1. Introduction

The origins of social pedagogy can be found in Germany in the 1840s, closely related to care and social work for child and youth welfare. However, it is from the Second World War onwards that this concept begins to spread to more countries due to the social problems arising from the war, and the processes of modernization and industrialization that take place following it. The expansion of social pedagogy in the rest of the world has developed in different ways depending on the needs of each country in relation to the welfare system, as well as the social, political, economic and cultural conditions [

1,

2].

In general terms, social pedagogy is conceptualized as a science that studies the interaction between learning, human qualities and social behaviors. Thus, social pedagogy is understood to be a discipline within the social sciences and education, which is formulated as a field of professional practice through which education responds to the needs and problems that arise in society, and with a direct relationship with social work [

1,

3].

The main purpose of social pedagogy is to promote the integration of people so that they have real participation in society and can be active citizens, with the aim of responding to social exclusion, through educational means [

1]. However, social pedagogy is an innovative and complex knowledge, lacking a general and unified theory, which makes it difficult to make a universally accepted conceptualization [

4,

5].

As mentioned above, in each country there are different conceptualizations and traditions of social pedagogy. Some of the most significant examples are: Sweden, Finland, Denmark, Norway and some Scandinavian countries, where the society is based on the Nordic model and social pedagogy is contextualized in the professional social care system [

1]. In the English-speaking context there is no historical background on which social pedagogy can be sustained as it is recent, so it has focused on child care, youth and social work, and community development [

1,

2]. In Poland, social pedagogy is understood as the theoretical basis of social work, so it is responsible for providing answers to educational, cultural and educational health care. In Slovakia, social work was founded and developed in pedagogical spaces [

1]. In the case of Scotland, the idea is put forward that pedagogy and social education are established as a theoretical basis for grounding social work practices, which aim to promote social welfare through socio-educational strategies [

6]. In Latin America, social pedagogy is closely related to popular education [

5]. Finally, in the case of Spain, according to its historical context, social pedagogy has developed around adult education, specialized education and sociocultural animation [

2] albeit in contexts outside formal education, either in the field of community intervention or as one-off activities in schools.

Just as in each country there is a different tradition to speak of social pedagogy, the professional figure obtains different names depending on the country to which reference is made. Adopting a general perspective, the social pedagogue: is a social education professional who promotes prosocial ethical behavior; carries out socio-pedagogical assessment and social diagnosis within the user’s environment and the relationships established therein; works to provide specialized and individualized care and advice to prevent risk factors and reeducate behavior; and works with the community [

7].

As we have just seen, the great differences in relation to the social needs of each country and its social tradition have contributed to the wide heterogeneity in the conceptualization of social intervention. Although this could favor the richness in the diversity of social intervention itself, this lack of unity in its conceptualization and determination leads to the indeterminate use of the terms social education, social pedagogy and even social work to refer to such socio-educational actions [

2]. In order to not generate ambiguity, henceforth the term social education will be used in this study.

In contrast to what has been said about the conception and terminology of social education, there is greater consensus in the literature regarding the functions attributed to social education. The scope of action of the social educator in English-speaking countries, although not limited to this, is mainly focused on the care of children and young people, and more specifically in schools, where he/she: develops educational, socio-educational, preventive and re-education activities; offers support, intervention, protection, counseling and mediation activities; provides analytical, social valuation, diagnostic and evaluation tasks; and coordinates activities [

7,

8,

9]. It also intervenes in other problems associated with children and young people, such as drug dependence, media influence, good use of free time and attention to emerging social problems [

7].

In addition to these functions specific to the educational context, in other countries the work of the social educator is open to other areas, covering functions specific to these contexts. These areas of intervention pay attention to: family and community development; the elderly; training and job placement; education for health; the environment and consumption; disability and diversity; sociocultural animation and management; leisure and free time activities; and mediation and social integration tasks [

10].

So far, we have presented the theoretical and conceptual context that the literature proposes for social education, but what is society’s perception of social education? As it is a relatively new area of knowledge and in a continuous process of construction [

11], we do not know how well it is understood in society. To answer this question, it is necessary to analyze the research that has tried to shed light on society’s perception of the work of social educators. A review of the literature shows that not many studies have attempted to answer this question.

