1. Introduction

Until now, teaching has remained a highly individualised activity, with only little collaboration with other teachers [

1]. Teachers seem to work primarily in their own classroom, largely isolated from other colleagues [

2]. This isolation of teachers may impair learning opportunities for teachers as well as for students [

3]. In this respect, evidence suggests that teacher collaboration results in positive outcomes for both teachers and students [

4]. Teachers who collaborate can feel less isolated [

5] and be more effective in their teaching [

6,

7]. Further, students whose teachers collaborate may experience higher learning outcomes, richer and more varied lessons, and increased support [

8]. Hence, collaboration has been put forward by scholars as a way to improve teachers’ teaching practice (e.g., [

6,

9,

10]).

Collaboration within schools has, therefore, gained importance [

11]. In this respect, educational institutions show a growing interest in teaching models in which teachers are more committed to collaborating, sharing expertise and experiences, supporting each other, and learning collaboratively [

12], such as team teaching [

13]. Team teaching can be described as two or more teachers in some level of collaboration in the planning, delivery, and/or evaluation of a course or courses [

14]. Given its promising character [

15], attention for team teaching has increased significantly during the past two decades [

16]. This applies to both fundamental research and educational practice [

17]. Despite an increased interest in and emphasis on teacher collaboration [

18], team teaching has only been studied to a limited extent [

19].

The practice of team teaching—how teachers deliver team teaching in the classroom—substantially determines its effect [

20]. Because the practice of team teaching plays a crucial role in the impact of team teaching, Sweigart and Landrum [

21] recommend that further analysis of the practice of team teaching is necessary. However, to date, there exists no appropriate measurement instrument that captures important dimensions of the practice of team teaching. Therefore, this study attempts to contribute to the research base on team teaching by developing an instrument to assess important dimensions of the practice of team teaching (i.e., collaboration and shared responsibility). By pioneering the development of such an instrument, this study aims to fill an existing gap. Additionally, this study aims to investigate whether differences exist between groups of teachers regarding these important dimensions. It thus goes beyond instrument development and also advances research on collaborative learning environments. In this way, it not only fills a gap in research but also reveals valuable insights that can foster more effective team teaching practices.

