Abstract

This study seeks to analyse which factors in the work environments of students undergoing virtual in-service ICT teacher training facilitate the initial transfer of learning. Deductive categories were first defined based on previous studies. A qualitative analysis was then conducted to triangulate three data sources—two reflective training activities and interviews with students—using NVivo 12 software. This enabled us to determine how important some of these factors are for learning transfer within the context of techno-pedagogical distance teacher training, such as the predominance of social support over organizational categories.

1. Introduction

Pisanu et al. [1] emphasized that workplace organizational factors can have a positive influence on the learning transfer process in the context of in-service teacher training, promoting long-term effectiveness even after the end of the training. These factors, combined with the course design and the personal characteristics of the teachers, are facilitators of this process, and have a particular impact when teachers return to the workplace—a period when situations or factors that hinder the actual transfer of learning are common.

Research on which organizational variables have an impact on teacher training also, therefore, provides institutions with information about what organizational changes are necessary to foster learning transfer and to sustain the changes brought about in teachers through training [2]. All of this is even more important when we know little about the impact of work environment factors on the learning transfer process in online in-service training of ICT skills for teachers.

Following our theoretical framework on the transfer of learning presented below, we use the term teacher training to refer to our context of the in-service teacher. We understand training as a capacity that offers the acquisition of competencies, skills, and knowledge for the teaching function, that enables the reflection of practice, and that orients the predisposition to change, collaborating with new values to teaching.

2. Theoretical Framework

Work Environment Factors and Learning Transfer

The concept of transfer, according to the study by Baldwin & Ford [3], can be determined as the degree to which students successfully and continuously apply the knowledge, skills, and attitudes acquired from a training course [2,4,5,6,7]. In other words, the study of transfer means finding evidence of the new skills and knowledge acquired in teacher training being applied in an adapted and flexible way to the situations faced in work environments [7].

The learning transfer process, when individual learning passes from training to concrete application in a work context [2], is influenced by conditioning elements related to course design, the students’ personal characteristics and the work environment.

This process is strongly related to this third factor, the work environment and its elements [3,5,6,8], which can facilitate or hinder said process [9].

Research on learning transfer and variables in the work environment has largely focused on personal development in organizations in the business and corporate spheres [8,10,11,12]. In recent years, however, important research has been done in the field of teacher training [1,5,6,9,13]. In both contexts, the organizational factors that affect learning transfer are related to the support that trainees (or those who have just been trained) receive in applying their new skills [14], through the work system and human resource organizational processes [10,11].

Satisfactory support from an organization involves correctly establishing measures such as having time to implement and consolidate changes, the availability of resources, and assessing the importance of the changes to the institution. These are all elements that contribute to eliminating or neutralizing possible obstacles to learning transfer [5,8,10,15].

Predisposition to change refers to an organization’s culture, beliefs and values regarding openness or resistance to innovation and continuous learning. It also includes the organization’s willingness to invest in change and to provide workers in training with the necessary spaces, as well as the autonomy, to apply new learning [6,10,16].

Support from supervisors [3,4,5,6,7,9,10,11,12] comes in the form of guidance and discussion of new knowledge at work. This supervision helps identify how to use what has been learned, supports the trainee with time and in overcoming difficulties with implementing changes, and provides feedback after implementation. Based on their empirical study, Pham et al. [17] stated that when trainees perceive that they are being supported by their supervisors they believe that the training will be useful, that it will help them perform their work effectively and that they will be rewarded for it. In practice, for Testers et al. [16], the support of supervisors can come from creating an innovative and open organizational environment; peer support is more related to the concrete application of learning, via assistance, encouragement and feedback.

Many authors point to peer support as being important in the context of learning transfer [4,5,7,8,9,10,12,13,18]. Also known as teaching culture [6,9], this support involves peers acknowledging each other, promoting and supporting the use of new knowledge and providing constructive feedback, which in turn strengthens learning transfer [4,19]. Lim and Nowell [18] noted that setting up institutionalized peer networks and ideas exchanges also strengthens learning transfer.

However, from research conducted specifically on online training [16,20], it seems that peer support may be affected by the particular conditions of e-learning. Specific investment by organizations in peer support for online teacher training is beneficial, providing communication resources so that peers can support each other and continue sharing experiences during and after training [21]. Here we would also highlight technologies that can be used for the creation of spaces that allow teachers to share their knowledge and experiences, and to work and reflect collaboratively.

Opportunities for the direct application of new learning in the work context are also a determining factor in the successful transfer of learning from training [4,5,7,8,9,10,11,12,13]. Organizations should provide the opportunities, time and flexibility for the immediate application of what students have learned.

Finally, barriers or facilitators to learning transfer in the work environment may also be related to the material or financial resources and the access to technologies available, as well as the physical condition of the teaching environment [6,9,20].

