Abstract

Background: The Doctor of Philosophy (Ph.D.) is a doctoral research degree that represents the highest level of academic qualification awarded by universities. It is expected that professionals holding a Ph.D. degree can target higher-paying jobs. However, little is known about the real correlation between Ph.D. holders and professional career development. For the first time, a study was undertaken among Ph.D. graduates from the Complutense University of Madrid (UCM), one of the largest universities in Spain, to understand the value of the Ph.D. on students’ satisfaction and career prospects. Methods: An anonymous questionnaire, created through Google Forms with three sections (sociodemographic data, academic data about doctoral studies, and employment status), was sent to Ph.D. graduates from UCM between 2015 and 2022. Results: A total of 107 Ph.D. graduates participated in this study. Responders felt that the Ph.D. degree has positively impacted their soft skills development and capability for constant learning but has minimal impact on their overall employability, although the employment rate was 94%. Most of the jobs undertaken by the Ph.D. holders were linked to academic research areas and were located in Spain, with salaries ranging between 14,000 and 50,000 EUR. Conclusions: Universities should implement novel policies at the Ph.D. level to ensure students are not only exposed to the scientific environment but are also prepared and qualified for highly skilled jobs. It is key to creating a community along with the private sector and providing the necessary tools for fostering Ph.D. students’ satisfaction and career prospects.

1. Introduction

The Doctor of Philosophy (Ph.D.) is a doctoral research degree that represents the highest level of academic qualification awarded by universities. The Ph.D. degree is obtained after the successful completion of the official doctoral studies, also known as the third cycle of university studies, in which the student acquires competencies and research skills related to a specific area [1]. The number of students enrolled in Ph.D. studies has increased in the past decades [2,3,4]. For instance, there are about 650,000 Ph.D. students in the European Union alone [5]. The Ph.D. journey implies integration into the research and academic environment along with personal and professional development and integration into the job market. During doctoral training, it is expected that the student goes through a transition from the dependent role to the professional role (independence) [6]. A Ph.D. program can be demanding but also rewarding. On the one hand, completing Ph.D. studies requires a significant investment of quality time and free time over a few years [7]. Additionally, the Doctoral Thesis can translate into stress, anxiety, sadness, weariness, and a higher risk of burnout, even depression [8]. The Ph.D. experience, on the other hand, also provides advantages, such as the development of specific expertise-related skills, the capacity to work in a team context, and the enhancement of communication skills [9]. All these factors contribute to the increased demand for Ph.D. graduates in the labor market. A Ph.D. is designed to produce highly qualified graduates who are essential for a nation’s technological advancement and innovation and, ultimately, for its economic growth [10]. Most students pursue doctoral degrees because they believe they will obtain better work opportunities than bachelor’s and master’s degree holders [11].

The learning model of doctoral students is mainly applied to the research and academic area, although the doctoral degree is highly valued in other work contexts such as private non-profit sectors, business enterprises, and public institutions [12,13]. For instance, the number of doctoral graduates working in non-academic and research areas (i.e., private sector and governmental institutions) is high in many countries such as Finland (68%), the United Kingdom (53%), the United States (60.4%), and Spain (57.3%) [14,15,16,17].

Ph.D. studies have a direct connection with high employment rates. In Spain, the rate of unemployed students with a doctoral degree is just 13% compared to 20% for university graduates [18], but although a Ph.D. is the highest postgraduate educational degree, it does not always correlate with high-paying jobs, as in many cases, Ph.D. graduates are considered overqualified for their employment. According to the report “Education at a Glance. OECD 2019”, 48% of Ph.D. holders are overqualified for the job they performed [19]. This raises the following question: ‘Are there too many Ph.D. holders in the job market?’ [20]. Additionally, there is a lack of information regarding the employability patterns of doctoral graduates [21,22,23], as well as the time required for Ph.D. holders to find a job, the type of job, the degree of specialization required, and the salary. A key point of research is to understand the current Ph.D. employment rates, the degree of job satisfaction, and the relationship between the skillset required for the job compared to the skillset acquired during the Ph.D.

This study seeks to analyze, for the first time, the Ph.D. market entry and the degree of students’ satisfaction and professional development of Ph.D. graduates from the Complutense University of Madrid (UCM) (Madrid, Spain) from the years 2015 to 2022.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

This is a longitudinal retrospective observational study to analyze the trends of the training received and the employability rate of Ph.D. graduates from 2015 to 2022. The study was conducted at the Complutense University of Madrid, which is the oldest and largest higher education institution in Spain (position 171 in the QS World University Rankings).

An anonymous questionnaire was created through the Google Forms tool based on previous studies of employability among Spanish university graduates [24,25,26]. There were three sections in the survey. The first section consisted of questions related to the sociodemographic data of the participants. The second section contained questions related to the academic data on doctoral studies. Finally, the third section consisted of questions about the employment status of the participants after doctoral studies and the characteristics of their employment.

Table 1 lists the specific inquiries raised in this questionnaire. The entire questionnaire is available in the Supplementary Materials (Table S1).

Table 1.

Questionnaire completed by the participants of the study. In Likert-scale questions, participants were asked to rate their level of satisfaction with each item from 1 (very dissatisfied) to 5 (very satisfied). * The participants were asked to refer their responses to what they considered to be their primary employment after doctoral studies.

Participation in this study was voluntary. The participants had to provide their informed consent before accessing the questionnaire. The designed survey was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the UCM (Ref. CE_20220721-06_SOC).