5. Results

5.1. Development of an Instrument to Capture Collaboration and Shared Responsibility in Team Teaching (RG1)

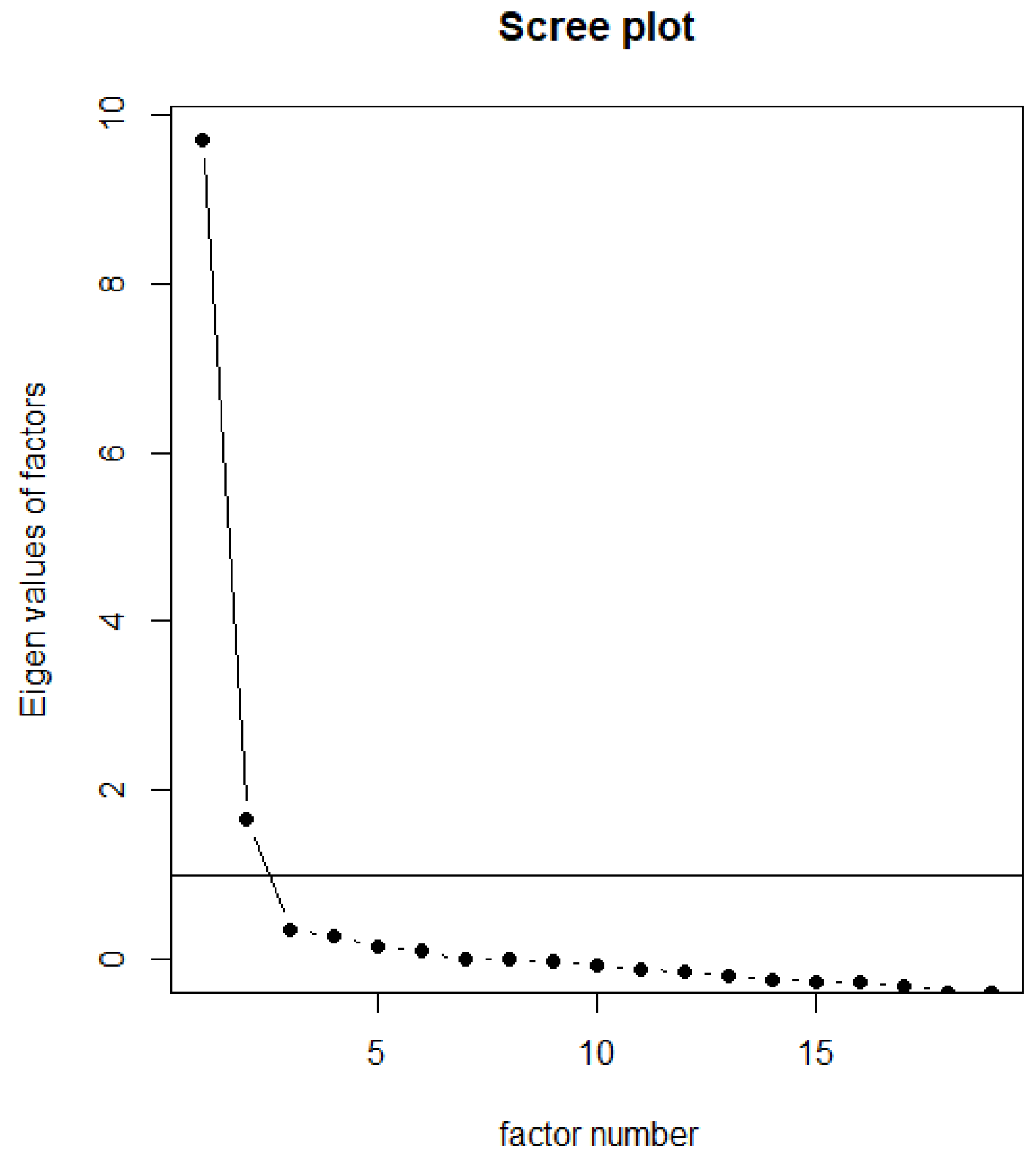

Varied statistical criteria were used to determine how many factors to retain: Kaiser criterion (two factors; eigenvalues of 10.170 and 2.201), Cattell’s scree test (two factors) (see

Figure 1), Horn’s parallel analysis (two factors), and Velicer’s MAP technique (original (1976) MAP Test is = two factors, revised (2000) MAP Test is = two factors). All criteria proposed a two-factor structure.

To interpret the factor structure, an exploratory weighted least squares factoring analysis (n1 = 278) with a direct oblimin rotation was applied. The item factor loadings of the two-factor solution, with the sum of squared loadings (SS) of 6.753 (Factor 1), and 4.167 (Factor 2) were examined. Of the 19 items, four have a factor loading of less than 0.70 (i.e., C10, SR2, SR7, and SR8). No item has a cross-loading of more than 0.25 with the other factor. Thus, 15 items were retained. The items that were deleted are shown in italics in

Table 2.

A confirmatory weighted least square mean and variance adjusted factoring analysis was performed with the second subsample (n2 = 277) in order to confirm the number of factors found in the EFA and determine whether they are independent or related to each other. A confirmatory weighted least square mean and variance adjusted factoring analysis was performed on the two-factor structure with 15 items resulting from the EFA (see

Table 3).

Several fit indices were calculated to determine whether the proposed factor structure of the EFA fits the empirical data: X

2 = 108.094, df = 89,

p = 0.082; X

2/df = 1.213; CFI = 0.975; TLI = 0.971; RMSEA = 0.028; SRMR = 0.039, with all fit indices meeting the generally accepted norms for CFA [

68]. The results of the CFA show a good fit for the initial two-factor model with collaboration (10 items) and shared responsibility (five items) as factors. Collaboration is defined as the joint interaction in the group in all activities that are needed to perform a shared task [

4]. Shared responsibility means that colleagues create a common sense of responsibility for all students’ learning [

39].

