Qualifying Method-Centered Teaching Approaches through the Reflective Teaching Model for Reading Comprehension

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Method-Centered Teaching Approaches for Reading Comprehension

2.1.1. Reciprocal Teaching

2.1.2. Interactive Teaching

2.1.3. Questioning Strategy

2.2. Transformative Learning Theory

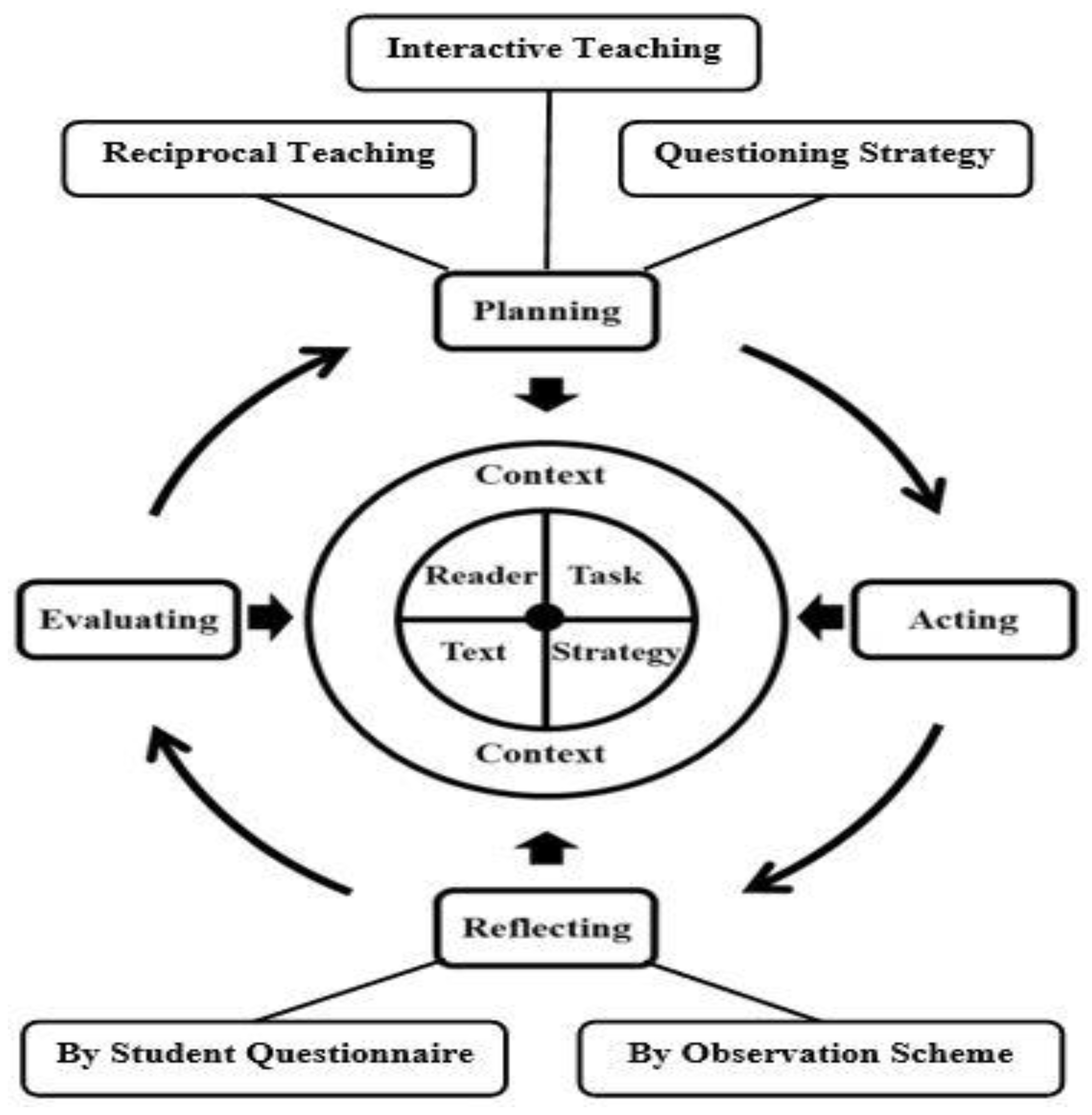

2.3. Reflective Teaching Model for Reading Comprehension

2.3.1. Reflective Teaching Process

2.3.2. Factors Influencing the Reading Event

2.4. Conceptual Framework

2.5. Uncovering the Contribution of the Current Study