All of this can be substantiated via a specific look at research on learning transfer in teacher training. First, empirical research in this area of training highlights the factor of institutional recognition, when participants expect the institution to recognize and value the effort they make in transferring what they have learned to their work, even to the extent of being rewarded for it [5,6,9]. Recognition is related to personal satisfaction, productivity at work and perceived respect; and it can take the form of an increased salary or other types of rewards and promotions that end up having a positive impact on learning transfer [19].

Feedback has not received a lot of attention in research on learning transfer [6,9,10,16]. However, as it is an important element in instructional design in education, feedback, and comments about teaching after the application of new knowledge, will be considered a relevant factor of analysis for this research.

As we have observed, the factors related to learning transfer in a general context are already well known. However, there is a lack of in-depth research into labour variables in the field of distance in-service teacher training. It is also important to stress that if it is confirmed that learning transfer from online training is better when institutions support the process, new perspectives would open up for this form of training.

Based on the description of the factors above, it is clear that appropriate institutional support for the transfer of learning from training needs to be implemented in the workplace, which is often straightforward, and would be accompanied by new work and socialization dynamics. All of this would facilitate the process and allow the implementation and maintenance of the necessary changes, which would in turn result in improvements for the institution.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Paradigm, Aims and Questions

The aim of this research was to contribute understanding and information about the influence of work environment factors on learning transfer in the online in-service training of ICT skills.

Taking this into account, and based on the results of previous research into the dimensions of course design and the personal characteristics of participants (Author, 2021a, 2021b), the guiding question we proposed to answer was: What characteristics of the work environment facilitate a greater initial transfer of learning?

3.2. Characteristics of the Context and the Sample

The context of our research is ongoing online teacher training in the Master in Education course offered by the Universidad Europea del Atlántico. This training consists of a Master’s degree in Education, which lasts two years and comprises a common block of subjects for teacher training and specialization in digital skills.

At the time of data collection, potential participants should have already completed the subjects of the Master’s specialization and developed the two reflective training activities (the Starting Point and the Portfolio on the subjects of the specialization), used as a source of data (which are detailed in the methods and data sources section below), as well as still have six months before the end of the course to conduct the interview.

The subjects of this research were ten students who accepted the invitation to participate consciously and voluntarily, through a consent form.

Of the ten subjects studied, nine were female and one male. The average age of the participants was 42, with an average of 13 years working as a teacher. The participants’ six countries of origin were Argentina, Colombia, El Salvador, Honduras, Mexico, and Nicaragua. The master’s degree is offered by a Spanish faculty of education; however, students came from all over Latin America.

Half of the teachers had qualifications in the field of education, with degrees in English and mathematics. The rest were either qualified in the field of health, with degrees in subjects such as psychology and medicine, or computer systems engineering. Half of the participants worked as university professors (due to the context of their countries which do not require prior higher education training) and also in online teaching, while the rest worked in primary education or ongoing teacher training.

3.3. Methods and Data Sources

Based on studies that ask participants to give accounts of their experience of applying new knowledge and/or newly acquired skills [14,22], as a source of data we used two training activities from the course itself, carried out at different times, one at the beginning and the other in the final stage, which we subjected to a qualitative analysis.

In the first data source, a document we have called Starting Point, which takes place in the first weeks of the course, students recalled training and professional experiences they had undergone before starting the Master’s degree, as well as their needs and expectations concerning training.

In the Portfolio, the second data source, students described what they considered to be the most significant and representative examples of what they learnt during the training specialization, as well as critically analysing how this knowledge and these skills had an impact on their training process. Returning to the reflections elaborated at the beginning of the course in the Starting Point, as well as critically analysing how this knowledge and these skills were having an impact on their training process and their teaching practice.

An online interview conducted individually with the research participants was also used, for questioning the subjects’ points of view and helping them with their perception of the situations in which they act [23]. The guide was designed with questions related to the working environment, as well as addressing questions focused on personal aspects and the design of the course. The transcribed interviews were analysed qualitatively using the NVivo program.

3.4. Data Analysis and Codebook

The analysis procedure was based on qualitative content analysis [24], which allowed us to subjectively interpret the content of the textual data through the systemic classification process of coding and identifying themes or patterns.

Content analysis [24,25] was employed to identify various predetermined deductive categories from previous studies, and Table 1 below was compiled to show the work environment categories, the corresponding areas of research and the analysis codes arrived at using NVivo software.

Table 1.

Work environment factors classified by area and codes.

Data validation was carried out via methodological triangulation; in other words, by contrasting the different data sources [26]. In this case, the two training activities of the Master’s course, at the beginning and the end of the course, and the interview conducted three months after the second activity. Thus, it was possible to identify those subjects who provided concrete and detailed reports of some experience of applying the learning acquired in the course to their pedagogical practice during the elaboration of the Portfolio or in the interview.

