Abstract

The aim of this work was to validate an empirical model that integrates the different motivational categories that explain the decision to become a teacher. This work provides empirical evidence of the psychometric quality of the instrument used, CUMODE. On the basis of this instrument, a structural model is validated that integrates the different types of motivations associated with teaching. The participants in the study were 228 active teachers and 389 trainee teachers. An exploratory factor analysis (EFA) was applied to the data in order to extract their structure. Cronbach’s test was used to analyze the internal consistency of each item. The results showed an adequate KMO index of 0.907. The third refined model consisted of 14 items and obtained adequate fit indexes: χ2 (df = 129) = 2.74, CFI = 0.94, GFI = 0.88, RMSEA = 0.09 (90% CI = 0.07–11), and SRMR = 0.07. Finally, a confirmatory factor analysis was applied with a sample of trainee teachers to validate the model. The model is equally valid for the sample of trainee teachers.

1. Introduction

By 2030, countries will need to recruit a total of 68.8 million teachers []. Across Europe, education systems are facing a crisis in this profession, and many countries are experiencing a shortage of well-qualified teachers []. These documents from official institutions point out that the teaching profession has been going through a professional crisis for some years now, making it unattractive to young people. Many European education systems are suffering from a shortage of teachers, and national and European policymakers are seeking to identify the factors that are turning this profession into an increasingly unattractive one.

The dizzying changes that we are facing represent such a challenge for teachers that the Council Resolution for European cooperation in the field of education and training includes the improvement of competencies and motivation in the teaching profession as one of the priority strategies for the period 2021–2030.

The proposals that are being formulated at an international level are oriented towards reforms and new policies in areas such as initial teacher training, continuing professional development, working conditions, teaching careers, and teacher evaluation and well-being. In addition, in order to design effective policies, evidence is needed on “what works and under what circumstances”.

It is obvious that motivated teachers are one of the essential requirements for an education system in which students from diverse backgrounds can thrive and reach their full potential.

In Spain and the Canary Islands, there have been changes in educational legislation that have led to an increase in administrative requirements and significant curricular and methodological adjustments for better attention to the diversity of students in increasingly inclusive classrooms. All of this is supported by the motivation and effort of an increasingly exhausted teaching staff. It should be noted that, during the 2020 pandemic, the last law on education (LOMLOE) was passed.

We understand that this is not a local or even a national situation, but a global one, in a VUCA (Volatile, Uncertain, Complex, and Ambiguous) world that sets challenging educational contexts, greatly diminishing the attractiveness of the teaching profession and career. We find the perspective of the ET 2020 Working Group on Schools to be timely, which calls for a change of approach that consists of moving from the vision of teaching as an isolated, confined, and one-dimensional profession to teaching as an interconnected role with a large family of school education professions, allowing each individual to evolve towards multiple, diversified, and enriching career paths [].

Teachers are fundamental for social transformation, as they are direct agents in helping citizens [] to urgently face the challenges of a vulnerable society and the systemic adversities presented by this context of increasing complexity. It is therefore necessary to ensure conditions for the well-being of teachers, particularly regarding their mental health, since this is the basis for teacher–student relationships and teaching–learning processes under normal conditions, but even more so under complex and changing conditions [].

Motivation plays a modulating role in the choice of the profession, as well as in the permanence in it, in the improvement and acquisition of new learning and skills, and even in the emotional adjustment []. Thus, it is crucial not only to identify the different types of teacher motivations but also to understand the relationships they maintain with other socio-professional variables since the source of a person’s motivation (whether intrinsic or extrinsic) is a key predictor of how committed he/she is to a task and will therefore be a condition for them to perform it well [].

In the last decade, there has been a significant increase in the research on teacher motivation. In such studies, teacher motivation has been revealed as a crucial factor that is closely related to a number of psychoeducational variables such as student motivation, educational reform, teaching practice, and the achievement and psychological well-being of teachers []. The notion that the motivational beliefs of these professionals are “complex, multifaceted and varied” is not new [] (p. 486). This is clearly related to the fact that psychological science has not yet reached a consensus in the understanding of motivation []. Therefore, before presenting the research on teachers’ motivations, we provide, below, a synthesis of the general theoretical approaches that have been carried out in the field of motivation psychology.

1.1. Motivation as a Reference Psychological Construct

The first proposals were rather general, as they did not specifically address motivation as such; instead, they were focused on the general laws of human behavior. In this field, the behaviorist and the psychoanalytic school stood out. Therefore, we are talking about motivation linked to several concepts, such as drive (impulse and need) or arousal (energy) [,,,,]. These movements consider motivations to be the primary needs of the human being, involving variables related to the biological level, sensory experiences, and impulses. These impulses seek to reestablish the internal balance and to satisfy this need, which, if achieved, disappears and the organism returns to its initial state. Hence, the motives would be instruments through which the organism satisfies its needs, returning afterwards to the initial state of balance [].

Particularly, the first behavioral theories emphasized the limited capacity of people to choose their behaviors and, consequently, the low participation capacity of individuals. In addition, these behaviors were externally regulated through rewards (positive behaviors) or punishments (negative behaviors), and different methods were applied in order to modify the behavior, considering the behavior that needs to be reinforced; the appropriate motivators; and the immediacy, quantity, and novelty of the reinforcement [,,].

As a response to the behaviorist theories, the humanistic approach appears, introducing certain topics, such as self-fulfillment, growth, and personal development. This perspective focuses on the capacity of each person to achieve his or her own growth, develop positive characteristics, and give himself or herself the necessary freedom to achieve his or her goals. While psychoanalysis or behaviorism focused on the conception of the person as a passive being, Maslow proposed a humanistic approach based on the proactive potential of the human being, directed towards personal and social fulfillment through the drive for self-actualization [,,,]. This author, in his theory of human motivation, describes the factors and needs that motivate each individual, hierarchizing the needs according to survival or motivation capacity in such a way that, when one need is satisfied, another one emerges, also changing our behavior (Maslow, 1943). He distinguishes between shortfall needs, on one hand, and the developmental needs of the self, on the other [,,].

Among the shortfall needs, we find physiological needs, security, love, belonging, and appreciation, whilst those related to the development of the self include the needs for personal and social fulfillment. The difference between these two categories lies in the fact that the former is related to a deficiency, while the developmental needs of the being are linked to the set of actions of the individual that allow him/her to develop his/her own potential, relating to his/her own self-esteem [,,]. Subsequently, Clayton Alderfer (1969) reviewed Maslow’s theory of needs and categorized them into three groups: existential (physiological and for security), relational (interpersonal or social relationships), and growth (personal creativity) [,]. This triarchic model of needs is the one we used to categorize the incentives that guide teacher motivation [,].

Meanwhile, cognitive theories are based on mental processes that help individuals to achieve higher levels of performance, aiming to understand the mental process that will impact human behavior before starting a task []. Among these processes, factors such as goals, self-efficacy, and expectations stand out, as well as processes of control, action, and self-regulation in behavior [,,].

These processes come into play, unlike the different types of motivation pointed out by Deci and Ryan (1985), which the authors refer to as “self-regulatory styles” [,,,]. The various types of motivation identified by the authors are demotivation, extrinsic motivation, and intrinsic motivation. Demotivation is associated with non-regulation, while at the opposite end, intrinsic motivation involves the internal regulation of behavior, indicating that the degree of autonomy, confidence, and flexibility increases as the behavior becomes more internalized and integrated []. All of these internal processes play a crucial role in the choice of the teaching profession and in the development of the essential skills to exercise it [,].

