Learning Attainment in English Lessons: A Study of Teachers’ Perspectives on Native English Speakers and English as an Additional Language (EAL) Students at an International School

Abstract

:1. Introduction

Which teaching approaches do English teachers adopt for native English and EAL students?

What kind of evidence do they have regarding the learning attainment of both groups?

What support do they need to enhance the attainment of both groups of students?

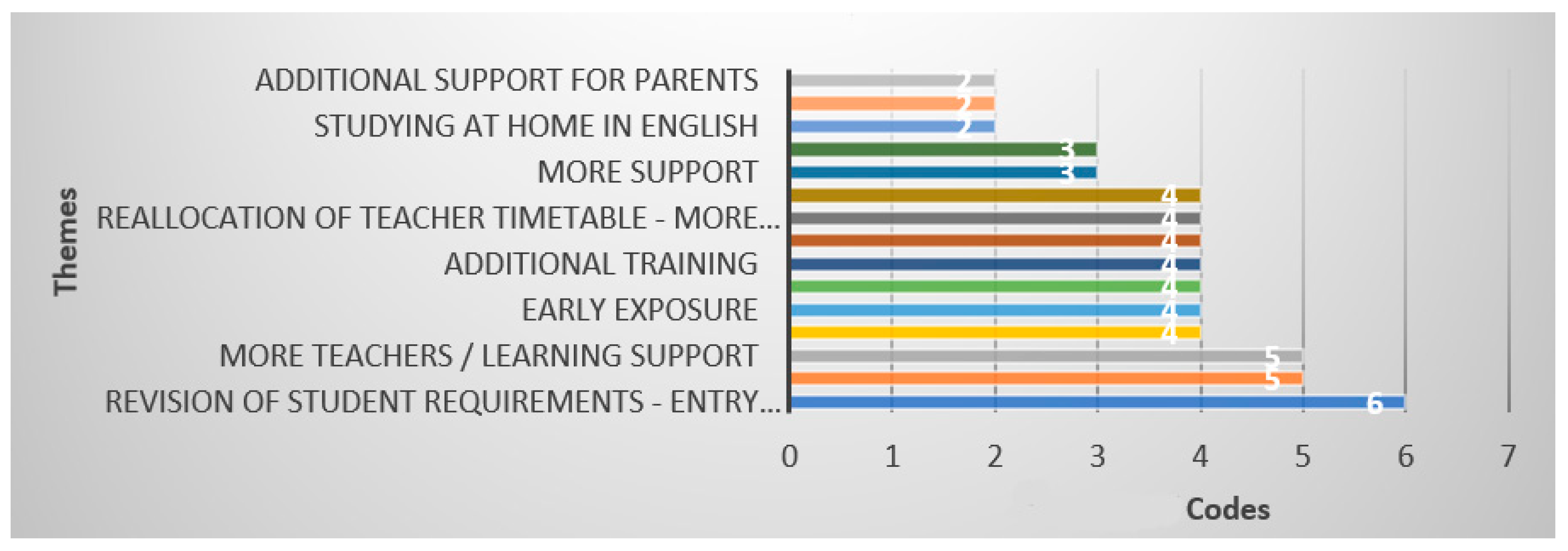

What proposals do they have to ensure equal opportunities for both groups when studying the English language?

2. Review of the Literature

2.1. Literature Search Strategy

2.2. English as a Foreign Language and EAL Learners

2.3. Educational Attainment and the Relationship between Language and Educational Needs

2.4. Teaching at International Schools

2.5. Synthesis

3. Methods

Ethical Considerations

4. Results

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions, Limitations, and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