A reliability analysis was performed on the complete dataset (n = 555) to examine the internal consistency of the two factors (i.e., collaboration and shared responsibility). The newly constructed scale is found to be highly reliable, with Chronbach’s alphas of 0.949 and 0.879, respectively, for collaboration and shared responsibility as two important dimensions of the practice of team teaching (see

Table 3).

5.2. Empirical Evidence on Collaboration and Shared Responsibility in the Practice of Team Teaching (RG2)

Descriptive statistics showed teachers reported high scores on both dimensions. The dimension collaboration (10 items) has a mean score of 3.54 (SD = 0.587) on a scale of 0 to 4, and for the dimension shared responsibility (five items), a mean score of 3.05 (SD = 0.880) was found. Since the correlation between both dimensions is 0.433, a high score for collaboration corresponds to a high score for shared responsibility, and vice versa. These results indicated that teachers experience a high degree of collaboration, and a high degree of shared responsibility as two related dimensions of the practice of team teaching. Additionally, a paired sample t-test demonstrated there is a significant difference between the mean score for collaboration and the mean score for shared responsibility (t(554) = 14.167, p < 0.001). Thus, teachers reported a significantly higher score for the dimension collaboration than for the dimension shared responsibility.

5.3. Differences in Teachers’ Practice of Team Teaching across Several Groups of Teachers (RG3)

The current study attempted to establish scalar invariance for (a) teaching experience (i.e., teachers with less than five years of experience, teachers with more than five years of experience), (b) education type (i.e., pre-primary, primary, secondary, and adult education), and (c) frequency of team teaching (i.e., teachers who team teach less than once a week, teachers who team teach more than once a week).

Small changes in ΔCFI, ΔRMSEA, and ΔSRMR, and satisfying overall model results (see

Appendix B) revealed measurement invariance for the models across (a) teaching experience [

75,

76]. All changes are smaller than 0.010 in ΔCFI, 0.015 in ΔRMSEA, and 0.030 in ΔSRMR [

75,

76], which means that teachers across the studied groups interpret the developed measurement instrument in a consistent manner. Furthermore, the criteria for measurement invariance across (b) education type are met, except for the ΔCFI (ΔCFI = 0.013 > 0.010) between the scalar and metric model [

75,

76]. However, the other criteria are met (ΔRMSEA = 0.004; ΔSRMR = 0.003) and, moreover, strict invariance (ΔCFI = 0.007; ΔRMSEA = 0.002; ΔSRMR = 0.001) is established [

75,

76]. Hence, it was opted to attribute measurement invariance across education type. Lastly, small changes in ΔCFI, ΔRMSEA, and ΔSRMR demonstrated measurement invariance between the models of the studied groups based on the (c) frequency of team teaching [

75,

76].

Based on the establishment of measurement invariance across (a) teaching experience, (b) education type, and (c) frequency of team teaching, it is possible to compare the mean sum scores across these groups.

The mean scores for collaboration and shared responsibility between teachers with less than five years of experience (n = 127, Mc = 3.51, MSR = 2.98) and teachers with more than five years of experience (n = 428, Mc = 3.55, MSR = 3.07) were compared, using a two-sample t-test. Results indicate no significant differences between the two groups for both collaboration (t(210.068) = −0.750, p = 0.454) and shared responsibility (t(212.881) = −0.963, p = 0.337). This means that teachers with less than five years of experience report the same extent of collaboration and shared responsibility in comparison with teachers with more than five years of experience.

Furthermore, one-way analyses of variance with Bonferroni post hoc tests were used to compare the mean scores between teachers of pre-primary (n = 100, Mc = 3.54, MSR = 3.12), primary (n = 231, Mc = 3.49, MSR = 2.98), secondary (n = 156, Mc = 3.62, MSR = 3.06), adult education (n = 53, Mc = 3.55, MSR = 3.18). Results indicate no significant differences among the different groups for both collaboration (F(3, 536) = 1.417, p = 0.237) and shared responsibility (F(3, 536) = 1.021, p = 0.383). This means that teachers from pre-primary, primary, secondary, and adult education report the same extent of collaboration and shared responsibility.