1.2. The Study of Teacher Motivation

Teacher motivation represents a central element of the professional competence of this group [,], and its impact on the effectiveness of teaching and the academic development of students has been studied [,,]. The need to address teacher motivation also stems from the shortage of educators reported by many Western countries, including the United States; Australia; and some other European countries, such as the United Kingdom, Germany, and Norway []. A renewed research interest in teachers’ motivation to teach and to continue teaching has highlighted possible causes of existing and potential teacher shortages, such as the early burnout of teachers, aging teaching force, imbalance of high demand and less rewards, limited career opportunities, less job security, and low prestige [].

There are studies that support the highly vocational nature of the teaching profession, since, for teachers, their main motivator is the student body. They teach because they enjoy working with young people and helping them with their education and feel great satisfaction in seeing how students learn with their help, develop their potential, and prepare themselves to become responsible adults [,,,,,]. Thus, Project Teacher 2000 researchers, using data obtained from three thousand teachers across four countries, report that teachers in all countries are motivated by a desire to work with people and find high satisfaction in this aspect of teaching [].

Perhaps most importantly, teaching is inherently an interpersonal and caring effort rather than just a personal one []. Different studies have shown that teachers point out that their various motivations to work with students and contribute to their development are the main reasons for choosing to become education professionals []. These aspects are influenced by student engagement, the satisfaction of basic psychological needs, and the teacher’s self-determination and motivation [,,]. Professional well-being in teachers is linked to certain aspects, such as job recognition, personal fulfillment, professional affiliation, teacher relationships with educational agents, and personality characteristics [,,]. These aspects are influenced by students’ commitment, the satisfaction of basic psychological needs, and the teacher’s self-determination and motivations [,].

The journal Learning and Instruction devoted a monograph to teaching motivations (Learning and Instruction, vol. 76, 2021) as a way of bringing together research articles on this topic, in part due to the lack of convincing theoretical conceptualizations [].

As Lazarides and Schiefele (2021) point out, in the last ten years, the line of research on teachers’ motivations has been consolidated as an area of investigation, as the number of articles that directly include the term “teacher motivation” in their title increased more than sevenfold after 2008. This significant growth in the number of contributions has provided empirical evidence of the importance of teacher motivation for the well-being of the teaching staff, teaching quality, and student motivation [,]. Moreover, it provides valid measures for a wide variety of teacher motivation models, which has led to the conclusion that it is a multifaceted and complex theoretical construct [,,].

Particularly, the focus of the research has moved beyond the question of whether teachers’ motivations are important to the instructional process or why and how they are important for both teachers and students. Specifically, it is well known that teacher motivation is highly relevant to teaching quality, teacher well-being, and student motivation and achievement [,].

Specifically, one of the aspects that has attracted the greatest attention in research is teachers’ self-efficacy [,,]; however, related motivational constructs, such as teacher responsibility, have received less attention, despite evidence showing that both constructs predict similar outcomes [,,,].

We focused our research on the theories and dimensions of teaching motivation. Ref. [] highlighted two dimensions: the motivation to teach and the motivation to stay in this occupation. Meanwhile, studies conducted by European and U.S. academics classified teachers’ motives for choosing a teaching career into three categories: extrinsic, intrinsic, and altruistic motives [,,,]. Extrinsic motives involve aspects that are not inherent to the immediate job, such as salary, status, and working conditions. Intrinsic motives embrace the inherent aspects related to the meaning of teaching and the passion for teaching, subject knowledge, and experience, whilst altruistic motives involve the perception of teaching as a valuable and important profession and the desire to support children’s development, as well as improve society [,].

However, it should be mentioned that all the articles included in the abovementioned review [] refer to the construct of teacher motivation related to the variables of student academic performance and the quality of teaching perceived by students, as well as the relationships between teachers’ motivation profiles and teaching practices.

1.3. The Evaluation of Teacher Motivations

First, it should be noted that much of the literature that has been reviewed on evaluative instruments of motivation in education has been centered on student motivations [,]. When teacher motivation has been specifically addressed, authors have focused on the appropriateness of the forms of motivation and their effect on the students, from the perspective of the theoretical line of teacher effectiveness [].

At a more specific level, it should also be pointed out that research on teachers’ expectations and motivational attitudes has been addressed through questionnaires such as the AMOP [].

When it comes to the evaluative instruments used to capture teachers’ motivations, the use of the FIT-Choice scale stands out. After its publication in 2006 in the Asia-Pacific Journal of Teacher Education (APJTE) [] and its further technical validation in 2007 [], researchers around the world began to request permission to use it in their own contexts to conduct studies on the motivation to choose a teaching career. The motivational factors that are measured in this scale include variables such as social influences, previous positive teaching and learning experiences, perceived teaching abilities, intrinsic value of personal and social aspects, and satisfaction with the choice of teaching as a profession, as well as perceived task demands, such as the experience and difficulty of performance, and rewards, such us social status and salary [].

Another tool that has been used is the Situational Motivation Scale (SIMS), which was designed by Guay, Vallerand, and Blanchard (2000) to evaluate the constructs of intrinsic motivation, identified regulation, external regulation, and demotivation in both field and laboratory environments [].

However, we should be aware that this instrument is not specifically oriented towards evaluating teachers’ motivations, so it does not include the reasons for choosing and remaining in the teaching career []. It has been widely used to assess learners, and there are versions in Portuguese [,,].

The questionnaires, inventories, and scales that are located in the theoretical review we carried out [,] focus on measuring the motivation of the teaching population from the perspective of self-efficacy, as well as professional competencies and skills to motivate students. These types of instruments are linked to the Self-Determination Theory and isolate aspects such as teaching expectations and achievement motivation of teachers. They differ from the objectives of our research, which are more related to the motives that lead active teachers and student teachers to stay, train, and develop their teaching career and vocation from the perspective of the basic needs covered by the teacher.

After widening our review with WOS search engines, we found two inventories applied to teachers: One, which focused on work motivation, is The Work Tasks Motivation Scale for Teachers by Fernet et al. (2008) and was validated for the Spanish context by Ruiz (2015). The other, developed by Valenzuela et al. (2012), measures teachers’ self-efficacy in generating school-related motivations in students [,].

None of them responds to the interests of our research, since they do not provide factors focused on the motives that cover the different types of needs (security, affiliation, and fulfillment) that teachers possess when teaching and that, therefore, guide their decisions as educational professionals. For this reason, we believed it was necessary to provide a new evaluation instrument, the CUMODE, with the psychometric guarantees required to empirically collect the motivations of the teaching staff.

In our case, we intend to approach the study of teachers’ motivations with the purpose of subsequently relating it to the emotional adjustment of the teaching staff, setting aside the main direction of the studies that refer to their effect on the results of their teaching.

However, to achieve this, it is necessary to isolate and categorize the different reasons that drive someone to make the decision to become a teacher, so that we can relate the isolated factors to the influence on their affective well-being.

Therefore, the aim of this work was to validate an empirical model that integrates the different motivational categories that explain the decision to become a teacher. In addition, we aimed to study their relationship with socio-academic variables such as gender, educational stage, years of teaching experience or the condition of being an in-service versus in-training teacher.

