Abstract

(1) In this study, we analyse the impact that research and practice orientation offered at university (first phase) have on theory application and teaching quality in an in-service training programme (second phase). The connection between these two phases has been poorly examined. Therefore, we examine this connection using a longitudinal study. (2) The analysis is based on data from 1417 pre-service and later student teachers who participated in the German National Educational Panel Study (NEPS). (3) The results show that meaningful research and practice orientation experienced in the first phase contribute to greater theory application and teaching quality in the second phase. (4) The study thus shows that theory application is a resource for supporting teaching quality.

1. Introduction

German teacher education is organised into a structured two-phase model. However, the connection between the phases has been poorly investigated. Little is known about the effects of the academic teacher education conducted at universities on practical oriented in-service training programmes, as well as the development of theory application and the relevance of research orientation and practice orientation on professional development in in-service programmes. From the perspective of evidence-based pedagogy, theory application is a way of connecting scientific knowledge with school practice, ensuring competent teaching quality [1,2]. It can be viewed as a task that beginning teachers should be prepared for before entering the workplace. In this section, we briefly explain the consecutive structure of German teacher education, which is characterised by a highly structured, two-phase model that aims to provide a best practice approach for pre-service teachers.

The first phase takes place at universities, during which pre-service teachers receive their master’s degree, which is necessary to enter the second phase of teacher education. The duration of academic teacher education at university is usually ten semesters, and the curriculum and formal requirements for a Master of Education degree for federal states, school types, and subjects are similar (see [3] for an in-depth description). The acquisition of research-oriented pedagogical knowledge, pedagogical content knowledge, and content knowledge [4] is central to the first phase of teacher training [5,6,7]. However, while learning opportunities (seminars and lectures) at university should be oriented more towards research, some level of practice orientation is also essential, as the main aim of academic teacher education is not only to foster academic learning but also to prepare future teachers for school practice in the second phase of teacher education [8,9,10,11]. A crucial part of the preparation for school practice is evidence-based teaching, as teaching should be based on research findings and theories rather than on beliefs and opinions [1,12]. Learning opportunities in the first phase of teacher education should prepare pre-service student teachers for evidence-based teaching in the second phase. For this to happen, certain orientations are needed, which are described in the structure, support, challenge, and orientation (SSCO) approach [13,14,15]. According to this approach, the three central orientations to ensure a high-quality first phase of teacher education are research orientation, practice orientation, and meaning orientation.

This call for meaningful research and practice-oriented teacher education at university is in line with international considerations of evidence-based initial teacher education. Shavelson [16] argues that teachers should link research to practice in order to cope with school demands. Thus, teacher education programmes must prepare pre-service teachers properly [17,18,19]. This goes hand in hand with the need for pre-service teachers to learn to use research results in practice during their studies at university and later through in-service training [20]. A study by Groß-Ophoff et al. [21] showed that this approach leads to higher job performance, as students at research-informed schools perform better on performance assessments.

Research orientation is a relatively broad and general concept that includes a subject-specific understanding of the theory and development of scientific knowledge, the use and limitations of scientific methods, the development of research questions, and the research process itself [22]. In the context of teacher education, pre-service teachers can be said to be learning about the use and interpretation of scientific evidence, theories, and methods and at least an exemplified research process [23,24]. Research orientation describes the extent to which evidence is addressed during a course of study and how often students are exposed to research results [23]. This includes discussions of current evidence by lecturers, as well as an introduction to research methods [24]. For example, in a research-oriented seminar or lecture, students learn about the current findings of cognitive load theory.

Practice orientation extends this spectrum by enriching university teaching with elements of the professional world. It is important for courses to contribute to the link between theory and practice [24]. Practical professional skills should also be taught. Lesson planning, grading, and classroom management, for example, are relevant topics for teaching or practice, and to solve and successfully implement them, teachers must rely on theoretical knowledge. Recent research has shown that instruction on research and practice orientation is constant over different semesters in the first phase of teacher education (d = −0.06–0.05 [25]). As an example, teaching about the concept of classroom management can be understood as practice orientation.

Schaeper and Weiß [24] used the term ‘meaning orientation’ to refer to the product of research reflection and practice orientation. Whenever academic knowledge is taught without explicitly reflecting on its implications and relevance, learning opportunities are missed. Whereas research and practice orientation highlight what should be taught to pre-service teachers at university (e.g., theories on learning and development; research on teaching effectiveness), meaning orientation is a cognitive process on the part of students themselves and refers to how this knowledge can be transmitted into practice (e.g., [26]). Meaning orientation thus implies that higher cognitive processes of understanding are activated and that knowledge is not superficial. Accordingly, with regard to the connection between research and practice, meaning-oriented learning aims at higher taxonomies, so that research and practice will be connected in a sustainable way. This can be illustrated by looking at the two examples above. Meaning orientation signifies that seminars or lectures clarify what the concept of classroom management and findings on cognitive load theory mean for schoolwork. Indeed, it is unclear how the first phase of teacher education (described by research and practice orientation) is empirically connected to the second phase.

The second phase of teacher education involves an in-service training programme, where student teachers enrol in a teaching seminar and concurrently begin working at a school, during which they are expected to put the knowledge they acquired in the first phase of teacher education into action [9]. In other words, the second phase requires students to build on the knowledge from the first phase [5]. The duration of in-service training programmes ranges from 16 to 24 months, although it is 18 months in most federal states [27]. This phase is characterised by deep immersion into school practice [28]. In fact, student teachers will teach a considerable number of hours on their own—129 to 360 h over the entire in-service training programme [29]. Additionally, student teachers receive structured supervision from a senior teacher at the school and from teaching seminars (during scheduled visits). In the second phase, student teachers are monitored and trained in practice to develop the necessary teaching skills (fostering teaching quality), supposedly based on applied theory [3]; however, student teachers do not always refer to theories [30,31]. Hargreaves [32] pointed out that teachers engage in tinkering, consisting of subjective theories, beliefs, and experiences that might seem epistemically contrary to well-founded theoretical and scientific knowledge, which is considered more trustworthy (e.g., [33]). Tinkering is a dynamic and theory-free way of solving problems. It tends to emerge from the practice itself, in that solutions are tried and opinions are sought from others to get problems under control (e.g., [31]). When student teachers tinker to solve a disciplinary problem in the classroom, they ‘invent’ and try out possible ways to deal with the problem and resolve it in their own way, whether or not doing so leads to a desired result. Theory application means, for example, that students take up Kounins’s [34] ideas on classroom management and attempt to apply them to prevent interruptions. Because student teachers lack solid experience, theory application can be regarded as a more elaborate starting point for professional development than tinkering [1]. Tinkering, like theory application, can thus be seen as a way of planning pedagogical action in practice. However, tinkering tends to be ‘theory free’. It should be noted that teachers in practice do both. They not only tinker but also apply theories, although theories are no practical guide for practice (e.g., [35]). Theories never fit exactly into practice, and they often need to be adapted, ideally within a supervised and reflective learning process. Consequently, tinkering, therefore, must be considered alongside theory application as a resource to help ensure teaching quality.

While this two-phase model has a decade-long tradition and has undergone several adaptions [36], ensuring a successional and sustainable learning process between the first and second phases is still challenging, as two different and structurally separate institutions with different objectives are involved [29]. Zeichner [37] noted that there is a lack of connection between the -based and practical parts of teacher education. This issue should be addressed by better linking the two elements [38]. Strategies for doing this include mediated instruction and field experiences [37,39]. Whereas universities should deliver theory- and research-oriented knowledge that is relevant for practice in a meaning-oriented way, in-service training programmes should qualify students for professional practice by ensuring that research-oriented knowledge is connected to experiences in the classroom. In other words, research knowledge needs to be linked to practical experience [37]. From our theoretical perspective, there are several such links, including (1) meaning orientation in the first phase of teacher education and (2) theory application and tinkering in the second phase of teacher education.

