Abstract

The European Higher Education Area encourages a substantial change in the roles that students and teachers play at university. Student participation in the learning process should be primarily active, while teachers should adopt a guiding and mediating position. This paper describes a learning experience where an evolution of the roles of the trainers and learners is proposed. This methodology was implemented in the 2021/2022 and 2022/2023 university courses on the Bachelor in Naval Engineering. Students taking these courses are enrolled in the last year out of four of their Bachelor’s and are given the task of changing their role from students to teachers by teaching a lesson. No previous knowledge about the lesson is required; therefore, this learning activity is a double challenge for the students, as they must, on the one hand, learn a new topic and, on the other hand, be able to explain the topic to their colleagues. Surveys related to the activity and the classmates’ performance were carried out once the activity was completed. The results of the surveys show that students acquire technical knowledge more easily than traditional class and strengthen different skills, such as their self-esteem and communication ability. Additionally, the activity indicates the importance and necessity of boosting their autonomous work capacity, since they will be confronted with similar duties in their professional career. Finally, the proposed activity also reduces students’ boredom in subjects that they are initially uninterested in.

1. Introduction

The implementation of the European Higher Education Area has led to a change in the educative model in European universities [1]. The new teaching–learning paradigm implies a more active participation from the student in the educative process [2], while the teacher becomes an orienting and guiding figure in the academic formation [3]. Recent methodologies, such as flipped classroom [4], project-based learning [5], problem-based learning [6], computer applications [7], or gamification [8], have been applied on numerous occasions with satisfactory results. Furthermore, one of the main topics of interest in the teaching context should focus on the improvement of teaching quality, making the lessons more dynamic and attractive to students [9,10,11,12]. Therefore, the actual inclination to develop research and methodologies that evaluate the negative evolution of scholar failure [13] is showing the constant growth of student’s disenchantment with higher education. Therefore, there is a rise in studies and methodologies that consider this matter due to the negative evolution of scholar failure [13] that shows a constant growth of student disenchantment with higher education. In recent decades, many proposals have been written that are concerned with the quality of teaching in universities, but there are still many situations that should be evaluated; for instance, it would be useful to examine the career perspectives of students who do not see a Bachelor’s as the best option for getting a better job or the need for the previous studies to be updated and their adaptation to university [14,15]. However, in the university context, we are preparing students not only from a theoretical but also a practical perspective. Some students will have to cope in their future professional careers with situations that have a high degree of responsibility, particularly if they are part of engineering works. For this reason, it is important to focus not only on their theoretical background but also on their ability to manage technical skills. To learn these skills, the use of theoretical and practical lessons must be combined and boosted for better quality in higher education. It is essential to promote the students’ participation in the teaching process [1,16]. However, sometimes it is not possible to go to a lab or set up participative activities using audiovisual tools [17] or new social media platforms [18,19,20,21] helpful for a better lesson explanation rather than a traditional class. Although the role of the student in the learning process is increasingly important, the teacher’s behavior is also decisive. Lecturers play an essential role in education, not only teaching the subject syllabus but also encouraging students to learn [22] using self-regulated learning to promote transversal skills and self-responsibility [23]. In this situation, a deeper role of the teacher in the learning process is required.

Engineering studies demand practice and thinking more than just studying [24]. Therefore, it is necessary to focus on technical teaching at university. Most of the engineering problems require comprehension, analysis, reasoning, and considerable practice. Indeed, today’s world of work requires engineers who are able to learn and solve problems for themselves and have a strong technical basis [25]. Within this context, the University of Las Palmas de Gran Canaria (Spain) offers the Bachelor’s in Naval Engineering. This Bachelor’s, which lasts four years, has two different branches: marine structures and propulsion systems. The branches must be chosen in the third year of the Bachelor’s. The last year is divided into two parts; one part consists of developing the final year project and industry practices, and the other part contains some theoretical subjects. During the last year, the theoretical subjects are developed in the evening. This schedule is thus organized since students must develop their practical training in companies during the mornings. All of this implies that the students must be self-sufficient and organized in their last year of their Bachelor’s, which results in extra pressure to pass the remaining subjects, develop and defend their final Bachelor’s project, and successfully finish their training in companies. Therefore, the students must work daily in their final year of their Bachelor’s for more than 8 h a day during some periods.

The situation stated here can cause the students’ interest to decrease in some theoretical subjects that they consider irrelevant, since they prioritize the final project. Students decide ultimately to consider some of the subjects as goals that must be passed more than valuable knowledge that they can acquire [26]. In the case study, one of the subjects students treat this way is Naval Shipbuilding (NS). This subject is placed in the fourth year and in the marine structures branch. The student learns the origin and evolution of ship building and the most remarkable periods and discoveries in shipbuilding history. The process of how a ship is built is also explained in detail. Finally, the operation and maintenance of a ship during its lifecycle is described. As can be appreciated, this subject is fundamentally theoretical. Therefore, the student must memorize the provided theory notes for passing the final exam. In traditional lessons in university, a student’s participation has commonly been reduced to their presence [27], but, as stated previously, recent studies promote the use of active methodologies to improve understanding and information retention [28]. Regarding the NS subject, the lecturer observed that interest in the subject decreased as the subject was developed. The students’ interest and behavior in the subject progresses through the following stages:

- First stage. At the beginning of the course, the students began motivated, asked questions and did not miss many classes (90% average attendance). It should be clarified that attendance is not compulsory but gives an extra point in the final mark. Students are only attending the theoretical class and have not yet started their final Bachelor’s project or their company training. During this period, the lecturer asked students to read different news sources about the subject for the next class discussion. Between 80 and 90% of the students read the articles and participated in the class discussion.

- Second stage. After the first month out of a four-month class period, the students’ attendance decreased by approximately 10–20%. In this stage, only a few questions were asked in class and the students did not seem to be interested in the subject. Homework was only developed by 40–50% of the students. The students have started their final projects, so the pressure has increased and time for the rest of the subjects has decreased.

- Third stage. During the last part of the course, most of the students did company practices in the morning, usually from 8 a.m. until 2 p.m., and they took the university lessons from the afternoon until the evening. The students missed many classes, and their attendance was random but less than 60%. They do not seem to be focused on the class, and most of them admit that they feel tired and stressed because of the “lifestyle” of the last course. They also indicate that the classes are very late (7–9 p.m.), so they cannot focus on the lesson adequately because of the physical and mental fatigue.

- Fourth stage. Approximately two weeks before the course ended, the students were completely disconnected from the subject. The teacher asked questions about the latest class, and less than 40% knew the answer. Indeed, when a non-informed test was carried out including simple questions about previous lessons, 100% of the students failed.

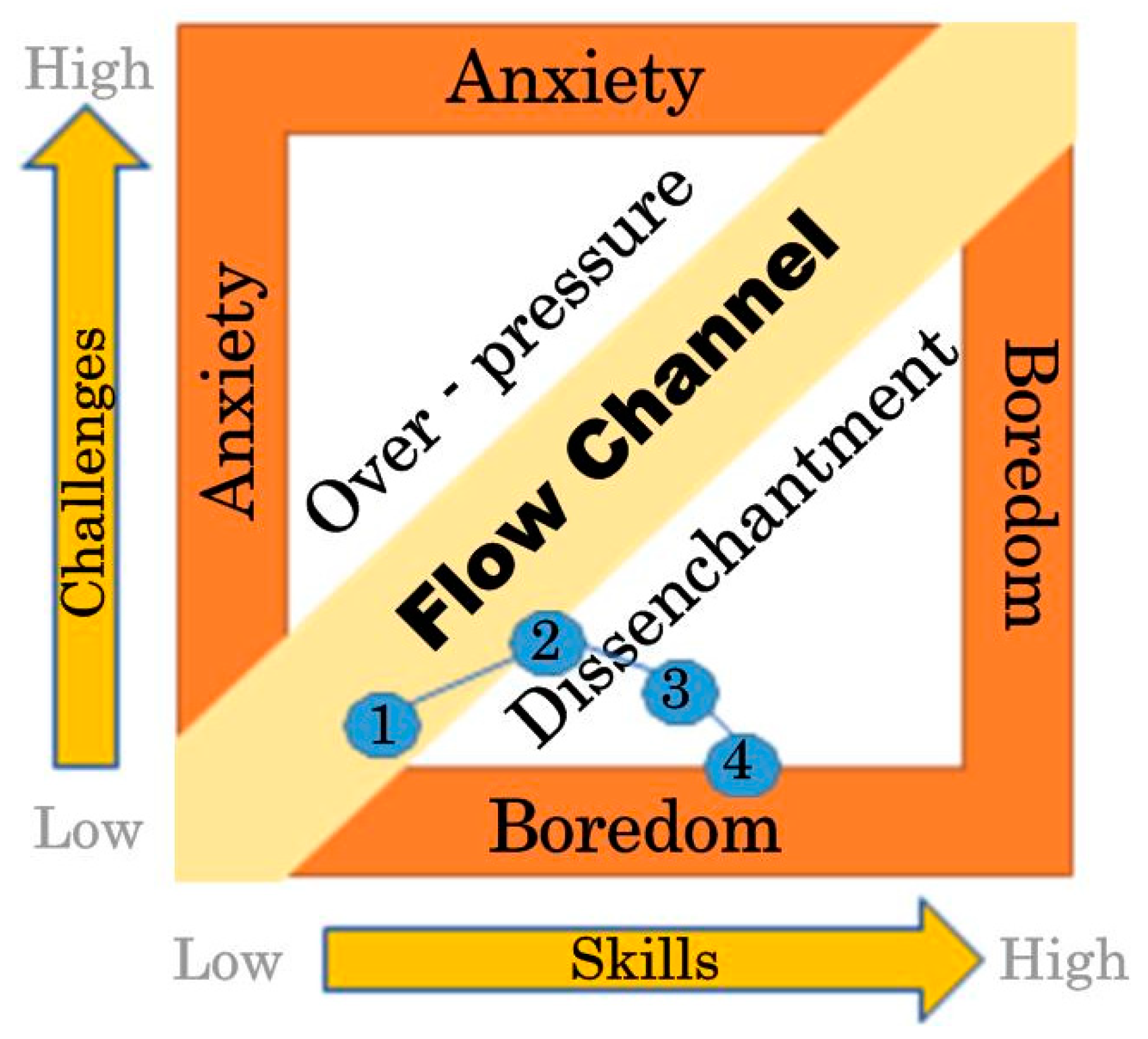

These four stages representing where a student can be during their immersion in the subject are represented using a flow chart, which is defined by [29,30], where the holistic sensation of people is presented (Figure 1). The purpose of the lesson is emphasized, indicating that the student should learn more skills without suffering either anxiety or boredom. Those feelings are the extreme feelings that a student should suffer and they are indicative that something is not working properly. However, this figure represents the sensation that students are “feeling” their way through the subject and plotting their decrement of interest, a lack of pressure, and the minimum required skills.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of traditional class. The number sequence refers to stages undergone.

