After the Pandemic: Teacher Professional Development for the Digital Educational Innovation

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review, Previous Research and the Research Framework

2.1. Teacher Professional Development through Peer Learning and Pandemic Experiences

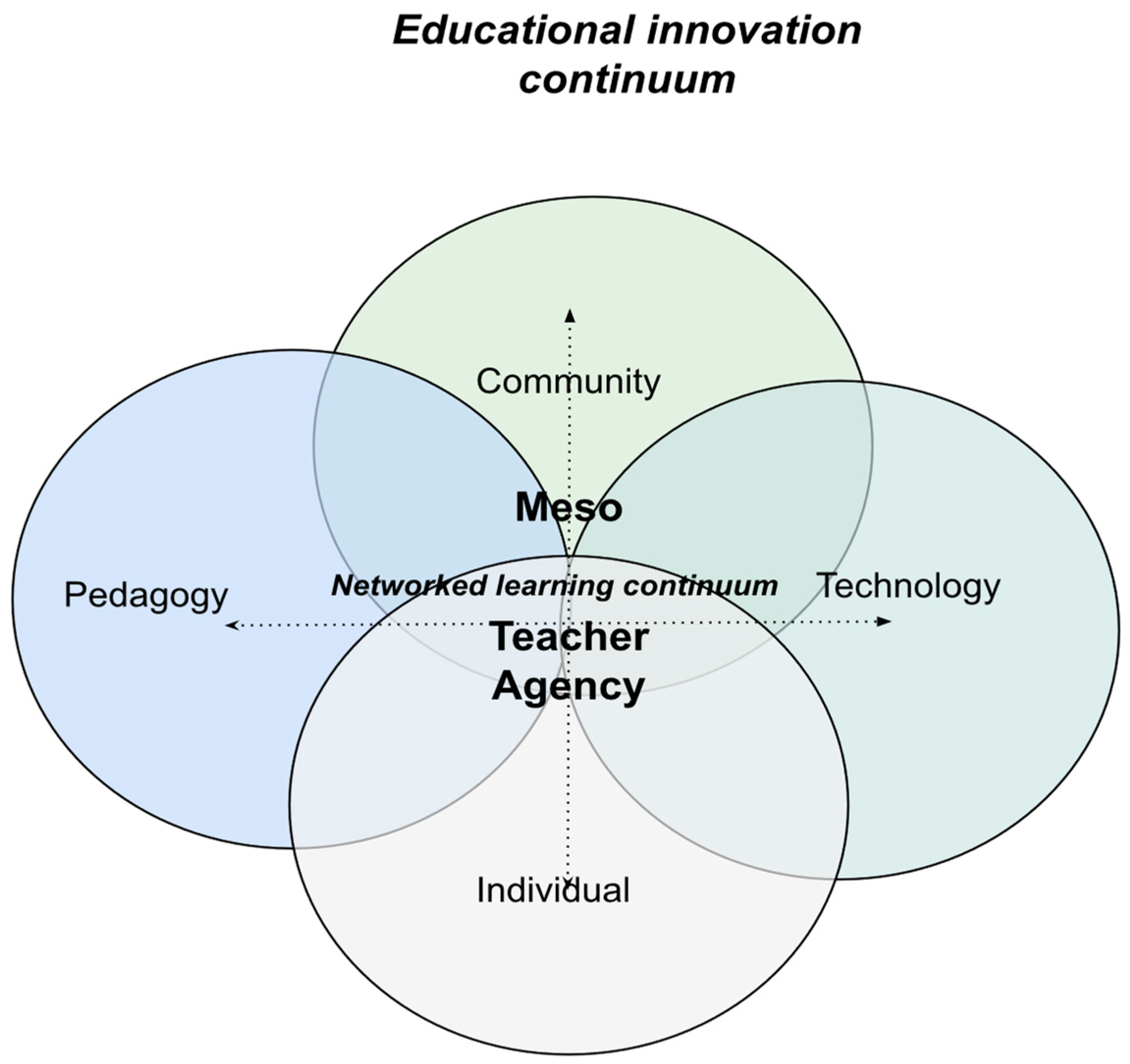

2.2. Background: Educational Innovation, Educational Change and Teacher Agency

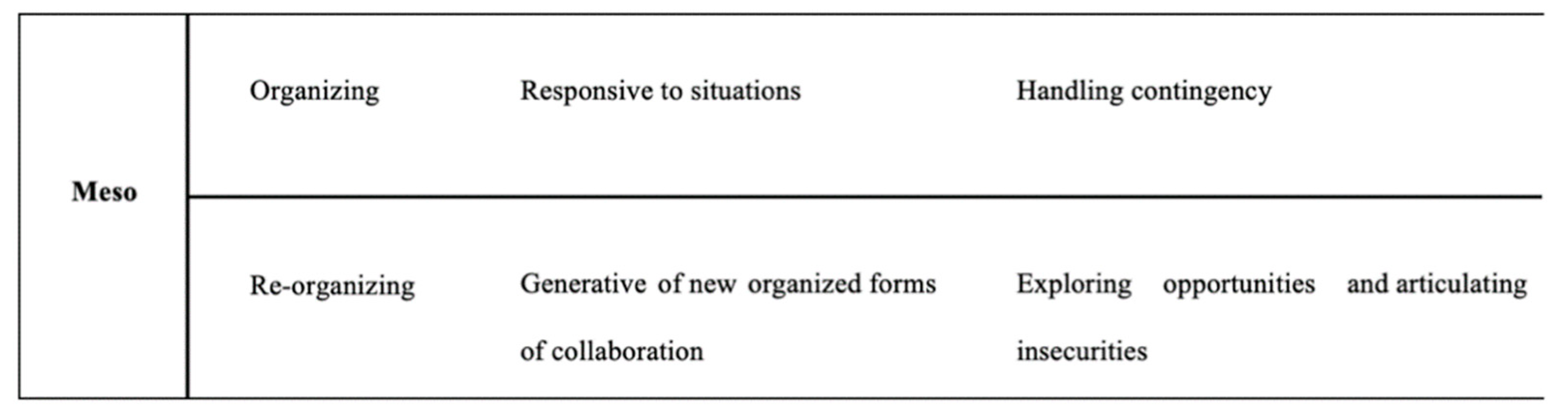

2.3. Theoretical Framework: Analysing the Meso-Space

3. Study Context, Methodology and Methods

3.1. Study Context

Methodology, Research Questions, Data Collection and Analysis Methods

4. Results

4.1. Theoretical Dimensions and Explorations

4.1.1. Reorganization for Educational Innovation—Increased Variety

4.1.2. Meso and Macro Interactions—Teacher Professional Development Support during the COVID-19 Pandemic

5. Discussion and Conclusions: Teacher Professional Development Perspectives—A Proposal

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Study Protocol and Interview Questions

- Section 1: About you

- What is your current position and discipline?

- How long have you been teaching?

- Section 2: About your experience with planned inclusive digital and open pedagogy (especially pre-COVID)

- What is your experience with digital learning and teaching? Tell us about any innovation that you have performed or been involved with, with educational technologies in your career.

- What is your experience with distance learning and teaching?

- Have you used, or been asked to use, an increasing number of platforms and/or virtual learning environments during the pandemic?

- ○

- With this question, we want to determine the cognitive load imposed on both students and teaching staff.

- Did you feel that you worked more on distance? In what ways?

- What is your experience with open education?

- ○

- This should determine whether the experience is largely individual—such as searching and using OERs or is it more active, connected with others and collaborative, such as creating, sharing, remixing or embedding open practices in their teaching.

- Are you familiar with Open Education initiatives? If so, please describe your experience with open education. What is your stance on open education?

- What is your experience with inclusive education, including usability and digital accessibility?

- What is your experience with networked learning, if any?

- ○

- By networked learning, we mean “harnessing our human ability to engage in networks of both people and tools to enable learning experiences”.

- Do you use any educational framework (or a set of guidelines), either institutional, national, or European? If not, how do you decide the way you teach? Please tell us about it.

- Section 3: About your experience with Emergency Remote Teaching (ERT)

- Have you been involved in distance learning as a result of COVID? What would you highlight?

