Abstract

Educational reforms and educational policy changes have favored the learning of English as a foreign language (EFL) in public education. Empirical research has examined how EFL specialist teachers in urban public schools perceive these changes or the extent to which they adopt a new curriculum. Nonetheless, the new EFL policies have also had an impact on rural schools where generalist teachers are forced to teach English along with other areas of the curriculum. In this context, little research has explored teachers’ perceptions and appropriation of ongoing curricular changes. The present study explored this issue among generalist rural secondary school teachers in the southeast of Mexico. To this end, an explanatory sequential mixed method was adopted with a sample of 216 generalist teachers. During the quantitative phase, the participants completed two Likert scale questionnaires. Then, a semi-structured interview was conducted with a sub-sample of participants who obtained high (n = 7) or low (n = 7) results in the perceptions and appropriation questionnaires. The statistical analyses showed a weak but positive correlation between perceptions and appropriation. The qualitative data provide some insights that explain the weakness of the correlation.

1. Introduction

Many countries around the world have experienced significant changes due to the impact of supranational financial, environmental, and sociopolitical challenges. These challenges, alongside the imperialism of English as a global and useful international language, have led many countries to undergo major educational reforms that sanction the learning of English as a second/foreign language (EFL) in public education [1,2]. In these reforms, curricular changes constitute the main axis of educational development and, in the case of EFL education, instantiate the renewal of the day-to-day teaching and learning practices [3].

Through educational reforms, public educational systems require teachers to adopt instructional models that aim to help learners develop particular and general EFL competencies [4]. However, the implementation of reforms is not straightforward. Their success greatly depends on teachers’ willingness to accept, adapt, and implement a curricular change; nonetheless, these actions demand a critical reorganization of well-established teaching habits [4]. Some authors affirm that the critical reorganization of teaching habits is partly influenced by the positive or negative perceptions that teachers hold with respect to the educational reforms [1,5]. Moreover, for educational changes to occur, teachers need to appropriate the educational practices outlined in the new curriculum. This effect implies that, vis-à-vis the educational reforms, teachers need to become educational policy enactment agents who perceive and appropriate curricular changes [6].

The constructs of teachers’ perception and appropriation of EFL curricular changes have received attention in previous second language research [5]. Nonetheless, they have been separately examined by a handful of studies; often, these studies have been conducted with EFL specialist teachers who deliver language instruction across different levels of public education in urban areas [7]. It should be noted though that the educational policies have not only sanctioned the learning of English in urban areas. They have also made the learning of English obligatory in rural settings where there is a lack of specialists in English language teaching or other areas of the curriculum [2]. Therefore, in rural schools, one generalist teacher is compelled to teach all areas of the public school curriculum, including English [8,9,10,11], to the same group throughout the school day.

In the context of the current study, the national curriculum of the public education of Mexico states that English needs to be taught in the three grades of secondary education. Vis-à-vis this policy, in urban schools, EFL education is often delivered by language specialists. In rural areas, however, generalist teachers are obligated to teach English in addition to the other areas of the secondary school curriculum. The professional profile of this type of educator often includes undergraduate studies in general education or pedagogy. In their schools, they deliver EFL instruction without formal language teacher education and minimal language competencies [12,13]. In addition to their teaching duties, generalist teachers mentor learners, manage their school, and plan school logistics [14,15].

Based on the aforementioned issues, the objective of the present study was to explore the perceptions of generalist teachers about current EFL curricular changes and the appropriation of the recommended teaching practices. To this end, a sequential explanatory mixed-methods study was carried out; it addresses three research questions: How do generalist teachers perceive curricular changes for the teaching of English in rural education? What is the level of appropriation of curricular changes in their English language teaching practice? What are the factors that influence their perception and appropriation of curricular changes for English language teaching?

2. Background to the Study

In this section, the central constructs of the perception and appropriation of EFL curricular reforms are first presented. Then, the section comes to an end by discussing the need to explore the interplay between these two constructs among generalist teachers who deliver EFL education in public rural schools.

2.1. Teachers’ Perception of EFL Curricular Reforms

From a psychological viewpoint, the construct of perception refers to understanding how a context is perceived. In the field of education, perceptions are conceived psychological notions that encompass, for instance, thoughts, emotions, behavior, beliefs, and cognition [16,17,18]. In second language research, teachers’ perception is conceptualized as a cognitive process that is based on what a teacher feels, creates, thinks, and understands and how a teacher behaves with respect to a particular aspect of language education—in this case, a curricular change [5,16,19]. This cognitive process is nurtured by a set of external and internal factors [18]. While the former includes school policies and the teachers’ social, cultural, and professional background [19], the latter spans ideologies, knowledge, and attitudes [2,5,19]. Teacher’s perceptions about curricular changes develop from internal ideologies that emerge from observation, knowledge, and discernment of (new) teaching approaches and curricular guidelines [20]. The construct of teachers’ perception builds upon a wide array of factors, but theoretical and empirical researchers agree upon the dimensions of opinions, beliefs, behaviors, and emotions. During curricular changes, these dimensions allow teachers to interpret educational policies and teaching demands [5,21,22].

Opinions constitute a set of subjective interpretations that teachers develop in a specific context or toward an issue [23]. In language teaching, opinions are considered positive or negative constructions that teachers build on, taking a stance in favor of or against the English teaching philosophy [5,24], curricular guidelines, teaching strategies, content, or other elements of the language educational reforms [5]. Beliefs are assumptions that emerge from knowledge [25]. In second language teaching, beliefs [6,19] are part of teachers’ cognition [5] and encompass multiple aspects of language education, such as pedagogical processes, learning processes, and evaluation processes [18,25]. Teachers prioritize beliefs of language teaching and learning based on their educational environment and their professional background experiences [5]. Behaviors are complex processes, as they imply that cognition transfers into actions [5]. In turn, these actions are known as pedagogical practices that teachers consider relevant for the teaching and learning process [26]. The behaviors that teachers display could be connected to all aspects of the curricular changes, for example, language policies, guidelines, content, teaching practices’ impact on students, and other aspects of the curriculum that are tightly connected to the classroom [5,27]. Emotions rely on different conceptual psychosocial or psychoeducational conditions. [17]. In language teaching education, teachers experience positive or negative emotions, for example, excitement, joy, motivation, dissatisfaction, fear, and burnout, as a result of their practice or curricular reforms [18,28].

2.2. Teachers’ Appropriation of EFL Teaching Practices

The construct of appropriation refers to teachers’ adoption of curricular changes [29]. Appropriation is achieved when teachers understand the new curricular demands and reorient their practice accordingly [3]. Depending on the level of adoption, five levels of teachers’ appropriation of curricular changes can be identified [30]: (1) absence; (2) superficial; (3) surface; (4) conceptual underpinning; and (5) engagement. Two relevant aspects of the appropriation encompass regular teaching practices and evaluation processes [30].

The teaching practices are connected to the development of a lesson; thus, this teaching process is supported by the bases of curricular, disciplinary, or pedagogical knowledge that teachers need for the implementation of learning activities in the classroom [29]. However, a teaching practice could be limited when teachers are non-specialists or lack teacher training [31]. Teaching practices are framed by experiences on learning and teaching and are complemented by teachers’ professional development [32]. In the context of curricular reforms, a teaching practice is connected to teaching activities that are built upon curricular guidelines. As for the evaluation dimension, it is a complex aspect of appropriation. It goes beyond the adoption of measurement and testing, which implies systematic measures of a specific competence. Instead, evaluation encompasses judgments of the learning progress and the achievement of the learners within the curriculum [2,26]. Moreover, it provides teachers with valuable information about the effectiveness of their teaching practice, their commitment to curricular demands [33], the appropriateness of the material, and the role of the learning context, among other elements [2]. In English Second Language (ESL) or EFL, teachers often conduct evaluations using a language framework and guidelines about the teaching, learning, and evaluation processes in their curriculum [34].