First, we find the study developed by [

12]. This study aimed to define the profile of the social educator based on the perceptions extracted from students of Social Work and Sociology. To this end, they applied a qualitative methodology through the conduct of a semi-structured interview, which had 4 open-ended questions. In light of the information obtained in this study, the authors interpret that social education is still not well defined. The main sources associated with this misinformation were the newness of the profession, and with it the lack of knowledge of its methodology, as well as the lack of confidence about the impact of its actions. These results showed the gap that exists between the social perception of the social educator and his or her real attributed functions. Something similar was found in [

13] when interviewing nine social pedagogical researchers from Northern Europe.

Along the same lines as the previous study, we find the study developed by [

14]. The aim of this study was to determine the perception of secondary school students about the figure of the school social educator. To this end, a questionnaire survey was carried out. The results obtained pointed to the idea of the importance of having knowledge and experience with the figure of the social educator, since those students who stated that they had previous experience with the profession showed a clear and positive stance on the importance of the work of the social educator. These results are in line with those found with university students in Romania [

15].

In [

16], they attempted to define the competency profile of the social education professional through a mixed design, using a triangulation design and working with four moments supported by a discussion group (SWOT matrix, quantitative questionnaire, discussion, CAME matrix). The results obtained allowed them to propose that it is the social educators themselves who find as a weakness the lack of knowledge of their own functions and competencies, not in a general way, but the delimitation of these functions and competencies with those of other professionals. Hence the importance of redefining the competency profile of the social educator.

Finally, and as the main antecedent to this study, we find the work done by [

17]. This study set out to answer the question ‘what is the public understanding of social education today?’. The authors intended to know the degree of social knowledge about social education, the professional profile of the social educator and the professional fields of the social educator, and to know the relationship between society and social education. By means of a questionnaire they evaluated the level of knowledge regarding the definition, functions and areas of work of the social educator in a sample of inhabitants of a large city (Barcelona). Based on the results obtained, the authors conclude that the public understanding of social education in the target population, in terms of knowledge of the definition of social education, functions and areas of work of the professional, is insufficient and ambiguous. This lack of knowledge can be seen with more presence in the “Definition of Social Education”, independently of the sociodemographic variables, only having had previous direct or indirect contact with social education had a significant effect. These results show the importance of dissemination tasks, experience and knowledge of social education, emphasizing its definition and the functions developed by social educators, as this has a positive impact on the perception of citizenship.

As we have been able to see through the background, there are few studies developed that have tried to analyze society’s perception of the professional figure of the social educator. The data point to the fact that society in general has a somewhat diffuse perception of the work of the social educator [

12,

13,

14,

15,

16]. That is why this study aims to evaluate, through a mixed design study, the perception that a part of society has about the professional figure of the social educator. On the one hand, we will evaluate the perception held about different professional aspects of the social educator using a previously used scale [

17]. As we have previously described in this study, the perception of the urban population was evaluated, so in our work we will analyze the perception held by the population of rural areas. Previous studies have suggested that there may be some labor discrepancy between the urban and rural work environments [

18,

19], so in this study we set out to analyze the perception in the rural population. This will allow us to compare whether the results obtained in the rural population resemble the results found in the urban population [

17]. Additionally, we proposed to analyze whether the evaluated job perception could vary according to sociodemographic factors (such as age, gender, etc.), or with factors closer to the objective of the study (such as having had previous experience with a social educator or thinking about having knowledge about this professional figure).

Finally, we sequentially triangulated different research techniques incorporating the qualitative approach to provide a wider field of analysis [

20]. The mixed methodological design used the semi-structured guided interview as an instrument with the aim of investigating the perception that social education professionals themselves have of the social image of their profession in rural settings. The aim was also to obtain explanations that would provide answers to the findings of the previous study.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

The study was carried out with a sample of 222 participants from a rural area in the south of Spain (Andalusia) called “el Valle de los Pedroches” in Cordoba. The mean age of the participants was M = 35.45 (SD = 14.65) where 69.8% (N = 155) of the total participants were female and 30.2% (N = 67) were male. Regarding the employment status of the participants, 46.4% were employed, 34.2% were students, 10.4% were working and studying at the same time, 8.1% were unemployed and looking for a job, and 0.9% were pensioners. Regarding the level of education, 45.7% had higher education, 40.3% had secondary education, 7.2% had basic education, 5.9% had postgraduate studies and 0.9% had no education.

