Abstract

Many nations that were once colonized continue to suffer from the economic effects of the colonial period. People in countries with high levels of poverty may benefit from taking massive open online courses (MOOCs) because these courses are broadcast for free or for considerably less than the cost of enrolling in traditional classes. However, these courses have been criticized for maintaining the inequalities created by colonialism. This study focuses on exploring whether MOOCs create inequalities toward people living in the Global South. It addresses how language, access to technology, and economic insecurity may make these courses less beneficial for people from low-income families than for those from more privileged backgrounds. It begins with a discussion of how colonialism impacted many nations in the world. Although many nations became free of colonial rule, colonialism led to economic instability, much of which persists to the present day. The findings indicate that MOOCs contribute to inequalities in several ways. One of these ways is by not providing enough support to help people from low-income families complete these courses. Another relates to the cost associated with having a strong internet connection and the other resources needed to submit work on time. The findings offer ideas on improving MOOCs. These ideas include offering MOOCs in the native languages of people living in the Global South and avoiding offering these courses according to the xMOOC model.

1. Introduction

Although the colonial era is over, many nations that were once colonized continue to suffer from the economic effects of this period. To deal with these effects, students from low-income families living in these nations may take massive open online courses (MOOCs). Such courses may benefit people in countries with high levels of poverty because they are broadcast for free or for considerably less than the cost of enrolling in traditional classes [1]. But critics argue that rather than benefiting people suffering from the effects of colonial rule, the offering of MOOCs maintains the inequalities created by colonialism [2].

Colonialism was practiced by ancient empires. Civilizations such as ancient Greece and ancient Rome conquered new areas over three thousand years ago. The colonies they created provided them with more power. This power was achieved by exploiting the people who were conquered [3].

Modern colonialism began in the 15th century. During this period, Portuguese explorers conquered a town outside of Europe. Other European nations, like England and France, began to conquer parts of the New World. When most countries in the New World gained independence, European nations focused on areas in Africa. Attracted to these areas for their natural resources, European nations established colonies they would control until a period of decolonization, which started around 1914 [3].

Although many nations became free of colonial rule, colonialism led to economic instability, much of which persists to the present day. In Africa, colonial rule was based on a system designed so that the colonizer could take the wealth away from the colony [4]. European rule also led to new borders based on colonial conquests. These borders led to instability because they caused divergent groups to live together under one colonial power. This unnatural way of dividing people harmed sub-Saharan Africa, leading to geopolitical crises that have lasted into the 21st century [5]. These crises have contributed to poverty, repression, and ethnic civil wars that have prevented nations in this region from thriving.

Africa is not the only area where people still feel the effects of colonialism. Across the Americas, colonialist practices have contributed to the poverty that members of Indigenous communities continue to experience [6]. In recent years, Indigenous people across North and South America protested against the social inequalities that still exist and the horrifying treatment perpetuated on their communities during colonial rule. In Chile, protesters tore down statues of Spanish conquistadores, and in Columbia, similar protests occurred. In Cali, Colombia, protesters toppled a statue of Sebastián de Belalcázar, a Spanish conquistador and the founder of the city [6].

Any aid that would alleviate the disparities in education and living standards caused by the effects of colonialism would be beneficial for people living in these areas [7]. This study focuses on whether the offering of MOOCs has provided underprivileged people in the Global South with more chances to reduce the effects of Western dominance. It also offers ideas on how MOOCs can be improved to alleviate the inequalities people in the Global South experience.

Characteristics, Origins, and Types of MOOCs

In addition to being free or nearly free, MOOCs attract more students than traditional classes. These courses are also open to anyone who wants to enroll. Many MOOCs can be observed by anyone, but some require a password. Although MOOCs are online courses, many have a face-to-face component. Shortly after these courses were created, they were offered for free, but some institutions have charged a fee for students who want to earn college credits [8].

There is evidence that because MOOCs can be offered in any area with an internet connection, these courses can benefit people in developing countries. In 2013, the New York Times published an article about a gifted teenager from Mongolia who earned a perfect score in a MOOC class offered by MIT. It was a sophomore-level class called Circuits and Electronics. This example showed how MOOCs can make high-quality education more accessible and affordable to more people. Performing well in this course proved that this student had the ability to succeed at MIT. This example illustrated how MOOCs may allow universities to find qualified students regardless of where they live. The student from Mongolia who earned a perfect score in Circuits and Electronics later attended MIT [1].

MOOCs were first offered in the 21st century. The term MOOC was used for the first time to refer to Connectivism and Connective Knowledge, a course offered in 2008 and designed by George Siemens and Stephen Downes [9]. MOOCs became more popular in 2011 when Stanford offered Introduction to Artificial Intelligence. Sebastien Thrun and Peter Norvig announced that this course would be offered on the internet for free, and soon after, over 160,000 enrollees were planning to participate. This was a significant project in the development of MOOCs because of the number of people who had enrolled in the course. Other universities that have been involved in MOOCs include MIT, Harvard, and the University of California, Berkeley [8].

MOOCs have often been classified according to the extent to which they focus on online collaboration. cMOOCs were developed to promote collaborative online learning, allowing participants to contribute and learn with minimum centralized control. These types of MOOCs are usually smaller, and participants blog frequently and create projects [8]. One criticism associated with cMOOCs is that they encourage participants to provide too much information, making them highly unstructured and chaotic [10].