2.3. The Interphase of Perception and Appropriation

In the field of second language education, perception is associated with behaviors, beliefs, thoughts, and emotions tightly connected with the process of learning or teaching a new language [5,18,35]. Appropriation, however, encompasses the adoption, adaptation, and interpretation of new curricular changes [30,36]. Some studies have examined these two constructs separately [35], while other studies have explored a possible interphase among them.

In this regard, some studies from Libya, Iran, Argentina, and other countries have examined how language teachers perceive and react to curricular changes [37,38]. These studies have examined teachers’ perceptions of curricular changes using a qualitative approach through interviews, written reflections, and observational data. Their findings show a negative perception of curricular changes. In the same way, other qualitative studies in China, Vietnam, and Libya have focused on the construct of appropriation and analyzed how language teachers implemented or appropriated the language curricular reforms to innovate in their practices [39,40,41]. The qualitative interview and observation data from these studies indicate that the participants showed difficulties in adopting the curricular changes.

While the aforementioned studies have explored these constructs separately, empirical evidence has revealed a harmonious interphase [41,42], which supports teachers’ understanding of the curricular changes and reorientation of their pedagogical practices [3,8,22]. In Hong Kong, for instance, using a mixed methods approach, a pioneer study [42] analyzed how English teachers from public schools appropriated the curriculum. The interview and observational data showed that teachers implement the curriculum based on their training and experiences due to a constant interaction with stakeholders. In turn, the quantitative results from an attitude Likert scale revealed a positive tendency to the challenge of language curricular innovation [42]. In Taiwan, a research study [7] collected quantitative and qualitative data to obtain a holistic appreciation of the appropriation of curricular changes. The quantitative findings revealed that teachers were aware of and showed positive perceptions. However, the qualitative data revealed a lack of appropriation of the language curricular guidelines [7]. This finding is in line with those from a qualitative study in Argentina, where Banegas (2016) found a remarkable incongruence between teachers’ practices and curricular guidelines [38].

The above evidence provides valuable insights into the perception and appropriation of curricular changes among EFL teacher specialists who work in urban public schools. Nonetheless, there is a growing interest in exploring the perceptions and appropriation of language curricular changes among teachers who are neither language teachers nor specialists in teaching English [2]. This interest emerges from the fact that, in a rural context, there is often a lack of language specialists to deliver second language instruction [2,15]. Thus, non-specialized teachers are obligated to teach English using the educational policies established by the reforms [15]. These teachers are often generalist teachers [2] or educators whose teacher education focuses on the teaching of subject matter from different areas of the public curriculum (i.e., first language literacy, geography, mathematics, etc.) [2]. In their rural schools, they often need to deal with overcrowded school groups, a lack of teaching resources, and the teaching of multiple school grades in the same classroom. Their students have agricultural responsibilities that limit their time to study and cause absenteeism [12]. With respect to the teaching of English, generalist teachers often have very low language proficiency levels and have not attended language teacher training. This fact leads them to implement EFL tasks based on their own language learning experience [2].

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Research Design

Based on the aforementioned issues, the present study was conducted using an explanatory sequential mixed methods design [43] to answer three research questions:

- How do generalist teachers perceive curricular changes for the teaching of English in public rural education?

- What is the level of appropriation of the ELT curricular guidelines?

- What are the factors that contribute to their perception and appropriation of the ELT curricular guidelines?

The first and second research questions were answered during a quantitative phase using a descriptive design [44]. In this phase, three instruments were administered to generalist secondary school teachers using non-probabilistic sampling: a survey and two Likert scale questionnaires. The first Likert scale questionnaire was created considering four dimensions of teachers’ perception: opinions, beliefs, pedagogical practices, and emotions. The second Likert scale questionnaire was created considering two dimensions of appropriation: teaching practice and evaluation. All of these dimensions were conceptualized and operationalized based on the literature reviewed in the previous section. Furthermore, the construct, content, and ecological validity and reliability of the questionnaires were verified. In turn, the quantitative data allowed us to test the following hypothesis:

H1.

The perceptions of generalist school teachers, about ongoing curricular changes in English language learning and teaching, can have an impact on the appropriation of the ELT practices that are sanctioned by public education reforms.

The third research question was answered during a qualitative phase, using a multiple-case design. During this phase, two subsamples of participants were selected, using their responses from the quantitative instruments [45]. The selected participants [46] completed a semi-structured interview [47], where they elaborated upon their answers in the quantitative instruments. The interview data helped us explore the following research assumption:

Different factors underpin the relationship between teachers’ perceptions and appropriation of curricular changes for English language teaching.

3.2. Context and Participants

In Mexico, secondary education is mandatory and can be completed at public schools in urban or rural areas [15]. The urban and rural schools follow the same national curriculum and EFL teaching guidelines [15]. All students need to complete three hours of EFL instruction per week [2,15]. Currently, the three grades of secondary education work with the 2017 curriculum [46]. This curriculum has undergone different reforms (i.e., 2017, 2011, 2006, 1993) over the last 30 years [15,48]. In terms of EFL learning, the reforms aim to favor a transition from a structure-based to communicative approach. According to the curriculum, English should be seen not as the object of study, but as a means of communication [2,15]. The EFL teaching guidelines are based on the Common European Framework of Language Reference and the National English Program [48]. While the language content and curricular guidelines are the same across all school types [15], the implementation of EFL teaching is different in urban and rural schools.

In urban areas, public secondary education is usually delivered at general and technical schools. In rural areas, secondary education is mostly delivered at telesecondary schools. In general and technical secondary schools, each area of the curriculum is taught by a content specialist. In the case of English, the lessons are delivered by language teachers who move from classroom to classroom across the three grades of secondary education. In the telesecondary schools, however, the teaching conditions are completely different. In these schools, a generalist teacher works with the same group throughout the school year and teaches all of the curricular areas: first-language literacy, arts, history, sciences, mathematics, and English [2]. To deliver the EFL lessons, the generalist teachers should project a 15-min video-recorded EFL lesson, taught by an EFL teacher. The National Ministry of Education broadcasts the EFL lessons nationwide through satellite TV or the Internet [15]. Then, the generalist teacher needs to build a 45-minute lesson based on the video recording [24,48]. In order to implement this lesson, the generalist teacher needs to follow up on the TV program content, adhere to the EFL teaching guidelines in the curriculum, create the necessary learning tasks, provide feedback, and evaluate students’ learning [48]. In the absence of language training, these teachers implement individual initiatives to meet the EFL curricular demands, reduce the level of learner attrition, and compensate for their language deficiencies through the use of web resources [2].

3.3. Participants

The present study was conducted in the southeast of Mexico, where the majority of learners complete secondary education in the rural areas of the state of Tabasco. In this state, telesecondary schools have an approximate population of 50,715 learners. This population is served by approximately 2262 generalist teachers, 60 percent of whom are female teachers and 40 percent of whom are male teachers. The teachers are distributed in 459 telesecondary schools across 17 municipalities, which are clustered in 5 geopolitical regions.

3.4. Sample

Due to substantial differences in teacher profiles, teaching conditions, and school organization in rural areas, the participant selection was based on sampling criteria that have been used in previous research for the homogenization of schools’ and teachers’ conditions in this context [6]. The first condition was geographical proximity. Thus, the participating teachers were located in the central geopolitical region of the state and their schools were close to rural villages that could be reached by car or boat. In terms of teaching conditions, the participants’ schools needed a minimum of two groups per grade. Based on these two conditions, 29 telesecondary schools were selected. Finally, to homogenize the knowledge of the school curriculum among the participants, the generalist teachers needed at least five years of experience in the telesecondary school system, to have had more than one year of experience at their current school, and were currently teaching one school grade only. Furthermore, the participants were excluded if they held administrative appointments (e.g., school district directors, school principals, school coordinators, etc.).

