1. Introduction

The aim of this research is to capture teachers’ views on the knowledge [

1] (p. 9) and skills [

2] (p. 21) they need for classroom teaching in relation to the structure of the tenure examination as a form of staff selection in pre-university education.

In Romania, tenure examinations are held annually in May-June to obtain a job in pre-university education. Tenure, according to the

Explanatory Dictionary of the Romanian Language, is defined as “a competition through which a teacher can become a tenured teacher in a pre-university education position” [

3].

According to current legislation and for most candidates, since 2012 with a brief exception during the pandemic period, the tenure exam has two tests: a classroom inspection and a theoretical exam. The classroom inspection is first, and a grade under 5 does not allow the candidate to participate in the written examination. The final mark is made up of an average of the grades from the two tests; this average is composed of 25% of the grade from the inspection and 75% of the grade from the theoretical exam [

4,

5]. The exceptions are a small number of candidates who also take a practical test (e.g., foremen, nurses, etc.).

The two exams should assess the competences and skills needed by a teacher and the knowledge to be presented in front of students, as a recruitment and selection filter [

6]. For this reason, the subjects are unique, each matter with its own subjects, applied and corrected at national level, in county examination centres, regardless of the need for staff in each county in a specific year.

Knowledge and understanding of the subject matter are important both in the recruitment process and for classroom work. This knowledge has a global meaning and manifests itself differently from one teacher to another. Thus, we have teachers who know the subject matter and can reproduce the information accurately, we have teachers who know and understand the subject matter and are capable to adapt it to make it accessible to pupils, and we have teachers who are scholars, those who demonstrate an in-depth knowledge of one or more sciences beyond school subject matter. In the teaching process, knowledge of the subject matter is valuable, but the act of teaching must consider the pupils in front of them, the level of the class and their ability to understand the material.

We cannot constructively explore this topic of teachers’ knowledge of a subject without clarifying the meaning of each area of knowledge. Thus:

“Knowledge and understanding of the subject matter” is a concept through which we refer to the global and in-depth meaning correlated with that baggage of knowledge that (however it manifests itself) is mandatory for the teacher to have to transmit to the student. In this research, the focus is not on knowing pedagogical information or the knowledge of the pupil but simply on the knowledge of the subject that the teacher must transmit to the pupil. In this context, knowledge is “the fact of possessing knowledge, information given on a subject, on a problem” [

3].

“Erudition” is defined as “deep and thorough knowledge of one or more sciences; broad and thorough culture” [

7]. Other sources define erudition as knowledge “acquired mainly through lectures” [

8,

9]. The concept will be used in this paper with this broad meaning referring to a wider range of knowledge, the correlations that the teacher can make with knowledge from other fields and an ability to span several fields.

“The ability to accurately render content” is understood as the “ability, aptitude, strength to do something in a given field” [

8]. Such a capacity refers to a good memory and knowledge but, at the same time, a certain rigidity in the teaching of knowledge. The teacher remains trapped in a teaching style that follows textbook formulations or long-used personal schemes. The emphasis here is on the ability to memorise and reproduce knowledge.

The ability to adapt content to be accessible to learners is used in our study in the sense of “aptitude, skill, ability, talent” [

10]. Thus, the ability to adapt the content of a teaching material to make it understandable to the learner is nothing more than the ability to adapt a material, to “transform it to meet certain requirements; to make it suitable for use in certain circumstances; to make it fit” [

3]. Such a capacity heralds a certain flexibility, creativity and adaptation of teaching to the learner. In this case, the focus is on the learner and not just on the knowledge to be transmitted. Teaching becomes, in this case, a pedagogical act with two main actors: the pupil and the teacher.

In teacher training and recruitment policies, the presence of competences and their assessment is an extremely important issue. They play a key role in making education more effective. We distinguish between efficiency [

11] as an expression of achieving results with minimal resources and effectiveness as an expression of achieving results in line with a set of proposed objectives [

12,

13]. In this case, we must mention Caroll’s approach, which, in 2023, assesses teachers’ knowledge of models and modelling in the STEM (science, technology, engineering and mathematics) subject area by considering the content knowledge of model-based instruction versus the pedagogical application competence of model-based instruction [

14], and the results underline the increased effectiveness of competence assessment over teacher knowledge assessment.