- Overview

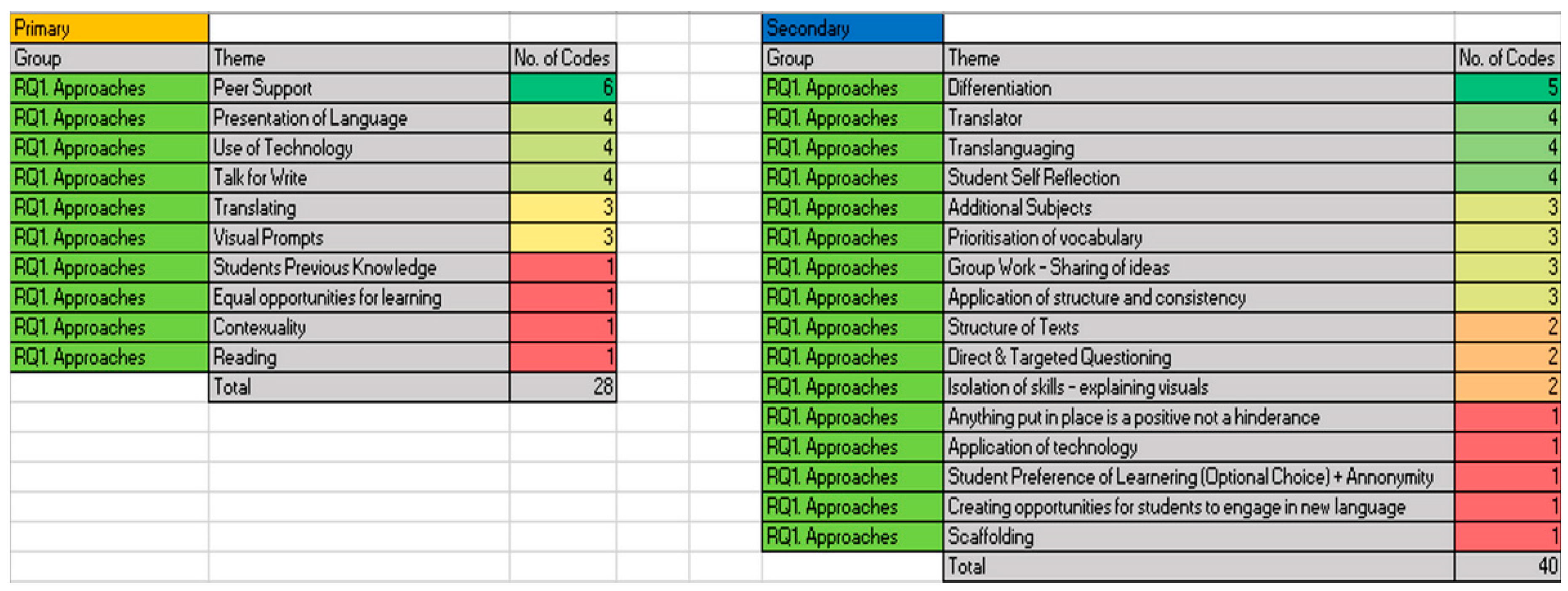

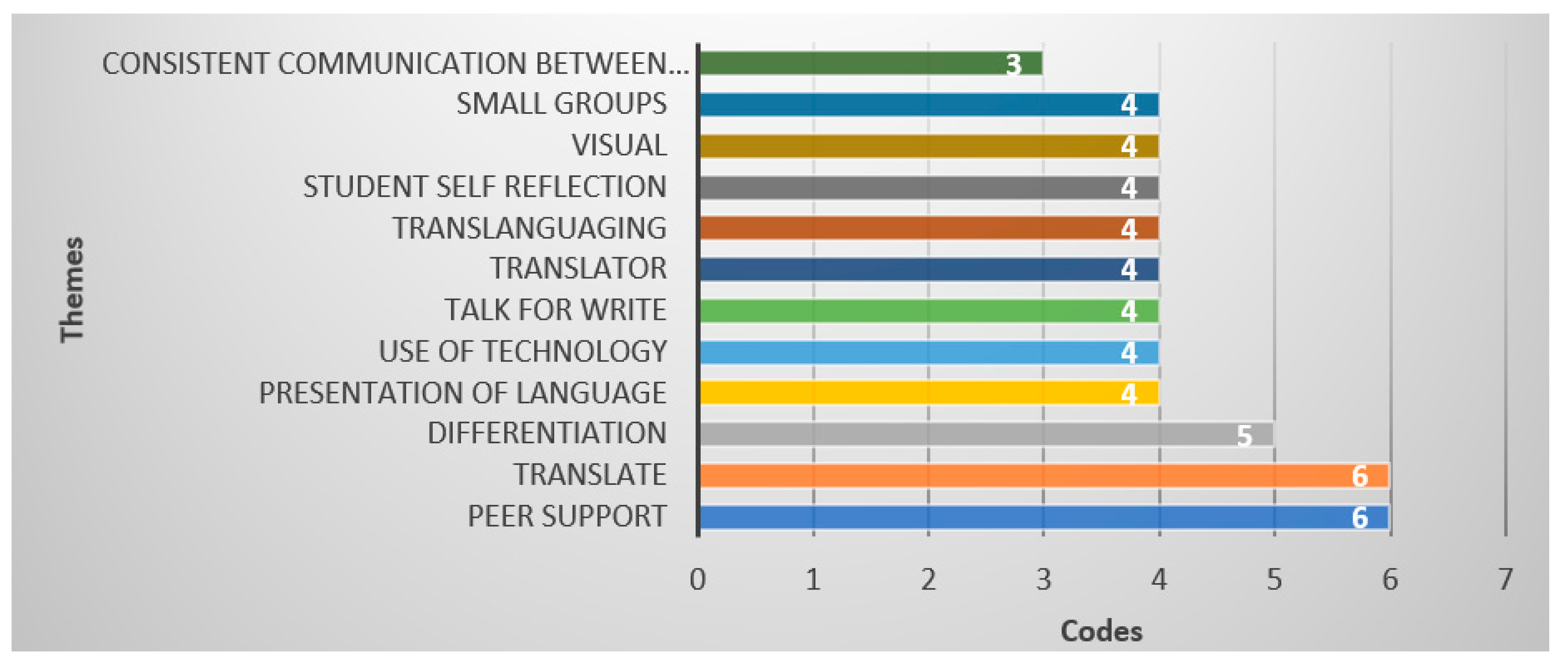

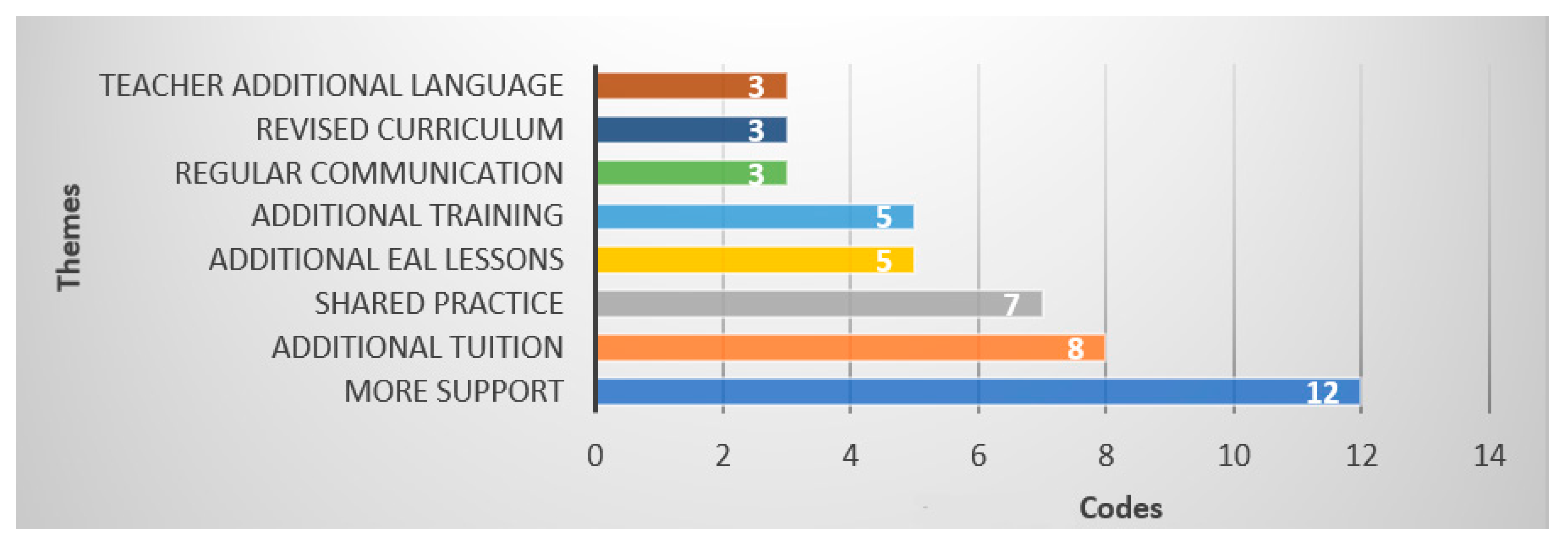

- Which teaching approaches do the included teachers provide for native English and EAL students?

