr. 2020, 12, 101–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubio, M.; Rubio, R. Enseñanza de español para migrantes: Significados construidos por estudiantes universitarios sobre la interacción pedagógica en el aula. Logos Rev. Lingüística Filos. Lit. 2021, 31, 183–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sumonte, V.; Sanhueza, S.; Friz, M.; Morales, K. Inmersión lingüística de comunidades haitianas en Chile. Aportes para el desarrollo de un modelo comunicativo intercultural. Papeles Trab. 2018, 35, 68–79. [Google Scholar]

- Serra, J.M.; Vila, I. Lenguas, escuela e inmigración en Catalunya. In Multilingüismo, Competencia Lingüística y Nuevas Tecnologías; Lasagabaster, D., Sierra, J.M., Eds.; Horsori Editorial: Barcelona, Spain, 2005; pp. 75–89. [Google Scholar]

- Liddicoat, A.J.; Scarino, A. Intercultural Language Teaching and Learning; John Wiley & Sons: Oxford, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Vilà, R. La competencia comunicativa intercultural en alumnos de Enseñanza Secundaria de Catalunya. Segundas Leng. Inmigr. Red 2010, 3, 88–108. [Google Scholar]

- Dimova, S.; Yan, X.; Ginther, A. Local Language Testing. Design, Implementation and Development; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Cervantes, I. Marco Común Europeo de Referencia para las Lenguas: Aprendizaje, Enseñanza, Evaluación; Consejo de Europa: Estrasburgo, France, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Harmer, J. How to Teach English; Pearson Education Limited: London, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Bardín, L. Análisis de Contenido, 2nd ed.; Ediciones Akal, S. A.: Madrid, Spain, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- McIntosh, M.; Morse, J. Situating and constructing diversity in semi-structured interviews. Glob. Qual. Nurs. Res. 2015, 2, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almonacid-Fierro, A.; Philominraj, A.; Vargas-Vitoria, R.; Almonacid-Fierro, M. Perceptions about Teaching in Times of COVID-19 Pandemic: Experience of Secondary Education in Chile. Eur. J. Educ. Res. 2022, 11, 457–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, J.L.; Quincy, C.; Osserman, J.; Pedersen, O. Coding in-depth semistructured interviews: Problems of unitization and intercoder reliability and agreement. Sociol. Methods Res. 2013, 42, 294–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selinker, L. Interlanguage. Int. Rev. Appl. Linguist. Lang. Teach. 1972, 10, 209–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krashen, S. Principles and Practice in Second Language Acquisition; Pergamon: Oxford, UK, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Long, M.H. The role of the linguistic environment in second language acquisition. In Handbook of Research on Language Acquisition; Ritchie, W.C., Bhatia, T.K., Eds.; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 1996; pp. 413–468. [Google Scholar]

- Turnbull, M.; Dailey-O’Cain, J. Introdution. In First Language Use in Second Foreign Language Learning; Turnbull, M., Dailey-O´Cain, J., Eds.; Multilingual Matters: Bristol, UK, 2009; pp. 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Assaf, L.C. Supporting English language learners’writing abilities: Exploring third spaces. Middle Grades Res. J. 2014, 9, 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Cummins, J. Teaching minoritized students: Are additive approaches legitimate? Harv. Educ. Rev. 2017, 87, 404–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinker, S. La Tabla rasa: La Negación Moderna de la Naturaleza Humana; Ediciones Paidos: Barcelona, Spain, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Hennebry, J.; Petrozziello, A. Closing the gap? Gender and the global compacts for migration and refugees. Int. Migr. 2019, 57, 115–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmona, J.P. La enseñanza de E/LE a inmigrantes en las Escuelas Oficiales de Idiomas de Andalucía: Retos y propuestas. Doblele: Rev. Leng. Lit. 2018, 4, 122–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haznedar, B.; Peyton, J.; Young-Scholten, M. Teaching adult migrants: A focus on the languages they speak. Crit. Multiling. Stud. 2018, 6, 155–183. [Google Scholar]

- Benediktsson, A.I.; Ragnarsdottir, H. Communication and group work in the multicultural classroom: Immigrant students’ experiences. Eur. J. Educ. Res. 2019, 8, 453–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regan, V.; Diskin, C.; Martin, J. Language, Identity and Migration: Voices from Transnational Speakers and Communities; Peter Lang: Oxford, UK, 2016; Volume 46, pp. 597–600. [Google Scholar]

- Gay, G. Culturally Responsive Teaching: Theory, Research, and Practice, 3rd ed.; Teachers College Press: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Villegas, A.M.; Lucas, T. Preparing culturally responsive teachers: Rethinking the curriculum. J. Teach. Educ. 2002, 53, 20–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arvanitis, E. Culturally Responsive Pedagogy: Modeling Teachers’ Professional Learning to Advance Plurilingualism; Trifonas, P., Aravossitas, T., Eds.; Springer International Handbooks of Education: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; Volume Handbook of Research and Practice in Heritage Language Education; pp. 245–262. [Google Scholar]

- Galante, A. Linguistic and cultural diversity in language education through plurilingualism: Linking the theory into practice. In Handbook of Research Practice in Heritage Language Education; Springer: Cham, Germany, 2018; pp. 313–329. [Google Scholar]

| Age | Men | Women | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 to 19 | 3461 | 3559 | 13,136 |

| 20 to 39 | 43,868 | 27,188 | 144,470 |

| 40 to 59 | 404 | 278 | 27,375 |

| 60 to 79 | 42 | 69 | 793 |

| 80 and more | 58 | 33 | 91 |

| Total | 119,068 | 66,797 | 185,865 |

| Global Category | Initial Category | Descriptor | Primary Category |

|---|---|---|---|

| Perception of SL2 teaching and learning | Curricular Development | Category that gathers information about the implementation components of the program. | Teachers |

| Learning strategies | |||

| Linguistic mediator | |||

| Social Context | Category that collects information about the individual social context of the participants. | Literacy | |

| Quality of life | |||

| Learning environment factors |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sumonte Rojas, V.; Fuentealba, L.A.; Bahamondes Quezada, G.; Sanhueza-Henríquez, S. Didactic Interventions: The Voices of Adult Migrants on Second Language Teaching and Learning in a Rural Area in Chile. Educ. Sci. 2024, 14, 112. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14010112

Sumonte Rojas V, Fuentealba LA, Bahamondes Quezada G, Sanhueza-Henríquez S. Didactic Interventions: The Voices of Adult Migrants on Second Language Teaching and Learning in a Rural Area in Chile. Education Sciences. 2024; 14(1):112. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14010112

Chicago/Turabian StyleSumonte Rojas, Valeria, Lidia Andrea Fuentealba, Giselle Bahamondes Quezada, and Susan Sanhueza-Henríquez. 2024. "Didactic Interventions: The Voices of Adult Migrants on Second Language Teaching and Learning in a Rural Area in Chile" Education Sciences 14, no. 1: 112. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14010112

APA StyleSumonte Rojas, V., Fuentealba, L. A., Bahamondes Quezada, G., & Sanhueza-Henríquez, S. (2024). Didactic Interventions: The Voices of Adult Migrants on Second Language Teaching and Learning in a Rural Area in Chile. Education Sciences, 14(1), 112. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14010112