Distributed Leadership in Irish Post-Primary Schools: Policy versus Practitioner Interpretations

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Theoretical Framework

1.2. Context of Research Study

1.3. Purpose of the Study

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Distribution of Survey

2.2. Participants

2.3. Ethical Approval

2.4. Data Analysis

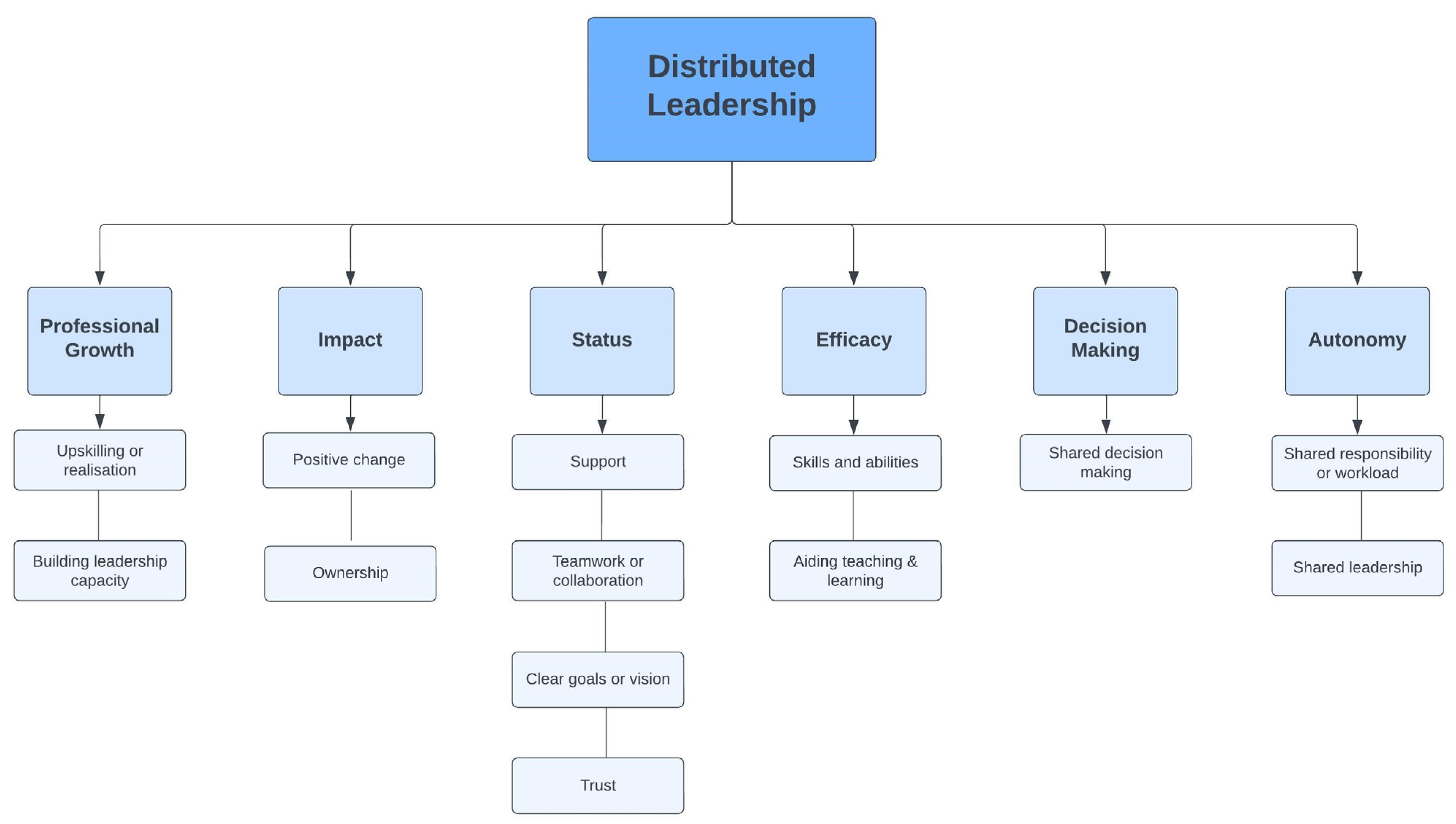

- Decision making;

- Professional growth;

- Status;

- Self-efficacy;

- Autonomy;

- Impact.