2.2. Procedures Used for Disseminating the Questionnaire and Collecting the Data

An email containing a link for the Google questionnaire was sent between 13 October and 7 November 2022 to the alumni of UCM Ph.D. programs who received their doctoral degrees between 2015 and 2022. To ensure anonymity, the UCM Student Observatory contacted the postgraduate study units from each of the 26 schools of UCM. Each school, according to the records, emailed the Ph.D. graduates individually. The acquired data were transferred to an easily accessible Excel spreadsheet to proceed with the statistical and data analysis.

2.3. Sampling Size and Target Population

According to a 90% level of confidence and a 10% maximum permissible error, a sample size of at least 68 participants was established. A total target population of 6558 Ph.D. graduates during 2015–2022 was recorded.

2.4. Data Analysis

According to the area of knowledge of the Ph.D. studies carried out by the participants, they were split into three groups: (i) Ph.D. in Arts, Humanities, and Social or Legal Sciences; (ii) Ph.D. in Engineering, Architecture, or Sciences; and (iii) Ph.D. in Health Sciences. The data obtained from the questionnaire were analyzed globally and per area of knowledge using descriptive statistics. The Chi-squared test was applied to determine whether there were any statistically significant differences between categorical variables. Spearman’s correlation coefficient was used to analyze the correlation between the Likert-type questions related to the satisfaction degree of the participants with their current employment. Using the Mann–Whitney U test, the medians of satisfaction of men and women were compared on a median basis. p-values below 0.05 were regarded as significant. The IBM® SPSS Statistics program, version 27, was used to conduct the statistical analyses.

3. Results

3.1. Sociodemographic Data and Academic Characteristics of the Participants

A total of 107 Ph.D. graduates from UCM during 2015–2022 participated in this study. As shown in Table 2, most participants (54.2%) were female, had a median age of 33 years old, and were Spanish (84.1%).

Table 2.

Sociodemographic and academic characteristics of the Ph.D. graduates included in the study. The data are provided globally and per area of knowledge. Key: Interquartile Range (IQR).

Most of the participants (53.3%) are Ph.D. holders in the area of Health Sciences, primarily in Pharmacy or Biomedical Research (22.8 and 19.3%, respectively). 32.7% of the participants were enrolled in doctoral programs in the areas of Arts, Humanities, and Social or Legal Sciences, primarily in the areas of Law or Education (37.7% and 25.7%, respectively). Finally, 14% of the total participants completed a Ph.D. in Engineering, Architecture, or Sciences, with most of these graduates completing their degrees in Biochemistry and Molecular Biology (53.3%) or Computer Engineering (20%) (Table 2).

Most participants (54.2%) claimed that their Ph.D. was funded by public (44.9%) or private (9.3%) institutions. The public founders were the Complutense University of Madrid, the Ministry of Education and Vocational Training of Spain, and the Ministry of Economy and Digital Transformation of Spain. During their doctoral studies, 34.6% of all participants had a part-time job to self-fund their Ph.D. This employment was related to the bachelor’s studies in most of the cases (75.7% of the participants had a part-time job outside the university during their Ph.D.). However, this situation varies greatly among the areas of research (Ph.D. in Arts, Humanities, and Social or Legal Sciences; Ph.D. in Engineering, Architecture, or Sciences; or Ph.D. in Health Sciences). Most Ph.D. graduates from Engineering, Architecture, or Sciences (93.3%) were funded by public or private institutions, followed by just 56.2% from Health Sciences and 31.4% from Ph.D. in Arts, Humanities, and Social or Legal Sciences.

When the Ph.D. graduates from different areas were compared in terms of predoctoral research stays, statistically significant differences were found (X2 = 12.27, p-value = 0.002). It is worth highlighting that half of the participants (54.2%) performed a research stay for a few months in a different center while conducting their doctoral studies, particularly at the international level (35.5%), while only one-third (34.3%) of the responders in Arts, Humanities, and Social or Legal Sciences visit another laboratory during their Ph.D. studies (Table 2).