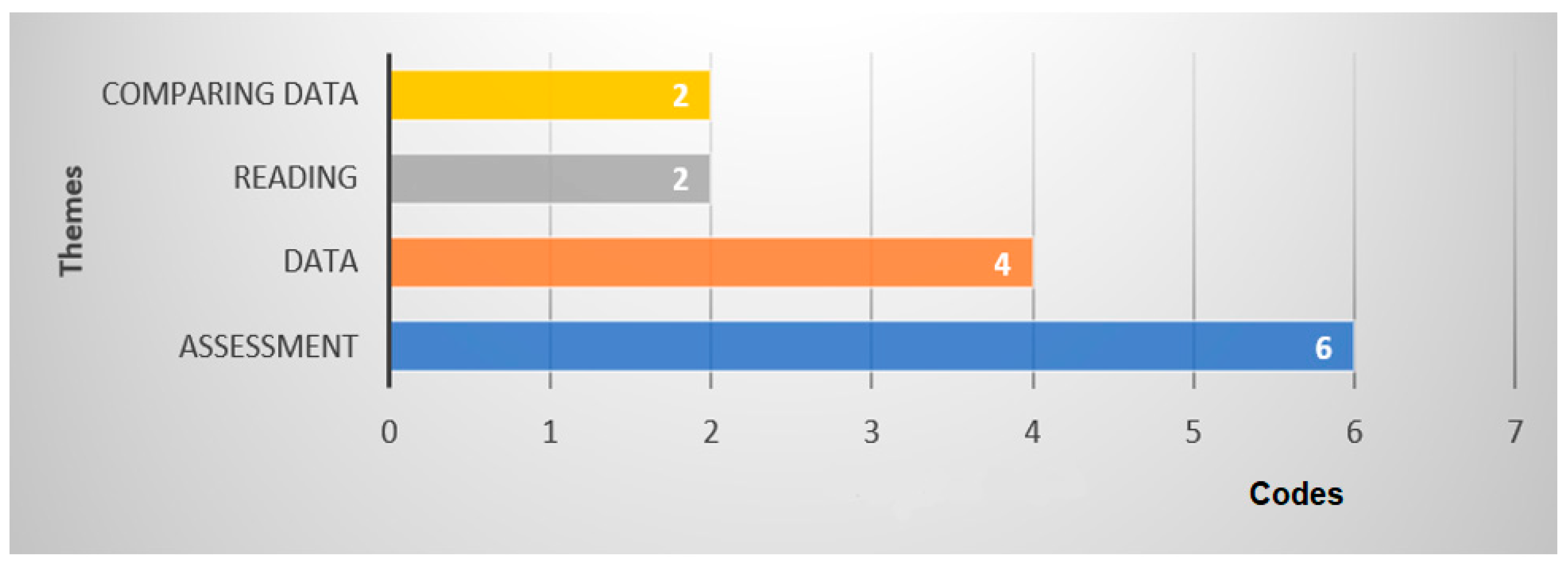

- What evidence do the included teachers have regarding the learning attainment of both groups of learners?

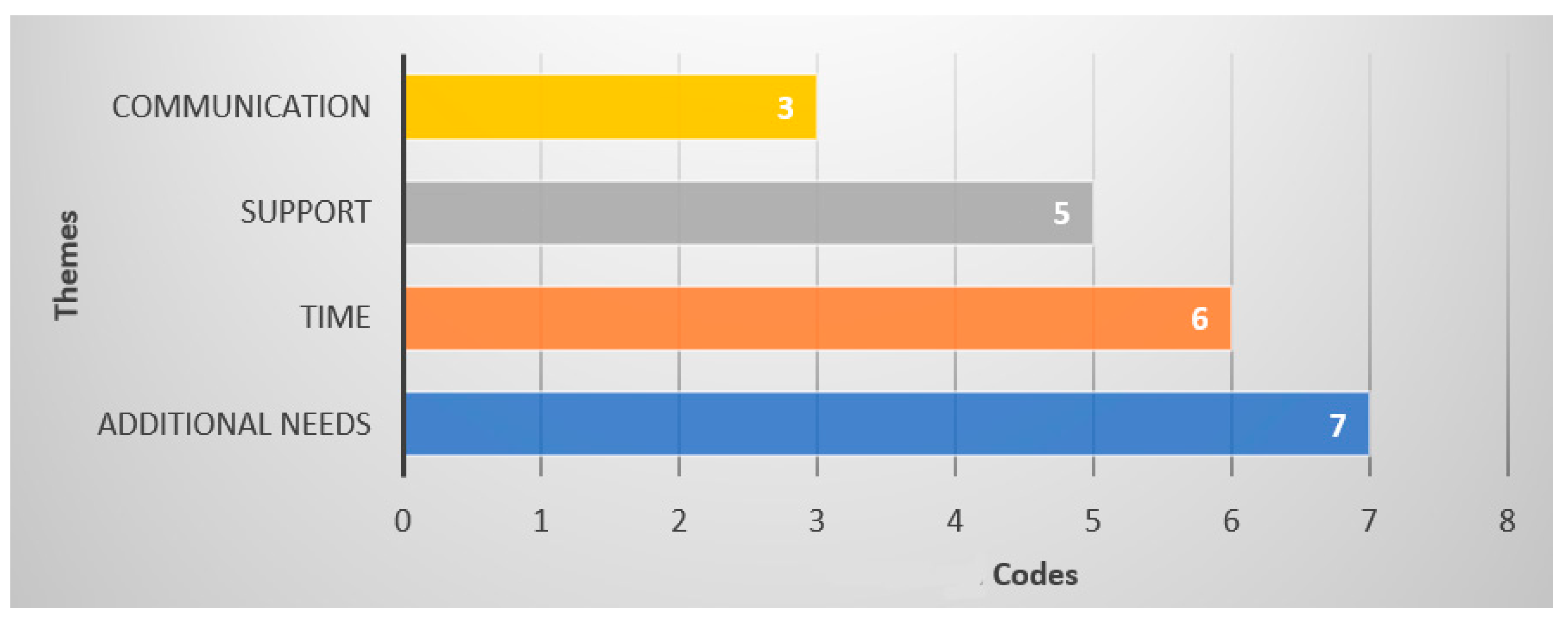

- What do the included teachers need to be able to improve the attainment of both groups of students?