2.5. Testing Reliability of Coding

3. Results

3.1. Demographic Characteristics of Participants

3.2. Interpretations of Distributed Leadership

3.2.1. Professional Growth

“Empowering others, regardless of their role, to achieve their potential as leaders”(teacher)

3.2.2. Decision Making

3.2.3. Status

”It is where teachers are given the support, resources and opportunities by existing leaders (dp, principal) to achieve a task”(APII)

“The principal will have enough trust and confidence in his staff to empower them and support them in their endeavours”(teacher)

“Empowering and enabling, without dumping or scapegoating. Providing proper scaffolds and supports, along with clear expectations and agreed outcomes”(principal)

3.2.4. Efficacy

“Giving people the opportunity to lead in their area of expertise”(deputy principal)

3.2.5. Impact

3.2.6. Autonomy

“Getting many members of the school staff involved in running the school and having an input”(APII)

3.2.7. Non-Normative

“More meaningless jargon. Schools are run by people who care about the school. Schools are and should not be treated like businesses”(teacher)

“I know what it should mean! A shared voice which permeates positivity throughout the school body. Fostering supporting and nurturing from the cleaner to the principal and everyone in between creating a vibrant environment. Is that my personal experience… NO”(teacher)

“Hard to say. Theoretically it is sharing responsibility in a formal way & allowing others power & responsibility. In practice it seems a bit like delegation with bells & whistles”(deputy principal)

3.3. Comparison of Interpretations Based on Participants’ Characteristics

4. Discussion

4.1. Discrepancy of Themes/Subthemes

4.1.1. What Is Shared

4.1.2. Who Leadership Is Shared with

4.1.3. How Leadership Is Shared

4.2. Implications for Policy

4.3. Implications for Practice

4.3.1. Short’s Dimensions

4.3.2. Consideration of Context

- How are decisions made most effectively within a school?

- How do leaders involve others in leadership practices?

4.3.3. Situation

4.4. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hairon, S.; Goh, J.W. Pursuing the elusive construct of distributed leadership: Is the search over? Educ. Manag. Adm. Leadersh. 2015, 43, 693–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, N.; Wise, C.; Woods, P.; Harvey, J. Distributed Leadership: A Review of Literature; National College for School Leadership: Nohingham, UK, 2003.

- Spillane, J.P. Distributed leadership. Educ. Forum 2005, 69, 143–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, A. Distributed leadership and school improvement: Leading or misleading? Educ. Manag. Adm. Leadersh. 2004, 32, 11–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spillane, J.P.; Halverson, R.; Diamond, J.B. Investigating school leadership practice: A distributed perspective. Educ. Res. 2001, 30, 23–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gronn, P. Distributed leadership as a unit of analysis. Leadersh. Q. 2002, 13, 423–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crawford, M. Solo and shared leadership. Princ. Educ. Leadersh. Manag. 2019, 3, 57–72. [Google Scholar]

- Bolden, R. Paradoxes of Perspective. In Leadership Paradoxes: Rethinking Leadership for an Uncertain World; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2016; Volume 31. [Google Scholar]