In contrast, xMOOCS were created with an emphasis on content mastery through repetition and testing. Although classifying MOOCs using these two terms has been influential, this approach is simplistic because these courses can be developed in ways that do not fit well with either category [11].

2. Theoretical Framework

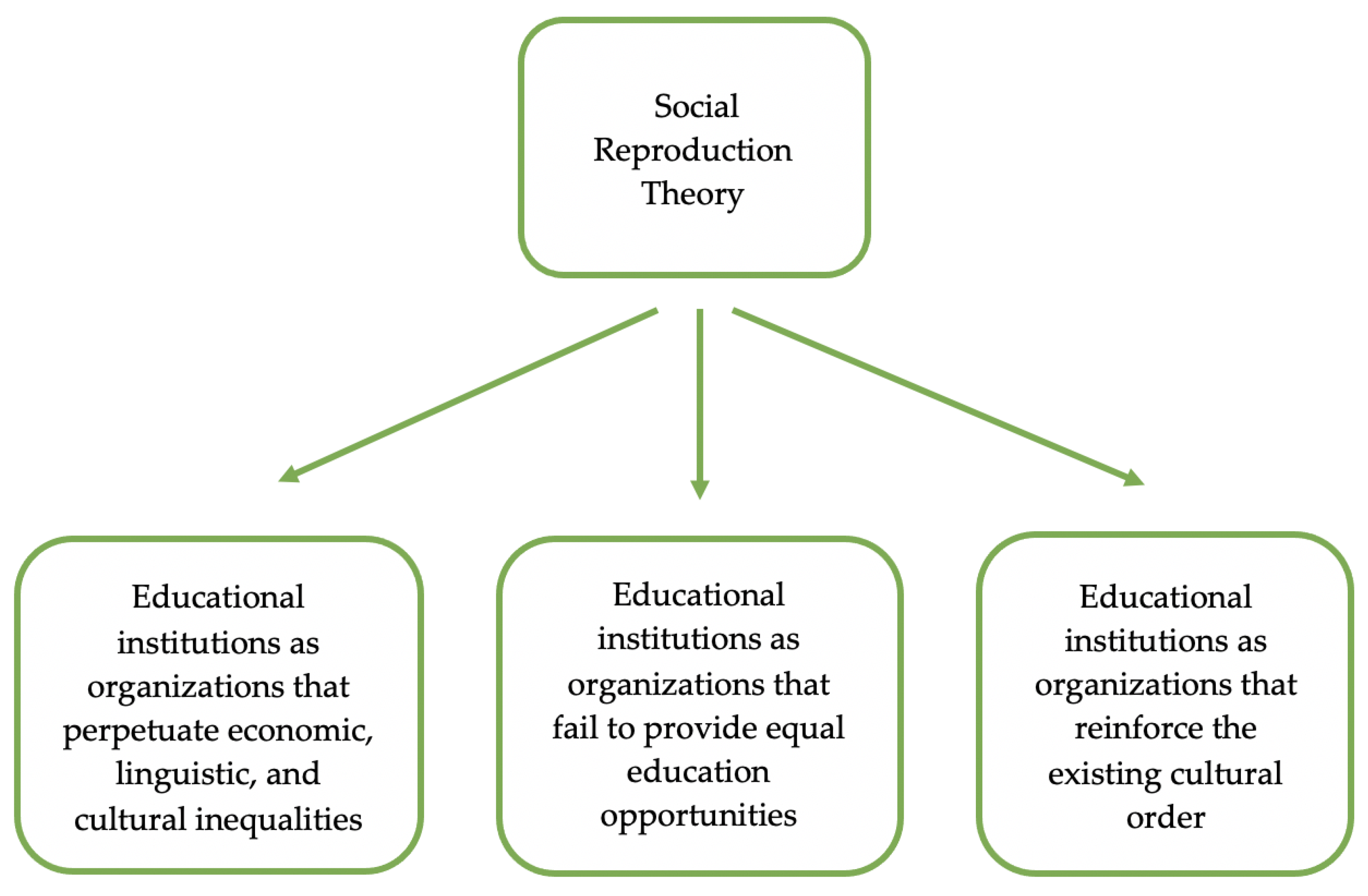

Two theories provided the lens for interpreting the data collected for this qualitative study: social reproduction theory and transformative learning theory. Social reproduction theory is based on the idea that educational institutions perpetuate inequalities rather than promote equal educational opportunities. The argument offered by reproductionist scholars is that these institutions reinforce the existing cultural order. Previous studies with conclusions supporting this theory focused on how educational institutions perpetuate economic, linguistic, and cultural inequalities [12]. Scholars have generally focused on how schools reproduce inequalities. However, it is believed that the higher education system perpetuates similar inequities [13].