Subsequently, the mean scores for collaboration and shared responsibility between teachers who team teach less than once a week (n = 148, M

c = 3.60, M

SR = 3.14) and teachers who team teach more than once a week (n = 407, M

c = 3.39, M

SR = 2.81) were compared, using a two-sample

t-test. Results indicate significant differences between the two groups for both collaboration (t(216.279) = 3.252,

p = 0.001, d = 0.35) and shared responsibility (t(237.401) = 3.737,

p < 0.001, d = 0.38). This means that teachers who team teach less than once a week report a significantly lower score for collaboration and shared responsibility in comparison with teachers who team teach more than once a week. Moreover, Cohen’s d effect size index indicates small differences between the two groups of teachers [

78].

6. Discussion

The impact of team teaching is determined primarily by how it is put into practice [

20]. In order to conduct further and more in-depth research on team teaching [

21], it is necessary to have an instrument that can map that effective realisation of team teaching. Therefore, the Collaboration and Shared Responsibility in Team Teaching (CSTT) scale was developed. EFA, CFA, and reliability analyses based on a large-scale cross-sectional survey dataset (N = 555) allowed the identification of two factors: collaboration (10 items, α = 0.951) and shared responsibility (5 items, α = 0.879). Collaboration is defined as the joint interaction in the group in all activities that are needed to perform a shared task [

4]. Shared responsibility means that colleagues create a common sense of responsibility for all students’ learning [

39]. The two-factor structure does fully align with the theoretically assumed two-dimensional structure [

22]. The CSTT scale makes it, therefore, possible to assess collaboration and shared responsibility as two important dimensions of the team teaching practice. The development of the CSTT scale represents an advancement in the ability to assess and understand the subtleties of the team teaching practice. This scale serves as a specific tool to systematically assess the multifaceted aspects of collaboration and shared responsibility, two crucial dimensions that define the effectiveness of team teaching. In short, the CSTT scale serves as a lens through which it is possible to identify strengths as well as areas for improvement within the practice of team teaching. Its development enriches the toolkit available to both researchers and teachers. As a result, this study fills a gap in research and also enables teachers to develop more effective practices of team teaching.

Next, the first empirical insight into the practice of team teaching was provided. The results show that teachers with team teaching experience report a high degree of collaboration, and a high degree of shared responsibility. This means that teachers can count on each other for questions and concerns and give each other emotional and professional support. They mutually trust and respect each other, are open to reflection, and give each other feedback. It also implies that teachers are both responsible for the course or courses, and for their students’ learning outcomes, well-being, and motivation. Previous research agrees that collaboration and shared responsibility can have a major impact on both teachers and students. For instance, the review study of Vangrieken, Dochy [

4] shows that although achieving teacher collaboration proves challenging, it has many benefits for teachers and students, but also for the school. A recent study by Berry [

79] indicates that a shared sense of responsibility for the education of students with disabilities can have positive effects on both teachers and students. It is particularly encouraging to note that teachers report high levels of collaboration and shared responsibility, since these are considered in the research literature as two important dimensions of the practice of team teaching [

22]. Although most teachers report a high score for both dimensions of the practice of team teaching, there are also team teachers who report a lower score for a particular dimension, or even for both dimensions. The lower level of collaboration and shared responsibility could be explained by the team teaching model used. The models of team teaching represent the ways in which team teaching is established in the classroom (e.g., observation model, parallel model, teaming model). For instance, the observation model would imply a lower level of collaboration and shared responsibility, compared to the teaming model [

14]. In the observation model, one teacher observes while the other teacher teaches the course [

13]. The focus of the observation is on the students. Further research measuring the relationship between the two could address this. The question could be raised whether it is necessary for both dimensions to score high in order to speak of quality team teaching. In our view, a lower score for one or both dimensions is not necessarily a negative sign. In this respect, it is important to emphasise that this measurement instrument is not normative, but rather seeks to reflect important dimensions of team teaching, without being all-encompassing.