To gain access to the selected schools and participants, a consent letter was summitted to the telesecondary school department of the Ministry of Education of the state. The department answered with an official acceptance letter, granting access to the selected schools. In each school, a meeting was held with the school administrators and teachers to invite them to participate in the research. In this meeting, the objective, implementation of instruments, and ethical principles were presented. In turn, only 216 generalist teachers agreed to participate in the research and signed a consent letter. The survey data showed a balanced distribution of the participants between first (34%), second (35%), and third school grades (31%). These participants teach students whose age ranges between 12 and 15 years old [42], and English language proficiency is quite low.

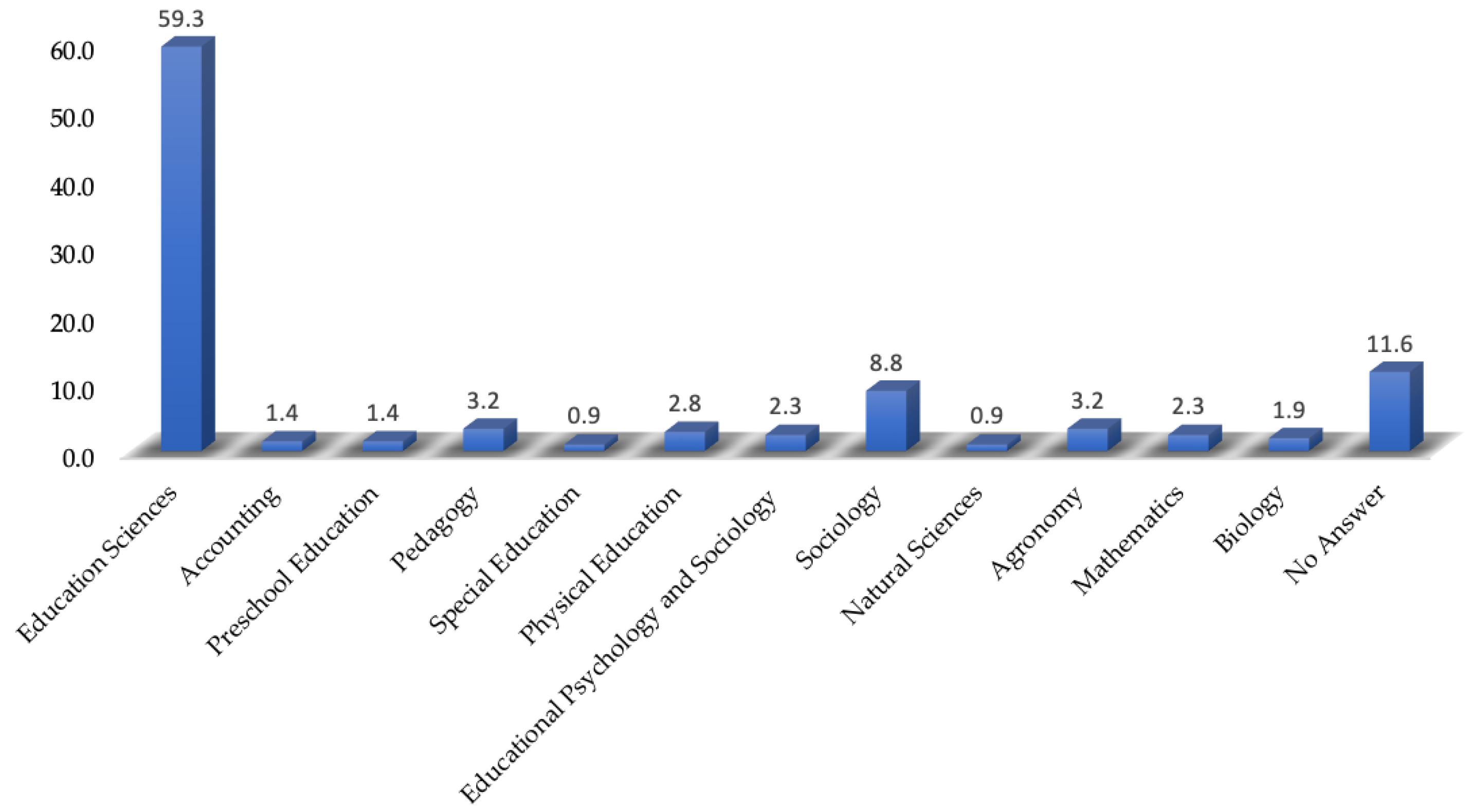

In terms of professional background, the majority of the participants held an undergraduate degree in education (see Figure 1). Moreover, the survey data revealed that some participants (37%) had a master’s degree, and a few of them (3%) held a PhD in their discipline. Likewise, the survey data showed that 8% of the generalist teachers had been abroad for pleasure, and only a few of them had done so for academic purposes.

Figure 1.

Bachelor’s degrees of the generalist teacher population.

For the qualitative component, two subsamples of teachers were selected using z-scores [49,50,51]. These subsamples represented extreme-case [52] teachers who showed a positive or negative pattern of answers in both the perception and appropriation Likert scale questionnaires [51]. The participants in the first subsample held at least one z-score above the group mean [53] in terms of perceptions and appropriation. This meant that their perception and appropriation scores were statistically higher in comparison to their peers. The participants in the second subsample held at least one z-score below the group mean in terms of perceptions and appropriation. This meant that their perception and appropriation scores were lower in comparison to those of other teachers. Out of the 216 teachers who voluntarily completed the quantitative instruments, the z-score procedure allowed us to select 14 teachers that represented extreme cases [52] and consented to participate in an interview. It should be noted though that a larger subsample was considered for the interview. However, most of them clearly stated their objection to be interviewed.

Based on these selection criteria, the participants in Table 1 and Table 2 were interviewed. They were from 13 schools. Their schools were located in remote rural areas of five municipalities.

Table 1.

Participant subsample with high perception and appropriation scores.

Table 2.

Participant subsample with low perception and appropriation scores.

Samuel had worked for 23 years in the telesecondary system. He had a BA in education. He reported that he had not taken any ELT training and had never received information about the national English program. He indicated adapting his own EFL teaching techniques and material according to the students’ level.

Grecia indicated having worked in the system for 17 years. She had a BA in education, a specialization in teaching Spanish, and an MA in education. She reported participating in conferences to learn about the 2017 curriculum but implemented the 2011 curriculum instead. She indicated that she was struggling with teaching English.

Alex had worked in the telesecondary system for 23 years. He had a BA in sociology. He reported having difficulties with English and not receiving training to teach English in telesecondary schools. He said he was using the 2016 English syllabus and books of the 2006 curriculum due to a lack of knowledge of the 2017 curriculum.

Jonas had worked for 18 years in the telesecondary system. He had a BA in social sciences. He indicated receiving information and participating in a conference to learn about the 2017 curriculum. Moreover, he had received information about EFL learning and teaching from the Ministry of Education. He indicated having difficulty teaching English; therefore, he had taken private English lessons to prepare his EFL lessons. He reported working with the 2006 curriculum and materials and using dictionaries.

Tana, who reported having a BA in education, had worked in the system for 16 years. She affirmed using the 2006 and 2011 curricula and books. She had travelled abroad, specifically to the United States. Nonetheless, she reported having difficulty when teaching English due to lack of EFL teacher training; therefore, she used online translators during her classes.

German had a BA in pedagogy. He had worked in the telesecondary system for 27 years and had information about the 2017 curriculum but had not participated in conferences. He reported having difficulty when teaching English. He indicated using the 2011 curriculum and books.

Addy had a BA in education. She had worked in the telesecondary system for 13 years. She reported not receiving materials about the 2017 curriculum. Moreover, she had not received information or training to teach English in telesecondary schools. Similar to other teachers, she indicated having difficulty teaching English. She reported using the 2006 curriculum, a dictionary, and a translator to teach English.