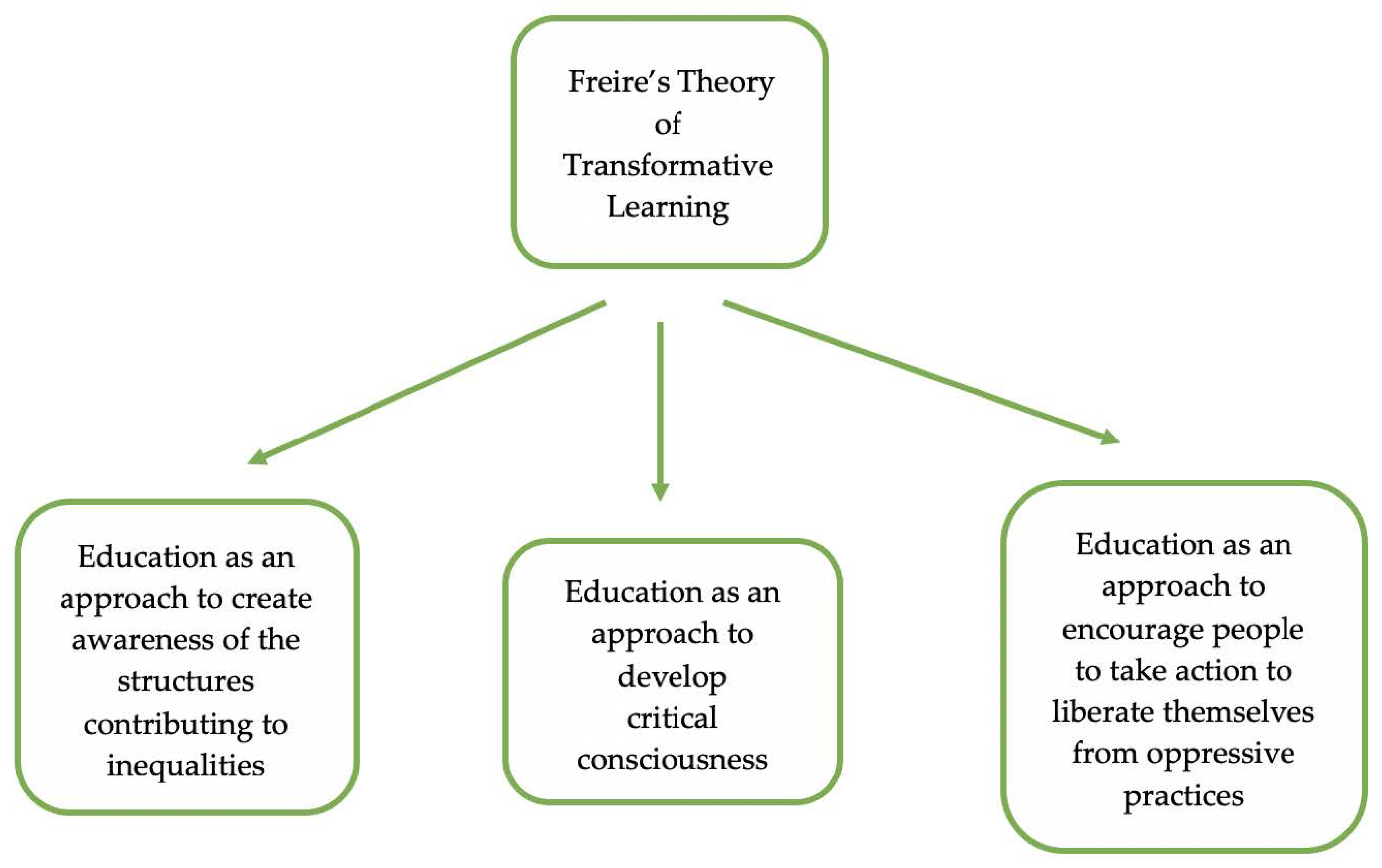

Paulo Freire’s theory of transformative learning focuses on providing learners with the ability to analyze situations so that they can take action to liberate themselves from oppressive practices. This form of learning emphasizes raising awareness of the structures that contribute to inequalities [14]. Freire rejected the passive exchange of knowledge that exposes learners to content disconnected from their experiences. Such an approach promotes a power imbalance between teachers and students. Instead, he advocated for an education that requires teachers to collaborate with learners, allowing them to gain the knowledge needed to free themselves from oppressive structures [15]. Freire’s ideas were originally implemented in Latin America and Africa. These ideas have spread to other parts of the world [14]. Figure 1 and Figure 2 show some of the concepts associated with social reproduction theory and Freire’s theory of transformative learning, respectively.

Figure 1.

Concepts associated with cultural reproduction theory. Source: Collins [12].

Figure 2.

Concepts associated with Freire’s theory of transformative learning. Source: Dirkx [14].

These two theories guided this research because they matched the research questions this study aimed to answer. As noted in Section 3, the research questions focus on whether MOOCs promote inequalities or create opportunities for reducing them.

3. Research Method and Research Questions

This study consists of an analysis of documents that were collected and analyzed using qualitative methods. Different types of data were collected from magazines, academic journals, books, newspapers, and websites. Using different types of data sources is a form of triangulation. Researchers use this form of triangulation based on the belief that a conclusion will be more credible if different types of data lead to the same conclusion [16].

3.1. Research Questions

This study focused on addressing three research questions:

- Do MOOCs alleviate or maintain the inequalities caused by colonialism?

- How do MOOCs alleviate or maintain these inequalities?

- How can MOOCs be improved to democratize education?

3.2. Selection and Retrieval of Documents

Three documents were initially selected in an effort to learn the most about the topic being researched. Selecting a sample strategically to answer the research questions being investigated is frequently referred to as purposeful sampling and is a common sampling strategy for qualitative studies [17]. Many types of purposeful sampling exist. In fact, Patton [17] described 40 purposeful sampling strategies. Of these 40, redundancy sampling is the one that best describes the sampling strategy used for this study. This approach allows researchers to add to a sample until they cease to learn anything new.