In the qualitative interview study, the sample of key informants was purposive. The selection criteria were: (1) to be a social educator; (2) to practice the profession in rural environments. The age of the interviewees was between 30 and 45 years, all three being women due to the high feminization of the profession [

21]. Regarding the level of education, 100% had higher education. The cases included are the result of a dynamic and flexible contact process and respond to the interest in obtaining explanations to the findings obtained from the perspective of the subjects. To guarantee the anonymity of the participants, they are assigned an alphanumeric code that does not allow their identification.

2.2. Instruments

A questionnaire was used as a data collection instrument, which was configured in two blocks. The first block was designed to obtain sociodemographic information on the sample, as well as our proposed grouping variables (occupation; field of work; level of education; precognition of the social educator; previous experience with a social educator). In the second block of the questionnaire we use an adaptation of the scale used by [

17] to assess the level of knowledge about the profile of the social educator.

This scale consisted of 15 items which were grouped into three factors designed to measure different aspects related to the social educator’s profile: (a) knowledge related to the professional definition of the social educator (PRD); (b) knowledge related to the social educator’s functions (FUN); and (c) knowledge related to the social educator’s fields of action (ARE). See

Table 1 to see which items load on which factor (Items 4, 5, 7, 9, 11, 12, and 13 were inverse items for their factor). All items were answered on a Likert-type scale of 5, which measured the degree of agreement or disagreement that the participants expressed on the statements proposed in the items, where 1 represented “Strongly disagree” and 5 represented “Strongly agree”. The original work showed no measures of reliability or validity of the scale.

In addition, three semi-structured guided interviews were conducted with different social education professionals. The interviews consisted of 7 open-ended questions (see

Appendix A). These questions were designed prior to the interview, and were aimed at finding out about the functions performed in the professional practice, as well as their opinion on the perception that society has of their professional work.

2.3. Procedure

In the study we present here, we can distinguish two phases. In the first phase we carried out a quantitative evaluation using a self-report scale. The second phase was devoted to a qualitative evaluation in which interviews were conducted with social education professionals.

In the first phase we implemented the measurement scale through the digital tool Google Form. This allowed us to provide access to the questionnaire through digital media. Participation in the study was completely voluntary, in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki [

22]. In addition, prior to carrying out the research, the approval of the Human Research Ethics Committee of the University of Jaén was requested and granted (DIC.18/8.PRY). When accessing the digital questionnaire, the first screen served as an informed consent form. The following information was displayed:

“The objective of this study is to know the perception of the figure of the social educator in a rural population. The questionnaire consists of 2 parts: the first part contains general questions and the second part consists of 15 items which you will have to answer according to your degree of agreement or disagreement about the statements shown. There are no right or wrong answers, but all are valid.

Participation in the study is voluntary, so you can leave the study at any time once you have started it. The questionnaire is completely anonymous and the data collected here will be treated exclusively for research purposes. If you wish to know in more detail the ethical codes that govern our work as researchers, you can consult the ethical guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki. (WMA, 2009).

https://acortar.link/Px7fuL (Date of access: 2 April 2022).

If you would like to obtain more information about the study and its results, please do not hesitate to contact us through this e-mail address sparra@ujaen.es”.

At the end of the text there was a check box with the following sentence “I have read and understood the conditions of the study and I wish to participate in it voluntarily”. To access the questionnaire, the participant had to click this box to start the questionnaire.

In the second phase of the study, semi-structured interviews were conducted in person with key informants. The interviews followed a semi-structured script with 7 open-ended questions, which were recorded and fully transcribed.

2.4. Data Analysis

The analytical treatment of the quantitative information consisted of two phases. All the analyses in this phase were carried out with the free software jamovi [

23] and with R software version 4.1.2 [

24].

