Teaching Biodiversity: Towards a Sustainable and Engaged Education

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- i.

- What are teachers’ representations of the concept of biodiversity?

- ii.

- Are teachers’ representations influenced by the thematic content and educational values present in school curricula relating to biodiversity?

- iii.

- To what extent is biodiversity education perceived as a means of student development and personal well-being by the surveyed teachers?

- iv.

- What pedagogical practices do science teachers adopt when introducing the concept of biodiversity to their students?

- v.

- What influence do socio-professional factors have on their representations?

2. Theoretical Context

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Research Context

3.2. Sample

3.3. Sample Characteristics

- fairly long experience in the field of teaching and education, taking into account the seniority factor in professional experience: significant teaching experience more than 10 years (87% in primary school and 66% in secondary school);

- adequate diploma teacher training that qualifies them to work in the field of teaching and education: 82% for the primary cycle sample and 94% for the secondary cycle sample;

- the majority of teachers (32%) in the primary cycle hold a bachelor’s degree, and the vast majority of secondary teachers (45%) hold a master’s degree;

- heterogeneity in the specialty of university degrees obtained by primary school teachers (77% other specialty than life and/or earth sciences) and diversity in scientific specialties (82% relating to life and earth sciences) of diplomas obtained by secondary school teachers;

- male gender dominance in both samples: 79% for the primary cycle sample and 63% for the secondary cycle sample;

- the majority of the sample of primary school teachers who responded to the questionnaire are from rural areas (55%) and the majority of secondary school teachers are from urban areas (70%).

3.4. Research Tools

- A questionnaire: We designed a questionnaire with 7 questions on socio-cultural characteristics, 1 question about the possibility of visiting teachers in the classroom for interviews while ensuring the anonymity of their data, and 5 closed-ended questions related to the biodiversity concept and its teaching. Teachers were asked to provide a means of contact, such as a phone number or email address, to facilitate the scheduling of subsequent interviews. Responses were recorded using predefined categories (“yes” or “no”; “agree” or “undecided” or “disagree”). The questionnaire data were entered and organized in a data collection table using Excel 2019 software (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA).

- Individual interviews: We conducted individual interviews with 11 teachers who agreed to participate in the study. The interviews were guided by open-ended questions, allowing teachers to express themselves freely and deepen their reflections. The questions aimed to deepen the responses provided in the questionnaire and to obtain more detailed information on their representations of biodiversity and their views on its teaching.

3.5. Data Collection and Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Conceptual Representations of the Surveyed Teachers Relating to the Concept of “Biodiversity”

4.2. Conception of Biodiversity in Primary and Secondary School Curricula

- In the primary cycle, the most present dimensions in the curricula are “classification” and “ecology”, both at 35%. This suggests that these aspects of biodiversity are addressed meaningfully in primary school curricula. The dimension of “human activities and behaviors” is also present at a significant level of 29%. The “genetic” and “evolution” dimensions are considered more advanced for elementary school children. “Genetic” is addressed later in the second year of secondary middle school.

- In secondary education, there is a more balanced distribution of biodiversity dimensions. The genetic dimension is present at a percentage of 26%, indicating a greater inclusion of this concept in secondary school curricula. The dimensions of ecology and human activities and behaviors are present at percentages of 12% and 26% respectively. The dimension of evolution is also present at a percentage of 18%.