This paper provides empirical evidence of the psychometric quality of the instrument used. Based on this instrument, a structural model that integrates the different types of motivations associated with the teaching condition was validated, as well as the results of its relationship with a set of professional and academic variables.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

Participants in the study were 228 active teachers and 389 trainee teachers. The sample of practicing teachers is made up of 71.9% women and 28.1% men, age ranges from 20 to 65 years, with an average of 40.5 years. The majority of them (76.3%) belongs to the province of Santa Cruz de Tenerife. The different stages in which they teach are early childhood education (7.9%), primary (70%), early childhood and primary (16.3%), and secondary school (4.8%), in both public (57%) and private (43%) centers. The range of teaching experience of the participants is between a few months and 40 years: 32% of them have between 0 and 5 years of experience, 36% between 6 and 18 years, and the remaining 32% between 19 and 40 years (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Description of active teachers.

Regarding the sample of trainee teachers, it consists of 57% women, 37.5% men, and 4.7% who identify with another gender. The 69.7% of the sample are students of the Primary education degree and 30.3% are students of the Master of Teacher Training (Secondary School) (see Table 2).

Table 2.

Description of the teachers in training group.

2.2. Instruments

The instrument used was the Teaching Motivations Questionnaire (CUMODE) for active professionals. To create this questionnaire, we started with three open-ended questions: What are the incentives you get by working as a teacher? What are the needs that you satisfy being a teacher? What is the true intimate and personal motivation that maintains your decision to continue dedicating yourself to teaching?

After the content analysis, the answers obtained were included in three theoretical categories: professional well-being, social bonding, and teaching fulfillment. From here, a questionnaire with 34 sentences was designed, trying to have the same number of items in each category. This initial questionnaire, which is included in Appendix A, was completed by a sample of active teaching staff. An exploratory factor analysis (EFA) was applied to the data to extract their structure, and the analysis of Cronbach’s Alpha coefficient was used to analyze the internal consistency of each item. From this first analysis, 11 sentences were eliminated since they were dispersed in different components; at the same time, their elimination increased their reliability. Therefore, a questionnaire of 23 sentences was obtained that included different reasons for deciding to be a teacher. The response format used was a Likert-type format, from 1 to 7, in which the participants indicated the degree of identification with each of the sentences (1 = I do not identify myself; 7 = I totally identify myself). Once the factorial structure was obtained, the corresponding confirmatory analysis was carried out, and 9 sentences were eliminated to obtain a better adjustment of the model. As a result, we obtained a questionnaire with 14 sentences that is included in Appendix B. Finally, confirmatory factor analysis was applied with a sample of teachers in training, with the aim of validating the model.

2.3. Procedure

The questionnaires were distributed, through a Google form, to those teachers who wanted to participate. The questionnaires were completed voluntarily, and the consent, anonymity, and privacy of the data were taken into account. They were also distributed in the same way to the students of Primary Education Degree, Early Childhood Education Degree, and the Master’s Degree in Teacher Training. The data obtained were included in an Excel template for subsequent inclusion in the SPSS v.26 statistical program database, and the corresponding data analysis, AFE, and analysis of Cronbach’s Alpha coefficient were performed. The AMOS v.23 structural equation model software was used for the confirmatory analysis.

2.4. Analysis of Data

To answer the research objectives and questions, a principal component analysis was performed to extract the factor structure of the instrument, and the analysis of Cronbach’s Alpha coefficient was used to establish their internal consistency. Subsequently, a confirmatory factor analysis was performed. All of this was performed with the statistical package SPSS v.26 (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA, 2025) and with the structural equation model software AMOS v.23 for confirmatory factor analysis.

3. Results

The results are presented based on the analyses performed. Firstly, the purification of the database is described; secondly, we describe the exploratory factorial analysis and internal consistency; and, finally, the analysis of the factorial structure of the questionnaire of the two samples analyzed is detailed.

3.1. Data Cleaning

The database was cleaned to ensure the quality and validity of the results obtained in subsequent statistical analyses, as well as to determine the need for variable transformation. To achieve this, the removal of outliers and a univariate normality analysis were carried out.

On the one hand, from the initial sample of 228 participants, 20 people who had not completed the teachers’ motivations questionnaire were eliminated, so that 208 remained. In the mentioned sample without missing values, the Mahalanobis distance was calculated [] for the questionnaire items, and the Chi-square test was applied. The results showed a total of 12 people with atypical or extreme scores, which were eliminated from the database, leaving a total sample of 196 participants for subsequent analysis.

On the other hand, the normality of the items was analyzed from the typical scores of asymmetry and kurtosis. As Table 3 shows, all the statistics were in the range of ±1.96, except for the kurtosis of item 31, so the normality criterion was met, and it was not necessary to transform the data [].

Table 3.

Item skewness and kurtosis.

3.2. Exploratory Factor Analysis

After selecting the final 18 items to be included in the instrument, an exploratory factor analysis (EFA) was carried out to define a first factorial structure. Starting from the theoretical independence of the factors that was verified in the correlation matrix of the items, the varimax rotation was used [].

The results showed an adequate KMO index of 0.907 [] and the distribution of the items in three factors, which correspond to the factors proposed at a theoretical level. Table 4 shows the factorial weights obtained from each item in the corresponding factors, with coefficients less than 0.30 being suppressed. Both items 10 and 17 were included in the Linkage factor for theoretical reasons that are related to the development of the construct. Regarding the variance of the components, the teaching fulfillment factor explains 38% of the variance, the well-being professional factor explains 25%, and the social bonding factor explains 6%.

Table 4.

Results of the AFE with the 18 items of teacher motivation.

In Table 4, the factorial weights obtained from each item on their respective factors are reported, with coefficients less than 0.30 being suppressed. Both item 10 and item 17 were included in the Linkage factor due to theoretical considerations related to construct development. Concerning the variance of the components, the teacher fulfillment factor explains 38% of the variance, the well-being factor explains 25%, and the social bonding factor explains 6%.

The rotated components consist of the teaching fulfillment, composed of 10 items related to teacher motivation, so that their students not only learn school content but also emotional aspects and they develop morally and personally, in addition to the need to be useful to the students or the satisfaction of being with them. This component also includes aspects related to the teacher’s self-realization, which is focused on the vocational nature of his/her professional choice or the satisfaction that sharing projects with other teachers produces (Component 1). A second factor (Component 2) is related to aspects associated with professional well-being, such as job stability, salary, time availability, or vacations. Finally, Component 3 refers to reasons associated with the category of social bonding, related to the social support of students’ families or feeling related to their students and being part of a team of peers.

3.3. Analysis of the Factorial Structure

Based on the relationships founded between the items in the exploratory factor analysis, the model was tested using the confirmatory factor analysis (CFA), as it is the recommended method for instrument validation []. The AMOS v.23 structural equation model software was used to test the theoretical model of three factors: (1) teaching fulfillment, (2) professional well-being, and (3) social bonding through the bank of 23 items.

Before proceeding to the CFA, multivariate normality was explored, as it is a requirement for model estimation. For this, the Mardia coefficient was observed, which was 23.405. Since the statistic is less than p (p + 2), we can talk about the existence of multivariate normality and proceed to the analysis []. The maximum likelihood method was used to estimate the model, since the Mardia coefficient was not higher than 70 [].