4. Results

From the analysis of the Starting Point document and the interviews, we detected that half of the participants worked in university teaching and online teaching, and the other half in primary education or in-service teacher training. Most of the latter worked in the state sector.

The group who successfully transferred their learning had worked for an average of 13.5 years in the same institution; those who were less successful had an average of 2.6 years.

4.1. Support from Supervisors

Most of the participants who successfully transferred their learning said that they had received some support from their supervisors, who were understood to be those responsible for advising, supervising, organizing and administering the function of teachers in their work environment. In the case of direct support, the only student whose institution financed their course clearly said that their supervisors accompanied them during the training—an example of good practice:

“I think that maybe every 3 months they asked me what I was working on, because they’re very attentive to that, but I like it because I feel that it motivates you more because they show interest in what you’re doing, so I feel important in the institution, I feel that I’m a very important element for them, they’re very focused on that and they’re trying to help me improve what I’m working on.”(Interview—Participant E)

During the compilation of the Portfolio, one participant also said that they looked to their supervisors to help them implement what they had learned, showing an openness to dialogue with supervisors about changes in the way they do things:

“At the end of the training I felt very satisfied and wanted to share the information and the site we had created with my colleagues. After sharing it with my immediate boss, I asked her to authorize me to share the site with the next group of teachers, who were doing face-to-face training, which she agreed to.”(Portfolio—Participant F)

At other times this support was not direct, in the form of supervision, but indirect (the supervisor was aware of the situation and offered additional time for changes if necessary):

“Yes, from all of my family, from my co-workers too, but directly from the institution, no; what I mean is, if I’d wanted to take leave to work on my thesis, for example, I could have requested it.”(Interview—Participant D)

In contrast, a lack of support from supervisors and a relationship of trust with them was observed among those participants who were not successful in transferring their learning. This was explicit in many cases:

“Since it’s a new job, you need to really know how the place works. Also, maybe on a personal level, I need approval before launching something, to know if I’m doing things right; it’s like I need that early feedback before daring to totally offer up a project.”(Interview—Participant J)

“No, we do everything on our own. On the contrary, sometimes for a Master’s or a PhD we can’t even take the day off, to say: ‘I need to prepare for an exam or hand some work in’. We cover for each other, that kind of thing.”(Interview—Participant A)

4.2. Institutional Recognition

All of the participants who successfully transferred their learning benefitted from institutional recognition; in contrast, in the case of participants who were not successful in transferring their learning, this recognition did not exist.

Among examples of recognition described in the Portfolio, one participant said she had been promoted because of the training before the end of the course. This was not only a recognition of learning transfer, but also an incentive to continue it:

“I’m currently working as coordinator of all the areas of the Secretary of Education’s in-service training—a key position for being able to propose and create training activities that respond to current teaching needs—I believe that’s because I was studying for my Master’s degree.”(Portfolio—Participant F)

In the same vein, another of the participants who successfully transferred their learning also stated that, as a result of her efforts, which were recognized by the centre, the institution was rewarded with resources:

“Collaborating in the school’s management of ICTs and the use of technological resources, and teaching my colleagues how to use and manage them and how to use them with the students, all this meant I received recognition recently. I received recognition from the Secretary of Education, specifically for my initiative and work at the institution, and that’s why they gave us tablets and computers.”(Interview—Participant H)

Dissatisfaction with the institution was detected among those participants who said they were not successful in transferring their learning, as there were no possibilities for promotion or other types of recognition or stimuli, as described below:

“It’s a government institution, so that’s how it works. One of the things I have problems with is that I can’t take up another job because of my age, there’s an age limit where you can’t… So, well, many people call it discrimination; I don’t know if it is or not—the truth is, it doesn’t really interest me.”(Interview—Participant B)

4.3. Teaching Culture

In terms of teaching culture, most participants received support from their work colleagues. None of those who did not receive peer support were successful in transferring their learning.

Here it is also important to highlight the relationship between institutional recognition and the teaching culture of the centre. All of the participants who said they received recognition also said their institution had an open and collaborative teaching culture, and these were the ones who were successful in transferring their learning, as was seen in the previous category, so to some extent they were rewarded for the effort of collaborating with each other. In contrast, among those participants who were not successful in transferring their learning, there was no evidence of institutional recognition or peer support, so it would seem plausible to think that the cultural guidelines at the institutions we are talking about are quite different.