4.3. Characteristics of the Concept of “Biodiversity” According to the Opinion of the Surveyed Teachers

4.3.1. The Concept of “Biodiversity” in School Curricula According to Surveyed Teachers

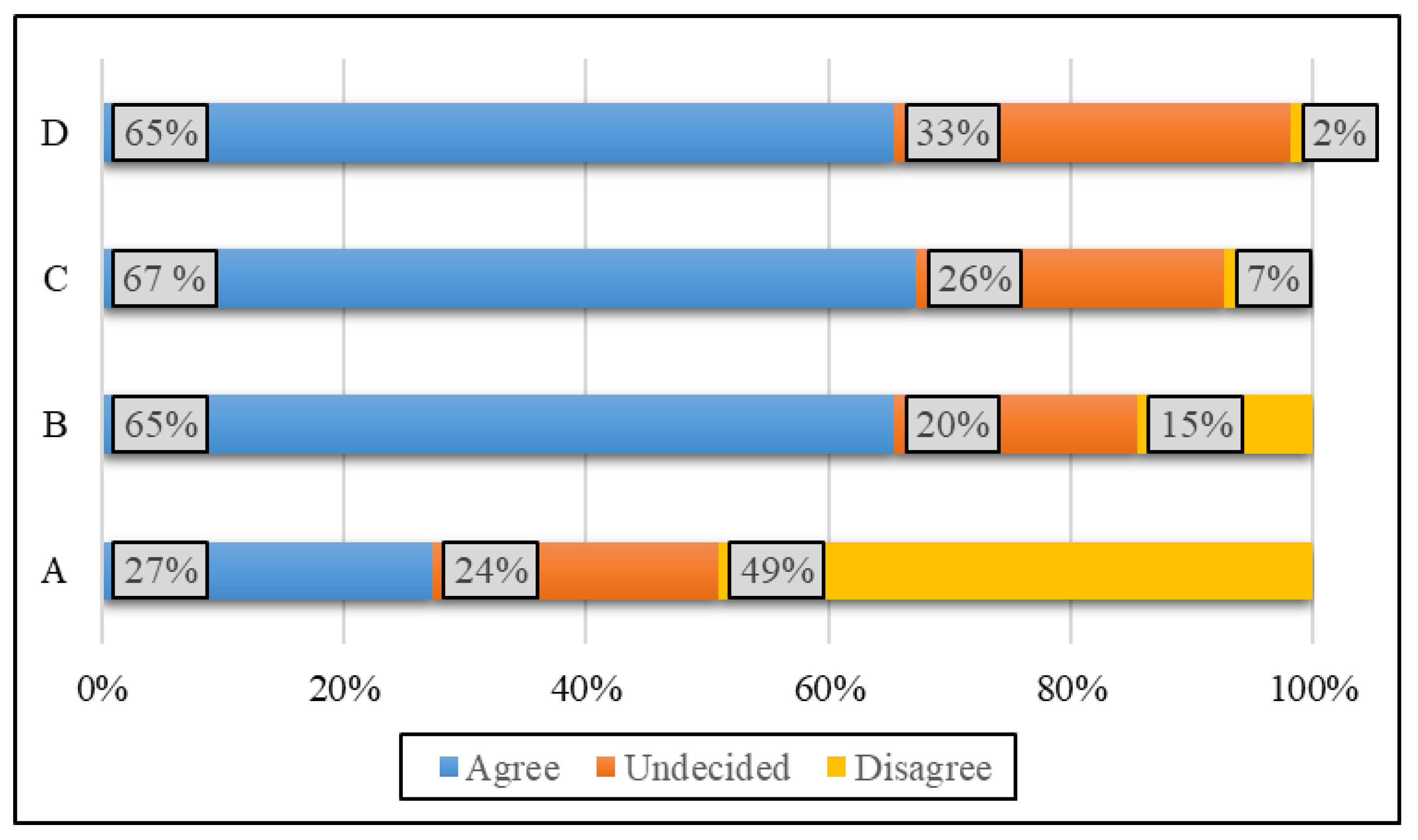

- “Knowledge” corresponds to a proposal “A”. This is theoretical understanding and expertise in various areas related to biodiversity.

- “Skills” (how to do) can be associated with a proposal “B”. This includes the practical skills and interpersonal collaboration needed to take concrete action for biodiversity protection.

- The “strategic competencies” (how to be) correspond to a proposal “C”. This refers to the ability to integrate many parameters into decision making and the management of interactions between man and nature.

- “Personal qualities” (how to act) can be linked to a proposal “D”. This encompasses attitudes, values, and behaviors that promote awareness of the sustainability of the species and its evolution.

4.3.2. Importance of Teaching the Concept of Biodiversity According to Surveyed Teachers

- Teachers agree: The majority of teachers (65%) agree on the importance of the concept of biodiversity compared to other concepts in the school curriculum. This suggests that they recognize the value of teaching biodiversity and consider it worthy of special attention in the context of education.

- Teachers disagree: A small percentage of teachers (11%) disagree on the importance of biodiversity compared to other concepts. Their specific reasons for disagreement may be due to different pedagogical perspectives or different educational priorities.

- Indifferent teachers: Another interesting aspect is that 35% of teachers say they are indifferent to the importance of biodiversity compared to other concepts. This could reflect a lack of knowledge or particular interest in the topic of biodiversity, or perhaps a perception that other concepts might be more important or prioritized.

4.3.3. Main Means of Acquiring Information about the Concept of “Biodiversity” among the Surveyed Teachers

- acquisition of information on biodiversity through educational programs (39% of surveyed teachers): these teachers report relying on specific educational resources related to biodiversity, such as textbooks, university curricula, or their professional training;

- acquiring information on biodiversity in a professional setting (20% of surveyed teachers): this could include, according to them, exchanges with other teachers and training provided in the framework of associations of teachers with the disciplines of life and earth sciences;

- acquiring information on biodiversity through personal research (41% of surveyed teachers): they report turning to independent sources such as books, scientific articles, websites, or visits to sites and museums during their travels to enrich their knowledge on the subject.

4.4. Framework of Reference Values for Educational Practices in Biodiversity Education

- Proposal A’ emphasizes the social value of this teaching. By understanding biodiversity and its importance, students can become aware of their role as responsible citizens committed to the preservation of biodiversity.

- Proposal B’ reflects the ethical value of biodiversity education. By understanding the issues and consequences of biodiversity loss, students are encouraged to adopt environmentally responsible behaviors and make ethical decisions to preserve biodiversity.

- Proposal C’ represents the cognitive value of biodiversity education. By encouraging students to debate, discuss, and challenge different perspectives and issues related to biodiversity, this approach promotes the development of their cognitive skills and critical thinking.