3.2. Training Received during Ph.D. Studies and Students’ Satisfaction Degree

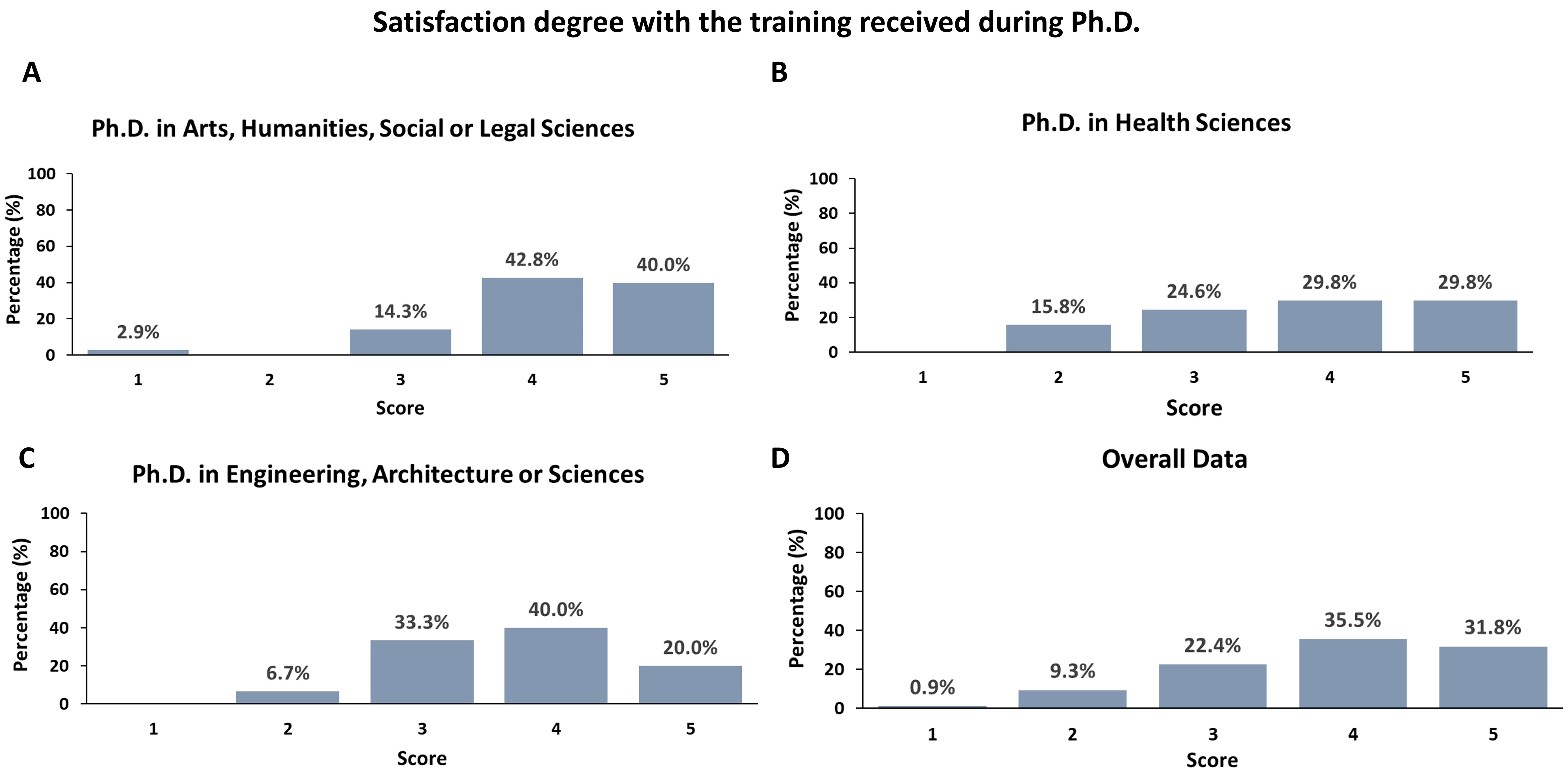

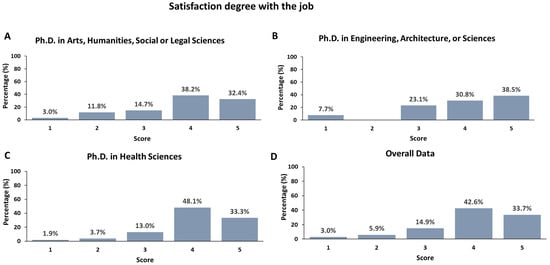

With an overall mean score of 3.8 (Table 3), two-thirds of the participants (67.4%) showed high satisfaction levels (values 4 or 5 on the Likert Scale) with the training received during their doctorate (Figure 1). The Ph.D. graduates in the areas of Engineering, Architecture, or Sciences and the areas of Arts, Humanities, and Social or Legal Sciences showed the lowest and highest mean scores, respectively, with values of 3.3 and 4.2 (Table 3).

Table 3.

Descriptive statistics of students’ satisfaction degree with different items related to the Ph.D. training and employment evaluated in this study. The data are analyzed globally and per area of knowledge.

Figure 1.

Satisfaction degree of the participants of the study with the training received during their doctoral studies in Arts, Humanities, and Social or Legal Sciences (A); Health Sciences (B); Engineering, Architecture, or Sciences (C); and overall participants (D). Satisfaction score: from 1 = very dissatisfied to 5 = very satisfied.

Regarding the employability training received during the doctorate, most of the participants (84.1%) showed a lack of information regarding this topic during their studies. On average, the student’s satisfaction with soft skill training required to prompt their career prospect was low (overall mean score of 2.58). Similar results were obtained when the data were analyzed in each area. It should be noted that half of the Ph.D. graduate respondents (55.1%) said they would like to obtain training relevant to professional opportunities following their Ph.D. in academia and outside academia when asked what type of training they felt they were missing from their doctorate studies. About 25% of people also missed classes on how to create a compelling CV and a cover letter.

Most respondents (82.2%) answered affirmatively to Q14, indicating that they would enroll again in the same Ph.D. studies after the experience. When the results were analyzed per area of knowledge, participants with a Ph.D. in Engineering, Architecture, or Sciences showed the highest satisfaction, while Ph.D. graduates in Arts, Humanities, and Social or Legal Sciences had the lowest percentage (both at 74.3%). However, these differences were not statistically significant (X2 = 2.93, p-value = 0.23).

Only 1.9% of the graduates perceived that the Ph.D. has not provided them with any benefits for their career development (Table 4). One-third only experienced a minimal improvement regarding employability after a Ph.D. However, two-thirds of the Ph.D. holders were satisfied with the doctoral studies as the Ph.D. journey has allowed them to enhance their employability and soft skills such as communication, organizational, problem-solving, and stress management skills as benefits of their doctoral education.

Table 4.

Benefits of doctoral studies perceived by the Ph.D. graduates within the study. Aggregated averaged data and distributed per areas of expertise are shown.