- Youngs, H. Distributed Leadership. In Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Education; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Harris, A. Distributed leadership: Implications for the role of the principal. J. Manag. Dev. 2011, 31, 7–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, A.; Jones, M. COVID 19–School leadership in disruptive times. Sch. Leadersh. Manag. 2020, 40, 243–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azorín, C.; Harris, A.; Jones, M. Taking a distributed perspective on leading professional learning networks. Sch. Leadersh. Manag. 2020, 40, 111–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lumby, J. Distributed leadership and bureaucracy. Educ. Manag. Adm. Leadersh. 2019, 47, 5–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartley, D. Paradigms: How far does research in distributed leadership ‘stretch’? Educ. Manag. Adm. Leadersh. 2010, 38, 271–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crawford, M. Solo and distributed leadership: Definitions and dilemmas. Educ. Manag. Adm. Leadersh. 2012, 40, 610–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diamond, J.B.; Spillane, J.P. School leadership and management from a distributed perspective: A 2016 retrospective and prospective. Manag. Educ. 2016, 30, 147–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, A. Distributed leadership: According to the evidence. J. Educ. Adm. 2008, 46, 172–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, L. Reflective Practice in Educational Research; Continuum: London, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Evans, L. Developing research capacity in the social sciences: A professionality based model. Int. J. Res. Dev. 2009, 1, 134–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, L. Is leadership a myth? A ‘new wave’critical leadership-focused research agenda for recontouring the landscape of educational leadership. Educ. Manag. Adm. Leadersh. 2022, 50, 413–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, S. Can we all agree? Building the case for symbolic interactionism as the theoretical origins of public relations. J. Prof. Commun. 2015, 4, 49–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blumer, H. Symbolic Interactionism; Prentice-Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1969; Volume 9. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, B. Social constructivism. Emerg. Perspect. Learn. Teach. Technol. 2001, 1, 16. [Google Scholar]

- Aksan, N.; Kısac, B.; Aydın, M.; Demirbuken, S. Symbolic interaction theory. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2009, 1, 902–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Department of Education and Skills. Looking at Our School 2016: A Quality Framework for Post-Primary Schools; Department of Education and Skills: Dublin, Ireland, 2016.

- Department of Education. Looking at Our School 2022: A Quality Framework for Post-Primary Schools; Department of Education: Dublin, Ireland, 2022.

- Barrett, A.; Joyce, P. Leadership and Management in Post-Pimary Schools; Department of Education and Skills: Dublin, Ireland, 2018; pp. 1–30.

- Lárusdóttir, S.H.; O’Connor, E. Distributed Leadership and Middle Leadership Practice in Schools: A Disconnect? Ir. Educ. Stud. 2017, 36, 423–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Donovan, M. The challenges of distributing leadership in Irish post-primary schools. Int. Electron. J. Elem. Educ. 2017, 8, 243–266. [Google Scholar]

- Bennett, N.; Harvey, J.; Wise, C.; Woods, P. Distributed Leadership: A Desk Study; NCSL: Nottingham, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Hickey, N.; Flaherty, A.; Mannix McNamara, P. Distributed Leadership: A Scoping Review Mapping Current Empirical Research. Societies 2022, 12, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timperley, H.S. Distributed leadership: Developing theory from practice. J. Curric. Stud. 2005, 37, 395–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Thematic Analysis; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Short, P.M. Defining teacher empowerment. Education 1994, 114, 488–493. [Google Scholar]

- Muijs, D.; Harris, A. Teacher leadership—Improvement through empowerment? An overview of the literature. Educ. Manag. Adm. 2003, 31, 437–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, H.M.; Yangaiya, S.A. Distributed Leadership and Empowerment Influence on Teachers Organizational Commitment. Acad. J. Interdiscip. Stud. 2015, 4, 73–84. [Google Scholar]

- MacPhail, C.; Khoza, N.; Abler, L.; Ranganathan, M. Process guidelines for establishing intercoder reliability in qualitative studies. Qual. Res. 2016, 16, 198–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lombard, M.; Snyder-Duch, J.; Bracken, C.C. Content analysis in mass communication: Assessment and reporting of intercoder reliability. Hum. Commun. Res. 2002, 28, 587–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallinger, P.; Heck, R.H. Reassessing the principal’s role in school effectiveness: A review of empirical research, 1980–1995. Educ. Adm. Q. 1996, 32, 5–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gronn, P. Distributed properties: A new architecture for leadership. Educ. Manag. Adm. 2000, 28, 317–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- French, J.; Raven, B. The Bases of Social Power; Institute for Social Research, University of Michigan: Ann Arbor, MI, USA, 1959. [Google Scholar]