In more detail, all of those participants who were successful in transferring their learning stated that they had received the support of colleagues in implementing changes at work, as exemplified below:

“There are colleagues who contributed, collaborated, they like it, they listen and ask me ‘How do I do this?’, ‘Can you help me with this?’, ‘Look, I want to do such and such a thing’. Fortunately, at the moment my degree work is focused on the Maths department and my colleagues have collaborated with me, they have been prepared to make changes, and to listen to and see the proposals that I have for innovation using ICTs in the Maths department.”(Interview—Participant H)

Meanwhile, those who were not successful in transferring their learning talked about a lack of support and collaboration among colleagues in implementing change effectively:

“Resistance is disguised. At first they say ‘Yes, we’re going to make these changes, because the use of ICTs is wonderful and students should also think about it’, and all that is said, but when you go to the classroom there isn’t much of that, it’s not the reality, our practices are not as up to date as we say they are in public.”(Interview—Participant B)

In addition to the institution’s teaching culture, some participants mentioned the collaboration among fellow students on the Master’s programme, as stated below:

“Especially with colleagues who are here on the Master’s programme, and up to now we sometimes talk about our workplaces, and some work in universities and they tell me about their practices, I tell them about mine and especially in the place where I work with my fellow teachers, I also talk to them about how they’re teaching me here on the Master’s programme. So I feel good, also online, I don’t feel out of place in that sense, which makes me very happy.”(Interview—Participant E)

4.4. Opportunities to Apply Learning

Most participants did not have opportunities to apply what they had learnt in the work environment. None of those without these opportunities were successful in transferring their learning. In addition, one of the obstacles most often mentioned was a lack of time for implementing changes:

“Time, everything is rushed, everything is fast, there’s no time for anything, so things stay the way they were without much reflection, without much thought, but it’s only because of time, that’s the big obstacle, we don’t stop to say: we have to stop and it doesn’t matter if it doesn’t work out, it doesn’t matter.”(Interview—Participant B)

However, among those participants who were successful in transferring their learning, the opportunities they had to apply the learning were reflected in their subsequent autonomy when it came to proposing initiatives for implementing changes at their centres:

“I have leadership skills, so I’m always like ‘Look, let’s do a course’ or ‘Let’s do this’, that’s how it started to happen. So, let’s teach the teachers, let’s train them, because to be fighting among ourselves and criticizing each other, well, those of us who know a little bit or are studying, well, let’s teach those who don’t or aren’t.”(Interview—Participant H)

When analysing these ideas in relation to the profile of the participants, it is worth considering that this autonomy may also be linked to the fact that half of the participants who were successful in transferring their learning held a management position, and their degree of performance was perhaps higher because they held positions of responsibility in their institutions and displayed the according personal and social commitment to their work. Therefore, there also seems to be a possible relationship between the factor of institutional recognition after promotion and personal commitment to making changes.

All of the above also suggests that experience working in the same environment—as seen in the average number of years the teachers or university professors worked in the same centre where they successfully transferred their learning—is a determining factor in making the successful transfer of learning more probable. This is possibly because they are more familiar with the reality of the environment, and autonomy comes from a relationship of trust that has been built up with the supervisor.

Only the participant with financial support and the active support of the centre supervisor was able to implement their learning via a concrete opportunity for change:

“A few weeks ago, I was offered the opportunity to teach a Robotics course and it’s here where I will put into practice what I saw in this subject, because during the Robotics class students form groups, but they have to work collaboratively, not only in person but also in a virtual environment. I’ve tried to put theory into practice in my workplace by applying what I learned in class with my students.”(Portfolio—Participant E)

Those participants who were not successful in transferring their learning reported not having the opportunity or the autonomy to make changes in their own classes:

“The university transferred to Moodle, so now students have to participate in a course that is set up and organized by a single person. So we lost personalization, specifically following up with the students and the support of face-to-face attendance. We’re now mere tutors; we can’t change the syllabus. For me, because of a University policy, it was a huge loss of the relationship I had been building with my students.”(Interview—Participant A)

4.5. Feedback

The feedback received by our participants from their students was also important for transferring learning to practice (of the participants who said they had this support from their students, only one did not successfully transfer their learning.) In the following account, the participant acknowledges that the feedback from her students contributed to the implemented changes:

“Yes, I have received several, even now with the latest project we are working on; teaching the teacher to create a digital teaching portfolio, in the two examples I have worked on, a portfolio has been created, as if I were a teacher, I have uploaded plans and everything, attendance controls. I’ve received several contributions from them and the improvements that have been made to it have been thanks to their experience, because, of course, I’m outside in a supervisory position and they’re the ones who really know what’s needed in the classroom, so I think it’s been a joint effort.”(Interview—Participant F)

Only two participants were successful in transferring their learning while receiving no feedback at all in their work context. Participants who did not successfully transfer their learning mostly described feedback of resistance to change in their practices:

“There was a little more resistance from the students when they were told: ‘The content is going to be digitalized’. For them it was like: ‘But why?’, and ‘Why are we going to see this type of training if we’re not going to learn? Computers are distractions’, and endless other comments.”(Interview—Participant J)