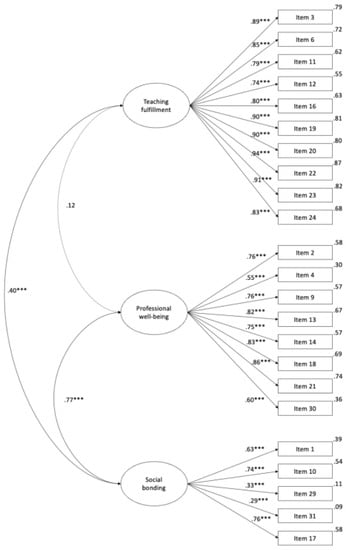

The first model that was tested (Figure 1) consisted of 23 items and did not present a good fit, according to the Hu and Bentler (1999) criteria: χ2 (df = 227) = 4.68, CFI = 0.79, GFI = 0.63, RMSEA = 0.13 (90% CI = 0.12–0.14), and SRMR = 0.16. Five items with high modification indices were removed from the model [].

Figure 1.

Model 1 of 23 items with standardized estimates. Note. *** p < 0.001.

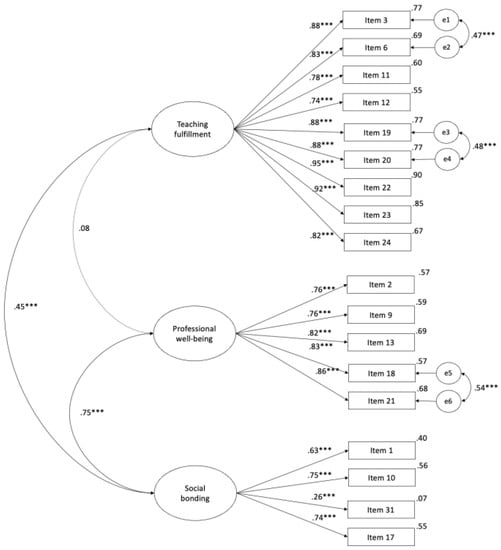

The second model (see Figure 2) consisted of 18 items, and, despite correlating errors based on the modification indices, it did not obtain adequate fit indices either []: χ2 (df = 129) = 3.40, CFI = 0.89, GFI = 0.81, RMSEA = 0.11 (90% CI = 0.10–0.12), and SRMR = 0.09. Taking into account the modification indices, four items were eliminated, as well as those items with a factorial weight of less than 0.30 [,].

Figure 2.

Model 2 of 18 items with standardized estimates. Note. *** p < 0.001.

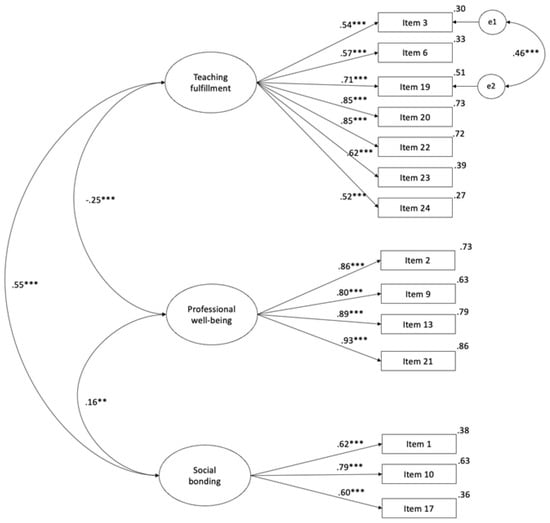

The third refined model (see Figure 3) consisted of 14 items and obtained adequate fit indices: χ2 (df = 129) = 2.74, CFI = 0.94, GFI = 0.88, RMSEA = 0.09 (90% CI = 0.07–11), and SRMR = 0.07. Thus, this model was adequate and can be considered valid.

Figure 3.

Model 3 of 14 items with standardized estimates. Note. ** p < 0.01. *** p < 0.001.

Table 5 shows the descriptive factors of teacher motivation, as well as the reliability analysis of each one. The indices obtained presented adequate internal consistency, which is greater than 0.70 for all factors.

Table 5.

Descriptive statistics teacher motivation factors.

Likewise, the correlations between the factors of the scale, collected in Table 6, were calculated. It should be noted that the correlation between teaching fulfillment and professional well-being was not significant (p = 0.540).

Table 6.

Pearson correlations between scale factors.

3.4. CFA Students

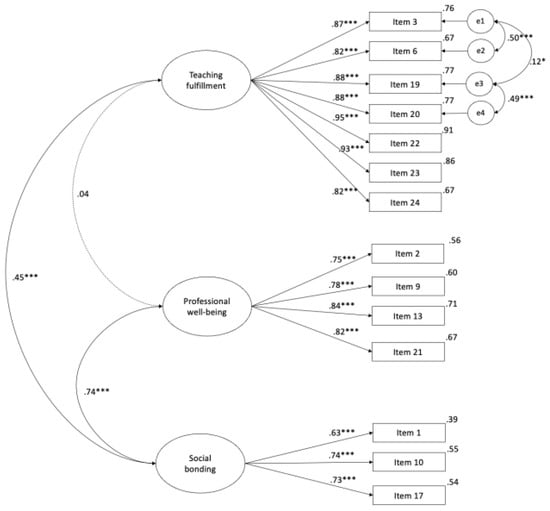

To check the validity and consistency of the 14-item model defined with active teachers, a CFA was carried out with a sample of university students from the education area (N = 389).

Before testing the model, data filtering was carried out following the same scheme as in the previous study, starting with an initial sample of 425 participants, which resulted in 389 after eliminating blank responses (n = 13) and outliers (n = 23). Likewise, the normal nature of the data was verified from the analysis of the skewness and kurtosis of the typical scores of the items (see Table 7), as well as the Mardia coefficient of 20.941.

Table 7.

Skewness and kurtosis of typical item scores in students.

The results of the CFA in the student sample (see Figure 4) were adjusted to the Hu–Bentler criteria, so that it can be considered that there is a good fit of the model: χ2 (df = 72) = 4.31, CFI = 0.91, GFI = 0.89, RMSEA = 0.09 (90% CI = 0.08–10), and SRMR = 0.08. It should be noted that, in the case of students, a significant correlation was found between teaching fulfillment and professional well-being, unlike in the model with workers.

Figure 4.

CFA of the 14-item model with students. Note: The graphical representation of the model with standardized estimates of the factorial weights. The errors associated with the items in the representation were not included for greater clarity of the model, except for those that were correlated. Dotted lines indicate non-significant relationships. * p > 0.05. *** p < 0.001.

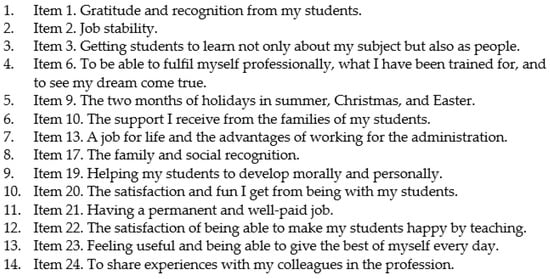

Finally, we obtained a questionnaire with 14 items, which are described in Figure 5 and presented in Appendix B.

Figure 5.

The final items in the Motivation Questionnaire (CUMODE).

Therefore, the model of the 14-item Teacher Motivation Instrument could be considered adequate for both active teachers and students, as can be seen in Table 8.

Table 8.

Goodness-of-fit indices of the CFA of the Teacher Motivation Instrument in workers and students.

To conclude the results section, we present Table 9 with the most relevant results.

Table 9.

Summary of main results.

4. Discussion

This article seeks to isolate the motivations that support the decision to become a teacher, with the interest of analyzing the types of needs that teachers satisfy when they exercise their profession.

To this end, an instrument that collects the incentives that teachers plan to achieve was validated, given the lack of evaluative tools on this subject in the scientific literature.

