Abstract

Blended learning has become immensely integrated in contemporary times owing to the emergence of COVID-19. Consequently, it was seen as an effective approach to meet the accelerated demands of the diverse student population in universities and colleges. The rapid progress of the online world has made it essential to switch from face-to-face to online space. However, first-year Science Foundation students appear to encounter challenges using various learning platforms. While the demands of the online spectrum have changed due to the advent of COVID-19, this paper aimed to assess student participation and experience while teaching online on numerous platforms including Microsoft Teams, Google Teams, Moodle, and WhatsApp. The qualitative approach was employed to obtain descriptive data which was later quantified. Semi-structured questionnaires were used to conduct interviews with a total of 120 Science Foundation students at the University of Venda in the academic year 2021 to obtain the students’ online learning experiences. The findings of this study showed that due to the variety of online platforms used in the various modules, the students are unable to interact with the lecturers since the online learning platforms were quite new and tricky to navigate through. In addition, the researchers tried to fill the gap and implement strategies for effectively engaging pedagogy on online platforms. Students’ experiences were related to poor network connectivity, computer illiteracy, difficulty adapting to the Moodle platform, intermittent home learning environment, lack of interaction, and heavy workload. There is a need for a holistic understanding of how technology has transformed the teaching and training landscape to enable academics and students to stay relevant in a rapidly evolving educational landscape.

1. Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic led the University of Venda to transition first-level students from classroom teaching to online lessons. The students are seldom confronted with online learning challenges, which impede them from participating on the numerous platforms for online engagement. In addition, face-to-face teaching has received strong support from students at all levels and has been viewed as more effective than online interaction as the students seem to experience challenges. Some studies by Liu and Long [1] argued that face-to-face learning is irreplaceable and the cornerstone of any learning institution, even if the current discourse and technological revolution require the use of eLearning.

Students are increasingly demanding online access and universities are working to meet these requirements [2]. Subsequently, access to education reduces costs, improves the cost-effectiveness of education, and maintains the competitive advantage in recruiting students in higher education. A major challenge for online learning is the one-size-fits-all approach, which does not do justice to student differences [3]. Students are unique; therefore, their learning abilities are also different. When online lectures use the same approach, it can affect the effectiveness of online learning. For a different student body, different approaches should be integrated to achieve maximum learning.

In addition, Orlando and Attard [4] argue that online learning depends on the technologies used at the time and the curriculum that is being taught. In the same way, Jacobs [5] states that it is imperative to recognise the type of student enrolled in the course to design a suitable interaction system that enables the students not only to learn but also to learn by themselves pampering online learning. Online exams were introduced after Higher Education Minister Blade Nzimande announced amid the COVID-19 third wave and level 4 lockdown, universities across the country would pause face-to-face and physical exams. Consequently, it was an effective approach to meet the accelerated demands of the diverse student population in universities and colleges.

The rapid progress of the online world has made it essential to switch from face-to-face to online space. The Science Foundation programme in the Faculty of Science, Engineering, and Agriculture has six modules, namely English, Physics, Biology, Chemistry, Information Technology, and Mathematics, in which students who do not meet the requirements for mainstream enrolment are admitted to the extended programme. However, first-year Science Foundation students seem to encounter challenges using various learning platforms. While the demands of the online spectrum have changed due to the advent of COVID-19.

2. Purpose of the Study

The purpose of the study is to assess student participation and experience while attending online classes on numerous platforms.

3. Research Questions

What challenges were encountered by the first-year students on the online learning platforms?

How did it impact their learning and participation in the online learning space?

4. Theoretical Framework

Constructivism and the New Technology

The design for online blended learning is based on practical and theoretical perspectives from constructivism, situated learning, and Merrill’s [6] first principles of teaching. There is also a growing body of evidence that more traditional Class lessons can be enhanced with web-based multimedia and communication tools. For example, Bell and Garofalo [7] found that conceptualised integration using computer-based multimedia was effective in improving elementary students’ achievement in science and mathematics. The fact that technology can play an integral role in the constructivist learning environment is increasingly recognized by all actors in higher education. Several researchers agree that technology plays a crucial role in enabling constructivist approaches.

The focus of both constructivism and technology is on creating engaging and collaborative learning environments. Lunenburg [8] argues that constructivism and the integration of computer technology into the curriculum offer real prospects for improvement in the performance of all students in the core subjects. Proponents of constructivism try to show connections between constructivist teaching and learning strategies and educational technologies in the classroom [9]. The wealth of technology enables academics and e-learning to provide a richer and more engaging learning environment [10].