In the first phase we analyzed the psychometric characteristics of the scale used. As reported, this scale has been used previously, but its internal structure is unknown, as well as its psychometric behavior. For this phase we will start by data screening the data obtained with the scale in order to analyze the assumptions for the factorial treatment, as well as its distribution. The variables showed no problems related to additivity, nor multicollinearity (r > 0.90), nor singularity (r > 0.95). The residuals resulting from a regression between our data and a random dataset showed a distribution between −2 and +2 suggesting no infliction of linearity, homogeneity and homoscedasticity assumptions.

We analyzed the multivariate normality of the data using Mardia’s multivariate normality test. The results showed that our data did not have a multivariate normal distribution, Z

Kurtosis = 9.12,

p < 0.01. We conducted a Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) to analyze the internal structure of the originally proposed scale, as well as its validity and reliability. Due to the lack of multivariate normality, a robust variant of Weighted Least Squares (WLSM) was used as the estimation method in the factor treatment [

25].

In the second quantitative analytical phase, we set out to analyze to what extent our grouping variables (socio-demographic: gender, age, occupation, and level of education; and related to the social educator: thinking about knowing the figure of the social educator, and having had experience with him/her) could modulate the results of the factors obtained through the scale. To do this, we carried out two MANOVAs in which we took the three factors obtained from the scale (PRD, FUN and ARE) as dependent variables and the results of the above-mentioned questions as grouping variables. The first MANOVA analyzed the socio-demographic variables (gender, age, occupation and level of education) and the second MANOVA analyzed variables related to the social educator (thinking about knowing the figure of the social educator, and having had experience with the figure of the social educator).

In order to compare the perception of the social educator obtained in this study in a rural population, and that obtained in an urban population [

17], we carried out a meta-analytical comparison between the scores of both studies. To do so, we first calculated the difference between the scores for each of the three factors measured by the scale in each of the studies. Thus, positive effect sizes will denote a superior perception in the rural population versus the perception in the urban population, and negative effect sizes will show superiority in the perceptions in the urban population.

The effect of this difference (g) was computed using Equations (4.18) and (4.19) from [

26], including the correction factor J computed with Equations (4.22) and (4.23). The variance was computed using Equations (4.20) and (4.24) from the same source. These analyses were performed using the

metafor package for R [

27] using random-effects models.

In order to analyze the qualitative information obtained through the interviews, the data were systematized and segmented by differentiating between descriptive and interpretative content. The analysis of the interpretative information is carried out under the basic principles of discursive analysis and in three phases: pre-analysis, coding and categorization. [

28].

Discursive positions and interpretations, common and divergent narrative configurations, intentions and social conventions [

29] were sought. In the process of textual analysis, the software Atlas.ti- version 9 was used for the coding, categorization and systematization of the groundedness (E) and density (D) of the data and the identification of conceptual networks. From the qualitative perspective, we analyzed both the absence of said codes in the discourses and the deep meanings and definition of the situation from the point of view of the participants. We have also elaborated semantic networks that graphically show the interrelationships between the categories and codes of analysis for the construction of the discourse.

3. Results

Table 1 shows the descriptive results for the items and factors assessed with the scale used.

Table 1.

Descriptive from scale.

Table 1.

Descriptive from scale.

