Analysis of Students’ Emotional Patterns Based on an Educational Course on Emotions Management

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Theories of Emotions and Description of Emotional Intelligence

1.2. Education to Enhance Emotional Intelligence

1.3. Research Design, Motivations, and Hypotheses

- Determining feasible academic settings for educating students about emotional intelligence.

- Designing course content that would help students to improve their understanding of emotional intelligence.

- Conducting a knowledge-based and skill-training academic course on emotional intelligence.

- Encouraging students to implement knowledge and skills in managing their emotions through journal recording.

- Analyzing the journal records for emotional patterns and assessing emotional intelligence.

- Quantitative: There would be significant increases in the pre-course scores compared to the post-course scores on the emotional intelligence (EI) of the students, after the completion of a formal academic course on EI and implementation of the appropriate EI interventions throughout the semester, indicating the importance of designing an educational program to enhance EI.

- Qualitative: The analysis of students’ emotions journals would indicate the significant patterns of negative emotions experienced, specific triggers or reasons, the application of theories and concepts to understand emotions, and the strategies employed to deal with negative emotions, emphasizing the importance of an academic course on emotional management.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Procedure and Participants

2.2. Measures and Tools

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Statistics of Course Contents

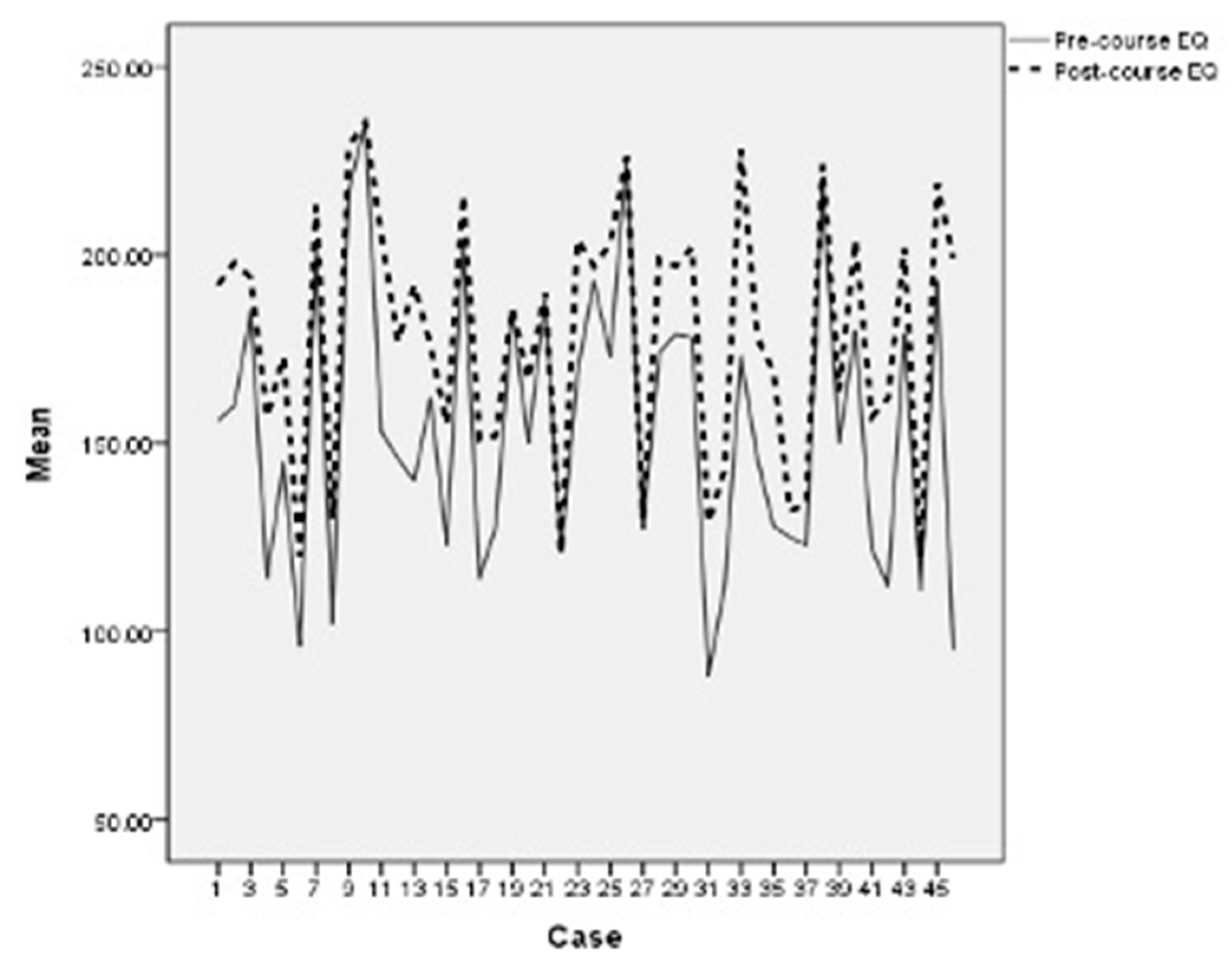

3.2. Differences in Pre-Course and Post-Course EI Scores

3.3. Analysis of Students’ Emotional Patterns

3.3.1. Anxiety

When working on a report, I don’t get enough sleep every day, and my energy is exhausted. I often feel anxious, worried that the report will not be completed, and blame myself for being angry with myself. I ask: Why can’t I do anything well? In the end, not only did I feel negative psychologically, but it also affected my health.

Ellis’ emotion theory can be used to explain. It seems that it is not the report itself that makes me feel anxious, but my belief is to be the most perfect, can’t be sloppy, and hope to be praised by others.

Everything does not need to be perfect to be applauded, as long as you do your best, you are worthy of yourself.

3.3.2. Irritability