In technology-enabled collaborative learning environments, the multiple forms of synchronous and asynchronous communication tools help facilitate dialogue, a key element in socio-constructivist principle-based pedagogy, where the emphasis is on the joint construction of knowledge within a community of students. In relation to this study, constructivism as the dynamic theoretical framework enables both students and lecturers to adopt the new normal and enhance their engagements.

5. Material and Methods

Research Approach

The qualitative approach was used to address the objective of this paper. Lundi [11] and Mohajan [12] articulated that the qualitative approaches are the most applicable qualitative research method due to the systematic nature of the approach in providing answers to “what” and “why” research questions.

More specifically, an explanatory consecutive approach which requires the exploration of qualitative data followed by the descriptive and numerical type of data was employed.

In this paper, a qualitative method was employed, whereby the survey questionnaire (Supplementary Material) was later quantified to determine the degree of the problem and predominant of these issues and challenges from students’ responses. Miles [13] and Kuper [14] attest to the significance of employing a qualitative data collection approach as being immensely effective in study fields such as education, sociology, and anthropology. Most significantly, the utilisation momentum of this approach has been gained in the health professions and education fields. This method was used to obtain descriptive and numerical data from the respondents, and this included frequency counts and percentages to determine the most common experiences and challenges related to the questions. The sample included a total of 240 first-year Science Foundation students of the Faculty of Science, Engineering, and Agriculture at the University of Venda of the Limpopo Province, South Africa. Students were requested to participate in the study simply by completing the questionnaire which comprised questions that addressed their online learning experiences. Issues related to the availability of gadgets, types of platforms, and challenges encountered during online learning.

However, only 120 out of the universal population of 240 students responded to the survey questionnaire and this survey was aimed at assessing student participation and experiences while attending online lectures on various platforms. The data collected for this study were analysed using thematic coding, with researchers going through the responses carefully to classify the data into topics and further understand the online learning experiences of Science Foundation students at a rural university. Prior to the conduction of interviews, researchers clearly explained the purpose and objective of the study and furthermore, students were requested to sign the consent forms. Participation in this study was voluntary, and students were at liberty to withdraw from the research at any time without any consequences. Ethical approval was not required for this study because the participants were students in this programme and informed consent was sought for all participants prior to their participation. Moreover, the researchers were the lecturers in the department. While this was conducted as action research through the survey establish efficient maximisation of online learning platforms. Consequently, this study was conducted as part of monitoring and identifying the at-risk students, with special reference to the online learning challenges and concerns that have exacerbated the poor participation and performance thereof.

6. Results

Socio-demographical information of the respondents (Table 1).

Table 1.

Sociodemographic information of the respondents.

Out of the 120 respondents, 74% were females and only 26% were males. Respondents were distributed into three age classes 17–20, 21–23, and 24–26. A total of 89% of the respondents belonged to the age group 17–20. Prior to their enrolment at the university, most of the respondents (75%) studied at rural-based secondary schools. Of the 120 respondents, 60%were funded by the National Student Financial Aid Scheme (NSFAS) and 40% were self-funded. A total of 41% of students resided at their homes whereas 36% and 23% of students resided at the university residence and private residence, respectively.

Based on the results of this study, there were seven major challenges that students encountered while their lecturers facilitated online lessons on different platforms.

Distractions and challenges that prevent the students’ participation.

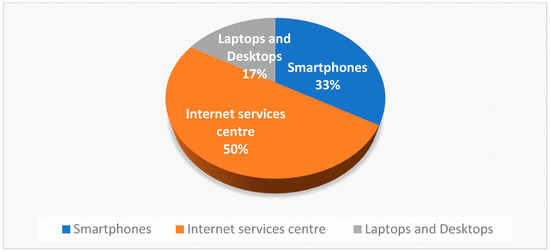

‘The gadgets and devices that students used to type in their work’ in Figure 1 shows the contribution of devices and gadgets in the completion of their projects. The 40 students used their mobile phones to type their work while 60 students sent their work to the typists at the internet café. The other 20 students used laptops and desktop computers to type their work. Most students used the Internet café to work on their assessments and type their academic work owing to the scarcity of resources and infrastructure to cater to the demands of the diverse student population with respect to blended learning in the emergence of the COVID-19 pandemic. This is the conundrum that needs meticulous attention to mitigate the student’s challenges and predicaments and afford the students effective teaching and learning space. The availability of gadgets such as mobile cell phones is of utmost importance in capacitating students to perform and engage in various academic activities in their own spaces [15].