2.6. Aim and Research Questions

3. Method

3.1. Participants

3.2. Instruments

3.2.1. Pre- and Post-Tests

3.2.2. Student Questionnaire

3.2.3. Observation Scheme

3.3. Procedures

3.4. Data Analysis

4. Findings

4.1. Results from the Tests

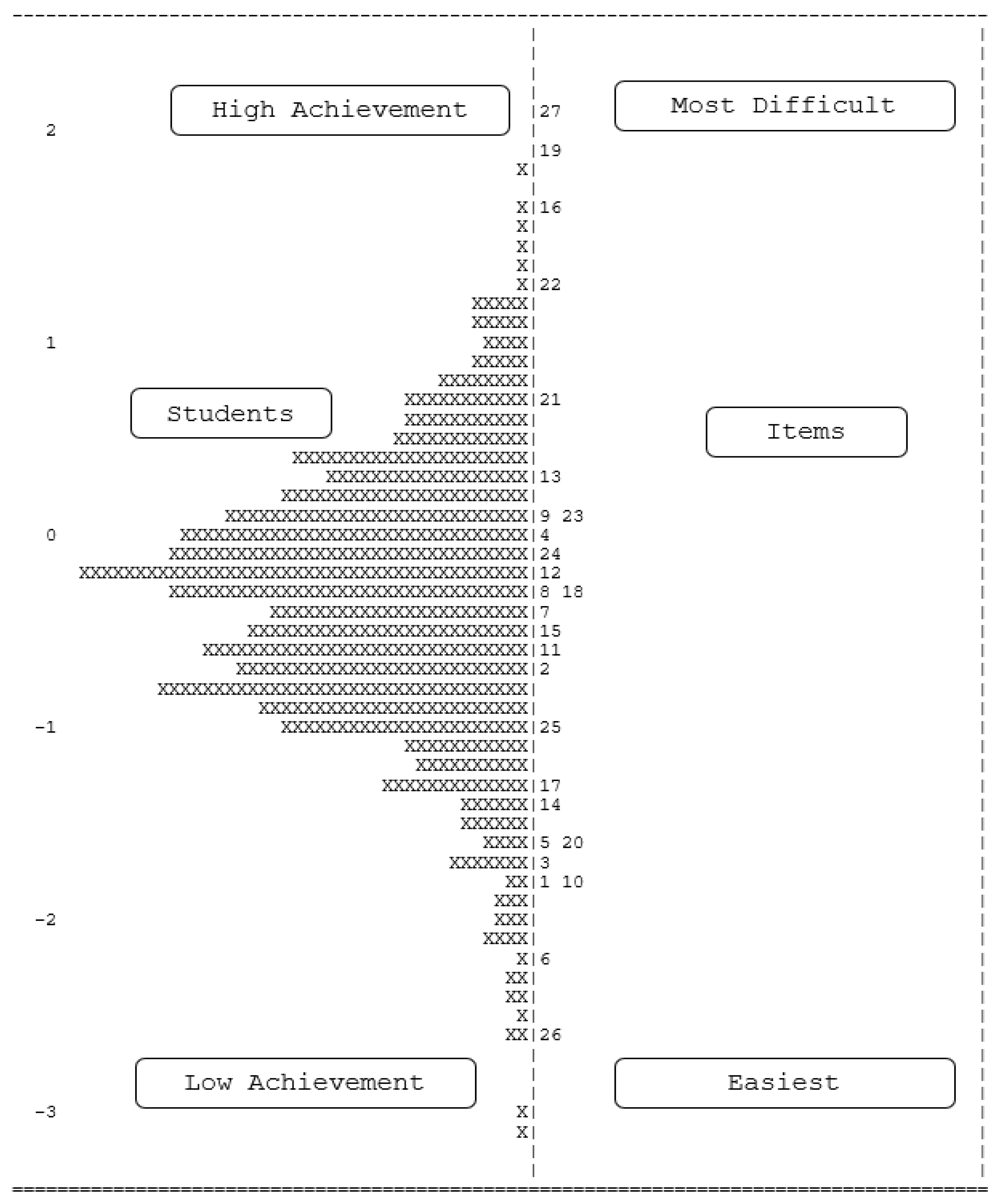

- RQ1: In what type of reading comprehension questions do students enjoy success when RTMRC is employed?

4.1.1. Reliability and Fit Statistics of the Test

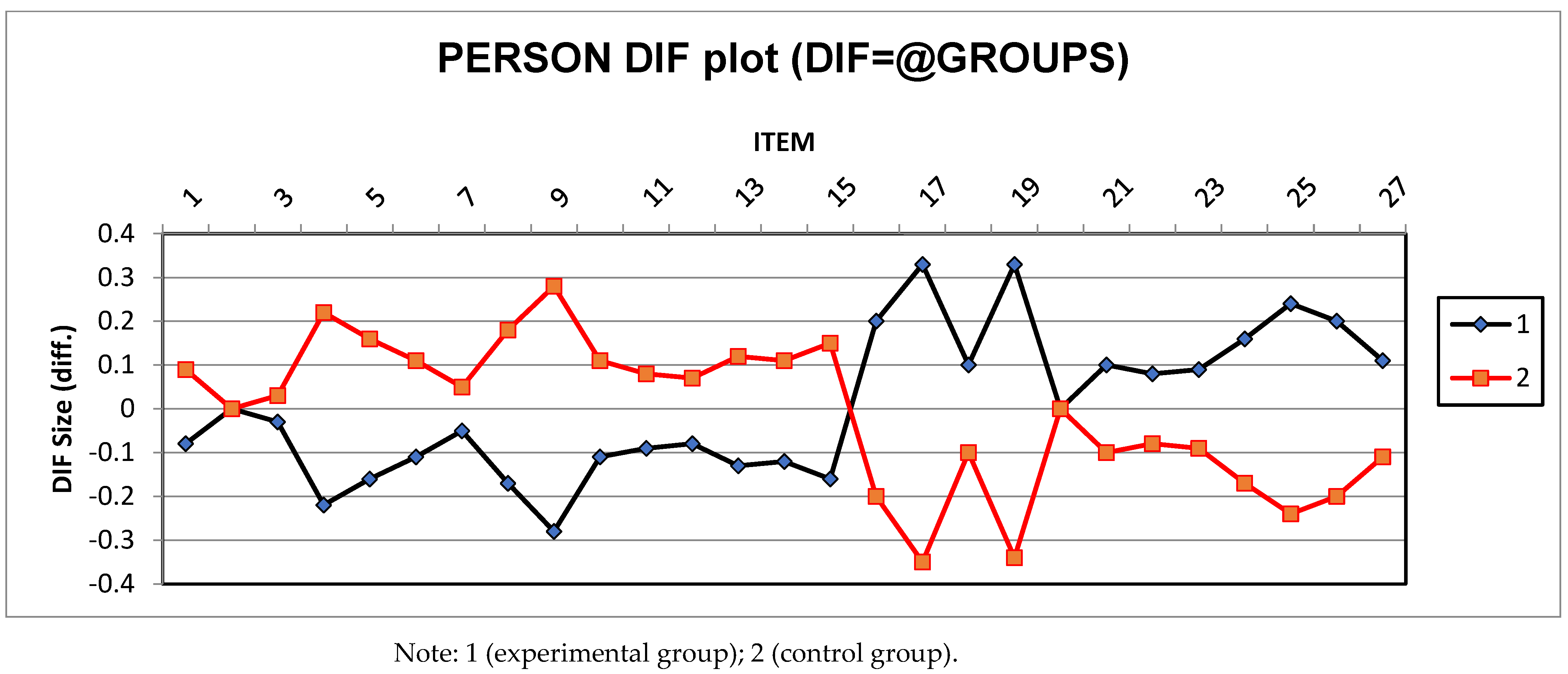

4.1.2. Differential Item Functioning (DIF) between Experimental and Control Groups

- RQ2: What is the effect of RTMRC on student reading comprehension?