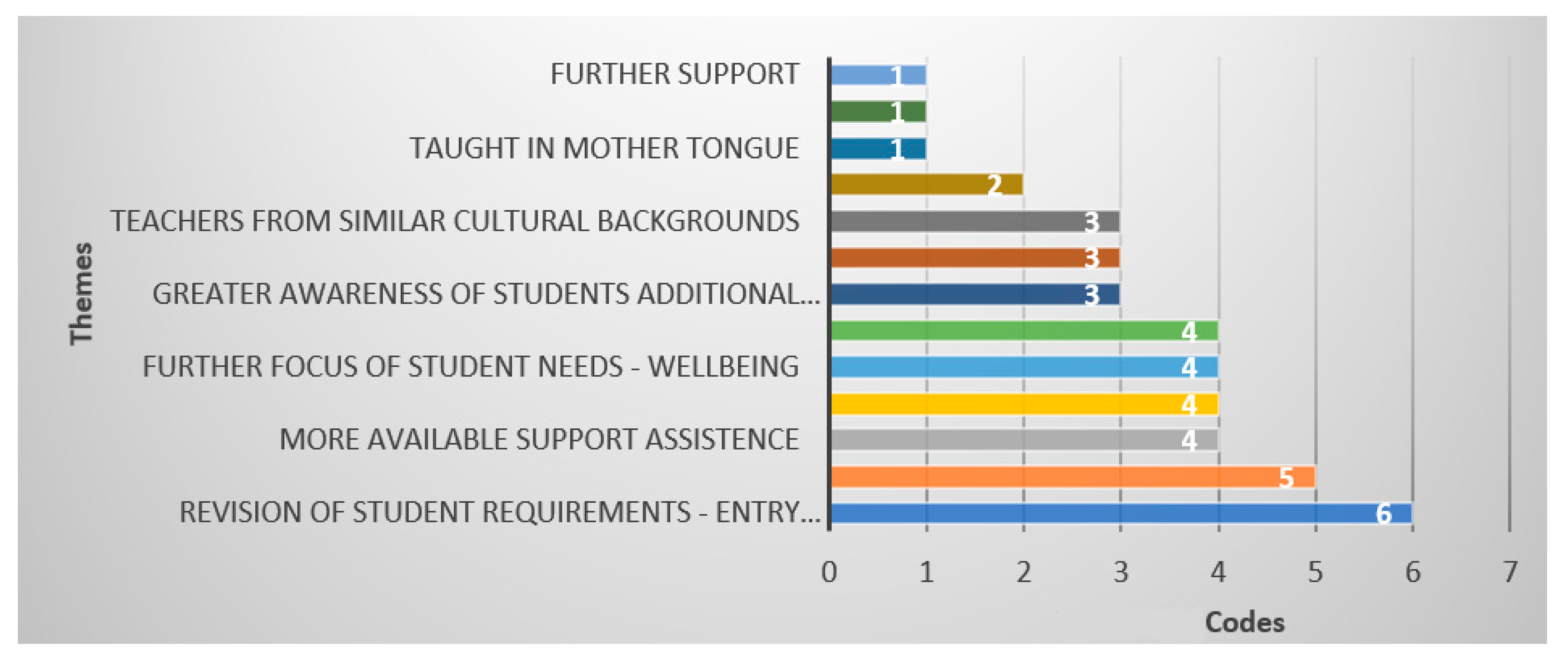

- What proposals do the included teachers have to ensure that both groups of students have equal opportunities when studying the English language?

- My role as interviewer will be to guide the discussion and provide further clarification on questions when required.

- Please do not interrupt participants or comment until they have finished their statement.

- Please take your time to respond to the discussion.

- You may take a break if required.

- There are no right or wrong answers.

- Please ensure mobile phones are switched off during the discussion.

- Introduction

How would the participants describe their teaching experiences, with regard to the positives and negatives of teaching both native English and EAL students within lessons taught in the English language?

- Which teaching approaches do the included teachers provide for native English and EAL students and how effective are these approaches?

Prompting questions for interviewer:—What is your experience like of teaching both native English and EAL learners together within lessons taught in the English language?

- 2.

- Which teaching approaches do you provide for both native English and EAL students in the classroom to ensure learning attainment is achieved as equally as possible?

Prompting questions for interviewer:—What approaches have you used for both sets of learners within the classroom? How have these approaches been effective or ineffective?

- 3.

- Have you had any feedback from the students in your classroom with regard to how they feel about working alongside both sets of learners?

Prompting questions for interviewer:—Was the feedback positive? Was the feedback negative? Do you think this arrangement could be improved at all?

- 4.

- What approaches or systems are used to record student learning attainment?

Prompting questions for interviewer:—Do you use multiple methods to record learning attainment? Are the approaches to recording learning attainment of both sets of learners different or the same?

- 5.

- What methods or approaches do you think need to be improved or developed inside and outside of the classroom in order to improve the attainment of both sets of learners?

Prompting questions for interviewer:—Do you think the current approaches used are effective regarding both sets of learners’ learning attainment?

- 6.

- Do you believe that the learning attainment differences between the two sets of learners are hindered when working together within English-led taught lessons?

Prompting questions for interviewer:—Do you think there is a big difference between the ability to satisfy each set of learners’ learning attainment requirements when they are taught together? Do you think one set of learners requires more attention than the other?

- 7.

- How could future approaches be developed to ensure that both sets of learners have equal opportunities when studying the English language?