4.6. Predisposition to Change

With regard to institutions’ predisposition to change, a little more than half of the work environments were open to innovation; of the participants working in these institutions, only one did not successfully transfer learning. Another aspect observed among those who did successfully transfer their learning is that this openness is linked to the continuous learning of teachers, with peers sharing the changes they had learned with one another:

“Yes, they’re open to change, even right now we’re trying to train ourselves, they asked us to give ICT training to the rest of the teachers and some coordinators who want to learn. We’re going to have different levels so that teachers can be trained according to where they are, some know nothing, and some know a little bit, and some are already more advanced.”(Interview—Participant H)

“Since 2017, a new resolution has been in place which states that up to 50% of the subjects of any degree can be taught via distance learning. This motivated me and what we did was put together a training course for teachers, because some were totally against it and others weren’t, we put together a course that we applied to a specific degree. It turned out very well, those who weren’t motivated became motivated and some of them will never belong in the virtual world [Laughs].”(Interview—Participant D)

Most of the participants who did not successfully transfer their learning stated that although their institutions are focused on innovation in technology, they have traditional behaviour that is resistant to innovation in teacher training:

“We acquire technological knowledge from courses in computer rooms at the schools where we work, and these are given by the school technician. This means that they present us with a resource and tell us how it works and all the benefits it has; we’re amazed, but when we try to think of a practical and easy way to use it in our groups, we realize that we don’t know when we could make use of it and if we try to do something we spend many hours trying. This happens all too often and the result is that, despite taking courses and workshops, our classes have few substantial changes.”(Interview—Participant B)

4.7. Resources

Most of the participants considered that the availability of physical and technological resources was essential. However, despite its theoretically transcendental potential, although an apparent practical obstacle when it comes to learning transfer, it is not seen as a deterrent in the strictest sense (it conditions implementation but does not prevent it). All of those participants who successfully transferred their learning reported doing so despite these limitations in their work environment:

“The infrastructure itself is ok, let’s say, it has the basics, but with quite a few limitations, that’s how I would describe it. It doesn’t have everything, but it does have what is necessary to apply what we’ve learned in the Master’s classes.”(Interview—Participant F)

“Yes, because, well, I don’t have the computers I’d like, I’d like to have laptops and have an area for the laptops, but in each department of the hospital there’s a computer and it’s very old, but it works; I intend to apply the final project using these computers, that is, I do have the resources, but they aren’t optimal, but I have to work with what I have.”(Interview—Participant C)

Some participants, despite successfully transferring their learning, said that the lack of adequate technological resources in their workplace may hinder the implementation of changes in practice:

“I feel that, more than anything else, that’s what makes it difficult for me in practice, it’s not in itself the fear of transferring what I’ve learned, but more than anything not finishing it due to a lack of time or difficulties, that I may not have the necessary technology to apply them.”(Interview—Participant E)

In some accounts, it is possible to identify participants using their own resources for implementing changes. Here, the lack of physical and technological resources can be considered a barrier to learning transfer, since changes are made using the teacher’s personal resources, as reported in this interview:

“Well, in my work environment, 12 of us work in a single space, the physical space we share is very small, in terms of technological resources, we only have desktop computers, Internet access from the companies that provide the service free of charge to the state, so it’s very bad. So sometimes you have to connect to your own Internet or look for a place where there’s better coverage. Then in terms of technological resources, I understand that there are plans to provide the regional centres where we work with technology, but we haven’t seen it yet, so we work with what we’ve got, it isn’t much, but I think that with good will and pooling personal resources we can do a lot.”(Interview—Participant F)

In contrast, almost all of the few participants who mentioned access to economic resources in their work environment did not successfully transfer their learning, which suggests that the lack of resources can act as a barrier to this process to some extent, even if their availability is not a determining factor:

“Funding is available because it is one of the organization’s objectives, money isn’t tight for anything to do with technology and if it’s necessary in my part of the training, there are definitely enough funds to be able to change platforms, get other suppliers.”(Interview—Participant J)