Factor

Indicator | N | Mean | Median | SD | Min | Max | Skewness (SE) | Kurtosis (SE) |

|---|

| PRD | 222 | 4.24 | 4.50 | 0.81 | 1.50 | 5 | −0.96(0.16) | 0.40(0.33) |

| v1 | 222 | 4.47 | 5.00 | 0.85 | 1 | 5 | −1.69(0.16) | 2.58(0.33) |

| v2 | 222 | 4.01 | 4.00 | 1.09 | 1 | 5 | −0.85(0.16) | −0.20(0.33) |

| FUN | 222 | 4.03 | 4.17 | 0.46 | 2.83 | 5 | −0.48(0.16) | −0.10(0.33) |

| v3 | 222 | 4.08 | 4.50 | 1.14 | 1 | 5 | −1.11(0.16) | 0.40(0.33) |

| v6 | 222 | 4.50 | 5.00 | 0.78 | 1 | 5 | −1.88(0.16) | 4.47(0.33) |

| v8 | 222 | 4.61 | 5.00 | 0.70 | 2 | 5 | −1.66(0.16) | 1.77(0.33) |

| v10 | 222 | 4.42 | 5.00 | 0.77 | 1 | 5 | −1.31(0.16) | 1.58(0.33) |

| v12 | 222 | 3.65 | 4.00 | 1.22 | 1 | 5 | −0.51(0.16) | −0.70(0.33) |

| v14 | 222 | 4.21 | 5.00 | 1.04 | 1 | 5 | −1.28(0.16) | 1.04(0.33) |

| ARE | 222 | 3.61 | 3.67 | 0.69 | 1.67 | 5 | −0.63(0.16) | 0.25(0.33) |

| v4 | 222 | 2.22 | 2.00 | 1.30 | 1 | 5 | 0.76(0.16) | −0.56(0.33) |

| v5 | 222 | 2.74 | 3.00 | 1.25 | 1 | 5 | 0.16(0.16) | −0.94(0.33) |

| v7 | 222 | 2.12 | 1.00 | 1.43 | 1 | 5 | 0.96(0.16) | −0.50(0.33) |

| v9 | 222 | 2.32 | 2.00 | 1.39 | 1 | 5 | 0.74(0.16) | −0.68(0.33) |

| v11 | 222 | 2.17 | 2.00 | 1.11 | 1 | 5 | 0.52(0.16) | −0.55(0.33) |

| v13 | 222 | 2.16 | 2.00 | 1.25 | 1 | 5 | 0.77(0.16) | −0.50(0.33) |

| v15 | 222 | 3.23 | 3.00 | 1.35 | 1 | 5 | −0.25(0.16) | −1.01(0.33) |

In order to analyze both the internal structure of the scale used and the psychometric properties, a Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) was performed. The factor analysis showed that item 11 was not shown to explain significant variance in any of the factors, so it was excluded from the final analysis.

The results of the final model showed an excellent fit [

30], χ

2 (72) = 92.57,

p = 0.052, con CFI = 0.950, TLI = 0.937, SRMR = 0.063, RMSEA = 0.036 (RMSEA 90% CI [0.000, 0.056]), and with acceptable levels of reliability α = 0.72 y ω = 0.73.

Table 2 presents in more detail the results of the behavior of the observed and latent variables of the scale.

Once the psychometric properties of our scale had been analyzed, we set out to analyze the extent to which our grouping variables could influence the perception of the different factors assessed by our scale (PDR, FUN, ARE). Due to the characteristics of the grouping variables, we separated the analysis into two MANOVAS, the first analyzing socio-demographic variables (with age as a covariate) and the second analyzing variables related to the role of the social educator.

Table 3 presents the results of the MANOVA for the sociodemographic variables.

As can be seen, the model showed a significant multivariate effect for the occupation variable, F(12, 506) = 2.406,

p = 0.005, y education level, F(12, 506) = 2.406,

p = 0.004, no other factor or interaction was significant. Univariate analysis showed that: gender modulated the perception of FUN; occupation modulated the perception of PRD and ARE; educational level modulated the perception of FUN and ARE; and only the interaction of gender and occupation modulated the perception of ARE (see

Table 3 for details).

Table 4 presents the results of the MANOVA for the variables associated with the figure of the social educator. As can be seen, we found a multivariate effect of the variable knowledge, F(3, 215) = 3.411,

p = 0.018 and of the variable experience, F(3, 215) = 3.455,

p = 0.017, but not interaction. If we look at the unchanged effects, we can see that both knowledge and experience modulated the perception of FUN and ARE, showing no interaction effect.

Finally, we set out to inferentially compare the scores we obtained on the perception of the social educator in rural settings in this study with those obtained with the urban population [

17].