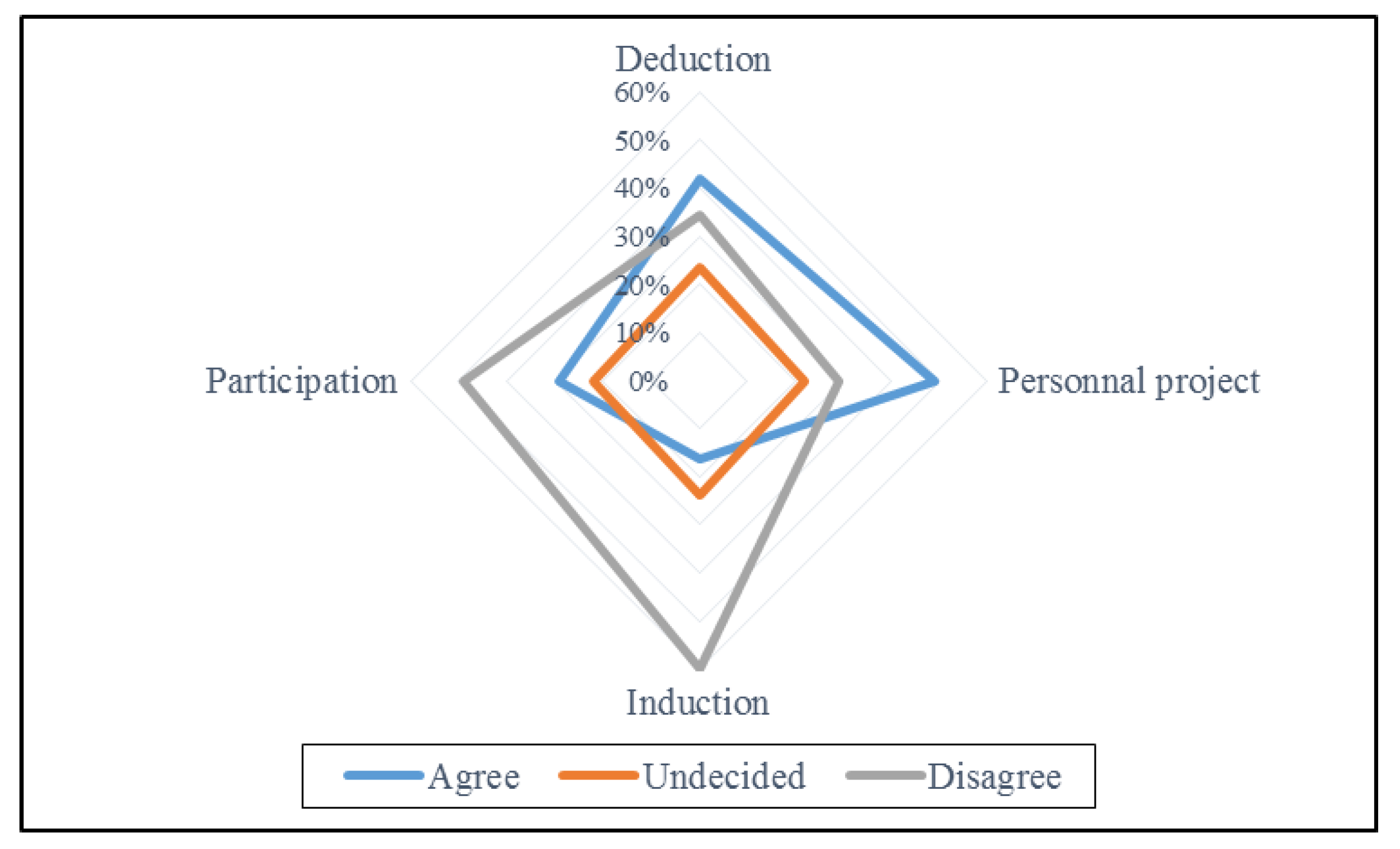

- the majority of teachers (55%) do not consider teaching biodiversity to have a direct impact on the students’ development and personal well-being (proposal A’);

- although the majority of teachers (51%) do not support proposal B’, a significant percentage (33%) recognize the importance of acquiring knowledge about biodiversity conservation to induce behavioral change in students;

- although proposal C’ has the highest percentage of agreement, almost half of the teachers (44%) do not support the idea that biodiversity education can provide training focused on critical thinking and debate.