The two main reasons why Ph.D. graduates would not pursue doctoral studies again are the lack of funding during the Ph.D. and the lack of finding relevant, suitable, and high-paying employment afterward (Table 5).

Table 5.

Justifications for not enrolling in a Ph.D. Aggregated averaged data and distributed per areas of expertise are shown.

3.3. Career Prospects after Ph.D. Studies

High employability rates were found among Ph.D. graduates (94%). Graduates with a Ph.D. in Arts, Humanities, and Social or Legal Sciences had the highest employment rate (97.2%), followed by those with a Ph.D. in Health Sciences (94.3%) and those with a Ph.D. in Engineering, Architecture, or Sciences (86.7%). Table 6 displays job characteristics, including the time required to find a job, working hours, location, long-term or fixed contract, and salary band.

Table 6.

Characteristics of the employment of the Ph.D. graduates. The data were analyzed globally and per area of expertise.

Forty-four percent of the respondents already had a job before completing their Ph.D.s. Twenty-seven percent of those without a job at the Ph.D. defense date found a job in the following three months. Similar findings were discovered per area of expertise.

Most Ph.D. graduates found a job in which the doctoral degree was a requirement (61.3%), which is aligned with the fact that half of them fit academic and postdoctoral research jobs. Three-quarters of the Ph.D. graduates had full-time contracts in Spain, but only 35.5% had a long-term contract. Thirteen percent of the Ph.D. graduates worked as freelancers. The participants with a Ph.D. in Engineering, Architecture, or Sciences showed the lowest percentage of long-term contracts (20%). Nevertheless, statistically significant differences between areas of expertise were not found (X2 = 2.09, p = 0.35).

Regarding the salary band, on average, 16.8% of the Ph.D. graduates earn a gross annual salary of up to 14K EUR, 64.5% earn between 14 and 50K EUR, and 14% have a salary above 50K EUR. However, differences were found per area of expertise. All Ph.D. graduates in Engineering, Architecture, or Sciences earn a salary between 14 and 50K EUR. Larger segregation was observed in Arts, Humanities, and Social or Legal Sciences, where 20% earn a gross annual salary of up to 14K EUR, 60% between 21 and 50K EUR, and 20% above. A similar distribution was found for graduates in Health Sciences. The salaries are shown in detail in Table 6.