However, the extent to which university-based learning is used as a resource for school practice in in-service training programmes has not been empirically clarified, and neither has the extent to which teaching seminars ensure that scientific knowledge is a resource for the development of in-school teaching practice.

The consecutive nature and the assembled structure of the German model have been criticised for lacking a sustainable connection between the two phases [28]. However, the state of research on this issue is currently thin. Future teachers often perceive academic knowledge as useless and not meaningful for their teaching [40]. Some argue that teaching can actually only be learned through practice. Pre-service and student teachers sometimes even feel that their instructors devalue theory during the second phase of teacher education [41].

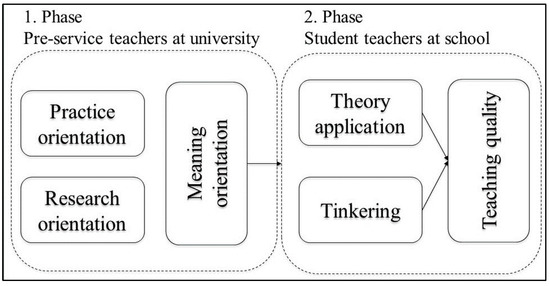

In this study, we investigate whether the connection between research and practice orientation acquired during the first phase of teacher education and theory application and tinkering acquired during the second phase can explain the teaching quality in schools (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

A simplified frame model on theory and practice within the two-phase training model of teacher education in Germany.

For research and practice orientation acquired during the first phase to be perceived as useful in the second phase, we refer to meaning orientation as a mediating variable. In this study, we investigate the connection between both phases in a longitudinal study. We investigate empirically what effects the first phase has on the second phase of teacher education.

2. Research, Practice, and Meaning Orientation in the First Phase of German Teacher Training

As stated above, the first phase of teacher education focuses mainly on research and practice orientation, but it also offers opportunities to learn about its relevance—so-called meaning orientation (e.g., [12]). In the following section, we present what is known empirically about research and practice orientation in teacher education.

Recent studies show that even if pre-service teachers report positive attitudes towards research and theory and assess research-based and theoretical knowledge as reliable, they do not necessarily implement it in practice [42,43]. Furthermore, research-based and theoretical knowledge of teaching and learning may be seen as appropriate for explaining phenomena but not necessarily used for practical application [44]. Bråten and Ferguson [45] concluded that pre-service teachers seem to believe more in practically driven knowledge than in theory-based knowledge of school practice. Such teachers seem to have less motivation for learning scientific knowledge and perceive research as dissociated from practice [46,47,48]. Farley-Ripple et al. [49] and Williams and Coles [50] found that even if teachers draw practical implications from research results, those implications are often limited by their information literacy. Hartung-Beck and Schlag [51] analysed the teaching diaries of student teachers during practical training conducted during the first phase of teacher training and showed that, in most cases, pre-service teachers only reflect school practice superficially. This is true even when they receive instructional support in reflection. Another study presented a slightly different picture, showing that when pre-service teachers are trained in arguing, they connect research findings from multiple sources with school practice [52]. However, student teachers still provide mostly one-sided arguments when using research-based knowledge to explain practice [53]. In contrast to Hendriks et al. [44], other studies have shown that when teachers reflect on school practice, they often discard research findings in favour of subjective theories [30,54]. This paints a picture in which the research-oriented reflection of practice remains difficult for teachers [55,56], and the effects of this difficulty are unclear.

2.1. Theory Application, Tinkering, and Teaching Quality in the Second Phase of German Teacher Training

To improve practice-oriented learning during the second phase of pedagogical education, in-service student teachers should rely on their knowledge acquired during the first phase by applying theory to solve practical problems [57]. Beck and Krapp [58] distinguished four basic forms of theory application:

Goal attainment. Theories offer implications for interventions at school. For example, a theory or theoretical model for classroom management may outline behaviours that might help teachers avoid interruptions during lessons.

Prediction. Theories can be used to predict phenomena. For example, if a teacher is omnipresent in the classroom, it can be expected that the lesson will be less subject to disruption.

Explaining. Theories can have explanatory potential. For example, aggression can be explained by the frustration–aggression hypothesis [59].

Description. Observation can be more productive when guided by theories. This can be illustrated by Kounin’s [34] example of classroom management, according to which it is hard to identify ‘withitness’ without knowledge of classroom management.

Theories, therefore, can not only offer a theoretical understanding of a phenomenon and provide the vocabulary to describe it but, if successfully applied in practice, also be helpful for actually solving practical problems. Klein et al. [60,61] showed that pre-service teachers have difficulty applying theories to correct mistakes. Errors indicate that something does not work and enables a comparison with the correct solutions. This process is called elaboration [62,63]. The findings of Klein et al. [60,61] suggest that pre-service teachers apply theories inadequately and, therefore, no elaboration of school practice occurs. However, the studies did not examine whether theory application is relevant to teaching quality. In this context, we understand teaching quality as the ability of student teachers to realise high-quality instruction in the classroom. Such instruction is based on classroom management, student support, and cognitive activation [64]. Correlative findings on teachers’ pedagogical knowledge and their quality of teaching indicate that theories make a positive contribution to practice [7,65,66,67,68,69].

2.2. Research Questions and Hypotheses

In the German teacher training programme, knowledge acquired during the first phase of teacher education is expected to be both research- and practice-oriented. Further, it is expected that this knowledge will be used to plan and conduct lessons during the second phase of in-service teacher training, resulting in less tinkering, more theory application, and high teaching quality. However, receiving theoretical and evidenced-based academic knowledge and sustainable opportunities and discussing the practical relevance might not be enough to foster teaching quality. Reflection on academic knowledge and an understanding of its meaningfulness might be necessary to increase the likelihood that student teachers will rely on the knowledge they have acquired in the first phase and further develop their teaching competencies in the second phase.

To the best of our knowledge, no other study has used a longitudinal design to investigate the relationship between meaningful research and practice orientation, as perceived during the academic phases of teacher education, and their effect on theory application, tinkering, and the quality of teaching in an in-service training programme. We, therefore, seek to fill this research gap.

The first research question addresses relationships between perceived research orientation, practice orientation, and meaning orientation during the first phase of teacher education:

RQ1. What impact do research orientation and practice orientation have on meaning orientation?

We assume positive associations between all three variables:

H1.

Since research orientation can be seen as central to the first phase of teacher education, we further assume that the impact on meaning orientation will be greater for research orientation than for practice orientation.

In the next step, we analyse relationships between theory application, tinkering, and teaching quality in the second phase of teacher education.

RQ2. What impact do theory application and tinkering have on teaching quality?

Our second hypothesis is as follows:

H2.

Since theories are considered veridical, we expect theory application to have a stronger influence on teaching quality than tinkering.

Finally, we analyse the effects of perceived research orientation and practice orientation on the use of tinkering and theory application and the role of perceived meaningfulness.

RQ3. Based on the assumption that reflection, evaluation research, and practice orientation have little connection to practice, we assume that meaning orientation functions as a mediator.

To answer our third research question, we test three hypotheses:

H3.

Research orientation and practice orientation are positively related to theory application and tinkering. Because of the two different approaches to coping with practice, we assume that research orientation predicts theory application and practice orientation predicts tinkering.

H4.

Meaning orientation has direct effects on theory application and tinkering.

H5.

Meaning orientation mediates the effects of theory and practice orientation on theory application and tinkering.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Sample

The analysis uses data from a panel of pre-service and student teachers in starting cohort 5 of the National Educational Panel Survey (NEPS; [70]). We merged the data of 1417 student teachers (79% female; Mage = 29.24, SDage = 2.47) in in-service training programmes with their assessments of learning opportunities at university as pre-service teachers. Consequently, two measurement points were analysed, the first of which (t1) was in the first phase of teacher education (i.e., university). Here, the research and practice orientation of the learning opportunities was assessed. At the same time, the meaning orientation of the study programme was recorded. The pre-service teachers were enrolled at university, the first phase of teacher education, at the time. Measurement point two (t2) took place in the second phase of teacher education (i.e., the in-service training programme). At this point, the student teachers answered items on theory application in a teaching seminar and assessed their teaching quality. Cases with missing values were omitted. All participants were becoming secondary teachers. Before entering the in-service training programmes, all participants acquired a ten-semester master’s degree or an equivalent state exam. The data were collected by the NEPS by telephone and online interviews. The NEPS also anonymised the interview data.