Other research in this area highlights that the teacher has an important role to play in students’ development and achievement. Research carried out by Hattie in Aukland in 2003 on a sample shows that 30% of the time the teacher is considered to be responsible for the achievements of the pupils [

15]. The same research shows that 50% of pupils are directly responsible for their achievements. The remaining percentages are distributed between family, school, principals and peer group influence. This analysis looks at differences in student achievement by teacher type differentiating between novice, experienced and expert teachers. Another study of the situation 10 years later in the area of science teaching [

16] points out that there is an unequivocal link both between student achievement and teacher knowledge and between teacher knowledge (and its kind) and a student’s general attitude towards science. The authors also mention the need to use interactive methods, in-depth comprehension, exemplification, summative evaluation to increase interest in the subject and emphasising skills rather than just knowledge. However, the research [

16] makes no reference to the link between national assessments at the end of a school cycle and a teacher’s ability to structure subject matter and learning. National assessments of pupils in Romania focus on a series of indicators that privilege the mastery of algorithms for learning and solving the requirements of an exam so that the student can accumulate as many points as possible [

17]. In this case, the emphasis is not necessarily on creativity, originality and the ability to synthesise and integrate the content learned into a broader structure but on reproducing the content accurately, mastering the algorithms and focusing on obtaining the best possible score. All these become a priority in the teaching act in the face of the development of positive attitudes and personalised understanding. More specifically, when the teacher does not follow the algorithms, trying to develop knowledge based on understanding, insisting on a positive attitude from students towards the subjects taught, the final grade obtained in the national assessments is negatively influenced. Obviously, the opposite is also possible. Therefore, pupil performance, as measured in the current way, captures a number of aspects such as the ability to solve a requirement/problem in a certain way; the ability to reproduce content accurately is scored higher than the ability to capture an original idea and the teacher, from this perspective, in order to be appreciated, is forced to focus on knowledge with an immediate impact of good results, not on the attitude towards knowledge nor on the adaptation of content that demonstrates high sustainability. This learning model is also dictated and reinforced by the teacher’s assessment upon entering the system, which is achieved according to similar criteria: candidates are assessed on their ability to reproduce content and perform tasks/problem solving in a clearly defined way, without observing their attitude towards the subject (passion, love) or their ability to be creative and innovative.

Another related research in 2015 [

18] shows that the conception of learning as understanding was positively associated with the self-efficacy of university students with biology-related majors. However, the conception of learning as memorising may foster students’ self-efficacy only when such a notion co-exists with the conception of learning with understanding. So yet again, learning is better associated with understanding and memorising cannot lead to self-efficacy without understanding. Also, in 2021, the preservice science teachers “believed that science should be learned not by memorising, that should be learned by experimenting, and by integrating it into daily life” [

19].

Seen as a whole, the process of selecting and recruiting personnel in an organisation works on the principle of an old Romanian saying: “the right person in the right place” [

20,

21]. In education, selection exams (for substitution and tenure) decide who is allowed to be a teacher in front of pupils.

Our research is based on the “Knowledgeable Teacher Hypothesis”, which argues that the whole learning process cannot take place without a high level of teacher knowledge. However, in our research we try to find out exactly what kind of knowledge is necessary for a successful career as a Romanian teacher, what kind of knowledge is assessed when entering the system and what kind of knowledge is valued [

22] in front of a class.

An approach that views this teacher knowledge in a similar way to our research vision highlights the differences between teachers’ professional knowledge in relation to its future use: “teachers have to apply their knowledge to implement instructional strategies or to diagnose students’ (mis)conceptions or their current level of knowledge” [

23]. The focus is thus more on referring to a corrective level of knowledge and information already held and on instructional strategies. In the above-mentioned research, different models of knowledge structuring are discussed, such as the Shulman model which considers “strategic knowledge, case knowledge and propositional knowledge” [

24] and introduces a two-dimensional model of professional knowledge as “content-related facets of knowledge” [

23], which places professional knowledge between “knowing” (a) that, (b) how, (c) when and why. In fact, Hattie [

15] nuances the same model as Schulman [

24]. Starting from this research context and customising with the specifics of our own research, our model has emerged as follows in

Figure 1:

Although it would be interesting to keep the nuances referring to the type of information as mentioned in the model article (“content knowledge”—CK, “pedagogical content knowledge”—PCK and pedagogical–psychological knowledge—PK), which helps us to see a positioning of the domain of information in relation to its manifestation, we will refer to the perception of classroom evaluation (P.C.E) and the perception of examination evaluation (P.E.E).