The second subsample of teachers had lower perception and appropriation scores, as their questionnaire data placed them at least one z-score below the group mean. Table 2 shows their pseudonyms and personal and professional data. This table indicates that this subsample also included seven participants, whose age varied from 35 to 55 years old. Moreover, their teaching experience in telesecondary schools ranged from 5 to 27 years.

Willy had 27 years of experience in the telesecondary system. He had two undergraduate degrees: one in social sciences and one in pedagogy. Moreover, he indicated having little information about the 2017 curriculum and did not have information about the national English program. Thus, he reported implementing the 2011 and 2017 curricula. He indicated having difficulties when teaching English.

Carmen, with a BA and PhD in education, had worked in the telesecondary system for 9 years. He indicated not having information or participating in a conference about the 2017 curriculum. Moreover, he reported having neither knowledge of the national English program nor having had support for teaching English in telesecondary schools; he used translators to teach English due to language proficiency issues.

Cando held two undergraduate degrees, one in physical education and one in telesecondary education. He had worked in the telesecondary system for 22 years. He reported a lack of information about the 2017 curriculum and had not attended ELT workshops. Thus, he indicated using the 2011 curriculum. He reported taking private English lessons to prepare for his English classes.

Nicole had a BA in social sciences. She had worked in rural secondary schools for 22 years, and she had little information about the 2017 curriculum; thus, she had organized a study group to learn about the new curriculum. She had little information about EFL teaching courses offered by the Ministry of Education. She affirmed having low proficiency in English. Therefore, she had paid for private English lessons. In turn, she reported working with the 2006 curriculum and books.

Natalia had one BA in education and one in elementary education. She had 5 years of experience in the telesecondary system. She had taken courses on the 2017 curriculum. Nonetheless, she specified that she was using the books that were based on the 2006 curriculum. She indicated not having had support from the Ministry of Education for teaching English. Moreover, she reported having difficulties teaching English.

Maya knew neither the 2017 curriculum nor the national English program; thus, she was using the 2011 curriculum. She had worked for 20 years in the telesecondary system. She had a BA in education. She had difficulties teaching English and used a translator during her English classes.

Liz had worked in telesecondary schools for 19 years. She had a BA and MA in education. She reported using the 2006 curriculum because she had received neither materials of the 2017 curriculum nor training about the national English program. Similar to other teachers, she had paid for private English lessons.

3.5. Quantitative Instruments

In the quantitative phase, a survey, a Likert scale questionnaire for perceptions and a Likert scale questionnaire for appropriation were administered. These instruments emerged from the literature review and were constructed under the principles of the classical testing theory [53,54,55]. Moreover, the design of the perception and the appropriation Likert scale questionnaires considered different methodological criteria: the nature of the scale, the unidimensionality, the univocity of items, [53], and the semantic direction (positive or negative) of the items. Likewise, content, construct, and ecological validity were checked to verify the central construct as well as the dimensions and their pertinence [50]. Further, the consistency and accuracy of the collected data were verified through reliability procedures.

3.5.1. Survey Design

The purpose of the survey was to explore the generalist teachers’ knowledge of language curricular changes. This instrument considered six categories or sections that included close-ended, open-ended, and multiple-choice questions [44,54,55]. The participants’ answers were analyzed using frequency counts [50,56]. In total, the survey included 31 items that were grouped into six sections. Section 1 elicited sociodemographic, academic, and experience abroad information using seven items. Section 2 elicited information about their knowledge of the public education system employing three items. Section 3 elicited information about professional development and knowledge of the 2017 curricular changes using four items. Section 4 focused on their ELT professional development considering five items. Section 5 elicited information about the implementation of ELT lessons and their EFL proficiency using nine items. Section 6 elicited information about the implementation of the ELT curriculum in their teaching using six items.

3.5.2. Design of the Likert Scale Questionnaires

The second instrument consisted of an available published and validated Likert scale questionnaire that explores generalist teachers’ perceptions about EFL curricular changes [18]. This instrument aimed at identifying the generalist teachers’ position about their knowledge, belief, thought, behavior, and emotions about curricular changes [50,55]. It included four dimensions and a four-degree agreement scale [51,55] to identify the participant position (negative or positive) for each dimension of the constructs of interest, which were explained in the background to the study section. The first dimension, opinions, tapped into their thoughts about curricular changes using seven items. The second section, beliefs, focused on what generalist teachers believed about the language curricular changes using five items. The third dimension, pedagogical practices, elicited information about behaviors that align with the language curriculum through nine items. The fourth dimension, emotion, included seven items about what teachers feel about the ELT curricular changes. All items relied on the methodological criteria for the use of ordinal variables and differential gradients of opinion [56,57,58]. Hence, a 4-degree agreement scale was implemented [56,58]. Each of the scale’s options was assigned a numerical value: strongly agree = 4 points, agree = 3 points, disagree = 2 points, and strongly disagree = 1 point [24,58]. The instrument did not include a neutral point [58] to avoid confusing participants [56,58,59]. The absence of a neutral point pushed the respondents to indicate a positive or negative judgement [24,54] about the ELT curricular changes.

The third quantitative instrument identified the position of participants in regard to the two dimensions of the appropriation of curricular guidelines through items using ordinal scales [59]. Through the items, the occurrence of the recommended teaching practice and an evaluation of learning were verified. All items of the appropriation Likert scale questionnaire were based on the literature of appropriation included in the background to the study section. This Likert scale appropriation questionnaire, considered two dimensions—teaching practice using 18 items and the evaluation of learning—using 16 items. These dimensions were conceptualized and operationalized using the definitions presented in the literature review. This instrument registered the frequencies of factual information related to both dimensions through a differential gradient scale of frequency. Each gradient was assigned a numerical value: very often = 4 points, often = 3 points, rarely = 2 points, and never = 1 point [50,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60]. Based on this characteristic, the instrument was treated with an additive property [24,59].

3.6. Qualitative Instrument

For the qualitative phase, a semi-structured interview [61] was designed to expand the participants’ answers obtained through the perception and appropriation Likert questionnaires. In turn, a trustworthiness verification process was considered using the epistemological principles of qualitative research [52]. The interview included a series of open-ended questions for each dimension of the Likert scale questionnaires. For the exploration of perception, the interview considered three questions for the dimension of opinions. For the dimension of beliefs, four questions were prepared. Regarding the dimension of pedagogical practices, three questions were considered. Then, for the emotion dimension, two questions were asked. Likewise, to follow up on the participants’ answers in the appropriation questionnaire, the interview included six questions for the teaching practice dimension. Finally, for the evaluation of the learning dimension, three questions were asked. During the interviews, in addition to the pre-set group of prompts, personalized questions were asked. These questions allowed for a deeper exploration of the constructs of interest for each participant. Upon completion of the interview, the researchers thanked the participants for their contribution to the present study.

3.7. Quantitative Instruments’ Validity and Reliability Procedures

For the quantitative instruments, content, construct, and ecological validity were considered [50,55]. As for reliability, the stability and internal consistency of the Likert scale questionnaires were independently tested for each dimension.

3.7.1. Validity Procedures

The survey was subject to ecological validity only. To this end, the survey was administered to a group of generalist teachers who had knowledge about the language curricular changes. These participants commented on the appropriateness of the questions and suggested changes that were incorporated in the final version of the survey.

In the Likert scale questionnaires of perception and appropriation, content and construct validity were checked [24]. For content validity [50], the items of each dimension were created considering the literature reviewed. Following this procedure, four groups of items were developed for the perception questionnaire and two groups of items for the appropriation questionnaire. Then, with the use of expert judgement procedures, each group of items was analyzed by a group of researchers in the field of second language teaching. These judges were provided with the definitions of the two constructs and their dimensions. Then, they made comments on the congruence between the items and the scale, the congruence among the items, and the pertinence of the items within each dimension. With this procedure, the unidimensionality of the items in all dimensions was verified [51,52]. Likewise, ecological validity was checked using a subsample of eight generalist teachers who assessed the relevance of the items.