All this leads the lecturer to reflect on what has produced the change in students’ attitude throughout the course from Stage 1 to Stage 4. Everything suggests that students are overloaded with their final project and the company training, which results in them becoming only interested in passing the subject. To change this situation, all of these negative aspects must be evaluated, and a solution should be provided.

In recent years, interest has increased in the 1980’s concept “To teach is to learn twice” [31], and considerable research has been undertaken on this concept. In the 1970s, Goldschmid et al. [32] described the first experiences of peer teaching in the university environment, where discussion groups led by professor assistant students helped other students debate activities or prepare exams. Having a student prepare a lesson for the rest of the class was first introduced by Jean-Pol Marti in the late 1980s regarding learning French as a foreign language. This activity began to also be widely used in universities at the end of the twentieth century [33]. The student not only learns how to teach but also develops communicative competence and complex thought skills [34]. The use of peer teaching in university is currently associated with different degree programs, such as medicine [35,36,37], environmental sciences [38], geospatial technologies [39], or biology [40]. In the field of engineering, the international literature is replete with examples [41,42,43,44]. To our knowledge, there are no previous experiences in naval engineering and in a predominantly theorical subject. Furthermore, having a student prepare a lesson for the rest of the class might help them overcome the above-described stressful situations that occur in the last months of the last course of their Bachelor’s, and it will motivate them to focus on particular subjects [45].

Based on our previous experience and the results of previous research, in this paper a cooperative learning methodology based on peer learning is introduced and analyzed in the naval engineering context. This methodology was used in the 2021/2022 and 2022/2023 courses of NS. The proposed methodology attempts to strengthen professional development in the class and keep the students interested in the lesson. Furthermore, this methodology will reinforce other transversal competences, such as students’ leadership capacity, autonomous work, and communicational abilities.