Starting from this model but in a different context, we will measure the perception of the evaluation of all three (plus the general meaning) manifestations of knowledge in two different environments: classroom and examination. In the extended table of our results, P.C.E will have four subdivisions (utility, impact in case of absence, impact on pupil activity and impact in work efficiency) and P.E.E will have two subdivisions (exam inspection and theoretical examination) so that we can clearly view how important they are perceived to be.

2. Materials and Methods

Our research was a quantitative one that involved the use of a questionnaire and the analysis of an existing dataset. In the case of the analysis, we statistically centralised the marks obtained by candidates in the 2019 tenure exam in Romania. The tenure exam grades are published on

www.titularizare.edu.ro (accessed on 20 November 2022). The questionnaire comprised only adult volunteer respondents that declared to be employed in the educational system, and thus google forms did not allow the same account to answer twice; the settings were to not collect any nominal or personal data (email included). The questionnaire started with an informed consent form and information about the aim of the research.

The research objectives are as follows:

To highlight the dimensions of knowledge and their importance in the classroom teaching activity carried out by teachers;

To identify teachers’ perceptions of how the examinations (classroom inspection and written examination) assess these dimensions of knowledge.

Research hypotheses:

There is a significant difference between how teachers perceive the importance of the dimensions of subject knowledge in the classroom and how they are assessed in the inspection of the tenure exam;

There is a significant difference between how teachers perceive the importance of the dimensions of classroom knowledge and how they are assessed in the written tenure examination.

The time period for answering the questionnaire was 28 August 2022–14 November 2022. The questionnaire was designed in Google Forms (

https://docs.google.com/forms) and self-administered; it could be answered by accessing the link on different digital platforms: email, WhatsApp groups and Facebook.

The sample of respondents consisted of 1154 teachers from all over the country and was constructed using the snowball method. When the number of respondents deemed necessary to ensure representativeness across the eight regions of the country under consideration was reached, the application of the questionnaire in that region was stopped. Respondents were selected on the basis of their status as teachers in pre-university education. The data in the “No. of teachers employed” section were calculated from the Excel form attached to the official portal data.gov.ro, which aims to centralise the open data published by Romanian institutions according to the principles and standards in the field [

25]. For this reason, we consider the sample to be representative and its structure to be as follows in

Table 1:

In order to obtain a clearer picture of the sample of teachers and other variables that may influence the feedback they provide and the way they relate to the tenure exam or to their classroom work, we analysed the structure of the sample also from the perspective of the specifics of the subjects taught (real, real and human, human, therapies/support) and from the perspective of their professional status (all respondents are active classroom teachers and therefore passed the exam with different grades). Thus, the structure of the investigated sample can be characterised and re-presented as follows, also outlined in

Table 2:

Permanent, qualified employee;

Qualified substitute, fixed-term employee;

Unqualified substitute, fixed-term employee.

The questionnaire had the following structure:

Five questions that included independent variables such as the membership of the category of respondents, region, class level, professional status and domain of subjects taught which played a role in establishing representativeness;

Three questions assessing the perception of the overlapping meanings of the three dimensions subordinate to subject knowledge (three items), with a scaled response from 1 to 5, where 1 means not at all and 5 means very much;

Sixteen questions that included variables such as knowledge and understanding, ability to accurately render content, ability to adapt content to be accessible to students and erudition in terms of usefulness, ability to be a good teacher in the absence of that dimension and improvement in the work of the beneficiary students and facilitation of the teacher’s work. All questions had scaled responses from 1 to 5, where 1 means not at all and 5 means very much, with only one possible answer selection—these items achieved a Chronbach’s Alpha coefficient of 0.834, showing good internal consistency;