During the design of a Likert scale questionnaire, construct validity is fundamental because it allows the researchers to identify the dimensions of the construct under observation. When the items are not created with a set of dimensions of a construct in mind, the items are subject to exploratory factor analyses. These analyses group the items into factors that can be interpreted by the researchers [51]. However, when the researchers have a clear and warranted theoretical basis for each of the dimensions of interest, construct validity can be verified using other procedures. First, the groups of items are subject to content validity. Once the judges validate the conceptual interdependence of the items and their adherence to the dimensions of the construct, the correlation coefficient between the group of items is verified through Cronbach alpha analyses [51]. These analyses are run separately for each of the group of items. Then, the relationship between the dimensions of the construct is checked through convergent validity [50]. In order to test convergent validity, correlation analyses are performed between the dimensions of the construct. In the current study, since the items for each dimension were created independently, construct validity was not verified through exploratory factor analyses. Instead, it was verified through content validity, Cronbach alpha analyses for each group of items, and correlation analyses between the dimensions of each construct (see [62], for the use of these procedures for the verification of construct validity).

3.7.2. Reliability Procedures

To check reliability, two parallel forms [12] of the perception and appropriation questionnaires were simultaneously administered to two independent groups of generalist teachers. Both forms included the same items, but in reverse order. Then, the statistical software SPSS v.25 was used to run Mann–Whitney tests to identify differences between the results that were obtained from the test forms, item by item. The differences were analyzed using an alpha of 0.05. A p greater than 0.05 assured that both versions collected similar data [51].

The stability and internal consistency of the Likert scale questionnaires were independently tested for each dimension. To this end, a Cronbach’s alpha greater than 0.80 would confirm the internal consistency of each dimension. Then, the corrected correlation coefficient of each item was checked. Only items with a coefficient greater than 0.3 were retained. Finally, the interdependence between the questionnaire dimensions was explored using a Spearman correlation test with an alpha of 0.05 [51]. Then, the correlation strength was identified [63] as weak (0.20 < < 0.39), moderate (0.40 < < 0.59), or strong > 0.60).

3.7.3. Validity and Reliability Results: Perception Questionnaire

For the perception questionnaire, the Mann–Whitney analyses showed that the answers to the items of the dimensions of opinion and beliefs were similar across the questionnaire versions, as all items obtained a p > 0.05. Therefore, all items in dimensions 1 and 2 were retained for the analysis.

For dimension 3, pedagogical practice, item 1 yielded a significant difference between questionnaire versions. This implied that this item would elicit different answers depending on the version; therefore, it was excluded from future analyses. For dimension 4, emotion, a significant difference between test versions was obtained for items 4, 5, and 7; thus, they were excluded.

The internal consistency analyses yielded a favorable Cronbach’s alpha value for dimensions 1 (α = 0.926), 2 (α = 0.806), and 3 (α = 0.747). Moreover, the correlation coefficient analyses yielded a value higher than 0.3 for the items that were retained for dimensions 1, 2, and 3. Nonetheless, dimension 4, emotions, yielded an internal consistency alpha value of 0.696; therefore, this dimension was excluded from future analyses. Table 3 summarizes the validity and reliability results, presenting the dimensions and number of items of the perception questionnaire that were retained for this study.

Table 3.

Items retained for the perception questionnaire after the validity and reliability tests.

In order to test convergent validity, correlation analyses were run on the dimensions of the perception questionnaire using the Spearman test, as the data were not normally distributed. The correlation between the retained dimensions of the perception questionnaire yielded a weak but significant positive correlation between dimension 1, opinion, and dimension 2, beliefs (p = 0.014; = 0.165), and between dimension 2, beliefs, and dimension 3, pedagogical practice (p < 0.001; = 0.255). Nonetheless, the Spearman test showed a lack of significant correlation between dimension 1, opinion, and pedagogical practice (p = 0.298).

3.7.4. Validity and Reliability Results: Appropriation Questionnaire

Regarding the appropriation questionnaire, the Mann–Whitney analyses of dimension 1, teaching practices, indicated that items 1, 6, and 9 elicited different answer patterns between versions. Therefore, these items were excluded from future analyses. In dimension 2, evaluation, the nonparametric analysis results showed that all items had a p-value higher than 0.05. Consequently, all items were retained.

During the reliability analyses, the internal consistency of dimension 1, teaching practices, achieved a Cronbach’s alpha value of α = 0.904, and dimension 2, evaluation, achieved a Cronbach’s alpha value of α = 0.907. Moreover, the coefficient correlation analysis of all the items for dimensions 1 and yielded a value higher than 0.3. In light of these results, all items were retained for future analyses. Table 4 summarizes the validity and reliability results, presenting the dimensions and number of items that were retained for the study.

Table 4.

Items retained for the appropriation questionnaire after the validity and reliability tests.

3.8. Qualitative Instrument Validation Procedures

Regarding the validity and reliability of the qualitative instrument, the interviews were transcribed using word processing software. Moreover, the transcripts were verified to assure the verbatim transcription of 14 interviews. Then, all transcripts were entered into Atlas.ti version 8.4.5. A cross-case thematic analysis [61] was implemented with the 14 informants’ transcripts to identify emerging themes [52]. First, common themes were identified using two analysis cycles [61]. The first cycle focused on the identification of themes connected to the research questions. The second cycle focused on reorganizing and reducing categories and subcategories. This process analyzed excerpts about the perceptions of curricular changes and the appropriation of new ELT pedagogical practices.

4. Results

4.1. Quantitative Results: Perception Questionnaire

In order to identify the type of perceptions that teachers hold about the curricular reforms, frequency analyses were run on the items in each of the three remaining dimensions of the questionnaire. In these analyses, every item was treated independently to identify positive or negative perceptions of participants. Table 5 shows the distribution of participants across the possible Likert scale choices.

Table 5.

Distribution of answers in dimension 1, opinions about the new educational model, in the perception questionnaire.

For dimension 1, opinions on the new curriculum, the teachers tended to take a negative position. For example, in item 1, the majority of the generalist teachers indicated that the pedagogical principles in the 2017 educational curriculum for English language teaching did not favor learning effectively in secondary education. Further, in item 2, a high number of teachers considered that the suggested strategies for teaching the English language in the 2017 educational model were not suitable for students in telesecondary schools. In item 4, more than a half of the participants agreed that the suggested strategies for teaching English in the 2017 educational curriculum could not be easily adapted by teachers in telesecondary schools. In item 5, the majority of the participants indicated that the amount of thematic content in English hardly allowed generalist teachers to properly cover the curricular content with their groups. However, in item 7, a large number of participants considered that the teaching strategies they used help them to teach English as required by the 2017 educational model (see Table 5).

In dimension 2, beliefs about teaching English, the majority of generalist teachers indicated for items 1, 3, 4, and 5 that the parents, colleagues, principals, and leaders in the educational systems did not influence their beliefs about learning English; nonetheless, they believed that their students’ opinions played a key role in their teaching (see Table 6).

Table 6.

Distribution of answers in dimension 2, beliefs about the new educational model, in the perception questionnaire.

For dimension 3, pedagogical practice, the results in Table 7 show that generalist teachers’ practices were not influenced by their coworkers or the curricular materials (items, 2, 7, and 8). The majority of the teachers tended to positively react to item 3; more than half of the teachers agreed that the recommended English material for telesecondary education had a positive influence when they taught English. Further, they considered that their language proficiency and their students contributed to what they do in the classroom (items 4 and 5). Moreover, their practices were nurtured by their previous language learning and experience and their learners’ expectations (items 6 and 9).

Table 7.

Distribution of answers in dimension 3, pedagogical practice, in the perception questionnaire.