Figure 1.

The gadgets and devices that students use to type in their work.

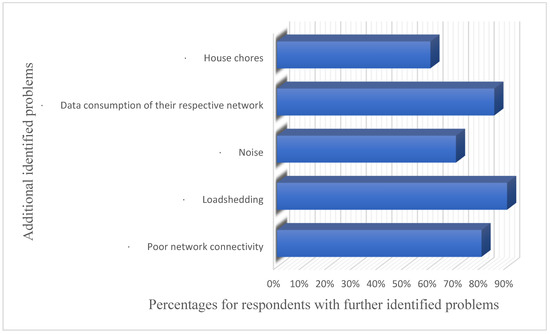

Figure 2 titled ‘The students’ major problems with online learning platforms’ conveys that the students were mainly affected by load-shedding and data consumption of their respective networks. Subsequently, these were observed as difficult conundrums since the problems were far beyond their control. In addition, the other dominant problems were noise and poor network connectivity in the different places which were quite unmanageable at all costs and online learning was interrupted owing to such experiences. Furthermore, the least problem was house chores that affected female students as they were not afforded privileges to participate in their respective online classes and as such these students had to skip some sessions at some stages. Nevertheless, hindering factors towards the effectiveness of eLearning are not limited to the availability of conducive gadgets. Other problems such as poor network connectivity, load shedding, noise in the residences, data consumption rate during engagements, and house chores emerged from this study.

Figure 2.

The students’ major problems with online learning.

6.1. The Intermittent Home Learning Environment

In Figure 2 titled ‘The students’ major problems with online learning’ displays the major problems encountered by the students which impeded them from actively participating in the online space. The findings of this study indicated that human distractions were a challenge for students. The students feel uncomfortable attending their classes in the online space due to inevitable distractions at home. The students indicated that they are unable to participate in their online classes owing to the noise level at their respective homes. Learning is not conducive at their respective homes as their parents fail to understand that they are attending classes in an online space. Most of the female students skipped many classes as their parents expected them to do house chores.

6.2. Heavy Workload

Most students were worried about the workload regarding the assessments and sessions that the lecturers facilitated daily. The students mostly failed to submit their assessments within the stipulated deadlines. Some students complained that the workload is quite unbearable, and they are unable to cope with the pace since the platform has many features which are not easy to understand. The students are still struggling to adapt to the learning environment.

6.3. Lack of Interaction between Lecturers and Students

The online space compelled students who do not understand the operation of these platforms to maneuverer through the learning for them to interact with their lecturers. However, the challenges encountered by the students impede them from interacting with their lecturers during online classes. In addition, the students found it difficult to engage with their lecturers. The lecturers failed to identify the students’ passivity in space. The time factor is a serious predicament in the sense that students do not have sufficient time to interact with the lecturers.

6.4. Poor Network Connection

In terms of connectivity, students were concerned that their network connections were poor in their respective homes. According to Adedoyin and Soykan [16], the feasibility and effectiveness of online learning are entirely dependent on technological devices and internet connections. Problems encompassed within the accessibility of these aspects become hindrances to the accomplishment of knowledgeable student learning. Students complained that load shedding was affecting network connections when they were supposed to be taking certain courses. Students said that in some cases they skipped certain online courses due to poor network connectivity and that some of their instructors are unable to record the sessions for future reference by those who missed the course. It has been strongly suggested that the network affects many online courses, either the faculty or students, as the various networks are quite unstable in some places. Network towers impacted negatively on the student’s participation due to the lack of a cell network enabler site.

6.5. Data Consumption Rate

Most of the students complained about the data consumption rate and they indicated that the online classes are consuming their data at a higher rate and the university supplied them with unreliable mobile data. While the data is quite expensive on their respective network providers when they are compelled to purchase the data for online classes. Some students indicated that they do not receive data from the university for online learning while others responded that they do receive data, but it is quite not enough for all the sessions in a month.

6.6. Computer Illiteracy

The results of this paper showed that most rural-based university students lack the basic computer knowledge and skills necessary to be a student in higher education. Students complained that they cannot write their work according to the requirements of the academic assessment. In addition, some students reported lacking knowledge of basic Internet and related technology software and systems. The other students reported that they were unable to handle the following aspects: changing the look and feel of their work, editing text, and checking spelling, and their main problem is using computerised technology in all assigned tasks.