Furthermore, tests for measurement invariance are reported on the two factors in the CSTT scale, providing support for configural, metric, scalar, and strict invariance by length of (a) teaching experience, (b) education type, and (c) frequency of team teaching. This means that teachers across these groups interpret the developed measurement instrument in a consistent manner. Therefore, it can be stated that the CSTT scale is a solid and robust instrument to be used with both experienced and less experienced teachers, with teachers from pre-primary, primary, secondary, and adult education, and with team teachers with both a low and a high frequency of team teaching. The CSTT scale is a 15-item scale, including 10 items to measure collaboration and five items for shared responsibility. It can be stated that its application is simple and fast, and it can be useful as a diagnostic measure, allowing the assessment of teachers’ practice of team teaching. The CSTT scale has important implications for planning teaching and learning activities that contribute to improving the practice of teaching with respect to team teaching. For example, a team teaching team could use this scale as a tool to talk about their collaboration and shared responsibility as a team. If one or more teachers report, for instance, low(er) scores on collaboration compared with others, this may indicate a need to talk about it. To go deeper into conversation, even items can be discussed more concretely. A fairly low score on the item about discussing experiences openly could spark a conversation.

As measurement invariance of the CSTT scale is established across (a) teaching experience, (b) education type, and (c) frequency of team teaching, differences between these groups could be examined. Results indicate that there are no significant differences between the groups based on (a) teaching experience and (b) education type for both collaboration and shared responsibility. There are, however, significant differences between groups in terms of the (c) frequency of team teaching. Teachers who team teach less than once a week experience less collaboration and shared responsibility with their team teaching colleague(s), compared with teachers who team teach more than once a week. This finding suggests that teachers who frequently engage in team teaching experience more collaboration and shared responsibility.

Having conducted one of the first large-scale quantitative survey studies on team teaching, this study presents an instrument (i.e., the CSTT scale) to measure two important dimensions of the practice of team teaching. The development of this instrument is an important contribution to the field as it makes all kinds of new avenues of research possible to further investigate the practice of team teaching. Further research can, for example, investigate the relationship between the practice of team teaching and teachers’ effective teaching behaviour. The first empirical insights show that team teachers experience a high degree of collaboration and shared responsibility. Additionally, the frequency of team teaching influences these dimensions of the practice of team teaching.

This study is not without limitations. First, although there are good theoretical reasons to believe that the practice of team teaching can be further conceptualised as collaboration and shared responsibility [

22], other conceptualisations are also possible. For example, further research could take other dimensions such as team similarity, team efficacy, and team potency into account, as team teaching is a complex concept.

Second, it is necessary to be aware that the outcomes of the CSTT scale remain self-reported data. This implies that teachers’ answers may have been influenced by social desirability, as is a risk with any form of subjective data collection [

80]. However, throughout the process of survey development and administration, several steps were taken to reduce social desirability bias. This included an expert review and a pilot study. Future research should combine this data with other data collection methods, such as observation or interview data. Results from other data collection methods can verify the validity of the CSTT scale.

Third, although the sample met all criteria required to develop the questionnaire, it solely consists of Flemish schools. This limits our claims to the generalisability of the questionnaire and the results to other contexts. Therefore, future research is encouraged to translate, adapt, and validate the CSTT scale in other educational settings. Moreover, the translation of the CSTT scale into different languages and its validation in different contexts will offer opportunities for additional and comparative research on the practice of team teaching in other regions and contexts. To facilitate this, the original Dutch version and an English translation are included as an Appendix. Authors should discuss the results and how they can be interpreted from the perspective of previous studies and of the working hypotheses. The findings and their implications should be discussed in the broadest context possible. Future research directions may also be highlighted. To adapt and use this scale in different cultures, contexts, and countries, researchers are advised to adopt a systematic process that takes into account both linguistic and cultural nuances. This procedure requires an extensive reiteration of the previously completed steps of this study, carefully considering linguistic and cultural nuances. Initially, the scale should be translated so that the essence of its constituent items is preserved. Next, pilot and/or expert testing is crucial to uncover possible language or comprehension problems. Finally, psychometric assessments must be conducted to determine the reliability and validity of the adapted scale.