The first achievement of this work is to have obtained a questionnaire with the necessary psychometric guarantees to empirically collect the motivations of the teaching staff.

Using this tool, we were able to validate a structural model with which to categorize the motives that teachers have for teaching and that guide their decisions as educational professionals. Having the added value that this factorial structure not only applies to the group of practicing teachers but also to those who are in the training process to become teachers.

The empirical model we reached indicates that the teaching motivations of both active teachers and those in training are organized around three major factors that coincide with the three theoretical categories we started from. Specifically, these are the following: as the first factor, due to the weight of the variance that has been explained, we have the factor we call “teaching fulfillment”, which includes incentives associated with the educational mission that defines teaching and which, therefore, is oriented to the improvement of students and to achieving their integral learning (cognitive, emotional, and moral). It would also include aspects with a clear vocational value, such as the satisfaction of being able to exercise the teaching profession and to do so while participating in collective projects.

A second important factor, but with a lower factorial weight compared to the previous, is the factor we called “professional well-being”, which is made up of aspects related to the employment guarantees that make teaching possible, such as job stability, salary, and time availability or holidays.

Finally, we have a third category of incentives that cover affiliative needs and that we therefore call “social bonding”, made up of aspects that have to do with the satisfaction that teachers derive from their relationship with those they interact with in the school system: students, the students’ families, and their colleagues.

It should be pointed out, as a relevant fact for the interpretation we make later in this paper, that this last factor explains a very low proportion of the variance that has been measured, if we compare it with that of the other two factors that make up the model.

What has been discovered through the results obtained in our research is related to the literature that was reviewed.

In the first place, there is a clear link with Abraham Maslow’s humanistic model, which groups motivations into three main categories: existential (physiological and security), relational (interpersonal or social relationships), and growth (personal creativity) [].

Although other studies have organized teachers’ motives under different names, such as extrinsic, intrinsic, and altruistic motives [,,,], we believe that there is a relative parallelism, as extrinsic motives involve aspects that are not inherent to the immediate job, such as salary, status, and working conditions. In our case, this would be related to the professional well-being factor.

Intrinsic motives, which are those that embrace aspects that are associated with the meaning of teaching, and altruistic motives, which involve valuing the profession as a means of student improvement and social change [,], have been grouped within the factor that we called “teacher fulfillment” in our model.

It is worth mentioning that our work confirmed the highly vocational nature of the teaching profession, a factor that has been isolated by other authors [,,]. These researchers have identified, as a primary motivational source, the work with students, the satisfaction caused by their learning, and the development of their potential as future adults as a direct effect of their educational support.

This finding coincides with the results reported in Project Teacher 2000 which indicate that teachers in all countries included in this study are motivated by the desire to work with people [].

Likewise, researchers from different national backgrounds have shown that teachers prioritize, as their main reasons for choosing to become education professionals, the motivations to work with children and contribute to their development [,].

In terms of conclusions, it is important to highlight that the triarchic structural model of teachers’ needs that was found presents an unbalanced distribution regarding the relevance of each factor since, in the categories of fulfillment and well-being, the proportion of variance explained by the latter is relevant, while the explanatory contribution to the model of social bonding is rather secondary.

We consider these data to be of particular importance for drawing inferences about how teachers’ needs are distributed when orienting their decisions to satisfy them and the possible effects of these motivational priorities on their emotional health. This is especially the case if we take into consideration the weight that interpersonal relationships have on people’s subjective well-being [].

Another conclusion refers to the relationship between the factors of the model. In the case of the sample of active teachers, although the correlation between fulfillment and bonding is significant, it is no longer so when we relate fulfillment and well-being. This significant result does appear in the sample of teachers in training, and it indicates that, while for practicing teachers, their fulfillment is not associated with their working conditions, for apprentice teachers, their personal well-being is closely related to their educational mission and professional vocation.

We consider these findings to be of particular relevance, given that the present study aimed to address the motivations of teachers in order to subsequently relate them to the emotional adjustment of this professional group.

Our hypothesis is that it is, indeed, the weight exerted by motivations and their lack of relationship (in the case of active teachers) with professional well-being and the low relevance given to the support network of interpersonal bonds are what make teachers more emotionally vulnerable, especially those oriented towards their educational function of helping and promoting their students.

The abovementioned ideas connect with previous studies that found relationships between professional well-being and certain aspects, such as job recognition, personal fulfillment, professional affiliation, teachers’ relationships with educational agents, and personality characteristics [,,].

In any case, it should be noted that it would be necessary to replicate this research with a larger sample of active teaching staff that includes a balanced representation of teachers from different educational levels, since, in this study, the presence of preschool and secondary school teachers, compared to primary school teachers, is not balanced.

In the section on the limitations of the study, we should point out that the group of subjects evaluated is not representative, either in terms of the total number of subjects or in terms of their balanced distribution in the different educational stages; therefore, it would be necessary to replicate this research with a larger sample of the active teaching staff that includes a balanced representation of the teaching staff from the different educational levels, given that, in this study, the presence of preschool and secondary education teachers, compared to those from the primary stage, was unbalanced.

As for future perspectives and lines of continuity, our study provides a first approach to the whys and wherefores of the teaching profession in the interest of drawing a motivational map that will help us understand the decisions they make regarding their professional career and their educational vocation. For this reason, it will be necessary to make progress in gathering, extensively, the motivations that underpin the teaching profession of a broad and diverse sample of teachers from different sociocultural contexts, both in Spain and in other countries.

Along with the above, it would be very interesting to study the relationships of the isolated factors in our structural model with other psychoeducational variables, such as, for example, teachers’ emotional competences or affective adjustment, equally with socio-academic variables, such as gender, educational stage, or years of teaching experience, among others.

Finally, it is particularly important to clarify the possible influence of teachers’ motivational profiles on their mental health and the weight of the factors in our structural model in predicting whether a teacher is more or less emotionally vulnerable. This predictive factor of motivational and emotional factors will help us not only to understand their influence but also, in a preventive way, to design selection and training processes that contribute to the improvement of the teaching profession.

We believe that further study of this topic will help us to address the reality of the shortage of teachers that is being experienced in Western countries [] as a result of the problems that discourage people from deciding on and/or remaining in the teaching profession, such as early burnout, less job security, or the tendency to suffer emotionally [].

The aim of this work is to ensure that the profession not only brings teachers a sense of providing a social service and helping the educational community but also brings with it protection, support, and recognition for good teachers.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.R.R.-R. and A.F.R.H.; methodology, C.M.H.-J. and I.D.-L.; software, C.M.H.-J. and I.D.-L.; validation, I.D.-L. and formal analysis, C.M.H.-J. and I.D.-L.; investigation, E.R.R.-R., A.F.R.H. and C.M.H.-J.; resources, C.M.H.-J. and I.D.-L.; data curation, C.M.H.-J. and I.D.-L.; writing—original draft preparation, E.R.R.-R. and A.F.R.H.; writing—review and editing, E.R.R.-R. and A.F.R.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee on Research and Animal Welfare (Comité Ético de Investigación y Bienestar Animal) (CEIBA) of the University of La Laguna (protocol code CEIBA2022-3214 and date of approval: 16 January 2023).