2. Methods

2.1. Methodology

2.1.1. Traditional Classes

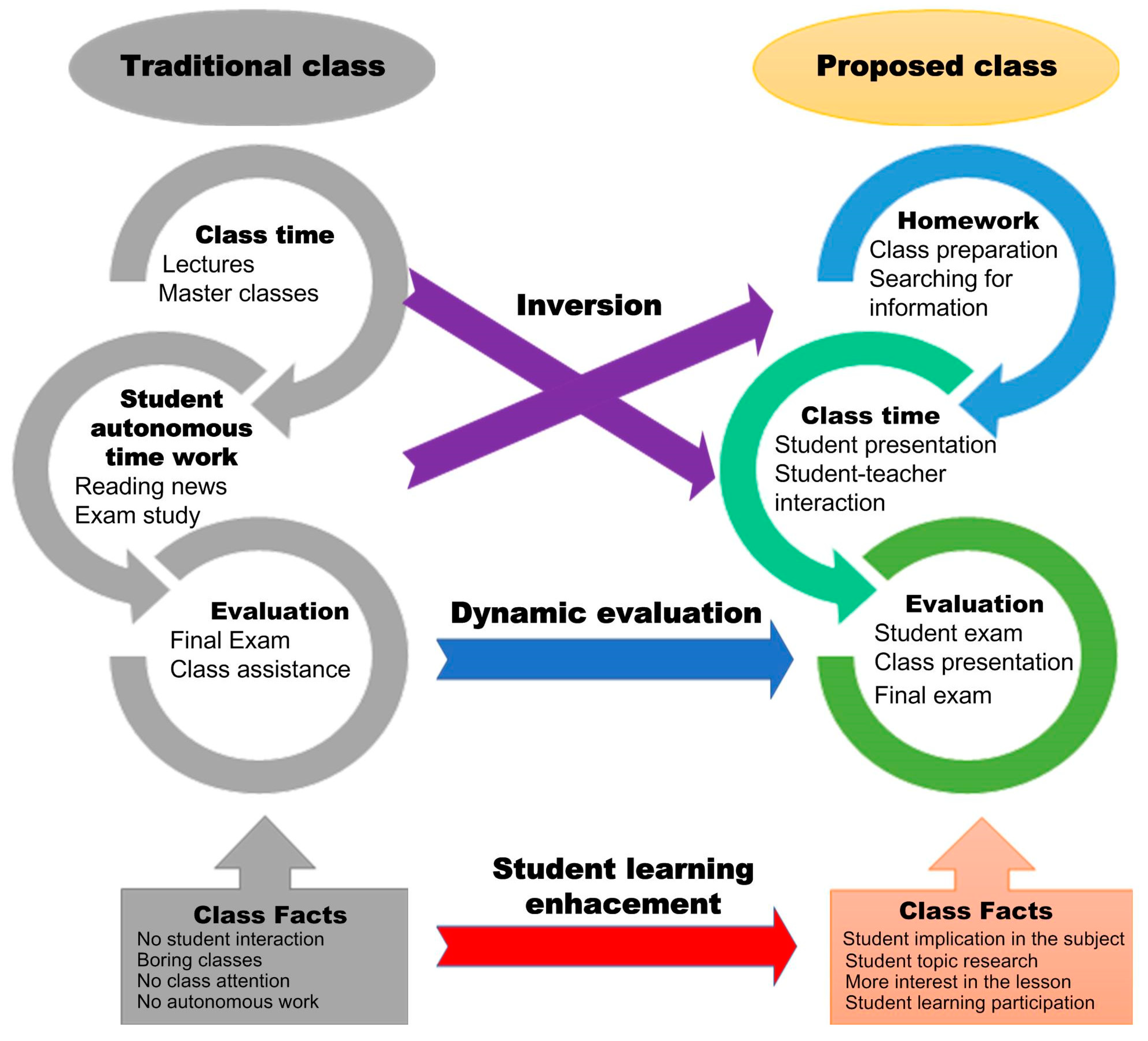

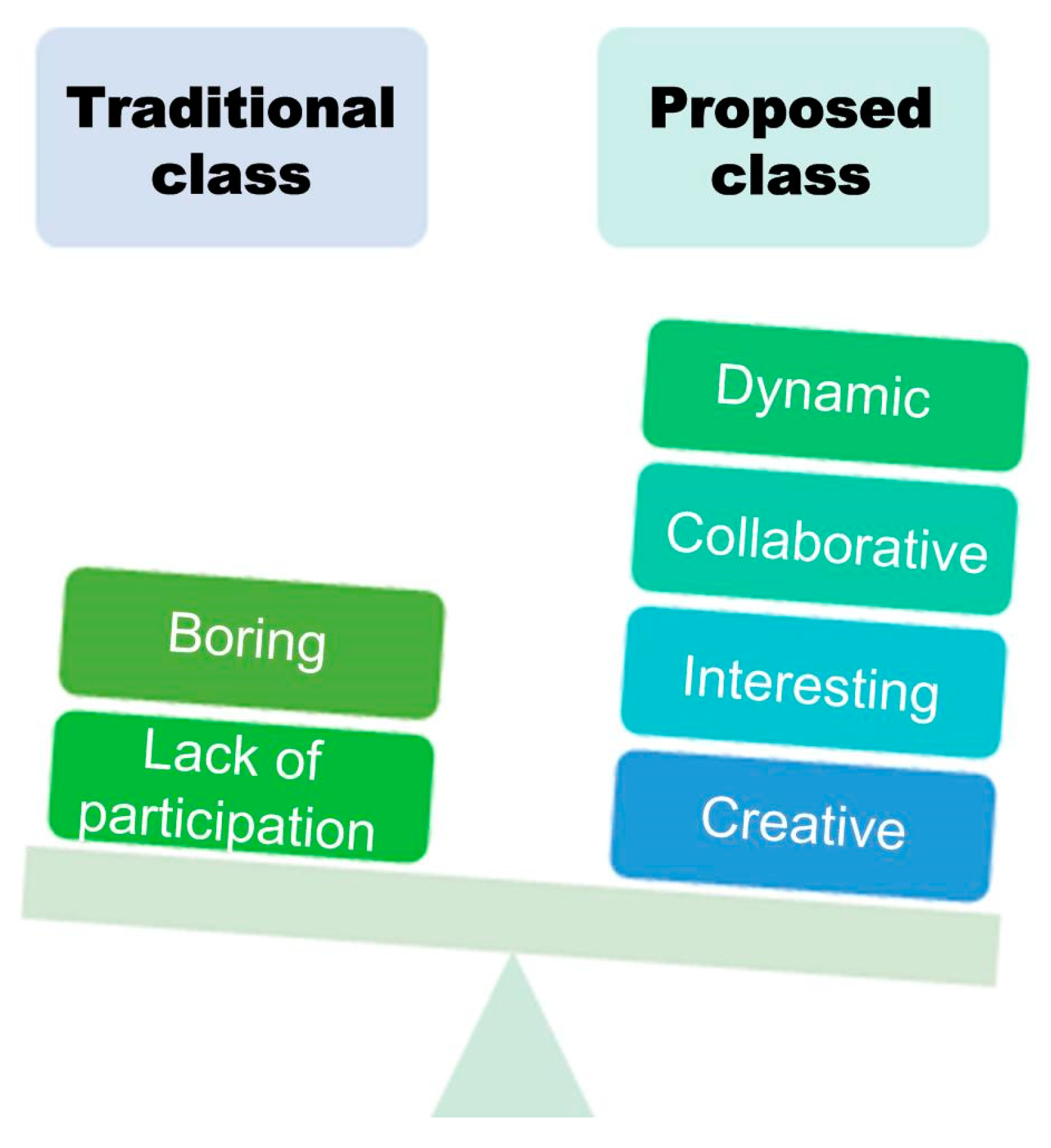

The traditional education system mainly focuses on memorizing, fostering a repetitive education instead of an active and participative one [46]. The student tends to be considered a recipient to transfer knowledge to rather than a future professional who will use the tools the university provides them with during their time in academia. The college students in traditional classes (Figure 2) gather information from the teacher until their examinations, when they try to reproduce the information with the highest accuracy [47]. To evaluate the effect of the proposed methodology on the students in comparison to traditional classes, two tasks which consisted of the presentation of different issues were carried out before and after the development of the proposed methodology by each student. The first task was performed on the basis of lectures led by the teacher, and the second task was conducted according to the proposed method, described below. Both tasks were evaluated and are compared in the results section.

Figure 2.

Comparison between traditional and proposed class models.

2.1.2. Proposed Class

This subsection provides a description of the methodology used in class. The proposal carried out in this research attempts to show evidence that there is an improvement through student involvement in the learning process. The way of obtaining this goal is by converting students in lectures for a short period of time where they must explain the lesson. The students are informed that the activity will be evaluated but will not be considered for the final qualification. In this way, the added stress of marks [48] can be avoided and the student can focus only on the activity evolution. The activity was performed by 90% of the students in the 2021/2022 course and by 100% of the students in the 2022/2023 course. Additionally, the students could withdraw from the activity at any time.

The proposed methodology is intended to drastically change the learning process and the expected acquired skills, avoiding the boredom described in Figure 1 for a more participative learning process. Figure 2 summarizes the proposed class proposal versus the traditional class. In the new proposal, the student plays an important role as the first actor in the teaching and learning process. As shown in Figure 2, students must prepare the lesson and research the topic, while in traditional classes the student was just a lesson listener. This change in the class process involves the students participating actively in the learning process, since they must master the subject in order to teach it. The students’ motivation increases since they play an important role in the class course, which makes them feel like an important part of the process rather than just a person being evaluated.

2.2. Methodology Description

The proposed methodology can be divided into different parts:

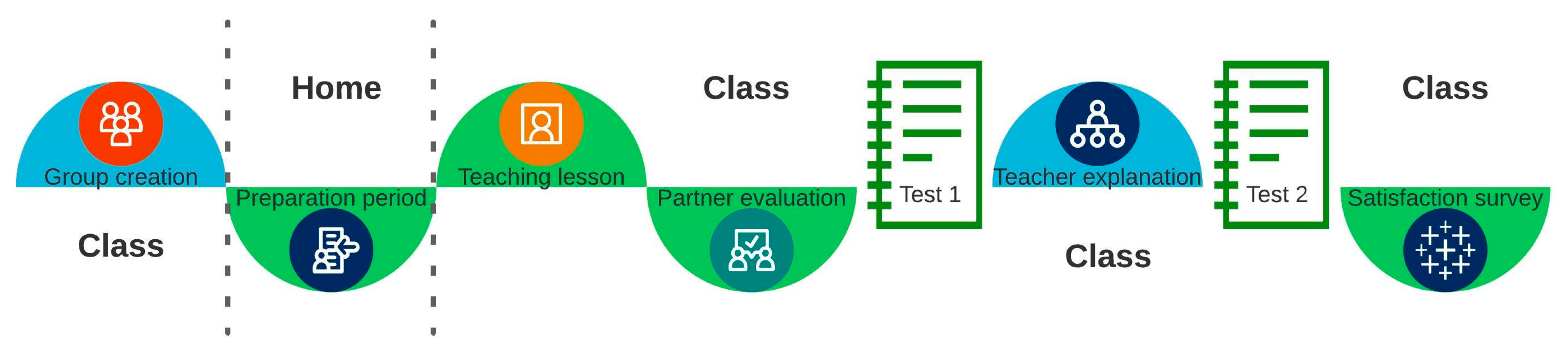

- Group creation. This is performed in the first class of the activity. A general view of the development of the activity is also introduced. The class is divided into two groups, which halves the number of students.

- Period of preparation. One week is provided for autonomous work preparation. Students must search, classify, and study the topic. It is indicated that they can use whatever resource they might need to explain different topics and that they can use a free explanation system. Furthermore, two hours of the class are used to discuss personal doubts about the activity.

- Mixing groups. On the day of the explanation of the different topics, random groups are formed. Those new groups are made with one student from the previous groups that halve the class. Therefore, the new group is based on two students, each with a different topic.

- Teaching lesson. Both members of the group explain their lesson. They are given 30 min for the explanation plus 15 min for questions.

- Partner evaluation. After the teaching activity, a short test of 5 min is carried out by the student who acted as a student, evaluating the other student’s class development while he was acting as a teacher.

- Test 1. A general test with simple questions about both topics is undertaken after the students’ partner evaluation.

- Teacher explanation. In the class following the activity, the teacher comments on the most important aspects of the two topics. Questions are answered, and mistakes from Test 1 are solved.

- Test 2. The state of training is assessed through a second evaluation.

- Satisfaction survey. After Test 2, a questionnaire about the activity is completed.

Students do not know the dates for Test 1 until they reach the point of the test. This way, this methodology’s learning process can be compared with classical learning, where the student studies information by heart at home. Figure 3 presents the methodology described, which was developed to evaluate student–teacher role reversal.

Figure 3.

Research process.

2.3. Sample

The NS students are mostly aged 21 to 25 years old and do not have previous work experience. NS is a specific subject that is only selected by one branch out of two. The number of students is adequate (below 15 in both academic years) for the implementation of this procedure because it makes it easier to control either the development or the results. Additionally, students do not have any previous connection with the subject or the subject topic.

2.4. Procedure

2.4.1. Topic Selection

The proposal outlined in this paper was performed at the University of Las Palmas de Gran Canaria in Spain. The Naval Engineering Bachelor’s has been declared by the university as strategic, meaning that it is relevant for the geographical and professional aspects in the region. We aimed to investigate how theoretical engineering subjects could be more interesting and participative. Finally, we chose NS for this research, mainly due to the teaching hours, the theoretical content, and the low level of interest generated among students in previous academic years. Large lectures have been previously assessed in similar experiences by other researchers with good results [49,50]. As stated previously, this new experience was developed during two academic courses (2021/2022 and 2022/2023) with different students. The proposed topics of both courses were changed to evaluate if the methodology was reproducible regardless of the issues. Table 1 shows the details related to the topics by course and group. The topics in the 2021/2022 course were based on accessible knowledge through books and websites. This information could be identified as “classical” since it was published more than 10 years ago. The topics presented in the 2022/2023 course were based on information published recently, one year ago. To develop this task, the lecturer provided the student with different sources of information, such a websites, books, YouTube videos, and a powerpoint model for developing the presentation.

Table 1.

Group topics for 2021/2022 and 2022/2023 academic years.

Table 1.

Group topics for 2021/2022 and 2022/2023 academic years.