- Mannix-McNamara, P.; Hickey, N.; MacCurtain, S.; Blom, N. The dark side of school culture. Societies 2021, 11, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourdieu, P. Social space and symbolic power. Sociol. Theory 1989, 7, 14–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, A. Teacher leadership and school improvement. In Effective Leadership for School Improvement; Routledge: London, UK, 2003; pp. 72–83. [Google Scholar]

- Torrance, D. Distributed leadership: Challenging five generally held assumptions. Sch. Leadersh. Manag. 2013, 33, 354–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oppi, P.; Eisenschmidt, E.; Jõgi, A.-L. Teacher’s readiness for leadership–a strategy for school development. Sch. Leadersh. Manag. 2022, 42, 79–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silcox, S.; Boyd, R.; MacNeill, N. The myth of distributed leadership in modern schooling contexts: Delegation is not distributed leadership. Aust. Educ. Lead. 2015, 37, 27–30. [Google Scholar]

- Lahtero, T.J.; Lång, N.; Alava, J. Distributed leadership in practice in Finnish schools. Sch. Leadersh. Manag. 2017, 37, 217–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, A. Teacher leadership as distributed leadership: Heresy, fantasy or possibility? Sch. Leadersh. Manag. 2003, 23, 313–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klar, H.W.; Huggins, K.S.; Hammonds, H.L.; Buskey, F.C. Fostering the capacity for distributed leadership: A post-heroic approach to leading school improvement. Int. J. Leadersh. Educ. 2016, 19, 111–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kouzes, J.M.; Posner, B.Z. The Leadership Challenge: How to Keep Getting Extraordinary Things Done in Organizations; Jossey Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Emerson, B.; Lewis, K. Navigating Polarities: Using both/and Thinking to Lead Transformation; Paradoxical Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2019; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Mayrowetz, D. Making sense of distributed leadership: Exploring the multiple usages of the concept in the field. Educ. Adm. Q. 2008, 44, 424–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lumby, J. Distributed leadership: The uses and abuses of power. Educ. Manag. Adm. Leadersh. 2013, 41, 581–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, J.; Smylie, M.; Mayrowetz, D.; Louis, K.S. The role of the principal in fostering the development of distributed leadership. Sch. Leadersh. Manag. 2009, 29, 181–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spillane, J.P.; Diamond, J.B. Distributed Leadership in Practice; Teachers College, Columbia University: New York, NY, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Katzenmeyer, M.; Moller, G. Awakening the Sleeping Giant: Helping Teachers Develop as Leaders; Corwin Press: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Harris, A.; Muijs, D. Improving Schools Through Teacher Leadership; Open University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Harris, A.; Lambert, L. Building Leadership Capacity for School Improvement; Open University Press: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Liontos, L.B.; Lashway, L. Shared Decision-Making. In School Leadership: Handbook for Excellence; Smith, S.C., Piele, P.K., Eds.; ERIC Clearinghouse on Educational Management: Eugene, OR, USA, 1997; pp. 226–250. [Google Scholar]

- Drysdale, L.; Gurr, D. Leadership in uncertain times. Int. Stud. Educ. Adm. 2017, 45, 131–159. [Google Scholar]

| Professional Growth | |

| Short’s (1994) definition | “As a dimension of empowerment, professional growth refers to teachers’ perceptions that the school in which they work provides them with opportunities to grow and develop professionally, to learn continuously, and to expand one’s own skills through the work life of the school” [34]. |

| Modified definition | Professional growth refers to the provision of opportunities for school personnel to grow and develop professionally, to learn continuously, and to expand one’s own skills through the work life of the school. |

| Decision making | |

| Short’s (1994) definition | “This dimension of empowerment relates to the participation of teachers in critical decisions that directly affect their work” [34]. |