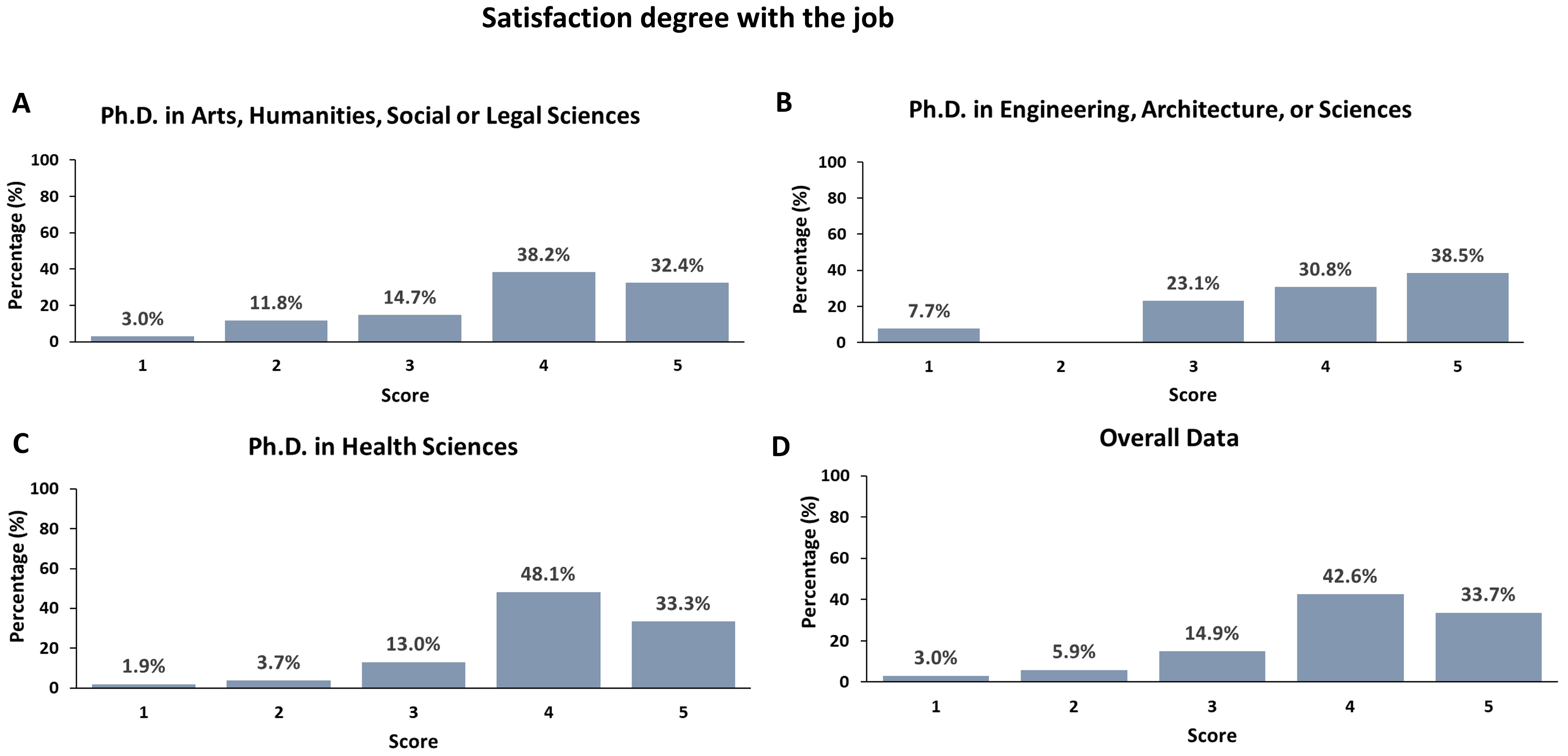

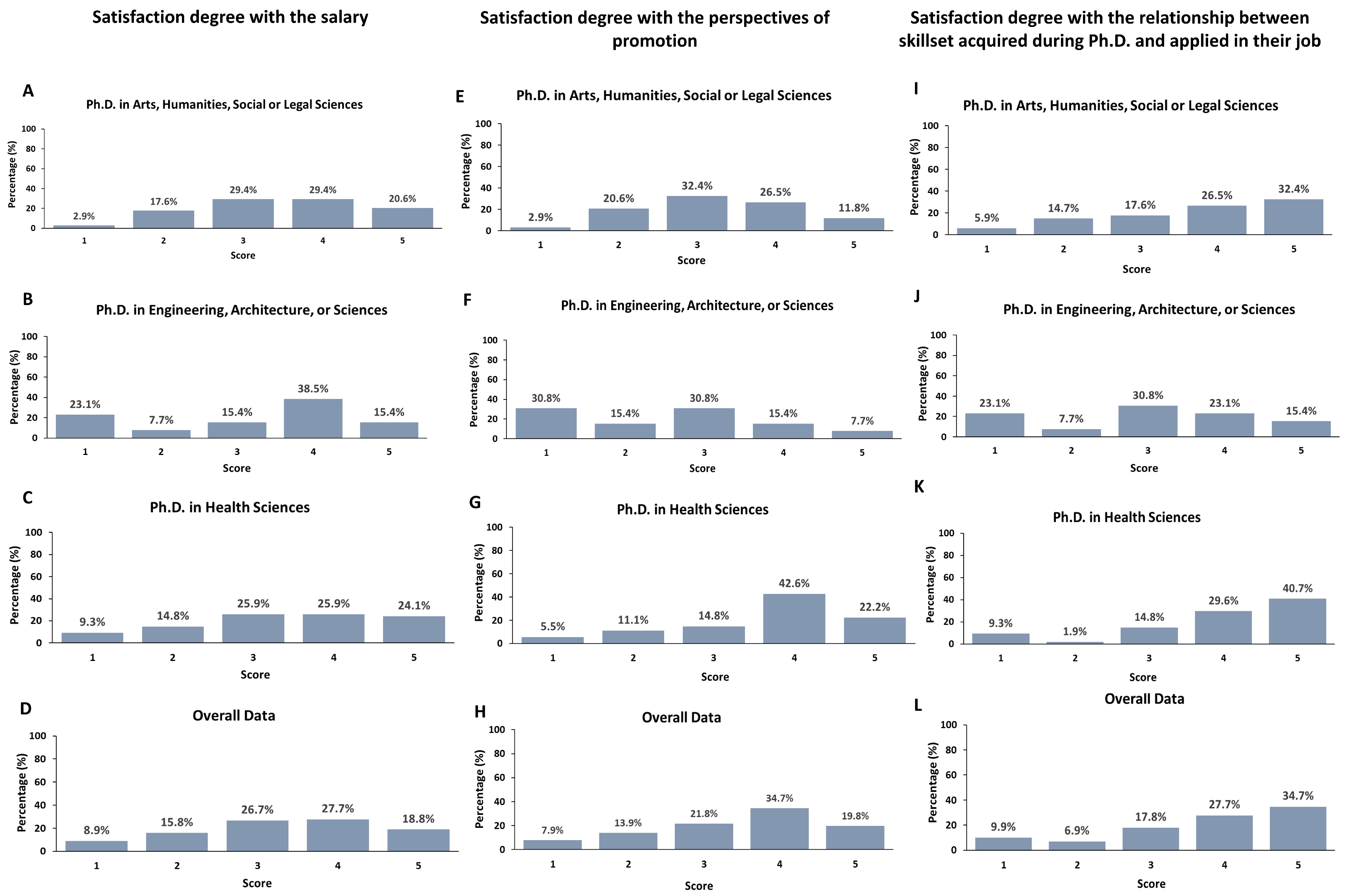

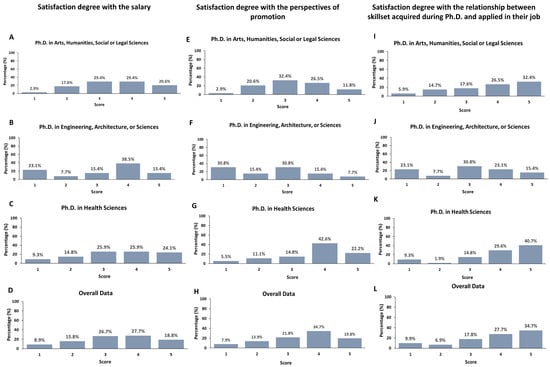

Finally, the participants reported a high level of overall satisfaction with the jobs secured after their Ph.D. (Figure 2 and Table 3). On average, Ph.D. holders showed a score value of 4. However, the level of satisfaction was lower with certain components of their job, such as salary, prospects for promotion, or the link between skillset acquired during Ph.D. and applied in the job (Figure 3), being the lowest satisfaction degree in the Ph.D. graduates in Engineering, Architecture, or Sciences, with a mean score of 3.0 for satisfaction degree with the link between skillset acquired during Ph.D. and applied in their job and 2.53 for satisfaction degree with their prospects of promotion.