In addition, the students stated that they were unprepared to use computers and did not understand how to use them. The students had no contact with computer-related tasks and were not equipped with writing skills. Students further stated that they do not have access to university computers to enter their academic ratings as they use their cell phones to type in assignments.

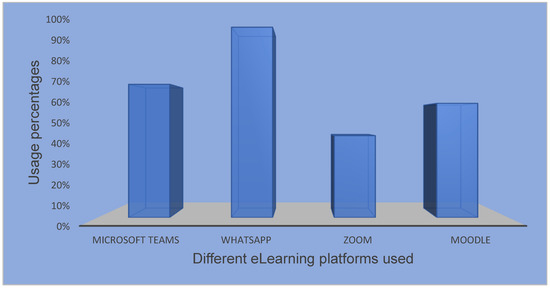

6.7. Difficulty Adapting to Moodle

The students are mainly not thoroughly trained to navigate the Moodle platforms. The students skipped the Moodle training sessions where they would have been equipped and imbued with knowledge and skills regarding the operation of the learning management systems. The students were less prepared to attend their classes in the online space. Some students indicated that they were not exposed to technological devices prior to their tertiary studies. The students indicated that their lecturers hardly used the Moodle platform when facilitating online classes. The respondents indicated that the lecturers use WhatsApp often and this may be a result of the difficulties to navigate through the Moodle LMS.

‘The platforms used during online classes’ in Figure 3 shows that lecturers often used WhatsApp to accommodate students who were largely affected by the poor connectivity in their respective spaces during the online sessions While Moodle was the mandatory platform for uploading and updating summative and formative assessments and course content for easier accessibility to the students at a later time. Based on the frequent usage of WhatsApp and seldom use of Moodle and other platforms portrays that technological skills are major conundrums to both students and academics.

Figure 3.

The Platforms Used During Online Classes.

7. Discussion

The survey was conducted to understand the challenges and online experiences of first-year students during the first semester of online classes in the academic year 2021. Based on the findings of this study, there were seven major challenges that students encountered while their lecturers facilitated online lessons on different platforms. These challenges encompassed; the intermittent home learning environment, the heavy workload that was quite unbearable, unfamiliarity with online learning, lack of interaction between lecturers and students, poor network connectivity, data consumption rate, computer illiteracy, and difficulty adapting to Moodle. Moreover, the major findings emerged that the students felt uncomfortable attending their classes in the online space due to inevitable distractions at home. Some students complained that the workload is quite unbearable and they are unable to cope with the pace since the platform has many features which are not easy to understand. Moreover, students indicated that they had to skip classes at times due to poor network connectivity and that some of the instructors were unable to record sessions for future reference by those who missed the session. In addition, the students stated that they were unprepared to use computers and did not understand how to use them. On the other hand, Muca, Cavallini, and Odore, et al. [17] reported that 54.5% to 90.6% of students use portable electronic devices such as smartphones, laptops, and tablets for learning purposes. This widespread use of portable devices might be explained by the fact that they are easily accessible, allow quick access to information, and are less expensive than non-portable devices.

This paper reports that most students used the Internet café to work on their assessments and type their academic work owing to the scarcity of resources and infrastructure to cater to the demands of the diverse student population for blended learning in the emergence of the COVID-19 pandemic. This is the conundrum that needs meticulous attention to mitigate the student’s challenges and predicaments and afford the students effective teaching and learning space. The findings of this study are validated by the study of Borisova et al. [15], who posited the availability of gadgets such as mobile cell phones is of utmost importance in capacitating students to perform and engage in various academic activities in their own spaces. Nevertheless, hindering factors towards the effectiveness of eLearning are not limited to the availability of conducive gadgets [18,19,20]. Other problems such as poor network connectivity, load shedding, noise in the residences, data consumption rate during engagements, and house chores emerged from this study as the common challenges encountered during the transition of the COVID-19 pandemic.

There exists a need for researchers in educational technology to direct research advancement toward the development of alternative assessment approaches that will be devoid of cheating and plagiarism with adequate attention to the recommendations of Feldman for unbiased and equitable assessment systems for the future reoccurrence of such pandemic since education system is vulnerable to external problems of this kind.