- Which opportunities have you explored as a result of remote teaching, for improving the way you and your institution provide education?

- Can you share a best practice that emerged out of ERT? For example, if faced with ERT once again, this is a practice or example to try and follow.

- Which challenges, uncertainties or difficulties have you encountered in that respect, both for you and your students? (please highlight the most significant ones, as this question could dominate the interview!)

- ○

- the order of these questions is up to the interviewer, the interviewee, and the context.

- Section 4: About your support, training AND networking needs within ERT in COVID times

- What kind of support did you have from your school and the educational authorities in your country/region? Please tell us both positive aspects and those to be improved about the instructions, guidance and support you have received.

- What kind of normative and recommendatory support did you receive regarding emergency remote teaching? Was it useful and how?

- What kind of training or support have you received? How did this help you?

- What kind of training or support would you like to have received?

- Have you shared knowledge and best practices with colleagues? How did the sharing occur?

- ○

- (optional) Do you continue to share knowledge and practices in this manner? At the same frequency as during ERT or more/less?

- Have you participated in communities of practice with practitioners in other institutions?

- How would you describe an ideal training programme/course for teaching with high standards online and with digital technology?

- How would you describe an ideal space for sharing best practices with other practitioners?

References

- Eradze, M.; Bardone, E.; Dipace, A. Theorising on COVID-19 Educational Emergency: Magnifying Glasses for the Field of Educational Technology. Learn. Media Technol. 2021, 46, 404–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eradze, M.; Bardone, E.; Tinterri, A.; Dipace, A. Self-Initiated Online Communities of Teachers as an Expanded Meso Space. Prof. Dev. Educ. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fullan, M. Learning and the Pandemic: What’s next? Prospects 2020, 49, 25–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodges, C.; Moore, S.; Lockee, B.; Trust, T.; Bond, A. The Difference between Emergency Remote Teaching and Online Learning. Educ. Rev. 2020, 27. Available online: https://vtechworks.lib.vt.edu/bitstream/handle/10919/104648/facdev-article.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y (accessed on 17 February 2023).

- Al-Freih, M. From the Adoption to the Implementation of Online Teaching in a Post-COVID World: Applying Ely’s Conditions of Change Framework. Educ. Sci. 2022, 12, 757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giovannella, C.; Passarelli, M.; Alkhafaji, A.S.A.; Negrón, A.P.P. A Comparative Study on the Effects of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Three Different National University Learning Ecosystems as Bases to Derive a Model for the Attitude to Get Engaged in Technological Innovation (MAETI). Interact. Des. Archit. J. 2021, 47, 167–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beardsley, M.; Albó, L.; Aragón, P.; Hernández-Leo, D. Emergency Education Effects on Teacher Abilities and Motivation to Use Digital Technologies. Br. J. Educ. Technol. 2021, 52, 1455–1477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albó, L.; Beardsley, M.; Martínez-Moreno, J.; Santos, P.; Hernández-Leo, D. Emergency Remote Teaching: Capturing Teacher Experiences in Spain with Selfie. In Proceedings of the Lecture Notes in Computer Science (Including Subseries Lecture Notes in Artificial Intelligence and Lecture Notes in Bioinformatics); Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020; Volume 12315 LNCS, pp. 318–331. [Google Scholar]

- Luik, P.; Lepp, M. Activity of Estonian Facebook Group during Transition to E-Learning due to COVID-19. In Proceedings of the European Conference on e-Learning, Berlin, Germany, 28–30 October 2020; Academic Conferences International Limited: Berlin, Germany; pp. 308–XVII. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, T.; Eradze, M.; Kobakhidze, M.N. Finding a Silver Lining in the COVID-19 Pandemic: Participant Observation of a Teachers’ Online Community in Georgia. In Global Education and the Impact of Institutional Policies on Educational Technologies; Loureiro, M.J., Loureiro, A., Gerber, H.R., Eds.; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2022; pp. 267–288. [Google Scholar]