| Group | Topic | Aim |

|---|---|---|

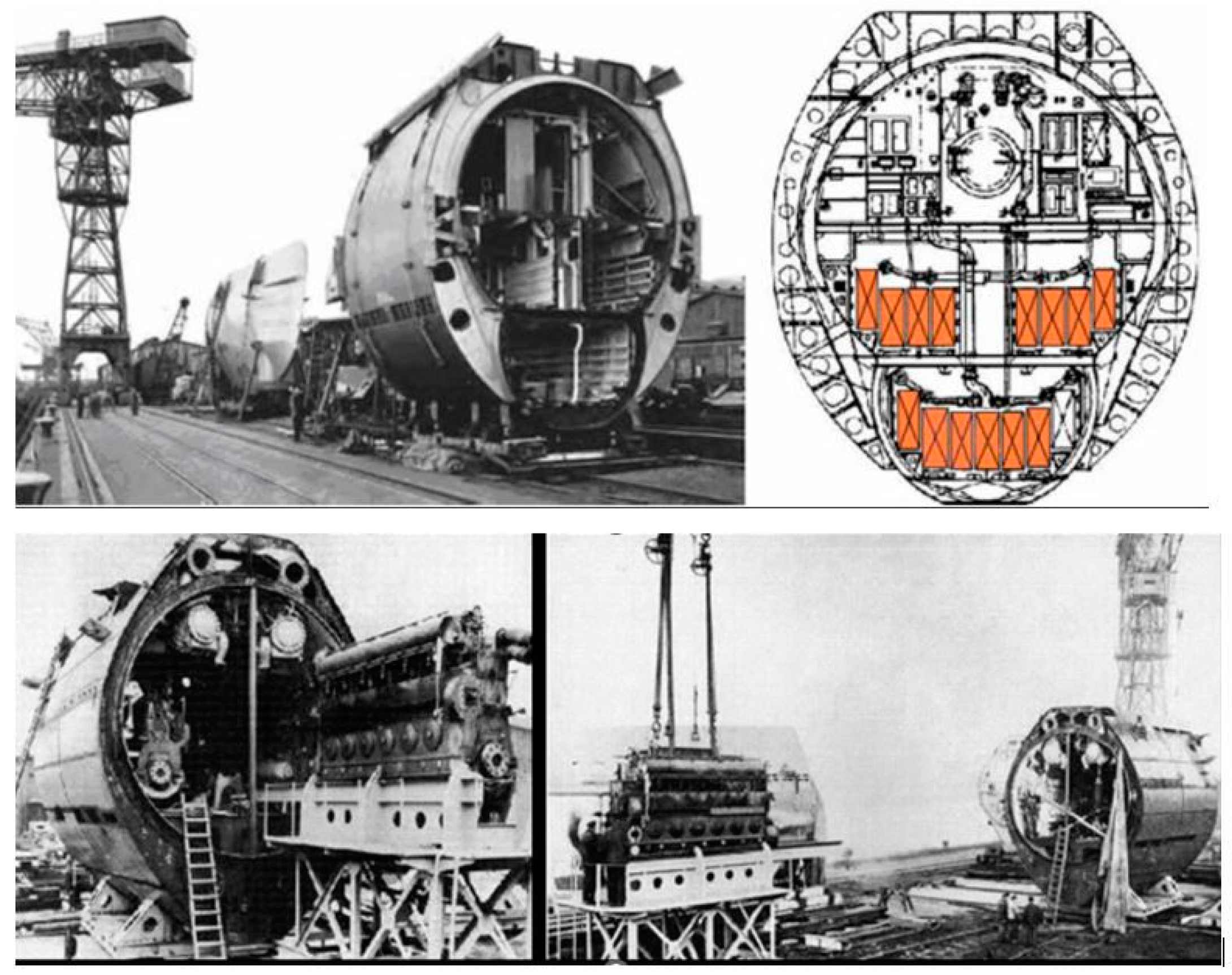

| Group A 2021/2022 | U-boat XXI (Figure 4) | Provide information about the building of the German Second World War Submarine |

| Group B 2021/2022 | Ship Work Break-down Structure (SWBS) | Explain the use of a system oriented to describe the shipbuilding products |

| Group A 2022/2023 | Building shipyards in Asia | Provide information about the most relevant shipyards in Asia during 2021 |

| Group B 2022/2023 | Building shipyards in Europe | Provide information about the most relevant shipyards in Europe during 2021 |

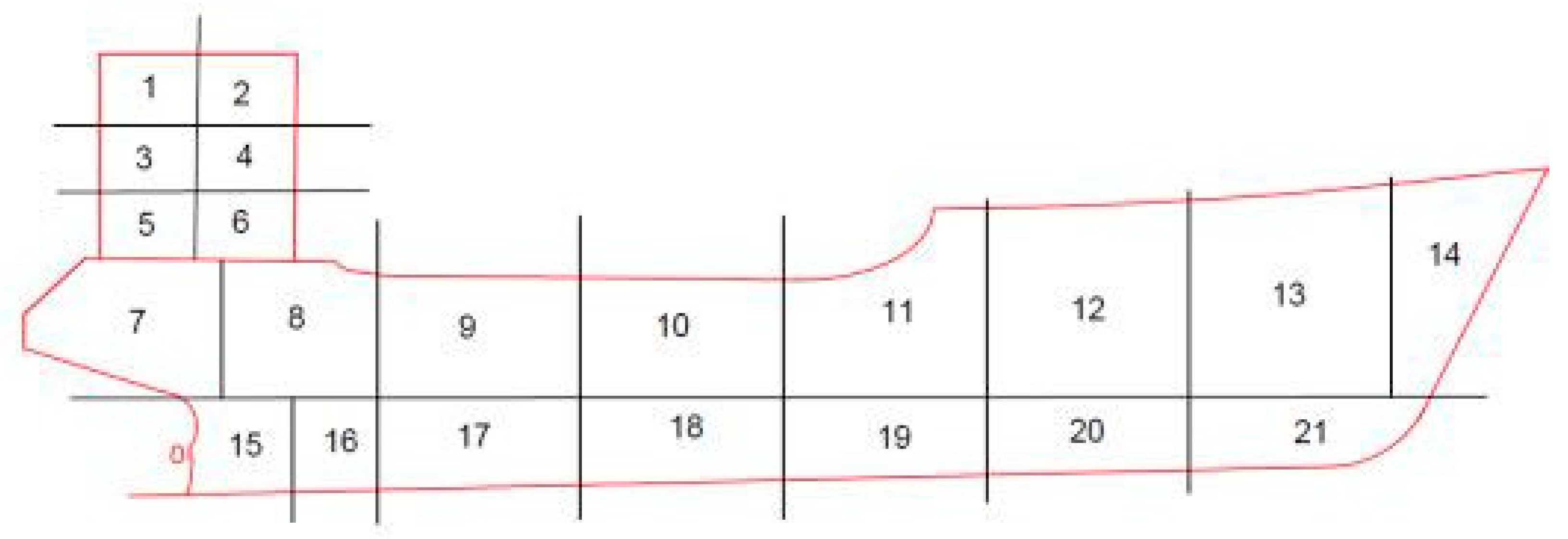

Figure 4.

Example of U-boat XXI building topic extracted from students’ presentation [51,52].

Figure 4.

Example of U-boat XXI building topic extracted from students’ presentation [51,52].

2.4.2. Group Distribution

The class was divided into two proportional groups to develop this activity. The groups were formed alphabetically. One half of the students constituted Group A, and the rest of them formed Group B. Each member of Group A was paired with a member of Group B who was randomly selected for the lesson explanation. During the 2 years of methodology implementation, there were less than 15 students, which allowed the students to better understand the proposal and the different issues related with the activity. In this context, the distribution was better controlled by the lecturer.

2.4.3. Topic Preparation and Oral Presentation

Despite oral presentation skills being deemed of extreme significance in the modern world of work and employers requiring highly communicative candidates for entry-level posts [53], engineering education has usually overlooked teaching these skills [54]. The content of the educational program in engineering is usually quite broad, and teachers do not have enough time in class to develop communication skills even though these skills are required in the students’ career [55]. To rectify this issue, students were provided with ideas, tips, and tools on the things “to do” and “not to do” in their topic preparation. Before the activity began, different digital resources, such as digital whiteboards, videos, or web links were described and explained by the lecturer. It was also emphasized that the presentation should be clear and focused on the main aspects of the topic. Furthermore, students were forbidden to read any notes during the oral presentation in order to ensure that the lesson was fully understood by the speaker [56], since in previous tasks, the students were accustomed to reading out segments which were transcribed from books or manuals text (Figure 5a). Furthermore, some rules related to exposition time for question time and activity format were also provided. For instance, the suggested presentation format is shown in Figure 5b. The main goal of the instructions detailed here was the correct development of the activity with a minimum quality. This requires that the students develop 30 min of speech in a clear and intelligible way. They were encouraged to perform this activity as if they were a professional lecturer or engineer presenting a project.