3.2. Variables and Procedure

The items of t1 were assessed by the pre-service teachers themselves. Scores for all items ranged from 1 (low expression) to 5 (high expression) and were compiled in German (see Appendix A).

3.2.1. Research, Practice, and Meaning Orientation

This scale is part of the orientation dimension of the SSCO model by Bäumer et al. [23]. It measures shared values and norms regarding research, practice, and meaning in higher education [14]. Schaeper and Weiß [24] adapted and validated the instrument for the NEPS. The scale was assessed in multiple waves during the first phase of teacher training. The first assessment was conducted with first-year students at the end of 2011 via an online survey [71]. The measures were repeated in the fifth and seventh semesters. The degree programme had a standard duration of 10 semesters (i.e., 5 years). The sample was affected by significant panel attrition over different waves (see Appendix C). Because research and practice orientation show less variation in teacher education [25], we jointly scaled research and practice orientation across all waves. To validate this, we computed different models for different waves, achieving similar results (see Appendix C).

The items in t2 were assessed by the student teachers in in-service training programmes (see Appendix B). The theory application scale ranged from 1 (low expression) to 4 (high expression). Measures of teaching quality used a Likert scale ranging from 1 (low expression) to 5 (high expression). Both were compiled in German. The following sections describe the scales.

3.2.2. Theory Application and Tinkering

Both scales were adapted by the NEPS for the second phase of teacher training but stem from Kunter et al. [72] and Kunina-Habenicht et al. [73]. Both were developed to assess discourse and reflection in teacher seminars. Data collection was performed by computer-assisted telephone interviews [71]. Both scales were assessed once in the in-service training programme. We used four waves of student teachers—from 2015, 2016, 2017, and 2018. These waves were used to merge with the assessments from the first phase of teacher education individually. It should be noted that measures from the second phase suffered less from panel attrition than measures from the first phase, even though they were later events. This can be explained by the sampling strategy of the NEPS. Measures from the second phase of teacher training belonged to the telephone sampling wave (CATI). The scales about university learning opportunities were part of the online sampling wave (CAWI). Therefore, some students left the panel in the online sampling wave but re-entered as student teachers in the telephone sampling wave, as all originally sampled students were called by telephone.

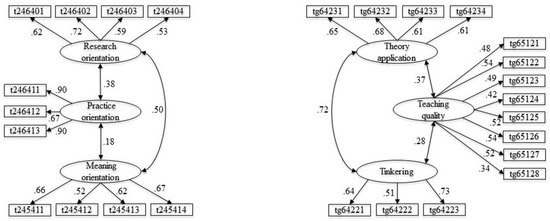

3.2.3. Teaching Quality

We used the scale on designing conducive learning situations, motivation, and providing transfer options developed by Weresch-Deperrois et al. [74] as an indicator of teaching quality. The measure was performed at the same time as the theory application and tinkering scale. In preparation for the analyses, we calculated the internal consistency of all scales in the first step. Appendice A and Appendice B show Cronbach’s alpha values for internal consistency, which were in the (lower) acceptable range (α = 0.64–0.84) (e.g., [75]). As a second step, we conducted a confirmatory factor analysis to ensure construct validity at all measurement points. The factor loadings are shown in Figure 2 (0.33–0.90). All items were used in the same model, and for clarity, we split the figures for t1 and t2. We interpreted the results to indicate acceptable construct validity for theoretical assumptions about the constructs (e.g., [76]).

Figure 2.

Measurement model with CFA (N = 1417, RMSEA = 0.05, CFI = 0.91, TLI = 0.90).

Additionally, a correlation table is provided in Appendix C. It should be noted, however, that the dimensionality of teaching quality is not uncontested. Models with three or more dimensions have been used to describe teaching quality, although with varying results [77]. The extent to which teaching quality is subject-specific or generic is also unclear [78]. As our aim was to examine teaching quality in the second phase of teacher education in Germany, we stuck to a more generic approach that better suits teacher education. Weresch-Deperrois et al. [74] developed an instrument that captures the extent to which the standards of German teacher education (e.g., [79]) are met in lessons. To do so, the instrument measures how ‘elaborate’ teaching is. Elaborate teaching quality consists of conductive learning situations, motivated learners, and providing transfer options [77], which are also central dimensions of different teacher quality models.

3.3. Analysis

The research and practice orientation assessments at t1 were correlated in the model as assessments of (either the same or different parts of) the content of university learning opportunities. We do not propose a direction here, as there is no theoretical perspective whereby they affect each other. The situation is different with meaning orientation, however. Research orientation and practice orientation may well have an impact on the meaning that students ascribe to academic knowledge. Therefore, we linked meaning orientation to research and practice orientation using a regression path. In addition, meaning orientation was linked to teaching quality. We did not expect an effect here because meaning orientation should be a mediator through tinkering and theory application. Meaning orientation in t1 should explain the theory application—and to some degree, tinkering—in the in-service training programme (t2). In our opinion, meaning orientation is the link between research and practice orientation learned at university and theory application and tinkering during the in-service training programme. Theory application and tinkering are also correlated since prospective teachers can (or should) do both things at the same time, as they are different but possibly simultaneously usable forms of problem-solving. However, both should explain teaching quality in specific and different ways via regression. For the same reason, we omitted the path from meaning orientation and teaching quality. The interpretation of the calculated standardised β-coefficients was based on Cohen’s [80] effect size measures (β ≥ 0.10 = small, β ≥ 0.30 = medium, β ≥ 0.50 = large). Stata 13.1 was used to merge data from t1 and t2, and a latent analysis was performed with Mplus 6.11.

4. Results

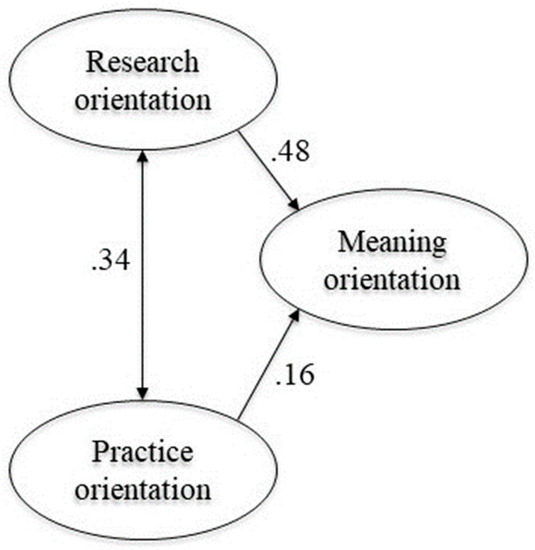

4.1. What Impact Do Research and Practice Orientation Have on Meaning Orientation?

To address our first research question (what impact does research and practice orientation have on meaning orientation?), we tested hypothesis H1 (the impact of research orientation being greater than the impact of practice orientation on meaning orientation). In teacher education at university, practice orientation had a small but significant effect on meaning orientation (β = 0.16), but research orientation had a larger effect on meaning orientation (β = 0.48; see Figure 3).

Figure 3.

The effects of research and practice orientation in the first phase of teacher education (N = 1417, RMSEA = 0.10, CFI = 0.89, TLI = 0.85, all effect sizes are significant (p < 0.01)).

