1. Introduction

In recent years, the understanding of heritage education has evolved, receiving more attention since it was considered by international institutions such as the Council of Europe and UNESCO [

1]. The UNESCO Convention Concerning the Protection of Cultural and Natural Heritage marked a starting point in the development of heritage education by underlining the importance of educational programs in formal and non-formal education for safeguarding, promoting and increasing knowledge of heritage [

2]. According to [

3], heritage education could be considered the educational mediation tool in heritage valorization, conservation and, afterwards, transmission processes. In this way, heritage education plays an important role as it becomes a link between past and present, which generates a feeling of identity and social and cultural belonging [

4].

Since schools are the main social institution for global citizens’ training, it is important to implement school teaching proposals related to heritage education [

5,

6]. Likewise, in recent years, there has been a growing tendency to incorporate educational programs into a heritage context, such as museum programs, archaeological sites, popular festivals and interpretation centres of natural parks [

7,

8,

9]. Recently, cultural heritage didactics have also proven to be a helpful educative resource to use with migrant students’ integration process; for instance, learning from shared heritage boosted students’ inclusion and sense of identity, as well as highlighted how heritage allows educators to teach through democratic values in order to foster political and social participation amongst students [

10]. Although several studies highlight the importance of working on heritage education in classrooms, heritage is approached from a limited perspective and, in many cases, denies its holistic character [

10]. From this perspective, it is essential for teachers and managers involved in heritage education to perform training courses so that they can renew their disciplinary knowledge and update their didactic skills [

11].

In this regard, several studies in heritage education focus on analyzing the teachers’ conceptions in the fields of experimental sciences or social sciences. However, there are fewer studies that focus on studying heritage education from an integrative perspective [

12,

13]. These studies identify the conceptions of heritage and its teaching in Spanish primary and secondary teachers to determine the level of development and determine potential obstacles in their professional knowledge. Results from these studies show, on the one hand, that Geography and History teachers present more developed conceptions about heritage, as they have a more holistic view since this content knowledge is developed during their previous training. On the other hand, it is worth highlighting the minimal role that heritage plays in classrooms due to the lack of training in specific teaching methodologies and didactics related to heritage [

2].

Considering these references, our study seeks to go a step further by taking into account both the learning and didactic experience, as well as the conceptions and perceptions regarding the heritage of in-service teachers in Andorra, a country where such a study had never been carried out before. Specifically, the study aims (i) to identify the learning and professional experience of heritage and its didactics of in-service teachers; (ii) to analyze the perceptions of current didactic practices on heritage in primary and secondary schools; and (iii) to determine the conceptions and perceptions of in-service teachers regarding heritage, its value and its didactics.

3. Results

The results of the research are presented according to the objectives previously explained and also following the structure of the main instrument (

Table 1), which, as previously stated, was a semi-structured interview that had three out of four main dimensions focused on heritage and its didactics. Firstly, the educational background of the sample will be presented. In this sense, the results will continue disclosing the learning and professional experience with heritage and its didactics of in-service teachers, followed by presenting their perceptions of current didactic practices in relation to heritage. Lastly, the results shared will focalize on determining the conceptions and valorization importance of heritage and its didactics.

3.1. Educational Background of the Sample

The educational background of the sample has been analyzed using questions that arose from the first dimension of the interview related to the sociodemographic data (

Table 1). In this sense, the educational system to which they belonged was a relevant piece of information that was asked. In this sense, results show (

Table 2) that 54.8% of the teachers belonged to the Andorran system, and the other 45.2% were distributed amongst the Spanish (19%) and French systems (26.2%).

Furthermore, in-service teachers were also asked about their maximum level of study to date (

Table 3). As shown in

Table 3, most of the teachers (81%) had graduate-level education, and the rest also had a master’s degree (14%), and some of them even had a PhD (5%). Regarding these results, since 64% of the sample was represented by primary-level teachers—who can teach after an academic degree in education—it makes sense that the majority of the in-service teachers interviewed also had acquired that level of studies. On the other hand, results show that secondary education teachers (27% of the sample) are required with a previous specialized degree plus a master’s degree to enter the teaching force. As for the rest of the interviewed sample (9%), that small group was represented by professionals with a role in the board of direction of the school. Those are teachers who cannot teach at the moment due to the nature of their role and how it is shaped in Andorra, but who also had previous experience teaching.