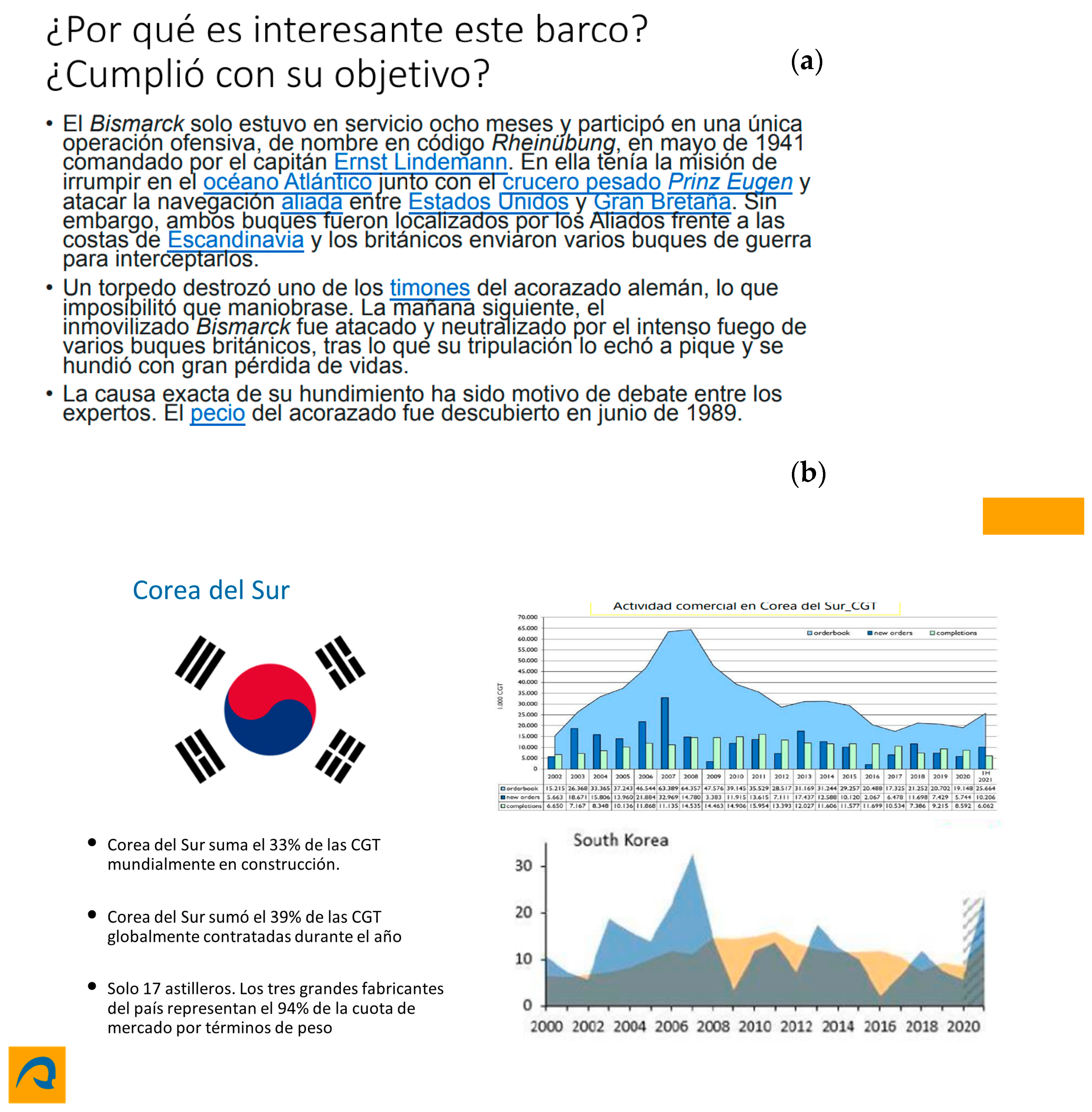

Figure 5.

Comparison between traditional class (a) versus proposed class (b). (a) describes the Bismarck boat, its importance in the Second World War and its sinking. There is too much text, and the slide is very complicated to understand. The student tends to read the slice. (b) analyzes the situation of the shipbuilding industry in South Korea. This slide has little text and many images, so it is clearer than (a). The students use the slice as reference guide to provide their speech.

2.4.4. Partner Evaluation

At the end of each lesson explanation, the member acting as a student must evaluate the student who plays the teacher’s role. The students are informed of this a few minutes before the beginning of the activity. Most students were nervous, leading to a greater interest in the activity. The evaluation consisted of six open-ended and quantitative questions. The questions were the following:

- PE1. Was the lesson well explained?

- PE2. Did the teacher (relative to the other member group student) clearly solve any doubts?

- PE3. What would you suggest to the teacher (relative to the other member group student) for improving their presentation?

- PE4. From 1 out of 10 (1 being the worst grade and 10 being the best grade), assess the quality of the other member’s lesson.

- PE5. From 1 out of 10 (1 being the worst grade and 10 being the best grade), evaluate the clarity and understanding of the other member’s answers to your questions.

- PE6. From 1 out of 10 (1 being the worst grade and 10 being the best grade), evaluate the teacher’s preparation for this activity.

All the questions were raised to quantify the level of interest and study developed by the student who plays the role of the lecturer. The open questions attempted to identify the weaknesses of each student, and the quantitative ones were used as a more specific evaluation of the lecturer.

2.4.5. Test 1

Once both groups had acted as teachers and had been evaluated individually by the other student, a test that included both topics was given. The goal of this test was to assess the degree of knowledge acquired by the students during the development of this activity. The questions about the most important issues of each topic were simple. Most of them were included in the students’ oral presentations while they were developing this activity.

2.4.6. Test 2

After Test 1, the two topics used in the methodology were re-explained by the lecturer. The idea is to re-enforce the principal aspects of the topic and solve doubts that may appear. After this explanation, a new test with short and conceptual questions was undertaken. The students’ progress regarding the previous test was identified in this second exam. The students had an extra week for the preparation and studying for this test.

2.4.7. Satisfaction Survey

To conclude the activity, students were asked to complete a questionnaire about their impressions of the activity. This questionnaire is called a satisfaction survey because its purpose is to identify the strengths and weaknesses of the activity from the students’ point of view and to get the students’ impressions. The survey includes open questions that were not compulsory to answer. The questions were as follows:

- HS1. Was this way of learning interesting to you?

- HS2. Would you change something from this methodology?

- HS3. What difficulties did you face with this activity?

- HS4. What was the easiest part of the activity?

- HS5. Free comments about this activity.

2.4.8. Data Analysis

Different analyses were carried out to quantify the effect of the new proposed methodology in the class. First, the results of the different surveys and tests were statistically analyzed, categorized, and grouped to provide a framework for the assessment and improvement of the teaching experience. Then, compulsory Test 1 and Test 2 were held with other optional questionnaires to quantify the results. Some students decided not to answer them. From these analyses, we hoped to see if a change of attitude, interest, and results appeared.

3. Results

In this section, we describe the results obtained by the students.

3.1. Participation

We achieved in both academic courses, 2021/2022 and 2022/2023, 100% student participation. Although some of the students initially showed their doubts about the new activities, they were eventually encouraged to take part in the proposed methodology because they considered the new activities to be more dynamic, attractive, and entertaining compared to previous traditional classes.

3.2. Task Comparison

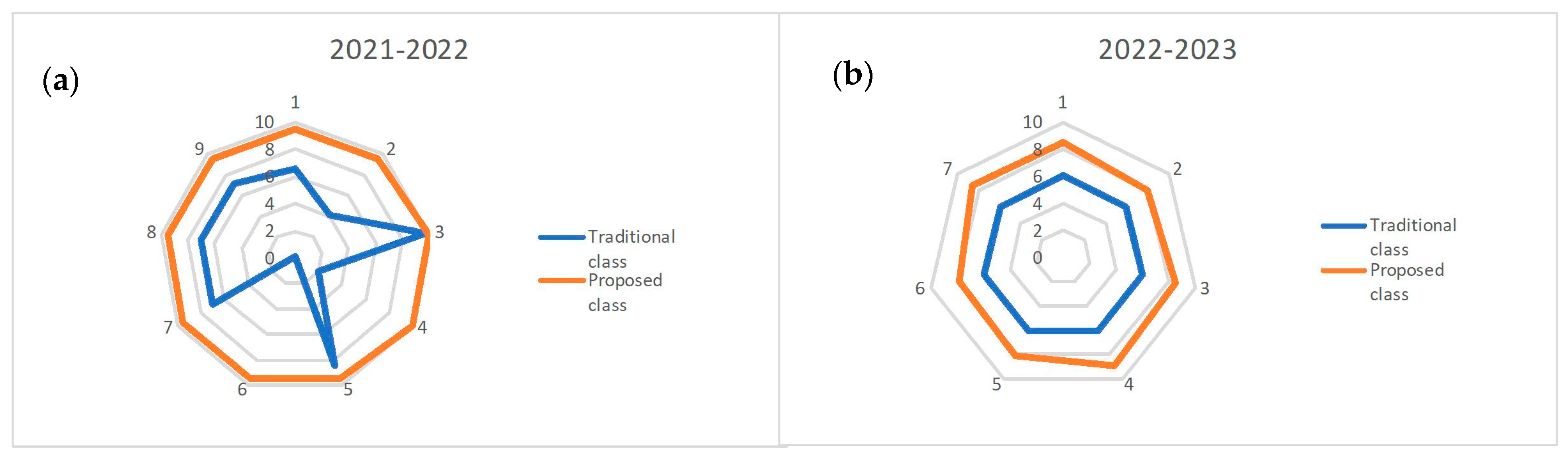

The marks obtained from the first task, based on the traditional classes, were 5.30 ± 3.08 and 6.14 ± 1.18 (out of 10) in the 2021–2022 and 2022–2023 academic years, respectively. The same groups were also evaluated following the proposed methodology, and they improved their scores in the second task, following the new methodology described, with results that varied from 8.65 ± 3.05 in 2021–2022 to 8.30 ± 0.36 in 2022–2023. These results can also be seen individually in Figure 6, where one student’s grades are presented for two different methodologies, the traditional and the proposed one.

Figure 6.

Spider chart characterizing the marks comparison of traditional/proposed classes for 2021/2022 (a) and 2022/2023 (b) academic years.

According to the results, it seems that the proposed activities increased the students’ marks by two points (out of 10) on average. Although we found major differences between both academic years in the first task, the standard deviation was also reduced in 2022–2023 by over 0.80 points when performing the second task. Moreover, the high differences in the first task (1.84) were drastically reduced (0.35) in the second task between the two consecutive academic years. These results indicate that the new methodology not only improves the average marks but also achieves a more homogenous group. Furthermore, to test the significance of the differences in the results for the tasks following the proposed methodology and the conventional traditional class, we performed a one-way ANOVA test using SPSS. As shown in Table 2 and Table 3, the p-values obtained for both academic years were below 0.05, which means that it was impossible to deny that the two samples (student-centered and teacher-centered tasks) had the same median for a significance value of 0.05.

Table 2.

ANOVA test (n = 9) for task comparison between traditional/proposed class in 2021–2022 course (df is the degrees of freedom, F is the statistic of Fisher–Snedecor, and Sig. is the significance).

Table 3.

ANOVA test (n = 7) for task comparison between traditional/proposed class in 2022–2023 course (df is the degrees of freedom, F is the statistic of Fisher–Snedecor, and Sig. is the significance).