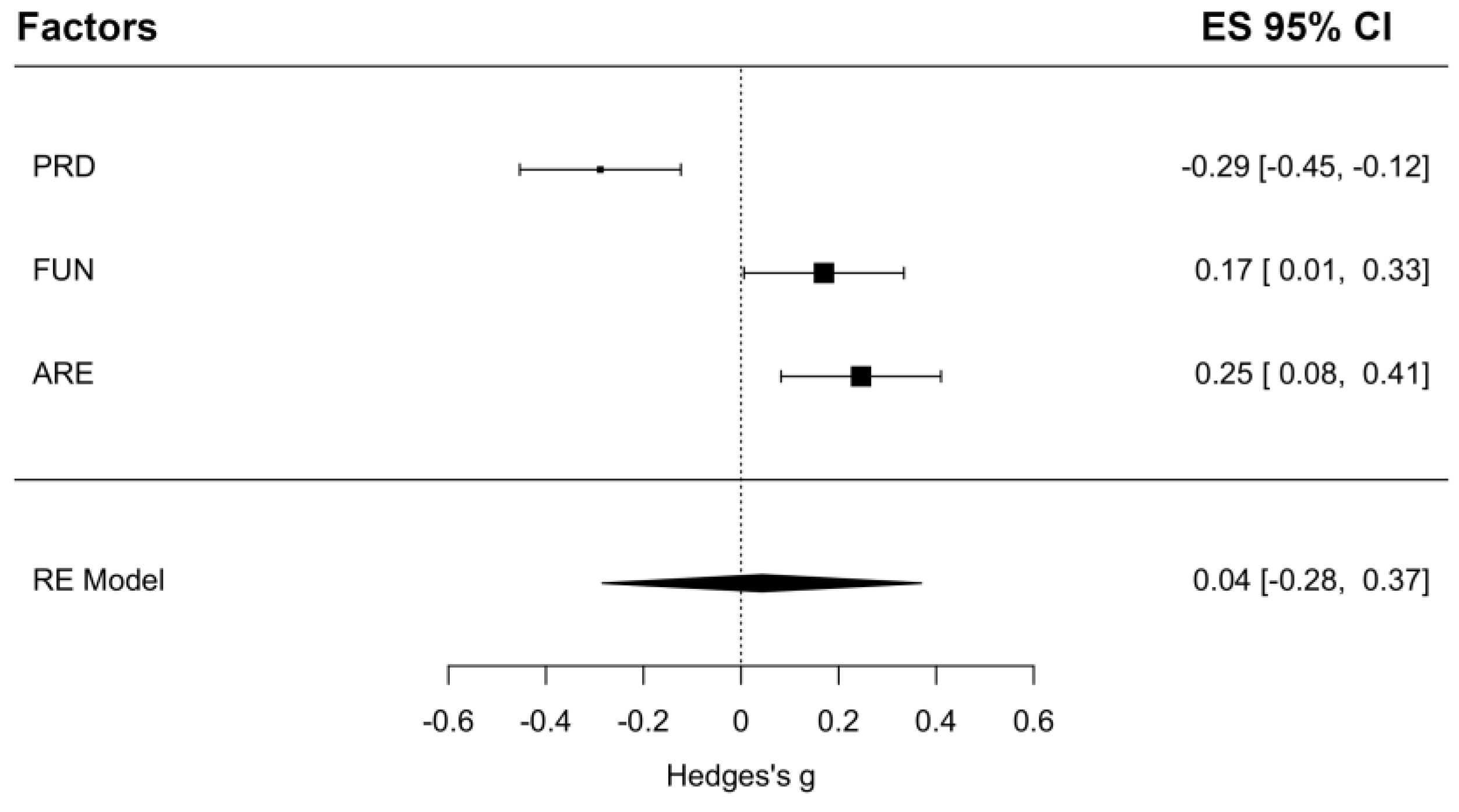

Figure 1 shows the effect sizes resulting from the comparison of the scores on the variables obtained through the scale (PDR, FUN and ARE) in the urban and rural populations. It should be remembered that positive effect sizes will indicate a difference in perception in favor of the rural population and negative effect sizes will indicate a perception in favor of the urban population. The result of this comparison showed a very small average effect, g = 0.043, 95%CI [−0.284, 0.370], not significant, z = 0.225,

p = 0.798. This result indicates that, overall, the two populations did not show significant differences in perception. However, if we look more closely at the comparisons for each type of perception, significant differences emerge. While the perception of the definition of the social educator is higher in urban settings (g = −0.29), perceptions of the social educator’s role and domains are higher in the rural setting (g = 0.17 and g = 0.25, respectively).