5. Discussion

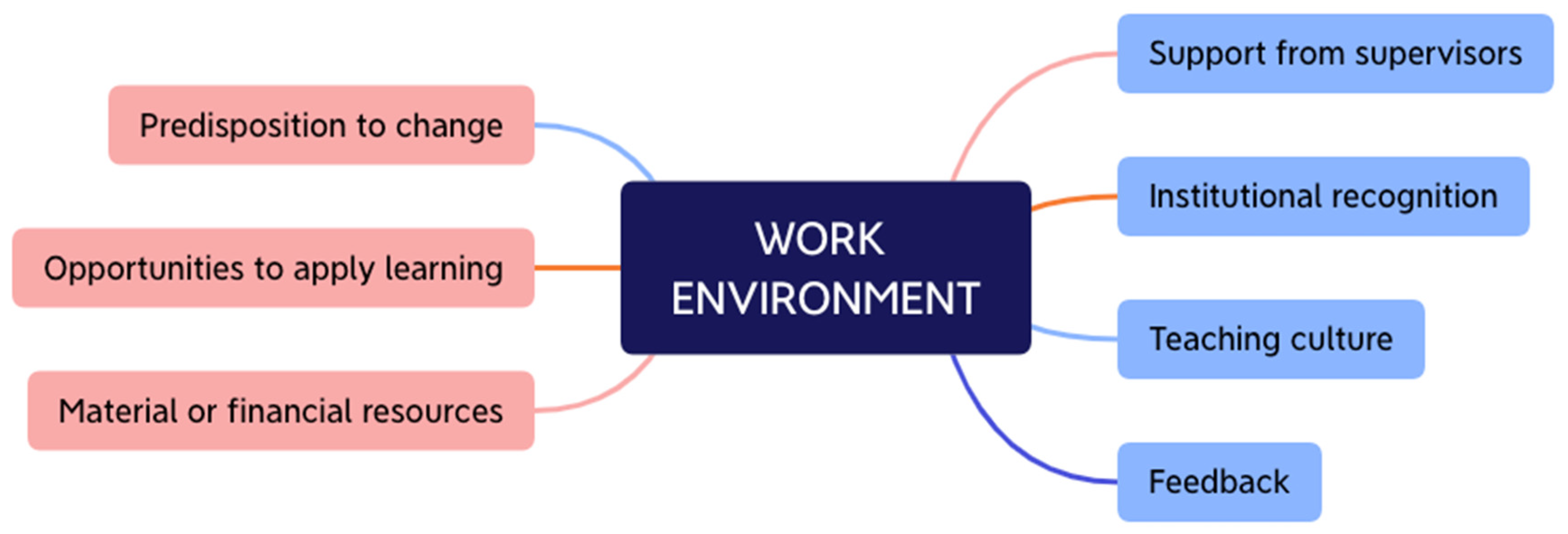

In accordance with the original aims of this study, the most relevant characteristics of the work environment that may favour or hinder learning transfer in the context of online in-service teacher training have been identified, as well as the prevalence of some factors that enhance this process. These are detailed in the following diagram (Figure 1), where the most facilitating factors are placed on the right side of the map and those that could be an obstacle on the left.

Figure 1.

Elements that influence the work environment. Source: authors’ own work.

In the category of supervisory support, it was observed that only one participant who reported having successfully transferred their learning had the active support of their supervisor in the training. The support provided by supervisors of other participants who successfully transferred their learning was in the form of dialogue and availability of time.

Here are results corroborating with previous studies, which indicate that the power distance of administrators has a very important effect on organizational silence [27]. That is, teachers take refuge in silence so as not to get negative feedback from superiors with the perception that something will not change, even if they say so. Supervisors with high power distance generally keep communication in an official dimension, without interaction and accessible dialogue, avoiding offering a participatory environment.

The results confirm that supervisors do not dedicate much time to discussing the programmes with participants, which may lead to trainees lacking an understanding of how to apply the training in the workplace [14]. However, it was observed that those participants who successfully transferred their learning proposed strategies for applying their new knowledge at work to their supervisors, or at least were aware that they would receive support in this regard if required [5,6,7,9,12,13].

It was also noted that once those participants who felt they were an important part of the institution had understood the relevance of the training to their work, they were able to successfully transfer their learning [5,8,10,15,17]. Those participants who did not successfully transfer their learning reported a lack of both permission to attend training and space for dialogue.

In terms of institutional recognition, the participants who successfully transferred their learning were promoted or rewarded with resources, fostering the necessary commitment to make changes that improved their work [17,19]. Participants who already felt undervalued at work, and who had no appraisal for their training, did not successfully transfer their learning.

The importance of peer support was also detected. Participants who successfully transferred their learning described a teaching culture that included a support network for exchanging their experiences of implementing change [6,9]. Participants who did not successfully transfer their learning perceived resistance from their peers in their work environment, thereby hindering this process [17].

A further finding was that in online teaching half of the participants managed to network with peers and exchange ideas with them about the content of the course [16,20], which may also have contributed to the successful transfer of learning during training [21].

With regard to opportunities to apply learning, only the participant who was financed by the institution and whose supervisors accompanied their progress during training had concrete opportunities to use what they had learnt.

Almost all of the participants reported a lack of time as being an obstacle to learning transfer, given that no supervisor considered the possibility of modifying their workload to allow them to adapt the new learning to their work [14]. That being said, those who successfully transferred their learning had the autonomy to adapt their classes independently of the workload once their supervisor and colleagues had shown openness and confidence in their initiatives or because they held a management role.

The autonomy factor implies that the greater the degree of freedom teachers and university professors have to do their work, the greater their ability to adapt and transform the way they do it, thus favouring learning transfer [17]. Participants who did not successfully transfer their learning did not have the autonomy or the support of their colleagues to adapt what they had learnt to the context of their work, thus limiting learning transfer.