- Kaden, U. COVID-19 School Closure-Related Changes to the Professional Life of a K–12 Teacher. Educ. Sci. 2020, 10, 165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryberg, T. Postdigital Research, Networked Learning, and COVID-19. Postdigit. Sci. Educ. 2021, 3, 266–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trust, T.; Krutka, D.G.; Carpenter, J.P. “Together We Are Better”: Professional Learning Networks for Teachers. Comput. Educ. 2016, 102, 15–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lantz-Andersson, A.; Lundin, M.; Selwyn, N. Twenty Years of Online Teacher Communities: A Systematic Review of Formally-Organized and Informally-Developed Professional Learning Groups. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2018, 75, 302–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fancera, S.F. School Leadership for Professional Development: The Role of Social Media and Networks. Prof. Dev. Educ. 2020, 46, 664–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stéphan, V.-L.; Joaquin, U.; Soumyajit, K.; Gwénaël, J. Educational Research and Innovation Measuring Innovation in Education 2019 What Has Changed in the Classroom? OECD Publishing: Washington, DC, USA, 2019; ISBN 926431167X. [Google Scholar]

- De Menezes, S.; Premnath, D. Near-Peer Education: A Novel Teaching Program. Int. J. Med. Educ. 2016, 7, 160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tour, E. Teachers’ Self-Initiated Professional Learning through Personal Learning Networks. Technol. Pedagog. Educ. 2017, 26, 179–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelimarkka, M.; Durall, E.; Leinonen, T.; Dean, P. Facebook Is Not a Silver Bullet for Teachers’ Professional Development: Anatomy of an Eight-Year-Old Social-Media Community. Comput. Educ. 2021, 173, 104269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krutka, D.G.; Carpenter, J.P. Why Social Media Must Have a Place in Schools. Kappa Delta Pi Rec. 2016, 52, 6–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krutka, D.G.; Carpenter, J.P. Enriching Professional Learning Networks: A Framework for Identification, Reflection, and Intention. TechTrends 2017, 61, 246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dede, C.; Jass Ketelhut, D.; Whitehouse, P.; Breit, L.; McCloskey, E.M. A Research Agenda for Online Teacher Professional Development. J. Teach. Educ. 2009, 60, 8–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duncan-Howell, J. Teachers Making Connections: Online Communities as a Source of Professional Learning. Br. J. Educ. Technol. 2010, 41, 324–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, T. Participant Observation of a Teachers’ Online Community during the COVID-19 Pandemic in Georgia. Master’s Thesis, The University of Tartu, Tartu, Estonia, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Jarf, R.S. ESL Teachers’ Professional Development on Facebook during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Eur. J. Educ. Pedagog. 2021, 2, 75–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulla, M.B.; Perales, W.F. Facebook as an Integrated Online Learning Support Application during the COVID19 Pandemic: Thai University Students’ Experiences and Perspectives. Heliyon 2021, 7, e08317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fawns, T. An Entangled Pedagogy: Looking Beyond the Pedagogy—Technology Dichotomy. Postdigital Sci. Educ. 2022, 4, 711–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salmon, G. Learning Innovation: A Framework for Transformation. Eur. J. Open Distance E-Learn. 2014, 17, 220–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fullan, M. (Ed.) Teacher Development and Educational Change; Routledge: London, UK, 2013; ISBN 978-1-315-87070-0. [Google Scholar]

- Fullan, M. The New Meaning of Educational Change; Routledge: London, UK, 2001; ISBN 0-203-98656-3. [Google Scholar]

- Ely, D.P. Conditions That Facilitate the Implementation of Educational Technology Innovations. J. Res. Comput. Educ. 1990, 23, 298–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biesta, G.; Tedder, M. Agency and Learning in the Lifecourse: Towards an Ecological Perspective. Stud. Educ. Adults 2007, 39, 132–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priestley, M.; Biesta, G.; Robinson, S. Teacher Agency: An Ecological Approach; Bloomsbury Publishing: London, UK, 2015; ISBN 978-1-4725-2587-1. [Google Scholar]

- Ryberg, T.; Sinclair, C.; Bayne, S.; de Laat, M. (Eds.) Research, Boundaries, and Policy in Networked Learning; Springer International Publishing: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2016; ISBN 978-3-319-31128-9. [Google Scholar]