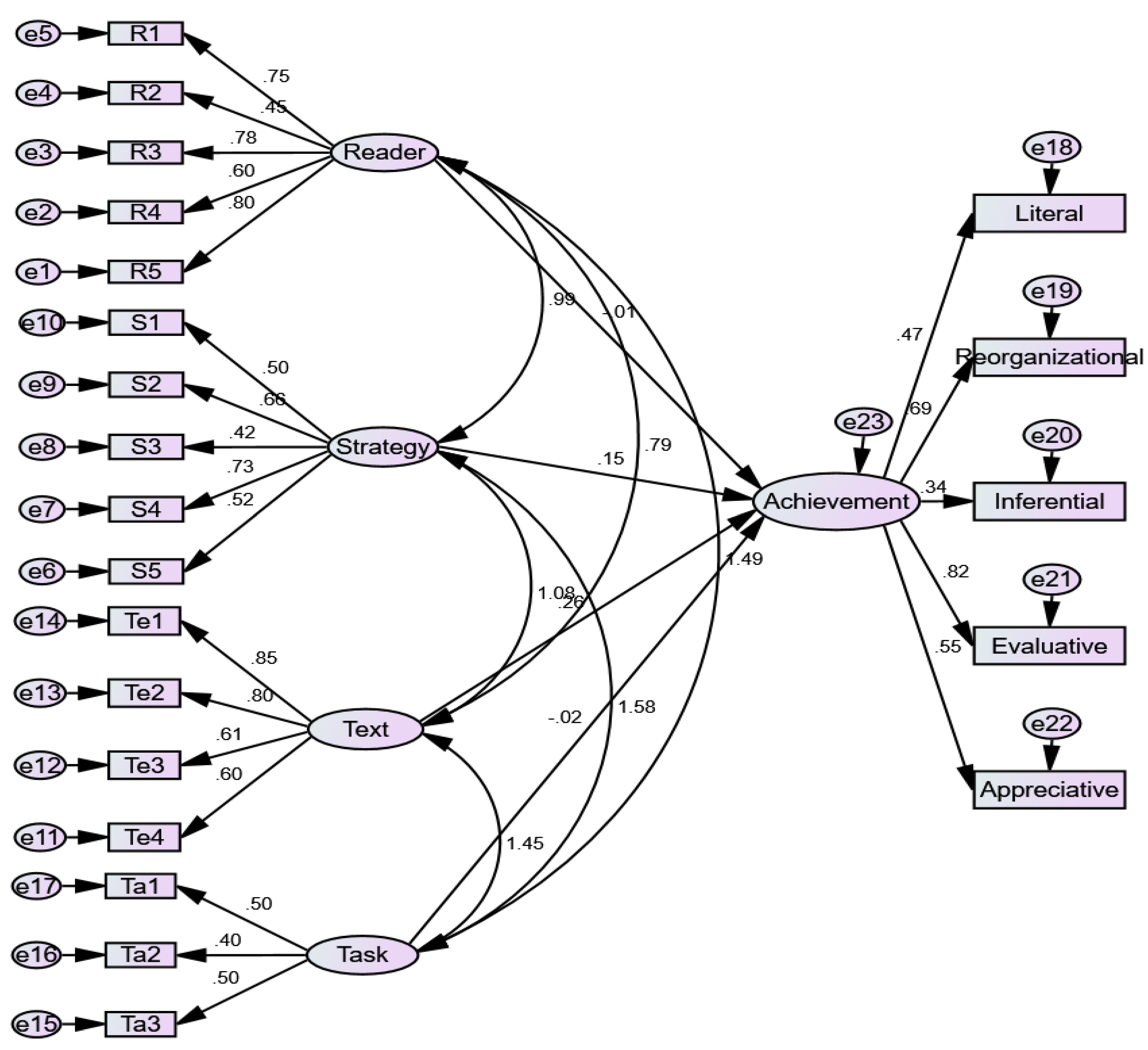

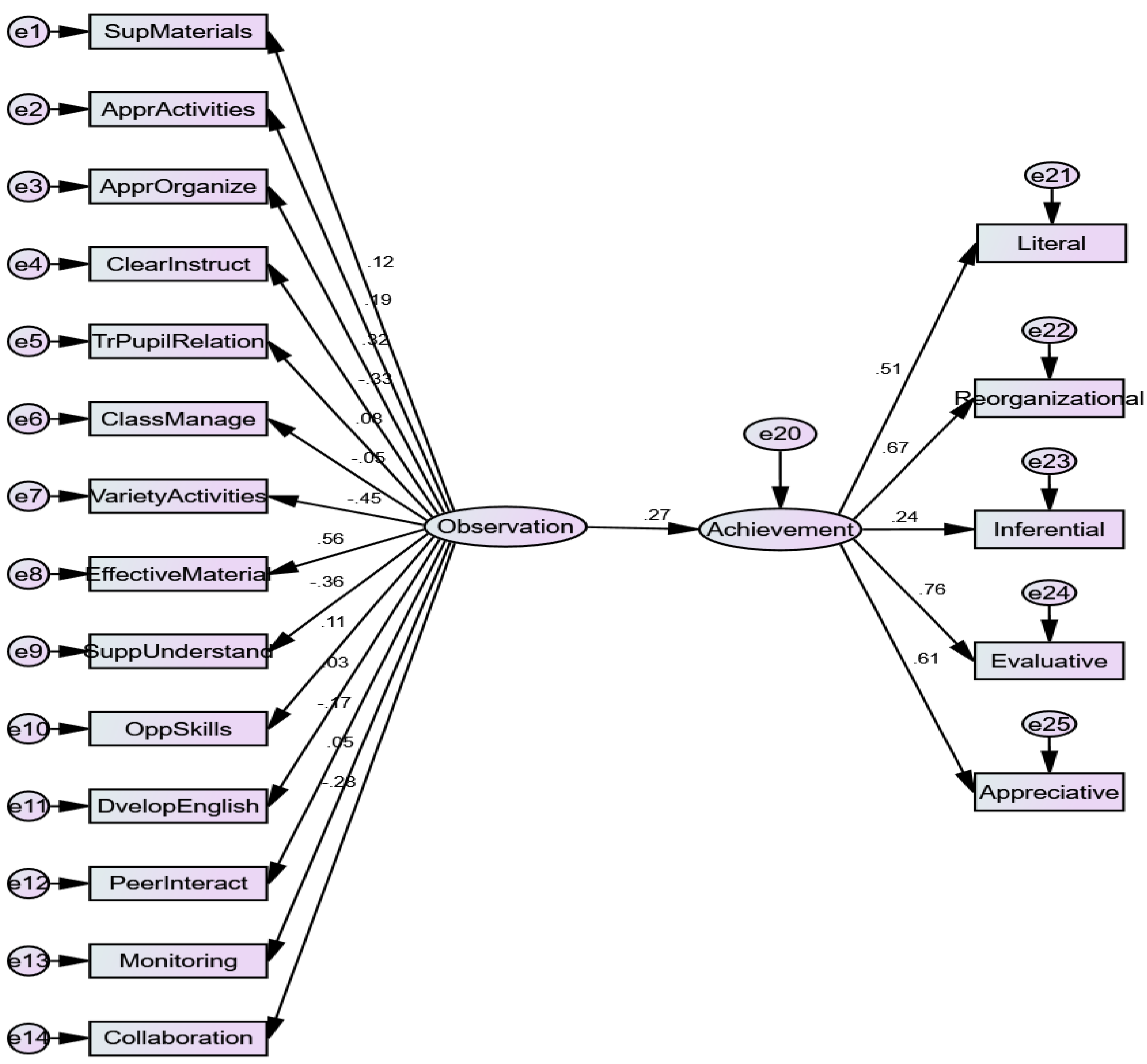

- RQ3: What is the effect of teacher reflections on student reading comprehension achievement?

- RQ4: What are teacher reflections on the instructional context (reader, strategy, text, and task) when RTMRC is employed?