4.5. Teaching-Learning Approaches Preferred by the Surveyed Teachers to Teach the Concept of “Biodiversity”

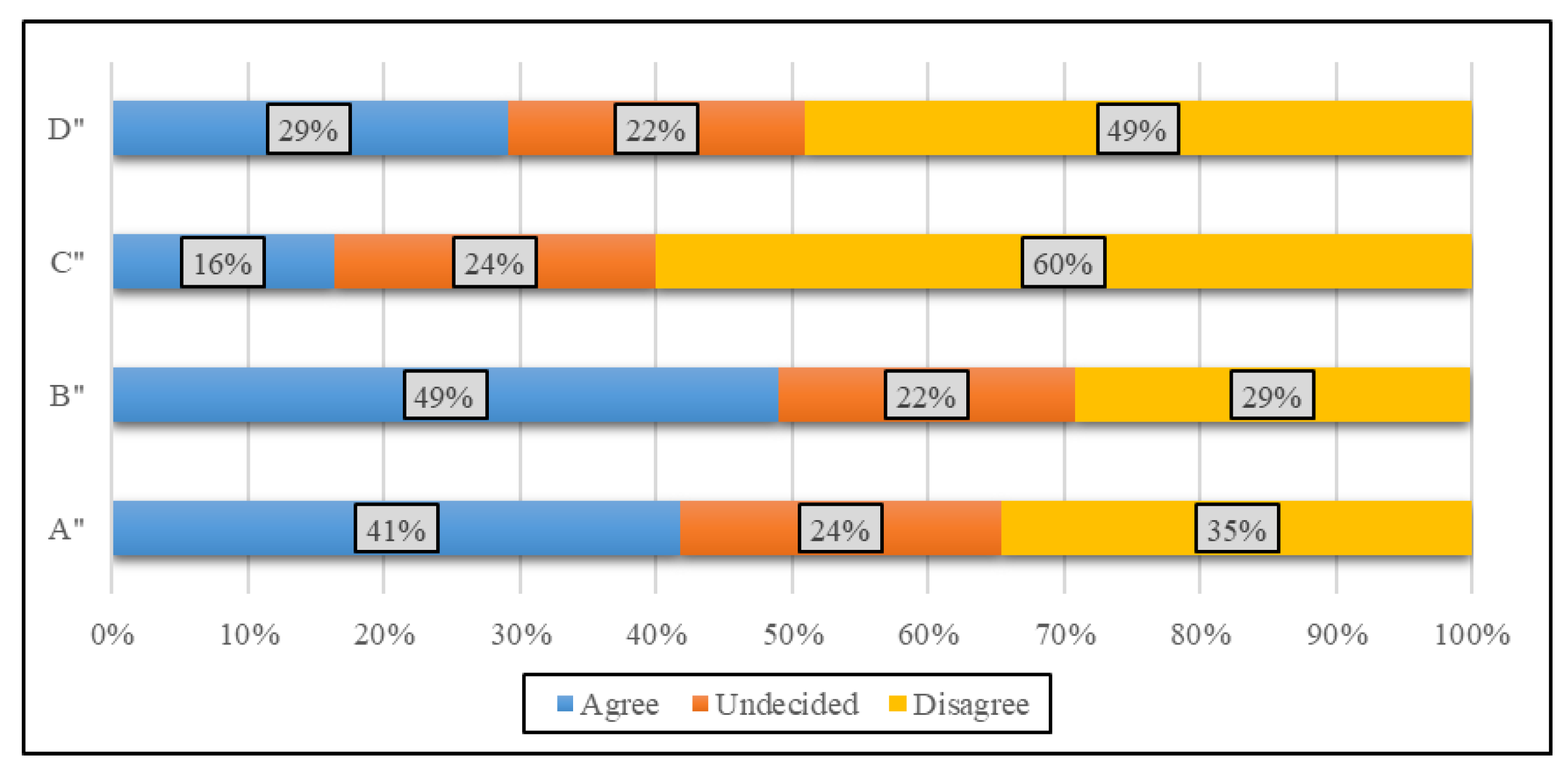

- Proposal A”: The results indicate that 41% of teachers consider the deductive approach to teaching the concept of biodiversity, through classroom activities, as a choice approach. On the other hand, a significant proportion of teachers express their disagreement and encourage the inclusion of other approaches to work on biodiversity in the classroom.

- Proposal B”: 49% of teachers agree with the idea of carrying out personal biodiversity research projects outside the classroom, 22% are indifferent, and 29% disagree. Thus, the majority of teachers (49%) support this approach, which suggests an interest in literature review.

- Proposal C”: The overwhelming majority (60%) of teachers do not support the inclusion of school projects as an approach to students’ learning about biodiversity. They state that school projects are not interested in the theme of environmental education and sustainable development of the student but rather in the field of students’ tutoring for the subjects of mathematics and foreign languages.

- Proposal D”: 29% of teachers agree with students’ participation in extracurricular activities related to biodiversity within school clubs, 22% are indifferent, and 49% disagree. The majority of teachers (49%) express their disagreement with this inductive method, which requires their commitment to mentoring practical experiences and field investigations. This requires great responsibility, means, and materials that the teachers should take charge of.

4.6. Impact of Socio-Professional and Cultural Factors on the Epistemological Status Associated with Biodiversity

4.6.1. Seniority

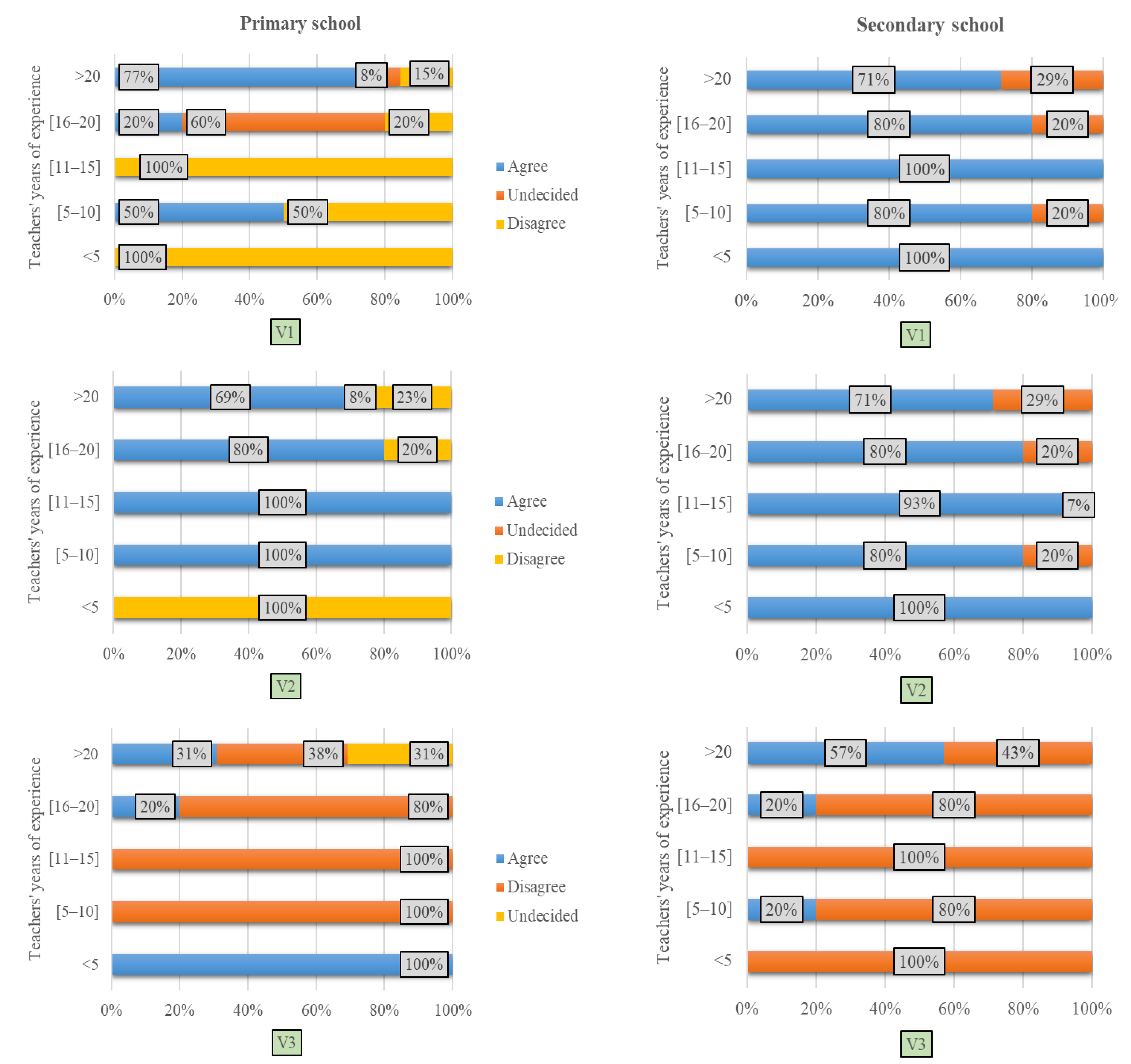

- teachers’ seniority can influence their perception and understanding of biodiversity;