7.1. The Intermittent Home Learning Environment

The findings of this study indicated that human distractions were a challenge for students. The students reported that they felt uncomfortable attending their classes in the online space due to inevitable distractions at home. The students further indicated that they are unable to participate in their online classes owing to the noise level at their respective homes. Learning is not conducive at their respective homes as their parents fail to understand that they are attending classes in the online space. This is congruent with the study conducted by Ngeze [21] and Saini and Goel [22] indicated that the online learning space can be cumbersome for students who reside with their family and friends since the disturbance is quite unavoidable in such situations. Most of the female students skipped many classes as their parents expected them to do house chores. Several studies recently explored the challenges encountered in the home learning environment; however, Adedoyin and Soykan [16] reported that the home learning environment has been a concern for many students as the parents and guardians concluded that these students were freely available to be assigned any task while they are home. This resonates with the current concerns expressed in this study as these challenges affected the students in their completion and submission of Take-Home assessments. Moreover, it was a common and recurring problem for most students that they mostly performed poorly in their assessments owing to circumstances beyond their control.

7.2. Heavy Workload

The findings of the current study elucidated most students were worried about the workload regarding the assessments and sessions that the lecturers facilitate daily. The students mostly failed to submit their assessments within the stipulated deadlines. Some students complained that the workload is quite unbearable, and they are unable to cope with the pace since the platform has many features which are not easy to understand. The students are still struggling to adapt to the learning environment. This study is consistent with the findings of the study conducted by Mwalumbwe [23] articulated that using learning analytics to predict students’ performance in Moodle LMS. Moreover, mitigation strategies to be ought to be established to enable ease of access and success to students. The findings of this study are consistent with a plethora of studies conducted in this area, along that this study is heavily influenced by Adedoyin and Soykan [16] elucidated that the first-year level students were unable to cope with the workload in their respective modules since they are still adapting to the culture of the university and attempting to master basic computer skills to perform the assigned projects effectively and efficiently.

7.3. Lack of Interaction between Lecturers and Students

The online space compelled students who do not understand the operation of these platforms. Moreover, the challenges encountered by the students impede them from interacting with their lecturers during online classes. The students found it difficult to engage with their lecturers. The lecturers failed to identify the students’ passivity in space. This study is validated by the findings of Beldarain [9] that elucidated fostering students’ interaction and collaboration on the online learning platform is quite cumbersome. Subsequently, the time factor is a serious predicament in the sense that students do not have sufficient time to interact with the lecturers. The retrospect of studies resonates with the present study’s findings which encompasses the recent study of Adedoyin and Soykan [16] stated that the students feel uncomfortable consulting their respective lecturers even posing questions during the online classes. This effect has been widely reported in the literature as this persists to be a major problem in the Higher Education sector in the transition of the COVID-19 crisis. Moreover, this observation was reported in the studies conducted by Decuypere, Grimaldi, and Landri [19] and Abdellatif [20] who elucidate thatdigital education exerts challenges for students without experiences in the integration of technology in the learning space which brings decontextualisation and alienation thereof.

7.4. Poor Network Connection

In terms of connectivity, students were concerned that their network connections were poor in their respective homes. In concurrence, this study is consistent with Adedoyin and Soykan [16], as they reported that the feasibility and effectiveness of online learning are entirely dependent on technological devices and internet connections. Problems encompassed within the accessibility of these aspects become hindrances to the accomplishment of knowledgeable student learning. Students complained that load shedding was affecting network connections when they were supposed to be taking certain courses. Students stated that in some cases they skipped certain online courses due to poor network connectivity and that some of their instructors are unable to record the sessions for future reference by those who missed the course. It has been constantly reported that the network affects many online courses, either the faculty or students, as the various networks are quite unstable in some places. In line with the study conducted by Gillet-swan [3] articulated that the network challenges become difficult conundrums for online lectures. Network towers impacted negatively on the student’s participation due to the lack of a cell network enabler site.

