Guidelines for Supporting a Community of Inquiry through Graded Online Discussion Forums in Higher Education

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Interaction

1.2. Interaction and Discussion Forums

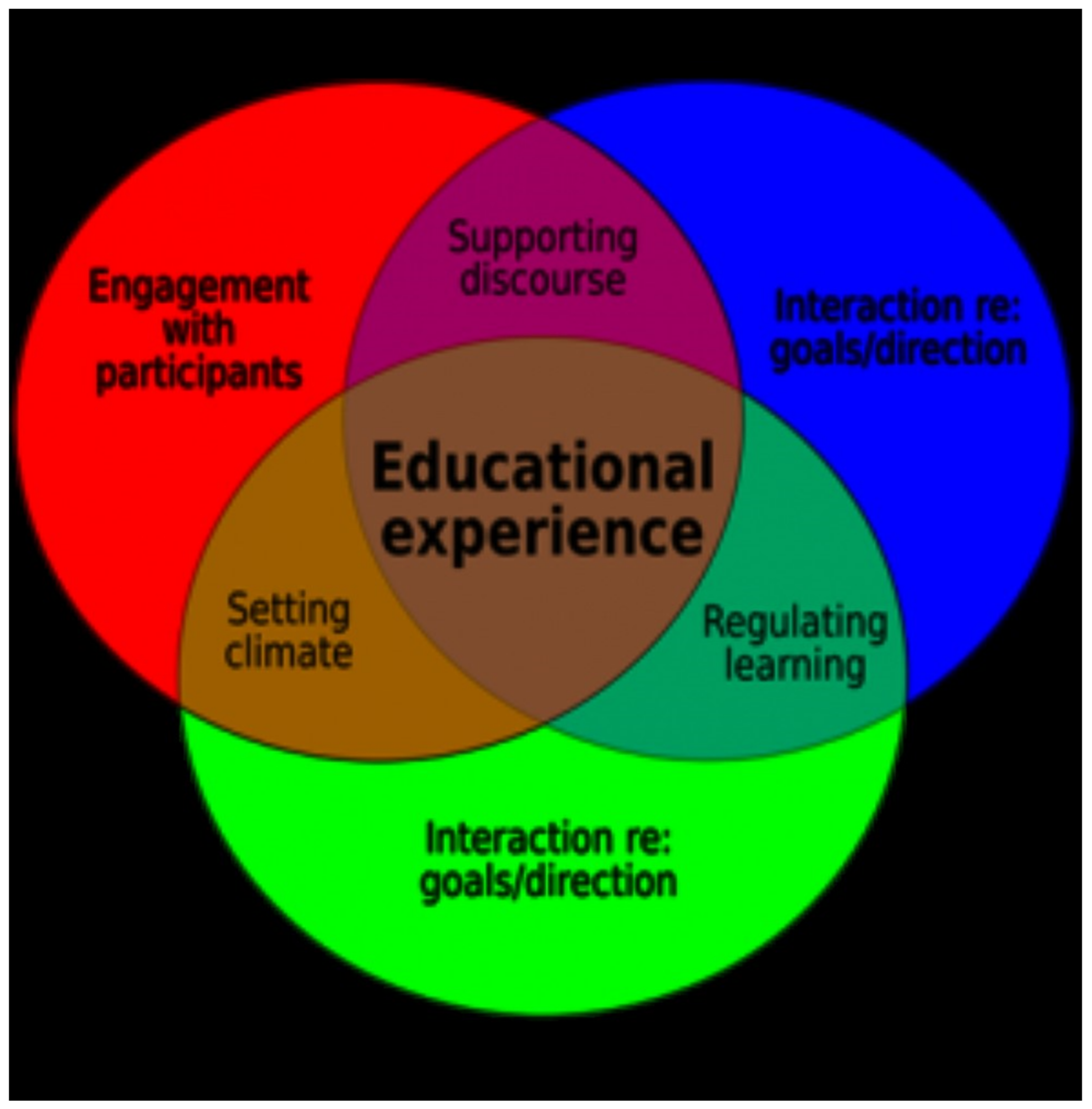

2. Theoretical Framework

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Research Design

3.2. Research Participants and Selection

3.3. Data Collection

3.4. Data Analysis

3.5. Trustworthiness

3.6. Ethical Considerations

4. Findings

4.1. Theme: 1 Social Presence

“The discussions have been constructive in my learning. First, it defeated the notion of non-collaborative learning opinionated by those against distance and online learning, which I was equally skeptical about at the onset”.(P6)