Eight questions assessing perceptions of how the two parts of the tenure exam (classroom inspection and written exam) assess the four dimensions of knowledge. These items have scaled responses from 1 to 5, where 1 means not at all and 5 means very much so, with only one possible answer selection—these items have a Chronbach’s Alpha coefficient of 0.871, showing good internal consistency;

Four questions assessing the choice of preferred methods for assessing the dimensions in the tenure examination—respondents had to choose from 15 proposed method groupings, the condition was not to choose more than 5 methods, but they also had the possibility to fill in an answer if they did not consider the formulated options exactly matched with their preferences.

3. Results

The data obtained from the questionnaire were processed in SPSS.

The analysis methods used were parametric because the large number of respondents and national representativeness indicated this. Based on a population of 262,680 teachers, we have 1154 respondents, so our sample is 0.44% of a generous professional population, proportionally distributed for each region of the country, so the parametric procedure is more efficient in this case.

The method of analysis used an ANOVA with repeated measures to highlight the significance, and then we confirmed these results using paired samples t-tests in the cases highlighted by the ANOVA (to compare two by two and to qualify the results obtained with the ANOVA).

3.1. Overlapping Meanings in the Manifestation of the Dimensions of Knowledge

Because we measure perception and perception is influenced by how each respondent understands applied and different meaning, in this section we want to highlight the extent to which teachers perceive the manifestations of knowledge as interrelated. Thus,

Table 3 centralises the answers as follows:

Of the respondents, 50.4% consider that “to a very great extent” a person who understands and knows a content without reproducing it exactly has the ability to adapt it to be accessible to students, while only 15.7% of the respondents consider that “to a very great extent” a person who learns a content in order to render it exactly has the same ability to adapt it to students’ understanding. In the items in which “rendering content” appears, most responses peak towards the middle of the options (“neither a lot nor a little”), regardless of whether the analysis is compared with the nuances of knowledge referring to the general terminology of “knowledge and understanding” or the specific terminology of “adaptation for accessibility”.

3.2. Importance of In-Class ”Knowledge of the Matter”

3.2.1. Structure and Argumentation

In this research, in order to assess the importance of the four dimensions of knowledge in the professional work carried out in a classroom, we designed four types of questions that we will generically call “filters” through which the dimensions were passed (to avoid repetition and confusing formulations, we will refer to each of them as X).

1st Filter—“Utility”: In sociology, psychology and especially economics, utility is an abstract concept that measures a user preference by referring to “the ability of a good (material, service, information) to satisfy a need” [

26]. In our case, it is the need of a teacher to present themselves in front of a class showing a good knowledge of the subject in order to obtain optimal academic results from the students.

2nd Filter—“Good in the absence of”: “To what extent can the teacher be good in the absence of X”—or, more specifically, to further nuance, “can the teacher be good in the absence of in-depth knowledge of the subject matter to be taught?” is an item formulated to track whether there is a perception of the teaching act outside of the content that the teacher delivers to his/her students. Certainly, there are nuances—explicitly, a preschool teacher may feel that he or she has put more effort (and therefore would be more aware) into knowing the right teaching methods than into learning the numbers he/she teaches, but equally, a teacher lacking knowledge or understanding on numbers cannot teach his or her pupils to use them.

3rd Filter—“Improves student activity”: This learner-impact approach seeks to disentangle the importance of knowledge manifestations from the outcome of the whole pedagogical process. However, following on from Kunter’s definition [

27] comes a definition that shades “teacher quality” beyond standardised test results, with a more qualitative than quantitative approach, thus “in a word, the teacher’s job is well beyond preparing students for ‘get the answer right’ standardised testing but to engage the students’ more sophisticated skill levels around such features as ‘communicative capacity’ and ‘self-reflection’” [

28].

4th Filter—“Make work easier”: Certain manifestations of knowledge can make it easier for the teacher to work in the classroom, and this aspect, confirmed by teachers’ perceptions, could justify differences in the evaluation of the dimensions of the tenure exam versus classroom work. If this expectation is confirmed, this item can give us a 360° view and succeed in justifying the differences analysed by the hypotheses.