The three publications originally selected provided details on topics related to how MOOCs may alleviate or maintain inequalities. The first document was a paper entitled “Digital Neocolonialism and Massive Open Online Courses (MOOCs): Colonial Pasts and Neoliberal Futures.” The second was a book chapter entitled “Envisioning Post-Colonial MOOCs: Critiques and Ways Forward.” The third was a paper entitled “MOOCs as Neocolonialism: Who Controls Knowledge?” These documents introduced ideas that created a need to find more details to develop a comprehensive understanding about the topic.

The documents were collected electronically by using various databases. The databases available at the University of Southern Mississippi’s library were used to access some of the peer-reviewed journal articles. Other articles were retrieved through Google Scholar. Content from magazines, newspapers, and websites was collected by using search engines on the internet.

3.3. Inclusionary and Exclusionary Criteria

Two factors were used for considering whether a document would be included for analysis. First, each document needed to provide data relevant to the research questions. In other words, each document had to provide content about how MOOCs may alleviate or maintain inequalities. Second, the documents were checked for authenticity by ensuring they were produced by reputable authors, organizations, magazines, journals, and newspapers. Only those from authentic sources were considered for analysis.

Documents were excluded for two reasons. Some were excluded because they contained redundant content. Others were excluded because they contained content unrelated to the research questions.

3.4. Coding Process

The documents selected for this study were coded to develop themes. The coding recommendations for conducting a reflexive thematic analysis were followed. This approach to coding is based on an iterative process in which coding is not determined prior to examining the data. This method emphasizes interpreting the data to tell a story [18]. In reflexive thematic analysis, coding is a process that depends on how the researcher makes meaning from the data. The coding process is not considered right or wrong because it is based on the subjective nature of reflexive thematic analysis. The normal way of coding when using this method is for only one person to code [19].

Codes were created to develop insights relating to the research questions. As the data were read, text that addressed the research questions was tagged with a label. The next step involved collating similar codes with their corresponding data into clusters of meaning to describe a component of the dataset. For example, the different codes relating to the obstacles that may prevent students in the Global South from completing a MOOC were placed together. Some of these codes involved insufficient support and the expenses associated with successfully completing a course, such as being able to pay for a strong internet connection. This process led to the identification of the first theme, which focused on failing to meet students’ basic needs.

Although the coding and theme development of this study are consistent with the methods many qualitative researchers use, researchers who replicate this study using the same sources may identify different themes. This outcome is a possibility because in reflexive thematic analysis, different coders interpret text in different ways [19]. Quantitative researchers would consider the strong chance that a different researcher may identify different themes to be a limitation of this study. However, the importance of repeating a study to find out if it will yield the same results is usually unimportant for qualitative researchers. Such researchers often work under an interpretive paradigm and do not conduct research based on the idea that there is a single reality that can be understood through research that yields the same results. As Merriam and Tisdell [20] explained, if replication of a qualitative study does not produce the same findings, it does not mean a particular study should be discredited. More important for qualitative researchers is whether the data are consistent with the results.

4. Findings and Discussion

Four themes were identified after the coding process was completed. Two of these themes focus on how MOOCs exacerbate inequalities, and the other two highlight how MOOCs can be improved to reduce the inequalities identified. Although MOOCs have often been viewed as courses that would reduce socioeconomic inequalities, recent studies have revealed that they can exacerbate them in several ways. MOOCs can exacerbate inequalities toward underprivileged groups by failing to meet their basic needs and neglecting students’ languages and cultures. These courses can be improved by using methods to address these aspects of providing instruction and by creating more opportunities for people in the Global South to collaborate in developing MOOCs. Themes 1 and 2 focus on how MOOCs can exacerbate inequalities. Themes 3 and 4 address how MOOCs can be improved to reduce inequalities.

4.1. Theme 1: Failing to Meet Students’ Basic Needs

One of the ways MOOCs increase inequalities relates to the inferior learning opportunities they provide for socioeconomically disadvantaged people. Students from low-income families usually need more support to succeed academically than their more privileged peers [21]. To describe how MOOCs lack the support underprivileged students need, Bali and Sharma stated that these courses are disconnected with global students’ learning needs: “The massiveness of xMOOCs glosses over learner differences—in terms of access, preparation and support needs” [2] (p. 32). Since as many as tens of thousands of students typically enroll in a MOOC, instructors cannot provide the level of attention they normally do when teaching classes with fewer students [22].

One of the problems of using MOOCs to democratize education is that students from low-income families usually do not have the skills needed to excel in online courses. To succeed in these courses, they need to have strong time-management and study skills. Vulnerable students often take college courses to develop learning skills rather than use these skills to excel in online courses [23].

In addition to not helping many students learn at an optimal level, MOOCs often fail to address underprivileged students’ needs because completing a free MOOC may not allow these students to be hired for jobs that pay more. Although the MOOCs that lead to certification can create opportunities for students to earn more, these courses usually require students to pay a fee. Compared to how much regular courses cost, this fee is small. However, for many students in the Global South, this fee is unaffordable. Students from low-income families in these countries may also need to pay additional fees for internet access and supplementary course content [2]. Even if students can afford internet access, they may have weaker connections than wealthier students have, making their assignments more difficult to complete and submit on time [2].