“Right from the outset, there was engagement: questions were being asked, and comments were being made on everyone’s posts. To me, this suggested that our posts were really being scrutinized—read with interest and intent by our peers. When you realize that your fellow students are taking the time to acknowledge your efforts and ask questions, it becomes even more important to respond. I believe this happened. Although some students were more prolific in their postings than others, I received at least one comment or question from each of the members of our group—for me, this established a real sense of community and investment in the process that I had not previously experienced”.(P4)

4.2. Theme: 2 Teaching Presence

“On my first discussion, I did contribute, although I didn’t do much because I did not understand the module properly and how to respond to other students’ posts. As it was my first time doing studies online, I feel I have tried. The problem I noticed after the feedback from the facilitator on grading was that I was not consulting enough sources to support my arguments. I just made some general comments”.(P9)

“I started to follow the guidelines from the feedback on what I must do to earn better marks and improve my posts. My reading in the lessons improved, and I managed to find the correct journals to use. The information from the discussions with my fellow students also assisted me”.(P9)

“I attribute the consistency and success of my contributions to the discussions to the clarity and quality of instructions the course instructors gave each time a question or instruction was posted. Also, the discussions were relevant to both theory and practice. I found them intellectually stimulating and valuable to my academic and career pursuits, so I pushed beyond my limit (competing demands) to contribute and learn from my peers, instructors, and literature”.(P6)

“The format that the facilitator adopted was also something I appreciated this year—instead of only responding individually, there was also ‘collective’ feedback provided, often with a follow-up question. Seeing a brief summation of all the contributions up to that point in the forum offered valuable insights. It framed the ‘new’ question posed: either to the group as a whole or to an individual student. These new questions then required us to go back and add to, or clarify, our initial post or address an entirely different aspect of the original question”.(P1)

4.3. Theme 3: Cognitive Presence

“I struggled to start a debate; I battled with referencing; and doubted my work initially, but I learned a lot and developed critical discussion and research skills along the road. From the beginning until the end of the discussions, I received positive feedback from my peers and the lecturers, which motivated me to read more thoroughly and respond to different questions”.(P3)

“My self-confidence grew because of the group discussions. All of the questions posed during the discussions aided in the development of my problem-solving and decision-making abilities. This module’s discussions inspired me to learn from other students and to explain course content in my own terms. I enhanced my research and referencing skills by participating in group discussions”.(P3)

5. Conclusions

- The study revealed that some participants were initially not sure how to approach the online discussions. Therefore, instructors should not assume that students know how to participate in graded discussions. Therefore, instructors could provide comprehensive guidelines and schedule a synchronous online meeting before discussions start to guide students from the beginning of the module.

- Participants in this study revealed that they followed assessment guidelines and were encouraged to improve their marks in the discussions. For this reason, grading of discussions is encouraged to create participation and learning opportunities.

- Participants in the study appreciated the highly structured graded online discussions. Hence, discussions should be structured to guide and engage students.

- Participants in this module were part of a small group, and they all knew each other, which created a community of trust and safety, and encouraged participation. For this reason, instructors are encouraged to divide modules with high student numbers into smaller groups if needed.

- Participants indicated that they were dependent on the presence of the instructor for guidance, feedback, and motivation. For this reason, the instructor should be present and actively involved in the module from the beginning until the end.

- Lastly, the findings indicated that the online discussions supported learning by creating a community of inquiry. It is therefore recommended that instructors consider creating a social, teaching, and cognitive presence when designing and facilitating online graded discussions.