We can also relate this fact to the participants’ time of experience in the same institution once novice teachers may not have reached transfer due to the absence of peer support, as already observed in another study previously [28]. There is a need for supervisors to provide more opportunities for novice teachers and experts to communicate with each other formally and informally, as the support of an expert may be more important than the knowledge they possess for changes in practice to occur.

Another clear finding is that positive feedback from students contributed to participants’ transfer of learning [6,9,16]. Resistance to feedback appears to have represented a hindrance to those who did not successfully transfer their learning.

Regarding predisposition to change, most of the participants considered that their institution was open to change, but that the training offered was linked to innovation in technological resources, and not necessarily to changes in the teacher’s or university professor’s way of working. Participants who successfully transferred their learning described a culture that was open to continuous teacher learning [6,10,16].

In relation to resources, most of the participants clearly believed resources to be limited, which even meant they had to use their own material. However, the participants’ accounts show that, despite the difficulties, changes were made to the basic physical conditions of the teachers’ or university professors’ environments [6,9,20]. It was also observed that among those who did not successfully transfer their learning, most said they had the funding to purchase resources when necessary, indicating that the availability of resources does not directly foster learning transfer.

6. Conclusions

We therefore conclude that all of the participants who successfully transferred their learning had institutional recognition and peer support, and most of this group received supervisor support and positive feedback from their students. In contrast, none of the group who failed to successfully transfer their learning said they received supervisor support, institutional recognition or peer support, while they reported experiencing resistance to feedback.

Worthy of special note among the obstacles mentioned to having the opportunity to use and apply what they had learnt was a lack of time. That being said, those participants who successfully transferred their learning described an openness to continuous learning, including space for autonomy and training offered by peers, favouring this successful transfer [6,10,16]. Although a lack of resources could have proved a barrier to change, when participants perceived support for learning transfer from the institution, the effects of this were minimalized [20].

Despite the limitations of this study in terms of the small number of participants and the varied work backgrounds of the participants, in our specific context of the online techno-pedagogical training of ICT skills—with learning transfer still a new area for research—we are able to confirm the relevance of the categories previously described in the literature on enhancing learning transfer in the work environment. We would also highlight the prevalence of social support categories over those of an organizational nature [20] when it comes to strengthening the learning transfer process in the context of online in-service teacher training.

It is important to note that this article contains only part of the findings of a broader study of learning transfer in the context of in-service and online training. Based on the results described here, and from a future triangulation with previously known personal aspects and aspects of the design of the course studied, it will be possible to obtain guidelines for future educational strategies that lead to a better approach to the learning transfer process in online in-service training, specifically of ICT skills.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, F.F. and J.G.-M.; Methodology, F.F. and J.G.-M.; Validation, J.G.-M.; Formal analysis, F.F.; Investigation, F.F.; Resources, J.G.-M.; Data curation, F.F.; Writing—original draft, F.F.; Writing—review & editing, F.F. and J.G.-M.; Supervision, J.G.-M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research is part of an industrial PhD project funded by Generalitat de Catalunya (Agència de Gestió d’Ajuts Universitaris i de Recerca, grant number 2018 DI 96). The APC was funded by University of Girona.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study due to due to at the time we collected the data this process was not mandatory at the University of Girona (reference institution for this project) nor at the UNEAT (university were the fieldwork was developed) nor by the Agència de Gestió d’Ajuts Universitaris i de Recerca (AGAUR) (the funding institution), since this research does not use particularly sensitive human data (only opinions and perceptions regarding public dimensions of life) and does not involve direct intervention or experimentation on humans or living beings. However, the necessary ethical requirements have been respected. For the performance of this study, it has enough to have the informed consent of the subjects. In particular, this informed consent included the introductory text “I am fully assured that I will not be identified and that the information I provide will be kept confidential. The results will be made available to me at my convenience. The data will be treated confidentially and treated for academic analysis only”, thus ensuring the protection of personal data and guaranteeing digital rights.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. Because of its personal nature (opinions and beliefs about one’s own learning process), despite anonymity, it cannot be openly hosted in a research data repository.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Pisanu, F.; Fraccaroli, F.; Gentile, M. Training Transfer in Teachers Training Program: A Longitudinal Case Study. In Transfer of Learning in Organizations; Schneider, K., Ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2014; pp. 99–120. [Google Scholar]