Studies on learners who tend to complete MOOCs provide evidence that these courses frequently fail to meet the needs required for underprivileged students to benefit from this approach to education. Hansen and Reich [24] discussed that students who enroll in MOOCs frequently have a college degree. Their research showed that students from wealthier areas earned certificates at higher rates than other students. They also wrote that free “learning technologies can offer broad social benefits, but educators and policymakers should not assume that the underserved or disadvantaged will be the chief beneficiaries” [24] (p. 1247).

Other evidence showing that MOOCs usually benefit wealthier students rather than those from poorer households comes from data revealing the countries where students who enroll in these courses live. Data on where students taking MIT and Harvard MOOCs live revealed that most resided in highly developed countries. In 2017–2018, this data showed that over two-thirds of enrolled students came from these countries and that a considerably lower percentage of the students who took these courses came from countries rated lower in human development [25].

Educators should be skeptical of the idea of offering MOOCs to better meet the needs of learners in the Global South also because these courses are associated with more problems than traditional classes. One of these problems relates to the low percentage of students who complete MOOCs. For example, in 2014, Reich indicated that out of all students who register for a MOOC, the number of those who earn a certificate range from 2 to 10 percent [26].

Another concern involves the extent to which employers value the completion of MOOCs and MOOC certificates. Completing these courses may not increase students’ opportunities of being hired for a job because of the widespread cheating associated with participating in a MOOC. Such cheating may cause employers to doubt the competency of someone hoping to obtain a position after completing MOOCs. Some professors who taught MOOCs complained that students were collaborating on exams, emailing answers to peers, plagiarizing essays, and posting answers online [27].

Although some MOOC providers have responded to these concerns, many problems remain. For example, several companies started to proctor exams. However, this solution can cause problems for students from poor families in developing nations for several reasons. First, if students need to go to a testing center to take an exam, the expenses for such a trip may be unaffordable. Second, some companies proctor exams without requiring travel to a test center by having students place an identification card so that a proctor in another country can see it before students take the exam. However, many students in developing countries may not be able to afford an internet connection strong enough for their webcam to work well. This method is problematic also because a student can have friends sitting in a location where the proctor cannot see them so that they can provide answers to the student taking the test [27].

4.2. Theme 2: Ignoring Students’ Language and Culture

In addition to failing to meet many students’ basic needs, MOOCs are usually taught without respect for the cultures and languages of many groups living in the Global South. This neglect occurs because the majority of MOOCs are produced in English [10]. In 2014, it was estimated that 80 percent of MOOCs were taught in English [28]. Producing a MOOC for people living in the Global South in a language other than their own is detrimental for several reasons.

First, English is a barrier for many people living in the Global South. People in the Global South who speak English are more likely to come from wealthier households. The ability to communicate well in English, like stable access to the internet and the digital skills needed to complete MOOCs, is a marker of socioeconomic privilege. Offering MOOCs in English to people in the Global South may bring high-quality education to areas that previously did not have it. However, delivering it this way is likely to benefit people from privileged backgrounds rather than those from low-income households [29].

Second, disrespecting the language of Indigenous peoples occurred during the colonial era. Showing this disrespect again can easily be perceived as continuing an oppressive practice rather than democratizing education. One of the ways European powers dominated the areas they conquered was by forcing the people in these regions to speak a European language. Colonizers were able to use language to control other people because language is a tool that reflects values and beliefs, allowing a powerful group to dominate another group [30].

Language is often considered part of culture. In fact, Barone [31] stated that culture cannot exist without language. Language allows people to share knowledge, experiences, and perceptions. Language is so powerful that it may cause people who speak distinct languages to view the world differently. This is a possibility because each language is based on structures that shape a person’s perceptions [31].

Requiring a group to be educated without using their native language can also cause their language and culture to become extinct. The residential school system in Canada provides an example of how colonizers suppressed the languages of Indigenous peoples to the point of putting their cultures in danger of becoming extinct. This school system operated for many years and focused on cultural assimilation [30]. The schools punished Indigenous children severely for speaking their native language. Parents did not share their native language with children because they were afraid the children would experience the same consequences the parents endured. Consequently, much of their culture was not transmitted between people of different generations [30].

In addition to having a way to control the people they colonized, Europeans forced people to use a different language because they felt their language and culture were superior. When Europeans arrived in America, they viewed the original inhabitants of the land as culturally inferior. For instance, Christopher Columbus considered them as empty vessels that needed to learn the religion and language of European nations [32].

According to some scholars, Eurocentric ways of perceiving the language and culture of a given group of people still exist. Critics of MOOCs sometimes argue that because these courses are often taught in English, they are being used to dominate people in developing countries in a similar way to how these people were treated before their nations became independent. For example, Adam described the failure to provide MOOCs in the native languages of people living in the Global South as epistemic violence: “With this epistemic violence through language loss, the potential for a pluralistic global knowledge base vanishes to a handful of dominant languages and cultures” [10] (p. 373).

The process of neglecting native languages implies that the cultures of Indigenous populations are inferior. It also leads to the possibility that these languages will become extinct. Western languages have been reported to dominate certain parts of Africa to the point that parents no longer speak to their children in their native language, causing the children to lose the ability to speak this language [30].