I often feel irritable. I originally thought that “physiology” affects “emotion.” However, I found in the emotional log that the negative emotions at this time were actually induced by other events (for example: the report was not finished, the midterm exam was approaching), and the physiological part was just a multiplication effect.

And I found that I am an extremely “internal control” person, and I often have no confidence in myself. If I really don’t do things well, I will blame myself for a long time. Later, I tried to consciously tell myself to take it easy, and to write down the things to be done in detail. In this way, I can not only know that things are on track, but also be less likely to suffer from being irritable and screw things up.

I also gradually increased my self-efficacy, believing that I can get things done well.

3.3.3. Anger

The negative emotion (of anger) I often experience is that when I work in a restaurant, I often encounter some customers who make unreasonable demands. My mood, after a whole day of fatigue and high-intensity stress, made my negative emotions more negative, and my inner anger also increased with the degree of fatigue.

However, the unreasonable request of the guests is just a fuse, and how do I solve this negative emotion? Whenever I have this negative emotion, I always complain to my colleagues and chat with them to discuss it, and vent this emotion.

3.3.4. Sadness

Usually my negative emotions (of sadness) are related to relationships…I think I am a person who cares about my mirror self (image). This has been the case since I was a child. Although I have improved a lot along the way, I am worried that others will not accept me.

So after taking this class, I really agree that “emotions” can improve interpersonal relationships! I really wanted to participate (in Christmas dance party), but I dare not to, and I feel that it is a pity not to go… Yes, very contradictory. I just thought about why I dare not go? I think the reason is that I am afraid that I will be out of place, or not welcome there. In addition, I broke up with my boyfriend before, and I began to feel that no one would accept me, because I was a bad person, and no one would really like me. I felt that as long as I avoided the beginning of everything, I could not worry about any ending.

because I felt it was a pity not to go. After all, my good friends would also go, and I believe they would take care of me. After going there later, I had a lot of fun. I think it’s because I adjusted my mentality, I tried to tell myself not to be so exaggerated. If everyone really doesn’t like me, then why do I still have these friends by my side now! I mustered up my courage. Sure enough, the result was good.