3.2.2. Answers

Table 4 shows the structure of the items and their generic names as well as the percentages on answers obtained:

3.2.3. Observations

We note that 92.7% of respondents chose the highest value of usefulness for “ability to adapt content to be accessible to students”. Although we cannot quantify this ability (we cannot axiomatise it and do not identify an independent measure of its manifestation), we note that it is rated as “very highly” useful, more so than the other dimensions of knowledge, receiving even 51.2% more top ratings than the “ability to render content accurately”.

Although slightly counter-intuitive, we note that there is still an extent to which teachers perceive that they can be good teachers in the absence of these manifestations of knowledge, and the top responses were less selected than in the previous filter. Only 60% of respondents felt that you cannot be a good teacher at all in the absence of knowledge and understanding of the subject matter.

In the area of improving student work, we observe the preference for maximum scores in the area of the “ability to adapt content” by 80.9% of respondents, while only 41.9% chose the same option in the “ability to render content accurately”.

“Makes the work easier” does not confirm intuitive expectations but still highlights the perceived higher importance of the ability to adapt content to be accessible to students. Intuitively, we believe that this “ability to render content accurately” can make the teacher’s work easier in the sense that being less understood as “knowledge and understanding”, it relieves the teacher of the effort of analysing what is said, of formulating it appropriately, having already “learned” the formulation. So, the answers obtained are counter-intuitive from this perspective.

3.3. Knowledge Evaluation in Recruitment

As part of the tenure exam, after submitting their application and registering for the examination, candidates receive a class to take the practical exam. For those who are already employed in the system as substitutes (qualified or unqualified), with experience comes the added benefit of taking the inspection in their own classroom, while novices receive a randomly chosen classroom. Regardless of category, the subject of the lesson to be prepared is randomly allocated. Some of the novices visit the class to get to know the pupils; some of the candidates see the pupils for the first time directly at the inspection. The lesson is attended by two inspectors who assess the candidate’s behaviour and skills on the basis of Evaluation Sheet—Annex No. 5 [

4].

After the inspection, follows the knowledge test. The number of participants in the knowledge exam is smaller than the number of participants in the inspection because, following the experience, some drop out and some are not allowed to take part. The written exam has a standard format and consists of three subjects: the first one assesses knowledge of the subject, the second one assesses knowledge of school pedagogy and problem-solving skills, and the third one is a subject on teaching methodology. Unfortunately, there are books written in order to solve each kind of subject without being original, just by rendering the exact solutions others found.

Candidates perceive the knowledge assessment of the two tests as follows in

Table 5:

As

Table 5 measures, the teacher’s perceptions of the extent to which these two types of examination assess these dimensions of knowledge, we see that, although to a lesser extent than the perception of classroom assessment, teachers perceive that the inspection most assesses the capacity to adapt content. However, “erudition” this time obtains the lowest number of maximum responses. The very large differences in the assessment of the written exam are visible, where the “knowledge and understanding of subject matter” with non-specific meaning is in first place, and the “ability to render content accurately” is in second place with a 3.8% difference in maximum responses.

From the website

www.titularizare.edu.ro ([

29], accessed on 20 November 2022), we have retrieved and processed the publicly and nominally displayed data (in the absence of any GDPR form whereby candidates agree to the unprotected publication of results) with the marks obtained in the two rounds of the 2019 tenure exam (the last pre-pandemic year in which the tenure exam was held with both rounds) [

30]. In the practical test, we centralised the results of 26,185 candidates and in the theoretical test, 19,507 candidates, and the distribution of marks is shown in

Table 6.

Consequently, we can see that for 71.89% of candidates, the classroom inspection test is not a real differentiating factor in recruitment, and this conclusion justifies the low percentage of influence on the final average of tenure, even though this could really help candidates evolve in the field of activity.