Some languages did in fact become extinct after colonial rule in Africa. Many hunter-gatherer groups in South Africa spoke a variety of languages which became extinct after European colonization. During apartheid and colonialism, some Indigenous groups were not allowed to speak their native languages [33]. People even became ashamed of speaking their language because it was considered inferior. Because of the forcible assimilation of African people, an identity problem occurred, causing Indigenous people to prefer Western names instead of native ones [30].

MOOCs are criticized for being Eurocentric also because they are usually produced in non-Western nations. Some students are critical of MOOCs, suspecting that they could subvert their country’s culture. A study conducted with students in Turkey, for example, showed that some students distrusted MOOCs and associated them with imperialism. One student in the study discussed how Western nations did not respect non-European countries and referred to how these Western countries have mistreated non-Western nations [34].

4.3. Theme 3: Meeting Students’ Basic Needs

Since MOOCs are often criticized for failing to meet the basic needs of underprivileged students, one way to make them more democratic is to create them specifically to fulfill this goal. Fortunately, research has been conducted on which needs should be addressed to produce more favorable outcomes for these students. Lambert [35] conducted a systematic review of the components of MOOCs that were found to be associated with positive outcomes for underprivileged students. Some of Lambert’s findings are consistent with the obstacles previously discussed that prevent these students from completing a MOOC.

Since it is difficult to provide underprivileged students with the extra attention they need because of the large numbers of students who enroll, MOOCs that offer more support would likely benefit these pupils. Lambert [35] discussed that one of the ways this support could be offered includes offering MOOCs in different languages so that learners can use their mother tongue to better understand the content. As previously noted, English is a barrier for many people in the Global South.

There is evidence supporting that when people in less developed nations are offered MOOCs in their native language, more of them will participate. When a MOOC on the philosophy of science was offered in Portuguese, for example, the percentage of students enrolled in Brazil rose by 50 percent [29]. Thus, one of the methods major providers of MOOCs can use to make these courses more democratic is to offer incentives with partner institutions to create MOOCs using the local language [29]. For instance, a partner institution in Africa can offer a course in an African language.

Community partnerships can be formed to help students deal not only with the language barrier but also with other factors that may prevent underprivileged students from completing MOOCs. Lambert [35] discussed that community-based health and education organizations can provide important support. This support can consist of volunteers and tutors who facilitate online forums in culturally appropriate ways. Partnerships with equity group communities can provide information on developing more effective courses and strategies for alleviating Indigenous and gender inequalities [35].

Research on the importance of forming partnerships indicates that they can be useful for understanding the needs of underprivileged students. Lambert [35] stated that the most successful programs included various types of support and partnerships that provided insights on addressing the needs of the learners.

In addition to research that provides information on how MOOCs can be improved, some experts on this topic have provided their insights. For example, Rene Kizilcec, a co-author of a large study on MOOCs, advised instructors to focus on addressing the specific challenges that prevent certain groups of students from completing a MOOC [36]. Since some researchers, such as Ma and Lee [37], discussed that one of the challenges students in less developed countries face when taking an online course is lack of internet access, this obstacle needs to be addressed. Creators of MOOCs and policymakers need to find ways to ensure that students in less affluent countries have reliable internet access if they expect these courses to democratize education. Over 3 billion people, most living in developing countries, still have no internet at home [37].

In addition to unreliable internet access, people in the Global South frequently experience other obstacles involving technology, such as not having the computers, smartphones, or tablets needed to participate in MOOCs [37]. Organizations genuinely interested in creating MOOCs for helping people in the Global South need to address these obstacles. A considerable percentage of people in developing countries do not have a computer with broadband access. MOOCs are designed to work using these resources [38].

4.4. Theme 4: Respecting Language, Culture, and Knowledge Base

Offering MOOCs in students’ native languages may not only offer a way to meet the basic needs of many underprivileged people in developing countries but also show that MOOCs are not created to dominate these nations. Unfortunately, as discussed earlier, the majority of MOOCs are produced in English. Since language and culture are closely connected to each other, ensuring that MOOCs are offered in students’ native languages would likely reduce how often they are criticized for being Eurocentric.

However, many more improvements would need to be made to prevent skeptics from criticizing MOOCs for being Eurocentric. Simply offering a course in a student’s native language is insufficient because translating content into another language does not change which ideas dominate an academic institution. Since most MOOCs are developed in Western countries, translating them to the language spoken in a country in the Global South will not prevent European ideas from dominating people in less wealthy nations. Because MOOCs are often implemented to teach ideas that originate in the West, they are often criticized for continuing the domination of nations in the Global South. Altbach stated that they “threaten to exacerbate the worldwide influence of Western academe, bolstering its higher education hegemony” [39] (p. 5).

One of the ways to prevent this hegemony is for less wealthy nations to create their own MOOCs. Regrettably, few countries in the Global South participate in MOOC production [10]. One reason this happens involves how costly this process is, making it an impossible option for less affluent universities. In a paper published in 2014, Altbach wrote that “Udacity, an American MOOC provider, estimates that creating a single course costs $200,000, and is increasing to $400,000” [39] (p. 6).

Unfortunately, when universities in poor countries form partnerships with those in the Global North, they often do not contribute equally to the knowledge base and become consumers of Western knowledge. This outcome occurs because these universities frequently rely on funding from those in the Global North, making it less likely for them to make changes in the knowledge base [10]. Without democratic partnerships, skeptics will likely continue to criticize MOOCs. Western universities may create a MOOC about Africa without having a partnership with an African institution. Creating a MOOC this way increases the chances for the content to be stereotypical because of the lack of collaboration by African people in the production process [10]. Although MOOCs may create learning opportunities for people in the Global South, critics view them as a source that may ignore the importance of culture and local academic content [39].