3.3.5. Depression

Every night, my mood tends to be generally low. It may be because I am all by myself, so it is easy to think about many things, especially now that I don’t have any thoughts about the future, which makes me feel scared. At this time, negative emotions fill my heart.

At this time (night), I have a negative attitude towards other things I am doing at the moment, and even start to hate myself and the people and things around me. I usually fall asleep with this emotion, and I am prone to insomnia, and then my body is sore the next day.

In the future, I think there may be more unsatisfactory things happening. If I keep everything in mind for too long, negative emotions will entangle me, and I will be prone to depression. This will not only affect my health, but may also affect my interpersonal relationships. There is a bad cycle…..

After taking this emotional management course, I have a deeper understanding of my emotions, and then I will work hard to control my emotions. Whenever something unpleasant happens, I will take a deep breath first, think about why this happened, why I am unhappy, is it correct for me to be unhappy… etc., calm myself down, and don’t let emotions control (me)….

3.3.6. Fear

During one of the typhoon days, the school was closed, and this day happened to be my part-time job, so I went to 711 with a feeling of fear and reluctance. I think that going to work on a typhoon is a very dangerous thing.

Although I really didn’t want to go to work, I boarded the bus and I started to apply Lazarus’ cognitive evaluation theory. I thought it was negative in the primary evaluation, and then entered the secondary evaluation. I thought in my heart that there would be no guests coming during the typhoon, so I chose to accept it. After a series of (evaluative) thoughts, my mood changed.

3.3.7. Guilt

When I got to the part-time job, I could only apologize to other colleagues, because my “intentional” lateness caused them a lot of burden. Even though everyone told me not to take it seriously, I still felt an inexplicable guilt in my heart, partly because of being hurt (by my boss).

I found that at the moment when the incident happened, I only thought of the bad. I felt that it was a very bad thing to be rushed even though it was not yet time for work. Then I blamed myself for why I agreed to such an unreasonable scheduling of work. In addition to being guilty, I could only blame myself constantly, resulting in a very uncomfortable state of mind and body.

I think it was a matter of lack of self-awareness that caused guilt at that time, so if this happens again, I will choose to face my boss in a rational way, and I will express my feelings to him in a tactful way, instead of arguing with him.

3.3.8. Grief and Loss

My grandfather passed away recently. Because of the deep relationship with my grandfather, I was actually quite shocked and sad. In that mood, I recalled the memories with my grandfather. After a period of time, my heart calmed down, and I thought about it from another angle, and my mood was more positive. And on the day of the funeral, although my emotions were still sad, they were much more relaxed than before.

I have slightly changed my view of death. If a person has been satisfied in this life, he also feels that he has no regrets, even in facing death. As for the death of my grandfather, it took me a while to fully recover. I diverted my attention by listening to music, exercising, and focusing on my assignments and activities.

Caring about her every move, maybe nothing to her, made me laugh and cry. For a few days, I tried to divert my attention. When I was too busy with schoolwork and other affairs, I felt even more empty. Maybe I didn’t have a good relationship with others. Besides the relationship between work and chatting with her, I seem to seldom chat with other friends. That’s why once I don’t maintain a relationship with her, I find that I really have nothing.

Taking a deep breath, clearing your head, and doing other things, which is what most people do, but unfortunately it doesn’t seem to work (for me).

The message is placed there (in my mind), and there are countless emotions in my head, I can’t stop thinking about it. Even after turning it off and doing other things, the message still lingers in my mind. The seemingly innocuous things, maybe because of her, make me very sensitive.

(May be) I don’t have to care what happened before. In the course of emotional management, I learned various theories and emotion-related research, and I also learned how to face up to my emotions and quickly discover my negative emotions. Be able to think about how to deal with it immediately after the emotional trigger and find out the ways before it will hurt other people, I think I am very proud to be able to check what attitude I use to face such a world and life.