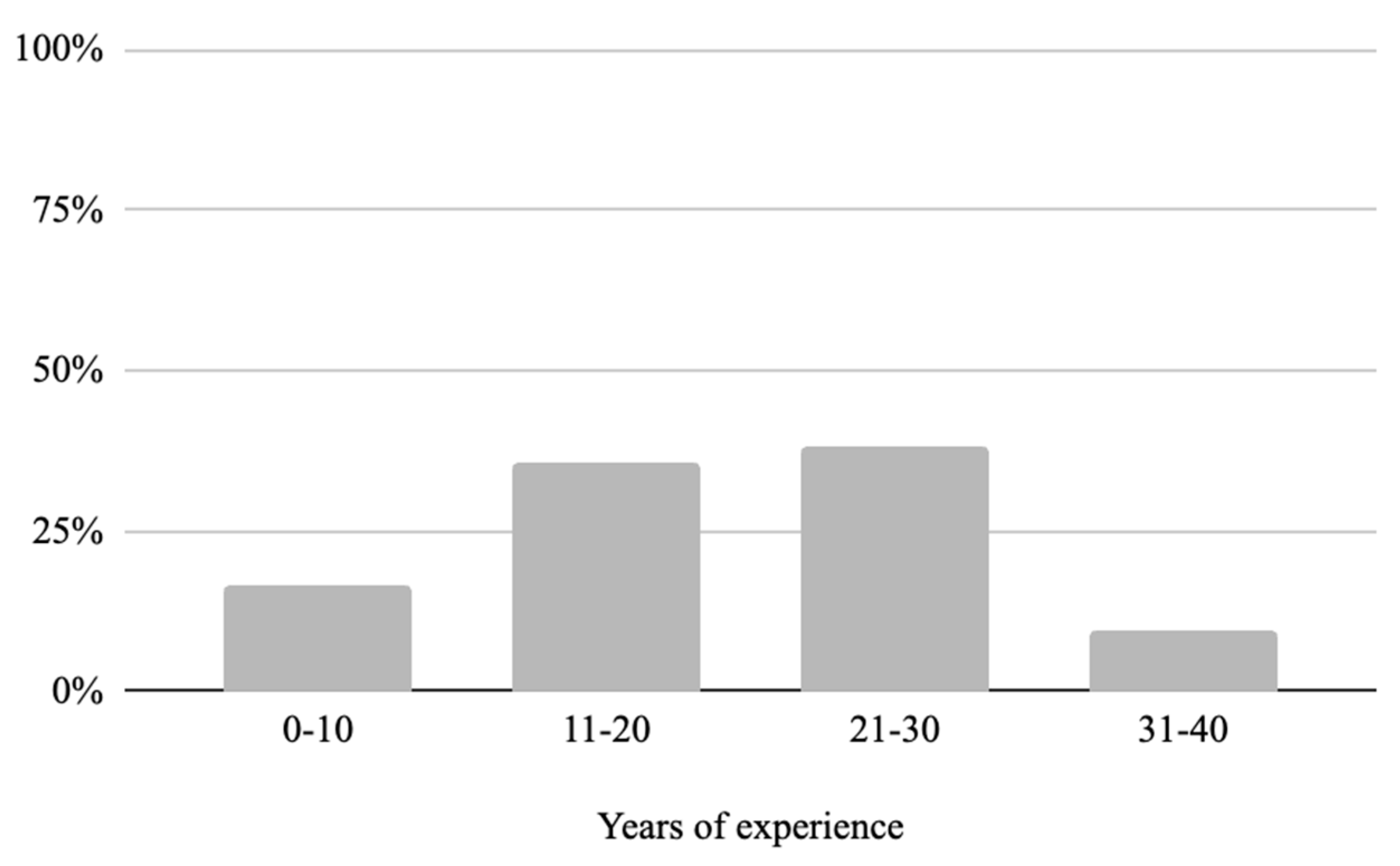

Moreover, the years of experience the interviewed teachers had in teaching in one school or in different schools were also gathered. As shown in

Figure 1, 9.52% of teachers had between 31 and 40 years of experience, 38.1% had a little less experience, between 21 and 30 years, followed by 35.71% of teachers with 11 to 20 years of experience and lastly, 16.67% of teachers with 10 or fewer years of experience. Therefore, since almost 85% have more than ten years of teaching experience, it could be considered that these teachers have a high degree of expertise in teaching.