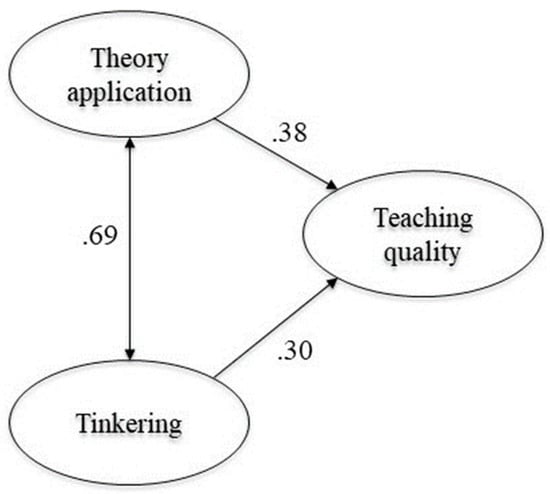

4.2. What Impact Do Theory Application and Tinkering Have on Teaching Quality?

In the next step, we analysed the impact of theory application and tinkering on teaching quality. Based on H2, we expected a stronger influence of theory application on teaching quality than tinkering. The results shown in Figure 4 support this assumption to some degree. Tinkering significantly affected teaching quality (β = 0.30). This was also the case for theory application (β = 0.38), although both effects were of a medium size. We interpreted this as partial support of our hypothesis and, therefore, H2 stands.

Figure 4.

The effects of in-service training programmes on teaching quality (N = 1417, RMSEA = 0.04, CFI = 0.96, TLI = 0.95, all effect sizes are significant (p < 0.01)).

4.3. What Impact Do Meaningful Research and Practice Orientation Have on Theory Application and Tinkering?

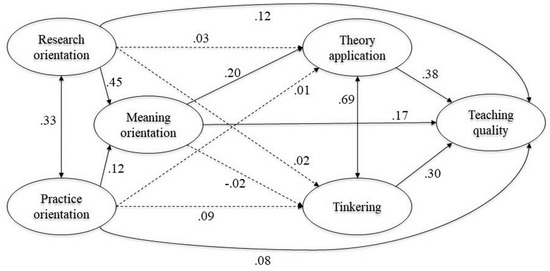

As a final step, we analysed RQ3 (the connection between measures of the first and second phases of teacher education; see Figure 5). In H3, we hypothesised that there is a positive relationship between research orientation and practice orientation with theory application and tinkering. The results did not support this hypothesis. Practice orientation had no significant effect on theory application (β = 0.01) and tinkering (β = 0.09). Research orientation also had no significant impact on theory application (β = 0.03) or tinkering (β = 0.02).

Figure 5.

The effects of learning opportunities at university and in-service training (N = 1417, RMSEA = 0.05, CFI = 0.91, TLI = 0.89, all effect sizes are significant (p < 0.01), dashed paths are not significant).

Next, we tested H4 (meaning orientation has a direct effect on theory application and tinkering). The results are shown in Figure 5 and support H4 to some degree. Meaning orientation had a small significant effect on theory application (β = 0.20) but not on tinkering (β = −0.02). Unexpectedly, meaning orientation had a small direct effect on teaching quality.

Finally, we looked at the expected double mediation of meaning orientation. Hypothesis H5 was supported, as meaning orientation mediated the effects of research orientation (see Figure 5). Small effects of research (β = 0.12) and practice orientation (β = 0.08) on teaching quality remained.

If we track all paths backwards, meaningful research orientation contributed via theory application to teaching quality (see Figure 5). Theory application still had the largest direct effect on teaching quality (β = 0.38), while theory application itself was mostly affected by meaning orientation (β = 0.20), which was affected by research orientation (β = 0.45; see Figure 5. These path coefficients were used to calculate the total effect of research orientation on teaching quality and compare it to the total effect of practice orientation, considering the mediation by meaning orientation and theory application. The total effect of research orientation on teaching quality was (0.45 × 0.20 × 0.38) + (0.45 × 0.17) = 0.11 + 0.12 = 0.23. The total effect of practice orientation on teaching quality was 0.11 = (0.12 × 0.20 × 0.38) + (0.12 × 0.17) + 0.08. This underlines the relevance of meaning orientation and theory application in modelling the professional development of future teachers.

5. Discussion

The following findings emerged from the hypothesis tests. First, research orientation seems to be more important for building meaning than practice orientation in the first phase of teacher training. This also fits in with the state of research, but it still needs some explanation. In the literature review section, it was proposed that while studies have tried to foster the use of evidence for practice, they are still very research-driven. For example, Hartmann et al. [52] fostered the integration of different sources of knowledge to make more accurate decisions in practice. From this point of view, universities must deliver different sources of knowledge and ensure that those sources are research-oriented. As a next step, this research-oriented knowledge is reflected to generate meaningful practical implications. Similarly, Klein et al. [60,61] found that pre-service teachers are trained in correcting mistakes in practice with theories, but they do not correct ‘real’ practice mistakes. They train theory application but do not elaborate on classroom practice. This underscores Neuweg’s [81] argument that the academic content of university teacher education should remain at the core of teaching education through science.

Second, theory articulation in practice during in-service training programmes (the second phase of teacher education) is rooted in meaningful engagement with research from the first phase of teacher education. Still, there are small direct effects of research and practice orientation on teaching quality, indicating that academic knowledge requires theory and meaning to make it work in practice. The indirect paths of theory application have a larger effect size—meaningfulness and theories are needed to elaborate teaching with research, or what we call research-based evidence. This is partly in line with theoretical assumptions about the need for theories to transfer evidence into practice [40,82,83]. However, our results also show that what Hargreaves [32] called ‘tinkering with solutions’ also contributes to teaching quality. To put it bluntly, ‘chats’ with colleagues about pedagogy alone are not useless, but they are not as effective as using scientific knowledge when it is available. Still, tinkering may be important when no theories are at hand, when teachers feel helpless, or when situations are new.

In summary, meaningful research orientation, combined with a specific meaningful practice orientation, is a lever for applying theory as a resource for improving teaching quality. In fact, the main link between university and school practice may be right in front of our eyes: Meaningful engagement with research establishes a foundation for putting theory into practice. Perhaps, then, the insignificant paths show that there is a lack of understanding of meaningful practice orientation in teacher education and less regard for preparation for meaningful tinkering at university.

Generally, our results are in line with those of numerous previous studies. It is already known that the use of pedagogical knowledge makes a positive contribution to the quality of teaching [7,68,84,85,86]. Zeichner [37,38,39] also supported the notion that research knowledge must be connected to practice in order to be effective. Therefore, the gap between theory and practice is a central challenge of teacher education [87], which can be reduced by reflection [88,89]. Zeichner and Liston [90] emphasised that there are different kinds of reflection, which is consistent with the results of our study. Theory application and tinkering can be seen as two types of pedagogical reflection. One is close to the university (theory application), while the other is more rooted in practice experience (tinkering). Our findings and the literature show that both directions are fruitful and necessary. However, one strength of our study is that we look at these constructs—although from a different theoretical perspective—with a large and representative sample in a structural equation model.

Our findings are limited in their scope and generalisability. Teacher education varies between different countries, so the extent to which our findings apply in other countries is unclear. The directions of our findings can be theoretically rationalised, but causal effects cannot be postulated strongly due to the absence of a (quasi-) experimental design (e.g., [91]). Teacher education extends over a period of several years, and it is difficult or even impossible to control for possible third variables and interactions (e.g., [92]). Field experiments or the retrospective construction of groups via contrafactual causality in propensity score matching [93] may be worth trying in future studies, although doing so would require setting high demands for research designs.