Figure 2.

Satisfaction degree of the participants with the job obtained after doctoral studies in Arts, Humanities, and Social or Legal Sciences (A); Ph.D. graduates in Engineering, Architecture, or Sciences (B); Ph.D. graduates in Health Sciences (C); and overall participants (D). Satisfaction score: from 1 = very dissatisfied to 5 = very satisfied.

Figure 3.

Satisfaction degree of the participant Ph.D. graduates in Arts, Humanities, and Social or Legal Sciences; Ph.D. graduates in Engineering, Architecture, or Sciences; Ph.D. graduates in Health Sciences; and overall participants with the salary (A–D). Perspectives of promotion (E–H) in their jobs and the connection between qualifications obtained during Ph.D. and tasks required for their job (I–L). Satisfaction score: from 1 = very dissatisfied to 5 = very satisfied.

It should be noted that all the evaluated criteria for the participants’ job satisfaction degree, including employment, salary, promotion prospects, and the relationship between skillset acquired and applied at the job, showed a direct and statistically significant correlation (Spearman’s correlation coefficient (R) > 0.5, p-value < 0.001).

4. Discussion

This study aims to provide, for the first time, a detailed analysis of the labor insertion and opportunities of doctoral graduates from UCM, the largest university in Spain and one of the most prestigious according to QS World University Rankings, from 2015 to 2022.

This study includes graduates from Ph.D. programs in Arts, Humanities, and Social or Legal Sciences; Engineering, Architecture, or Sciences; and Health Sciences. While most Ph.D. holders in these two latter areas of knowledge received funding for their doctoral studies, mainly from public institutions, most Ph.D. holders in the Arts, Humanities, and Social or Legal Sciences were self-funded, having a job outside the university during their Ph.D. This explains why there were fewer students in this group who participated in predoctoral research stays. Additionally, participants in these disciplines enrolled in the Ph.D. later than those in the other areas, as evidenced by the greater median age of these participants. According to the discipline-specific paradigmatic development by Kuhn [27], several factors could influence the manner in which doctoral students are “trained”. Hence, disciplines in the area of Sciences, such as Biology and Chemistry, are considered high, whereas disciplines in the area of the Humanities, such as History or English, are considered low. Thus, the nature of training, e.g., laboratory work and the importance of research over teaching, can all influence whether a student receives funding support for Ph.D. studies, as well as for predoctoral research stays. However, in the case of Spain, this does not happen. The predoctoral research grants funded by public institutions are divided into areas of knowledge and awarded based on the scientific and academic merits of the applicants of a specific area, the curriculum vitae of their Ph.D. supervisor, and the scientific interest and quality of their Ph.D. projects. In this way, applicants from Sciences, Health Sciences, or Engineering do not compete with applicants from Arts, Humanities, or Social Sciences, so the nature of Ph.D. training does not influence receiving funding. For example, in the case of the predoctoral research grants awarded by the Complutense University of Madrid, each faculty has been assigned a certain number of grants based on the number of students enrolled in Ph.D. programs.

Intriguingly, most participants were satisfied or very satisfied with the training received while pursuing their doctorates, indicating that most of them would enroll in the same Ph.D. program again. The degree of satisfaction during Ph.D. studies is decisive for the mental health (depression, anxiety, and burnout) and well-being of the doctoral students [28]. Moreover, several factors influence the Ph.D. student’s satisfaction, such as the supervisor’s supportiveness and the academic qualities of the departments [29]. On the other hand, most graduates indicated that they did not receive any specific employability training (such as preparing a CV, writing a cover letter, looking for a job, or how to handle a job interview). Specific employability training/guidance improves graduates’ professional outcomes [30], and hence, there is no doubt that this training must be introduced in higher education institutions to find a high-quality job in which the acquired skills during a Ph.D. program can be applied. That is why recently, the Doctoral School of the Complutense University of Madrid has started to organize a series of optional transversal training activities specific for Ph.D. students, which include employability and entrepreneurship training, among others, for students to acquire the skills and abilities necessary for their professional development. Like the Complutense University of Madrid, other universities around the world have developed training programs focused on employment for their doctoral students [31,32].

High employability rates (>94%) were found among Ph.D. graduates from UCM across all areas of expertise. These data are higher than the 87% rate indicated in the “Panorama de la educación. Indicadores de la OCDE 2022” for Ph.D. graduates in Spain [18]. On the other hand, the value of the doctorate in employment varies across Europe and depends on factors such as industry involvement, economic development of the country, and demand for Ph.D. graduates outside of academia [33].

Doctoral studies have traditionally been associated with employment in academia [34,35]. In fact, in this study, most of the participants (around 52%) work in this area. However, Ph.D. graduates are also in high demand in areas other than academia, including in the private sector (industrial-related jobs) and government institutions. The number of Ph.D. graduates has significantly increased in the recent decade, and academia has become over-saturated [33,36]. This translates into a shift of Spanish Ph.D. graduates from academia to other posts [14]. It should be noted that the scope of this research is limited to UCM Ph.D. graduates from 2015 to 2022. This is indeed the largest university in Spain, with a high demand for professors, taking into account the average age of the faculty body. In fact, during this period, more than 160 new positions for postdoctoral researchers and professors were opened [37]. In terms of contract type, most Ph.D. holders (42%) have a fixed-term contract. This relates to the primary working environment, the academia. The majority of the Ph.D. graduates in this study work at universities as postdoctoral researchers or assistant professors. It is well recognized that an academic career is precarious [38], especially compared to the private sector, considering the salary band and the time required for a long-term contract.