6. Limitations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Alqurashi, E. Predicting student satisfaction and perceived learning within online learning environments. Distance Educ. 2019, 40, 133–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erlangga, D.T. Student Problems in Online Learning: Solutions to Keep Education Going On. J. Engl. Lang. Teach. Learn. 2022, 3, 21–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, L.V.; Clairmont, D.; Cox, S. Knowledge and attitudes of criminal justice professionals in relation to Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder. Can. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2008, 15. [Google Scholar]

- Banna, J.; Lin, M.-F.G.; Stewart, M.; Fialkowski, M.K. Interaction matters: Strategies to promote engaged learning in an online introductory nutrition course. J. Online Learn. Teach. 2015, 11, 249–261. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, Z.; Li, M. A bibliometric analysis of Community of Inquiry in online learning contexts over twenty-five years. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2022, 27, 11669–11688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, J.; Kim, C. Guidelines for facilitating the development of learning communities in online courses. J. Comput. Assist. Learn. 2014, 30, 220–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, J.C.; Maeda, Y.; Lv, J.; Caskurlu, S. Social presence in relation to students’ satisfaction and learning in the online environment: A meta-analysis. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2017, 71, 402–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padayachee, P.; Campbell, A.L. Supporting a mathematics community of inquiry through online discussion forums: Towards design principles. Int. J. Math. Educ. Sci. Technol. 2022, 53, 35–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stronge, J.H. Qualities of Effective Teachers; ASCD: Alexandria, VA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Mehall, S. Purposeful Interpersonal Interaction in Online Learning: What Is It and How Is It Measured? Online Learn. 2020, 24, 182–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenny, A. Online learning: Enhancing nurse education? J. Adv. Nurs. 2002, 38, 127–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, M.G. Three types of interaction. Am. J. Open Distance Learn. 1989, 3, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, A.Y.; Tian, S.W.; Vogel, D.; Kwok, R.C.-W. Can learning be virtually boosted? An investigation of online social networking impacts. Comput. Educ. 2010, 55, 1494–1503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouhnik, D.; Marcus, T. Interaction in distance-learning courses. J. Assoc. Inf. Sci. Technol. 2006, 57, 299–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Den Berg, G. Context matters: Student experiences of interaction in open distance learning. Turk. Online J. Distance Educ. 2020, 21, 223–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, E.T. Using Debate in an Online Asynchronous Social Policy Course. Online Learn. 2019, 23, 21–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baber, H. Determinants of Students’ Perceived Learning Outcome and Satisfaction in Online Learning during the Pandemic of COVIDJ. Educ. E Learn. Res. 2020, 7, 285–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowan, L.M.; Jin, Y. Conversations that count in online student engagement–a case study. In Proceedings of the 39th International Conference on Innovation, Practice and Research in the Use of Educational Technologies in Tertiary Education, Sydney, NSW, Australia, 4–7 December 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, K.; Tang, J.; Roll, I.; Fels, S.; Yoon, D. The impact of artificial intelligence on learner–instructor interaction in online learning. Int. J. Educ. Technol. High. Educ. 2021, 18, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zheng, B.; Tian, Y. An exploratory study of English-language learners’ text chat interaction in synchronous computer-mediated communication: Functions and change over time. Comput. Assist. Lang. Learn. 2022, 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghazal, S.; Al-Samarraie, H.; Wright, B. A conceptualization of factors affecting collaborative knowledge building in online environments. Online Inf. Rev. 2020, 44, 62–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razali, S.N.; Ahmad, M.H.; Noor, H.A.M. Implications of Learning Interaction in Online Project Based Collaborative Learning. J. Comput. Theor. Nanosci. 2020, 17, 681–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephens, G.E.; Roberts, K.L. Facilitating collaboration in online groups. J. Educ. Online 2017, 14. [Google Scholar]

- Lieberman, M. Discussion boards: Valuable? Overused? discuss. Inside High. Ed. 2019, 27. [Google Scholar]