- more experienced teachers seem to have more nuanced opinions and may be more inclined to question or be undecided on certain proposals;

- proposals V1 and V2 of the definition of biodiversity, for secondary school teachers, seem to be more widely accepted, regardless of seniority. However, the V3 proposal is causing more differences of opinion, with a tendency to be less accepted, especially among teachers with less experience.

4.6.2. Diploma Obtained

- Proposal V1: Teachers with a high school diploma show mixed opinions, with an equitable split between agreement, indecision, and disagreement. Teachers with an associate degree mostly agree with the proposal, while those with a bachelor’s degree show a majority of disagreements. On the other hand, teachers with a master’s degree or doctorate are unanimous in their agreement with the proposal.

- Proposal V2: Teachers with a high school diploma show a majority of disagreements with the proposal. On the other hand, teachers with an associate degree are all in agreement. Teachers with a bachelor’s degree show a majority of agreement, while those with a master’s degree also show a majority of agreement. Teachers with a Ph.D. agree with the proposal.

- Proposal V3: Teachers with a high school diploma show a majority of disagreements with the proposal. Elementary school teachers with an associate degree mostly disagree, and those in high school mostly agree, while those with a bachelor’s degree show a majority of disagreements. Teachers with a master’s degree show some agreement, while those with a doctorate mostly disagree with the proposal.