- Networked Learning Editorial Collective (NLEC) v. hodgson@ lancaster. ac. uk. Networked Learning: Inviting Redefinition. Postdigital Sci. Educ. 2021, 3, 312–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jandric, P. The Methodological Challenge of Networked Learning: (Post)Disciplinarity and Critical Emancipation. In Research, Boundaries, and Policy in Networked Learning; Springer International Publishing: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2016; pp. 165–181. ISBN 978-3-319-31128-9. [Google Scholar]

- Biesta, G.; Priestley, M.; Robinson, S. The Role of Beliefs in Teacher Agency. Teach. Teach. 2015, 21, 624–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bardone, E.; Eradze, M. Theorizing Transformative Educational Technology as a Meso-Related Venture. In Organizational Cognition; Routledge: London, UK, 2022; pp. 99–119. ISBN 1-00-316909-0. [Google Scholar]

- Secchi, D.; Cowley, S.J. Modeling Organizational Cognition: The Case of Impact Factor. J. Artif. Soc. Soc. Simul. 2018, 21, 3628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Secchi, D.; Cowley, S.J. Cognition in Organisations: What It Is and How It Works. Eur. Manag. Rev. 2021, 18, 79–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J.W.; Clark, V.L.P. Designing and Conducting Mixed Methods Research; Sage Publication: Southend Oaks, CA, USA, 2017; ISBN 1-4833-4701-X. [Google Scholar]

- Tavory, I.; Timmermans, S. Abductive Analysis: Theorizing Qualitative Research; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2014; ISBN 978-0-226-18031-1. [Google Scholar]

- Andrews, M.; Squire, C.; Tamboukou, M. Doing Narrative Research. Available online: https://us.sagepub.com/en-us/nam/doing-narrative-research/book238870 (accessed on 17 February 2023).

- Moore, M.G. Theory of Transactional Distance. In Theoretical Principles of Distance Education; Routledge: London, UK, 1997; pp. 22–38. ISBN 978-0-8058-5847-1. [Google Scholar]

- Bardone, E.; Raudsep, A.; Eradze, M. From Expectations to Generative Uncertainties in Teaching and Learning Activities. A Case Study of a High School English Teacher in the Times of COVID-19. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2022, 115, 103723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Secchi, D.; Gahrn-Andersen, R.; Cowley, S.J. (Eds.) Organizational Cognition: The Theory of Social Organizing; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2022; ISBN 978-1-00-316909-3. [Google Scholar]

- Bozkurt, A.; Jung, I.; Xiao, J.; Vladimirschi, V.; Schuwer, R.; Egorov, G.; Lambert, S.R.; Al-Freih, M.; Pete, J.; Olcott, D., Jr.; et al. A Global Outlook to the Interruption of Education due to COVID-19 Pandemic: Navigating in a Time of Uncertainty and Crisis. Asian J. Distance Educ. 2020, 15, 1–126. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Eradze, M.; De Martino, D.; Tinterri, A.; Albó, L.; Bardone, E.; Sunar, A.S.; Dipace, A. After the Pandemic: Teacher Professional Development for the Digital Educational Innovation. Educ. Sci. 2023, 13, 432. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci13050432

Eradze M, De Martino D, Tinterri A, Albó L, Bardone E, Sunar AS, Dipace A. After the Pandemic: Teacher Professional Development for the Digital Educational Innovation. Education Sciences. 2023; 13(5):432. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci13050432

Chicago/Turabian StyleEradze, Maka, Delio De Martino, Andrea Tinterri, Laia Albó, Emanuele Bardone, Ayşe Saliha Sunar, and Anna Dipace. 2023. "After the Pandemic: Teacher Professional Development for the Digital Educational Innovation" Education Sciences 13, no. 5: 432. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci13050432

APA StyleEradze, M., De Martino, D., Tinterri, A., Albó, L., Bardone, E., Sunar, A. S., & Dipace, A. (2023). After the Pandemic: Teacher Professional Development for the Digital Educational Innovation. Education Sciences, 13(5), 432. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci13050432