7.5. Data Consumption Rate

The results of this paper reported that most of the students complained about the data consumption rate, and they indicated that the online classes are consuming their data at a higher rate and the university supplied them with unreliable mobile data. While the data bundles are quite expensive on their respective network providers when they are compelled to purchase the data for online classes. The findings of this study are corroborated by the study of Kurata [24] and on the learnability in the LMS since the connection is dependable on the bundles which are quite expensive for students. Consequently, the data consumption rate of students’ respective subscriber’s mobile necessitated them to skip their classes owing to such conundrums. Some students who were residing in private residences indicated that they do not receive data from the university for online learning while others responded that those who were funded by the National Student Financial Scheme do receive data; however, it is quite not enough to participate in all the sessions in a month. Collaboratively, the findings of this study are in support of the notion and challenges outlined in the study of van Riesen, Gijlers, and Anjewierden [25], who reported similar results in the report of challenges encountered by the students outlined among others the data bundles appeared to be insufficient for most of the online classes owing to the duration of different sessions facilitated by their respective lecturers and consumption rate for the platforms used in different classes that each lecturer facilitates.

7.6. Computer Illiteracy

The findings of this paper showed that most rural-based university students lack the basic computer knowledge and skills necessary to be a student in higher education. Students complained that they cannot write their work according to the requirements of the academic assessment. In addition, some students reported lacking knowledge of basic Internet and related technology software and systems. The other students reported that they were unable to handle the following aspects: changing the look and feel of their work, editing text, and checking spelling, and their main problem is using computerised technology in all assigned tasks.

In addition, the students stated that they were unprepared to use computers and did not understand how to use them. The students had no privilege to do computer-related tasks and were not equipped with writing skills. Students further indicated that they do not have access to university computers to enter their academic ratings as they use their cell phones to type in assignments. In congruence with the studies conducted by Mtebe [26], Saini and Goel [22] and Gómez-García and Soto-Varela, et al. [27] articulated that the computer application technology in the learning space has been observed as a major problem since the students are unable to use computers to complete their assigned tasks. The findings of this study are consistent with the report from different institutions of higher learning articulated and elaborated on the first-year level students commonly struggle to execute computer application tasks owing to their incompetence in the utilisation of computer basic skills. The conclusion can be drawn that the students’ inadequate knowledge of computers compromises their performance in the academic tasks assigned to them. To address digital competence as an emergency remote teaching problem, Mokganya and Zitha [28] suggested that educational institutions need not design a separate platform for learning digital skills, but it should be embedded in the teaching and learning process of all subjects, while Dong, Jong, and King [29] added that learners must be motivated to get digital competency for them to remain relevant in modernity. Moreover, this is a critical skill that ought to be internalised among first-year students in the institution in the 21st century.

7.7. Difficulty Adapting to Moodle

The findings of this study exhibited that the students are mainly not thoroughly trained to navigate the Moodle platforms. The students skipped the Moodle training sessions where they would have been equipped and imbued with knowledge and skills regarding the operation of the learning management systems [27]. The students were less prepared to attend their classes in the online space. Some students indicated that they were not exposed to technological devices before their tertiary studies. The lecturers indicated that they often used WhatsApp to accommodate students who were largely affected by the poor connectivity in their respective spaces during the online sessions and while Moodle was the mandatory platform for uploading and updating summative and formative assessments and course content for easier accessibility to the students at a later time [30,31]. Based on the frequent usage of WhatsApp and seldom use of Moodle and other platforms portray that technical skills are major conundrums to both students and academics. The previous studies conducted on this subject validate the findings of the present study, Orlando and Attar [4] as the lecturers perceived themselves as digital immigrants tend to ignore the significant impact of blended learning while the students did not have exposure to computer application technology before their university studies.

8. Conclusions

In conclusion, the major conundrums in the integration of blended learning were that the students felt uncomfortable attending their classes in the online space due to inevitable distractions at home. Moreover, these students were unable to participate in their online classes owing to the noise level at their respective homes. While most students were worried about the workload regarding assessments and lessons that the lecturers facilitated on a regular basis. Some of the students failed to submit their assessments to the stipulated deadlines. Unfortunately, some of these students were unable to cope with the pace of the online learning platform since the platform has many features which are not easy to understand. Students found it difficult to engage with the lecturers. Consequently, these major challenges were necessitated and exacerbated by the virtue of students’ previously disadvantaged schools, lack of financial support, and disturbances owing to load-shedding schedules during their online classes while for students the home learning environment was not conducive and even the absence of network towers in the remote areas where the students reside. Traditional face-to-face teaching is quite inevitable in many rural settings these days due to the inadequate knowledge of students, exposure to computer-based learning, and lack of basic internet skills. The biggest problems are hindering the integration of blended learning in the most deprived institutions as the resources required for online learning are scarce. The online courses are typically ineffective for both students and faculty because of the numerous concerns and challenges raised in the survey responses. The digital assessments were quite problematic for some students as they were expected to respond to the questions on the online space while they were unable to retrieve certain symbols and icons required in their responses to the assessments. The present study has certain limitations. The first major limitation is that the study was restricted to hundred eighty-six Science Foundation students in the entire faculty of Science, Engineering, and Agriculture. Moreover, the population does not form half of the students enrolled in the academic year 2021. The second limitation is that the sample sizes were for the rural setting which does not generalise this problem to be common with the other setting like urban areas with reasonable access to resources. The third limitation is the level of study as it included the first level group.