Prompting questions for interviewer:—Do you think the current approaches allow for equal opportunities? Do you think there are any areas in which there are big gaps regarding the opportunities available to each set of learners? How and why do you think this is?

- 8.

- Are there any further areas of consideration which you believe we have not covered in this discussion and are worth mentioning with regard to both native English and EAL students’ learning attainment in English lessons?

Prompting questions for interviewer:—Is there anything you believe is worth mentioning that has not yet been covered?

- Schedule and Additional Information

Appendix B

- Participant Information Sheet

- Title of the Study

- Overview

- Which teaching approaches do the included teachers provide for native English and EAL students?

- What evidence do the included teachers have regarding the learning attainment of both groups of learners?

- What do the included teachers need to be able to improve the attainment of both groups of students?

- What proposals do the included teachers have to ensure that both groups of students have equal opportunities when studying the English language?

- Research Activity

- Key Information for Participants

- Contact Information

References

- Finkelstein, S.; Sharma, U.; Furlonger, B. The inclusive practices of classroom teachers: A scoping review and thematic analysis. Int. J. Incl. Educ. 2021, 25, 735–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flockton, G.; Cunningham, C. Teacher educators’ perspectives on preparing student teachers to work with pupils who speak languages beyond English. J. Educ. Teach. 2021, 47, 220–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, L.; Sowden, H. Reflective accounts of teaching literacy to pupils with English as an additional language (EAL) in primary education. Res. J. Natl. Assoc. Teach. Engl. 2019, 55, 286–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagger, M.S. Grit and self-discipline as predictors of effort and academic attainment. Br. J. Educ. Psychol. 2018, 89, 324–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogulksi, C.; Bice, K.; Kroll, J. Bilingualism as a Desirable Difficult: Advantages In Word Learning Depend On Regulation Of The Dominant Language. Biling. Lang. Cogn. 2018, 22, 1052–1067. [Google Scholar]

- Chuang, H.H.; Weng, C.Y.; Chen, C.H. Which Students Benefit Most from A Flipped Classroom Approach to Language Learning. Br. J. Educ. Technol. 2018, 49, 56–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dos Santos, L.M. Discussion of Communicative Language Teaching Approach in Language Classrooms. J. Educ. E-Learn. Res. 2020, 7, 104–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fadlallah, R.; El-Harakeh, A.; Bou-Karroum, L.; Lotfi, T.; El-Jardali, F.; Hishi, L.; Akl, E.A. A Common Framework of Steps and Criteria For Prioritizing Topics For Evidence Syntheses: A Systematic Review. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2020, 120, 67–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coe, R.; Waring, M.; Hedges, L.V.; Ashley, L.D. Research Methods and Methodologies in Education; SAGE: London, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Wijayanti, E.; Mujiyanto, Y.; Pratama, H. The Influence of The Teachers’ Reading Habbit On Their Teaching Practice: A Narrative Inquiry. Engl. Educ. J. 2022, 12, 205–214. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, D.; Fallin, L. Literature Review. In Getting Started in Your Educational Research: Design, Data Production and Analysis; Opie, C., Brown, D., Eds.; SAGE: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Salvador-Oliván, J.A.; Marco-Cuenca, G.; Arquero-Avilés, R. Errors in Search Strategies Used In Systematic Reviews And Their Effects On Information Retrieval. J. Med. Libr. Assoc. 2019, 107, 210–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixon, C.; Hessel, A.; Smith, N.; Nielsen, D.; Wesierska, M.; Oxley, E. Receptive and expressive vocabulary development in children learning English as an additional language: Converging evidence from multiple datasets. J. Child Lang. 2022, 50, 610–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kane, F.; Kennedy, L.; Sevdali; Folli, R.; Rhys, C. Language made fun: Supporting EAL students in primary education. Teanga 2019, 10, 113–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chalmers, H. Leveraging the L1: The Role of EAL Learners’ First Language in Their Acquisition of English Vocabulary. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Oxford, Oxford, UK, 2019; 296p. [Google Scholar]

- Creagh, S.; Kettle, M.; Alford, J.; Comber, B.; Shield, P. How long does it take to achieve academically in a second language?: Comparing the trajectories of EAL students and first language peers in Queensland schools. Aust. J. Lang. Lit. 2019, 42, 145–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, C.; Arnot, M. An exploration of school communication approaches for newly arrived EAL students: Applying three dimensions of organisational communication theory. Camb. J. Educ. 2018, 48, 245–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forbes, K. The role of individual differences in the development and transfer of writing strategies between foreign and first language classrooms. Res. Pap. Educ. 2019, 34, 445–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babayigit, S.; Shapiro, L. Component skills that underpin listening comprehension and reading comprehension in learners with English as first and additional languages. J. Res. Read. 2019, 43, 78–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosar, G.; Bedir, H. Improving Knowledge Retention Via Establishing Brain-Based Learning Environment. Eur. J. Educ. Stud. 2018, 4, 208–218. [Google Scholar]