3.3. Partner Evaluation Results

The results are summarized in Table 4.

Table 4.

Partner evaluation results.

Based on the results presented in Table 4, it is appreciable that the students took seriously the preparation and the development of the activity, which suggests a high level of maturity and responsibility. The greater interaction between classmates strengthened relationships in the class, which improved the social environment and made sessions by students more attractive. Furthermore, students remarked that they detected some nervousness in their colleagues when they were acting as a teacher. This nervousness sometimes diminished the quality of the explanation. They were also surprised by the different resources used by other colleagues during the class. Some of them tended to use several videos, others used graphs, and others even interacted with their colleague, asking questions about what he/she was explaining.

In summary, every student conducted the presentation in a different way, showing not only the desired active learning effect but also the enhancement of other competencies, knowledge, and skills [57]. Although the topic was similar for the two group members, each student provided different points of view on the issue and contributed new features of the topic, such as related news, or indirect aspects that were affected, somehow, by the main text. No overlap was identified between the different presentations. Furthermore, it was interesting to see how some of them linked the topic with their final Bachelor’s project. For instance, Figure 7 illustrates how one student showed how the building of a U-boat could be applied to his own final ship project proposing a ship division and its building proposal. Results of the activity at this point show high student preparation of the topic.

Figure 7.

Building sections in a ship proposed by a student.

3.4. Test 1 and Test 2 Results

All the students in both courses passed both tests. In Test 1, the average result was 7.5, and in Test 2, it was 9, which demonstrated very satisfactory marks in NS. It was a great success that all the students could pass Test 1 without additional studying, just with the explanation given by their partners. This is important, not only because their preparation was fairly good in all cases but also because the students learned from their partners, and they showed interest in the others.

The increase in the marks in Test 2 for most students was attributed to the doubts solved by the lecturer and the studying time. This is the only new parameter that changed between Test 1 and Test 2. The students tended to ask more questions compared with traditional classes due to greater confidence in their partner, showing their real interest in the topic.

3.5. Satisfaction Survey

The results of the satisfaction survey (Table 5) provided valuable information about the impressions of the students and made evident that most of them appreciated this methodology in their learning process. However, some concerns about time preparation were found. This might be related to the fact that students were practicing in companies during the morning; therefore, their time was limited. Other students were just studying subjects from previous courses or doing their final projects. Almost half of the students were not comfortable with public speaking, despite being in the last Bachelor’s course, and despite the fact that all the subjects from previous academic years consider clear and efficient oral communication to be a basic transversal competence.

Table 5.

Satisfaction survey results.

4. Discussion

The proposed methodology highlighted that the students felt interested and motivated when involved in new activities [58,59] and that their participation and greater representativeness were also fundamental for the success among them [60]. The lecturer received emails from around 20% of students asking questions about the activity, and half of the students went to the lecturer’s office for tutorial advice. This situation was new for both students and the lecturer because the students did not interact with the lecturer in this way while classic lessons were developed. The doubts were mostly about novelties or curiosities that the students found during the preparation of the activity. A relevant aspect that the lecturer realized in this process was a lack of self-esteem and confidence in the students’ work. These feelings occurred mainly because they faced an activity for the first time at the Bachelor’s level where they were responsible for good performance. Despite these feelings, this attitude changed noticeably throughout the activity’s execution. We also noticed that increasing the relationship between lecturer and student highly improves students’ self-esteem and academic performance, which aligns with previous research [61].

The improvement of the students’ marks was very meaningful in both courses, reaching differences over two points. Better academic performance with similar experiences was also highlighted in previous research [62,63,64,65]. Likewise, the standard deviations were lower with the proposed methodology, ensuring a better overall level of the class, which [25,66] also indicated. As pointed out by Hanson et al. [67], students who are at a similar intellectual level provide a more productive interaction than teacher–student lessons, leading to greater understanding.

The proposed methodology enhanced not only the students’ marks but also the class environment. The students were forced to increase their relationships both in the preparation of the activities and also in the public presentation of the issues. This change of relationship resulted in more comfortable and engaging sessions and strengthening bonds of cooperation between classmates. This fact was also highlighted by previous studies in higher education [67,68,69]. Besides the easier acquisition of new knowledge, other benefits that were detected in this study have been highlighted by other authors: increasing attendance [70], leadership [71] and other professional engineering skills [72], autonomy and time optimization [73], technology utilization [74], and even anxiety reduction [75].

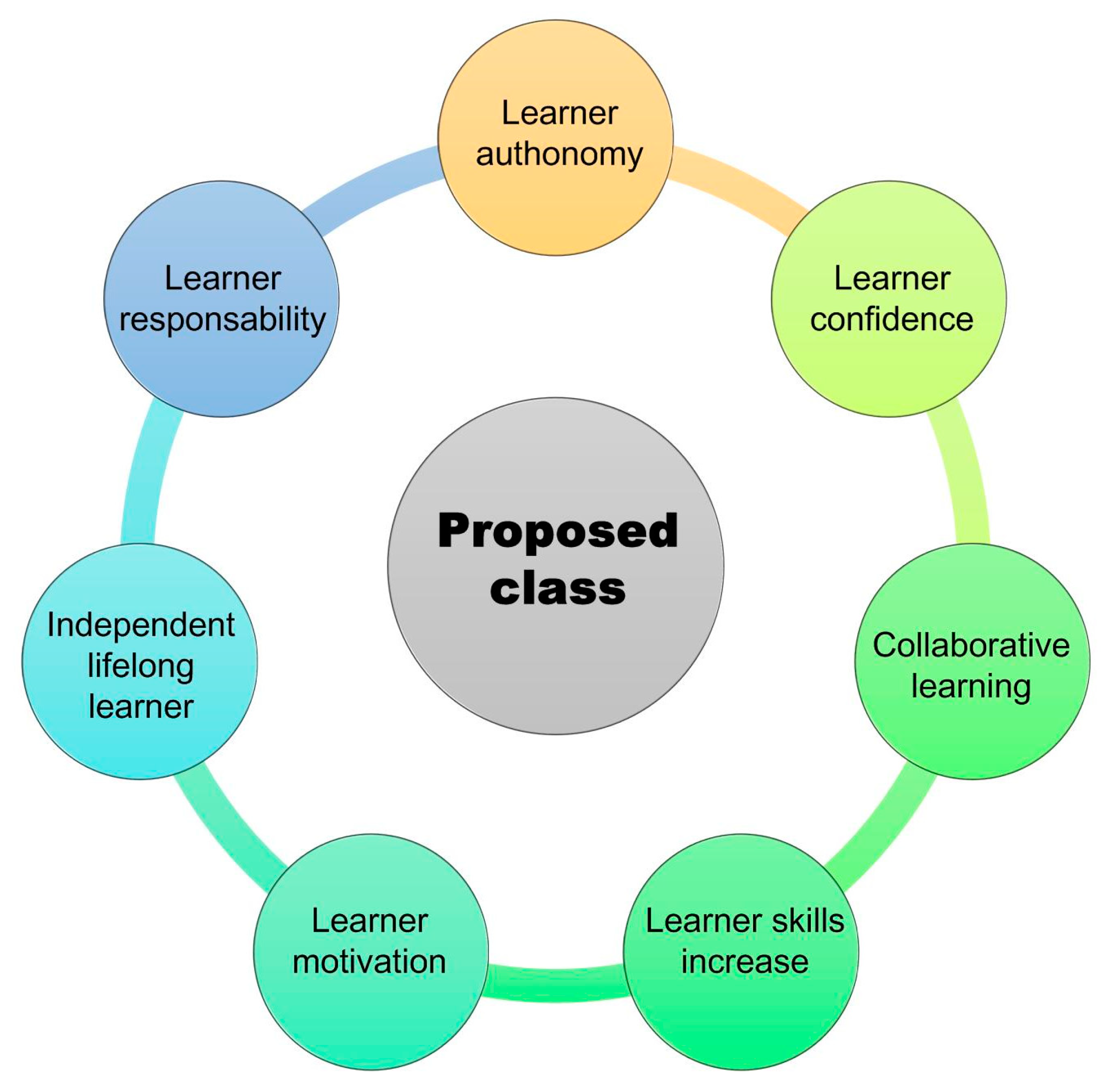

Results also indicate that this kind of activity is important to re-enforce students’ confidence and autonomous work. Most of the students mentioned in this paper became engineers 6 months after passing this subject, where they needed to face new tasks and professional demands and carry them out leading a group of workers from different disciplines. Therefore, this activity was not only good for keeping them interested in a theoretical subject but also for strengthening some of their skills. Figure 8 illustrates the different skills that the students might achieve by taking part in the proposed methodology.

Figure 8.

Key points of the proposed class.

The largest number of complaints related to the development of the proposed methodology had to do with the nervousness the students felt in public speaking. In Spain, communication skills still represent a major challenge within the university system [76]. Likewise, about one-quarter of the students found that the activity took up time they would otherwise spend on other tasks. The lack of time management and difficulties in study organization were also reported in other research about engineering [77,78].

Although the benefits of this methodology have clearly been positive and enriching, the groups in each academic year were small, and the individual dedication on the part of the teacher was enough to for the whole class to attend. However, more students might hamper the achievement of some of the goals. Furthermore, the profile of students in naval engineering is usually rather homogenous; therefore, future research should focus on other engineering degrees and Master’s studies, where professionals from various sectors are frequently part of the student body. Additionally, further evaluations should focus on more practical subjects, where theoretical content is lower than in this study.