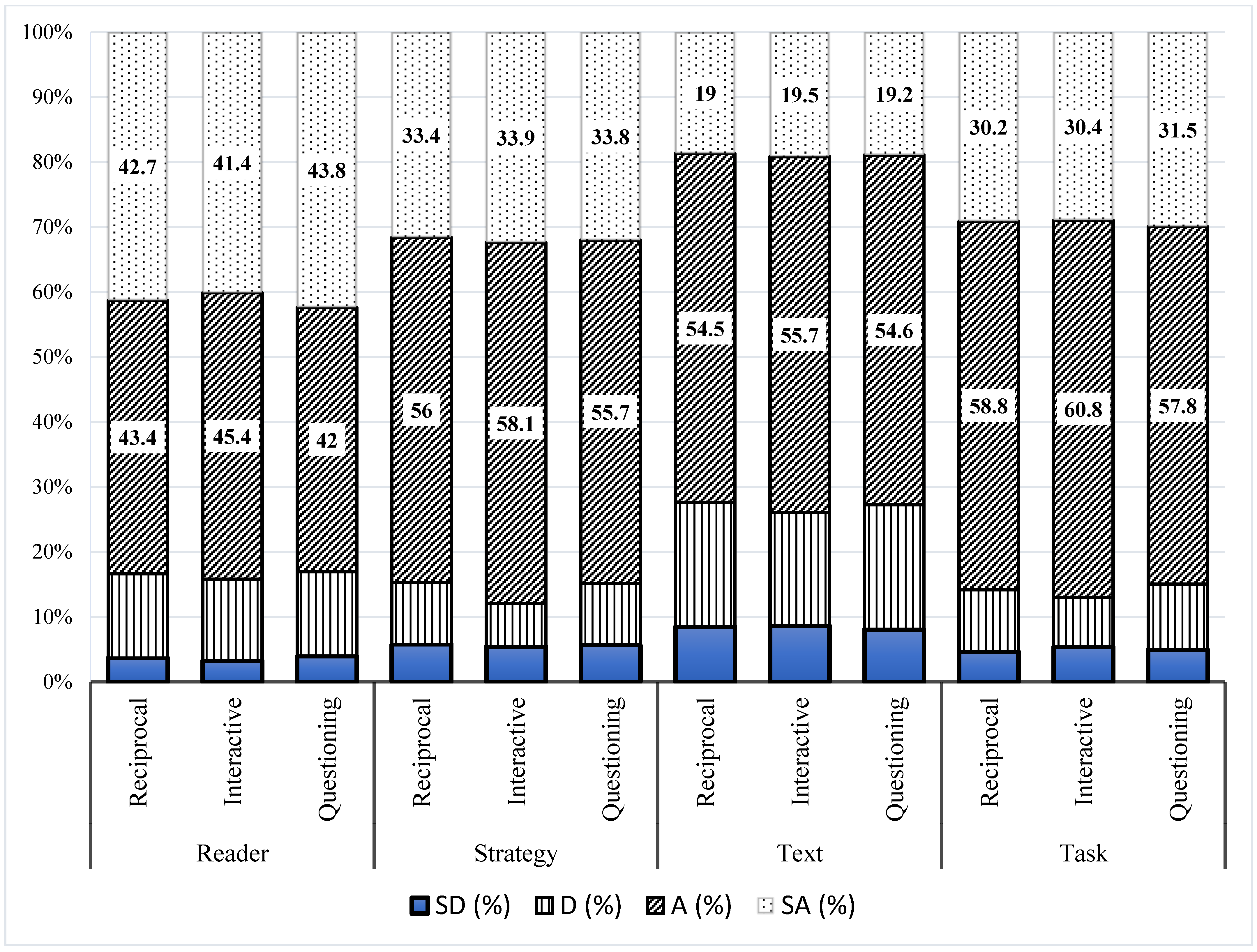

4.2. Results of the Student Questionnaire

4.2.1. Reflections on Reader

4.2.2. Reflections on Strategy

4.2.3. Reflections on Text

4.2.4. Reflections on Task

4.3. Results of the Observation Scheme

4.3.1. Reciprocal Teaching

4.3.2. Interactive Teaching

4.3.3. Questioning Strategy

5. Discussion and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Fatemipour, H. The Efficiency of the tools used for reflective teaching in ESL contexts. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2013, 93, 1398–1403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hulsman, R.L.; Harmsen, A.B.; Fabriek, M. Reflective teaching of medical communication skills with DiViDU: Assessing the level of student reflection on recorded consultations with simulated patients. Patient Educ. Couns. 2009, 74, 142–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quesada Pacheco, A. Reflective teaching and its impact on foreign language teaching. Actual. Investig. Educ. 2011, 5, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okkinga, M.; van Steensel, R.; van Gelderen, A.J.S.; Sleegers, P.J.C. Effects of reciprocal teaching on reading comprehension of low-achieving adolescents. The importance of specific teacher skills. J. Res. Read. 2018, 41, 20–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anyiendah, M.S.; Odundo, P.A.; Kibui, A. Aspects of the interactive approach that affect learners’ achievement in reading comprehension in Vihiga county, Kenya: A focus on background knowledge. Am. J. Soc. Sci. Humanit. 2019, 4, 269–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barjesteh, H.; Moghadam, B.A. Teacher questions and questioning strategies revised: A case study in EFL classroom in Iran. Indian J. Fundam. Appl. Life Sci. 2014, 4, 651–659. [Google Scholar]

- Richards, J.C.; Lockhart, C. Reflective teaching in second language classrooms. In Reflective Teaching in Second Language Classrooms; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aliakbari, M.; Adibpour, M. Reflective EFL education in Iran: Existing situation and teachers’ perceived fundamental challenges. Egit. Arast.-Eurasian J. Educ. Res. 2018, 2018, 129–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valdez, P.N.; Navera, J.A.; Esteron, J.J. What is reflective teaching? Lessons learned from ELT teachers from the Philippines. Asia-Pac. Educ. Res. 2018, 27, 91–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulla, M.B. Teacher training in Myanmar: Teachers’ perceptions and implications. Int. J. Instr. 2017, 10, 103–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodman, A.E. Foreword: Making history by investing in the future. In Investing in the Future: Rebuilding Higher Education in Myanmar; Institute of International Education, Ed.; IIE’s Center for International Partnerships: New York, NY, USA, 2013; pp. 5–8. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Educational Scientific and Cultural Organization. Strengthening Pre-Service Teacher Education in Myanmar (STEM): Phase II Final Narrative Report; UNESCO Yangon Project Office: Kyonku, Myanmar, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Wu, L.; Zhang, D. The effects of reciprocal teaching on reading comprehension: A meta-analysis. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 2019, 31, 645–675. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, L.; Wu, X.; Cai, J. Interactive teaching in the classroom: A literature review. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 1723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X. Does questioning strategy facilitate second language (L2) reading comprehension? The effects of comprehension measures and insights from reader perception. J. Res. Read. 2021, 44, 339–359. [Google Scholar]

- Palincsar, A.S.; Brown, A.L. Reciprocal teaching of comprehension fostering and comprehension monitoring activities. Cogn. Instr. 1984, 1, 117–175. [Google Scholar]