To prevent this outcome, more focus needs to be provided to develop MOOCs through a bottom-up approach rather than one that is top-down. This means that if Western universities are genuinely interested in reducing the effects of colonialism toward the Global South, they need to respect the languages, cultures, and contexts of the people who live in less developed nations. To achieve this goal, countries in the Global South need to be provided with opportunities to collaborate in the creation of MOOC content. Creating MOOCs this way would allow education to be implemented using a pedagogy more similar to the kind Freire suggested than the approach that is more common today.

Another strategy for implementing online courses according to Freire’s approach is to minimize offering MOOCs according to the xMOOC model. xMOOCs tend to neglect the importance of student participation. Because of this one-way transmission of instruction, xMOOCs give the impression that people in the Global South do not possess valuable knowledge [10]. This type of instruction is the kind Freire advocated against because it silences the voices of marginalized people. Instead of the passive exchange of knowledge that xMOOCs promote, Freire advocated for the exchange of knowledge between teachers and students that is more likely to occur with a participatory approach to instruction.

5. Conclusions

Although colonialism created conditions that have caused people in the Global South to suffer, some researchers have hoped that MOOCs could alleviate the inequalities resulting from the colonial era. Unfortunately, regarding the first research question on whether MOOCs maintain inequalities, this study revealed that these courses do so in several ways. Concerning the second research question on how MOOCs maintain inequalities, this study showed that one of the ways MOOCs contribute to this effect is by failing to provide enough support to help people in the Global South complete these courses. Another relates to the costs associated with successfully completing a course, such as being able to pay for computers and adequate internet connections. This study also revealed that MOOCs often ignore the importance of the cultures and languages of people in the Global South and that these courses often benefit people from the Global North more than those in the Global South. People in wealthier nations are more likely to complete a MOOC because they have the resources needed to complete them and fewer obstacles that prevent them from taking such a course.

Regarding the third research question on how MOOCs could be improved to democratize education, this study revealed that this goal can be achieved in several ways. One way is to increase how often these courses are offered in the native languages of the people living in less wealthy nations. The knowledge bases of people in the Global South need to be respected as well. This goal can be achieved by creating more opportunities for people in less wealthy nations to be involved in the creation of MOOCs that better reflect local knowledge. To implement such an approach, offering MOOCs according to the xMOOC model should be avoided. This model gives the impression that people in the Global South do not possess valuable knowledge. In contrast, providing MOOCs that encourage student participation and minimize the passive exchange of knowledge will likely lead to more democratic outcomes. Such an approach is consistent with the kind of education Freire recommended for ending oppressive practices.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data used for this study were retrieved from the internet and from the databases available at the University of Southern Mississippi’s library.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Pappano, L. The Boy Genius of Ulan Bator. 2013. Available online: https://www.nytimes.com/2013/09/15/magazine/the-boy-genius-of-ulan-bator.html (accessed on 28 June 2023).

- Bali, M.A.; Sharma, S. Envisioning Post-Colonial MOOCs: Critiques and Ways Forward. In Massive Open Online Courses and Higher Education What Went Right, What Went Wrong and Where to Next? Bennett, R., Kent, M., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2017; pp. 26–44. [Google Scholar]

- Blakemore, E. What Is Colonialism? 2019. Available online: https://www.nationalgeographic.com/culture/article/colonialism?loggedin=true&rnd=1683747663825 (accessed on 29 June 2023).

- Berinzon, M.; Briggs, R. 60 Years Later, Are Colonial-Era Laws Holding Africa Back? 2017. Available online: https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/monkey-cage/wp/2017/01/20/60-years-later-are-colonial-era-laws-holding-africa-back/ (accessed on 10 May 2023).

- Geopolitical Futures. Colonial Powers in Sub-Saharan Africa. 2016. Available online: https://geopoliticalfutures.com/colonial-powers-in-sub-saharan-africa/ (accessed on 10 May 2023).

- Bartlett, J.; Alcoba, N.; Daniels, J.P.; Cecco, L. Indigenous Americans Demand a Reckoning with Brutal Colonial History. 2021. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2021/jul/27/indigenous-americans-protesting-brutal-colonial-history (accessed on 10 May 2023).

- Michalopoulos, S.; Papaioannou, E. European Colonialism in Africa Is Alive. 2021. Available online: https://www.project-syndicate.org/onpoint/europe-africa-colonial-era-lasting-effects-by-stelios-michalopoulos-and-elias-papaioannou-2021-07 (accessed on 30 June 2023).

- Fasimpaur, K. Massive and open. Learn. Lead. Technol. 2013, 40, 12–17. [Google Scholar]

- Crosslin, M. Exploring self-regulated learning choices in a customizable learning pathway MOOC. Australas. J. Educ. Technol. 2018, 34, 131–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adam, T. Digital neocolonialism and massive open online courses (MOOCs): Colonial pasts and neoliberal futures. Learn. Media Technol. 2019, 44, 365–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayne, S.; Ross, J. The Pedagogy of the Massive Open Online Course: The UK View. 2014. Available online: https://s3.eu-west-2.amazonaws.com/assets.creode.advancehe-document-manager/documents/hea/private/hea_edinburgh_mooc_web_240314_1_1568036979.pdf (accessed on 30 June 2023).