Several studies have found that a high percentage of Ph.D. graduates have a job that requires a bachelor’s or master’s degree [15,33,39]. Our study is aligned with the latter observation, as 60% of the respondents needed the Ph.D. title to be hired, indicating that they were not overqualified for the position.

It should be noted that most participants were satisfied or very satisfied with their jobs obtained after their Ph.D. However, satisfaction levels decrease regarding salary, perspectives of promotion, and the relationship between the skillset acquired during their Ph.D. and the one applied in their current jobs. Previous studies have demonstrated that the type of contract, the working hours, and the salary of Ph.D. graduates are better outside academia. However, those jobs tend to have less relationship with the skills and knowledge acquired during Ph.D. studies [40].

Several studies have highlighted the “paradox of the contented female worker” from a gender perspective. Women typically have lower expectations than men, resulting in a higher satisfaction level. This evidence was found in a study among Spanish Ph.D. graduates, in which women were more satisfied with their jobs after their Ph.D. than men [23]. When the results from this survey were analyzed by gender, women had a slightly greater median satisfaction than males. However, statistically significant differences between men and women were not found using the Mann–Whitney U test (U = 1371, p-value = 0.75). There were no statistically significant differences in salary perceptions between men and women (X2 = 3.54, p-value = 0.61).

Limitations of the Study

Several limitations were found in this study. For instance, the survey was sent to the institutional mail. Many of the participants are Ph.D. graduates who no longer check university mail, limiting the response level to the survey. Even though it is difficult to contact Ph.D. graduates, this work has attained the required sample size and provides us with a comprehensive view of the current situation of Ph.D. graduates and the job market. Another limitation is that most respondents were from the area of Health Sciences. Finally, this work was carried out at the Complutense University of Madrid, which is the largest in Spain and one with the highest demand for academic positions. Additionally, UCM is located in a city with one of the lowest unemployment rates in Spain, so the results of our study cannot be extrapolated to other Spanish universities.

5. Conclusions

Employability rates and satisfaction level among Ph.D. holders from UCM is high. However, Ph.D. graduates demand additional training regarding employability and career perspective, which suggests the implementation of novel educational policies in higher institutions to bring together the academy and industry. Also, it is key to integrate a strategy to further develop soft skills, especially those in high demand within the public and private sectors, into the Ph.D. program.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/educsci13090909/s1; Table S1: Questionnaire sent to the participants of the study.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.I.F.-S. and E.G.-B.; methodology, A.I.F.-S., E.G.-B. and D.R.S.; formal analysis, A.I.F.-S. and M.Á.M.S.; investigation, A.I.F.-S., E.G.-B. and D.R.S.; data curation, A.I.F.-S. and M.Á.M.S.; writing—original draft preparation, A.I.F.-S. and E.G.-B.; writing—review and editing, A.I.F.-S., E.G.-B., M.Á.M.S. and D.R.S.; project administration, A.I.F.-S. and E.G.-B.; funding acquisition, A.I.F.-S. and E.G.-B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Observatorio del Estudiante-UCM, Project 33, and by the Spanish Institute of Women, Spanish Ministry of Equality (project 3/6ACT/22 and project 48-13-ID22).

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the UCM (Ref. CE_20220721-06_SOC).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Ministerio de Educación. Real Decreto 99/2011, de 28 de Enero, por el que se Regulan las Enseñanzas Oficiales de Doctorado; «BOE» núm. 35, de 10/02/2011; Ministerio de Educación de España: Madrid, Spain, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Tarvid, A. Motivation to Study for PhD Degree: Case of Latvia. Procedia Econ. Financ. 2014, 14, 585–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coutinho, I.R. A (de)formed perception of the pathway to be taken during the PhD. The influence of time in the students’ eyes perception in becoming a researcher. Adv. Soc. Sci. Res. J. 2020, 7, 272–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, T. What really contributes to employability of PhD graduates in uncertain labour markets? Glob. Soc. Educ. 2023, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eurostat. R&D Personnel; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Laudel, G.; Gläser, J. From apprentice to colleague: The metamorphosis of Early Career Researchers. High. Educ. 2008, 55, 387–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jolley, J. Choose your doctorate. J. Clin. Nurs. 2007, 16, 225–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tikkanen, L.; Pyhältö, K.; Bujacz, A.; Nieminen, J. Study Engagement and Burnout of the PhD Candidates in Medicine: A Person-Centered Approach. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 727746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernery, C.; Lusardi, L.; Marino, C.; Philippe-Lesaffre, M.; Angulo, E.; Bonnaud, E.; Guéry, L.; Manfrini, E.; Turbelin, A.; Albert, C.; et al. Highlighting the positive aspects of being a PhD student. eLife 2022, 11, e81075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bekova, S. Does employment during doctoral training reduce the PhD completion rate? Stud. High. Educ. 2021, 46, 1068–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, D.; Bridgstock, R. What actually works to enhance graduate employability? The relative value of curricular, co-curricular, and extra-curricular learning and paid work. High. Educ. 2021, 81, 723–739. [Google Scholar]