- Rodli, M.; Prastyo, H. Applying reciprocal teaching method in teaching reading. Stud. Linguist. Lit. 2017, 1, 112–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandel, E.; Osana, H.P.; Venkatesh, V. Addressing the effects of reciprocal teaching on the receptive and expressive vocabulary of 1st-grade students. J. Res. Child. Educ. 2013, 27, 407–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahimi, M.; Sadeghi, N. Impact of reciprocal teaching on EFL learners’ reading comprehension. Res. Appl. Linguist. 2014, 6, 64–86. [Google Scholar]

- Doolittle, P.; Hicks, D.; Triplett, C.; Nichols, W.; Young, C. Reciprocal teaching for reading comprehension in higher education: A strategy for fostering the deeper understanding of texts. Int. J. Teach. Learn. High. Educ. 2006, 17, 106–118. [Google Scholar]

- Takala, M. The effects of reciprocal teaching on reading comprehension in mainstream and special (SLI) education. Scand. J. Educ. Res. 2006, 50, 559–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bounouh, A.; Merzoug, N. The effect of reciprocal teaching on reading comprehension and metacognitive strategies: A meta-analysis. Read. Writ. 2022, 35, 161–194. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, L.; Zhao, J.; Zhang, D. A systematic review of reciprocal teaching: From the perspective of learning theory. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 664345. [Google Scholar]

- Baker, W.; Boonkit, K. Learning strategies in reading and writing: EAP contexts. Reg. Lang. Cent. J. 2016, 35, 299–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ardhani, R.R.V.K. The effectiveness of bottom-up and top-down approaches in the reading comprehension skill for junior high school students. J. Engl. Educ. 2016, 5, 80–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birch, B. English L2 Reading: Getting to the Bottom; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Khaki, N. Improving reading comprehension in a foreign language: Strategic reader. Read. Matrix 2014, 14, 186–200. [Google Scholar]

- Karimi, M.; Jafari, S.M. The effect of interactive teaching on reading comprehension of Iranian EFL learners. Read. Matrix Int. Online J. 2019, 19, 94–105. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Issa, A.S. Effectiveness of bottom-up and top-down interactive strategies on reading comprehension: An experimental study with Saudi Arabian EFL learners. Issues Educ. Res. 2020, 30, 785–802. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.; Wu, Z. A comparative study of two interactive reading teaching methods: Bottom-up and top-down. J. Lang. Teach. Res. 2021, 12, 853–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corley, M.A.; Rauscher, W.C. Deeper learning through questioning. Teach. Excell. Adult Lit. 2013, 12, 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Peterson, D.S.; Taylor, B.M. Using higher order questioning to accelerate students’ growth. Read. Teach. 2012, 65, 295–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reeves, C. Developing a Framework for Assessing and Comparing the Cognitive Challenge of Home Language Examination; UMALUSI Publishing: Pretoria, South Africa, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, K.; Wang, X.; Li, M. Questioning the impact of teacher questioning on EFL reading comprehension: A meta-analysis. Lang. Teach. Res. 2021, 25, 481–498. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, S.; Zhang, Y.; Qi, X. The effectiveness of teacher-generated vs. student-generated questions on reading comprehension: A meta-analysis. Read. Writ. 2020, 33, 2069–2095. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Y.J. The effects of questioning strategies on the reading comprehension of Korean EFL students. TESOL J. 2019, 10, e00402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madsen, S.R.; Cook, B.J. Transformative learning: UAE, women, and higher education. J. Glob. Responsib. 2010, 1, 127–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mezirow, J. Learning to think like an adult: Core concepts of transformation theory. In The Handbook of Transformative Learning: Theory, Research, and Practice; Taylor, E.W., Cranton, P., Eds.; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2012; pp. 73–95. [Google Scholar]