Additionally, we set out to test whether having had experience with a social educator or not showed differential effects between urban and rural populations. We therefore calculated the differences between the perceptions of the different factors for those who had had experience with the social educator and those who had not, and used the type of population (urban vs. rural) as a moderating factor in the analysis.

Figure 2 represents the result of this analysis. The first three effects represent the difference in the three factors for the urban population, and the next three represent the difference for the rural population. The average effect size for each level of the moderator variable (rural vs. urban population) is represented by the shaded diamond shapes under each factor. The moderation analysis showed a very small effect g = 0.088, 95%CI [−0.275, 0.451], not significant z = 0.476,

p = 0.634. These results indicated that having had experience with the social educator did not show a differential effect between the different populations (urban vs. rural).

Regarding the results of the qualitative analysis,

Figure 3 reflects the main narrative discourses collected in the interviews with social education professionals. The categories with the highest groundedness are: (1) unknown profession (linked with the variable PDR), with a groundedness (E) of 12 quotes and density (D) of nine links with other categories and/or codes; (2) lack of definition of social educator’s functions (linked with variable FUN) with (E = 7); (D = 6); (3) multiple fields of intervention (E = 3); (D = 6) (linked with variable ARE); and (4) lack of institutional support (emergent category) (E = 4); (D = 6).

These informants agree that the figure of the social educator is currently an “unknown profession” in general terms (E = 7), with this lack of knowledge being more accentuated in rural areas (E = 3). This perception is associated with the fact that it is a new career, or as the informants call it a ‘young profession’ (E = 4), but also with what is considered a ‘lack of institutional support’ (E = 6) with serious consequences for professional development in two ways: (1) lack of definition of the functions of the social educator (E = 6), which is associated with ‘lack of professional roots’ to the detriment of other intervention professions with which they are confused, such as social work; ‘professional intrusion’ (E = 10) and ‘lack of social recognition’ of the profession (E = 5). (2) Institutional neglect in rural areas evidenced by allocating ‘fewer resources’ (E = 3) than in urban areas, which aggravates the situation of the profession in rural areas. It is concluded the ‘need of professional vindication’ (E = 5) and the consolidation and recognition of specific techniques of intervention of social education.

4. Discussion

Social education is a relatively young area of knowledge and this may generate a certain lack of knowledge in society about what it is and the functions associated with this area of knowledge [

12,

13,

14,

15,

16]. This novelty, in this case, is associated with a theoretical and unified insufficiency [

4,

5], which sometimes leads to ambiguity in the delimitation and/or confusion with other professions, such as social work [

1,

2]. For this reason, the objective of this research was to analyze the perspective that part of society has on social education and the labor figure that represents it, the social educator. Using a mixed design study, we proposed to analyze the social perception of the figure of the social educator through a questionnaire on a sample of participants belonging to a rural population, then, by means of interviews with a representative sample of key informants, we set out to find out what perception of their work is held by social education professionals working in rural environments.

The results obtained when analyzing the perception that the inhabitants of a rural area held about the different aspects of the work of a social educator did not show a great deviation from their theoretical conceptualization. The scores obtained through the perceptions showed ranges above the mean of the scale, i.e., the evaluated participants, in general, agreed with the statements about the functions, areas of intervention or conceptualization of social education.

In this study, we used a questionnaire previously used to measure the social perception of the figure of the social educator in an urban population. In the original study [

17] the authors did not analyze the psychometric properties of the scale used, and for this reason, not knowing the reliability and validity of the scale, the results could have been compromised. In this study, before making interpretations of the scores obtained on the perception of the participants, we analyzed whether the scale met the psychometric standards of reliability and validity.