3.2. Learning and Professional Experience with Heritage and Its Didactics

Learning and professional experience with heritage and its didactics from in-service teachers have been gathered from the second dimension of the interview (

Table 1), including items 2.1 and 2.2. In this sense, questions were focused on previous experiences based on heritage education.

3.2.1. Compulsory Education and Post-Obligatory Education Experience with Heritage

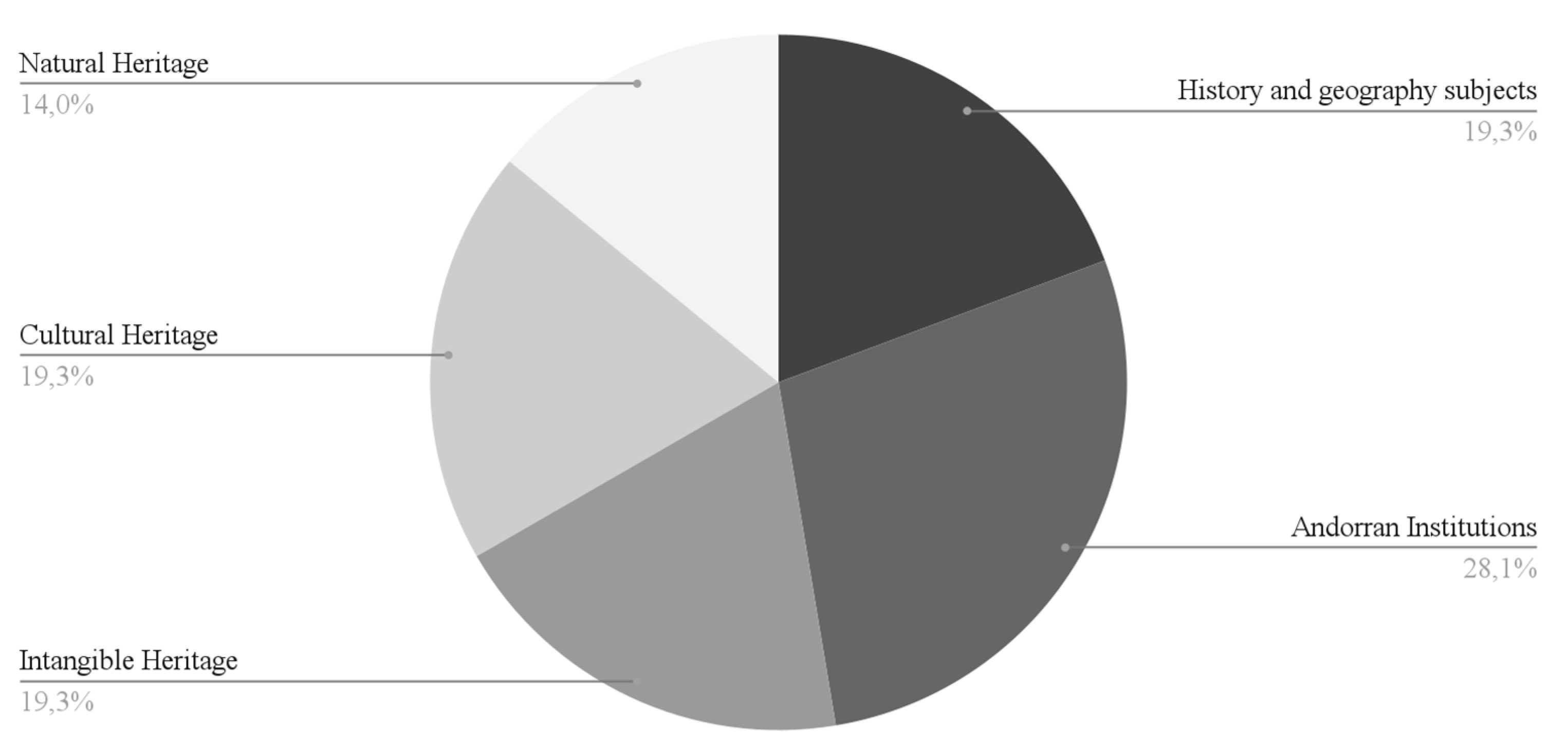

As shown in the following figure (

Figure 2), in-service teachers had different experiences during their studies in relation to the content on heritage learnt. Specifically, “History and geography subjects” and “Andorran Institutions” were studied during their obligatory education years.