- Feixas, M.; Lagos, P.; Fernández, I.; Sabaté, S. Modelos y tendencias en la investigación sobre efectividad, impacto y transferencia de la formación docente en educación superior. Educar 2015, 51, 81–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldwin, T.T.; Ford, J.K. Transfer of training: A review and directions for future research. Pers. Psychol. 1988, 41, 63–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blume, B.; Ford, K.; Baldwin, T.; Huang, J. Transfer of training: A meta analytic review. J. Manag. 2010, 36, 1065–1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Rijdt, C.; Stes, A.; van der Vleuten, C.; Dochy, F.Y. Influencing variables and moderators of transfer of learning to the workplace within the area of staff development in higher education: Research review. Educ. Res. Rev. 2013, 8, 48–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feixas, M.; Durán, M.; Fernández, A.; García, M.; Márquez, M.; Pineda, P.; Quesada, C.; Sabaté, S.; Tomàs, M.; Zellweger, F.; et al. «¿Cómo medir la transferencia de la formación en educación superior?: El Cuestionario de Factores de Transferencia». Rev. Docencia Univ. 2013, 11, 219–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ornelas, D.; Cordero, G.; y Cano, E. La transferencia de la formación del profesorado universitario. Aportaciones de la investigación reciente. Perfiles Educ. 2016, 38, 57–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burke, L.A.; Hutchins, H.M. Training Transfer: An Integrative Literature Review. Hum. Resour. Dev. Rev. 2008, 6, 263–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomás -Folch, M.; Duran-Bellonch, M.Y. Comprendiendo los factores que afectan la transferencia de la formación permanente del profesorado. Propuestas de mejora. Rev. Electrónica Interuniv. Form. Del Profr. 2017, 20, 145–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holton, E.; Reid, A.; Ruona, W. Development of a Generalized Learning Transfer System Inventory. Hum. Resour. Dev. Q. 2000, 11, 333–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, D.; Morris, M. Influence of Trainee Characteristics, Instructional Satisfaction, and Organizational Climate on Perceived Learning and Training Transfer. Hum. Resour. Dev. Q. 2006, 17, 85–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quesada-Pallarés, C.; Espona-Bracons, B.; Ciraso-Calí, A.; Pineda-Herrero, P.Y. La eficacia de la formación de los trabajadores de la administración pú∫blica española: Comparando la formación presencial con el eLearning. Rev. Del CLAD Reforma Y Democr. 2015, 61, 107–132. [Google Scholar]

- Cano, E. Factores favorecedores y obstaculizadores de la transferencia de la formación del profesorado en educación superior. Rev. Iberoam. Sobre Calid. Efic. Y Cambio En Educ. 2016, 14, 133–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, N. Job/Work Environment Factors Influencing Training Transfer within a Human Service Agency: Some Indicative Support for Baldwin and Ford’s Transfer Climate Construct. Int. J. Train. Dev. 2002, 6, 146–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cano, E. Evaluación de la formación: Algunas lecciones aprendidas y algunos retos de futuro. Educar 2015, 51, 109–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Testers, L.; Gegenfurtner, A.; van Geel, R.; and Brand-Gruwel, S. From monocontextual to multicontextual transfer: Organizational determinants of the intention to transfer generic information literacy competences to multiple contexts. Frontline Learn. Res. 2019, 7, 23–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, N.; Segers, M.; Gijselaers, W. Effects of work environment on transfer of training: Empirical evidence from master of business administration programs in Vietnam. Int. J. Train. Dev. 2013, 17, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, D.; Nowell, B. Integration for Training Transfer: Learning, Knowledge, Organizational Culture, and Technology. In Transfer of Learning in Organizations; Schneider, K., Ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Yaghi, A.; Bates, R. The role of supervisor and peer support in training transfer in institutions of higher education. Int. J. Train. Dev. 2020, 24, 89–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, L.; Zerbini, T.; and Medina, F.J. Impact of Online Training on Behavioral Transfer and Job Performance in a Large Organization. J. Work. Organ. Psychol. 2019, 35, 27–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bates, R.A.; Holton, E.F.; Seyler, D.L.; Carvalho, M.A. The role of interpersonal factors in the application of computer-based training in an industrial setting. Hum. Resour. Dev. Int. 2000, 3, 19–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, D.; Johnson, S. Trainee perceptions of factors that influence learning transfer. Int. J. Train. Dev. 2002, 6, 36–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisner, E.W. Ojo Ilustrado: Indagación Cualitativa y Mejora de la Práctica Educativa; Paidós: Barcelona, Spain, 1998; pp. 81–103. [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh, H.F.; Shannon, S.E. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual. Health Res. 2005, 15, 1277–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bardin, L. Análise de Conteúdo; Edições: São Paulo, Brazil, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Stake, R.E. Investigación con Estudio de Casos; Morata: Madrid, Spain, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Aslan, H. The Relationship Between Teachers’ Perceived Power Distance and Organizational Silence in School Management. Int. J. Psychol. Educ. Stud. 2022, 9, 644–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, X.; Li, T.; Meirink, J.; van der Want, A.; Admiraal, W. Learning from novice–expert interaction in teachers’ continuing professional development. Prof. Dev. Educ. 2021, 47, 745–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).