Another shortcoming of our study is the often discussed but still uncertain validity of self-assessment, on which our data were based. For example, research orientation could be assessed differently by university lecturers, which might provide a more accurate picture in some ways. The same is true for teaching quality. However, Clausen [94] and Gruehn [95] showed that learners’ own assessments of learning opportunities explain academic performance better than assessments by others. This underscores the importance and validity of learners’ (self-) assessment. We also ignored competence. Theory application might be a competence, but it is unclear how skilled prospective teachers are in such applications. While Klein et al. [60,61] argued that pre-service teachers have low competence in terms of applying theories, the fact that we found positive effects for theory application is positive. Even theory application may require some tinkering, as theories are rarely an exact fit in classroom practice. In solving problems in practice, it might be hard to know where theory application ends and tinkering begins. Based on interview data, Hinzke et al. [31] showed that tinkering is rooted in practice itself, meaning that teachers develop solutions themselves. This can be distinguished from theory application, which is based on academic knowledge. Another limitation of this study is that the data are based on self-assessments. However, it should be noted that the self-assessment of pre-service and student teachers is certainly relevant to how they experience their living environment (e.g., [96]) and also provides clues about their competencies [97]. Self-assessment thus provides valid insights into how the respondents experience learning opportunities in both phases of teacher education. Together with construct validity, this results in a certain robustness of the data. However, some punctuations in the confirmatory factor analysis show low factor loadings. In particular, the dimensionality of teaching quality is contested (e.g., [78]).

In addition, we did not check for differences between the federal states of Germany and school tracks, and there may have been differences in both phases of teacher training, which might be blurred in the target model. The analysis assumes the stability of the constructs, but that assumption is not sacrosanct [98]. Pre-service teachers assessed the research and practice orientation of their academic learning opportunities only once. Their understanding of what research could—or even should— accomplish changed during the course of their studies. More measurement points and analysis of alpha, beta, and gamma changes could be one way to address this issue (e.g., [99]). However, having more measurement points would not have addressed the panel attrition in our data, which reduced the validity of our results, as the missing values were not random. We decided to fill the missing values with the most similar actual measure available from the first phase of teacher education. Still, this was not as good as the full data. It could be that students who were dissatisfied with their studies increasingly dropped out of the panel. This would mean that the assessment of learning opportunities in our data is positively biased in terms of intensity and effect size. Accordingly, our analysis would only apply to pre-service teachers and student teachers who were reasonably satisfied with teacher education.

6. Conclusions

Our study contributes to the discussion on the professional development of teachers in five key ways. (a) Practical orientation at university is rarely experienced as meaningful. The demand for more practice in the university elements of teacher education should, therefore, be reconsidered, as well as the concept of practice orientation itself. (b) Research orientation is experienced as being more meaningful. Accordingly, research orientation is a resource for gaining insight into the meaning of university knowledge and not an emphasis on practice per se. (c) Meaning orientation is important for theory application, which in turn contributes to the development of teaching quality, and it has a greater impact than tinkered solutions. (d) The path to good teaching seems to lead from meaningful research orientation at universities to the use of theory in in-service training programmes. (e) Tinkering is a constitutive part of teaching practice, but it is not fostered by teacher education.

In summary, our study indicates that teacher education should prepare students for learning in guided practice in in-service training programmes, but ultimately it is not preparation for practice that ‘on-the-job’ training is for. Our findings underline that solid preparation of future teachers for practice in the second phase—as well as later on, when on the job—is likely to require an elaborate understanding of research and the meanings associated with it. We also interpret the findings as a hint that practice orientation must be viewed as a very specific functionality that is currently largely missing and, therefore, has little influence, although it is still necessary for teaching quality.

Author Contributions

The three authors contributed equally. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data are available at the NEPS.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Items related to learning opportunities at university (t1).

Table A1.

Items related to learning opportunities at university (t1).

| Item | Research Orientation α = 0.64 | M (SD) |

|---|---|---|

| t246401 | How strongly is your university degree programme characterised by a research focus in teaching? | 3.02 (0.92) |

| t246402 | How often do lecturers deal with questions of ongoing research in your courses? | 2.84 (0.95) |

| t246403 | Lecturers introduce the application of research methods. | 2.49 (0.91) |

| t246404 | Teachers promote the ability to conduct research independently. | 2.96 (1.01) |

| Practice orientation α = 0.84 | ||

| t246411 | How strongly is your university degree programme characterised by its close practical relevance? | 2.98 (1.16) |

| t246412 | How strongly is your university degree programme characterised by the promotion of practical professional skills? | 2.98 (1.05) |

| t246413 | How strong is your university course characterised by a close connection between theory and practice? | 3.18 (1.09) |

| Meaning orientation α = 0.68 | ||

| t245411 | In my course of study, emphasis is placed on understanding fundamental relationships. | 4.13 (0.79) |

| t245412 | In my course of study, emphasis is placed on encouraging a critical examination of the course content. | 3.08 (0.87) |

| t245413 | In my course of study, emphasis is placed on being able to critically compare and evaluate different theories and concepts. | 3.72 (0.98) |

| t245414 | In my course of study, it is important to think and work independently. | 4.05 (0.84) |

Note. Items are translated from German.

Appendix B

Table A2.

Items related to in-service training programmes (t2).

Table A2.

Items related to in-service training programmes (t2).

| Item | Theory Application α = 0.73 | M (SD) |

|---|---|---|

| tg64231 | How to apply theoretical concepts in the school context is made clear in the seminar. | 3.10 (0.74) |

| tg64232 | The relevance of more theoretical models is clarified in the seminar using examples from school practice. | 2.97 (0.77) |

| tg64233 | Real situations from the classroom are taken up in the seminar and analysed from a theoretical perspective. | 3.02 (0.80) |

| tg64234 | Theories are used in the seminar to explain unforeseen events in the classroom. | 2.67 (0.79) |

| Tinkering α = 0.64 | ||

| tg64221 | We discuss our different views on teaching in the seminar. | 3.26 (0.80) |

| tg64222 | Various participants in the seminar often present their different approaches, which we then discuss. | 2.94 (0.89) |

| tg64223 | We are encouraged in the seminar to discuss opposing views among ourselves. | 3.05 (0.81) |

| Teaching quality α = 0.71 | ||

| tg65121 | Teach in such a way that students have to transfer. | 3.72 (0.76) |

| tg65122 | Design learning environments in such a way that problem-based learning is possible. | 3.66 (0.84) |

| tg65123 | Consider findings on the acquisition of knowledge and skills for my lesson design. | 3.82 (0.73) |

| tg65124 | Use students’ mistakes to initiate new learning processes or to continue them. | 3.82 (0.81) |

| tg65125 | Maintain students’ concentration through the use of multiple methods. | 3.97 (0.72) |

| tg65126 | Student-centred and student-oriented teaching. | 4.24 (0.68) |

| tg65127 | I motivate students by relating the material to their world. | 4.12 (0.74) |

| tg65128 | Allow the student sufficient time to practise. | 3.90 (0.72) |

Note. Items are translated from German.

Appendix C

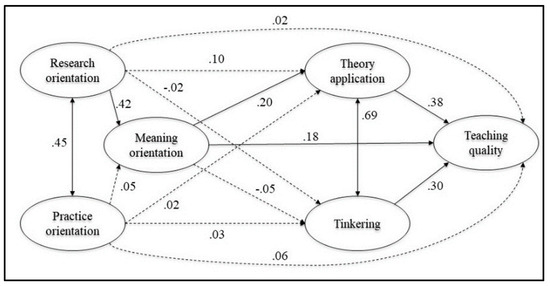

The effects of learning opportunities at university in the first semester and the in-service training programme on teaching quality.

Figure A1.

N = 1417, RMSEA = 0.05, CFI = 0.90, TLI = 0.89, all effect sizes are significant (p < 0.01), dashed paths are not significant.

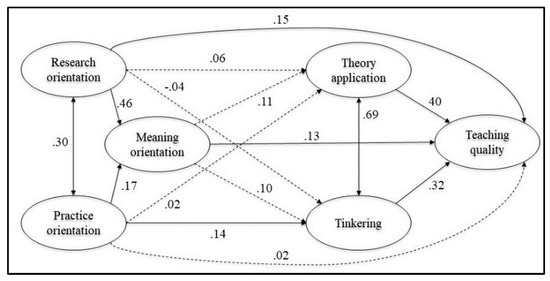

The effects of learning opportunities at university in the fifth semester and the in-service training programme on teaching quality.

Figure A2.