The other categories focused on different typologies of heritage, which were experienced during both obligatory and post-obligatory studies, and gained more prevalence during the university years. As shown in

Figure 2, diverse typologies of heritage were studied and experienced by in-service teachers (previous to teaching) since percentages are well distributed.

In this sense, in-service teachers explained that they basically studied and experienced heritage through different lessons, such as in field tours during school hours (13%), as well as through heritage didactics (26.1%), studied during their post-obligatory education years. Moreover, in that same question, in-service teachers also responded that they studied heritage in general during their studies (21.7%), and some of them mentioned that, in particular, Intangible Heritage was the most studied (26%). Thus, their experiences in heritage seem to be quite distributed amongst different categories of heritage and diverse methodologies of study. Specifically,

Table 4 shows the topics and/or typologies of the lessons those teachers have taken while studying.

It is also important to highlight that 40.5% of the sample had previous training in different typologies of heritage. In-service teachers explained that the previous training in heritage was mainly received through specific titles, training sessions, courses and/or research on diverse typologies of heritage; those are displayed in

Table 5.

Regarding

Table 5, it is also relevant to comment on the fact that “Heritage didactics training sessions” and “Specific training on Cultural Touristic Guide” were the options most selected by the interviewees, with 21.43% in both cases. The first one specifically relates to training sessions received during their professional experience while in-service as either primary or secondary education teachers. The second one focuses on training experiences, before teaching, that usually younger people (appealed to by the tourist sector) choose to undergo in order to start having professional experience.

3.2.2. Professional Experience Regarding Heritage

In-service teachers answered two key questions during the interview regarding, firstly, the typologies of heritage most taught in class according to those in-service teachers. In

Table 6, the answers are displayed. Again, the most relevant ones, according to teachers, are Tangible Heritage (31.6%), followed by Natural Heritage (30.5%), Intangible Heritage (22.1%) and finally, Industrial Heritage (15.8%).

Secondly, very much related to the typologies of heritage taught in teaching are the methodologies used. In-service teachers answered about their experiences with how children and teens perceive and acquire heritage. In this sense, the methodologies most used during school hours were guided and non-guided tours (29%) because, according to the teachers, those are key activities for students to experience heritage in a significant way. Moreover, they also selected technological resources (13%) and traditional classes (11%) as the methodologies more used, followed by games (8%), Problem-Based Learning (8%) and challenges (7%) (

Table 7).

Furthermore, data regarding which tools were used in class, specifically in topics related to heritage education, were gathered (

Table 8). In-service teachers answered that the most used resources were real witnesses (28%), workshops based in school and in the museum (23.4%) and objects and/or tangible expositions (22.4%) since they are the ones which foster learning through experience the most. Other tools employed by the educators were audiovisual instruments (8.4%) and museum collections (2.8%).

In-service teachers were also asked about where resources used in class typically came from; most of them agreed on the idea that it was mixed (92%) since some came either from their own creations or from others’ elaborations. Only 5.1% of the teachers stated that all their resources were basically obtained from others, and 2.6% stated that all the resources used in heritage education were individually elaborated.

3.3. Perceptions of Current Didactic Practices on Heritage Education

How heritage education is perceived, as well as its design and needs, was specifically asked of the educators interviewed in order to collect information in this regard. In particular, the third dimension of the interview is relevant to this section, items 3.1 and 3.2.

3.3.1. Design of Heritage Education Proposals

With regard to educational practices, it is crucial to know which pedagogical elements are essential when designing a project or a specific task focused on heritage education. In this sense, the interviewed educators think that the most important actions are the ones displayed in

Table 9.

From those essential elements, the ones that received more support were that the activity proposed is motivational, appealing and based on experience (26%), followed by the importance of social participation (17.7%) and the contents of the project or task itself (15%). Afterwards, participation and/or experts’ validation (12.5%), as well as methodologies and objectives (both 11.5%), were also valued by in-service teachers. The element which received the least support was the one that included resources (5.2%). Educators do not think outstanding resources are necessary for the successful performance and outcome of a specific activity or project focused on heritage education.