- Qureshi, M.A.; Khaskheli, A.; Qureshi, J.A.; Raza, S.A.; Yousufi, S.Q. Factors affecting students’ learning performance through collaborative learning and engagement. Interact. Learn. Environ. 2023, 31, 2371–2391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiock, H. Designing a Community of Inquiry in Online Courses. Int. Rev. Res. Open Distrib. Learn. 2020, 21, 134–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Lima, D.P.; Gerosa, M.A.; Conte, T.U.; de Netto, J.F.M. What to expect, and how to improve online discussion forums: The instructors’ perspective. J. Internet Serv. Appl. 2019, 10, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrison, D.R.; Arbaugh, J. Researching the community of inquiry framework: Review, issues, and future directions. Internet High. Educ. 2007, 10, 157–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrison, D.R.; Anderson, T.; Archer, W. Critical Inquiry in a Text-Based Environment: Computer Conferencing in Higher Education. Internet High. Educ. 2000, 2, 87–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrison, D.R.; Anderson, T.; Archer, W. The first decade of the community of inquiry framework: A retrospective. Internet High. Educ. 2010, 13, 5–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Annand, D. Social presence within the community of inquiry framework. Int. Rev. Res. Open Distrib. Learn. 2011, 12, 40–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Dheleai, Y.M.; Tasir, Z.; Al-Rahmi, W.M.; Al-Sharafi, M.A.; Mydin, A. Modeling of Students Online Social Presence on Social Networking Sites and Academic Performance. Int. J. Emerg.a Technol. Learn. 2020, 15, 56–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzolini, M.; Maddison, S. When to jump in: The role of the instructor in online discussion forums. Comput. Educ. 2007, 49, 193–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, T.; Rourke, L.; Garrison, R.; Archer, W. Assessing Teaching Presence in a Computer Conferencing Context. Online Learn. J. 2019, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Law, K.M.; Geng, S.; Li, T. Student enrollment, motivation and learning performance in a blended learning environment: The mediating effects of social, teaching, and cognitive presence. Comput. Educ. 2019, 136, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giacumo, L.A.; Savenye, W. Asynchronous discussion forum design to support cognition: Effects of rubrics and instructor prompts on learner’s critical thinking, achievement, and satisfaction. Educ. Technol. Res. Dev. 2020, 68, 37–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Tryon, P.J.S.; Bishop, M. Theoretical foundations for enhancing social connectedness in online learning environments. Distance Educ. 2009, 30, 291–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reid-Searl, K.; Happell, B. Supervising nursing students administering medication: A perspective from registered nurses. J. Clin. Nurs. 2012, 21, 1998–2005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merriam, S.B. Introduction to Qualitative Research. Qualitative Research in Practice: Examples for Discussion and Analysis; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2002; Volume 1, pp. 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Simons, H. Case Study Research in Practice; SAGE: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noble, H.; Heale, R. Triangulation in research, with examples. Evid. Based Nurs. 2019, 22, 67–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bans-Akutey, A.; Tiimub, B.M. Triangulation in Research. Acad. Lett. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J.W. Reflections on the MMIRA the future of mixed methods task force report. J. Mix. Methods Res. 2016, 10, 215–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMillan, D.W.; Chavis, D.M. Sense of community: A definition and theory. J. Community Psychol. 1986, 14, 6–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simelane-Mnisi, S. Role and importance of ethics in research. In Ensuring Research Integrity and the Ethical Management of Data; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2018; pp. 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Participant | First/Second Year | Male/Female |

|---|---|---|

| P1 | First | F |

| P2 | Second | M |

| P3 | First | M |

| P4 | Second | F |

| P5 | First | F |

| P6 | First | M |

| P7 | First | M |

| P8 | First | F |

| P9 | First | F |

| P10 | First | M |

| P11 | First | M |

| Themes | Sub-Themes |

|---|---|

| Social Presence | Lively debates Collaboration and being part of a learning community |

| Teaching Presence | Clearly stated guidelines Highly structured content |

| Cognitive Presence | Learning journey |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mudau, P.K.; Van den Berg, G. Guidelines for Supporting a Community of Inquiry through Graded Online Discussion Forums in Higher Education. Educ. Sci. 2023, 13, 963. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci13090963

Mudau PK, Van den Berg G. Guidelines for Supporting a Community of Inquiry through Graded Online Discussion Forums in Higher Education. Education Sciences. 2023; 13(9):963. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci13090963

Chicago/Turabian StyleMudau, Patience Kelebogile, and Geesje Van den Berg. 2023. "Guidelines for Supporting a Community of Inquiry through Graded Online Discussion Forums in Higher Education" Education Sciences 13, no. 9: 963. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci13090963

APA StyleMudau, P. K., & Van den Berg, G. (2023). Guidelines for Supporting a Community of Inquiry through Graded Online Discussion Forums in Higher Education. Education Sciences, 13(9), 963. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci13090963