- Bryce, C.F.; Aghion, J.; Bos, P.; Celada, F.; Griffin, M.; Hull, R. European doctorate in biotechnology: Added value for european academia and industry. Biochem. Mol. Biol. Educ. 2004, 32, 352–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reithmeier, R.; O’leary, L.; Zhu, X.; Dales, C.; Abdulkarim, A.; Aquil, A.; Brouillard, L.; Chang, S.; Miller, S.; Shi, W.; et al. The 10,000 PhDs project at the University of Toronto: Using employment outcome data to inform graduate education. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0209898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mónica Benito Bonito, R.R.A. La Aportación de los Doctores al Desarrollo Económico y Social a Través de su Contribución a la I+D+i; Estudios CYD 05/2014; Fundación CYD: Barcelona, Spain, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Boman, J.B.; Sturtz, T.; De Young Becker, E.; Brecko, B.; Berzelak, N. 2017 Career Tracking Survey of Doctorate Holders; European Science Foundation (ESF): Strasbourg, France, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Törnroos, J. The Role of Doctoral Degree Holders in Society; Academy of Finland: Helsinki, Finland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Passaretta, G.; Trivellato, P.; Triventi, M. Between academia and labour market—the occupational outcomes of PhD graduates in a period of academic reforms and economic crisis. High. Educ. 2019, 77, 541–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministerio de Educación y Formación Profesional. Panorama de la Educación 2022. Indicadores de la OCDE. Informe Español; Ministerio de Educación y Formación Profesional: Madrid, Spain, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. Education at a Glance 2019; OECD: Paris, France, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Larson, R.C.; Ghaffarzadegan, N.; Xue, Y. Too Many PhD Graduates or Too Few Academic Job Openings: The Basic Reproductive Number R(0) in Academia. Syst. Res. Behav. Sci. 2014, 31, 745–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conti, A.; Visentin, F. Science and Engineering Ph.D. Students’ Career Outcomes, by Gender. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0133177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polka, J.K.; Krukenberg, K.A.; McDowell, G.S. A call for transparency in tracking student and postdoc career outcomes. Mol. Biol. Cell 2015, 26, 1413–1415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escardíbul, J.-O.; Afcha, S. Determinants of the job satisfaction of PhD holders: An analysis by gender, employment sector, and type of satisfaction in Spain. High. Educ. 2017, 74, 855–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Universidad de Murcia. La Inserción Laboral de los Titulados de la Universidad de Murcia; Universidad de Murcia: Murcia, Spain, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Universitat de Valencia. Estudio de la Actividad Laboral y Desarrollo de Carrera de los Doctores de la Universitat de Valencia; Universitat de Valencia: Valencia, Spain, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- AQU Catalunya. Encuesta 2020 a la Población Doctorada (Cursos Académicos 2014/2015 y 2015–2016); AQU Catalunya: Barcelona, Spain, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Kuhn, T.S. The Structure of Scientific Revolutions; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Naumann, S.; Matyjek, M.; Bögl, K.; Dziobek, I. Doctoral researchers’ mental health and PhD training satisfaction during the German COVID-19 lockdown: Results from an international research sample. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 22176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dericks, G.; Thompson, E.; Roberts, M.; Phua, F. Determinants of PhD student satisfaction: The roles of supervisor, department, and peer qualities. Assess. Eval. High. Educ. 2019, 44, 1053–1068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okolie, U.C.; Nwajiuba, C.A.; Binuomote, M.O.; Ehiobuche, C.; Igu, N.C.N.; Ajoke, O.S. Career training with mentoring programs in higher education. Educ. + Train. 2020, 62, 214–234. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, E.M.; Parmenter, L. Transferable skills for global employability in PhD curriculum transformation. In Proceedings of the Curriculum Transformation HERDSA Higher Education Research and Development Society of Australasia, Sydney, Australia, 27–30 June 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Stamati, K.; Willmott, L. Preparing UK PhD students towards employability: A social science internship programme to enhance workplace skills. J. Furth. High. Educ. 2023, 47, 151–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hnatkova, E.; Degtyarova, I.; Kersschot, M.; Boman, J. Labour market perspectives for PhD graduates in Europe. Eur. J. Educ. 2022, 57, 395–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derycke, H.; Kaat, A.T.; Rossem, R.V.; Groenvynck, H. Ph.D. graduates in the humanities and social sciences: What do they do? Int’l J. Educ. L. Pol’y 2014, 10, 69. [Google Scholar]

- Young, S.; Kelder, J.-A.; Crawford, J. Doctoral employability: A systematic literature review and research agenda. J. Appl. Learn. Teach. 2020, 3, 97–107. [Google Scholar]

- Bao, Y.; Kehm, B.; Ma, Y. From product to process. The reform of doctoral education in Europe and China. Stud. High. Educ. 2016, 43, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estadísticas Universitarias Personal Docente e Investigador e Investigadores. Área de Análisis Departamento de Estudios e Imagen Corporativa; Universidad Complutense de Madrid: Madrid, Spain, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Le, A.T. To be or not to be (in academia)? ‘Inward calling’ and ‘academic hazards’ in aspiring academics’ career prospects in Australia. High. Educ. Res. Dev. 2023, 42, 874–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bebiroglu, N.; Dethier, B.; Ameryckx, C. Education-Job Match among PhD Holders in the Federation Wallonia-Brussels; Observatory of Research and Scientific Careers: Brussels, Belgium, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Sala-Bubaré, A.; Garcia-Morante, M.; Castelló, M.; Weise, C. PhD holders’ working conditions and job satisfaction in Spain: A cross-sector comparison. Res. Sq. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions, and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions, or products referred to in the content. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).