9. Implications and Recommendations

This study recommends the following key issues to be taken into cognisance to enhance effective and efficient engagement on the online platform and Learning Management Systems.

The lecturers should comprehend the needs of students who are enrolled in their courses to identify the at-risk students at an early stage. Training on the integration of Moodle in the classroom and minimal online presence by academics and their students should be mandatory to ensure usage and familiarity with the platform such that students understand basic usage. The financial implications are a matter of concern that must be given satisfactory attention by academic institutions to ensure the number of students inconvenienced is reduced. Moreover, there is a need for academic institutions to establish competition among students from disadvantaged backgrounds who perform outstandingly to receive special funding to enable free education. There should be an internal evaluation and thorough consideration of disadvantaged students through merit bursaries.

There is a need for a holistic understanding of how technology has transformed the teaching and training landscape to enable academics and students to stay relevant in a rapidly evolving educational landscape. Computer application technology should be introduced into the content of the first-level curriculum to provide students with basic knowledge and skills. There is a need for evaluation and monitoring of the logs and course participation. Moreover, the e-learning practitioners should establish an online weekly minimal presence among the students. Subsequently, there is a need for the establishment of good and effective compulsory training in computer literacy. The lecturers should provide a comprehensive guide that contains technical times, digital literacy guidelines, and online attendance. The lecturers should constantly record class sessions on their computers for students who could not make it to class.

It is strongly recommended that the introduction of short computer courses be incorporated into the curriculum of the first-year programmes to accommodate the accelerated demands and the diverse student body as a whole. In addition, the students must be well-trained in navigating the Moodle LMS. Significantly, there is a need for further research to unpack the other issues that remain cumbersome in the integration of blended learning which encompasses; future studies should explore the lecturers’ digital competence as a pathway to address the misconceptions and assumptions regarding their competence. Moreover, there is a need to analyse the effectiveness of online learning and teaching with students who attended Computer Application Technology subject in their secondary level.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/educsci13070704/s1.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, I.Z. and M.G.M.; methodology, M.G.M.; software, T.M.; validation, I.Z. and M.G.M.; formal analysis, I.Z.; investigation, M.G.M.; resources, I.Z.; data curation, I.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, I.Z.; writing—review and editing, I.Z.; visualization, M.G.M.; supervision, I.Z.; project administration, I.Z.; funding acquisition, I.Z., M.G.M. and T.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

All data supporting this manuscript have been made available. All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Davies, M. Critical thinking and the disciplines reconsidered. High. Educ. Res. Dev. 2013, 32, 529–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofmann, D.W. Internet-Based Distance Learning in Higher Education. Tech Dir. 2002, 62, 28–32. [Google Scholar]

- Gillett-Swan, J. The Challenges of Online Learning Supporting and Engaging the Isolated Learner. J. Learn. Des. 2017, 10, 20–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orlando, D.; Attar, E. Digital natives come of age: The reality of today’s early career teachers using mobile devices to teach mathematics. Math. Educ. Res. J. 2015, 28, 107–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobs, D. Teaching Responsibility through Physical Activity; Human Kinetics: Champaign, IL, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Merrill, J. Re: Language-Independent Functions-as-Trees Representation. 2002. Available online: http://gcc.gnu.org/ml/2002-07/msg00890.html (accessed on 20 November 2021).