- Christie, M.; Carey, M.; Robertson, A.; Grainger, P. Putting transformative learning theory into practice. Aust. J. Adult Learn. 2015, 55, 9–30. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, E.W. An update of transformative learning theory: A critical review of the empirical research (1999–2005). Int. J. Lifelong Educ. 2007, 26, 173–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mezirow, J. Transformative learning as discourse. J. Transform. Educ. 2006, 1, 58–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taggart, G.L.; Wilson, A.P. Promoting Reflective Thinking in Teachers: 50 Action Strategies; Corwin Press: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Clarke, P.A. Reflective teaching model: A tool for motivation, collaboration, self- reflection, and innovation in learning. Ga. Educ. Res. J. 2008, 5, 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Dennison, P. Reflective practice: The enduring influence of Kolb’s Experiential Learning Theory. Compass J. Learn. Teach. 2012, 1, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollard, A.; Black-Hawkins, K.; Hodges, G.C.; Dudley, P.; James, M.; Linklater, H.; Swaffield, S.; Swann, M.; Turner, F.; Warwick, P.; et al. Reflective Teaching in Schools, 4th ed.; Bloomsbury Publishing Plc.: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Babaei, M.; Abednia, A. Reflective teaching and self-efficacy beliefs: Exploring relationships in the context of teaching EFL In Iran. Aust. J. Teach. Educ. 2016, 41, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garzon, E.A.A. Unlicensed EFL teachers co-constructing knowledge and transforming curriculum through collaborative-reflective inquiry. Rev. Profile Issues Teach. Prof. Dev. 2018, 20, 73–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy-Clark, S.; Eddles-Hirsch, K.; Francis, T.; Cummins, G.; Ferantino, L.; Tichelaar, M.; Ruz, L. Developing pre-service teacher professional capabilities through action research. Aust. J. Teach. Educ. 2018, 43, 38–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratminingsih, N.M.; Padmadewi, N.N.; Artini, L.P. Incorporating self and peer assessment in reflective teaching practices. Int. J. Instr. 2017, 10, 165–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robertson, S. Reading for understanding: Toward an RGD program in reading comprehension. In The ASHA Leader; RAND Institution: Arlington, TX, USA, 2017; Volume 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, B.J. Diagnostic Teaching of Reading: Techniques for Instruction and Assessment, 6th ed; Pearson/Merrill/Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- van Staden, S.; Howie, S. Reading between the lines: Contributing factors that affect Grade 5 student reading performance as measured across South Africa’s 11 languages. Educ. Res. Eval. 2012, 18, 85–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Zhang, L.J. Relationships between Chinese college test takers’ strategy use and EFL reading test performance: A structural equation modeling approach. RELC J. 2013, 44, 35–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suwanto. The effectiveness of the paraphrasing strategy on reading comprehension in Yogyakarta city. J. Lit. Lang. Linguist.-Open Access Int. J. 2014, 4, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Yusuf, Y.Q.; Fitrisia, D. Investigating metacognitive awareness of reading strategies to strengthen students’ performance in reading comprehension. Asia Pac. J. Educ. Educ. Former. Known J. Educ. Educ. 2015, 30, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Widdowson, H.G. Teaching Language as Communication; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, X. Study on factors affecting learning strategies in reading comprehension. J. Lang. Teach. Res. 2016, 7, 586–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.J. English Language Teaching Today. Linking Theory and Practice; Renandya, W.A., Widodo, H.P., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 127–142. [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert, J. A study of ESL students’ perceptions of their digital reading. Read. Matrix Int. Online J. 2017, 17, 179–195. [Google Scholar]

- Oo, T.Z.; Habók, A. The development of a reflective teaching model for reading comprehension in English language teaching. Int. Electron. J. Elem. Educ. 2020, 13, 127–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brookfield, S.D. Becoming a Critically Reflective Teacher; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Mastropieri, M.A.; Scruggs, T.E.; Mohler, L.; Beranek, M.; Spencer, V.G.; Boon, R.T.; Tilley, C. Reciprocal teaching: Implications for students with learning difficulties. J. Learn. Disabil. 2017, 50, 519–531. [Google Scholar]

- Magliano, J.P.; Millis, K.K.; Schraw, G. Reciprocal teaching: Review and new directions. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 2019, 31, 307–333. [Google Scholar]

- Dew, T.P.; Swanto, S.; Pang, V. The effectiveness of reciprocal teaching as reading comprehension intervention: A systematic review. J. Nusant. Stud. JONUS 2021, 6, 156–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mafarja, N.; Zulnaidi, H. Relationship between critical thinking and academic self- concept: An experimental study of Reciprocal teaching strategy. Think. Ski. Creat. 2022, 45, 101113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mihai, A.; Bobîrnac, G.; Järv, R. Reciprocal teaching: A meta-analysis of the effects across subject areas and age groups. Educ. Res. Rev. 2021, 34, 100408. [Google Scholar]

- Deng, L.; Li, Y.; Wen, Q. Interactive teaching and its effects on academic achievement: A meta-analysis. J. Educ. Res. 2020, 113, 283–296. [Google Scholar]

- Kharbouch, R.; Elhajjaji, F.; El Fahim, M. The impact of interactive teaching on students’ motivation and academic achievement. J. Educ. Pract. 2021, 12, 166–173. [Google Scholar]

- Blanton, W.E.; Griffin, T.J.; Winn, W.; Fontenot, D. The challenges and opportunities of interactive teaching: A case study. J. Educ. Technol. Dev. Exch. 2018, 11, 35–42. [Google Scholar]