4. Discussion

4.1. Role of the Emotional Management Course in Enhancing EI Levels

4.2. Patterns of Emotional Management

4.2.1. Pool of Negative Emotions

4.2.2. Triggers and Reasons

4.2.3. Theoretical Concepts

4.2.4. Intervention Strategies

5. Implications and Limitations

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- James, W. What is an emotion? Mind 1884, 9, 188–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darwin, C.R. The Expression of Emotions in Man and Animals; Murray: London, UK, 1872. [Google Scholar]

- Ekman, P. An argument for basic emotions. Cogn. Emot. 1992, 6, 169–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oatley, K.; Keltner, D.; Jenkins, J.M. Understanding Emotions, 2nd ed.; Blackwell Publishing: Washington, DC, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Cherry, K. The 6 Major Theories of Emotion. Verywell Mind 2023. Available online: https://www.verywellmind.com/theories-of-emotion-2795717 (accessed on 20 July 2023).

- Barrett, L.F.; Satpute, A.B. Historical pitfalls and new directions in the neuroscience of emotion. Neurosci. Lett. 2019, 693, 9–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Shawaf, L.; Conroy-Beam, D.; Asao, K.; Buss, D.M. Human emotions: An evolutionary psychological perspective. Emot. Rev. 2016, 8, 173–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishanu, K.D. A Study on Evolutionary Perspectives of ‘Emotions’ and ‘Mood’ on Biological Evolutionary Platform. Psychol. Behav. Sci. 2018, 7, 89–96. [Google Scholar]

- Perry, N.B.; Calkins, S.D. A biopsychosocial perspective on the development of emotion regulation across childhood. In Emotion Regulation: A Matter of Time; Cole, P.M., Hollenstein, T., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2018; pp. 3–30. [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus, R.S. Psychological Stress and the Coping Process; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1966. [Google Scholar]

- Schacter, S.; Singer, J.E. Cognitive, social, and physiological determinants of emotional state. Psychol. Rev. 1962, 69, 379–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ortony, A.; Clore, G.L.; Collins, A. The Cognitive Structure of Emotions; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Moors, A.; Ellsworth, P.C.; Scherer, K.R.; Frijda, N.H. Appraisal theories of emotion: State of the art and future development. Emot. Rev. 2013, 5, 119–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scherer, K.R. Emotion as a multicomponent process: A model and some cross-cultural data. Rev. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1984, 5, 37–63. [Google Scholar]