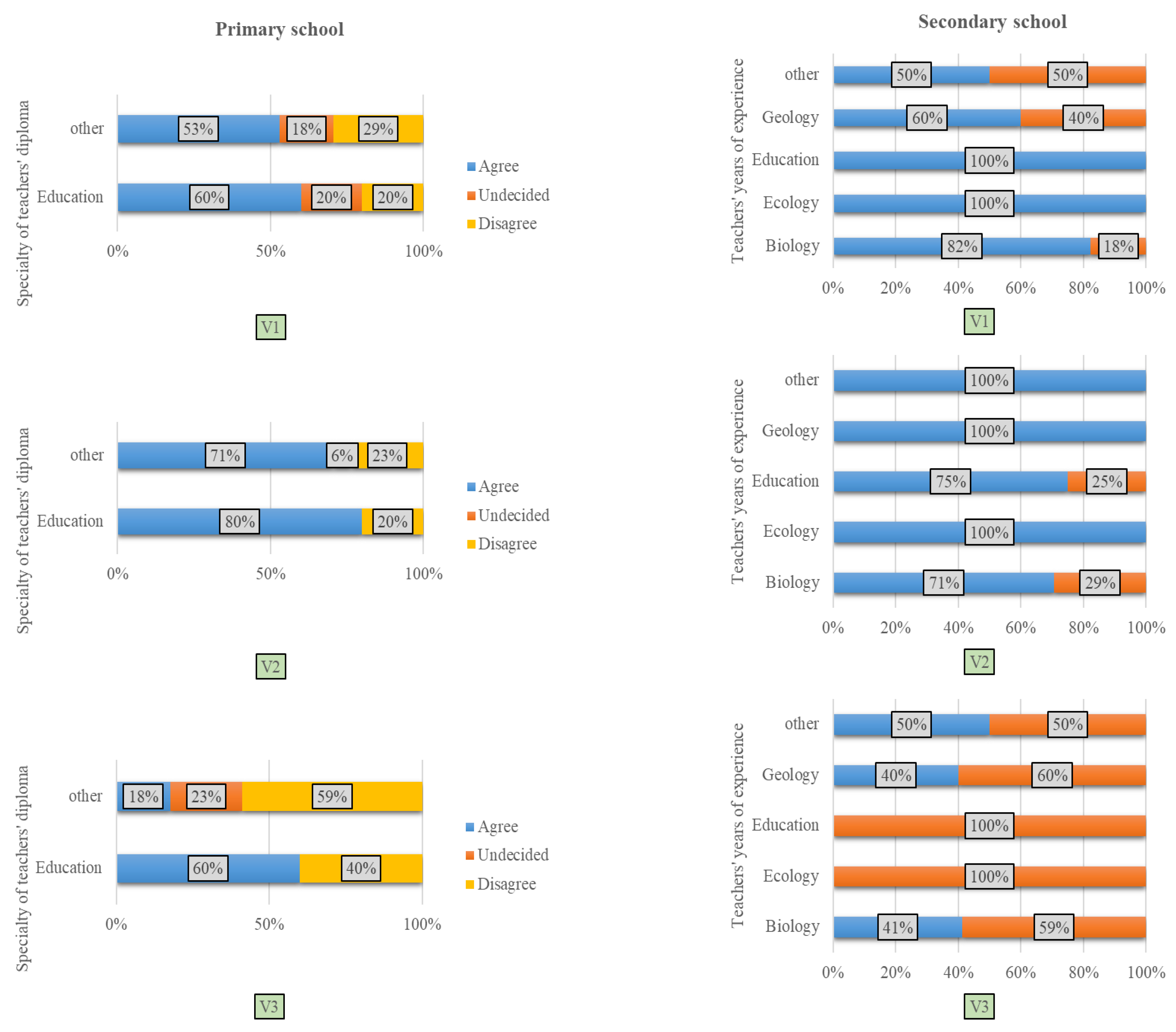

4.6.3. Specialty of the Diploma

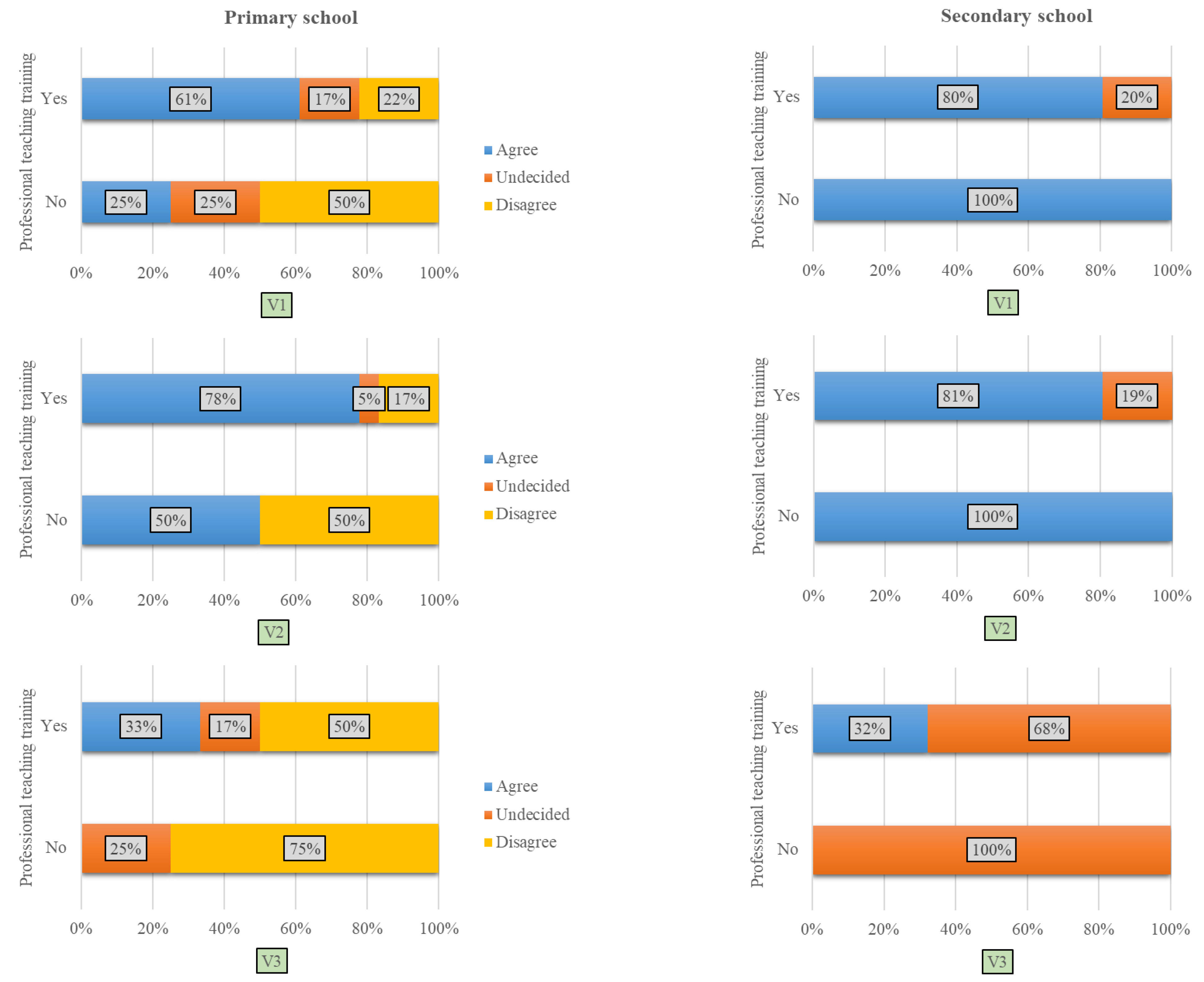

4.6.4. Professional Training

5. Discussion

5.1. Teachers’ Representations of Biodiversity

5.2. Teachers’ Perceptions of the Importance of Biodiversity Education

5.3. Teachers’ Choices and Perceptions of Teaching Approaches Related to the Concept of “Biodiversity”

5.4. Influence of Teachers’ Professional Characteristics on the Development of Their Representations of the Concept of “Biodiversity”

- Seniority: Seniority can play an important role in teachers’ representations. According to social learning theory [42], individuals acquire knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors through observation and imitation of others. Thus, older teachers may have been exposed to educational practices that place more emphasis on biodiversity and are therefore more likely to have positive representations of it [29]. This could explain why more experienced teachers show higher percentages of agreement with the survey proposals (Figure 7).

- Diploma: Teachers’ diplomas can influence their representations of biodiversity. Teachers with a degree in education may have taken specific courses or training programs in environmental education, which may reinforce their knowledge and positive attitudes toward biodiversity [43]. On the other hand, teachers with a degree in other specialties may be less exposed to biodiversity concepts and may therefore have less developed representations. This would explain the differences observed between teachers in education and those in other specialties in the survey (Figure 8).

- The specialty of the diploma: The specialty of the degree can also play a role in teachers’ representations. Teachers with a specialty related to biology, ecology, or geology may have a deeper understanding of biodiversity concepts (Figure 9), which may be reflected in more positive representations [29]. On the other hand, teachers who have a different specialty may have limited knowledge of biodiversity, which may explain the lower percentages agreeing with the survey proposals (Figure 9).