5. Conclusions

The overload of tasks in the last course of the engineering Bachelor’s can certainly diminish the interest of the students in theoretical subjects. Together with the development of the final degree project, this puts high pressure on them. Therefore, the different difficulties faced by a student in their last year makes essential the adaptation of the teaching into a more proactive manner that is focused on the student’s role. The main goal of the methodology described was putting the students at the center of the learning process to attract and maintain their interest in the lessons, empowering them towards a more autonomous and professional profile. The voluntary participation of 100% of the class indicated a considerable interest in the development of the activity. Furthermore, other skills were boosted in this activity, such as an increase in self-esteem. Although some students felt nervous about their presentation, especially about speaking in public, they nonetheless performed highly. Some complaints about the students’ nervousness were pointed out in the surveys, but it became clear that this methodology should be more commonly used to develop and refine other transversal skills.

We also found that this teaching activity encourages the students’ creativity and resourcefulness since they were free to use any kind of methodology in their presentation. This is very interesting because the students are free to develop the activity and expand their curiosity. Indeed, this is a valuable aspect in some professions, where creativity plays an important role, such as in the engineering field. The engineering field is a quite competitive world where future professionals face activities without previous knowledge, which is what makes the proposed activity beneficial, that is, to work on those skills that will be used in future. This skill is not innate, so it needs to be practiced in advance, and the university should take part in training professionals both in knowledge and skills.

In Figure 9, some of the main aspects that are treated in the different methodological classes are presented in a balance figure. In this balance figure, we illustrate that the proposed methodology has fewer drawbacks in general than the traditional one, reinforcing many necessary skills for engineering students. Transversal skills, such as creative work, will be valuable once the students are professionals, which might be an advantage in comparison with other professionals that do not have these skills.

Figure 9.

Summary comparison of results between traditional and proposed classes.

Finally, this methodology has proven to be a good way of engaging the class, making it more dynamic. Therefore, it can be applied to a wide variety of different subjects in other university studies, not only in the engineering field.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.R.D.O. and J.P.-S.; methodology, H.R.D.O.; software, H.R.D.O. and J.P.-S.; validation, H.R.D.O., F.P.-A. and J.P.-S.; formal analysis, H.R.D.O. and J.P.-S.; investigation, H.R.D.O.; resources, H.R.D.O.; data curation, H.R.D.O., F.P.-A. and J.P.-S.; writing—original draft preparation, H.R.D.O., F.P.-A. and J.P.-S.; writing—review and editing, H.R.D.O., F.P.-A. and J.P.-S.; visualization, H.R.D.O. and J.P.-S.; supervision, H.R.D.O. and J.P.-S.; project administration, H.R.D.O. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

All subjects gave their informed consent for inclusion before they participated in the study. Furthermore, all participants were fully informed that the anonymity was assured, as well as why the research was being conducted. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and ethical approval was not required because the protocol in our university is only mandatory when using biological samples or personal data (not in our case). We attach the ethics policy in University of Las Palmas de Gran Canaria: https://www.ulpgc.es/vinvestigacion/ceih (accessed on 18 February 2023).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Díaz, F.M.d.M. Metodologías de Enseñanzas y Aprendizaje Para el Desarrollo de Competencias: Orientaciones Para el Profesorado Universitario Ante el Espacio Europeo de Educación Superior; Alianza. 2006. Available online: https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/libro?codigo=293088 (accessed on 18 February 2023).

- Canaleta, X.; Vernet, D.; Vicent, L.; Montero, J.A. Master in Teacher Training: A real implementation of Active Learning. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2014, 31, 651–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abad-Segura, E.; González-Zamar, M.D. Análisis de las competencias en la educación superior a través de flipped classroom. RIEOEI 2019, 80, 29–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akçayır, G.; Akçayır, M. The flipped classroom: A review of its advantages and challenges. Comput. Educ. 2018, 126, 334–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kokotsaki, D.; Menzies, V.; Wiggins, A. Project-based learning: A review of the literature. Improv. Sch. 2016, 19, 267–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onyon, C. Problem-based learning: A review of the educational and psychological theory. Clin. Teach. 2012, 9, 22–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Sánchez, J.; Senent-Aparicio, J.; Jimeno-Sáez, P. The application of spreadsheets for teaching hydrological modeling and climate change impacts on streamflow. Comput. Appl. Eng. Educ. 2022, 30, 1510–1525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nah, F.F.-H.; Zeng, Q.; Telaprolu, V.R.; Ayyappa, A.P.; Eschenbrenner, B. Gamification of Education: A Review of Literature. In HCI in Business; Springer: Cham, Seitzerland, 2014; pp. 401–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felder, R.M.; Brent, R. How to Improve Teaching Quality. Qual. Manag. J. 1999, 6, 9–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douglas, J.; Douglas, A. Evaluating Teaching Quality. Qual. High. Educ. 2006, 12, 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rimm-Kaufman, S.E.; Hamre, B.K. The Role of Psychological and Developmental Science in Efforts to Improve Teacher Quality. Teach. Coll. Rec. 2010, 112, 2988–3023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broder, J.M.; Dorfman, J.H. Determinants of teaching quality: What’s important to students? Res. High Educ. 1994, 35, 235–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salgado, S.; Au-Yong-Oliveira, M. Student Burnout: A Case Study about a Portuguese Public University. Educ. Sci. 2021, 11, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ter Beek, M.; Wopereis, I.; Schildkamp, K. Don’t Wait, Innovate! Preparing Students and Lecturers in Higher Education for the Future Labor Market. Educ. Sci. 2022, 12, 620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lomba, E.A.; Alves, J.M.; Cabral, I. Systematic Literature Review of Innovative Schools: A Map and a Characterization from Which We Learn. Educ. Sci. 2022, 12, 700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markham, T.; Larmer, J.; Ravitz, J.L. Project Based Learning Handbook: A Guide to Standards-Focused Project Based Learning for Middle and High School Teachers; Buck Institute for Education: Novato, CA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Rasul, S.; Bukhsh, Q.; Batool, S. A study to analyze the effectiveness of audio visual aids in teaching learning process at uvniversity level. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2011, 28, 78–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldevenites, E.V.L.; Sánchez, E.E.L.; Lucero, S.I. El uso de la plataforma de videos Tik Tok como recurso pedagógico de enseñanza multidisciplinaria. In Proceedings of the VIII Jornadas Iberoamericanas de Innovación Educativa en el Ámbito de las tic y LAS TAC (INNOEDUCATIC 2021), Virtual, 18–19 November 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Zachos, G.; Paraskevopoulou-Kollia, E.-A.; Anagnostopoulos, I. Social Media Use in Higher Education: A Review. Educ. Sci. 2018, 8, 194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peruta, A.; Shields, A.B. Social media in higher education: Understanding how colleges and universities use Facebook. J. Mark. High. Educ. 2017, 27, 131–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dabner, N. ‘Breaking Ground’ in the use of social media: A case study of a university earthquake response to inform educational design with Facebook. Internet High. Educ. 2012, 15, 69–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thoonen, E.E.J.; Sleegers, P.J.C.; Peetsma, T.T.D.; Oort, F.J. Can teachers motivate students to learn? Educ. Stud. 2011, 37, 345–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gynnild, V.; Holstad, A.; Myrhaug, D. Identifying and promoting self-regulated learning in higher education: Roles and responsibilities of student tutors. Mentor. Tutoring Partnersh. Learn. 2008, 16, 147–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunhaver, S.R.; Korte, R.F.; Barley, S.R.; Sheppard, S.D. Bridging the Gaps between Engineering Education and Practice. In US Engineering in a Global Economy; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2018; pp. 129–163. Available online: https://www.nber.org/books-and-chapters/us-engineering-global-economy/bridging-gaps-between-engineering-education-and-practice (accessed on 18 February 2023).

- Castedo, R.; López, L.M.; Chiquito, M.; Navarro, J.; Cabrera, J.D.; Ortega, M.F. Flipped classroom—Comparative case study in engineering higher education. Comput. Appl. Eng. Educ. 2019, 27, 206–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenwright, D.; Dai, W.; Osborne, E.; Gladman, T.; Gallagher, P.; Grainger, R. “Just tell me what I need to know to pass the exam!” Can active flipped learning overcome passivity? TAPS 2017, 2, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ridder-Symoens, H. A History of the University in Europe. Available online: https://www.cambridge.org/core/series/history-of-the-university-in-europe/C47CA1B6629F8A753C3330F38EC43435 (accessed on 18 February 2023).

- Konopka, C.L.; Adaime, M.B.; Mosele, P.H. Active Teaching and Learning Methodologies: Some Considerations. Creat. Educ. 2015, 6, 1536–1545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Csikszentmihalyi, M. Beyond Boredom and Anxiety, 1st ed.; Jossey-Bass Publishers: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Cziksentmihalyi, M. Flow–The Psychology of Optimal Experience. 1990. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/224927532_Flow_The_Psychology_of_Optimal_Experience (accessed on 18 February 2023).