3.4. Hypothesis Confirmation

If the above interpretation of the results was based on a visual evaluation of the percentages of options for responses correlated with a maximum importance/assessment, the SPSS analysis is based on a comparison between the means of the responses, and for easier reference, we centralise them in

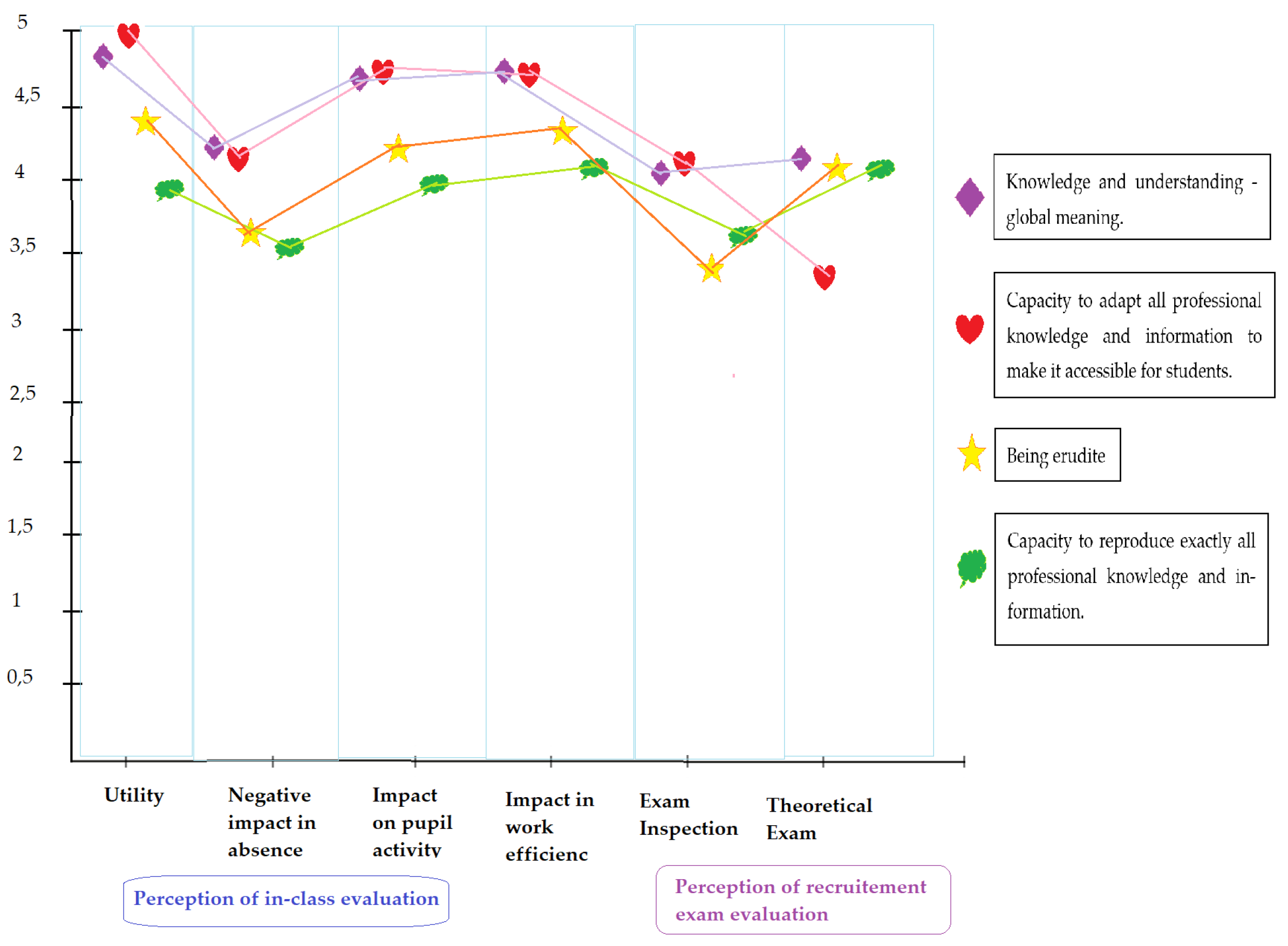

Table 7, as follows:

Visually, the difference between the averages of the responses can be seen in

Figure 2, as follows:

Hypothesis 1: There is a significant difference between how teachers perceive the importance of the dimensions of subject knowledge in the classroom and how they are assessed in the inspection of the tenure exam.