- Professional training: The professional training of teachers is a key factor in developing their knowledge and representations of biodiversity. In-service training programs focusing on environmental and biodiversity education can help teachers acquire new knowledge and skills, change their attitudes, and adopt more biodiversity-friendly pedagogical practices [1]. Thus, teachers who have benefited from biodiversity-specific professional training (Figure 10) have more positive representations than those who have not had this opportunity.

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- McDonald, R.I. The effectiveness of conservation interventions to overcome the urban–environmental paradox. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2015, 1355, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cesco, S.; Zara, V.; De Toni, A.F.; Lugli, P.; Evans, A.; Orzes, G. The future challenges of scientific and technical higher education. Tuning J. High. Educ. 2021, 8, 85–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lange, J.M. Education to sustainable development: Factors to think teachers’ training. Carrefours L’éducation 2011, 1, 71–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barthes, A.; Zwang, A.; Alpe, Y. Sous la bannière développement durable, quels rapports aux savoirs scientifiques? OpenEdition J. 2014, 11, 815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kollmuss, A.; Agyeman, J. Mind the Gap: Why do people act environmentally and what are the barriers to pro-environmental behaviour? Environ. Educ. Res. 2002, 8, 239–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cormier-Salem, M.-C. Représentations Sociales de La Biodiversité et Implications Pour La Gestion et La Conservation [Social Representations of Biodiversity and Implications for Management and Conservation]. Sci. Conserv. 2014, 2, 95–106. [Google Scholar]

- Lhoste, Y.; Voisin, C. Repères Pour l’enseignement de La Biodiversité En Classe de Sciences. RDST 2013, 7, 107–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shulman, L. Knowledge and Teaching:Foundations of the New Reform. Harv. Educ. Rev. 1987, 57, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yli-Panula, E.; Jeronen, E.; Lemmetty, P.; Pauna, A. Teaching Methods in Biology Promoting Biodiversity Education. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, E.O. The Diversity of Life. J. Leis. Res. 1997, 29, 476. [Google Scholar]

- Nations, U. United Nations Convention on Biological Diversity. Aust. Zool. 1992, 28, 88–103. [Google Scholar]

- Reaka-kudla, M.L.; Wilson, D.E.; Edward, O.; Henry, A.J. Biodiversity II: Understanding and Protecting Our Biological Resources; Joseph Henry Press: Washington, DC, USA, 1997; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Norse, E.A.; McManus, R.E. Ecology and Living Resources: Biological Diversity; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Barbault, R. Biodiversity: Stakes and opportunities. Nat. Resour. 1995, 31, 18–26. [Google Scholar]

- Audrin, C. How is biodiversity understood in compulsory education textsbooks? A lexicographic analysis of teaching programs in the French-speaking part of Switzerland. Environ. Educ. Res. 2022, 29, 1056–1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilinc, A.; Yeşiltaş, N.K.; Kartal, T.; Demiral, Ü.; Eroǧlu, B. School Students’ Conceptions about Biodiversity Loss: Definitions, Reasons, Results and Solutions. Res. Sci. Educ. 2013, 43, 2277–2307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mace, G.M.; Norris, K.; Fitter, A.H. Biodiversity and ecosystem services: A multilayered relationship. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2012, 27, 19–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Voisin, C. L’éducation à l’environnement: l’idée de neutralité entre simplisme, positivisme et relativisme. Éducation Social. 2018, 48, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barthes, A.; Tebbaa, O. Savoirs et conflits de savoirs en éducation à l’environnement et au développement durable: Le cas des dispositifs éco-orientés UNESCO [Knowledge and knowledge conflicts in environmental education and sustainable development: The case of UNESCO-oriented]. OpenEdition J. 2019, 15, 3657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeronen, E.; Palmberg, I.; Yli-Panula, E. Teaching Methods in Biology Education and Sustainability Education Including Outdoor Education for Promoting Sustainability—A Literature Review. Educ. Sci. 2016, 7, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramanathan, S.; Ketpichainarong, W.; Luan, H.; Chodkowski, N.; O’Grady, P.M.; Specht, C.D. Active Learning Strategies for Biodiversity Science. Front. Educ. 2022, 244, 849300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Can, I.; Inel Ekici, D. Science learning through problems in gifted and talented education: Reflection and conceptual learning. Educ. Stud. 2021, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramade, F. Qu’entend-t-on par Biodiversité et quels sont les problématiques et les problèmes inhérents à sa conservation? Bull. De La Société Entomol. De France 1994, 99, 7–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, K.; Maynard, N.; Berry, A.; Stephenson, T.; Spiteri, T.; Corrigan, D. Principles of Problem-Based Learning (PBL) in STEM Education: Using Expert Wisdom and Research to Frame Educational Practice. Educ. Sci. 2022, 12, 728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleury, B.; Fabre, M. La pédagogie sociale: Inculcation ou problématisation? L’exemple du développement durable dans l’enseignement agricole français. OpenEdition J. 2006, 1, 3593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sofianidis, A.; Kallery, M. An Insight into Teachers’ Classroom Practices: The Case of Secondary Education Science Teachers. Educ. Sci. 2021, 11, 583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altet, M. To combine research works on teaching practices and on training teachers: A double scientific and transformative function of Educational Sciences. Sci. De L’education Pour L’ere Nouv. 2019, 52, 29–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Astolfi, J.P.; Darot, É.; Ginsburger-Vogel, Y.; Toussaint, J. Chapitre 15. Représentation (ou conception). Mots Clés de La Didac. Des Sci. 2008, 147–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tekin, N.; Aslan, O. Analysis of Pre-Service Science Teachers’ Biodiversity Images according to Sustainable Environmental Awareness. Present Environ. Sustain. Dev. 2022, 16, 63–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aubertin, C.; Boisvert, V.; Vivien, F.D. La construction sociale de la question de la biodiversité. Nat. Sci. Soc. 1998, 6, 7–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilgin, H.; Aykac, N. Pre-Service Teachers’ Teaching-Learning Conceptions and Their Attitudes towards Teaching Profession. Educ. Process Int. J. 2016, 5, 139–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, B.B.; Schnack, K. The Action Competence Approach in Environmental Education. Environ. Educ. Res. 2006, 3, 163–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barroca-Paccard, M.; Orange Ravachol, D.; Gouyon, P.-H. Education au développement durable et diversité du vivant: La notion de biodiversité dans les programmes de sciences de la vie et de la terre. Penser L’éducation 2013, 1, 9. [Google Scholar]