- Whitman, N.A. Peer Teaching: To Teach Is to Learn Twice; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Goldschmid, B.; Goldschmid, M.L. Peer teaching in higher education: A review. High Educ. 1976, 5, 9–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aslan, S. Is Learning by Teaching Effective in Gaining 21st Century Skills? The Views of Pre-Service Science Teachers. Educ. Sci. Theory Pract. 2015, 15, 1441–1457. [Google Scholar]

- Grzega, J.; Schöner, M. The didactic model LdL (Lernen durch Lehren) as a way of preparing students for communication in a knowledge society. J. Educ. Teach. 2008, 34, 167–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, V.; Malone, K.; Moore, P.; Russell-Webster, T.; Caulfield, R. Peer teaching medical students during a pandemic. Med. Educ. Online 2020, 25, 1772014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sotgiu, M.A.; Bandiera, P.; Mazzarello, V.; Saderi, L.; Montella, A.; Moxham, B.J. Medical Student Perceptions of Near Peer Teaching within an Histology Course at the University of Sassari, Italy. Educ. Sci. 2022, 12, 527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdulrahman, K.A.B.; Alfadhel, M.A.; Alswayed, K.E.; Al-Thakfan, N.A. Student as a Clinical Teacher: Evaluation of Peer Teaching Experience in Clinical Education. Med. Res. Arch. 2022, 10, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fletcher, A.; Kickbusch, S.; Huijser, H. Authentic learning using mobile applications and contemporary geospatial information requirements related to Environmental Science. J. Geogr. High. Educ. 2022, 46, 185–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solís, P.; Huynh, N.T.; Huot, P.; Zeballos, M.; Ng, A.; Menkiti, N. Towards an overdetermined design for informal high school girls’ learning in geospatial technologies for climate change. Int. Res. Geogr. Environ. Educ. 2019, 28, 151–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, B.N.; McCarthy, P.C.; Wright, A.M.; Schutz, H.; Boersma, K.S.; Shepherd, S.L.; Manning, L.A.; Malisch, J.L.; Ellington, R.M. From panic to pedagogy: Using online active learning to promote inclusive instruction in ecology and evolutionary biology courses and beyond. Ecol. Evol. 2020, 10, 12581–12612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maccabe, R.; Fonseca, T.D. ‘Lightbulb’ moments in higher education: Peer-to-peer support in engineering education. Mentor. Tutoring Partnersh. Learn. 2021, 29, 453–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Benedetti, M.; Plumb, S.; Beck, S.B.M. Effective use of peer teaching and self-reflection for the pedagogical training of graduate teaching assistants in engineering. Eur. J. Eng. Educ. 2022, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz-García, M.A.; Moreda, G.P.; Hernández-Sánchez, N.; Valiño, V. Student Reciprocal Peer Teaching as a Method for Active Learning: An Experience in an Electrotechnical Laboratory. J. Sci. Educ. Technol. 2013, 22, 729–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Blake, J. Asynchronous Peer Teaching Using Student-Created Multimodal Materials. IJIET 2021, 11, 286–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Hamad, M.Q.; Mbaidin, H.O.; AlHamad, A.Q.M.; Alshurideh, M.T.; Kurdi, B.H.A.; Al-Hamad, N.Q. Investigating students’ behavioral intention to use mobile learning in higher education in UAE during Coronavirus-19 pandemic. Int. J. Data Netw. Sci. 2021, 321–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galván-Cardoso, A.; Siado-Ramos, E. Educación Tradicional: Un modelo de enseñanza centrado en el estudiante. CIENCIAMATRIA 2021, 7, 962–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tonuci, F. ¿Enseñar O Aprender?: La escuela Como Investigación Quince Años Después: 009; IRIF, SL-Edit.: Graó, Spain, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Tejeiro, R.; Gómez-Vallecillo, J.L.; Romero, A.F.; Pelegrina, M.; Wallace, A.; Emberley, E. Summative self-assessment in higher education: Implications of its counting towards the final mark. Electron. J. Res. Educ. Psychol. 2012, 10, 789–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Förster, M.; Maur, A.; Weiser, C.; Winkel, K. Pre-class video watching fosters achievement and knowledge retention in a flipped classroom. Comput. Educ. 2022, 179, 104399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velegol, S.B.; Zappe, S.E.; Mahoney, E. The Evolution of a Flipped Classroom: Evidence-Based Recommendations. Adv. Eng. Educ. 2015, 4, n3. Available online: https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ1076140 (accessed on 18 February 2023).

- Uboot Tipo XXI. Available online: https://www.u-historia.com/uhistoria/historia/articulos/21historia/tipo21/tipoXXI.htm (accessed on 18 February 2023).

- La Construcción en Secciones del Submarino del Tipo XXI. Available online: https://www.u-historia.com/uhistoria/tecnico/articulos/21tecnico/secciones/secciones.htm (accessed on 18 February 2023).

- Campbell, K.S.; Mothersbaugh, D.L.; Brammer, C.; Taylor, T. Peer versus Self Assessment of Oral Business Presentation Performance. Bus. Commun. Q. 2001, 64, 23–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kakepoto, I.; Habil, H.; Omar, N.A.M.; Said, H. Factors that Influence Oral Presentations of Engineering Students of Pakistan for Workplace Environment. Inf. Knowl. Manag. 2012, 2, 70. [Google Scholar]

- Sheth, T.D. Communication Skill: A Prerequisite for Engineers. Int. J. Stud. Engl. Lang. Lit. 2015, 3, 51–54. [Google Scholar]

- Alonso, D.M.; García, N.B.; Nieto, J.E.S. El proceso de creación curricular en estudiantes de Educación Secundaria. Una Indagación Narrat. Profr Rev. Currículum Form. Del Profr. 2019, 23, 377–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bušljeta, R. Effective Use of Teaching and Learning Resources. Czech-Pol. Hist. Pedagog. J. 2013, 5, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez-DeHass, A.R.; Willems, P.P.; Holbein, M.F.D. Examining the Relationship between Parental Involvement and Student Motivation. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 2005, 17, 99–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abernathy, T.V.; Vineyard, R.N. Academic Competitions in Science: What Are the Rewards for Students? Clear. House A J. Educ. Strateg. Issues Ideas 2001, 74, 269–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domínguez, A.; Saenz-de-Navarrete, J.; de-Marcos, L.; Fernández-Sanz, L.; Pagés, C.; Martínez-Herráiz, J.-J. Gamifying learning experiences: Practical implications and outcomes. Comput. Educ. 2013, 63, 380–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyadanu, S.D.; Garglo, M.Y.; Adampah, T.; Garglo, R.L. The Impact of Lecturer-Student Relationship on Self-Esteem and Academic Performance at Higher Education. JSSS 2014, 2, 264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres-Martín, C.; Acal, C.; El-Homrani, M.; Mingorance-Estrada, Á.C. Implementation of the flipped classroom and its longitudinal impact on improving academic performance. Educ. Tech. Res. Dev. 2022, 70, 909–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, R.; Perényi, Á.; Birdthistle, N. The positive relationship between flipped and blended learning and student engagement, performance and satisfaction. Act. Learn. High. Educ. 2021, 22, 97–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliván Blázquez, B.; Masluk, B.; Gascon, S.; Fueyo Díaz, R.; Aguilar-Latorre, A.; Artola Magallón, I.; Magallón Botaya, R. The use of flipped classroom as an active learning approach improves academic performance in social work: A randomized trial in a university. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0214623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lax, N.; Morris, J.; Kolber, B.J. A partial flip classroom exercise in a large introductory general biology course increases performance at multiple levels. J. Biol. Educ. 2017, 51, 412–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, A.P.; Castedo, R.; Alarcón, C.; Dios, K.S.; Chiquito, M.; España, I.; López, L.M. Development of Flipped Classroom model to improve the students’ performance. In Proceedings of the Sixth International Conference on Technological Ecosystems for Enhancing Multiculturality, New York, NY, USA, 24–26 October 2018; pp. 703–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.H. On the relationships between behaviors and achievement in technology-mediated flipped classrooms: A two-phase online behavioral PLS-SEM model. Comput. Educ. 2019, 142, 103653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yılmaz, F.G.K.; Yılmaz, R. Exploring the role of sociability, sense of community and course satisfaction on students’ engagement in flipped classroom supported by facebook groups. J. Comput. Educ. 2023, 10, 135–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, J. Gamifying the flipped classroom: How to motivate Chinese ESL learners? Innov. Lang. Learn. Teach. 2020, 14, 421–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahin, A.; Cavlazoglu, B.; Zeytuncu, Y.E. Flipping a College Calculus Course: A Case Study. J. Educ. Technol. Soc. 2015, 18, 142–152. [Google Scholar]

- Cherif, H.A. Peer Teaching in Small Group Setting. Forw. Excell. 1993, 1, 5–6. [Google Scholar]

- Mok, H.N. Teaching tip: The flipped classroom. J. Inf. Syst. Educ. 2014, 25, 7–11. [Google Scholar]

- Colomo-Magaña, E.; Soto-Varela, R.; Ruiz-Palmero, J.; Gómez-García, M. University Students’ Perception of the Usefulness of the Flipped Classroom Methodology. Educ. Sci. 2020, 10, 275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, H.-M.; Hsieh, P.-J.; Uden, L.; Yang, C.-H. A multilevel investigation of factors influencing university students’ behavioral engagement in flipped classrooms. Comput. Educ. 2021, 175, 104318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carpenetti, D.W. Peer Teaching in General Chemistry: Benefits to Information Retention and Lowered Student Anxiety. North Carol. Community Coll. J. Teach. Innov. 2022, 2, 21–42. [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz Moral, R.; García de Leonardo, C.; Cerro Pérez, A.; Caballero Martínez, F.; Monge Martín, D. Barriers to teaching communication skills in Spanish medical schools: A qualitative study with academic leaders. BMC Med. Educ. 2020, 20, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, R.V.; Blair, E. Impact of Time Management Behaviors on Undergraduate Engineering Students’ Performance. SAGE Open 2019, 9, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swart, A.J.; Lombard, K.; de Jager, H. Exploring the relationship between time management skills and the academic achievement of African engineering students—A case study. Eur. J. Eng. Educ. 2010, 35, 79–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).