- Barrett, L.F.; Russell, J.A. The Psychological Construction of Emotion; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Goleman, D. Emotional Intelligence: Why It Can Matter More than IQ; Bantam Books: New York, NY, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Gardner, H. Frames of Mind: The Theory of Multiple Intelligences; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Sternberg, R.J. The Triarchic Mind: A New Theory of Human Intelligence; Penguin: New York, NY, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Petrides, K.V.; Furnham, A. On the dimensional structure of emotional intelligence. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2000, 29, 313–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, J.D.; Salovey, P.; Caruso, D.R. Emotional intelligence: Theory, findings, and implications. Psychol. Inq. 2004, 15, 197–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goleman, D. Working with Emotional Intelligence; Bantam Books: New York, NY, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Smagorinsky, P. The relation between emotion and intellect: Which governs which? Integr. Psychol. Behav. Sci. 2021, 55, 769–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cong-Lem, N. Emotion and its relation to cognition from Vygotsky’s perspective. Eur. J. Psychol. Educ. 2023, 38, 865–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrides, K.V.; Mavroveli, S. Theory and applications of trait emotional intelligence. Psychology 2018, 23, 24–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-González, J.-C.; Saklofske, D.H.; Mavroveli, S. Editorial: Trait emotional intelligence: Foundations, assessment, and education. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, J.D.; Caruso, D.R.; Salovey, P. The ability model of emotional intelligence: Principles and updates. Emot. Rev. 2016, 8, 290–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiori, M.; Vesely-Maillefer, A.K. Emotional Intelligence as an ability: Theory, challenges, and new directions. In Emotional Intelligence in Education: The Springer Series on Human Exceptionality; Keefer, K., Parker, J., Saklofske, D., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elfenbein, H.A.; MacCann, C. A closer look at ability emotional intelligence (EI): What are its component parts, and how do they relate to each other? Soc. Personal. Psychol. Compass 2017, 11, e12324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maddocks, J. Introducing an attitude-based approach to emotional intelligence. Front. Psychol. 2023, 13, 1006411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durand, K.; Gallay, M.; Seigneuric, A.; Robichon, F.; Baudouin, J.Y. The development of facial emotion recognition: The role of configural information. J. Exp. Child Psychol. 2007, 97, 14–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosonogov, V.V.; Vorobyeva, E.; Kovsh, E.; Ermakov, P.N. A review of neurophysiological and genetic correlates of emotional intelligence. Int. J. Cogn. Res. Sci. Eng. Educ. 2019, 7, 137–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, J.D.; Salovey, P. What is emotional intelligence? In Emotional Development and Emotional Intelligence: Educational Implications; Salovey, P., Sluyter, D.J., Eds.; Basic Books, Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 1997; pp. 3–34. [Google Scholar]

- Mckenna, J.; Webb, J. Emotional intelligence. Br. J. Occup. Ther. 2013, 76, 560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bucich, M.; MacCann, C. Emotional intelligence research in Australia: Past contributions and future directions. Aust. J. Psychol. 2019, 71, 59–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeidner, M.; Roberts, R.D.; Matthews, G. Can emotional intelligence be schooled? A critical review. Educ. Psychol. 2002, 37, 215–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacCann, C.; Jiang, Y.; Brown, L.E.; Double, K.S.; Bucich, M.; Minbashian, A. Emotional intelligence predicts academic performance: A meta-analysis. Psychol. Bull. 2020, 146, 150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, K.B.L.; Bharamanaikar, S.R. Emotional intelligence and effective leadership behaviour. Psychol. Stud. 2004, 49, 107–113. [Google Scholar]

- Chapman, M. Emotional intelligence and coaching. In Evidence-Based Coaching: Theory, Research and Practice from the Behavioural Sciences; Cavanagh, M., Grant, A.M., Kemp, T., Eds.; Australian Academic Press: Bowen Hills, Australia, 2005; Volume 1, pp. 183–192. [Google Scholar]

- Hess, J.D.; Bacigalupo, A.C. Enhancing decisions and decision-making processes through the application of emotional intelligence skills. Manag. Decis. 2011, 49, 710–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, R. A Study Exploring the Link between Emotional Intelligence and Stress in Front-Line Police Officers. Master’s Thesis, Goldsmiths College, University of London, London, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Weisinger, H. Emotional Intelligence at Work; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh, H.-F.; Shannon, S.E. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual. Health Res. 2005, 15, 1277–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schilling, J. On the pragmatics of qualitative assessment: Designing the process for content analysis. Eur. J. Psychol. Assess. 2006, 22, 28–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pallant, J. SPSS Survival Manual; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Edara, I.R. Exploring the relation between emotional intelligence, subjective wellness, and psychological distress: A case study of university students in Taiwan. Behav. Sci. 2021, 11, 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, B.; Fletcher, T.; Parker, S.J. Enhancing emotional intelligence in the health care environment: An exploratory study. Health Care Manag. 2004, 23, 225–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gratz, K.L.; Roemer, L. Multidimensional assessment of emotion regulation and dysregulation: Development, factors structure, and initial validation of the Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale. J. Psychopathol. Behav. Assess. 2004, 26, 41–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American College Health Association (ACHA). American College Health Association- National College Health Assessment II: Reference Group Executive Summary; American College Health Association: Silver Spring, MD, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Auerbach, R.P.; Alonso, J.; Axinn, W.G.; Cuijpers, P.; Ebert, D.D.; Green, J.G.; Hwnag, I.; Kessler, R.C.; Liu, H.; Mortier, P.; et al. Mental health disorders among college students in the World Health Organization World Mental Health Surveys. Psychol. Med. 2016, 46, 2955–2970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, H.; Carney, D.M.; Youn, S.J.; Janis, R.A.; Castonguay, L.G.; Hayes, J.A.; Locke, B.D. Are we in crisis? Psychol. Serv. 2017, 14, 407–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beck, A.T.; Epstein, N.; Harrison, R. Cognitions, attitudes and personality dimensions in depression. Br. J. Cogn. Psychother. 1983, 1, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Dobson, K.S.; Block, L. Historical and philosophical bases of cognitive behavioral theories. In Handbook of Cognitive Behavioral Therapies; Guilford Press: London, UK, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Arnold, M.B. Emotion and Personality; Columbia University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1960. [Google Scholar]