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient(s) to publish in this paper in Appendix A and Appendix B.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A. Cuestionario de Motivaciones Docentes (33 Ítems)

Para poder recoger estos datos es necesario contar con su consentimiento informado, el cual se dará por aceptado con la mera cumplimentación y posterior envío de este cuestionario. Para garantizar la completa confidencialidad de los datos obtenidos se ha tenido en cuenta la Ley Orgánica 3/2018, de 5 de diciembre, de Protección de Datos Personales y garantía de los derechos digitales.

- Si tiene cualquier pregunta sobre la encuesta, envíenos un correo electrónico a: emocreaull2@gmail.com

- Habiendo sido informado/a de los detalles de este cuestionario, ¿da su consentimiento voluntario para su cumplimiento?.SÍNO

- CUESTIONARIO DE MOTIVACIONES DOCENTES.

En el siguiente cuestionario, presentamos un conjunto de sentencias que contestan a la pregunta ¿POR QUÉ SOY DOCENTE? La tarea consiste en valorar, en una escala de 1 a 7 (siendo 1= NADA y 7= MUCHO), cuánto te identificas con cada una de esas razones. Se trata de que señales en qué medida estas expresiones se ajustan a las motivaciones actuales que mantienen tu decisión de ejercer como docente.

Todos los motivos que aparecen son igual de legítimos, así que te rogamos que respondas sin sentirse condicionado/a por el “qué dirán”, son tus motivaciones y no tienes por qué justificarlas.

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | |

| |||||||

| |||||||

| |||||||

| |||||||

| |||||||

| |||||||

| |||||||

| |||||||

| |||||||

| |||||||

| |||||||

| |||||||

| |||||||

| |||||||

| |||||||

| |||||||

| |||||||

| |||||||

| |||||||

| |||||||

| |||||||

| |||||||

| |||||||

| |||||||

| |||||||

| |||||||

| |||||||

| |||||||

| |||||||

| |||||||

| |||||||

| |||||||

|

Appendix B

This is the validated questionnaire based on the trifactorial model with 14 items.

MOTIVACIONES DOCENTES (CUMODE, 14 ítems).

Para poder recoger estos datos es necesario contar con su consentimiento informado, el cual se dará por aceptado con la mera cumplimentación y posterior envío de este cuestionario. Para garantizar la completa confidencialidad de los datos obtenidos se ha tenido en cuenta la Ley Orgánica 3/2018, de 5 de diciembre, de Protección de Datos Personales y garantía de los derechos digitales.

Si tiene cualquier pregunta sobre la encuesta, envíenos un correo electrónico a: emocreaull2@gmail.com

Habiendo sido informado/a de los detalles de este cuestionario, ¿da su consentimiento voluntario para su cumplimiento?.

SÍ

NO

CUESTIONARIO DE MOTIVACIONES DOCENTES.

En el siguiente cuestionario, presentamos un conjunto de sentencias que contestan a la pregunta ¿POR QUÉ SOY DOCENTE? La tarea consiste en valorar, en una escala de 1 a 7 (siendo 1= NADA y 7= MUCHO), cuánto te identificas con cada una de esas razones. Se trata de que señales en qué medida estas expresiones se ajustan a las motivaciones actuales que mantienen tu decisión de ejercer como docente.

Todos los motivos que aparecen son igual de legítimos, así que te rogamos que respondas sin sentirse condicionado/a por el “qué dirán”, son tus motivaciones y no tienes por qué justificarlas.

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | |

| |||||||

| |||||||

| |||||||

| |||||||

| |||||||

| |||||||

| |||||||

| |||||||

| |||||||

| |||||||

| |||||||

| |||||||

| |||||||

|

15. En el momento actual de Valorando tu recorrido profesional ¿cambiarías la decisión de dedicarte a la profesión docente?

SÍ.

NO.

16. Si la respuesta a la pregunta 15 ha sido SÍ, comparte las razones.

17. Si la respuesta a la pregunta 15 ha sido NO, comparte ¿Cuál es la VERDADERA, ÍNTIMA Y PERSONAL motivación que mantiene tu decisión de seguir dedicándote a la docencia?

References

- UNESCO Institute of Statistic. The World Needs Almost 69 Million New Teachers to Reach the 2030 Education Goals. 2016. Available online: http://uis.unesco.org/en/files/fs39-world-needs-almost-69-million-new-teachers-reach-2030-education-goals-2016-en-pdf (accessed on 3 July 2023).

- European Commission/EACEA/Eurydice. Teachers in Europe: Careers, Development and Well-Being; Eurydice Report; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2021; Available online: https://eurydice.eacea.ec.europa.eu/sites/default/files/teachers_in_europe_2020_chapter_1.pdf (accessed on 3 July 2023).

- Franco-Lopez, J.A.; Lopez-Arellano, H.; Arango-Botero, D. The satisfaction of being a teacher: A correlational type study. Rev. Complut. Educ. 2020, 31, 55–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaack, D.; Le, V.; Stedron, J.M. When compliance is not enough: Early childhood teacher burnout and turnover intentions from a job demands and resources perspective. Early Educ. Dev. 2020, 31, 1011–1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz, J. Motivación Docente en Tiempos de Pandemia [online]. Licentiate Thesis in Psychopedagogy; Pontificia Universidad Católica Argentina: Buenos Aires, Argentina, 2021. Available online: https://repositorio.uca.edu.ar/handle/123456789/12938 (accessed on 16 December 2022).

- Bardach, L.; Klassen, R.M.; Perry, N.E. Psychological characteristics of teachers: Do they matter for teacher effectiveness, teacher well-being, retention, and interpersonal relationships? An integrative review. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 2022, 34, 259–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.; Vansteenkiste, M.; Beyers, W.; Boone, L.; Deci, E.L.; Van der Kaap-Deeder, J.; Verstuyf, J. Basic psychology needs satisfaction, frustration and strength across four cultures. Motiv. Emot. 2015, 39, 216–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.; Yin, H. Teacher motivation: Definition, research development and implications for teachers. Cogent Educ. 2016, 3, 1217819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fives, H.; Buehl, M. Spring cleaning for the “messy” construct of teachers’ beliefs: What are they? Which have been examined? What can they tell us? In APA Educational Psychology Handbook, Vol. 2. Individual Differences and Cultural and Contextual Factors; Harris, K.R., Graham, S., Urdan, T., Graham, S., Royer, J.M., Zeidner, M., Eds.; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2012; pp. 471–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dornyei, Z.; Ushioda, E. Motivation Teaching and Research, 3rd ed.; Pearson: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Alkin, M. Enciclopedia de Investigación Educativa, 6th ed.; Macmillan: New York, NY, USA; Maxwell Macmillan Canadá: Toronto, ON, Canada; Maxwell Macmillan International: New York, NY, USA, 1992. Available online: https://lccn.loc.gov/91038682 (accessed on 23 February 2023).

- Brophy, J. Research on motivation in education: Past, present and future. Adv. Motiv. Achiev. Role Context 1999, 11, 1–44. [Google Scholar]

- Pintrich, P.; Schunk, D. Motivation in Education: Theory, Research, and Applications; Merrill: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1996. Available online: https://lccn.loc.gov/95017192 (accessed on 14 November 2022).

- Weiner, B. History of motivational research in education. J. Educ. Psychol. 1990, 82, 616–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naranjo Pereira, M.L. Motivation: Theoretical perspectives and some considerations of its importance in educational settings. Educ. J. 2009, 33, 153–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, S.; Weiner, B. Theories and Principles of Motivation. In Handbook of Educational Psychology; Berliner, D.C., Calfee, R.C., Eds.; Macmillan: New York, NY, USA, 1996; pp. 63–84. [Google Scholar]

- González Torres, M. Keys to Promote Teacher Motivation in the Face of Current Educational Challenges. Studies on Education. 2003. Available online: https://redined.educacion.gob.es/xmlui/bitstream/handle/11162/45610/01520103000055.pdf?sequence=1 (accessed on 13 November 2022).