N = 1085, RMSEA = 0.05, CFI = 0.91, TLI = 0.90, all effect sizes are significant (p < 0.05), dashed paths are not significant.

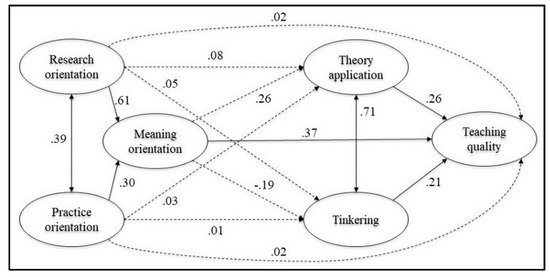

The effects of learning opportunities at university in the seventh semester and the in-service training programme on teaching quality.

Figure A3.

N = 301, RMSEA = 0.05, CFI = 0.91, TLI = 0.89, all effect sizes are significant (p < 0.05), dashed paths are not significant.

References

- Renkl, A. Meta-analyses as a privileged information source for informing teachers’ practice? Z. Für Pädagogische Psychol. 2022, 36, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stark, R. Probleme evidenzbasierter bzw.-orientierter pädagogischer Praxis. Z. Für Pädagogische Psychol. 2017, 31, 99–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortina, K.S.; Thames, M.H. Teacher education in Germany. In Cognitive Activation in the Mathematics Classroom and Professional Competence of Teachers; Kunter, M., Baumert, J., Blum, W., Klusmann, U., Krauss, S., Neubrand, M., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013; pp. 49–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shulman, L.S. Knowledge and teaching: Foundations of the new reform. Harv. Educ. Rev. 1987, 57, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumert, J.; Kunter, M. Stichwort: Professionelle Kompetenz von Lehrkräften. Z. Für Erzieh. 2006, 9, 469–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Förtsch, C.; Sommerhoff, D.; Fischer, F.; Fischer, M.R.; Girwidz, R.; Obersteiner, A.; Reiss, K.; Stürmer, K.; Siebeck, M.; Schmidmaier, R.; et al. Systematizing professional knowledge of medical doctors and teachers: Development of an interdisciplinary framework in the context of diagnostic competences. Educ. Sci. 2018, 8, 207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voss, T.; Kunina-Habenicht, O.; Hoehne, V.; Kunter, M. Stichwort Pädagogisches Wissen von Lehrkräften: Empirische Zugänge und Befunde. Z. Für Erzieh. 2015, 18, 187–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Depping, D.; Ehmke, T.; Besser, M. Aus “Erfahrung” wird man selbstwirksam, motiviert und klug: Wie hängen unterschiedliche Komponenten professioneller Kompetenz von Lehramtsstudierenden mit der Nutzung von Lerngelegenheiten zusammen? Z. Für Erzieh. 2021, 24, 185–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gogolin, I.; Hannover, B.; Scheunpflug, A. Evidenzbasierung als leitendes Prinzip in der Ausbildung von Lehrerinnen und Lehrern–Editorial. In Evidenzbasierung in der Lehrkräftebildung; Gogolin, I., Hannover, B., Scheunpflug, A., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020; Edition ZfE; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teichler, U. Hochschulbildung. In Handbuch Bildungsforschung; Tippelt, R., Schmidt-Hertha, B., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2018; pp. 505–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolter, A.; Banscherus, U. Praxisbezug und Beschäftigungsfähigkeit im Bologna-Prozess—“A never ending story“. In Studium nach Bologna: Praxisbezüge stärken? Schubarth, W., Speck, K., Seidel, A., Gottmann, C., Kamm, C., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2012; pp. 21–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferguson, L.E. Evidence-informed teaching and practice-informed research. Z. Für Pädagogische Psychol. 2021, 35, 199–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aschinger, F.; Epstein, H.; Müller, S.; Schaeper, H.; Vöttiner, A.; Weiß, T. Higher education and the transition to work. Z. Für Erzieh. 2011, 14, 267–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klieme, E.; Lipowsky, F.; Rakoczy, K.; Ratzka, N. Qualitätsdimensionen und Wirksamkeit von Mathematikunterricht. Theoretische Grundlagen und ausgewählte Ergebnisse des Projekts “Pythagoras”. In Untersuchungen zur Bildungsqualität von Schule; Prenzel, M., Alliolio-Näcke, L., Eds.; Waxmann: Münster, Germany, 2006; pp. 127–146. [Google Scholar]

- Radisch, F.; Stecher, L.; Klieme, E.; Kühnbach, O. Unterrichts- und Angebotsqualität aus Schülersicht. In Ganztagsschule in Deutschland. Ergebnisse der Ausgangserhebung der “Studie zur Entwicklung von Ganztagsschulen” (StEG); Holtappels, H., Klieme, E., Rauschenbach, T., Stecher, L., Eds.; Juventa: Münster, Germany, 2007; pp. 227–260. [Google Scholar]

- Shavelson, R.J. Research on teaching and the education of teachers: Brokering the gap. Beiträge Zur Lehr. Und Lehr. 2020, 38, 37–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dekker, I.; Meeter, M. Evidence-based education: Objections and future directions. Front. Educ. 2022, 7, 941410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newton, P.M.; Da Silva, A.; Berry, S. The Case for Pragmatic Evidence-Based Higher Education: A Useful Way Forward? Front. Educ. 2020, 5, 583157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slavin, R.E. How evidence-based reform will transform research and practice in education. Educ. Psychol. 2020, 55, 21–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferguson, L.E.; Bråten, I.; Skibsted Jensen, M.; Andreassen, U.R. A Longitudinal Mixed Methods Study of Norwegian Preservice Teachers’ Beliefs About Sources of Teaching Knowledge and Motivation to Learn from Theory and Practice. J. Teach. Educ. 2023, 74, 55–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groß-Ophoff, J.; Brown, C.; Helm, C. Do pupils at research-informed school actually perform better? Findings from a study at English schools. Front. Educ. 2023, 7, 935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Healey, M. Linking research and teaching: Exploring disciplinary spaces and the role of inquiry-based learning. In Reshaping the University: New Relationships between Research, Scholarship and Teaching; Barnett, R., Ed.; Open University Press: Maidenhead, UK, 2005; pp. 67–78. [Google Scholar]

- Bäumer, T.; Preis, N.; Roßbach, H.-G.; Stecher, L.; Klieme, E. Education processes in life-course-specific learning environments. Z. Für Erzieh. 2011, 14, 67–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaeper, H.; Weiß, T. The conceptualization, development, and validation of an instrument for measuring the formal learning environment in higher education. In Methodological Issues of Longitudinal Studies; Blossfeld, H.-P., von Maurice, J., Bayer, M., Skopek, J., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany; Waxmann: Münster, Germany, 2016; pp. 267–290. [Google Scholar]

- Rochnia, M.; Trempler, K.; Schellenbach-Zell, J. Vergleich der Forschungs- sowie Praxisorientierung zwischen Lehramts- und Medizinstudium. Z. Für Empir. Hochschulforschung 2019, 3, 123–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, L.; Krathwohl, D.R. A Taxonomy for Learning, Teaching and Assessing: A Revision of Bloom’s Taxonomy of Educational Objectives; Longman: Harlow, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Kunz, H.; Uhl, S. Allgemeine Ziele, Aufbau und Struktur des Vorbereitungsdienstes in den Bundesländern. In Das Referendariat; Peitz, J., Harring, M., Eds.; Waxmann: Münster, Germany, 2021; pp. 15–27. [Google Scholar]

- Weber, K.E.; Czerwenka, K. Anschlussfähigkeit und Kooperation der ersten und zweiten Phase der Lehrkräftebildung. In Das Referendariat; Peitz, J., Harring, M., Eds.; Waxmann: Münster, Germany, 2021; pp. 255–264. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson-Park, E.; Abs, H.J. Lehrerinnen- und Lehrerbildung im Vorbereitungsdienst. In Handbuch Lehrerinnen- und Lehrerbildung; Cramer, C., König, J., Rothland, M., Blömeke, S., Eds.; Julius Klinkhardt: Bad Heilbrunn, Germany, 2020; pp. 332–337. [Google Scholar]