In addition, we proposed to analyze whether the perception of the different factors related to the work of the social educator evaluated by means of the scale could be modulated according to sociodemographic variables, or variables associated with factors resulting from the relationship with the figure of the social educator. Through these results we were able to verify that both the occupational status and the level of education of the participants influenced their perception of the social educator. More interestingly, it also allowed us to know that those participants who had previous experience with a social educator, or thought they knew the figure of the social educator, showed perception closer to the theoretical approach. Similarly to what is pointed out in [

17], our results suggest that having contact with the figure of the social educator is associated with the knowledge that one believes to have of social education and, in turn, with an accurate perception of the functions, conceptions and areas of action of the social educator.

The lack of institutional support that entails the insufficiency of professional referents for the knowledge of the profession [

14,

15] accentuates the perception of lack of knowledge of the profession in rural versus urban areas [

18,

19]. For this reason, in our work we set out to analyze this knowledge on a rural population, and thus be able to compare the results with those found in an urban population in [

17]. Although the results found in a rural population seem to be along the same lines as those found in an urban population [

17], a more rigorous comparison shows us certain notable differences to be highlighted.

First, if we compare the scores of each of the three factors analyzed on the perception of the social educator, while the perception of the conceptual definition seems to be significantly higher in the urban population, the perception of the functions and areas of action are significantly higher in the urban population. These differences are diluted when unifying the three perceptions into a total score. However, something to be highlighted in a positive way is that the improvement effect on perceptions observed as a consequence of having had experience with the figure of the social educator occurred without notable differences in both rural and urban environments.

With regard to the search for explanations for these facts, the narrative discourses of the key informants interviewed coincide with previous studies [

14,

15] in pointing out a causal link between the three factors analyzed and a ‘lack of institutional support’. In this sense, it is argued that the lack of knowledge of the conceptual definition, functions and fields of action of the social educator are evidence of a lack of consolidation and references for this professional profile, due to the fact that public administrations are not supporting the implementation of the figure of the social educator. In this sense, the insufficient number of jobs and job offers with this professional profile in public psychosocial care centers is denounced. This ‘institutional negligence’ is perceived to be more accentuated in rural areas, which, coinciding with the contributions of [

18,

19], further increases the lack of knowledge of social education in rural areas. Accordingly, we agree with [

10] on the need to incorporate social educators in centers at all educational levels, especially in primary schools, as well as in social services centers and health care centers.

As a result, and in line with previous studies [

21,

31], social educators are perceived as invisible and receive little professional and social recognition. This highlights the importance of giving greater visibility and dissemination to the action and impact that the work of social educators can have on society.

In terms of professional functions, for greater recognition of the profession and its work functions, the social educators interviewees bring an informed and nuanced understanding of their professional roles and knowledge of these roles among the rural population. In this sense, they advocate the unification and clarification of competencies, contradicting the principles defended in the literature that define the social educator as a polyvalent professional [

31,

32,

33]. We consider that, although the objectives of social education require this functional polyvalence, the lack of precision in the definition of competency attributions means that other professional disciplines, such as social work, are more deeply rooted in the areas of socio-educational intervention and enjoy greater professional and social recognition.

Limitations and Prospects

Our study is not free of limitations. In the first place, given that the target population of our study is inhabitants of a rural environment, this means that the sample is not as large as in the study where there are no limitations. Nevertheless, the sample size of our study does not differ so much from the study conducted with the population of large cities.

Another limitation of the study is associated with the scale used. This scale was created by [

17] and by using it we have inherited some problems that this scale brings with it. Some items are not fully discriminative for the factor measured, and the inverse items are grouped around a single factor. These factors mean that the psychometric properties of the scale have room for improvement. Future research related to this topic should propose a better designed scale, with items that facilitate discrimination and, if the inverse items are maintained, they should be distributed among the factors. Related to this is that in our study we can only compare the modulating effect of one of the factors (having had experience with the social educator) but not with the rest. These data are not provided in [

17], so it was not possible to compare them. Perhaps future research could try to provide more data on the differential effect between these populations.

Regarding the qualitative aspect of our study. The number of interviews conducted was not very high. In future research it would be interesting to continue the qualitative study with a larger sample of social educators from different fields of intervention in order to collect a discursive narrative referring to the specific situation of each of these fields of professional development. It would be convenient to use more interactive techniques such as focus groups, which would facilitate the emergence of categories of analysis, as well as the narrative construction of consensus and disagreement around the topics of interest.