- Hughes, D.J.; Kratsiotis, I.K.; Niven, K. Personality traits and emotion regulation: A targeted review and recommendations. Emotion 2020, 20, 63–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schindler, S.; Querengässer, J. Coping with sadness—How personality and emotion regulation strategies differentially predict the experience of induced emotions. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2019, 136, 90–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deci, E.L.; Ryan, R.M. The “what” and the “why” of goal pursuits: Human needs and the self-determination of behavior. Psychol. Inq. 2000, 1, 227–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vansteenkiste, M.; Ryan, R.M. On psychological growth and vulnerability: Basic psychological need satisfaction and need frustration as an unifying principle. J. Psychother. Integr. 2013, 3, 263–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rotter, J.B. Generalized expectancies for internal versus external control of reinforcement. Psychol. Monogr. Gen. Appl. 1966, 80, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rotter, J.B. Some problems and misconceptions related to the construct of internal versus external control of reinforcement. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 1975, 43, 56–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Course Contents | Min | Max | Mean | SD | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Concepts | Concepts, Definitions, Categories, Functions | 3.00 | 10.00 | 7.17 | 1.72 |

| Physiology and Emotions | 3.00 | 10.00 | 7.37 | 1.76 | |

| Emotions and Cognition | 3.00 | 10.00 | 7.65 | 1.64 | |

| Personality and Emotions | 3.00 | 10.00 | 7.11 | 1.42 | |

| Emotions in the Context of Family | 3.00 | 10.00 | 7.67 | 1.59 | |

| Social Culture and Emotions | 3.00 | 10.00 | 7.63 | 1.57 | |

| Contemporary Media Influence on Emotions | 3.00 | 10.00 | 7.39 | 1.48 | |

| Emotional Management & Technology Development | 3.00 | 10.00 | 6.89 | 1.66 | |

| Emotions in Interpersonal Relations | 3.00 | 10.00 | 7.74 | 1.56 | |

| Emotions and Metaphors | 3.00 | 9.00 | 6.54 | 1.66 | |

| Applications | “The Angry Birds” Movie and Discussion | 3.00 | 10.00 | 7.04 | 1.44 |

| Analysis of Prominent Figure (Ex: Trump) | 3.00 | 10.00 | 6.46 | 1.77 | |

| EQ Questionnaire and Analysis | 3.00 | 10.00 | 7.81 | 1.45 | |

| Personality Test and Analysis | 3.00 | 10.00 | 7.74 | 1.68 | |

| “Inside Out” Movie and Individual Reflection | 3.00 | 10.00 | 9.00 | 1.55 | |

| “Inside Out” Movie, Group Discussion and Oral Report | 3.00 | 10.00 | 8.15 | 2.04 | |

| Exercise on Developing an Emotional Vocabulary | 3.00 | 10.00 | 6.76 | 1.72 | |