- Chumak-Horbatsch, R. Using Linguistically Appropriate Practice: A Guide for Teaching in Multilingual Classrooms; Multilingual Matters: Bristol, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Conteh, J. The EAL Teaching Book: Promoting Success for Multilingual Learners; Learning Matters: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Costley, T.; Gkonou, C.; Myles, F.; Roehr-Brackin, K.; Tellier, A. Multilingual and monolingual children in the primary-level language classroom: Individual differences and perceptions of foreign language learning. Lang. Learn. J. 2020, 48, 643–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinclair, J.C.; Law, C. Initial assessment for K-12 English language support in six countries: Revisiting the validity-reliability paradox. Lang. Educ. 2018, 32, 257–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamed, M.; Fadhil, T. Teaching English in Elqubba Primary Schools: Issues and Directions. J. Educ. Learn. 2019, 13, 410–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demie, F. English language proficiency and attainment of EAL (English as second language) pupils in England. J. Multiling. Multicult. Dev. 2018, 39, 641–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zelinsky, T.; Hudec, O.; Mojsejova, A.; Hricova, S. The effects of population density on subjective well-being: A case-study of Slovakia. Socio-Econ. Plan. Sci. 2021, 78, 101061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahorec, J.; Haskova, A.; Munk, M. Self-Reflection of Digital Literacy of Primary and Secondary School Teachers: Case Study of Slovakia. Eur. J. Contemp. Educ. 2021, 10, 496–508. [Google Scholar]

- Butterworth, A. Issues in Roma Education: The Relationship Between Language and the Educational Needs of Roma Students. Res. Teach. Educ. 2019, 9, 34–38. [Google Scholar]

- Noman, M.; Gurr, D. Contextual Leadership and Culture in Education. In Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Education; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Toropova, A.; Myrberg, E.; Johansson, S. Teacher job satisfaction: The importance of school working conditions and teacher characteristics. Educ. Rev. 2019, 73, 71–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanifa, R. Factors generating anxiety when learning EFL speaking skills. Stud. Engl. Lang. Educ. 2018, 5, 230–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sallang, H.; Ling, Y.L. The Importance of Immediate Constructive Feedback on Students’ Instrumental Motivation in Speaking in English. Br. Int. Linguist. Arts Educ. Sci. J. 2019, 1, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piller, I.; Gerber, L. Family language policy between the bilingual advantage and the monolingual mindset. Int. J. Biling. Educ. Biling. 2018, 24, 622–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooks, J.S.; Heffernan, A. The School Leadership Survival Guide: What to Do When Things Go Wrong, How to Learn from Mistakes, and Why You Should Prepare for the Worst; IAP: Charlotte, NC, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Epstein, J.L. School, family, and community partnerships in teachers’ professional work. J. Educ. Teach. 2018, 44, 397–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papi, M.; Hiver, P. Language Learning Motivation as a Complex Dynamic System: A Global Perspective of Truth, Control, and Value. Mod. Lang. J. 2020, 104, 209–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alzeebaree, Y.; Hasan, A.I. What Makes an Effective EFL Teacher: High School Students’ Perceptions. Asian ESP J. 2021, 16, 169–183. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Shammari, Z.; Faulkner, P.E.; Forlin, C. Theories-based Inclusive Education Practices. Educ. Q. Rev. 2019, 2, 408–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naibaho, L. Teachers’ Roles On English Language Teaching: A Students Centred Learning Approach. Int. J. Res. 2019, 7, 206–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howitt, L. Language, Identity and the School Curriculum: Challenges and Opportunities for Students with English as an Additional Language (EAL) in ‘Lowincidence’ Secondary School Contexts. Doctoral Thesis, Northumbria University, Newcastle upon Tyne, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Ainscow, M. Promoting inclusion and equity in education: Lessons from international experiences. Nord. J. Stud. Educ. Policy 2020, 6, 7–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abramova, G.S.; Mashoshina, V.S. On Differentiation Strategies in the EFL Mixed-Ability Classroom: Towards Promoting the Synergistic Learning Environment. Eur. J. Contemp. Educ. 2021, 10, 558–573. [Google Scholar]

- Hanushek, E.A. Chapter 13—Education production functions. In The Economics of Education, 2nd ed.; Bradley, S., Green, C., Eds.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2020; pp. 161–170. [Google Scholar]

- Shah, R.K. Effective Constructivist Teaching Learning in the Classroom. Shanlax Int. J. Educ. 2019, 7, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, H.; Li, X. Research on Innovation Method of College English Translation Teaching Under the Concept of Constructivism. Educ. Sci. Theory Pract. 2018, 18, 2455–2461. [Google Scholar]