4.2. Quantitative Results: Appropriation Questionnaire

In order to identify the level of appropriation of curricular changes, frequency analyses were run on the items in each of the two dimensions of the questionnaire. In these analyses, every item was treated independently to identify positive or negative appropriation patterns among the participants. Table 8 shows the distribution of participants across the possible Likert scale choices.

Table 8.

Distribution of answers in dimension 1, teaching practice, in the appropriation questionnaire.

In dimension 1, teaching practice, the responses to most of the items (5, 7, 8, 11, and 12) in Table 8 indicated that the generalist teachers had a high level of appropriation of teaching practice, as the largest number of participants opted for the high frequency level. The participants indicated that they often implemented music, sports, movies, games, and other activities to favor the use of English using their learning experiences. Nonetheless, items 10, 14, and 18 showed that just less than one half of teachers, from 42% to 49%, rarely implemented speaking activities and did not consider the teaching of linguistic aspects or promote the learning of the cultural aspects of English at school events. Nonetheless, as explained above, items 1, 6, and 9 revealed different answers between versions; therefore, these items were excluded.

In the analysis of the answers to the items in dimension 2, evaluation of learning, all items showed a high level of appropriation for the evaluation suggested in the curriculum. The number of participants ranged from 55% to 70% (see Table 9). The results indicated that the teachers implemented formative evaluation, where they considered different qualitative and quantitative aspects that provided evidence of their learners’ learning progress and continuous performance. Moreover, they indicated that their evaluation focused on the communication competencies that they gradually developed during the school year.

Table 9.

Distribution of answers in dimension 2, evaluation, in the appropriation questionnaire.

These generalist teachers indicated that they often analyzed the congruence of the evaluation process, evaluation material, and the students’ interaction during English lessons. Furthermore, the results show that teachers reported evaluating competences established in the curriculum that they were using. Moreover, they often evaluated their learners using continuous, permanent, and formative evaluation.

4.3. Quantitative Results: Perception and Appropriation Interphase

In order to examine the potential interphase between the two central constructs of the study, Spearman correlation analyses were run on the global scores that the participants obtained in both questionnaires. These analyses yielded a significant correlation between the results of the perception questionnaire and appropriation questionnaire (p = 0.024; = 0.153).

The analysis results indicated that this correlation was positive but weak. In other words, the analysis results suggested that as the perception of the curriculum among the participants improved, the appropriation of the recommended curricular guidelines became more systematic. Based on this statistical result, the alternative hypothesis was retained.

4.4. Qualitative Results: Interview Data

With the use of Atlas.ti software, during the qualitative analyses, 10 categories and 80 subthemes emerged during the first cycle analysis. During the second cycle, the themes were condensed into three macro-categories based on the three research questions. Table 10 shows that the condensed themes centered upon the ELT challenges, curricular transition, and training. Across the macro-categories (themes) and subthemes, the interview data pointed to different positive and negative factors that underpin the relationship between perception and appropriation.

Table 10.

Themes and subthemes in the second cycle qualitative data analyses.

On the positive side, the qualitative data revealed that some teachers tended to accept the curricular reforms. To this end, they adapted and modified the English syllabus through consensus with peers in their school board. Moreover, they indicated that although a few teachers avoided their responsibilities for teaching English, they all needed to assume the responsibility to teach English to their students in rural schools. They considered that the adaptation of the curriculum would enhance their students’ learning, as the next excerpts illustrate:

Excerpt 1 …I think that learning English for telesecondary students is complex. And yes, it may be, because students come from schools where they have not taken English lessons. Here in the telesecondary school is the first time they have English lessons. They come from elementary schools where they never studied English, so we want them to learn English, that is the reason we modify the programs to help our students.(Addy)

Excerpt 2 …to help our students we made a consensus to adapt and modify the language curriculum because when we reviewed the English material, we noticed that the contents were so complicated, I mean very complex…(Cando)

Moreover, these generalist teachers assumed that the curricular adaptations helped their students complete significant learning activities using their own context. Likewise, teachers selected material with content that helped their students learn; for example, they reused English books that they used during the implementation of previous curricula. In addition to the use of elements from the various curricula, teachers considered the use of tutorials, songs, translators, and games that helped students interact with the English language. In addition to the adaptations, teachers showed willingness toward professional development courses in order to implement the new curriculum in their telesecondary school.

Excerpt 3 I am working with the 2017 curriculum, using strategies of the 2011 syllabus. And I am working with English books from 2006 to guide me when teaching English(Carmen)

Excerpt 4 …the new curriculum is not clear to me. …but I like to do the best I can for example I use a Duolingo app, translator and I use apps for pronunciation, so I try to implement some aspects of the new curriculum. We have sung in English for example the Beatles’ songs(German)

Excerpt 5 …We know that this 2017 plan is good, everything is supposed to be planned and I think the program is good, but we as teachers…we need training on the educational tools the Ministry of Education gives us. Why? In order to improve what we do in the classroom. …they deliver the training courses online at four or five in the afternoon … and you have to be at home with your computer, paying for your internet, uploading evidence and talking, taking the class, right?(Wilbert)

Nonetheless, on the negative side, it was observed that teachers had many limitations when implementing the 2017 curriculum. The transition and challenge of implementing the 2017 curriculum seemed to bring about issues that were not acknowledged in current curricular reforms. The following excerpts illustrate some of these issues.

Excerpt 6. I think that the new curriculum is complex to be implemented in my English lessons, because, on one side I have little knowledge about it. I mean, the language demands of the 2017 curriculum imply a high level of English proficiency that the students in our context don’t have; that is why I can’t implement the curriculum at all(Lizbeth)

The previous excerpt indicates that the students’ language proficiency was a major challenge. In addition, the teachers also acknowledged that their own proficiency was a negative factor that needed addressing. They considered that the curricular language demands did not consider the extent to which the linguistic abilities of the students and the teachers hindered the learning of English. Moreover, the personal financial implications of those demands were not accounted for, as teachers needed to defray the expenses of pedagogical and language training using their own resources.

Excerpt 7. …we received a yearlong training course from the Ministry of Education, but it did not focus on English, we are not trained in that aspect. …I like to learn English to teach it, so I pay for English training because I am interested in how to teach English(Grecia)

Nevertheless, teachers considered that the transition of the 2006, 2011, and 2017 models had had a negative impact on their English pedagogical practices. Moreover, the little knowledge they had about the 2017 model made them modify the language curriculum or in some cases reject it.

Extract 8…in fact we have not seen, we do not take into account the English subject. I mean that teaching English is not taken into account, and we did not review the current plans and programs of study in-depth. Because we were worried about what was coming with the 2017 reform. Thus, we only took a look at the English language content. We do nothing, because we were truly more concerned about our assessment(Natalia)

Extract 9 …I’ve been… how will I say? … negligent in that aspect, I don’t like the word negligent very much, but I have to accept it…(German)

Extract 10… I would love to do dialogues but I cannot speak or pronounce them, so I cannot say that I am going to have a dialogue in the English class, so I cannot do what I want to do… We are not sure of what we teach in English. That is our problem. You know, when we teach English, we are afraid of having writing, grammar, or pronunciation mistakes when we use English in the classroom. That is so alarming for us. But we do not show that in class. But I have reflected on it, so I have realized that there are teachers who do know a little but they try it. And also I think that my students don’t know English, so why should I be afraid of teaching English, right?(Addy)

The excerpts above show that the teachers experienced confusion vis-à-vis the ongoing language curricular changes. It seems that this negative behavior was embedded in their low proficiency in English and the low proficiency levels of their students. In light of these issues, they felt unable to cover the content of the curriculum and implement proper teaching English strategies. To counteract this reality, they modified and adapted the curriculum to the best of their knowledge and within their language proficiency.