The repeated measures ANOVA confirms, with F(1.1153) = 28.850, p < 0.001, that there are significant differences between the perception of the assessment of knowledge manifestations in the classroom versus the perception of the assessment of knowledge manifestations at the entrance examination.

Analysing each compared pair in depth (basically, we compared the results of the perception assessment of the inspection knowledge manifestation and compared them one by one with the result of that knowledge manifestation for each filter), we found that the paired

t-tests also show significant differences, as shown in

Table 8.

In conclusion, Hypothesis 1 is partially verified and mostly confirmed, so there are significant differences between the way knowledge manifestations are perceived to be evaluated in the classroom versus in the tenure exam, with the following nuances: “knowledge and understanding of subject matter”, “erudition”, “ability to render content accurately” and “ability to adapt content to be accessible to students” are perceived to be more strongly evaluated as useful, with a stronger negative impact in their absence, influencing student action more and making the teacher’s work in the classroom easier than how they are evaluated in the tenure exam inspection, with two exceptions:

there are no significant differences between how the classroom assessment of the impact of the ability to adapt content to be accessible to students is perceived to impact the classroom assessment of the ability to adapt content to be accessible to students in the tenure exam inspection;

the ability to accurately render content is perceived to be significantly more highly rated in the tenure exam inspection than the perceived negative impact of its absence on the teacher in front of a classroom of students.

Hypothesis 2: : There is a significant difference between how teachers perceive the importance of the dimensions of classroom knowledge and how they are assessed in the written tenure examination.

The repeated measures ANOVA confirms, with F(1.1153) = 232.842,

p < 0.001, that there are significant differences between the perception of the assessment of knowledge manifestations in the classroom versus the perception of the assessment of knowledge manifestations in the written exam of the tenure examination, as follows in

Table 9:

In conclusion, Hypothesis 2 is partially confirmed, so there are significant differences between the way in which the manifestations of knowledge are perceived to be evaluated in the classroom and the theoretical test of the tenure exam, with the following nuances:

- “knowledge and understanding of subject matter”, “erudition” and “ability to adapt content to be accessible to students” are perceived to be more strongly evaluated as useful, with a significant negative impact in their absence, influencing students’ work more and easing the teacher’s work in the classroom compared to how they are perceived to be evaluated in the theoretical exam of the tenure exam.

- “the ability to reproduce content accurately” is perceived as being less frequently assessed in the theoretical part of the tenure exam and less frequently assessed as useful, with a weak negative impact in its absence, influencing the students’ work a little and easing the teacher’s work insignificantly.

3.5. Solutions

As this research aims to identify potential recruitment problems regarding the practical needs and solve them constructively and effectively, we questioned respondents on the methods of assessment and recruitment in pre-university education. More specifically, we wanted to find out whether, in their opinion, evaluation and recruitment methods succeed in selecting the most suitable candidates, and thus whether they have a predictive role (the marks obtained in the exam being correlated with the evaluations the candidate will receive for his/her classroom work). In addition, we asked them to identify which methods would be most suitable for highlighting the exact manifestations of knowledge that will subsequently be used in the classroom.

For this purpose, we provided respondents with a list of 15 assessment methods and ways (some already used in Romania, others used in recruitment systems of other countries, and some “borrowed” from student or other employee assessments), together with an invitation to choose up to the 5 most suitable ones and the possibility to respond by adding new methods. We estimate that a part of the respondents will decide that there are no better methods than the existing ones, while another part of the respondents will look for innovative solutions. In the list of 15, there is also the option to select “it is not necessary to be a good teacher, you do not have to evaluate”.