- Stephens, A.L.; Roderick, S.; Shin, N.; Damelin, D. Students do not always mean what we think they mean: A Questioning strategy to elicit the reasoning behind unexpected causal patterns in student system models. Int. J. Sci. Math. Educ. 2022, 0123456789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castells, N.; Minguela, M.; Solé, I.; Miras, M.; Nadal, E.; Rijlaarsdam, G. Improving questioning–answering strategies in learning from multiple complementary texts: An intervention study. Read. Res. Q. 2022, 57, 879–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.Y.; Chiu, M.C.; Lee, Y.T. Effects of video lecture presentation style and questioning strategy on learner flow experience. Innov. Educ. Teach. Int. 2021, 58, 473–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gudeta, D. Professional development through reflective practice: The case of Addis Ababa secondary school EFL in-service teachers. Cogent Educ. 2022, 9, 2030076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karnieli-Miller, O. Reflective practice in the teaching of communication skills. Patient Educ. Couns. 2020, 103, 2166–2172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lubbe, W.; Botha, C.S. The dimensions of reflective practice: A teacher educator’s and nurse educator’s perspective. Reflective Pract. 2020, 21, 287–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menon, D.; Azam, S. Investigating preservice teachers’ science teaching self-efficacy: An analysis of reflective practices. Int. J. Sci. Math. Educ. 2021, 19, 1587–1607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suphasri, P.; Chinokul, S. Reflective practices in teacher education: Issues, challenges, and considerations. Pasaa 2021, 62, 236–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, H.; Wu, S. Reflective teaching and its effects on improving EFL learners’ reading comprehension. J. Lang. Teach. Res. 2020, 11, 539–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sedgwick, P. Cluster sampling. BMJ 2014, 348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surtantini, R. Reading comprehension question levels in grade X English students’ book in light of the issues of curriculum policy in Indonesia. PAROLE J. Linguist. Educ. 2019, 9, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gliner, J.A.; Morgan, G.A.; Leech, N.L. Research Methods in Applied Settings: An Integrated Approach to Design and Analysis, 3rd ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Lestari, A.A. The effectiveness of reciprocal teaching method embedding critical thinking towards MIA second graders’ reading comprehension of MAN 1 kendari. J. Teach. Engl. 2016, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayat, B. Adjustment for guessing in a basic statistics test for Indonesian undergraduate psychology students using the Rasch model. Cogent Educ. 2022, 9, 2059044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismail, N.E.; Jimam, N.S.; Dapar, M.L.P.; Ahmad, S. Validation and reliability of healthcare workers’ knowledge, attitude, and practice instrument for uncomplicated malaria by Rasch measurement model. Front. Pharmacol. 2020, 10, 15–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kotrlik, J.W.; Williams, H.A.; Jabor, M.K. Reporting and interpreting effect size in quantitative agricultural education research. J. Agric. Educ. 2011, 52, 132–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kline, R.B. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling, 3rd ed.; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Kline, R.B. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling, 4th ed.; Guilford: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Oo, T.Z.; Habók, A. Reflection-based questioning: Aspects affecting Myanmar students’ reading comprehension. Heliyon 2022, 8, e09864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oo, T.Z.; Magyar, A.; Habók, A. Effectiveness of the reflection-based reciprocal teaching approach for reading comprehension achievement in upper secondary school in Myanmar. Asia Pac. Educ. Rev. 2021, 22, 675–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polat, M.; Turhan, N.S.; Toraman, Ç. Comparison of classical test theory vs. multi-facet Rasch theory. Pegem Egit. Ogretim Derg. 2022, 12, 213–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myanmar Ministry of Education. National Education Strategic Plan Summary (2016–2021), 1st ed.; Minstry of Education: Nay Pyi Taw, Myanmar, 2016.

- Soe, M.Z.; Swe, A.M.; Aye, N.K.M.; Mon, N.H. Reform of the Education System: Case Study of Myanmar. Reg. Res. Pap. 2018; 1–28. Available online: http://afeo.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/Reform-of-the-Education-System-in-Myanmar-Case-Study.pdf (accessed on 18 April 2023).

- Töman, U. Investigation of reflective teaching practice effect on training development skills of the pre-service teachers. J. Educ. Train. Stud. 2017, 5, 232–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uzaimi, A.; Febriand Abdel, J.; Armaidah, R. Improving reading comprehension through reciprocal teaching. Acta Univ. Agric. Silvic. Mendel. Brun. 2015, 16, 39–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Htun, N.N.; Nu, T.; Oo, T.Z. The Effectiveness of the reflection-based interactive teaching approach on students’ reading comprehension achievement. J. Field-Based Lesson Stud. 2023, 4, 85–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boud, D.; Keogh, R.; Walker, D. Reflection: Turning Experience into Learning; Routledge: London, UK, 1985. [Google Scholar]

| Level | Reading Comprehension Question-Levels | Call for Students’ Skills | Example Questions |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Literal (recognition or recall of)

| To locate or identify any kind of explicitly stated fact or detail (for example, names of characters or places, likenesses and differences, reasons for actions) in a reading text |

|

| 2 | Reorganizational

| To organize, sort into categories, paraphrase, or consolidate explicitly stated information or ideas in a reading text |

|

| 3 | Inferential

| To use conjecture, personal intuition, experience, background knowledge, or clues in a reading text as a basis for forming hypotheses and inferring details or ideas (for example, the significance of a theme, the motivation or nature of a character) that are not explicitly stated in the reading text/material |

|

| 4 | Evaluative (judgement of)

| To make an evaluative judgment (for example, on qualities of accuracy, acceptability, desirability, worth, or probability) by comparing information or ideas presented in a reading text using external criteria provided (by other sources/authorities) or internal criteria (students’ own values, experiences, or background knowledge of the subject) |

|

| 5 | Appreciative

| To show emotional and aesthetic/literary sensitivity to the reading text and show a reaction to the worth of its psychological and artistic elements (such as literary techniques, forms, and styles) |

|

| Construct | Experimental Group | Control Group | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Items | Persons | Items | Persons | |