4.5. Summary of Findings

The quantitative analyses yielded a significant positive correlation between opinions and appropriation; this suggests that as teachers’ perceptions became more positive, the level of appropriation increased. Nonetheless, this correlation was weak. The qualitative findings provide some insights to better understand the weakness of the correlation. For instance, the interview data indicated that the generalist teachers experienced fear when teaching their English lesson because of their English proficiency and that of their students. This proficiency issue made them feel uncomfortable regarding the teaching of the productive skills and the provision of corrective feedback. Moreover, while the teachers were aware of the existence of the 2017 curriculum, they had no training on its content and the implementation of proper language learning tasks. Therefore, they included elements of the curricula they already knew and with which they felt more comfortable.

5. Discussion

Regarding research question 11, the quantitative results show that generalist teachers had a negative opinion about the ELT curricular changes. This finding was corroborated during the interviews, where they expressed disagreement with the new curriculum. This dissatisfaction constitutes a well-known challenge for the acceptance of EFL educational reforms in other international contexts such as Libya [32,40] Taiwan [7], Vietnam [39], Turkey, and Argentina [38]. It should be noticed, though, that while the opinion of our participants is not in line with their expectations of the curriculum, their beliefs and pedagogical practices showed a positive tendency in the quantitative results (for similar results, see [3,7,17,19,29,32,41]). Nonetheless, in order to adhere to the guidelines, generalist teachers have to deal with issues such as L2 proficiency, teacher training, and pedagogical support in the same way as specialized English teachers do in rural areas [12,23].

Our qualitative and quantitative data indicate that the generalist teachers value some aspects of the curriculum and, thus, modify the content of the curriculum and use different materials. Teachers’ beliefs about what they should teach is nurtured by their students’ opinions, context, and English proficiency. Previous research has revealed that, due to border-crossing issues, the generalist teachers in Mexican rural areas make efforts to adapt the curriculum content in order to help children with immigrant parents or relatives [2]. The curricular adaptations of generalist teachers in Mexico diverge from empirical evidence in other Latin-American studies where rural teachers showed a passive engagement in teaching English [23]. Furthermore, rural teachers in other countries were found not to value the learning of English as much as Mexican rural generalist teachers do. This finding brings about questions on how the border sharing conditions between Mexico and the United States influence the perception of rural teachers on the national EFL curriculum, its demands, and its curricular guidelines.

In regard to research question 2, two appropriation dimensions were considered: teaching practices and the evaluation of learning. These dimensions explored how teachers interpret and adopt the curriculum [22,30]. The quantitative and qualitative results showed that generalist teachers exhibited a positive trend in teaching practice and evaluation process. For the appropriation of teaching practices, the questionnaire data show that the teachers adopted the new curriculum based on their students’ contextual reality. The interview data allowed us to see that the teachers mixed the teaching strategies recommended across the various curricular reforms. They often did so despite technological, pedagogical, and linguistic limitations. Nonetheless, two areas of the EFL curriculum that the teachers did not consider were oral and written production. Due to their low English proficiency, it was difficult for them to prepare fluent conversations [2], and when they implemented oral production activities, they were hesitant on the accuracy of the language they were delivering. Moreover, they felt limited in terms of the amount and type of feedback they provided.

The quantitative data revealed a high level of appropriation in terms of the evaluation recommended in the curriculum. During the interview, the teachers explained that, as recommended in the curriculum, they adhered to formative evaluation. Throughout the course, they considered the content that learners grasp and their performance in the activities. While our participants indicated adherence to the type of evaluation stated in the curriculum, a discrepancy was observed between what should be evaluated and what is evaluated. The curriculum states that EFL education should focus on the use of the target language for communicative purposes. Nonetheless, the teachers’ evaluation activities centered upon word identification, sentence making, verb conjugation, and sentence ordering. These findings instantiate that the lack of EFL proficiency and formal teacher education not only hinders the adoption of teaching practices but also affects the evaluation process, despite the willingness of generalist teachers to comply with curricular guidelines.

Regarding research question 3, although the quantitative findings confirmed the alternative hypothesis, the qualitative data provided evidence of a positive interaction and a negative interaction between teachers’ perceptions and the appropriation of curricular changes, respectively. This, in turn, can explain the weak correlation between the two constructs of interest in the study. For example, generalist teachers modify and adapt the language curriculum based on students’ needs and context. However, this modification is made using the 2006, 2011, and 2017 curricular content. Moreover, many generalist teachers develop their classes based on the 2011 curriculum and implement strategies from the 2017 syllabus and books from the 2006 model. This finding shows congruence with Park and Sung’s (2013) international research. Using interviews, these authors showed that teachers interpreted the curriculum by selecting certain content and teaching strategies during the curricular transition [64]. Moreover, Taylor and Marsden (2014) found, using qualitative and quantitative data, that teachers interpret the curricular changes based on their teaching experience and beliefs [20].

In regard to negative factors, our evidence shows that generalist teachers received little information about the 2017 curriculum. This finding is similar to that in other international [32,38,40] and national studies [2,24,65,66,67] that reveal that generalist and language specialist teachers implement the new curriculum without training. To overcome this absence of curricular knowledge, some generalist teachers pay for training in ELT and information and communication technology. Thus, they undertake professional development for the enactment of the new curricular reforms.

Another aspect that counteracts the interphase between teachers’ perception of the curricular changes and appropriation of educational practices is the discomfort that teachers feel about the language teaching demands. The teachers often feel overwhelmed by the content of the language curriculum [2]. However, this finding is not particular to generalist teachers with low proficiency levels of EFL. Some studies indicate that even generalist teachers who completed English language courses and EFL teacher training also feel overwhelmed by the EFL curriculum.

Fear is an additional issue in ELT among generalist teachers when they need to implement curricular changes. This factor could be interpreted, at the emotional level, as anxiety [28]. Our qualitative findings indicate that generalist teachers do not feel secure about how and what they teach. In the interview data, the teachers reported that they are preoccupied about how they handle critical issues, for example, social issues, such as family violence, economic resources, psychological problems, sexual violence, hunger, and agricultural responsibilities, that the curriculum does not consider for the organization of their lessons [2]. These teachers considered that these factors hinder English language teaching and learning in rural areas but are disregarded in curricular reforms. Other studies [23] showed similar results among Nicaraguan rural teachers who faced similar issues. Therefore, these findings confirm that generalist teachers struggle to implement their English classes at the emotional level. In turn, all of these eventualities keep generalist teachers in a state of emotional instability [17].

Our study provides some valuable information about the constructs of interest. For instance, our empirical evidence shows that the construct of perception is built upon different dimensions, opinions, beliefs, and pedagogical practices. Nonetheless, our findings indicate that the dimension of emotions showed a lack of stability due to a fluctuation process. Thus, while we were able to identify teacher disagreement in regard to the language curriculum, questions arise about how teachers feel teaching an aspect of the curriculum they are not ready for. Moreover, an interesting aspect of our study was that the statistical results revealed a positive correlation between perception and appropriation. Nonetheless, this correlation was weak. The qualitative evidence provided some information to have an initial idea of the factors that hinder the correlation between the two constructs. Nevertheless, we considered that a longitudinal observational classroom study might provide further information on the level of appropriation and the implementation of the curricular changes. While this type of study is desirable and valuable, researchers might encounter that only a few teachers are willing to participate in longitudinal studies due to time constraints and a fear of observation [2].

Finally, the three research questions were answered, but some methodological modifications could have helped us collect more informative data. For example, probabilistic sampling was not possible due to the geographical location of the rural schools. While the quantitative and qualitative validity procedures instantiate the internal validity of the results, the use of probabilistic sampling would be better for future research, as it could enhance the representativeness and generalizability of our findings. Finally, we consider that our qualitative instrument was not sensitive enough to facilitate a deeper exploration of the participants’ reality. Hence, other criteria should have been considered during the organization of the interview questions in order to increase the trustworthiness of the qualitative findings. Although the open-ended nature of the interview questions allowed us to go deeper into the answers of the participants, the use of personalized interviews could have elicited individual data to better understand how each participant deals with EFL education and the implementation of the new curriculum vis-à-vis the reality of their students.