The list of options includes the following:

Not required to be a good teacher, should not be assessed at all in recruitment;

Knowledge assessment test with standard topics to reproduce information covered by subject matter experts;

Knowledge assessment test with practical applications and examples, identification of original solutions;

Classroom practice test with class and topic revealed on the same day;

Practical test in a known class with a prepared topic (for beginners, practice hours in that class will be provided well in advance of the exam);

Role-play with the given topic, individually or in a group, in front of the assessors—situational assessment under exam conditions;

Conversation with counterparts on a given topic/issue with moderation by assessors (who follow the demonstration, etc.)—situational assessment under exam conditions;

Oral reproduction of required content (memory check, poems, songs or definitions);

Oral or written self-assessment;

Assessment/observation sheets (completed by assessors, supervisors, colleagues, pupils, parents of pupils, support staff, following previous experience or practice period, etc.);

Psychological test (created and applied specifically for this dimension);

Extemporal, thesis, grid test, questionnaire;

Essay, report, portfolio, project, homework assignment;

Activity plan, career plan, classroom management plan, community development through education plan, etc.;

Brainstorming with counter-candidates on a given theme/problem to map solutions, moderated by assessors;

Other:______________________.

In the following

Table 10, we will present only the most relevant and most frequent options (top three for each dimension) but also those answers that raise questions or deviate from the average.

The current methods of evaluation in the tenure examination remain preferred but with clear definitions of situations that reduce disparities between those who already substitute and candidates who come from outside the system. Surprises are the entry into the top choices of the conversation with counter-candidates on a given topic/issue with moderation by the assessors but also the role-play with the given topic, individually or in groups, in front of the assessors.

4. Discussion

A systemic, recruitment-focused approach that punctually and predominantly assesses a teacher’s ability to adapt content to make it accessible to students could start by giving additional marks to the innovative approach to knowledge assessed through restructuring, reorganisation and rephrasing because only a good subject matter expert can do this without negatively impacting the quality of the information. In correlation with the Schulman model [

24], topics which instead of assessing “that” knowledge (“what” or “that”), assess original, applied interpretations of “how”, “when” and “why” would be more relevant.

Our ”filters” need to be more profoundly understood and debated. For an assessment of the general perception of usefulness, the items are clear and comprehensive, but for a nuance of the differences in the understanding of the dimensions of knowledge, they must be accompanied by other filters. Utility is subjective in this case and is predominantly addressed in terms of perception, although there are attempts at “axiomatisation” as identified in the article “Subjectivity of expected utility in incomplete preferences” [

31]. The lack of the predominance of average (3) responses shows that respondents have clear opinions on this topic. Also, the approach in the academic literature often focuses on “teacher knowledge” in the sense of “pedagogical knowledge”, as found, for example, in official OECD reports [

32], or the “knowledge of students” and less often on the knowledge of the subject matter; although, in practice, in the absence of subject knowledge, the object of the teacher’s work disappears.

In relating to the attribute “good/valuable [

20]/appreciated”, we will use the subjective perception of each respondent, without claiming an exhaustive definition, with the same perspective as Brad Olsen in his editorial: “the goal is to illuminate teacher quality—what it is and how it’s captured, measured and promoted—with an eye towards ways that it engages the whole structure of teacher recruitment (and) evaluation” [

33].

If we associate the terminology “good teacher” with “teacher quality”, it is important to mention the definition that “teacher quality refers to all teacher-related characteristics that produce favourable educational outcomes such as student performance on standardised tests or supervisor ratings” [

27], and this leads us to the next filter—the one that focuses on the impact on students.

In addition to reformatting and redefining learning for the exam, this approach would also raise the problem of the quality of the assessors, whether we are talking about inspectors or markers, because their own way of acquiring information has an impact on the way they assess what they see or read, and not everyone is able to understand and differentiate innovation and originality in wording from mere precious expressions lacking in sound content.

The proposal to formulate synthesis topics is a solution as long as there are not already books and other resources that encourage the candidate to learn the synthesis by heart for a formula that is sure to succeed in the exam but is totally useless for future work in the classroom.

The discussion is much more complex and can be deepened by assessing differences in perceptions of assessment by comparing groups of respondents according to the independent variables mentioned initially to see if there are not noticeable differences in the needs and perceptions of those who teach according to the age category of their students or at least according to the profile of the subject taught (e.g., Social vs. STEM). A limitation of the research is the lack of the differentiation of the answers based on gender or even the year in which each respondent took the tenure exam because their perception also might be influenced by the examination topics. Another limitation is inherent in the Romanian language and its many meanings that cannot be profoundly translated and understood identically, even if we did our best in translating the questionnaire.