- Collins, J. Social reproduction in classrooms and schools. Annu. Rev. Anthropol. 2009, 38, 33–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, H. Neoliberalism’s influence on American universities: How the business model harms students and society. Policy Futures Educ. 2021, 20, 149–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dirkx, J.M. Transformative learning theory in the practice of adult education: An overview. PAACE J. Lifelong Learn. 1998, 7, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Rennick, J.B. Learning that makes a difference: Pedagogy and practice for learning abroad. Teach. Learn. Inq. 2015, 3, 71–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tracy, S.J. Qualitative quality: Eight ‘‘big-tent’’ criteria for excellent qualitative research. Qual. Inq. 2010, 16, 837–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patton, M.Q. Qualitative Research and Evaluation Methods; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V.; Hayfield, N.; Terry, G. Thematic Analysis. In Handbook of Research Methods in Health Social Sciences; Liamputtong, P., Ed.; Springer: Singapore, 2019; pp. 843–860. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Thematic Analysis: A Practical Guide; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Merriam, S.B.; Tisdell, E.J. Qualitative Research: A Guide to Design and Implementation, 4th ed.; Jossey Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- The White House. Increasing College Opportunity for Low-Income Students. 2014. Available online: https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/sites/default/files/docs/increasing_college_opportunity_for_low-income_students_report.pdf (accessed on 28 June 2023).

- Pappano, L. The Year of the MOOC. 2012. Available online: https://www.nytimes.com/2012/11/04/education/edlife/massive-open-online-courses-are-multiplying-at-a-rapid-pace.html (accessed on 10 May 2023).

- Jaggars, S.S. No, Online Classes Are Not Going to Help America’s Poor Kids Bridge the Achievement Gap. 2015. Available online: https://www.washingtonpost.com/posteverything/wp/2015/04/07/no-online-classes-are-not-going-to-help-americas-poor-kids-bridge-the-achievement-gap/ (accessed on 10 May 2023).

- Hansen, J.D.; Reich, J. Democratizing education? Examining access and usage patterns in massive open online courses. Science 2015, 350, 1245–1248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lederman, D. Why MOOCs Didn’t Work, in 3 Data Points. 2019. Available online: https://www.insidehighered.com/digital-learning/article/2019/01/16/study-offers-data-show-moocs-didnt-achieve-their-goals (accessed on 10 May 2023).

- Reich, J. MOOC Completion and Retention in the Context of Student Intent. 2014. Available online: https://er.educause.edu/articles/2014/12/mooc-completion-and-retention-in-the-context-of-student-intent (accessed on 10 May 2023).

- Webley, K. MOOC Brigade: Can Online Courses Keep Students from Cheating? 2012. Available online: https://nation.time.com/2012/11/19/mooc-brigade-can-online-courses-keep-students-from-cheating/ (accessed on 10 May 2023).

- International Consultants for Education and Fairs. MOOC Enrolment Surpassed 35 Million in 2015. 2016. Available online: https://monitor.icef.com/2016/01/mooc-enrolment-surpassed-35-million-in-2015/ (accessed on 29 June 2023).

- Agudo, R.R. The Language of MOOCs. 2019. Available online: https://www.insidehighered.com/digital-learning/views/2019/01/09/moocs-overwhelming-dependence-english-limits-their-impact-opinion (accessed on 10 May 2023).

- Sayedayn, S. Language & colonization: Statement of the problem. J. Sch. Soc. 2021, 7, 134–138. [Google Scholar]

- Barone, F. Language, Culture & Society. 2020. Available online: https://hraf.yale.edu/teach-ehraf/language-culture-society/ (accessed on 10 May 2023).

- Tisby, J. What Columbus Really Thought about Native Americans. 2018. Available online: https://thewitnessbcc.com/columbus-and-his-fellow-europeans-imported-their-ideas-of-racial-superiority-into-relationships-with-native-americans/ (accessed on 10 May 2023).

- Reuters. Last Known Speaker Fights to Preserve South African Indigenous Language. 2023. Available online: https://www.reuters.com/world/africa/last-known-speaker-fights-preserve-south-african-indigenous-language-2023-05-11/ (accessed on 29 June 2023).

- Kurt, S. The case of Turkish university students and MOOCs. Am. J. Distance Educ. 2019, 33, 120–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambert, S.R. Do MOOCs contribute to student equity and social inclusion? A systematic review 2014–18. Comput. Educ. 2020, 145, 103693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lefkowitz, M. Study: No Single Solution Helps All Students Complete MOOCs. 2020. Available online: https://news.cornell.edu/stories/2020/06/study-no-single-solution-helps-all-students-complete-moocs (accessed on 29 June 2023).

- Ma, L.; Lee, C.S. Leveraging MOOCs for Learners in Economically Disadvantaged Regions. 2023. Available online: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10639-022-11461-2 (accessed on 10 May 2023).

- UNESCO. Making Sense of MOOCs: A Guide for Policy-Makers in Developing Countries. 2016. Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000245122 (accessed on 10 May 2023).

- Altbach, P.G. MOOCs as neocolonialism: Who controls knowledge? Int. High. Educ. 2014, 75, 5–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).