- Akinyode, B.F.; Khan, T.H. Step by step approach for qualitative data analysis. Int. J. Built Environ. Sustain. 2018, 5, 163–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sölpük Turhan, N. Qualitative Research Designs: Which One is the Best for Your Research? Eur. J. Spec. Educ. Res. 2019, 4. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, M.; Louis, K.S. Mapping a strong school culture and linking it to sustainable school improvement. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2019, 81, 84–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McEwan, B. Sampling and Validity. Ann. Int. Commun. Assoc. 2020, 44, 235–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mweshi, G.K.; Sakyi, K. Application of Sampling Methods for The Research Design. Arch. Bus. Res. 2020, 8, 180–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O.Nyumba, T.; Wilson, K.; Derrick, C.J.; Mukherjee, N. The use of focus group discussion methodology: Insights from two decades of application in conservation. Methods Ecol. Evol. 2018, 9, 20–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bajec, B. Relationship between time perspective and time management behaviours. Psihologija 2019, 52, 197–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flick, U. The SAGE Handbook of Qualitative Data Collection; SAGE: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Young, J.C.; Rose, D.C.; Mumby, H.S.; Benitez-Capistros, F.; Derrick, C.J.; Finch, T.; Garcia, C.; Home, C.; Marwaha, E.; Morgans, C.; et al. A methodological guide to using and reporting on interviews in conservation science research. Methods Ecol. Evol. 2018, 9, 10–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchanan, D.; Warwick, I. First do no harm: Using ‘ethical triage’ to minimise causing harm when undertaking educational research among vulnerable participants. J. Furth. High. Educ. 2021, 45, 1090–1103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pardo Soto, C.V.; Cisterna Zenteno, C. Smartphone Screen Recording Apps: An Effective Tool to Enhance Fluency in the English Language. Colomb. Appl. Linguist. J. 2019, 21, 208–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henderson, H. Difficult questions of difficult questions: The role of the researcher and transcription styles. Int. J. Qual. Stud. Educ. 2018, 31, 143–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vindrola-Padros, C.; Johnson, G.A. Rapid Techniques in Qualitative Research: A Critical Review of the Literature. Qual. Health Res. 2020, 30, 1596–1604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greckhamer, T.; Furnari, S.; Fiss, P.C.; Aguilera, R.V. Studying configurations with qualitative comparative analysis: Best practices in strategy and organization research. Strateg. Organ. 2018, 16, 482–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, M.; Moser, T. The Art of Coding and Thematic Exploration in Qualitative Research. Int. Manag. Rev. 2019, 15, 45–55. [Google Scholar]

- Deterding, N.M.; Waters, M.C. Flexible Coding of In-depth Interviews: A Twenty-first-century Approach. Sociol. Methods Res. 2018, 50, 708–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peel, K.L. A Beginner A Beginner’s Guide to Applied Educational Research using Thematic Analysis. Pract. Assess. Res. Eval. 2020, 25, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, R.M.; Chan, C.D.; Farmer, L.B. Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis: A Contemporary Qualitative Approach. Couns. Educ. Superv. 2018, 57, 240–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BERA. Ethics and Guidance. 2018. Available online: https://www.bera.ac.uk/resources/all-publications/resources-for-researchers (accessed on 10 July 2023).

- Sim, J.; Waterfield, J. Focus group methodology: Some ethical challenges. Qual. Quant. 2019, 53, 3003–3022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhajirah, M. Basic of Learning Theory. Int. J. Asian Educ. 2020, 1, 37–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tolstova, O.; Levasheva, Y. Humanistic trend in education in a global context. SHS Web Conf. 2019, 69, 00121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixon, C.; Thomson, J.; Fricke, S. Language and reading development in children learning English as an additional language in primary school in England. J. Res. Read. 2020, 43, 309–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magableh, I.S.I.; Abdullah, A. The Impact of Differentiated Instruction on Students’ Reading Comprehension Attainment in Mixed-Ability Classrooms. Interchange 2021, 52, 255–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGuinness, N.; Vlachopoulos, D. Student Experiences of Using Online Material to Support Success in A-Level Economics. Int. J. Emerg. Technol. Learn. 2021, 14, 80–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Perry, L.R.; Vlachopoulos, D. Learning Attainment in English Lessons: A Study of Teachers’ Perspectives on Native English Speakers and English as an Additional Language (EAL) Students at an International School. Educ. Sci. 2023, 13, 901. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci13090901

Perry LR, Vlachopoulos D. Learning Attainment in English Lessons: A Study of Teachers’ Perspectives on Native English Speakers and English as an Additional Language (EAL) Students at an International School. Education Sciences. 2023; 13(9):901. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci13090901

Chicago/Turabian StylePerry, Lewis Ron, and Dimitrios Vlachopoulos. 2023. "Learning Attainment in English Lessons: A Study of Teachers’ Perspectives on Native English Speakers and English as an Additional Language (EAL) Students at an International School" Education Sciences 13, no. 9: 901. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci13090901

APA StylePerry, L. R., & Vlachopoulos, D. (2023). Learning Attainment in English Lessons: A Study of Teachers’ Perspectives on Native English Speakers and English as an Additional Language (EAL) Students at an International School. Education Sciences, 13(9), 901. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci13090901