- Bell, R.; Garofalo, J. (Eds.) Curriculum Series: Science Units for Grades 9–12; International Society for Technology in Education (ISTE): Eugene, OR, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Lunenburg, F.C. Early Childhood Education Programs Can Make a Difference in Academic, Economic, and Social Arenas. Education 1998, 120, 519. [Google Scholar]

- Beldarain, Y. Distance Education Trends: Integrating new technologies to foster student interaction and collaboration. Distance Educ. 2006, 27, 139–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duffy, T.; Cunningham, D. Constructivism: Implications for the Design and Delivery of Instruction. In Handbook of Research on Educational Communications and Technology; Jonassen, D., Ed.; Simon & Schuster: New York, NY, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Lund, T. Combining qualitative and quantitative approaches: Some arguments for mixed methods research. Scand. J. Edu. Res. 2012, 56, 155–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohajan, H.K. Qualitative research methodology in social sciences and related subjects. J. Econ. Dev. Environ. People 2018, 7, 23–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miles, B.; Huberman, A.; Saldana, J. Qualitative Data Analysis, 3rd ed.; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Kuper, A.; Reeves, S.; Levinson, W. An introduction to reading and appraising qualitative research. BMJ 2008, 337, 404–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borisova, O.V.; Vasbieva, D.G.; Frolova, V.B.; Merzlikina, E.M. Using Gadgets in Teaching Students Majoring in Economics. IEJME 2016, 11, 2483–2491. [Google Scholar]

- Adedoyin, O.B.; Soykan, E. COVID-19 pandemic and online learning: The challenges and opportunities. Interact. Learn. Environ. 2020, 31, 863–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muca, E.; Cavallini, D.; Odore, R.; Baratta, M.; Bergero, D.; Valle, E. Are Veterinary Students Using Technologies and Online Learning Resources for Didactic Training? A Mini-Meta Analysis. Educ. Sci. 2022, 12, 573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, J. Digital transformation in higher education: Critiquing the five-year development plans (2016–2020) of 75 Chinese universities. Distance Educ. 2019, 40, 515–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Decuypere, M.; Grimaldi, E.; Landri, P. Introduction: Critical studies of digital education platforms. Crit. Stud. Educ. 2021, 62, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdellatif, I. Towards A Novel Approach for Designing Smart Classrooms. In Proceedings of the IEEE 2nd International Conference on Information and Computer Technologies, Kahului, HI, USA, 14–16 March 2019; pp. 280–284. [Google Scholar]

- Ngeze, L.V. Learning management systems in higher learning institutions in Tanzania: Analysis of students’ attitudes and challenges towards the use of UDOM LMS in teaching and learning at the University of Dodoma. Int. J. Comput. Appl. 2016, 136, 9–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saini, M.K.; Goel, N. How Smart Are Smart Classrooms? A Review of Smart Classroom Technologies. ACM Comput. Surv. 2019, 52, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mwalumbwe, I.; Mtebe, J.S. Using learning analytics to predict students’ performance in Moodle learning management system: A case of Mbeya University of Science and Technology. Electron. J. Inf. Syst. Dev. Ctries. 2017, 79, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurata, Y.B.; Bano, R.M.L.P.; Marcelo, M.C.T. Effectiveness of learning management system application in the learnability of tertiary students in an undergraduate engineering program in the Philippines. In Advances in Human Factors in Training, Education, and Learning Sciences; Andre, T., Ed.; AHFE 2017; Advances in Intelligent Systems and Computing; Springer: Cham, Switzerland; Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2018; Volume 596, pp. 142–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Riesen, S.A.; Gijlers, H.; Anjewierden, A.A.; de Jong, T. The influence of prior knowledge on the effectiveness of guided experiment design. Interact. Learn. Environ. 2019, 30, 17–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mtebe, J. Learning management system success: Increasing learning management system usage in higher education in sub-Saharan Africa. Int. J. Educ. Dev. Using Inf. Commun. Technol. 2015, 11, 51–64. [Google Scholar]

- Gómez-García, M.; Soto-Varela, R.; Morón-Marchena, J.A.; del Pino-Espejo, M.J. Using mobile devices for educational purposes in compulsory secondary education to improve student’s learning achievements. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mokganya, G.; Zitha, I. February. Assessment of First-Year Students’ Prior Knowledge as a Pathway to Student Success: A Biology Based Case. In The Focus Conference (TFC 2022); Atlantis Press: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2023; pp. 233–246. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, A.; Jong, M.S.Y.; King, R.B. How does prior knowledge influence learning engagement? The mediating roles of cognitive load and help-seeking. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 591203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Solovei, V.; Horban, Y.; Samborska, O.; Yarova, I.; Melnychenko, I. Digital transformation of education in the context of the realities of the information society: Problems, prospects. Rev. Eduweb. 2023, 17, 225–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwet, M.; Prinsloo, P. The ‘smart’ classroom: A new frontier in the age of the smart university. Teach. High. Educ. 2020, 25, 510–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).