- Valdés, C. Motivación. Consultado el 25 de Febrero de 2023. 2005. Available online: http://www.gestiopolis.com/canales5/rrhh/lamotici.html (accessed on 25 February 2023).

- Maslow, A.H. Una Teoría Dinámica de la Motivación Humana. In Comprender la Motivación Humana; Stacey, C.L., De Martino, M., Eds.; Editorial Howard Allen, Random House Group: New York, NY, USA, 1958; pp. 26–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brockett, C. Toward a clarification of the need hierarchy theory: Some extensions of Maslow’s conceptualization. Interpers. Dev. 1975, 6, 77–90. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell, T.R.; Daniels, D. Observations and commentary on recent research in work motivation. Motiv. Work. Behav. 2003, 7, 225–254. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan, R.M.; Deci, E.L. La Teoría de la autodeterminación y la facilitación de la motivación intrínseca, el desarrollo social y el bienestar. Psicólogo Estadounidense 2000, 55, 68–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deci, E.L.; Ryan, R.M. Self-determination Theory: When Mind Mediates Behavior. J. Mind Behav. 1980, 1, 33–43. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/43852807 (accessed on 12 November 2022).

- Deci, E.L.; Ryan, R.M. The empirical exploration of intrinsic motivational Processes11Preparation of this chapter was facilitated by research grant MH 28600 from the national institute of mental health to the first author. Adv. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 1980, 13, 39–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gagné, M.; Deci, E.L. Self-determination theory and work motivation. J. Organ. Behav. 2005, 26, 331–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz Quiles, M.; Moreno-Murcia, J.; Vera Lacárcel, J.A. From autonomy support and self-determined motivation to teacher satisfaction. Eur. J. Educ. Psychol. 2015, 8, 68–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epstein, R.M.; Hundert, E.M. Definition and assessment of professional competence. JAMA 2002, 287, 226–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunter, M.; Frenzel, A.; Nagy, G.; Baumert, J.; Pekrun, R. Teacher enthusiasm: Dimensionality and context specificity. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 2011, 36, 289–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fives, H.; Buehl, M.M. Teacher-motivation. In Handbook of Motivation at School; Wentzel, K.R., Et Miele, D.B., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2016; pp. 340–360. [Google Scholar]

- Richardson, P.W.; Karabenick, S.A.; Watt, H.M. Teacher motivation. In Theory and Practice; Routledge: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2014; pp. 3–36, 167–174. [Google Scholar]

- Kyriacou, C.; Kunc, R. Beginning teachers’ expectations of teaching. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2007, 23, 1246–1257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deci, E.; Ryan, R. The ‘what’ and the ‘why’ of goal seeking: Human needs and the self-determination theory of behaviour. Psychol. Res. 2000, 11, 227–268. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/1449618 (accessed on 12 November 2022).

- Brunetti, G.J. Why Do They Teach? A Study of Job Satisfaction among Long-Term High School Teachers. Teach. Educ. Q. 2001, 28, 49–74. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/23478304 (accessed on 12 November 2022).

- Dinham, S.; Scott, C. Teacher Satisfaction, Motivation and Health: Phase One of the Teacher 2000 Project. In Paper Presented to the Annual Meeting of the American Educational Research Association; American Educational Research Association: New York, NY, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinham, S.; Scott, C. Moving into the third, outer domain of teacher satisfaction. J. Educ. Adm. 2000, 38, 379–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, C.; Stone, B.; Dinham, S. I love teaching but … international patterns of teacher discontent. Educ. Policy Anal. Arch. 2001, 9, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, B.H. Why do they want to become teachers? A study on prospective teachers’ motivation to teach in Hong Kong. Asia-Pac. Educ. Res. 2012, 21, 307–314. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Lam-Bick-Har/publication/289616282_Why_Do_They_Want_to_Become_Teachers_A_Study_on_Prospective_Teachers’_Motivation_to_Teach_in_Hong_Kong/links/573e76b508ae9ace84113627/Why-Do-They-Want-to-Become-Teachers-A-Study-on-Prospective-Teachers-Motivation-to-Teach-in-Hong-Kong.pdf (accessed on 25 February 2023).

- Noddings, N. The Challenge to Care in Schools; Teachers College: New York, NY, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Moè, A.; Consiglio, P.; Katz, I. Exploring the circumplex model of motivating and demotivating teaching styles: The role of teacher need satisfaction and need frustration. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2022, 118, 103823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watt, H.M.G.; Richardson, P.W. Motivational factors influencing teaching as a career choice: Development and validation of the FIT-choice scale. J. Exp. Educ. 2007, 75, 167–202. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/20157455 (accessed on 12 November 2022). [CrossRef]

- Watt, H.M.G.; Richardson, P.W. Motivations, perceptions, and aspirations concerning teaching as a career for different types of beginning teachers. Learn. Instr. 2008, 18, 408–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watt, H.M.G.; Richardson, P.W.; Klusmann, U.; Kunter, M.; Beyer, B.; Trautwein, U.; Baumert, J. Motivations for choosing teaching as a career: An international comparison using the FIT-choice scale. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2012, 28, 791–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aydogan, I.; Atilla Dogan, A.; Bayram, N. Burnout among Turkish secondary school teachers working in Turkey and abroad: A comparative study. Electron. J. Educ. Psychol. Res. 2009, 7, 1249–1268. Available online: https://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=293121984014 (accessed on 12 November 2022).

- Ayuso Marente, J.A.; Guillén Gestoso, C.L. Burnout y mobbing en enseñanza secundaria. Rev. Complut. Educ. 2008, 9, 157–173. Available online: https://redined.educacion.gob.es/xmlui/bitstream/handle/11162/124789/16442-16518-1-PB.PDF?sequence=1 (accessed on 14 November 2022).

- Veldman, I.; van Tartwijk, J.; Brekelmans, M.; Wubbels, T. Job satisfaction and teacher–student relationships across the teaching career: Four case studies. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2013, 32, 55–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, N.K.; Sass, D.A.; Schmitt, T.A. Teacher efficacy in student engagement, instructional management, student stressors, and burnout: A theoretical model using in-class variables to predict teachers’ intent-to-leave. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2012, 28, 546–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caichug Rivera, D.M.; Ruíz, D.L.; Laurella, S.L. Work stress, COVID-19 and other factors that determine teacher well-being. I2D Sci. J. 2021, 1, 43–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazarides, R.; Schiefele, U. Teacher Motivation: Implications for Instruction and Learning. Introduction to the special number. Learn. Instr. 2021, 76, 101543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mérida-López, S.; Quintana-Orts, C.; Hintsa, T.; Extremera, N. Teachers’ emotional intelligence and social support: Exploring how personal and social resources are associated with job satisfaction and teacher dropout intentions. Psycho Didact. Mag. 2022, 27, 168–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holzberger, D.; Philipp, A.; Kunter, M. Predicting teachers’ instructional behaviors: The interplay between self-efficacy and intrinsic needs. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 2014, 39, 100–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunter, M.; Holzberger, D. Loving teaching. In Teacher Motivation: Theory and Practice; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2014; pp. 83–95. [Google Scholar]

- Watt, H.M.; Richardson, P.W.; Smith, K. Global Perspectives on Teacher Motivation. 2017. Available online: https://books.google.es/books?hl=es&lr=&id=8nA2DwAAQBAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PT23&dq=Watt+et+al.,+2017+teachers&ots=A7-e2W7hMO&sig=Mo92c8PgcgAvIqK2owXvqTb3QWA&redir_esc=y#v=onepage&q=Watt%20et%20al.%2C%202017%20teachers&f=false (accessed on 14 November 2022).