3.3.2. Needs Regarding Heritage Education

With regard to the needs existing in their heritage education paradigm, in-service teachers were specifically asked if heritage should be fostered more throughout the curricula. In this sense, data show that most educators coincide with the fact that heritage is not present enough and should be encouraged more (63.4%). Nonetheless, educators also commented that, being objective, they see that it is difficult to include more content since the curricula are packed. As shown below in

Table 10, information was also gathered regarding which institutions in-service teachers think should foster heritage education projects and innovative actions. As can be seen, most believe it is the public administration (63.8%) that should boost it, followed by associations (14.9%), private institutions (13.8%) and, in the last place, schools (7.4%) (

Table 10).

3.4. Conceptions and Valorization of Heritage and Its Didactics

The last dimension of the interview, which approaches the last objective, addresses knowing the conceptions and valorization of heritage and its didactics for in-service teachers on a social and professional level (items 4.1–4.3). In this sense, questions towards educators were focused on identity conceptions and the contributions that arise from heritage, from a didactic and pedagogical level, as well as at a social level.

3.4.1. Conceptions of Heritage and Its Relationship with Identity

In-service teachers were also asked about which heritage elements are more relevant towards their own and collective identity in order to understand how they feel connected to heritage and also which elements are the most important to those who afterwards facilitate heritage education in schools. Again, the same pattern shown previously was repeated in the following one (

Table 11). The typology of heritage that in-service teachers felt most connected to was Tangible Heritage (37.7%), followed by Natural Heritage (36.2%), Intangible Heritage (24.6%) and Industrial Heritage (1.4%).

3.4.2. Valorization of Heritage Education Contribution to Students‘ Development

In-service teachers agree on the potential heritage education has to positively impact the didactics and learning experience. In this sense, they also agree on the fact that heritage can contribute to other significant pedagogical elements besides heritage knowledge. Moreover, in

Table 12, those elements that heritage education can help with regarding students’ development are shown, as well as the support received when in-service teachers were asked.

As displayed in

Table 12, for educators, it was clear that heritage education contributes to acquiring and developing values since 36.2% of the in-service teachers supported the idea. Furthermore, other essential aspects for students’ were also highlighted as significant, such as interest in the topic (21.3%) and identity development (18.1%). Those were followed by training and participation (6.4%) and inclusion and student participation (5.3%). The less supported categories were related to cultural awareness, country institutions’ knowledge and language knowledge (4.3%).

3.4.3. Valorization of Heritage Education Contribution to Society and Culture

In this section, in-service teachers were asked about the impact heritage education has on a social and cultural level. Again, educators interviewed agreed on the importance of how it can be a significant educational resource in order to boost social and cultural participation and participation amongst students.

In

Table 13, the elements that in-service teachers believe heritage education helps to develop are displayed. In this sense, it is important to highlight how identity development has been the element in-service teachers supported the most (30.6%). Followed by heritage valorization and conservation (20.4%), heritage transmission (17.3%) and citizen competencies (19.4%). Lastly, the elements less considered were social inclusion (7.1%) and historical knowledge of the country (5.1%).

4. Discussion

This pioneer study has allowed us to analyze the heritage conceptions, perceptions and learning and didactic experiences of heritage education from teachers of primary and secondary education of an entire country, Andorra. In this sense, the sample has been represented by teachers from the three different education systems coexisting in the country: Andorran, French and Spanish. Specifically, all the teachers in the Andorran system who teach a wide range of subjects (Catalan, Spanish, Social and Natural Sciences, History, Geography, Biology and/or Geology) are able to dynamize activities related to heritage education. Teachers from the French and the Spanish systems have a specific subject designated to Andorran heritage, which guarantees that this content is delivered, despite being foreign systems in Andorra. This subject is always taught by teachers that belong to the Ministry of Education of Andorra and who receive specific training from the same institution. As already said, previous studies have analyzed the students’ conceptions, perceptions and learning context of these three systems [

16]. This research has focused on the educators’ perspective in order to understand deeply how heritage education is fostered in Andorra.

Related to the first objective commented on the results, in-service teachers that were interviewed explained that they underwent different training courses and previous experiences related to heritage education but mostly focused on heritage didactics and Cultural Heritage. In this sense, different authors have discussed how heritage education and teachers’ conceptions have often been somewhat biased and do not take into account an integrative and holistic perspective of heritage [

12,

13].