| Modified definition | Decision making refers to the participation of school personnel in decisions that directly affect their work. |

| Status | |

| Short’s (1994) definition | “Status as a dimension of empowerment refers to teacher perceptions that they have professional respect and admiration from colleagues” [34]. |

| Modified definition | Status refers to the presence of professional respect and admiration among school personnel. |

| Self-efficacy | |

| Short’s (1994) definition | “Self-efficacy refers to teachers’ perceptions that they have the skills and ability to help students learn, are competent in building effective programs for students, and can effect changes in student learning” [34]. |

| Modified definition | Efficacy refers to school personnel having the skills and abilities to help students learn, build effective programs for students, and effect changes in student learning. |

| Impact | |

| Short’s (1994) definition | “Impact refers to teachers’ perceptions that they have an effect and influence on school life” [34]. |

| Modified definition | Impact refers to school personnel having an effect and influence on school life. |

| Autonomy | |

| Short’s (1994) definition | “Autonomy, as a dimension of empowerment, refers to teachers’ beliefs that they can control certain aspects of their work life” [34]. |

| Modified definition | Autonomy refers to school personnel controlling certain aspects of their work life. |

| Demographics | Percentage (%) | Number of Participants (n) |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 25 | 89 |

| Female | 74 | 270 |

| Did not specify | <1 | 4 |

| Age | ||

| 20–30 years | 14 | 52 |

| 31–40 years | 30 | 108 |

| 41–50 years | 39 | 143 |

| 51+ years | 16 | 58 |

| Did not specify | <1 | 2 |

| Highest level of qualification | ||

| Undergraduate degree | 13 | 47 |

| Postgraduate certificate | 4 | 16 |

| Postgraduate diploma | 29 | 106 |

| Masters | 51 | 184 |

| Doctorate | 2 | 7 |

| Did not specify | <1 | 3 |

| Role | ||

| Class teacher | 36 | 131 |

| Guidance Counsellor | 2 | 7 |

| Special Needs Assistant | 8 | 30 |

| AP I | 20 | 74 |

| AP II | 18 | 65 |

| Deputy Principal | 7 | 27 |

| Principal | 7 | 27 |

| Did not specify | <1 | 2 |

| Number of years working in a school | ||

| <5 years | 16 | 57 |

| 6–15 years | 35 | 126 |

| 16–25 years | 36 | 130 |

| >25 years | 13 | 48 |

| Did not specify | <1 | 2 |

| Worked in a previous school | ||

| Yes | 76 | 277 |

| No | 23 | 84 |

| Did not specify | <1 | 2 |

| School type | ||

| Voluntary secondary schools | 46 | 167 |

| Vocational/ETB schools or colleges | 32 | 115 |

| Community or comprehensive schools | 17 | 62 |

| Other schools | 5 | 19 |

| School location | ||

| Urban | 44 | 158 |

| Suburban | 26 | 96 |

| Rural | 30 | 108 |

| Did not specify | <1 | 1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hickey, N.; Flaherty, A.; Mannix McNamara, P. Distributed Leadership in Irish Post-Primary Schools: Policy versus Practitioner Interpretations. Educ. Sci. 2023, 13, 388. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci13040388

Hickey N, Flaherty A, Mannix McNamara P. Distributed Leadership in Irish Post-Primary Schools: Policy versus Practitioner Interpretations. Education Sciences. 2023; 13(4):388. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci13040388

Chicago/Turabian StyleHickey, Niamh, Aishling Flaherty, and Patricia Mannix McNamara. 2023. "Distributed Leadership in Irish Post-Primary Schools: Policy versus Practitioner Interpretations" Education Sciences 13, no. 4: 388. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci13040388

APA StyleHickey, N., Flaherty, A., & Mannix McNamara, P. (2023). Distributed Leadership in Irish Post-Primary Schools: Policy versus Practitioner Interpretations. Education Sciences, 13(4), 388. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci13040388