- Hoy, A.W. What motivates teachers? Important work on a complex question. Learn. Instr. 2008, 18, 492–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klassen, R.M.; Tze, V. Teachers’ self-efficacy, personality, and teaching effectiveness: A meta-analysis. Educ. Res. Rev. 2014, 12, 59–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woolfolk, A.E.; Hoy, A.W.; Hughes, M.; Walkup, V. Psychology in Education; Pearson Education: London, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Zee, M.; Koomen, H. Teacher self-efficacy and its effects on classroom processes, student academic adjustment, and teacher well-being: A synthesis of 40 years of research. Rev. Educ. Res. 2016, 86, 981–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lauermann, F.; Karabenick, S.A. Taking teacher responsibility into account (ability): Explicating its multiple components and theoretical status. Educ. Psychol. 2011, 46, 122–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lauermann, F.; Karabenick, S.A. The meaning and measure of teachers’ sense of responsibility for educational outcomes. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2013, 30, 13–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lauermann, F. Teacher responsibility from the teacher’s perspective. Int. J. Educ. Res. 2014, 65, 75–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matteucci, M.C.; Guglielmi, D.; Lauermann, F. Teachers’ sense of responsibility for educational outcomes and its associations with instructional approaches and teachers’ professional well-being. Soc. Psychol. Educ. 2017, 20, 275–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balyer, A.; Özcan, K. Choosing teaching profession as a career: Students’ reasons. Int. Educ. Stud. 2014, 7, 104–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyriacou, C.; Coulthard, M. Undergraduates’ views of teaching as a career choice. J. Educ. Teach. 2000, 26, 117–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomson, M.M.; Turner, J.E.; Nietfeld, J.L. A typological approach to investigate the teaching career decision: Motivations and beliefs about teaching of prospective teacher candidates. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2012, 28, 324–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yüce, K.; Şahin, E.Y.; Koçer, Ö.; Kana, F. Motivations for choosing teaching as a career: A perspective of prospective teachers in a Turkish context. Asia Pac. Educ. Rev. 2013, 14, 295–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azman, N. Choosing teaching as a career: Perspectives of male and female malaysian student teachers in training. Eur. J. Teach. Educ. 2013, 36, 113–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watt, H.M.G.; Richardson, P.W. An introduction to teaching motivations in different countries: Comparisons using the FIT-choice scale. Asia-Pac. J. Teach. Educ. 2012, 40, 185–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tapia, J.A. Motivaciones, expectativas y valores-intereses relacionados con el aprendizaje: El cuestionario MEVA. Psicothema 2005, 17, 404–411. Available online: https://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=72717307 (accessed on 25 February 2023).

- Pintrich, P.R.; Schunk, D.H. Motivation in Education: Theory, Research, and Applications, 2nd ed.; Prentice Hall. Trad. Castellano: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Tschannen-Moran, M.; Woolfolk Hoy, A. (Eds.) The influence of resources and support on teachers’ efficacy beliefs. Presented at the Annual Meeting of the American Educational Research Association, New Orleans, LA, USA, 1–5 April 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Tapia, J.A. Evaluation of motivation in educational environments. In Orientative and Tutorial Manual; Álvarez, M., Bisquerra, R., Eds.; Kluwer (Electronic Book): Barcelona, Spain, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Richardson, P.W.; Watt, H.M.G. Who chooses teaching and why? Profiling characteristics and motivations across three Australian universities. Asia-Pac. J. Teach. Educ. 2006, 34, 27–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guay, F.; Vallerand, R.; Blanchard, C. On the assessment of intrinsic and extrinsic motivation situation: The Situational Motivation Scale (SIMS). Motiv. Emot. 2000, 24, 175–213. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/343730374_Escala_de_motivacion_situacional_academica_para_estudiantes_universitarios_desarrollo_y_analisis_psicometricos (accessed on 21 April 2023). [CrossRef]

- Carrillo, M.; Padilla, J.; Rosero, T.; Villagómez, M.S. Motivation and learning. Otherness Educ. Mag. 2009, 4, 20–32. Available online: https://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=467746249004 (accessed on 14 November 2022).

- Martín-Albo, J.; Núñez, J.; Navarro, J. Validación de la Versión Española de la Escala de Motivación Situacional (EMSI) en el Contexto Educativo. Rev. Española De Psicol. 2009, 12, 799–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruno, F.; Fernández, M.; Stover, J. Interdisciplinary. J. Psychol. Relat. Sci. 2020, 37. Available online: http://www.ciipme-conicet.gov.ar/ojs/index.php?journal=interdisciplinaria&page=issue&op=view&path%5B%5D=11 (accessed on 24 April 2023).

- Gamboa, V.; Valadas, S.; Paixão, O. Validation of a portuguese version of the situational motivation scale (SIMS) in academic contexts. Av. En Psicol. Latinoam. 2017, 35, 547–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernet, C.; Senécal, C.; Guay, F.; Marsh, H.; Dowson, M. La Escala de Motivación de Tareas Laborales para Docentes (WTMST). Rev. Evaluación Carreras 2008, 16, 256–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valenzuela, J.; Muñoz, C.; Precht Gandarillas, A.; Silva Peña, I.; Oliva, M.A.; Marfull-Jensen, M. Inventario Motivacional Para la Formación de PROFESORES. 2016. Available online: https://tinyurl.com/IMFP2016 (accessed on 28 July 2023). [CrossRef]

- Ho, A.D.; Yu, C.C. Descriptive statistics for modern test score distributions: Skewness, kurtosis, discreteness and cei ling effects. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 2015, 75, 365–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Méndez Martínez, C.; Rondón Sepúlveda, M.A. Introduction to exploratory factor analysis. Colomb. J. Psychiatry. 2012, 41, pp. 197–207. Available online: http://www.scielo.org.co/scielo.php?pid=S0034-74502012000100014&script=sci_abstract&tlng=es (accessed on 3 May 2023).

- Batista-Foguet, J.M.; Coenders, G.; Alonso, J. Confirmatory factor analysis. Its role on the validation of health related questionnaires. Med. Clin. 2004, 122, 21–27. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, L.; Bentler, P. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Equ. Model. Multidiscip. J. 1999, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bollen, K.A. Structural Equations with Latent Variables; John Wiley y Sons: New York, NY, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Ayán, M.N.R.; Díaz, M.Á.R. The reduction of skewness and kurtosis of observed variables by data transformation: Effect on factor structure. Psicológica 2008, 29, 205–227. [Google Scholar]

- Shanti, R. Multivariate Data Análisis: Using SPSS and AMOS; MJP Publishers: Tamil Nadu, India, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Marsh, H.W.; Hocevar, D. Application of confirmatory factor analysis to the study of self-concept: First-and higher order factor models and their invariance across groups. Psychol. Bull. 1985, 97, 562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waldinger, R.J.; Schulz, M. The Good Life: Lessons from the World’s Longest Scientific Study of Happiness; Simon & Schuster Editors: New York, NY, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).