- Artmann, M.; Herzmann, P.; Hoffmann, M.; Proske, M. Wissen über Unterricht—Zur Reflexionskompetenz von Studierenden in der ersten Phase der Lehrerbildung. In Formation und Transformation in der Lehrerbildung; Gehrmann, A., Kranz, B., Pelzmann, S., Reinartz, A., Eds.; Julius Klinkhardt: Bad Heilbrunn, Germany, 2013; pp. 134–150. [Google Scholar]

- Hinzke, J.-H.; Gesang, J.; Besa, K.-S. Zur Erschließung der Nutzung von Forschungsergebnissen durch Lehrpersonen. Forschungsrelevanz zwischen Theorie und Praxis. Z. Erzieh. 2020, 23, 1303–1323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hargreaves, D.H. The production, mediation and use of professional knowledge among teachers and doctors: A comparative analysis. In Knowledge Management in the Learning Society; OECD Publishing: Berlin, Germany, 2000; pp. 219–238. [Google Scholar]

- Gruber, H.; Harteis, C.; Rehrl, M. Professional learning: Erfahrung als Grundlage von Handlungskompetenz. Bild. Und Erzieh. 2006, 59, 193–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kounin, J.S. Techniken der Klassenführung; Waxmann: Münster, Germany, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Bromme, B.; Tillema, H. Fusing experience and theory: The structure of professional knowledge. Learn. Instr. 1995, 5, 261–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogt, M.; Scholz, J. Entwicklung und Struktur der Lehrerinnen- und Lehrerbildung in Deutschland. In Handbuch Lehrerinnen- und Lehrerbildung; Cramer, C., König, J., Rothland, M., Blömeke, S., Eds.; Julius Klinkhardt: Bad Heilbrunn, Germany, 2020; pp. 217–226. [Google Scholar]

- Zeichner, K. Rethinking the Connections Between Campus Courses and Field Experiences in College- and University-Based Teacher Education. J. Teach. Educ. 2010, 61, 89–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeichner, K. Becoming a teacher educator: A personal perspective. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2005, 21, 117–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeichner, K. Two Visions of Teaching and Teacher Education for the Twenty-First Century. In Preparing Teachers for the 21st Century; Zhu, X., Zeichner, K., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013; pp. 3–19. [Google Scholar]

- Bleck, V.; Lipowsky, F. Dröge, nutzlos, praxisfern? Wie verändert sich die Bewertung wissenschaftlicher Studieninhalte in Schulpraktika? In Praxissemester im Lehramtsstudium in Deutschland: Wirkungen auf Studierende; Ulrich, I., Gröschner, A., Eds.; Edition Zeitschrift für Erziehungswissenschaft, Bd.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020; Volume 9, pp. 97–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otto, S. Die Initiation in die schulische Praxis. Das Erstgespräch zwischen Studierenden und ihren Mentorinnen und Mentoren an Schulen. In Professionalisierungsprozesse Angehender Lehrpersonen in den Berufspraktischen Studien; Košinár, J., Leineweber, S., Schmid, E., Eds.; Waxmann: Münster, Germany, 2016; pp. 173–186. [Google Scholar]

- Merk, S.; Rosman, T.; Rueß, J.; Syring, M.; Schneider, J. Pre-service teachers‘ perceived value of general pedagogical knowledge for practice: Relations with epistemic beliefs and source beliefs. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0184971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeuch, N.; Souvignier, E. Zentrale Facetten wissenschaftlichen Denkens bei Lehramtsstudierenden. Unterrichtswissenschaft 2015, 43, 245–262. [Google Scholar]

- Hendriks, F.; Seifried, E.; Menz, C. Unraveling the “smart but evil” stereotype: Pre-service teachers’ evaluation of educational psychology researchers versus teachers as sources of information. Z. Für Pädagogische Psychol. 2021, 35, 157–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bråten, I.; Ferguson, L.E. Beliefs about sources of knowledge predict motivation for learning in teacher education. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2015, 50, 13–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joram, E.; Gabriele, A.J.; Walton, K. What influences teachers’ “buy-in” of research? Teachers’ beliefs about the applicability of educational research to their practice. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2020, 88, 102980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lysenko, L.V.; Abrami, P.C.; Bernard, R.M.; Dagenais, C.; Janosz, M. Educational research in educational practice: Predictors of use. Can. J. Educ. 2014, 37, 1–26. [Google Scholar]

- Martinovic, D.; Wiebe, N.; Ratkovic, S.; Willard-Holt, C.; Spencer, T.; Cantalini-Williams, M. “Doing research was inspiring”: Building a research community with teachers. Educ. Action Res. 2012, 20, 385–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farley-Ripple, E.; May, H.; Karpyn, A.; Tilley, K.; McDonough, K. Rethinking connections between research and practice in education: A conceptual framework. Educ. Res. 2018, 47, 235–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, D.; Coles, L. Teachers’ approaches to finding and using research evidence: An information literacy perspective. Educ. Res. 2007, 49, 185–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartung-Beck, V.; Schlag, S. Lerntagebücher als Reflexionsinstrument im Praxissemester. HLZ 2020, 3, 75–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartmann, U.; Kindlinger, M.; Trempler, K. Integrating information from multiple texts relates to pre-service teachers’ epistemic products for reflective teaching practice. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2021, 97, 103205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trempler, K.; Hartmann, U. Wie setzen sich angehende Lehrkräfte mit pädagogischen Situationen auseinander? Z. Für Erzieh. 2020, 23, 1053–1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, L.E.; Klassen, R.M. Teachers’ cognitive processing of complex school-based scenarios: Differences across experience levels. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2018, 73, 215–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hennissen, P.; Beckers, H.; Moerkerke, G. Linking practice to theory in teacher education: A growth in cognitive structures. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2017, 63, 314–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van den Bogert, N.; Van Bruggen, J.; Kostons, D.; Jochems, W. First steps into understanding teachers’ visual perception of classroom events. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2014, 37, 208–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohlsson, S. The cognitive skill of theory articulation: A neglected aspect of science education. Sci. Educ. 1992, 1, 181–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, K.; Krapp, A. Wissenschaftstheoretische Grundfragen der Pädagogischen Psychologie. In Pädagogische Psychologie; Krapp, A., Weidenmann, B., Eds.; Beltz: Findlay, OH, USA, 2006; pp. 31–71. [Google Scholar]

- Dollard, J.; Doob, L.W.; Miller, N.; Mowrer, O.H.; Sears, R.R. Frustration and Aggression; Yale University Press: New Haven, CT, USA, 1939. [Google Scholar]

- Klein, M.; Wagner, K.; Klopp, E.; Stark, R. Förderung anwendbaren bildungswissenschaftlichen Wissens bei Lehramtsstudierenden anhand fehlerbasierten kollaborativen Lernens. Unterrichtswissenschaft 2015, 43, 225–244. [Google Scholar]