6. Conclusions

Language curricular changes bring about substantial challenges for English language teaching in public education. When these changes are enforced in rural areas, generalist teachers face major challenges [2]. Nonetheless, their challenges have been particularly underestimated. Our quantitative and qualitative data showed that this kind of teacher population believes that adopting curricular content and teaching strategies could help their students learn English. Moreover, rural generalist teachers are convinced that English is essential for their students. Thus, they are willing to invest in their teaching practice and language competencies. These findings contrast with those from specialist English teachers who consider that public EFL education is of little value to their students [65,66,67]. In turn, the generalist teachers make extra effort to comply with EFL curricular demands, and their efforts need to be considered by stakeholders and policymakers. Due to their willingness to enhance the ELT process, generalist teachers could be included in mentoring projects that help them develop their ELT practice. Moreover, they could be part of collaborative projects with specialized EFL teachers. Based on the evidence from this study and other studies conducted with generalist teachers who are obligated to teach English in rural schools, policy planners should pay attention to these teachers and be willing to engage in bottom-up curricular development processes. Generalist teachers have proven to be knowledgeable about the challenges of the ELT curricular reforms. However, above all, they have provided ample evidence of commitment and engagement with the teaching of a discipline that is far beyond their own professionalization and training. Thereafter, their voice should be heard during the organization of curricular reforms and the conceptualization of the public education ELT curriculum.

Author Contributions

Both authors equally contributed during the conceptualization and realiza-tion of the study, as well as during the preparation of the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the publish version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the local Ministry of Education as shown by approval letter number 1016/2019 dated 7 May 2019.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

To obtain access to the data and instruments, please contact the authors.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the participants and the local institution for their support during the realization of the project. We regret that their names cannot be openly acknowledged due to anonymity and ethical concerns.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Nunan, D. The impact of English as a global language on educational policies and practices in the Asia-Pacific region. Tesol Q. 2003, 37, 589–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izquierdo, J.; Zúñiga, S.P.A.; Martínez, V.G. Foreign language education in rural schools: Struggles and initiatives among generalist teachers teaching English in Mexico. Stud. Second Lang. Learn. Teach. 2021, 11, 133–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, R. Appropriating national curriculum standards in classroom teaching: Experiences of novice language teachers in China. Int. J. Educ. Res. 2017, 83, 55–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaniuka, T. Toward an understanding of how teachers change during school reform: Considerations for educational leadership and school improvement. J. Educ. Chang. 2012, 13, 327–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borg, S. Teacher Cognition and Language Education. Research and Practice; Bloomsbury: New York, NY, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Cassels, J.; Freeman, R. Negotiation of language education policies guided by educators’ experiences or identity (individual): Appropriating language policy on the local level. In Negotiating Language Policies: Educators as Policymakers, 1st ed.; Menken, K., García, O., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2010; pp. 13–31. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, W.H. Teacher perceptions of teaching and learning English as a lingua franca in the expanding circle: A study of Taiwan. Engl. Today 2016, 33, 2–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ardzejewska, K.; Mcmaugh, A.; Coutts, P. Delivering the primary curriculum: The use of subject specialist and generalist teachers in NSW. Issues Educ. Res. 2010, 20, 203–219. [Google Scholar]

- Carr, W. Fear of teaching French: Challenges faced by generalist teachers. Can. Mod. Lang. Rev. 1999, 56, 155–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen-Thomas, H.; Richins, L.G. ESL mentoring for secondary rural educators: Math and science teachers become second language specialists through collaboration. Tesol J. 2015, 6, 766–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serrano, J.; Lera, A.; Contreras, O. Maestros generalistas vs especialistas: Claves y discrepancias en la reforma de la formación inicial de los maestros de primaria. Rev. Educ. 2007, 344, 247–250. [Google Scholar]

- Roldán, A.M.; Peláez Henao, O.A. Pertinencia de las políticas de enseñanza del inglés en una zona rural de Colombia: Un estudio de caso en Antioquia. Ikala Rev. Leng. Cult. 2017, 22, 121–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russo, J.; Corovic, E.; Hubbard, J.; Bobis, J.; Downton, A.; Livy, S.; Sullivan, P. Generalist Primary School Teachers’ Preferences for Becoming Subject Matter Specialists. Aust. J. Teach. Educ. 2022, 74, 38–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zein, M.S. Elementary English education in Indonesia: Policy developments, current practices, and future prospects. English Today 2017, 33, 53–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Secretaría de Educación Pública, SEP. Aprendizajes Clave para la Educación Integral, 2nd ed.; Secretaría de Educación Pública: Mexico City, Mexico, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Samdal, O.; Wold, B.; Bronis, M. Relationship between students’ perceptions of school environment, their satisfaction with school and perceived academic achievement: An international study. Sch. Eff. Sch. Improv. 1999, 10, 296–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saunders, R. The role of teacher emotions in change: Experiences, patterns and implications for professional development. J. Educ. Change 2013, 14, 303–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borg, S. Language teacher cognition: Perspectives and debates. In Second Handbook of English Language Teaching, 2nd ed.; Gao, X., Ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; Volume 1, pp. 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pajares, F. Teachers’ beliefs and educational research: Cleaning up a messy construct. Rev. Educ. Res. 1992, 62, 307–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, F.; Marsden, E. Perceptions, attitudes, and choosing to study foreign languages in England: An experimental intervention. Mod. Lang. J. 2014, 98, 902–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Hu, G. Between intended and enacted curricula: Three teachers and a mandated curricular reform in Mainland China. In Negotiating Language Policies: Educators as Policymakers, 1st ed.; Menken, K., García, O., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2010; pp. 123–142. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, C. Advancing policy makers’ expertise in evidence-use: A new approach to enhancing the role research can have in aiding educational policy development. J. Educ. Chang. 2014, 15, 19–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coelho, F.; Henze, R. English for what? Rural Nicaraguan teachers’ local responses to national educational policy. Lang. Policy 2014, 13, 145–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández, M.; Izquierdo, J. Cambios curriculares y enseñanza del inglés: Cuestionario de percepción docente. Sinéctica Rev. Electron. Educ. 2020, 54, 1–22. Available online: https://sinectica.iteso.mx/index.php/SINECTICA/article/view/1042 (accessed on 25 June 2020). [CrossRef]

- Rulison, S.R. Teachers’ Perceptions of Curricular Change. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Oklahoma, Norman, OK, USA, 2012. Available online: http://ezproxy.depaul.edu/login?url=https://search-proquest-com.ezproxy.depaul.edu/docview/1015169185?accountid=10477 (accessed on 10 November 2020).

- Niu, R.; Andrews, S. Commonalities and discrepancies in L2 teachers’ beliefs and practices about vocabulary pedagogy: A small culture perspective. Tesol J. 2012, 6, 134–154. [Google Scholar]

- Aquino, Z.S.; Izquierdo, J.; Echalaz, B. Evaluación de la práctica educativa: Una revisión de sus bases conceptuales. Rev. Actual. Investig. Educ. 2013, 13, 1–22. Available online: http://www.scielo.sa.cr/pdf/aie/v13n1/a02v13n1 (accessed on 25 June 2020).

- Oxford, R.L. Emotion as the amplifier and the primary motive: Some theories of emotion with relevance to language learning. Stud. Second Lang. Learn. Teach. 2015, 5, 371–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsang, K.; Lianjiang, J. Sociological understandings of teachers’ emotions in second language classrooms in the context of education/curricular reforms. In Emotions in Second Language Teaching: Theory, Research and Teacher Education; Martínez, J., Ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 53–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grossman, L.; Smagorinsky, P.; Valencia, S. Tools for teaching English: A theoretical framework for research on learning to teach. Am. J. Educ. 1999, 108, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peláez, O.; Usma, J. The crucial role of educational stakeholders in the appropriation of foreign language education policies: A case study. Profile 2017, 19, 121–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]