| In-vivo Exercise in Expressing Emotions | 3.00 | 10.00 | 7.28 | 1.69 | |

| Exercise on Needs, Metaphors, and Emotions | 2.00 | 9.00 | 6.63 | 1.72 | |

| Group Exercise on Constructing EI Patterns | 2.00 | 10.00 | 7.37 | 2.03 | |

| Weekly Journaling and Analysis of Emotions | 3.00 | 10.00 | 7.63 | 2.03 | |

| Paper on Personalized Emotional Management Pattern | 2.00 | 10.00 | 7.02 | 2.18 | |

| Emotion (Freq): P# | Trigger/Reason (Freq) | Theories | Response Strategies |

|---|---|---|---|

| ⟫ Interpersonal ⟫ View of Success ⟫ Academics ⟫ Communication ⟫ Personality ⟫ Self-blame ⟫ Self-value ⟫ Other’s expectations ⟫ Family matters ⟫ Irrational reasoning ⟫ Self-expectations ⟫ Blame surroundings ⟫ Self-repression ⟫ Pessimistic thinking ⟫ Different values ⟫ Different thinking styles ⟫ Can’t accept failure ⟫ Lose face ⟫ Others’ opinion ⟫ Perfectionism ⟫ Self-denial ⟫ Time management ⟫ Unfamiliar contexts ⟫ Self-doubt ⟫ Polarizing ⟫ Over sensitive ⟫ Ambiguous ⟫ Excessive comparison ⟫ Future concerns ⟫ Collaboration ⟫ Heavy sense of mission ⟫ Inferiority complex ⟫ Shy nature | ⟫ Ellis ⟫ Bowen ⟫ Lazarus ⟫ Rotter ⟫ Personality ⟫ Rogers ⟫ Maslow ⟫ Beck ⟫ Family of origin ⟫ Behavioral theory | ⟫ Different value perspective ⟫ Useful Communication ⟫ Divert attention/focus ⟫ Talk with friends/share with family ⟫ Detailed daily schedule ⟫ Improve self-efficacy ⟫ Develop can-do attitude ⟫ Habit of maintaining emotions journal ⟫ Reading and being active ⟫ Think of good times ⟫ Express appropriately ⟫ Face them with positive attitude ⟫ Do proper analysis and processing ⟫ Clarify personal needs ⟫ Deep breathing ⟫ Emptying mind ⟫ Acknowledge the influence of cultures ⟫ Exercise/sports ⟫ Share with like-minded friends ⟫ Do not care what others think ⟫ Affirm oneself ⟫ Develop self-confidence ⟫ Self-acceptance ⟫ Movies/music/sleep ⟫ Travelling ⟫ Seek other’s opinion ⟫ Trace the source of emotions ⟫ Deal objectively ⟫ Isolation ⟫ Adjust mentality ⟫ Deal positively ⟫ Engage in mental exercises ⟫ Be responsible ⟫ Self-exploration and observation ⟫ Positive self-talk ⟫ Accept the unchangeable ⟫ Maintain rationality ⟫ Change mind/think differently ⟫ Avoid unnecessary comparisons |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Edara, I.R. Analysis of Students’ Emotional Patterns Based on an Educational Course on Emotions Management. Educ. Sci. 2023, 13, 757. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci13070757

Edara IR. Analysis of Students’ Emotional Patterns Based on an Educational Course on Emotions Management. Education Sciences. 2023; 13(7):757. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci13070757

Chicago/Turabian StyleEdara, Inna Reddy. 2023. "Analysis of Students’ Emotional Patterns Based on an Educational Course on Emotions Management" Education Sciences 13, no. 7: 757. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci13070757

APA StyleEdara, I. R. (2023). Analysis of Students’ Emotional Patterns Based on an Educational Course on Emotions Management. Education Sciences, 13(7), 757. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci13070757