- Klein, M.; Wagner, K.; Klopp, E.; Stark, R. Fostering of applicable educational knowledge in pre-service teachers: Effects of an error-based seminar concept and instructional support during testing on qualities of applicable knowledge. J. Educ. Res. Online 2017, 9, 88–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durkin, K.; Rittle-Johnson, B. The effectiveness of using incorrect examples to support learning about decimal magnitude. Learn. Instr. 2012, 22, 206–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oser, F.; Spychiger, M. Lernen ist schmerzhaft. Zur Theorie des Negativen Wissens und zur Praxis der Fehlerkultur; Beltz: Findlay, OH, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Praetorius, A.-K.; Klieme, E.; Herbert, B.; Pinger, P. Generic dimensions of teaching quality: The German framework of three basic dimensions. ZDM Math. Educ. 2018, 50, 407–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dicke, T.; Parker, P.D.; Holzberger, D.; Kunina-Habenicht, O.; Kunter, M.; Leutner, D. Beginning teachers’ efficacy and emotional exhaustion: Latent changes, reciprocity, and the influence of professional knowledge. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 2015, 41, 62–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gindele, V.; Voss, T. Pädagogisch-psychologisches Wissen: Zusammenhänge mit Indikatoren des beruflichen Erfolgs angehender Lehrkräfte. Z. Für Bild. 2017, 7, 255–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lohse-Bossenz, H.; Kunina-Habenicht, O.; Dicke, T.; Leutner, D.; Kunter, M. Teachers’ knowledge about psychology: Development and validation of a test measuring theoretical foundations for teaching and its relation to instructional behavior. Stud. Educ. Eval. 2014, 44, 36–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfanzl, B.; Thomas, A.; Matischek-Jauk, M. Pädagogisches Wissen und pädagogische Handlungskompetenz. Erzieh. Und Unterr. 2013, 1, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Voss, T.; Kunter, M.; Seiz, J.; Hoehne, V.; Baumert, J. Die Bedeutung des pädagogisch-psychologischen Wissens von angehenden Lehrkräften für die Unterrichtsqualität. Z. Für Pädagogik 2014, 60, 184–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blossfeld, H.-P.; Rossbach, H.-G.; Von Maurice, J. (Eds.) Education as a Lifelong Process—The German National Educational Panel Study (NEPS); Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FDZ-LIfBi. Data Manual NEPS Starting Cohort 5—First-Year Students: From Higher Education to the Labor Market. Leibniz Institute for Educational Trajectories. 2021. Available online: https://www.neps-data.de/Portals/0/NEPS/Datenzentrum/Forschungsdaten/SC5/15-0-0/SC5_15-0-0_Datamanual.pdf (accessed on 1 April 2023).

- Kunter, M.; Baumert, J.; Blum, W.; Klusmann, U.; Krauss, S.; Neubrand, M. (Eds.) Professionelle Kompetenz von Lehrkräften. Ergebnisse des Forschungsprogramms COACTIV; Waxmann: Münster, Germany, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Kunina-Habenicht, O.; Schulze-Stocker, F.; Kunter, M.; Baumert, J.; Leutner, D.; Förster, D.; Lohse-Bossenz, H.; Terhart, E. Die Bedeutung der Lerngelegenheiten im Lehramtsstudium und deren individuelle Nutzung für den Aufbau des bildungswissenschaftlichen Wissens. Z. Für Pädagogik 2013, 59, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weresch-Deperrois, I.; Bodensohn, R.; Jäger, R.S. KOSTA—Ein Instrument zur Kompetenz- und Standardorientierung in der Lehrerbildung: Skalenhandbuch; Universität Koblenz Landau-Präsidialamt Mainz: Mainz, Germany, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Schnell, R.; Hill, P.B.; Esser, E. Methoden der Empirischen Sozialforschung; Oldenburg: Oldenburg, Germany, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Arbuckle, J.; Wothke, W. AMOS 4 user’s Reference Guide; Smallwaters Corporation: Chicago, IL, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Stahns, R.; Rieser, S.; Hußmann, A. Können Viertklässlerinnen und Viertklässer Unterrichtsqualität valide einschätzen? Ergebnisse zum Fach Deutsch. Unterrichtswissenschaft 2020, 48, 663–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Praetorius, A.-K.; Gräsel, C. Noch immer auf der Suche nach dem heiligen Gral: Wie generisch oder fachspezifisch sind Dimensionen der Unterrichtsqualität? Unterrichtswissenschaft 2021, 49, 167–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- KMK. Standards für die Lehrerbildung: Bildungswissenschaften; Sekretariat der Kultusministerkonferenz: Bonn, Germany, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, J. A power primer. Psychol. Bull. 1992, 112, 155–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neuweg, G.H. Reflexivität. Über Wesen, Sinn und Grenzen eines lehrerbildungsdidaktischen Leitbildes. Z. Für Bild. 2021, 11, 459–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bromme, R.; Prenzel, M.; Jäger, M. Empirische Bildungsforschung und evidenzbasierte Bildungspolitik. Z. Für Erzieh. 2014, 17, 3–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patry, J.-L. Theoretische Grundlagen des Theorie-Praxis-Problems in der Lehrer/innenbildung. In Schulpraktika in der Lehrerausbildung. Theoretische Grundlagen, Konzeptionen, Prozesse und Effekte; Arnold, K.-H., Gröschner, A., Hascher, T., Eds.; Waxmann: Münster, Germany, 2014; pp. 29–44. [Google Scholar]

- Beck, E.; Baer, M.; Guldimann, T.; Bischoff, S.; Brühwiler, C.; Müller, P.; Niedermann, R.; Rogalla, M.; Vogt, F. (Eds.) Adaptive Lehrkompetenz. Analyse und Struktur, Veränderung und Wirkung handlungssteuernden Lehrerwissens; Waxmann: Münster, Germany, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- König, J.; Kaiser, G.; Felbrich, A. Spiegelt sich pädagogisches Wissen in den Kompetenzselbsteinschätzungen angehender Lehrkräfte? Zum Zusammenhang von Wissen und Überzeugungen am Ende der Lehrerausbildung. Z. Für Pädagogik 2012, 58, 476–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- König, J.; Blömeke, S.; Klein, P.; Suhl, U.; Busse, A. Is teachers’ general pedagogical knowledge a premise for noticing and interpreting classroom situations? A video-based assessment approach. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2014, 38, 76–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korthagen, F.A.J. How teacher education can make a difference. J. Educ. Teach. 2010, 36, 407–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jay, K.J.; Johnson, K.L. Capturing complexity: A typology of reflective practice for teacher education. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2002, 18, 73–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schön, D.A. The Reflective Practitioner. How Professionals Think in Action; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Zeichner, K.M.; Liston, D.P. Reflective Teaching: An Introduction; Erlbaum: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Gustafsson, J.-E. Longitudinal design. In Methodological Advances in Educational Effectiveness Research; Creemers, B., Kyriakides, L., Sammons, P., Eds.; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2010; pp. 77–101. [Google Scholar]

- Berliner, D.C. Educational research: The hardest science of all. Educ. Res. 2002, 31, 18–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubin, D.B. Estimating causal effects of treatment in randomized and non-randomized studies. J. Educ. Psychol. 1974, 66, 688–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clausen, M. Unterrichtsqualität: Eine Frage der Perspektive? Empirische Analysen zur Übereinstimmung, Konstrukt-und Kriteriumsvalidität; Waxmann: Münster, Germany, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Gruehn, S. Unterricht und Schulisches Lernen. Schüler als Quellen der Unterrichtsbeschreibung; Waxmann: Münster, Germany, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner, U. Recent advances in research on the ecology of human development. In Development as Action in Context. Problem Behavior and Normal Youth Development; Silbereisen, R.K., Eyferth, K., Rudinger, G., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1986; pp. 287–309. [Google Scholar]

- Klieme, E.; Rakoczy, K. Unterrichtsqualität aus Schülerperspektive: Kulturspezifische Profile, regionale Unterschiede und Zusammenhänge mit Effekten von Unterricht. In PISA 2000—Ein differenzierter Blick auf die Länder der Bundesrepublik Deutschland; Baumert, J., Artelt, C., Klieme, E., Neubrand, M., Prenzel, M., Schiefele, U., Schneider, W., Tillman, K.-J., Weiß, M., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2003; pp. 333–360. [Google Scholar]

- Bedeian, A.G.; Armenakis, A.A.; Gibson, R.W. The measurement and control of beta change. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1980, 5, 561–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riordan, C.; Richardson, H.A.; Schaffer, B.S.; Vandenberg, R.J. Alpha, beta, and gamma change: A review of past research with recommendations for new directions. In Equivalence in Measurement; Schriesheim, C.A., Neider, L.L., Eds.; Information Age Publishing: Charlotte, NC, USA, 2001; pp. 51–97. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).