- Idbabou, A.; Sidi, O.J.; Ben, M.; El, B.; Sidi, B.; Sidi, M.L. Education for Sustainable Development and Teaching Biodiversity in the Classroom of the Sciences of The Moroccan School System: A case study based on the Ministry’s grades and school curricula from primary to secondary school and qualifying. Br. J. Educ. 2020, 8, 13–21. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, E. Biodiversity; National Academy Press: Washington, DC, USA, 1988; pp. 3–18. [Google Scholar]

- Picanço, A.; Arroz, A.M.; Amorim, I.R.; Matos, S.; Gabriel, R. Teachers’ Perspectives and Practices on Biodiversity Web Portals as an Opportunity to Reconnect Education with Nature. Environ. Conserv. 2021, 48, 25–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araujo, L.A.L.; Santana, C.M.B.; Franzolin, F. Brazilian Teachers’ Views and Experiences Regarding Teaching Biodiversity in an Evolutionary and Phylogenetic Approach. Evol. Educ. Outreach 2023, 16, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merritt, E.; Hale, A.; Archambault, L. Changes in Pre-Service Teachers’ Values, Sense of Agency, Motivation and Consumption Practices: A Case Study of an Education for Sustainability Course. Sustainability 2018, 11, 155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmberg, I.; Hofman-Bergholm, M.; Jeronen, E.; Yli-Panula, E. Systems Thinking for Understanding Sustainability? Nordic Student Teachers’ Views on the Relationship between Species Identification, Biodiversity and Sustainable Development. Educ. Sci. 2017, 7, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corral-Verdugo, V.; Bonnes, M.; Tapia-Fonllem, C.; Fraijo-Sing, B.; Frías-Armenta, M.; Carrus, G. Correlates of pro-sustainability orientation: The affinity towards diversity. J. Environ. Psychol. 2009, 29, 34–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MEN. La Charte Nationale d’Education et de Formation [National Charter for Education and Training: Constant Foundations]. 1999. Available online: https://www.men.gov.ma/en/Pages/CNEF_Fond-constants.aspx (accessed on 28 June 2023).

- Rosenstock, I.M.; Strecher, V.J.; Becker, M.H. Social Learning Theory and the Health Belief Model. Sage J. 1988, 15, 175–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tilbury, D. Environmental Education for Sustainability: Defining the new focus of environmental education in the 1990s. Environ. Educ. Res. 2006, 1, 195–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| (a) | |||||

| Female | Male | ||||

| Primary School | 21% | 79% | |||

| Secondary School | 37% | 63% | |||

| (b) | |||||

| Urban | Rural | ||||

| Primary School | 45% | 55% | |||

| Secondary School | 70% | 30% | |||

| (c) | |||||

| <5 | [5–10] | [11–15] | [16–20] | >20 | |

| Primary School | 5% | 9% | 5% | 22% | 59% |

| Secondary School | 19% | 15% | 9% | 15% | 42% |

| (d) | |||||

| High School Diploma | Associate Degree | Bachelor‘s Degree | Master‘s Degree | Doctoral Degree | |

| Primary School | 26% | 9% | 32% | 28% | 5% |

| Secondary School | 0% | 19% | 30% | 45% | 6% |

| (e) | |||||

| Biology | Geology | Ecology | Education | Other | |

| Primary School | 0% | 0% | 0% | 23% | 77% |

| Secondary School | 52% | 15% | 15% | 12% | 6% |

| (f) | |||||

| Yes | No | ||||

| Primary School | 82% | 18% | |||

| Secondary School | 94% | 6% | |||

| Categories of Respondents | Average Value (Primary School) | Average Value (Secondary School) |

|---|---|---|

| V1 | 2.36 | 2.60 |

| V2 | 2.54 | 2.55 |

| V3 | 1.72 | 1.51 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Id Babou, A.; Selmaoui, S.; Alami, A.; Benjelloun, N.; Zaki, M. Teaching Biodiversity: Towards a Sustainable and Engaged Education. Educ. Sci. 2023, 13, 931. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci13090931

Id Babou A, Selmaoui S, Alami A, Benjelloun N, Zaki M. Teaching Biodiversity: Towards a Sustainable and Engaged Education. Education Sciences. 2023; 13(9):931. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci13090931

Chicago/Turabian StyleId Babou, Asma, Sabah Selmaoui, Anouar Alami, Nadia Benjelloun, and Moncef Zaki. 2023. "Teaching Biodiversity: Towards a Sustainable and Engaged Education" Education Sciences 13, no. 9: 931. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci13090931

APA StyleId Babou, A., Selmaoui, S., Alami, A., Benjelloun, N., & Zaki, M. (2023). Teaching Biodiversity: Towards a Sustainable and Engaged Education. Education Sciences, 13(9), 931. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci13090931