In this regard, several studies in heritage education focus on analyzing the conceptions of teachers in the fields of experimental sciences or social sciences. However, there are fewer studies that focus on studying heritage education from an integrative perspective [

12,

13]. These studies identify the conceptions of heritage and its teaching in Spanish primary and secondary teachers to determine the level of development and determine potential obstacles in their professional knowledge. Results from these studies show, on the one hand, that Geography and History teachers present more developed conceptions about heritage, and they have a more holistic view since this content knowledge is worked on during their previous training. On the other hand, it is worth highlighting the minimal role that heritage plays in classrooms due to the lack of training in teaching methodologies and didactics related to heritage [

2].

Furthermore, in-service teachers stated that two typologies of heritage are taught more in class, Tangible and Natural Heritage, which agree with the students’ perceptions [

16]. In this sense, educators also commented on how students learn from those heritage typologies, and the most selected options were: guided tours, technological activities and traditional classes. On the one hand, the importance of guided tours aligns with recent studies that state that more educational programs are arising for diverse heritage initiatives [

7,

8,

9], which creates more opportunities for children and adolescents to have more significant experiences with regard to heritage education. Moreover, the use of technological resources to learn from heritage has also been indicated as a top resource for teachers. According to [

20], recently, there has been an important increase in the integration of digital technologies into heritage education which, obviously, is also correlated to the COVID-19 pandemic, where educators had to discover new assets to learn from virtual contexts. Finally, the last category of resources most chosen by teachers was related to traditional classes, which, according to [

11], is yet to happen due to the lack of training courses that have an integral view of heritage education in order to help teachers to innovate and improve their skills.

In connection with the second objective, perceptions of current didactic practices on heritage were asked. In-service teachers believe a good heritage educational project must be motivational, appealing, based on experience and have social participation; some elements are also highlighted by different studies about heritage education [

21]. Likewise, teachers think heritage should be more encouraged in schools and promoted by public administrations, which is in line with the recommendations of international cultural institutions [

22,

23,

24].

Moreover, and in relation to the third objective of this study, the perceptions of heritage amongst educators were studied. With this regard, in-service teachers mostly found that their identity was more consolidated over Tangible and Natural Heritage, which again relates to that [

10] affirmed in relation to in-service teachers’ training being biased to specific categories of heritage usually related to Social Sciences (Tangible) and Experimental Sciences (Natural). What is more, this last part of the study also focused on how the interviewees assessed whether heritage education could help with students’ development and social contributions. Related to the first one, in-service teachers perceive how heritage education plays a key role in different aspects of their development, i.e., identity, core values and interest in the subject, amongst others, which, according to [

16], is also valorized similarly by students when asked about heritage education. On the other hand, and related to social contributions, teachers agreed on how heritage education permit play a relevant role in identity development, heritage valorization and preservation, citizen competencies and heritage transmission, amongst others. This agrees with the awareness chain established by [

25,

26], which states that first, heritage is discovered, respected and valued before arriving at the awareness state, after which states of motivation for heritage, transmission, and preservation may arrive. Furthermore, other authors such as [

27] argue that, according to English and Spanish pre-service teachers, heritage also helps in critical and historical thinking, which allows students to develop skills related to social analysis. In this sense, and also according to [

10], heritage is a key element to boost the sense of identity, not only amongst local students, but Cultural heritage didactics also allow educators to foster migrant students’ inclusion process, as well as democratic values.

5. Conclusions

The present study has allowed us to find out the conceptions and perceptions about heritage education and the learning and professional experience related to the heritage of primary and secondary in-service teachers of a whole country. In this sense, their training has followed different paths but mostly focused on didactics and culture. They affirm that two of the typologies of heritage taught in class are Tangible and Natural, which are also considered the two elements that link clearly with the construction of identity and a sense of belonging.

In-service teachers are convinced that the heritage approach for students, especially through guided tours, technological activities and traditional classes, must be motivational and appealing and are useful for identity development, core values acquisition and heritage valorization and preservation.

In order to obtain better data, the sample could be extended, for example, considering other similar territories, like the Catalan or French regions of the Pyrenees, which have a similar cultural and educational context. This study is basically descriptive, so it could also be completed with a correlational analysis, such as segregating the results and taking into account the different educational systems of Andorra.