| Number | 27 | 228 | 27 | 230 |

| Mean | 213.60 | 25.10 | 206.30 | 24.50 |

| Standard deviation | 72.00 | 3.80 | 70.30 | 3.60 |

| Reliability (Cronbach’s alpha) | 0.93 | 0.74 | 0.94 | 0.70 |

| Separation | 1.32 | 1.80 | 1.38 | 1.50 |

| MNSQ (infit) | 0.94 | 0.99 | 0.98 | 0.97 |

| MNSQ (outfit) | 0.95 | 0.95 | 0.96 | 0.96 |

| ZSTD (infit) | −1.20 | −0.10 | −1.70 | 0.00 |

| ZSTD (outfit) | −1.30 | −0.30 | −1.30 | −0.10 |

| Chi-squared (χ2) | 7886.68 | 8125.11 | ||

| df | 5953 | 5901 | ||

| Source | df | Mean Square | F-Value | p-Value | η2 (Eta Square) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-test | 1 | 106.39 | 3.80 | 0.052 | 0.08 |

| Groups | 1 | 7797.71 | 278.72 | 0.000 *** | 0.38 |

| Error | 455 | 27.97 |

| Groups | Number | Unadjusted | Adjusted | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | Standard Deviation | Mean | Standard Error | ||

| Experimental | 228 | 37.13 | 5.80 | 35.20 | 0.35 |

| Control | 230 | 28.90 | 4.76 | 30.45 | 0.31 |

| Instruments | χ2 | df | p-Value | Absolute Index, SRMR (<0.05) * | Comparative Index, CFI (≥0.9) * | Parsimonious Index, RMSEA (<0.08) * |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Student Questionnaire | 412.87 | 199 | 0.06 | 0.04 | 0.90 | 0.04 |

| Observation Scheme | 164.74 | 151 | 0.21 | 0.03 | 0.96 | 0.01 |

| Events to Be Observed | Levels | Reciprocal Teaching (%) | Interactive Teaching (%) | Questioning Strategy (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Appropriateness of the selection of materials | 1 2 3 4 | 10.0 33.3 46.7 10.0 | 6.7 23.3 70.0 | 10.0 33.3 50.0 6.7 |

| Appropriateness of planning the activities | 1 | |||

| 2 | 6.7 | 6.6 | 6.7 | |

| 3 | 60.0 | 66.7 | 63.3 | |

| 4 | 33.3 | 26.7 | 30.0 | |

| Appropriateness of the organization of the class | 1 | 6.7 | 6.7 | |

| 2 | 30.0 | 10.0 | 33.3 | |

| 3 | 46.7 | 73.3 | 50.0 | |

| 4 | 16.7 | 16.7 | 10.0 | |

| Clear instructions and models of English language use | 1 | 10.0 | 6.7 | 6.7 |

| 2 | 23.3 | 26.7 | 26.7 | |

| 3 | 56.7 | 63.3 | 63.3 | |

| 4 | 10.0 | 3.3 | 3.3 | |

| Effective teacher–pupil interaction | 1 | |||

| 2 | 10.0 | 3.3 | 6.7 | |

| 3 | 53.3 | 63.3 | 70.0 | |

| 4 | 36.7 | 33.3 | 23.3 | |

| Effective organization and management of the whole class | 1 2 3 4 | 3.3 30.0 53.3 13.3 | 3.3 13.3 56.7 26.7 | 23.3 76.7 |

| Variety of activities | 1 | 10.0 | ||

| 2 | 23.3 | 30.0 | 6.7 | |

| 3 | 60.0 | 46.7 | 60.0 | |

| 4 | 16.7 | 13.3 | 33.3 | |

| Effective materials | 1 | 3.3 | ||

| 2 | 16.7 | 3.3 | ||

| 3 | 53.3 | 66.7 | 80.0 | |

| 4 | 30.0 | 33.3 | 13.3 | |

| Support for understanding | 1 | 3.3 | 6.7 | |

| 2 | 16.7 | 20.0 | 10.0 | |

| 3 | 60.0 | 63.3 | 56.6 | |

| 4 | 20.0 | 16.7 | 26.7 | |

| Opportunities for learners to apply their existing skills and knowledge | 1 | 3.3 | 3.3 | |

| 2 | 16.7 | 23.3 | 6.6 | |

| 3 | 53.3 | 53.3 | 66.7 | |

| 4 | 26.7 | 20.0 | 26.7 | |

| Opportunities for developing English language use | 1 | 3.3 | 10.0 | |

| 2 | 23.3 | 20.0 | 46.7 | |

| 3 | 60.0 | 56.7 | 50.0 | |

| 4 | 13.3 | 13.3 | 3.3 | |

| Opportunities for peer group interaction | 1 | 6.7 | ||

| 2 | 23.3 | 3.3 | 20.0 | |

| 3 | 46.7 | 46.7 | 60.0 | |

| 4 | 30.0 | 43.3 | 20.0 | |

| Effective monitoring of learning | 1 | 3.3 | ||

| 2 | 13.3 | 23.3 | 16.7 | |

| 3 | 46.7 | 53.3 | 63.3 | |

| 4 | 40.0 | 20.0 | 20.0 | |

| Sensitive environment for individual students and their communicative needs | 1 | 3.3 | 3.3 | |

| 2 | 26.7 | 46.7 | 16.6 | |

| 3 | 46.7 | 43.3 | 66.7 | |

| 4 | 23.3 | 6.7 | 16.7 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Oo, T.Z.; Habók, A.; Józsa, K. Qualifying Method-Centered Teaching Approaches through the Reflective Teaching Model for Reading Comprehension. Educ. Sci. 2023, 13, 473. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci13050473

Oo TZ, Habók A, Józsa K. Qualifying Method-Centered Teaching Approaches through the Reflective Teaching Model for Reading Comprehension. Education Sciences. 2023; 13(5):473. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci13050473

Chicago/Turabian StyleOo, Tun Zaw, Anita Habók, and Krisztián Józsa. 2023. "Qualifying Method-Centered Teaching Approaches through the Reflective Teaching Model for Reading Comprehension" Education Sciences 13, no. 5: 473. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci13050473

APA StyleOo, T. Z., Habók, A., & Józsa, K. (2023). Qualifying Method-Centered Teaching Approaches through the Reflective Teaching Model for Reading Comprehension. Education Sciences, 13(5), 473. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci13050473